Biopsychosocial Response to the COVID-19 Lockdown in People with Major Depressive Disorder and Multiple Sclerosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- During lockdown: we chose the entire period of the national lockdown in each country.

- For the pre-lockdown phase, we chose the period immediately before the first restrictive measure with the same duration as the total national lockdown.

- We chose the period immediately following the national lockdown for the post-lockdown phase with the same duration.

- Denmark: lockdown began 13 March 2020, and post-lockdown started 16 April 2020

- Italy: lockdown began 9 March 2020, and post-lockdown started 19 May 2020

- Spain: lockdown began 14 March 2020, and post-lockdown started 5 May 2020

- The Netherlands: 15 March 2020 post-lockdown and started 12 May 2020

- UK: lockdown began 23 March 2020, and post-lockdown started 12 May 2020

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Ethical Statement

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

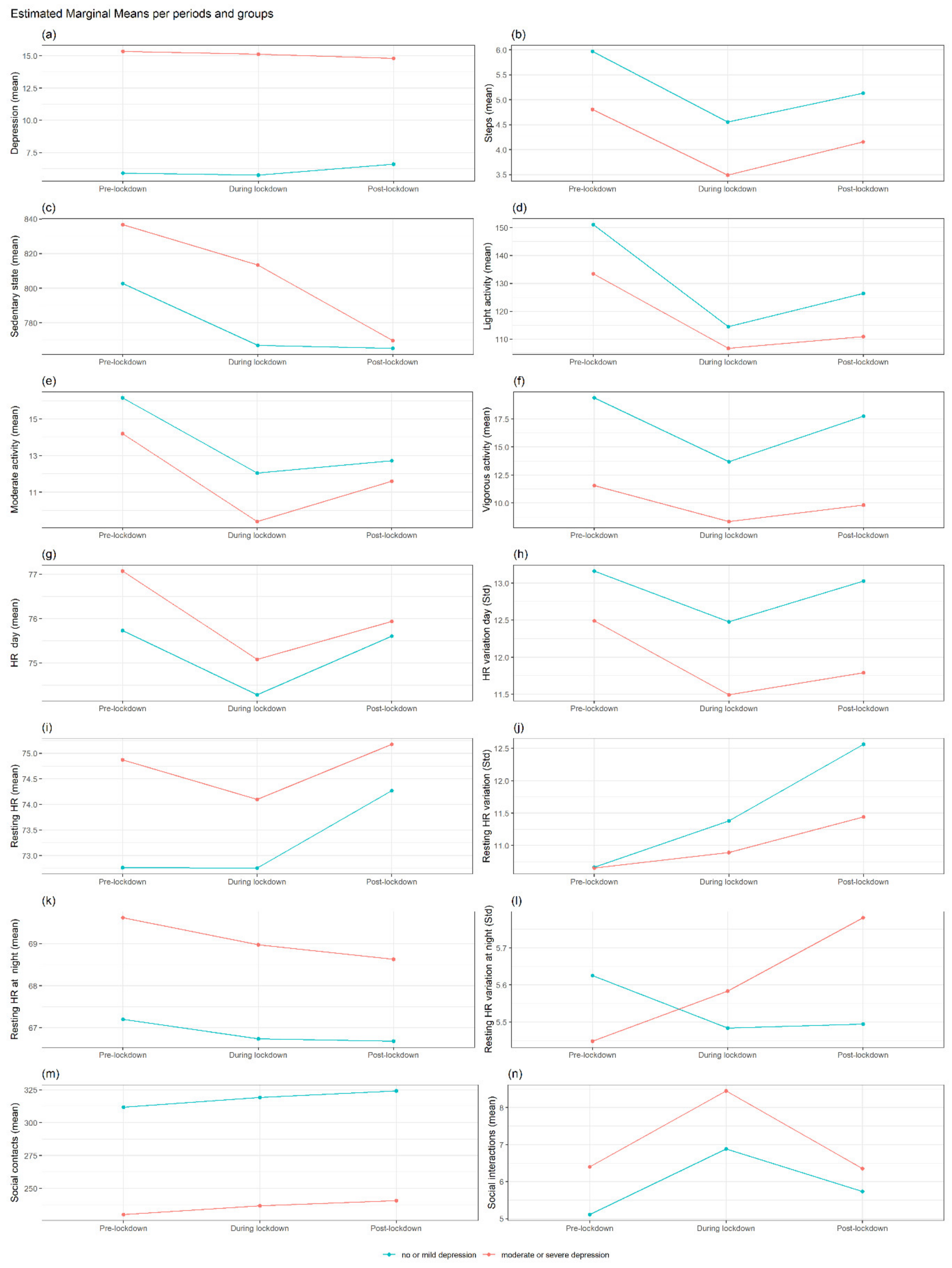

3.1. Summary of Findings in MDD

Differences in Each Outcome between No or Mild Depression vs. Moderate or Severe Depression at Each Period and Interaction with Gender

