Abstract

Background/Objectives: Air-polishing has become, in recent years, a very popular additional tool to subgingival debridement for treating periodontal disease. Vitamin D3 plays a crucial role in bone metabolism and calcium-phosphate homeostasis. The aim of our retrospective study was to determine the additional effect of subgingival air-polishing with two types of powders (glycine and erythritol) on patients with different stages of periodontitis and low serum levels of Vitamin D3. Methods: We collected and analysed the data of 62 patients (demographics, vitamin D3 levels, plaque index, periodontal probing depth, bleeding on probing, clinical attachment loss, periodontitis stage and type of air-polishing powder) used during periodontal therapy. Results: We did not observe a significant correlation between periodontal status and vitamin D3 levels/status (mean Vitamin D3 levels: Stage I—20.19 ± 4.413 ng/mL; Stage II—19.482 ± 3.814 ng/mL; Stage III—17.681 ± 5.869 ng/mL; Stage IV—17.578 ± 5.94 ng/mL; and p = 0.539), nor did we find any significant differences in clinical outcomes when using glycine or erythritol in addition to scaling and root planning (SRP) at 3 months after treatment (all p > 0.05). Conclusions: The discrete association between lower levels of vitamin D3 and more advanced stages of periodontitis could suggest a possible influence of vitamin D3 insufficiency on periodontal disease progression. Although safe, easy to use and comfortable for patients, glycine and erythritol showed no differences in periodontal clinical parameters when compared as an addition to SRP.

1. Introduction

Periodontitis, the sixth most common oral illness worldwide, is a chronic, multifactorial inflammatory disease characterised by the progressive destruction of the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone [1,2,3]. Its aetiology is linked to a combination of local and systemic factors, including dysbiotic and anaerobic microbial biofilm—such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, and Treponema denticola—as well as morphological alterations of tooth surfaces, dental arch irregularities, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, occlusal or masticatory imbalances, and systemic health conditions [4,5]. Clinical manifestations of periodontitis include gingival inflammation, the occurrence of periodontal pockets, bleeding on probing, clinical attachment loss, loss of bone as seen by radiographs, mobility, and, in later stages, pathologic migration leading to tooth loss [1,2,5,6].

Cholecalciferol (Vitamin D3) is a fat-soluble secosteroid, primarily synthesised in the skin through ultraviolet B exposure and supplemented by dietary intake, that plays an essential role in regulating calcium–phosphate homeostasis and mineral bone metabolism [7,8,9,10,11,12]. It also plays an essential role in muscle strength, autoimmune disease and diabetes [10]. Vitamin D3 deficiency has been linked to increased risk of fractures, insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease, inflammatory bowel disease, neurodegenerative disease such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s dementia and even some types of cancer [7,8,10,11].

Recent studies and systematic reviews have reported associations between low serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D3 [25(OH)D3] concentrations—typically defined as <20 ng/mL—and chronic periodontitis, with an increased bleeding on probing, whereas higher serum levels appear to correlate with reduced inflammation and improved periodontal stability [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. According to experimental data, vitamin D3 may exert protective effects by inhibiting Porphyromonas gingivalis growth by activating autophagy and reducing inflammation in periodontal tissues [22]. However, there is still conflicting data about the connection between periodontal disease and vitamin D3 levels.

Given that biofilm removal is an essential aspect of periodontal treatment guidelines, air-polishing devices have become a viable supplement to conventional supragingival and subgingival instrumentation. These devices deliver a controlled mixture of water, compressed air, and abrasive particles to effectively disrupt and remove subgingival biofilm. They are considered a safe, comfortable, and time-efficient adjunct to periodontal therapy, complementing hand instrumentation during initial treatment and serving as a stand-alone approach for managing residual pockets or performing supportive periodontal therapy [23].

