Abstract

The transcription factor Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 (NRF2) governs cellular redox homeostasis and serves as a primary defense mechanism against oxidative stress-driven cardiac remodeling. Beyond basal antioxidant effects, NRF2 coordinates a broad defensive network that preserves mitochondrial bioenergetics, maintains proteostasis, and inhibits regulated cell death pathways, including necroptosis and ferroptosis. Despite robust efficacy in preclinical models, translating these findings to the clinic remains challenging. This review examines the molecular structure of the NRF2-KEAP1 axis, synthesizing evidence regarding its efficacy in ischemia–reperfusion injury and diabetic cardiomyopathy, while assessing the mechanisms of pathway repression and the liabilities of indiscriminate activation. We further review different pharmacological strategies, contrasting the clinical limitations of electrophiles with the potential of protein–protein interaction inhibitors. Finally, we discuss innovations such as cardiac-targeted delivery and biomarker-guided stratification, critically assessing whether these approaches can overcome safety barriers and emphasizing that rigorous validation is essential for clinical viability.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of global mortality, with heart failure (HF) representing its terminal common pathway. Despite the expansion of guideline-directed medical therapies, the prevalence of HF, particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), continues to rise [1,2]. The progression to HF is driven by pathological cardiac remodeling, a maladaptive process characterized by cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, fibroblast activation, and interstitial fibrosis. These structural and functional alterations compromise myocardial mechanics and metabolic flexibility, ultimately leading to pump failure [3].

The myocardium, characterized by its high metabolic demand and limited regenerative capacity, is uniquely dependent on strict redox homeostasis. Unlike the liver, the heart possesses relatively low constitutive antioxidant reserves, making it disproportionately susceptible to redox perturbations. Physiologically, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) act as essential second messengers, modulating protein function via reversible post-translational modification of thiol groups on key signaling molecules involved in excitation-contraction coupling and autophagy [4,5]. However, in disease states, the precision of this signaling network is compromised. The transition to oxidative stress is not simply an excess of ROS, but a disruption of spatial and temporal signaling specificity [6]. In this state, ROS cause macromolecular damage and activate pathological signaling cascades that promote cardiac dysfunction. In the failing heart, oxidative stress is sustained by crosstalk between multiple ROS sources. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a primary driver, generating ROS via mechanisms such as reverse electron transport (RET), particularly under conditions of substrate overload [7]. Simultaneously, neurohormonal and biomechanical stressors upregulate nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase isoforms (NOX2 and NOX4), which interact with mitochondria to perpetuate ROS production [8]. Additionally, the depletion of the cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) leads to the uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), shifting its enzymatic function to produce superoxide instead of nitric oxide (NO) [9]. These interactions establish a feed-forward mechanism of ROS-induced ROS release, maintaining a pro-oxidant state.

Critically, oxidative stress does not act in isolation but serves as a proximal trigger that precipitates a cascade of downstream deleterious events, linking redox dysregulation to inflammation, cell death, and fibrosis. In terms of inflammatory coupling, excessive ROS promotes the leakage of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) into the cytosol, which functions as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) to activate the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling, thereby fueling sterile inflammation [10]. Concurrently, mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) overload initiates lethal signaling cascades by triggering the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) and subsequent cytochrome c release, driving both intrinsic apoptotic and necroptotic pathways [11,12]. In the cardiac interstitium, redox imbalance exacerbates structural remodeling by promoting myofibroblast differentiation via the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β)/Smad axis and activating matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that degrade the extracellular matrix [13]. Therefore, the therapeutic rationale for targeting antioxidant systems extends beyond simple radical scavenging, it represents a strategy to sever the upstream link between redox dysregulation and this broad spectrum of maladaptive processes.

The primary cellular defense against such proteotoxic and oxidative insults is the NRF2 pathway [14]. Under basal conditions, NRF2 is sequestered and targeted for ubiquitin-mediated degradation by Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1). Upon exposure to electrophilic or oxidative stress, cysteines within KEAP1 are modified, halting degradation and allowing NRF2 to translocate to the nucleus. There, it binds the antioxidant response element (ARE) to drive a cytoprotective gene network. Significantly, NRF2 is not solely an antioxidant transcription factor but serves as a master regulator of cellular homeostasis. It coordinates a comprehensive program governing xenobiotic detoxification, proteostasis via autophagy and proteasome subunits, mitochondrial biogenesis, and metabolic reprogramming, including NADPH generation [15]. Thus, the NRF2-KEAP1 axis functions as a central integration hub for stress signals, influencing cell survival and the trajectory of remodeling. This review evaluates the roles of NRF2 in cardiovascular pathophysiology, dissecting its regulatory network and discussing the context-dependent challenges of targeting this pathway in heart disease.

