Abstract

Objective: We aimed to develop multidisciplinary recommendations for the management of cardiovascular–kidney–metabolic (CKM) syndrome in Spain. Methods: The Delphi method was used. The final questionnaire comprised 61 statements that were assessed using a 9-point Likert scale of agreement, from 1 = fully disagree to 9 = fully agree. A consensus was reached when 80% of answers in all specialties were in the range of 7–9. The overall median was used as a measure of the strength of agreement. Results: A total of 70 (97%) panelists met the selection criteria and completed two rounds, including cardiology (13), endocrinology (12), internal medicine (12), nephrology (14), and primary care (19). Among the 61 statements, a consensus was reached in 54 (89%). The consensus to be highlighted included the following: an excess and/or dysfunction of adipose tissue as the initial driver of CKM syndrome (median 8), CKM syndrome that includes both patients at risk (median 8) and those with existing CVD (median 8), coordination of patient management by the family medicine physician (median 9), the essential role of primary prevention in maintaining CKM health (median 9), the administration of drugs with demonstrated CKM benefit in both early-stage patients (median 9) and those in the advanced stages of the syndrome (median 9), and the importance of lifestyle measures (median 9), with a focus on intensive weight loss (median 9). Conclusions: This Delphi consensus offers multidisciplinary recommendations highlighting the importance of early recognition, integrated management, and the implementation of preventive and therapeutic strategies with established cardiorenal and metabolic benefits.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular–kidney–metabolic (CKM) syndrome is defined by the American Heart Association (AHA) Presidential Advisory as “a systemic disorder characterized by pathophysiological interactions among metabolic risk factors, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and the cardiovascular system leading to multiorgan dysfunction and a high rate of adverse cardiovascular outcomes” [1]. This framework emphasizes the interplay of these conditions rather than treating them individually, recognizing shared drivers such as excess adiposity and inflammation. It includes both subjects at risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and those with existing CVD [1]. The AHA classifies CKM syndrome into five stages that guide its management [1]: stage 0, absence of CKM risk factors; stage 1, excess and/or dysfunctional adiposity; stage 2, metabolic risk factors and/or moderate- to high-risk CKD; stage 3, subclinical CVD in patients with excess/dysfunctional adiposity, metabolic risk factors, or CKD; and stage 4, clinical CVD in patients with excess/dysfunctional adiposity, metabolic risk factors or CKD.

The burden of CKM syndrome is substantial. In the United States (US), the age-adjusted prevalence in adults is estimated to be 11% for stage 0, 28% for stage 1, 47% for stage 2, 5% for stage 3, and 8% for stage 4. Advanced stages (i.e., stage 3 or 4) are associated with adverse social determinants, such as lower education and income [2,3]. An analysis of time trends in the U.S. revealed an increase in the overall prevalence of CKM syndrome from 1988 to 2018 in both sexes, with greater increases in stage 3 disease among men [4]. The prevalence also increases with age, reaching 50% for advanced stages in individuals aged ≥65 years [5].

Beyond its epidemiological impact, CKM syndrome has major clinical and economic consequences. It is linked to higher health care costs [6,7] and to a marked excess of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality [2,8]. Mortality increases with increasing CKM stage, with a disproportionately high number of deaths associated with advanced stages [2].

Given the complexity of the interplay between the various risk factors and clinical conditions involved in CKM syndrome and their management, there is a growing call to move away from fragmented specialty-based care toward integrated, multidisciplinary models capable of addressing the condition holistically [1,9,10]. While international frameworks, such as those from the AHA, provide a foundation, it is critical to adapt recommendations to the realities of each health care system.

The multidisciplinary consensus presented herein aimed to develop recommendations for the comprehensive evaluation and management of CKM syndrome in Spain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This project was conducted using a modified Delphi method with two rounds. The first Delphi round took place between September and October 2024, and the second round occurred in November 2024. This technique is employed to make recommendations when evidence is limited or contradictory or when there is an overload of information [11]. It has been widely used in health research for various purposes, including clarifying particular issues in health service organizations, defining the role of different professionals in interdisciplinary processes, and developing criteria for the appropriateness of interventions [11,12]. The essential characteristics of the Delphi method are anonymity, iteration, controlled feedback, and statistical aggregation of group responses [11,12], which makes it ideal for addressing emerging and complex topics [12] such as the objective of this project. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Severo Ochoa University Hospital (Leganés, Spain; Reference 09/24). All health care professionals who participated in the Delphi survey were informed of the nature of the project and agreed to participate by signing a contract.

2.2. Selection of Experts

The coordinator of the project selected a group of six experts representing the specialties involved in the project: Cardiology, Endocrinology, Internal Medicine, Nephrology, and Family Medicine. The selection of cardiology, nephrology, and endocrinology was based on the components of the syndrome. We included family and internal medicine because they are cross-sectional medical specialties. Family medicine is especially important because it is usually the gateway to the health system and allows patients to navigate the health care system, including specialist and hospital care coordination and follow-up. Regarding internal medicine, these specialists in adult medicine are specially trained to solve diagnostic problems, manage severe long-term illnesses, and help patients with multiple, complex chronic conditions, such as CRM syndrome. This scientific committee proposed potential experts for screening and to eventually be included in the Delphi, with a target of 12 participants for each specialty involved, except for Family Medicine, which had a target of 20 participants; a greater representation was considered necessary given the key role of family medicine physicians in the early detection and coordination of CKM care.

