Abstract

Background: Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) is a useful adjunct for managing oral biofilm diseases. Natural photosensitizers may be safer and more biocompatible than synthetic ones, but their dental effectiveness is still unclear. Methods: A PRISMA compliant review (PROSPERO ID: CRD420251233910) searched PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library for randomized controlled trials published from 2015 to 2025 that used natural photosensitizers for aPDT in dental settings. Three reviewers screened studies, extracted data, and assessed bias with a nine-domain tool adapted for photodynamic therapy. Results: Eleven of 249 records met the established criteria. Natural photosensitizers included curcumin, riboflavin, phycocyanin, chlorophyll derivatives, and plant extracts, tested in periodontitis, peri-implant mucositis, denture stomatitis, caries-related biofilms, and general oral decontamination. Most trials showed short-term microbial reductions and modest clinical gains, with performance comparable to chlorhexidine, methylene blue, or standard care. Adverse effects were minimal. Study quality was generally good, but wide variation in photosensitizer type, light settings, and outcomes, and short follow-up periods hindered meta-analysis and limited conclusions about long-term effectiveness. Conclusions: Natural photosensitizer-based aPDT appears effective and safe as an adjunct, offering consistent short-term microbiological improvements. Current evidence does not support replacing established antimicrobial approaches. Larger, well-controlled trials with standardized methods and longer follow-up periods are needed to define best practice and clarify the role of aPDT in routine dentistry.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The rise of antimicrobial resistance has created major challenges across healthcare, including dentistry, where conventional antimicrobial agents are becoming less effective against biofilm-related oral pathogens [1]. Conditions such as periodontal disease, peri-implantitis, peri-implant mucositis, and other infections driven by complex biofilms often respond unpredictably to mechanical debridement and standard antiseptics, which has increased interest in adjunctive therapies capable of enhancing microbial control [2]. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) has emerged as one such option. It relies on the activation of a photosensitizer by light in the presence of oxygen to generate reactive oxygen species that selectively damage microbial cells while leaving host tissues largely unaffected [3]. This targeted mode of action makes aPDT particularly suitable for managing biofilms that are otherwise difficult to eradicate. Clinical research has historically focused on synthetic photosensitizers, which offer consistent photochemical behavior and potent antimicrobial effects [4]. Increasing attention, however, has turned toward natural photosensitizers derived from plant and microbial sources, driven by concerns regarding cytotoxicity, environmental impact, cost, and the risk of microbial tolerance associated with some synthetic compounds [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Natural agents such as curcumin, chlorophyll derivatives, and riboflavin (vitamin B2) possess advantageous properties, including biocompatibility, biodegradability, low toxicity, and inherent antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, or antioxidant activity [4,6]. Their broader adoption aligns with growing interest in sustainable and patient-friendly therapeutic approaches [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Despite these theoretical and laboratory supported advantages, the clinical integration of natural photosensitizers remains limited. Many natural compounds have variable photochemical characteristics and issues related to solubility, stability, and bioavailability that can compromise clinical performance [6,7]. Advances in pharmaceutical formulations and nanocarrier-based delivery systems have begun to address these limitations, yet these innovations require confirmation through well-designed clinical trials [7]. There is also no consensus on optimal treatment parameters, including photosensitizer concentration, light wavelength, irradiation time, or dosing frequency, which contributes to inconsistent outcomes across studies [5]. This topic has clinical importance because dentistry is increasingly constrained by antimicrobial resistance and by patient demand for safer and more natural adjunctive therapies. Although laboratory findings have been promising, no comprehensive synthesis of contemporary randomized controlled trials has focused specifically on the clinical performance of natural photosensitizers in aPDT. A targeted evaluation of this evidence is needed to clarify its utility, identify knowledge gaps, and support evidence-based decision making.

1.2. Objectives

Given these considerations, a comprehensive systematic review focusing exclusively on randomized controlled trials is warranted to critically evaluate the current evidence regarding the efficacy of natural photosensitizers in antimicrobial photodynamic therapy for dental applications [1,5]. This review seeks to clarify clinical and microbiological outcomes, identify strengths and limitations in the existing literature, and provide informed recommendations to guide future research and facilitate integration of natural photosensitizers into evidence-based dental practice.

