Assessing the Reliability of Compliance with the General Treatment Recommendations by Patients Treated for Temporomandibular Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. The Results

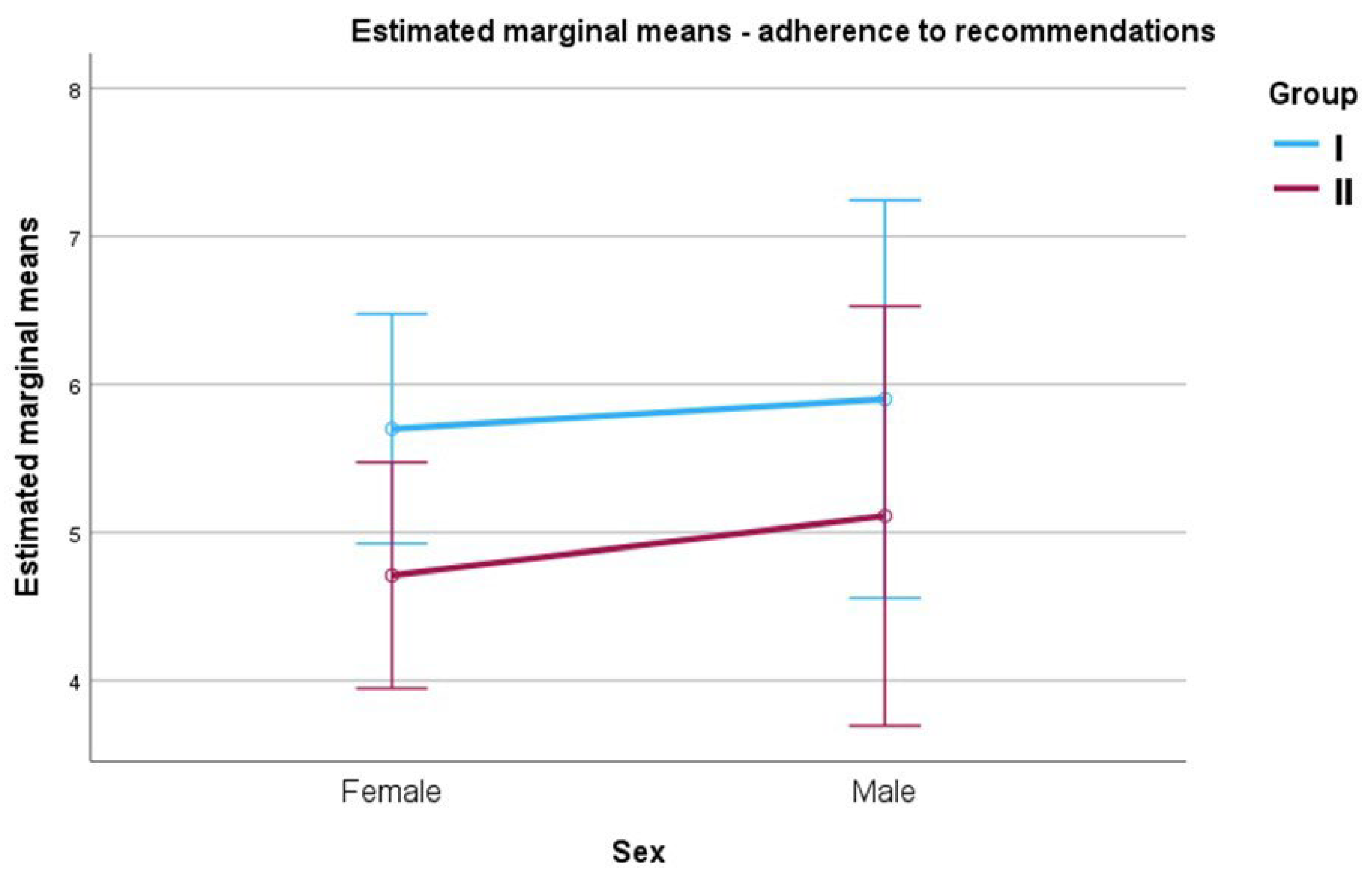

Adherence Rate vs. Presence of Pain Symptoms and Gender of Subjects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wright, E.; Klasser, G. Manual of Temporomandibular Disorders, 4th ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman, E.; Ohrbach, R.; Truelove, E.; Look, J.; Anderson, G.; Goulet, J.P.; Dworkin, S.F. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014, 28, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillingim, R.B.; Ohrbach, R.; Greenspan, J.D.; Knott, C.; Diatchenko, L.; Dubner, R.; Maixner, W. Psychological factors associated with development of TMD: The OPPERA prospective cohort study. J. Pain 2013, 14, T75–T90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fale, H.; Hnamte, L.; Deolia, S.; Pasad, S.; Kohale, S.; Sen, S. Association between parafunctional habit and sign and symptoms of temporomandibular dysfunction. J. Dent. Res. Rev. 2018, 5, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatli, U.; Benlidayi, M.E.; Ekren, O.; Salimov, F. Comparison of the effectiveness of three different treatment methods for temporomandibular joint disc displacement without reduction. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wänman, A.; Ernberg, M.; List, T. Guidelines in the management of orofacial pain/TMD. An evidence-based approach. Nor. Tann. Tid. 2016, 126, 104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Pesqueira, A.A.; Zuim, P.R.; Monteiro, D.R.; Do Prado Ribeiro, P.; Garcia, A.R. Relationship between psychological factors and symptoms of TMD in university undergraduate students. Acta Odontol. Latinoam. 2010, 23, 182–187. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, C.; Ghahreman, K.; Huppa, C.; Gallagher, J.E. Management of temporomandibular disorders: A rapid review of systematic reviews and guidelines. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 51, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, G.D.; Diatchenko, L.; Bhalang, K.; Sigurdsson, A.; Fillingim, R.B.; Belfer, I.; Maixner, W. Influence of psychological factors on risk of temporomandibular disorders. J. Dent. Res. 2007, 86, 1120–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paço, M.; Peleteiro, B.; Duarte, J.; Pinho, T. The effectiveness of physiotherapy in the management of temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review and meta- analysis. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2016, 30, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.L.; Yap, A.U. Outcomes of therapy TMD interventions on oral health related quality of life: A qualitative systematic review. Orofac. Pain 2018, 49, 487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrillo, M.; Giudice, A.; Marotta, N.; Fortunato, F.; Di Venere, D.; Ammendolia, A.; de Sire, A. Pain management and rehabilitation for central sensitization in temporomandibular disorders: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butts, R.; Dunning, J.; Pavkovich, R.; Mettille, J.; Mourad, F. Conservative management of temporomandibular dysfunction: A literature review with implications for clinical practice guidelines (Narrative review part 2). J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2017, 21, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Freitas, R.F.C.P.; Ferreira, M.Â.F.; Barbosa, G.A.S.; Calderon, P.S. Counselling and self-management therapies for temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2013, 40, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolakis, P.; Erdogmus, B.; Kopf, A.; Nicolakis, M.; Piehslinger, E.; Fialka- Moser, V. Effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome. J. Oral Rehabil. 2002, 29, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Von Piekartz, H. Clinical Reasoning for the Examination and Physical Therapy Treatment of Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD): A Narrative Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, R. Understanding Statistics for the Social Sciences with IBM SPSS; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gauer, R.L.; Semidey, M.J. Diagnosis and treatment of temporomandibular disorders. Am. Fam. Physician 2015, 91, 378–386. [Google Scholar]

