Abstract

Background: Orthopedic surgery typically results in moderate to severe pain in a majority of patients. Opioids were traditionally the primary medication to target mechanisms of pain transmission. Multimodal analgesia has become a preferred method of pain management in orthopedic practice. Utilizing more than one mode to address post-surgical pain by recruiting multiple receptors through different medications accelerates the recovery process and decreases the need for opioids. By implementing effective analgesic techniques and interventions, this practice, in turn, decreases the usage of perioperative opioids, and in the long term, prevents addiction to pain medications and risk of opioid overdose. In orthopedic surgeries, previous studies have found that multimodal analgesia has reduced early opioid usage in the postoperative course. Pain is the result of direct injury to the nervous system, with a wide variety of chemicals directly stimulating or sensitizing the peripheral nociceptors. The pathophysiology behind the mechanism of post-surgical pain, along with the importance of preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative pain regimens are emphasized. A brief overview of pain medications and their properties is provided. These medications are further categorized, with information on special considerations and typical dosage requirements. Pain management should address both neuropathic and subjective types of pain. Effective pain control requires constant reassessment with individualized strategies. Conclusion: By focusing on multimodal analgesia, anesthesiologists can now utilize newer techniques for postoperative pain relief from orthopedic surgery, with better short-term and long-term outcomes for the patient.

1. Introduction

Deaths due to drug overdose have become an epidemic in the United States [1]. Between 1999 and 2016, more than 600,000 people died from drug overdoses, mostly related to opioids prescribed for pain [2]. Nearly half of the patients who take opioids for at least 3 months remain on opioids 5 years later and are likely to become lifelong users [3,4,5,6]. Orthopedic procedures are considered one of the most painful procedures a patient can undergo.

According to the revised International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) definition, pain is “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage” [7]. Orthopedic surgery, especially total joint replacement, results in moderate to severe pain in a majority of patients. Improvements in pain management have been amongst the most substantial advancements in the practice of total joint replacement surgery [8]. Appropriate treatment of pain in these patients promotes healing, shortens length of recovery, and improves quality of life after surgery. Pain has become the “fifth vital sign” in the view of the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) and demands consideration in the care of all patients. Pain not only needs to be considered during the discharge decision but also during the entire inpatient and outpatient course [9]. Pain demands treatment, and failure to provide adequate treatment can result in medico legal action [10]. Ever since Professor Henrik Kehlet introduced the concept of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS), multimodal analgesia became a preferred method of pain management. It includes preoperative, perioperative, and post-operative components and calls for a multidisciplinary collaboration between patients, surgeons, anesthesiologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and nursing staff. Using more than one mode, including psychotherapy, physical therapy, regional anesthesia, local injections, and nonopioid medications, to address post-surgical pain results in superior pain control and accelerates the recovery process with less need for opioids, therefore decreasing the potential risk of abuse. Previous literature has shown that multimodal analgesia has decreased the length of stay and pain in the first 24 h after foot and ankle surgery. By adding periarticular injections to standard pain control for hip hemiarthroplasty, opioid usage was reduced postoperatively. Surgical site injections for femoral fracture and upper extremity procedures showed improved pain and overall increased patient satisfaction [1]. In this article, the role of multimodal analgesia in adult patients undergoing orthopedic surgery is discussed.

