Abstract

Background: Cervical cancer poses a threat to the health of women globally. Adolescent girls are the primary target population for HPV vaccination, and guardians’ attitude towards the HPV vaccine plays a significant role in determining the vaccination status among adolescent girls. Objectives: This study aimed to explore the factors influencing guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance for their girls and provide clues for the development of health intervention strategies. Methods: Combining the health belief model as a theoretical framework, a questionnaire-based survey was conducted. A total of 2157 adolescent girls and their guardians were recruited. The multivariable logistic model was applied to explore associated factors. Results: The guardians had a high HPV vaccine acceptance rate (86.7%) for their girls, and they demonstrated a relatively good level of awareness regarding HPV and HPV vaccines. Factors influencing guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance for girls included guardians’ education background (OR = 0.57, 95%CI = 0.37–0.87), family income (OR = 1.94, 95%CI = 1.14–3.32), risk of HPV infection (OR = 3.15, 95%CI = 1.40–7.10) or importance of the HPV vaccine for their girls (OR = 6.70, 95%CI = 1.61–27.83), vaccination status surrounding them (OR = 2.03, 95%CI = 1.41–2.92), awareness of negative information about HPV vaccines (OR = 0.59, 95%CI = 0.43–0.82), and recommendations from medical staff (OR = 2.32, 95%CI = 1.65–3.25). Also, guardians preferred to get digital information on vaccines via government or CDC platforms, WeChat platforms, and medical knowledge platforms. Conclusions: Though HPV vaccine willingness was high among Chinese guardians, they preferred to vaccinate their daughters at the age of 17–18 years, later than WHO’s recommended optimal age period (9–14 years old), coupled with safety concerns. Future work should be conducted based on these findings to explore digital intervention effects on girls’ vaccination compliance.

1. Introduction

Cervical cancer, the fourth most prevalent cancer among women, has emerged as a significant global public health concern [1]. According to Global Cancer Statistics 2022, approximately 660,000 new cervical cancer cases and 350,000 associated deaths occurred worldwide [2]. In China, both the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer have been increasing in recent years, accompanied by a trend toward a younger age of onset [3]. In 2022, China recorded an estimated 151,000 new cases (incidence rate: 13.8/100,000) and 56,000 deaths (mortality rate: 4.5/100,000), imposing a substantial burden on women’s health and social economy [4,5].

Persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) is the primary etiological factor in cervical cancer, with 71% of cervical cancer cases attributable to persistent infection with HPV 16 and 18 [6]. HPV vaccination represents the most critical intervention for preventing cervical cancer and HPV-associated diseases [7]. WHO recommends prioritizing HPV vaccination for adolescent girls prior to sexual exposure and setting a target of achieving a 90% full HPV vaccination rate among girls under 15 by 2030 [8]. As of April 2025, 147 countries have included the HPV vaccine into their National Immunization Programs (NIPs) [9].

At present, six HPV vaccines have been approved for use in China: bivalent Cervarix (approved in 2016, 81 USD per dose), quadrivalent Gardasil (approved in 2017, 111 USD per dose), nine-valent Gardasil 9 (approved in 2018, 181 USD per dose), bivalent Cecolin (approved in 2019, 46 USD per dose), bivalent Walrinvax (approved in 2022, 45 USD per dose), and nine-valent Cecolin 9 (approved in 2025, 70 USD per dose). The HPV vaccine has not yet been included in the Chinese NIP, and the vaccination rate among adolescent girls remains at a relatively low level [10]. As adolescent girls are typically financially dependent, the majority are unable to afford HPV vaccination independently. Consequently, guardians’ awareness of HPV and their attitudes towards the HPV vaccine are pivotal in shaping adolescent girls’ vaccine acceptance [11]. A comparative analysis of two meta-analyses of parents’ HPV vaccine acceptance for adolescents in mainland China over different periods indicates a notable increase in HPV awareness, HPV vaccine awareness, and HPV vaccine acceptance rates, which now stand at 45.0%, 41.4%, and 61.0%, respectively [12]. Nevertheless, compared to some developed nations, the understanding of HPV and attitudes towards the HPV vaccine among parents of adolescents in mainland China remain suboptimal [13].

Previous research has demonstrated that the guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance for girls is influenced by multiple determinants, with the guardians’ knowledge, practices, and preferences being key contributing factors [14]. The Health Belief Model offers a robust framework for predicting guardians’ beliefs and understanding of HPV and HPV vaccines, elucidating the underlying reasons for changes or maintenance of their attitudes towards HPV vaccination [15]. The Theory of Planned Behavior effectively describes guardians’ attitudes towards the HPV vaccine, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, serving as a guiding principle for exploring their intentions and behaviors [16]. Therefore, developing a Health Belief Model combined with the Theory of Planned Behavior could elucidate the factors influencing guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance precisely.

