Abstract

Introduction: Quality of life (QoL) improvement is one of the main outcomes in the management of pelvic organ prolapse as a chronic illness in women. This systematic review aimed to investigate the impact of surgical or pessary treatment for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) on quality of life. Methods: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was applied. Electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, were searched for original articles that evaluated the QoL before and after surgical interventions or pessary in pelvic organ prolapse from 1 January 2012 until 30 June 2022 with a combination of proper keywords. Included studies were categorized based on interventions, and they were tabulated to summarize the results. Results: Overall, 587 citations were retrieved. Of these, 76 articles were found eligible for final review. Overall, three categories of intervention were identified: vaginal surgeries (47 studies), abdominal surgeries (18 studies), and pessary intervention (11 studies). Almost all interventions were associated with improved quality of life. The results of the meta-analysis showed a significant association between the employment of surgical approach techniques (including vaginal and abdominal surgeries) and the quality of life (Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI) (MD: −48.08, 95% CI: −62.34 to −33.77, p-value < 0.01), Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ) (MD: −33.41, 95% CI: −43.48 to −23.34, p < 0.01)) and sexual activity of patients with pelvic organ prolapse (Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire (PISQ) (MD: 4.84, 95% CI: 1.75 to 7.92, p < 0.01)). Furthermore, narrative synthesis for studies investigating the effect of the pessary approach showed a positive association between the use of this instrument and improvement in the quality of life and sexual activity. Conclusions: The results of our study revealed a significant improvement in the women’s quality of life following abdominal and vaginal reconstructive surgery. The use of pessary was also associated with increased patient quality of life.

1. Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) occurs due to weakness of the supportive tissues of the pelvic organs, which may lead to prolapse of the anterior and/or posterior vaginal wall, the uterus (cervix), or the apex of the vagina (vaginal vault or cuff scar after hysterectomy) [1]. The prevalence of POP is currently increasing due to extended life expectancies and childbearing in low-resource areas [2]. Pelvic prolapses are not always symptomatic and can lead to discomfort in the vagina and changes in bladder and bowel function that can greatly affect women’s quality of life [3], with general, social, psychological, and sexual impacts [4]. Therefore, improving the quality of life is one of the main outcomes in the management of pelvic organ prolapse in women [5].

Surgical interventions for POP include repairing with native tissue or mesh and minimally invasive surgeries such as laparoscopic or robotic techniques, which are increasing in popularity [6]. The selection of the intervention depends on several factors, such as the site and severity of the POP; additional symptoms that affect urinary, bowel, or sexual function; the wish to preserve the uterus; and the surgeon’s choice and ability. Surgical treatment options include vaginal or abdominal (laparotomy, laparoscopy, and, more recently, robotic approach) [7]. There are also conservative interventions, which are defined as non-surgical methods such as optimizing lifestyle (weight loss and avoiding heavy lifting or coughing) and physical therapies [8]. In the last decades, pessaries, which have existed since the beginning of recorded history, have also been used in women with POP [9]. These are removable devices that provide support after prolapse [9]. Various instruments have been designed to assess the quality of life (QoL). Some of them evaluate the general aspect, whereas others, such as the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory (POPDI-6) and Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire (POPIQ-7), are specific for POP [10,11]. Some questionnaires are dedicated to the quality of sex life [12].

QoL studies for POP are very diverse, with different methods, instruments, and follow-ups. Therefore, studies that summarize the results and provide final recommendations are scarce. Performing a systematic review is the best way to summarize the effects of POP treatment on QoL. A similar study was performed in 2012 by Doaee et al. that examined articles over the past ten years [13]. Due to the advances in urogynecological surgery and other interventional methods such as pessaries, updating this data seems necessary. The current study aims to review those studies that have focused on changing the QoL by means of surgery or pessary for POP management.

2. Methods

The current systematic review was designed to review QoL in women before and after surgery or pessary intervention for POP management in English biomedical journals. The study is reported based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [14].

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) study design: all original articles including randomized clinical trials, observational studies (cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort), and editorials/letters; (2) patient population and intervention: adult women with POP who received surgical treatments or pessary intervention for POP management; and (3) outcome: evaluated quality of life using available questionnaires. Review articles, opinions or guidelines, conference abstracts, non-peer-reviewed papers, case reports, unpublished reports, and articles in which the date and location of the study were not specified were excluded.

2.2. Information Sources

The initial search was undertaken in three main databases including articles published in MEDLINE (through PubMed), Scopus, and Web of Science from 1 January 2012 until 31 June 2022. Additionally, a manual search in the reference section of the relevant studies was done to obtain possible publications that were missed in our electronic search.

2.3. Search Strategy

To retrieve citations on the topic based on the medical subject heading (Mesh), a combination of the following keywords was used: ‘pelvic organ prolapses’, ‘quality of life’, and ‘treatment’. The study time frame was also applied to all databases. A full search strategy for each database is available in the Supplementary Materials.

2.4. Study Selection

Titles and abstracts were independently reviewed for eligibility by three authors (PJ, RH, and SP), and non-relevant or duplicate studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. In cases of disagreement, the problem was resolved by discussion and the main author (ZG.). After initial screening, the full texts of the articles were reviewed, and the unrelated articles were removed.

2.5. Quality Assessment

NS and AS independently assessed the quality of the included studies using the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) tools [15]. Based on the design of a study (whether a randomized controlled trial or a cohort), an individual checklist that contains 14 signaling questions for assessing the quality of each study was used. Briefly, studies scoring nine or more “Yes” answers were marked as “Good”, studies scoring between seven or eight were marked as “Fair”, and studies rating less than seven were marked as “Poor” quality.

