Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Insulin Dose and Route of Administration Regimens for Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Children and Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration and Guidelines

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Outcomes

- Morbidity:

- Cerebral injury was assessed using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) or deterioration in neurological status.

- Hypoglycemia was defined according to varying glucose thresholds.

- Hypokalemia was defined according to varying serum potassium levels.

- Overall morbidity was defined as a composite of cerebral injury, hypoglycemia, and hypokalemia.

- All-cause mortality represented the total number of deaths during the study period.

- Length of hospital stay measured in hours or days.

- Adverse events were defined as any complications during treatment other than hypoglycemia, hypokalemia, and cerebral injury, as reported by study authors.

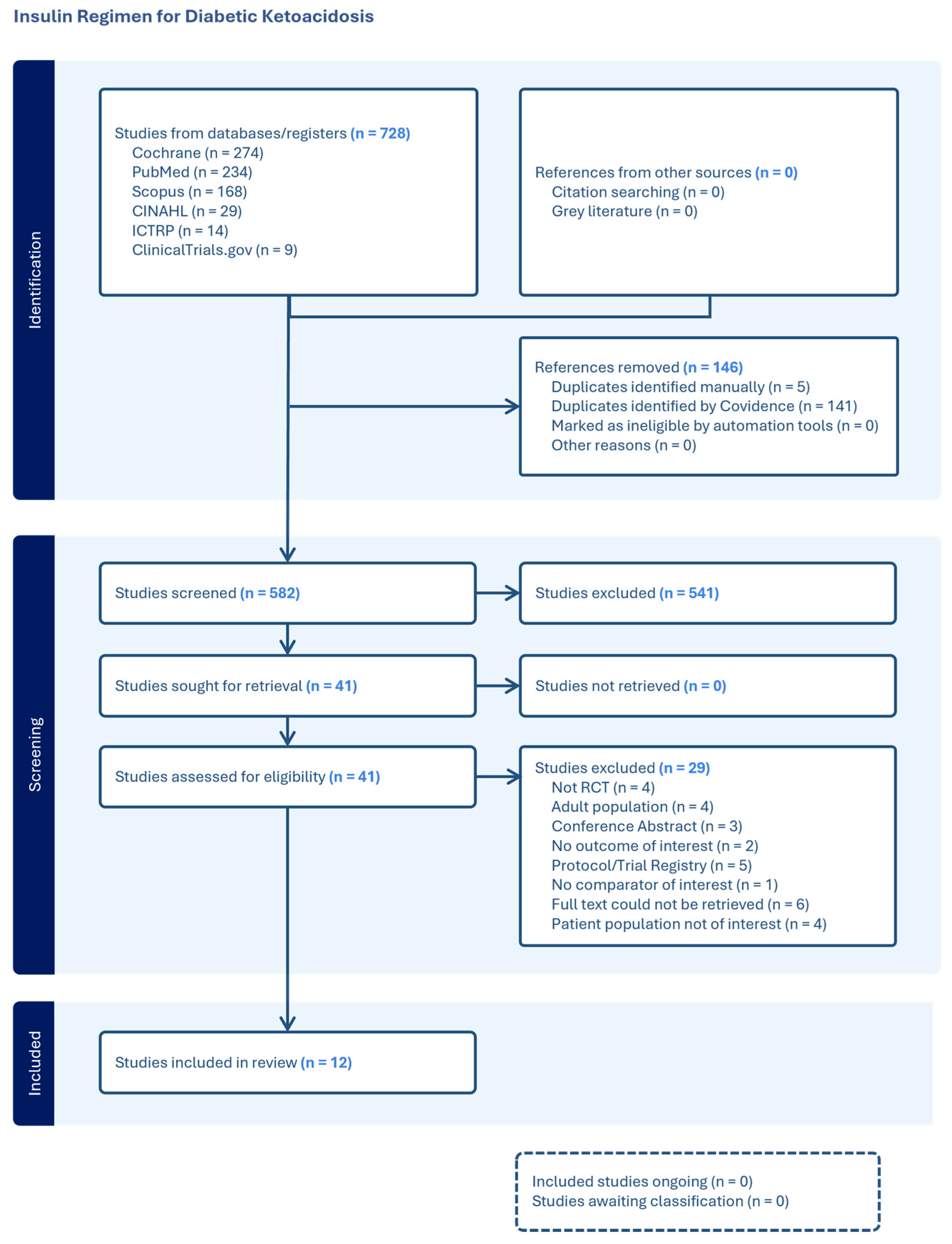

2.4. Search Methods

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

2.5.1. Selection of Studies

2.5.2. Data Extraction and Management

2.6. Quality Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Assessment of Heterogeneity

2.9. Certainty of Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Intervention and Therapeutic Approaches

3.3. Risk of Bias

3.4. Comparisons Identified for Analysis

- 0.05–0.1 U/kg/h IV + 0.5 U/kg SC versus 0.05–0.1 U/kg/h IV [31];