2. The NRF2-KEAP1 Axis

2.1. Molecular Structure and Regulatory Mechanisms

2.1.1. NRF2-KEAP1 Molecular Structure

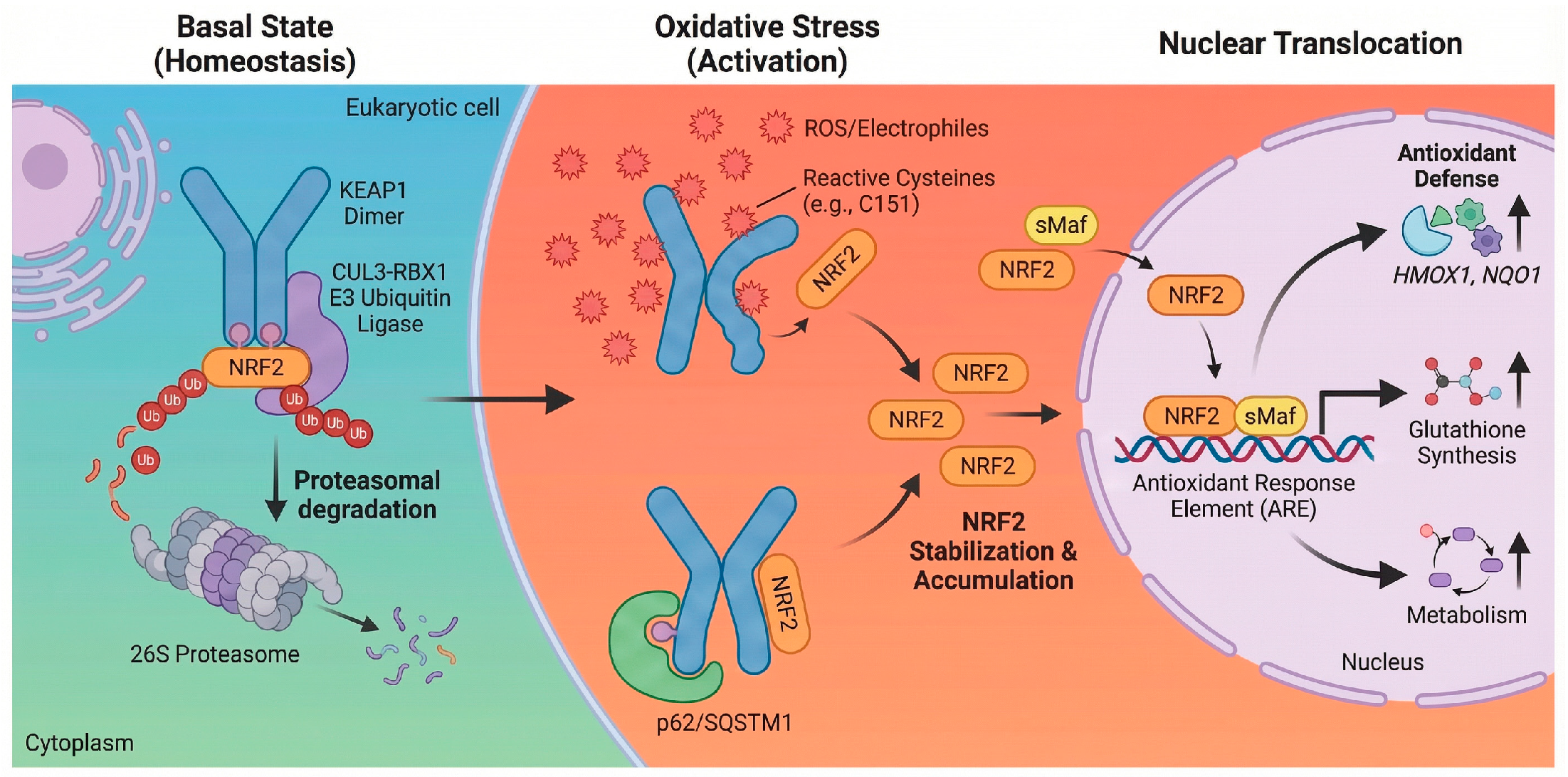

Under homeostatic conditions, the NRF2 transcription factor exhibits a high turnover rate, a feature critical for its rapid inducibility. This dynamic instability is orchestrated by its direct repressor, KEAP1, which functions as a substrate adaptor for a Cullin 3 (CUL3)-RING-box 1 (RBX1) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [16]. Structurally, the regulation relies on the N-terminal Neh2 domain of NRF2, which contains two distinct binding motifs known as the high-affinity ETGE motif and the lower-affinity DLG motif. These motifs engage the Kelch domains of the KEAP1 homodimer in a coordinated hinge-and-latch mechanism. This configuration optimally positions NRF2 for polyubiquitination at specific lysine residues within the Neh2 domain, thereby targeting it for degradation by the 26S proteasome. Consequently, this continuous cycle maintains NRF2 at low basal levels, ensuring the system remains poised for immediate activation upon stress exposure [17].

2.1.2. Stress Induced Activation

KEAP1 acts as a critical intracellular redox sensor containing multiple highly reactive sentinel cysteine residues, such as C151, C273, and C288 in the human protein [18]. Covalent modification of these thiols by oxidants or electrophiles triggers a conformational change in the KEAP1 homodimer, disrupting the lower-affinity latch interaction formed by the DLG motif. This structural alteration compromises the ability of the E3 ligase complex to ubiquitinate NRF2, allowing newly synthesized NRF2 to escape degradation, accumulate in the cytoplasm, and translocate to the nucleus [19]. However, this classic activation represents only one facet of a broader regulatory network. Crucial layers of fine-tuning are provided by classic pathways, such as selective autophagy mediated by the autophagy receptor p62/SQSTM1. This protein can target KEAP1 for degradation, thereby liberating NRF2 and creating a powerful positive feedback loop since p62 is itself a prominent NRF2 target gene [20]. Furthermore, post-translational modifications by various protein kinases, including protein kinase C (PKC), glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK-3β), and protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), can phosphorylate NRF2 or KEAP1 to modulate stability and nuclear localization. Recent evidence also points to the formation of stress induced liquid–liquid phase separated (LLPS) condensates containing p62 and KEAP1, suggesting that regulation occurs within specialized, dynamic subcellular compartments [21]. This multimodal regulation allows the cell to integrate diverse stress signals beyond simple redox changes.