Despite their effectiveness on enamel, the abrasiveness of sodium bicarbonate powders renders them unsuitable for use on exposed root surfaces. The risk of hard tissue loss is mitigated by low-abrasive polishing powders (LAPPs), particularly those derived from erythritol (a non-cariogenic, well-tolerated, and non-metabolised sugar alcohol) or glycine (an amino acid), which possess smaller particle sizes, reduced hardness, and enhanced water solubility [2,24,25,26]. Several systematic reviews have compared the efficacy of erythritol and glycine as subgingival air-polishing powders during initial periodontal therapy, in the management of residual pockets, and within supportive periodontal care. These analyses reported no significant differences between the two powders in terms of clinical improvements (such as reductions in PPD, CAL, and BOP) or in their effectiveness for biofilm control [23,27,28].

Numerous studies have explored the association between low serum vitamin D3 levels and periodontitis, typically comparing periodontally healthy individuals with patients diagnosed with chronic or aggressive forms of the disease [12,13,14,17]. Most of these investigations have reported significantly lower vitamin D3 levels in patients with periodontitis than in healthy controls, suggesting that vitamin D3 deficiency may play a role in periodontal disease susceptibility. In light of these findings, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of subgingival air-polishing with glycine or erythritol powder as reflected across the four stages of periodontitis (as defined by the 2018 classification [29]) of patients with low vitamin D3 levels.

To address this objective, these null hypotheses were formulated:

- -

- There are no significant differences in the distribution of periodontitis stages, and no associations exist between baseline periodontal parameters and serum vitamin D3 levels;

- -

- There are no significant differences in clinical periodontal parameters (plaque index, probing pocket depth, bleeding on probing, and clinical attachment loss) between patients treated with subgingival air-polishing using glycine powder and those treated with erythritol powder.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Criteria for Patient Selection

The datasets from adult patients with periodontal pathologies were retrospectively collected between March 2024 and May 2025 from the archives of a private clinic in Iasi, Romania, in collaboration with the Department of Periodontics, School of Dentistry, “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Iasi, Romania. The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Iasi with registration number 635/27.08.2025. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments (2013).

2.2. The Study Group

The clinical records of 106 patients diagnosed with stage I, II, III, or IV periodontitis, according to the 2018 classification, were reviewed. Of these, 62 cases (56.85%) met the inclusion criteria, presenting with low serum vitamin D3 levels—classified as deficiency (<20 ng/mL) or insufficiency (20–29.9 ng/mL) [16].

Inclusion criteria consisted of

- -

- Low serum levels of vitamin D3;

- -

- Non-smokers;

- -

- Diagnosis of periodontitis (including stage of disease);

- -

- Ages between 18 years and 50 years;

- -

- A minimum of twenty teeth present for each patient.

The staging of periodontitis used in the study group was as follows [29]:

- -

- Stage I: 1–2 mm interdental CAL (clinical attachment loss), with maximum probing depth of 4 mm, mostly horizontal bone loss and no teeth lost due to periodontitis;

- -

- Stage II: 3–4 mm interdental CAL, with maximum probing depth of 5 mm, mostly horizontal bone loss and no teeth missing due to periodontitis;

- -

- Stage III: ≥5 mm interdental CAL at the site of greatest loss, probing depth of at least 6 mm, a maximum of 4 periodontitis-related teeth lost; can associate vertical bone loss ≥3 mm and furcation involvement class II or III;

- -

- Stage IV: in addition to stage 3, this stage of periodontitis consists of ≥5 teeth lost due to periodontitis and a need for complex rehabilitation due to masticatory dysfunction, secondary occlusal trauma or bite collapse and drifting and flaring of the teeth.

The remaining 44 cases were excluded due to the following criteria:

- -

- Incomplete dataset;

- -

- Habit of smoking 3 years prior to examination, controlled substance abuse;

- -

- Ages older than 50 years;

- -

- Menopausal women;

- -

- Having fewer than 20 teeth or wearing fixed orthodontic appliances;

- -

- Taking antibiotics in the past 3 months;

- -

- Taking anti-inflammatory drugs in the past 4 weeks;

- -

- Patients with a history of vitamin D3 supplementation;

- -

- Receiving periodontal therapy within the past 6 months;

- -

- Failing to come to the 3-month follow-up.