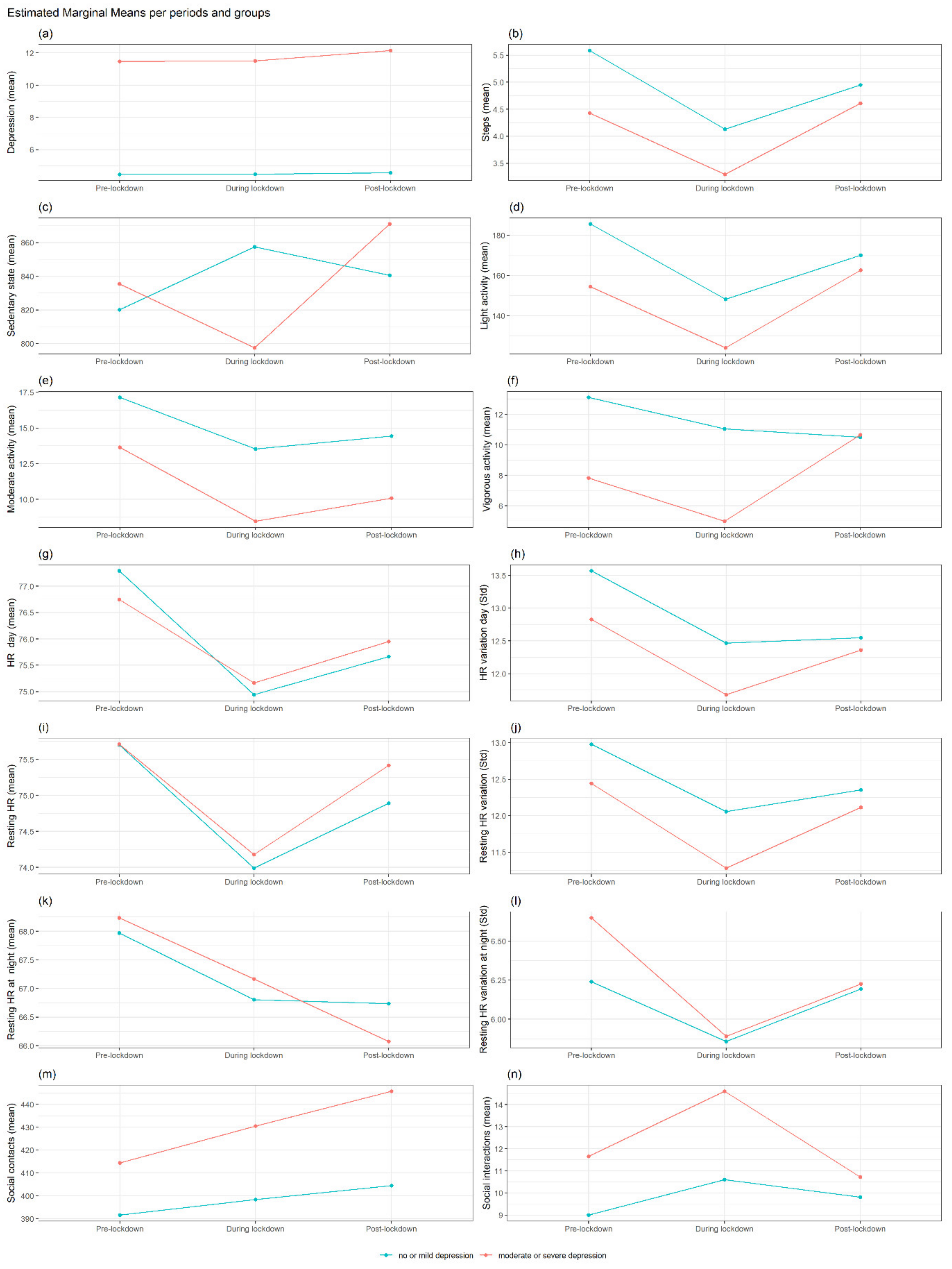

3.2. Summary of Findings for MS

Differences in Each Outcome between No or Mild Depression vs. Moderate or Severe Depression at Each Period and Interaction with Gender

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings on Participants with MDD

4.2. Findings on Participants with MS

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | COronaVIrus Disease 19 |

| HR | Heart rate |

| MDD | Major depressive disorder |

| MS | Multiple Sclerosis |

| mHR | mean HR |

| PPG | Photoplethysmography |

| PHQ-8 8-item | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| RADAR-CNS | Remote assessment of disease and relapse—central nervous system |

| RADAR-MDD | Remote assessment of disease and relapse—major depressive disorder |