This study aimed to (1) assess guardians’ awareness of HPV and HPV vaccines; (2) evaluate acceptance of HPV vaccine and related influencing factors among guardians of 9–17 adolescent girls; (3) provide evidence for the development of more tailored and evidence-based health interventions to enhance the actual HPV vaccination coverage among adolescent girls.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study from May to September 2024 in Zhejiang province, eastern China; participants were recruited through a multi-stage stratified cluster random sampling method. In the first stage, we selected three cities representing distinct socioeconomic levels in Zhejiang Province (Hangzhou, Jinhua, and Quzhou). In the second stage, four districts or counties were selected from each city, where the population, economic development level, and the baseline HPV vaccination rate among girls aged 9 to 17 were comparable. In the third stage, four vaccination clinics were selected from each district or county. Participants were recruited through vaccination clinics, and inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) guardians had at least one girl aged 9 to 17 and resided in their district or county for at least 6 months; (2) the girls had not received the HPV vaccine previously.

The sample size of this study was calculated by the following formula:

According to previous literature [11], we set the expected acceptance of HPV vaccine at P = 50%, with α = 0.05, δ = 0.04, deff = 2.5; the minimum required sample size was calculated as 1500. Considering a potential 10% non-response rate, the total target sample size was adjusted to 1650.

This study has been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (No. 202407), and all respondents provided informed consent and voluntarily filled out the questionnaires.

2.2. Procedures

The questionnaire passed five rounds of expert evaluation (including CDC experts, community health service center staff, and guardian representatives). All investigators received standardized training. Prior to study implementation, a pilot study with 32 participants was conducted in Hangzhou. To enhance participants’ comprehension of the questionnaire, revisions were made based on feedback from pilot participants (including shortening the length and rephrasing technical questions into more accessible language). These 32 participants were not involved in the actual survey. During the survey process, quality control staff provided on-site supervision. After investigators provided a standardized explanation, the questionnaires were completed on-site to guarantee the authenticity and validity of the collected questionnaire information.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Health Belief Model

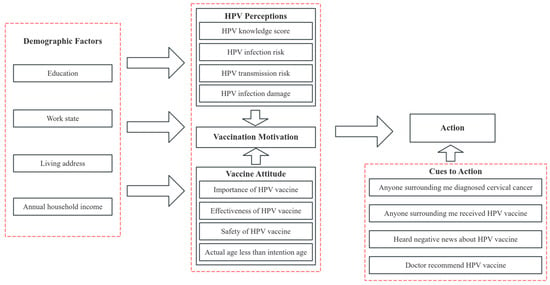

In our present study, the Health Belief Model and Theory of Planned Behavior were used as the theoretical framework to assess guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance for their girls. The Health Belief Model in our study comprised three dimensions: Guardians’ HPV Perceptions (3 items), Guardians’ Vaccine Attitude (4 items), and Cues to Action (4 items). The Health Belief Model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Health Belief Model of HPV vaccine acceptance for 9–17 girls among guardians.

2.3.2. Data Collection

In our present study, the questionnaire collected data on (1) Demographic Factors, including children’s characteristics, such as age, education level, and household registration province, and guardians’ characteristics, such as the relationship with children, education level, marital status, employment status, habitual residence, and annual household income; (2) Guardians’ HPV Perceptions, including HPV and HPV vaccine knowledge, HPV susceptibility, and HPV infection severity. HPV and HPV vaccine knowledge included aspects such as HPV transmission routes, cervical cancer, HPV vaccines, etc. Guardians’ HPV knowledge scores were categorized as high- or low-level based on whether their total score exceeded 5 points; (3) Guardians’ Vaccine Attitude, including the importance, effectiveness, and safety of the HPV vaccine, and the comparison between actual age of girls and intended vaccination age of guardians; (4) Cues to Action, including anyone surrounding me diagnosed with cervical cancer or who has received HPV vaccine, whether they had heard negative news about HPV vaccine, and whether doctors recommended HPV vaccine; (5) The channels of obtaining information for HPV and HPV vaccines; (6) Guardians’ HPV vaccine preference and reasons for refusing HPV vaccines. All questions were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree) or dichotomous items (yes/no). The questionnaire is shown in Appendix A.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R 4.3.2 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). As for categorical variables, frequencies or percentages were presented. The differences between intend and refuse vaccination groups were analyzed using the Chi-square test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Univariate analyses were used to explore the factors associated with guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance for girls. To illustrate the influence of each step of the HBM on the guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance for girls, the forward stepwise method was applied to conduct the multivariable logistic regression model. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test was used to assess the goodness of fit for each step. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 2541 guardians were selected to participate in the survey, and 2157 valid questionnaires were retrieved (valid questionnaire rate: 84.89%). Exclusion criteria: a girl’s age was not 9–17 years old (n = 64), guardians with the same girl (n = 132), guardians with highly repetitive responses (n = 188). The demographics and baseline characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. This study involved 2157 girls with balanced age distribution across three groups (9–11, 12–14, and 15–17 years), each comprising approximately one-third of the total participants. Education levels were predominantly primary school (39.8%), followed by junior high (31.1%) and senior/vocational high school (29.1%). A total of 2059 girls (95.46%) had household registration in Zhejiang province. The most common guardians’ relationship was mother (n = 1665, 77.19%). The majority of the guardians’ education level was an undergraduate degree or above (n = 1114, 51.65%). The number of guardians without a spouse was relatively low (n = 114, 5.29%). Most guardians were full-time employees (n = 1590, 73.71%), and most of them were urban residents (n = 1574, 72.97%). The largest proportion of the average annual household income was ≥ 100,000 yuan (n = 875, 40.57%). Among all participants, 1870 were willing to receive the HPV vaccine for their girls (86.69%).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of participants.

