Abstract

This systematic review summarises the literature on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination, including acceptance, uptake, hesitancy, attitude and perceptions among slum and underserved communities. Relevant studies were searched from PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar, following a pre-registered protocol in PROSPERO (CRD42022355101) and PRISMA guidelines. We extracted data, used random-effects models to combine the vaccine acceptance, hesitancy and uptake rates categorically, and performed meta-regression by R software (version 4.2.1). Twenty-four studies with 30,323 participants met the inclusion criteria. The overall prevalence was 58% (95% CI: 49–67%) for vaccine acceptance, 23% (95% CI: 13–39%) for uptake and 29% (95% CI: 18–43%) for hesitancy. Acceptance and uptake were positively associated with various sociodemographic factors, including older age, higher education level, male gender, ethnicity/race (e.g., Whites vs African Americans), more knowledge and a higher level of awareness of vaccines, but some studies reported inconsistent results. Safety and efficacy concerns, low-risk perception, long distance to vaccination centres and unfavourable vaccination schedules were prominent reasons for hesitancy. Moreover, varying levels of attitudes and perceptions regarding COVID-19 vaccination were reported with existing misconceptions and negative beliefs, and these were strong predictors of vaccination. Infodemic management and continuous vaccine education are needed to address existing misconceptions and negative beliefs, and this should target young, less-educated women and ethnic minorities. Considering mobile vaccination units to vaccinate people at home or workplaces would be a useful strategy in addressing access barriers and increasing vaccine uptake.

1. Introduction

Since its emergency in late 2019, the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) remains a prioritised global health concern. As of 22 March 2023, over 682 million cases and 6.8 million deaths have been recorded worldwide [1]. The pandemic has caused profound socio-economic impacts in all countries, which are still evident [2]. This was mainly due to the restrictive measures, such as lockdowns, restricted movement and school closures, among others, adopted by different countries to minimise the rapid spread of the virus [2].

The rollout of COVID-19 vaccination programs contributed to the control of the pandemic and allowed several countries to lift strict control measures [3,4]. As of 18 January 2023, about 69.2% of the global population had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, with over 13.2 billion doses given [5]. However, only 25.9% of people in low-income countries had received at least one dose [5], highlighting inequality in vaccination access and uptake [6]. Low-income countries have reported issues such as global vaccine supply chain dynamics, inaccessibility of vaccination centres and perceived misconceptions about the vaccine as prominent reasons for the low COVID-19 vaccine uptake [7,8,9]. Moreover, vaccine hesitancy, a phenomenon of “delayed acceptance or refusal of safe vaccines despite availability of vaccination services” [10], presents a significant challenge to successful vaccination programs globally, with developed countries inclusive [11]. Vaccine hesitancy is mainly due to various misconceptions, such as perceiving vaccines as unnecessary due to perceived self-immunity, beliefs that vaccines are not safe/effective and religious anti-vaccine beliefs due to conspiracy theories about mortality, among others [11,12,13]. Nonetheless, vaccination remains an indispensable pillar in the road to recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, as embraced and adopted by most countries [5,14].

Slum dwellers and underserved communities are both measures of social and economic deprivation. Slum dwellers are identified as urban households lacking any of the following; adequate water and sanitation, sufficient living space, secure tenure or durable housing, similar to underserved communities, which are populations having limited or no access to resources or are otherwise deprived [15]. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused an inordinate effect among disadvantaged and underserved communities, including urban slum dwellers worldwide. The restrictive control measures enforced, particularly in the early stage of the pandemic, mostly affected the less advantaged urban poor who relied on daily income for survival [16]. In addition, slum-dwellers and underserved communities have a higher vulnerability to COVID-19 infection and morbidity compared to other advantaged or wealthier individuals [17,18]. Moreover, disparities in COVID-19 vaccination have been reported among slum-dwellers and underserved communities due to several barriers, such as long distances to vaccination centres, long queues and lack of time off work to get vaccinated, as well as low vaccine supplies [9,16]. Despite the huge efforts made to expand the COVID-19 vaccination program, successful vaccination targets still cannot be achieved without barriers and concerns faced by slum and underserved communities being addressed. This calls for a clear, in-depth assessment and understanding of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and the unique barriers faced by this vulnerable group.

Several reviews have summarised evidence on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy worldwide [9,11,12,19,20] and region-wise [13,21,22], but with none focusing on slum and underserved communities. Given the increasing number of slums worldwide as a result of rapid urbanisation and other factors [23], special consideration of this population group in vaccination programs is key in preventing the uncontrolled spread of the virus and the emergence of new virus strains [16,17]. In other words, successful control of the COVID-19 pandemic warrants control of the spread in such vulnerable populations, even in developed countries, to protect society. Previous reviews have noted varying rates of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance/hesitancy across countries and regions. In addition, attitudes and perceptions about COVID-19 vaccination have been reported as one of the key determinants of vaccine acceptance since they influence people’s behaviour [21]. These were also considered in this study in the slum/underserved context.

