Abstract

Background: Proprioception is an important part of the somatosensory system involved in human motion control, which is fundamental for activities of daily living, exercise, and sport-specific gestures. When total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is performed, the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) can be retained, replaced, or discarded. The PCL seems to be responsible for maintaining the integrity of the joint position sense (JPS) and joint kinesthesia. The aim of this review was to assess the effect of PCL on knee joint proprioception in total knee replacement. Methods: This systematic review was conducted within five electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane, and PEDro with no data limit from inception to May 2021. Results: In total 10 publications were evaluated. The analysis was divided by proprioception assessment method: direct assessment (JPS, kinesthesia) and indirect assessment (balance). Conclusions: The current evidence suggest that the retention of the PCL does not substantially improve the joint proprioception after TKA. Due to the high heterogeneity of the studies in terms of design, proprioception outcomes, evaluation methods, further studies are needed to confirm the conclusions. In addition, future research should focus on the possible correlation between joint proprioception and walking function.

1. Introduction

Proprioception is an important part of the somatosensory system that can be defined, in relation to the joints, as “the perception of joint movement as well as the position of the body segments in space” and the “perceptions of relative flexions and extensions of our limbs” [1]. In orthopedic surgery the term proprioception is generally defined as the ability of the individual to perceive the position of a joint in space [2]. A unanimously agreed definition of proprioception has not yet been established although we can summarize it as the body’s own sense of position and motion, which includes body segment static position, displacement, velocity, acceleration, and muscular sense of force [3,4]. Proprioception is a fundamental pillar of human motion control, which is essential for activities of daily living, exercise, and sports specific gesture [5]. Indeed, joint proprioception guarantees reflex responses that protect the joint from excessive and potentially harmful movements, maintenance of joint stability during static positions and coordination of joint movements [6,7].

Various techniques are reported in the literature to evaluate joint proprioception [5,8]. The most relevant are [5]:

- Threshold to detection of passive motion (TTDPM): the subject is asked to indicate when he perceives the joint movement that is passively performed by a mobilization system starting from a stationary position.

- Joint position reproduction (JPR), or active joint position detection (AJPD): the subject is required to actively reproduce an established joint angle. This test allows calculation of the accuracy of the replication of the joint angle.

- Active movement extent discrimination assessment (AMEDA): the subject is asked to perform and recognize predetermined knee flexion positions.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) represents the definitive treatment in knee osteoarthritis (OA) [9]. The number of TKAs in the United States is expected to increase 143% by 2050 [10]. Furthermore, a recent study estimated an increase up to 91% and 155%, respectively, for primary and revision TKAs by 2030 in Korea [11]. When TKA is performed, the surgeon can retain or sacrifice structures such as the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) [12]. One of the goals of the orthopedic surgeon when performing a TKA is to reproduce natural knee movements while maintaining stability in the whole range of movement [13,14]. The PCL, through different types of mechanoreceptors, seems to be responsible for maintaining the integrity of the joint position sense and joint kinesthesia [15,16]. Different proprioceptive receptors (e.g., muscle spindles, Golgi tendon organs, Golgi receptors, Pacinian corpuscles, Ruffini endings and bare nerve endings) are present in the structures of the knee (e.g., muscles, tendons, ligaments, menisci, and capsule), sending afferent signals and are responsible for joint proprioception of the knee [6].

Based on a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis [12] investigating the difference between either retention or sacrifice of the PCL on major outcomes such as range of motion, knee pain, implant survival rate, validated clinical and functional questionnaire scores (i.e., Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), patient satisfaction, complications, re-operations other than revision surgery (e.g., manipulation because of impaired knee function) no clear and relevant differences were identified. However, the effects on proprioception have not been investigated.

More recent systematic reviews and meta-analysis by Di Laura Frattura et al. [7] and by Bragonzoni et al. [17] investigated the effects of TKAs on joint proprioception with conflicting results. In fact, although Di Laura Frattura et al. [7] found that proprioception in OA patients undergoing TKA improves but remains impaired after surgery, Bragonzoni et al. [17] found no consensus in the literature about the improvement or worsening in proprioception before and after TKA. However, these reviews did not focus on the effect of PCL retaining or sacrifice on proprioception.

