Abstract

This study investigates how local gastronomic products with strong cultural and heritage value can contribute to destination identity and sustainable rural tourism development. Focusing on cave-aged cheeses, it emphasizes the case of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon (France), where traditional cheese-making and natural cave-aging have been successfully integrated into tourism experiences that reflect terroir, authenticity, and rural heritage. To explore tourist motivations, a survey of 416 visitors was conducted. Factor analysis and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) were used to identify the main drivers behind cheese-related tourism. The analysis revealed three key motivational factors: Traditional Gastronomy, linked to interest in regional food practices; Cheese Experience, emphasizing the unique appeal of Roquefort cheese; and Heritage Tourism, reflecting a desire to connect with rural identity and sustainable traditions. These results support the hypothesis that culturally significant local food products can serve as central elements in shaping place identity and attracting visitors through immersive, heritage-based experiences. The study concludes that food heritage can be a powerful tool for rural development, offering economic, cultural, and experiential value. It also identifies similar opportunities in Serbian regions such as Pirot and Sokobanja, where traditional kačkavalj cheese and natural cave environments present strong potential for tourism growth rooted in local identity.

1. Introduction

In an increasingly globalized world, the distinctiveness of local products has emerged as a vital component in shaping the identity of destinations []. Local products, often defined as goods that are produced within a specific geographical region and reflect the cultural heritage of their surroundings, play a critical role in not only fostering a sense of place but also in enhancing the economic viability of communities []. These products often serve as tangible representations of the traditions, customs, and values of the people, thus contributing to a broader narrative that defines a region’s identity []. From the renowned wines of Bordeaux [] to the artisanal cheeses of Switzerland [], local products have not only encapsulated the essence of their origins but have also become powerful symbols that attract tourism and build community pride [].

The significance of local products in shaping destination identity cannot be overstated []. Local products are characterized by their unique attributes, which often stem from traditional methods of production, local ingredients, or historical significance associated with the region []. According to Antolini et al. [], the rich Italian cuisine relies heavily on local ingredients and methods that vary from region to region, underpinning the identity of places such as Emilia-Romagna or Campania. Historically, local products have been pivotal in the development of regional identities; they often tell stories of the land and its people, weaving narratives that have been passed down through generations [,,,]. Regions such as Champagne in France [] or the Basque Country in Spain [] have successfully aligned their identities with their local products—champagne and pintxos, respectively—creating a sense of pride among locals and recognition among tourists []. These products serve not only as commodities but as cultural artifacts that embody the spirit, heritage, and authenticity of their locales [].

As local products evolve, they often undergo a transformation into cultural symbols that embody the traditions and customs of a destination []. Festivals and events dedicated to local products play a crucial role in this process, acting as platforms for promotion and celebration [,,,,]. According to Varela [], the annual Pizzafest in Naples showcases the city’s iconic pizza, drawing both locals and tourists alike to partake in a celebration of culinary heritage. Such events not only elevate the status of local products but also engage the community, reinforcing cultural ties [,]. According to He et al. [], local products often reflect the unique practices and values of the region, serving as a reminder of the collective identity of its people. Successful branding strategies have further solidified this transformation; consider the case of Vermont’s maple syrup, which has become an emblem of New England’s agricultural identity [,]. Through clever marketing and storytelling, local products can transcend their utilitarian purposes, becoming cherished symbols of cultural pride that resonate with both residents and visitors [].

Cave-aged cheese, as a traditional and regionally distinctive food, serves as a compelling example of how culinary heritage can support sustainable rural tourism and contribute to the revitalization of local economies []. The significance of cave-aged cheese in rural tourism is underscored by its rich historical context and unique characteristics []. Traditionally, cave-aged cheese production dates back hundreds of years, often originating in regions where natural caves provided the ideal microclimate for fermentation and aging []. The unique characteristics of cave-aged cheese, such as its distinctive flavors and textures, arise from the specific microorganisms present in the cave environments, which cannot be replicated in commercial cheese production []. This authenticity is a major draw for tourists seeking unique culinary experiences []. According to Sgroi [], local culinary traditions, such as cheese-making workshops and tasting tours, actively engage visitors and enhance their understanding of regional culture. This connection between food and place not only attracts tourists but encourages them to immerse themselves in the local way of life, fostering a sustainable tourism model that benefits rural communities economically and socially.

Among such destinations, Roquefort-sur-Soulzon in southern France stands as a globally recognized model, where the production and aging of Roquefort cheese in natural caves have not only preserved a centuries-old tradition but also generated sustainable tourism that intertwines sensory experience, heritage valorization, and local economic revitalization []. According to Jolly et al. [], the famous Roquefort cheese, aged in the caves of southern France, has been produced since the Roman era, establishing a deep-rooted connection between local culture and culinary heritage. Attracting approximately 200,000 visitors annually, this small village demonstrates how a niche product, deeply embedded in local identity, can serve as a cornerstone for destination branding and rural sustainability. While France’s Roquefort cheese has become an internationally recognized symbol of rural identity and economic vitality—supported by strong geographical indication (GI) protection and integrated agri-tourism—Serbia’s cave-aged Kačkavalj, particularly from the village of Staničenje near Pirot, remains largely forgotten.

This research draws on the example of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon to explore the broader relationship between traditional cheese-making, cultural authenticity, and tourist motivation. By examining the motivations, experiences, and perceptions of 416 visitors through a quantitative methodology grounded in positivist epistemology, the study seeks to validate the hypothesis that local gastronomic products with strong heritage value—like cave-aged cheeses—can act as catalysts for sustainable rural tourism and destination identity formation. The novelty and applied relevance of this research lie in its comparative and visionary potential. While Roquefort-sur-Soulzon serves as an established benchmark, this study proposes a transfer of knowledge and practice to Staničenje, a village near Pirot in southeastern Serbia. Nestled in the shadow of the Stara Planina mountains, Staničenje holds a lesser known but historically significant legacy in cheese maturation. From the mid-20th century, the natural cave in this village functioned as a low-energy, ecologically sustainable maturation chamber for Pirot kačkavalj cheese—exported globally and revered for its unique flavor, enhanced by the cave’s naturally regulated microclimate. Unlike modern industrial cheese production, the Staničenje cave exemplifies a form of rural heritage practice that is both environmentally and economically sustainable yet underutilized in Serbia’s current tourism and development frameworks. Moreover, the research identifies Sokobanja, a prominent spa and wellness destination, as another untapped opportunity. Known for its karstic geological features, Sokobanja has numerous caves that could potentially be adapted for cheese aging—opening a path for the development of a geographically specific product such as Sokobanja kačkavalj. Integrating cheese production with wellness tourism would create a unique tourism blend: nature, health, and gastronomy, thus broadening the destination’s appeal while fostering local pride and sustainable livelihoods.

This leads to the central hypothesis of this study H: Local gastronomic products with strong cultural and heritage value—such as cave-aged cheeses like Roquefort or Pirot kačkavalj cheese—can serve as central elements in shaping destination identity and motivating sustainable rural tourism development through authentic, multisensory, and heritage-based experiences. By applying insights from the case of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, this study aims to establish a replicable model for revitalizing similar destinations through cheese heritage tourism. It highlights the potential of multisensory, place-based experiences to foster emotional engagement, cultural learning, and sustainable travel behaviors—while contributing to rural economic resilience.