- 0.1 U/kg/2 h IM vs. 1.0 U/kg/4 h SC + IV [27];

- 0.1 U/kg/h IV vs. 1.0 U/kg/h IV [21];

- 0.1 U/kg/h IV vs. 1.0–2.2 U/kg SC every 3 h [24];

- 0.25 U/kg IV bolus + 0.1 U/kg/h IV vs. 2.0 U/kg IV + SC [28];

- 0.1 U/kg/h IV vs. 0.9–1.8 U/kg/h IV + SC [23];

- 0.1 U/kg/h IV with bolus dose vs. 0.1 U/kg/h IV without bolus dose [25].

3.5. Outcomes

3.5.1. Morbidity: Cerebral Injury, Hypoglycemia, and Hypokalemia

3.5.2. Mortality

3.5.3. Hospital Stay

3.5.4. Adverse Events

3.6. Certainty of Evidence (GRADE)

4. Discussion

Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kostopoulou, E.; Sinopidis, X.; Fouzas, S.; Gkentzi, D.; Dassios, T.; Roupakias, S.; Dimitriou, G. Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Children and Adolescents; Diagnostic and Therapeutic Pitfalls. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, N.A.; Levitsky, L.L. Management of diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Drugs 2008, 10, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, P.; Suresh, S. Delayed diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis in children—A cause for concern. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2015, 35, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, L.; Tuffaha, M.; Koren, D.; Levitsky, L.L. Management of Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Pediatr. Drugs 2020, 22, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhatariya, K.K.; Glaser, N.S.; Codner, E.; Umpierrez, G.E. Diabetic ketoacidosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umpierrez, G.; Korytkowski, M. Diabetic emergencies—Ketoacidosis, hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state and hypoglycaemia. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzi, L.; Barrett, E.J.; Groop, L.C.; Ferrannini, E.; DeFronzo, R.A. Metabolic effects of low-dose insulin therapy on glucose metabolism in diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes 1988, 37, 1470–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, O.E.; Licht, J.H.; Sapir, D.G. Renal function and effects of partial rehydration during diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes 1981, 30, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldhäusl, W.; Kleinberger, G.; Korn, A.; Dudczak, R.; Bratusch-Marrain, P.; Nowotny, P. Severe hyperglycemia: Effects of rehydration on endocrine derangements and blood glucose concentration. Diabetes 1979, 28, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K. Diabetic ketoacidosis: Update on management. Clin. Med. 2019, 19, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danne, T.; Phillip, M.; Buckingham, B.A.; Jarosz-Chobot, P.; Saboo, B.; Urakami, T.; Battelino, T.; Hanas, R.; Codner, E. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Insulin treatment in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19 (Suppl. 27), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heddy, N. Guideline for the management of children and young people under the age of 18 years with diabetic ketoacidosis (British Society for Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes). Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 2021, 106, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitabchi, A.E. Low-dose insulin therapy in diabetic ketoacidosis: Fact or fiction? Diabetes Metab. Rev. 1989, 5, 337–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfsdorf, J.; Glaser, N.; Sperling, M.A. Diabetic ketoacidosis in infants, children, and adolescents: A consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1150–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, N.G.; Fitzgerald, M.G.; Wright, A.D.; Malins, J.M. Comparative study of different insulin regimens in management of diabetic ketoacidosis. Lancet 1975, 306, 1221–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.; Leibovitz, N.; Shilo, S.; Zuckerman-Levin, N.; Shavit, I.; Shehadeh, N. Subcutaneous regular insulin for the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis in children. Pediatr. Diabetes 2017, 18, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunger, D.B.; Sperling, M.A.; Acerini, C.L.; Bohn, D.J.; Daneman, D.; Danne, T.P.; Glaser, N.S.; Hanas, R.; Hintz, R.L.; Levitsky, L.L.; et al. European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology/Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society consensus statement on diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2004, 113, e133–e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; White, I.R.; Anzures-Cabrera, J. Meta-analysis of skewed data: Combining results reported on log-transformed or raw scales. Stat. Med. 2008, 27, 6072–6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Schünemann, H.J.; Tugwell, P.; Knottnerus, A. GRADE guidelines: A