Abstract

A comprehensive lexicon is a necessary communication tool between the panel leader and panelists to describe each sensory stimulus potentially evoked by a product. In the current scientific breeding and trading scenario, a multilingual sensory lexicon is necessary to ensure the consistency of sensory evaluations when tests are conducted across countries and/or with international panelists. This study aimed to develop a reference multilingual lexicon for raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) and blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) to perform comparative sensory tests through panels operating in different countries using their native language. Attributes were collected from state-of-the-art literature and integrated with a detailed description of the sensory stimulus associated with each term. A panel of sensory judges was trained to test lexicon efficacy. After training, panelists evaluated three cultivars of blueberry and raspberry through RATA (Rate All That Apply), which allowed missing attributes to be excluded while rating those actually present. Results showed the discerning efficacy of the lexicon developed can be a valuable tool for planning sensory evaluations held in different countries, opening up further possibilities to enrich blueberry and raspberry descriptor lists with emerging terms from local experience and evaluations of berry genotypes with peculiar traits.

1. Introduction

Sensory analysis is aimed at capturing all product characteristics through a comprehensive evaluation of the product’s perceptible attributes and their relative intensities. When applied to foods, the core of this discipline is the knowledge of human perception of taste, odor, sound, mouthfeel and visual stimuli [1]. A basic requisite of sensory analysis is to define all the possible terms useful for describing all perceived stimuli and assess similarities and differences among products. Sensory analysis guidelines accurately define the figure of the sensory scientist (panel leader) [2] possessing the appropriate expertise in this field, knowledge about sensory methodologies, and communication skills necessary for efficaciously training the sensory judges. Panelists should be trained to exploit individual perception ability, and to properly communicate, with precise terms, characteristics and intensity of their sensations.

A shared lexicon is a necessary communication tool, between a panel leader and panelists, providing the correct terms for describing each sensory stimulus. The sensory lexicon is defined as a “standardized vocabulary” [3], and it is an essential prerequisite for conducting a descriptive sensory analysis. The current distribution of sensory lexica has been reviewed by [4], and indicated the importance of increasing the availability of this essential support for a sound sensory evaluation of products. A multilingual sensory lexicon is necessary to assure the consistency of evaluation when tests are conducted across countries and/or when the participants of a sensory test speak different languages. Studies have been reported for snacks with matching translations in English, Spanish, Chinese, and Hindi [5], for kimchi cabbage in English and Korean [6], and for Sichuan pepper in English and Chinese [7].

Lawless and Civille, 2013 assigned the lexicon development procedure to highly-trained panelists, describing their individual perceptions of products and confirming them in a consensus session. However, increasing availability of literature and the development of rapid methodologies such as CATA (Check-All-That-Apply) and RATA (Rate-All-That-Apply) [8] allow sensory specialists to choose terms and propose them to trained panelists only for validation and, eventually, integration of an attribute list. RATA, highlighting a selection of comprehensive perceivable sensations, fits the attributes list validation process perfectly and reduces judges’ fatigue as compared to descriptive analysis, which requires the explicit intensity assessment of all listed attributes [9,10]. This approach reduces the development time while maintaining high accuracy [10].

The novel study conducted here was implemented within the framework of the Horizon2020 project BreedingValue [11], which includes, among other activities, panel and consumer sensory evaluations of berries in different European countries in order to assess the consumer perception of a wide range of genetic resources, spanning from new pre-breeding material to established cultivars.

Since a strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) lexicon was already developed and a specific 16-term lexicon was available [12], our research focused on raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) and blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.), both still lacking an exhaustive lexicon. Indeed, despite the growing interest in the production, trade and consumption of blueberries and raspberries, the bibliographical research evidenced the relatively low number of papers providing information on blueberry and raspberry sensory evaluation. Such a limited bibliography was not a sufficient precondition to develop a complete lexicon to be translated into different languages. Thus, the aim of this research was to develop a standard multilingual lexicon for berries, to provide panel leaders and assessors in different countries with a standard tool for performing comparative sensory tests for evaluating the same attributes but using their native language. The activity was designed to (a) develop a comprehensive sensory lexicon; (b) translate the sensory terms and definitions from English into six other languages: Finnish, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Turkish; and (c) validate the lexicons´ adequacy and effectiveness by a trained panel. The lexicons’ validation was executed by a trained panel using RATA, allowing the use of a high number of descriptors, rating only those actually perceived, thus reducing so-called sensory fatigue [9,10].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Sensory Terms

The first step was collecting and selecting sensory attributes used in scientific literature, aiming to cover a high range of sensory stimuli provoked by blueberry and raspberry fruit. The literature research was carried out in Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar platforms by using the following keywords: Blueberry, Raspberry, Blueberry sensory evaluation, Raspberry sensory evaluation.

2.2. Expert Consultation and Translation of Lexicons

The first versions of the blueberry and raspberry lexicons were created in English, and further analyzed and commented by a multi-national panel of sensory experts, participating in the BreedingValue project. The sensory evaluation lists of terms were chosen through a comprehensive literature review and implemented with the contribution of sensory scientists’ previous work and experience. Once consensus about sensory attributes to be included alongside a relative description had been achieved, each partner translated it into their native language. The aim was to create a 7-language sensory lexicon including English, Italian, Finnish, French, German, Turkish and Spanish.

2.3. Sensory Evaluation Tests to Validate Lexicons

The sensory evaluation tests were performed at the IBE (Institute of Bioeconomy) sensory laboratory (Bologna, Italy), under controlled environmental conditions with individual, fully-equipped sensory booths. Fizz software (Version 2.51 c02; Biosystémes, Couternon, France) was used for data collection. Visual aspects (color, size, shape, peculiar features) of fruit were not submitted to panelists in the validation process, since they can be measured through laboratory technology (e.g., colorimetry, image analysis).

