Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to present the situation of Polish care farms in the context of legal and economic conditions. The need to analyze this topic arises from the current lack of literature that has synthetically addressed the challenges posed by the ageing population in the European Union, including in Poland. The research gap revealed by the authors is especially prominent when it comes to aspects related to the setting up and running of care farms in Poland. Therefore, this paper analyzes the legal forms of establishing a care farm. Next, it discusses the economic aspects of how care farms operate. Based on research materials, especially including those retrieved through the use of the formal dogmatic approach, the authors determined the formal conditions for the setting up and successive running of care farms. The authors have analyzed with the help of formal dogma the forms of running care farms in Poland referring to the current legislation, as well as the position presented in the literature. Also, due to the method used in analyzing the materials collected in this study, the authors have presented their views on how to finance such facilities. Findings from this research confirm that Polish care farms have promising outlooks as they respond to the changing needs of an ageing society. Moreover, as a result of the formal dogmatics method used, it was found that in Poland the most common form of running a care farm is an association. This is because the establishment of an association does not require the fulfillment of many legal criteria as is the case with a sole proprietorship. For this reason, those interested in starting a care farm may opt for the association form.

1. Introduction

Sustainable multipurpose rural development is the actual evolution path of rural areas, and is stimulated by the modern transformation of humanity. Currently, Poland has witnessed growing interest in social farming: a new and innovative field of business and an approach which consists of enhancing existing agricultural holdings, organic farms and agri-tourism establishments with social services. The development of care farms and their offering of care and therapy services has been increasingly addressed in Europe for many years now (including in the Netherlands, Ireland and Germany), although the aspects covered by care farming differ between countries [1,2,3,4,5,6,7] due to several major reasons. First, European countries differ in the way such businesses are organized. This mostly includes the legal aspects of how they are established and how they operate. Second, there are differences in how their care services are financed. Third, it is also crucial to indicate an adequate target group for care services, which involves ensuring appropriate safety measures on the farm [8,9].

In an effort to ensure the highest-quality services and professionalism, farm owners modernize and upgrade their facilities, embark on a specialization path and offer increasingly better products and services that are supposed to provide a more precise response to what different customers expect [10]. Therefore, the research purpose of this paper is to determine the legal and economic potential for the setting up and developing such businesses in rural areas.

2. Materials and Methods

The purpose of this paper is to describe the development status of care farms, illustrated by the example of Poland, in the context of legal regulations and economic conditions. A review was carried out of selected scientific publications on the role and importance of social farming, with particular emphasis on care farms. It follows from this that the literature has been focused on using different methods and tools to highlight the underlying problems. The authors relied on a number of papers and reports prepared by multiple authorities, including European institutions in charge of dealing with the problems of an ageing society [11,12]. Also, information was retrieved from Polish government sources (including government agencies and operators in charge of implementing practices for care services) as well as publications on projects aimed at implementing the concept of care farming in Poland. The requirements and expectations for offering care services were described based on the analysis of national and European strategic documents, including the National Strategic Plan under the EU Common Agricultural Policy for 2023–2027, the European Green Deal and other documents and declarations. This study relies on different kinds of inventories and databases. In order to monitor the number and diversity of care farms, the authors used the database kept by the Kuyavian–Pomeranian Agricultural Consultancy Center in Minikowo, which implemented a number of pioneering projects with a total of 30 care farms. Their database includes such aspects as the financing mechanism of Polish care services, openness to specific customer groups and the basic characteristics of agricultural activities of each farm. At the same time, this study uses the formal dogmatic method with a view to interpreting the provisions set forth in normative acts relating to the legal forms of running a care farm.

3. Social Farming vs. Social Economy: Rural Development Outlooks

The concept of sustainability has been around for many years and is a multi-faceted category. It is of interest to numerous researchers: sociologists, economists, ecologists, political scientists, lawyers and urban planners. In recent years, researchers, especially economists as highlighted by [13,14,15], have carried out a number of different analyses on this concept, focusing attention on the process of its implementation into practice. Analyzing the literature on the subject, sustainable development was initially viewed from an ecological perspective later spreading into the fields within the social sciences, including economics. This was due to the fact that, until the 1970s, economic growth was linked to consumerism in society and this placed strong pressure on the environment, causing its numerous degradations and pollutions [13]. Today, the concept of sustainable development faces many challenges. The ecological crisis, the uncertain geopolitical situation and the growing demands and expectations of producers and consumers undoubtedly contribute to numerous disruptions in many social and economic dimensions. The response to all of these challenges is to be found in the document produced by the United Nations on Sustainable Development Goals [16] developed at the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development held in June 2012 in Rio de Ja-neiro.

This document contains 17 Sustainable Development Goals and an associated 169 actions to be achieved by all national governments, international organizations, NGOs, the science and business sectors and citizens. They center around five areas: people, planet, prosperity, peace and partnership [16]. Analyzing the individual objectives and measures, it can be seen that it is important to emphasize the role of rural areas in creating new, innovative solutions in the field of social farming and the social economy.

In former times, the countryside was understood as a place where food and agricultural raw materials were produced. In addition, it provided goods and services that were necessary for agricultural production. Currently, rural areas have many functions in addition to their production function [17,18,19]. These include consumption, tourism, care and service functions. As rural areas evolve, they continuously develop and witness a declining share of agriculture. Development can be understood as economic growth with concomitant changes in areas such as the creation of new jobs or the improvement of professional qualifications and skills [14]. Development is mainly related to the improvement of the living conditions of the population, regardless of age, gender or place of residence. The development of rural areas is linked to the functions they perform, i.e., agricultural functions and non-agricultural functions [20]. Consequently, the development of these areas can take place in two ways: through agricultural development and multifunctional development. The development of non-agricultural functions is linked to the concept of the multifunctionality of rural areas. The as-sumption behind it is that in addition to providing food and agricultural raw materials, agriculture can also ensure many non-market benefits to the population.

Currently, we can observe that in today’s world, where social and economic inequalities are increasing between countries and populations, etc., and environmental problems facing the world are becoming very pressing, new solutions are needed. For this reason, sustainable development sees the social economy as one that can offer concrete solutions [21]. Firstly, it gives us the right tools to fight poverty and social exclusion and secondly, it plays an important role in urban and rural development and supports civil society building processes [22].

An example of such activities is the promotion of social entrepreneurship, i.e., economic activity based on social and environmental values, creating jobs that firstly generate profit and secondly contribute to the development of local communities and environmental protection [23]. In rural areas, the development of entrepreneurship, becomes an important stimulus for the launching of many initiatives, including social and care integration. This is of great importance because social farming as part of the concept of multifunctional and sustainable development is evolving, and is increasingly becoming part of not only scientific but practical and business discourse.

In Poland, rural areas and agricultural land account for 85% and 52% of the national territory, respectively. In Europe, the beginnings of social farming are estimated to date back to the second half of the 19th century. At that time, farms and institutions were established in rural and remote areas to take care of the older adults or intellectually disabled people. Between the 1970s and the 1990s, care farms started to be established and organized in many European countries, including in the Netherlands, which is considered to be the cradle of care farming. While countries such as Germany, Italy and Ireland also witnessed the development of care businesses, the reasons behind the growth of social farming in these areas differed [23,24,25].

