1. Introduction

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV), a neurotropic alphaherpesvirus, initially manifests as varicella (chickenpox) upon primary infection before establishing lifelong latency in sensory ganglia. Reactivation of the latent virus causes herpes zoster (HZ, shingles), with a global incidence of 10 cases per 1000 person over 60 years old every year [

1]. Notably, 5–30% of HZ patients develop postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), and other severe complications include stroke and meningitis [

2]. The widely used vaccine Shingrix (GSK), a recombinant subunit vaccine, significantly reduces the risk of herpes zoster by 97.2% in older adults [

3]. Although high-efficacy, Shingrix is associated with adverse events [

4], including third nerve palsy [

5] and retinal necrosis [

6]. Meanwhile, live attenuated vaccines face challenges, including age-related waning immunity, residual neurotropism, and contraindications in high-risk groups [

7].

VZV-specific cell-mediated immunity (CMI) plays a crucial role in suppressing latent VZV reactivation and promoting HZ recovery. Studies of human ganglia with active HZ or with no history of HZ revealed abundant CD4

+ T cells and cytotoxic CD8

+ T cells (Granzyme B

+) in activated ganglia, with CD8

+ T cells localized closer to neurons [

8]. A cohort study of 12,522 adults aged ≥50 years further demonstrated that VZV-CMI intensity (measured by skin test erythema diameter) correlates with reduced HZ incidence, symptom severity, and PHN risk, whereas humoral responses alone did not correlate with reduced HZ incidence/severity in that cohort [

9]. Aging and immunosuppression lead to declined VZV-CMI, increasing HZ recurrence risk [

10,

11]. These findings highlighted that CD4

+/CD8

+ T cells synergistically control the virus during VZV reactivation.

Current vaccines like Shingrix, while effectively eliciting humoral immune responses and CD4

+ T-cell responses via the AS01B adjuvant system, demonstrate a near inability to induce CD8

+ T-cell responses [

12]. In the design of vaccines aimed at efficiently inducing cellular immune responses, adenovirus vectors are highly favored due to their inherent self-adjuvant effect and potent capacity to induce cellular immunity. Furthermore, chimpanzee adenovirus vectors circumvent prevalent pre-existing immunity challenges due to their low seroprevalence in humans. This advantage is exemplified by the successful deployment of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222, AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK) against COVID-19. Leveraging this platform, we developed a novel candidate vaccine, ChAdOx1-VZV (CVE), in which the major VZV envelope glycoprotein, full-length of glycoprotein E (gE), serves as the antigen.

Evidence from aerosolized Ad5-nCoV, a replication-deficient human adenovirus type 5 COVID-19 vaccine, has shown that mucosal boosting after prior immunization markedly enhances both systemic and mucosal immunity while requiring lower doses [

13,

14]. Therefore, we evaluated a sequential regimen consisting of intramuscular (IM) priming followed by intranasal (IN) mucosal boosting in mice. Although animal models do not fully recapitulate VZV latency in humans, this IM-prime/IN-boost (IM + IN) strategy enables assessment of systemic and mucosal cellular responses. We hypothesize that the IM + IN CVE regimen induces a more balanced CD4

+/CD8

+ T-cell response, durable antibody production, and enhanced memory formation compared with current subunit vaccination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Immunization

Female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks) were immunized intramuscularly (IM) or intranasally (IN) with ChAdOx1-VZV at intervals defined by the study design. Prior to immunization, vaccines were prepared to the appropriate concentration. For IM immunization, mice were injected with 50 µL per dose into the hind limb muscle. For IN immunization, the total volume was 100 µL, administered in two separate doses to avoid expulsion or swallowing. Mice were first anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation and positioned vertically as the nasal cavity, trachea, and lungs were aligned in a straight line. Using a micropipette, approximately 3–5 µL of vaccine suspension was gently applied near one nostril at a time and allowed to be inhaled spontaneously through normal breathing. A total of 50 µL was administered each time, and after approximately 2 h, the same procedure was repeated to deliver the remaining 50 µL.