3.2. Guardians’ Awareness of HPV and HPV Vaccine

The guardians’ knowledge score of HPV, cervical cancer, and HPV vaccines is shown in Table 2. Among all participants, 68.1% were aware of the main transmission route of HPV, 91.19% were familiar with cervical cancer, and 87.48% acknowledged that HPV vaccination was the most cost-effective approach for preventing cervical cancer. The correct response rates for the seven questions regarding HPV and vaccine knowledge varied from 27.91% to 91.19%, and the knowledge scores ranged from 0 to 7 points (with a maximum score of 7 points), with an average score of 5.14 points (M = 5.14, SD = 1.69). 1235 guardians (57.26%) fell into the high-knowledge category.

Table 2.

Guardians’ knowledge of HPV, cervical cancer, and HPV vaccines.

3.3. Guardians’ HPV Vaccine Acceptance for Girls Aged 9–17

Univariate analyses on guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance for girls are shown in Table 3. Univariate analyses demonstrated that guardians’ education degree, employment status, habitual residence, annual household income, level of HPV and HPV-related diseases knowledge, perceived risk of HPV infection in their girls, perceived transmission risk after infection, perceived health consequences of HPV infection, anyone surrounding them diagnosed with cervical cancer or who has received HPV vaccines, regarding HPV vaccination as important for their girl’s health, perceiving HPV vaccines as effectiveness and safety, their girl’s actual age exceeded guardians’ intended vaccination age, having heard less negative information about HPV vaccines, and having received recommendations from doctors have significantly influenced guardians’ acceptance (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Univariate analyses on HPV vaccine acceptance for girls aged 9–17 among guardians.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses on guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance for their girls are shown in Table 4. In the final step, guardians with a family income ranging from 50,000 to 99,999 yuan (OR = 1.70, 95%CI = 1.03–2.80), or ≥100,000 yuan (OR = 1.94, 95%CI = 1.14–3.32), those who thought their children had an average or high risk of HPV infection (OR = 1.74, 95%CI = 1.04–2.93; OR = 3.15, 95%CI = 1.40–7.10), those who regarded HPV vaccination as very important for their children’s health (OR = 6.70, 95%CI = 1.61–27.83), those with anyone surrounding them who had received HPV vaccines (OR = 2.03, 95%CI = 1.41–2.92), and those who had received recommendations from doctors (OR = 2.32, 95%CI = 1.65–3.25) were statistically significant increased acceptance of HPV vaccine for girls among guardians. Guardians with a senior high school education (OR = 0.57, 95%CI = 0.37–0.87), those whose girl’s actual age was less than intended vaccination age (OR = 0.49, 95%CI = 0.32–0.75), and those who had heard negative news about HPV vaccines (OR = 0.59, 95%CI = 0.43–0.82) were statistically significantly associated with decreased acceptance of HPV vaccine for girls among guardians.

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses on HPV vaccine acceptance for girls aged 9–17 among guardians.

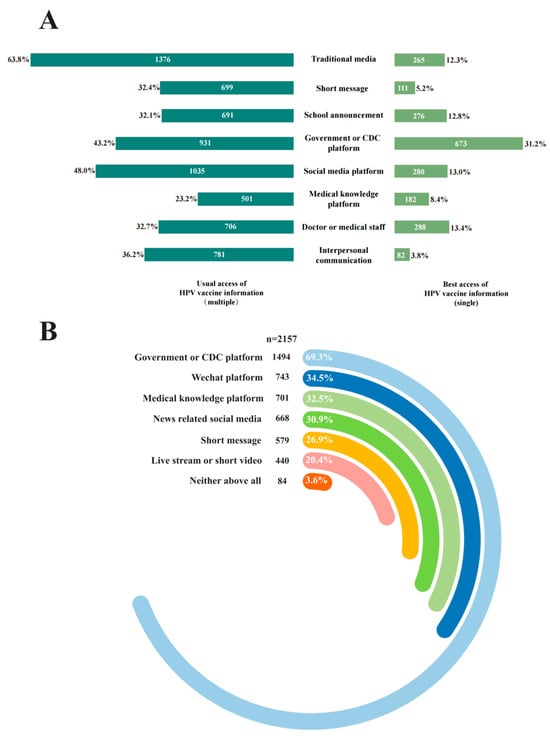

3.4. The Channels of Obtaining Information on HPV and HPV Vaccine

The channels of obtaining information for HPV and HPV vaccines are shown in Figure 2. Findings from the investigation indicated that guardians most frequently preferred obtaining HPV vaccination-related information through government or CDC platforms (n = 673, 31.20%), doctor or medical staff (n = 288, 13.35%), and social media platforms (n = 280, 12.98%) (Figure 2A). Regarding preferences for public education platforms, guardians overwhelmingly favored accessing HPV vaccine-related educational content through government or CDC platforms (n = 1494, 69.26%), WeChat platforms (n = 743, 34.45%), and medical knowledge platforms (n = 701, 32.50%) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