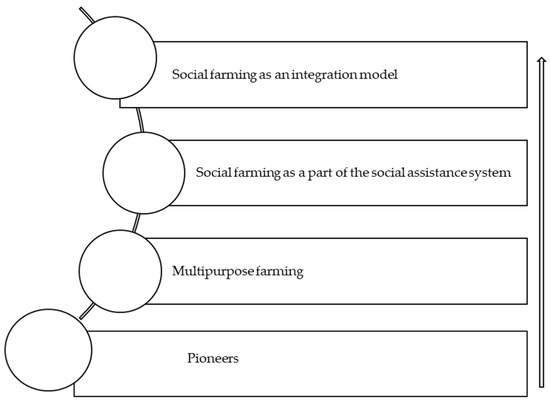

In Italy, a significant driver was the mass closure of psychiatric hospitals. In Germany, in turn, a number of institutions in charge of supporting marginalized people were closed. Conversely, in the Netherlands and Ireland, that trend was fueled by religious movements and communities [24]. According to ample literature, the developmental history of social farming can be divided into four periods [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Development of social farming. Source: [26].

The first period was that of pioneering efforts, i.e., the very few examples of care farming businesses were mostly established on the initiative of private agricultural holdings. At that time, there was little social awareness of how they operated. The pioneering stage was witnessed in countries such as Austria, Finland and Sweden. The next stage was multipurpose farming, with a growing role and importance placed on social farming. Although social farming slowly started to be supported with funds allocated to agriculture and rural development, social awareness continued to be low. In the next stage, farming was already viewed as a component of the social care system. There was wide interest in social farms which were considered as professional providers of adequate quality services. The assumption behind the last development stage is that social farming came to be viewed as an integration model. Social farming had come to be seen as part of the agricultural sector and of the social assistance system. The Netherlands and France are examples of countries where the integration model is already in place [27].

The specific social farming activities in each of these phases are similar in the European countries; however, there are many differences between the countries due to several aspects. Firstly, there is the history and the approach and orientation of welfare activities. An institutional approach with a strong predominance of public institutions (especially health services) has been seen in France, Germany, Ireland and others [28]. Another approach was private. It was mainly based on therapeutic farms, where much attention was focused on providing adequate rehabilitation and treatment to the clients. This approach was known and widely used in the Netherlands and Belgium. The last approach is the so-called mixed approach. It is based on the creation and operation of social cooperatives and private farms. This approach has been found, among others, in Italy [29].

In the literature, it is very often pointed out that in Italy or France social farming is linked to the social and care sector; in the Netherlands to the health sector; and in Germany and Ireland it can be situated between the social and health sectors [28]. A good example of a country where social farming has an integrated role is the Netherlands. Thanks to the cooperation of several ministries (e.g., Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality) it is possible to co-operate, exchange experiences and adequately finance care activities. This benefits both the service providers and the guests themselves. This is important because contact with nature, with animals, is an important part of the respective therapy, depending on who the service recipient is [30]. Due to the development of social farming, it has developed in different phases taking into account specific needs and trying to respond to specific problems. In the initial phase, there were few farms, where it was not entirely clear how this care was to function and on what basis. However, as time went on and rural areas developed, it was noticed that these areas were an excellent place to combine agriculture and care by creating non-agricultural activities such as care farms.

Based on the analysis of different definitions of social farming, as proposed by some researchers [31,32,33,34], it can be noticed that in accordance with the interpretation provided by the Economic and Social Committee in a dedicated document, “Social farming is an innovative approach that brings together two concepts: multipurpose farming and social services. First, in addition to meeting production needs, it also addresses the aspect of social, economic, environmental and cultural integration. In meeting these needs, farms may take measures in the area of social rehabilitation, social integration, educational therapy, and care services for the elderly. Second, it has a positive impact on the way people feel, and integrates socially excluded persons” [34,35].

In turn, Di Iacovo and O’Connor [36] indicated in their study that social farming uses measures which rely on agricultural (i.e., vegetable and animal) resources to offer therapy, rehabilitation, social integration, education and social services. This is strictly related to “agricultural activities where (small) groups of people can stay and work together with family farmers and experience social practices” [36]. Hence, social farming spans agri-tourism farms, agricultural holdings and social gardens whose basic activity consists in integrating physically, mentally or emotionally disabled people as well as older adults, children and youth [37]. In turn, [1] has indicated that social farming includes measures that address current social and care needs.

When referring to social farming, the literature uses the following terms interchangeably: care farming, green care, green exercise and green therapies. These terms refer to different measures and practices relating to social integration and activities taken to help the excluded, lonely and older adults, etc. [37,38,39,40].

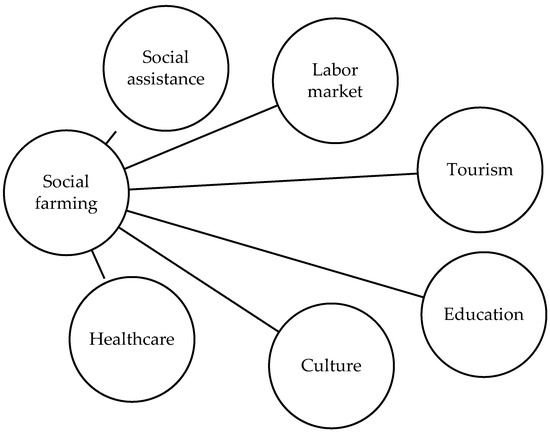

In turn according to [Figure 2], [24], social farming addresses six main components that encroach upon one another in delivering care services because they relate to aspects such as educating the society, building cultural awareness and identity, providing healthcare and, last but not least, offering social assistance in broad terms. Thus, social farming forms [38,40] a broad portfolio of services designed to improve the visitors’ mental health, alleviate their intellectual impairments and take care of older adults. The scope of these services is delivered through care farms, which makes it possible for the farmers to join and integrate with local communities by opening their farms to that concept [41].

Figure 2.

Areas of social farming. Source: [24].

Social economy is a crucial element of social farming (and of other concepts), and should therefore be viewed as a major component in a strong modern economy [42]. The term “social economy” is defined as an activity which is most characteristic in that rather than being profit-oriented, it is based on social needs. Its attributes include taking care of older adults, combating social exclusion, creating new jobs and providing social services in accordance with what the society demands [43,44,45]. In turn, [46] has indicated that social economy is a term related to any forms of social activity combined with economic activity, even if the extent of it is not large enough for the operators to be considered enterprises. The literature on the subject points to a highly general definition of social economy in which social goals take precedence over economic profits and which is underpinned by the principles of democracy, flexibility, innovativeness and voluntary participation. In European Union countries, social economy has been widely discussed for a long time now. Because of the increasingly rapid development of the social economy sector, both national and European legislators have started to introduce separate regulations applicable to it, to the measures it takes and to organizations operating in it.

In Poland, social economy is defined as an “area of civic activity which—through its economic and public benefit activities—supports social and professional integration of people at risk of social marginalization; the creation of jobs; the delivery of public social services (which serve the general interest); and local development” [47].

At the national level, pursuant to Article 20 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland [48] of 2 April 1997, social economy shall mean “an economic activity based on solidarity and collaboration between social operators which lay at the core of the economic system. The Act sets forth the fundamental values of social economy, i.e., autonomous activity, solidarity and collaboration between operators”. In turn, according to the analysis of Union legislation carried out by the Committee of four main types of operators active in social economy (CEP-CMAF), social economy is composed of economic and social operators. Conversely, the Flemish Confederation of Social Economy (VOSEC) defined social economy as “initiatives and enterprises whose main goal is to create social benefits and comply with the following principles: providing services to local communities is considered to be the overarching goal; labor takes precedence over capital; decisions are made democratically; and a commitment is in place to reinforcing the credibility and sustainability of activities” [49]. In turn, the European Research Network (EMES) stated that operators active in the social area should seek common social goals instead of being profit-oriented [50].

The term “social economy” can also be addressed in a dual way, i.e., from an institutional and legal approach, and from a normative approach. The former largely consists in defining the legal form of operators in areas where they serve social goals; the latter focuses on the principles and characteristics of social initiatives which make them stand apart from the private and public sectors [51].