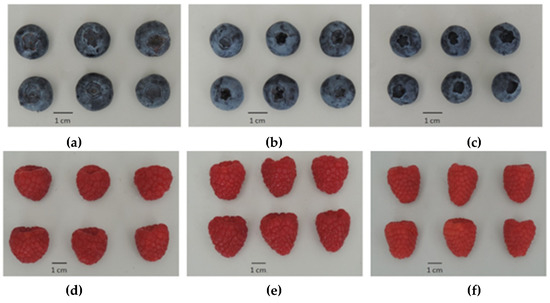

2.4. Samples

The blueberry cultivars AtlasBlue, Rebel and Ventura, and the raspberry cultivars Adelita, Dafne and Lagorai Plus, supplied by Sant’Orsola S.C.A. (Italy), were used for the lexicon validation tests (Figure 1.). Samples, at commercial ripeness, were collected from fields in Sicily and shipped in a refrigerated truck (4 °C ± 1 °C) to Sant’Orsola SCA headquarter (Cirè di Pergine Valsugana (TN), Italy), stored at 1.5 °C ± 0.5 °C for 2 days, and delivered to IBE laboratory for sensory test evaluations conducted at room temperature (22 °C ± 2 °C).

Figure 1.

Cultivars used for sensory evaluation. Blueberry: (a) cv. AtlasBlue, (b) cv. Rebel, (c) cv. Ventura. Raspberry: (d) cv. Adelita, (e) cv. Dafne, (f) cv. Lagorai Plus.

2.5. Panelists

Two trained panels (16 judges for blueberry and 14 for raspberry) were involved in the sensory testing. The chosen panelists had more than 1000 h of experience in general sensory tasting for various food and sensory techniques, including attribute identification. Moreover, they had completed 100 h training on fruit-related attributes.

2.6. RATA Analysis

The panel leader explained each sensory descriptor to the panelists to upskill them on the lexicon-sorting step. Lexicon sorting was performed through the RATA sensory test [10]. The RATA evaluation sessions lasted 45 min, and two replicas were performed for each berry species. Panelists received a sample set consisting of the three cultivars, three fruits per cultivar, coded by a three-digit code, for each berry species. The presentation order of the samples was randomized among panelists using a balanced Latin square design. The order of attributes was randomized by sensory modality (texture, taste and flavor). Panelists were asked to taste each sample and check the sensory features perceivable among the list. First, the term was checked and, if applicable, the intensity perceived was indicated through a 9-point scale from “low” to “high”. Instead of a 3- or 5-point scale, this was used to improve the discriminability of subtle differences [13]. After each sample, the panelists waited for 60 s to be prepared for the next evaluation and rinsed their mouths with mineral water. Judges selected and rated the attributes perceived in the tested samples, while discarding those not identified.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (IBM Corp. Released 2021. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). The RATA data were analyzed through two approaches: the first considered the frequency selection of terms (RATA frequencies), and the second considered the data as RATA intensities [13]. RATA frequencies were calculated by counting the number of citations for each attribute. A contingency table was built from the RATA data. According to relative frequency, the list of attributes was divided into tertiles. For each sample, only attributes belonging to the third (67–100% frequency) and second (34–66%) tertiles were used to create a Venn diagram showing the attributes shared by the three cultivars analyzed in the given berry species. The Venn diagram was computed using R software version 4.2.2 (R Core Team, 2022). RATA intensities were interpreted on a 10-point scale; not cited terms were scored as “0”, thus, a non-selected term was considered equivalent to the “not perceivable” label (intensity = 0). A two-way ANOVA model (product and replicate) was applied to RATA intensity scores, only on attributes already selected for the Venn diagram (second and third citation tertile). A Tukey’s post hoc test was calculated to test the differences between cultivars with the significance level fixed at p < 0.05. Mean RATA intensity values were used to generate a spider plot representing the sensory profiles of each cultivar.

3. Results

3.1. Sensory Terms Literature Research and Selection

3.1.1. Sensory Descriptors for Blueberry

In earlier reports, blueberry has been described as “fresh fruit” by Rosenfeld et al. [14], providing a list of selected sensory attributes, and as “juice” [15] with a particular focus on its flavors. Furthermore, blueberry texture has been investigated through sensory analysis, focusing on crispness [16]. For blueberry, we selected 29 terms: 17 descriptors for flavor (berry, blueberry, citrus, earthy/musty, fermented, floral, fruity, grassy, green, minty, overripe fruit, pungent, acid, spicy, strawberry, sweet, watery), three for taste (sweet, acid, bitter), eight to chemesthesis/mouthfeel (astringent, fibrous, firm, juicy, metallic, skin persistence, seedy, throat burn), and freshness as a typical fruit metadescriptor [17] (Table 1). Each attribute was described in seven languages, to allow panelists’ and consumers’ evaluations in their native language, while maintaining the original meaning (Table 2).

Table 1.

Blueberry sensory attributes in English, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Spanish and Turkish (References: a: Bett-Gaber and Lea, 2013 [15]; b: Ferrao et al., 2020 [18]; c: Gilbert et al., 2015 [19]; d: Cheng et al., 2020 [20], e: Rokayya et al., 2020 [21]; f: Asănică, 2018 [22]; g: Peneau et al., 2007 [17]; h: Rosenfeld et al., 1999 [14]; i: Sater et al., 2021 [23]; BPE: BreedingValue Project Experts).

Table 2.

Descriptions of blueberry sensory attributes in English, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Spanish and Turkish.

3.1.2. Sensory Descriptors for Raspberry

Relatively few studies have investigated the sensory properties of raspberry [24,25]. Studies of raspberry odor-active compounds have determined that the most important was raspberry ketone (4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-butane-2-one) and αaL- and βbT-ionone, with linalool and geraniol peculiar to some of the tested varieties [26]. In our study, 29 terms were selected for raspberry: 19 attributes for flavor (acid, berry, caramel, chemical, citrus, cloying, fermented, floral, fruity, grassy, green, green/tomato, minty, nutty, raspberry, sweet, tropical fruit, watery, woody), three related to taste (sweet, acid, bitter), six to chemesthesis/mouthfeel (astringent, metallic, juicy, fibrous, firm, seedy), and freshness as a typical fruit metadescriptor [17] (Table 3). Each attribute was again described in seven languages to allow panelists’ and consumers’ evaluations in their native language, while maintaining the original meaning (Table 4).

Table 3.

Raspberry sensory attributes in English, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Spanish and Turkish. (References: a: Aaby et al., 2019, [24]; b: Zhang et al., 2021 [27]; c: Villamor et al., 2013 [28]; d: Stavang et al., 2015 [29]; e: Bett-Gaber and Lea, 2013 [15]; BPE: BreedingValue Project Experts).