Subsequently, patients were categorised into four main groups based on their periodontal status, and the data extracted from their clinical records were organised as follows:

- -

- Demographic variables, such as age and sex;

- -

- Baseline serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels;

- -

- Periodontal charting at baseline (T0) and three months post-treatment (T1), which included the plaque index (PI), periodontal probing depth (PPD), bleeding on probing (BOP) and clinical attachment loss (CAL);

- -

- Periodontitis stages;

- -

- Details of the administered periodontal therapy;

- -

- Photographic documentation obtained before, during, and after treatment.

2.3. Clinical Evaluation and Non-Surgical Periodontal Treatment Protocol

Being a retrospective study, we gathered the serum concentrations of 25(OH)D3 from the patients’ clinical records. They were determined based on fasting blood samples collected within 7 days from each baseline periodontal evaluation.

Periodontal charting, at baseline and three months post-treatment, included plaque index (PI), periodontal probing depth (PPD), bleeding on probing (BOP) and clinical attachment loss (CAL), and was performed by one experienced, certified periodontist (A.C.T.).

For the PI, a disclosing agent (Rondells Blue, Directa, Upplands Vasby, Sweden) was used on all the lateral aspects of the teeth. The presence of coloured plaque was counted as a “1” and the absence as “0”. The sum of all coloured lateral aspects of the teeth was divided by the total number of examined surfaces and multiplied by 100, thus giving the PI percentage (%).

In a similar manner, the BOP was determined with the help of a periodontal probe (North Carolina) by gently probing every lateral aspect of each tooth. The sum of all bleeding surfaces was divided by the total number of examined surfaces and multiplied by 100, thus obtaining the BOP (%).

Using the same periodontal probe, PPD was calculated for each tooth as the distance between the junctional epithelium and the gingival margin and CAL—the distance between the junctional epithelium and the CEJ (cementum–enamel junction).

As a periodontal treatment protocol, all patients received a full-mouth scaling and root planning without the use of antiseptics prior to our data collection. They were per-formed by the same periodontist (A.C.T.—Figure 1) using hand instruments (Gracey mini curettes—LM Dental, Parainen, Finland) and ultrasonic scalers (Varios 350—NSK, Tochigi, Japan, with Varios G1 and P10 Perio tips—NSK, Tochigi, Japan), completed with subgingival air-polishing with glycine (AirFlow Perio—EMS Dental, Nyon, Switzerland) or erythritol powder (AirFlow Plus—AirFlow Perio—EMS Dental, Nyon, Switzerland), powered by an Air-N-Go Easy handpiece with a Perio Easy tip (Acteon, Merignac, France). The patients’ clinical records had no mention of any complications occurring during the treatment phase (subcutaneous emphysema or post-operative pain).

Figure 1.

Clinical aspect of a stage II periodontitis patient treated with SRP and erythritol subgingival air-polishing (case belonging to Dr Alexandra Cornelia Teodorescu).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The sample size calculation was performed using the online tool available at Calculator.net. The analysis was based on a significance level of 0.05 and a statistical power of 80%, which indicated that a minimum of 59 patients were required for the study. Normality of data distribution was determined using the Shapiro–Wilk test. As the data did not follow a normal distribution, non-parametric tests were applied. Intra-group comparisons between baseline and 3-month values were evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, while inter-group comparisons were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis tests. Associations between categorical variables (vitamin D3 status and periodontitis stage) were assessed using the chi-square test. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive

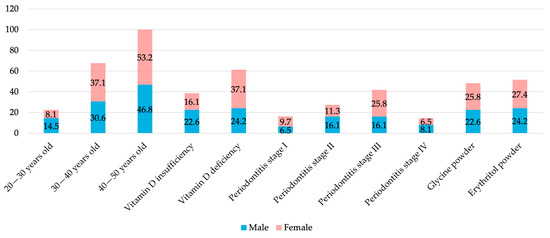

The study included a total of 62 patients (29 males and 33 females), with ages ranging from 22 to 50 and an average age of 42.6 years. The mean serum 25(OH)D3 concentration was 18.56 ng/mL, with 38 patients (61.3%), including 23 females (69.7%), diagnosed with vitamin D3 deficiency (<20 ng/mL). Regarding periodontal status, most patients were diagnosed with stage III periodontitis, of whom 25.8% were females. As for the periodontal therapy, 30 patients received additional subgingival air-polishing with glycine powder, while 32 were treated with erythritol powder (Table 1, Figure 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants (N = 62).