Saline was used as a negative control, and recombinant herpes zoster subunit vaccine (Shingrix) was used as a positive control. Retro-orbital blood samples were collected, and serum was separated at indicated time points to determine gE-specific antibodies. In addition, spleen, PBMCs, and bone marrow were harvested from experimental mice to evaluate gE-specific T-cell responses and/or antibody-secreting cells, as required by the study design.

Cynomolgus macaque model experiments were conducted by JOINN (Suzhou, China) New Drug Research Center Co., Ltd.

2.2. Isolation of Splenocytes, PBMCs, and Bone Marrow Cells

Splenocytes, PBMCs, and bone marrow cells were prepared using standard protocols. For splenocyte isolation, mice were euthanized and surface-sterilized by immersion in 75% ethanol. Spleens were aseptically excised, cut into ~3 mm fragments, and transferred into 2 mL of ACK lysis buffer. Tissues were mechanically dissociated using a DSC-800 tissue grinder (RWD Life Science, Shenzhen, China) for 1 min, followed by red blood cell (RBC) lysis for 4 min at room temperature. The reaction was quenched with 9 mL DMEM containing 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cell suspensions were filtered through a 70 µm strainer, centrifuged, and resuspended in complete RPMI 1640 medium (10% FBS, 1% penicillin–streptomycin).

PBMCs were isolated from peripheral blood collected into anticoagulant-treated tubes. A total of 300 µL of anticoagulated blood was collected form each mouse (n = 3~6), with samples from the same group pooled together for easy separation. The blood was then diluted with PBS at a ratio of 5:2. The diluted blood samples were carefully layered onto Ficoll (TBD science, Tianjin, China) in 15 mL centrifuge tubes and centrifuged continuously at 500 g for 30 min at room temperature. The PBMC layer at the plasma–Ficoll interface was collected, washed twice with PBS (250 g, 10 min), and resuspended in complete culture medium.

For bone marrow preparation, femurs and tibias were isolated, immersed in 75% ethanol for 30 s, and rinsed with PBS. Bone ends were cut, and marrow was flushed out with PBS using a syringe. Following centrifugation, the pellet was treated with 1 mL ACK lysis buffer to remove RBCs, and the reaction was stopped with 10 mL RPMI 1640 medium containing 1% FBS. Cells were filtered through a 70 µm strainer, centrifuged, and resuspended in complete culture medium.

All cell preparations were counted, assessed for viability, and used immediately for downstream assays or stored on ice.

2.3. ELISA

Purified recombinant gE protein was diluted to 2 μg/mL in sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.5) and coated onto 96-well plates (100 μL/well) at 4 °C for 18–24 h. Plates were washed with PBST (PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20) and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Solarbio, Beijing, China) in PBST for 1 h at 37 °C. Serum samples were serially diluted in PBS starting at 1:1000 with a two-fold dilution factor and added to the antigen-coated wells (100 μL/well) for 1 h at 37 °C. After four washes with PBST, HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China) (1:8000 in PBS) was added (100 μL/well) and incubated for 1 h at RT. Plates were developed with TMB substrate according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the reaction was stopped with 100 μL of 2 M H2SO4. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. The IgG titer was defined as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution yielding an optical density (OD) ≥2.1-fold above the negative control.

2.4. Flow Cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were seeded into 96-well U-bottom plates and stimulated with gE-specific peptide pools (GL Biotech, Shanghai, China). Cells stimulated with PMA and ionomycin (Dakewe, Shenzhen, China) served as positive controls. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. GolgiStop and GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were added 2 h after stimulation to block cytokine secretion, and incubation continued for another 4 h. Cells were then washed with PBS, stained with Zombie Aqua (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) for live/dead discrimination (RT, 10 min), and subsequently incubated with antibody cocktails for surface markers without washing. Surface staining was performed with CD3-PE-Vio770 (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), CD4-PerCP-Vio700 (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), and CD8-APC-H7 (BD) for another 15 min staining. After PBS washing, cells were fixed and permeabilized overnight at 4 °C using the Fixation/Permeabilization Kit (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, USA), followed by intracellular staining with fluorescent antibodies, and TNFα-FITC (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), IFNγ-PE (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), and IL-2-APC (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) were added and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C.