2.1.3. Transcriptional Targets

Once in the nucleus, NRF2 forms obligate heterodimers with small Maf (sMaf) proteins such as MafG and MafK. This dimerization is essential for high-affinity binding to the cis-acting regulatory sequence known as the ARE, characterized by the core consensus sequence 5′-TGACnnnGC-3′ [22]. This binding event initiates a multi-layered transcriptional program designed to restore cellular homeostasis across several functional domains [14]. Foremost among these is the upregulation of antioxidant and detoxification enzymes, including heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1) and NADPH quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), which reinforce antioxidant defenses and modulate redox homeostasis to counter ROS accumulation. Simultaneously, NRF2 coordinates the induction of thiol-based redox buffers, regulating genes for glutathione biosynthesis (GCLC, GCLM), regeneration (GSR), and utilization (GSTs), as well as components of the thioredoxin system (TXN, TXNRD1) [14,22]. Beyond direct scavenging, the pathway drives metabolic reprogramming to support these defenses, notably by redirecting glucose flux into the pentose phosphate pathway via glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) to generate the reducing equivalent NADPH. Furthermore, NRF2 enhances proteostasis by increasing the expression of proteasome subunits and autophagy-related genes like p62/SQSTM1, facilitating the clearance of damaged proteins and organelles [14,23]. Finally, the pathway exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing pro-inflammatory gene expression, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), often by interfering with NF-κB signaling [24]. This coordinated response underscores the role of NRF2 not merely as an antioxidant factor but as a central regulator of cellular defense [14,25], as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the NRF2-KEAP1 signaling pathway. Basal state: Under homeostatic conditions, KEAP1 binds NRF2 in the cytoplasm and serves as an adaptor for the CUL3-RBX1 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, targeting NRF2 for proteasomal degradation [16]. Oxidative stress: ROS or electrophiles modify reactive cysteine residues on KEAP1 (e.g., C151), causing a conformational change [18]. This inhibits ubiquitination, allowing NRF2 to accumulate. Non-classic mechanisms, such as p62/SQSTM1-mediated autophagy, also contribute to NRF2 stabilization [20]. Nuclear translocation: Stabilized NRF2 translocates to the nucleus and heterodimerizes with sMaf. The complex binds to ARE to induce the transcription of genes regulating antioxidant defense (HMOX1, NQO1), glutathione synthesis, and metabolism [20,22]. Created in BioRender. Peng, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/xh710le (accessed on 3 February 2026).