new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghen, G.A.; Etteldorf, J.N.; Fisher, J.N.; Kitabchi, A.Q. Comparison of high-dose and low-dose insulin by continuous intravenous infusion in the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis in children. Diabetes Care 1980, 3, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Manna, T.; Steinmetz, L.; Campos, P.R.; Farhat, S.C.; Schvartsman, C.; Kuperman, H.; Setian, N.; Damiani, D. Subcutaneous use of a fast-acting insulin analog: An alternative treatment for pediatric patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 1856–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drop, S.L.S.; Duval-Arnould, B.J.M.; Gober, A.E.; Hersh, J.H.; Mcenery, P.T.; Knowles, H.C. Low-Dose Intravenous Insulin Infusion Versus Subcutaneous Insulin Injection: A Controlled Comparative Study of Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Pediatrics 1977, 59, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, G.A.; Kohaut, E.C.; Wehring, B.; Hill, L.L. Effectiveness of low-dose continuous intravenous insulin infusion in diabetic ketoacidosis. A prospective comparative study. J. Pediatr. 1977, 91, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, R.; Bolte, R.G. The use of an insulin bolus in low-dose insulin infusion for pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 1989, 5, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nallasamy, K.; Jayashree, M.; Singhi, S.; Bansal, A. Low-dose vs standard-dose insulin in pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014, 168, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onur, K.; Lala, V.R.; Juan, C.S.; AvRuskin, T.W. Glucagon suppression with low-dose intramuscular insulin therapy in diabetic ketoacidosis. J. Pediatr. 1979, 94, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkin, R.M.; Marks, J.F. Low-dose continuous intravenous insulin infusion in childhood diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin. Pediatr. 1979, 18, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rameshkumar, R.; Satheesh, P.; Jain, P.; Anbazhagan, J.; Abraham, S.; Subramani, S.; Parameswaran, N.; Mahadevan, S. Low-Dose (0.05 Unit/kg/hour) vs Standard-Dose (0.1 Unit/kg/hour) Insulin in the Management of Pediatric Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Trial. Indian Pediatr. 2021, 58, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, Z.; Maher, S.; Fredmal, J. Comparison of subcutaneous insulin aspart and intravenous regular insulin for the treatment of mild and moderate diabetic ketoacidosis in pediatric patients. Endocrine 2018, 61, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffari, F.; Homaei, A.; Chegini, V.; Javadi, A.; Chegini, V. Evaluation of the Effects of Incorporating Long-Acting Subcutaneous Insulin Into the Standard Treatment Protocol for Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Children. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 22, e139684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, D.; Mittal, M.; Kanakaraju, C.; Dhingra, D.; Kumar, M. Efficacy and Safety of Low Dose Insulin Infusion against Standard Dose Insulin Infusion in Children with Diabetic Ketoacidosis- An Open Labelled Randomized Controlled Trial. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 26, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belal, M.M.; Khalefa, B.B.; Rabea, E.M.; Aly Yassin, M.N.; Bashir, M.N.; Abd El-Hameed, M.M.; Elkoumi, O.; Saad, S.M.; Saad, L.M.; Elkasaby, M.H. Low dose insulin infusion versus the standard dose in children with diabetic ketoacidosis: A meta-analysis. Future Sci. OA 2024, 10, FSO956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestell, B.; Battaglia, F.; Sharif, S.; Eltorki, M.; Samaan, M.C.; Choong, K.; Rochwerg, B. Insulin Infusion Dosing in Pediatric Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Crit. Care Explor. 2023, 5, e0857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, N.; Fritsch, M.; Priyambada, L.; Rewers, A.; Cherubini, V.; Estrada, S.; Wolfsdorf, J.I.; Codner, E. ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2022: Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 835–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umpierrez, G.E.; Latif, K.; Stoever, J.; Cuervo, R.; Park, L.; Freire, A.X.; Kitabchi, A.E. Efficacy of subcutaneous insulin lispro versus continuous intravenous regular insulin for the treatment of patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. Am. J. Med. 2004, 117, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, I.B. Insulin analogues. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texas Children’s Hospital. Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) Clinical Guideline; Evidence-Based Outcomes Center, Texas Children’s Hospital: Houston, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Inclusion Criteria | |