- Pihut, M.; Pihut, M.; Ferendiuk, E.; Szewczyk, M.; Kasprzyk, K.; Wieckiewicz, M. The efficiency of botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of masseter muscle pain in patients with temporomandibular joint dysfunction and tension-type headache. J. Headache Pain 2016, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihut, M.; Szuta, M.; Ferendiuk, E.; Zeńczak-Więckiewicz, D. Evaluation of pain regression in patients with temporomandibular dysfunction treated by intra- articular platelet-rich plasma injections: A preliminary report. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 132369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, W.R.; Blasczyk, J.C.; de Oliveira, M.A.F.; Gonçalves, K.F.L.; Bonini- Rocha, A.C.; Dugailly, P.M.; de Oliveira, R.J. Efficacy of musculoskeletal manual approach in the treatment of temporomandibular joint disorder: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Man. Ther. 2016, 21, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doeuk, C.; Hersant, B.; Bosc, R.; Lange, F.; SidAhmed-Mezi, M.; Bouhassira, J.; Meningaud, J.P. Current indications for low level laser treatment in maxillofacial surgery: A review. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 53, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.T.S.; Leung, Y.Y. Temporomandibular disorders: Current concepts and controversies in diagnosis and management. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Barreto Aranha, R.L.; De Abreu, M.H.N.G.; Serra-Negra, J.M.; Martins, R.C. Current evidence about relationships among prosthodontic planning and temporomandibular disorders and/or bruxism. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2018, 18, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Martínez, A.; Paris-Alemany, A.; López-de-Uralde-Villanueva, I.; La Touche, R. Management of pain in patients with temporomandibular disorder (TMD): Challenges and solutions. J. Pain Res. 2018, 11, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lile, I.E.; Hajaj, T.; Veja, I.; Hosszu, T.; Vaida, L.L.; Todor, L.; Stana, O.; Popovici, R.-A.; Marian, D. Comparative Evaluation of Natural Mouthrinses and Chlorhexidine in Dental Plaque Management: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Recommendations | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Application of physiotherapy treatments in a series of 10 to 14 treatments at small intervals | 48 | 60.0% |

| Stress management/education of ways to cope with stress | 46 | 57.5% |

| Sleep hygiene | 46 | 57.5% |

| Maintaining dental arch discomfort throughout the day | 46 | 57.5% |

| Performing 15 repetitions of relaxation exercises daily throughout the day | 44 | 55.0% |

| Using an orthopaedic pillow while sleeping | 43 | 53.8% |

| Required duration of occlusal splint use | 38 | 47.5% |

| Hot compresses on the chewing muscles | 37 | 46.3% |

| Taking recommended supplements | 37 | 46.3% |

| Mental control of the jaw position/fighting against pathological habits of teeth clenching | 37 | 46.3% |

| M | Mdn | SD | Sk. | Kurt. | Min. | Max. | W | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence rate | 5.28 | 5.00 | 2.15 | 0.08 | −0.85 | 1 | 10 | 0.96 | 0.011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pihut, M.; Maga, W.; Gala, A. Assessing the Reliability of Compliance with the General Treatment Recommendations by Patients Treated for Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6674. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186674

Pihut M, Maga W, Gala A. Assessing the Reliability of Compliance with the General Treatment Recommendations by Patients Treated for Temporomandibular Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(18):6674. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186674

Chicago/Turabian StylePihut, Małgorzata, Wojciech Maga, and Andrzej Gala. 2025. "Assessing the Reliability of Compliance with the General Treatment Recommendations by Patients Treated for Temporomandibular Disorders" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 18: 6674. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186674

APA StylePihut, M., Maga, W., & Gala, A. (2025). Assessing the Reliability of Compliance with the General Treatment Recommendations by Patients Treated for Temporomandibular Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(18), 6674. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186674