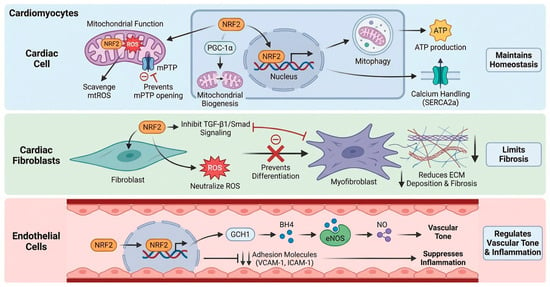

2.2. NRF2-Mediated Redox Defense in Different Cardiac Cell Types

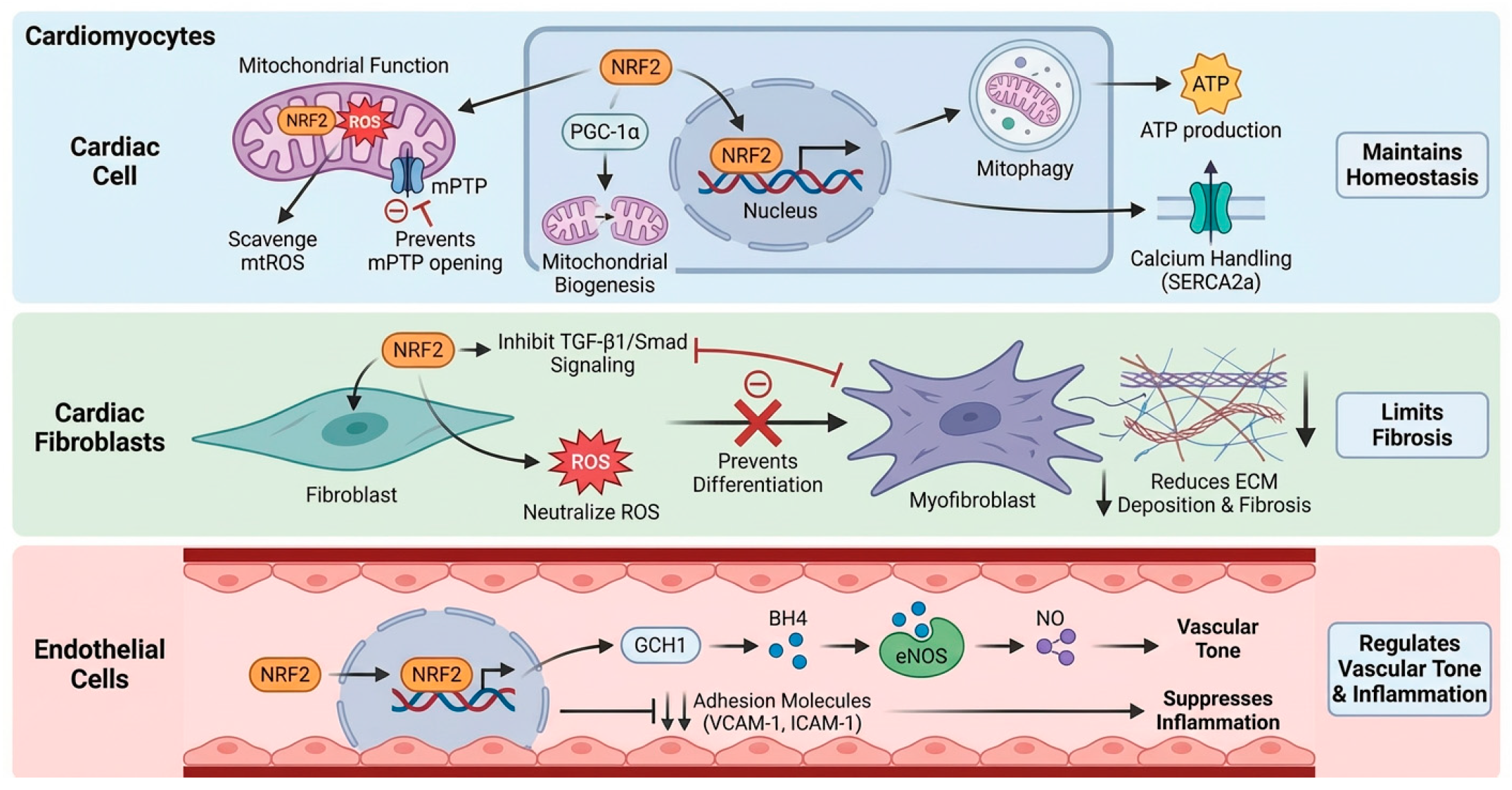

2.2.1. Cardiomyocytes

In the high energy demand environment of cardiomyocytes, NRF2 is critical for maintaining mitochondrial function and cell survival. Its activation directly counteracts mtROS, preserving the integrity of the electron transport chain and preventing the opening of the mPTP-an irreversible step in cell death pathways such as apoptosis and necroptosis [26]. Beyond simple ROS scavenging, NRF2 orchestrates mitochondrial quality control by promoting mitochondrial biogenesis partly through the transcriptional upregulation of Ppargc1a (encoding PGC-1α) and facilitating the autophagic clearance of damaged mitochondria, known as mitophagy [27]. This ensures a healthy and efficient mitochondrial pool, sustaining the high ATP production required for cardiac contraction. Furthermore, by improving bioenergetics and mitigating damage to ion channels and calcium handling proteins like SERCA2a, NRF2 helps preserve contractile function and prevent arrhythmogenesis [28].

2.2.2. Cardiac Fibroblasts

NRF2 acts as a negative regulator of pathological cardiac fibrosis. ROS function as critical cofactors for the activation of the master pro-fibrotic cytokine, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1). NRF2-driven antioxidant activity scavenges these ROS, raising the threshold for fibroblast activation. Additionally, NRF2 antagonizes TGF-β1/Smad signaling by promoting Smad7 expression or interfering with Smad2/3 nuclear accumulation [29]. By attenuating this fibrogenic axis, NRF2 inhibits the transdifferentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts [30], thereby limiting the deposition of extracellular matrix proteins. This preservation of myocardial compliance is essential for preventing diastolic dysfunction and the progression of heart failure.

2.2.3. Vascular Endothelial Cells

Within the cardiac vasculature, NRF2 is a key regulator of endothelial homeostasis. Its activation maintains eNOS coupling, primarily by upregulating GTP cyclohydrolase I (GCH1) to synthesize the essential cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). This prevents eNOS uncoupling and superoxide production, ensuring NO bioavailability and endothelium-dependent vasodilation [31,32]. The NRF2 target gene HMOX1 further contributes to vasodilation via the production of carbon monoxide (CO) [33]. Critically, NRF2 promotes an anti-inflammatory and anti-thrombotic phenotype by suppressing adhesion molecules, such as VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, reducing leukocyte recruitment and vascular inflammation [34], as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Cell-specific roles of NRF2 in the cardiovascular system. Cardiomyocytes: NRF2 maintains mitochondrial function by scavenging mtROS and preventing mPTP opening [26]. It also promotes mitochondrial biogenesis (via PGC-1α) and mitophagy, ensuring efficient ATP production and calcium handling (e.g., SERCA2a) [27,28]. Cardiac Fibroblasts: NRF2 limits fibrosis by scavenging ROS and inhibiting TGF-β1/Smad signaling [29,30]. This suppression prevents fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation and reduces extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition. Endothelial Cells: NRF2 regulates vascular tone and inflammation. It maintains eNOS coupling via GCH1-mediated BH4 synthesis to ensure NO bioavailability and suppresses the expression of adhesion molecules (VCAM-1, ICAM-1) [31,34]. Created in BioRender. Peng, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/v2baujo (accessed on 3 February 2026).

2.2.4. Other Cell Populations

Beyond the major cardiac cell types, NRF2 plays a critical role in the immune and conduction compartments. In macrophages, NRF2 activation promotes a phenotypic switch from the pro-inflammatory M1 state to the reparative M2 phenotype, thereby limiting post-infarction inflammation and facilitating tissue repair [35]. Furthermore, within the cardiac conduction system, NRF2 helps maintain the redox state of critical ion channels. ROS-induced oxidation of CaMKII and voltage-gated sodium channels (Nav1.5) provides a substrate for arrhythmias [36]; thus, constitutive NRF2 activity in these cells serves as an intrinsic anti-arrhythmic barrier, preserving electrical stability under stress.

3. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of NRF2 in CVD

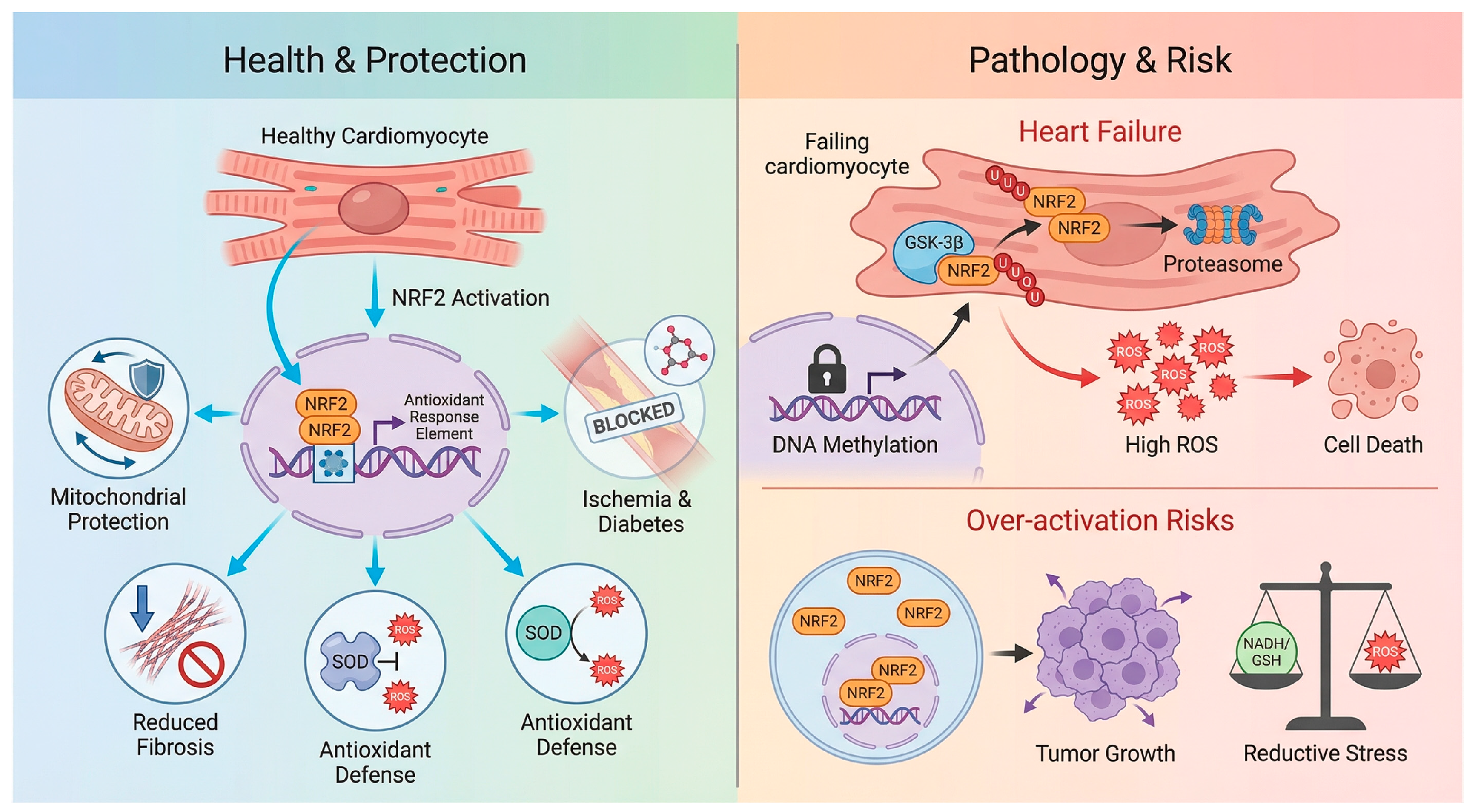

The functional impact of NRF2 within the cardiovascular system is not binary but is determined by the nature, duration, and intensity of the stressor. While NRF2 serves a primary antioxidant regulator against acute oxidative insults, its role in chronic remodeling is complicated by impaired signaling capacity, and its excessive activation carries the risk of reductive stress [37].

3.1. Regulation of Oxidative Stress and Cell Death During CVD

The rapid mobilization of NRF2 is critical in scenarios of acute oxidative surges, particularly ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. The burst of ROS upon reperfusion overwhelms basal defenses, triggering a cascade of regulated cell death. NRF2-knockout mice exhibit expanded infarct sizes, severe contractile dysfunction, and post-I/R lethality, confirming the essential role of the endogenous pathway [32]. Mechanistically, the protective scope of NRF2 extends beyond simple ROS scavenging to the regulation of distinct cell death modalities. One primary mechanism involves the inhibition of necroptosis, where NRF2 upregulates downstream effectors such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and NQO1. These enzymes function to preserve mitochondrial membrane potential and inhibit the opening of the mPTP, thereby preventing cytochrome c release and subsequent cell death [38,39,40]. Furthermore, recent evidence highlights a critical role for NRF2 in the suppression of ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of cell death driven by phospholipid peroxidation. By directly transcriptionally activating SLC7A11 and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), NRF2 maintains intracellular glutathione levels and reduces lipid hydroperoxides, effectively limiting the propagation of lethal lipid ROS waves during the reperfusion phase [41].