The channels of obtaining information for HPV and HPV vaccines. (A) The most preferred channel to receive vaccine-related information; (B) The most preferred public platform to receive HPV-related educational information.

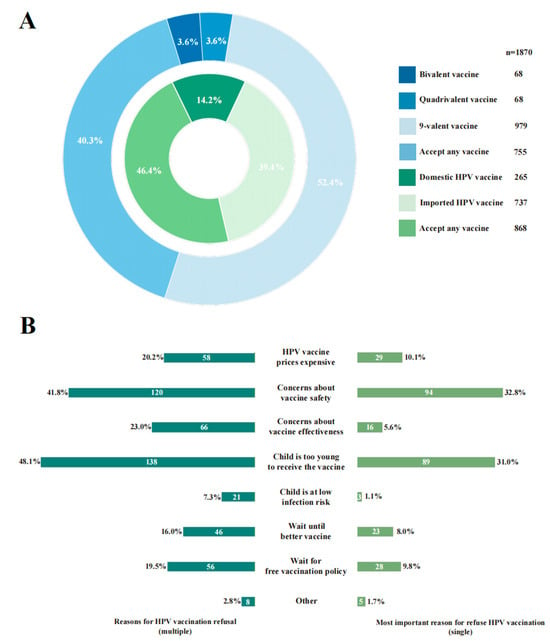

3.5. Guardians’ HPV Vaccine Preference and Reasons for Refusing HPV Vaccine

Guardians’ HPV vaccine preference and reasons for refusing HPV vaccines are shown in Figure 3. In terms of HPV vaccine preference, the majority of guardians expressed willingness to have their girl receive both domestic and imported HPV vaccines (n = 868, 46.42% selected “both acceptable”), with a pronounced preference for the 9-valent HPV vaccine (n = 979, 52.39%) (Figure 3A). Among guardians reluctant to vaccinate their daughters with HPV vaccines (n = 287, 13.31%), the primary reasons cited were concerns about vaccine safety (n = 94, 32.75%), the belief that the child was too young for immediate vaccination (n = 89, 31.01%), and the high cost of HPV vaccines (n = 29, 10.10%) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Guardians’ HPV vaccine preference and reasons for vaccine hesitancy. (A) Guardians’ HPV vaccine preference. (B) Reasons for HPV vaccine hesitancy among guardians.

4. Discussion

Guardians’ intentions play a pivotal role in determining HPV vaccination among adolescent girls [17]. In this study, guardians exhibited a high acceptance rate (86.7%) of the HPV vaccine for adolescent girls. This rate is significantly higher than the previous study in China (46.3%) [18] and another study in Zhejiang (56.5%) [19]. As an economically advanced province in eastern China, Zhejiang’s growing HPV vaccine acceptance among guardians can be attributed to the widespread dissemination of HPV vaccine-related knowledge [20].

Demographic characteristics were examined as fundamental determinants of HPV vaccination decisions. The multivariable analyses indicated that guardians with higher incomes exhibited significantly stronger HPV vaccine acceptance, consistent with findings from other studies [21]. As the HPV vaccine has not been included in the Chinese NIP, guardians must bear the full cost of HPV vaccination for adolescent girls. Thus, we advocate that the HPV vaccine be included in the NIP or implement financial subsidies and preferential policies to enhance HPV vaccination coverage among adolescent girls, ensuring accessible pricing for economically disadvantaged groups is critical [22].

Guardians’ HPV perceptions were assessed to quantify their disease risk awareness in relation to vaccine acceptance. Although guardians’ HPV knowledge showed no statistically significant difference in HPV vaccine acceptance when other factors were included in multivariable analyses, guardians’ HPV knowledge still revealed a positive association between higher HPV knowledge levels and stronger HPV vaccine acceptance in univariate analyses. This suggests that with widespread HPV and HPV vaccine education, guardians generally had a better understanding, making HPV knowledge no longer an influencing factor [23]. Also, perceiving their girls as being at higher risk of HPV infection significantly increased guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance for girls, consistent with findings from other studies [24]. Thus, tailored intervention messages on HPV susceptibility for guardians are more effective in enhancing health literacy regarding HPV vaccination among adolescent girls than conventional HPV public education [25].