Figure 2.

Distribution of study participant characteristics according to gender.

Analysis of clinical parameters by periodontitis stage revealed statistically significant improvements for all periodontal parameters from baseline to 3 months (p < 0.001), with very large effect sizes (r = 0.85–0.87), indicating great treatment-related changes across the study participants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical parameters of study participants (N = 62).

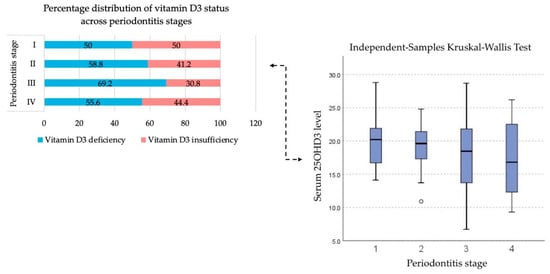

3.2. Testing the First Hypothesis

No significant association was found between serum vitamin D3 levels and periodontitis stage (p = 0.539—Table 3), although there is a tendency for the vitamin D3 levels to be lower as the periodontitis progresses to more severe stages with a median of 20.5 ng/mL—stage I, 19.6 ng/mL—stage II, 18.45 ng/mL—stage III and 16.80 ng/mL—stage IV. It was also observed that patients with stage III periodontitis exhibited a higher prevalence of vitamin D3 deficiency compared with those in the other stages (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Association between periodontitis stage and serum vitamin D3 levels.

Figure 3.

Distribution of baseline serum vitamin D3 concentrations across different stages of periodontitis.

Similarly, baseline periodontal parameters (PI, PPD, BOP, CAL) showed no statistically significant differences (all p > 0.05) when comparing patients with vitamin D3 deficiency to those with insufficiency (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association between baseline periodontal clinical parameters according to vitamin D3 status.

3.3. Testing the Second Hypothesis

Although the group treated with subgingival air-polishing using erythritol powder showed minor improvements in PI, BOP, and CAL when compared to the glycine group, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups at 3 months (all p > 0.05) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association between periodontal clinical parameters according to the type of subgingival air-polishing.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the clinical benefits of erythritol or glycine as adjunctive subgingival air-polishing agents in non-surgical periodontal treatment. This evaluation focused on patients with varying stages of periodontitis and low serum vitamin D3 levels.

4.1. Vitamin D3 Levels and Periodontal Status

In evaluating the first hypothesis, no statistically significant association was identified between serum vitamin D3 status and periodontitis staging, nor between baseline periodontal parameters and vitamin D3 categories (deficiency or insufficiency). Vitamin D3 deficiency was defined as serum levels < 20 ng/mL, whereas insufficiency corresponded to levels between 20 and 29.9 ng/mL. Although patients in more advanced stages of periodontitis tended to exhibit lower vitamin D3 levels, this trend did not reach statistical significance.

This link between levels of vitamin D3 and the severity of periodontitis has been a topic that sparked interest in the last few years in the medical field. But the results of the published studies are conflicting [13,17,30]. It is also important to note that many previously published studies classified patients according to the former periodontitis classification system, which limits the comparability of their results with those of the present study.

Earlier studies have attempted to clarify the relationship between periodontitis and vitamin D3 deficiency. A Norwegian investigation conducted in 2019 assessed serum 25(OH)D3 concentrations in ethnic Norwegian and Tamil refugee patients, both with and without periodontitis. The authors reported that lower vitamin D3 levels were associated with the presence of periodontitis only in the Norwegian cohort, while no significant differences were observed among Tamil participants [17].