The findings reveal three principal components, namely Traditional Gastronomy, Cheese Experience, and Heritage Tourism, which justified 84.781% total variance on tourist motivations. Major gastronomy tradition offers substantial motivation for tourists through true, meaningful, and multi-sensorial experience which involves feelings toward cultural heritage and local identity. There is anticipation of taste, smell, and visual appeal which will spice up the desire to explore and consume the place through the local cuisine; the traditional dishes are symbols of place and craftsmanship. This is the sort of duality that Roquefort cheese has. It is not only a culinary attraction but also an emblem of heritage that enhances tourist involvement through experiential learning, through educational interactions, and through emotional resonance, ultimately anchoring the relationship of food, culture, and place. This study does not only advance theoretical insights in gastronomic and heritage tourism but also fulfills a strategic objective to inspire heritage-based rural revitalization in places like Pirot and Sokobanja by reactivating their authentic resources that have been overlooked for quite a long time—natural caves for cheese ripening, traditions of making artisan cheese, and identities for culinary traditions.

Despite growing recognition of local gastronomic products as drivers of rural tourism and destination identity, there remains a lack of empirical research specifically linking cave-aged cheese heritage with sustainable rural tourism development. While prominent cases like Roquefort-sur-Soulzon are well documented, less attention has been paid to comparable but underutilized contexts in Eastern Europe, particularly Serbia. Existing literature often overlooks the integration of natural cave environments as authentic, low-impact maturation spaces with tourism potential. Moreover, few studies have quantitatively investigated the specific tourist motivations tied to these unique heritage food products, leaving a gap in understanding how such culinary traditions can be strategically mobilized to foster sustainable destination branding and economic resilience in lesser-known rural areas. This study addresses these gaps by offering a novel, comparative analysis of cave-aged cheese tourism, combining a well-established model from Roquefort-sur-Soulzon with an emerging Serbian context. By applying quantitative methods grounded in positivist epistemology—specifically factor analysis and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)—this research empirically identifies key motivational factors behind cheese-related tourism. It contributes to the broader fields of gastronomic and heritage tourism by demonstrating how multisensory, authentic culinary experiences rooted in cultural heritage and place identity can serve as catalysts for sustainable rural development. The study advances theoretical understanding of food heritage as a multidimensional construct that bridges culture, economy, and tourism, while offering practical insights for rural revitalization initiatives in Serbia and similar regions.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive literature review on local gastronomic products, heritage tourism, and sustainable rural development, with a particular focus on cave-aged cheeses. Section 3 details the materials and methods, including the survey design and the quantitative approach used to analyze tourist motivations. Section 4 presents the results of the factor analysis and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), identifying the key motivational components. Section 5 offers a detailed discussion of the findings, structured into six subsections: Section 5.1 examines Traditional Gastronomy as a multisensory and motivational driver (H1 & H2); Section 5.2 explores Roquefort cheese as a central experiential anchor (H3 & H4); Section 5.3 discusses cultural and rural authenticity as catalysts for immersive experiences (H5 & H6); Section 5.4 analyzes interactions between identified factors in rural cheese tourism; Section 5.5 interprets the findings in light of existing literature; and Section 5.6 outlines practical implications for rural tourism development. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study by summarizing key insights, outlining limitations, and suggesting directions for future research. The Appendix A includes the full survey questionnaire used in this study.

2. Literature Review

The cultural significance and culinary heritage of traditional gastronomy are deeply rooted in the stories and practices that have evolved over centuries. Each regional dish is more than just a culinary experience; it is a narrative that reflects the diverse cultural backgrounds and historical contexts from which it originates []. Understanding the origins and evolution of these dishes not only enhances our appreciation of their cultural and historical significance but also highlights how culinary practices have adapted over time, influenced by geographical, social, and environmental factors []. This exploration into traditional cuisine reveals the intricate connections between food, culture, and history, offering insights into a region’s past and its evolution, which in turn informs its present identity []. Culinary traditions, passed down through generations, serve as a testament to the enduring nature of cultural heritage, underscoring the importance of documenting and preserving these practices to ensure their survival in an ever-changing world [,,]. The preservation of regional dishes and their cooking techniques not only celebrates the culinary heritage of various ethnic groups but also plays a crucial role in maintaining cultural identity and promoting understanding across different communities []. Therefore, it is essential for stakeholders, including local communities and policymakers, to collaborate to protect and promote the culinary heritage, ensuring that these rich traditions continue to thrive and enrich our global cultural landscape [].

The art and science of cheese crafting are intricately intertwined, showcasing a balance between tradition and innovation that is crucial in creating distinct flavor profiles. The journey of understanding these flavors is a sensory exploration that involves both artistic interpretation and scientific understanding. Each cheese is a narrative of its origins, influenced by factors such as the type of milk used and the cheesemaking methods, all of which contribute to its unique character []. The process of aging further refines the cheese, allowing the development of rich and complex flavors that are essential to its identity []. This intricate interplay of elements not only enhances the sensory experience but also connects enthusiasts to the cultural and historical aspects of cheesemaking []. By engaging in cheese tastings, individuals can develop a refined palate, enabling them to recognize and appreciate the nuanced characteristics of different cheese styles []. Ultimately, the appreciation of cheese is not just about taste but also about understanding the cultural significance and the artistic expression embodied in each artisanal creation [].

Tourists are attracted by opportunities for immersive experiences, such as guided visits to natural caves used for aging cheese, tasting local products, and engaging with producers who embody generational knowledge []. This form of tourism provides a symbolic escape from modernity while enabling a reconnection with sustainable and traditional ways of life []. Comparable motivations have been identified in other heritage-rich rural areas. According to Poggi et al. [], in Tuscany’s Val d’Orcia, tourists are drawn by its UNESCO-protected cultural landscape, historic hilltop towns, and traditional agricultural practices. Similarly, in the Spanish region of La Rioja, visitors seek out wine tourism experiences that combine rural aesthetics, local gastronomy, and deep-rooted cultural narratives []. In both cases, as in Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, travelers are motivated not only by scenic beauty but by a desire to connect with local identity, sustainability values, and living traditions [].

According to Karoui et al. [], in Gruyères, Switzerland, visitors are attracted by the picturesque Alpine setting and the opportunity to witness traditional Gruyère cheese-making in artisanal fromageries. The destination offers immersive visitor experiences, including cheese museums, tasting sessions, and educational workshops, all framed within a strong sense of heritage and regional pride. According to Mauricio et al. [], the Parmigiano Reggiano region in Emilia-Romagna, Italy, draws culinary tourists eager to observe the aging process in large cheese warehouses and learn about centuries-old methods preserved by local consortia. These destinations, like Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, appeal to travelers who value authenticity, craftsmanship, and sustainable food heritage []. In this context, cave-aged cheese transcends its role as a gastronomic product and becomes a symbolic asset through which destination identity is constructed and communicated. The sensory uniqueness, production setting, and cultural narratives embedded in the cheese contribute directly to place branding, allowing destinations such as Roquefort-sur-Soulzon to distinguish themselves within competitive rural tourism markets [].

In each of these cases, the combination of rural atmosphere, gastronomic tradition, and cultural storytelling forms a compelling tourism proposition []. Visitors are not merely consuming products but participating in a cultural ritual, making such destinations ideal for those motivated by immersive heritage experiences []. These dynamics can be interpreted through the lens of experiential tourism theory, where visitors seek not only consumption but active participation and emotional connection with place []. The concept of cultural capital is also relevant, as local products like Roquefort cheese carry symbolic value that enriches both personal experience and community identity. Roquefort-sur-Soulzon thus exemplifies how cheese tourism can serve as a vehicle for rural cultural revitalization, sustainability awareness, and experiential travel []. These parallels highlight a broader trend in rural tourism, where authenticity, heritage, and immersive learning form the core of the visitor experience []. Consequently, Roquefort-sur-Soulzon stands as a representative case of how rural destinations can leverage cultural capital and sustainability to attract meaning-seeking tourists.

3. Materials and Methods

The total number of valid respondents in the survey was 416. Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, renowned for its iconic blue cheese matured in natural caves, attracts a significant number of tourists annually. Estimates suggest that the village receives approximately 200,000 visitors each year. As stated by Ahmed [], for a tourist population of 200,000, with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%, the optimal sample size is determined to be 384 respondents. Therefore, the sample from Roquefort-sur-Soulzon that took part in the study is both valid and reliable.