2.6. Data Extraction

The data—including the first author, publication date and study design, intervention mode, using mesh or native tissue, sample size, stage of prolapse and prolapse type, main findings, and the instrument used to measure the QoL, as well as the follow-up duration and quality of papers—were extracted and tabulated.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

We used the mean difference (MD) of the total quality of life questionnaire values before and after the intervention. Using a random effect model, the quantitative values of each study were pooled separately. If the MD was not given in the specific study, an estimate was made using Excel calculators [16]. The Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory Questionnaire (PFDI) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7) were used as the main measures for pooling the results of the studies regarding the QoL of patients. Furthermore, the PISQ and FSFI questionnaires were used to pool the data regarding the sexual activity of patients after the intervention. We used Cochran’s Q statistic (Q-test) and the I2 to assess heterogeneity. I2 value >75% indicated a high amount of heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of the funnel plot, and Egger’s test with a significance level of 0.05 was used to evaluate the publication bias. All analyses were statistically significant with a p-value < 0.05. The analyses were performed using R-4.1.3 software and the Meta package (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria; available at https://www.R-project.org/, accessed on 6 January 2022).

2.8. Registration Statement

We have written the protocol of this study, but due to the high diversity of studies and quality of life assessment methods, we did not register it due to the high possibility of changes in the protocol

3. Results

3.1. Statistics

Overall, 587 citations were found to be eligible. After excluding 435 duplicates, 122 studies were screened by the title and abstract. By excluding 21 citations, 100 full text articles were reviewed, and 76 articles were finally eligible for final evaluations. The flowchart of the study is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the recruiting studies according to PRISMA.

3.2. Instrument Used

A wide variety of questionnaires were used to measure patient-reported outcomes, including QoL measures. Of these, some were the general measures, and several instruments were pelvic-specific QoL questionnaires. Some instruments are used for measuring sexual QoL in sexually active women. The most common general instruments were the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) and Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I), while the pelvic-specific measures were the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory Questionnaire-20 (PFDI- 20), Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire-12 (PISQ-12), Prolapse Quality of Life (P-QOL), and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-7 (PFIQ-7). The Sexual QoL was measured by the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). The questionnaires are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Questionnaires used in the recruited studies.

3.3. General Findings

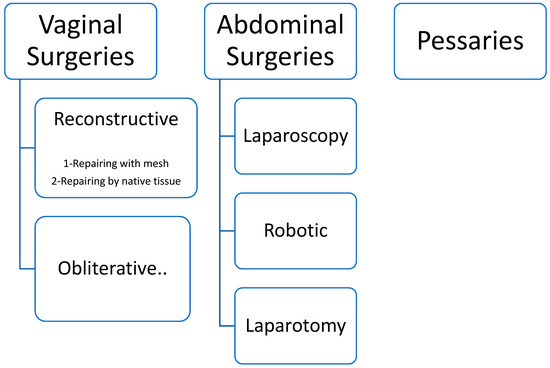

To facilitate reporting the results, papers were classified into three categories: vaginal surgeries (47 articles), abdominal surgeries (18 articles), and pessary interventions (11 articles). These are categorized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Categorization of the included studies.

3.3.1. Vaginal Surgeries

There were two main procedures for vaginal surgeries: reconstructive (in two subgroups, including repair with natural tissue [17,19,20,23,24,31,36,37,38,60,61,63,64,65,66] (Table 2) and repair with mesh [7,9,12,21,25,26,29,32,35,39,40,41,42,43,44,55,62,67,68,69,78,82,83,85]) (Table 3) and obliterative surgeries [18,27,60,71,72,73,86] (Table 4). In one study, obliterative surgery and sacrospinous fixation in older postmenopausal women were compared, and the QoL was better in the sacrospinous group [18]. These results are the opposite of another article with the same method and population that showed that obliterative surgery versus reconstructive acted better in improving the QoL [28,72,79].

Table 2.

The characteristics of the studies on the effectiveness of reconstructive vaginal surgeries by native tissue on the quality of life in women with pelvic organ prolapse.

Table 3.

The characteristics of the studies on the effectiveness of reconstructive vaginal surgeries with mesh on the quality of life in women with pelvic organ prolapse.

Table 4.

The characteristics of the studies on the effectiveness of obliterative vaginal surgeries on the quality of life in women with pelvic organ prolapse.

Overall, 60.5% (23/38) of the reconstructive studies used mesh for repairing. In a recent study, transvaginal mesh surgery and laparoscopic mesh sacropexy had similar results [9]. In addition, in one cohort study, QoL was measured after POP surgery with or without mesh and did not differentiate between individuals with and without mesh [31]. All studies investigated the QoL in the first surgery, except one, which evaluated the transvaginal bilateral sacrospinous fixation after the second recurrence of vaginal vault prolapse, which improved the QoL and sexual function [61].

3.3.2. Abdominal Surgeries

Overall, eight [33,47,48,56,74,75,76,87] and two studies [53,54] were dedicated to just laparoscopic or robotic approaches, respectively (Table 5). Four citations compared vaginal-assisted laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy and vaginal hysterectomy with vaginal vault suspension for advanced uterine prolapse, which has similar results [45,49,50,55]. Another study compared two methods of laparoscopic and robotic ventral mesh rectopexy, and the results had no difference [51]. One study compared robotic and vaginal sacropexy with comparable results, and in one study, three methods were compared [46].

Table 5.

The characteristics of the studies on the effectiveness of abdominal surgeries on the quality of life in women with pelvic organ prolapse.

Only one study was on laparotomy [77], and another citation evaluated the difference between vaginal (using native tissue or with a mesh prolapse) and abdominal (open or robotic abdominal sacrocolpopexy), with results in favor of the abdominal group [78].

3.3.3. Pessary Intervention

Three studies compared pessary and surgery [79,80,81] (Table 6). In one, the women who underwent surgery had better QoL [84], whereas in other studies, the QoL after two interventions had no differences. All studies used ring pessaries [28,77], except three citations that used Gellhorn/cube pessaries [58,59,89].

Table 6.

The characteristics of the studies on the effectiveness of pessary on the quality of life in women with pelvic organ prolapse.