Crucially, NRF2 also plays a pivotal role in stabilizing cardiac electrophysiology. ROS-induced oxidation of CaMKII and sarcolemmal ion channels, such as Nav1.5, predisposes the heart to fatal reperfusion arrhythmias [36]. By maintaining the reduced state of these channels within the cardiac conduction system, NRF2 effectively raises the threshold for arrhythmogenesis [41]. Consequently, pharmacological pre-conditioning with inducers like sulforaphane acts as a protective shield, limiting structural infarction, ferroptotic cell loss, and electrical instability [42].

3.2. Modulation of Inflammation and Fibrosis in Chronic Remodeling

In chronic conditions, the landscape changes significantly. NRF2 serves as a critical modulator of cardiac fibrosis and inflammation, under conditions of chronic pressure overload or diabetic cardiomyopathy, NRF2 acts as a negative regulator of fibrosis and hypertrophy [43]. Genetic ablation of NRF2 accelerates the transition to heart failure, a process driven by ROS-dependent pro-fibrotic signaling via the TGF-β/Smad axis and lipid peroxidation [13,39,44,45]. Furthermore, in diabetic models, NRF2 activation specifically dampens NLRP3 inflammasome activity, breaking the cycle between metabolic dysfunction and inflammation [40].

However, a clinically relevant paradox is that NRF2 activity is often significantly blunted in human end-stage heart failure, a state of acquired insufficiency [46]. This phenomenon, termed “acquired NRF2 insufficiency”, implies that the antioxidant reserve is exhausted during the progression from compensated hypertrophy to decompensated failure. The underlying mechanisms constitute a multifactorial blockade [47]. Epigenetic silencing plays a major role, as the NRF2 promoter undergoes hypermethylation by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) alongside repressive histone deacetylation mediated by upregulated HDACs, effectively locking the gene in a transcriptionally silent state [48]. This is compounded by aberrant degradation pathways, where chronic neurohumoral stimulation leads to the persistent activation of kinases such as GSK-3β and Fyn, these kinases phosphorylate NRF2 to promote its nuclear export and degradation independent of the KEAP1 pathway [49]. Moreover, metabolic exhaustion ensues, as NRF2 is required for the expression of fatty acid oxidation genes such as CPT1A. Its downregulation forces the failing heart to rely on inefficient glycolysis, creating an energy-deficit cycle that worsens contractile failure. Finally, impaired autophagy disrupts the p62-mediated positive feedback loop, further compromising the cell’s ability to stabilize NRF2 [44]. This deficiency suggests that in chronic settings, the therapeutic goal is not merely activation but the restoration of a dysfunctional signaling machinery [44,45].

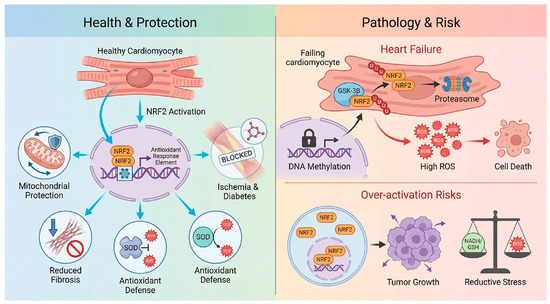

3.3. Pathological Consequences of Reductive Stress and Hyperactivation

Despite its protective potential, viewing NRF2 activation as a universally beneficial strategy is an oversimplification. Pathological hyperactivation introduces significant risks associated with the “U-shaped” therapeutic window.

The primary risk is reductive stress and protein aggregation [50]. Physiological levels of ROS are essential signaling messengers for processes such as angiogenesis and insulin signaling [5]. The abrogation of these signals by supranormal NRF2 levels results in a highly reducing environment that impairs the formation of disulfide bonds required for protein folding [51]. This can paradoxically induce cardiomyopathy, as observed in models of desmin-related cardiomyopathy, where excessive reduction exacerbates the accumulation of toxic protein aggregates, leading to heart failure [5,51].

Furthermore, the impact of NRF2 is spatially distinct, highlighting a context-dependent maladaptation [5]. While NRF2 loss is detrimental in the left ventricle, its constitutive hyperactivation contributes to the pathology of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) [52]. In the right ventricle and pulmonary vasculature, aberrant NRF2 activation promotes a “cancer-like” pro-proliferative phenotype in smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts, worsening vascular remodeling and right ventricular failure [53]. This stark contrast underscores the complexity of systemic NRF2 targeting.

Beyond cardiac toxicity, systemic NRF2 hyperactivation raises concerns regarding oncogenic mimicry. Somatic gain-of-function mutations in NRF2 or loss-of-function mutations in KEAP1 drive numerous malignancies by facilitating chemoresistance and metabolic reprogramming [53]. Although therapeutic activation has not been directly linked to de novo cardiac tumorigenesis, long-term systemic use of potent inducers could theoretically provide a growth advantage to subclinical, pre-malignant lesions. Additionally, chronic hyperactivation stimulates anabolic pathways, shunting glucose and glutamine toward NADPH generation and biosynthesis, which may disrupt whole-body energy homeostasis and lipid metabolism [25]. Consequently, therapeutic strategies must prioritize temporally controlled and cardiovascular-targeted delivery to avoid tipping the balance from oxidative damage to reductive stress, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The double-edged sword of NRF2 modulation in cardiovascular disease. Health & Protection: In the context of I/R, pressure overload, and diabetic cardiomyopathy, NRF2 activation exerts cardioprotective effects by scavenging ROS, preserving mitochondrial integrity, and inhibiting inflammation/fibrosis [32,38,39,40]. Pathology & Risk: The therapeutic window is limited by two opposing factors. Top: In advanced heart failure, “Acquired NRF2 Insufficiency” occurs due to epigenetic silencing such as promoter methylation, and enhanced degradation via GSK-3β, rendering the heart susceptible to oxidative damage [43]. Over-activation Risks Conversely, constitutive or systemic NRF2 hyperactivation carries risks of reductive stress, metabolic dysregulation, and the potential acceleration of pre-existing malignancies [13,39,44,45]. Created in BioRender. Peng, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/i14v33m (accessed on 3 February 2026).