The gender distribution was relatively balanced, with a slight predominance of male participants (52.2%) over females (47.8%). This gender ratio suggests a nearly equal representation, allowing for a reasonably gender-neutral interpretation of the survey results. In terms of age structure, the sample was predominantly composed of middle-aged and older adults. The largest age group was between 45 and 54 years (40.1%), followed by the 55 to 64 age category (28.8%), and respondents over 65 years of age (16.3%). Younger age groups were less represented, with only 2.4% in the 18–24 range and 5.5% in the 25–34 bracket. This distribution indicates that the study largely reflects the attitudes and behaviors of more mature tourist segments, which may influence the findings, particularly in the context of cultural and gastronomic tourism where older demographics are often more engaged. Educational attainment among respondents was predominantly at the secondary level. A total of 66.3% had completed high school, while 27.2% held a college or faculty degree. Only 2.9% had attained a postgraduate (Master or Ph.D.) level of education, and a small minority (3.6%) reported having completed only elementary education. The dominance of respondents with high school and tertiary education levels suggests a population with moderate to strong educational backgrounds, suitable for analyzing perceptions related to food heritage, tourism, and sustainability. Overall, the demographic profile suggests that the sample is composed mainly of older, moderately to well-educated individuals, with a balanced gender distribution—an important consideration for interpreting motivations and preferences related to cheese heritage tourism.

This study adopts a positivist epistemological approach, aiming to objectively investigate the relationships between tourist motivations, gastronomic experiences, and perceptions of cultural and heritage values in rural cheese-producing destinations. Rooted in a deductive research paradigm, the study tests theoretical assumptions through empirical observation, using statistical analysis to confirm or refute hypotheses regarding the role of local gastronomic products—such as Roquefort or Kačkavalj cheese—in sustainable rural tourism development and destination identity formation. A quantitative research design was employed, involving the development and administration of a structured questionnaire. The instrument was based on previously validated constructs in tourism and gastronomic motivation research and adapted to fit the specific context of cheese heritage. The questionnaire used in this study was developed based on previously validated constructs from studies on food tourism, rural tourism, and tourist motivation. The items were adapted to fit the specific context of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, a destination known for its cheese heritage and rural character. The constructs—such as cultural heritage motivation, gastronomic interest, hedonism, authenticity seeking, sustainability orientation, and trend sensitivity—were informed by prior research, including works by Björk and Kauppinen-Räisänen [], Kivela and Crotts [], Kim et al. [], Sims [], and Getz and Robinson []. These studies provided the foundation for operationalizing motivational dimensions relevant to food-based and rural tourism experiences. Items were slightly modified in wording to ensure contextual relevance while retaining their original conceptual intent. The majority of respondents in the survey conducted in Roquefort-sur-Soulzon were international tourists, accounting for 52.4% of the total sample, while domestic visitors from France constituted 47.6% (n = 198 out of 416). The international segment was composed primarily of tourists from Germany (12.5%), followed by the United Kingdom (8.7%), Spain (8.7%), the Netherlands (7.7%), Belgium (6.7%), the United States (4.8%), and Japan (3.4%). This international diversity underscores the transnational appeal of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon as a gastronomic and cultural destination. Regarding travel distance, while exact kilometer measurements were not captured in the questionnaire, the geographic spread of the visitors indicates a combination of medium- and long-haul tourism, with European tourists primarily originating from neighboring or proximate countries, and a smaller proportion of long-distance travelers from North America and Asia. The presence of such varied origin points suggests that Roquefort-sur-Soulzon is perceived not merely as a regional attraction, but as a destination of international interest, particularly in the context of food heritage tourism. In terms of visit motivation, the results from the motivational scale and subsequent factor analysis clearly indicate that cheese-related experiences were a primary driver for the visit rather than a complementary activity. The second extracted factor—labelled Cheese Experience—demonstrated strong loadings on items such as Cheese Heritage (0.910), Culinary Exploration (0.836), and Cheese Indulgence (0.779). These findings reveal a specific and focused interest among tourists in engaging with Roquefort cheese both as a product and as a cultural-symbolic object. High agreement scores on statements like “The opportunity to taste authentic, local cheese motivated me to visit Roquefort-sur-Soulzon” and “Learning about the history of Roquefort cheese was a major reason for my visit” confirm the centrality of cheese to the travel motivation. These results support the conclusion that cheese tourism in Roquefort-sur-Soulzon functions as a core tourism motivator, rather than a secondary or peripheral interest. The integration of culinary and heritage experiences contributes to the destination’s attractiveness, particularly for tourists seeking authentic, localized, and educational food-related experiences.

Items were measured using a five-point Likert scale, capturing degrees of agreement with statements related to traditional gastronomy, cheese-specific experiences, and heritage tourism values. The research was conducted during the summer months of 2024, when the number of visits to these caves is the highest. Data were collected on-site in Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, a rural destination recognized for its strong integration of gastronomic and heritage tourism. The primary site for survey administration was the Société Caves, the most prominent cheese-aging facility in the village, which attracts over 200,000 visitors annually. The data collection was conducted using a convenience sampling approach, targeting visitors at key tourist touchpoints such as cheese producers (Roquefort Gabriel Coulet and Papillon) offering guided tours and tastings, as well as along the hiking trails of the Parc Naturel Régional des Grands Causses. This approach was chosen to capture a diverse range of visitor profiles and motivations within the practical constraints of the fieldwork setting.

This methodological framework enables a structured examination of the central hypothesis H: that local gastronomic products with strong cultural and heritage value—such as cave-aged cheeses like Roquefort or Pirot kashkaval cheese —can serve as central elements in shaping destination identity and motivating sustainable rural tourism development through authentic, multisensory, and heritage-based experiences.

Bearing in mind that this research should set a model according to which similar destinations could be developed all over the world, it was necessary to set several key sub-hypotheses.

H1.

The multisensory experience of consuming traditional gastronomy (taste, smell, sight, touch) enhances tourists’ emotional and hedonic satisfaction, leading to a stronger desire to engage in food-related activities during their visit.

H2.

Tourists are more motivated to consume traditional gastronomy when it is perceived as an authentic representation of local heritage, which enhances their desire to understand the destination’s cultural identity.

To test these sub-hypotheses, the authors asked two conceptual questions: How does the availability of traditional gastronomy lead to tourist motivation? and Why does traditional gastronomy motivate tourists to explore and consume on-site?

H3.

The heritage and cultural significance of Roquefort cheese motivate tourists to prioritize it as a key experiential activity during their visit, as they seek to engage with both the product and its historical narrative.

H4.

Tourists are more motivated to engage with Roquefort cheese when the product’s heritage and artisanal status evoke emotional and intellectual curiosity, enhancing their desire to learn about its production and history.

To test these sub-hypotheses, the authors asked two conceptual questions: How does the availability and heritage of Roquefort cheese lead to desire to taste, learn about, and enjoy Roquefort cheese as a central component of the travel experience? and Why does the availability and heritage of Roquefort cheese produce this effect (Tourists’ desire to taste, learn about, and enjoy Roquefort cheese as a central component of their travel experience)?

H5.

Tourists are more likely to engage in authentic cultural experiences (e.g., attending local festivals, participating in traditional food preparation) when they perceive these experiences as opportunities for self-discovery and personal connection to local identity.

H6.

The perceived contrast between rural and culturally rich environments and urbanized, globalized settings increases tourists’ desire for immersive cultural experiences, providing emotional resonance and a sense of escape from their daily routines.

To test these sub-hypotheses, the authors asked two conceptual questions: How does cultural and rural authenticity lead to immersive heritage experiences? and Why does cultural and rural authenticity trigger desire for meaningful and immersive heritage experiences?

