Abstract

Despite advances in lipid-lowering and antithrombotic therapy, patients with acute coronary syndromes remain at elevated risk for recurrent events due to persistent atherosclerotic inflammation. This review evaluates inflammation as a therapeutic target in secondary prevention and discusses established, investigational, and emerging strategies. Colchicine, now FDA-approved for cardiovascular risk reduction, lowered major adverse cardiovascular events in COLCOT and LoDoCo2. Canakinumab (IL-1β inhibition) reduced recurrent events in proportion to IL-6 and hsCRP suppression, while ziltivekimab (IL-6 inhibition) achieved profound biomarker reductions but remains investigational. Early-phase studies of anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist) and dapansutrile (oral NLRP3 inhibitor) showed anti-inflammatory effects in early trials, whereas varespladib and darapladib illustrated the challenges of targeting lipid-associated pathways. Beyond direct immunomodulators, GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors provide both cardioprotective and anti-inflammatory benefits, reinforcing their expanding role post-ACS. Additional emerging avenues include triptolidiol, dasatinib, and BTK or JAK/STAT inhibitors, while novel approaches, such as nanozyme delivery systems and CRISPR-based editing, extend the therapeutic horizon. This review highlights the potential of inflammation-targeted therapies to advance secondary prevention in ACS by integrating current evidence and perspectives on future therapeutic developments.

Keywords:

acute coronary syndromes; atherosclerosis; plaque inflammation; residual risk; biomarkers; hsCRP; IL-6; NLRP3 inflammasome; immunomodulation; anti-inflammatory therapy; cardiometabolic therapies; GLP-1 receptor agonists; SGLT2 inhibitors; precision medicine; secondary prevention; acute myocardial infarction; coronary artery disease; translational research; novel therapeutics 1. Introduction

Inflammation is integral to the initiation, progression, and destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques that lead to acute coronary syndromes (ACS) [1,2,3]. Despite contemporary lipid-lowering and antithrombotic strategies, a significant proportion of patients continue to experience recurrent ischemic events driven by residual inflammatory risk (RIR) [4]. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) are well-established biomarkers of RIR, with elevated levels independently associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes even when low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is optimally controlled. These observations have catalyzed a paradigm shift towards inflammation-targeted strategies as adjuncts in secondary prevention [5,6,7].

Randomized trials and meta-analyses over the past decade have demonstrated that targeted anti-inflammatory therapy has the potential to reduce major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in high-risk populations. Low-dose colchicine provides the strongest evidence base amongst anti-inflammatory therapies across post-myocardial infarction (MI) and chronic coronary disease [8,9,10]. The currently investigated cytokine-directed approaches offer mechanistic proof of concept, with interleukin-1β inhibition (IL-1β) lowering events independent of lipid lowering and IL-6 inhibition producing significant biomarker reductions pending outcome confirmation. Cardiometabolic agents, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), provide complementary metabolic and anti-inflammatory benefits, whereas emerging strategies aim upstream by targeting NLRP3 activation, modulating epigenetic and transcriptional programs, and restoring vascular immune homeostasis to achieve precision control of post-ACS inflammation [11,12,13,14,15].

This review examines the current evidence on validated, investigational, and emerging anti-inflammatory therapies following ACS (graphical abstract), evaluates safety and practical implementation, and outlines key directions for precise secondary prevention.

2. Pathophysiology of Inflammation in ACS

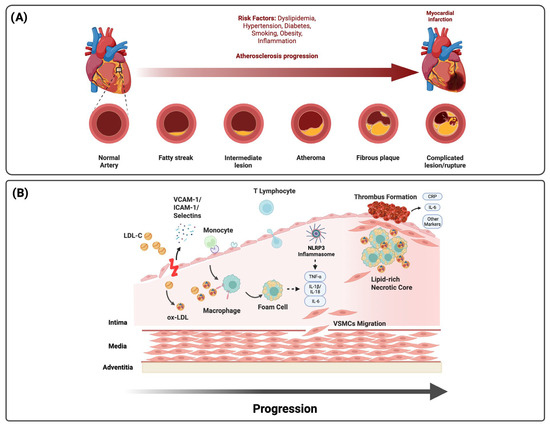

ACS, comprising ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and unstable angina, represents an acute manifestation of chronic atherosclerotic disease driven by endothelial dysfunction and arterial wall inflammation in response to cardiovascular risk factors such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and smoking [1,2,3,4,7]. Inflammation drives every stage of atherosclerosis, from lesion initiation and progression to destabilization, rupture, and thrombosis, with both innate and adaptive immune responses influencing clinical presentation, recurrence risk, and therapeutic outcomes [5,7,16]. Systemic inflammatory states, including autoimmune disease, chronic infection, obesity, and metabolic dysregulation, further prime vascular and circulating immune cells toward a pro-atherogenic phenotype via persistent cytokine activation, lowering the threshold for acute events (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and inflammation in ACS. (A) Atherosclerotic progression from fatty streaks to complicated lesions and rupture is accelerated by dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, smoking, and systemic inflammation. (B) Endothelial activation and LDL infiltration drive monocyte recruitment, foam cell formation, and necrotic core expansion. NLRP3 inflammasome activation amplifies cytokine release (IL-1β, IL-18, IL-6, and TNF-α), promoting plaque destabilization, thrombosis, and systemic residual inflammatory risk reflected by circulating biomarkers (CRP and IL-6).

2.1. Initiation and Propagation of Atheroinflammation

Endothelial activation initiates the inflammatory cascade that promotes leukocyte adhesion and transendothelial migration. Selectins and adhesion molecules (VCAM-1 and ICAM-1) mediate rolling and firm attachment through integrins VLA-4 (α4β1) and LFA-1 (αLβ2) [16,17]. Within this adhesive interface, chemokine gradients direct immune recruitment, with monocyte trafficking governed by the CCL2-CCR2, CX3CL1-CX3CR1, and CCL5-CCR5 axes and neutrophil migration mediated by CXCL1-CXCR2 (Table 1) [3,17]. These pathways are modifiable; intensive lipid lowering reduces CCR2-dependent monocyte mobilization and endothelial activation, linking metabolic therapy to vascular immune control [18,19]. Once within the intima, monocytes differentiate into macrophages that internalize oxidized LDL, form foam cells, and initiate atherosclerotic plaque formation.

Table 1.

Chemokine-Receptor and Adhesion Axes in Coronary Atheroinflammation: Key leukocyte–endothelial signaling pathways mediating monocyte and neutrophil recruitment, adhesion, and transmigration in atherosclerotic plaque inflammation, with translational correlates from experimental and clinical studies.

Macrophage polarization governs plaque evolution and stability. M1-like macrophages activated by TLR ligands and IFN-γ secrete TNF-α, IL-1β, and matrix metalloproteinases that degrade collagen, thin the fibrous cap, and expand the necrotic core. In contrast, M2-like macrophages stimulated by IL-10 and TGF-β enhance efferocytosis, promote collagen synthesis, and facilitate resolution [3,23]. Impaired efferocytosis allows apoptotic cells to undergo secondary necrosis, sustaining inflammation and enlarging the lipid core. These macrophage programs shape plaque phenotype, predisposing it to rupture via cap thinning or to erosion driven by endothelial TLR2 activation and oxidative stress [24,25,26].

The NLRP3 inflammasome links metabolic stress to innate immune amplification. Priming through TLR2/4 or RAGE engagement by oxidized LDL and other damage-associated molecular patterns induces NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β transcription, while activation by cholesterol crystals, ATP-P2X7-mediated potassium efflux, mitochondrial ROS or DNA release, hyperglycemia, or ischemia–reperfusion triggers caspase-1, producing IL-1β and IL-18 [16,20]. This cascade amplifies cytokine signaling and triggers gasdermin-D-mediated pyroptosis, releasing alarmins that perpetuate vascular inflammation. The IL-1β/IL-6 axis couples local plaque activity with systemic inflammatory markers, linking innate activation to clinical outcomes [3,27].

Adaptive immune responses further refine these pathways. Th1 and Th17 subsets release IFN-γ and IL-17 to amplify macrophage activation and neutrophil recruitment, whereas regulatory T and Th2 cells counterbalance inflammation through IL-10 and TGF-β. Dendritic cells sustain chronic activation through continuous antigen presentation [3]. These pattern-recognition, chemokine, and adhesion networks define a receptor-to-fate cascade that governs macrophage polarization, fibrous-cap integrity, and transition from subclinical inflammation to plaque rupture, erosion, or impaired healing [3,17,25]. This framework provides a mechanistic rationale for targeted anti-inflammatory therapy in secondary prevention.