2. Mechanism of Post-Surgical Pain

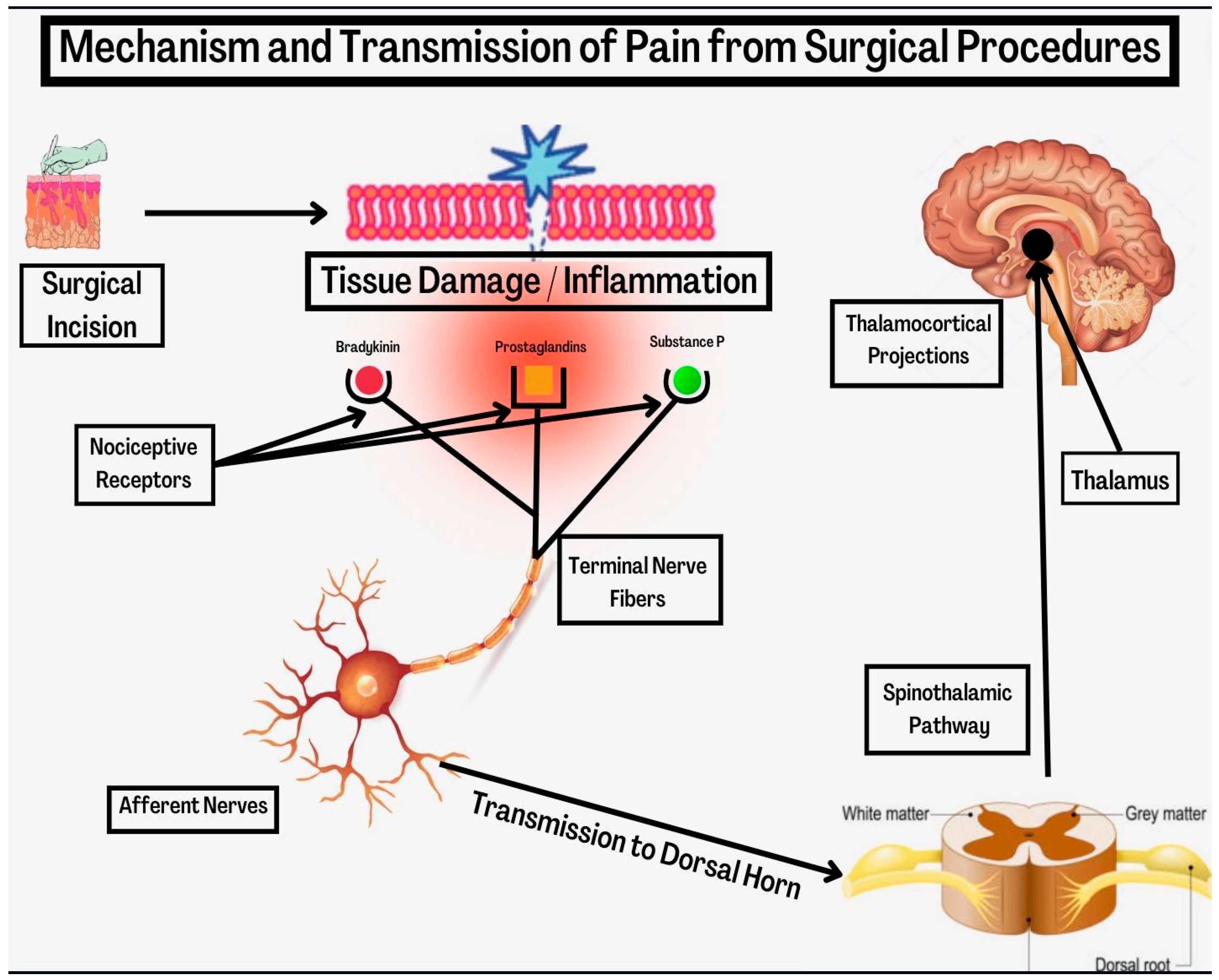

The generation of pain after surgical procedures is complex. Studying pain physiology and transmission is important in understanding its treatment. Depending on how it is transmitted, pain can be classified as nociceptive or neuropathic. Tissue damage results in the activation of nociceptive receptors which are present in the terminal nerve fibers [11]. From there, signals are transmitted through afferent neurons to the dorsal horn, and then through the ascending spinothalamic pathways and thalamocortical projections to higher neural centers in the cerebral cortex [12]. Once there, the pain experience is dictated by the thalamus and cortical modulation. Figure 1 displays the mechanism and transmission of pain signals from tissue injury. This experience is affected by the patient’s personality, sex, emotional state, pain behavior and their culture. Further modulation occurs in the medulla, descending pathways, and dorsal horn of the spinal cord.

Figure 1.

Mechanism and transmission of pain from surgical procedures.

Neuropathic pain is the result of direct injury to the nervous system whether it is a peripheral nerve, a nerve root, or spinal cord. It is mediated mostly by A delta and C fibers, but also larger A beta fibers [9]. These fibers innervate both skin and internal organs, including the periosteum, joints, viscera, and muscles. The large A beta fibers often cause responses that are out of proportion to the intensity of stimulus such as allodynia, hyperpathia and dysesthesia [9].