The subsequent task involved the application of factor analysis, which distinguished three distinct factors: Traditional Gastronomy, Cheese Experience and Heritage Tourism. Tourists were presented with a collection of 35 variables (Appendix A) that required responses on a five-point Likert scale: 1—Strongly Disagree, 2—Disagree, 3—Neutral, 4—Agree, and 5—Strongly Agree. The equation:

represents a common factor model, frequently applied in factor analysis to explain the variance in an observed variable (Xi) as a linear combination of multiple latent factors and a residual error term. In this context, the observed variable Xi (e.g., an individual survey item measuring tourist motivations or preferences) is modeled as being influenced by three latent constructs: F1: Traditional Gastronomy, F2: Cheese Experience, and F3: Heritage Tourism. Each of these latent factors (F) captures the shared variance among a set of observed indicators that reflect a common underlying dimension of tourist experience. The coefficients λ1, λ2, and λ3 are referred to as factor loadings; they quantify the strength and direction of the relationship between the latent factors and the observed variable. Higher loading values suggest a stronger association between the factor and the observed indicator. The term εi denotes the unique variance of the observed variable—including measurement error and any variance not accounted for by the latent factors. It ensures that the model distinguishes between shared (common) variance and specific variance inherent to the indicator. The purpose of this model is to reduce dimensionality and to uncover the underlying structure of observed tourist responses. This type of modeling is instrumental in tourism research, as it allows researchers to identify and validate key motivational dimensions influencing tourist behavior. By using factor analysis, one can empirically group related motivations and better understand how different experiential components—such as gastronomy, cheese production, and cultural heritage—interact in shaping tourism demand.

After the extraction of latent constructs through Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), the study advanced to the application of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). This analytical step is essential for providing a robust framework to test the theoretical model, allowing for simultaneous estimation of multiple interrelated dependence relationships.

where Y represent tourists’ motivation to engage in cultural and gastronomic activities, β the effect of perceived authenticity on motivational engagement, X perceived authenticity of traditional gastronomy (e.g., heritage value of Roquefort cheese) and ζY as unobserved factors affecting motivation (e.g., personal preferences, prior experiences, or other external influences). One of the key advantages of SEM lies in its ability to model complex causal pathways between observed and latent variables, incorporating both measurement and structural components. In the context of this research, the factors derived—Traditional Gastronomy, Cheese Experience, and Heritage Tourism—are hypothesized to be interconnected constructs that jointly influence tourists’ emotional satisfaction and behavioral intentions, such as their willingness to revisit the destination. SEM enables the examination of these relationships within a comprehensive framework, offering insights not only into the direct effects of each factor on outcome variables, but also into potential mediating or moderating effects that may exist among them. By applying SEM, the study seeks to validate the proposed hypotheses and assess the overall fit of the conceptual model, thereby contributing to the theoretical and practical understanding of how gastronomic heritage influences sustainable rural tourism behavior.

Y = βX + ζY

Roquefort-sur-Soulzon as a Model Destination for Cheese Heritage Tourism

Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, a village located in the Aveyron department of southern France’s Massif Central region, represents a paradigmatic case of how a local gastronomic product can anchor a sustainable rural tourism model []. As the sole authorized maturing zone for the world-renowned Roquefort cheese, this commune holds a distinguished status protected by the Appellation d’Origine Protégée (AOP) designation. The natural caves of Combalou Mountain provide the unique microclimatic conditions essential for the maturation of Roquefort cheese, thereby linking the product inextricably with its geographic and cultural terroir []. The village has strategically leveraged this cheese heritage to develop a multi-dimensional tourism offering that integrates sensory experience, heritage interpretation, and local economic support. A central component of this strategy is the cave tours and cheese museums operated by major producers such as Société, Papillon, and Gabriel Coulet []. These guided visits offer tourists insights into the natural geology of the Combalou caves, the artisanal cheese-aging process, and the historical narratives surrounding Roquefort production. The dramatic and naturally ventilated caves serve not only as production spaces but also as immersive heritage sites that reinforce the authenticity and specificity of the product. Tasting experiences and on-site retail further enhance the tourist encounter, offering visitors the opportunity to sample a variety of Roquefort cheeses paired with regional wines or culinary products. These experiences culminate in direct purchases from producers, fostering short food supply chains and reinforcing the role of local food systems in rural tourism economies. Roquefort-sur-Soulzon plays an integral role in broader agri-tourism and gastronomic networks, such as the “Route des Fromages AOP” in the Occitanie region []. These routes combine cheese-focused tourism with farm visits, artisan food workshops, and dining experiences in local establishments that feature Roquefort-based cuisine. Through these regional collaborations, Roquefort is positioned not only as a singular destination but as a node within a broader cultural landscape of French food heritage [].

The cultural significance of Roquefort is also celebrated through festivals and local events, which include fairs, workshops, culinary demonstrations, and storytelling performances that underscore cheese as a marker of local identity. These activities contribute to community engagement and deepen the visitor’s understanding of the cultural context surrounding the product. The destination places a strong emphasis on education around the AOP system and the concept of terroir []. By elucidating the strict geographic and methodological requirements that define Roquefort production, local stakeholders use tourism as a vehicle for promoting food authenticity, heritage conservation, and consumer awareness of geographic indications (GI). This educational dimension reinforces the unique relationship between place, production, and cultural value. As a case study, Roquefort-sur-Soulzon exemplifies how a local gastronomic product can function as a catalyst for sustainable rural tourism, one that interweaves sensory pleasure, cultural depth, and local development. The village stands as a benchmark for other rural destinations—such as Pirot or Sokobanja (Serbia), where cheese production and cave-based natural heritage also exist—demonstrating how place-based food identity can be transformed into an immersive and resilient tourism offering.

4. Results

To explore the underlying motivational dimensions driving visitation to Roquefort-sur-Soulzon—a destination renowned for its cheese heritage—an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.754, indicating an acceptable level of shared variance among variables, while Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity yielded a highly significant result (χ2 = 4152.815, df = 45, p < 0.001), confirming the data’s suitability for factor analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

KMO and Bartlett’s Test.

Three distinct factors were extracted based on eigenvalues greater than 1, cumulatively accounting for 84.781% of the total variance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Total Variance Explained.

These factors reflect coherent thematic groupings related to gastronomy, sensory experience and heritage, as follows (Table 3):

Table 3.

Factor Loadings for Tourist Motivations Related to Gastronomy, Heritage, and Cheese Experiences.

- Traditional Gastronomy (Factor 1): This factor captures tourists’ appreciation for regional and traditional food practices. It comprises high loadings from items such as: Food Heritage and Local Tasting. These results indicate that visitors are strongly motivated by the opportunity to engage with authentic local culinary practices, with a particular emphasis on cheese tasting and traditional food systems. Tourists’ exposure to traditional food production and local tasting opportunities leads to a heightened appreciation for regional gastronomy. The strong association with Food Heritage and Local Tasting indicates that engagement with authentic culinary practices results in the motivation to travel to destinations known for their traditional food systems. The cause—availability of traditional gastronomy—leads to the effect—motivation to explore and consume regional products on-site.

- Cheese Experience (Factor 2): The second factor is centered on the specific experiential appeal of Roquefort cheese. It is defined by the following items: Cheese Heritage, Authentic Tasting, Culinary Exploration, Cheese Indulgence. This dimension highlights the destination’s strong identity as a gastronomic attraction, with visitors motivated by opportunities to taste, explore, and indulge in Roquefort cheese as a key part of their travel experience. The prominence of Roquefort cheese as a culturally and gastronomically significant product causes tourists to associate the destination with a unique culinary identity. High loadings for Cheese Heritage, Authentic Tasting, Culinary Exploration, and Cheese Indulgence demonstrate that this product-centric experience stimulates curiosity, sensory exploration, and indulgence, thereby driving travel motivation. The cause—availability and heritage of Roquefort cheese—produces the effect—desire to taste, learn about, and enjoy cheese as a central component of the travel experience.