To be included, participants had to meet the following criteria: have at least 10 years of clinical experience, devote at least 70% of their time to clinical practice, and be active members of a scientific society. They also had to have research experience, as evidenced by at least one CKM syndrome-related publication or communication at a scientific congress in the past five years or accreditation by the Spanish National Commission for the Evaluation of Research Activity and teaching experience.

2.3. Development of the Questionnaire

On the basis of the AHA Presidential Advisory on CKM health and a narrative review of the current medical literature, the scientific committee performed and agreed to a questionnaire of 58 statements. They were self-developed by the authors based on their broad knowledge and clinical experience with CRM patients, taking into account the main challenges to be faced, and grouped into three blocks addressing different issues related to the comprehensive management of these patients: (1) evaluation (21 statements): definition, screening, assessments, diagnosis and staging, and health resources; (2) overall management (19 statements): early, comprehensive and interdisciplinary management; role of nurses; and education; and (3) therapeutic approach (18 statements): preventive measures, interventions (lifestyle, pharmacological, and rehabilitation), and follow-up.

2.4. Consensus Level

Each recommendation was rated anonymously by the participants using a 9-point Likert scale of agreement, from 1 (“completely disagree”) to 9 (“completely agree”).

A consensus for a specific recommendation/statement was reached when at least 80% of the answers were in the range of 7–9 on the Likert scale. This threshold is within the upper limit of the range commonly used in the literature (50–97%) [13]. To achieve an overall consensus, that threshold had to be reached by each of the specialties involved individually.

The questionnaire was administered via a dedicated website. The results of the first round were analyzed and discussed by the scientific committee. Recommendations/statements with a lack of consensus in any of the specialties involved were assessed by the participants in the second round. Statements that did not achieve consensus in the first round were re-evaluated by the scientific committee to determine whether this was due to the ambiguity of the statement itself, in which case it was reformulated, or because the topic itself was controversial.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Absolute and relative frequencies were used to describe the characteristics of the participants. The final results of the rounds are presented as the percentage of agreement for each specialty (i.e., the proportion of participants who rated the item from 7 to 9 on the Likert scale), the percentage of overall agreement, and the overall median of agreement as a measure of the strength of agreement.

All the data were analyzed using MS Excel Office 365- version 2406.

3. Results

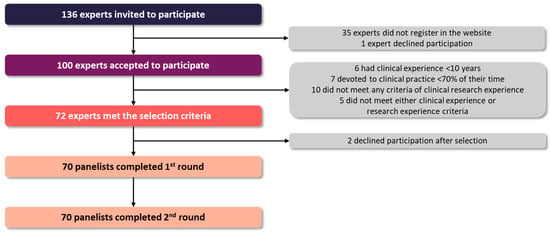

A total of 136 experts were invited to participate; 100 (73.5%) accepted the invitation, and 70 (51.5%) met the selection criteria (Figure 1), including 13 cardiologists, 14 nephrologists, 12 endocrinologists, 12 internists, and 19 family physicians. All the participants had prior research experience, with almost half of them having published three or more articles in the past five years (Table S1). Most panelists worked in academic medical centers (87%), had tutored medical residents in the past 5 years (70%), and worked at a highly specialized and complex care hospital (46%) or a community health center (26%).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

3.1. Overall Results

Seventy panelists (100%) completed both rounds. Among the initial 58 statements, a consensus was not reached for 19 (32.8%), mainly because 15 statements were not agreed upon among the Family Medicine panelists. After reviewing the results of the first round, two statements (items #4 and #13) were split by the scientific committee into five, leading to 22 statements that were evaluated in the second round. In addition, 5 statements were reworded to improve clarity. After two rounds, a consensus was reached in 54 (88.5%) statements.

3.2. Evaluation of Patients with CKM Syndrome

A consensus was reached in 20 (83.3%) of the 24 statements in this section (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation of patients with cardio–kidney–metabolic syndrome.

There was a consensus on the definition of CKM syndrome as a complex systemic condition that arises from the multifaceted pathophysiological interactions among metabolic risk factors, CKD, and the cardiovascular system (9), which is pathologically rooted in the excess and/or dysfunction of adipose tissue (8). This concept of CKM syndrome is intended to facilitate the multidisciplinary care process (9) and includes individuals at risk of CVD (8) and those with existing CVD (8).

The experts agreed that screening should be performed in patients with at least one risk factor for any of the CKM conditions (9), and the examinations should include standard physical evaluation (8), key metabolic (including the index for liver fibrosis FIB-4) and renal function parameters (9) and, when clinically indicated, electrocardiography and echocardiography (9). Consensus was also reached for establishing the presence of the cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic conditions of CKM syndrome (see definitions in questions 10 to 12 (Table 1)) and for considering that the presence of one CKM condition should lead to ruling out the other two conditions (9).

There was a consensus that once CKM syndrome is diagnosed, it should be staged according to cardiovascular and renal risks (8). However, the panelists did not reach a consensus on which AHA stages were the appropriate ones (8) because the agreement among Family Medicine physicians was only 79%.

Panelists also reached a consensus on several procedural issues, such as creating a basic analytic profile (9), systematically incorporating these parameters into any analysis (8.5), establishing alerts on the basis of those parameters in electronic health records (9) and coding a diagnosis of CKM in the computer systems (9). The panelists also agreed that the laboratory department (9) and health care managers (9) need to improve the available resources.

