Abstract

Background/Objectives: 18F-fluorocholine is a positron emission tomography (PET) tracer earlier found to be a marker of macrophage content in carotid plaques. We aimed to assess the feasibility of 18F-choline PET-MRI to non-invasively localize vulnerable coronary plaques, using optical coherence tomography (OCT) as a reference standard. Methods: Patients with recent myocardial infarction who were scheduled for a secondary angiography of a non-culprit vessel underwent 18F-fluorocholine coronary PET-MRI. Subsequently, OCT was performed during the secondary angiography. Maximum target-to-background (TBRmax) values of 18F-fluorocholine uptake were determined in two vessel sections that contained either vulnerable or stable plaques as defined by OCT. The OCT-based definition of a vulnerable plaque was a fibrous cap thickness < 70 µm. To enhance the detectability of coronary plaques using PET, three different motion-correction strategies were used: multigate respiratory gating motion correction (MRG-MOCO), extended MR-based motion correction (eMR-MOCO), and extended MR-based motion correction with ECG gating (eMR-MOCO-ECG). Results: Fifteen patients were included in this study. One patient needed to be excluded due to extravasation of the tracer. In another patient, no region with only a stable plaque could be identified. TBRmax values were as follows for three different reconstructions in vulnerable versus stable plaques: MRG-MOCO: mean TBRmax 1.45 vs. 1.35, p = 0.52 (n = 13); eMR-MOCO: mean TBRmax 1.47 vs. 1.27, p = 0.26 (n = 11); eMR-MOCO-ECG: mean TBRmax 1.49 vs. 1.26, p = 0.21 (n = 11). Conclusions: 18F-fluorocholine uptake in vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques in coronary arteries was not significantly different from uptake in stable plaques, even though advanced motion-correction methods were applied. That may be caused by multiple factors, such as small coronary plaque size, tracer biology, or remaining cardiac motion.

1. Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a progressive, chronic, inflammatory disease with systemic manifestations affecting large- and medium-sized arteries, leading to plaque formation and arterial narrowing. Such plaques can erode or even suddenly rupture, thereby potentially causing a thrombotic occlusion and obstructing the blood flow. The majority of myocardial infarctions (MI) are caused by such thrombotic events [1]. Although vulnerable plaques have certain pathological characteristics, such as positive remodeling, micro-calcification, and a large necrotic core, identification of vulnerable plaques remains challenging [2,3].

Previously, it was shown that implementing cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) or computed tomography angiography (CTA) in the diagnostic process in NSTEMI patients is a safe gatekeeper for (therapeutic) invasive coronary angiography (ICA) [4]. Regardless, the risk of recurrent MI remains ≈10% within the first year and 5% in each of the subsequent 4 years [5,6]. This is most likely an underestimation, because 17–26% of recurrent plaque ruptures and MI remain clinically silent [7]. The high recurrence rate could be attributable to inaccurate angiographic identification of vulnerable plaques, resulting in inadequate treatment [8,9,10]. The situation is worsened by the fact that vulnerable plaques tend to occur at multiple coronary sites in ≈40% of the patients [10]. Furthermore, it is known that ‘high-risk’ lesions that are anatomically unrelated to the initial event are often responsible for recurrent ischemic events [10,11]. Thus, performing angioplasty of a single lesion may be an insufficient preventive measure.

Non-invasive imaging techniques, such as positron emission tomography (PET), allow studying the natural behavior of plaques longitudinally. Nowadays, hybrid PET-MRI scanners combine the advantages of molecular imaging using PET with the superior soft tissue contrast of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [12]. Hybrid PET-MRI also provides a unique opportunity to apply MRI-based non-rigid respiratory motion correction on both MRI and PET images [13].

The radioactive PET tracer 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is mostly used in oncology but has also proven its value in imaging inflammatory changes in the arterial wall. However, FDG remains a more nonspecific inflammation tracer and has several drawbacks in coronary imaging, e.g., physiological uptake in the myocardium. Recent evidence suggests that other, more specific tracers may be used for metabolic imaging of cell activation, especially in macrophages [14]. Earlier studies demonstrated the feasibility of radiolabeled choline for imaging atherosclerosis, showing 18F-fluorocholine PET is able to identify the inflammatory regions in symptomatic carotid artery plaques, with a significant correlation between tracer uptake and macrophage content on histology [15].

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is an invasive imaging technique that provides detailed images of coronary plaques with a 10–20 micrometers resolution, which is ≈50–100 times higher than what can be achieved using MRI or intravascular ultrasound (IVUS). Due to its superior spatial resolution, OCT can identify a key feature of coronary plaque vulnerability, i.e., the presence of a thin fibrous cap [16]. OCT already proved its usefulness in numerous studies and is therefore considered a reference standard [16,17,18].