In Poland, social economy is a term that has only been in use for a short time, and it has not been clearly defined [52]. However, the literature on the subject provides a couple of definitions for social economy, also referred to as civic economy, supportive economy, socioeconomy, the economy of solidarity or collaborative economy. Irrespective of the above, providers of social services hold a central place in social agriculture and social economy, and include care farms. The term “care farm” and related topics are among the new phenomena which are not widely known to the public, especially in Poland. In Polish realities, “care farm” is a term used interchangeably with “social farming” or “social agriculture” [53]. Care farms emerged and started to grow in the second half of the 20th century; at that time, older adults and the sick received assistance from care institutions, mostly located in rural areas and partly in cities [54]. Hence, a care farm is a concept that combines farming activities (based on available agricultural resources) with care and integration services intended for those in need.

4. Situation of Care Farms in Poland

In Poland, there are over 43,000 villages which are home to 15 million people, i.e., nearly 40% of the total population [55]. Rural family farms differ in their financial situation, which is mainly due to several issues. First, rural areas continue to witness low levels of income derived from agricultural production. Second, unemployment rates are quite high. Unfortunately, there is persistent lack of collaboration and integration between farmers and the local community. Hence, the mix of the rural population’s revenue streams evolved as years went by. Currently, an own farm is neither the basic nor a satisfactory income stream for agricultural holdings [56,57,58,59]. This makes farmers seek additional sources of financing with a view to enhance their quality and standards of living. The farmers’ and their families’ quest for more incomes resulted in the emergence of what is referred to as multi-skilling in rural areas. It means that farmers, or their farm members, work outside their agricultural holding (e.g., in an enterprise) or engage in a non-agricultural activity. Multipurpose rural development and mobility involved in multi-skilling made the rural population open to solutions for creating, implementing and promoting new forms of economic activity, primarily including non-agricultural businesses. This is mostly the case for small farmers. One possible form of non-agricultural activity would be to run a care farm.

In Poland, care farming is a novelty that might provide an alternative area of activity for farms (especially for small semi-subsistence holdings and agri-tourism establishments). The demographic change that affects the entire European Union is a factor that fosters the setting up and development of care farms. In Poland, between 2009 and 2019, the number of people aged 60+ and 65+ increased by more than 2 million (from 6.3 to 8.4 million). According to population forecasts, the number of seniors is supposed to exceed 9.9 million by 2050 [60]. That trend is also true for rural dwellers. Currently, rural areas experience growth in the older adult population, and the multigenerational family model is no longer the prevailing one [61]. As there are virtually no care facilities for older adults in rural areas, it seems that care farms might become a place where a number of people, including seniors, would be provided with comprehensive services.

In Poland, the setting up of care farms started under two projects named “Green Care 2016–2018” and “Care farm 2018–2020”, which involved the participation of thirty farms from the Kujawsko–Pomorskie voivodeship. These projects were implemented under the 2014–2020 Regional Operating Program of the Kujawsko–Pomorskie voivodeship by several authorities, including the Kuyavian–Pomeranian Agricultural Consultancy Center in Minikowo [62]. The next project “Acting autonomously (but not alone) 2019–2023” was also implemented by the Kuyavian–Pomeranian Agricultural Consultancy Center in Minikowo in partnership with the Local Action Group “Tuchola Forest”, the Tuchola District Center for Family Assistance, the “Koło” Polish Association for the Mentally Impaired in Chojnice, and the Association of Parents of Children with Special Needs in Tuchola as part of Measure 4.1 Social innovations for 2019–2023 [Table 1] [63]. The two first projects provided for the establishment and operation of 30 care farms, and each participant could use the services offered for no longer than 6 months. In the last project, care services were intended for disabled persons. That concept included the creation of open Integration Points, training dwellings and supported dwellings.

Table 1.

Projects implemented by care farms in Poland.

The assumptions for the functioning of Open Integration Points included the regulations for participant recruitment, which was the responsibility of an institution, the District Center for Family Assistance. Care was offered 8 h a day, plus 4 h on Saturday once a month. If transport was required, it was the responsibility of the caretaker or the care farm’s owner. The staff employed under the project included a manager (vested with general responsibility for the functioning of the OIP), a caretaker/trainer and dedicated specialists (hired upon consulting a specialist in charge of empowering disabled people). In turn, training dwellings were supposed to be a form of self-empowerment for adult participants on a 24/7 basis. The planned duration of staying in the apartment was up to 6 months, but could be extended for an indefinite period. The idea behind this solution was to teach the participants how to become self-reliant (managing their financial resources on their own; participating in classes and workshops) with a view to fully empowering people with impairments. Just like in the OIPs, a manager and a caretaker/trainer were employed. The last type of aid offered consisted in creating a supported dwelling. The target group for that solution were previous users of training dwellings. The training is supposed to involve the participants in a broad range of activities, including: economic training, running a household, self-service, educational trips and career guidance [63].

Based on the analysis of documents, reports or scientific papers on the functioning of care farms, e.g., [1,64,65,66,67,68,69], it can be concluded that Poland’s situation today is what was witnessed in the Netherlands in the 1990s. It means that the concept’s implementation in rural areas is only at a sluggish initiation stage, and it is so for a number of reasons. First, there still is no legal framework that would regulate the ability to set up that kind of facilities. Second, there is no clear and precise concept of how to finance or support the delivery of these services. Third, there is little social awareness of how care farms operate (the above is true both for potential service providers and for possible clients). Importantly, Poland also lacks a unified professional database to monitor the situation of existing care farms and of those who consider starting a care service business. The only tool available is the database created by the Kuyavian–Pomeranian Agricultural Consultancy Center in Minikowo as part of previously implemented projects. This is why there is no clear information on whether such facilities are being created in other Polish regions (and if so, what the underlying principles are). However, due to all of the above doubts and ambiguities, the term “care farm” should be defined in legal terms, including its financing principles [70,71].

Poland implemented a research project named GROWID, which was expected to result in proposing a care farm model [71]. It also addressed some matters related to the financing of such facilities. According to a report [72,73], it is important to specify whether such facilities should be subsidized with public funds or act as economic operators in the free market. Based on a study carried out by the GROWID consortium (Care Farms as a Driver of Rural Development faced with Demographic Challenge), it was concluded that Polish care farms should not be entirely financed with public funds. The authors clearly stated that such a solution would cause a number of difficulties and problems. First, it would become a kind of limitation for those who run the farms, since they would not be able to acquire customers in the market. Second, the farms’ potential for providing care services would not be fully tapped into. In rural areas in Poland, there is little demand for care services (although many families need them) because of their prices being high. According to what was proposed by the consortium, care farms will be able to operate with no direct support with public funds. Another important aspect of Polish realities is that in many regions it will be difficult, if not impossible, to establish a care farm. This is due to a number of reasons, including the fact that it is hard to tell whether a market exists for such services. It largely results from socioeconomic problems affecting certain Polish regions. Also, local administrative authorities have different ways of addressing the local community’s needs for care services. This is mostly due to differences between local government units in their economic and demographic situation, and to differences in social capital between Polish regions. According to numerous reports and scientific studies carried out in Poland [74,75,76,77], rural families lack the financial resources to purchase professional care services. This certainly is one of the reasons why the rural market for care services develops at an extremely slow pace, if at all. Hence, there is an important indication that in addition to being dealt with by institutions in a bottom-up approach, this topic should be primarily addressed by public authorities, including adequately prepared ministries. As an interesting solution, care farms could supplement the existing social assistance system in rural areas. Hence, the essential question is how to organize that market to enable the development of care farms while supporting or co-financing the visitors’ stay.

In the Netherlands, where agricultural holdings play a dominant role, financing is mostly covered by public funds allocated to health and care sectors. In turn, when it comes to Germany, Ireland or Slovenia, social farming is financed by public institutions with public resources allocated to healthcare or education [69].