2.2. Plaque Destabilization and Thrombosis

Transition to unstable plaque occurs via rupture (55–65%), erosion (30–35%), or, less commonly, calcified nodules (2–7%) [24,25,28]. Plaque rupture typically involves lipid-rich necrotic cores with thin, inflamed fibrous caps where macrophage and T cell-derived matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) degrade collagen and compromise cap integrity [24]. Plaque erosion, more common in younger patients and women, features endothelial apoptosis and denudation without cap rupture [25]. Calcified nodules occur more often in older adults and chronic kidney disease (CKD) and can protrude through the fibrous cap and trigger thrombosis [28].

Plaque disruption exposes thrombogenic substrates, initiating platelet adhesion, activation, and aggregation. Activated platelets release CD40 ligand and platelet factor 4, which engage CD40 and chemokine receptors on endothelial and immune cells to induce adhesion molecules, recruit leukocytes, and stimulate cytokine release. These interactions promote a neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation that concentrates tissue factor, histones, and proteases, accelerating thrombin generation and stabilizing platelet-rich thrombi [17,20,29,30]. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) on NETs augments endothelial apoptosis, oxidizes LDL, and increases tissue factor expression, a hallmark of plaque erosion [29,31]. Reactive oxygen species further diminish nitric oxide availability, sustaining endothelial dysfunction and leukocyte infiltration. Microembolization of platelet–leukocyte aggregates and NET fragments can obstruct the coronary microcirculation, increasing infarct size and sustaining systemic inflammation [3,32].

Defective efferocytosis in advanced plaque impairs apoptotic cell clearance, leading to secondary necrosis, lipid-core expansion, and persistent inflammation. This dysfunction reflects cleavage of MerTK, disruption of the Gas6-MerTK axis, and inhibitory CD47-SIRPα signaling that suppresses phagocytic uptake [3,23]. Macrophage polarization and efferocytic efficiency, which is shaped by CCL2-CCR2-driven monocyte recruitment and NLRP3-dependent IL-1β activation, govern collagen turnover and cap integrity, while matrix metalloproteinase activity and impaired smooth-muscle repair further weaken the fibrous cap [3,7,24,28]. In contrast, erosion-prone plaques exhibit heightened TLR2 activation by fragmented hyaluronan and other damage-associated ligands, triggering MyD88-NF-κB signaling, endothelial activation, and neutrophil-derived NETosis on denuded surfaces [25,26]. These lesions typically have smaller lipid cores yet intense luminal inflammation, explaining modest systemic biomarkers despite high local thrombogenicity.

Following myocardial infarction, emergency myelopoiesis and splenic remodeling imprint trained immunity in circulating monocytes through chromatin remodeling (H3K4me3) and metabolic reprogramming toward glycolysis and cholesterol biosynthesis, heightening inflammatory responsiveness and recurrence risk [33]. At the same time, impaired biosynthesis of specialized pro-resolving mediators (resolvins, lipoxins, and maresins) limits efferocytosis and fibrous-cap restoration, sustaining vascular inflammation [3,32]. Collectively, platelet activation, leukocyte recruitment, and NETosis form a self-reinforcing circuit that amplifies thrombin generation and plaque thrombosis. Upstream chemokine signaling and NLRP3 activation dictate macrophage phenotype and efferocytic competence, driving rupture through collagen loss, whereas endothelial TLR2-MyD88 signaling with neutrophil recruitment promotes erosion. Persistent trained immunity and impaired resolution maintain inflammatory readiness after the index event, linking local plaque characteristics to RIR and recurrent ACS [3,7,20,26].

2.3. Biomarkers and Imaging of Residual Inflammatory Risk

Residual inflammatory risk after ACS reflects sustained activation of innate immune pathways despite optimal lipid-lowering and antithrombotic therapy. Biomarkers and imaging provide complementary mechanistic and prognostic insights when interpreted in a temporal and clinical context.

hsCRP, synthesized in hepatocytes under STAT3 regulation downstream of IL-6, serves as an integrative marker of IL-6-JAK-STAT3 activity [5,12]. hsCRP typically peaks 48 h after the index event and declines in uncomplicated cases, whereas IL-6 rises earlier and amplifies the acute-phase cascade through gp130-JAK-STAT3 signaling, driving hepatic CRP and fibrinogen synthesis [27]. Other biomarkers, summarized in Table 2, include NETs and MPO and serve as markers of thrombo-inflammatory activity; NETs, generated through PAD4-dependent chromatin decondensation, form scaffolds for thrombin generation and amplify endothelial injury, while circulating NET fragments and MPO-DNA complexes indicate ongoing NETosis and oxidative stress linking innate immunity to microvascular obstruction and thrombosis [20,29,31]. MPO further catalyzes LDL oxidation and promotes endothelial apoptosis, mechanisms particularly relevant in plaque erosion. Additional systemic biomarkers, such as serum amyloid A, fibrinogen, and growth-differentiation factor-15, together with leukocyte-derived ratios (NLR, MLR), integrate inflammatory and prothrombotic activity [32,34]. Emerging candidates, including GlycA, soluble uPAR, and clonal hematopoiesis (CHIP) mutations, extend mechanistic profiling but remain investigational.

Table 2.

Inflammation-related biomarkers post-ACS: Inflammation-related biomarkers provide mechanistic and prognostic insights beyond conventional risk markers. hsCRP and IL-6 are validated for residual inflammatory risk, and NT-proBNP and GDF-15 add prognostic utility, while others (e.g., MPO, GlycA, suPAR, CHIP, and NET markers) remain investigational. Current guidelines suggest hsCRP (≥2 mg/L) and NT-proBNP for post-ACS risk stratification.

hsCRP and IL-6 are the most validated markers of RIR. Elevated baseline or sustained post-ACS hsCRP and IL-6 levels predict ASCVD with strength comparable to LDL-C or Lp(a). Individuals with both hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L and LDL-C ≥ 130 mg/dL observed substantially higher 30-year event rates [35]. Persistently elevated hsCRP or IL-6 levels 3–12 months after ACS identify patients at greater risk of recurrence and mortality who may derive benefit from adjunctive inflammation-lowering therapy [1,3,5,7]. hsCRP has also been shown to identify cardiovascular risk even in individuals without standard modifiable risk factors (SMuRF-less). In the Women’s Health Study, women with hsCRP levels above 3 mg/L had a 77% higher risk of coronary heart disease, a 39% higher risk of stroke, and a 52% higher risk of total cardiovascular events over 30 years despite the absence of traditional risk factors, establishing inflammation as an independent driver of atherosclerotic risk [36].

Imaging further refines inflammatory risk assessment by localizing active vascular inflammation. ^18F-FDG PET identifies metabolically active plaques reflecting macrophage glycolytic flux, while ^18F-NaF PET highlights microcalcification associated with plaque healing and instability [37]. High-resolution MRI and OCT quantify fibrous-cap thickness, lipid-core burden, and cap disruption, aiding phenotype-specific risk stratification [25,26]. Integration of biomarker kinetics with imaging signatures may refine patient selection and optimal timing of anti-inflammatory therapy in post-ACS management.

Emerging strategies now target inflammation through multiple complementary pathways, including inhibition of P-selectin to limit platelet–leukocyte interactions, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase blockade to suppress NLRP3 activation, IL-6-JAK-STAT inhibition to blunt cytokine propagation, and 5-HT2B antagonism to modulate macrophage phenotype [3,17]. Combining mechanistic biomarkers with imaging-derived endotypes may enable precision-guided anti-inflammatory therapy to mitigate residual risk and improve outcomes after ACS.

3. Therapies for Secondary Prevention

3.1. Guideline Foundation: Lipids, Antithrombotics, and Residual Inflammatory Risk

Current ACC/AHA and ESC guidelines (Table 3) for secondary prevention after ACS emphasize high-intensity statin therapy, with ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors as adjuncts for additional LDL-C lowering, and dual antiplatelet therapy for at least 12 months [1,2]. Statins exert both lipid-lowering and anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting isoprenoid synthesis, reducing prenylation of small GTP-binding proteins such as Rho and Rac, and thereby attenuating NF-κB activation and lowering CRP and IL-6. Imaging studies have shown parallel reductions in plaque inflammation, necrotic core, and plaque volume independent of LDL-C changes [18,19]. Ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors, and bempedoic acid provide incremental LDL-C reduction and modest hsCRP lowering (typically 10–20%), which is likely secondary to lipid lowering rather than a direct anti-inflammatory action [38,39,40]. These therapies reduce lipid burden and modestly reduce inflammatory cascades, yet many patients remain at high RIR.

Table 3.

Guideline Recommendations for Adjunctive Therapies in Secondary Prevention Post-ACS/CCS: Summary of ACC/AHA and ESC recommendations for adjunctive therapies beyond statins. Both societies endorse high-intensity statins with nonstatin therapies (ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors) if LDL-C goals are unmet. Colchicine is assigned a IIb recommendation in ACS, with stronger support in coronary syndromes when residual inflammatory risk persists. GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors are recommended in ASCVD with type 2 diabetes, with expanding indications for obesity, HF, and CKD. hsCRP is recognized as a marker of residual inflammatory risk, with ESC providing a IIa recommendation for biomarker-guided therapy selection.

