Abstract

Background/Objectives: Patients undergoing open thoracic aortic surgery have the highest bleeding complication rates within cardiac–vascular surgery, but research on coagulation management mostly targets general cardiac surgery. This scoping review evaluates current evidence on intraoperative hemostatic agents and their effect on bleeding and blood transfusions in these patients. Methods: We searched MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase, and Cochrane Library on 2 July 2024. Eligible studies included randomized controlled (RCT) and observational trials with a comparison group and at least a sub-analysis regarding thoracic aortic surgery (excluding thoracoabdominal and isolated descending aorta surgery). Results: Our search yielded 4697 articles, with 33 included. These covered antifibrinolytics (3 RCTs, 10 observational studies), fibrinogen supplementation (3 RCTs, 4 observational studies), recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa, 8 observational studies), blood products (3 observational studies), and factor eight inhibitor bypassing activity (FEIBA, 1 RCT, 1 observational study). The impact of blood product transfusion on bleeding control is unclear due to a lack of placebo or no-transfusion comparisons, though it appears associated with more complications. Both FEIBA studies suggest reduced blood product use in aortic dissection surgery—one as rescue therapy, the other as standard treatment. Evidence on fibrinogen supplementation is mixed: a multicenter RCT showed increased transfusions, while smaller RCTs and observational studies showed reductions, possibly due to differences in pretreatment fibrinogen levels and patient selection. Observational studies on rFVIIa show conflicting results, likely due to selection bias. Two small RCTs—one on TXA, one on aprotinin—suggest reduced transfusions and blood loss. Comparative studies of different types of antifibrinolytics yielded conflicting results. Conclusions: Evidence on hemostatic agents in thoracic aortic surgery is limited. Small studies suggest potential for the routine use of antifibrinolytics, FEIBA, and fibrinogen supplementation—but only in bleeding patients with hypofibrinogenemia. High-quality RCTs focused on thoracic aortic procedures are needed to determine optimal coagulation management.

1. Introduction

Patients undergoing open thoracic aortic surgery often have major bleeding complications requiring appropriate coagulation management [1]. Thoracic aortic surgery requires the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), where the foreign materials can activate the coagulation cascade. Heparin as an anticoagulant is, thus, routinely used and antagonized with protamine after CPB to restore hemostasis [2,3,4]. Nevertheless, both coagulopathy and massive bleeding can occur after CPB [5,6]. These bleeding complications are often a result of acquired platelet dysfunction, increased fibrinolysis, and the depletion of coagulation factors [5,7].

Within cardiac surgery, aortic procedures are associated with the highest bleeding complication rate [8]. These complications can significantly worsen patient outcomes, including transfusion-related adverse events, ischemic complications due to a reduction in organ perfusion, and higher mortality [8,9]. Patients with aortic pathology often already present with dysregulated coagulation before surgery as a result of abnormal blood flow in aortic aneurysms or an intimal tear in aortic dissections [10,11]. These disturbances may activate the coagulation cascade, resulting in coagulopathy and, in extreme cases, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [10,12].

Systematic reviews on coagulation management in cardiac surgery have been published earlier and are included in guidelines [13,14]. However, they do not make a distinction specifically on thoracic aortic surgery and no other guidelines specifically focused on thoracic aortic surgery. This scoping review aims to evaluate current knowledge on intraoperative hemostatic agents in patients undergoing thoracic aortic surgery. We provide an overview of hemostatic agents used and their impact on bleeding and transfusion requirements and identify existing knowledge gaps and directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

The Department of Anesthesiology in the Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, performed a search strategy with the help of a medical information specialist (FJ). MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase, and Cochrane Library were searched using predefined search terms from inception until the 2nd of July 2024 (see Supplement S1 for the full search strategy). No filters were used in the search. For the identification of upcoming or ongoing trials, clinicaltrials.gov was searched with the terms “thoracic aortic surgery”, “thoracic aortic aneurysm”, and “acute aortic dissection”, without the use of other filters. This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [15].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Thoracic aortic surgery was defined as surgery which required the opening of the thorax, and surgery of the aortic root, ascendens, or arch, with the use of CPB. Surgeries solely on the descending aorta and endovascular surgeries were excluded. Further inclusion criteria were studies written in English, including adult patients, determining the effect of intraoperative administration of blood products, antifibrinolytics, fibrinogen supplementation or coagulation factors, and the effect of these products on bleeding and/or number of blood transfusions. Randomized controlled trials (RCT) and observational trials were included if they comprised of a control group. Studies that primarily focused on the cardiac surgery population but also included thoracic aortic surgery patients were only included if they provided a subgroup analysis. No restrictions were made for the year of publication or size of the study population. Animal studies, in vitro studies, case reports, case series, reviews, editorials, conference notes, and also reports from overlapping or duplicated populations were excluded. Furthermore, non-pharmacological studies for bleeding management (e.g., cell saver, auto-transfusion, and viscoelastic test-guided transfusion algorithms) or topical hemostatic agents were not included in this review.

2.3. Selection and Data Collection Process

Both title and abstract screening and full-text screening were performed by two independent reviewers (MH and CB) using Rayyan [16]. Disagreement on article inclusion were resolved by a third reviewer (HH).

The extraction of data was performed by one reviewer (MH). Data consisted of the first author, year of publication, years of inclusion, population, type of study, number of inclusions, methodology, intervention, outcome measurements, and findings of the included reports.