Guardians’ vaccine attitude was quantified as a critical determinant of guardian-mediated vaccine hesitancy. This step exerted the strongest influence on HPV vaccine acceptance. The multivariable analyses showed that perceiving HPV vaccination as important for their girls’ health significantly increased guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance for girls. While belief in vaccine efficacy and safety is often cited as a symbol of vaccine confidence [26], due to the high safety profile of licensed HPV vaccines in China, supported by long-term post-market surveillance [27], these factors showed no statistically significant difference when they were included in multivariable analyses. In this context, guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance appears to be driven by rational health assessments and risk prevention awareness. Additionally, this study found a positive correlation between girls’ age and guardians’ vaccination intention age, with younger girls’ guardians being more reluctant to vaccination, consistent with findings from other studies [28]. This suggests that guardians intend to allow their girls to receive the HPV vaccine until they are older. Therefore, emphasizing the importance of timely vaccination during the optimal age window may be a key strategy to enhance guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance.

Cues to action were analyzed as accelerators of the vaccine decision-making process. The multivariable analyses indicated that guardians who had not heard about negative news about HPV vaccines or had social contacts who received the HPV vaccines exhibited stronger HPV vaccine acceptance. Another study shows that relatives and friends play a pivotal role in shaping guardians’ attitudes, with vaccinated individuals alleviating others’ distrust [29], which is consistent with our study. Doctor or medical staff recommendations also significantly boosted guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance for girls, consistent with multiple studies demonstrating the positive impact of medical advice on vaccination decisions [30]. This highlights the critical role of healthcare providers in health education for promoting HPV vaccination and reducing cervical cancer incidence [31]. Therefore, when designing intervention strategies, environmental factors could impact guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance, with health education by medical personnel serving as a guide. Engaging HPV vaccine recipients to collectively disseminate information can further strengthen vaccine confidence among information recipients.

In addition to interpersonal communication, digital health interventions also have been shown to reduce HPV vaccines hesitancy [32], with sustained media exposure influencing public immunization trends [33]. This study found that guardians most expected to receive HPV or HPV vaccines information from government or CDC platforms, doctor or medical staff, and social media platforms. Additionally, guardians preferred digital channels like government or CDC platforms, WeChat platforms, and medical knowledge platforms to obtain public education on HPV vaccination. This indicates that guardians exhibit a stronger preference for receiving information disseminated by authoritative institutions, consistent with findings from other studies [34]. Additionally, our study revealed no statistically significant differences in channels for obtaining HPV information between guardians’ HPV vaccine acceptance for girls. This may be attributed to the mixed positive and negative influences of HPV vaccine information from different channels [35]. This finding emphasizes the need for future studies to dissect how different information channels either facilitate or hinder HPV vaccine acceptance, rather than limiting the focus on access to information.

In terms of guardians’ HPV vaccine preferences, over 50% guardians preferred the 9-valent HPV vaccine for their daughters. This suggests that guardians preferred higher-valent HPV vaccines for their girls, consistent with multiple studies [18,24]. Among guardians’ reasons for refusing the HPV vaccine, the primary reasons cited were concerns about vaccine safety, the belief that their girls were too young, and the high cost of the HPV vaccine, consistent with findings from other studies [36,37]. To advance the WHO’s “90-70-90” targets, tailored health education interventions are essential to build guardians’ confidence in HPV vaccines, increase girls’ vaccination rates, and ultimately reduce cervical cancer incidence.

Limitation

This study has several limitations. First, this study was a cross-sectional design, only allowing for correlation analysis between variables; causal inference cannot be established from the current data. Second, participants may provide answers they view as ideal, which may inflate self-reported vaccination intent due to social desirability bias. Furthermore, this study was commenced in May 2024, prior to China’s immunization program strategy required that HPV vaccines should be prioritized for female recipients. The sample comprised guardians of adolescent girls only, limiting generalizability for guardians of adolescent boys. Additionally, while HPV vaccination decisions are multifactorial and guardians’ attitudes may be influenced by adolescent girls’ own preferences, this study did not fully account for adolescent girls’ vaccination acceptance. Finally, the study sample consisted of individuals who voluntarily enrolled through vaccination clinics, which inherently represents a population with more positive attitudes toward HPV vaccines and higher vaccination intent, introducing potential volunteer bias.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that guardians of adolescent girls in Zhejiang Province had a good level of awareness regarding HPV and HPV vaccines. HPV vaccine acceptance was 86.7%, which was associated with guardians’ household income, perceived HPV infection risk in girls, perceived health importance of the vaccine, vaccination status of friends, awareness of negative vaccine information, and medical staff recommendations. Remarkably, we found Chinese guardians preferred to vaccinate their daughters at the age of 17–18 years, which was later than the WHO’s recommended optimal age period (9–14 years), coupled with their safety concerns, contributing to vaccine hesitancy. In addition, guardians preferred to obtain digital information on the vaccine via government or CDC platforms, WeChat platforms, and medical knowledge platforms. At the same time, we have established an intervention cohort by delivering health messages monthly on vaccines and related diseases through government or CDC official channels for 6 months. Future evaluations will be conducted to explore the effects of digital intervention on vaccination compliance using a follow-up questionnaire from guardians. This will provide a more robust theoretical foundation for implementing digital health interventions in vaccination promotion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.D. and L.L.; methodology, H.H., S.W., Y.C. and X.D.; formal analysis, F.L.; investigation, S.Z.; resources, X.X.; data curation, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.D. and Y.C.; supervision, H.H. and S.W.; project administration, X.D. and L.L.; funding acquisition, H.H., S.W., X.D., and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Zhejiang Provincial Science and Technology Program for Disease Prevention and Control (2025JK179), Scientific Research Project of Zhejiang Preventive Medicine Association (2025-B-06), and Zhejiang Provincial Medical Science and Technology Program Project (2022KY714, 2023KY629).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki,] and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (protocol code 202407, 5 July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| NIP | National Immunization Program |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control |