Both societies endorse selective anti-inflammatory therapy for selected high-risk patients with RIR, typically hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L, despite guideline-directed therapy [1,41]. However, hsCRP testing remains underutilized, and adoption of anti-inflammatory therapy is limited by uncertainty over thresholds, limited recommendations, and safety concerns. Mechanistically, RIR reflects persistent endothelial activation, immune cell infiltration, and maladaptive cytokine signaling despite aggressive lipid lowering, providing a rationale for integrating inflammation-targeted strategies into comprehensive secondary prevention.

3.2. Clinically Supported Therapies

Colchicine

Colchicine is an inexpensive oral anti-inflammatory that inhibits microtubule polymerization, suppressing neutrophil activation, chemotaxis, and NLRP3 inflammasome signaling, thereby reducing IL-1β and IL-6 production and downregulating endothelial adhesion molecules and chemokines. Additional effects on platelet activation and endothelial dysfunction may contribute to antithrombotic benefit [42,43]. Efficacy for secondary prevention is supported by two pivotal trials. In COLCOT, 4745 patients with recent MI treated with colchicine at 0.5 mg daily for a median of 22.6 months had a 23% relative risk reduction in the composite of CV death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke, or urgent angina-driven revascularization (HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.61–0.96; p = 0.02), driven by fewer urgent revascularizations and strokes; benefit was greatest when initiated within 3 days post-MI (HR 0.52; 95% CI 0.32–0.84) [8,44]. In LoDoCo2, 5522 patients with stable CAD experienced a 31% relative risk reduction in CV death, MI, ischemic stroke, or ischemia-driven revascularization over 28.6 months (HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.57–0.83; p < 0.001), with a non-significant trend toward higher non-CV mortality (HR 1.51; 95% CI 0.99–2.31) [9]. Meta-analyses of up to nine RCTs (>30,000 participants) report a 12–25% reduction in major adverse CV events (HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.56–0.93), with consistent benefit across prior MI and stable CAD, which is comparable to, or exceeds, some adjunctive lipid-lowering therapies [45]. Benefit persists despite only modest hsCRP lowering, which supports downstream anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic effects [10].

Tolerability is generally favorable; myotoxicity risk is not increased at 0.5 mg daily in patients without severe renal/hepatic impairment or strong CYP3A4/P-gp inhibitors, although therapy is contraindicated when creatinine clearance is less than 15 mL/min or with severe hepatic dysfunction [46]. Mild gastrointestinal intolerance (mainly diarrhea) is the most frequent adverse effect, with no excess of serious infection, cancer, or non-CV death leading to discontinuation in 10% [45,46]. Discontinuation risk varies by study design: the relative risk of discontinuation was 1.60 overall, decreased to 1.34 after excluding non-placebo trials, and was lowest and nonsignificant (RR 1.26) in the three largest placebo-controlled studies. Importantly, the estimated net clinical benefit remained favorable, preventing 17.8 events per 1000 patients (p < 0.001), supporting colchicine as a high-value adjunct in secondary prevention [47].

In 2023, the FDA approved colchicine at 0.5 mg daily to reduce CV risk in adults with ASCVD or multiple risk factors, facilitating integration into secondary prevention [10,48]. ACC/AHA 2025 assigns a Class IIb (B-R) recommendation to consider colchicine in ACS and CCS to reduce MACE, and ESC 2023 gives it Class IIb (A) for long-term use in selected ACS patients and Class IIa (A) in CCS for secondary prevention when residual inflammatory risk or recurrent events are present [1,2]. Despite class recommendations, clinical evidence remains heterogeneous. Smaller ACS trials and pooled analyses show variable efficacy when colchicine is initiated late or in lower-risk populations. A recent network meta-analysis demonstrated that initiation beyond seven days post-MI yielded no significant reduction in recurrent ischemic events (IRR 0.94; 95% CI 0.81–1.09), whereas treatment within 24 h conferred greater benefit (IRR 0.72; 95% CI 0.58–0.89) [49]. The non-significant trend toward higher non-cardiovascular mortality observed in LoDoCo2 (HR 1.51; 95% CI 0.99–2.31) highlights the need for adequately powered confirmatory outcome trials to define optimal timing, safety, and patient selection for long-term anti-inflammatory therapy.

Canakinumab

Inflammation post-ACS is amplified by NLRP3 activation with IL-1β release and downstream IL-6 signaling. Canakinumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that neutralizes IL-1β within the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway implicated in atherothrombosis [12,30]. In CANTOS, 10,061 patients with prior MI and hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L were randomized to canakinumab 50, 150, or 300 mg subcutaneously every 3 months versus placebo. Over 3.7 years, the 150 mg dose reduced nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death by 15% (HR 0.85; 95% CI 0.74–0.98; p = 0.021) without affecting lipids, corresponding to an absolute risk reduction of about 0.6% per year and an NNT of 167. Higher doses did not add efficacy or worsen side effects [12]. Benefit correlated with on-treatment reductions in hsCRP and IL-6, with the greatest effect in patients achieving hsCRP < 2 mg/L (HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.66–0.85; p < 0.0001 for MACE; cardiovascular mortality HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.56–0.85) [50]. However, canakinumab increased fatal infection and sepsis (HR 1.48) and did not reduce all-cause or CV mortality (HR 0.94; 95% CI 0.83–1.06) [12].

Despite demonstrating proof-of-concept of cytokine-targeted therapy, its clinical applicability is limited by safety concerns, lack of regulatory approval, and an annual cost of nearly USD 200,000, with cost-effectiveness analyses remaining unfavorable even with modeled 90% price reductions [51,52]. Current use is largely confined to rare autoinflammatory syndromes.

3.3. Investigational Therapies

IL-1/IL-6 Axis (Anakinra, Ziltivekimab, and Tocilizumab)

Anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, has been evaluated in multiple STEMI trials. In VCU ART3, 100 mg subcutaneously once or twice daily for 14 days reduced hsCRP AUC from 214 to 67 mg·day/L (p < 0.001) without improving LV remodeling or LVEF at 12 months, but importantly, it lowered death or new HF (9.4% vs. 25.7%, p = 0.046) and eliminated HF hospitalizations (0% vs. 11.4%, p = 0.011) [53]. Pooled VCU ART data showed that there was no effect on recurrent ischemic events (HR 1.08; 95% CI 0.52–2.24) but a marked reduction in death or HF (HR 0.16; 95% CI 0.04–0.65), with greater benefit in patients with a high inflammatory burden [54]. No excess serious infections were reported, though mild side-effects of injection-site reactions were more frequent. A network meta-analysis of 23 RCTs with 28,220 patients suggested that initiation within 24 h may reduce HF events (IRR 0.38; 95% CI 0.18–0.79) but certainty is low, and a 2024 Cochrane review rated evidence for MACE reduction as low to very low [49,55]. Anakinra remains investigational with no ASCVD prevention approval.

Ziltivekimab, a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the IL-6 ligand, achieved dose-dependent hsCRP reductions of 77%, 88%, and 92% at 7.5, 15, and 30 mg monthly in RESCUE versus 4% with placebo, and it also lowered fibrinogen, SAA, haptoglobin, secretory phospholipase A2, and Lp(a) [15,56]. Secondary analyses showed reduced neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, supporting broad anti-inflammatory effects [57]. Tolerability was favorable, with no serious cytopenias. A phase 3 ZEUS outcomes trial in approximately 6200 patients with ASCVD, CKD, and elevated hsCRP is ongoing; ziltivekimab is not yet approved [58]. Additionally, Tocilizumab, a monoclonal IL-6 receptor antagonist, has been studied in acute STEMI. In ASSAIL-MI, a single 280 mg IV infusion within 6 h of symptom onset increased myocardial salvage index by 5.6 percentage points (69.3% vs. 63.6%; p = 0.04) and reduced microvascular obstruction but did not significantly reduce final infarct size or short-term MACE [59]. While it improves vascular function in other contexts, its effect on cardiac outcomes remains unproven.

Overall, the IL-1/IL-6 inhibition remains biologically compelling post-ACS, with canakinumab providing the proof-of-concept. Anakinra shows potential for HF prevention without ischemic benefit, ziltivekimab yields profound biomarker reductions with outcomes pending, and tocilizumab provides mechanistic benefit without clear clinical impact. Guideline adoption awaits phase 3 results and likely applies to patients with high baseline inflammatory burden. Cost-effectiveness post-ACS is unknown, and pricing and access barriers will likely mirror other biologics.