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies

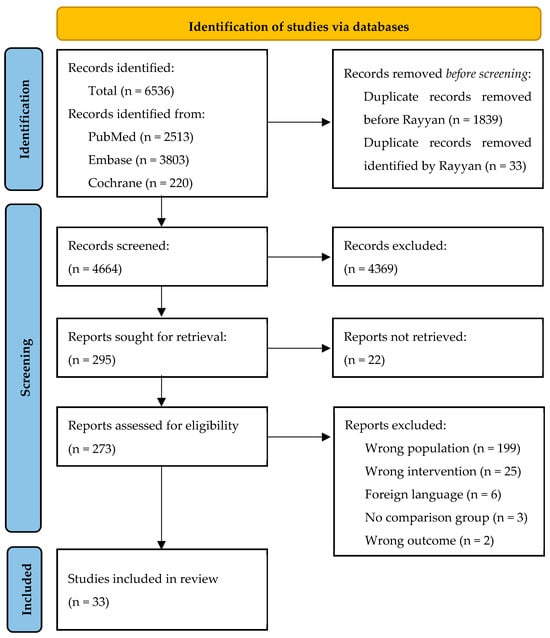

The initial search after deduplication yielded 4664 articles, of which 295 articles were assessed in full-text form, resulting in 33 included articles (Figure 1). Most exclusions in the full text screening were due to absence of subgroup analysis on thoracic aortic surgery.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of included studies. Wrong population included either no cardiac or thoracic aortic surgery or no subgroup analysis of thoracic aortic surgery. Wrong intervention included non-pharmacological interventions (e.g., autotransfusion, cell saver, or acute normal hemodilution) or the effect of transfusion protocols (e.g., ROTEM).

Of the included studies, three studies were on blood products as an intervention [17,18,19], two studies were on factor eight inhibitor bypassing activity (FEIBA) [20,21] (Table 1), seven studies were on fibrinogen supplementation [22,23,24,25,26,27,28] (Table 2), eight studies were on recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa) [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] (Table 3), and thirteen studies were on antifibrinolytics [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49] (Table 4). No studies were found on other prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs), factor XIII, or desmopressin in the context of thoracic aortic surgery.

Table 1.

Summary of the included studies on blood products (n = 4) and FEIBA (n = 2).

Table 2.

Summary of included studies on fibrinogen suppletion (n = 7).

Table 3.

Summary of included studies on rFVIIa (n = 8).

Table 4.

Summary of included studies on antifibrinolytics (n = 13).

3.2. Blood Products

Stensballe et al. (2018) conducted a single-center, single-blinded RCT comparing OctoplastGP (solvent/detergent-treated, virus-inactivated, pooled human plasma, n = 29) to FFP (n = 28) in dissection patients [17]. While patients and study assessors were blinded, clinicians were not, introducing potential bias. Dosing and transfusion protocols were not clearly reported. OctoplastGP reduced intraoperative blood loss (~600 mL), transfusion requirements, and markers of endothelial injury, with no reported safety concerns.

Wu et al. (2014) retrospectively compared dissection patients who received intraoperative platelet transfusion (n = 74) to those who did not (n = 85) [18]. In-hospital mortality was similar between the groups, but the platelet transfused group had a higher frequency of RBC transfusion in larger volumes, postoperative sternal wound infections, and neurological deficits.

Naeem et al. (2018) performed a non-matched retrospective study on aortic dissection patients [19]. Patients receiving >2 units of RBCs (n = 34) had more post-transfusion infections compared to those receiving 0–2 units RBC (n = 68). Similarly, patients given >1 unit of platelets (n = 28) had higher rates of acute kidney injury and atrial fibrillation than those receiving 0–1 unit (n = 74). Both high-transfusion groups had longer hospital stays, but mortality rates were unchanged.

In conclusion, the impact of blood product transfusion on bleeding outcomes remains unclear, as no studies compared transfusion to placebo or no transfusion while focusing on bleeding control. However, blood product transfusion appears to be associated with increased post-transfusion complications.

3.3. Factor Eight Inhibitor Bypassing Activity (FEIBA)

Two studies evaluated the use of FEIBA in aortic dissection surgery [20,21] (Table 1). Sera et al. (2021) conducted a pilot RCT comparing FEIBA (20 IU/kg) to a placebo in six patients per group [20]. The study found numerically lower intraoperative blood products and chest tube drainage, but it was not powered for significance.

Pupovac et al. (2022) performed a retrospective propensity-matched study with 53 patients, administering 500 IU of FEIBA as a salvage measure for persistent bleeding after RBCs, platelets, plasma, and cryoprecipitate [21]. The study showed reduced transfusion requirements in the first 48 h post-surgery, with no difference in thromboembolic complications.

In conclusion, both studies suggest that FEIBA may reduce blood product use in aortic dissection surgery. However, the timing of FEIBA administration was different in these two studies, where it was a rescue therapy in the retrospective study but standard in the pilot RCT.

3.4. Fibrinogen Supplementation

Seven studies on fibrinogen supplementation were included [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Several additional studies identified in the full-text review phase were excluded as they were re-analyses or post hoc analyses of the REPLACE trials. Only the original REPLACE trials were included. Both the initial single-center REPLACE trial and the subsequent larger multicenter trials were included, as they recruited different patient populations (Table 2).