4. Therapeutic Targeting of NRF2

The clinical translation of NRF2 modulation has been characterized by a significant inconsistency between preclinical efficacy and clinical outcomes. While animal models consistently demonstrate that NRF2 activation confers cardioprotection against ischemic and non-ischemic injury, human trials utilizing systemic electrophilic activators have highlighted significant safety concerns, most notably the risk of fluid retention and heart failure in vulnerable populations. The therapeutic landscape is currently evolving across three primary approaches: pharmacological innovation, advanced delivery systems, and biomarker-guided stratification. Consequently, current research efforts are focused on addressing these safety liabilities to improve the therapeutic index. The following sections review the evidence regarding current pharmacological strategies.

4.1. Pharmacological Strategies

4.1.1. Covalent Electrophilic Modulators

Initial strategies focused on electrophilic compounds that covalently modify reactive cysteines on KEAP1. The prototype of this class is the phytochemical sulforaphane (SFN). While SFN reduces infarct size and fibrosis in rodent models, its clinical translation has been hindered by rapid metabolism via glutathione conjugation and variable oral bioavailability [54,55,56]. To improve potency, synthetic oleanane triterpenoids, such as bardoxolone methyl (CDDO-Me), were developed. In trials for chronic kidney disease (CKD), bardoxolone significantly improved the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) [57]. However, the pivotal Phase III BEACON trial was terminated early due to a significant increase in heart failure-related adverse events in the treatment arm [58]. Post hoc analyses attributed this outcome not to direct cardiotoxicity, but to fluid retention potentially mediated by off-target modulation of the endothelin-1 pathway [59,60]. Similarly, Dimethyl Fumarate (DMF), while approved for multiple sclerosis, activates NRF2 via succination of KEAP1 but also engages the hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 (HCAR2). This off-target interaction is linked to adverse effects such as cutaneous flushing and gastrointestinal distress [60,61]. For patients with cardiovascular diseases, this systemic limitation is particularly problematic, as they often require long-term treatment and are highly sensitive to hemodynamic fluctuations, this underscores the necessity of developing more cardiac-specific NRF2 modulators or targeted delivery platforms to minimize systemic exposure. These clinical data indicate that while high-potency electrophiles can induce antioxidant gene expression, their systemic reactivity and off-target profiles present substantial safety concerns, particularly for patients with compromised cardiac reserve.

4.1.2. Non-Covalent Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Inhibitors

To address the lack of specificity associated with electrophilic cysteine modification, drug discovery has shifted toward the non-covalent disruption of the KEAP1-NRF2 protein–protein interaction (PPI). Small-molecule inhibitors in this class are designed to competitively bind to the Kelch domain of KEAP1, displacing NRF2 without chemically modifying cellular proteins [62]. In preclinical studies, prototypes including naphthalene-based compounds and isoquinoline derivatives have attenuated diabetic cardiomyopathy phenotypes [63]. However, the clinical viability of PPI inhibitors remains unproven. These compounds often face significant challenges regarding solubility and membrane permeability. Moreover, while they may reduce off-target toxicity, evidence is currently lacking regarding their long-term safety profiles. PPI inhibition does not inherently resolve the physiological risk of constitutive NRF2 hyperactivation, suggesting that establishing a precise therapeutic window remains a necessity regardless of the activation modality [15].

4.1.3. Targeted Delivery and Regulated Gene Expression

Minimizing systemic exposure while maximizing cardiac benefit remains a central objective of NRF2 therapy. Nanomedicine offers a potential strategy through the engineering of cardiac-homing nanoparticles. Liposomes or polymeric nanoparticles can be functionalized with ligands such as ischemic-targeting peptides (e.g., CSTSMLKAC), ensuring that NRF2 activators are released preferentially at sites of myocardial injury [64,65]. Beyond synthetic carriers, biological vectors like exosomes-endogenous nanovesicles derived from stem cells-are being explored as biocompatible delivery vehicles for NRF2 mRNA or protein, offering lower immunogenicity. Furthermore, exosome-based interventions are increasingly viewed as a promising therapeutic strategy that may enhance endogenous antioxidant defenses while potentially bypassing some of the safety concerns associated with live-cell therapies. Parallel efforts in gene therapy utilize adeno-associated viruses, specifically the cardiotropic serotype AAV9, to drive NRF2 overexpression directly in cardiomyocytes [66]. To avoid the maladaptive consequences of unchecked expression, next-generation vectors incorporate cardiac-specific promoters (e.g., α-MHC) or inducible Tet-on systems, allowing clinicians to temporally control NRF2 activity [67]. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that these targeted approaches are still in nascent stages. Although they theoretically decouple cardioprotection from systemic toxicity, their clinical safety and efficacy remain unproven. Translating these technological platforms from murine models to human heart failure requires overcoming significant barriers in manufacturing, stability, and potential immunogenicity before they can be considered viable therapeutic options.