The purpose of this systematic review is to understand whether the proprioception of subjects who have undergone TKA are influenced by the sacrifice (PS design) or retention (CR design) of the PCL. In the present paper we separately analyzed the studies that directly evaluate knee proprioception (as described above) and those that assessed proprioception indirectly through static and dynamic balance evaluation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Search

An online systematic search was performed on 26 May 2021, using the following electronic databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science (WOS), Cochrane, and PEDro. No data limit was used. The Population Intervention Comparison and Outcome (PICO) model was adopted to conduct an evidence-based practice literature search [18] (Table 1). The search strategy used a combination of medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and free-text terms adjusted according to each database specification. An additional manual search and a reference lists examination was performed. The search strategy is shown in Appendix A. The review protocol has been registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42021259569).

Table 1.

PICO model.

2.2. Data Extraction

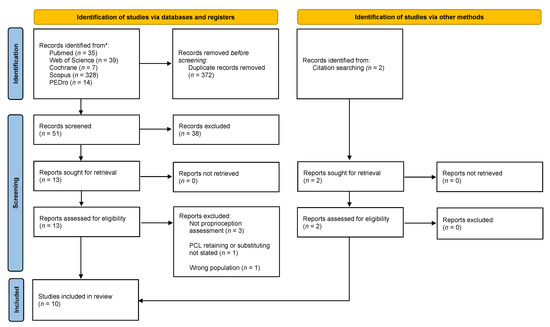

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were used (Figure 1) [19]. Only English written original full-text articles, published from inception to May 2021 about the assessment of proprioception in adult patients with CR or PS TKA were included in this review. Exclusion criteria were non-clinical studies, abstract, editorial, review article, book chapter, case report, not assessed proprioception in the knee joint, focused on partial knee replacement.

Figure 1.

Selection flow diagram according to the PRISMA 2020 statement. From: Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71, doi:10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 13 May 2021).

Duplicated references were manually identified and excluded, then two reviewers (MB, FS) independently screened title and abstracts to identify eligible articles. At the end of this phase the two reviewers met to discuss the inclusion of all articles that were selected by a single reviewer.

Subsequently, the full texts of the selected articles were screened by both reviewers to verify if they met the inclusion criteria and the presence of any exclusion criteria. After the selection of eligible studies, data were extracted, including the name of the first author, year of publication, study design and objective, characteristics of the participants, (e.g., mean age, male prevalence), the type of equipment used to proprioceptive evaluation, proprioceptive outcome, evaluation protocol and summary of results. Any discrepancies that occurred in any of the phases described were discussed with a third reviewer (SM).

2.3. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of included studies was evaluated by two independent reviewers (MB, FS), a third reviewer (SM) was consulted if discrepancies were not resolved by discussion. The tools for the methodological quality assessment of the included studies were chosen according to Ma et al. [20]. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were assessed using the version two of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) [21]; non-RCT studies were assessed using the MINORS (Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies) checklist [22], a tool specifically developed to assess the quality of nonrandomized surgical studies. It includes 12 items; the last 4 are specific for comparative studies. The score for the items varies from 0 to 2 (0, not reported; 1, reported but poorly reported or inadequate; 2, reported but well reported and adequate). The maximum global score is set to 16 for a noncomparative study and 24 for a comparative study.

Since a meta-analysis could not be performed due to the lack of homogeneity of proprioception assessment, a best evidence synthesis was performed according to van Tulder et al. [23]. The evidence level was then stated through the following rules: strong evidence if 2 or more studies with low risk of bias and generally consistent findings in all studies (≥75% reporting consistent findings) were found; moderate evidence if 1 study with low risk of bias and 2 or more moderate/high risk of bias studies or with 2 or more moderate/high risk of bias and generally consistent findings in all studies (≥75%) were found; limited evidence if 1 or more studies with moderate/high bias risk or 1 low bias risk study and generally consistent findings (≥75%) were found, conflicting evidence with conflicting findings (<75% of the studies reporting consistent findings).