In the present feasibility study, we will investigate whether non-invasive 18F-fluorocholine PET-MRI can be used to identify vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary arteries. A PET-based imaging marker for plaque vulnerability in the coronary arteries could potentially be used for various purposes, such as to guide clinical decisions or to serve as a marker to investigate the effectiveness of new pharmaceuticals, such as anti-inflammatory medication, on plaque stability. We will test the hypothesis that vulnerable plaques show a locally increased uptake of 18F-fluorocholine on PET compared to stable plaques using invasive OCT as a reference standard.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

Subjects who presented with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) at the VieCuri hospital in Venlo, underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the culprit vessel, and were diagnosed with multivessel coronary artery disease and subsequently scheduled for a second PCI, were recruited for study participation. NSTEMI was defined as ischemic symptoms with elevated cardiac enzymes (Troponin T/I, creatin kinase-MB), however, in the absence of ST-segment elevations in the ECG. Exclusion criteria were conservatively managed patients not scheduled for PCI, ongoing severe ischemia requiring immediate PCI, hemodynamic instability, severe heart failure (Killip Class ≥ III), chest pain highly suggestive of non-cardiac origin, suspicion or evidence of acute aortic dissection, acute pulmonary embolism, acute pericarditis, life-threatening arrhythmias at the cardiac emergency department or before presentation, tachycardia (>100 bpm), angina pectoris secondary to anemia, untreated hyperthyroidism or severe hypertension (>200/110 mmHg), moderate to severe aortic or mitral valve stenosis, pregnancy, and breast feeding and contra-indications for MRI, including metal implants, cardiac implantable devices, claustrophobia, renal failure, and allergy to gadolinium-containing contrast media. This study was approved by the local ethics committee (METC162043/NL58752.068.16) and conducted according to the declarations of Helsinki. All subjects were 18 years or older and provided written informed consent.

2.2. PET-MR Imaging

After the first PCI procedure in the acute setting and within 72 h of the scheduled second PCI procedure, hybrid PET-MRI was performed on a fully integrated combined 3 Tesla PET-MRI system (Biograph mMR; Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) at the Maastricht University Medical Centre. Subjects were scanned in a headfirst supine position using a 6-channel body matrix and the 12-channel spine radiofrequency coils. First, an MRI-based attenuation map (µ-map) was acquired during an end-expiration breath-hold [18]. Relevant parameters of this Dixon-based µ-map include the following: field-of-view (FOV) = 599 × 271 × 408 mm3, acquired resolution = 2.1 × 2.1 × 2.6 mm3, flip angle = 10°, repetition time (TR) = 3.85 msec, and echo time (TE) = 2.46 msec. Following the µ-map acquisition, the 18F-fluorocholine PET tracer (BV Cyclotron VU, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) was intravenously injected with a dose of 4 MBq/kg (up to a maximum dose of 360 MBq). Five minutes after the PET tracer injection, a static list-mode PET acquisition was started while the respiratory signal was recorded using the respiratory belt. Previous research in the carotid artery showed stable FCH uptake from 10 min until 1 h after injection in both symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid arteries, as well as in vascular background [15].

Simultaneously, during PET acquisition, coronary MR angiography (CMRA) was performed 2 min after an intravenous contrast agent injection of 0.2 mmol/kg gadobutrol (Gadovist; Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Berlin, Germany), up to a maximum of 20 mmol. A 3D spoiled gradient-echo sequence with a fully sampled golden-step Cartesian trajectory with spiral profile ordering was used. Relevant sequence parameters include the following: FOV = 304 × 304 × 104 mm3, acquired resolution = 1.0 × 1.0 × 2.0 mm3, flip angle = 15°, TR = variable based on heart rate, TE = 1.7 msec, and acquisition window ranging between 90 and 130 msec. Three-lead ECG registration was performed to allow for cardiac motion gating. Every heartbeat, just before each acquisition window, a 2D image navigator (iNAV) was acquired, which provides a low-resolution image of the heart in coronal view to allow for subsequent motion correction. Details of this sequence have been previously described [19].

2.3. OCT Imaging

Within 72 h after the hybrid PET-MRI scan, during the planned second PCI procedure at the VieCuri hospital in Venlo, OCT imaging of the secondary pathological vessel was performed before potential stent placement. Before entry into the coronary artery, an intracoronary injection of 100 to 200 µg nitroglycerine was provided. The tip of the OCT catheter (Dragonfly intravascular imaging catheter, St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA) was then placed at least 5 mm distal to the distal edge of the lesion. While obtaining optimal blood clearance by flushing the coronary artery with contrast agent using an automated pump, an automatic pullback through the lesion was initiated, covering at least 5 mm of the proximal and distal parts of the vessel.

2.4. Image Reconstruction

PET image reconstruction was performed with e7 Tools (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) using the ordinary Poisson-ordered subset expectation maximization (OP-OSEM) algorithm with 3 iterations and 21 subsets. Images were reconstructed with a voxel size of 2.08 × 2.08 × 2.03 mm3 and a matrix size of 344 × 344 × 127. For PET attenuation correction, MR-based Dixon µ-maps were used that provided separation between air, lung, fat, and soft tissue. To make up for the smaller FOV of MRI with respect to PET, the maximum likelihood reconstruction of attenuation and activity (MLAA) approach was utilized.

For CMRA motion correction, motion in the left-right (LR) and feet-head (FH) direction is estimated for each heartbeat using the apex of the heart in the iNAV images. Based on the amplitude in the FH direction, CMRA data is allocated to four respiratory phases or bins. The k-space data inside each bin is corrected to the center of the bin using the FH and LR position estimates derived from the iNav. Next, each bin is reconstructed. Using the end-expiration bin as a reference, respiratory non-rigid deformation fields are generated, which are subsequently applied to transform each bin to the end-expiration position, generating the motion-compensated CMRA image [19].