A wide variety of chemicals can directly stimulate or sensitize peripheral nociceptors. These chemicals, or ligands, are each associated with a neural receptor, and each can act as a neurotransmitter. They are released in response to tissue injury and increase the intensity of neuronal stimulation or sensitization or cause local extravasation of inflammatory mediators [12]. These agents include bradykinin, prostaglandin, serotonin, histamine, acetylcholine, potassium ions, and hydrogen ions.

Bradykinin, potassium, and acetylcholine directly activate nociceptors. Prostaglandins do not directly activate nociceptors but are very effective in sensitizing them to further activation by other chemicals [12]. Neurogenic inflammation results because action potentials in an activated neuron travel not only from the periphery to the central nervous system but also antidromically to the periphery, resulting in the release of neuropeptides from the nociceptive terminal [13]. Substance P is one such vasoactive neuropeptide that causes local vasodilation and extravasation. It is released by local free nerve endings around the site of injury and is responsible for further release of bradykinin [14]. Substance P also stimulates the release of histamine and serotonin. Prostaglandins are produced by the action of phospholipase A. Phospholipase A may be stimulated by endogenous chemicals, such as catecholamines, and by local trauma.

If the peripheral pain stimulus is intense and of sufficient duration, the phenomenon of secondary hyperalgesia (hypersensitivity of the area surrounding the initial injury site) and central sensitization may occur. Hyperalgesia is thought to be mediated through the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor [9]. Central sensitization or wind up is a phenomenon where low threshold benign sensory input evokes a response from nociceptive receptors which normally respond only to painful stimulus. Once it is established, this is difficult to treat.

3. Role of the Anesthesiologist

The role of the anesthesiologist as a perioperative physician in the management of orthopedic patients cannot be overemphasized. Even as patients are preparing for surgery, optimizing patients with input from anesthesiologists is important. In addition to addressing general health conditions, weaning patients preoperatively from opioids seems to improve the outcomes in patients, especially those undergoing total joint replacements. The anesthesiologist plays a central role, ensuring accelerated and safe recovery of the patient from surgery. Using techniques which minimize or eliminate the need for general anesthesia decreases the risk of nausea, vomiting and shortens recovery period. Using regional anesthetic techniques successfully where applicable, as a part of multimodal analgesia is a testimony to the skill of the anesthesiologist. Adequate pain control aids in recovery and increases overall patient satisfaction while decreasing the overall cost of care.

4. Methods of Analgesia

Multimodal analgesia is defined as the use of more than one modality of pain control to achieve effective analgesia while reducing opioid-related side effects [15]. Traditionally, the treatment of postoperative pain mainly consisted of the administration of opioids which was not only unsatisfactory, but often resulted in multiple side effects including, respiratory depression, ileus, nausea and vomiting, sedation, and urinary retention which impeded recovery. Prolonged dependency on these medications led to chronic addiction. As the understanding of pain mechanisms has improved, the development of different groups of medications to address pain has also advanced. Multimodal analgesia is based on the principle that combining analgesics with different modes or sites of action will result in better pain control and less side effects through opioid sparing. When used as a part of enhanced recovery protocols, this implementation will accelerate functional recovery, decrease hospital costs, and improve patient satisfaction and outcomes.

4.1. Pre-Emptive Analgesia

Pre-emptive analgesia refers to administration of pain medications or performing procedures before the surgical incision to prevent surgical pain. It is more effective than the same intervention when started after surgery [16]. Pre-emptive analgesia is intended to prevent peripheral and central hypersensitivity, decrease the incidence of hyperalgesia, and reduce the intensity of postoperative pain [17]. The concept was originally introduced by Crile, over a century ago, based on clinical observation and was later studied by Wall and Woolf [18,19]. The concept was based mainly on animal studies and later human studies followed. Pre-emptive analgesia has a protective effect on the nociceptive system, which could significantly reduce the level of pain and decrease the risk for the development of chronic pain [19]. A combination of Cox-2 inhibitors and pregabalin, given between half an hour and one hour before the surgery, seems to decrease the intensity of postoperative pain after total joint replacements and enable faster recovery. Administration of Ketamine prior to incision, sometimes followed by an infusion, also significantly reduced the need for pos- operative pain medications and seems to play a role in decreasing development of chronic pain by preventing neuromodulation. Performing peripheral nerve blocks where possible prior to the surgical incision decreases the need for supplemental pain medications during and after the surgical procedure. Although initial clinical trials have been inconclusive, the concept of pre-emptive analgesia is an important part of multimodal analgesia regimens.