| RMT | Remote measurement technology |

| SARS-CoV-2 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| stdHR | Standard deviation Heart Rate |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization. Listings of WHO’s Response to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Repubblica Italiana. Gazzetta Ufficiale. Serie Generale n.62 Del 09-03-2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2020/03/09/62/sg/pdf (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Stephensen, K.E.; Stærmose Hansen, T. 11 March 2020. Danmark Lukker Ned: Her Er Regeringens Nye Tiltag. TV2. Available online: https://nyheder.tv2.dk/samfund/2020-03-11-%0Adanmark-lukker-ned-her-er-regeringens-nye-tiltag (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Jefatura del Estado. Real Decreto 463/2020, de 14 de Marzo, Por El Que Se Declara El Estado de Alarma Para La Gestión de La Situación de Crisis Sanitaria Ocasionada Por El COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2020-3692 (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Prime Minister. Prime Minister’s Statement on Coronavirus (COVID-19): 23 March 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-address-to-the-nation-on-coronavirus-23-march-2020 (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Kamerbrief Met Nieuwe Aanvullende Maatregelen om de COVID-19-Uitbraak te Bestrijden. Available online: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2020/03/15/covid-19-nieuwe-aanvullende-maatregelen (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and How to Reduce It: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, S.; Biswas, P.; Ghosh, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Dubey, M.J.; Chatterjee, S.; Lahiri, D.; Lavie, C.J. Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Cohen Silver, R.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary Research Priorities for the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Call for Action for Mental Health Science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzman, M.R.; Curkovic, M.; Wasserman, D. Principles of Mental Health Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santomauro, D.F.; Mantilla Herrera, A.M.; Shadid, J.; Zheng, P.; Ashbaugh, C.; Pigott, D.M.; Abbafati, C.; Adolph, C.; Amlag, J.O.; Aravkin, A.Y.; et al. Global Prevalence and Burden of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in 204 Countries and Territories in 2020 Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodeur, A.; Clark, A.E.; Fleche, S.; Powdthavee, N. COVID-19, Lockdowns and Well-Being: Evidence from Google Trends. J. Public Econ. 2021, 193, 104346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, E.; Leichtling, G.; Larsen, J.E.; Gray, M.; Pope, J.; Leahy, J.M.; Gelberg, L.; Seaman, A.; Korthuis, P.T. The Impacts of COVID-19 on Mental Health, Substance Use, and Overdose Concerns of People Who Use Drugs in Rural Communities. J. Addict. Med. 2020, 15, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Folarin, A.A.; Ranjan, Y.; Rashid, Z.; Conde, P.; Stewart, C.; Cummins, N.; Matcham, F.; Dalla Costa, G.; Simblett, S.; et al. Using Smartphones and Wearable Devices to Monitor Behavioral Changes During COVID-19. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Who Is Lonely in Lockdown? Cross-Cohort Analyses of Predictors of Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Public Health 2020, 186, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Abella, J.; Gabarrell-Pascuet, A.; Faris, L.H.; Cristóbal-Narváez, P.; Félez-Nobrega, M.; Mortier, P.; Vilagut, G.; Olaya, B.; Alonso, J.; Haro, J.M. The Association of Detachment with Affective Disorder Symptoms during the COVID-19 Lockdown: The Role of Living Situation and Social Support. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 292, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.-J.; Rabheru, K.; Peisah, C.; Reichman, W.; Ikeda, M. Loneliness and Social Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, M.; Hope, H.; Ford, T.; Hatch, S.; Hotopf, M.; John, A.; Kontopantelis, E.; Webb, R.; Wessely, S.; McManus, S.; et al. Mental Health before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Probability Sample Survey of the UK Population. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leightley, D. Investigating the Impact of Coronavirus Lockdown on People with a History of Recurrent Major Depressive Disorder: A Multi-Centre Study Using Remote Measurement Technology. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegenga, B.T.; Nazareth, I.; Grobbee, D.E.; Torres-González, F.; Švab, I.; Maaroos, H.I.; Xavier, M.; Saldivia, S.; Bottomley, C.; King, M.; et al. Recent Life Events Pose Greatest Risk for Onset of Major Depressive Disorder during Mid-Life. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennant, C. Life Events, Stress and Depression: A Review of Recent Findings. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2002, 36, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsonis, C.I.; Potagas, C.; Zervas, I.; Sfagos, K. The Effects of Stressful Life Events on the Course of Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. Int. J. Neurosci. 2009, 119, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, D.C.; Hart, S.L.; Julian, L.; Cox, D.; Pelletier, D. Association between Stressful Life Events and Exacerbation in Multiple Sclerosis: A Meta-Analysis. Br. Med. J. 2004, 328, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeschoten, R.E.; Braamse, A.M.J.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Cuijpers, P.; van Oppen, P.; Dekker, J.; Uitdehaag, B.M.J. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 372, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, A.; Magalhaes, S.; Richard, J.F.; Audet, B.; Moore, C. The Link between Multiple Sclerosis and Depression. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegenga, B.T.; King, M.; Grobbee, D.E.; Torres-González, F.; Švab, I.; Maaroos, H.I.; Xavier, M.; Saldivia, S.; Bottomley, C.; Nazareth, I.; et al. Differential Impact of Risk Factors for Women and Men on the Risk of Major Depressive Disorder. Ann. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, J.N.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Rui, P.; Ruetsch, C.; Rothman, B.; Kulkarni, A.; Forma, F. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Healthcare Resource Utilization in Individuals with Major Depressive Disorder. Health Serv. Res. Manag. Epidemiol. 2022, 9, 233339282211118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Norman, G.A. Decentralized Clinical Trials: The Future of Medical Product Development? JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2021, 6, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, Y.; Rashid, Z.; Stewart, C.; Conde, P.; Begale, M.; Verbeeck, D.; Boettcher, S.; Dobson, R.; Folarin, A.; Hyve, T.; et al. RADAR-Base: Open Source Mobile Health Platform for Collecting, Monitoring, and Analyzing Data Using Sensors, Wearables, and Mobile Devices. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaneda, D.; Esparza, A.; Ghamari, M.; Soltanpur, C.; Nazeran, H. A Review on Wearable Photoplethysmography Sensors and Their Potential Future Applications in Health Care. Int. J. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 4, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, E.E.; Golaszewski, N.M.; Bartholomew, J.B. Estimating Accuracy at Exercise Intensities: A Comparative Study of Self-Monitoring Heart Rate and Physical Activity Wearable Devices. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.W.; Allen, N.B. Accuracy of Consumer Wearable Heart Rate Measurement During an Ecologically Valid 24-Hour Period: Intraindividual Validation Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e10828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J.F.; Åhs, F.; Fredrikson, M.; Sollers Iii, J.J.; Wager, T.D. A Meta-Analysis of Heart Rate Variability and Neuroimaging Studies: Implications for Heart Rate Variability as a Marker of Stress and Health. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 36, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.G.; Cheon, E.J.; Bai, D.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Koo, B.H. Stress and Heart Rate Variability: A Meta-Analysis and Review of the Literature. Psychiatry Investig. 2018, 15, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontaxis, S.; Gil, E.; Marozas, V.; Lazaro, J.; Garcia, E.; Posadas-de Miguel, M.; Siddi, S.; Bernal, M.L.; Aguilo, J.; Haro, J.M.; et al. Photoplethysmographic Waveform Analysis for Autonomic Reactivity Assessment in Depression. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 68, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.; Karmakar, C.; Gray, R.; Jindal, R.; Lim, T.; Bryant, C. Heart Rate Variability Alterations in Late Life Depression: A Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 235, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, A.H.; Quintana, D.S.; Gray, M.A.; Felmingham, K.L.; Brown, K.; Gatt, J.M. Impact of Depression and Antidepressant Treatment on Heart Rate Variability: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findling, O.; Hauer, L.; Pezawas, T.; Rommer, P.S.; Struhal, W.; Sellner, J. Cardiac Autonomic Dysfunction in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of Current Knowledge and Impact of Immunotherapies. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynders, T.; Gidron, Y.; De Ville, J.; Bjerke, M.; Weets, I.; Van Remoortel, A.; Devolder, L.; D’haeseleer, M.; De Keyser, J.; Nagels, G.; et al. Relation between Heart Rate Variability and Disease Course in Multiple Sclerosis. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauquet-Alekhine, P.; Rouillac, L.; Berton, J.; Granry, J.-C. Heart Rate vs Stress Indicator for Short Term Mental Stress. Br. J. Med. Med. Res. 2016, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matcham, F.; Barattieri Di San Pietro, C.; Bulgari, V.; De Girolamo, G.; Dobson, R.; Eriksson, H.; Folarin, A.A.; Haro, J.M.; Kerz, M.; Lamers, F.; et al. Remote Assessment of Disease and Relapse in Major Depressive Disorder (RADAR-MDD): A Multi-Centre Prospective Cohort Study Protocol. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Costa, G.; Leocani, L.; Montalban, X.; Guerrero, A.I.; Sørensen, P.S.; Magyari, M.; Dobson, R.J.B.; Cummins, N.; Narayan, V.A.; Hotopf, M.; et al. Real-Time Assessment of COVID-19 Prevalence among Multiple Sclerosis Patients: A Multicenter European Study. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 41, 1647–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Territorial Impact of COVID-19: Managing the Crisis across Levels of Government. (n.d.). Available online: www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-territorial-impact-of-COVID-19-managing-the-crisis-across-levels-of-government-d3e314e1/ (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Aknin, L.B.; Andretti, B.; Goldszmidt, R.; Helliwell, J.F.; Petherick, A.; De Neve, J.-E.; Dunn, E.W.; Fancourt, D.; Goldberg, E.; Jones, S.P.; et al. Policy Stringency and Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Analysis of Data from 15 Countries. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e417–e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. Available online: //covidtracker.bsg.ox.ac.uk/stringency-scatter (accessed on 13 March 2021).