Three different motion-correction strategies were available to correct the PET datasets for respiratory motion: (1) Multiphase respiratory gating motion correction (MRG-MOCO), where motion correction was based solely on the respiratory belt signal as acquired during the entire PET acquisition. Only the PET data acquired during the end-expiration phase were used for image reconstruction. (2) Extended MR-based MOCO (eMR-MOCO), where both the iNav respiratory signal (as described earlier, but only available during ~9 min of CMRA imaging) and the respiratory belt signal (available entire PET acquisition) are used [20]. The time window for which both the iNav respiratory signal and the respiratory belt signal were collected was used to ensure that the binning of PET data on the iNav signal closely matches the binning on the respiratory belt signal by adjusting binning thresholds. These thresholds are then extended for respiratory motion correction of the complete duration of the PET scan. Each bin was reconstructed and combined with other bins using iNav-based motion fields to a reference position to create a respiratory motion-corrected dataset. (3) Finally, eMR-MOCO-ECG applied the combination of eMR-MOCO (strategy 2) and ECG-based cardiac gating to mitigate cardiac motion as well. Only the PET data acquired during the end-diastolic phase, which was derived from the CMRA sequence, was used for eMR-MOCO-ECG reconstruction; other data was discarded. An overview of the three motion-correction strategies is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the three motion-correction strategies.

2.5. Image Analysis

The OCT data was analyzed by an independent core lab (LIMIC Medical, Ridderkerk, The Netherlands), where fibrous cap thickness was determined in all plaques. Plaque vulnerability was defined as a plaque with a thin fibrous cap of ≤70 μm [16]. PET imaging was then co-registered with the CMRA images and analyzed using MIM Vista version 7.3.7 (MIM software, Cleveland, OH, USA). The OCT slice position of the vulnerable plaque was located on the 3D MRI, using vessel side branches as landmarks, by a cardiologist (BR) and nuclear medicine physician (JP), blinded to PET images. A volume of interest (VOI) was defined around the pathological vessel section. In the same vessel, a control lesion with a thick fibrous cap was selected on OCT, pinpointed on the MRI, and analyzed using the same approach as described for the target lesion. After defining the vessel section VOIs, the PET imaging was revealed in the PET and fusion viewports. At this point, the VOIs were only altered when there was an overspill of activity from neighboring structures. The maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) was measured in both the target and control lesions. Target-to-background ratios (TBRs) were calculated by dividing SUVmax values of the target and control lesions by the mean standardized uptake value (SUVmean) of the blood pool in the left atrium.

2.6. Statistics

Differences in TBRs between vulnerable and stable plaques were tested by paired Student’s t-test (normally distributed data) or Wilcoxon signed-rank test (non-normally distributed data). Normality of data was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The correlation between TBRmax and minimal fibrous cap thickness for the combined target and reference lesions was assessed using Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient for each PET reconstruction. All statistical analyses and plot generations were performed using RStudio (Integrated Development Environment for R, version 1.4.1103, Boston, MA, USA). Two-tailed values of p < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

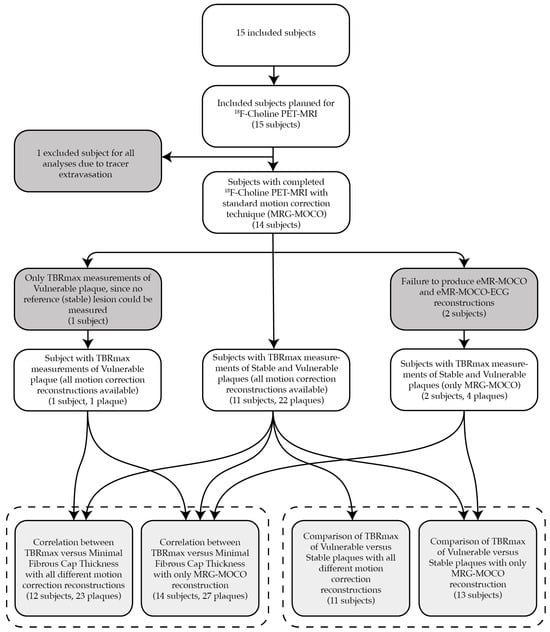

A total of 15 patients were included in this study. One subject was excluded from the final analysis due to PET tracer extravasation. The baseline characteristics of the remaining 14 patients are described in Table 2. Three subjects could only be partially analyzed for the following reasons: (1) CMRA with nondiagnostic image quality due to artifacts (excluded for TBRmax eMR-MOCO and eMR-MOCO-ECG analyses), (2) no coronary reference stable lesion available without a thin fibrous cap in a diffusely diseased vessel (n = 1; excluded for target versus reference TBRmax comparison), and (3) failure to produce eMR-MOCO and eMR-MOCO-ECG respiratory gating reconstructions (excluded for eMR-MOCO and eMR-MOCO-ECG analyses). Figure 1 provides a flowchart with an overview of the reasons for partial or total exclusion of subjects in the different analyses.

Table 2.

Baseline subject characteristics.

Figure 1.

This flowchart provides an overview of the reasons for partial or total exclusion of subjects in the different analyses. In one subject, the PET-MRI data could not be used because of tracer extravasation. In three other subjects, data was partially used, as depicted in the flowchart. The bottom row of boxes resembles the actual analyzed data, grouped per analysis by the dashed box, specifying the number of subjects for each subanalysis, as well as the number of plaques for the TBRmax versus minimal fibrous cap thickness correlation analysis.