4.2. Surgical Site Infiltration

Infiltration of local anesthetics sometimes in combination with other medications has been one approach used by surgeons to prolong the duration of local analgesia. These medications work by directly preventing the generation and conduction of pain signals from the incision site [20]. Intra-articular injections of slow-release formulations of bupivacaine have been shown to extend the duration of pain relief and decrease the need for supplementation [20]. Newer combinations of local anesthetics with anti-inflammatory properties are also being developed. Each of these techniques is operator dependent and there might be a variation in the success rate. The risk of toxicity when administering large doses of local anesthetics and a potential for chondrolysis when injected into the joints have limited the use of these techniques [20]. Nonetheless, surgical site infiltration can be a good adjuvant to systemic analgesics and forms an important part of multimodal analgesia.

4.3. Analgesic Techniques

Analgesic techniques can be pharmacological or non-pharmacological. Pharmacological techniques include central neuraxial techniques, regional anesthesia, and systemically administered medications. The non-pharmacological techniques involve acupuncture, aromatherapy, music therapy, application of hot and cold compresses, elevation of surgical extremity, transcutaneous nerve stimulation, peripheral nerve stimulation and hypnosis.

4.4. Central Neuraxial, Regional and Local Analgesia

The use of epidural analgesia has been shown to reduce the requirement for opioids. It has been proven to decrease the surgical stress response, thromboembolic phenomenon, cardiac arrhythmias, pulmonary complications (atelectasis, pneumonia) and earlier return of bowel function [21]. Spinal analgesia with low doses of local anesthetics has also been shown to be effective. Both techniques can be used as a part of multimodal analgesia. Epidural administration is not suitable for outpatient procedures and when early ambulation is desired [21]. Caution should be exercised when central neuraxial techniques are used in combination with antithrombotic agents.

4.5. Regional Anesthesia

Use of regional nerve blocks as adjuvants for pain management has evolved into the most favored approach, especially in orthopedic surgeries involving upper extremities [22]. Brachial plexus nerve blocks via interscalene, axillary, supraclavicular and infraclavicular approach, when performed under ultrasound guidance are highly successful. Other nerve blocks at the elbow, wrist, and digital nerve blocks provide ideal pain relief for certain procedures.

For surgeries involving the lower extremity, lumbar plexus block, femoral nerve block, adductor canal block, and popliteal blocks are also very effective for providing regional analgesia [22]. Newer blocks such as Infiltration Between Popliteal Artery and Capsule of the Knee (iPACK), Pericapsular Nerve Group Block 4 (PENG), and Erector Spinae Plane (ESP) performed by experienced anesthesiologists under ultrasound guidance are also very effective in controlling post-operative pain.

4.6. Patient Controlled Analgesia

Patients can control the dose of analgesia they receive through a programmable pump. The pump limits the maximum dose, and hence, decreases the chance of dangerous side effects [23]. A continuous infusion, often combined with boluses, can be used for control of postoperative pain. The most commonly used medications are morphine, fentanyl, and hydromorphone, along with local anesthetic agents. Patients are prone to have the same side effects as parenteral opioids, such as nausea, vomiting, pruritus, drowsiness, ileus, and urinary retention; therefore, these pumps have fallen out of favor [23].

5. Systemic Analgesics

Systemic analgesics can be administered intravenously (IV), intramuscularly (IM), or orally (PO). In the immediate post-operative period, IV medications are administered to get pain under control. Oral medications are administered as early as feasible, keeping in mind the time taken for onset of action. As a part of enhanced recovery protocols, some oral pain medications are administered pre-emptively before the surgery, for analgesia to take effect by the time anesthesia wears off. The goal is to minimize the administration of IV pain medications to decrease the risk of adverse effects [24]. These medications include opioids and non-opioids such as acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists, anticonvulsants (e.g., gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) analogues), beta-blockers, alpha-2 agonists, transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor agonists (capsaicin), glucocorticoids and magnesium. Please refer to the tables below for more information regarding these classes of medications.

5.1. Opioids

Opioids have been the mainstay for the management of postoperative pain for many years. Their use is limited by side effects such as nausea and vomiting, respiratory depression, ileus, pruritus, and urinary retention, along with carrying a dangerous risk of addiction. With efficient use of nonopioids, opioids can be mainly used as rescue medications when pain is not well controlled with other methods. Table 1 highlights the most commonly used medications for orthopedic surgeries.