This systematic review was, therefore, conducted to synthesise and summarise the available literature on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance/hesitancy rates, attitudes and perceptions regarding vaccination and the associated factors in slum and underserved communities. This is needed to establish a solid understanding of the levels of COVID-19 acceptance/uptake, as well as barriers and reasons for vaccine hesitancy in this group, which would help to formulate tailored strategies for addressing them. The review was guided by the following research questions:

- (i)

- What is the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, hesitancy and uptake among slum and underserved communities?

- (ii)

- What are the factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy among slum and underserved communities?

- (iii)

- What are the attitudes and perceptions regarding COVID-19 vaccines among slum and underserved communities?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted according to a pre-registered protocol in PROSPERO (CRD42023390993) and the PRISMA guideline [24]. This systematic review considered literature concerning COVID-19 vaccination among slum and underserved communities. Literature was mainly sourced from the following platforms; PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science databases.

2.2. Search Strategy

The study used a comprehensive search using a set of appropriate keywords and MeSH terms to identify studies reporting on COVID-19 vaccination among slum and underserved communities. For consistency and precision, similar keywords were used and searched in the article titles across all search databases. A comprehensive search of published literature was done from each of the four selected databases using the combinations of key terms and Boolean operators (Table 1). These included: “vaccine”, “vaccination”, “immunisation”, “immunisation”, “slum”, “urban poor”, “disadvantaged”, “underserved”, “slum-dwellers”, “informal settlement”, “poor housing”, “perception”, “attitude”, “acceptance”, “acceptability”, “knowledge”, “hesitancy”, “COVID-19”, “Coronavirus” and “SARS-CoV-2”.

Table 1.

Key terms or Boolean operators used for search.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

Only population-based original observational research studies (including qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method studies) reporting on COVID-19 vaccination in slum and/or underserved communities, with no restriction to country/region location, were considered in the full review. Additionally, comparative studies were considered if they included a slum or underserved community as part of their study population. We also considered pre-prints, theses and dissertations with full text available. Only English-language articles published between 1 November 2019 to 19 January 2023 were considered.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

Other grey literature, including government documents/reports, newspapers, textbooks, book chapters and protocols, were excluded. Governmental documents/reports and newspapers were excluded because they might not be written for scientific purposes. Another reason for excluding this grey literature was the lack of peer review. There are, hence, concerns about the quality and reliability of this literature. In addition, intervention studies, laboratory studies, model and framework studies, validation studies and those whose study population was not slum or underserved community were excluded. All disagreements faced in the inclusion phase of the review were discussed to reach a consensus.

2.5. Data Extraction

Title, abstract screening and full-text reviews were independently conducted by two authors (J.K. and S.C.) following the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After the successful screening, the following information/variables were extracted from the selected articles: first author, year of publication, study location, study design, key measurements, study population, sample size, reported acceptance or hesitancy rate, uptake rates, and other relevant findings on attitude, perception, associated factors and barriers as detailed in Table 2. The extracted data were stored in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for statistical analysis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

2.6. Quality Assessment and Data Analysis

The quality of the included articles was assessed using the Mixed-Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018, which has a detailed description of the rating [49]. Two authors independently assessed the quality of the included studies, and in case of discrepancies, a consensus was reached, also through discussion.

First, the characteristics of studies included in the review were summarised using frequencies and percentages. Then, the pooled vaccination acceptance, hesitancy and uptake rates were categorically obtained using random-effects models and sub-grouped according to study characteristics. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Q-test and test. For studies that reported only the acceptance rate, the hesitancy rate was calculated by the formula (100-acceptance rate), similar to studies that reported the hesitancy rate only where the acceptance rate was obtained by the formula (100-hesitancy rate).

Meta-regression analyses and subgroup analyses were conducted to determine whether study characteristics could explain variability across studies. This included study year (2020, 2021, and 2023, as this was related to vaccine availability), region (Africa, Americas and Asia; related to vaccination policies adopted by different countries), sample size (<1000 and >1000) and study population (general and non-general-this included parents, hospital patients and healthcare workers). Only study variables with meaningful and practical categories were considered. We assessed whether vaccination acceptance, hesitance and uptake varied according to the selected study variables by univariate meta-regression. Significant variables (p < 0.05) were then included in the multivariable meta-regression model.

In addition, sensitivity analysis was done by considering only studies with good methodological quality and studies published before and after the median publication year. The presence of publication bias was visualised by funnel plots to measure the asymmetry and quantitatively examined with Egger’s linear regression test. We used the trim-and-fill method to adjust for potential publication bias. The meta-analyses were done using the meta-prop package (method = Inverse and summary measure = PLOGIT) of R Studio (version 4.2.1). In addition, other key findings on attitudes and perceptions, as well as associated factors and reasons for vaccine hesitancy, were assessed and summarised thematically.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Search Results

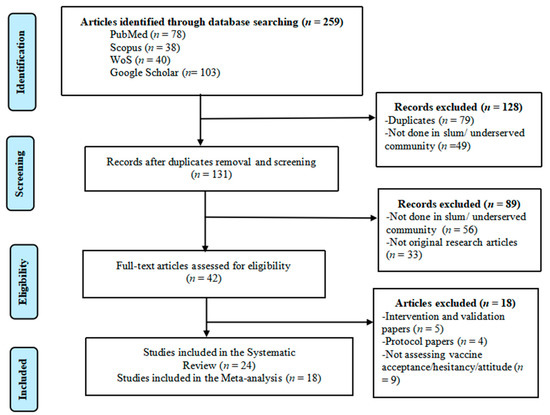

The PRISMA diagram (Figure 1) illustrates the selection process and shows the reasons for exclusion. A total of 259 articles were identified from the initial search, and 131 remained after removing duplicates and title screening. On further screening, 42 articles remained for eligibility assessment after excluding those which were not original studies and not done in slum/underserved communities. The final assessment yielded 24 articles for further analysis [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing search strategy and study selection process.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