NLRP3 Inflammasome and P-Selectin Inhibition (Dapansutrile and Inclacumab)

Dapansutrile is an oral, selective NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor that acts upstream of IL-1β production [60]. Phase 2 studies in acute gout and other inflammatory conditions have shown significant hsCRP reductions and favorable safety at doses up to 1000 mg/day [60,61]. The oral route offers practical advantages for long-term therapy compared with injectable biologics. However, no clinical outcomes data exist for post-ACS prevention. Its anticipated effects on IL-1β, IL-6, and hsCRP mirror those of canakinumab and anakinra, but efficacy and safety remain unproven in large-scale trials [62]. Furthermore, inclacumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting P-selectin, and it is hypothesized to attenuate platelet–leukocyte interactions and downstream vascular inflammation [21]. In SELECT-ACS, 530 NSTEMI patients undergoing PCI received a single pre-procedural infusion of inclacumab (5 or 20 mg/kg) or placebo. The 20 mg/kg dose within 3 h before PCI reduced periprocedural injury, lowering troponin I by 24.4% (p = 0.05) and CK-MB by 27.3% (p = 0.057) at 24 h, with a larger effect when given <180 min before PCI (troponin I—43.5%, p = 0.019) [22]. The trial was not powered for long-term MACE, and effects on recurrent MI, HF, or mortality are unknown. Safety was comparable to placebo. Both agents remain investigational and are not approved for secondary prevention of ASCVD.

3.4. Neutral or Negative Targets (Methotrexate, sPLA2, Lp-PLA2, p38 MAPK, and Complement C5i)

Several anti-inflammatory agents have failed to demonstrate cardiovascular benefit in large trials, highlighting the need for biologically validated targets and appropriate patient selection. Methotrexate, despite the established anti-inflammatory effects in rheumatologic disease largely mediated through adenosine release, neither reduced IL-1β, IL-6, or hsCRP nor lowered MACE in the CIRT trial of 4786 patients with stable ASCVD and diabetes or metabolic syndrome (HR 0.96; 95% CI 0.79–1.16), potentially reflecting its limited activity on the NLRP3-IL-1β-IL-6 axis and inclusion of participants without elevated baseline inflammation [63]. Varespladib, a secretory phospholipase A2 inhibitor, was terminated early in VISTA-16 for futility and increased MI risk (HR 1.66; 95% CI 1.16–2.39) [64]. Additionally, darapladib (lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 inhibitor) showed no benefit in SOLID-TIMI 52 (HR 0.94; 95% CI 0.85–1.03), and losmapimod (p38 MAPK inhibitor) was neutral in LATITUDE-TIMI 60 (HR 1.16; 95% CI 0.91–1.47) [65,66]. Pexelizumab, a complement C5 inhibitor, also failed in STEMI and CABG populations, though exploratory analyses suggested possible mortality benefit in high-risk surgical subgroups [67,68]. These findings emphasize the need to target pathways with causal links to atherothrombosis and to select patients with demonstrable RIR.

4. Adjunct Cardiometabolic Modulators (GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2i)

GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2i are cornerstone cardiometabolic therapies with complementary metabolic, vascular, and anti-inflammatory effects for secondary prevention in ASCVD [13,14]. GLP-1 RAs produce weight loss, improve glycemic and lipid control, lower blood pressure, and reduce inflammatory signaling [69,70]. They also lower CRP, IL-6, TNF-α, and monocyte–macrophage activation, improve endothelial function, and attenuate vascular inflammation [71,72,73]. In SELECT, semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly reduced CV death, nonfatal MI, or stroke by 20% in 17,604 overweight/obese adults without diabetes (HR 0.80; 95% CI 0.72–0.90; p < 0.001), with NNTs of 67 for MACE and 207 for MI. Meta-analyses (>100,000 patients) confirm reductions in MACE (RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.81–0.93), MI (RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.79–0.94), stroke (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.81–0.96), and CV death (RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.80–0.95) [74,75]. SUSTAIN-6 and REWIND reported 26% and 12% MACE reductions (HR 0.74; 95% CI 0.58–0.95 and HR 0.88; 95% CI 0.79–0.99, respectively), and LEADER showed liraglutide lowered MACE (HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.78–0.97) and all-cause mortality (HR 0.85; 95% CI 0.74–0.97) [76,77,78]. Benefits were consistent across subgroups, including prior MI or stroke, and reflect both metabolic and direct anti-inflammatory actions [79]. Post-MI data suggest improved survival and fewer recurrences, particularly in higher BMI or PCI populations, with meta-analyses showing a 14% MI risk reduction [74,80,81]. Adverse effects are mainly gastrointestinal; hypoglycemia risk is low without insulin or sulfonylureas [13,74]. The guideline-recommended CV dose is semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly with gradual titration [1].

SGLT2i benefits via hemodynamic unloading improved myocardial energetics, antifibrotic effects, and sympathetic inhibition [69,70]. Anti-inflammatory effects have shown to lower CRP, ferritin, leptin, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, increase adiponectin, improve vascular function, and attenuate cardiac remodeling [69,82]. Empagliflozin and dapagliflozin been have shown to reduce MACE in type 2 diabetes with ASCVD (HR 0.89; 95% CI 0.83–0.96), with stronger effects on HF hospitalization (HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.61–0.79) and kidney disease progression (HR 0.55; 95% CI 0.48–0.63) [83]. EMPA-REG OUTCOME established empagliflozin’s benefit, showing large reductions in cardiovascular death (HR 0.62; 95% CI 0.49–0.77), heart failure hospitalization (HR 0.65; 95% CI 0.50–0.85), and all-cause mortality (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0.57–0.82) [84]. Post-MI trials (EMPACT-MI, DAPA-MI) were neutral for CV death/HF hospitalization in patients without diabetes or HF, but pooled analyses suggest early initiation reduces MACE and HF hospitalization [85,86]. Observational post-AMI studies in diabetes further support these findings, with lower cardiovascular death (HR 0.42; 95% CI 0.28–0.63), heart failure hospitalization (HR 0.59; 95% CI 0.47–0.74), and all-cause mortality (HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.56–0.85) without more recurrent MI or stroke [87]. Adverse events include genital infections, hypovolemia, and rare ketoacidosis; the guideline-recommended dose is 10 mg daily [1,14].

Together, these classes are complementary, with combination therapy offering potential maximal protection in appropriately selected patients [88]. Observational data suggest additive benefits with combination therapy, including a 30% MACE reduction and a 57% reduction in serious renal events versus GLP-1 RA alone, with good tolerability and outcomes similar to SGLT2i [89,90]. Cost-effectiveness generally favors SGLT2i and colchicine, while GLP-1 RAs remain high-value in selected high-risk patients [91]. Guidelines recommend GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2i for secondary prevention in ASCVD, including post-MI and in overweight or obese patients with stable disease. Early post-ACS initiation appears safe and may accelerate benefit, although stable-phase initiation yields comparable long-term outcomes [1,2,41,92].

5. Emerging Mechanisms and Platforms

5.1. Immune-Signaling Modulators (BTK, JAK/STAT, and 5-HT2B)

Evidence for novel mechanistic therapies in secondary prevention post-ACS/MI remains largely confined to preclinical studies [93,94]. Triptolidiol, a triptolide derivative with anti-inflammatory properties, has demonstrated favorable effects in translation research, with no human cardiovascular data [93]. Dasatinib, a BCR-ABL1 inhibitor approved for hematologic malignancies, has shown preclinical evidence of reduced cholesterol uptake, suggesting potential anti-atherosclerotic effects. However, in oncology cohorts, dasatinib was associated with a 2–4% incidence of cardiovascular ischemic events, though these rates were not elevated compared with matched cohorts [95,96].

BTK inhibitors such as ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib are widely used in B-cell malignancies. BTK mediates B-cell receptor signaling and participates in innate immune activation through NLRP3 inflammasome assembly; its inhibition potentially reduces IL-1β production and downstream cytokine cascades implicated in plaque destabilization [97]. While preclinical data suggest immune modulation may influence atherosclerosis, clinical use has been associated with atrial fibrillation, bleeding, and hypertension, and pooled analyses have not demonstrated cardiovascular benefit compared with standard therapy [97,98].

Similarly, JAK/STAT inhibitors such as tofacitinib and ruxolitinib target cytokine-driven pathways central to vascular inflammation. IL-6-JAK-STAT signaling drives hepatic CRP synthesis and systemic inflammation, while IFN-γ-JAK-STAT promotes macrophage activation and plaque vulnerability [99,100]. Although these agents have shown potential to reduce cardiovascular events in autoimmune and myeloproliferative disorders, no randomized trials have evaluated their use after ACS or MI due to concerns regarding prothrombotic risk and cardiovascular safety [99,100,101,102]. Interest has also extended to 5-HT2B receptor modulators, which reduce fibrosis and adverse remodeling in animal models of MI, though they remain untested in clinical populations [103,104]. These therapies remain exploratory in the absence of efficacy and safety data, and current translational focus continues to emphasize established agents with outcome trial evidence for secondary prevention.