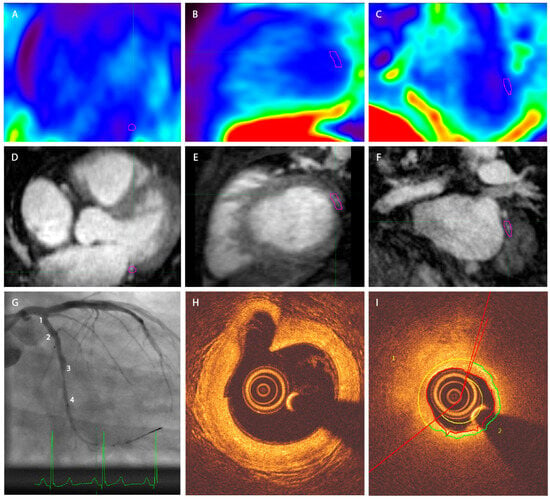

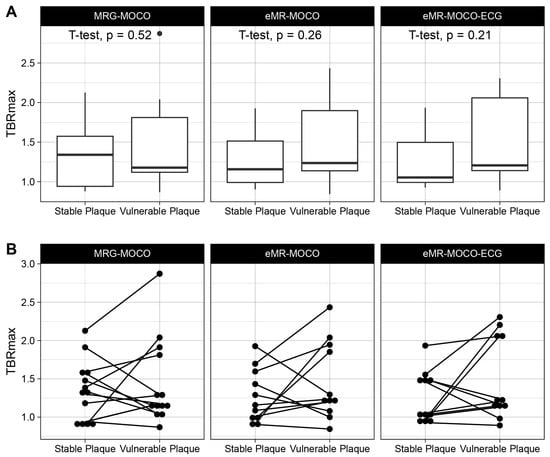

All analyzed patients had a vessel section with a fibrous cap thinner than 70 µm. Figure 2 shows imaging examples of the acquired PET-MRI and OCT imaging. No significant difference between TBRmax values of the vulnerable versus the stable lesions for MRG-MOCO, eMR-MOCO, and eMR-MOCO-ECG was found (MRG-MOCO: mean TBRmax 1.45 vs. 1.35, p = 0.52; eMR-MOCO: 1.47 vs. 1.27, p = 0.26; eMR-MOCO-ECG: 1.49 vs. 1.26, p = 0.21). Boxplots and dot plots of vulnerable versus stable plaque TBRmax values for the different PET reconstructions are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Exemplary PET-MRI and OCT image of one patient. (A–C) Axial, sagittal, and coronal PET. (D–F) Axial, sagittal, and coronal MRI, (G) angiography. Numbers 1–4 represent four different angiographical landmarks to correlate with OCT. A significant stenosis is present between landmarks 3 and 4. (H) OCT image corresponding to landmark 1 in panel (G), a large bifurcating vessel can be distinguished in the left upper quadrant of the image; (I) OCT image in the region of the stenosis as displayed in panel (G). The vessel segment between 2 and 3 contains a plaque with a thin cap on the OCT analysis. The purple VOI in panels (A–F) delineates the target plaque in the left circumflex artery of this patient. No increased tracer uptake was visually detectable in the coronary arteries.

Figure 3.

Boxplots (A) and dot plots (B) of TBRmax values of target and reference lesions. No statistically significant differences were found. The lower and upper hinges of the boxplots represent 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively, and whisker endpoints represent minimum and maximum non-outlying values. The dot in panel (A) represents an outlier.

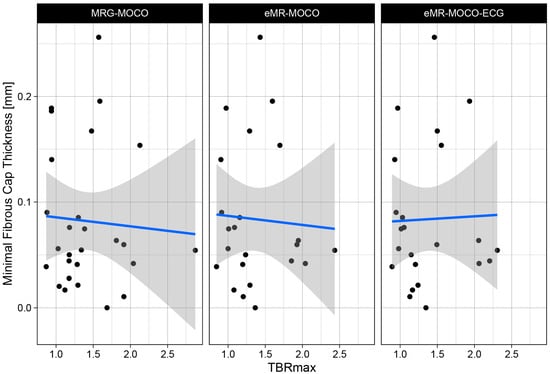

No significant correlation between TBRmax and minimal fibrous cap thickness was found for each of the PET reconstructions (MRG-MOCO: −0.034, p = 0.87; eMR-MOCO: −0.057, p = 0.80; and eMR-MOCO-ECG: −0.036, p = 0.87). Scatterplots of the TBRmax and minimal fibrous cap thickness of the combined vulnerable and stable plaques for each PET reconstruction are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Scatter plot of TBRmax values plotted versus minimal fibrous cap thickness for three different reconstruction methods. No correlation is observed between the TBRmax and the fibrous cap thickness. Regression lines are plotted in blue, with standard error interval displayed as gray area.

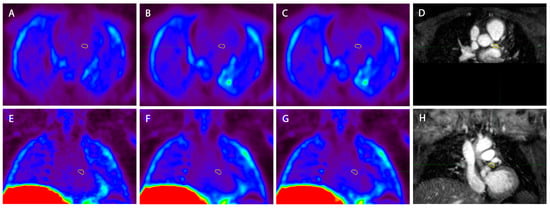

A comparison of the three used PET imaging reconstructions is shown in Figure 5. A difference in noise can be visually appreciated between the different reconstructions, where the MRG-MOCO reconstruction yields more noise than both eMR-MOCO and eMR-MOCO-ECG.

Figure 5.