Table 4.

Descriptions of raspberry sensory attributes in English, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Spanish and Turkish.

3.2. Sensory Evaluation

3.2.1. Blueberry Lexicon Sorting through RATA

Eight of the 29 attributes were in the third tertile (high frequency) of panel citation: blueberry flavor, acid taste, sweet taste, juicy, skin persistence, freshness, acid flavor and sweet flavor. Seven other attributes were used by a minimum of 34% of the panelists: firm, astringent, fibrous, floral, fruity, berry, and green, being thus part of the second tertile (medium frequency). Results showed that six attributes had a low frequency (peculiar traits), and five attributes were not used by the panelists to describe the berries (Table 5).

Table 5.

Frequency counts of the sensory descriptors of blueberry samples. Attributes marked by *** belong to the third tertile, ** belongs to the second tertile, * belongs to the first tertile (peculiar traits).“-“indicates non-used attributes.

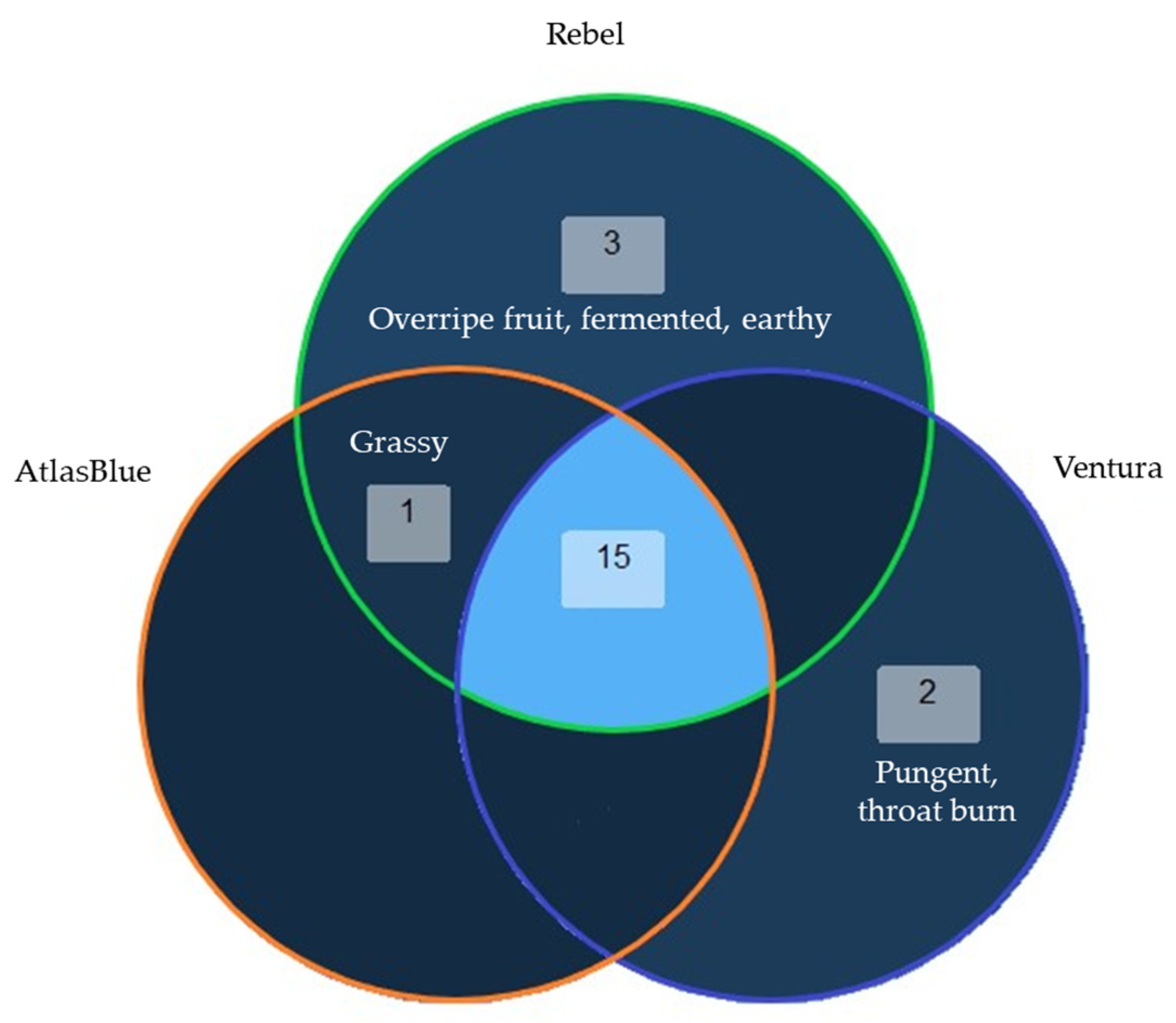

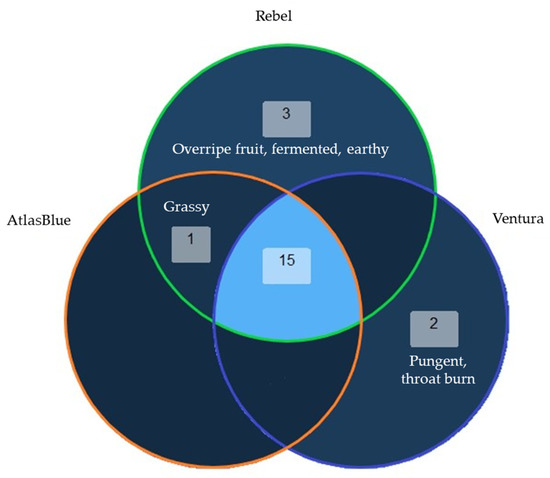

Analyzing RATA data through the Venn diagram showed that several high- and medium-frequency attributes were shared by the three blueberry cultivars, while peculiar traits discriminated them (Figure 2). Fifteen attributes were shared by all the cultivars, and three attributes (overripe fruit, fermented, and earthy/musty) were absent in AtlasBlue and Ventura. Two attributes (throat burn and pungent), were present in Ventura only, and one attribute (grassy), was common to AtlasBlue and Rebel.

Figure 2.

Venn diagram based on the attributes chosen by at least 34% of the panelists to describe blueberry cultivars. Numbers inside the diagram represent the number of terms selected by the panelists.