For memory T-cell surface staining, CD3-PE-Vio770 and CD4-PerCP-Vio700, CD8-APC-H7, CD44-VioBlue (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), CD62L-FITC (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), and CD103-Alexa Fluor (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) were used. And memory T-cell ICS staining was performed using IFNγ-PE and IL-2-APC.

2.5. IFNγ-ELISpot

The frequency of gE-specific cytokine-secreting cells was determined by the ELISpot assay. Then, 96-well Multiscreen PVDF plates (Merck Millipore, Burlington, VT, USA) were activated with 50 μL 70% ethanol per well for 1 min, washed five times with distilled water, and coated overnight at 4 °C with anti-mouse IFN-γ coating antibody (Mabtech AB, Nacka, Sweden). After washing, plates were blocked with RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 2 h at room temperature. Isolated cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were added in the presence of a gE-specific peptide pool (2 μg/mL); wells containing DMSO alone served as background controls. Wells containing 2 × 104 cells stimulated with PMA and ionomycin served as positive controls. Plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

After incubation, plates were washed five times with PBS, and biotin-IFN-γ detection antibody (Mabtech, AB, Nacka, Sweden) was added for 2 h incubation at room temperature. Following five washes, Streptavidin–alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (Mabtech, AB, Nacka, Sweden) was added (100 μL/well) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Plates were washed five times, and 100 μL BCIP/NBT substrate (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA) was added per well. Spots were developed for 15–45 min at 37 °C, and plates were then thoroughly rinsed with water. Spots were enumerated using a CTL ImmunoSpot S6 Analyzer (ImmunoSpot, Cleveland, OH, USA). Antigen-specific IFN-γ spot counts were calculated after background subtraction (subtracting spots in DMSO wells). Plates were thoroughly rinsed with water, and spot-forming cells (SFCs) were enumerated for duplicate wells using a CTL ImmunoSpot S6 Analyzer. Data are reported as the average SFCs per duplicate well.

2.6. B Cell ELISpot

PVDF filter plates were activated by adding 50 μL of 70% ethanol per well for 1 min, followed by five washes with distilled water and coating with 5 μg/well of gE protein overnight at 2–8 °C. Plates were washed five times with PBST and blocked with 5% skim milk for 2 h at RT. Bone marrow cells were plated at 2 × 105 cells/well onto gE-coated membranes and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Plates were then washed five times with PBST, and secreted antibodies were detected by incubation with ALP-conjugated polyclonal goat anti-mouse IgG (100 μL/well; 1:10,000 dilution in PBST) for 2 h at RT. After five washes, 100 μL/well of BCIP/NBT substrate solution was added and allowed to develop for 15–40 min at RT. Plates were thoroughly rinsed with water, and spot-forming cells were enumerated for duplicate wells using a CTL ImmunoSpot S6 Analyzer (ImmunoSpot, Cleveland, OH, USA). Data are reported as the average SFCs per duplicate well.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM for cellular readouts and as geometric mean ± geometric SD for antibody titers, unless otherwise specified. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 8). For comparisons involving more than two groups under single or multiple factors, one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test was used. When only two groups were compared, unpaired two-tailed t tests were applied. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001 were indicated as *, **, ***, and ****, respectively.