Similarly, in 2018, Anbarcıoğlu et al. [13] compared individuals with aggressive or chronic periodontitis to periodontally healthy controls. Their findings indicated that patients with aggressive periodontitis exhibited lower serum vitamin D3 levels than those with chronic periodontitis or healthy individuals, although no statistically significant differences were detected between the chronic periodontitis group and healthy controls [13].

Additional studies have examined vitamin D3 status in patients with moderate to severe periodontitis [30] or severe periodontitis [31] relative to healthy subjects. Both studies reported reduced vitamin D3 levels among periodontitis patients; however, Laky et al. [31] found no significant correlations between vitamin D3 concentration and key periodontal parameters, including PPD, CAL, and BOP.

Contrary to our findings, studies published in 2022 and 2024 found that the stage of periodontitis (I–IV) was significantly negatively correlated with the serum level of vitamin D3. The vitamin D3 level decreased with the progression of the disease to a higher stage [32,33].

One extensive Northern study found that vitamin D3 status was associated with periodontitis stages II–III/IV. People with periodontitis stages II-III/IV had 53% higher odds of having deficient vitamin D3 levels than those in the non-periodontitis/stage I group [34].

However, there is one other study that did not find any association between vitamin D3 levels and periodontal diseases, gingival inflammation to be exact, consistent with our present findings [35]. Several factors can induce vitamin D3 deficiency, including systemic health problems affecting the metabolism of vitamin D3, limited sun exposure and dietary deficiency [36].

It is important to acknowledge that serum vitamin D3 levels are subject to seasonal variation, primarily due to fluctuations in sunlight exposure throughout the year [34]. As the patient data in the present study were collected over a one-year period, this seasonal influence may have introduced variability in the recorded vitamin D3 concentrations.

4.2. Subgingival Air-Polishing

When looking at the additional effect of subgingival air-polishing agents such as glycine and erythritol, we found that, although all the periodontal parameters improved at 3 months after the periodontal therapy, there were no statistically significant differences between the glycine or erythritol groups.

With a particle size of 25–65 μm, glycine is a frequently used air-polishing agent that can reduce the patients’ pain and discomfort during periodontal therapy. It is highly soluble, bio-compatible and has the advantage that it can disrupt the dental biofilm without damaging the hard teeth surfaces or soft tissues surrounding them [37]. It can also have an effect on reducing the subgingival bacterial overgrowth of P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans and F. nucleatum [38].

Erythritol has a particle size of 14 μm, which is smaller and less abrasive when compared to that of glycine powder. Its advantages include good stability and water-soluble properties, and it is used outside the medical field as an artificial sweetener and food additive [37].

At the present time, there are not many studies investigating the effects of glycine or erythritol on the periodontal therapy outcomes when associated with scaling and root planning (SRP). Two different meta-analyses found that there were no significant statistical differences in the improvement of periodontal parameters such as PPD, CAL and BOP, or biofilm control by three subgingival air-polishing powders: erythritol, glycine or trehalose [23,28]. Their findings were consistent with what we have also found regarding glycine versus erythritol as an additional tool to SRP.

Erythritol-focused studies have shown that the agent provides clinical advantages during initial non-surgical periodontal therapy, particularly in cases presenting with deep periodontal pockets [25,28,39]. Conversely, glycine has demonstrated short-term benefits in reducing subclinical inflammation, as indicated by the volume of gingival crevicular fluid [40]. However, when used in conjunction with scaling and root planning (SRP), glycine produced similar clinical, inflammatory, and microbial outcomes to SRP alone [38].

The available speciality literature lacks clinical in vivo studies directly comparing the efficacy of adjunctive glycine and erythritol powders when used in combination with SRP. In 2021, Seidel et al. published an in vitro study that found that power scalers achieved significantly higher relative cleaning efficacy than air-polishing devices for the furcation area, with glycine application with a subgingival nozzle having similar results with ultrasonic scalers. The advantage of the air-polishing systems was the shorter treatment time [41].

In the context of subgingival air-polishing procedures, it is essential to acknowledge the potential risk of subcutaneous emphysema [42,43]. Each dental professional using an air-polishing device should be capable of making a rapid subcutaneous emphysema diagnosis and should know the right clinical approach based on the severity and the patient’s medical history.

