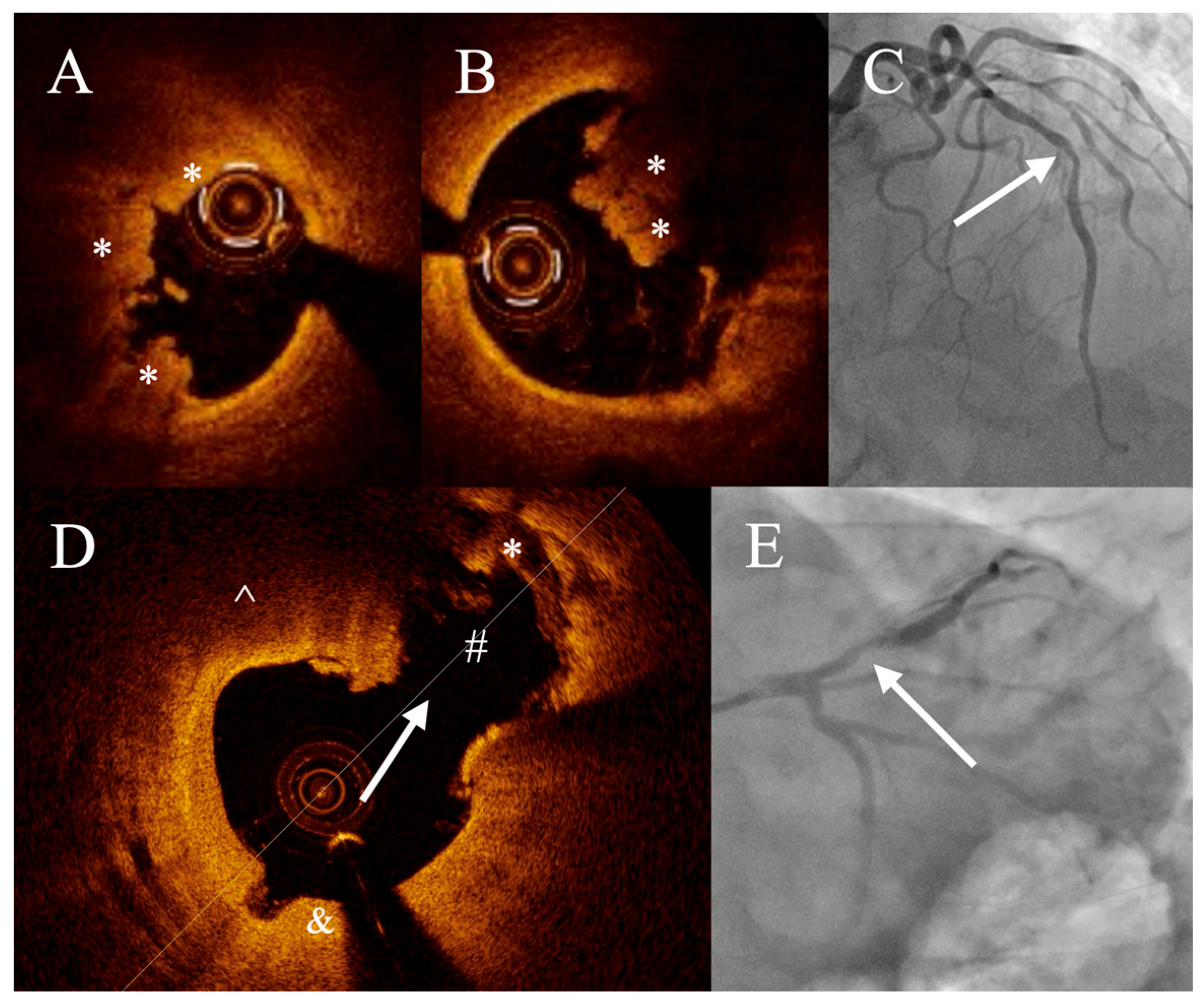

Pathogenesis of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients After COVID-19: An Optical Coherence Tomography Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skonieczna, K.; Wiciun, O.; Pinkowska, K.; Dominiak, T.; Grzelakowska, K.; Kasprzak, M.; Szymański, P.; Kubica, J.; Niezgoda, P. COVID-19-Related Pathologies in Coronary Angiography in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lala, A.; Johnson, K.W.; Januzzi, J.L.; Russak, A.J.; Paranjpe, I.; Richter, F.; Zhao, S.; Somani, S.; Van Vleck, T.; Vaid, A.; et al. Prevalence and Impact of Myocardial Injury in Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 Infection. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzik, T.J.; Mohiddin, S.A.; Dimarco, A.; Patel, V.; Savvatis, K.; Marelli-Berg, F.M.; Madhur, M.S.; Tomaszewski, M.; Maffia, P.; D’Acquisto, F.; et al. COVID-19 and the Cardiovascular System: Implications for Risk Assessment, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 1666–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryniarski, K.; Makowicz, D.; Kleczynski, P.; Nosal, M.; Brzychczy, P.; Mroz, K.; Okarski, M.; Twardosz, J.; Gasior, M.; Legutko, J. Regional Differences in Characteristics of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes Pre- and during Coronavirus-2019 Pandemic. Am. Heart J. Plus Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2025, 60, 100640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavone, M.; Gobbi, C.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Palazzuoli, A.; Gasperetti, A.; Mitacchione, G.; Viecca, M.; Galli, M.; Fedele, F.; et al. Acute Coronary Syndromes and COVID-19: Exploring the Uncertainties. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.-S.; Zhao, L.-X.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.-F.; Liu, F.-C.; Li, H.-P.; He, G.-W.; Zhang, J. The Characteristics of Coronary Artery Lesions in COVID-19 Infected Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: An Optical Coherence Tomography Study. Am. J. Cardiol. 2024, 226, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavli, A.; Theodoridou, M.; Maltezou, H.C. Post-COVID Syndrome: Incidence, Clinical Spectrum, and Challenges for Primary Healthcare Professionals. Arch. Med. Res. 2021, 52, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoularis, I.; Fonseca-Rodríguez, O.; Farrington, P.; Lindmark, K.; Fors Connolly, A.-M. Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction and Ischaemic Stroke Following COVID-19 in Sweden: A Self-Controlled Case Series and Matched Cohort Study. Lancet 2021, 398, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoubkhani, D.; Khunti, K.; Nafilyan, V.; Maddox, T.; Humberstone, B.; Diamond, I.; Banerjee, A. Post-Covid Syndrome in Individuals Admitted to Hospital with COVID-19: Retrospective Cohort Study. BMJ 2021, 372, n693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musher, D.M.; Rueda, A.M.; Kaka, A.S.; Mapara, S.M. The Association between Pneumococcal Pneumonia and Acute Cardiac Events. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 45, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, E.; Bowe, B.; Al-Aly, Z. Long-Term Cardiovascular Outcomes of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuin, M.; Rigatelli, G.; Battisti, V.; Costola, G.; Roncon, L.; Bilato, C. Increased Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction after COVID-19 Recovery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 372, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosino, P.; Sanduzzi Zamparelli, S.; Mosella, M.; Formisano, R.; Molino, A.; Spedicato, G.A.; Papa, A.; Motta, A.; Di Minno, M.N.D.; Maniscalco, M. Clinical Assessment of Endothelial Function in Convalescent COVID-19 Patients: A Meta-Analysis with Meta-Regressions. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 3233–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.-A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes: Developed by the Task Force on the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Yonetsu, T.; Kim, S.-J.; Xing, L.; Lee, H.; McNulty, I.; Yeh, R.W.; Sakhuja, R.; Zhang, S.; Uemura, S.; et al. Nonculprit Plaques in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes Have More Vulnerable Features Compared with Those with Non-Acute Coronary Syndromes: A 3-Vessel Optical Coherence Tomography Study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2012, 5, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, F.; Regar, E.; Mintz, G.S.; Arbustini, E.; Di Mario, C.; Jang, I.-K.; Akasaka, T.; Costa, M.; Guagliumi, G.; Grube, E.; et al. Expert Review Document on Methodology, Terminology, and Clinical Applications of Optical Coherence Tomography: Physical Principles, Methodology of Image Acquisition, and Clinical Application for Assessment of Coronary Arteries and Atherosclerosis. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeill, B.D.; Jang, I.-K.; Bouma, B.E.; Iftimia, N.; Takano, M.; Yabushita, H.; Shishkov, M.; Kauffman, C.R.; Houser, S.L.; Aretz, H.T.; et al. Focal and Multi-Focal Plaque Macrophage Distributions in Patients with Acute and Stable Presentations of Coronary Artery Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 44, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabushita, H.; Bouma, B.E.; Houser, S.L.; Aretz, H.T.; Jang, I.-K.; Schlendorf, K.H.; Kauffman, C.R.; Shishkov, M.; Kang, D.-H.; Halpern, E.F.; et al. Characterization of Human Atherosclerosis by Optical Coherence Tomography. Circulation 2002, 106, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, D.S.; Lee, J.S.; Soeda, T.; Higuma, T.; Minami, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lee, H.; Yokoyama, H.; Yokota, T.; Okumura, K.; et al. Coronary Calcification and Plaque Vulnerability: An Optical Coherence Tomographic Study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, e003929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legutko, J.; Bryniarski, K.L.; Kaluza, G.L.; Roleder, T.; Pociask, E.; Kedhi, E.; Wojakowski, W.; Jang, I.-K.; Kleczynski, P. Intracoronary Imaging of Vulnerable Plaque-From Clinical Research to Everyday Practice. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, Z.; Mei, Q.; Walline, J.H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Du, B. Cardiovascular Outcomes in Long COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1450470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, K.; Sugiyama, T.; Hoshino, M.; Kakuta, T. Acute Myocardial Infarction Caused by Plaque Erosion After Recovery From COVID-19 Infection Assessed by Multimodality Intracoronary Imaging. Cureus 2022, 14, e25565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberhardt, N.; Noval, M.G.; Kaur, R.; Sajja, S.; Amadori, L.; Das, D.; Cilhoroz, B.; Stewart, O.; Fernandez, D.M.; Shamailova, R.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Triggers pro-Atherogenic Inflammatory Responses in Human Coronary Vessels. bioRxiv 2023, 2, 899–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chidambaram, V.; Kumar, A.; Sadaf, M.I.; Lu, E.; Al’Aref, S.J.; Tarun, T.; Galiatsatos, P.; Gulati, M.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Leucker, T.M.; et al. COVID-19 in the Initiation and Progression of Atherosclerosis: Pathophysiology During and Beyond the Acute Phase. JACC Adv. 2024, 3, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, L.; Cancro, F.P.; Silverio, A.; Di Maio, M.; Iannece, P.; Damato, A.; Alfano, C.; De Luca, G.; Vecchione, C.; Galasso, G. COVID-19 and Acute Coronary Syndromes: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Perspectives. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 4936571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryniarski, K.; Gasior, P.; Camilleri, W.; Tomaniak, M.; Ntantou, E.; Bulnes, J.; Niewiara, L.; Szolc, P.; Kleczynski, P.; Legutko, J.; et al. Invasive Assessment of Culprit and Non-Culprit Coronary Lesions in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. Vessel Plus 2025, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahed, A.C.; Jang, I.-K. Plaque Erosion and Acute Coronary Syndromes: Phenotype, Molecular Characteristics and Future Directions. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maino, A.; Jaffer, F.A. Outcomes Following Plaque Erosion—Based Acute Coronary Syndromes Treated Without Stenting: The Plaque Matters. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e028184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Qin, Y.; Xu, Y.; Hu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, M.; Feng, X.; Liu, Q.; Syed, I.; Demuyakor, A.; et al. Predictors of Non-Stenting Strategy for Acute Coronary Syndrome Caused by Plaque Erosion: Four-Year Outcomes of the EROSION Study. EuroIntervention 2021, 17, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Dai, J.; Hou, J.; Xing, L.; Ma, L.; Liu, H.; Xu, M.; Yao, Y.; Hu, S.; Yamamoto, E.; et al. Effective Anti-Thrombotic Therapy without Stenting: Intravascular Optical Coherence Tomography-Based Management in Plaque Erosion (the EROSION Study). Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mátyás, B.B.; Benedek, I.; Blîndu, E.; Gerculy, R.; Roșca, A.; Rat, N.; Kovács, I.; Opincariu, D.; Parajkó, Z.; Szabó, E.; et al. Elevated FAI Index of Pericoronary Inflammation on Coronary CT Identifies Increased Risk of Coronary Plaque Vulnerability after COVID-19 Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, N.; Tang, X.; Hu, Y.; Lu, H.; Chen, Z.; Duan, S.; Guo, W.; Edavi, P.P.; Yu, Y.; Huang, D.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Association with Atherosclerotic Plaque Progression at Coronary CT Angiography and Adverse Cardiovascular Events. Radiology 2025, 314, e240876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pivina, L.; Orekhov, A.; Batenova, G.; Ygiyeva, D.; Belikhina, T.; Pivin, M.; Dyussupov, A. Assessment of Risk Factors for Coronary Artery Restenosis and Patient Survival During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vito, L.; Niccoli, G.; Porto, I.; Vergallo, R.; Gatto, L.; Prati, F.; Crea, F. Recurrent Acute Coronary Syndrome and Mechanisms of Plaque Instability. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 243, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Lin, Y.; Lin, D.S.; Chang, C.; Huang, C.; Chen, J.; Lin, S.; Shao, Y.J.; Hsu, C. Impact of Multiple Cardiovascular Events on Long-Term Outcomes and Bleeding Risk in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Nationwide Population—Based Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e039290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, V.; Lafrance, M.; Barthoulot, M.; Rousselet, L.; Montaye, M.; Ferrières, J.; Huo Yung Kai, S.; Biasch, K.; Moitry, M.; Amouyel, P.; et al. Long-Term Follow-up of Survivors of a First Acute Coronary Syndrome: Results from the French MONICA Registries from 2009 to 2017. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 378, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Non COVID n = 35 | Post COVID n = 35 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 55.7 ± 12.0 | 65 ± 9.2 | <0.001 |