Table 1.

Opioids [25,26].

5.2. Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen is an effective analgesic for mild to moderate pain. When used as an opioid adjunct, oral or rectal acetaminophen reduces pain intensity and opioid consumption by up to 30% [27,28]. Both acetaminophen and NSAIDs act by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis. Acetaminophen has a very favorable safety profile and adverse effects are rare [29]. Table 2 highlights this medication for orthopedic surgeries.

5.3. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs can be classified as specific cyclooxygenase (COX) 2 inhibitors and nonspecific inhibitors of COX 1 and COX 2. COX 1 inhibitors are associated with increased risk of surgical site bleeding, gastrointestinal ulceration, and renal dysfunction [30]. COX 2 inhibitors have fewer side effects and have been shown to decrease opioid requirements and have been shown to contribute to a quicker recovery after surgery [31]. Table 2 highlights this class of medications for orthopedic surgeries.

5.4. N-Methyl D-Aspartate (NMDA) Receptor Antagonists

NMDA receptors are involved in the development of pathological pain states such as hyperalgesia and development of chronic pain. Ketamine is a NMDA antagonist which when given before the incision has been shown to decrease the opioid requirement and development of chronic postsurgical pain [32]. Other NMDA receptor antagonists include dextromethorphan, memantine, and magnesium sulfate which have less predictable actions. NMDA receptor antagonists have potentially undesirable side effects, such as psychosis, especially in susceptible patients who have a history of psychiatric disorders. Nonetheless, in low doses, they have been used as a part of multimodal analgesia without side effects as aids to pain management [32]. Table 2 highlights this medication for orthopedic surgeries.

Table 2.

Acetaminophen, nonselective and selective NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, and NMDA receptor antagonists [25,33].

Table 2.

Acetaminophen, nonselective and selective NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, and NMDA receptor antagonists [25,33].

| Drug Class | Dose | Analgesic Duration | Metabolism | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Para-aminophenol Derivative | ||||

| Acetaminophen | 650–1000 mg IV | 4–6 h |

|

|

| Nonselective NSAIDs | ||||

| Ketorolac | 15–30 mg IV | 4–6 h |

|

|

| Ibuprofen | 400–800 mg IV | 4–6 h |

|

|

| Selective COX-2 Inhibitor | ||||

| Parecoxib | 20–40 mg IV | 6–12 h (IV) |

|

|

| N-methyl D-asparate (NMDA) Receptor Antagonist | ||||

| Ketamine | 0.5–1 mg/kg/h IV | 30–60 min IV |

|

|

5.5. Anticonvulsants (Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Analogues)

Gabapentin and pregabalin are GABA analogues that can be administered orally. They can be used before and after surgical procedures and have been shown to decrease the requirement for narcotic pain medications. The disadvantages of GABA analogues are their adverse effects, including sedation, visual disturbances, dizziness, and headache [34]. Table 3 highlights this class of medications for orthopedic surgeries.

Table 3.

Anticonvulsants [25,35].

5.6. Beta-Blockers

Use of beta-blockers, such as short-acting esmolol, intraoperatively not only blunts the cardiovascular response to surgical stimulus, such as tachycardia and hypertension, resulting in the decreased incidence of adverse cardiac events, but also decreases analgesic requirements postoperatively due to its anti-nociceptive effect [36]. Table 4 highlights this class of medications for orthopedic surgeries.

5.7. Alpha-2 Agonists

Clonidine and Dexmedetomidine are systemic alpha-2 agonists that can decrease postoperative opioid consumption, pain intensity, and opioid-related side effects (i.e., nausea). These medications are often added to an opioid-based regimen [37]. These medications can be administered at various times and via several different routes of administration. Clonidine can be administered orally, intravenously, and transdermally as well. Dexmedetomidine is usually given as an intravenous infusion started prior to wound closure. Table 4 highlights this class of medications for orthopedic surgeries.

Table 4.

Beta adrenergic receptor blockers, alpha 2 adrenergic receptor agonists [25,38].

Table 4.