| HBM | Health Belief Model |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| 95%CI | 95% Confidence Interval |

Appendix A

HPV Vaccine Questionnaire

(For guardians of girls aged 9–17 years)

Instructions□

|

Location of survey:

Date of survey: □□ Day □□ Month □□□□ Year

I. Basic Information

| 1. Your name:__________________________ 2. Your phone number:□□□□□□□□□□□ 3. Your children’s name: __________________________ 4. Your children’s ID number:□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□ 5. Your children’s gender: ①Male ②Female 5.1 Your children’s birthday: □□Day □□Month □□□□Year 6. Your children’s education level? ①Primary school ②Junior high school ③Senior or vocational high school 7. Your children’s household registration province? ①Zhejiang province ②Other province 8. Your relationship with children? ①Father ②Mother ③Grandparents ④Other 9. Your gender: ①Male ②Female 10. Your age: □□Years old 11. Your education level?①Junior high school or lower ②Senior high school ③Undergraduate or above 12. Your marital status? ①Married ②Unmarried ③Other (including divorced or widowed) 13. Your employment status? ①Full-time job ②Part-time job ③Housework and unemployment ④Other 14. In the past year, where was your habitual residence? ①Rural ②Urban 15. In the past year, what was your annual household income? ①Less than 20,000 ②20,000–49,999 ③50,000–99,999 ④More than 100,000 |

II. HPV perceptions

| 16. Do you think the following statement is correct? 16.1 HPV is mainly transmitted through sexual transmission. ①Yes ②No 16.2 Cervical cancer is one of the most common gynecological cancers in China. ①Yes ②No 16.3 HPV vaccination is the most cost-effective way to prevent cervical cancer. ①Yes ②No 16.4 HPV vaccine is recommended for women over 18 years old. ①Yes ②No 16.5 Available HPV vaccines are divided into 2-, 4-, and 9-valent vaccines. ①Yes ②No 17. When is the optimal age for HPV vaccination? ①After birth ②Before first sex ③After first sex ④Any time is OK ⑤Unknown 18. Do you think cervical cancer screening is necessary after HPV vaccination? ①Necessary ②Unnecessary ③Unknown 19. What do you think your children’s risk of HPV infection is? ①Very low ②Low ③Neither low nor high ④High ⑤Very high 20. What do you think your children’s risk of transmitting HPV to others is? ①Very low ②Low ③Neither low nor high ④High ⑤Very high 21. How damaging do you think HPV infection is to your child’s health? ①Absolutely not severe ②Not severe ③Neutral ④Severe ⑤Very severe |

III. Vaccine attitude

| 22. Do you think HPV vaccination is important for your children’s health? ①Very unimportant ②Unimportant ③Neutral ④Important ⑤Very important 23. What do you think of the effectiveness of the HPV vaccine? ①Very ineffective ②Ineffective ③Neutral ④Effective ⑤Very effective 24. What do you think of the safety of the HPV vaccine? ①Very unsafe ②Unsafe ③Neutral ④Safe ⑤Very safe 24.1. When do you think it is appropriate to vaccinate children with the HPV vaccine? ①Junior high school ②Senior high school ③Undergraduate ④Above all |

IV. Cues to action

| 25. Do you know anyone close to you has been diagnosed with cervical cancer? ①Yes ②No 26. Have you or anyone surrounding you received HPV vaccine?【Multiple】 ①Myself ②Family members ③Relatives ④Friends ⑤Classmates ⑥Colleagues ⑦Others___________________________ ⑧None above all 27. Have you heard the negative news about HPV vaccine? ①Yes ②No 28. Has a doctor recommended HPV vaccine for your children? ①Yes ②No |