3.4. Overall Findings and Meta-Analysis

Almost all interventions, including surgery and pessary interventions, were associated with improved quality of life. In cases where two different surgical or surgical and pessary methods were compared, the results were inconsistent.

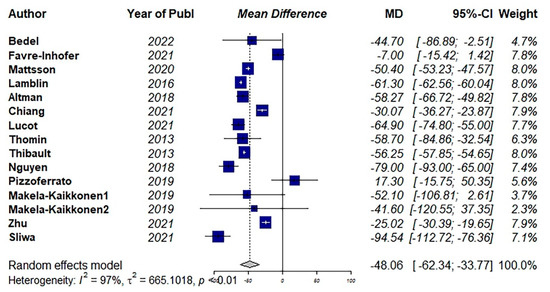

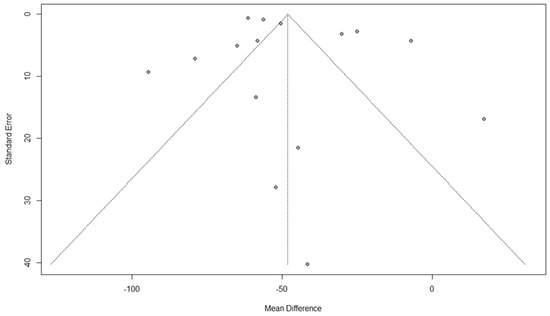

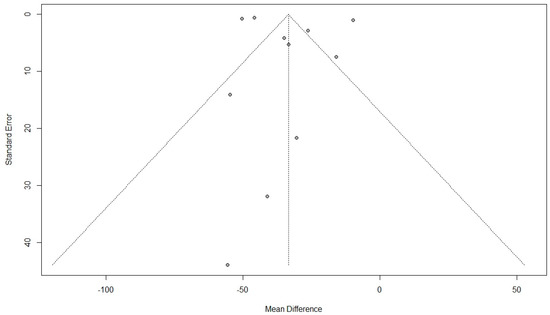

Among the included studies, fifteen studies used the PFDI questionnaire to estimate the QoL [9,31,33,36,37,40,41,42,45,47,51,52,55,56]. The pooled results showed a significant improvement in QoL after surgical interventions (MD: −48.06, 95% CI: −62.34 to −33.77, I2: 97%, p < 0.01) (Figure 3). Visual inspection of the funnel plot and results of Egger’s test for funnel plot asymmetry (p = 0.17) indicated no possible source of publication bias (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Pooled mean difference of the effect of surgical intervention (vaginal and abdominal surgery) on total quality of life score using the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory Questionnaire (PFDI) [31,33,36,37,40,41,42,45,47,51,52,55,56].

Figure 4.

Funnel plot for the results of the effect of surgical intervention (vaginal and abdominal surgery) on total quality of life score using the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory Questionnaire [PFDI].

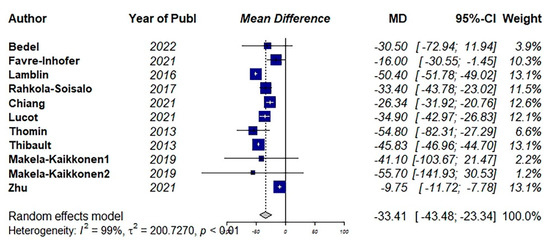

Eleven studies used the PFIQ questionnaire to estimate the QoL [9,36,37,40,42,43,45,51,55,56]. The pooled results showed a significant improvement in QoL after surgical interventions (MD: −33.41, 95% CI: −43.48 to −23.34, I2: 99%, p < 0.01) (Figure 5). Visual inspection of the funnel plot and results of Egger’s test for funnel plot asymmetry (p = 0.52) indicated no possible source of publication bias (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Pooled mean difference of the effect of surgical intervention (vaginal and abdominal surgery) on total quality of life score using Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ) [9,36,37,40,42,43,45,51,55].

Figure 6.

Funnel plot for the results of the effect of surgical intervention (vaginal and abdominal surgery) on total quality of life score using Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ).

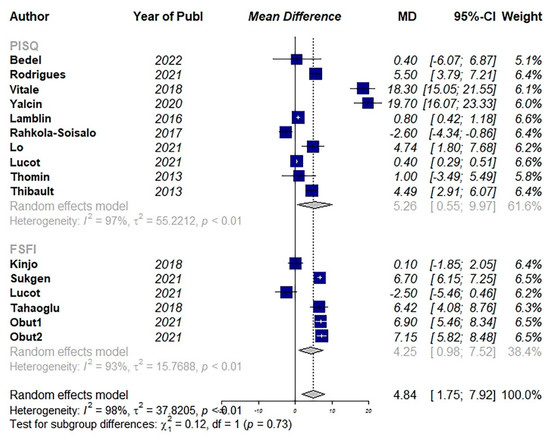

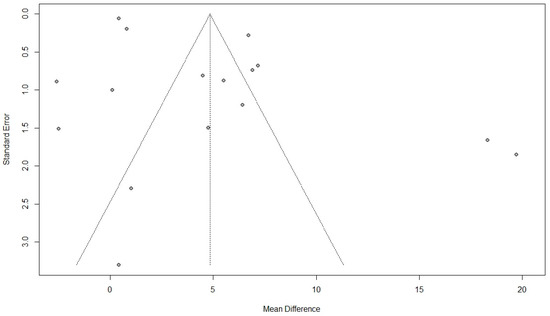

For estimating the effect of surgical intervention on sexual activity, 14 studies were included [9,12,20,24,37,39,42,43,55,56,61,75,76,85]. Among them, 10 studies used the PISQ questionnaire. The pooled results showed a significant improvement in sexual function after surgical interventions (MD: 4.84, 95% CI: 1.75 to 7.92, I2: 98%, p < 0.01) (Figure 7). Visual inspection of the funnel plot and results of Egger’s test for funnel plot asymmetry (p = 0.01) indicated a possible source of publication bias (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Pooled mean difference of the effect of surgical intervention (vaginal and abdominal surgery) on total quality of sexual activity. (PSIQ: Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire, FSFI: Female Sexual Function Index) [9,20,24,37,39,42,43,55,56,61,75,76,85].