There was no consensus about the need for an app aimed at health care professionals (8) or patients (7) to improve the health care of patients with CKM syndrome; none of the specialties reached the threshold of consensus in these two items.

3.3. Overall Management of Patients with CKM Syndrome

A consensus was reached for all but one of the 19 statements devoted to overall management (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overall management of patients with cardio–kidney–metabolic syndrome.

There was consensus on several general measures for its overall management: the need for an early and comprehensive approach (9) aimed at preventing progression and delaying the development of complications (9); the adaptation to clinical scenarios and comorbidities (9) but also to advanced age and the presence of frailty (9); the inclusion of integrated care circuits (9), avoiding consultations with multiple specialists (9) and encouraging multidisciplinary face-to-face consultations; and the provision of a quick answer by referents of each specialty to any referral (9).

With respect to the role of nurses, there was a consensus that they play key roles in anamnesis, physical examination, lifestyle recommendations and patient education (9), as well as in coordination with physicians, in follow-up plans (9). However, a consensus was not reached on their role in CKM screening, largely because of a lack of agreement among Family Medicine physicians (79%). Coordination across specialists involved in the management of CKM syndrome should be led by Family Medicine physicians (9).

There was also a consensus on some procedural issues: the need for quality indicators (9), the usefulness of telemedicine for self-management and communication (9), and the need for a single computer system accessible to all specialists (9).

Finally, the panel underscored the central role of education in CKM management. Educational efforts should extend to the general population by reinforcing primordial prevention strategies (9), to patients by fostering self-care and adherence to therapeutic recommendations (9), and to health care professionals and managers by strengthening knowledge and awareness of the syndrome and its clinical implications (9).

3.4. Therapeutic Approach for Patients with CKM Syndrome

The panelists reached a consensus for 16 (88.9%) of the 18 recommendations included in this section (Table 3).

Table 3.

Therapeutic approach for patients with cardio–kidney–metabolic syndrome.

In addition to the clinical situation, the stage of CKM syndrome conditions included the periodicity of monitoring (9), the goals of control (9) and the interventions to be carried out for each condition (9). Primordial prevention was considered essential for maintaining CKM health in individuals without any risk factors (9) and in patients with at least one risk factor associated with CKM syndrome to prevent the occurrence of other risk factors (9).

There was a consensus that, regardless of the overt CKM condition, the approach in patients with CKM syndrome should be comprehensive and intensive (9). The panelists agreed that lifestyle interventions should be implemented in the early stages (9), emphasizing the importance of intensive weight loss at any stage (9). They also agreed that pharmacological management should be based on the corresponding guidelines for each condition (9), emphasizing the use of drugs with beneficial effects on CKM from the early stages (9) to the advanced stages (9); these drugs include sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2is), glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), statins and other lipid-lowering agents, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), among others. There was also a consensus that patients with CKM syndrome and cardiovascular events should be included in comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation programs (9).

There was no consensus on the use of apps for staging and management issues (8) or on telemedicine-related actions on the basis of the stage and psychosocial determinants (8) because they did not reach the consensus threshold by Family Medicine panelists (74% and 79%, respectively). However, panelists agreed on the implementation of telemonitoring for detecting decompensations (8), as well as on computer system functionalities that facilitate the creation of analytic profiles (9) and the definition of monitoring and control objectives (9).

4. Discussion

Although CKM syndrome is a new entity involving several specialties, a broad consensus was reached among all panelists, demonstrating the importance of actively addressing this disorder in clinical practice.

The consensus reached on defining CKM syndrome as a complex systemic entity derived from the interplay of three components and initiated by excess and/or dysfunctional adipose tissue should lead physicians to consider multiorganic involvement and the need for early intervention, starting with primordial prevention. The current difficulty in addressing CKM patients holistically is that it has not yet been considered a separate entity; a siloed strategy is used on the basis of pathologies and specialties. This approximation not only undermines an integrative approach but has also been shown to be minimally effective in the early management of individual pathologies, as demonstrated by the low rate of diagnosis of CKD [14]. Establishing CKM syndrome is a first step toward reducing the progression and improving the prognosis in patients with different CKM pathologies. The importance of thoroughly understanding the characteristics of each condition (not just those specific to each specialty) and associated risks will enable an earlier and more holistic approach.

Addressing CKM patients holistically also implies, as agreed upon, the need for multidisciplinary and integrative care. Limited research on the impact of integrated care on these clinical conditions has yielded promising results. An integrated team-based intervention for patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk for cardiovascular disease events conducted at a U.S. university hospital showed an improvement in the use of evidence-based therapies and control of cardiovascular risk factors after one year compared to the status at program entry [15]. Integrated Care Pathways (ICPs) have been developed for chronic diseases, since they are considered beneficial for reducing hospital admissions and re-admissions and for improving adherence to treatment or quality of life in different pathologies [16]. In Spain, a multidisciplinary team has recently developed a new ICP for spondyloarthritis based on Lean Thinking methodology [17]. Its aim was to establish comprehensive care, communication, planning, quality and practice uniformity as pillars of the approach to this disease. After its implementation, this strategy showed reductions in the number of hospital visits and the frequency of visits to hospital pharmacy, better baseline assessment and education, improved treatment and lifestyle modifications adherence. However, ICPs do not exist for CKM syndrome in Spain; an evolved model of ICP could be transferred to the CKM syndrome framework, focusing on making it applicable to the whole range of CKM patients. In our setting, the implementation of heart failure or cardiorenal units has been shown to improve the management of these patients with treatment optimization and a reduction in the use of health resources, such as hospitalizations [18,19].