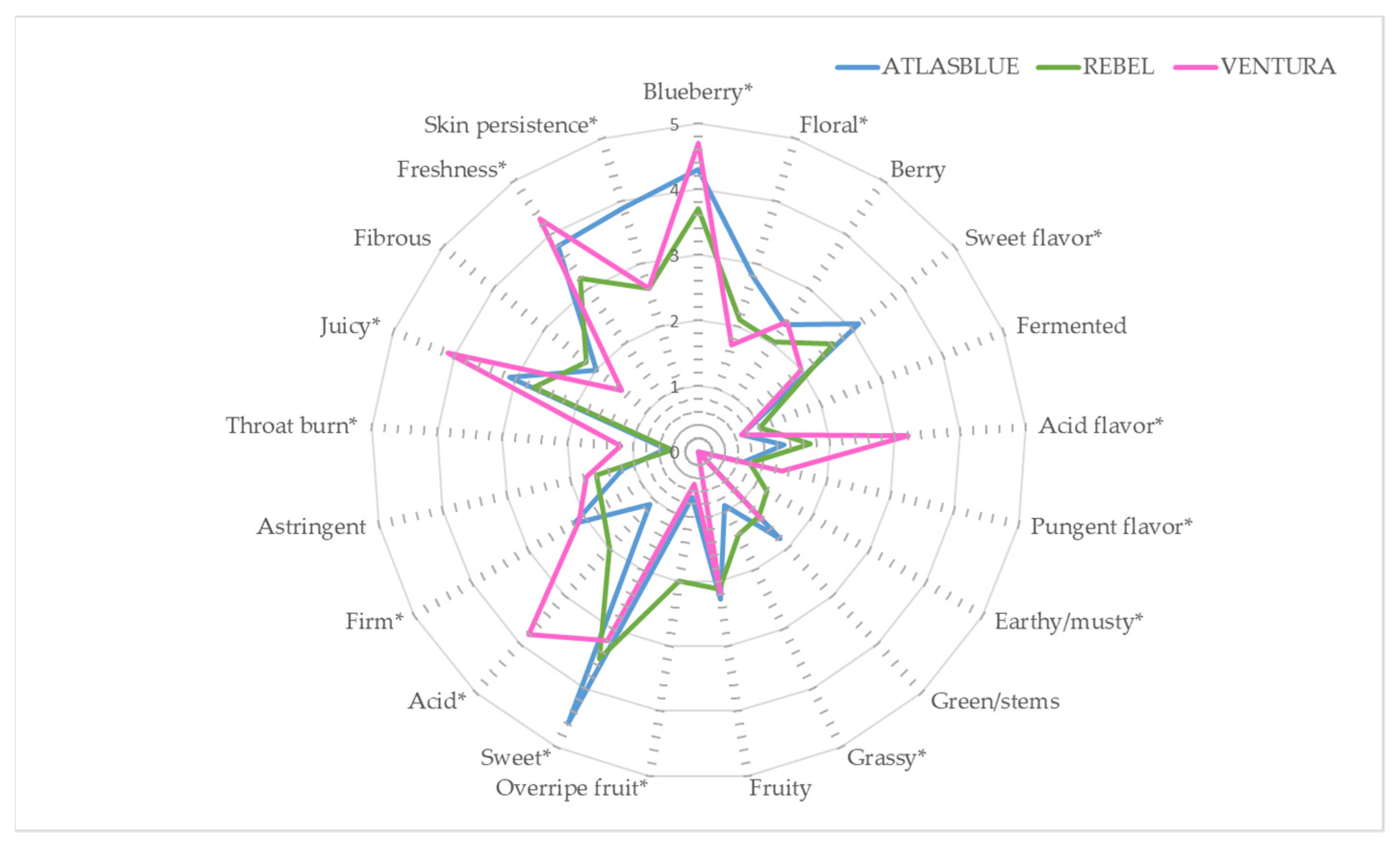

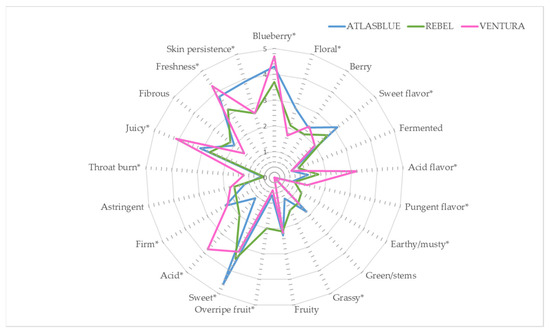

3.2.2. Blueberry Cultivar Profiles

The three blueberry cultivars differed in six of the “high frequency” attributes with Ventura recording the highest intensity of juiciness, acidity, freshness and blueberry flavor, while AtlasBlue prevailed for sweetness and sweet flavor (Figure 3). “Medium frequency” attributes also contributed to define the cultivar profiles; Rebel recorded the lowest firmness and the highest grassy flavor, Ventura was the least fibrous, and AtlasBlue registered the most intense floral flavor. Finally, peculiar traits, having generally a low intensity, contributed to cultivar discrimination; Ventura showed the highest throat burn and pungency, and Rebel showed the highest fermented, earthy/musty, and overripe fruit flavors.

Figure 3.

Spider plot of blueberry RATA intensity scores by cultivars on a 10-point scale (0–9). Significant differences (p < 0.05) between cultivars are marked by *.

Repeatability did not have any significant effect on replicate.

3.2.3. Raspberry Lexicon Sorting through RATA

Six of the 29 raspberry attributes were in the third tertile (high frequency) of panel citation: raspberry flavor, sweet taste, acid taste, astringent, juicy, and seedy. Eight additional attributes were used by a minimum of 34% of the panelists: freshness, firm, fruity, cloying, green, floral flavors, fibrous, and grassy, and belonged to the second tertile. Of the remaining attributes, two (bitter and chemical flavors) overcome this threshold at least in one cultivar. The attributes metallic, woody, watery and caramel flavors had a low frequency (peculiar traits), and the attributes berry, citrus, fermented, green tomato, minty, nutty, sweet and tropical fruit flavors were not used by the panelists to describe the berries (Table 6).

Table 6.