| Sex (Male), n (%) | 25 (71.4) | 20 (57.1) | 0.212 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.4 ± 5.3 | 27.3 ± 4.5 | 0.097 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 7 (20.0) | 6 (17.1) | 0.759 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 24 (68.6) | 21 (60.0) | 0.454 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 27 (77.1) | 29 (82.9) | 0.550 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 6 (17.1) | 13 (37.1) | 0.060 |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Previous MI, n (%) | 5 (14.3) | 8 (22.9) | 0.356 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 2 (5.7) | 2 (5.7) | - |

| AF/AFL, n (%) | 6 (17.1) | 2 (5.7) | 0.133 |

| CKD, n (%) | 7 (20.0) | 5 (14.3) | 0.555 |

| EF, % | 51.5 ± 10.6 | 46.8 ± 10.6 | 0.065 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 11 (31.4) | 14 (40.0) | 0.454 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L; mg/dL | 4.7 ± 1.2; 182 ± 46 | 4.8 ± 1.4; 186 ± 54 | 0.753 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L; mg/dL | 2.9 ± 0.9; 112 ± 35 | 2.9 ± 1.2; 112 ± 46 | 0.845 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L; mg/dL | 1.2 ± 0.5; 46 ± 19 | 1.4 ± 0.4; 54 ± 15 | 0.144 |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L; mg/dL | 1.4 ± 0.6; 124 ± 53 | 1.3 ± 0.5; 115 ± 44 | 0.667 |

| Hgb, g/dL | 13.3 ± 1.7 | 13.4 ± 2.1 | 0.898 |

| WBC, ×1000/μL | 10.8 ± 2.9 | 9.8 ± 2.8 | 0.156 |

| eGFR, mL/min,1.73 m2 | 71.4 ± 14.9 | 81.5 ± 20.0 | 0.026 |

| Troponin hs (admission), ng/L | 2360 (1200; 4068) | 2055 (1000; 3500) | 0.004 |