Within this integrative framework, Family Medicine physicians play a key role in coordination across specialties. They are recognized by all specialties as the point of entry for CKM patients, care coordinators, and follow-up care providers. Early-stage active management of these patients should lead to reduced workloads for all specialties in the medium and long term and, for CKM patients, better quality of life and fewer outcomes. The integration of Family Medicine physicians in multidisciplinary units, currently composed only of in-hospital specialists, would improve the follow-up of advanced CKM patients and their experience as patients with chronic conditions who frequently access health care services. The generation of new CKM units or teams focused on all stages of CKM syndrome and enriched with the expertise of all specialties, including Family Medicine physicians, experts in CKM, and nurses, would slow the progression of these patients, thereby positively affecting the economic expenses of the health system. In our National Health System with virtually universal health coverage [20], all Family Medicine physicians in a health catchment area share the same referral hospital, which facilitates the development of multidisciplinary protocols and clinical pathways. Moreover, the implementation of unique, electronic clinical platforms, shared by primary and hospital care, would improve coordination, physician and patient experience, and patient outcomes.

Health care managers must play a proactive role in the evolution of our system, advocating for optimized health care models that include tools for the early screening of CKM conditions, easy coding of CKM syndrome, and optimization of control objectives, treatment and follow-up of CKM patients. The implementation of basic indicators would offer objective evidence about the effectiveness of the different measures implemented and their potential extrapolation to other hospital departments, regional health care systems or chronic diseases.

Regarding the therapeutic approach, there was very strong agreement on the essential role of preventive interventions throughout the stages of CKM syndrome, from primordial prevention in the first stage to secondary prevention in the advanced stages. The experts agreed that weight loss is crucial in the management of CKM syndrome; however, this is an area with wide room for improvement. Epidemiological surveys have shown that obesity is underrecognized and undertreated in clinical practice [21], even severe obesity [22]. We fully endorse the AHA’s recommendation to enhance the prevention and management of obesity as a clinical and public health priority and a critical area of training for health care professionals involved in the management of these patients [1]. Although not addressed in our consensus, lifestyle interventions should be extended to other factors, such as smoking, which have been associated with the progression of CKM multimorbidity [23]. Furthermore, fostering CKD diagnosis and integrating MASLD are two future action areas to be prioritized by the medical community because of the underestimation of their prevalence and their impact on cardiovascular risk [14,24].

We also agreed that the use of drugs with beneficial effects on CKM syndrome, such as SGLT2is, GLP-1RAs, or MRAs, should be emphasized from the early to the advanced stages of CKM syndrome. These three medicines, together with statins and blockers of the renin–angiotensin system, are considered the pillars of cardiorenal protection [25,26]. Recent publications have highlighted the evidence for relatively new drugs, such as SGLT2is and GLP-1RAs, across CKM syndrome. These molecules play essential roles in mitigating CV risk and metabolic diseases or disturbances, preserving kidney function and reducing liver inflammation, among other benefits [27]. In particular, SGLT2is have multiple pleiotropic effects, including their antioxidant properties, which translate into clinical benefits and support their central role in the treatment of CKM syndrome [28,29]. International and Spanish authors have proposed SGLT2i usage across the CKM spectrum, from stages 1 to 4 of the AHA classification [28,29]. We must consider the current indications of SGLT2is and recognize that in some CKM conditions—or in earlier stages of others—their benefits are hypothetical, limited or only proven in real life.

Several studies have identified the underuse of SGLT2is and GLP-1RAis in clinical practice [30,31], even in patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease [32]. These findings may reflect a slow uptake of these drugs since more recent studies have shown an increase in their prescription, which seems more marked among cardiologists and nephrologists [33]. In addition, in some clinical contexts, such as in specialized HF units, their use is currently high [34]. Although lack of time, cost, and other factors are associated with the underuse of therapies such as SGLT2is, GLP-1RAs, or MRAs, training specialists in CKM health is essential for overcoming this barrier. The creation of a subspecialty of ‘cardiometabolic medicine’ for internal medicine [35] and a specialty of ‘preventive cardiology’ for cardiologists has been advocated [36]. However, we believe that these initiatives, as isolated measures, maintain the fragmentation of care when seeking integrative management. Interdisciplinary education is needed [37] and should be promoted by scientific societies or other independent scientific organizations or, ideally, included in the curriculum of medical residents of these specialties with specific training on CKM syndrome and its management.

We think that a culture shift towards more intensive use of evidence-based medications and a drive to treat advanced CKM conditions with the sense of urgency they deserve [38], together with the reinforcement of the feeling that each physician seeing a patient is the owner of the process of treatment implementation that must be executed rapidly [39], might favor a slower progression of CKM conditions. A first step towards making this possible could be to leverage SCORE2 [40], SCORE2-OP [41], SCORE2-Diabetes [42], and SCORE2-CKD Add On [43] scores, designed and validated to assess the cardiovascular and renal risks of patients with different CKM conditions, and PREVENT [44] and CKM2S2-BAG [45] scores, which were recently and specifically developed for patients with CKM syndrome, as well as in-hospital treatment initiation and remote and/or algorithmic-based approaches [38].