4. Discussion

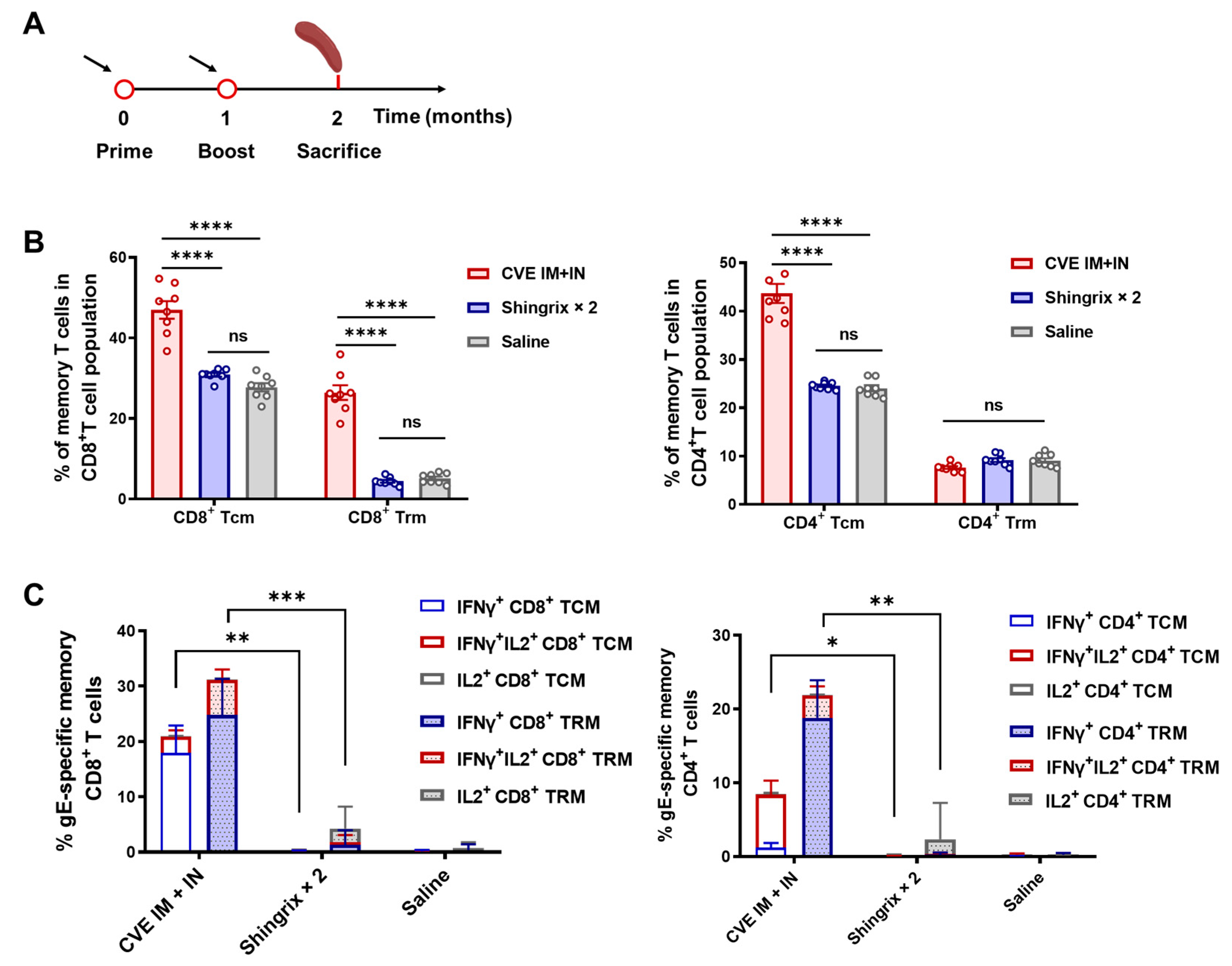

This study developed a novel chimpanzee adenoviral vector vaccine, ChAdOx1-VZV (CVE), expressing VZV gE, and showed that a heterologous IM-prime/IN-boost regimen enhances both cellular and humoral responses. CVE induced dominant CD8+ T-cell responses and measurable CD4+ T-cell responses while establishing LLPCs and memory T cells (TCMs and TRMs), indicating the potential for long-term protection against herpes zoster.