3. Results

3.1. Systematic Literature Review Synthesis

A total of 423 articles were identified through a systematic review of the literature (Figure 1). After removing 372 duplicates, a total of 51 titles and abstracts studied were examined and 38 studies were excluded because they did not meet our inclusions criteria. A total of 13 studies plus 2 studies retrieved through citation searching were assessed for eligibility. After full-text reading, 10 studies [16,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] were included in the qualitative analysis of this systematic review. Non-randomized studies [16,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] showed an average moderate risk of bias assessed through the MINOR scale (Table 2), the RCT [25] showed an overall low risk of bias assessed through Rob2.

Table 2.

MINORS score of non-randomized studies.

The study population consisted of 383 patients, including 262 females and 121 males; age ranged from 26 to 91 years. The analysis of the studies showed heterogeneity in the method of assessing proprioception: two studies [24,29] assessed proprioception through an indirect method (e.g., the ability to maintain balance on both or a single leg), six studies [16,26,27,28,30,31] used a direct method of assessing proprioception (e.g., JPS, TTDPM), one study [25] used both direct and indirect methods. Details of the included studies are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Details of included studies.

3.2. Indirect Proprioception Assessment

Four papers [24,25,29,32] analyzed the effects on proprioception of CR versus PS TKA using an indirect assessment technique. Two studies [25,29] used the Biodex Balance System®, two studies [24,32] used the Balance Master System®. The postural stability tests were performed in different ways: two studies [24,29] analyzed the ability to maintain balance both in a bipodal stance position and on a single leg, and two studies [25,32] used assessed the ability to balance only in the bipodal stance position.

The comparison with the unaffected contralateral leg was evaluated in two studies [24,29] and showed that about 5 months after surgery, regardless of the type of TKA design, proprioception is non significantly different to that of the contralateral (moderate evidence). The single leg test showed no significant differences between the CR and PS group. The balance test on both legs did not show significant differences between CR and PS in any of the studies analyzed (moderate evidence).

Only Swanik et al. [25] compared the effects with respect to preoperative assessment, regardless of the type of intervention reported a significant (p < 0.05) improvement in balance (limited evidence).

3.3. Direct Proprioception Measurement

Direct evaluation of joint proprioception was performed using JPS and joint kinesthesia assessments through TTDPM. A total of four studies [16,27,28,30] assessed the JPS, two studies [26,31] assessed the TTDPM, and one study [25] assessed both tests.

The JPS was evaluated using different methods: one study [16] evaluated the JPS by asking the subject to reproduce on a hand-held model of the leg the degree of flexion of the knee passively positioned by a machine. Three studies [27,28,30] evaluated the JPS by means of the joint position reproduction (JPR) test, one study [28] performed the test with the patient in standing position, while the other two studies [27,30] carried out the test with the patient in a sitting position with the legs hanging freely; in one study [30] the leg was passively positioned by the examiner at the target position, in two studies [27,28] the patient was asked to actively reach the target position and then reproduce it. Finally, Swanik et al. [25] assessed the JPS by asking the subject to report when he felt that the knee, passively rotated at a constant speed, had reached the previously reported target position. The studies also reported heterogeneity in the tools used to measure JPS; two studies [16,25] used a non-commercial proprioceptive testing device which passively rotated the knee, one study [30] used a motion capture system (Kinemetrix, Orthodata, Lüdenscheid, Germany) and two studies [27,28] used an electrogoniometer.

The comparison with the contralateral non-operated leg was evaluated in two studies [27,30] which showed no significant differences between the two legs in the JPR test (moderate evidence).