5.2. Advanced Platforms (Nanozymes, CRISPR)

Nanozymes are engineered nanomaterials with intrinsic enzyme-mimetic activity, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, that scavenge ROS in ischemia–reperfusion injury, plaque destabilization, and adverse remodeling after ACS. By restoring redox balance, nanozymes suppress NF-κB signaling, limit inflammatory cell recruitment, and promote reparative macrophage polarization. Preclinical rodent and porcine studies demonstrate robust cardioprotection, with Fe-Cur@TA nanozymes achieving a tenfold increase in myocardial retention, reducing infarct size, improving LVEF by more than 10 percentage points, and attenuating cytokine release without toxicity [105,106]. Other platforms, including Prussian blue, PtIr bimetallic, and MnO2 nanozymes, have shown multi-enzyme activity, 30 to 40 percent reductions in infarct size and fibrosis, and improved microvascular density [107,108,109]. Ex vivo human cell studies confirm anti-inflammatory effects with more than 50 percent reductions in TNF-α, IL-1β, and NF-κB expression and minimal cytotoxicity, while large-animal safety assessments indicate favorable biocompatibility, although data on chronic exposure and drug–drug interactions remain limited [106]. No human clinical trials have yet been conducted. CRISPR-based therapeutics represent a fundamentally different approach, enabling permanent modification of pro-inflammatory or pro-remodeling genes such as TLR4, IL-1β, and CaMKIIδ. In preclinical models, CRISPR-mediated disruption of these targets reduces cytokine production, preserves myocardial function, and limits infarct expansion, with similar effects observed in ex vivo human cell editing [110,111,112]. Current cardiovascular CRISPR trials focus largely on lipid modulation, such as PCSK9 editing, rather than post-infarct inflammation, reflecting major translational barriers including targeted cardiac delivery, avoidance of off-target edits, immunogenicity of Cas proteins, and stringent regulatory thresholds for chronic, non-lethal conditions [113,114]. While nanozymes appear closer to clinical readiness, given their rapid, reversible pharmacologic effects and emerging safety data, CRISPR remains an early-stage platform requiring significant advances in delivery and safety before entering secondary prevention trials.

6. Discussion

Inflammation is central to ACS, orchestrating plaque progression, destabilization, rupture, and acute events. The interplay of innate and adaptive immunity, cytokines, chemokines, and pattern-recognition receptors drives both acute injury and long-term remodeling [1,2,3]. RIR has emerged as a modifiable determinant of recurrence, with biomarkers such as hsCRP, IL-6, leukocyte counts, and composite indices providing independent prognostic value. An early IL-6 surge followed by an hsCRP peak at about 48 h, especially if sustained after discharge, defines a high-risk phenotype [4,5,27].

Guidelines emphasize rapid initiation of therapy, highlighting statins as the foundation for combining lipid-lowering with pleiotropic anti-inflammatory effects. Low-dose colchicine at 0.5 mg daily offers the most proven adjunct, particularly for patients with hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L or high-risk comorbidities. Colchicine’s benefits, supported by consistent outcome reductions in COLCOT and LoDoCo2, likely extend beyond modest biomarker changes, reflecting effects on neutrophil trafficking, NLRP3 signaling, endothelial activation, and platelet–leukocyte interactions [8,9,10]. Cardiometabolic agents, including GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors, further reduce risk through overlapping metabolic and inflammatory pathways, strengthening their role in post-ACS care [13,75,84,115].

Targeting the cytokine axis strengthens causal inference but requires careful selection. In CANTOS, IL-1β blockade reduced recurrent events in proportion to IL-6 and hsCRP suppression, though safety and cost limited uptake [12,50]. Anakinra attenuates systemic inflammation with signals for heart failure prevention, whereas ziltivekimab drives marked reductions in hsCRP and IL-6 and is advancing in phase 3 [53,57]. Upstream approaches, including oral NLRP3 inhibition with dapansutrile and peri-procedural P-selectin antagonism with inclacumab, broaden the pipeline, though definitive outcome data remain pending [11,21].

Other strategies have failed in coronary disease, including methotrexate, lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 inhibitors, p38 MAPK inhibitors, and complement blockades, likely reflecting off-target effects or unselected populations. By contrast, therapies that suppress the IL-1 and IL-6 pathway in biomarker-enriched cohorts consistently reduce events [12,15,56].

Next-generation approaches remain preclinical. Nanozymes and cardiac-targeted platforms reduce oxidative stress and inflammation in animal models [106,116,117]. CRISPR-based modulation of TLR4 or CaMKIIδ is feasible ex vivo but is limited by in vivo delivery and safety. Parallel efforts explore NET inhibition, MPO blockades, and restoration of specialized pro-resolving mediators.

Practical hurdles remain, and real-world adoption is slowed by underuse of hsCRP and IL-6 testing, uncertain thresholds and duration of therapy, polypharmacy, and insurance barriers. Simple solutions may include routine hsCRP measurement at 4 to 12 weeks post-ACS, EHR-embedded prompts for colchicine initiation at hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L, pharmacist-led screening, and shared decision tools emphasizing absolute risk reduction. Practical implementation must also consider timing; similar to lipid-lowering strategies, where early initiation improves outcomes, anti-inflammatory therapy may require ultra-early initiation to maximize benefit, yet this remains untested in large trials [118]. For biologics, infection risk and cost currently outweigh benefit, with cost-effectiveness achieved only when targeted at extreme residual inflammatory risk.

7. Evidence Gaps and Future Directions

Despite advances in lipid-lowering and antithrombotic therapy, major gaps persist in the timing, duration, and personalization of inflammation- and metabolism-targeted strategies after ACS. Most randomized trials, including CANTOS, COLCOT, and LoDoCo2, initiated therapy days to weeks after the index event, well beyond the 3-to-7-day peak of inflammatory activity when NLRP3 activation, NETosis, endothelial dysfunction, and defective resolution are most modifiable [3,4,119]. A recent network meta-analysis of 23 randomized trials including 28,220 patients demonstrated that both colchicine and anakinra reduced major adverse cardiovascular events and heart failure events, respectively, but these benefits were observed only when therapy was initiated within 24 h of symptom onset [49]. No adequately powered trial has prospectively tested ultra-early initiation within 24 h in biomarker-selected ACS patients. Ongoing studies such as COCOMO-ACS (early colchicine guided by OCT-defined plaque phenotype) and ZEUS (ziltivekimab in high-risk CKD/ASCVD) aim to address this gap. Their rationale parallels contemporary lipid management, where prompt initiation of high-intensity statins and early PCSK9 inhibition lower LDL-C, attenuate vascular inflammation, and promote plaque stabilization [118]. Collectively, these strategies signal a convergent therapeutic paradigm that integrates lipid and immune modulation, emphasizing ultra-early intervention during the transient post-ACS inflammatory window when risk and therapeutic responsiveness are greatest.

The optimal duration of anti-inflammatory therapy after ACS remains uncertain. Canakinumab provided sustained benefit over 3.7 years in CANTOS but raised infection concerns. Post hoc COLCOT data suggest the benefit may wane after colchicine discontinuation, yet no trial has tested structured de-escalation or biomarker-guided withdrawal [45,120]. A treat-to-target approach remains untested. Although hsCRP and IL 6 identify residual inflammatory risk, thresholds, timing, and monitoring strategies are unclear [121,122].

Comorbidities shape inflammatory phenotypes and modulate therapeutic response. Diabetes promotes neutrophil-dominant inflammation and NETosis [88,123]. Chronic kidney disease amplifies IL-6-driven risk and increases susceptibility to ischemic and bleeding complications [124,125]. Autoimmune disease and frailty add further complexity, yet these high-risk groups remain underrepresented in trials [126,127].

Pooling heterogeneous ACS phenotypes obscures mechanistic insight. Rupture, erosion, calcified nodules, MINOCA, and SCAD differ in biology and therapeutic implications [28]. OCT-defined plaque erosion can be managed without stenting using intensive antithrombotic therapy, and potential benefit from anti-inflammatory therapy remains plausible but unproven [128,129]. MINOCA and SCAD, which disproportionately affect women, are still excluded from most anti-inflammatory outcome trials despite clear inflammatory components [7]. No trial has prospectively stratified therapy by mechanism. Ongoing studies such as COCOMO ACS are testing early colchicine with imaging-defined phenotypes [130]. Precision imaging tools such as FDG PET, OCT, and molecular profiling, including CHIP and NETosis high states, may enable phenotype-specific risk assessment and guide therapy selection but remain investigational [93,131].

Representation in cardiovascular trials must improve. Women comprise only 20–25 percent of trial cohorts despite sex-specific immune and plaque biology, while young patients, minorities, and those with obesity remain underrepresented [132]. Endpoints should expand beyond recurrent MI to include heart failure, atrial fibrillation, peripheral artery disease progression, microvascular dysfunction, renal decline, quality of life, and functional recovery. CANTOS suggested reductions in heart failure hospitalization, and anakinra lowered NT proBNP in high CRP ACS, supporting broader endpoints [50,54,133].