V. Digital information services

| 29. Which of the following channels are your usual access to HPV vaccine information?【Multiple】 ①Television and radio ②Newspapers, magazines and journal ③Mobile phone short message ④School announcement ⑤Government or CDC platform ⑥Social media platform(Wechat, Sina Weibo, Tiktok, etc.) ⑦Medical knowledge platform ⑧Doctor or medical staff ⑨Family members, relatives, or friends ⑩Others ⑪Never heard about this vaccine 30. Which of the following channels is your best access to HPV vaccine information? ①Television and radio ②Newspapers, magazines and journal ③Mobile phone short message ④School announcement ⑤Government or CDC platform ⑥Social media platform(Wechat, Sina Weibo, Tiktok, etc.) ⑦Medical knowledge platform ⑧Doctor or medical staff ⑨Family members, relatives, or friends ⑩Others ⑪Never heard about this vaccine 31. Would you like to receive public education about HPV vaccination through your mobile phone regularly (such as once a month)? ①Yes ②No 32. Which of the following public education platforms about HPV vaccination are you willing to check?【Multiple】 ①Government or CDC platform ②Wechat platform ③Short message ④News-related social media ⑤Live stream or short video ⑥Medical knowledge platform ⑦Others________________________________ ⑧Neither above all |

VI. HPV vaccine acceptance

| 33. Would you be willing to vaccinate your children with HPV vaccine? ①Yes 33.1 Would you prefer to vaccinate your child with domestic or imported HPV vaccine? ①Domestic vaccine ②Imported vaccine ③Accept any vaccine 33.2 Which HPV vaccine would you prefer to give your children? ①Bivalent vaccine ②Quadrivalent vaccine ③9-valent vaccine ④Accept any vaccine This is the end of the survey, thank you very much for your participation! |

| ②No 33.3 Which of the following reasons are you reluctant to vaccinate your children with HPV vaccine?【Multiple】 ①HPV vaccine prices expensive ②Concerns about HPV vaccine safety ③Concerns about HPV vaccine effectiveness ④Child is too young to vaccine ⑤Child is at low infection risk ⑥Wait until better vaccine ⑦Wait for free vaccination policy ⑧Others______________________ 33.4 Which of the following reasons is your most important reluctant to vaccinate your children with HPV vaccine? ①HPV vaccine prices expensive ②Concerns about HPV vaccine safety ③Concerns about HPV vaccine effectiveness ④Child is too young to vaccine ⑤Child is at low infection risk ⑥Wait until better vaccine ⑦Wait for free vaccination policy ⑧Others______________________ This is the end of the survey, thank you very much for your participation! |