Four studies [16,25,27,28] made a direct comparison between the CR and PS group, while one study [30] compared only the type of CR prosthesis with a healthy control group. The analysis of the studies that directly compared the CR and PS groups showed conflicting results, indeed Swanik et al. [25] found that the PS group was significantly more accurate in one JPS test (when moving into extension form 45° of knee joint flexion) than the CR group, Warren et al. [16] on the contrary found a significantly better result in the CR group, while Lattanzio et al. [27] and Ishii et al. [28] found no significant differences between the two groups (conflicting findings).

The ability to detect joint motion through TTDPM was assessed using a non-commercial device which passively rotated the knee. The comparison between the operated leg and the contralateral non-operated leg was assessed in two studies [26,31], which did not show significant differences for both CR and PS group in the ability to detect joint movement at an average follow-up greater than 23 months after surgery (moderate evidence). Analysis of the results between CR and PS groups did not show significant differences in any of the three studies [25,26,31] (moderate evidence).

4. Discussion

This paper reviewed published studies that analyzed the effects of prosthetic design (cruciate-retaining or cruciate-scarifying) on proprioception, to provide an overview of how preserving or scarifying the PCL would influence changes in knee proprioception in patients with OA underwent to TKA. Only 10 studies out of 384 fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Among these four papers assessed proprioception through indirect method, while six papers proposed a direct method of assessment.

Indirect methods were mainly based on balance assessment, the balance according to Baumann et al. [33] and Bragonzoni et al. [17] can really be considered as an indirect measure of proprioception, although it is necessary to underline that, as also reported by Gotz et al. [29], the use of only the two-leg stance position is controversial, since the results could be influenced by both the operated and the contralateral knee. Only Swanik et al. [25] performed a pre-post-surgery evaluation with an indirect method, showing no substantial proprioceptive advantages in preserving PCL. Gotz. et al. [29] and Vandekerckhov et al. [24] showed an improvement of proprioception regardless of the type of prosthesis, both in comparison to the healthy contralateral leg and in the bipodalic test, concluding that the PCL does not seem to play a decisive role in balance control.

The results of studies that used direct methods of joint proprioception and kinesthesia assessment are conflicting. However, a specific comparison between the studies was not possible due to the high heterogeneity in terms of study design, evaluation methods, parameters evaluated and length of follow up.

It has been suggested that the sensory denervation of the PCL begins even before surgery in the osteoarthritic knee [25]. Furthermore, the PCL is not the only structure involved in maintaining knee proprioception. The proprioception of the knee is guaranteed by the integrity of multiple anatomical structures (i.e., muscles, tendons, ligaments, capsule) and by the integration of the different afferent signals coming from the different proprioceptive receptors [6] as well as by signals coming from outside the joint itself (e.g., vestibular and visual system). Therefore, the improvements that are observed are more likely due to be related to the reduction in pain, swelling, deformity, and to the reduced physical activity already described as a possible cause for impaired proprioceptive accuracy in the non-symptomatic knees [6,34] rather than a PCL repopulation by mechanoreceptors [25,35,36,37]. Indeed, regardless of the intervention on the PCL, TKA improves joint space, soft tissue tension and by reducing pain and inflammation allowing a return to daily physical activity that could contribute to knee proprioceptive improvements [2,17]. In support of this hypothesis, it should be emphasized that the muscle spindles, located within muscle fibers, seem to be the most important proprioceptive receptors of the knee particularly involved at mid-range of knee angle [34,38], therefore an improvement of the periarticular muscles structures after TKA and rehabilitation could also be responsible for the improvement of joint proprioception regardless of the surgical involvement of the PCL.