The twenty-four (24) included studies were published between 2021–2023, with nine articles published in 2021, 14 in 2022 and one in 2023. Eleven (11) studies were conducted in Asia, nine in North America, three in Africa, and one in South America. The studies represent seven countries, with nine from the USA, five from Bangladesh and four from India. Other countries included Pakistan (2 studies), Uganda (2), Brazil (1), and Kenya (1).

Nineteen (19) of the studies were quantitative, three were qualitative, and two were mixed methods. The studies included in this review comprised 30,323 participants with a sample size ranging from 34 to 12,887 (mean = 1263.5, SD = 2610.3). Regarding the study population, the majority (21 studies) were from the general slum/ underserved population, and the rest were from hospital patients, healthcare workers and parents (one study each) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, hesitancy and uptake from the included studies.

The overall quality of the studies was generally good, implying that the included studies satisfied most of the quality criteria. However, lower scores in item 4 (non-response bias-45.5%) were noted among most quantitative studies, as detailed in Supplementary Table S1A,B.

3.3. Primary Findings

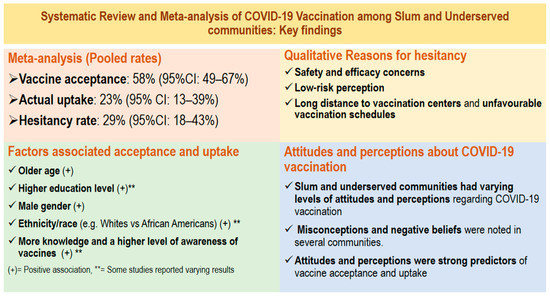

The overall findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis are summarised in Figure 2. Detailed findings of vaccine acceptance, hesitancy and uptake are in Figure 3, associated factors and reasons for vaccine hesitancy in Table 4, and attitudes and perceptions are detailed in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Main findings from the Systematic Review and meta-analysis of COVID-19 vaccination among slum and underserved communities.

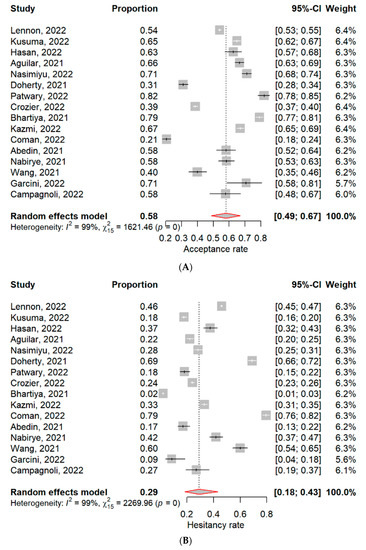

Figure 3.

Forest plots for pooled (A) Acceptance rate, (B) Hesitancy rate and (C) Uptake rate of COVID-19 vaccine among slum and underserved communities [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48].

Table 4.

Moderators of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, hesitancy and uptake rates (meta-regression and subgroup analyses).

3.3.1. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy

Sixteen (16) studies reported on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy (Figure 3A,B). The overall acceptance was 58% (95% CI: 49–67%), ranging from 21% to 82.0%, and with very high significant heterogeneity (I2 = 99%, p < 0.01), Figure 3A. The overall vaccine hesitancy was 29% (95% CI: 18–43%), ranging from 2% to 79%, also with very high heterogeneity (I2 = 99%, p < 0.01), Figure 3B. The highest vaccine hesitancy was reported in the USA, with a pooled prevalence of 45%, followed by Uganda (42%) and Pakistan (33%). However, vaccine acceptance increased from 2021 (56%) to 2022 (59%), opposite to vaccine hesitancy which declined from 35% to 32% in the same period (2021–2022). Vaccine acceptance was highest among healthcare workers (71%), followed by parents (67%) and hospital patients (58%).

Meta-regression and subgroup analyses were done to see whether study year, region, study population, and sample size could explain the observed heterogeneity among acceptance and hesitancy studies. Univariate meta-regression showed that vaccine acceptance was positively associated with region and study population (p = 0.01 and <0.01), but vaccine hesitancy had a negative association with the two variables (both p = 0.01). After multivariate meta-regression, only vaccine acceptance was positively associated with the study population (p = 0.03) (Table 4).

In subgroup analyses, only the study population explained some of the variability among acceptance studies, with no significant heterogeneity among non-general population studies (three studies). Moreover, Asia and Africa had higher vaccine acceptance rates than the Americas (70% and 65% vs 47%), similar to non-general population studies compared to general population studies (65% vs 56%). Contrariwise, the Americas had higher vaccine hesitancy than Africa and Asia (40% vs 35% and 17%), similar to general population studies compared to non-general population studies (32% vs 19%) (Table 4).