Example of the three different PET reconstructions in one patient (A) and (E) standard multigate respiratory gating motion correction (MRG-MOCO), (B) and (F) extended MR-based motion correction (eMR-MOCO), (C) and (G) extended MR-based motion correction with ECG gating (eMR-MOCO-ECG), accompanied by 2D image-navigator-based motion-corrected 3D whole-heart MRI for anatomical reference (D) and (H). The top row images show axial reconstructions, while the bottom row shows coronal reconstructions. The yellow volume of interest (VOI) was drawn over the main branch of the left coronary artery (A–H), which contains a vulnerable plaque. Within the VOI, no visually increased uptake was observed.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that investigates the feasibility of identifying vulnerable coronary plaques with non-invasive 18F-fluorocholine PET. Coronary imaging is challenging due to inherent motion artefacts caused by both respiratory and cardiac motion. To correct for these motion artifacts, advanced hybrid PET-MRI respiratory motion correction, as well as cardiac gating methods, were applied in different combinations. Nevertheless, no significant differences were found in 18F-fluorocholine PET uptake between vulnerable and stable coronary plaques as classified by invasive OCT imaging as a reference standard. The use of hybrid PET-MRI in the present study allows for non-rigid respiratory motion correction in our patient population. This PET-MRI reconstruction method allowed us to estimate translational motion from a low-resolution 2D MR image navigator (iNav) acquired each heartbeat and to subsequently apply non-rigid respiratory motion correction between different respiratory bins from the CMRA data. In contrast, respiratory motion-correction methods in PET-CT for the correction of pulmonary and upper abdominal motion artifacts are only correct in the craniocaudal direction. This important advantage of hybrid PET-MRI potentially provides a non-invasive method for analyzing the coronary arteries. Another advantage is that molecular imaging on PET can be combined with functional ischemia imaging on MRI.

The advanced non-rigid respiratory motion-correction techniques that were used in the present study (eMR-MOCO and eMR-MOCO-ECG) correct for respiratory motion in the feet-head and left-right directions, without discarding data. Although we regard this as an important technological step forward, a small amount of residual motion in the anterior–posterior direction can still be present. We regard this as a limitation of the current study, since techniques for motion correction in three dimensions were not available. The MRG-MOCO and eMR-MOCO reconstructions were not corrected for cardiac motion, which leads to motion-induced image blurring. Therefore, we applied ECG-gating with the eMR-MOCO-ECG reconstruction. Also, for this fully motion-corrected reconstruction, no difference in 18F-fluorocholine PET uptake between vulnerable and stable coronary plaques was found.

In contrast to 18F-FDG PET imaging, which has significant drawbacks for coronary imaging, radiolabeled choline is highly taken up in activated macrophages and was hypothesized to be an alternative, more specific tracer for imaging plaque inflammation [15]. Initial murine and rabbit models of atherosclerosis revealed a significantly higher uptake of radiolabeled choline in inflamed atherosclerotic plaques in comparison to healthy vessel wall [21,22,23]. This rapid uptake of radiolabeled choline in plaque macrophages seems to be linked to the upregulation of choline transporters on the cell surface, similar to that observed in macrophages from other inflammatory conditions [14,22]. There are three published reports that retrospectively analyzed choline PET in the diagnosis of prostate cancer, and described a higher presence of the tracer within the atherosclerotic vessel walls [24,25,26]. For obvious reasons, no comparison with the gold standard, histology, has been made in these studies. Our own group earlier investigated vascular wall inflammation in a prospective study that compared 18F-fluorocholine uptake to macrophage content on histology, represented by CD68+ plaque content, in a patient population of symptomatic carotid artery stenosis [15]. That study showed a positive correlation between 18F-fluorocholine uptake and macrophage content, as well as higher uptake in the ipsilateral versus contralateral carotid vessel wall.

An explanation for the lack of 18F-fluorocholine uptake in vulnerable coronary plaques in the current study could be related to the small size of the coronary plaques, compared to larger carotid artery lesions studied earlier. A certain minimum amount of tracer needs to accumulate in a plaque in order to be detected by PET. Sub-voxel size of plaques does not rule out detection, but the partial volume effect can negate detectability. Studies with other tracers, notably 18F-sodiumfluoride (18F-NaF), revealed increased tracer uptake in culprit versus non-culprit coronary plaques of patients with myocardial infarction [27]. Interestingly, this study also showed that patients with 18F-NaF-positive plaques in a stable angina cohort had higher 18F-NaF activity when compared to those with myocardial infarction. The patients with stable angina were older and, therefore, may have had a more extensive plaque burden. Thus, not only the vulnerability but also the size of the plaque determines the TBRmax value. Another difference between coronary and carotid PET imaging is that the carotid arteries are not affected by respiratory motion and cardiac motion, which makes the carotid PET image substantially less challenging.

When investigating coronary artery plaques, no coronary artery specimens can be obtained to correlate PET outcomes to histological findings. In our study, invasive OCT imaging was used as a reference standard to provide detailed images of coronary plaques with a resolution ranging from 10 to 20 µm. This is approximately 50–100 times higher than what can be achieved using MRI or intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), and OCT has been well validated in numerous studies [16,17,28,29,30]. The OCT parameter that we used to define a vulnerable plaque was the presence of a thin fibrous cap, since rupture of such a cap is the main underlying cause of myocardial infarction. We used a threshold of a cap thickness of less than 70 µm for a vulnerable plaque in line with previous studies [31]. While pathologists define a thin fibrous cap using a cut-off value of <65 µm [32], for OCT, one should choose a slightly higher threshold to take into account tissue shrinkage during histological processing [33].

A limitation of this study is that we only used a fibrous cap thickness threshold of less than 70 µm as a criterion for plaque vulnerability. While other characteristics, which are associated with plaque vulnerability, such as lipid burden and macrophage features, can be derived from OCT, we preferred to use a single parameter in order to have a clear parameter that unequivocally identifies vulnerable plaques versus stable plaques in this study with a small sample size.