3.4.1. Fibrinogen Supplementation Compared to Placebo

Three RCTs evaluated fibrinogen supplementation. The multicenter REPLACE trial (2016, 78 patients with fibrinogen vs. 74 with placebo) used ROTEM-guided dosing targeting a FIBTEM A5 of 22 mm, with a mean fibrinogen dose of 6.29 g [22]. Fibrinogen was given if the 5 min post-CPB bleeding mass (measured by sponges and suction canisters) ranged between 60 and 250 g. Unexpectedly, total 24 h blood product use was higher in the fibrinogen group (median five vs. three units), likely due to higher pretreatment bleeding mass, low overall bleeding rates, and variability in adherence to the transfusion algorithm. Notably, 31% of patients had a pretreatment fibrinogen level > 2 g/L. There were no differences in thromboembolic events.

The earlier single-center REPLACE study (2013) with 29 patients receiving fibrinogen concentrate and 32 receiving a placebo showed reduced blood product use with a median fibrinogen dose of 8 g [23].

A more recent single-center RCT by Vlot et al. (2022, 10 patients per group) used the same 5 min bleeding mass as REPLACE. However, fibrinogen dosage was based on weight without applying a target ROTEM value [24]. In their study, 90% (18 patients) had pretreatment fibrinogen levels < 2 g/L. No difference in blood product use was found, though the 5 min bleeding mass was non-significantly reduced by 52% in the fibrinogen group vs. 32% in the placebo group. The study was terminated early due to a slow inclusion rate.

3.4.2. Fibrinogen Supplementation Compared to No Treatment

Three observational studies compared fibrinogen supplementation to no supplementation.

Kikura et al. (2023) conducted a multicenter retrospective study (285 fibrinogen vs. 154 control patients) in both elective and emergency thoracic aortic surgery patients, administering 2–3 g fibrinogen after CPB cessation if fibrinogen < 1.0–1.2 g/L or FIBTEM A10 < 6 mm [25]. No differences were found in major bleeding, re-exploration, or mortality. RBC and FFP transfusions were reduced, while platelet transfusion was increased. A subgroup analysis of patients with fibrinogen levels < 1.5 g/L suggested that fibrinogen reduced major bleeding, despite the study’s transfusion protocol requiring all included patients to have low fibrinogen levels. Li et al. (2022) studied 105 aortic dissection patients receiving 2 g fibrinogen preoperatively and 54 controls, finding reduced intraoperative RBC transfusion, chest tube drainage, and shorter ventilation and hospital stays [26]. Guan et al. (2023) compared 54 aortic dissection patients receiving 25–50 mg/kg fibrinogen after protamine reversal to 30 controls, showing reduced blood transfusions and chest tube drainage [27].

3.4.3. Fibrinogen Supplementation Compared to FFP

Yamamoto et al. (2014) compared fibrinogen concentrate (n = 25, 3–5 g) to FFP (n = 24) in patients with fibrinogen < 1.5 g/L at the end of CPB, including both elective and dissection cases. Fibrinogen concentrate significantly reduced intraoperative blood loss and led to lower RBC, FFP, and platelet transfusion requirements [28].

In conclusion, the evidence on fibrinogen supplementation in thoracic aortic surgery remains inconclusive. The multicenter REPLACE RCT showed a negative effect (more blood transfusion), while the single-center REPLACE RCT and a smaller single-center RCT suggested positive effects (less blood transfusion). Three retrospective studies indicated benefits of fibrinogen supplementation with no increased thromboembolic complications, with one showing superiority over FFP. Differences in pretreatment fibrinogen levels and patient selection may explain the variability in results.

3.5. Recombinant Factor VIIa (rFVIIa)

Eight studies on rFVIIa were included [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] (Table 3). Yan et al. (2014) conducted a non-randomized RCT in aortic dissection patients, where treatment decisions were determined by the patients’ family, with 25 patients in the intervention group receiving rFVIIa (2.4 mg) plus platelet transfusion and 46 patients receiving conventional therapy (RBCs, FFP, platelets, and cryoprecipitate) after the cessation of CPB [29]. The intervention reduced intraoperative transfusion and postoperative platelet use, but no differences were observed in postoperative blood loss or adverse events.

Six observational studies in dissection patients and one observational study on thoracic aortic patients including dissections were included: Zindovic et al. (2017) performed a multicenter propensity-matched study on 120 dissection patients, but rFVIIa dosage and transfusion protocols were not clearly defined [30]. The rFVIIa group received more blood products, had more chest tube drainage, and had more re-explorations due to bleeding. Keyoumu et al. (2024) found that rFVIIa reduced chest tube drainage and RBC/FFP transfusions but was associated with more thromboembolic complications and higher mortality [31]. Andersen et al. (2012) reported reduced postoperative blood product use, with no difference in complications in the rFVIIa group [32]. Goksedef et al. (2012) found that rFVIIa reduced postoperative chest tube drainage, transfusion, and reoperations [33]. Ise et al. (2022) reported no difference in blood loss or transfusion between the rFVIIa and no rFVIIa group [34]. Tritapepe et al. (2007) showed that rFVIIa reduced postoperative blood loss but required more blood products [35]. Lastly, Hang et al. (2021) compared rFVIIa patient controls in both elective and dissection patients and found was no difference in postoperative transfusion, chest tube drainage, or complications, with a trend toward higher reoperation rates [36].

In conclusion, the studies on the efficacy of rFVIIa present conflicting results. Bias appears to be present, as the rFVIIa groups often show higher intraoperative blood product use, even after matching. The non-randomized prospective trial has limitations, such as unclear descriptions of the transfusion protocol in the usual care group.