Combination or sequencing strategies such as colchicine plus GLP 1 receptor agonists or SGLT2 inhibitors are supported by observational data suggesting additive benefit, but no randomized controlled trials have directly tested these approaches in post-ACS care. Real-world data indicate that uptake of GLP 1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors after ACS remains suboptimal, with only a minority of eligible patients receiving both agents and even fewer receiving colchicine in addition [90,134]. Barriers include lack of direct evidence, cost, access, polypharmacy, and uncertainty in patient selection and sequencing [88,134]

Priorities for the next generation of trials include ultra-early initiation, biomarker-guided and imaging-based precision strategies, inclusion of diverse high-risk populations, and integration of metabolic, thrombotic, and inflammatory modulation. Programs such as ZEUS for ziltivekimab, SELECT for semaglutide, and COCOMO ACS for colchicine with mechanistic imaging are addressing key aspects, while SUMMIT extends the multidomain model to obesity-related HFpEF. Pragmatic implementation models, AI-driven phenotyping, and equity-focused trial design will be essential to translate these advances into routine care. Aligning inflammation-targeted therapy with precision medicine offers a credible path to reduce residual risk and improve long-term outcomes in ACS.

8. Conclusions

Residual inflammatory risk persists after ACS despite optimized lipid-lowering and antithrombotic therapy. Current evidence supports low-dose colchicine as an adjunct for secondary prevention, whereas cytokine- and inflammasome-targeted approaches remain investigational pending definitive phase 3 trials and clearer safety and cost profiles (summary Table 4). The field remains in the early stages of defining the optimal anti-inflammatory strategy, including agent selection, timing and duration, and biomarker-guided treat-to-target using hsCRP and IL-6, with attention to phenotype and comorbidity. Priorities include adequately powered, mechanism-aware trials, pragmatic pathways for equitable implementation, and integration with cardiometabolic therapies.

Table 4.