The anatomical correlation of the plaques on OCT and PET relied on visually comparing vascular anatomy as displayed on angiographical imaging to the coronary MR angiography images. By carefully selecting a segment with stable plaque, sufficiently distant from vulnerable plaques, we ensured that the stable plaque VOI did not include a section of vulnerable plaque. We also made sure that the entire plaque was included in the VOI. The advantage of TBRmax is that this parameter is not influenced by the VOI size, as long as no other 18F-fluorocholine avid structures are included. Therefore, the current negative results cannot be explained by high uptake in stable plaques. Theoretically, a cone-beam CT acquired using a state-of-the-art angiographic gantry could be better suited to co-register the OCT pullback trajectory with the PET images. On the other hand, such a technique would lead to extra radiation exposure.

In the present study, we included NSTEMI patients, where myocardial infarction typically induces a systemic inflammatory response that could influence plaque inflammation and tracer uptake. However, since we performed a paired comparison of tracer uptake between stable and vulnerable plaques within the same patient, the potential effect of the time between NSTEMI and the PET-MRI scan is likely to be minimized. Both stable and vulnerable plaques in the same subject would be similarly affected by the systemic inflammatory response, making the timing less critical for assessing relative differences in tracer uptake between these plaques. Furthermore, there was a considerable amount of time of an average of 30 days, between NSTEMI and PET-MRI, with limited variation in this interval between patients.

A practical limitation concerning the analysis of 18F-fluorocholine uptake in coronary vessels is intense liver uptake, obscuring any vascular uptake located close to the liver due to spill-over of liver activity. This mostly affects the distal right coronary artery, where the lumen and plaques tend to be smaller and are already inherently more challenging for PET imaging in general. In our patient population, however, all vulnerable and stable plaques that were analyzed were in regions not susceptible to activity overspill from the liver. Another limitation of this study is the small sample size since the study was conceived to establish proof of principle. Therefore, this study is not fully able to test diagnostic performance. Although a study with a larger sample size might have been able to detect a statistically significant difference between the TBRmax in vulnerable versus stable lesions, we found that there was a high overlap between the tracer uptake in vulnerable and stable plaques. In approximately one-third of the patients, even a higher TBRmax was observed in the stable than in the vulnerable plaque. Therefore, it is unlikely that a study with a higher sample size will find clinically relevant differences.

In recent years, the perivascular fat attenuation index as measured with CTA has emerged as a marker for coronary inflammation [34]. Although the perivascular fat attenuation index is an indirect marker, while the uptake of a PET tracer in a plaque is a direct marker of plaque inflammation, the perivascular fat attenuation index can be quantified on CTA, which is much more widely available compared to PET and comes with a lower ionizing radiation dose. In the same CTA examination also other CTA imaging risk markers could also be obtained, such as low-attenuation coronary plaque, luminal stenosis severity, coronary calcium score, and total plaque volume [35].

5. Conclusions

PET-MRI with 18F-fluorocholine, using advanced respiratory non-rigid motion correction with or without cardiac gating, did not show significantly higher uptake in vulnerable plaques compared to stable plaques using OCT as a reference standard. These findings in the coronary arteries differ from previous results in the carotid arteries, where more uptake in symptomatic lesions was observed. Multiple inherent factors, such as small coronary plaque size, tracer biology, and cardiac movement, may hamper visualization of coronary macrophage plaque content through 18F-fluorocholine binding.

Author Contributions

Author listing in alphabetical order. Conceptualization, J.B., R.J.H., M.E.K., J.G.M., J.A.J.v.d.P., B.R. and J.E.W. Software, M.A., R.M.B. and C.P. Formal analyses, M.E.K. and J.A.J.v.d.P. Investigation, Y.J.M.v.C., R.J.H. and B.R. Resources, M.A., R.M.B., R.J.H., H.v.L., R.P.M.M. and C.P. Writing—original draft preparation, J.A.J.v.d.P., with contributions in methods by M.A., R.J.H., R.P.M.M. and B.R. Writing—review and editing, all authors. Visualization, J.A.J.v.d.P. Supervision, R.J.H., M.E.K., J.G.M. and B.R. Project Administration, Y.J.M.v.C., R.J.H. and B.R. Funding acquisition M.E.K., H.v.L., J.G.M., B.R. and J.E.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Academic Fund of the VieCuri hospital and Maastricht University Medical Center, and the Weijerhorst foundation (Stichting de Weijerhorst).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Maastricht University (Registration number NL58752.068.16, approval date 1 March 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for all the assistance in OCT analysis offered by Jurgen Ligthart (Limic Medical).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors Jochem A. J. van der Pol, Braim Rahel, Yvonne J. M. van Cauteren, Rik P. M. Moonen, Joan G. Meeder, Suzanne C. Gerretsen, Mueez Aizaz, Claudia Prieto, René M. Botnar, Jan Bucerius, Herman van Langen, Robert J. Holtackers, and Eline M. Kooi declare no conflicts of interest. Joachim. E. Wildberger reports institutional grants via Clinical Trial Center Maastricht: Abbott, Anaconda Biomed, Asklepios, Bayer, Becton & Dickinson Medical, Bentley, Boston, Brainlab, GE Healthcare, Gleamer, Hologic, Inari Medical, Johnson & Johnson, Merit Medical Systems, Nico-Lab, Medtronic, Microvention, Nova Techs, Oldelft Benelux, Ontario Association of Radiologists, Penumbra, Philips, Siemens, Stryker, and Tajpan Sro. Speaker’s bureau via Maastricht UMC+: Bayer, Siemens, all outside the submitted work. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CD68 | Cluster of Differentiation 68 |