3.6. Antifibrinolytics

3.6.1. Tranexamic Acid (TXA) Versus Placebo or No TXA

In an RCT, Casati et al. (2002) compared TXA (1 g bolus before incision, 400 mg/hour infusion) to a placebo in elective thoracic aortic surgery [37] (Table 4). In 29 patients per group, TXA reduced perioperative red blood cell (RBC) transfusion and postoperative blood loss. The incidence of excessive bleeding (>600 mL/24 h) was lower in the TXA group, with no difference in thromboembolic complications. Similarly, Ahn et al. (2015) compared a continuous TXA infusion (16 mg/kg/h) to no TXA in 26 dissection patients, demonstrating reduced transfusion requirements and chest tube drainage, again without increased thromboembolic complications [38].

3.6.2. TXA Versus Epsilon-Aminocaproic Acid (EACA) or Aprotinin

In an RCT comparing TXA to EACA, Makhija et al. (2013) included 61 patients undergoing thoracic aortic surgery (TXA: 31 patients, 10 mg/kg bolus, 1 mg/kg/h infusion and EACA: 30 patients, 50 mg/kg bolus, 25 mg/kg/h infusion) [39]. No significant differences in blood loss or transfusion requirements were found, though TXA showed a non-significant trend towards more seizures.

Four retrospective studies compared TXA to aprotinin. Reidy et al. (2024) matched 49 pairs of dissection patients receiving TXA (1 g bolus, 500 mg/h infusion) or aprotinin (2 million unit bolus, 500,000 units/h infusion) [40]. No differences were found in transfusions, drainage, mortality, or reoperation. Nicolau-Raducu et al. (2010) showed a trend toward lower blood product use in the aprotinin group but more renal dysfunction [41]. Sniecinski et al. (2010) found that TXA was associated with increased fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and cryoprecipitate transfusions, with a non-significant higher incidence of seizures [42]. Chivasso et al. (2018) analyzed 107 matched patients, comparing TXA to aprotinin, with no differences in major bleeding or reoperation, though FFP use was higher in the aprotinin group [43]. Sedrakyan et al. (2006) found that aprotinin (84 matched pairs) reduced platelet transfusions and chest tube drainage, but the timeframe of the outcomes was unclear [44].

3.6.3. Aprotinin Versus Placebo or No Aprotinin

Numerous studies on aprotinin use in cardiac surgery appeared following its market withdrawal after the BART trial [50] due to an increased risk of death in the trial, though debate persists within the scientific community regarding the appropriateness of this decision. In this review, we only report the studies on aprotinin in patients undergoing thoracic aortic surgery. In a placebo-controlled trial, Ehrlich et al. (1998) randomized 25 patients to receive 140 mg aprotinin and 25 patients to receive a placebo (saline). While no difference in renal function (primary outcome) was found, aprotinin reduced blood product use and chest tube drainage [45]. Westaby et al. (1994) compared 53 aprotinin patients (100 mg bolus, 25 mg/h infusion) to 29 controls and found no reduction in chest tube drainage; Interestingly, they reported increased blood loss in aprotinin-treated patients after 1989, coinciding with the introduction of hypothermic circulatory arrest, though blood loss assessment methods were unclear [46]. In contrast, Parolari et al. (1997) found reduced blood product use and blood loss in patients receiving 700 mg aprotinin (18 vs. 21 controls) but noted a trend toward more neurological deficits and complications [47]. Similarly, Seigne et al. (2000) showed reduced RBC, FFP, and platelet use with aprotinin (5 mg bolus, 5 mg/h infusion, 9 patients vs. 10 controls) without an effect on chest tube drainage [48].

3.6.4. Aprotinin Versus EACA

A single retrospective study by Eaton et al. (1998) compared aprotinin (n = 29, 100 mg bolus, 25 mg/h infusion) to EACA (n = 19, 5–40 g bolus, 25 mg/h infusion) in thoracic aortic surgery [49]. Five patients received both agents. No differences were found in RBC transfusion or chest tube drainage at six and twelve hours. Intraoperatively, the EACA group received more platelet transfusions and had a higher incidence of acute renal failure.

In conclusion, two small RCTs (each with <30 patients per group) comparing antifibrinolytics to placebo or no treatment, one with TXA and one with aprotinin, demonstrated reduced transfusion requirements and chest tube drainage without an increase in adverse events. The available retrospective studies provided inconsistent results, as follows: (1) three studies comparing aprotinin to no treatment showed mixed findings, with two suggesting a lack of benefit or potential harm, while one reported a positive effect (of note, the aprotinin studies were all published in the years 1994–2000), (2) one study comparing TXA to no treatment reported a positive effect for TXA, and (3) comparative studies between different types of antifibrinolytics gave no consistent signal favoring one over the other. The current evidence base is limited by heterogeneous study designs, varying antifibrinolytic dosages, and inconsistent outcome reporting, making a meta-analysis not feasible.

3.7. Upcoming or Ongoing Trials

Clinicaltrials.gov was searched on the 12th of March 2025 to identify upcoming or ongoing trials with the search term ‘thoracic aortic surgery’, resulting in 161 hits. No trials were found on intraoperative systemic hemostatic interventions. The search term ‘thoracic aortic aneurysm’ produced 388 hits. No relevant trials were found. The search term ‘acute aortic dissection’ yielded 396 results, of which one was a relevant non-randomized prospective trial on fibrinogen concentration (NCT02542306); however, this had not been updated since 2015 and no linked article could be found.