Frequency counts of the sensory descriptors of raspberry samples. Attributes marked by *** belong to the third tertile, ** means belonging to the second tertile, * means belonging to the first tertile (peculiar traits).“-“indicates non-used attributes.

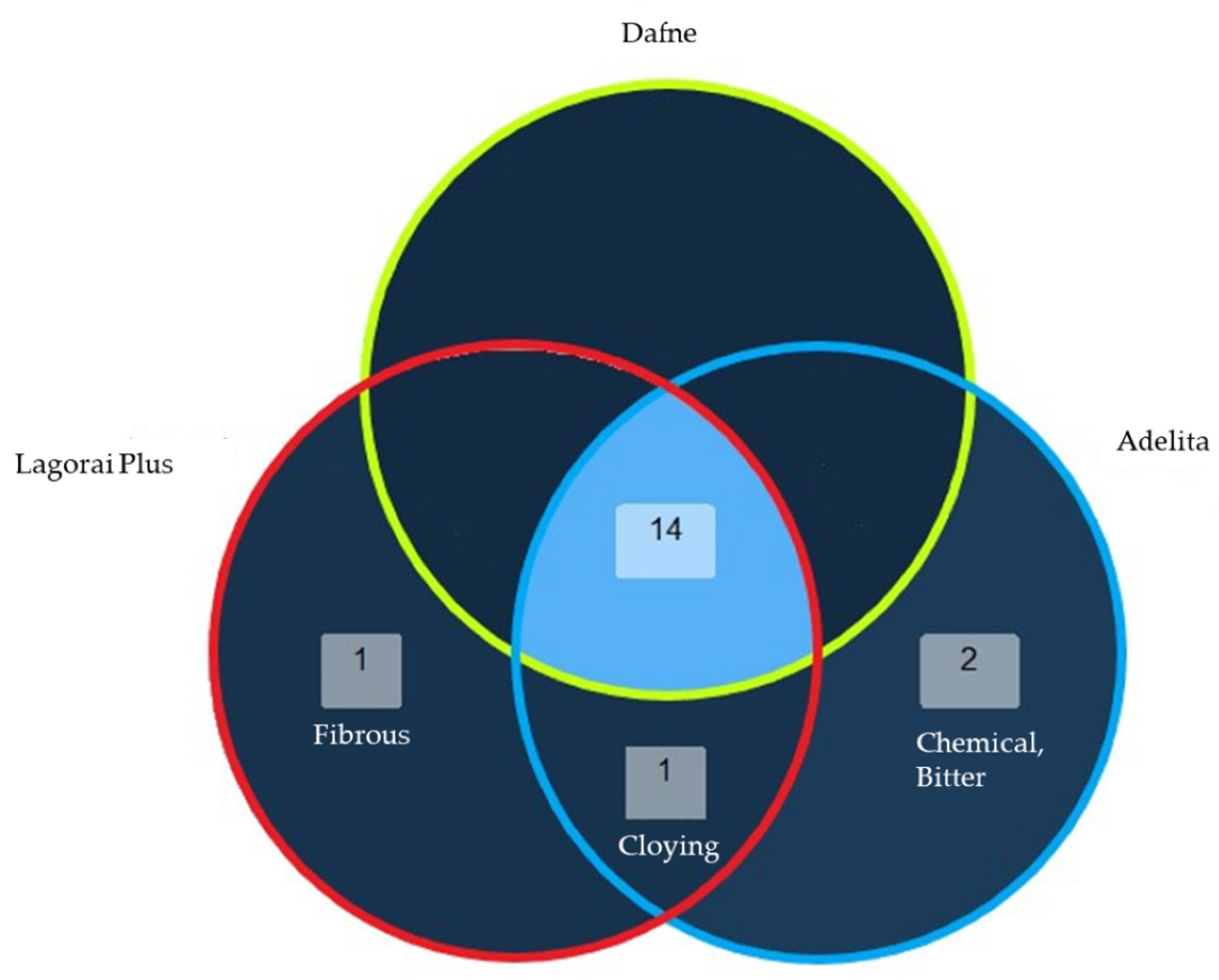

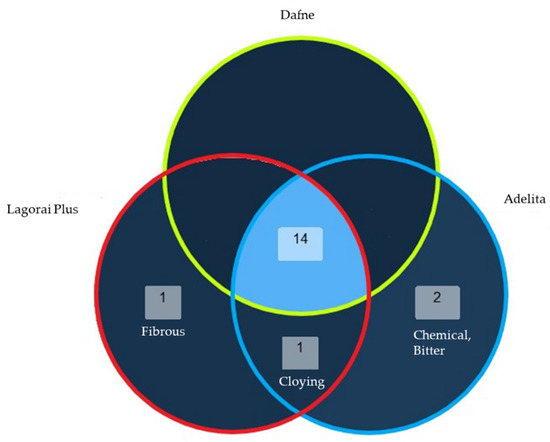

The Venn diagram of the raspberry RATA data showed that 14 “medium and high-frequency” attributes were common to the three cultivars. Only two cultivars were discriminated by peculiar traits (Lagorai Plus and Adelita) (Figure 4). Two attributes, chemical and bitter, were absent in Lagorai Plus and Dafne, and one attribute, cloying, was common to Lagorai Plus and Adelita. The attribute fibrous was present in Lagorai Plus only.

Figure 4.

Venn diagram based on the attributes chosen by at least 34% of the panelists to describe raspberry cultivars. Numbers inside the diagram represent the number of terms selected by the panellists for each cultivar.