Sensitivity analyses by considering only studies done before and after the median year (six studies) showed lower acceptance (56%, 95% CI: 41–70%) and hesitancy (27%, 95% CI: 9–59%) rates, both with high heterogeneity (both I2 = 99%, p < 0.01). In addition, considering only studies with good quality (14 studies, after removing two studies [38,40]) gave higher acceptance (59%, 95% CI: 51–67%) and hesitancy (31%, 95% CI: 22–40%) rates, both with significant heterogeneity (both I2 = 99%, p < 0.01).

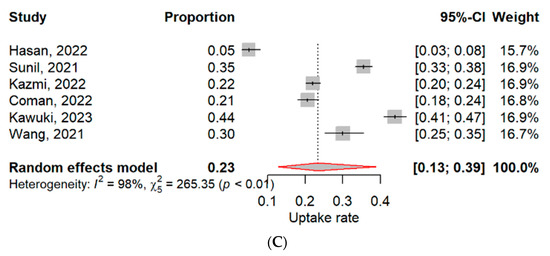

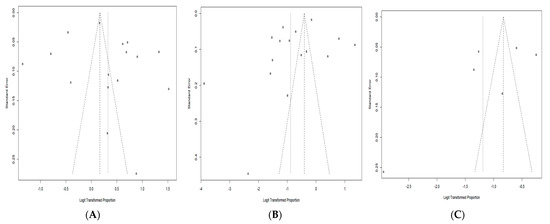

Publication bias was assessed in the acceptance and hesitancy articles using visual inspection of the funnel plot, which showed a slight asymmetry in the studies, implying probable publication bias toward studies with low acceptance rates and high hesitancy rates (Figure 4A,B). However, further evaluation using Egger’s test showed no significant publication bias in acceptance and hesitancy studies (p = 0.504 and 0.209). Nevertheless, when the trim-and-fill analyses were executed, the adjusted acceptance and hesitancy rates were 52.6% (95% CI: 42.8–62.2 %) and 42.1% (95% CI: 27.1–58.7) after filling in three and five missing studies, respectively.

Figure 4.

Funnel plots of (A) Acceptance studies (Egger’s test, p = 0.504), (B) Hesitancy studies (Egger’s test, p = 0.209) and (C) Uptake studies (Egger’s test, p = 0.291).

3.3.2. COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake

Six (6) studies reported on the actual uptake/receipt of the COVID-19 vaccine among slum and underserved communities (Figure 3C). The overall uptake was 23% (95% CI: 13–39%), ranging from 5% to 44%, and with very high significant heterogeneity (I2 = 98%, p < 0.01). Uganda reported the highest vaccine uptake (44%), followed by India (35%) and the USA (25%). Vaccine uptake was lowest in Bangladesh (5%). Uptake rates increased from 2021 (33%) to 2023 (44%).

Univariate meta-regression revealed that vaccine uptake was positively associated with the study year (p < 0.01) but negatively associated with the region (p < 0.01). On multivariate meta-regression, vaccine uptake was only significantly associated with study year but with a negative association (p = 0.04), Table 4.

Subgroup analyses showed that only the study year explained some of the variability among vaccine uptake studies, with no significant heterogeneity among 2021 studies (2 studies). Additionally, 2021 studies reported higher vaccine uptake compared to 2022 studies (33% vs 14%), similar to studies from the Americas compared to Asian studies (25% vs 17%), Table 4.

Sensitivity analyses by considering only vaccine uptake studies done before and after the median year (three studies) showed a higher uptake rate of 37% (95% CI: 29–45%), with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 93%, p < 0.01). However, considering only studies with good quality (four studies, after removing two studies [29,40]) gave a slightly lower uptake rate of 21% (95% CI: 8–45%), also with significantly high heterogeneity (I2 = 99%, p < 0.01).

Publication bias among vaccine uptake articles was also assessed using visual inspection of the funnel plot, which showed a slight asymmetry in the studies, implying probable publication bias toward studies with higher uptake rates (Figure 4C). Further evaluation by Egger’s test found no significant publication bias among uptake studies (p = 0.291). Nevertheless, when the trim-and-fill analysis was executed, the adjusted uptake rate was 30.1% (95% CI: 14.4–52.3%) after filling in one missing study.