| Population: Children and adolescents with a confirmed diagnosis of DKA, with or without signs of shock, age 1–19 years, and with T1DM only | |

| Setting: Low-, middle-, and high-income countries. | |

| Study design: Randomized Controlled Trials | |

| Type of Interventions: | |

| |

| Subgroup dosing with rapid-acting vs. short-acting | |

| Types of comparator/control: | |

| |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Population: | |

| |

| Study design: Case reports, case series, cross-sectional, case–control, cohort studies, opinions, editorials, conference abstracts, reviews, and systematic reviews. | |

| Studies that do not report clinical outcomes (e.g., morbidity, mortality, adverse events, and length of hospital stay). Studies including only highly selected groups—such as children being treated with high-dose corticosteroids or receiving chemotherapy were excluded. | |

| Study | Country | Blinding | Age Range | Sample Size | Gender Intervention (%) | Gender Control (%) | Outcomes Reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Burghen, 1980] [21] | USA | Open label | 6.2 Y–15.8 Y | 32 | N/A | Morbidity (hypoglycemia, hypokalemia), mortality | |

| [Saffari, 2024] [31] | Iran | Open label | 2 Y–15 Y | 108 | M = 41.7 | M = 58.3 | Morbidity (cerebral edema, hypoglycemia, hypokalemia), hospital stay |

| F= 58.3 | F = 41.7 | ||||||

| [Della Manna, 2005] [22] | Brazil | Open label | 3 Y–18 Y | 60 | M = 32 | M = 23.8 F = 76.2 | Morbidity (cerebral edema, hypoglycemia, hypokalemia), mortality, adverse events |

| F = 68 | |||||||

| [Drop, 1977] [23] | USA | Open label | 5 Y–17 Y | 14 | N/A | Morbidity (hypoglycemia, hypokalemia) | |

| [Lindsay, 1989] [25] | USA | Open label | 2 Y–17 Y | 38 | N/A | Morbidity (cerebral edema) | |

| [Nallasamy, 2014] [26] | India | Open label | 0 Y–12 Y | 50 | M = 36 | M = 44 | Morbidity (cerebral edema, hypoglycemia, hypokalemia), mortality |

| F = 64 | F = 56 | ||||||

| [Onur, 1979] [27] | USA | Open label | 4 Y–15 Y | 10 | N/A | Morbidity (cerebral edema, hypoglycemia, hypokalemia), adverse events | |

| [Perkin, 1979] [28] | USA | Open label | N/A | 58 | N/A | Morbidity (hypoglycemia, hypokalemia) | |

| [Rameshkumar, 2021] [29] | India | Double blinding | 0 Y–12 Y | 60 | N/A | Morbidity (cerebral edema, hypoglycemia, hypokalemia), mortality | |

| [Razavi, 2018] [30] | Iran | Open label | 2 Y–17 Y | 50 | M = 52 | M = 36 | Mortality, Hospital stay, Adverse Events |

| F = 48 | F = 64 | ||||||

| [Saikia, 2022] [32] | India | Open label | 0 Y–12 Y | 30 | M = 46.7 F = 53.3 | M = 26.7 F = 73.3 | Morbidity (cerebral edema, hypoglycemia, hypokalemia), mortality |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Idrees, H.; Memon, F.; Alam, R.; Talal, M.; Ishaq, A.; Amjad, F.; Lang, E.; Soofi, S.B.; Ariff, S. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Insulin Dose and Route of Administration Regimens for Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Children and Adolescents. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7792. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217792

Idrees H, Memon F, Alam R, Talal M, Ishaq A, Amjad F, Lang E, Soofi SB, Ariff S. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Insulin Dose and Route of Administration Regimens for Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7792. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217792

Chicago/Turabian StyleIdrees, Hiba, Fozia Memon, Ridwa Alam, Muhammad Talal, Aqsa Ishaq, Fatima Amjad, Eddy Lang, Sajid B. Soofi, and Shabina Ariff. 2025. "Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Insulin Dose and Route of Administration Regimens for Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Children and Adolescents" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7792. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217792

APA StyleIdrees, H., Memon, F., Alam, R., Talal, M., Ishaq, A., Amjad, F., Lang, E., Soofi, S. B., & Ariff, S. (2025). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Insulin Dose and Route of Administration Regimens for Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7792. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217792