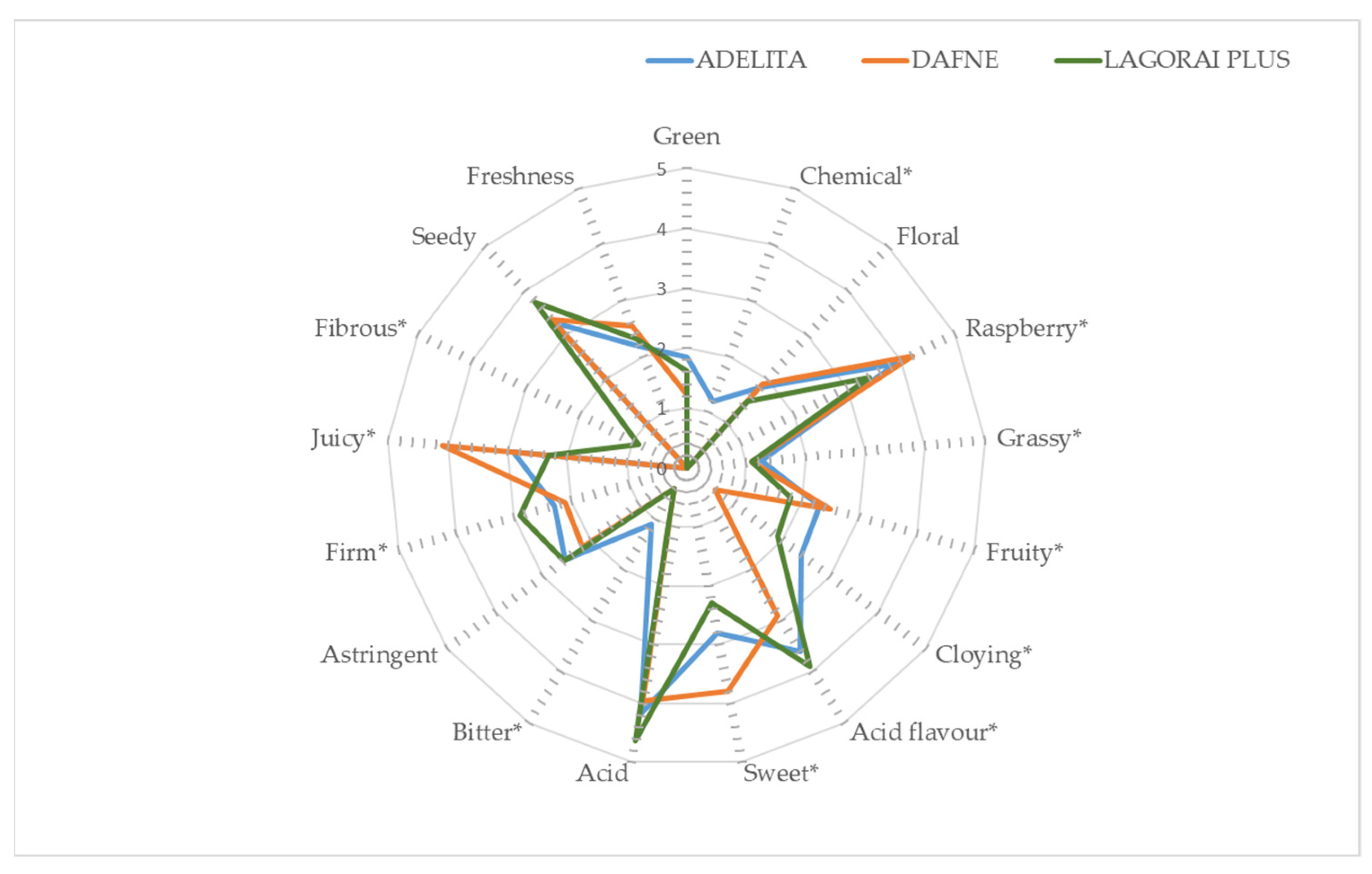

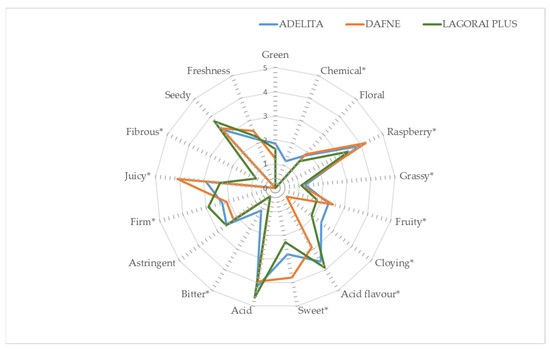

3.2.4. Raspberry Cultivar Profiles

The three raspberry cultivars tested were different for four of the “high frequency” attributes; Dafne and Adelita showed the highest intensity of raspberry flavor, Dafne also showed the highest juiciness and sweetness, while Lagorai Plus was the most acid (Figure 5). “Medium frequency” attributes also contributed to define cultivar profiles; Lagorai Plus showed the highest firmness and fibrousness, Dafne was mainly fruity, and Adelita was mainly cloying and grassy. Among peculiar traits showing generally low intensity, Adelita expressed the highest bitter and chemical flavors.

Figure 5.

Spider plot of raspberry RATA intensity scores by cultivars on a 10-point scale (0–9). Significant differences (p < 0.05) between cultivars are marked by *.

Repeatability did not have any significant effect on replicate.

4. Discussion

4.1. Berries Lexicon Development

This study led to the identification of 29 sensory descriptors perceived during eating (basic tastes, texture, flavors) potentially present in blueberry, and the same number in raspberry, evidencing an expected high range of sensory stimuli provided by the berries. As suggested by Suwonsichon [4], lexicon creators have to clearly illustrate each chosen term to panelists, referring to previous experiences, and/or providing standard references to support panelists’ term/sensation association, to validate the effectiveness and the exhaustiveness of the terms list.

4.2. Basic Tastes

In this study, the lexicon was validated by panelists through RATA, as applied on three blueberry and three raspberry cultivars selected for providing a wide range of product variability. Basic tastes such as sweet and acid are clearly perceived in most fruit including berries, due to the relevant presence of sugars (and polyalcohols) and organic acids [30]; also in this study, they were cited at high frequency both in blueberry and raspberry. Bitter recorded lower frequencies, being not typical of these fruits [15,28]. However, as it affects consumers’ liking [28] it is worth assessing, even if only slightly perceived. Indeed, the bitter perception has a recognized genetic base, with about one third of consumers (supertasters), particularly sensitive to bitterness [31]. In our study, bitter taste was highlighted by more than one third of assessors only in the raspberry cultivar “Lagorai”.

4.3. Flavors

Berries are particularly rich in odor active compounds, determining odor and flavors. For raspberry, the most impacting compound, responsible for the typical raspberry-like odor, is 4-(4-Hydroxyphenyl) butan-2-one, the “raspberry ketone” [26,32]. While the blueberry flavor is a mix of odor compounds not corresponding to a single odor sensation, among them, the ones affecting the overall liking were reported to be 1-hexanol and 2-undecanone, responsible, respectively, for fruity/sweet/green, and fruity/floral sensations [18]. However, in this study, both blueberry and raspberry flavors were clearly recognized by judges who cited them highly (over 80% citation frequency). Additional cited flavors in blueberry were acid and sweet, and at low frequencies, floral, fruity, berry and green, which are also responsible for blueberry flavor. Additional cited flavor notes in raspberry were fruity, cloying, green, floral and grassy.