4. Discussion

There is limited evidence on hemostatic agents in thoracic aortic surgery patients. Smaller studies suggest potential for routine use of antifibrinolytics, FEIBA, and possibly fibrinogen supplementation, but only in bleeding patients with hypofibrinogenemia. The evidence on rFVIIa is conflicting. No studies on other prothrombin complex concentrates, FXIII, or desmopressin were found. Further high-quality, ideally randomized controlled trials, specifically focused on thoracic aortic procedures, are necessary to identify optimal coagulation management in these vulnerable patients.

4.1. Unique Challenges in Thoracic Aortic Surgery

Thoracic aortic surgery presents distinct hemostatic challenges compared to general cardiac surgery. Excessive bleeding occurs at a significantly higher rate (~15%) compared to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) (~5%) [8]. This is due to the complexity of the procedure, which often involves deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, prolonged aortic clamping, and extended CPB—all of which impact coagulation [51]. Furthermore, pre-existing coagulation abnormalities in aortic aneurysms and aortic dissections, as shown by elevated D-dimer levels [52,53] and coagulation factor consumption [10,11,54,55], may increase bleeding risk. Given these higher event rates, general cardiac surgery studies with lower event rates may underestimate the effect of interventions in this population. A further consideration is the difference between elective and acute aortic procedures. Elective surgeries, such as planned aortic aneurysm repairs, allow for preoperative optimization of coagulation status and blood conservation strategies. In contrast, acute aortic surgeries, particularly those for dissections, are performed under emergency conditions with high transfusion requirements, coagulopathy, and greater reliance on hemostatic interventions. This distinction is not always addressed in existing studies but may influence both clinical decision making and research outcomes.

4.2. Comparison with Guidelines

The 2024 European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and European Association of Cardiothoracic Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care (EACTAIC) guidelines strongly recommend antifibrinolytics, particularly TXA, to reduce bleeding, transfusions, and reoperations [13,14]. The guideline does not specifically make a distinction between cardiac surgery and thoracic aortic surgery. Of note, evidence for EACA is limited, and aprotinin, which may be effective, carries safety concerns. Our review aligns with these conclusions, finding no significant differences between TXA, EACA, and aprotinin. Additionally, a recent meta-analysis not included in the guideline further supports the benefits of TXA [56].

For fibrinogen supplementation, the guideline advises its use only in patients with confirmed hypofibrinogenemia, which aligns with our findings. While the REPLACE trials showed no overall beneficial effect, observational studies indicated benefits in patients with low fibrinogen levels. The guideline also favors PCC over FFP for coagulopathic bleeding, a recommendation supported by recent findings [57]. However, the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists (SCA) guideline does not provide a strong recommendation for routine use of PCC [14]. We found no studies for PCC in thoracic aortic surgery, apart from FEIBA, which showed promising results but requires further study.

Regarding rFVIIa, the guidelines advise against prophylactic use but allows for its use in refractory bleeding. Based on our review no definitive conclusion on rFVIIa use in thoracic aortic surgery could be drawn, as studies showed conflicting results regarding mortality and thromboembolic events.

For desmopressin and FXIII, no thoracic aortic surgery-specific studies were found. The EACTS-EACTA guidelines advise against routine use of FXIII and limits desmopressin to select cases. Regarding blood product use, both guidelines recommend restrictive RBC transfusion thresholds of ≤7.5 g/L.

While our findings largely align with current guidelines regarding antifibrinolytics and fibrinogen supplementation, specific data for thoracic aortic surgery remain sparse, and many recommendations in the guidelines are extrapolated from general cardiac surgery. Larger, targeted trials are needed to refine guidelines for this high-risk population.

4.3. Knowledge Gaps and Future Research

The EACTS/EACTAIC guidelines identify knowledge gaps in intraoperative procoagulant products, including TXA timing and dose, the role of aprotinin, and the impact of decreased FXIII activity. We argue that larger RCTs are needed specifically for thoracic aortic surgery, as these patients are at higher risk for bleeding and complications.

One key research priority is to stratify patients before study inclusion, ensuring that interventions are tested in those with certain documented coagulation profiles. For example, while the REPLACE trials on fibrinogen showed no benefit overall, a trial focusing solely on patients with hypofibrinogenemia (<1.5 g/L) could yield more meaningful results. Similarly, further studies on FEIBA, particularly in a randomized setting, are warranted.

Another challenge is the heterogeneity in study designs, including differences in dosing regimens, transfusion protocols, and outcome measures. Standardizing outcome reporting, particularly regarding bleeding assessment, is essential. Many studies lack clarity in defining blood loss, as factors, like cell saver blood, hemodilution, and gauze-absorbed bleeding, complicate accurate measurement. A promising measure could be the Universal Definition of Perioperative Bleeding (UDPB) score [58], which includes transfusions, reoperations, and chest tube drainage and is, among others, one of the recommendations in a recent consensus statement from 2025 [59]. This score has been validated for cardiac surgery and correlates with mortality. However, its application to thoracic aortic surgery remains untested and could be a valuable research direction.