Beta adrenergic receptor blockers, alpha 2 adrenergic receptor agonists [25,38].

| Drug Class | Dose | Duration of Hemodynamic Effect | Metabolism | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta Adrenergic Receptor Blockers | ||||

| Atenolol | 25–50 mg PO | 12–24 h (PO) |

|

|

| Metoprolol | 100 mg PO 2.5–5 mg IV | 3–6 h (PO)3–4 h (IV) |

|

|

| Esmolol | 0.5–1 mg/kg (IV) | 10–30 min (IV) |

|

|

| Alpha-2 Adrenergic Receptor Agonists | ||||

| Clonidine | 0.1 mg PO | 4–6 h |

|

|

| Dexmedeto-midine | 1 mcg/kg IV over 10 min with 0.2–0.7 mcg/kg/hr continuous IV | 2–3 h (IV) |

|

|

5.8. Capsaicin (Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Receptor 1 (TRPV1) Agonist)

Capsaicin selectively stimulates unmyelinated C-fiber afferent neurons, causing the continued release and subsequent depletion of substance P, which ultimately decreases C-fiber activation [39]. It must be instilled at the surgical site at the time of application [40]. Table 5 highlights this class of medications for orthopedic surgeries.

Table 5.

TRPV1 receptor agonist [41].

5.9. Lidocaine Infusion

Lidocaine was initially used in the 1940s to treat neuropathic pain in patients with burns. It acts by modifying the expression of sodium channels. An intravenous infusion of lidocaine utilizes its anesthetic properties by reducing circulatory inflammatory cytokines, reducing secondary hyperalgesia and central sensitization [42]. Due to its mechanism of action, lidocaine has an increased risk of cardiac and neurological side effects. Table 6 highlights this class of medications for orthopedic surgeries.

Table 6.

Local anesthetics [42,43].

5.10. Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids decrease post-operative pain and post-operative nausea and vomiting. They exert their analgesic effect via several mechanisms; they have anti-nociceptive effects at the spinal level, prevent the production of cytokines involved in inflammatory pain, and inhibit the production of inflammatory prostaglandins and leukotrienes by preventing arachidonic acid production [16,44]. In high doses, they have been known to cause hyperglycemia, which is not significant at the usual doses used. For orthopedic surgeries involving joints, spinal facet joints are injected with a 1:1 ratio of corticosteroid to anesthetic. Extremity joints, such as the elbow or wrist, require 2–4 ccs of solution, while larger joints, such as the hip, knee, or sacroiliac, require 4–8 ccs of solution, containing the corticosteroid and anesthetic [44]. Table 7 highlights this class of medications for orthopedic surgeries.

Table 7.

Glucocorticoids and Magnesium [44,45,46].

5.11. Magnesium

Intravenous magnesium has been shown to have an opioid-sparing effect, with a reduction in pain scores. It is administered as a bolus dose of 30–50 mg/kg IV, followed by 6–20 mg/kg/hr infusion for 4 h. Extracellular magnesium blocks the NMDA receptor in a voltage-dependent manner [45], and thus, can prevent the establishment of central sensitization. Table 7 highlights this class of medications for orthopedic surgeries.

6. Conclusions

Pain is a subjective sensation and is difficult to assess. A variety of pain assessment tools such as the VAS (verbal analog score), the McGill Pain Questionnaire, and a brief pain inventory can be used. The Wong–Baker facial grimace scale is useful when patients are unable to communicate their pain intensity. The majority of postoperative pain is nociceptive with a small neuropathic component. Pain management strategies should address both types of pain. In the words of Dr. John Bonica, the father of pain medicine, “Pain is what a patient says it is.” Effective pain control requires constant reassessment with individualized strategies.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hsu, J.R.; Mir, H.; Wally, M.K.; Seymour, R.B. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pain Management in Acute Musculoskeletal Injury. J. Orthop. Trauma 2019, 33, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, S.A.; Chelminski, P.R.; Ives, T.J.; Ranapurwala, S.I. Management of Pain in the United States—A Brief History and Implications for the Opioid Epidemic. Health Serv. Insights 2018, 11, 117863291881944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudd, R.A.; Seth, P.; David, F.; Scholl, L. Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths—United States, 2010–2015. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016, 65, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braden, J.B.; Fan, M.-Y.; Edlund, M.J.; Martin, B.C.; DeVries, A.; Sullivan, M.D. Trends in Use of Opioids by Noncancer Pain Type 2000–2005 among Arkansas Medicaid and HealthCore Enrollees: Results from the TROUP Study. J. Pain 2008, 9, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.C.; Fan, M.-Y.; Edlund, M.J.; DeVries, A.; Braden, J.B.; Sullivan, M.D. Long-Term Chronic Opioid Therapy Discontinuation Rates from the TROUP Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korff, M.V.; Saunders, K.; Thomas Ray, G.; Boudreau, D.; Campbell, C.; Merrill, J.; Sullivan, M.D.; Rutter, C.M.; Silverberg, M.J.; Banta-Green, C.; et al. De Facto Long-Term Opioid Therapy for Noncancer Pain. Clin. J. Pain 2008, 24, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, F.J.; Mogil, J.S.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; et al. The Revised International Association for the Study of Pain Definition of Pain: Concepts, Challenges, and Compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, A.V.; Blum, Y.C.; Shekhar, L.; Ranawat, A.S.; Ranawat, C.S. Multimodal Pain Management after Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty at the Ranawat Orthopaedic Center. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2009, 467, 1418–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.J.; Currier, B.L. Analgesic Pharmacology: I. Neurophysiology. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2004, 12, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H.B.; Shintani, E.Y. Results of a Multimodal Analgesic Trial Involving Patients with Total Hip or Total Knee Arthroplasty. Am. J. Orthop. 2004, 33, 85–92, discussion 92. [Google Scholar]