- Polhemus, A.M.; Novák, J.; Ferrao, J.; Simblett, S.; Radaelli, M.; Locatelli, P.; Matcham, F.; Kerz, M.; Weyer, J.; Burke, P.; et al. Human-Centered Design Strategies for Device Selection in MHealth Programs: Development of a Novel Framework and Case Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e16043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simblett, S.; Greer, B.; Matcham, F.; Curtis, H.; Polhemus, A.; Ferrão, J.; Gamble, P.; Wykes, T. Barriers to and Facilitators of Engagement With Remote Measurement Technology for Managing Health: Systematic Review and Content Analysis of Findings. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e10480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simblett, S.; Matcham, F.; Siddi, S.; Bulgari, V.; Barattieri di San Pietro, C.; Hortas López, J.; Ferrão, J.; Polhemus, A.; Haro, J.M.; de Girolamo, G.; et al. Barriers to and Facilitators of Engagement With MHealth Technology for Remote Measurement and Management of Depression: Qualitative Analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e11325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simblett, S.K.; Evans, J.; Greer, B.; Curtis, H.; Matcham, F.; Radaelli, M.; Mulero, P.; Arévalo, M.J.; Polhemus, A.; Ferrao, J.; et al. Engaging across Dimensions of Diversity: A Cross-National Perspective on MHealth Tools for Managing Relapsing Remitting and Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2019, 32, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Strine, T.W.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Berry, J.T.; Mokdad, A.H. The PHQ-8 as a Measure of Current Depression in the General Population. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 114, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, S.B.; Burton, J.M.; Fiest, K.M.; Wiebe, S.; Bulloch, A.G.; Koch, M.; Dobson, K.S.; Metz, L.M.; Maxwell, C.J.; Jetté, N. Validity of Four Screening Scales for Major Depression in MS. Mult. Scler. J. 2015, 21, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, D.; Colwell, E.; Low, J.; Orychock, K.; Tobin, M.A.; Simango, B.; Buote, R.; Van Heerden, D.; Luan, H.; Cullen, K.; et al. Reliability and Validity of Commercially Available Wearable Devices for Measuring Steps, Energy Expenditure, and Heart Rate: Systematic Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e18694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Han, J.; Puyal, E.L.; Kontaxis, S.; Sun, S.; Locatelli, P.; Dineley, J.; Pokorny, F.B.; Costa, G.D.; Leocani, L.; et al. Fitbeat: COVID-19 Estimation Based on Wristband Heart Rate Using a Contrastive Convolutional Auto-Encoder. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 123, 108403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, G.; Macdermid, J.C.; Sinden, K.E.; Richardson, J.; Tang, A. Inter-Instrument Reliability and Agreement of Fitbit Charge Measurements of Heart Rate and Activity at Rest, during the Modified Canadian Aerobic Fitness Test, and in Recovery. Physiother. Can. 2019, 71, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difrancesco, S.; Lamers, F.; Riese, H.; Merikangas, K.R.; Beekman, A.T.F.; van Hemert, A.M.; Schoevers, R.A.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Sleep, Circadian Rhythm, and Physical Activity Patterns in Depressive and Anxiety Disorders: A 2-Week Ambulatory Assessment Study. Depress. Anxiety 2019, 36, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuch, F.; Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Rosenbaum, S.; Ward, P.; Reichert, T.; Bagatini, N.C.; Bgeginski, R.; Stubbs, B. Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in People with Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 210, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, B.; Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Schuch, F.B.; Hallgren, M.; Smith, L.; Gardner, B.; Kahl, K.G.; Veronese, N.; Solmi, M.; et al. Relationship between Sedentary Behavior and Depression: A Mediation Analysis of Influential Factors across the Lifespan among 42,469 People in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 229, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, S.; Smith, L.; Markovic, L.; Schuch, F.B.; Sadarangani, K.P.; Lopez Sanchez, G.F.; Lopez-Bueno, R.; Gil-Salmerón, A.; Rieder, A.; Tully, M.A.; et al. Associations between Physical Activity, Sitting Time, and Time Spent Outdoors with Mental Health during the First COVID-19 Lock Down in Austria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuch, F.B.; Bulzing, R.A.; Meyer, J.; López-Sánchez, G.F.; Grabovac, I.; Willeit, P.; Vancampfort, D.; Caperchione, C.M.; Sadarangani, K.P.; Werneck, A.O.; et al. Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Changes in Self-Isolating Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Survey Exploring Correlates. Sport Sci. Health 2021, 18, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, J.; Douglas, B.; Saikat, D.; Deepayan, S.; R Core Team. Nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models; R Package Version 3.1-152; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, V.L. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means; R Package Version 1.7.0.; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Matcham, F.; Leightley, D.; Siddi, S.; Lamers, F.; White, K.M.; Annas, P.; de Girolamo, G.; Difrancesco, S.; Haro, J.M.; Horsfall, M.; et al. Remote Assessment of Disease and Relapse in Major Depressive Disorder (RADAR-MDD): Recruitment, Retention, and Data Availability in a Longitudinal Remote Measurement Study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderman, N.; Ironson, G.; Siegel, S.D. Stress and Health: Psychological, Behavioral, and Biological Determinants. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlis, R.H.; Ognyanova, K.; Quintana, A.; Green, J.; Santillana, M.; Lin, J.; Druckman, J.; Lazer, D.; Simonson, M.D.; Baum, M.A.; et al. Gender-Specificity of Resilience in Major Depressive Disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2021, 38, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.-Y.; Kok, A.A.L.; Eikelenboom, M.; Horsfall, M.; Jörg, F.; Luteijn, R.A.; Rhebergen, D.; van Oppen, P.; Giltay, E.J.