- Heritage Tourism (Factor 3): This factor reflects a broader cultural and heritage-oriented motivation for visiting Roquefort-sur-Soulzon. Items with strong loadings include Cultural Heritage, Cultural Immersion, Rural Escape, and Sustainable Traditions. These variables indicate that many tourists seek meaningful connections with the destination’s rural and cultural identity, including traditional lifestyles, sustainability values, and immersive experiences in a tranquil setting. The presence of cultural heritage elements and a rural environment leads tourists to seek immersion in local traditions and values. The factor includes Cultural Heritage, Cultural Immersion, Rural Escape, and Sustainable Traditions, showing that when tourists perceive a destination as rich in heritage and aligned with sustainability, it leads to the motivation to connect more deeply with place identity and to engage in culturally oriented travel behavior. The cause—cultural and rural authenticity—results in the effect—search for meaningful and immersive heritage experiences.

To ensure interpretability, individual questionnaire items were grouped under the three extracted factors based on their highest loadings and conceptual coherence: Factor 1: Traditional Gastronomy—This dimension captures tourists’ motivation to explore the destination through local food practices. It includes items such as Food Heritage (loading = 0.999), Local Tasting (0.952), and Sustainable Traditions (0.707). These items reflect interest in traditional, sustainable, and locally rooted culinary experiences that go beyond mere consumption to include ethical and cultural considerations. Factor 2: Cheese Experience—This factor represents a specific attraction to the Roquefort cheese itself, emphasizing experiential and sensory engagement. It includes items such as Cheese Heritage (0.910), Authentic Tasting (0.807), Culinary Exploration (0.836), and Cheese Indulgence (0.779). These reflect tourists’ desire to engage with the production, taste, and historical context of Roquefort cheese as a core part of their visit. Factor 3: Heritage Tourism—This dimension encompasses broader cultural motivations for travel, linked to a desire for immersion in local identity and rural escape. Items loading strongly here include Cultural Immersion (0.987), Cultural Heritage (0.756), and Rural Escape (0.779), which represent motivations to understand the culture, environment, and heritage of the region in a deeper, more meaningful way. The high loadings (all ≥ 0.70) indicate strong internal consistency and validate the conceptual grouping of questionnaire items under each motivational factor.

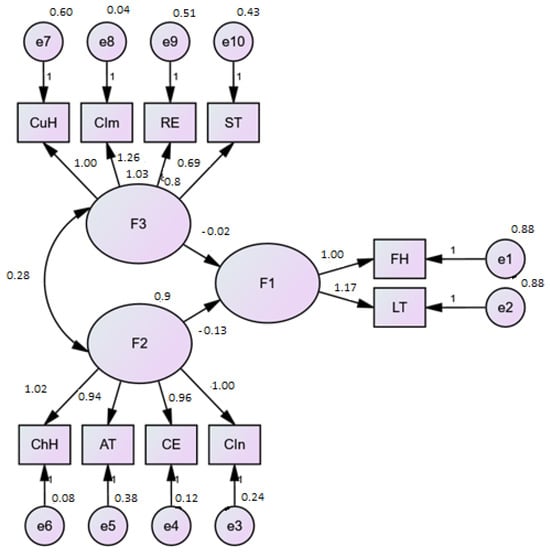

The presented Structural Equation Model (SEM) examines the complex interrelations between three latent constructs—Traditional Gastronomy (F1), Cheese Experience (F2), and Heritage Tourism (F3)—in the context of rural gastronomic tourism, using Roquefort-sur-Soulzon as the case study (Figure 1). The model tests how these latent variables influence tourist motivation and behavior, especially in relation to consuming and experiencing locally significant products such as Roquefort cheese. Factor 1: Traditional Gastronomy (F1) is conceptualized as a core motivational dimension reflecting tourists’ appreciation for destinations with a strong gastronomic identity. It is operationalized through two indicators: Food Heritage (FH), which measures the value tourists place on traditional food production methods, and Local Tasting (LT), which captures the importance of sampling local cheese during their stay. The factor loadings for FH (1.00) and LT (1.17) indicate a strong alignment with the latent variable, confirming that traditional gastronomy is a key experiential component of the destination’s identity.

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Source: Prepared by the authors (2025).

Factor 2: Cheese Experience (F2) represents the experiential and emotional engagement with the iconic product—Roquefort cheese. It includes four observed variables: Cheese Heritage (ChH), Authentic Tasting (AT), Culinary Exploration (CE), and Cheese Indulgence (CIn). High standardized loadings (ranging from 0.94 to 1.02) suggest that this factor effectively captures the depth of tourist interaction with cheese as a cultural, sensory, and learning experience. This construct reflects tourists’ desires to engage with the product both hedonically and intellectually.

Factor 3: Heritage Tourism (F3) captures broader motivational dimensions tied to the cultural and rural context of the destination. It includes Cultural Heritage (CuH), Cultural Immersion (Clm), Rural Escape (RE), and Sustainable Traditions (ST). These variables represent tourists’ motivations to connect with local customs, escape from urban routines, and support sustainable practices. The factor loadings range from 0.69 to 1.26, indicating a heterogeneous yet coherent construct that connects cultural identity with the appeal of rural, tradition-based tourism. In the structural equation model (SEM), the labels e1–e10 represent the error terms associated with each observed variable, which are survey items grouped under the latent constructs (Traditional Gastronomy, Cheese Experience, Heritage Tourism). These error terms account for the variance in the observed variables that is not explained by the latent factors.

The results of the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) provide empirical support for several of the proposed hypotheses: H1: “The multisensory experience of consuming traditional gastronomy (taste, smell, sight, touch) enhances tourists’ emotional and hedonic satisfaction, leading to a stronger desire to engage in food-related activities during their visit”. → Supported by the strong factor loadings of Food Heritage (0.999) and Local Tasting (0.952) within the Traditional Gastronomy factor. These findings indicate that sensory and hedonic elements of food consumption significantly contribute to tourists’ motivation; H2: “Tourists are more motivated to consume traditional gastronomy when it is perceived as an authentic representation of local heritage, which enhances their desire to understand the destination’s cultural identity”. → Confirmed through the significant contribution of Authentic Tasting (0.807) and Culinary Exploration (0.836) under the Cheese Experience factor, highlighting the role of authenticity in shaping gastronomic motivation; H3: “The heritage and cultural significance of Roquefort cheese motivate tourists to prioritize it as a key experiential activity during their visit, as they seek to engage with both the product and its historical narrative”. → Empirical support is evident from Cheese Heritage (0.910) and Cheese Indulgence (0.779) loading strongly on the Cheese Experience factor, indicating that the cultural narrative surrounding Roquefort cheese is a key experiential driver; H4: “Tourists are more motivated to engage with Roquefort cheese when the product’s heritage and artisanal status evoke emotional and intellectual curiosity, enhancing their desire to learn about its production and history”. → Supported by the inclusion of Culinary Exploration and Authentic Tasting, which represent affective and cognitive dimensions of curiosity, and their high loadings within the Cheese Experience factor; H5: “Tourists are more likely to engage in authentic cultural experiences (e.g., attending local festivals, participating in traditional food preparation) when they perceive these experiences as opportunities for self-discovery and personal connection to local identity”. → Supported by high factor loadings of Cultural Immersion (0.987) and Cultural Heritage (0.756) on the Heritage Tourism factor, demonstrating that visitors are drawn to cultural identity and meaning; H6: “The perceived contrast between rural and culturally rich environments and urbanized, globalized settings increases tourists’ desire for immersive cultural experiences, providing emotional resonance and a sense of escape from their daily routines”. → Strongly supported by Rural Escape (0.779) and Sustainable Traditions (0.707), confirming that the rural character of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon provides an emotional and experiential counterpoint to tourists’ everyday urban lives. The SEM model further confirms the structural relationships among the three latent factors and their contribution to the overarching motivational framework, reinforcing the multidimensional nature of tourist engagement with food, culture, and heritage. All of the model fitting indicators indicates an acceptable fit. A RMSEA value of 0.060 (between 0.050 and 0.080) indicates a good fit. Higher values (>0.90) of CFI (0.968), TLI (0.948) and GFI (0.930) indicates a good fit.