Another aspect that deserves further studies is to understand whether prosthetic design plays a role in proprioceptive recovery after TKA. Indeed, when the PCL is sacrificed, several TKAs design are available to compensate for the absence of the PCL. The PS design is most commonly used and provides a cam post mechanism to cover the functions of the PCL, others design use deep dish inserts with a high anterior rim as a brake against posterior subluxation of the tibia [12]. When the PCL is retained, the use of prosthetics designed with high geometric conformity to the medial articular surface has been found to increase the postoperative maximum flexion angle and ROM [39]. These aspects could influence the results in terms of proprioception and could guide the surgeon in choosing the type of surgery, in fact to date there is still no consensus on when to perform a PCL retaining or sacrifice; Lombardi et al. [13] proposed a decision algorithm for the retention or sacrifice of the PCL based on the patient’s clinical history, clinical evaluation and intraoperative findings. However, the decision to perform a PCL retention or sacrifice is still linked to the state of the ligament, the presence of knee deformity, the type of implant used or the surgeon’s personal preference [12]. In fact, to date, there is still no evidence in favor of PCL retaining or sacrifice as also reported by a recent meta-analysis by Migliorini et al. [40].

Some limitations of the studies included in this review need to be addressed: only one study [25] was an RCT with good methodological quality, all the other studies were found to be lacking from a methodological point of view; most of the studies are retrospective observational studies that do not allow a pure comparison between two homogeneous populations nor a pre–post-surgery comparison; the sample size in several studies was found to be small and inadequately calculated prior to the start of the study; most of the studies did not included a healthy control group and finally the studies analyze proprioception with different methodologies not allowing a comparison between them. Another limitation of this systematic review is the inclusion of only English articles which could lead to an exclusion of relevant studies related to this topic.

5. Conclusions

This review study aimed to investigate whether TKAs with PCL retaining or sacrificing could influence proprioception in patients with OA. The heterogeneity of the studies in terms of methodological quality, evaluation instrumentation, and outcome measures hampered the execution of a quantitative analysis through a meta-analysis, however a conclusion can be drawn: this systematic review revealed that patients with knee OA undergoing TKA improves their knee proprioception, and this appears to be regardless of the PCL retention or sacrifice.

According to previous systematic reviews [12,17] we strongly suggest further studies in which trials should be set up to assess consistently the outcome parameters, at uniform time intervals, at least one year follow up should be included if balance assessment is used [17], to make easier future meta-analysis. Furthermore, given the current availability of rapid and valid gait analysis systems [41,42,43], the study of a possible correlation between joint proprioceptive deficits and clinical and functional alterations should be encouraged.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., S.S. and R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B., F.S. and S.C.; methodology, M.B., S.C., S.M. and F.B.; writing—review and editing, M.B., S.C., R.P. and S.S.; supervision, R.P., S.S. and F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Literature search (performed 26 May 2021).

Table A1.

Literature search (performed 26 May 2021).

| Database | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (“propriocept*”[All Fields] OR “Proprioception”[MeSH Terms]) AND (“total knee arthroplasty”[All Fields] OR “TKA”[All Fields] OR “TKR”[All Fields] OR “total knee replacement*”[All Fields] OR “arthroplasty, replacement, knee”[MeSH Terms]) AND (“PCL”[All Fields] OR “Posterior Cruciate Ligament”[All Fields] OR “Posterior Cruciate Ligament”[MeSH Terms]) |

| Cochrane | (Propriocept*) AND (“total knee arthroplasty” OR TKA OR TKR OR “total knee replacement*”) AND (PCL OR “posterior cruciate ligament”) |

| Scopus | ALL(propriocept*) AND (“total knee arthroplasty” OR tka OR tkr OR “total knee replacement*”) AND (pcl OR “posterior cruciate ligament”) |

| WOS | ALL = (Propriocept*) AND ALL = (“total knee arthroplasty” OR TKA OR TKR OR “total knee replacement*”) AND ALL = (PCL OR “posterior cruciate ligament”) |

| PEDro 1 | (Propriocept*) AND (“total knee arthroplasty”)(Propriocept*) AND (“total knee replacement”) |

1 The research on PEDro was conducted separately with the two strings and then the results were merged. The asterisk (*) is the truncation symbol used at the end of a word to search for all terms that begin with that basic word root.