2. Methods

This systematic review followed established methodological standards for evidence synthesis and was conducted in accordance with PRISMA 2020 [13]. The protocol was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO database (registration number CRD420251233910) [14].

2.1. Focused Question

In dental patients receiving antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (Population), does the use of natural photosensitizers (Intervention), compared with synthetic photosensitizers or no photodynamic therapy (Comparison), improve clinical or microbiological outcomes related to oral infections (Outcome) [15]? Primary outcomes were quantitative measures of microbial reduction, including bacterial or fungal load and biofilm viability. Secondary outcomes included probing depth, bleeding on probing, clinical attachment level, oral mucositis severity, resolution of denture-related stomatitis, and any reported adverse effects.

2.2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive electronic search was performed across PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library to identify studies evaluating aPDT mediated by natural photosensitizers within dentistry. Three independent reviewers executed searches using predefined combinations of MeSH terms and free-text keywords associated with antimicrobial photodynamic therapy, natural photosensitizers, and dental applications. Searches were limited to English language studies published from 2015 to 2025, with no geographical restrictions. The screening process was performed between July and September 2025. Screening was performed in two phases: first, title and abstract screening to identify potentially eligible records, and second, full-text review based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Reference lists of all included studies were manually screened to identify additional eligible articles. The search aimed to capture clinical, in vitro, and ex vivo research examining the effectiveness of natural photosensitizers used in antimicrobial photodynamic therapy within dental disciplines. The search syntax is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search syntax used in the study.

2.3. Study Selection Process

Study selection was conducted independently by three reviewers. Titles and abstracts were screened according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eligible studies included clinical trials, in vitro studies, ex vivo studies, and comparative research examining antimicrobial photodynamic therapy using natural photosensitizers in dental contexts. Included studies needed to report measurable microbiological or clinical outcomes, such as bacterial load reduction, periodontal pocket improvement, caries-related microbial changes, biofilm disruption, or therapeutic outcomes in endodontics, periodontics, or oral surgery. Exclusion criteria included narrative reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, in vivo animal studies without dental relevance, studies using only synthetic photosensitizers, and publications not available in English. Duplicates were removed, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

2.4. Data Extraction

Three reviewers independently extracted data using a standardized form. Extracted variables included author, year of publication, study design, type of natural photosensitizer used, light source parameters, targeted microorganisms or clinical condition, sample size, outcome measures, and main findings. Microbiological and clinical outcomes were recorded where applicable, including bacterial reduction rates, changes in clinical inflammatory indices, biofilm disruption levels, healing parameters, and follow-up durations. Details regarding photosensitizer preparation, concentration, and activation wavelength were also extracted.

2.5. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

Methodological quality was independently evaluated by three reviewers using an adapted appraisal tool for photodynamic therapy research. The following domains were assessed:

- Clear description of the natural photosensitizer, including preparation and concentration.

- Specification of light source parameters such as wavelength, power density, and irradiation time.

- Measurement of clinically or microbiologically relevant outcomes.

- Inclusion of appropriate comparator groups, such as untreated controls or synthetic photosensitizers.

- Clear inclusion and exclusion criteria for sample selection.

- Consideration of bias control measures including randomization, calibration, or blinding, where applicable.

- Transparency and reproducibility of statistical analysis.

- Completeness of outcome reporting, including adverse effects or limitations.

- Disclosure of funding and potential conflicts of interest.

Each domain received a score of 1 or 0, giving total possible scores of 0 to 9. Studies scoring 7 to 9 were classified as low risk, 4 to 6 as moderate risk, and 0 to 3 as high risk. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by a fourth reviewer. The assessment followed methodological guidance from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [16].