Figure 8.

Funnel plot for the results of the effect of surgical intervention (vaginal and abdominal surgery) on total quality of sexual activity.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review, we found that the QoL was significantly improved in women after surgical or pessary interventions for the management of POP. We performed a meta-analysis of QoL and sexual activity questionnaires. The results of the meta-analysis showed a significant association between surgical approach techniques (including vaginal and abdominal surgeries) and improved QoL and sexual activity of patients with POP. Due to vast heterogeneity in the pessary approach and QoL questionnaires used, we were not able to pool the results of studies regarding pessary. However, descriptive analysis showed an improved quality of life in these patients.

Interventional and observational studies dedicated to POP surgeries or using pessaries have grown significantly in the last decade [90,91]. On the other hand, with the emergence of specialized QoL questionnaires for pelvic organ prolapse and its symptoms, we encounter a significant amount of data concerning QoL in different methods [92].

As mentioned before, we divided the studies into three parts based on the intervention approach. In vaginal studies, we also dealt with reconstructive and obliterative methods. Increasing numbers of elderly women and their co-morbidities have increased the preference for obliterative vaginal surgery, due to high levels of durability with lower rates of morbidity. Obliterative methods seem to be a good method for older women who are not sexually active and could not tolerate major surgeries with good durability and relative ease of surgery [90,93]. Few studies evaluated the QoL of patients following obliterative methods. The results of these surgeries were satisfactory, and in two studies that were compared with other methods, the results were contradictory [18,72].

Reconstructive methods using synthetic meshes for pelvic organ prolapse and/or stress urinary incontinence have been popular since the mid-1990s [50]. Mesh repairs were effective as traditional repairs [81] and improve QoL [26]. Patients may benefit from anatomical stability when the risks are justifiable [7], with a low rate of recurrence and few complications [7]. However, reports of mesh-related complications are increasing [7,90], and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently warned about using transvaginal mesh due to adverse events including vaginal erosion, dyspareunia, pain, and infection [57,92]. However, there is no consensus in this regard, and the use of mesh is recommended by some experts.

With regard to abdominal approaches, three different approaches were evaluated in the studies. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy and sacrohysteropexy have been demonstrated to be effective and safe with faster recovery time, shorter operating time, lower blood loss, lower scar tissue, lower pain, and minimally invasive nature compared to the abdominal approaches [94]. However, these procedures have been associated with some complications, such as stress urinary incontinence [95], defecation problems [96], and injuries of the presacral venous plexus [97]. On the other hand, robotic surgeries have recently been introduced with good results and improvement in QoL. A systematic review and meta-analysis showed less intraoperative bleeding, lower incidence of postoperative complications, and shorter hospital stay for RVMR compared with LVMR, but found no differences in rates of recurrence, conversion, or reoperation [98].

Finally, the vaginal pessary is a conservative treatment for pelvic organ prolapse and can be offered as the first-line treatment in most patients [99]. Non-surgical modalities such as pessary are the best choice for older women because most of them have some type of cardiovascular disease [100] or diabetes mellitus [101]. Among various vaginal pessaries, the ring pessary is the most common type because it is convenient to insert and remove and has acceptable continuation rate and manageable adverse events. In addition, a ring with support pessary is a safe and effective conservative treatment for POP; it not only relieves bothersome prolapse and urinary symptoms but also significantly decreases their impacts on health-related QoL. One-quarter of the patients discontinued using pessary mainly due to dissatisfaction with pessary effectiveness or adverse events such as vaginal discharge or vaginal erosion [102]. Some women also prefer surgery after a while. Pessary treatment is continued beyond 12 months after initial placement by 63% of patients [34]. Comparative studies between pessary and surgery are not numerous, and their results are contradictory. In one study, women had the same quality of life [80], while in another study, women who underwent surgery reported a better QoL than pessary users [34].

In this study, we also had some limitations. First, due to the differences in the questionnaires used, variation in follow-up duration, and different methods of surgery, there was a significant amount of heterogeneity in the results of our meta-analysis. Furthermore, we only investigate a limited number of questionnaires available for assessing QoL patients with POP in our quantitative synthesis. However, it is worth noting that the results of other questionnaires were in line with our meta-analysis, which showed improved QoL of these patients after the aforementioned approaches were used. The conclusions of the meta-analysis were made mostly from the results of a limited number of observational studies, which lowers the certainty of evidence because of their observational nature. However, the results of almost all studies included in this systematic review were in line with our findings. Pelvic floor surgeries are relatively new and have made great strides in the last decade. It is suggested that, in future studies, the methods used with mesh be analyzed in a more specialized way.

5. Conclusions

QoL is significantly improved in women after surgical or pessary interventions for management of POP. Due to the daily progress of urogynecological and modern technologies in surgery and less invasive treatments, long-term cohort studies are recommended to evaluate the QoL in these people.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm11237166/s1.