4.4. Mouthfeel

Among texture descriptors, juiciness was highly cited for both berries, indeed it has been considered a positive trait often related to liking [20]. Firmness was also frequently cited but at a low intensity due to the general features of these berries. Fibrousness was also cited but among the low-frequency attributes. Other texture attributes were berry type-specific: skin persistence in blueberry, seedy in raspberry. Astringency, another key attribute of fruit, related to the concentration of substances such as polyphenols [33], received medium frequency citations in blueberry and high in raspberry. Freshness, an important metadescriptor of sensations related to just-harvested fruits [17,29] was cited at high frequency in blueberry, and medium frequency in raspberry, suggesting the perishable nature of raspberry.

4.5. RATA Analysis

RATA was confirmed to be a quick and valuable alternative to the complicated traditional sensory lexicon development, as highlighted by Leone et al. [10]. Indeed, RATA has been considered a tool to produce data in line with consumer perceptions with a short time frame for data acquisition [34]. Moreover, the advantage of RATA resides in the ease of lexicon development since the terms selected are directly applied and rated [35]. Our descriptive and comparative test on blueberry and raspberry cultivars confirmed the selected lexicon efficiency through sample discrimination highlighted by attributes’ intensities. Notably, not only high-/medium-frequency terms help discriminate between cultivars, but also peculiar traits, underlining their important role in describing food products. Thus, RATA was useful, especially in correctly identifying discriminative, peculiar traits of the product analyzed.

4.6. Pros and Goals

The main novelty of this research is the development of a comprehensive multilingual lexicon for raspberries and blueberries, the sensorial quality of which has been little investigated so far. Moreover, it provides a fundamental sensory tool not only for international research studies involving different partners and countries but also for breeders and the food industry to assess the potential of new varieties in the fresh fruit market, necessary in modern breeding programs aimed at improving fruit sensorial and nutritional quality [36]. Lexicon development should be seen as a necessary starting point, from which other sensory studies can evolve using well-documented terms directly or adding/adapting new terms to each individual work [37]. The lexicon developed in the present study to describe the sensory properties of fresh raspberry and blueberry will be applied in further tests in the frame of the BreedingValue project in different European countries [11], both to assess the translation relevance and to provide the opportunity for further lexicon integration.