- Dafny, N. Pain Principles (Section 2, Chapter 6) Neuroscience Online: An Electronic Textbook for the NNeurosciences|Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy-The University of Texas Medical School at Houston. Available online: https://nba.uth.tmc.edu/neuroscience/m/s2/chapter06.html (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Levine, J.D.; Reichling, D.B. Peripheral mechanisms of inflammatory pain. In Textbook of Pain, 4th ed.; Wall, P.D., Melzack, R., Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, Scotland, 1999; pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ghori, M.K.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Sinatra, R.S. Pathophysiology of Acute Pain. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/acute-pain-management/pathophysiology-of-acute-pain/1AB5E239B3A33CE9E9F78A28E2756EA6 (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Graefe, S.B.; Mohiuddin, S.S. Biochemistry, Substance P. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32119470/ (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Kehlet, H.; Dahl, J.B. The Value of Multimodal Or Balanced Analgesia In Postoperative Pain Treatment. Anesth. Analg. 1993, 77, 1048–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogatzki-Zahn, E.M.; Zahn, P.K. From Preemptive to Preventive Analgesia. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2006, 19, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Xiao, L. Postoperative Pain Management in Total Knee Arthroplasty. Orthop. Surg. 2019, 11, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crile, G. The Kinetic Theory of Shock and Its Prevention through Anoci-Association (Shockless Operation). Lancet 1913, 182, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, C.J. Evidence for a Central Component of Post-Injury Pain Hypersensitivity. Nature 1983, 306, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, G.P.; Machi, A. Surgical Site Infiltration: A Neuroanatomical Approach. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2019, 33, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraca, R.J.; Sheldon, D.G.; Thirlby, R.C. The Role of Epidural Anesthesia and Analgesia in Surgical Practice. Ann. Surg. 2003, 238, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna Prasad, G.V.; Khanna, S.; Jaishree, S.V. Review of Adjuvants to Local Anesthetics in Peripheral Nerve Blocks: Current and Future Trends. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2020, 14, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, D. Palliative Care Clinical PharmacistMedStar Washington Hospital CenterWashington, Pearls and Pitfalls of Patient-Controlled Analgesia. Available online: https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/pearls-and-pitfalls-of-patientcontrolled-analgesia (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Portenoy, R.K.; Mehta, Z.; Ahmed, E. Cancer Pain Management with Opioids: Optimizing Analgesia. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/cancer-pain-management-with-opioids-optimizing-analgesia?search=route+of+administration+pain+control&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1 (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Mariano, E.R. Management of Acute Perioperative Pain. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-acute-perioperative-pain (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Tan, H.S.; Habib, A.S. Oliceridine: A Novel Drug for the Management of Moderate to Severe Acute Pain–A Review of Current Evidence. J. Pain Res. 2021, 14, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.; St John-Green, C.; Walker, S.M. Opioid-Sparing Effects of Perioperative Paracetamol and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) in Children. Pediatr. Anesth. 2013, 23, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobby, T.F.; Crighton, I.M.; Kyriakides, K.; Hobbs, G.J. Rectal Paracetamol Has a Significant Morphine-Sparing Effect after Hysterectomy. Br. J. Anaesth. 1999, 83, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zukowski, M.; Kotfis, K. Safety of Metamizole and Paracetamol for Acute Pain Treatment. Anestezjol. Intensywna Ter. 2009, 41, 170–175. [Google Scholar]