References

- Riemann, B.L.; Lephart, S.M. The sensorimotor system, part I: The physiologic basis of functional joint stability. J. Athl. Train. 2002, 37, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wodowski, A.J.; Swigler, C.W.; Liu, H.; Nord, K.M.; Toy, P.C.; Mihalko, W.M. Proprioception and Knee Arthroplasty. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 47, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvist, M. Achilles Tendon Injuries in Athletes. Sports Med. 1994, 18, 173–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, M.; Veeger, D.; Janssen, T. Effect of Body Orientation on Proprioception during Active and Passive Motions. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009, 88, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Waddington, G.; Adams, R.; Anson, J.; Liu, Y. Assessing proprioception: A critical review of methods. J. Sport Health Sci. 2016, 5, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Knoop, J.; Steultjens, M.; van der Leeden, M.; van der Esch, M.; Thorstensson, C.; Roorda, L.; Lems, W.; Dekker, J. Proprioception in knee osteoarthritis: A narrative review. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2011, 19, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frattura, G.D.L.; Zaffagnini, S.; Filardo, G.; Romandini, I.; Fusco, A.; Candrian, C. Total Knee Arthroplasty in Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: Effects on Proprioception. A Systematic Review and Best Evidence Synthesis. J. Arthroplast. 2019, 34, 2815–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, S.; Immink, M.; Thewlis, D. Assessing Proprioception. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2015, 29, 933–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, D.J.; Hossain, F.S.; Patel, S.; Haddad, F.S. A Cohort Study Predicts Better Functional Outcomes and Equivalent Patient Satisfaction Following UKR Compared with TKR. HSS J. 2013, 9, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inacio, M.; Paxton, E.; Graves, S.; Namba, R.; Nemes, S. Projected increase in total knee arthroplasty in the United States—An alternative projection model. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2017, 25, 1797–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, T.W.; Kang, S.-B.; Chang, C.B.; Moon, S.-Y.; Lee, Y.-K.; Koo, K.-H. Current Trends and Projected Burden of Primary and Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty in Korea Between 2010 and 2030. J. Arthroplast. 2021, 36, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verra, W.C.; Boom, L.G.V.D.; Jacobs, W.; Clement, D.J.; Wymenga, A.; Nelissen, R. Retention versus sacrifice of the posterior cruciate ligament in total knee arthroplasty for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD004803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lombardi, A.V.; Mallory, T.H.; Fada, R.A.; Hartman, J.F.; Capps, S.G.; Kefauver, C.A.; Adams, J. An Algorithm for the Posterior Cruciate Ligament in Total Knee Arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2001, 392, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalko, W.; Krackow, K.A. Posterior Cruciate Ligament Effects on the Flexion Space in Total Knee Arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1999, 360, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelissen, R. Retain or sacrifice the posterior cruciate ligament in total knee arthroplasty? A histopathological study of the cruciate ligament in osteoarthritic and rheumatoid disease. J. Clin. Pathol. 2001, 54, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Warren, P.J.; Olanlokun, T.K.; Cobb, A.G.; Bentley, G. Proprioception after knee arthroplasty. The influence of prosthetic design. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1993, 182–187. [Google Scholar]