2.6. Assessment of the Quality of Evidence

A structured review of the evidence for each outcome was carried out using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework, which guides the appraisal of research certainty [17]. Evidence was sorted into four levels: high, moderate, low, or very low quality. Because judging GRADE elements can involve interpretation, three authors independently reviewed the criteria. Any differing views were resolved through discussion, supported by calculating agreement with Cohen’s k test.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

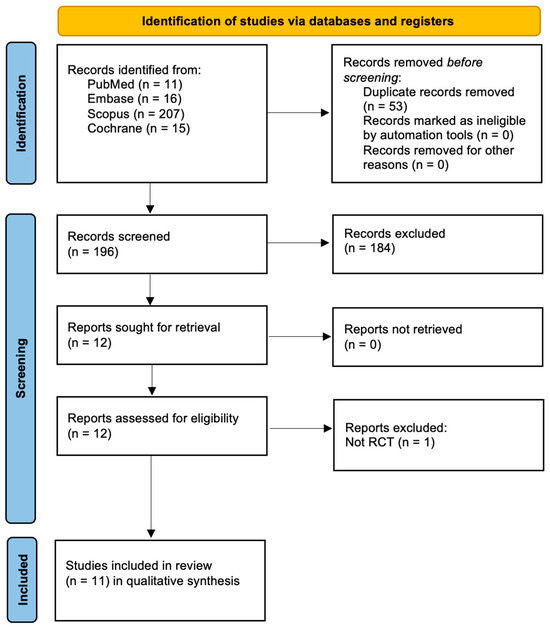

The database search yielded 249 records, including 11 from PubMed, 16 from Embase, 207 from Scopus, and 15 from the Cochrane Library. After removing 53 duplicates, 196 records remained for screening. Title and abstract screening resulted in the exclusion of 184 records, leaving 12 reports for retrieval. All 12 reports were successfully retrieved and assessed for eligibility. One report was excluded for not being a randomized controlled trial, resulting in 11 studies being included in the qualitative synthesis. This is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 Flowchart.

3.2. Assessment of the Risk of Bias

The assessment shows that nearly all included studies demonstrated strong methodological quality, with most scoring eight or nine out of nine items and falling into the low-risk category. Only one study was rated as medium risk. Despite this outlier, the overall evidence base is characterized by consistent low risk ratings, suggesting that the findings drawn from these studies provide a generally reliable and robust set of data. This is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The results of the quality assessment and risk of bias assessment across the studies.

3.3. Assessment of the Quality of Evidence

This summary provides a clearer indication of how confidently the current evidence can be interpreted and is detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of findings (SoFs) and quality of evidence (GRADE).

3.4. Characteristics of the Included Studies

Across the included studies, sample designs varied widely, with research conducted in Iran, Saudi Arabia, and multiple regions of Brazil. Several studies used grouped laboratory or clinical samples such as implants, molars, tooth blocks, or adult participants, while others followed split mouth- or device-based designs. Sample sizes ranged from small controlled groups to larger clinical sets, and in some cases initial enrollment differed from final completion numbers. Overall, the collection of studies reflects broad geographic coverage and heterogeneous methodologies suited to their respective research aims [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] (Table 4).

Table 4.

A general overview of the studies.

3.5. Main Outcomes from Studies

When interpreting the results, outcomes from low-risk studies were prioritized. Findings from trials with moderate risk or incomplete reporting were considered supportive but not definitive. This approach allowed balanced interpretation while acknowledging methodological variability. Across the studies, most interventions using curcumin, riboflavin, toluidine blue, or Photogem combined with light sources produced meaningful antimicrobial or clinical benefits, often outperforming controls. Several investigations showed strong reductions in bacterial or fungal counts with photodynamic approaches, particularly when specific photosensitizers or light parameters were paired effectively [18,21,24,25,26,27]. Some trials demonstrated clinical improvements such as reduced mucositis, pain, periodontal parameters, or Candida levels, with aPDT frequently matching or exceeding conventional treatments like chlorhexidine or nystatin [19,20,23,28]. A number of studies reported specific limitations associated with natural photosensitizers, including reduced bond strength under certain adhesive protocols [22], variable antimicrobial effectiveness depending on photosensitizer–light pairing [18,21,27], and inconsistent persistence of clinical improvements [24,28]. Despite these shortcomings, the overall evidence supports the antimicrobial and therapeutic potential of light-based therapies when appropriate parameters are selected. Patient acceptance and user experience were not consistently assessed across the included trials. The limited available information indicates minimal discomfort and few adverse effects, yet key aspects such as taste, staining potential, ease of application, and overall satisfaction have not been systematically evaluated. Future studies should incorporate structured patient-reported measures to better characterize usability and acceptability.