There was no consensus, overall or in all individual specialties, on the use of apps aimed at health care professionals or patients to improve the management of CKM syndrome. Despite the increasing availability of eHealth tools, their practical implementation in our health care setting is still limited because of the heterogeneity of electronic health records, interoperability issues, and the limited validation of these technologies in longitudinal studies.

Other issues with a lack of consensus, such as the appropriateness of the AHA staging system and the role of nurses in the screening of CKM syndrome, were driven by the results of the Family Medicine panelists. Family Medicine physicians are commonly responsible for a wide range of clinical entities in time-constrained consultations, and they may perceive both the health care apps and the AHA staging system as overly complex or insufficiently easy to handle for their implementation in daily practice. It is also possible that family medicine physicians do not receive adequate training in using these technologies. Incorporating the staging system into information systems would facilitate its use by physicians. In our setting, the role of nurses differs between primary and secondary/tertiary care, is not well-defined and is highly heterogeneous across sites. The extensive development of primary care and community health centers has created a large staff of nurses whose primary focus is health education and preventive activities beyond patient-demand care. In addition, Family Medicine physicians must respond to the demands of patients, which leads to overcrowded consultations [46]. It is necessary to establish preventive objectives in nursing consultations and to evaluate them so that the activity is efficient, as well as to modify the criteria for on-demand care by the physician, also involving nursing in the resolution of patients’ demands for care [47,48]. Overall, these findings highlight the importance of involving primary care professionals in the design and contextual adaptation of CKM care pathways and tools, thereby ensuring their feasibility and relevance in clinical practice.

This publication may serve as a first step toward the evolution of the Spanish health care system, enabling a more comprehensive approach to CKM patients across all medical specialties. Translating these statements into practical, everyday recommendations for all specialists would be a feasible and highly useful action to ensure the implementation, in an easy way, of at least some of these considerations. In addition, CKM initiatives should be promoted in the most favorable health care environments, and these good practices should be shared in common forums, encouraging their extrapolation to other similar realities and advocating for patient equity.

In addition to the inherent features of expert consensus, our study has other limitations. The selection criteria for the panel of experts aimed to choose leading medical professionals who have deep knowledge about CKM syndrome. Additionally, they represent the reality of Spanish doctors, both in their geographical diversity and in their medical specialties or career paths as health care professionals; nevertheless, personal bias of the panelists, inherent to Delphi methodology, must be considered. We do not provide specific recommendations for many of the issues related to the management of each CKM condition because it was beyond the scope of this consensus. Instead, we recommend relying on available guidelines or recommendation documents. However, CKM syndrome is complex, and the assimilation of all guidelines is complex. Therefore, integrated or unified guidelines are needed to facilitate the management of these patients [26,49]. An effort in this direction has been made by a US and European group of multispecialty experts who have assembled a set of detailed recommendations for the comprehensive management of patients with CKM syndrome [50], although its high degree of complexity may make its practical implementation difficult for many physicians. We did not address the essential issue of adverse social determinants of health that, independent of demographic and lifestyle factors, are associated with multimorbidity [51] and mortality [52] in these individuals. Finally, this consensus focuses on applicability within our health care setting, with universal health care coverage and a specific health care organization in mind. While we believe that most recommendations are applicable to other geographical or health care settings, some, particularly those related to organization, may not be applicable or would require adaptation to specific health care contexts.

We believe that this consensus has two important strengths, namely, its multidisciplinary nature and the fact that we have tried to offer a practical framework to guide clinicians in the management of CKM syndrome, transitioning from a conceptual perspective to a clinically operable entity, and thus providing specific recommendations.

In conclusion, diagnosing and treating CKM syndrome remains a clinical challenge. This Delphi consensus offers multidisciplinary recommendations highlighting the importance of early recognition, integrated management, and the implementation of preventive and therapeutic strategies with established cardiorenal and metabolic benefits. These statements complement existing guidelines by providing expert consensus that may inform more coordinated models of care. Furthermore, they help medical managers, clinical experts and other decision-makers in being more innovative and launching new programs to address CKM conditions in a more comprehensive way. Taken together, these findings represent important first steps toward mitigating the burden of CKM syndrome and promoting more integrated approaches to care. The growing understanding of the connections between these major organ systems and the rapidly evolving evidence supporting the adoption of the CKM syndrome, its integrative management, the benefits of recommended treatments for CKM conditions, and the implementation of optimized care models mandate periodic updates of this consensus.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14248930/s1, Table S1: professional characteristics of the panelists.

Author Contributions

D.O.-B., X.T., R.d.H.: Conceptualization, supervision. All authors: methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Alliance Boehringer Ingelheim–Lilly. The authors did not receive payment related to the development of the manuscript. Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly were given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethic approval is waived because it did not involve research on humans. Instead, it is a set of expert recommendations obtained following a systematic approach (i.e., a Delphi study).Even if this study is considered an observational study, according to our regulations (Real Decreto 957/2020, de 3 de noviembre, por el que se regulan los estudios observacionales con medicamentos de uso humano/ Royal Decree 957/2020, of November 3), available at https://boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2020-14960. Accessed on 18 November 2025) which regulates observational studies with medicinal products for human use) it does not require to be review and approved by an Ethics Committee because it is not a clinical study, that is, a research that involves the collection of individual data relating to the health of people.

Informed Consent Statement

All health care professionals who participated in the Delphi survey were informed of the nature of the project and agreed to participate by signing a contract.