Analyzing the European Commission’s Social Economy Action Plan, which was inaugurated on 9 December 2021 [78], it can be concluded that the legal forms of welfare farm production in Poland are only somewhat related to the European Commission’s Social Economy Action Plan. This is manifested first and foremost by exposing the need for a uniform legal framework allowing associations to reap the full benefits of the single market. This also applies to care farms set up and run as associations. At the moment, however, there is a lack of intensified cooperation on the formulation of uniform legislation to support the expansion and significance of the social economy and the international situation of the institution of care farms set up and run as associations. For this reason, we should call for legislative work to be undertaken in this area, which would guarantee further development and interest in this form of care farming.

In Poland, care farms that provide care services may apply for public funds under “Aktywni+” (Active+), a national program for 2021–2025 with an annual budget of ca. PLN 40 million [79,80]. Its key goal is to increase the participation of older adults in all aspects of social life. In Poland, the priority of the policy is to provide seniors with multifaceted support. As part of “Aktywni+”, NGOs and other authorized operators supporting older adults will be eligible for the financing of their projects. Funds will be granted to four priority areas. The first is related to social activity and includes measures taken to: increase the participation of older adults in active forms of leisure; support dependent seniors and their environment in their place of residence; promote volunteering among older adults in the local environment; and increase the presence of older adults in the labor market [81]. Next comes social participation, which is largely supposed to contribute to reinforcing the self-organization power of the senior community, and to increasing the influence of older adults on decisions regarding the citizens’ living conditions. The priorities also include what is referred to as digital inclusion. Its main objective is to implement instruments and measures expected to improve modern technology skills and to promote the wide adoption and implementation of technological solutions that the support social inclusion and safe living of older adults, including in care farms. The last priority consists in preparing people for old age and fostering a positive image of older adults and increasing their safety by strengthening sustainable intergenerational relationships. Care farms may apply for financial resources and take adequate measures with respect to all of the priorities listed above. Funds are also available under projects financed with European Union resources. Farmers who either run or are interested in setting up a care activity may use the financial resources offered, without limitation, under the Strategic Plan of the 2023–2027 Common Agricultural Policy. In Poland, the provisions of the LEADER/Community-Led Local Development (CLLD) intervention stated that Union’s funds shall be allocated to projects designed to build local identity based on social empowerment with the use of local resources, in a way to ensure that the needs of rural communities are met as far as possible, including through the use of knowledge, innovation and digital solutions. The intervention consists in that local action groups (LAGs) implement selected community-led local development strategies (LDSs) in rural areas. The goals of the intervention will be attained through the implementation of a broad range of operations in the following support areas:

- 1.

- Enterprise development, including bio-economy or green economy development through natural persons engaging in non-agricultural economic activity and the development of non-agricultural economic activity.

- 2.

- The development of non-agricultural functions for small farms with a view to setting up or developing agri-tourism farms, educational farms and care farms.

- 3.

- The development of collaboration by creating or developing short food supply chains.

- 4.

- Improved service access for local communities.

- 5.

- Preparing the smart village concept.

- 6.

- Improved access to small public infrastructure.

- 7.

- Driving social awareness of the importance of sustainable agriculture, agri-food economics, green economy and bio-economy; supporting the development of knowledge and skills in the area of innovativeness, digitization and enterprise; and reinforcing education programs for leaders of public and social life, except for infrastructural investments.

- 8.

- The social inclusion of seniors, young people and vulnerable persons.

- 9.

- Protecting the cultural or natural heritage of Polish rural areas [79,80].

Therefore, it seems that care farms have sufficient opportunities for seeking Union funds. However, the absence of a separate normative act governing the issues related to the functioning itself of care farms gives rise to practical difficulties. This is what makes it so important to put in place an appropriate model for the functioning of care farms.

5. Legal Forms of Running a Care Farm: The Situation in Poland

As mentioned above, the Polish law system lacks provisions that would govern the forms and models of running a care farm. This is probably because care farms, as an institution, have been active in Poland for only a couple of years [81]. Nevertheless, they have recently embarked on a clear growth path in rural areas [82]. Due to a lack of source materials and legal regulations related directly to that topic, it seems necessary to focus on the legal forms of running a care farm.

Currently, care farms are run as foundations, associations, cooperatives or self-employment businesses [83]. Usually, natural persons (individual farmers) decide to set up a care farm in the form of self-employment or association. This is partly due to the fact that running a care farm is a component of an agricultural activity [40]. However, in some cases, care farms are viewed as an alternative to the existing agricultural business [66]. This is because care farming supports the concept of social and care agriculture, in broad terms, and—as such—is considered to be a specific kind of social farming [84]. This is reflected in assistance provided to those is need, i.e., people who, for various reasons, find themselves in a difficult life situation, whether on a temporary or permanent basis [64]. In other words, the purpose of care farms is to support people who need it because of their age or health condition [85]. Bearing the above in mind, this paper intends to present the key aspects involved in setting up an individual business activity or an association as the prevalent forms of running a care farm in rural Poland.

In the Polish legal system, economic activity is governed by the provisions of the Entrepreneurs Act of 6 March 2018 [86]. Pursuant to Article 3 thereof, economic activity means an organized, continuous gainful activity performed on one’s own behalf. Thus, in order for an entrepreneurial activity to be considered an economic activity, it must meet the following cumulative conditions: be organized, gainful, performed on one’s own behalf and continuous [87]. Failure to meet any of those criteria means it cannot be qualified as an economic activity [88]. Therefore, the authors of this paper found it relevant to analyze these conditions.

An economic activity is organized if it makes a full use of its assets (e.g., movable or immovable property) and non-financial values (e.g., reputation, business secret), and forms a single, complex structure (from a functional and economic perspective) that participates in trading operations [89]. For an economic activity, being organized also means having a principal place of business (indicating the town where it is based).

In turn, the gainful aspect of an economic activity is manifested in it being profit-oriented. Also, in order for a gainful activity to be considered an economic activity, it must address the needs of other people, whether of a tangible or intangible nature. Obviously, it is not always feasible to derive profits from an activity, and therefore sustaining a loss does not contradict the profit-seeking goal of a business. As the literatures rightly indicate, as long as the operators seeks profit from an activity (even if in the longer run), they are running an economic activity [89].

Also, in order for an activity to be classified as an economic activity, it must be performed on one’s own behalf (on one’s own account) [90]. In other words, an operator who organizes such an activity must do so on his/her own behalf, and therefore shall bear unlimited responsibility for his/her liabilities. In turn, the continuous nature of an economic activity means it is repeatable and regular and, as such, forms an inseparable whole [91].

The analysis of the above criteria provides grounds for confirming the thesis advanced earlier in this paper, namely that care farms, too, can be run as an individual economic activity (self-employment). Just like any other economic activity in Poland, it is organized and continuous, it seeks profit, and—most importantly—it is conducted on the owner’s own behalf. Therefore, the question arises about the formal requirements that need to be met in order to start an individual economic activity and, as a consequence, set up a care farm.

Under Polish law, an individual economic activity may be set up by both adults and minors. The latter are required to obtain approval from their statutory representatives (parents) to establish an economic activity and, additionally, to perform the activities related thereto. An individual economic activity may also be set up by nationals of European Union member states, European Economic Area countries, the United States and the Swiss Confederation. In turn, nationals of non-members of the European Union member and the European Economic Area who want to set up an individual economic activity in Poland may do so provided that they hold the right of residence.

Natural persons vested with legal capacity may register an individual economic activity through the Central Register of and Information on Economic Activity [92].

In turn, an association [93] as a legal form of setting up and then running a care farm attracts equally high interest from those previously engaged in running an agri-tourism business or an agricultural holding. The right to organize in associations is governed by the Associations Act of 7 April 1989. Pursuant to its provisions, the right to establish associations is granted to Polish nationals who enjoy full legal capacity and are not deprived of public rights.