Across the included trials, natural photosensitizers demonstrated meaningful antimicrobial or clinical effects across diverse dental applications. Afrasiabi et al. [18] showed that all tested photosensitizer–light combinations significantly reduced A. actinomycetemcomitans on implant surfaces, with LED-mediated aPDT producing the lowest CFU counts. In restorative dentistry, AlSunbul et al. [19] found that methylene blue-mediated aPDT achieved the highest bonding values and strongest antibacterial activity, while curcumin-mediated aPDT produced the greatest long-term 4-point bending strength. In the management of oral mucositis, de Cássia Dias Viana Andrade et al. [20] reported that both photobiomodulation- and curcumin-based aPDT reduced Candida levels and improved symptoms, with aPDT showing earlier clinical benefit. Donato et al. [21] demonstrated immediate microbial reductions with curcumin and Photogem, though only curcumin sustained the effect at 24 h. Hashemikamangar et al. [22] showed that aPDT did not impair bonding in self-etch protocols, with phycocyanin producing the highest bond strength. In periodontitis, Ivanaga et al. [23] found that all groups improved over time, though clinical attachment gain occurred only in the LED and aPDT groups at three months. Labban et al. [24] showed that curcumin- and rose bengal-mediated aPDT achieved antifungal effects comparable to nystatin in smokers with denture stomatitis. Leite et al. [25] observed significant short-term reductions in salivary CFU following curcumin-based aPDT compared with light alone or curcumin alone. Panhóca et al. [26] demonstrated enhanced antimicrobial activity when surfactant was added to curcumin-mediated aPDT, performing similarly to chlorhexidine. A related in situ study by Panhóca et al. [27] confirmed that curcumin-mediated aPDT reduced S. mutans biofilm, though Photogem produced the largest reduction. Paschoal et al. [28] reported that curcumin-mediated c PACT reduced gingival bleeding at one month but did not improve plaque levels compared with chlorhexidine varnish or placebo (Table 5 and Table 6).

Table 5.

Main outcomes and details from each study.

Table 6.

Physical parameters of light sources.

4. Discussion

4.1. Results in the Context of Other Evidence

Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) in dentistry utilizes photosensitizers activated by light to generate reactive oxygen species, leading to microbial cell death. Natural photosensitizers such as curcumin, riboflavin, phycocyanin, chlorophyll derivatives, and certain plant extracts have demonstrated significant antimicrobial efficacy against oral pathogens, including those in biofilms associated with periodontitis, peri-implantitis, and denture-related infections [29,30,31,32,33]. In vitro and clinical studies show that natural photosensitizers, when combined with appropriate light sources such as LED or blue light, can reduce bacterial and fungal colony counts and disrupt biofilm structure. Curcumin and riboflavin have shown antimicrobial effects comparable to conventional disinfectants in peri-implantitis and denture biofilm models, though complete biofilm eradication is rarely achieved [32,33,34]. Advantages of natural photosensitizers include low toxicity, biocompatibility, and environmental sustainability. However, limitations such as poor solubility and bioavailability persist, prompting ongoing research into nanocarrier-based delivery systems to enhance clinical effectiveness [31,35]. Despite promising results, heterogeneity in protocols and insufficient long-term clinical data prevent standardized recommendations. Additional high-quality randomized controlled trials are needed to establish optimal dosing, irradiation parameters, and long-term outcomes [32,36]. Natural photosensitizers are effective adjuncts in aPDT for dental infections, offering antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activity with favorable safety profiles, but require further translational research before routine clinical adoption [1,6,36,37,38,39]. Current evidence from randomized controlled trials comparing natural photosensitizers with conventional agents in aPDT indicates that natural agents such as curcumin, riboflavin, and 5 aminolevulinic acid are effective adjuncts for reducing microbial load and improving clinical indices in periodontal and peri-implant diseases, but their long-term efficacy and superiority over conventional agents remain unproven due to methodological heterogeneity and limited follow-up data [7,30,31]. In peri-implantitis, systematic reviews of randomized trials show that natural photosensitizers achieve reductions in bacterial viability, probing depth, and bleeding on probing comparable to conventional agents such as toluidine blue, though complete biofilm eradication is rarely achieved. Curcumin and riboflavin demonstrate similar short-term clinical improvements, but toluidine blue remains the most effective for sustained outcomes based on meta-analyses [30,31]. Most studies report favorable safety profiles and minimal adverse effects for natural agents [30]. For periodontitis, adjunctive aPDT, regardless of photosensitizer type, provides modest improvements in probing depth and clinical attachment level at six months. These changes are not consistently clinically significant, and the certainty of the evidence is very low due to risk of bias and small sample sizes [37]. Long-term data beyond six months are sparse, and standardized protocols for natural photosensitizers are lacking [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Natural photosensitizers are effective adjuncts in aPDT for short-term microbial and clinical improvements, but they do not outperform conventional agents in long-term efficacy. Further large-scale, well designed randomized controlled trials with standardized protocols and extended follow-up periods are needed to establish aPDT’s role in routine dental practice [30,31,37].