5. Conclusions

The seven-language lexicon developed in this study can contribute to systematize blueberry and raspberry sensory evaluation at an international level. A reference sensory lexicon is useful to ease producer-consumer interaction; moreover, international markets and scientific collaborations need a multilingual lexicon to share a common meaning of each term. This research provides a comprehensive list of terms for blueberry and raspberry sensory evaluation in some of the world’s most spoken languages, such as English, Spanish and French, and in additional languages spoken in relevant berry production countries, such as Germany, Italy, Finland, and Turkey. The proposed lexicon can be used as a tool for planning panel training and consumer tests, opening up further possibilities to enrich the lexicon based on additional attributes emerging from local experience, or evaluation of new genotypes. Indeed, the lexicon, developed in English and validated by an Italian expert panel, can be applied in other languages. The developing procedure presented in this study, which starts from English, is the “hub” connecting several “spokes”, i.e., the languages, and easily allows both integrating the list of sensory terms and add more languages. The international BreedingValue consortium collaboration led to the creation of this unique tool, setting the basis for a consistent sensory evaluation of blueberry and raspberry fruits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N L., E.S., M.C. (Marta Cianciabella) and S.P.; methodology, S.P., B.M. and S.K; validation, M.C. (Medoro Chiara), M.C. (Marta Cianciabella), E.G. and S.P.; investigation, B.D., D.A.S., M.F., M.H., N.L., N.E.K., L.M., M.C. (Marta Cianciabella), S.M., K.O., S.O. (Saverio Orsucci), S.O.(Sonia Osorio), E.S., D.P., S.R., J.F.S.-S., G.S., C.S., B.U. and P.Z.; data curation, N.L., M.C. (Marta Cianciabella) and M.C. (Medoro Chiara) writing—original draft preparation, N.L., M.C. (Marta Cianciabella) and E.S.; writing—review and editing, M.C. (Marta Cianciabella), M.C. (Medoro Chiara), E.S., S.K., K.O., S.R., D.P. and N.E.K.; funding acquisition, B.M. and S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 101000747.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Stone, H.; Sidel, J. Sensory Evaluation Practices, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-12-672690-9. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 13300-2; Sensory Analysis—General Guidance for the Staff of a Sensory Evaluation Laboratory—Part 2: Recruitment and Training of Panel Leaders. 2006. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/36388.html (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Lawless, L.J.R.; Civille, G.V. Developing Lexicons: A Review. J. Sens. Stud. 2013, 28, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwonsichon, S. The Importance of Sensory Lexicons for Research and Development of Food Products. Foods 2019, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Chambers, E. Lexicon for multiparameter texture assessment of snack and snack-like foods in English, Spanish, Chinese, and Hindi. J. Sens. Stud. 2019, 34, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E.; Lee, J.; Chun, S.; Miller, A.E. Development of a Lexicon for Commercially Available Cabbage (Baechu) Kimchi. J. Sens. Stud. 2012, 27, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.S.; Chambers, E.; Wang, H.W. Flavor lexicon development (in English and Chinese) and descriptive analysis of Sichuan pepper. J. Sens. Stud. 2021, 36, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delarue, J. The use of rapid sensory methods in R&D and research: An introduction. In Rapid Sensory Profiling Techniques and Related Methods; Julien, D., Ben, L., Michel, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, S.; Beresford, M.; Paisley, A.; Antunez, L.; Vidal, L.; Cadena, R.; Gimenez, A.; Ares, G. Check-all-that-apply (CATA) questions for sensory product characterization by consumers: Investigations into the number of terms used in CATA questions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 42, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; De Domenico, S.; Medoro, C.; Cianciabella, M.; Daniele, G.M.; Predieri, S. Development of Sensory Lexicon for Edible Jellyfish. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senger, E.; Osorio, S.; Olbricht, K.; Shaw, P.; Denoyes, B.; Davik, J.; Predieri, S.; Karhu, S.; Raubach, S.; Lippi, N.; et al. Towards smart and sustainable development of modern berry cultivars in Europe. Plant J. 2022, 111, 1238–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, P.; Cicerale, S.; Pang, E.; Keast, R. Developing a strawberry lexicon to describe cultivars at two maturation stages. J. Sens. Stud. 2018, 33, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, A.K.L.; de Graaf, C.; Scholten, E.; Stieger, M.; Piqueras-Fiszman, B. Comparison of Rate-All-That-Apply (RATA) and Descriptive sensory Analysis (DA) of model double emulsions with subtle perceptual differences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, H.J.; Meberg, K.R.; Haffner, K.; Sundell, H.A. MAP of highbush blueberries: Sensory quality in relation to storage temperature, film type and initial high oxygen atmosphere. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1999, 16, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bett-Garber, K.L.; Lea, J.M. Development of Flavor Lexicon for Freshly Pressed and Processed Blueberry Juice. J. Sens. Stud. 2013, 28, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaker, K.M.; Plotto, A.; Baldwin, E.A.; Olmstead, J.W. Correlation between sensory and instrumental measurements of standard and crisp-texture southern highbush blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum L. interspecific hybrids). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 2785–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peneau, S.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Escher, F.; Nuessli, J. A comprehensive approach to evaluate the freshness of strawberries and carrots. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2007, 45, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrao, L.F.V.; Johnson, T.S.; Benevenuto, J.; Edger, P.P.; Colquhoun, T.A.; Munoz, P.R. Genome-wide association of volatiles reveals candidate loci for blueberry flavor. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 1725–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.L.; Guthart, M.J.; Gezan, S.A.; de Carvalho, M.P.; Schwieterman, M.L.; Colquhoun, T.A.; Bartoshuk, L.M.; Sims, C.A.; Clark, D.G.; Olmstead, J.W. Identifying Breeding Priorities for Blueberry Flavor Using Biochemical, Sensory, and Genotype by Environment Analyses. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.L.; Olmstead, J.W.; Colquhoun, T.A.; Levin, L.A.; Clark, D.G.; Moskowitz, H.R. Consumer-assisted Selection of Blueberry Fruit Quality Traits. Hortscience 2014, 49, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokayya, S.; Jia, F.G.; Li, Y.; Nie, X.; Xu, J.W.; Han, R.; Yu, H.Y.; Amanullah, S.; Almatrafi, M.M.; Helal, M. Application of nano-titanum dioxide coating on fresh Highbush blueberries shelf life stored under ambient temperature. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 137, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asanica, A. Sensorial evaluation of 26 highbush blueberry varieties in romania. Sci. Pap. -Ser. B-Hortic. 2018, 62, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Sater, H.; Ferrao, L.F.V.; Olmstead, J.; Munoz, P.R.; Bai, J.; Hopf, A.; Plotto, A. Exploring environmental and storage factors affecting sensory, physical and chemical attributes of six southern highbush blueberry cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 289, 110468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaby, K.; Skaret, J.; Roen, D.; Sonsteby, A. Sensory and instrumental analysis of eight genotypes of red raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) fruits. J. Berry Res. 2019, 9, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.P.; Yang, G.; Sun, L.Y.; Song, X.S.; Bao, Y.H.; Luo, T.; Wang, J.L. Comprehensive Evaluation of 24 Red Raspberry Varieties in Northeast China Based on Nutrition and Taste. Foods 2022, 11, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.; Poll, L.; Callesen, O.; Lewis, M. Relations between the content of aroma compounds and the sensory evaluation of 10 raspberry varieties (Rubus-idaeus L). Acta Agric. Scand. 1991, 41, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.T.; Lao, F.; Bi, S.; Pan, X.; Pang, X.L.; Hu, X.S.; Liao, X.J.; Wu, J.H. Insights into the major aroma-active compounds in clear red raspberry juice (Rubus idaeus L. cv. Heritage) by molecular sensory science approaches. Food Chem. 2021, 336, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamor, R.R.; Daniels, C.H.; Moore, P.P.; Ross, C.F. Preference Mapping of Frozen and Fresh Raspberries. J. Food Sci. 2013, 78, S911–S919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavang, J.A.; Freitag, S.; Foito, A.; Verrall, S.; Heide, O.M.; Stewart, D.; Sonsteby, A. Raspberry fruit quality changes during ripening and storage as assessed by colour, sensory evaluation and chemical analyses. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 195, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Huang, C.H.; Yang, B.R.; Kallio, H.; Liu, P.Z.; Ou, S.Y. Regulation of phytochemicals in fruits and berries by environmental variation-Sugars and organic acids. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoshuk, L.; VB, D.; IJ, M. PTC/PROP tasting: Anatomy, psycho-physics, and sex effects. Physiol. Behav. 1994, 858–875. [Google Scholar]

- Aprea, E.; Biasioli, F.; Gasperi, F. Volatile Compounds of Raspberry Fruit: From Analytical Methods to Biological Role and Sensory Impact. Molecules 2015, 20, 2445–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajec, M.R.; Pickering, G.J. Astringency: Mechanisms and perception. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 858–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niimi, J.; Collier, E.; Oberrauter, L.; Sorensen, V.; Norman, C.; Normann, A.; Bendtsen, M.; Bergman, P. Sample discrimination through profiling with rate all that apply (RATA) using consumers is similar between home use test (HUT) and central location test (CLT). Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Bruzzone, F.; Vidal, L.; Cadena, R.S.; Gimenez, A.; Pineau, B.; Hunter, D.C.; Paisley, A.G.; Jaeger, S.R. Evaluation of a rating-based variant of check-all-that-apply questions: Rate-all-that-apply (RATA). Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 36, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbadini, S.; Capocasa, F.; Battino, M.; Mazzoni, L.; Mezzetti, B. Improved nutritional quality in fruit tree species through traditional and biotechnological approaches. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 117, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.; Chambers, E.; Han, I. Development of a Sensory Flavor Lexicon for Mushrooms and Subsequent Characterization of Fresh and Dried Mushrooms. Foods 2020, 9, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).