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. The Mental Health Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on People with and without Depressive, Anxiety, or Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders: A Longitudinal Study of Three Dutch Case-Control Cohorts. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; Sutin, A.R.; Daly, M.; Jones, A. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Cohort Studies Comparing Mental Health before versus during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 296, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, L.; Koebach, A.; Díaz, O.; Carleial, S.; Hoeffler, A.; Stojetz, W.; Freudenreich, H.; Justino, P.; Brück, T. Life With Corona: Increased Gender Differences in Aggression and Depression Symptoms Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic Burden in Germany. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 689396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré, L.; Fawaz, Y.; González, L.; Graves, J. How the COVID-19 Lockdown Affected Gender Inequality in Paid and Unpaid Work in Spain; IZA-Institute of Labor Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, L.K.C.; Minello, A. Mothers, Childcare Duties, and Remote Working under COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy: Cultivating Communities of Care. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2020, 10, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooi-Reci, I.; Risman, B.J. The Gendered Impacts of COVID-19: Lessons and Reflections. Gend. Soc. 2021, 35, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, A.; Phimister, A.; Krutikova, S.; Kraftman, L.; Farquharson, C.; Costa Dias, M.; Cattan, S.; Andrew, A. How Are Mothers and Fathers Balancing Work and Family under Lockdown? IFS: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Reisch, T.; Heiler, G.; Hurt, J.; Klimek, P.; Hanbury, A.; Thurner, S. Behavioral Gender Differences Are Reinforced during the COVID-19 Crisis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuaid, R.J.; Cox, S.M.L.; Ogunlana, A.; Jaworska, N. The Burden of Loneliness: Implications of the Social Determinants of Health during COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 296, 113648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-W.; Guo, Y.-T.; Di Tanna, G.L.; Neal, B.; Chen, Y.-D.; Schutte, A.E. Vital Signs During the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Retrospective Analysis of 19,960 Participants in Wuhan and Four Nearby Capital Cities in China. Glob. Heart 2021, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, C.; Wilhelm, M.; Salzmann, S.; Rief, W.; Euteneuer, F. A Meta-Analysis of Heart Rate Variability in Major Depression. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 1948–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, J.; Kemp, A.H.; Beauchaine, T.P.; Thayer, J.F.; Kaess, M. Depression and Resting State Heart Rate Variability in Children and Adolescents—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 46, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkiss, S.; Huckell, V.F. Cardiovascular Physiology: Similarities and Differences between Healthy Women and Men. J. SOGC 1997, 19, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quer, G.; Gouda, P.; Galarnyk, M.; Topol, E.J.; Steinhubl, S.R. Inter- and Intraindividual Variability in Daily Resting Heart Rate and Its Associations with Age, Sex, Sleep, BMI, and Time of Year: Retrospective, Longitudinal Cohort Study of 92,457 Adults. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Füzéki, E.; Groneberg, D.A.; Banzer, W. Physical Activity during COVID-19 Induced Lockdown: Recommendations. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2020, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belvederi Murri, M.; Ekkekakis, P.; Magagnoli, M.; Zampogna, D.; Cattedra, S.; Capobianco, L.; Serafini, G.; Calcagno, P.; Zanetidou, S.; Amore, M. Physical Exercise in Major Depression: Reducing the Mortality Gap While Improving Clinical Outcomes. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuch, F.B.; Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Rosenbaum, S.; Ward, P.B.; Silva, E.S.; Hallgren, M.; Ponce De Leon, A.; Dunn, A.L.; Deslandes, A.C.; et al. Physical Activity and Incident Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, H.; Bush, S.; Gappmaier, E. Associations Between Fatigue and Disability, Functional Mobility, Depression, and Quality of Life in People with Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. MS Care 2016, 18, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanov, A.; Malobabic, M.; Milosevic, V.; Stojanov, J.; Vojinovic, S.; Stanojevic, G.; Stevic, M. Psychological Status of Patients with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis during Coronavirus Disease-2019 Outbreak. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 45, 102407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radin, J.M.; Wineinger, N.E.; Topol, E.J.; Steinhubl, S.R. Harnessing Wearable Device Data to Improve State-Level Real-Time Surveillance of Influenza-like Illness in the USA: A Population-Based Study. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, e85–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, C.; Jackson, S.; Oldham, M.; Brown, J.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Factors Associated with Drinking Behaviour during COVID-19 Social Distancing and Lockdown among Adults in the UK. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 219, 108461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damla, O.; Altug, C.; Pinar, K.K.; Alper, K.; Dilek, I.G.; Kadriye, A. Heart Rate Variability Analysis in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2018, 24, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimoradi, Z.; Broström, A.; Tsang, H.W.H.; Griffiths, M.D.; Haghayegh, S.; Ohayon, M.M.; Lin, C.-Y.; Pakpour, A.H. Sleep Problems during COVID-19 Pandemic and Its’ Association to Psychological Distress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 36, 100916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, M.H.; Nilsagard, Y. Balance, Gait, and Falls in Multiple Sclerosis. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 159, pp. 237–250. [Google Scholar]