The standardized regression weights (Table 4) from a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis reveals the complex relationships between three latent constructs that capture different dimensions of tourist motivation in the context of cheese-centered rural tourism: Traditional Gastronomy (F1), Cheese Experience (F2), and Heritage Tourism (F3). A key finding from the model is the strong and negative relationship between F2 (Cheese Experience) and F1 (Traditional Gastronomy), with a standardized regression weight of −0.959. This negative coefficient suggests a counterintuitive dynamic: while one might expect deeper involvement in cheese-related experiences to reinforce appreciation for traditional gastronomy, the data indicate that visitors who are highly motivated by cheese-specific experiences may differentiate these from broader traditional food values. This may reflect a form of experiential specialization, whereby tourists are particularly drawn to the unique, immersive, and sensory attributes of Roquefort cheese and its production, and therefore engage with it as a standalone gastronomic attraction rather than as part of a broader culinary heritage framework. In contrast, the path from F3 (Heritage Tourism) to F1 (Traditional Gastronomy) is weak and negative (−0.112), suggesting that general heritage tourism motivations—such as interest in local culture, rural escape, and sustainability—have little explanatory power in shaping tourists’ perceptions of traditional food culture in this specific context. This implies that while tourists value the cultural and historical context of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, this appreciation does not necessarily extend to a broader engagement with traditional gastronomy unless it is explicitly tied to the cheese experience.

Table 4.

Standardized Regression Weights: (Group number 1—Default model).

Factor F1: Traditional Gastronomy is defined by two observed variables: Food Heritage (0.136) and Local Tasting (0.159). These loadings are relatively low, indicating that this construct is not strongly defined in the current model. The low factor loadings suggest that visitors do not view traditional food heritage or tasting experiences as major stand-alone components of their tourism motivation, unless these are tied specifically to the cheese-related context (captured under F2). This may also imply the need for stronger interpretative frameworks at the destination level to better connect local gastronomy with cultural storytelling and tradition.

Factor F2: Cheese Experience, by contrast, emerges as a robust and highly coherent construct, with very high factor loadings: Cheese Indulgence (0.892), Culinary Exploration (0.936), Authentic Tasting (0.826) and Cheese Heritage (0.961). This indicates that visitors to Roquefort-sur-Soulzon are highly motivated by a comprehensive and authentic cheese-related experience, including its history, production methods, sensory qualities, and the opportunity for indulgence. These findings underscore the centrality of the cheese product as a destination identity marker, capable of attracting tourists who are not only food-oriented but also deeply engaged in culinary discovery. The extremely high loading on Cheese Heritage suggests that storytelling and educational components related to the origins and tradition of Roquefort cheese are particularly impactful.

Factor 3 F3: Heritage Tourism is also well-defined, though slightly less cohesive than F2. Its observed variables load strongly: Cultural Heritage (0.764), Cultural Immersion (0.986), Rural Escape (0.801) and Sustainable Traditions (0.694). The high loading on Cultural Immersion indicates that experiencing the customs and lifestyle of the destination is of paramount importance. This supports the idea that Roquefort-sur-Soulzon is not merely seen as a site of production but as a living cultural landscape, where traditions, natural beauty, and rural charm play an integral role in the tourist experience. Furthermore, Rural Escape and Sustainable Traditions suggest that the destination appeals to values-driven tourists who seek peace, authenticity, and environmental or cultural sustainability.

5. Discussion

The results validate all six subhypotheses (Table 5), confirming the interconnected roles of traditional gastronomy, iconic food products like Roquefort cheese, and the authenticity of cultural and rural environments in motivating tourist behavior. Traditional gastronomy and cultural authenticity are not merely consumable features of a destination but serve as identity-building narratives through which tourists engage with place. The emotional and multisensory dimensions of food—particularly when tied to culturally significant items like Roquefort cheese—generate experiences that go beyond pleasure, entering the domains of meaning-making and identity expression. These findings enrich theoretical frameworks related to experiential tourism, cultural capital, and heritage consumption, particularly within rural tourism contexts.

Table 5.

Summary Table.

5.1. Traditional Gastronomy as a Multisensory and Motivational Driver (H1 & H2)

The availability of traditional gastronomy acts as a powerful trigger for tourist motivation, providing opportunities for authentic, multisensory, and emotionally rewarding experiences. This directly addresses the first key research question: How does the availability of traditional gastronomy lead to tourist motivation? Findings show that sensory stimulation—particularly anticipation of taste, smell, and visual appeal—plays a key role in attracting tourists. The symbolic role of traditional food as a cultural signal reinforces the sense of authenticity and uniqueness of place. Tourists are drawn not only by the flavor itself but also by what the food represents: cultural heritage, craftsmanship, and a sense of place. When tourists are aware that a destination offers traditional cuisine, sensory anticipation is activated—sight, taste, smell, and even imagined texture come into play. This pre-travel activation is supported by promotional narratives, word-of-mouth, and media representations that imbue traditional foods with emotional and cultural significance. The presence of traditional dishes on-site transforms abstract interest into tangible action, reinforcing the motivation to explore and consume locally. These dynamics align with the notion that food acts as a pre-consumption attractor, where the promise of authenticity and multisensory pleasure becomes a travel motivator in itself. Additionally, the symbolic value of gastronomy as a marker of identity supports the cultural dimension of motivation—tourists seek not just flavor but connection to place, heritage, and local life. This supports H1, confirming that the multisensory appeal of gastronomy significantly enhances emotional and hedonic satisfaction, which in turn motivates deeper engagement.

While initial motivations are shaped by sensory anticipation and symbolic associations, it is equally important to examine the underlying emotional and cultural dynamics that drive tourists toward direct, on-site engagement with local cuisine. This deeper perspective brings into focus a more nuanced layer of gastronomic tourism: Why does traditional gastronomy motivate tourists to explore and consume on-site? This question unpacks the deeper psychological and cultural motives behind tourist behavior. The findings highlight tourists’ desire for authenticity, immersive sensory experiences, and emotional gratification. Food becomes a medium through which visitors perform identity, express values like sustainability and cultural appreciation, and access local narratives. Tourists are not merely drawn by flavor but by the embodied cultural experience that tasting provides. Food tourism becomes a form of lifestyle expression: engaging with slow, traditional food practices acts as a personal statement of values—authenticity, sustainability, and cultural curiosity. Consumption on-site allows tourists to integrate the destination’s story into their own identity narratives, creating a sense of emotional and performative participation. Moreover, the hedonic and multisensory pleasure derived from local foods is intensified through narrative framing—stories of origin, craft, and tradition deepen the experience and embed it within the cultural landscape of the destination. Thus, gastronomy becomes a mechanism through which tourists simultaneously experience pleasure, meaning, and self-affirmation. These insights confirm H2, affirming that traditional gastronomy, when perceived as authentically linked to local heritage, becomes a compelling reason for tourists to seek out direct, on-site experiences.