Data Availability Statement

All the data pertaining to this project are presented in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ampersand Consulting (Barcelona, Spain) and Fernando Rico-Villademoros of COCIENTE S.L. (Madrid, Spain) for providing writing and editorial support, which was contracted and funded by the Alliance Boehringer Ingelheim–Lilly. We thank all participants in the consensus (in alphabetical order): María del Pilar Alonso Alvarez, Juan Luis Alonso Jerez, Escarlata Angullo Martínez, Ezequiel Arranz Martínez, Beatriz Aviles Bueno, Maria D. Ballesteros-Pomar, José Jesús Broseta Monzó, Enrique Carretero Anibarro, Marta Casañas Martínez, Itziar Castaño Bilbao, Helga Maria Castillo Bueno, Ana Chico, Gabriel Cuatrecasas Cambra, Tomas de Vega Santos, Sara del Amo Ramos, B Vanessa Déniz Saavedra, Mar Domingo Teixidor, Vanessa Escolar Pérez, María José Espigares Huete, Antonio Espino Montoro, Luis Aaron Falcon Espinola, Gema Fernández Fresnedo, Aisa Fornovi Justo, M. Isabel Gabaldón Sánchez, Isabel Galán Carrillo, Antonio Luis Gámez López, Rafael Garcia Maset, Antonio Garcia Quintana, Francisco Javier Garcia Soidan, Vicente Giner Galvañ, David González Calle, Jose Yussel González Galván, Ignacio González Lillo, Juan Górriz Magaña, Juan Jose Jiménez Aguilella, Lucía Jorge Huerta, Pedro Jesus Labrador Gomez, Beatriz Lardiés Sánchez, Miguel Angel María Tablado, Manuel Martín López, Ana Martínez García, Virgilio Martínez Mateo, Ángel Carlos Matía Cubillo, Ana Belén Méndez Fernández, Andrea Mendizabal Nuñez, Esther Montero Hernández, José Luis Morales Rull, Soraya Muñoz Troyano, Diego Murillo Garcia, Carlos Narváez Mejía, Jonay Pantoja Perez, Francisco Javier Peñafiel Martínez, Jaime Nevado Portero, Francesc Puchades Gimeno, Adriana Puente Garcia, Carlos Puig Jové, Irene Rilo Miranda, Carolina Robles Gamboa, Jorge Rubio Gracia, Francisco Manuel Salmerón Martínez, Carlos Sánchez Juan, Fernando Javier Sánchez Lora, María Sanz Almazán, Beatriz Seoane Gonzalez, Maria Fernanda Slon Roblero, Lucía Sobrino Díaz, Santiago Tofé Povedano, Miguel Turégano Yedro, Estibaliz Ugarte Abasolo, and Rocío Villar Taibo.

Conflicts of Interest

D.O.-B. has received funding for medical training, lectures and basic research from the following pharmaceutical companies: Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Deskcom and Sanofi. B.Q. reports honoraria for conferences, consulting fees and advisory boards from Bayer, Novo Nordisk, Genzyme–Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Boehringer and CSL–Vifor. A.E.-F. has received funding for medical training, presentations and basic research from the following pharmaceutical companies: AstraZeneca, Boehringer–Lilly, Novartis and Bayer. A.L.A. has received funding for medical training, lectures and basic research from the following pharmaceutical companies: AstraZeneca, Boehringer–Lilly, Novartis, Bayer, Abbott and Sanofi. V.B. has received funding for medical training, presentations and basic research from the following pharmaceutical companies: Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Esteve, Lilly, MSD, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. T.B.P.d.I. has received funding for medical training, presentations and basic research from the following pharmaceutical companies: FAES, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Esteve, Lilly, MSD and Novo Nordisk. R.d.H. is a full-time employee of Boehringer Ingelheim. X.T. is full-time employee of Eli Lilly and Company. J.C.R.-V. has received speaking fees, consulting fees or scientific collaborations from Bayer, BMS, Boehringer, Lilly, Pfizer, Almirall, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Bial, Novo Nordisk, MSD, Organon, Daiichi Sankyo, and GlaxoSmithKline.