Under the Polish law, persons (no less than seven) who intend to establish an association shall adopt its statute and elect its founding committee or authorities [94]. Importantly, the statute shall specify, without limitation, the name of the association; its activity area and principal place of business; the way membership is granted and revoked; the reasons for revoking membership; the rights and obligations of members; its authorities and their competences; the procedure for electing the authorities; the procedure for extending the composition of the authorities; the ability for the members of the management board to obtain remuneration for activities involved in the performance of their functions; the association representation procedure, especially including the method for contracting financial obligations; financing streams; the procedure for charging membership fees; the principles for amending the statute; and the procedure for dissolving the association [95]. It is worth noting that associations are required to appoint a management board and an internal inspection authority.

Also, any economic activity or association whose purpose is to provide assistance to third parties—as it is the case for care farms—must comply with the requirements defined for social assistance entities. This is because care farms ran as an individual economic activity or association may take the form of a daycare facility, a family care center or round-the-clock nursing services.

Daycare centers are supposed to help those who, due to their age, illness or impairments, require to be partly taken care of and must be assisted in meeting their vital needs. Such persons may be entitled to obtain specialized or other care services or meals delivered in an assistance center. The purpose of daycare centers is to introduce local forms of support which enable maintaining the clients in their natural environment. As their name suggests, daycare centers offer a full-day stay as well as basic care, recreation, cultural and educational services plus meals [96].

In turn, a family care center is a form of care and accommodation services provided around the clock for no less than three and no more than eight people living together. Family care centers provide round-the-clock services for people who need them because of their age or disability. They offer accommodation, catering and facilities that allow their visitors to stay clean. Care services include assisting the guests in meeting their vital needs, nursing them and facilitating their contacts with the environment [96,97].

Conversely, round-the-clock care offered by specialized facilities to disabled, chronically ill or old-age people means providing care services on a 24 h/24 basis which ensure: assisting the guests in meeting their vital needs; hygienic care; essential assistance in dealing with personal matters; offering a place to stay and accommodation; and making sure their guests stay clean. The way the services are provided should take account of the guests’ health condition, physical and intellectual fitness, and individual needs and capabilities, as well as human rights, especially including the right to dignity, freedom, intimacy and sense of security. The basic responsibility of round-the-clock care facilities is to meet the requirements for rooms. Facilities which offer round-the-clock care services to disabled, chronically ill or old-age people may only host adults. Importantly, a single building of a facility may not host more than 100 persons provided with round-the-clock care services [96].

What also needs to be emphasized is that a discussion is ongoing in Poland on which ministries should be considered competent for matters related to the structure and financing of care farms. In practice, this gives rise to doubts as to determining the nature of care farms. Obviously, from the point of view of legal regulations, they may take several forms, including an economic activity or association. However, the question remains whether they meet the criteria of an institution active in the area of health, agriculture or economy, in broad terms. The lack of precision regarding these matters and the absence of a separate normative act governing care-farm-related topics results in a number of difficulties (including how to determine the financing streams). In the long run, it may contribute to people losing interest in that form of implementing the assumptions behind social and care farming.

6. Management and Policy Implications

Analyzing individual legal acts as well as strategic documents in this area such as, for example, reports from the GROWID project [Care farms in rural development in the face of demographic challenges], which was carried out by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Kołłątaj University of Agriculture in Kraków in the years 2019–2021, it can be concluded that the assumptions developed by this consortium have not been implemented in Polish conditions in a manner adequate to market demand. This is mainly due to the problems associated with the fact that the individual ministries should cooperate and jointly work out and specify how a care farm in Poland should function, on what terms and conditions and what system of financing or co-financing care should be adopted. This is a very important aspect from the point of view of both the owners of care farms as providers of such services and the residents themselves who want to use such services. Therefore, it would be necessary to develop an appropriate definition of a care home in Poland and include it in the relevant legal acts that will regulate the above issues. The second issue relates to the aspect of possible charges. This mainly concerns the process of recruiting people to a particular holding and the whole procedure related to care. At the moment in Poland there is no developed scheme in this respect, which we think should be done and implemented. In this way, both the demand and the supply side will comprehensively have an appropriate body of knowledge and tools that can be used.

7. Discussion

Having in mind the above considerations on the forms of running a care farm, focus needs to be placed on three aspects of utmost importance from the practical perspective.

First of all, the Polish legal system lacks regulations for care farming in broad terms and for care farms in general. Indeed, the are no provisions which would implicitly define what a care farm is and what its internal and external structure should look like. This, in turn, gives rise to serious problems in terms of determining what a care farm should be and what scope of activities it should perform. The lack of precision also makes it more difficult to specify the right profile (service portfolio) of the activity run by care farms. It seems that regulations need to be implemented to clearly indicate that each adult shall have the right to set up (and subsequently run) a care farm with a view to providing care and accommodation services. In turn, dedicated regulations should detail the scope of services offered and the way they are delivered to interested parties.

Second, as mentioned earlier, there are no adequate instruments for supporting the financial aspects related to running a care farm. Due to persisting problems in defining the scope of relevant competences of each ministry, none of them has taken care farms into account in any of their policies. Unfortunately, the above creates some kind of chaos which contributes to public disinformation, including those potentially interested in that form of social and care farming. As care farms are part of social and care farming, it seems that they should be covered by the policy of the Ministry of Agriculture in agreement with the policy run by the Ministry of Health (due to the kind of services they provide).

Finally, because of the legal regime related to running an economic activity in Poland, care farms are much more frequently established, and then ran, as associations. It seems that this operational form of care farms is beneficial not only from the perspective of legal regulations (being less stringent) but also for economic reasons (taxes paid). Similar opinions are expressed in countries such as the Netherlands or Sweden (the latter being home to “Hushållningssällskapet”, an association of care farms with ca. 100 members active in the area of social care, education, health and leisure). Associated farms base their activity on working with animals and gardening; their key goal is to help their visitors improve the quality of their lives and succeed with personal development [50]. In turn, the Dutch Federation of Care Farms is an association of care service providers essentially focused on rural areas, underpinned by a strong and professional organization which matches demand with supply at regional level [56]. Also, some measures were taken under the ERASMUS+ program (e.g., SoEngage and SoEngage Plus [97]). Financed by the Erasmus+ KA2 Strategic Partnership for Education and Vocational Training, they confirm the importance of comprehensive, well-organized collaboration between farms. Another important step consists of indicating the path for setting up and running a care farm and outlining the target audience for its services.

8. Conclusions

The study carried out by the authors revealed that the key aspect is the need for Poland to establish regulations for care farming in broad terms and for how care farms are set up and function. Another important matter is related to making an appropriate and rational use of financial resources disbursed under aid programs for farms potentially interested in offering these kinds of services. Hence, there is need for seeking and building a comprehensive support system for care-related projects in Poland. Only a professional end-to-end legal and financial policy will enable the functioning of an increasingly larger number of care farms. Also, developing and putting in place the right solutions will allow for the building of social awareness of this topic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.W.-Z. and A.W.-J.; methodology, M.M.W.-Z. and A.W.-J.; software, M.M.W.-Z.; validation, M.M.W.-Z. and A.W.-J.; formal analysis, M.M.W.-Z. and A.W.-J.; investigation, M.M.W.-Z. and A.W.-J.; resources M.M.W.-Z.; data curation, A.W.-J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.W.-Z. and A.W.-J.; writing—review and editing, M.M.W.-Z. and A.W.-J.; visualization, M.M.W.-Z.; supervision, A.W.-J.; project administration, A.W.-J.; funding acquisition, M.M.W.-Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

PLN: Polish zloty; GROWID: Care Farms as a Driver of Rural Development faced with Demographic Challenges.