4.2. Limitations of the Evidence

Although the included trials indicate that natural photosensitizers can reduce microbial load and yield short-term clinical improvements, several limitations weaken the overall certainty of the evidence. Protocols differed markedly across studies, including variations in photosensitizer type, concentration, solvent, light wavelength, power, and irradiation time. Reporting of dosimetry was often incomplete, which limited reproducibility and prevented direct comparison or pooled analysis. Most trials involved small samples, often below thirty participants or test units per group, reducing statistical power and increasing the likelihood of type two errors. Follow-up periods were generally short, with few studies extending beyond three months, so the durability of clinical or microbiological benefits remain unclear. Comparator groups also varied widely, ranging from synthetic photosensitizers to chlorhexidine or no adjunctive treatment, complicating assessment of relative effectiveness. Safety reporting was inconsistent. Many studies did not document adverse effects, staining, or patient acceptability, leaving the full risk profile of natural photosensitizers uncertain. Methodological details were incompletely described in several trials, including randomization and examiner calibration, adding further uncertainty. Finally, many microbial assessments relied on simplified models rather than complex multispecies biofilms, limiting insight into the ecological impact of treatment. These constraints collectively restrict the strength, generalizability, and long-term implications of the current evidence base.

4.3. Limitations of the Review Process

Although this review followed PRISMA guidelines and a comprehensive search strategy across four major databases was implemented, the review process itself presents limitations that should be acknowledged. Restricting searches to English language publications may have led to the exclusion of eligible non-English trials. The decision to limit the time frame from 2015 to 2025 ensured contemporary relevance but may have excluded earlier foundational RCTs on natural photosensitizers. Study selection and data extraction were performed independently by three reviewers, yet the interpretation of incomplete reporting within some primary studies could have introduced subjective judgment. While efforts were made to minimize selection bias, grey literature, unpublished trials, and non-indexed studies may have been missed. A pooled quantitative analysis was not possible due to substantial variation in study design, intervention protocols, and outcome metrics. These factors prevented generation of a common effect size and restricted synthesis to a qualitative approach. Another limitation arises from incomplete information within several primary trials. Missing data on irradiation parameters, photosensitizer preparation, and baseline microbial characteristics limited the precision of extraction and reduced the ability to fully assess methodological rigor. Despite the use of a structured quality assessment tool, variability in study design made uniform scoring challenging. Finally, although the review aimed to distinguish between clinical, in situ, and laboratory conditions, the overlap between these categories in some experimental designs may have affected the consistency of classification.