References

- Ndumele, C.E.; Rangaswami, J.; Chow, S.L.; Neeland, I.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Khan, S.S.; Coresh, J.; Mathew, R.O.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; et al. Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic health: A presidential advisory from the American heart association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1606–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.E.; Joo, J.; Kuku, K.O.; Downie, C.; Hashemian, M.; Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Shearer, J.J.; Roger, V.L. Prevalence, disparities, and mortality of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome in US adults, 2011–2018. Am. J. Med. 2025, 138, 970–979.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, R.; Wang, R.; He, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Niu, X.; Sun, Y.; Guan, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, L.; et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stages by social determinants of health. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2445309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.; Sabanayagam, C.; Matsushita, K.; Cheng, C.Y.; Rim, T.H.; Sheng, B.; Li, H.; Tham, Y.C.; Cheng, S.; Wong, T.Y. Sex differences in cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome: 30-year us trends and mortality risks-brief report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2025, 45, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, A.M.K.; Mathew, R.O.; Sperling, L.S.; Nambi, V.; Virani, S.S.; Navaneethan, S.D.; Shapiro, M.D.; Abramov, D. Prevalence of the cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome in the United States. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 83, 1824–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinand, K.C.; Norris, K.C.; Rodbard, H.W.; Trujillo, J.M. Humanistic and economic burden of patients with cardiorenal metabolic conditions: A systematic review. Diabetes Ther. 2023, 14, 1979–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, G.A.; Amitay, E.L.; Chatterjee, S.; Steubl, D. Health care costs associated with the development and combination of cardio-renal-metabolic diseases. Kidney360 2023, 4, 1382–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudel, S.E.; Schmidt, I.M.; Waikar, S.S.; Verma, A. Cumulative incidence of mortality associated with cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2025, 36, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, N.; Weiner, D.; Sarnak, M. Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic health syndrome: What does the American heart association framework mean for nephrology? J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2024, 35, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Tan, G.; Tang, S.C.W.; Ng, Y.W.; Lee, M.K.Y.; Chan, J.W.M.; Chan, T.M. Incorporating the cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic health framework into the local healthcare system: A position statement from the Hong Kong College of Physicians. Hong Kong Med. J. 2025, 31, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Hunter, D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. Br. Med. J. 1995, 311, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Z. Use of Delphi in health sciences research: A narrative review. Medicine 2023, 102, e32829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasa, P.; Jain, R.; Juneja, D. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: How to decide its appropriateness. World J. Methodol. 2021, 11, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorriz, J.L.; Gil, F.A.; Lopez, M.A.B.; Soto, A.B.; Cabrera, F.J.C.; Cisneros, A.; Guerrero, S.C.; Conejos, M.D.; Cabello, I.E.; Planelles, M.C.F.; et al. Improvement in the detection, diagnosis, and early treatment of chronic kidney disease in Spain. The IntERKit project. Nefrologia (Engl. Ed.) 2025, 45, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeland, I.J.; Al-Kindi, S.G.; Tashtish, N.; Eaton, E.; Friswold, J.; Rahmani, S.; White-Solaru, K.T.; Rashid, I.; Berg, D.; Rana, M.; et al. Lessons learned from a patient-centered, team-based intervention for patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk: Year 1 results from the CINEMA program. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e024482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, N.A.; Berchtold, P.; Ullman, K.; Busato, A.; Egger, M. Integrated care programmes for adults with chronic conditions: A meta-review. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2014, 26, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo-Prat, D.; Sainz, L.; Laiz, A.; De Dios, A.; Fontcuberta, L.; Fernández, S.; Masip, M.; Riera, P.; Pagès-Puigdemont, N.; Ros, S.; et al. Designing an integrated care pathway for spondyloarthritis: A Lean Thinking approach. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2025, 31, e14132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.; Cobo, M.; Lopez-Sanchez, P.; Garcia-Magallon, B.; Salazar, M.L.S.; Lopez-Ibor, J.V.; Janeiro, D.; Garcia, E.; Briales, P.S.; Montero, E.; et al. Multidisciplinary approach to patients with heart failure and kidney disease: Preliminary experience of an integrated cardiorenal unit. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, 2100–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamez, M.A.; Palomas, J.L.B.; Mayoral, A.R.; Manzanares, R.G.; Garcia, J.M.; Rodriguez, N.R.; Somoza, F.J.E.; Fillat, A.C.; Padial, L.R.; Sanchez, M.A. Outcomes of patients with heart failure followed in units accredited by the SEC-Excelente-IC quality program according to the type of unit. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2025, 78, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Beltran, D.; Cos-Claramunt, F.X. Primary care diabetes in Spain. Prim. Care Diabetes 2008, 2, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciciurkaite, G.; Moloney, M.E.; Brown, R.L. The incomplete medicalization of obesity: Physician office visits, diagnoses, and treatments, 1996–2014. Public Health Rep. 2019, 134, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, R.; Abraham, M.; Childs, W.; Le, K.; Velez, C.; Vaughn, I.; Lamerato, L.; Budzynska, K. Factors associated with receiving an obesity diagnosis and obesity-related treatment for patients with obesity class II and III within a single integrated health system. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 46, 102879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Cai, J.; Xu, H.; Xiao, X.; Zhao, X. Lifestyle factors and their relative contributions to longitudinal progression of cardio-renal-metabolic multimorbidity: A prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Ahn, S.B.; Shin, J.H.; Lim, Y.H. Hepatic steatosis in cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome: Fatty liver index as a predictor of cardiovascular outcomes. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, zwaf396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Fouque, D. The foundation and the four pillars of treatment for cardiorenal protection in people with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunwald, E. From cardiorenal to cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 682–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zannad, F.; Sanyal, A.J.; Butler, J.; Miller, V.; Harrison, S.A. Integrating liver endpoints in clinical trials of cardiovascular and kidney disease. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2423–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, K.B.; Iskarous, K.; Sankaranarayanan, R. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors across the spectrum of cardiovascular kidney metabolic syndrome. Cardiol. Clin. 2025, 43, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Mauvecin, J.; Villar-Gomez, N.; Mino-Izquierdo, L.; Povo-Retana, A.; Ramos, A.M.; Ruiz-Hurtado, G.; Sanchez-Nino, M.D.; Ortiz, A.; Sanz, A.B. Antioxidant effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Peterson, E.; Pagidipati, N. Barriers to prescribing glucose-lowering therapies with cardiometabolic benefits. Am. Heart J. 2020, 224, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Li, T.; Mandelbrot, D.; Astor, B.C.; Mehr, A.P. Prescribing patterns for sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: A survey of nephrologists. Kidney Int. Rep. 2023, 8, 1669–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, A.F.; Ko, D.T.; Chong, A.; Fang, J.; Atzema, C.L.; Austin, P.C.; Stukel, T.A.; Tu, K.; Udell, J.A.; Naimark, D.; et al. Prescribing patterns and factors associated with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor prescribing in patients with diabetes mellitus and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. CMAJ Open 2023, 11, E494–E503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.S.; Leite, A.R.; Marcelino, M.; Melo, M.; Freitas, P.; Ramalho, C.; Calcada, E. Trends in antidiabetic drug use in Portugal: 8 years real-world data from a nationwide retrospective observational study (2017–2024) (TREND-8 study). Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 4022–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Fernandez, A.; Gomez-Otero, I.; Lopez-Fernandez, S.; Santamarta, M.R.; Pastor-Perez, F.J.; Fluvia-Brugues, P.; Perez-Rivera, J.A.; Lopez, A.L.; Garcia-Pinilla, J.M.; Palomas, J.L.B.; et al. Influence of the medical treatment schedule in new diagnoses patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2024, 113, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckel, R.H.; Blaha, M.J. Cardiometabolic Medicine: A Call for a New Subspeciality Training Track in Internal Medicine. Am. J. Med. 2019, 132, 788–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro Michael, D.; Maron David, J.; Morris Pamela, B.; Kosiborod, M.; Sandesara Pratik, B.; Virani Salim, S.; Khera, A.; Ballantyne Christie, M.; Baum Seth, J.; Sperling Laurence, S.; et al. Preventive Cardiology as a Subspecialty of Cardiovascular Medicine. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1926–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangaswami, J.; Tuttle, K.; Vaduganathan, M. Cardio-Renal-Metabolic Care Models. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2020, 13, e007264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, S.J.; Fonarow, G.C.; Butler, J. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors for heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction: Time to deliver implementation. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 1902–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Fernandez, B.; Gorriz, J.L.; Cebrian-Cuenca, A.; Fácila, L.; Fernandez Rodriguez, J.M.; Maraver, M.P.; Ortiz, A. From Evidence to Action: Advancing Timely Implementation of Triple Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and CKD. Kidney Int. Rep. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCORE2 working group and ESC Cardiovascular risk collaboration. SCORE2 risk prediction algorithms: New models to estimate 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease in Europe. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 2439–2454. [CrossRef]