References

- Hassink, J.; Agricola, H.; Veen, E.J.; Pijpker, R.; de Bruin, S.R.; Meulen, H.A.B.v.d.; Plug, L.B. The Care Farming Sector in The Netherlands: A Reflection on Its Developments and Promising Innovations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, M.; Daab, M.; Miśkowiec, A.; Rogalska, E.; Sochacka, M. Rozwój Rolnictwa Społecznego w Europie na Przykładzie Gospodarstw Opiekuńczych w Wybranych Krajach Europejskich (Development of Social Farming in Europe: A Case Study of Care Farms in Selected European Countries); PCG Polska Sp. z o. o Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mendell, M. The Three Pillars of the Social Economy: The Quebec Experience. In The Social Economy. International Perspective on Economic Solidarity; Amin, A., Ed.; Zed Books Publishing House: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tulla, A.F.; Ana, V.; Badia, A.; Guirado, C.; Valldeperas, N. Rural and regional development policies in Europe: Social farming in the common strategic framework (Horizon 2020). J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2014, 6, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessein, J.; Bock, B.B.; De Krom, M. Investigating the limits of multifunctional agriculture as the dominant frame for Green Care in agriculture in Flanders and the Netherlands. J. Rural. Stud. 2013, 32, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, J.; Grin, J.; Hulsink, W. Enriching the multi-level perspective by better understanding agency and challenges associated with interactions across system boundaries. The case of care farming in the Netherlands: Multifunctional agriculture meets health care. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 57, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeds, P. Farm education and the value of learning in an authentic learning environment. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2015, 10, 381–404. [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen, P.P.; Zock, J.-P.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Helbich, M.; Hoek, G.; Ruijsbroek, A.; Strak, M.; Verheij, R.; Volker, B.; Waverijn, G. Neighbourhood social and physical environment and general practitioner assessed morbidity. Health Place 2018, 49, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, J.; Wickramasekera, N.; Elings, M.; Bragg, R.; Brennan, C.; Richardson, Z.; Wright, J.; Llorente, M.G.; Cade, J.; Shickle, D. The impact of care farms on quality of life, depression and anxiety among different population groups: A systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2019, 15, e1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, R.; Jo, P.; Jules, P. Care Farming in the UK: Contexts, Benefits and Links with Therapeutic Communities. Ther. Communities 2008, 29, 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. European Economy Institutional Papers, Report: The 2021 Ageing Report Economic and Budgetary Projections for the EU Member States (2019–2070). The 2021 Ageing Report. Economic and Budgetary Projections for the EU Member States (2019–2070); European Commission: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- EUROSTAT. Raport Ageing Europe—Statistics on Population Developments—Statistics Explained; EUROSTAT: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiński, R. Wpływ otoczenia międzynarodowego na funkcjonowanie przedsiębiorstw w Polsce (Influence of the international environment on the functioning of companies in Poland). In Rozwój Zrównoważony. Założenia Koncepcyjne, Działania Systemowe i Implementacja Idei na Poziomie Przedsiębiorstwa (Sustainable Development. Conceptual Assumptions, Systemic Measures and Implementation of the Idea at Company Level); Baszyński, A., Kamiński, R., Eds.; Polskie Towarzystwo Ekonomiczne w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad strokes towards a grand theory in the analysis of sustainable development: A return to the classical political economy. New Political Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, T. The Concept of Sustainable Development: From its Beginning to the Contemporary Issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONZ w Polsce. Available online: https://www.un.org.pl/ (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Poczta, W. Przemiany w rolnictwie polskim w okresie transformacji ustrojowej i akcesji Polski do UE (Changes in Polish agriculture during the economic transformation and Poland’s accession to the EU). Wieś Rol. (Agric. Rural. Areas) 2020, 2, 187. [Google Scholar]

- Adamowicz, M. Przesłanki rozwoju wielofunkcyjności rolnictwa i zmian we współczesnej polityce rolnej (Conditions for multipurpose agricultural development and changes to today’s agricultural policy). Zagadnienia Ekon. Rolnej (Issues Agric. Econ.) 2005, 1, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Adamowicz, M.; Zwolińska-Ligaj, M. Koncepcja wielofunkcyjności jako element zrównoważonego rozwoju obszarów wiejskich (The concept of multifunctionality as part of sustainable rural development). Zesz. Nauk. SGGW Eur. Politics Financ. Mark. 2009, 2, 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżewski, B.; Matuszczak, A.; Czyżewski, A.; Brelik, A. Public goods in rural areas as endogenous drivers of income: Developing a framework for country landscape valuation. Land Use Policy 2020, 107, 104646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, S. Poziom Życia Ludności Wiejskiej o Niepewnych Dochodach (Living Standards of the Rural Population with Insecure Incomes); Publishing House PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżewska, M.; Pach, J.; Sala, K. Ekonomia Społeczna i Przedsiębiorczość. Innowacje—Środowisko (Social Economy and Entrepreneurship. Innovation—Environment); CeDeWu Publishing House: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lanfranchi, M.; Giannetto, C.; Abbate, T.; Dimitrova, V. Agriculture and the social farm: Expression of the multifunctional model of agriculture as a solution to the economic crisis in rural areas. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 21, 711–718. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiński, R. Polish experience of social farming in Bory Tucholskie area. Rural. Areas Dev. 2017, 14, 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, C.; Mahoney, E. Why Is Diversification an Attractive Farm Adjustment Strategy? Insights from Texas Farmers and Ranchers. J. Rural. Stud. 2009, 25, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, J. Gospodarstwa Opiekuńcze—Nowe Wyzwania dla Obszarów Wiejskich (Care Farms: New Rural Challenges); Publishing House of the Brwinów Agricultural Consultancy Center, Branch Office in Krakow: Krakow, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wojcieszak, A.; Wojcieszak, M. Uwarunkowania funkcjonowania gospodarstw opiekuńczych na terenach wiejskich (Conditions for the functioning of care farms in rural areas). Zagadnienia Doradz. Rol. (Agric. Consult. Issues) 2018, 3/2018, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Subocz, E. Rolnictwo społeczne jako nowa funkcja obszarów wiejskich z perspektywy europejskiej i polskiej (Social farming as a new function of rural areas from a European and Polish perspective). Obsz. Wiej. (Rural. Stud.) 2019, 54, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Jarábková, J.; Chrenekova, M.; Varecha, L. Social Farming: A Systematic Literature Review of the Definition and Context. Eur. Countrys. 2022, 14, 540–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, B.; Hamers, J.P.; Zwakhalen, S.M.; Tan, F.E. Verbeek. Quality of care and quality of life of people with dementia living at green care farms: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassink, J.; Hulsink, W.; Grin, J. Farming with care: The evolution of care farming in the Netherlands. NJAS—Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2014, 68, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, F.; Biró Szabolcs, F. Knowledge sharing and innovation in agriculture and rural areas. Rural. Areas Dev. 2017, 14, 325–336. [Google Scholar]