3.3.3. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccination

Seventeen (17) studies reported on the factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination (acceptance/hesitancy and uptake), Table 5. Older age was a strong predictor reported in nine studies, with some reporting a positive association with acceptance and uptake [28,30,35,38,41,42,47] and a negative association in others [27,29]. High education level and good health literacy were also positive correlates of vaccine acceptance and uptake [25,29,37,39,42], though some studies reported a negative association [32,38]. Male gender had a positive association with vaccine acceptance in five studies [25,29,33,35,38]. Ethnicity/race was a strong predictor in the USA and reported in five studies, with more vaccine hesitancy among ethnic minorities, mostly among Blacks and Hispanics [25,33,35,45,47]. Ethnicity/tribe was also a strong predictor in Uganda [41]. Being employed and having higher SES had a positive association with acceptance and uptake [29,39], while occupation had a varying effect on vaccination [29,37,38,42]. Good knowledge and awareness of the vaccines as well as reliable information sources, were strong positive associates of vaccine acceptance and uptake [28,34,37,41]. Perceived benefit of vaccination, high perceived susceptibility and severity of COVID-19, and self-efficacy to receive vaccination were also strong positive predictors of vaccine acceptance and uptake [27,30,34,39,41,48], same as cues to action in the forms of text messages and reminders for people to get vaccinated [41,48]. However, perceived barriers such as serious side effects and safety concerns of the vaccines and long distances to vaccination centres were associated with higher vaccine hesitancy, same as negative attitudes, beliefs and perceptions about the vaccine, for example, anti-vaccine attitudes and religious beliefs against vaccination [28,33,34,37,39,41,48]. Trust and confidence in the vaccine, healthcare workers and the government were also reported in several studies as strong positive predictors [33,34,42,47,48]. Other reported factors with a positive association included urban residence [25,35], COVID-19 infection and test history, and vaccination of other family members [39,45]. Having chronic diseases [28,42] and being religious [29,41] showed varying effects on vaccination.

Table 5.

Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination and reasons for hesitancy.

3.3.4. Qualitative Reasons for COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy

Nine (9) studies reported on possible reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among slum and underserved communities (Table 5). Concerns about vaccine safety, possible side effects and efficacy/effectiveness of vaccines were the most reported reasons (eight studies) for not getting vaccinated [29,30,31,32,33,36,46,47]. The low-risk perception was also a common reason reported in three studies [27,30,32], same as negative beliefs, attitudes and misconceptions about COVID-19 vaccines [27,32,46]. In addition, long distances to vaccination centres, inability to spare a day from work and missed opportunity [36,47], limited information on vaccination [32,46], and mistrust of healthcare workers, government and manufacturers [33,46,47] were also reported reasons for hesitancy.

3.3.5. Attitudes and Perceptions about COVID-19 Vaccination

Eleven (11) studies reported on attitudes and perceptions regarding COVID-19 vaccination (Table 2). Varying levels of knowledge and awareness of COVID-19 vaccination have been reported among the included studies. Higher awareness of COVID-19 vaccination (over 60%) was reported in Kenya but with rates higher in Asembo than in Kibera slums [32]. However, lower rates of knowledge and awareness (less than 10%) were reported in India (Mumbai) [38] and Uganda [43]. Knowledge and awareness of vaccination were associated with age, gender, marital status, education, income, occupation, and socioeconomic status [26,37,38,43].

Regarding attitudes and perceptions, COVID-19 vaccines were perceived as safe, effective and important by the majority in underserved communities of the USA [31], similar to Ugandan and Bangladeshi slum communities [43,45]. However, a lack of trust in vaccines and doubt of vaccines’ safety and effectiveness were reported in India and Bangladesh [36,44]. In Ugandan slum communities, the fear of being unable to access services in the future due to being unvaccinated was the dominant motivation for vaccination [43], while in Bangladesh, acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine among slum residents improved with time after seeing more and more community members getting vaccinated and knowing that vaccination was free of cost [26]. Slum and underserved communities had the lowest acceptance and uptake rates compared to other residences [42] due to structural inequities in the vaccination that affected access to COVID-19 vaccination, and, thus, the majority preferred decentralised local vaccine camps to receive vaccines rather than going to central vaccination centres [26,28,46]. In the USA, residents of underserved communities believe that ensuring good knowledge and access to reliable information, providing bilingual staff to administer the vaccine, and giving an option for mobile/home vaccination would facilitate vaccine uptake [46].

Attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination was associated with religious beliefs and cultural norms, ethnicity/race, education level, income, cues from social ties, and clinical, trust, and religious/spiritual barriers [37,40], while perception was associated with age, gender, education, marital status, and family size [44].

4. Discussion

4.1. Primary Findings

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to summarise evidence on COVID-19 vaccination among slum and underserved communities. The review first analysed the vaccine acceptance, hesitancy and uptake rates. Then it assessed factors associated with vaccination and reasons for hesitancy. It additionally assessed attitudes and perceptions of COVID-19 vaccination among this vulnerable population. All these are strong contributions to literature. Moreover, in addition to the multi-dimensional and comprehensive approach, we used a reproducible search with a well-established keyword system for the identification of studies from key databases, all of which were strengths of this systematic review.

The review found that vaccine acceptance was 58% (95% CI: 49–66%), hesitancy 29% (95% CI: 18–43%) and uptake 23% (95% CI: 13–39%). Vaccine acceptance and uptake were associated with various sociodemographics, including age, education level, gender, and ethnicity, among others. Moreover, safety and efficacy concerns, low-risk perception and long distance to vaccination centres were the main reasons for hesitancy. Results also indicate varying levels of attitudes and perceptions regarding COVID-19 vaccination, with misconceptions and negative attitudes reported among slum and underserved communities. With these findings, the review comprehensively addressed the research questions.