| Presentation—STEMI, n (%) | 13 (37.1) | 16 (45.7) | 0.530 |

| Non COVID n = 35 | Post COVID n = 35 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culprit vessel | 0.483 | ||

| LAD, n (%) | 21 (60.0) | 16 (45.7) | |

| RCA, n (%) | 10 (28.5) | 14 (40.0) | |

| Cx, n (%) | 4 (11.5) | 5 (14.3) | |

| POBA, n (%) | 1 (2.9) | 4 (11.4) | 0.088 |

| Number of stents | 0.226 | ||

| 1, n (%) | 25 (71.4) | 22 (62.9) | |

| 2+, n (%) | 9 (25.7) | 9 (25.7) | |

| Thrombectomy, n (%) | 11 (31.4) | 7 (20.0) | 0.423 |

| Multivessel disease, n (%) | 15 (42.9) | 13 (37.1) | 0.626 |

| Non COVID n = 35 | Post COVID n = 35 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underlying pathology (ACS) | 0.225 | ||

| Rupture, n (%) | 23 (65.7) | 18 (51.4) | |

| Erosion, n (%) | 12 (34.3) | 17 (48.6) | |

| Lesion length, mm | 17.9 ± 7.1 | 19.4 ± 4.9 | 0.185 |

| Lipid rich, n (%) | 21 (60.0) | 22 (62.9) | 0.806 |

| Lipid core length, mm | 9.1 ± 3.6 | 12.0 ± 1.9 | 0.005 |

| Mean lipid arc, ° | 170 ± 39 | 181 ± 34 | 0.451 |

| Max lipid arc, ° | 258 ± 70 | 274 ± 55 | 0.601 |

| Lipid index | 1540 ± 616 | 2200 ± 560 | 0.060 |

| TCFA, n (%) | 10 (28.6) | 11 (31.4) | 0.571 |

| FCT, mm | 0.85 ± 0.27 | 0.71 ± 0.25 | 0.089 |

| Calcification, n (%) | 16 (45.7) | 22 (62.9) | 0.150 |

| Macrophages, n (%) | 17 (48.6) | 26 (74.3) | 0.027 |

| Microchannels, n (%) | 12 (34.3) | 11 (31.4) | 0.799 |

| Cholesterol crystals, n (%) | 11 (31.4) | 15 (42.9) | 0.322 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bryniarski, K.L.; Bartus, S.; Legutko, J.; Bryniarski, L.; Gasior, P.; Wojakowski, W.; Rzeszutko, L.; Dziewierz, A.; Zasada, W.; Rakowski, T.; et al. Pathogenesis of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients After COVID-19: An Optical Coherence Tomography Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8895. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248895

Bryniarski KL, Bartus S, Legutko J, Bryniarski L, Gasior P, Wojakowski W, Rzeszutko L, Dziewierz A, Zasada W, Rakowski T, et al. Pathogenesis of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients After COVID-19: An Optical Coherence Tomography Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8895. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248895

Chicago/Turabian StyleBryniarski, Krzysztof L., Stanislaw Bartus, Jacek Legutko, Leszek Bryniarski, Pawel Gasior, Wojciech Wojakowski, Lukasz Rzeszutko, Artur Dziewierz, Wojciech Zasada, Tomasz Rakowski, and et al. 2025. "Pathogenesis of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients After COVID-19: An Optical Coherence Tomography Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8895. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248895

APA StyleBryniarski, K. L., Bartus, S., Legutko, J., Bryniarski, L., Gasior, P., Wojakowski, W., Rzeszutko, L., Dziewierz, A., Zasada, W., Rakowski, T., Makowicz, D., Wojdyla, R., Kleczynski, P., & Jang, I.-K. (2025). Pathogenesis of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients After COVID-19: An Optical Coherence Tomography Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8895. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248895