References

- eClinicalMedicine. Global strategy to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem: Are we on track? eClinicalMedicine 2023, 55, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Huang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, F. Temporal trends in incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in China from 1990 to 2019 and predictions for 2034. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2024, 33, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2022; Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Bonjour, M.; Charvat, H.; Franco, E.L.; Pineros, M.; Clifford, G.M.; Bray, F.; Baussano, I. Global estimates of expected and preventable cervical cancers among girls born between 2005 and 2014: A birth cohort analysis. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e510–e521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.Q.; Hao, J.Q.; Mendez, M.J.; Mohamed, S.B.; Fu, S.L.; Zhao, F.H.; Qiao, Y.L. The Prevalence of Cervical HPV Infection and Genotype Distribution in 856,535 Chinese Women with Normal and Abnormal Cervical Lesions: A Systemic Review. J. Cytol. 2022, 39, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahangdale, L.; Mungo, C.; O’Connor, S.; Chibwesha, C.J.; Brewer, N.T. Human papillomavirus vaccination and cervical cancer risk. BMJ 2022, 379, e070115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper (2022 update). Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2022, 97, 645–672. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. HPV Vaccine Included in National Immunization Programme. Available online: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiNDIxZTFkZGUtMDQ1Ny00MDZkLThiZDktYWFlYTdkOGU2NDcwIiwidCI6ImY2MTBjMGI3LWJkMjQtNGIzOS04MTBiLTNkYzI4MGFmYjU5MCIsImMiOjh9 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- National Health Commission. Action plan for accelerating the elimination of cervical cancer (2023–2030). Chin. J. Viral Dis. 2023, 13, 243–244. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, Z.; Ma, J.; Wang, F.; Jia, B. HPV vaccination willingness among 3,081 secondary school parents in China’s capital. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2025, 21, 2477383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.; Yu, W. Awareness and acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccine among parents of adolescents in Chinese mainland: A meta-analysis. Chin. J. Vaccines Immun. 2019, 25, 464–470. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.; Wang, S.; Zou, X.; Jia, X.; Tong, C.; Yin, J.; Lian, X.; Qiao, Y. Parental willingness of HPV vaccination in Mainland China: A meta-analysis. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2024, 20, 2314381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, A.K.; Ketcher, D.; McCormick, R.; Davis, J.L.; McIntyre, M.R.; Liao, Y.; Reblin, M.; Vadaparampil, S.T. Using the health belief model to assess racial/ethnic disparities in cancer-related behaviors in an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center catchment area. Cancer Causes Control 2021, 32, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: A decade later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.Y.; Okeke, E.; Anglemyer, A.; Brock, T. Identifying Perceived Barriers to Human Papillomavirus Vaccination as a Preventative Strategy for Cervical Cancer in Nigeria. Ann. Glob. Health 2020, 86, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwendener, C.L.; Kiener, L.M.; Jafflin, K.; Rouached, S.; Juillerat, A.; Meier, V.; Maurer, S.S.; Muggli, F.; Gültekin, N.; Baumann, A.; et al. HPV vaccine awareness, knowledge and information sources among youth in Switzerland: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e054419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, J.; Zhang, X.; Guo, X.; Yu, W. Willingness of parents of 9-to-18-year-old females in China to vaccinate their daughters with HPV vaccine. Vaccine 2023, 41, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ling, J.; Zhao, X.; Lv, Q.; Wang, L.; Wu, Q.; Xu, S.; Zhang, X. Are HPV Vaccines Well Accepted among Parents of Adolescent Girls in China? Trends, Obstacles, and Practical Implications for Further Interventions: A Five-Year Follow-Up Study. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolarczyk, K.; Duszewska, A.; Drozd, S.; Majewski, S. Parents’ Knowledge and Attitude towards HPV and HPV Vaccination in Poland. Vaccines 2022, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram Değer, V.; Yiğitalp, G. Level of hesitation of parents about childhood vaccines and affecting factors: A cross-sectional study in Turkey. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Su, Z.; Chen, F.; Zhao, Q.; Zimet, G.D.; Alias, H.; He, S.; Hu, Z.; Wong, L.P. Chinese mothers’ intention to vaccinate daughters against human papillomavirus (HPV), and their vaccine preferences: A study in Fujian Province. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, A.C.; Pineda, J.A.; Valdez, M.J.; Torres, M.I.; Granberry, P.J. Central American Immigrant Parents’ Awareness, Acceptability, and Willingness to Vaccinate Their Adolescent Children Against Human Papillomavirus: A Pilot Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhou, W.; Wen, X.; Lu, J.; Lu, X.; Lu, Y. Discrepancy of human papillomavirus vaccine uptake and intent between girls 9–14 and their mothers in a pilot region of Shanghai, China. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18, 2132801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A.; Fisher, C.B. Factors associated with HPV vaccine acceptability and hesitancy among Black mothers with young daughters in the United States. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1124206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, A.S.; Tiro, J.A.; Zimet, G.D. Broad perspectives in understanding vaccine hesitancy and vaccine confidence: An introduction to the special issue. J. Behav. Med. 2023, 46, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; He, W.; Wu, X.; Gu, J.; Zhang, J.; Lin, B.; Bi, Z.; Su, Y.; Huang, S.; Hu, Y.; et al. Long-Term immunopersistence and safety of the Escherichia coli-produced HPV-16/18 bivalent vaccine in Chinese adolescent girls. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18, 2061248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, L. Investigation on cognition, vaccination intention and related factors of parents of middle school students about HPV and its vaccine in Yuzhong District of Chongqing. J. Mod. Med. Health 2024, 40, 2799–2803. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.Y.; Zimet, G.D.; Latkin, C.A.; Joseph, J.G. Social Networks for Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Advice Among African American Parents. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 65, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, L.; Cao, M.; Liu, P.; Liu, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, J. Parental preference for Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccination in Zhejiang Province, China: A discrete choice experiment. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 967693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanadhan, S.; Fontanet, C.; Teixeira, M.; Mahtani, S.; Katz, I. Exploring attitudes of adolescents and caregivers towards community-based delivery of the HPV vaccine: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Tamí-Maury, I.; Cuccaro, P.; Kim, S.; Markham, C. Digital Health Interventions to Improve Adolescent HPV Vaccination: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2023, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Yan, D.; Liang, S. The Relationship between Information Dissemination Channels, Health Belief, and COVID-19 Vaccination Intention: Evidence from China. J. Environ. Public Health 2023, 2023, 6915125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shegog, R.; Savas, L.S.; Healy, C.M.; Frost, E.L.; Coan, S.P.; Gabay, E.K.; Preston, S.M.; Spinner, S.W.; Wilbur, M.; Becker, E.; et al. AVPCancerFree: Impact of a digital behavior change intervention on parental HPV vaccine -related perceptions and behaviors. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18, 2087430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Chen, S.; Su, L.; Liao, Y.; Chen, H.; Hu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Fang, Y.; Liang, X.; Chen, J.; et al. Influences of HPV disease perceptions, vaccine accessibility, and information exposure on social media on HPV vaccination uptake among 11,678 mothers with daughters aged 9–17 years in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihretie, G.N.; Liyeh, T.M.; Ayele, A.D.; Belay, H.G.; Yimer, T.S.; Miskr, A.D. Knowledge and willingness of parents towards child girl HPV vaccination in Debre Tabor Town, Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, N.; de la Cueva, I.S.; Taborga, E.; de Alba, A.F.; Cabeza, I.; Raba, R.M.; Marès, J.; Company, P.; Herrera, B.; Cotarelo, M. HPV knowledge and vaccine acceptability: A survey-based study among parents of adolescents (KAPPAS study). Infect. Agents Cancer 2022, 17, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).