4.3. Study Limitations

The present study has certain limitations, including the retrospective nature of the analysis, a limited sample size (which may increase the risk of type II error), and the absence of control groups for the hypotheses investigated (no group with sufficient vitamin D3 levels for the first hypothesis; no SRP-only group for the second one). Future studies should therefore include larger, multicentre cohorts, employ standard measurement protocols, extend follow-up periods, and account for seasonal variations in vitamin D3 synthesis, either by controlling for these factors or by standardising the timing of sample collection to minimise potential confounding effects.

5. Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, no causal relationship between vitamin D3 deficiency and periodontitis could be demonstrated. Nevertheless, the observed association between lower levels and more advanced stages of the disease suggests a possible contributory role of vitamin D3 insufficiency in periodontal deterioration. Recognising this potential association may support the development of more personalised preventive strategies and tailored periodontal therapy.

Oral Vitamin D3 supplementation should be used for all individuals presenting with low vitamin D3 deficiencies, and all periodontitis patients should have their serum levels tested. This approach could provide a more holistic treatment for all patients.

In relation to the adjunctive use of erythritol and glycine in non-surgical periodontal treatment, both subgingival powders have demonstrated safety and patient acceptability. The biofilm disruption by mechanical means is the “golden rule” for periodontitis treatment; thus, combining different treatment approaches could mean better clinical outcomes. However, more studies are required in order to determine whether their application provides a significant therapeutic advantage over conventional approaches and to evaluate whether their cost–benefit ratio justifies routine clinical use.

Overall, the findings from this study reinforce the importance of conventional non-surgical therapy as the foundation of periodontal treatment and indicate that, while vitamin D3 deficiency is common among periodontitis patients, its clinical influence requires further exploration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.C.T., E.-R.B. and S.M.S.; methodology, I.L. and L.P.; validation, A.M. and I.G.Ș.; investigation, A.C.T., B.C.V. and G.R.; resources, A.C.T., B.C.V. and G.R.; writing—original draft preparation A.C.T. and E.-R.B.; writing—review and editing, E.-R.B.; visualisation, A.M. and I.G.Ș.; supervision, I.L. and L.P.; project administration, S.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was carried out in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethic Committee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi, Romania (Number: 635 issued on 27 August 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BOP | Bleeding on probing |

| CAL | Clinical attachment loss |

| LAPP | Low-abrasive polishing powder |

| PI | Plaque index |

| PPD | Periodontal probing depth |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SRP | Scaling and root planning |