Anti-inflammatory therapies in secondary prevention after ACS: Summary of agents targeting inflammation and metabolism in post-ACS care. Colchicine is FDA-approved for ASCVD; canakinumab, anakinra, tocilizumab, and ziltivekimab demonstrate biologic activity but lack regulatory approval. GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors provide cardiometabolic benefit and are guideline-endorsed in ASCVD with type 2 diabetes, with ongoing trials post-ACS. Prior agents, including varespladib, darapladib, losmapimod, and pexelizumab, were neutral or harmful. Emerging strategies, including oral NLRP3 inhibition, P-selectin blockade, JAK/STAT and BTK inhibitors, CRISPR-based therapies, and nanozymes, remain exploratory and unproven in outcomes studies.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article as it is based entirely on previously published literature.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rao, S.V.; O’Donoghue, M.L.; Ruel, M.; Rab, T.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Alexander, J.H.; Baber, U.; Baker, H.; Cohen, M.G.; Cruz-Ruiz, M.; et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2025, 151, e771–e862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. Inflammation during the life cycle of the atherosclerotic plaque. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 2525–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingenberg, R.; Aghlmandi, S.; Gencer, B.; Nanchen, D.; Räber, L.; Carballo, D.; Carballo, S.; Stähli, B.E.; Landmesser, U.; Rodondi, N.; et al. Residual inflammatory risk at 12 months after acute coronary syndromes is frequent and associated with combined adverse events. Atherosclerosis 2021, 320, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Glynn, R.J.; Bradwin, G.; Hasan, A.A.; Rifai, N. Comparison of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol as biomarkers of residual risk in contemporary practice: Secondary analyses from the cardiovascular inflammation reduction trial. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2952–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Qiu, M.; Su, X.; Qi, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Xu, K.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; et al. The residual risk of inflammation and remnant cholesterol in acute coronary syndrome patients on statin treatment undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraler, S.; Mueller, C.; Libby, P.; Bhatt, D.L. Acute coronary syndromes: Mechanisms, challenges, and new opportunities. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 2866–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tardif, J.-C.; Kouz, S.; Waters, D.D.; Bertrand, O.F.; Diaz, R.; Maggioni, A.P.; Pinto, F.J.; Ibrahim, R.; Gamra, H.; Kiwan, G.S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Low-Dose Colchicine after Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2497–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nidorf, S.M.; Fiolet, A.T.L.; Mosterd, A.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Schut, A.; Opstal, T.S.J.; The, S.H.K.; Xu, X.-F.; Ireland, M.A.; Lenderink, T.; et al. Colchicine in Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1838–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.; Fuster, V.; Ridker, P.M. Low-Dose Colchicine for Secondary Prevention of Coronary Artery Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klück, V.; Jansen, T.L.T.A.; Janssen, M.; Comarniceanu, A.; Efdé, M.; Tengesdal, I.W.; Schraa, K.; Cleophas, M.C.P.; Scribner, C.L.; Skouras, D.B.; et al. Dapansutrile, an oral selective NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor, for treatment of gout flares: An open-label, dose-adaptive, proof-of-concept, phase 2a trial. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020, 2, e270–e280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Everett, B.M.; Thuren, T.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Chang, W.H.; Ballantyne, C.; Fonseca, F.; Nicolau, J.; Koenig, W.; Anker, S.D.; et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoff, A.M.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Colhoun, H.M.; Deanfield, J.; Emerson, S.S.; Esbjerg, S.; Hardt-Lindberg, S.; Hovingh, G.K.; Kahn, S.E.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2221–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braunwald, E. Gliflozins in the Management of Cardiovascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2024–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; Devalaraja, M.; Baeres, F.M.M.; Engelmann, M.D.M.; Hovingh, G.K.; Ivkovic, M.; Lo, L.; Kling, D.; Pergola, P.; Raj, D.; et al. IL-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab in patients at high atherosclerotic risk (RESCUE): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 2060–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, P. Mechanisms of Acute Coronary Syndromes and Their Implications for Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 2004–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Habenicht, A.J.R.; Von Hundelshausen, P. Novel mechanisms and therapeutic targets in atherosclerosis: Inflammation and beyond. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 2672–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahara, N.; Kai, H.; Ishibashi, M.; Nakaura, H.; Kaida, H.; Baba, K.; Hayabuchi, N.; Imaizumi, T. Simvastatin Attenuates Plaque Inflammation. Evaluation by Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 48, 1825–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Sipahi, I.; Grasso, A.W.; Schoenhagen, P.; Hu, T.; Wolski, K.; Crowe, T.; Desai, M.Y.; Hazen, S.L.; et al. Statins, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and regression of coronary atherosclerosis. JAMA 2007, 297, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, Y.; Libby, P.; Soehnlein, O. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Participate in Cardiovascular Diseases: Recent Experimental and Clinical Insights. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1228–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardif, J.-C.; Tanguay, J.-F.; Wright, S.R.; Duchatelle, V.; Petroni, T.; Grégoire, J.C.; Ibrahim, R.; Heinonen, T.M.; Robb, S.; Bertrand, O.F.; et al. Effects of the P-selectin antagonist inclacumab on myocardial damage after percutaneous coronary intervention for non-st-segment elevation myocardial infarction: Results of the SELECT-ACS trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 2048–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchatelle, V.; L’Allier, P.; Tanguay, J.F.; Petroni, T.; Robb, S.; Johnson, D.; Cournoyer, D.; Guertin, M.C.; Wright, S.; Tardif, J.C. Effects of the P-selectin antagonist inclacumab on myocardial damage according to the time interval between infusion and percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Li, H.; Tang, Y.; Yao, P. Potential Mechanisms and Effects of Efferocytosis in Atherosclerosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 11, 585285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergallo, R.; Crea, F. Atherosclerotic Plaque Healing. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahed, A.C.; Jang, I.K. Plaque erosion and acute coronary syndromes: Phenotype, molecular characteristics and future directions. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meteva, D.; Vinci, R.; Seppelt, C.; Abdelwahed, Y.S.; Pedicino, D.; Nelles, G.; Skurk, C.; Haghikia, A.; Rauch-Kröhnert, U.; Gerhardt, T.; et al. Toll-like receptor 2, hyaluronan, and neutrophils play a key role in plaque erosion: The OPTICO-ACS study. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3892–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebetrau, C.; Hoffmann, J.; Dörr, O.; Gaede, L.; Blumenstein, J.; Biermann, H.; Pyttel, L.; Thiele, P.; Troidl, C.; Berkowitsch, A.; et al. Release kinetics of inflammatory biomarkers in a clinical model of acute myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P.H.; Libby, P.; Boden, W.E. Fundamental Pathobiology of Coronary Atherosclerosis and Clinical Implications for Chronic Ischemic Heart Disease Management—The Plaque Hypothesis: A Narrative Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkel, S.J.; Wolters, F.J.; Ikram, M.A.; de Maat, M.P.M. Circulating Myeloperoxidase (MPO)-DNA complexes as marker for Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) levels and the association with cardiovascular risk factors in the general population. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Ridker, P.M. Inflammation and Atherothrombosis. From Population Biology and Bench Research to Clinical Practice. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 48, A33–A46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Yang, S.; Chen, R.; Sheng, Z.; Zhou, P.; Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Song, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; et al. High Plasma Myeloperoxidase Is Associated with Plaque Erosion in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2020, 13, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henein, M.Y.; Vancheri, S.; Longo, G.; Vancheri, F. The Role of Inflammation in Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Hou, L.; Luo, W.; Pan, L.-H.; Li, X.; Tan, H.-P.; Wu, R.-D.; Lu, H.; Yao, K.; Mu, M.-D.; et al. Myocardial infarction drives trained immunity of monocytes, accelerating atherosclerosis. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moissl, A.P.; Delgado, G.E.; Scharnagl, H.; Siekmeier, R.; Krämer, B.K.; Duerschmied, D.; März, W.; Kleber, M.E. Comparing Inflammatory Biomarkers in Cardiovascular Disease: Insights from the LURIC Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; Moorthy, M.V.; Cook, N.R.; Rifai, N.; Lee, I.-M.; Buring, J.E. Inflammation, Cholesterol, Lipoprotein(a), and 30-Year Cardiovascular Outcomes in Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 2087–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Figtree, G.A.; Moorthy, M.V.; Mora, S.; Buring, J.E. C-reactive protein and cardiovascular risk among women with no standard modifiable risk factors: Evaluating the ‘SMuRF-less but inflamed’. Eur. Heart J. 2025, ehaf658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raynor, W.Y.; Park, P.S.U.; Borja, A.J.; Sun, Y.; Werner, T.J.; Ng, S.J.; Lau, H.C.; Høilund-Carlsen, P.F.; Alavi, A.; Revheim, M.-E. PET-based imaging with 18F-FDG and 18F-NaF to assess inflammation and microcalcification in atherosclerosis and other vascular and thrombotic disorders. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, C.P.; Blazing, M.A.; Giugliano, R.P.; McCagg, A.; White, J.A.; Théroux, P.; Darius, H.; Lewis, B.S.; Ophuis, T.O.; Jukema, J.W.; et al. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2387–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohula, E.A.; Giugliano, R.P.; Leiter, L.A.; Verma, S.; Park, J.-G.; Sever, P.S.; Pineda, A.L.; Honarpour, N.; Wang, H.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Inflammatory and cholesterol risk in the FOURIER trial. Circulation 2018, 138, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Steg, P.G.; Szarek, M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Bittner, V.A.; Diaz, R.; Edelberg, J.M.; Goodman, S.G.; Hanotin, C.; Harrington, R.A.; et al. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2097–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3415–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.T.; Lee, Y.H.; Wei, J.C.C. Colchicine in Cardiovascular Disease: Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2025, 28, e70081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulnes, J.F.; González, L.; Velásquez, L.; Orellana, M.P.; Venturelli, P.M.; Martínez, G. Role of inflammation and evidence for the use of colchicine in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1356023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouabdallaoui, N.; Tardif, J.-C.; Waters, D.D.; Pinto, F.J.; Maggioni, A.P.; Diaz, R.; Berry, C.; Koenig, W.; Lopez-Sendon, J.; Gamra, H.; et al. Time-to-treatment initiation of colchicine and cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction in the Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT). Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 4092–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, S.S.; D’Entremont, M.-A.; Lee, S.F.; Mian, R.; Tyrwhitt, J.; Kedev, S.; Montalescot, G.; Cornel, J.H.; Stanković, G.; Moreno, R.; et al. Colchicine in Acute Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.; Yang, K.C.K.; Atkins, K.; Dalbeth, N.; Robinson, P.C. Adverse events during oral colchicine use: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2020, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajek, S.; Michalak, M.; Urbanowicz, T.; Olasińska-Wiśniewska, A. A Meta-Analysis Evaluating the Colchicine Therapy in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 740896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsippany, N.J. U.S. FDA Approves First Anti-Inflammatory Drug for Cardiovascular Disease; Business Wire: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Laudani, C.; Occhipinti, G.; Greco, A.; Giacoppo, D.; Spagnolo, M.; Capodanno, D. A pairwise and network meta-analysis of anti-inflammatory strategies after myocardial infarction: The TITIAN study. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2025, 11, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Everett, B.M.; Libby, P.; Thuren, T.; Glynn, R.J.; Kastelein, J.; Koenig, W.; Genest, J.; Lorenzatti, A.; et al. Relationship of C-reactive protein reduction to cardiovascular event reduction following treatment with canakinumab: A secondary analysis from the CANTOS randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehested, T.S.G.; Bjerre, J.; Ku, S.; Chang, A.; Jahansouz, A.; Owens, D.K.; Hlatky, M.A.; Goldhaber-Fiebert, J.D. Cost-effectiveness of Canakinumab for Prevention of Recurrent Cardiovascular Events. JAMA Cardiol. 2019, 4, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullard, A. Anti-inflammatory cardiovascular therapies take another hit. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, A.; Trankle, C.R.; Buckley, L.F.; Lipinski, M.J.; Appleton, D.; Kadariya, D.; Canada, J.M.; Carbone, S.; Roberts, C.S.; Abouzaki, N.; et al. Interleukin-1 Blockade Inhibits the Acute Inflammatory Response in Patients with ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e014941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbate, A.; Wohlford, G.F.; Del Buono, M.G.; Chiabrando, J.G.; Markley, R.; Turlington, J.; Kadariya, D.; Trankle, C.R.