4.4. Implications for Practice, Policy, and Future Research

The current body of evidence suggests that natural photosensitizers have promising antimicrobial activity and may serve as useful adjuncts in periodontal therapy, peri-implant care, endodontic disinfection, and management of denture-associated infections. Curcumin, riboflavin, and chlorophyll derivatives are among the most studied agents and have demonstrated reductions in microbial viability and modest improvements in clinical indices. While these findings support their potential incorporation into clinical workflows, the absence of standardized dosing protocols and the limited availability of commercial formulations adapted for dental use restrict immediate widespread adoption. For clinical practice, natural photosensitizers may be considered in selected cases as adjunctive agents, particularly when patients prefer natural compounds or when conventional antiseptics are contraindicated. However, practitioners should be cautious due to variability in treatment parameters and the limited evidence for long-term outcomes. Current data do not support replacing synthetic photosensitizers or established antimicrobials with natural alternatives.

From a policy standpoint, regulatory bodies may need to develop guidelines that encourage consistent reporting of photophysical parameters and manufacturing standards for natural photosensitizers. More robust regulation would support safer translation of these agents into clinical products and foster industry research into optimized formulations. Future research should prioritize large-scale randomized controlled trials with standardized photosensitizer concentrations, irradiation protocols, and clinically relevant outcomes. Trials should include follow-up periods beyond six months to determine the durability of microbiological and clinical benefits. Research into novel formulations, especially nanocarrier-assisted systems, may help improve solubility and tissue penetration. Comparative trials between natural and synthetic photosensitizers, as well as cost-effectiveness analyses, will also be essential to define their role in routine practice. Improved reporting of adverse effects, staining potential, patient acceptability, and operator handling characteristics will further enhance clinical relevance.

The choice of natural photosensitizer can be adjusted to the characteristics of the oral infection and the nature of the biofilm. Curcumin has broad antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity and is effective against superficial biofilms due to its strong absorption in the blue spectrum and rapid photoreactivity, making it suitable for periodontal and caries-related applications [4,30,32]. Riboflavin functions well in moist oral environments and demonstrates reliable activation with blue light, which supports its use in peri-implant mucositis and other situations requiring consistent penetration through biofilm matrices [30,31]. Chlorophyll derivatives and phycocyanin absorb strongly in the red range, providing deeper tissue penetration and potential advantages for thicker or more mature biofilms often associated with peri-implantitis and denture-related infections [4,33]. These differences suggest that photosensitizer choice may be optimized by considering microbial composition, lesion depth, and the optical properties of the target site. Future trials should directly compare natural agents across specific clinical scenarios to determine infection-specific selection strategies.