The review showed that although 58% of residents of slum and underserved communities were willing to take up the COVID-19 vaccine, only 23% had actually received the vaccine. The observed uptake rate in this study is much lower than the current global vaccination rate of 69% [5], which is probably due to the various structural barriers to vaccine access in slums and underserved communities [9]. Moreover, although results indicated an increase in acceptance rates since the vaccine rollout, hesitancy in these less advantaged communities (29%) is still substantially high, although similar to previous studies elsewhere [21]. Notably, the highest vaccine hesitancy was reported in underserved communities of the USA (45%), which is similar and consistent with findings of previous reviews [9,11,21].

The review results also indicate that COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, hesitancy, and uptake significantly varied according to region, study population, and study year. The region had a varying effect on vaccine acceptance, hesitancy and uptake, with more acceptance rates reported in Asia and Africa compared to the Americas. However, the Americas had higher vaccine uptake compared to Asia. The findings may be explained by the different vaccination policies in various countries, for example, mandatory vaccination, travel restrictions and lockdowns [3,4]. These various policies could indirectly affect people’s perceptions and attitudes toward vaccines in that particular region or country [12,20], thus, the observed trend among the analysed studies.

The study population also had a varying effect on vaccine acceptance and hesitancy, with studies done among parents, hospital patients and healthcare workers reporting more vaccine acceptance compared to general population studies. Various population groups tend to have varying perceived susceptibility to COVID-19, which could affect their acceptance and hesitancy of the COVID-19 vaccine [10,13,16], thus, the observed trend.

Furthermore, study year positively affected vaccine uptake, with most recent studies (done in 2023) reporting higher uptake rates compared to early studies. Vaccine availability, which was introduced around early 2021 and became more accessible in later stages of the pandemic [5,8], might explain the observed trend. Moreover, the varying COVID-19 situation (i.e., changes in new confirmed cases and deaths over time) and the prevalent virus subtype (such as Delta and Omicron, among others), which present with varying infectivity and severity [1] may also influence people’s willingness to get vaccinated.

The review highlighted several barriers which might explain the observed low uptake and high hesitancy rates. The most common reasons for vaccine hesitancy among these communities include safety and efficacy concerns, low-risk perception, long distance to vaccination centres and unfavourable vaccination schedules. Such barriers have also been reported in other non-slum communities [11,13,22] and, thus, should be considered and addressed with a customised approach for successful vaccination programs. Infodemic management, risk communication and continued vaccine education to clear safety concerns are, thus, warranted. Moreover, considering flexible vaccination options such as mobile vaccination units where people can be vaccinated at their homes or workplace would solve access barriers faced among slum and underserved communities [46,50].

The study highlighted several factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination among the study population. These included personal (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, attitude and perceptions), interpersonal (e.g., employment, occupation, SES, household size, cues to action) and structural (e.g., knowledge, information sources, distance to vaccination centres, beliefs, religion) factors. These determinants have also been reported among non-slum communities in previous reviews [12,13,20,21,22]. The most common determinants in our study were age, education level, gender, ethnicity/race, and knowledge and awareness of vaccines, among others. For successful vaccination programs in these communities, such sociodemographic factors should be considered and incorporated when designing targeted interventions. Current and future vaccine education initiatives should, thus, target young, less-educated women and ethnic minorities.

Study results also indicate that residents of slum and underserved communities had varying levels of attitudes and perceptions regarding COVID-19 vaccination, with misconceptions and negative beliefs noted in several communities. Notably, attitudes and perceptions were strong predictors of vaccine acceptance and uptake in this study. To reduce the hesitancy rates, vaccine education programs should, thus, be tailored to address existing misconceptions and negative beliefs about COVID-19 vaccines while leveraging positive attitudes and perceptions.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