- Bakalarczyk, R. Podmioty ekonomii społecznej w kształtowaniu polityki społecznej—różne role i obszary oddziaływania (The importance of social economy entities in shaping the social policy: Different roles and impact areas). Polityka Społeczna (Soc. Policy) 2022, 574, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, J. Social Farming Across Europe: An Overview. In Supporting Policies for Social Farming in Europe. Progressing Multifunctionality in Responsive Rural Areas; Di Iacovo, F., Connor, D.O., Eds.; ARSIA: Firenze, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Official Journal of the European Union of February 15, 2013, Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on Social Farming: Green Care and Social and Health Policies. 2013/ C 44/07. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52012IE1236 (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Di Iavoco, F.; O’Connor, D. Supporting Policies for Social Farming in Europe: Progressing Multifunctionality in Responsive Rural Areas; Arsia: Firenze, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, M.; Wojcieszak, M. Znaczenie social farmingu w wybranych krajach Unii Europejskiej jako przykład przedsiębiorczości w turystyce na obszarach wiejskich (Importance of social farming in selected European Union countries as an example of entrepreneurship in rural tourism). Sci. Pap. Wrocław Univ. Econ. 2018, 535, 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Subocz, E. Gospodarstwa opiekuńcze jako innowacyjna forma wsparcia i integracji społecznej osób o szczególnych potrzebach (Care farms as an innovative form of support for and social integration of people with special needs). Pr. Soc. (Soc. Work.) 2022, 1, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Krzysztofik-Pełka, M. Z prawnej problematyki świadczenia usług opiekuńczych w gospodarstwach rolnych w zakresie zagadnień prawnych świadczenia usług opiekuńczych w gospodarstwach rolnych (Some legal issues involved in providing care services on care farms: Legal aspects of providing care services on care farms). Przegląd Prawa Rolnego (Agric. Law Rev.) 2022, 1, 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zajda, K. Wdrażanie innowacji społecznych przez wiejskie organizacje pozarządowe (Implementation of social innovations by rural NGOs). Wieś Rol. (Rural. Areas Agric.) 2017, 4, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewska, B. Gospodarstwa opiekuńcze jako forma pozyskiwania dochodów przez małe gospodarstwa rolne w Polsce (Care farms as a way of accessing revenue streams by small farms in Poland). Problemy Drobnych Gospodarstw Rolnych (Small Farm Probl.) 2018, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella, J.; O’Connor, D.; Smyth, B.; Nelson, R.; Henry, P.; Walsh, A.; Doherty, H. Social Farming Handbook, The School of Agriculture and Food Science; University College Dublin: Dublin, Ireland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jervell, M.A. Changing Patterns of Family Farming and Pluriactivity. Sociol. Rural. 1999, 39, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowska-Wabik, J. Potencjał spółdzielni w zaspokajaniu niektórych potrzeb państwa i społeczeństwa—Wprowadzenie do dyskusji (The potential of cooperatives in meeting certain needs of the state and the society: An introduction to the discussion). Ekon. Społeczna (Soc. Econ.) 2012, 2, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Knapik, W.; Bartoszek, A. Potencjał gospodarstw rolnych w zakresie poszerzania działalności o usługi opiekuńcze dla osób starszych (The farms’ potential to extend their activity with care services for the elderly). In Knapik: Innowacje Społeczne na Obszarach Wiejskich: Ujęcie Interdyscyplinarne (Social Innovations in Rural Areas: An Interdisciplinary Approach); Szczepańska, B., Burdyk, K., Eds.; Publishing House of the University of Agriculture in Krakow: Krakow, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Śpiewak, R. Mniej (Less). In Polska Wieś 2044. Wizja Rozwoju (Polish Rural Areas 2044: A Vision of Development); Halamska, M., Kłodziński, M., Stanny, M., Eds.; Institute of Rural and Agriculture Development of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Korycki, A. Aktywizacja Społeczna i Przeciwdziałanie Wykluczeniu Społecznemu Seniorów z Niepełnosprawnościami (Social Empowerment and Counteracting the Social Exclusion of Disabled Seniors); Difin Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Program for Social Economy Development. Ministry of Labor and Social Policy, Official Journal of September 24, 2024, Item 811. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/family/social-economy--development-directions#:~:text=During%20this%20period,%20departmental. (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 2nd April, 1997. Dz. Ustaw 1997, 483.

- Leś, E. Nowa ekonomia społeczna. Wybrane koncepcje (Selected concepts of new social economy). Trzeci Sekt. (Third Sect.) 2005, 2, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Team of the Social Integration Observatory: Social Economy Institutions in the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship; Regional Social and Health Policy Center: Kielce, Poland, 2010.

- Defoury, J.; Develtere, P. Ekonomia społeczna: Ogólnoświatowy trzeci sektor (Social economy: A worldwide tertiary sector). In Antologia Kluczowych Tekstów. Przedsiębiorstwo Społeczne (Anthology of Key Papers. A Social Enteprise); Foundation of Socio-Economic Initiatives: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maziarz, W. Ekonomia społeczna w Polsce (Social economy in Poland). Eur. Reg. 2016, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiński, R. Gospodarstwo opiekuńcze jako alternatywna ścieżka rozwoju gospodarstw agroturystycznych (Care farm as an alternative development path for agri-tourism farms). Stud. Kom. Przestrz. Zagospod. Kraj. PAN (Stud. Comm. Natl. Land Dev. Pol. Acad. Sci.) 2015, 162, 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Woś, A.; Zegar, J. Rolnictwo Społecznie Zrównoważone (A Socially Sustainable Agriculture); Publishing House of the Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics: Warsaw, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Central Statistical Office. Liczba Wsi w 2022 Roku (Number of Villages in 2022). Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/powierzchnia-i-ludnosc-w-przekroju-terytorialnym-w-2024-roku,7,21.html (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Stępnik, K. Przegląd badań nad rozwojem gospodarstw opiekuńczych realizowanych przez Centrum Doradztwa Rolniczego w Brwinowie Oddział w Krakowie (A review of studies on the development of care farms carried out by the Krakow Branch Office of the Brwinów Agricultural Consultancy Center). In Innowacje Społeczne na Obszarach Wiejskich: Ujęcie Interdyscyplinarne (Social Innovations in Rural Areas: An Interdisciplinary Approach); Krakow, W., Knapik, W., Szczepańska, B., Burdyk, K., Eds.; Publishing House of the University of Agriculture in Krakow: Krakow, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Halamska, M.; Kłodziński, M.; Stanny, M. Polska Wieś 2044. Wizja Rozwoju (Polish Rural Areas 2044: A Vision of Development); Institute of Rural and Agriculture Development of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Poczta, W. Rolnictwo w Rozwoju Polskiej wsi 2044 (Agriculture in Polish Rural Development by 2044). In Polska Wieś 2044. Wizja Rozwoju (Polish Rural Areas 2044: A Vision of Development); Halamska, M., Kłodziński, M., Stanny, M., Eds.; Institute of Rural and Agriculture Development of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewska, B. Gospodarstwa opiekuńcze odpowiedzią na potrzebę społeczną (Care farms as a response to a social need). Nierówności Społeczne Wzrost Gospod. (Soc. Disparities Vs. Econ. Growth) 2018, 54, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Central Statistical Office. Population . Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/sytuacja-demograficzna-polski-do-roku-2022,40,3.html (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Stanny, M.; Rosner, A.; Komorowski, Ł. Monitoring Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich. Etap III. Struktury Społeczno-Gospodarcze, ich Przestrzenne Zróżnicowanie i Dynamika (Monitoring the Rural Development. Stage 3. Socioeconomic Structures, Territorial Differences between Them and the Pace of Changes in Them); European Fund for the Development of Polish Villages, Institute of Rural and Agriculture Development of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- KPODR: Gospodarstwa Opiekuńcze—W Każdym Wieku Można być Szczęśliwym (Care Farms: Happiness at Any Age). Available online: https://opieka.kpodr.pl/pl/front/ (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- MODR. Available online: https://gov.modr.pl/sites/default/files/brochures/p.zwonek_prowadzenie_gospodarstw_opiekunczych.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Michalska, S.; Rosa, A.; Kamiński, R. Innowacyjne formy opieki nad osobami starszymi na obszarach wiejskich w Polsce (Innovative forms of care for the elderly in Polish rural areas). Wieś Rolnictwo (Rural. Areas Agric.) 2019, 3, 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Herudzińska, M. Seniorzy w Polsce—Stan zdrowia, wsparcie instytucjonalne i opieka nieformalna (Polish seniors: Health condition, institutional support and informal care). Wychowanie w Rodzinie (Fam. Upbringing) 2022, XXVII, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Konieczna-Woźniak, R. Miejsca i przestrzenie sprzyjające inkluzji i partycypacji społecznej w starości. Propozycja gospodarstw opiekuńczych. (Places and spaces which favor social inclusion and participation at an old age. The offering of care farms). Dziennik: Edukacja Dorosłych (Adult Educ. J.) 2020, 82/2020, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Policy. Polityka Społeczna Wobec Osób Starszych 2030. Bezpieczeństwo—Uczestnictwo—Solidarność Raport 2018 (Social Policy for the Elderly 2030. Security, Participation, Solidarity; A 2018 Report); Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Policy: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, A.; Zarębski, P. Finansowanie działalności innowacyjnej i jej znaczenie dla rozwoju obszarów wiejskich (The financing of innovative activities and their importance for rural development). Wieś i Rolnictwo (Agric. Rural. Areas) 2018, 2, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maye, D.; Ilbery, B.; Watts, D. Farm diversification, tenancy and CAP reform: Results from a survey of tenant farmers in England. J. Rural. Stud. 2009, 25, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raport—Przygotowanie Gospodarstw Rolnych do Pełnienia Funkcji Społecznych Lub Opiekuńczych w Kontekście Dostępności Architektonicznej i Koncepcji Projektowania Uniwersalnego Lub Racjonalnego Usprawnienia (A Report on the Preparation of Farms for Delivering Social or Care Services in the Context of Architectural Accessibility and in the Light of the Concepts of Polyvalent Design or Rational Improvement); Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development Publish House: Warsaw, Poland, 2023.