- Weygandt, M.; Meyer-Arndt, L.; Behrens, J.R.; Wakonig, K.; Bellmann-Strobl, J.; Ritter, K.; Scheel, M.; Brandt, A.U.; Labadie, C.; Hetzer, S.; et al. Stress-Induced Brain Activity, Brain Atrophy, and Clinical Disability in Multiple Sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 13444–13449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balto, J.M.; Pilutti, L.A.; Motl, R.W. Loneliness in Multiple Sclerosis. Rehabil. Nurs. 2018, 44, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhao, H.; Ju, K.; Shin, K.; Lee, M.; Shelley, K.; Chon, K.H. Can Photoplethysmography Variability Serve as an Alternative Approach to Obtain Heart Rate Variability Information? J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2008, 22, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, E.; Orini, M.; Bailón, R.; Vergara, J.M.; Mainardi, L.; Laguna, P. Photoplethysmography Pulse Rate Variability as a Surrogate Measurement of Heart Rate Variability during Non-Stationary Conditions. Physiol. Meas. 2010, 31, 1271–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical and Social Activity Variables Derived from the Apps | ||

|---|---|---|

| Depression Level | PHQ-8 score | PHQ-8 score last observation before pre-lockdown phase. |

| Score range = 0–24 | ||

| Cut-off score ≥ 10 moderate to severe depression | ||

| Social activity | ||

| Contacts | Daily mean of contacts | Number of all contacts per day |

| Social interactions | Sum of interactions and short cuts with the social apps | Number of interactions with social apps (whatsapp, facebook, twitter and others) used to make calls, read and send messages in one day |

| Physiological features (derived from Fitbit device) | ||

| Physical activity | ||

| Heart rate parameters | ||

| Mean HR day | Mean HR during the day | Mean HR across whole day (24 h) |

| HR variation /day | Std of HR during the day | Standard deviation of HR across whole day (24 h) |

| Resting mean HR day | Mean HR during the resting period across whole day | Resting of mean HR across whole day (24 hours) |

| Resting HR variation / day | Std of HR during the resting period across whole day | Std of HR during sedentary periods, identified by activity level = sedentary periods and number of steps = 0 (24 h) |

| Resting mean HR at night | Mean HR at rest during the night | Mean HR during sedentary periods, identified by activity level = sedentary and number of steps = 0 only during night time (0:00–05:59) |

| Resting HR variation at night | Std of HR variation at night | Standard deviation of HR |

| Steps | Mean steps | Mean steps per minute all day (24 h) |

| Sedentary state | “Sedentary” Minutes | The number of minutes in a day for which the physical activity was classified as “sedentary”. |

| Light, Moderate and Vigorous activity | “Active” Minutes | The number of minutes in a day for which the physical activity was classified as “light”, “moderate” or “vigorous activity” |

| MDD (N = 255) | MS (N = 214) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean, SD) | 47.73 (15.42) | 44.77 (9.94) |

| Gender (Women, N %) | 190 (74.51) | 144 (67.29) |

| Marital status | ||

| Without partner (Single/ Separated Divorced/Widowed) | 129 (50.59%) | 73 (34.43%) |

| (Partner/Married | 126 (49.41%) | 139 (65.57%) |

| Education years mean (SD) | 15.01 (6.15) | 16.91 (5.91) |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

| PHQ-8 | 9 (10) | 5 (6) |

| Physical activity | ||

| Steps | 6076. (7243) | 6523 (6912) |

| Sedentary | 949.36 (385.89) | 925.29 (322.57) |

| Light activity | 138.07 (121.89 | 166.29 (150.07) |

| Moderate activity | 8.36 (17.14) | 8.43 (18.14) |

| Vigorous activity | 6.71 (20.86) | 3.86 (11.71) |

| HR parameters | ||

| mean HR day | 74.87 (11.22) | 76.72 (9.86) |

| std HR day | 12.46 (3.95) | 12.87 (4.11) |

| Resting mean HR day | 72.82 (11.03) | 75.44 (9.79) |

| Resting std HR day | 11.14 (4.18) | 12.42 (3.79) |

| Resting mean HR at night | 66.53 (11.66) | 67.04 (10.58) |

| Resting std HR at night | 4.93 (2.15) | 5.43 (3.03) |

| Social activity parameters | ||

| Social contacts | 136 (163) | 258 (344) |

| Social interactions | 5 (10) | 6 (13) |

| Pre- and During Lockdown (95% CI, p-Value) | Pre- and Post-Lockdown 95% CI, p-Value) | During and Post-Lockdown 95% CI, p-Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-8 | 0.24 (−0.32 to 0.81) | 0.03 (−0.58 to 0.64) | −0.22 (−0.78 to 0.35 |

| Steps | 1.32 (0.91 to 1.73) *** | 0.79 (0.33 to 1.26) ** | −0.52 (−0.99 to −0.061) * |

| Sedentary | 52.0 (0.59 to 103.4) * | 73.7 (16.59 to 130.8) ** | 21.7(−28.040 to 71.5) |

| Light activity | 38.06 (25.9 to 50.21) *** | 30.35 (17.1 to 43.55) *** | −7.71(−19.4 to 3.99) |

| Moderate activity | 4.24 (1.97 to 6.51) *** | 2.94 (0.32 to 5.56) * | −1.30 (−3.02 to 0.42) |

| Vigorous activity | 3.45 (1.29 to 5.61) *** | 1.31 (−0.93 to 3.55) | −2.14 (−4.28 to −0.004) * |

| Mean HR day | 1.38 (0.78 to 1.99) *** | 0.43 (−0.29 to 1.14) | −0.95 (−1.69 to −0.22) ** |

| std HR day | 0.75 (0.37 to 1.14) *** | 0.44 (0.039 to 0.84) * | −0.32 (−0.77 to 0.13) |