5. Conclusions

This review shows that natural photosensitizers such as curcumin, riboflavin, phycocyanin, and chlorophyll derivatives can provide short-term microbial reduction and modest clinical improvements across various dental conditions. Their safety profile appears favorable, but evidence remains limited by heterogeneous protocols, small sample sizes, incomplete reporting of dosimetry, and short follow-up periods. Natural photosensitizers can currently be considered useful adjuncts but not substitutes for established antimicrobial strategies. Further well-designed randomized trials with standardized interventions and longer follow-up periods are needed to clarify their long-term effectiveness and define their role in routine dental care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F.-R., M.M. and R.W.; methodology, D.T. and M.M.; software, D.T. and J.F.-R.; formal analysis, J.F.-R. and D.T.; investigation, J.F.-R. and D.T.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.-R., D.T., D.S. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, J.F.-R., D.T., R.W., D.S. and M.M.; supervision, R.W., D.S. and M.M.; funding acquisition, R.W. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gholami, L.; Shahabi, S.; Jazaeri, M.; Hadilou, M.; Fekrazad, R. Clinical Applications of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy in Dentistry. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1020995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourbour, S.; Darbandi, A.; Bostanghadiri, N.; Ghanavati, R.; Taheri, B.; Bahador, A. Effects of Antimicrobial Photosensitizers of Photodynamic Therapy to Treat Periodontitis. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2024, 25, 1209–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieplik, F.; Tabenski, L.; Buchalla, W.; Maisch, T. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy for Inactivation of Biofilms Formed by Oral Key Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabi, S.; Partoazar, A.; Chiniforush, N.; Goudarzi, R. The Potential Application of Natural Photosensitizers Used in Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Against Oral Infections. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warakomska, A.; Fiegler Rudol, J.; Kubizna, M.; Skaba, D.; Wiench, R. The Role of Photodynamic Therapy Mediated by Natural Photosensitisers in the Management of Peri-Implantitis: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendola, G.; Di Luca, M.; Sgarbossa, A. Natural Biomolecules and Light. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Strategies in the Fight Against Antibiotic Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, N.; Ranjbar, A.; Shahabi, S.; Afrasiabi, S. Nanocarrier Based Drug Delivery Systems to Enhance Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy in Dental Applications: A Review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2025, 26, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.L.; Hamblin, M.R.; Andrade, S.A. What Is the Potential of Antibacterial, Antiviral and Antifungal Photodynamic Therapy in Dentistry? Evid. Based Dent. 2024, 25, 186–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiniforush, N.; Pourhajibagher, M.; Shahabi, S.; Kosarieh, E.; Bahador, A. Can Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Enhance the Endodontic Treatment? J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 7, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.B.; Ferrisse, T.M.; França, G.G.; de Annunzio, S.R.; Kopp, W.; Fontana, C.R.; Brighenti, F.L. Potential Use of Brazilian Green Propolis Extracts as New Photosensitizers for Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Against Cariogenic Microorganisms. Pathogens 2023, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhajibagher, M.; Plotino, G.; Chiniforush, N.; Bahador, A. Dual Wavelength Irradiation Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Using Indocyanine Green and Metformin Doped with Nano-Curcumin as an Efficient Adjunctive Endodontic Treatment Modality. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 29, 101628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Zięba, N.; Turski, R.; Misiołek, M.; Wiench, R. Hypericin-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy for Head and Neck Cancers: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiavo, J.H. PROSPERO: An International Register of Systematic Review Protocols. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 2019, 38, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO Framework to Improve Searching PubMed for Clinical Questions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 6.5; Cochrane: London, UK, 2024; Available online: www.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An Emerging Consensus on Rating Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabi, S.; Barikani, H.R.; Chiniforush, N. Comparison of Bacterial Disinfection Efficacy Using Blue and Red Lights on Dental Implants Contaminated with Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 40, 103178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSunbul, H.; Murriky, A. Efficacy of Methylene Blue and Curcumin Mediated Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy in the Treatment of Indirect Pulp Capping in Permanent Molar Teeth. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 42, 103598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cássia Dias Viana Andrade, R.; Azevedo Reis, T.; Rosa, L.P.; de Oliveira Santos, G.P.; da Cristina Silva, F. Comparative Randomized Trial Study About the Efficacy of Photobiomodulation and Curcumin Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy as a Coadjuvant Treatment of Oral Mucositis in Oncologic Patients. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 7365–7371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, H.A.; Pratavieira, S.; Grecco, C.; Brugnera-Júnior, A.; Bagnato, V.S.; Kurachi, C. Clinical Comparison of Two Photosensitizers for Oral Cavity Decontamination. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2017, 35, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemikamangar, S.S.; Alsaedi, R.J.F.; Chiniforush, N.; Motevaselian, F. Effect of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy with Different Photosensitizers and Adhesion Protocol on the Bond Strength of Resin Composite to Sound Dentin. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 4011–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanaga, C.A.; Miessi, D.M.J.; Nuernberg, M.A.A.; Claudio, M.M.; Garcia, V.G.; Theodoro, L.H. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy with Curcumin and LED as an Enhancement to Scaling and Root Planing in the Treatment of Residual Pockets in Diabetic Patients. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 27, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labban, N.; Taweel, S.M.A.; ALRabiah, M.A.; Alfouzan, A.F.; Alshiddi, I.F.; Assery, M.K. Efficacy of Rose Bengal and Curcumin Mediated Photodynamic Therapy for the Treatment of Denture Stomatitis in Patients with Habitual Cigarette Smoking: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 35, 102380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, D.P.; Paolillo, F.R.; Parmesano, T.N.; Fontana, C.R.; Bagnato, V.S. Effects of Photodynamic Therapy with Blue Light and Curcumin as Mouth Rinse for Oral Disinfection: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2014, 32, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panhóca, V.H.; Esteban Florez, F.L.; Corrêa, T.Q.; Paolillo, F.R.; de Souza, C.W.; Bagnato, V.S. Oral Decontamination of Orthodontic Patients Using Photodynamic Therapy Mediated by Blue Light Irradiation and Curcumin Associated with Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2016, 34, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panhóca, V.H.; Florez, F.; de Faria Júnior, N.B.; de Souza Rastelli, A.N.; Tanomaru, J.; Kurachi, C.; Bagnato, V.S. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Against Streptococcus mutans Biofilm In Situ. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2016, 17, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschoal, M.A.; Moura, C.M.; Jeremias, F.; Souza, J.F.; Bagnato, V.S.; Giusti, J.S.M.; Santos-Pinto, L. Longitudinal Effect of Curcumin-Photodynamic Antimicrobial Chemotherapy in Adolescents During Fixed Orthodontic Treatment: A Single Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 2059–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiench, R.; Nowicka, J.; Pajączkowska, M.; Kuropka, P.; Skaba, D.; Kruczek-Kazibudzka, A.; Kuśka-Kiełbratowska, A.; Grzech-Leśniak, K. Influence of Incubation Time on Ortho-Toluidine Blue Mediated Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Directed against Selected Candida Strains—An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Kapłon, K.; Kotucha, K.; Moś, M.; Skaba, D.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A.; Wiench, R. Hypocrellin-Mediated PDT: A Systematic Review of Its Efficacy, Applications, and Outcomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruczek-Kazibudzka, A.; Lipka, B.; Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Tkaczyk, M.; Skaba, D.; Wiench, R. Toluidine Blue and Chlorin-e6 Mediated Photodynamic Therapy in the Treatment of Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi Ardakani, A.; Benedicenti, S.; Solimei, L.; Shahabi, S.; Afrasiabi, S. Reduction of Multi Species Biofilms on an Acrylic Denture Base Model by Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Mediated by Natural Photosensitizers. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikulich, A.V.; Plavskii, V.Y.; Tretyakova, A.I.; Nahorny, R.K.; Sobchuk, A.N.; Dudchik, N.V.; Emeliyanova, O.A.; Zhabrouskaya, A.I.; Plavskaya, L.G.; Ananich, T.S.; et al. Potential of Using Medicinal Plant Extracts as Photosensitizers for Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 2024, 100, 1833–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.T.; Hwang, H.; Son, J.D.; Nguyen, U.T.T.; Park, J.-S.; Kwon, H.C.; Kwon, J.; Kang, K. Natural Photosensitizers from Tripterygium wilfordii and Their Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapeutic Effects in a Caenorhabditis elegans Model. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2021, 218, 112184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Lipka, B.; Kapłon, K.; Moś, M.; Skaba, D.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A.; Wiench, R. Evaluating the Efficacy of Rose Bengal as a Photosensitizer in Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Against Candida albicans: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembicka-Mączka, D.; Kępa, M.; Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, Z.; Matys, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Wiench, R. Evaluation of the Disinfection Efficacy of Er: YAG Laser Light on Single-Species Candida Biofilms—An In Vitro Study. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Ji, Y.; Feng, D.; Shao, R.; Zhang, G.; Lin, S.; Duan, S.; Wu, X. Efficacy of Photodynamic Therapy with Various Photosensitizers for Peri-Implantitis Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jervøe-Storm, P.M.; Bunke, J.; Worthington, H.V.; Needleman, I.; Cosgarea, R.; MacDonald, L.; Walsh, T.; Lewis, S.R.; Jepsen, S. Adjunctive Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy for Treating Periodontal and Peri Implant Diseases. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 7, CD011778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvi, S.; Benedicenti, S.; Sălăgean, T.; Bordea, I.R.; Hanna, R. Effectiveness of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy in the Treatment of Periodontitis: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis of In Vivo Human Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).