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Lipinski, M.J.; et al. Interleukin-1 blockade with anakinra and heart failure following ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: Results from a pooled analysis of the VCUART clinical trials. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2022, 8, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Carvajal, A.J.; Gemmato-Valecillos, M.A.; Martín, D.M.; Dayer, M.; Alegría-Barrero, E.; De Sanctis, J.B.; Vasco, J.M.P.; Lizardo, R.J.R.; Nicola, S.; Martí-Amarista, C.E.; et al. Interleukin-receptor antagonist and tumour necrosis factor inhibitors for the primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 2024, CD014741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Rane, M. Interleukin-6 Signaling and Anti-Interleukin-6 Therapeutics in Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1728–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamstein, N.H.; Cornel, J.H.; Davidson, M.; Libby, P.; de Remigis, A.; Jensen, C.; Ekström, K.; Ridker, P.M. Association of Interleukin 6 Inhibition with Ziltivekimab and the Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio: A Secondary Analysis of the RESCUE Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euctr, G.R. ZEUS—A Research Study to Look at How Ziltivekimab Works Compared to Placebo in People with Cardiovascular Disease, Chronic Kidney Disease and Inflammation. 2021. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-02329117/full (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Broch, K.; Anstensrud, A.K.; Woxholt, S.; Sharma, K.; Tøllefsen, I.M.; Bendz, B.; Aakhus, S.; Ueland, T.; Amundsen, B.H.; Damås, J.K.; et al. Randomized Trial of Interleukin-6 Receptor Inhibition in Patients with Acute ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, T.; Klück, V.; Janssen, M.; Comarniceanu, A.; Efdé, M.; Scribner, C.; Barrow, R.; Skouras, D.; Dinarello, C.; Joosten, L. The first phase 2A proof of concept study of a selective NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor, dapansutrile (OLT1177), in acute gout. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 78, A70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, T.; Piscitelli, P.; Barrow, C.; Vought, K.; Poshusta, A.; Kapushoc, H.; Leonard-Segal, A.; Noor, M.; Skouras, D.; Dinarello, C.; et al. Rationale and design for PODAGRA II: Dapansutrile in acute gout flare. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinarello, C.A.; Simon, A.; van der Meer, J.W. Treating inflammation by blocking interleukin-1 in a broad spectrum of diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 633–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Everett, B.M.; Pradhan, A.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Solomon, D.H.; Zaharris, E.; Mam, V.; Hasan, A.; Rosenberg, Y.; Iturriaga, E.; et al. Low-Dose Methotrexate for the Prevention of Atherosclerotic Events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; Schwartz, G.G.; Bash, D.; Rosenson, R.S.; Cavender, M.A.; Brennan, D.M.; Koenig, W.; Jukema, J.W.; Nambi, V.; et al. Varespladib and cardiovascular events in patients with an acute coronary syndrome: The VISTA-16 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014, 311, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’donoghue, M.L.; Glaser, R.; Cavender, M.A.; Aylward, P.E.; Bonaca, M.P.; Budaj, A.; Davies, R.Y.; Dellborg, M.; Fox, K.A.A.; Gutierrez, J.A.T.; et al. Effect of losmapimod on cardiovascular outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016, 315, 1591–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, M.L.; Braunwald, E.; White, H.D.; Steen, D.P.; Lukas, M.A.; Tarka, E.; Steg, P.G.; Hochman, J.S.; Bode, C.; Maggioni, A.P.; et al. Effect of darapladib on major coronary events after an acute coronary syndrome: The SOLID-TIMI 52 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014, 312, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.B.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Weaver, W.D.; Theroux, P.; Hochman, J.S.; Filloon, T.G.; Rollins, S.; Todaro, T.G.; Nicolau, J.C.; Ruzyllo, W.; et al. Pexelizumab, an anti-C5 complement antibody, as adjunctive therapy to primary percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction: The COMplement inhibition in Myocardial infarction treated with Angioplasty (COMMA) trial. Circulation 2003, 108, 1184–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; Shernan, S.K.; Chen, J.C.; Carrier, M.; Verrier, E.D.; Adams, P.X.; Todaro, T.G.; Muhlbaier, L.H.; Levy, J.H. Effects of C5 complement inhibitor pexelizumab on outcome in high-risk coronary artery bypass grafting: Combined results from the PRIMO-CABG i and II trials. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 142, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.M.; Petrie, M.C.; McMurray, J.J.; Sattar, N. How Do SGLT2 (Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2) Inhibitors and GLP-1 (Glucagon-Like Peptide-1) Receptor Agonists Reduce Cardiovascular Outcomes?: Completed and Ongoing Mechanistic Trials. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 506–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakkar, N.M.Z.; AlZaim, I.; El-Yazbi, A.F. Depot-specific adipose tissue modulation by SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP1 agonists mediates their cardioprotective effects in metabolic disease. Clin. Sci. 2022, 136, 1631–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, S.V.; Bhatt, D.L.; Barsness, G.W.; Beatty, A.L.; Deedwania, P.C.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.; Leiter, L.A.; Lipska, K.J.; Newman, J.D.; et al. Clinical Management of Stable Coronary Artery Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, E779–E806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, J.J.; Deedwania, P.; Acharya, T.; Aguilar, D.; Bhatt, D.L.; Chyun, D.A.; Di Palo, K.E.; Golden, S.H.; Sperling, L.S.; American Heart Association Diabetes Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; et al. Comprehensive Management of Cardiovascular Risk Factors for Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, 722–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauck, M.A.; Meier, J.J.; Cavender, M.A.; El Aziz, M.A.; Drucker, D.J. Cardiovascular actions and clinical outcomes with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Circulation 2017, 136, 849–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.S.P.; Hsu, J.T.Y.; Chong, S.K.S.; Quek, J.; Shek, G.; Sulaimi, F.; Chan, K.E.; Anand, V.V.; Chong, B.; Mehta, A.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist in myocardial infarction and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk reduction: A comprehensive meta-analysis of number needed to treat, efficacy and safety. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandy, S.; Shaunik, A. Effects of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists on β-Cell Function in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Metab. 2015, 7, 3346–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marso, S.P.; Bain, S.C.; Consoli, A.; Eliaschewitz, F.G.; Jódar, E.; Leiter, L.A.; Lingvay, I.; Rosenstock, J.; Seufert, J.; Warren, M.L.; et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in Patients type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN-6). N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1834–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstein, H.C.; Colhoun, H.M.; Dagenais, G.R.; Diaz, R.; Lakshmanan, M.; Pais, P.; Probstfield, J.; Riesmeyer, J.S.; Riddle, M.C.; Rydén, L.; et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes (REWIND). Lancet 2019, 394, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marso, S.P.; Daniels, G.H.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Kristensen, P.; Mann, J.F.E.; Nauck, M.A.; Nissen, S.E.; Pocock, S.; Poulter, N.R.; Ravn, L.S.; et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (LEADER). N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, J.B.; Bain, S.C.; Mann, J.F.; Nauck, M.A.; Nissen, S.E.; Pocock, S.; Poulter, N.R.; Pratley, R.E.; Linder, M.; Fries, T.M.; et al. Cardiovascular Risk Reduction with Liraglutide: An Exploratory Mediation Analysis of the LEADER Trial. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 1546–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sghayyer, M.; Saleem, D.; Abu Daya, H. OR3-2|GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Use in Patients with Type II Diabetes After Acute Myocardial Infarction and PCI: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2025, 4, 102704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyan-Ashraf, M.H.; Momen, M.A.; Ban, K.; Sadi, A.-M.; Zhou, Y.-Q.; Riazi, A.M.; Baggio, L.L.; Henkelman, R.M.; Husain, M.; Drucker, D.J. GLP-1R agonist liraglutide activates cytoprotective pathways and improves outcomes after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Diabetes 2009, 58, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Qin, D.; Wang, Y.; Xue, L.; Qin, Y.; Xu, X. The effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors on cardiorespiratory fitness capacity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 2023, 13, 1045235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.M.; Kang, Y.M.; Im, K.; Neuen, B.L.; Anker, S.D.; Bhatt, D.L.; Butler, J.; Cherney, D.Z.; Claggett, B.L.; Fletcher, R.A.; et al. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes: A SMART-C Collaborative Meta-Analysis. Circulation 2024, 149, 1789–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinman, B.; Wanner, C.; Lachin, J.M.; Fitchett, D.; Bluhmki, E.; Hantel, S.; Mattheus, M.; Devins, T.; Johansen, O.E.; Woerle, H.J.; et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes (EMPA-REG OUTCOME). N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; Jones, W.S.; Udell, J.A.; Anker, S.D.; Petrie, M.C.; Harrington, J.; Mattheus, M.; Zwiener, I.; Amir, O.; Bahit, M.C.; et al. Empagliflozin after Acute Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1455–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asham, H.; Ghaffari, S.; Taban-Sadeghi, M.; Entezari-Maleki, T. Efficacy and Safety of SGLT-2 Inhibitors in Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2025, 65, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Chan, Y.; Hsu, T.; Chuang, C.; Li, P.; Yeh, Y.; Su, H.; Hsiao, F.; See, L. Clinical Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes Patients After Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Comparison of Sodium–Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors vs. Non-Users. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 116, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Chow, S.L.; Mathew, R.O.; Khan, S.S.; Coresh, J.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; Després, J.-P.; et al. A Synopsis of the Evidence for the Science and Clinical Management of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Syndrome: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1636–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms-Williams, N.; Treves, N.; Yin, H.; Lu, S.; Yu, O.; Pradhan, R.; Renoux, C.; Suissa, S.; Azoulay, L. Effect of combination treatment with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors on incidence of cardiovascular and serious renal events: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2024, 385, e078242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marfella, R.; Prattichizzo, F.; Sardu, C.; Rambaldi, P.F.; Fumagalli, C.; Marfella, L.V.; La Grotta, R.; Frigé, C.; Pellegrini, V.; D’andrea, D.; et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists-SGLT-2 inhibitors combination therapy and cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction: An observational study in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.I.; Marquina, C.; Shaw, J.E.; Liew, D.; Polkinghorne, K.R.; Ademi, Z.; Magliano, D.J. Projecting the incidence and costs of major cardiovascular and kidney complications of type 2 diabetes with widespread SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA use: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Diabetologia 2022, 66, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virani, S.S.; Newby, L.K.; Arnold, S.V.; Bittner, V.; Brewer, L.C.; Demeter, S.H.; Dixon, D.L.; Fearon, W.F.; Hess, B.; Johnson, H.M.; et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2023, 148, E9–E119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverio, A.; Cancro, F.P.; Esposito, L.; Bellino, M.; D’elia, D.; Verdoia, M.; Vassallo, M.G.; Ciccarelli, M.; Vecchione, C.; Galasso, G.; et al. Secondary Cardiovascular Prevention after Acute Coronary Syndrome: Emerging Risk Factors and Novel Therapeutic Targets. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, A.; Sukhi, A.; Chaudhary, R.; Bliden, K.P.; Tantry, U.S.; Gurbel, P.A. Investigational drugs in phase II clinical trials for acute coronary syndromes. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2020, 29, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaba, M.; Iwaki, T.; Arakawa, T.; Ono, T.; Maekawa, Y.; Umemura, K. Dasatinib suppresses atherosclerotic lesions by suppressing cholesterol uptake in a mouse model of hypercholesterolemia. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 149, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saglio, G.; le Coutre, P.; Cortes, J.; Mayer, J.; Rowlings, P.; Mahon, F.-X.; Kroog, G.; Gooden, K.; Subar, M.; Shah, N.P. Evaluation of cardiovascular ischemic event rates in dasatinib-treated patients using standardized incidence ratios. Ann. Hematol. 2017, 96, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, M.R.; Xiao, L.; Jackson, K.D.; Beckman, J.A.; Barac, A.; Moslehi, J.J. Vascular Impact of Cancer Therapies: The Case of BTK (Bruton Tyrosine Kinase) Inhibitors. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1973–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proskuriakova, E.; Shrestha, D.B.; Jasaraj, R.; Reddy, V.K.; Shtembari, J.; Raut, A.; Gaire, S.; Khosla, P.; Kadariya, D. Cardiovascular Adverse Events Associated with Second-generation Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2024, 46, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]