- Bragonzoni, L.; Rovini, E.; Barone, G.; Cavallo, F.; Zaffagnini, S.; Benedetti, M.G. How proprioception changes before and after total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. Gait Posture 2019, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D. A Review of the PubMed PICO Tool: Using Evidence-Based Practice in Health Education. Health Promot. Pract. 2019, 21, 496–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.-L.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.-H.; Huang, D.; Weng, H.; Zeng, X.-T. Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS ): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tulder, M.; Furlan, A.; Bombardier, C.; Bouter, L. Updated Method Guidelines for Systematic Reviews in the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine 2003, 28, 1290–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandekerckhove, P.-J.T.K.; Parys, R.; Tampere, T.; Linden, P.; Daelen, L.V.D.; Verdonk, P.C. Does cruciate retention primary total knee arthroplasty affect proprioception, strength and clinical outcome? Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2015, 23, 1644–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanik, C.B.; Lephart, S.M.; Rubash, H.E. Proprioception, Kinesthesia, and Balance After Total Knee Arthroplasty with Cruciate-Retaining and Posterior Stabilized Prostheses. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. Vol. 2004, 86, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, S.; Lephart, S.; Rubash, H.; Borsa, P.; Barrack, R.L. Proprioception following total knee arthroplasty with and without the posterior cruciate ligament. J. Arthroplast. 1996, 11, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanzio, P.-J.; Chess, D.G.; MacDermid, J.C. Effect of the posterior cruciate ligament in knee-joint proprioception in total knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 1998, 13, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Y.; Terajima, K.; Terashima, S.; Bechtold, J.E.; Laskin, R.S. Comparison of joint position sense after total knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 1997, 12, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, J.; Beckmann, J.; Sperrer, I.; Baier, C.; Dullien, S.; Grifka, J.; Koeck, F. Retrospective comparative study shows no significant difference in postural stability between cruciate-retaining (CR) and cruciate-substituting (PS) total knee implant systems. Int. Orthop. 2016, 40, 1441–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, S.; Thorwesten, L.; Niewerth, S. Proprioceptive function in knees with and without total knee arthroplasy1. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1999, 78, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cash, R.M.; Gonzalez, M.H.; Garst, J.; Barmada, R.; Stern, S.H. Proprioception after arthroplasty: Role of the posterior cruciate ligament. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1996, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascuas, I.; Tejero, M.; Monleón, S.; Boza, R.; Muniesa, J.M.; Belmonte, R. Balance 1 Year After TKA: Correlation With Clinical Variables. Orthopedics 2013, 36, e6–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baumann, F.; Bahadin, Ö.; Krutsch, W.; Zellner, J.; Nerlich, M.; Angele, P.; Tibesku, C.O. Proprioception after bicruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty is comparable to unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2016, 25, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Pai, Y.-C.; Holtkamp, K.; Rymer, W.Z. Is knee joint proprioception worse in the arthritic knee versus the unaffected knee in unilateral knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40, 1518–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.; Andersson, G.; Fridén, T. Knee joint proprioception in ACL-deficient knees is related to cartilage injury, laxity and ageA retrospective study of 54 patients. Acta Orthop. Scand. 2004, 75, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barrack, R.L.; Skinner, H.; Brunet, M.E.; Cook, S.D. Joint Laxity and Proprioception in the Knee. Physician Sportsmed. 1983, 11, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koralewicz, L.M.; Engh, G.A. Comparison of Proprioception in Arthritic and Age-Matched Normal Knees. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. Vol. 2000, 82, 1582–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pai, Y.-C.; Rymer, W.Z.; Chang, R.W.; Sharma, L. Effect of age and osteoarthritis on knee proprioception. Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40, 2260–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujito, T.; Tomita, T.; Yamazaki, T.; Oda, K.; Yoshikawa, H.; Sugamoto, K. Influence of Posterior Tibial Slope on Kinematics After Cruciate-Retaining Total Knee Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 3778–3782.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Eschweiler, J.; Tingart, M.; Rath, B. Posterior-stabilized versus cruciate-retained implants for total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis of clinical trials. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2019, 29, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, M.; Gallotta, E.; Morrone, M.; Maselli, M.; Santacaterina, F.; Toglia, R.; Foti, C.; Sterzi, S.; Bressi, F.; Miccinilli, S. Concurrent validity and inter trial reliability of a single inertial measurement unit for spatial-temporal gait parameter analysis in patients with recent total hip or total knee arthroplasty. Gait Posture 2020, 76, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boekesteijn, R.J.; Smolders, J.M.H.; Busch, V.J.J.F.; Geurts, A.C.H.; Smulders, K. Independent and sensitive gait parameters for objective evaluation in knee and hip osteoarthritis using wearable sensors. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, K.E.; Wittwer, J.; Feller, J.A. Validity of the GAITRite® walkway system for the measurement of averaged and individual step parameters of gait. Gait Posture 2005, 22, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).