References

- Hajishengallis, G.; Chavakis, T. Local and Systemic Mechanisms Linking Periodontal Disease and Inflammatory Comorbidities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghe, D.N.; Bennardo, F.; Silaghi, M.; Popescu, D.-M.; Maftei, G.-A.; Bătăiosu, M.; Surlin, P. Subgingival Use of Air-Polishing Powders: Status of Knowledge—A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, R.A.; Bodechtel, C.; Hertrampf, K.; Hoffmann, T.; Kocher, T.; Nitschke, I.; Schiffner, U.; Stark, H.; Zimmer, S.; Micheelis, W.; et al. The Fifth German Oral Health Study (Fünfte Deutsche Mundgesundheitsstudie, DMS V)—Rationale, Design, and Methods. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saglie, F.R.; Caranza, F.A.; Newman, M.G.; Cheng, L.; Lewin, K.J. Identification of Tissue-Invading Bacteria in Human Periodontal Diseases. J. Periodontal Res. 1982, 17, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surlari, Z.; Virvescu, D.I.; Baciu, E.-R.; Vasluianu, R.-I.; Budală, D.G. The Link between Periodontal Disease and Oral Cancer—A Certainty or a Never-Ending Dilemma? Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 12100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, N.P.; Bartold, P.M. Periodontal Health. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S9–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Prado, E.; Vasconez-Gonzalez, J.; Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S.; Suárez-Sangucho, I.A.; Prieto-Marín, J.G.; Villarreal-Burbano, K.B.; Barriga-Collantes, M.A.; Altamirano-Castillo, J.A.; Borja-Mendoza, D.A.; Pazmiño-Almeida, J.C.; et al. Cholecalciferol (Vitamin D3): Efficacy, Safety, and Implications in Public Health. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1579957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borel, P.; Caillaud, D.; Cano, N.J. Vitamin D Bioavailability: State of the Art. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 1193–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, I.R.; Bolland, M.J.; Grey, A. Effects of vitamin D supplements on bone mineral density: A systematic review and meta-Analysis. Lancet 2014, 383, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, F.M. Vitamin D Deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.L.; Givens, D.I.; Turpeinen, A.M.; Liu, X.; Guo, J. Is Vitamin D Fortification of Dairy Products Effective for Improving Vitamin D Status? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, V.; Lobo, S.; Proença, L.; Mendes, J.J.; Botelho, J. Vitamin D and Periodontitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anbarcioglu, E.; Kirtiloglu, T.; Öztürk, A.; Kolbakir, F.; Acıkgöz, G.; Colak, R. Vitamin D Deficiency in Patients with Aggressive Periodontitis. Oral Dis. 2018, 25, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, A.A.; Kolte, A.P.; Kolte, R.A.; Chari, S.; Gupta, M.; Pakhmode, R. Evaluation and Comparison of Serum Vitamin D and Calcium Levels in Periodontally Healthy, Chronic Gingivitis, and Chronic Periodontitis Patients with and without Diabetes Mellitus—A Cross-Sectional Study. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2019, 77, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, M.; Zeng, C.; Deng, X. Association between Circulating 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Metabolites and Periodontitis: Results from the NHANES 2009–2012 and Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2023, 50, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, G.; Alibrandi, A.; Rapisarda, E.; Matarese, G.; Williams, R.C.; Leonardi, R. Association of Vitamin D in Patients with Periodontitis: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketharanathan, V.; Torgersen, G.R.; Petrovski, B.É.; Preus, H.R. Radiographic Alveolar Bone Level and Levels of Serum 25-OH-Vitamin D3 in Ethnic Norwegian and Tamil Periodontitis Patients and Their Periodontally Healthy Controls. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhou, F.; Xu, H. Circulating vitamin C and D concentrations and risk of dental caries and periodontitis: A Mendelian randomization study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 35–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviezel, B.; Szczypior, L.; Sourla, E.; Baston, T.; Kuzmitski, A.; Peschke, K.; Fetian, I.R.; Villiger, L. Optimizing Vitamin D Levels: Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Practice for Optimal Health in Switzerland. Heal. TIMES Schweiz. Ärztejournal J. 2024, 15, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Meghil, M.M.; Cutler, C.W. Influence of Vitamin D on Periodontal Inflammation: A Review. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.P.N.S.; Goergen, J.; Muniz, F.W.M.G.; Haas, A.N. Vitamin D Levels and Risk for Periodontal Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Periodontal Res. 2018, 53, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Niu, L.; Ma, C.; Huang, Y.; Yang, X.; Shi, Y.; Pan, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; et al. Calcitriol Decreases Live Porphyromonas gingivalis Internalized into Epithelial Cells and Monocytes by Promoting Autophagy. J. Periodontol. 2019, 91, 956–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, G.G.; Leite, F.R.M.; Pennisi, P.R.C.; López, R.; Paranhos, L.R. Use of air polishing for supra- and subgingival biofilm removal for treatment of residual periodontal pockets and supportive periodontal care: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, J.C.; Haribyan, M.; Nergiz, I.; Schmage, P. Air Polishing with Erythritol Powder: In Vitro Effects on Dentin Loss. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2020, 24, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Kwon, E.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Choi, J.; Joo, J.Y. Clinical and microbiological effects of the supplementary use of an erythritol powder air-polishing device in non-surgical periodontal therapy: A randomized clinical trial. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2018, 48, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weusmann, J.; Deschner, J.; Imber, J.C.; Damanaki, A.; Leguizamón, N.D.P.; Nogueira, A.V.B. Cellular effects of glycine and trehalose air-polishing powders on human gingival fibroblasts in vitro. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemmig, T.F.; Arushanov, D.; Daubert, D.; Rothen, M.; Mueller, G.; Leroux, B.; Könönen, E. Randomized Controlled Trial Assessing Efficacy and Safety of Glycine Powder Air Polishing versus Ultrasonic Scaling in Patients with Moderate-to-Advanced Periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, 845–852. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, J.; Zhou, M. Clinical Effects of Erythritol, Glycine, and Trehalose as Subgingival Air-Polishing Powders on Non-Surgical Periodontal Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1593204. [Google Scholar]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Greenwell, H.; Kornman, K.S. Staging and Grading of Periodontitis: Framework and Proposal of a New Classification and Case Definition. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S159–S172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, O.J.; Tatakis, D.N.; Elias-Boneta, A.R.; Del Valle, L.L.; Hernandez, R.; Pousa, M.S.; Palacios, C. Low vitamin D status strongly associated with periodontitis in Puerto Rican adults. BMC Oral Health 2016, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laky, M.; Bertl, K.; Haririan, H.; Andrukhov, O.; Seemann, R.; Volf, I.; Assinger, A.; Gruber, R.; Moritz, A.; Rausch-Fan, X. Serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D are associated with periodontal disease. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 1553–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olszewska-Czyz, I.; Firkova, E. Vitamin D3 Serum Levels in Periodontitis Patients: A Case–Control Study. Medicina 2022, 58, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, W.; Ata, F.; Nosser, N.A.; Mowafey, B. Correlation of Serum Vitamin D and IL-8 to Stages of Periodontitis: A Case-Control Analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, F.M.; Jönsson, B.; Brustad, M. Cross-Sectional Associations between Vitamin D Status and Periodontitis in Adults in Northern Norway: The Tromsø Study 2015–2016. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, C.; Rabbani, R.; Moffatt, M.E.K.; Kelekis-Cholakis, A.; Schroth, R.J. The Relation between Periodontal Disease and Vitamin D. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2019, 84, j4. [Google Scholar]