Traditional gastronomy emerges as a strong motivational factor by offering tourists the opportunity for authentic, emotionally resonant, and multisensory experiences. This directly addresses the first research question: How does the availability of traditional gastronomy lead to tourist motivation? The data reveal that sensory anticipation—especially related to taste, smell, and visual appeal—significantly shapes travel intent. Traditional food operates as both a physical pleasure and a symbolic representation of cultural heritage, craftsmanship, and a sense of place. Tourists are not only drawn to the sensory qualities of traditional cuisine but also to its deeper meanings. Promotional materials, word-of-mouth, and media portrayals imbue these foods with emotional and cultural value even before travel begins. On-site experiences transform abstract interest into concrete engagement, as tourists actively seek out local dishes to explore and consume. This supports H1, affirming that the multisensory and emotional dimensions of traditional food enhance hedonic satisfaction and stimulate stronger tourist motivation. Going further, it is essential to ask: Why does traditional gastronomy motivate tourists to explore and consume on-site? Beyond anticipation, the desire for authenticity and emotional connection becomes central. Food becomes a cultural gateway through which tourists perform personal identity, express values such as sustainability and curiosity, and participate in local narratives. The act of eating local food becomes a statement about one’s lifestyle and preferences, reinforcing a sense of belonging and emotional immersion. Narratives surrounding origin, craft, and tradition further deepen these experiences. Therefore, H2 is confirmed—when gastronomy is perceived as genuinely linked to local heritage, it not only attracts tourists but also fosters deep emotional and cultural engagement.

5.2. Roquefort Cheese as a Central Experiential Anchor (H3 & H4)

Roquefort cheese functions not only as a food product but as a heritage symbol, anchoring the tourist experience and shaping travel behavior. This is directly tied to the question: How does the availability and heritage of Roquefort cheese lead to desire to taste, learn about, and enjoy it as a central component of the travel experience? Roquefort cheese represents a prime example of how a product becomes a destination anchor. The findings confirm H3 by showing that the intertwining of product and place (through PDO status, artisanal methods, and historical prestige) enhances its attractiveness far beyond culinary interest. The ability to witness traditional production, interact with local cheesemakers, and explore the aging caves contributes to a deep engagement that is at once educational, sensory, and emotional. Tourists are not just tasting cheese—they are participating in a heritage narrative, accessing layers of place identity through the product. Roquefort becomes a focal point of the visit, with tourists prioritizing experiences around it—be it tours, tastings, or workshops—thus transforming the cheese into both a symbolic and embodied experience. Roquefort’s PDO status, deep-rooted traditions, and strong place identity contribute to its elevated value in the eyes of tourists. The possibility to visit cheese caves, observe artisanal processes, and interact with local producers offers immediate and multisensory access, enhancing tourists’ desire to consume and learn. This confirms H3, showing that Roquefort is not just consumed but experienced as part of the region’s cultural identity.

In addition to its role as a gastronomic attraction, Roquefort cheese emerges as a powerful symbol of place-based identity, offering tourists a gateway into the cultural fabric of the region. To understand the depth of its impact on travel motivation and behavior, it is necessary to explore the mechanisms through which its heritage and availability generate such strong appeal: Why does the availability and heritage of Roquefort cheese produce this effect? H4 is confirmed by the synthesis of various motivators: sensory pleasure, intellectual stimulation, and cultural value. Roquefort cheese becomes more than a product—it is an object of cultural consumption, embodying the values and identity of the region. The tourists’ motivation is enhanced by pre-travel expectations shaped by place branding and cultural discourse. Upon arrival, these expectations are met and often exceeded through multisensory experiences and behind-the-scenes access to production. The result is not merely enjoyment but meaningful learning and cultural appreciation. The cheese functions as a gateway into the regional way of life, reinforcing the travel experience as one of discovery, respect, and identity construction. In this way, food heritage contributes to a layered tourism experience, satisfying a spectrum of motives—emotional, cognitive, symbolic, and experiential. Findings indicate that the cheese’s emotional, cultural, and intellectual appeal drives motivation. Its story, historical relevance, and artisanal production evoke curiosity and emotional connection. Tourists experience this product as a gateway to understanding local culture, reinforcing its status as a central part of the journey. Expectations formed before travel further amplify this effect, as tourists arrive with a pre-defined interest in engaging with the product. Thus, H4 is confirmed: the availability and symbolic value of Roquefort cheese create strong emotional and cognitive engagement, shaping tourists’ behavior and anchoring it in the local heritage context.

5.3. Cultural and Rural Authenticity as a Catalyst for Immersive Experiences (H5 & H6)

Cultural and rural authenticity acts as a stimulus for immersive tourism, fostering emotional, cultural, and intellectual engagement. This is especially relevant for the research question: How does cultural and rural authenticity lead to immersive heritage experiences? Tourists respond to the presence of authentic cultural markers—such as architecture, food practices, and festivals—by actively seeking participatory experiences. These include hands-on involvement in traditions, rather than passive observation. Authenticity functions here not as a passive backdrop but as an active catalyst—a perceived invitation for deeper exploration. Tourists respond to the contextual cues of authenticity (e.g., architectural styles, artisanal practices, local narratives) by seeking engagement rather than observation. This authenticity is experiential and embodied: travelers are invited to attend festivals, join workshops, or share meals prepared with traditional methods. These opportunities offer emotional depth and cultural intimacy, transforming the tourist from observer to participant. Immersion in authentic settings satisfies the postmodern tourist’s need for meaning-making, creating transformative experiences rooted in emotional resonance and social connection. The second factor from the data confirmed that authenticity enhances emotional resonance and psychological fulfillment. This finding supports H5, emphasizing that authentic experiences promote self-discovery and deeper connection with local identity.

Beyond observable behaviors and preferences, it is also essential to explore the underlying psychological motivations that drive tourists toward immersive encounters with authenticity. This deeper layer of analysis addresses a key dimension of experiential tourism: Why does cultural and rural authenticity trigger desire for meaningful and immersive heritage experiences? The psychological mechanisms revealed through the data indicate that authenticity fulfills a search for meaning, contrast, and transformation. Tourists often escape urban routines to find simplicity, emotional depth, and historical continuity in rural environments. The narrative power of cultural practices allows tourists to feel part of a story, elevating their engagement. In confirming H6, the analysis underscores the internal psychological processes that are activated when tourists perceive authenticity. These mechanisms include identity-seeking (e.g., connecting with a purer, more rooted way of life), escapism (from the globalized, fast-paced world), and narrative immersion (the opportunity to “step into” a cultural story). The authentic environment functions like a stage upon which tourists project and perform their own desires for meaning, belonging, and discovery. The emotional and intellectual satisfaction derived from such engagement is profound, as it links leisure with personal growth and cultural capital acquisition. Rural spaces, in particular, act as psychological and symbolic counterpoints to urban life, reinforcing their appeal as meaningful and restorative destinations. These elements validate H6, illustrating how the contrast between rural authenticity and urban uniformity drives desire for transformative tourism experiences. Overall, the findings affirm that traditional gastronomy and cultural authenticity operate as more than static attractions—they are dynamic, multisensory, and symbolic resources that co-create meaning with tourists. This study thus contributes to a nuanced understanding of how emotional, sensory, and cultural factors intersect to shape contemporary rural tourism behavior and deepen place attachment.

5.4. Understanding Factor Interactions in Rural Cheese Tourism

The SEM reveals several important inter-factor relationships. Firstly, the structural model reveals a negative regression path from Cheese Experience (F2) to Traditional Gastronomy (F1) (β = −0.13). This inverse relationship may at first seem counterintuitive, as one might expect a positive association between specific and general gastronomic interests. However, a closer examination suggests a specialization effect: tourists who are highly motivated by cheese-related experiences (e.g., artisanal production, farm visits, curated tastings) may deliberately prioritize deep, niche engagements over broad culinary exploration. In this context, traditional gastronomy may be perceived as too generalized or commercialized, lacking the perceived authenticity or intimacy associated with localized cheese culture. This pattern could reflect a form of experiential segmentation, where tourists identify as “food specialists” (in this case, cheese connoisseurs or enthusiasts) rather than generalist food tourists. Such travelers might pursue immersive and educational experiences tied to terroir, production methods, and artisanal heritage, which are distinct from the broader consumption-based experiences often marketed as traditional gastronomy. These findings align with literature emphasizing the rise of hyper-personalized and identity-driven tourism preferences, particularly in slow food and agri-tourism contexts.