- SCORE2-OP working group and ESC Cardiovascular risk collaboration. SCORE2-OP risk prediction algorithms: Estimating incident cardiovascular event risk in older persons in four geographical risk regions. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 2455–2467. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SCORE2-Diabetes Working Group and the ESC Cardiovascular Risk Collaboration. SCORE2-Diabetes: 10-year cardiovascular risk estimation in type 2 diabetes in Europe. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 2544–2556. [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, K.; Kaptoge, S.; Hageman, S.H.J.; Sang, Y.; Ballew, S.H.; Grams, M.E.; Surapaneni, A.; Sun, L.; Arnlov, J.; Bozic, M.; et al. Including measures of chronic kidney disease to improve cardiovascular risk prediction by SCORE2 and SCORE2-OP. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2023, 30, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.S.; Coresh, J.; Pencina, M.J.; Ndumele, C.E.; Rangaswami, J.; Chow, S.L.; Palaniappan, L.P.; Sperling, L.S.; Virani, S.S.; Ho, J.E.; et al. Novel Prediction Equations for Absolute Risk Assessment of Total Cardiovascular Disease Incorporating Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1982–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, P.; Fan, F.; Hao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Z.; Deng, X.; Deng, Q.; Hao, Y.; Yang, N.; et al. A simple score, CKM(2)S(2)-BAG, to predict cardiovascular risk with cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic health metrics. iScience 2025, 28, 112780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Gómez, H.J.; García-Foncillas López, R. Cross-Sectional Study of Attendance at a Primary Care Consultation in a Social Security Health System. Fam. Med. Prim. Care Open Access 2025, 9, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilabert, M.; Sanchez-Garcia, A.; Asencio, A.; Marrades, F.; Garcia, M.; Mira, J.J.; Dafo, C. Challenges and strategies to recover and dynamize primary care: SWOT-CAME analysis in a health department. Aten. Primaria 2024, 56, 102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vara-Ortiz, M.A.; Marcos-Alonso, S.; Fabrellas-Padres, N. Experience of primary care nurses applying nurse-led management of patients with acute minor illnesses. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2024, 30, e13216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.P.; Zannad, F. We need simpler and more integrated guidelines in cardio-kidney-metabolic diseases. JACC Heart Fail. 2025, 13, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelsman, Y.; Anderson, J.E.; Bakris, G.L.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Bloomgarden, Z.T.; Bozkurt, B.; Budoff, M.J.; Butler, J.; Cherney, D.Z.I.; et al. DCRM 2.0: Multispecialty practice recommendations for the management of diabetes, cardiorenal, and metabolic diseases. Metabolism 2024, 159, 155931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Lei, L.; Wang, W.; Ding, W.; Yu, Y.; Pu, B.; Peng, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Y. Social risk profile and cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome in US adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e034996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotton, A.; Salerno, P.R.; Deo, S.V.; Virani, S.S.; Nasir, K.; Neeland, I.; Rajagopalan, S.; Sattar, N.; Al-Kindi, S.; Elgudin, Y.E. The association between county-level social determinants of health and cardio-kidney-metabolic disease attributed all-cause mortality in the US: A cross sectional analysis. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 369, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).