A comparison with current vaccines like Shingrix revealed that CVE effectively elicited humoral immunity and CD4

+ T cells via AS01B but showed near inability to induce CD8

+ T-cell responses. Under the heterologous regimen, CVE compensated for this shortcoming by generating robust CD8

+ T-cell responses while also increasing gE-IgG and LLPCs, though antibody levels remained lower than two-dose Shingrix. This suggests an immunological complementarity in which CVE provides a cellular immune barrier alongside sustained antibody supply. The rationale for the heterologous IM-prime/IN-boost strategy is evidenced from aerosolized Ad5-nCoV clinical trials, which indicate that mucosal boosting after prior immunization can enhance systemic and mucosal immunity at lower doses [

13,

14]. Consistent with this, our IM + IN regimen elevated CD4

+/CD8

+ T cells after IM priming and augmented humoral responses, supporting intranasal boosting as an effective strategy following intramuscular priming.

The induced LLPCs in bone marrow support long-term antibody homeostasis independently of memory B cells [

15,

16]. The expansion of TCMs provides a basis for systemic immune surveillance, while TRMs contribute to barrier defense. Together, these features suggest a “dual-layer” immune pattern of a cellular immune barrier plus long-term supply of antibodies.

In addition, given that >90% of adults harbor latent VZV with baseline immune memory [

17,

18,

19], a single mucosal dose could provide clinically meaningful protection in populations with widespread pre-existing immunity, particularly for rapid enhancement of cell-mediated immunity or post-exposure scenarios. For individuals with weaker baseline memory, an IM-prime/IN-boost schedule may offer a more balanced and durable enhancement of both antibody and T-cell compartments. Although animal models cannot fully recapitulate human latency, these data provide a rationale for advancing CVE heterologous strategies.

Although murine models are invaluable for evaluating vaccine immunogenicity, they cannot fully reflect the complex biology of VZV latency and reactivation in humans. Particularly, mice cannot mimic VZV latency in humans, which limits the direct assessment of protective efficacy against herpes zoster. This limitation is especially relevant for older adults and immunocompromised individuals, in whom immune activity and impaired CMI elevate the risk of reactivation. Considering that VZV vaccines are primarily intended for older populations, clinical data from Ad5-nCoV vaccination in individuals aged ≥60 years provide relevant translational insight [

20]. In elderly participants, Ad5-nCoV elicited moderately reduced antibody responses relative to younger adults, whereas the inactivated vaccine showed a pronounced decline in immunogenicity in older populations. These findings suggest that age-related immune attenuation may differentially influence vaccine platforms, offering a meaningful reference for the development of a ChAdOx1-vectored VZV vaccine.

Moreover, given the restricted susceptibility of murine and other animal models to VZV infection, evaluating true vaccine efficacy remains a major barrier. Human-derived organoid systems therefore represent a promising surrogate platform for future studies on VZV infection biology and antiviral immune responses.

For follow-up clinical research, safety considerations are essential for intranasal adenoviral vaccination. In our preclinical program, we conducted both acute and repeated-dose safety evaluations in SD rats and cynomolgus macaques following IM or IN administration. During the acute safety observation period, no mortality, clinical abnormalities, pathological findings, or adverse effects on body weight or food intake were observed in any animals. In the repeated-dose study, even at high doses up to 4 × 1011 VPs/animal administered intramuscularly to cynomolgus macaques, no systemic toxicity was detected. Only transient and reversible increases in body temperature or C-reactive protein were observed, which were consistent with normal vaccine-induced immune activation. Although detailed toxicology datasets are not included here, the available evidence indicates that ChAdOx1-VZV exhibits a favorable acute safety profile in animal models, supporting the feasibility of further development of both intranasal and intramuscular regimens.