Author Contributions

A.M. and Z.G.: design of the work. M.G. and A.S.: drafting the manuscript. R.S.H., S.P. and P.J.: manuscript editing, interpretation of data. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available due to request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the personnel of Vali-E-Asr Reproductive Health Research Center for their kind help. The protocol of this study was registered with the review board of Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Haylen, B.T.; de Ridder, D.; Freeman, R.M.; Swift, S.E.; Berghmans, B.; Lee, J.; Monga, A.; Petri, E.; Rizk, D.E.; Sand, P.K.; et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2010, 21, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, S.; Stark, D.; Glazener, C.; Sinclair, L.; Ramsay, I. A randomized controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle training for stages I and II pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic. Floor. Dysfunct. 2009, 20, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.A. Pelvic organ prolapse. A new option offers effectiveness and ease of use. Adv. Nurse Pract. 2007, 15, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, T.H.; Hu, T.W. Economic costs of urinary incontinence in 1995. Urology 1998, 51, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natale, F.; La Penna, C.; Padoa, A.; Agostini, M.; Panei, M.; Cervigni, M. High levator myorraphy versus uterosacral ligament suspension for vaginal vault fixation: A prospective, randomized study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2010, 21, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, K.J.; Lee, K.S. Current surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse: Strategies for the improvement of surgical outcomes. Investig. Clin. Urol. 2019, 60, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadenbach-Blome, T.; Grebe, M.; Mengel, M.; Pauli, F.; Greser, A.; Funfgeld, C. Significant Improvement in Quality of Life, Positive Effect on Sexuality, Lasting Reconstructive Result and Low Rate of Complications Following Cystocele Correction Using a Lightweight, Large-Pore, Titanised Polypropylene Mesh: Final Results of a National, Multicentre Observational Study. Geburtshilfe. Frauenheilkd. 2019, 79, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haylen, B.T.; Maher, C.F.; Barber, M.D.; Camargo, S.; Dandolu, V.; Digesu, A.; Goldman, H.B.; Huser, M.; Milani, A.L.; Moran, P.A.; et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Int. Urogynecol. J. 2016, 27, 165–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucot, J.P.; Cosson, M.; Verdun, S.; Debodinance, P.; Bader, G.; Campagne-Loiseau, S.; Salet-Lizee, D.; Akladios, C.; Ferry, P.; De Tayrac, R.; et al. Long-term outcomes of primary cystocele repair by transvaginal mesh surgery versus laparoscopic mesh sacropexy: Extended follow up of the PROSPERE multicentre randomised trial. BJOG 2022, 129, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, S.L.; Clark, A.; Nygaard, I.; Aragaki, A.; Barnabei, V.; McTiernan, A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women’s Health Initiative: Gravity and gravidity. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M.D.; Walters, M.D.; Bump, R.C. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 193, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinjo, M.; Yoshimura, Y.; Kitagawa, Y.; Okegawa, T.; Nutahara, K. Sexual activity and quality of life in Japanese pelvic organ prolapse patients after transvaginal mesh surgery. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2018, 44, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doaee, M.; Moradi-Lakeh, M.; Nourmohammadi, A.; Razavi-Ratki, S.K.; Nojomi, M. Management of pelvic organ prolapse and quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2014, 25, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies [Internet]. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Sharma, R.; Iovine, C.; Agarwal, A.; Henkel, R. TUNEL assay-Standardized method for testing sperm DNA fragmentation. Andrologia 2021, 53, e13738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhital, R.; Otsuka, K.; Poudel, K.C.; Yasuoka, J.; Dangal, G.; Jimba, M. Improved quality of life after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse in Nepalese women. BMC Women’s Health 2013, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghali, M.M.; Abdelzaher, A.; Abdelazim, I.A. Surgical and quality of life outcomes after pelvic organ prolapse surgery in older postmenopausal women. Menopause Rev. Przegląd Menopauzalny 2021, 20, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayondo, M.; Kaye, D.K.; Migisha, R.; Tugume, R.; Kato, P.K.; Lugobe, H.M.; Geissbuehler, V. Impact of surgery on quality of life of Ugandan women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: A prospective cohort study. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.; Rodrigues, C.; Negrao, L.; Afreixo, V.; Castro, M.G. Female sexual function and quality of life after pelvic floor surgery: A prospective observational study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021, 32, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefni, M.; Barry, J.A.; Koukoura, O.; Meredith, J.; Mossa, M.; Edmonds, S. Long-term quality of life and patient satisfaction following anterior vaginal mesh repair for cystocele. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013, 287, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L.C.; Bezerra, L.; Bilhar, A.P.M.; Neto, J.A.V.; Vasconcelos, C.T.M.; Saboia, D.M.; Karbage, S.A.L. Symptomatic and anatomic improvement of pelvic organ prolapse in vaginal pessary users. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021, 32, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belayneh, T.; Gebeyehu, A.; Adefris, M.; Rortveit, G.; Gjerde, J.L.; Ayele, T.A. Pelvic organ prolapse surgery and health-related quality of life: A follow-up study. BMC. Womens. Health 2021, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalcin, Y.; Demir Caltekin, M.; Eris Yalcin, S. Quality of life and sexuality after bilateral sacrospinous fixation with vaginal hysterectomy for treatment of primary pelvic organ prolapse. LUTS Low. Urin. Tract Symptoms 2020, 12, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukgen, G.; Turkay, U. Effect of Pelvic Organ Prolapse Reconstructive Mesh Surgery on the Quality of Life of Turkish Patients: A Prospective Study. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2020, 9, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartuzi, A.; Futyma, K.; Kulik-Rechberger, B.; Rechberger, T. Self-perceived quality of life after pelvic organ prolapse reconstructive mesh surgery: Prospective study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 169, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agacayak, E.; Bulut, M.; Peker, N.; Gunduz, R.; Tunc, S.Y.; Evsen, M.S.; Gul, T. Comparison of long-term results of obliterative colpocleisis and reconstructive vaginal surgery including sacrospinous ligament fixation in patients with total genital prolapse. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2022, 25, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, S.C.A.; Marangoni-Junior, M.; Brito, L.G.O.; Castro, E.B.; Juliato, C.R.T. Quality of life and vaginal symptoms of postmenopausal women using pessary for pelvic organ prolapse: A prospective study. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. (1992) 2018, 64, 1103–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakai, K.; Hamuro, A.; Kitada, K.; Tahara, M.; Misugi, T.; Nakano, A.; Koyama, M.; Tachibana, D. Preliminary evaluation of the short-term outcomes of polytetrafluoroethylene mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2021, 47, 2529–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiger, B.B.; da Silva Carramão, S.; Del Roy, C.A.; da Silva, T.T.; Hwang, S.M.; Auge, A.P.F. Vaginal pessary in advanced pelvic organ prolapse: Impact on quality of life. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022, 33, 2013–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, N.K.; Karjalainen, P.K.; Tolppanen, A.M.; Heikkinen, A.M.; Sintonen, H.; Harkki, P.; Nieminen, K.; Jalkanen, J. Pelvic organ prolapse surgery and quality of life-a nationwide cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 581.e1–588.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husch, T.; Mager, R.; Ober, E.; Bentler, R.; Ulm, K.; Haferkamp, A. Quality of life in women of non-reproductive age with transvaginal mesh repair for pelvic organ prolapse: A cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2016, 33 Pt. A, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzoferrato, A.C.; Fermaut, M.; Varas, C.; Fauconnier, A.; Bader, G. Medium-term outcomes of laparoscopic sacropexy on symptoms and quality of life. Predict. Factors Postoper. Dissatisfact. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2019, 30, 2085–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thys, S.; Hakvoort, R.; Milani, A.; Roovers, J.P.; Vollebregt, A. Can we predict continued pessary use as primary treatment in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse (POP)? A prospective cohort study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021, 32, 2159–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewski, M.; Kołodyńska, G.; Mucha, A.; Bełza, Ł.; Nowak, K.; Andrzejewski, W. The assessment of quality of life and satisfaction with life of patients before and after surgery of an isolated apical defect using synthetic materials. BMC Urol. 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favre-Inhofer, A.; Carbonnel, M.; Murtada, R.; Revaux, A.; Asmar, J.; Ayoubi, J.M. Sacrospinous ligament fixation: Medium and long-term anatomical results, functional and quality of life results. BMC. Women’s Health 2021, 21, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedel, A.; AgostinI, A.; Netter, A.; Pivano, A.; Caroline, R.; Tourette, C. Midline rectovaginal fascial plication: Anatomical and functional outcomes at one year. J. Gynecol. Obstetr. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 51, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelovsek, J.E.; Barber, M.D.; Brubaker, L.; Norton, P.; Gantz, M.; Richter, H.E.; Weidner, A.; Menefee, S.; Schaffer, J.; Pugh, N.; et al. Effect of Uterosacral Ligament Suspension vs Sacrospinous Ligament Fixation With or Without Perioperative Behavioral Therapy for Pelvic Organ Vaginal Prolapse on Surgical Outcomes and Prolapse Symptoms at 5 Years in the OPTIMAL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 319, 1554–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, T.S.; Ng, K.L.; Huang, T.X.; Chen, Y.P.; Lin, Y.H.; Hsieh, W.C. Anterior-Apical Transvaginal Mesh (Surelift) for Advanced Urogenital Prolapse: Surgical and Functional Outcomes at 1 Year. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 28, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, C.H.; Hsu, C.S.; Ding, D.C. The Comparison of Outcomes of Transvaginal Mesh Surgery with and without Midline Fascial Plication for the Treatment of Anterior Vaginal Prolapse: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, D.; Geale, K.; Falconer, C.; Morcos, E. A generic health-related quality of life instrument for assessing pelvic organ prolapse surgery: Correlation with condition-specific outcome measures. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018, 29, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamblin, G.; Gouttenoire, C.; Panel, L.; Moret, S.; Chene, G.; Courtieu, C. A retrospective comparison of two vaginal mesh kits in the management of anterior and apical vaginal prolapse: Long-term results for apical fixation and quality of life. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2016, 27, 1847–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahkola-Soisalo, P.; Altman, D.; Falconer, C.; Morcos, E.; Rudnicki, M.; Mikkola, T.S. Quality of life after Uphold Vaginal Support System surgery for apical pelvic organ prolapse-A prospective multicenter study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 208, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Haddad, R.; Svabik, K.; Masata, J.; Koleska, T.; Hubka, P.; Martan, A. Women’s quality of life and sexual function after transvaginal anterior repair with mesh insertion. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 167, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, X. A comparison of modified laparoscopic uterine suspension and vaginal hysterectomy with sacrospinous ligament fixation for treating pelvic organ prolapse. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 5672–5678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Zanten, F.; Lenters, E.; Broeders, I.A.M.J.; Schraffordt Koops, S.E. Robot-assisted sacrocolpopexy: Not only for vaginal vault suspension? An observational cohort study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliwa, J.; Kryza-Ottou, A.; Grobelak, J.; Domagala, Z.; Zimmer, M. Anterior abdominal fixation - a new option in the surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Ginekol. Pol. 2021, 92, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karslı, A.; Karslı, O.; Kale, A. Laparoscopic Pectopexy: An Effective Procedure for Pelvic Organ Prolapse with an Evident Improvement on Quality of Life. Prague Med. Rep. 2021, 122, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cengiz, H.; Yildiz, S.; Alay, I.; Kaya, C.; Eren, E.; Iliman, D. Vaginal-Assisted laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy and vaginal hysterectomy with vaginal vault suspension for advanced uterine prolapse: 12-month preliminary results of a randomized controlled study. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2021, 10, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okcu, N.T.; Gürbüz, T.; Uysal, G. Comparison of patients undergoing vaginal hysterectomy with sacrospinous ligament fixation, laparoscopic hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy and abdominal hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy in terms of postoperative quality of life and sexual function. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 50, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makela-Kaikkonen, J.; Rautio, T.; Ohinmaa, A.; Koivurova, S.; Ohtonen, P.; Sintonen, H.; Makela, J. Cost-analysis and quality of life after laparoscopic and robotic ventral mesh rectopexy for posterior compartment prolapse: A randomized trial. Technol. Coloproctol. 