- Król, J.; Stępnik, K.; Knapik, W.; Nowak, P.; Wnęk, M. Raport GROWID: Identyfikacja i Analiza Dotychczas Podejmowanych Inicjatyw w Zakresie Łączenia Działalności Rolniczej i Opiekuńczej w Polsce (The GROWID Report: Identifying and Analyzing Previous Initiatives Taken to Combine Agricultural and Care Activities in Poland); Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development Publishing House: Krakow, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Policy. Informacja o Sytuacji Osób Starszych w Polsce za Rok 2022 (Information on the Situation of Elderly People in Poland in 2022); Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Policy: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Family. Raport: Sprawozdanie z Realizacji Programu wieloletniego na Rzecz Osób Starszych “Aktywni+” na Lata 2021–2025—Edycja 2022 (Report on the implementation of the Multiannual Programme for Older Persons, “Active+” for 2021–2025—Edition 2022); Report 2023; Ministry of Family Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M.; Roman, M.; Nadolny, T. Funkcjonowanie Gospodarstw Opiekuńczych w Polsce na Przykładzie Wybranego Studium Przypadku (The functioning of care farms in Poland as illustrated by a selected case study). Ann. PAAAE 2022, XXIV, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegar, J.S. Co i jak określa wizję wsi 2044 (What determines the 2044 vision of rural areas and how it is determined). In Polska Wieś 2044. Wizja Rozwoju (Polish Rural Areas 2044: A Vision of Development); Halamska, M., Kłodziński, M., Stanny, M., Eds.; Institute of Rural and Agriculture Development of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Szarfenberg, R. Poverty Watch. In Monitoring Ubóstwa Finansowego i Polityki Społecznej Przeciw Ubóstwu w Polsce w 2020 r; Polski Komitet EAPN Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Plan Działań Komisji Europejskiej na Rzecz Ekonomii Społecznej. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0288_PL.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Policy. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/rodzina/seniorzy (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/rolnictwo/-leaderrozwoj-lokalny-kierowany-przez-spolecznosc-rlks (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Herudzińska, M.H. Nieformalni opiekunowie osób starszych—Doświadczenia i uczucia oraz ich potrzeby związane z pełnioną rolą (Informal Caregivers of older people—Experiences and feelings and their needs related to their role). Rocz. Lubus. 2020, 46, 281–293. [Google Scholar]

- Czapiewska, G. Zmienność funkcji w przestrzeni wiejskiej (Variability of economic functions in rural areas). Rozw. Reg. Polityka Reg. (Reg. Dev. Reg. Policy) 2021, 55, 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Czapiewska, G. Gospodarstwa opiekuńcze jako perspektywiczny kierunek rozwoju usług społecznych w środowisku wiejskim (Care farms as a promising development path for social services in a rural environment). Rozw. Reg. Polityka Reg. (Reg. Dev. Reg. Policy) 2023, 67, 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczuk-Misek, A. Gospodarstwo Opiekuńcze—Jak Zacząć (Care Farms: How to Start); Lower Silesian Agricultural Consultancy Center: Wrocław, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Miniszewski, M.; Kutwa, K. Dwie Dekady Rozwoju Polskiego Rolnictwa. Innowacyjność Sektora Rolnego w XXI Wieku; Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jeżyńska, B. Współczesne Funkcje Gospodarstw Rodzinnych. Zagadnienia Prawne. Ekspertyza (Modern Functions of Family Farms. Legal Aspects: An Expert Report); Office of Analysis and Documentation: Warsaw, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Entrepreneurs Law Act of March 6, 2018. Dz. Ustaw 2024, 236. Available online: https://eli.gov.pl/eli/DU/2018/646/ogl#:~:text=Tekst%20ujednolicony:%20D20180646Lj.pdf. (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Gwoździcka-Piotrowska, M. Pojęcie działalności gospodarczej w prawie polskim (Economic activity as defined in the Polish law). Przegląd Nauk. -Metodyczny. Eduk. Dla Bezpieczeństwa (Sci. Methodol. Rev. Educ. Greater Saf.) 2009, 1, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki, H.; Kucharski, K. Pojęcie działalności gospodarczej w Prawie Przedsiębiorców (Economic activity as defined in the Entrepreneurs Law). Biul. Stowarzyszenia Absolwentów I Przyj. Wydziału Prawa Katol. Uniw. Lub. (Newsl. Assoc. Grad. Friends Cathol. Univ. Lub.) 2021, XVI, 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Kruszewski, A. Prawo Przedsiębiorców. Komentarz (A Comment to the Entrepreneurs Law); C.H. Beck Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Komierzyńska-Orlińska, E. Konstytucja Biznesu. Komentarz. Prawo Przedsiębiorców. Ustawa o CEIDG (A comment to the Business Constitution. The Entrepreneurs Law. The Act on the Central Register of and Information on Economic Activity. The SME Ombudsman Act). In Act on the Principles for the Participation of Foreign Entrepreneurs and other Foreign Parties in Economic Activities on the Territory of the Republic of Poland; Wierzbowski, M., Ed.; Walters Kluwer Publish House: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; pp. 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Odachowski, J. Ciągłość działalności gospodarczej (Continuity of economic activity). Glosa 2003, 10, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Act on the Central Register of and Information on Economic Activity and on the Entrepreneurs’ Information Point of March 6, 2018. Dz. Ustaw 2022, 541. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20180000647/T/D20180647L.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Gulińska, E. Stowarzyszenie jako element społeczeństwa obywatelskiego (Association as a part of civic society). Stud. Prawa Publicznego (Public Law Stud.) 2023, 2, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romul, J. Pojęcie stowarzyszenia (Definition of association). Ruch Praw. Ekon. I Socjol. (Leg. Econ. Sociol. Mov.) 1965, 4, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hadrowicz, E. Prawo o Stowarzyszeniach (The Associations Law); C.H. Beck Publish House: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; pp. 138–191. [Google Scholar]

- SoEngage Plus PL: Social Farms. Available online: https://www.soengage.eu/pl/soengage-plus-pl/ (accessed on 31 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).