| CMR | Cardiac Magnetic Resonance |

| CMRA | Coronary Magnetic Resonance Angiography |

| CTA | Computed Tomography Angiography |

| 18F-FDG | 18-Fluor-fluorodeoxyglucose |

| eMR-MOCO | Extended MR-Based Motion Correction |

| eMR-MOCO-ECG | Extended MR-Based Motion Correction with ECG gating |

| FDG | 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose |

| FOV | Field Of View |

| GRACE-score | Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events score |

| ICA | Invasive Coronary Angiography |

| iNAV-CASPR-MOCO | 2D Image Navigator-Based 3D Whole-Heart Sequence Cartesian Trajectory with Spiral Profile Motion Corrected |

| MI | Myocardial Infarction |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MRG-MOCO | Multigate Respiratory Gating Motion Correction |

| NSTEMI | Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| PCI | Percutaneous Coronary Intervention |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| STEMI | ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

| SUVmax | Maximal Standardized Uptake Value |

| SUVmean | Mean Standardized Uptake Value |

| TBRmax | Maximal Target-to-Background Ratio |

| VOI | Volume of Interest |

References

- Virmani, R.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Burke, A.P.; Farb, A.; Schwartz, S.M. Lessons from sudden coronary death: A comprehensive morphological classification scheme for atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2000, 20, 1262–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dweck, M.R.; Maurovich-Horvat, P.; Leiner, T.; Cosyns, B.; Fayad, Z.A.; Gijsen, F.J.H.; Van der Heiden, K.; Kooi, M.E.; Maehara, A.; E Muller, J.; et al. Contemporary rationale for non-invasive imaging of adverse coronary plaque features to identify the vulnerable patient: A Position Paper from the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Atherosclerosis and Vascular Biology and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 21, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Finn, A.V.; Nakano, M.; Narula, J.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Virmani, R. Concept of vulnerable/unstable plaque. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 1282–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smulders, M.W.; Kietselaer, B.L.; Wildberger, J.E.; Dagnelie, P.C.; Rocca, H.-P.B.; Mingels, A.M.; van Cauteren, Y.J.; Theunissen, R.A.; Post, M.J.; Schalla, S.; et al. Initial Imaging-Guided Strategy Versus Routine Care in Patients With Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 2466–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutlip, D.E.; Chhabra, A.G.; Baim, D.S.; Chauhan, M.S.; Marulkar, S.; Massaro, J.; Bakhai, A.; Cohen, D.J.; Kuntz, R.E.; Ho, K.K. Beyond restenosis: Five-year clinical outcomes from second-generation coronary stent trials. Circulation 2004, 110, 1226–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, R.; Selzer, F.; Faxon, D.P.; Laskey, W.K.; Cohen, H.A.; Slater, J.; Detre, K.M.; Wilensky, R.L. Clinical progression of incidental, asymptomatic lesions discovered during culprit vessel coronary intervention. Circulation 2005, 111, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelbert, E.B.; Cao, J.J.; Sigurdsson, S.; Aspelund, T.; Kellman, P.; Aletras, A.H.; Dyke, C.K.; Thorgeirsson, G.; Eiriksdottir, G.; Launer, L.J.; et al. Prevalence and prognosis of unrecognized myocardial infarction determined by cardiac magnetic resonance in older adults. JAMA 2012, 308, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffon, A.; Biasucci, L.M.; Liuzzo, G.; D’Onofrio, G.; Crea, F.; Maseri, A. Widespread coronary inflammation in unstable angina. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J.; Thomas, A. Thrombosis and acute coronary-artery lesions in sudden cardiac ischemic death. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984, 310, 1137–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.A.; Demetriou, D.; Grines, C.L.; Pica, M.; Shoukfeh, M.; O’Neill, W.W. Multiple complex coronary plaques in patients with acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.W.; Maehara, A.; Lansky, A.J.; de Bruyne, B.; Cristea, E.; Mintz, G.S.; Mehran, R.; McPherson, J.; Farhat, N.; Marso, S.P.; et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizaz, M.; Moonen, R.P.M.; van der Pol, J.A.J.; Prieto, C.; Botnar, R.M.; Kooi, M.E. PET/MRI of atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2020, 10, 1120–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munoz, C.; Neji, R.; Kunze, K.P.; Nekolla, S.G.; Botnar, R.M.; Prieto, C. Respiratory- and cardiac motion-corrected simultaneous whole-heart PET and dual phase coronary MR angiography. Magn. Reson. Med. 2019, 81, 1671–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyss, M.T.; Weber, B.; Honer, M.; Späth, N.; Ametamey, S.M.; Westera, G.; Bode, B.; Kaim, A.H.; Buck, A. 18F-choline in experimental soft tissue infection assessed with autoradiography and high-resolution PET. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2004, 31, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vöö, S.; Kwee, R.M.; Sluimer, J.C.; Schreuder, F.H.B.M.; Wierts, R.; Bauwens, M.; Heeneman, S.; Cleutjens, J.P.M.; van Oostenbrugge, R.J.; Daemen, J.-W.H.; et al. Imaging Intraplaque Inflammation in Carotid Atherosclerosis With 18F-Fluorocholine Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography: Prospective Study on Vulnerable Atheroma With Immunohistochemical Validation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, e004467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, H.; Bourantas, C.; Bagnall, A.; Mintz, G.S.; Kunadian, V. OCT for the identification of vulnerable plaque in acute coronary syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 8, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, H.G.; Costa, M.A.; Guagliumi, G.; Rollins, A.M.; Simon, D.I. Intracoronary optical coherence tomography: A comprehensive review clinical and research applications. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 2, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, K.; Bellinge, J.W.; Butcher, S.C.; Alcock, R.; Spiro, J.; Playford, D.; Hillis, G.S.; Newby, D.E.; Mori, T.A.; Francis, R.; et al. Coronary (18)F-sodium fluoride PET detects high-risk plaque features on optical coherence tomography and CT-angiography in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Atherosclerosis 2021, 319, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, C.; Kunze, K.P.; Neji, R.; Vitadello, T.; Rischpler, C.; Botnar, R.M.; Nekolla, S.G.; Prieto, C. Motion-corrected whole-heart PET-MR for the simultaneous visualisation of coronary artery integrity and myocardial viability: An initial clinical validation. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2018, 45, 1975–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizaz, M.; van der Pol, J.A.J.; Schneider, A.; Munoz, C.; Holtackers, R.J.; van Cauteren, Y.; van Langen, H.; Meeder, J.G.; Rahel, B.M.; Wierts, R.; et al. Extended MRI-based PET motion correction for cardiac PET/MRI. EJNMMI Phys. 2024, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, I.E.; Luoto, P.; Någren, K.; Marjamäki, P.M.; Silvola, J.M.; Hellberg, S.; Laine, V.J.O.; Ylä-Herttuala, S.; Knuuti, J.; Roivainen, A. Uptake of 11C-choline in mouse atherosclerotic plaques. J. Nucl. Med. 2010, 51, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matter, C.M.; Wyss, M.T.; Meier, P.; SpätH, N.; von Lukowicz, T.; Lohmann, C.; Weber, B.; de Molina, A.R.; Lacal, J.C.; Ametamey, S.M.; et al. 18F-choline images murine atherosclerotic plaques ex vivo. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, M.; Ishino, S.; Mukai, T.; Asano, D.; Teramoto, N.; Watabe, H.; Kudomi, N.; Shiomi, M.; Magata, Y.; Iida, H.; et al. (18)F-FDG accumulation in atherosclerotic plaques: Immunohistochemical and PET imaging study. J. Nucl. Med. 2004, 45, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bucerius, J.; Schmaljohann, J.; Böhm, I.; Palmedo, H.; Guhlke, S.; Tiemann, K.; Schild, H.H.; Biersack, H.-J.; Manka, C. Feasibility of 18F-fluoromethylcholine PET/CT for imaging of vessel wall alterations in humans—First results. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2008, 35, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerster, S.; Rominger, A.; Saam, T.; Wolpers, S.; Nikolaou, K.; Cumming, P.; Reiser, M.F.; Bartenstein, P.; Hacker, M. 18F-fluoroethylcholine uptake in arterial vessel walls and cardiovascular risk factors: Correlation in a PET-CT study. Nuklearmedizin 2010, 49, 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, K.; Yonetsu, T.; Kim, S.J.; Xing, L.; Lee, H.; McNulty, I.; Yeh, R.W.; Sakhuja, R.; Zhang, S.; Uemura, S.; et al. Nonculprit plaques in patients with acute coronary syndromes have more vulnerable features compared with those with non-acute coronary syndromes: A 3-vessel optical coherence tomography study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2012, 5, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.V.; Vesey, A.T.; Williams, M.C.; Shah, A.S.; Calvert, P.A.; Craighead, F.H.; Yeoh, S.E.; Wallace, W.; Salter, D.; Fletcher, A.M.; et al. 18F-fluoride positron emission tomography for identification of ruptured and high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques: A prospective clinical trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celeng, C.; Takx, R.A.; Ferencik, M.; Maurovich-Horvat, P. Non-invasive and invasive imaging of vulnerable coronary plaque. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2016, 26, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, G.; Presbitero, P.; Whitbourn, R.; Barlis, P. Current applications of optical coherence tomography for coronary intervention. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 165, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terashima, M.; Kaneda, H.; Suzuki, T. The role of optical coherence tomography in coronary intervention. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Imanishi, T.; Kitabata, H.; Kubo, T.; Takarada, S.; Tanimoto, T.; Kuroi, A.; Tsujioka, H.; Ikejima, H.; Ueno, S.; et al. Morphology of exertion-triggered plaque rupture in patients with acute coronary syndrome: An optical coherence tomography study. Circulation 2008, 118, 2368–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virmani, R.; Burke, A.P.; Farb, A.; Kolodgie, F.D. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, C13–C18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tearney, G.J.; Regar, E.; Akasaka, T.; Adriaenssens, T.; Barlis, P.; Bezerra, H.G.; Bouma, B.; Bruining, N.; Cho, J.M.; Chowdhary, S.; et al. Consensus standards for acquisition, measurement, and reporting of intravascular optical coherence tomography studies: A report from the International Working Group for Intravascular Optical Coherence Tomography Standardization and Validation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 1058–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savo, M.T.; De Amicis, M.; Cozac, D.A.; Cordoni, G.; Corradin, S.; Cozza, E.; Amato, F.; Lassandro, E.; Da Pozzo, S.; Tansella, D.; et al. Comparative Prognostic Value of Coronary Calcium Score and Perivascular Fat Attenuation Index in Coronary Artery Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serruys, P.W.; Hara, H.; Garg, S.; Kawashima, H.; Nørgaard, B.L.; Dweck, M.R.; Bax, J.J.; Knuuti, J.; Nieman, K.; Leipsic, J.A.; et al. Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography for Complete Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 713–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).