2019, 23, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.N.; Gruner, M.; Killinger, K.A.; Peters, K.M.; Boura, J.A.; Jankowski, M.; Sirls, L.T. Additional treatments, satisfaction, symptoms and quality of life in women 1 year after vaginal and abdominal pelvic organ prolapse repair. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2018, 50, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimminck, K.; Mourik, S.L.; Tjin-Asjoe, F.; Martens, J.; Aktas, M. Long-term follow-up and quality of life after robot assisted sacrohysteropexy. Eur. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. Reproduct. Biol. 2016, 206, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linder, B.J.; Chow, G.K.; Elliott, D.S. Long-term quality of life outcomes and retreatment rates after robotic sacrocolpopexy. Int. J. Urol. 2015, 22, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomin, A.; Touboul, C.; Hequet, D.; Zilberman, S.; Ballester, M.; Daraï, E. Genital prolapse repair with Avaulta Plus® mesh: Functional results and quality of life. Progres. En. Urologie. 2013, 23, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thibault, F.; Costa, P.; Thanigasalam, R.; Seni, G.; Brouzyine, M.; Cayzergues, L.; De Tayrac, R.; Droupy, S.; Wagner, L. Impact of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy on symptoms, health-related quality of life and sexuality: A medium-term analysis. BJU Int. 2013, 112, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, C.S.; Brown, H.W.; Shippey, S.S.; Gutman, R.E.; Andy, U.U.; Yurteri-Kaplan, L.A.; Kudish, B.; Mehr, A.; O’Boyle, A.; Foster, R.T., Sr.; et al. Generic Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients Seeking Care for Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 27, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Han, J.; Zhu, F.; Wang, Y. Ring and Gellhorn pessaries used in patients with pelvic organ prolapse: A retrospective study of 8 years. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 298, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenfelde, S.; Tell, D.; Thomas, T.N.; Kenton, K. Quality of life in women who use pessaries for longer than 12 months. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 21, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, S.Y. The effect of reconstructive vaginal surgery on quality of life and sexual functions in postmenopausal women with advanced pelvic organ prolapse in intermediate-term follow-up. Post Reprod. Health 2021, 27, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S.G.; Lagana, A.S.; Noventa, M.; Giampaolino, P.; Zizolfi, B.; Buttice, S.; La Rosa, V.L.; Gullo, G.; Rossetti, D. Transvaginal Bilateral Sacrospinous Fixation after Second Recurrence of Vaginal Vault Prolapse: Efficacy and Impact on Quality of Life and Sexuality. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 5727165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deltetto, F.; Favilli, A.; Buzzaccarini, G.; Vitagliano, A. Effectiveness and Safety of Posterior Vaginal Repair with Single-Incision, Ultralightweight, Monofilament Propylene Mesh: First Evidence from a Case Series with Short-Term Results. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 3204145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derpapas, A.; Vijaya, G.; Nikolopoulos, K.; Nikolopoulos, M.; Robinson, D.; Fernando, R.; Khullar, V. The use of 3D ultrasound in comparing surgical techniques for posterior wall prolapse repair: A pilot randomised controlled trial. J. Obstetr. Gynaecol. 2021, 41, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechberger, E.; Skorupska, K.; Rechberger, T.; Wojtaś, M.; Miotła, P.; Kulik-rechberger, B.; Wróbel, A. The influence of vaginal native tissues pelvic floor reconstructive surgery in patients with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse on preexisting storage lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klapdor, R.; Grosse, J.; Hertel, B.; Hillemanns, P.; Hertel, H. Postoperative anatomic and quality-of-life outcomes after vaginal sacrocolporectopexy for vaginal vault prolapse. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstetr. 2017, 137, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, M.S.; Cavalcanti Gde, A.; da Costa, A.A. Fascial surgical repair for vaginal prolapse: Effect on quality of life and related symptoms. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014, 182, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alt, C.D.; Benner, L.; Mokry, T.; Lenz, F.; Hallscheidt, P.; Sohn, C.; Kauczor, H.U.; Brocker, K.A. Five-year outcome after pelvic floor reconstructive surgery: Evaluation using dynamic magnetic resonance imaging compared to clinical examination and quality-of-life questionnaire. Acta Radiol. 2018, 59, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funfgeld, C.; Stehle, M.; Henne, B.; Kaufhold, J.; Watermann, D.; Grebe, M.; Mengel, M. Quality of Life, Sexuality, Anatomical Results and Side-effects of Implantation of an Alloplastic Mesh for Cystocele Correction at Follow-up after 36 Months. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017, 77, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buca, D.I.; Leombroni, M.; Falo, E.; Bruno, M.; Santarelli, A.; Frondaroli, F.; Liberati, M.; Fanfani, F. A 2-Year Evaluation of Quality of Life Outcomes of Patients With Pelvic Organ Prolapse Treated With an Elevate Prolapse Repair System. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 22, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farthmann, J.; Watermann, D.; Erbes, T.; Roth, K.; Nanovska, P.; Gitsch, G.; Gabriel, B. Functional outcome after pelvic floor reconstructive surgery with or without concomitant hysterectomy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 291, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertas, I.E.; Balıkoğlu, M.; Biler, A. Le Fort colpocleisis: An evaluation of results and quality of life at intermediate-term follow-up. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 50, 102069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petcharopas, A.; Wongtra-Ngan, S.; Chinthakanan, O. Quality of life following vaginal reconstructive versus obliterative surgery for treating advanced pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018, 29, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeniel, A.O.; Ergenoglu, A.M.; Askar, N.; Itil, I.M.; Meseri, R. Quality of life scores improve in women undergoing colpocleisis: A pilot study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012, 163, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbaba, E.; Sezgin, B. Modified laparoscopic lateral suspension with a five-arm mesh in pelvic organ prolapse surgery. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obut, M.; Oglak, S.C.; Akgol, S. Comparison of the Quality of Life and Female Sexual Function Following Laparoscopic Pectopexy and Laparoscopic Sacrohysteropexy in Apical Prolapse Patients. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2021, 10, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahaoglu, A.E.; Bakir, M.S.; Peker, N.; Bagli, I.; Tayyar, A.T. Modified laparoscopic pectopexy: Short-term follow-up and its effects on sexual function and quality of life. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018, 29, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchana, T.; Bunyavejchevin, S. Impact on quality of life after ring pessary use for pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2012, 23, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brocker, K.A.; Alt, C.D.; Rzepka, J.; Sohn, C.; Hallscheidt, P. One-year dynamic MRI follow-up after vaginal mesh repair: Evaluation of clinical, radiological, and quality-of-life results. Acta Radiol. 2015, 56, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım Karaca, S.; Ertaş, İ.E. Comparison of life quality between geriatric patients who underwent reconstructive surgery and obliterative surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Ginekol. Pol. 2021, 92, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lone, F.; Thakar, R.; Sultan, A.H. One-year prospective comparison of vaginal pessaries and surgery for pelvic organ prolapse using the validated ICIQ-VS and ICIQ-UI (SF) questionnaires. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2015, 26, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Altilia, N.; Mancini, V.; Falagario, U.; Chirico, M.; Illiano, E.; Balzarro, M.; Annese, P.; Busetto, G.M.; Bettocchi, C.; Cormio, L.; et al. Are Two Meshes Better than One in Sacrocolpopexy for Pelvic Organ Prolapse? Comparison of Single Anterior versus Anterior and Posterior Vaginal Mesh Procedures. Urol. Int. 2022, 106, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, G.; Hüsch, T.; Mörgeli, C.; Kolterer, A.; Tunn, R. Mesh-augmented transvaginal repair of recurrent or complex anterior pelvic organ prolapse in accordance with the SCENIHR opinion. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021, 32, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesil, A.; Watermann, D.; Farthmann, J. Mesh implantation for pelvic organ prolapse improves quality of life. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 289, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlin, G.L.; Morgenbesser, R.; Kimberger, O.; Umek, W.; Bodner, K.; Bodner-Adler, B. Does the choice of pelvic organ prolapse treatment influence subjective pelvic-floor related quality of life? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 259, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukgen, G.; Altunkol, A.; Yiğit, A. Effects of mesh surgery on sexual function in pelvic prolapse and urinary incontinence. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2021, 47, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsara, A.; Wight, E.; Heinzelmann-Schwarz, V.; Kavvadias, T. Long-term quality of life, satisfaction, pelvic floor symptoms and regret after colpocleisis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 294, 999–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido Luque, J.; Limón Padilla, J.; García Moreno, J.; Pascual Salvador, E.; Gomez Menchero, J.; Suarez Grau, J.M.; Guadalajara Jurado, J. Three years prospective clinical and radiologic follow-up of laparoscopic sacrocolpoperineopexy. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 5980–5990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majkusiak, W.; Horosz, E.; Tomasik, P.; Zwierzchowska, A.; Wielgos, M.; Barcz, E. Quality of life assessment in women after cervicosacropexy with polypropylene mesh for pelvic organ prolapse: A preliminary study. Prz. Menopauz. 2015, 14, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Ai, F.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, J.; Liang, S.; Xu, T.; Zhu, L. Changes in the symptoms and quality of life of women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse fitted with a ring with support pessary. Maturitas 2018, 117, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, R.; Linder, B.J. Evaluation and Management of Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Mayo. Clinic. Proceed. 2021, 96, 3122–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowat, A.; Maher, D.; Baessler, K.; Christmann-Schmid, C.; Haya, N.; Maher, C. Surgery for women with posterior compartment prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 3, Cd012975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, M.; Hayward, L. Pelvic Floor Dysfunction And Its Effect On Quality Of Sexual Life. Sexual. Med. Rev. 2019, 7, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, G.; Lafuente, R.; Checa, M.A.; Carreras, R.; Brassesco, M. Diagnostic value of sperm DNA fragmentation and sperm high-magnification for predicting outcome of assisted reproduction treatment. Asian. J. Androl. 2013, 15, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noe, K.G.; Spuntrup, C.; Anapolski, M. Laparoscopic pectopexy: A randomised comparative clinical trial of standard laparoscopic sacral colpo-cervicopexy to the new laparoscopic pectopexy. Short-Term Postoper. Results. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013, 287, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Kassis, N.; Atallah, D.; Moukarzel, M.; Ghaname, W.; Chalouhy, C.; Suidan, J.; Villet, R.; Salet-Lizee, D. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women: How to choose the best approach. J. Med. Libanais 2013, 61, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercoli, A.; Cosma, S.; Riboni, F.; Campagna, G.; Petruzzelli, P.; Surico, D.; Danese, S.; Scambia, G.; Benedetto, C. Laparoscopic Nerve-Preserving Sacropexy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2017, 24, 1075–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celentano, V.; Ausobsky, J.R.; Vowden, P. Surgical management of presacral bleeding. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2014, 96, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rondelli, F.; Bugiantella, W.; Villa, F.; Sanguinetti, A.; Boni, M.; Mariani, E.; Avenia, N. Robot-assisted or conventional laparoscoic rectopexy for rectal prolapse? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12 Suppl. 2, S153–S159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Olsen, A.L.; Smith, V.J.; Bergstrom, J.O.; Colling, J.C.; Clark, A.L. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 89, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quagliariello, V.; Passariello, M.; Rea, D.; Barbieri, A.; Iovine, M.; Bonelli, A.; Caronna, A.; Botti, G.; De Lorenzo, C.; Maurea, N. Evidences of CTLA-4 and PD-1 Blocking Agents-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Cellular and Preclinical Models. J. Personal. Med. 2020, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quagliariello, V.; De Laurentiis, M.; Rea, D.; Barbieri, A.; Monti, M.G.; Carbone, A.; Paccone, A.; Altucci, L.; Conte, M.; Canale, M.L.; et al. The SGLT-2 inhibitor empagliflozin improves myocardial strain, reduces cardiac fibrosis and pro-inflammatory cytokines in non-diabetic mice treated with doxorubicin. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.A.; Harmanli, O. Pessary use in pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 3, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).