This systematic review has some limitations. The estimated vaccine acceptance, hesitancy, and uptake rates could have been affected by the persistent heterogeneity. Although we performed subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis, the observed heterogeneity could not be fully addressed/explained. However, it should be noted that these studies were from different countries with varying COVID-19 situations and vaccination policies and used different data collection methods, making heterogeneity unavoidable. The small number of uptake studies could have affected the true estimation of the effect size and meta-regression results. Although we used a comprehensive keyword search strategy, some relevant studies might still have been missed out since only articles in the English language were considered. Additionally, we only considered studies from slum and underserved communities, and studies that used rural population without specifying that it is underserved were not considered. Future studies are needed to summarise evidence on COVID-19 vaccination, specifically in rural areas. Due to the self-report nature of the studies used in this review, there is a risk of recall and social-desirability bias. No studies were identified from developed countries apart from the USA, although we used a systematic search using PRISMA guidelines. Future studies should, thus, focus on other developed countries to explore vaccination uptake among their underserved and slum communities. Despite the limitations, the study provides valuable insights into COVID-19 vaccination, associated factors, and barriers among slum and underserved communities.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review, to our knowledge, provides the first summarised evidence on COVID-19 vaccination, including attitudes and perceptions, associated factors, and barriers among slum and underserved communities. The findings indicate that although more than half of residents in slum and underserved communities were willing to take the vaccine, only a third had been vaccinated. Therefore, there is a need for continuous vaccine education and infodemic management to address existing misconceptions and negative beliefs. Such education programs should focus on the young, less educated, women, and ethnic minorities. Addressing access barriers, for example, by availing mobile vaccination units to vaccinate people at home or workplaces, would increase vaccine uptake among those willing to be vaccinated.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/vaccines11050886/s1, Supplementary Table S1: Quality assessment of included studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: J.K. and Z.W.; methodology and analysis: J.K. and Z.W.; Formal analysis: J.K., Z.W., Y.F. and S.C.; visualisation: J.K. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation: J.K., Z.W., P.S.-f.C., S.C. and X.L.; Writing-review and editing: Y.F., P.S.-f.C., S.C. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by internal funding from the Centre for Health Behaviours Research, the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting this systematic review are available in the reference section. In addition, the analysed data used in this systematic review are available from the author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Worldometer. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. 2022. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Onyeaka, H.; Anumudu, C.K.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Egele-Godswill, E.; Mbaegbu, P. COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 00368504211019854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Jin, H.; Xiang, H.; Wang, N. Optimal lockdown policy for vaccination during COVID-19 pandemic. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 45, 102123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kansakar, S.; Dumre, S.P.; Raut, A.; Huy, N.T. From lockdown to vaccines: Challenges and response in Nepal during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 694–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Our World in Data. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations. 2022. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Tatar, M.; Shoorekchali, J.M.; Faraji, M.R.; Wilson, F.A. International COVID-19 vaccine inequality amid the pandemic: Perpetuating a global crisis? J. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 03086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabagenyi, A.; Wasswa, R.; Nannyonga, B.K.; Nyachwo, E.B.; Kagirita, A.; Nabirye, J.; Atuhaire, L.; Waiswa, P. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Uganda: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 6837–6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noushad, M.; Al-Awar, M.S.; Al-Saqqaf, I.S.; Nassani, M.Z.; Alrubaiee, G.G.; Rastam, S. Lack of access to COVID-19 vaccines could be a greater threat than vaccine hesitancy in low-income and conflict nations: The case of Yemen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 1827–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Tu, P.; Beitsch, L.M. Confidence and receptivity for COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review. Vaccines 2020, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aw, J.; Seng, J.J.; Seah, S.S.; Low, L.L. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy—A scoping review of literature in high-income countries. Vaccines 2021, 9, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.R.; Alzubaidi, M.S.; Shah, U.; Abd-Alrazaq, A.A.; Shah, Z. A scoping review to find out worldwide COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its underlying determinants. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackah, B.B.; Woo, M.; Stallwood, L.; Fazal, Z.A.; Okpani, A.; Ukah, U.V.; Adu, P.A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Africa: A scoping review. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2022, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Re, V.L.; Klungel, O.H.; Chan, K.A.; Panozzo, C.A.; Zhou, W.; Winterstein, A.G. Global COVID-19 vaccine rollout and safety surveillance—How to keep pace. BMJ 2021, 373, n1416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Estimating Global Slum Dwellers: Monitoring the Millennium Development Goal 7, Target 11. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/accsub/2002docs/mdg-habitat.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Lines, K.; Sebbanja, J.A.; Dzimadzi, S.; Mitlin, D.; Mudimu-Matsangaise, P.; Rao, V.; Zidana, H. COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout: Challenges and Insights from Informal Settlements. IDS Bull. 2022, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, C.E.; Inbaraj, L.R.; Chandrasingh, S.; De Witte, L.P. High seroprevalence of COVID-19 infection in a large slum in South India; what does it tell us about managing a pandemic and beyond? Epidemiol. Infect. 2021, 149, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malani, A.; Shah, D.; Kang, G.; Lobo, G.N.; Shastri, J.; Mohanan, M.; Jain, R.; Agrawal, S.; Juneja, S.; Imad, S.; et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in slums versus non-slums in Mumbai, India. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e110–e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: A concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, C. Global predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A systematic review. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbu, Y.B.; Gautam, R.K.; Pham, L. The Health Belief Model Applied to COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2022, 10, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwary, M.M.; Alam, M.A.; Bardhan, M.; Disha, A.S.; Haque, M.Z.; Billah, S.M.; Kabir, M.P.; Browning, M.H.; Rahman, M.M.; Parsa, A.D.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Low-and Lower-Middle-Income Countries: A Rapid Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2022, 10, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker-Buque, T.; Mindra, G.; Duncan, R.; Mounier-Jack, S. Immunization, urbanization and slums–a systematic review of factors and interventions. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, R.P.; Block, R., Jr.; Schneider, E.C.; Zephrin, L.; Shah, A.; Collaborative, T.A.; 2021 COVID Group. Underserved population acceptance of combination influenza-COVID-19 booster vaccines. Vaccine 2022, 40, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, W.; Manzoor, F.; Farnaz, N.; Aktar, B.; Rashid, S.F. Perception and attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination among urban slum dwellers in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, Y.S.; Kant, S. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and its determinants: A cross-sectional study among the socioeconomically disadvantaged communities living in Delhi, India. Vaccine: X 2022, 11, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, M.M.; Rasel, R.I.; Sultana, F. Exploring the Prevalence and Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among the Urban Slum Dwellers of Bangladesh: A Cross-Sectional Study. NAAR 2022, 5, 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Sunil, K.; Srividya, J.; Patel, A.E.; Vidya, R. COVID-19 vaccination coverage and break through infections in urban slums of Bengaluru, India: A cross sectional study. Eur. J. Health Res. 2021, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar Ticona, J.P.; Nery, N., Jr.; Victoriano, R.; Fofana, M.O.; Ribeiro, G.S.; Giorgi, E.; Reis, M.G.; Ko, A.I.; Costa, F. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine among residents of slum settlements. Vaccines 2021, 9, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohrs, J.R.; Mirtallo, J.M.; Seifert, J.L.; Jones, S.M.; Erdmann, A.M.; Li, J. Perceptions and barriers to the annual influenza vaccine compared with the coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine in an urban underserved population. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasimiyu, C.; Audi, A.; Oduor, C.; Ombok, C.; Oketch, D.; Aol, G.; Ouma, A.; Osoro, E.; Ngere, I.; Njoroge, R.; et al. COVID-19 Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices and Vaccine Acceptability in Rural Western Kenya and an Urban Informal Settlement in Nairobi, Kenya: A Cross-Sectional Survey. COVID 2022, 2, 1491–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, I.A.; Pilkington, W.; Brown, L.; Billings, V.; Hoffler, U.; Paulin, L.; Kimbro, K.S.; Baker, B.; Zhang, T.; Locklear, T.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in underserved communities of North Carolina. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwary, M.M.; Bardhan, M.; Al Imran, S.; Hasan, M.; Tuhi, F.I.; Rahim, S.J.; Newaz, M.N.; Hasan, M.; Haque, M.Z.; Disha, A.S.; et al. Psychological determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among urban slum dwellers of Bangladesh. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 958445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, J.; Christensen, N.; Li, P.; Stanley, G.; Clark, D.S.; Selleck, C. Rural, underserved, and minority populations’ perceptions of COVID-19 information, testing, and vaccination: Report from a southern state. Popul. Health Manag. 2022, 25, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamysetty, S.; Babu, G.R.; Sahu, B.; Shapeti, S.; Ravi, D.; Lobo, E.; Varughese, C.S.; Bhide, A.; Madhale, A.; Manyal, M.; et al. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence: Findings from Slums of Four Major Metro Cities of India. Vaccines 2021, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, R.; Shah, H.; Sultan, A.; Yaqoob, M.; Haroon, R.; Mistry, S.K.; Bestman, A.; Yousafzai, M.T.; Yadav, U.N. Exploring the beliefs and experiences with regard to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance in a slum of Karachi, Pakistan. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 37, daac140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhartiya, S.; Kumar, N.; Singh, T.; Murugan, S.; Rajavel, S.; Wadhwani, M. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards COVID-19 vaccination acceptance in West India. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2021, 8, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, T.; Abdullah, M.; Khan, A.A.; Safdar, R.M.; Afzal, S.; Khan, A. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance in underserved urban areas of Islamabad and Rawalpindi: Results from a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coman, I.A.; Xu, S.; Yamamoto, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: Disadvantaged Groups’ Experience with Perceived Barriers, Cues to Action, and Attitudes. Am. J. Health Promot. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawuki, J.; Nambooze, J.; Chan, P.S.; Chen, S.; Liang, X.; Mo, P.K.; Wang, Z. Differential COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake and Associated Factors among the Slum and Estate Communities in Uganda: A Cross-Sectional Population-Based Survey. Vaccines 2023, 11, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedin, M.; Islam, M.A.; Rahman, F.N.; Reza, H.M.; Hossain, M.Z.; Hossain, M.A.; Arefin, A.; Hossain, A. Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 among Bangladeshi adults: Understanding the strategies to optimize vaccination coverage. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabirye, H.; Muwanguzi, M.; Onenchan, J. Assessing Knowledge and Perceptions towards the COVID-19 Vaccine among the Community of Kalerwe-Besina Slum. Ph.D. Thesis, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mamun, M.; Fatima, K. Slum Dwellers’ perception about COVID-19: A Study in Dhaka Metropolis Slums. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 21, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.X.; Bell-Rogers, N.; Dillard, D.; Harrington, M.A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Delaware’s underserved communities. Del. J. Public Health 2021, 7, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcini, L.M.; Ambriz, A.M.; Vázquez, A.L.; Abraham, C.; Sarabu, V.; Abraham, C.; Lucas-Marinelli, A.K.; Lill, S.; Tsevat, J. Vaccination for COVID-19 among historically underserved Latino communities in the United States: Perspectives of community health workers. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campagnoli, T.; Mohan, G.; Taddese, N.; Santhiraj, Y.; Margeta, N.; Alvi, S.; Jabbar, U.; Bobba, A.; Alharash, J.; Hoffman, M.J. Missed Opportunity: The Unseen Driver for Low Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination Rates in Underserved Patients. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, R.; Nguyen, E.; Wright, M.; Holmes, J.; Oliphant, C.; Cleveland, K.; Nies, M.A. Factors contributing to vaccine hesitancy and reduced vaccine confidence in rural underserved populations. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Ahmad, T.; Kazmi, T.; Sultan, F.; Afzal, S.; Safdar, R.M.; Khan, A.A. Community engagement to increase vaccine uptake: Quasi-experimental evidence from Islamabad and Rawalpindi, Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).