| Resting mean HR day | −0.037 (−0.64 to 0.57) | −1.25 (−1.98 to −0.51) *** | −1.21 (−1.94 to −0.48) *** |

| Resting std HR day | −0.72 (−1.24 to −0.19) ** | 1.45 (−2.00 to 0.93) *** | −0.75 (−1.23 to 0.27) *** |

| Resting mean HR at night | 0.31 (−0.40 to 1.03) | 0.53 (−0.23 to 1.29) | 0.21 (−0.39 to −0.82) |

| Resting std HR at night | 0.065 (−0.21 to 0.34) | −0.06 (−0.38 to 0.26) | −0.12 (−0.44 to 0.19) |

| Social contacts | −7.30 (−12.6 to −2.04) ** | −11.85 (−19.31 to −4.36) ** | −4.55 (−65.8 to −56.72) * |

| Social interactions | −2.42 (−3.64 to −1.20) *** | −1.05 (−2.11 to 0.01) * | 1.37 (0.138 to 2.60) * |

| Pre- and During Lockdown (95% CI, p-Value) | Pre- and Post-Lockdown 95% CI, p-Value) | During and Post-Lockdown 95% CI, p-Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-8 | −0.07 (−0.62 to 0.47) | −0.191 (−0.79 to 0.41) | −0.117 (−0.66 to 0.43) |

| Steps | 1.36 (0.82 to 1.89) *** | 0.44 (−0.04 to 0.93) | −0.91 (−1.35 to −0.48) *** |

| Sedentary | −7.33 (−74.3 to 59.7) | −4.21 (−76.0 to 67.6) | 3.12 (−63.4 to 69.6) |

| Light activity | 35.5 (17.0 to 53.9) *** | 12.7 (−9.0 to 34.49) | −22.7 (−41.8 to −3.67) * |

| Moderate activity | 3.72 (0.069 to 7.36) * | 2.71 (−0.90 to 6.33) | −1.01 (−4.30 to 2.30) |

| Vigorous activity | 2.17 (−1.11 to 5.46) | 1.14 (−2.22 to 4.49) | −1.04 (−5.01 to 2.93) |

| mHR day | 2.14 (1.26 to 3.02) ** | 1.38 (0.44 to 2.32) ** | −0.76 (−1.57 to 0.05) |

| std HR day | 1.10 (0.56 to 1.63) *** | 0.80 (0.32 to 1.28) ** | −0.30 (−0.85 to 0.25) |

| Resting mHR day | 1.67 (0.78 to 2,57) *** | 0.64 (−0.28 to 1.57) | −1.03 (−1.85 to −0.21) ** |

| Resting std HR day | 0.98 (0.48 to 1.49) *** | 0.46 (0.014 to 0.91) * | −0.53 (−1.07 to 0.020 |

| Resting mHR at night | 1.20 (0.02 to 2.39) * | 1.37 (0.16 to 2.58) ** | 0.16 (−1.04 to 1.37) |

| Resting std HR at night | 0.57 (0.02 to 1.15) * | 0.12 (−0.29 to 0.53) | −0.44 (−1.01 to 0.11) |

| Social contacts | −9.17 (−15.7 to −2.61) ** | −18.01 (−44.4 to 8.40) | −8.84 (−37.2 to 19.55) |

| Social interactions | −1.92 (−4.15 to 0.31) | −1.01 (−3.46 to 1.44) | 0.91 (−2.33 to 4.14) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siddi, S.; Giné-Vázquez, I.; Bailon, R.; Matcham, F.; Lamers, F.; Kontaxis, S.; Laporta, E.; Garcia, E.; Arranz, B.; Dalla Costa, G.; et al. Biopsychosocial Response to the COVID-19 Lockdown in People with Major Depressive Disorder and Multiple Sclerosis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7163. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237163

Siddi S, Giné-Vázquez I, Bailon R, Matcham F, Lamers F, Kontaxis S, Laporta E, Garcia E, Arranz B, Dalla Costa G, et al. Biopsychosocial Response to the COVID-19 Lockdown in People with Major Depressive Disorder and Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(23):7163. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237163

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiddi, Sara, Iago Giné-Vázquez, Raquel Bailon, Faith Matcham, Femke Lamers, Spyridon Kontaxis, Estela Laporta, Esther Garcia, Belen Arranz, Gloria Dalla Costa, and et al. 2022. "Biopsychosocial Response to the COVID-19 Lockdown in People with Major Depressive Disorder and Multiple Sclerosis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 23: 7163. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237163

APA StyleSiddi, S., Giné-Vázquez, I., Bailon, R., Matcham, F., Lamers, F., Kontaxis, S., Laporta, E., Garcia, E., Arranz, B., Dalla Costa, G., Guerrero, A. I., Zabalza, A., Buron, M. D., Comi, G., Leocani, L., Annas, P., Hotopf, M., Penninx, B. W. J. H., Magyari, M., ... on behalf of the RADAR-CNS Consortium. (2022). Biopsychosocial Response to the COVID-19 Lockdown in People with Major Depressive Disorder and Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(23), 7163. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237163