- Maund, E.; McDaid, C.; Rice, S.; Wright, K.; Jenkins, B.; Woolacott, N. Paracetamol and Selective and Non-Selective Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs for the Reduction in Morphine-Related Side-Effects after Major Surgery: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2011, 106, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fosbøl, E.L.; Folke, F.; Jacobsen, S.; Rasmussen, J.N.; Sørensen, R.; Schramm, T.K.; Andersen, S.S.; Rasmussen, S.; Poulsen, H.E.; Køber, L.; et al. Cause-Specific Cardiovascular Risk Associated with Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs among Healthy Individuals. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2010, 3, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remérand, F.; Le Tendre, C.; Baud, A.; Couvret, C.; Pourrat, X.; Favard, L.; Laffon, M.; Fusciardi, J. The Early and Delayed Analgesic Effects of Ketamine after Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled, Double-Blind Study. Anesth. Analg. 2009, 109, 1963–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, D.P.; Chen, L.; Mao, J. Intravenous Ketamine Infusions for Neuropathic Pain Management. Anesth. Analg. 2017, 124, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ho, K.-Y.; Wang, Y. Efficacy of Pregabalin in Acute Postoperative Pain: A Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Anaesth. 2011, 106, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palliative Drugs. Pregabalin-palliativedrugs.com. Available online: https://www.palliativedrugs.com/download/pregabalin140105aw.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Chia, Y.Y.; Chan, M.H.; Ko, N.H.; Liu, K. Role of β-Blockade in Anaesthesia and Postoperative Pain Management after Hysterectomy. Br. J. Anaesth. 2004, 93, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaudszun, G.; Lysakowski, C.; Elia, N.; Tramer, M.R. Effect of Perioperative Systemic Alpha-2 Agonists on Postoperative Morphine Consumption and Pain Intensity: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Heslington, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Royster, R.L. Perioperative beta-blockade II: Practical clinical application. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Available online: https://www.apsf.org/article/perioperative-beta-blockade-ii-practical-clinical-application/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Young, A.; Buvanendran, A. Recent Advances in Multimodal Analgesia. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2012, 30, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartrick, C.T.; Pestano, C.; Carlson, N.; Hartrick, S. Capsaicin Instillation for Postoperative Pain Following Total Knee Arthroplasty. Clin. Drug Investig. 2011, 31, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.; Bley, K. Topical Capsaicin for Pain Management: Therapeutic Potential and Mechanisms of Action of the New High-Concentration Capsaicin 8% Patch. Br. J. Anaesth. 2011, 107, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeng, C.L. Overview of peripheral nerve blocks. UpToDate. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-peripheral-nerve-blocks?sectionName=Local+anesthetics&search=local+anesthesia+regional&topicRef=14929&anchor=H14&source=see_link#H14 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Pujari, V.; Siddaiah, J.; Madalu, A.; Bevinaguddaiah, Y.; Parate, L. A Comparative Study on the Effect of Addition of Intrathecal Buprenorphine to 2-Chloroprocaine Spinal Anesthesia in Short Duration Surgeries. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 35, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennard, T. Corticosteroid Use in Pain Management. Pract. Pain Manag. 2000. Available online: https://www.practicalpainmanagement.com/corticosteroid-use-pain-management (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Mayer, M.L.; Westbrook, G.L.; Guthrie, P.B. Voltage-Dependent Block by Mg2+ of NMDA Responses in Spinal Cord Neurones. Nature 1984, 309, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasbjerg, K.S.; Hägi-Pedersen, D.; Lunn, T.H.; Laursen, C.C.; Holmqvist, M.; Vinstrup, L.Ø.; Ammitzboell, M.; Jakobsen, K.; Jensen, M.S.; Pallesen, M.J.; et al. Effect of Dexamethasone as an Analgesic Adjuvant to Multimodal Pain Treatment after Total Knee Arthroplasty: Randomised Clinical Trial. BMJ 2022, 376, e067325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).