- Dragonas, P.; El-Sioufi, I.; Bobetsis, Y.A.; Madianos, P.N. Association of Vitamin D with Periodontal Disease: A Narrative Review. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2020, 18, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Vinel, A.A.H.; Roumi, S.; Le Neindre, H.; Millavet, P.; Simon, M.; Cuny, C.; Barthet, J.-S.; Barthet, P.; Laurencin-Dalicieux, S. Non-Surgical Periodontal Treatment: SRP and Innovative Therapeutic Approaches. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2022, 1373, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, W.; Chu, C.; Jing, J.; Yao, N.; Sun, Q.; Li, S. Clinical, Inflammatory, and Microbiological Outcomes of Full-Mouth Scaling with Adjunctive Glycine Powder Air-Polishing: A Randomized Trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2021, 48, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divnic-Resnik, T.; Pradhan, H.; Spahr, A. The Efficacy of the Adjunct Use of Subgingival Air-Polishing Therapy with Erythritol Powder Compared to Conventional Debridement Alone during Initial Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, Y.C.; Corbet, E.F.; Jin, L.J. Subgingival Glycine Powder Air-Polishing as an Additional Approach to Nonsurgical Periodontal Therapy in Subjects with Untreated Chronic Periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2018, 53, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, M.; Borenius, H.; Schorr, S.; Christofzik, D.; Graetz, C. Results of an experimental study of subgingival cleaning effectiveness in the furcation area. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassetti, M.; Bassetti, R.; Sculean, A.; Salvi, G.E. Subcutaneous Emphysema following Non-Surgical Peri-Implantitis Therapy Using an Air Abrasive Device: A Case Report. Swiss Dent. J. 2014, 124, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, V.; García-Caballero, L.; Couto, I.; Diniz, M.; Diz, P.; Limeres, J. Subcutaneous emphysema related to air-powder tooth polishing: A report of three cases. Aust. Dent. J. 2017, 62, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).