Secondly, there is a moderate correlation between F2 and F3 (path coefficient = 0.28), confirming that cheese-related experiences are intertwined with broader heritage and rural tourism motivations. A weaker but notable connection exists between F3 and F1 (path coefficient = −0.02), pointing to the possibility that while heritage tourism complements traditional gastronomy, the motivational emphasis may vary between different tourist profiles. The model validates the theoretical assumption that products such as Roquefort cheese function not only as gastronomic commodities but also as carriers of destination identity.

The integration of cheese heritage, cultural authenticity, and sustainable rural values contributes to a cohesive tourism experience that appeals to both hedonic and learning-oriented motivations. This analysis supports the overarching hypothesis H that a local gastronomic product—like Roquefort or Kačkavalj cheese—can serve as a key driver for sustainable rural tourism development, enhancing the destination’s identity and contributing to immersive, meaningful tourist experiences. The SEM results point to several strategic implications for sustainable rural tourism development centered around cave-aged cheese as a unique local product. The strong internal coherence of the Cheese Experience construct (F2) suggests that Roquefort cheese has significant potential as a destination brand anchor. It is more than just a product—it is an experience that blends education, taste, indulgence, and tradition. However, the disconnect between F2 and F1 warns against assuming that gastronomic tourism broadly defined (e.g., interest in all traditional foods) automatically overlaps with cheese tourism. This differentiation can be leveraged in marketing—for instance, by positioning Roquefort not only as a culinary highlight but as a gateway to a specific niche within gastronomic tourism.

The strong definition of Heritage Tourism (F3) points to the importance of embedding cheese tourism within a broader cultural narrative, one that includes immersive and sustainable experiences. Cheese caves, traditional methods, rural settings, and cultural performances can all contribute to reinforcing this holistic appeal. The SEM analysis underscores that cheese tourism represents a powerful and distinct motivational domain within rural tourism. While it intersects with traditional gastronomy and heritage tourism, it also stands on its own as a highly structured and motivationally potent experience. For destinations like Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, this presents a valuable opportunity to craft targeted offerings that not only celebrate the sensory and historical dimensions of cheese but also connect them with local identity, sustainability, and immersive rural charm.

While the findings provide meaningful insights into the motivational dynamics of rural cheese tourism, certain limitations must be acknowledged. First, the study was conducted in a single geographical location (Roquefort-sur-Soulzon), which may limit the generalizability of the results to other rural or gastronomic contexts. Second, the data collection took place during a specific season, potentially introducing a seasonal bias, as tourist motivations and behavior may vary across different times of the year. Third, although the sample size was sufficient for statistical analysis, the demographic profile of the respondents (e.g., age, nationality, education level) may have influenced the results in ways that are not fully representative of the broader tourist population. Future research should explore longitudinal and comparative approaches across multiple regions and seasons to validate and extend the findings. Additionally, qualitative insights from local producers and tourists could enrich the understanding of sensory, emotional, and identity-based dimensions of gastronomic tourism.

Building on the current findings, future research could benefit from replicating this study in other regions known for strong gastronomic or cheese-based identities—such as Tuscany (Italy), Asturias (Spain), or Šumadija (Serbia)—to test the robustness and transferability of the proposed model. A comparative cross-cultural approach would help identify both universal and region-specific motivational patterns. Additionally, longitudinal research could track how tourist motivations evolve over time, particularly in response to seasonal changes, sustainability trends, or destination branding efforts. Incorporating mixed methods—including in-depth interviews, ethnographic observation, and sensory ethnography—would provide richer insight into the emotional and symbolic dimensions of gastronomic engagement. Such approaches could further explore how tourists co-construct meaning through food-related experiences, and how this contributes to sustained place attachment and rural tourism development.

5.5. Interpretation of Findings in Light of Existing Literature

The findings of this study extend and nuance previous research on gastronomic and rural heritage tourism. Consistent with Lee at al. [] and Lin et al. [] the multisensory appeal of traditional food was confirmed as a key motivator for travel. The symbolic and emotional dimensions observed in this study also align with findings by Kaman and Yazicioğlu [], who emphasized food as a cultural marker. Moreover, the identification of cheese heritage (e.g., Roquefort) as a distinct motivational construct reinforces insights by Sims [] but goes further by highlighting the structural independence of niche cheese tourism from broader gastronomy. The confirmation of authenticity as a catalyst for immersive experiences is also in line with Hsu et al. [] though this study contributes by unpacking the emotional and psychological mechanisms underpinning such engagement. Overall, the results validate and deepen prior theoretical frameworks while also offering new empirical evidence for how sensory, cultural, and symbolic dimensions of food interact in rural tourism contexts.

5.6. Practical Implications

The findings of this study carry valuable practical implications for rural tourism development, particularly in destinations aiming to leverage traditional food heritage as a driver of experiential tourism. The case of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon demonstrates how a singular product—cave-aged Roquefort cheese—can transcend its role as a food item and become a central element in shaping destination identity and tourist motivations. The structural equation model highlights the dominant influence of the cheese experience (F2) on visitors’ engagement with the destination, indicating that activities such as cheese indulgence, culinary exploration, and learning about cheese heritage constitute the most impactful dimensions of the visitor experience. This insight is directly applicable to similar rural destinations such as Pirot and Sokobanja in Serbia, where kačkavalj cheese and natural cave environments represent untapped potential for niche tourism development. To replicate the success observed in Roquefort, these destinations should focus on developing an integrated cheese-centered experience. This includes the formalization of cheese routes, the establishment of interactive visitor centers, and the inclusion of cheese tastings within authentic rural settings.

Local producers should be positioned as cultural mediators, actively engaging with tourists through storytelling, workshops, and demonstrations, thus transforming traditional production processes into immersive tourist experiences. The Roquefort model shows that heritage tourism (F3) elements—such as cultural immersion, rural escape, and sustainable traditions—strongly complement the core gastronomic experience. These elements can be strategically reinforced in Pirot and Sokobanja through the development of rural trails, eco-cultural interpretation, and culinary events that celebrate regional identity and foster deeper connections between visitors and local traditions. The existence of caves in these Serbian destinations also provides opportunities to creatively link natural assets with cheese production narratives, potentially framing caves as symbolic or functional components in the aging or presentation of cheese, thus enhancing authenticity.

However, the SEM results from Roquefort also suggest that traditional gastronomy (F1)—though thematically related—is not automatically activated by cheese-related motivations, as evidenced by its negative relationship with the core cheese experience factor. This underlines the need for careful curation and integration of gastronomic offerings. In practical terms, stakeholders in Pirot and Sokobanja should work to embed kačkavalj more prominently into local cuisine, restaurant menus, and food festivals, thus reinforcing its role as a symbol of place and culinary heritage. Finally, the broader implications for sustainable rural development are notable. Developing cheese-based tourism in destinations like Pirot and Sokobanja aligns with principles of community-based tourism, economic diversification, and territorial branding. By positioning local cheese production within a holistic tourism offering, these areas can foster rural revitalization, preserve cultural landscapes, and promote environmentally responsible visitation. The intersection of food heritage, cave tourism, and rural identity offers a unique pathway for destinations to build resilience, attract niche markets, and cultivate meaningful visitor experiences grounded in local authenticity.

6. Conclusions