5. Conclusions

Patients undergoing thoracic aortic surgery face distinct challenges in coagulation management that necessitate dedicated studies rather than extrapolation from general cardiac surgery. The current evidence base is limited, but small studies suggest potential benefits for routine antifibrinolytic use, FEIBA, and fibrinogen supplementation in bleeding patients with hypofibrinogenemia. Evidence for rFVIIa remains conflicting, and no studies on other PCCs, FXIII, or desmopressin were identified. Larger randomized trials with standardized outcome measures are required to refine hemostatic strategies for this high-risk population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14114001/s1, S1: Search Strategy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H.; methodology, M.M.T.v.H., C.B., and F.S.J.; data curation, M.M.T.v.H. and C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.T.v.H.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, M.M.T.v.H.; supervision, H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The search strategy can be found in the Supplementary File.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EACA | Epsilon-aminocaproic acid |

| FEIBA | Factor eight inhibitor bypassing activity |

| FFP | Fresh frozen plasma |

| PCC | Prothrombin complex concentrate |

| rFVIIa | Recombinant factor VIIa |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| TXA | Tranexamic acid |

References

- Zhang, C.H.; Ge, Y.P.; Zhong, Y.L.; Hu, H.O.; Qiao, Z.Y.; Li, C.N.; Zhu, J.M. Massive Bleeding After Surgical Repair in Acute Type A Aortic Dissection Patients: Risk Factors, Outcomes, and the Predicting Model. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 892696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranucci, M.; Baryshnikova, E. Inflammation and coagulation following minimally invasive extracorporeal circulation technologies. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11 (Suppl. S10), S1480–S1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sniecinski, R.M.; Chandler, W.L. Activation of the hemostatic system during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth. Analg. 2011, 113, 1319–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boer, C.; Meesters, M.I.; Veerhoek, D.; Vonk, A.B.A. Anticoagulant and side-effects of protamine in cardiac surgery: A narrative review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2018, 120, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez Rivera, J.J.; Iribarren, J.L.; Raya, J.M.; Nassar, I.; Lorente, L.; Perez, R.; Brouard, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Garrido, P.; Barrios, Y.; et al. Factors associated with excessive bleeding in cardiopulmonary bypass patients: A nested case-control study. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2007, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolliger, D.; Tanaka, K.A. Coagulation Management Strategies in Cardiac Surgery. Curr. Anesthesiol. Rep. 2017, 7, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuri, S.F.; Wolfe, J.A.; Josa, M.; Axford, T.C.; Szymanski, I.; Assousa, S.; Ragno, G.; Patel, M.; Silverman, A.; Park, M.; et al. Hematologic changes during and after cardiopulmonary bypass and their relationship to the bleeding time and nonsurgical blood loss. J. Thorac Cardiovasc. Surg. 1992, 104, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Attar, N.; Johnston, S.; Jamous, N.; Mistry, S.; Ghosh, E.; Gangoli, G.; Danker, W.; Etter, K.; Ammann, E. Impact of bleeding complications on length of stay and critical care utilization in cardiac surgery patients in England. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zindovic, I.; Sjogren, J.; Bjursten, H.; Bjorklund, E.; Herou, E.; Ingemansson, R.; Nozohoor, S. Predictors and impact of massive bleeding in acute type A aortic dissection. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2017, 24, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Paparella, D.; Rotunno, C.; Guida, P.; Malvindi, P.G.; Scrascia, G.; De Palo, M.; de Cillis, E.; Bortone, A.S.; de Luca Tupputi Schinosa, L. Hemostasis alterations in patients with acute aortic dissection. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011, 91, 1364–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanigawa, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Yamashita, T.; Nakagawachi, A.; Sakaguchi, Y. Preoperative disseminated intravascular coagulation complicated by thoracic aortic aneurysm treated using recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin: A case report. Medicine 2021, 100, e25044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, S.; Asakura, H. Therapeutic Strategies for Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation Associated with Aortic Aneurysm. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casselman, F.P.A.; Lance, M.D.; Ahmed, A.; Ascari, A.; Blanco-Morillo, J.; Bolliger, D.; Eid, M.; Erdoes, G.; Haumann, R.G.; Jeppsson, A.; et al. 2024 EACTS/EACTAIC Guidelines on patient blood management in adult cardiac surgery in collaboration with EBCP. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2024, 67, ezae352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, J.; Mazer, C.D.; Subramani, S.; Schroeder, A.; Abdalla, M.; Ferreira, R.; Philip, E.R.; Nichlesh, P.; Ian, W.; Philip, E.G.; et al. Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Clinical Practice Improvement Advisory for Management of Perioperative Bleeding and Hemostasis in Cardiac Surgery Patients. Anesth. Analg. 2019, 129, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensballe, J.; Ulrich, A.G.; Nilsson, J.C.; Henriksen, H.H.; Olsen, P.S.; Ostrowski, S.R.; Johansson, P.I. Resuscitation of Endotheliopathy and Bleeding in Thoracic Aortic Dissections: The VIPER-OCTA Randomized Clinical Pilot Trial. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 127, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Cheng, Y.; Rong, R. Intraoperative platelet transfusion is associated with increased postoperative sternal wound infections among type A aortic dissection patients after total arch replacement. Transfus. Med. 2014, 24, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, S.S.; Sodha, N.R.; Sellke, F.W.; Ehsan, A. Impact of Packed Red Blood Cell and Platelet Transfusions in Patients Undergoing Dissection Repair. J. Surg. Res. 2018, 232, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sera, V.A.; Stevens, A.E.; Song, H.K.; Rodriguez, V.M.; Tibayan, F.A.; Treggiari, M.M. Factor VIII inhibitor bypass activity (FEIBA) for the reduction of transfusion in cardiac surgery: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021, 7, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupovac, S.S.; Levine, R.; Giammarino, A.T.; Scheinerman, S.J.; Hartman, A.R.; Brinster, D.R.; Hemli, J.M. Factor eight inhibiting bypass activity for refractory bleeding in acute type A aortic dissection repair: A propensity-matched analysis. Transfusion 2022, 62, 2235–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahe-Meyer, N.; Levy, J.H.; Mazer, C.D.; Schramko, A.; Klein, A.A.; Brat, R.; Okita, Y.; Ueda, Y.; Schmidt, D.S.; Ranganath, R.; et al. Randomized evaluation of fibrinogen vs placebo in complex cardiovascular surgery (REPLACE): A double-blind phase III study of haemostatic therapy. Br. J. Anaesth. 2016, 117, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahe-Meyer, N.; Solomon, C.; Hanke, A.; Schmidt, D.S.; Knoerzer, D.; Hochleitner, G.; Benny, S.; Christian, H.; Maximilian, P. Effects of fibrinogen concentrate as first-line therapy during major aortic replacement surgery: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2013, 118, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlot, E.A.; Hackeng, C.M.; Aper, S.J.A.; Sonker, U.; Heijmen, R.H.; van Dongen, E.P.A.; Noordzij, P.G. Does Intraoperative Fibrinogen Affect Blood Loss or Transfusion Practice After Aortic Arch Surgery: A Prematurely Ended Randomized Trial. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2022, 28, 10760296221144042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikura, M.; Tobetto, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Uraoka, M.; Go, R. Effect of fibrinogen replacement therapy on bleeding outcomes and 1-year mortality in patients undergoing thoracic aortic surgery: A retrospective cohort study. J. Anesth. 2023, 37, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Q.; Tang, M.; Shen, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, L. Preoperative clinical application of human fibrinogen in patients with acute Stanford type A aortic dissection: A single-center retrospective study. J. Card. Surg. 2022, 37, 3159–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Li, L.; Lu, X.; Gong, M.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Lan, F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H. Safety and efficacy of fibrinogen concentrate in aortic arch surgery involving moderate hypothermic circulatory arrest. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2023, 55, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Usui, A.; Takamatsu, J. Fibrinogen concentrate administration attributes to significant reductions of blood loss and transfusion requirements in thoracic aneurysm repair. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2014, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Xuan, C.; Ma, G.; Zhang, L.; Dong, N.; Wang, Z.; Xu, R. Combination use of platelets and recombinant activated factor VII for increased hemostasis during acute type a dissection operations. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2014, 9, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zindovic, I.; Sjögren, J.; Ahlsson, A.; Bjursten, H.; Fuglsang, S.; Geirsson, A.; Ingemansson, R.; Hansson, E.C.; Mennander, A.; Olsson, C.; et al. Recombinant factor VIIa use in acute type A aortic dissection repair: A multicenter propensity-score-matched report from the Nordic Consortium for Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 154, 1852–1859.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyoumu, Y.; Mohemaiti, P.; Zhang, M.; Huo, Q.; Ma, X. Effect of the intraoperative infusion of recombinant activated coagulation factor VII on short-term prognosis and thoracic complications after acute aortic coarctation. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2024, 23, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, N.D.; Bhattacharya, S.D.; Williams, J.B.; Fosbol, E.L.; Lockhart, E.L.; Patel, M.B.; Gaca, J.G.; Welsby, I.J.; Hughes, G.C. Intraoperative use of low-dose recombinant activated factor VII during thoracic aortic operations. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 93, 1921–1928; discussion 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goksedef, D.; Panagopoulos, G.; Nassiri, N.; Levine, R.L.; Hountis, P.G.; Plestis, K.A. Intraoperative use of recombinant activated factor VII during complex aortic surgery. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2012, 143, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ise, H.; Ushioda, R.; Kanda, H.; Kimura, F.; Saijo, Y.; Akhyari, P.; Lichtenberg, A.; Kamiya, H. Recombinant Activated Factor VII in Aortic Surgery for Patients Under Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2022, 18, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tritapepe, L.; De Santis, V.; Vitale, D.; Nencini, C.; Pellegrini, F.; Landoni, G.; Federico, T.; Fabio, M.; Paolo, P. Recombinant activated factor VII for refractory bleeding after acute aortic dissection surgery: A propensity score analysis. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 1685–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, D.; Koss, K.; Rokkas, C.K.; Pagel, P.S. Recombinant activated factor VII for hemostasis in patients undergoing complex ascending aortic surgery: A single-center, single-surgeon retrospective analysis. J. Card. Surg. 2021, 36, 4558–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casati, V.; Sandrelli, L.; Speziali, G.; Calori, G.; Grasso, M.A.; Spagnolo, S. Hemostatic effects of tranexamic acid in elective thoracic aortic surgery: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2002, 123, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, K.T.; Yamanaka, K.; Iwakura, A.; Hirose, K.; Nakatsuka, D.; Kusuhara, T.; Ikarashi, J. Usefulness of intraoperative continuous infusion of tranexamic acid during emergency surgery for type A acute aortic dissection. Ann. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015, 21, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhija, N.; Sarupria, A.; Kumar Choudhary, S.; Das, S.; Lakshmy, R.; Kiran, U. Comparison of epsilon aminocaproic acid and tranexamic Acid in thoracic aortic surgery: Clinical efficacy and safety. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2013, 27, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, B.; Aston, D.; Sitaranjan, D.; Fazmin, I.T.; Muir, M.; Ali, J.; De Silva, R.; Falter, F. Lack of efficacy of aprotinin over tranexamic acid in type A aortic dissection repair. Transfusion 2024, 64, 846–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau-Raducu, R.; Subramaniam, K.; Marquez, J.; Wells, C.; Hilmi, I.; Sullivan, E. Safety and efficacy of tranexamic acid compared with aprotinin in thoracic aortic surgery with deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2010, 24, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sniecinski, R.M.; Chen, E.P.; Makadia, S.S.; Kikura, M.; Bolliger, D.; Tanaka, K.A. Changing from aprotinin to tranexamic acid results in increased use of blood products and recombinant factor VIIa for aortic surgery requiring hypothermic arrest. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2010, 24, 959–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivasso, P.; Bruno, V.D.; Marsico, R.; Annaiah, A.S.; Curtis, A.; Zebele, C.; Angelini, G.D.; Bryan, A.J.; Rajakaruna, C. Effectiveness and Safety of Aprotinin Use in Thoracic Aortic Surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2018, 32, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedrakyan, A.; Wu, A.; Sedrakyan, G.; Diener-West, M.; Tranquilli, M.; Elefteriades, J. Aprotinin use in thoracic aortic surgery: Safety and outcomes. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2006, 132, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, M.; Grabenwöger, M.; Cartes-Zumelzu, F.; Luckner, D.; Kovarik, J.; Laufer, G.; Kocher, A.; Konetschny, R.; Wolner, E.; Havel, M. Operations on the thoracic aorta and hypothermic circulatory arrest: Is aprotinin safe? J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1998, 115, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westaby, S.; Forni, A.; Dunning, J.; Giannopoulos, N.; O’Regan, D.; Drossos, G.; Pillai, R. Aprotinin and bleeding in profoundly hypothermic perfusion. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 1994, 8, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parolari, A.; Antona, C.; Alamanni, F.; Spirito, R.; Naliato, M.; Gerometta, P.; Arena, V.; Biglioli, P. Aprotinin and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest: There are no benefits even when appropriate amounts of heparin are given. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 1997, 11, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seigne, P.W.; Shorten, G.D.; Johnson, R.G.; Comunale, M.E. The effects of aprotinin on blood product transfusion associated with thoracic aortic surgery requiring deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2000, 14, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, M.P.; Deeb, G.M. Aprotinin versus epsilon-aminocaproic acid for aortic surgery using deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 1998, 12, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, D.A.; Hébert, P.C.; Mazer, C.D.; Fremes, S.; MacAdams, C.; Murkin, J.M.; Teoh, K.; Duke, P.C.; Arellano, R.; Blajchman, M.A.; et al. A Comparison of Aprotinin and Lysine Analogues in High-Risk Cardiac Surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2319–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.T.; Dos Santos, T.R.; Brunori, E.H.; Moorhead, S.A.; Lopes Jde, L.; Barros, A.L. Excessive bleeding predictors after cardiac surgery in adults: Integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 3046–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundermann, A.C.; Saum, K.; Conrad, K.A.; Russell, H.M.; Edwards, T.L.; Mani, K.; Björck, M.; Wanhainen, A.; Owens, A.P. Prognostic value of D-dimer and markers of coagulation for stratification of abdominal aortic aneurysm growth. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 3088–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Bai, T.; Yang, B.; Sun, L. The diagnostic value of D-dimer in acute aortic dissection: A meta-analysis. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 16, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.L.; Wang, X.L.; Liu, Y.Y.; Lan, F.; Gong, M.; Li, H.Y.; Liu, O.; Jiang, W.J.; Liu, Y.M.; Zhu, J.M.; et al. Changes in the Hemostatic System of Patients with Acute Aortic Dissection Undergoing Aortic Arch Surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2016, 101, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Han, L.; Li, J.; Gong, M.; Zhang, H.; Guan, X. Consumption coagulopathy in acute aortic dissection: Principles of management. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2017, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Li, X.; He, L.; Ji, H.; Yao, Y.; The Evidence in Cardiovascular Anesthesia (EICA) Group. Hemostatic effects of tranexamic acid in cardiac surgical patients with antiplatelet therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Perioper. Med. 2024, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkouti, K.; Callum, J.L.; Bartoszko, J.; Tanaka, K.A.; Knaub, S.; Brar, S.; Ghadimi, K.; Rochon, A.; Mullane, D.; Couture, E.J.; et al. Prothrombin Complex Concentrate vs. Frozen Plasma for Coagulopathic Bleeding in Cardiac Surgery: The FARES-II Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, 333, 1781–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyke, C.; Aronson, S.; Dietrich, W.; Hofmann, A.; Karkouti, K.; Levi, M.; Murphy, G.J.; Sellke, F.W.; Shore-Lesserson, L.; von Heymann, C.; et al. Universal definition of perioperative bleeding in adult cardiac surgery. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 147, 1458–1463.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salenger, R.; Arora, R.C.; Bracey, A.; D’Oria, M.; Engelman, D.T.; Evans, C.; Grant, M.C.; Gunaydin, S.; Morton, V.; Ozawa, S.; et al. Cardiac Surgical Bleeding, Transfusion, and Quality Metrics: Joint Consensus Statement by the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Cardiac Society and Society for the Advancement of Patient Blood Management. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2025, 119, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).