4.2. The Translational Roadmap

4.2.1. Defining the Therapeutic Window

A critical barrier to clinical success is the definition of the optimal therapeutic window. This requires a nuanced understanding of dose, timing, and duration. While preclinical data suggest that pulsatile, transient activation during acute stress (e.g., post-MI reperfusion) may be superior to chronic, low-level modulation, this hypothesis has not yet been validated in humans. Chronic activation carries the theoretical risk of inducing reductive stress or metabolic inflexibility. Therefore, rather than assuming the efficacy of continuous dosing, future investigations should evaluate whether “hit-and-run” strategies tailored to the distinct phases of cardiac remodeling offer a superior safety profile [15].

4.2.2. Combination Therapies

Given the multifactorial nature of heart failure, NRF2 modulators are unlikely to serve as monotherapies but rather as potent adjuncts. There is a strong theoretical rationale for combination therapies. Potential synergy with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors is particularly notable, as SGLT2 inhibitors improve mitochondrial energetics and activate AMPK/SIRT1 pathways that converge with NRF2 signaling to enhance metabolic flexibility [68,69]. Furthermore, combining NRF2 activators with neurohormonal blockade-such as angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs)-could hypothetically provide additive benefits by simultaneously targeting fibrosis, hemodynamic load, and oxidative stress [69]. However, considering the complexity of heart failure polypharmacy, extreme vigilance is required. Clinical studies must rigorously assess whether pharmacological redox modulation antagonizes the beneficial, physiological inflammatory signaling required for tissue repair [15].

4.2.3. Biomarkers for Patient Stratification

The failure of broad-spectrum antioxidant trials suggests that a “one-size-fits-all” approach is likely ineffective. The development of validated biomarkers is proposed as a prerequisite for precision patient stratification, aiming to identify specific sub-populations with an “NRF2-deficient” phenotype who are most likely to benefit from therapy. Future diagnostic strategies should explore the utility of creating a composite “redox signature” by integrating multi-omics data. This would include transcriptomic profiling of NRF2 target genes (e.g., NQO1, GCLM) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, proteomic analysis of oxidative damage markers (e.g., nitrotyrosine), and metabolomic assessment of the GSH/GSSG ratio [46]. Additionally, epigenetic screening for NRF2 promoter methylation could identify patients with acquired resistance to endogenous activation. While promising conceptually, the predictive value of these biomarkers requires prospective validation in large-scale clinical cohorts before they can guide treatment decisions [46,70,71], as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pharmacological Strategies of NRF2 in Cardiovascular Drug Development.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

5.1. NRF2 as a Central Regulator of Cardiovascular Redox Homeostasis

In summary, the NRF2-KEAP1 axis functions not merely as a responsive antioxidant switch but as a central integration hub governing the structural and metabolic fidelity of the cardiovascular system. As detailed comprehensively in this review, the protective scope of NRF2 extends far beyond simple radical scavenging to orchestrate a sophisticated, multi-layered defense strategy. At the organelle level, NRF2 is indispensable for mitochondrial integrity, preserving bioenergetics through the upregulation of biogenesis factors like PGC-1α and preventing lethal necrosis by inhibiting the opening of the mPTP. At the cellular level, emerging evidence highlighted in this paper underscores its pivotal role in suppressing ferroptosis, a lipid-peroxidation-dependent cell death, via the transcriptional activation of the SLC7A11-GPX4 axis. Furthermore, within the extracellular matrix, NRF2 serves as a critical brake on pathological remodeling by antagonizing the TGF-β/Smad signaling cascade, thereby limiting myofibroblast differentiation and interstitial fibrosis [15]. Consequently, extensive preclinical data confirm that NRF2 is a central, druggable node capable of determining the trajectory of heart failure, acting as a bulwark against the diverse insults of ischemia, pressure overload, and metabolic toxicity.

5.2. The Paradox of Acquired Insufficiency and Reductive Stress

Despite this robust protective potential, the translation of NRF2 biology into clinical practice is complicated by the distinct pathophysiological paradoxes discussed in this review. A primary challenge remains the phenomenon of “acquired NRF2 insufficiency” observed in the failing human heart. As we have examined, this loss of reserve capacity is driven by a convergence of epigenetic silencing via promoter methylation, aberrant degradation mediated by GSK-3β, and the disruption of the p62-dependent autophagy feedback loop. This downregulation renders the chronic heart failure myocardium critically vulnerable to oxidative damage. Conversely, the opposing end of the spectrum presents the risk of “reductive stress”. Unchecked, supranormal activation of NRF2 can annihilate physiological ROS signaling required for protein folding and angiogenesis, potentially leading to protein aggregation cardiomyopathies or maladaptive vascular remodeling as seen in pulmonary hypertension. Therefore, future research directions must pivot from simply asking how to activate NRF2, to elucidating how to restore its physiological range. It is essential to decipher the specific epigenetic and post-translational checkpoints that lock the pathway in a silenced state during chronic remodeling, as reversing these molecular brakes offers a more rational strategy than forcing activation in a dysregulated system.

5.3. The Evolution Toward Precision Therapeutic Modulation

The therapeutic landscape is consequently undergoing a necessary evolution from systemic, indiscriminate induction toward precision redox medicine. The history of NRF2 pharmacology, particularly the lessons learned from the Bardoxolone methyl trials, illustrates the dangers of broad-spectrum electrophilic activation, where off-target engagement of pathways like endothelin-1 can precipitate fluid retention and clinical decompensation. The future of NRF2-based therapeutics lies in the refinement of intervention strategies that decouple cardioprotection from these systemic liabilities. This review highlights the promise of next-generation PPI inhibitors, which offer non-covalent, highly specific displacement of NRF2 from KEAP1, minimizing the side effects of earlier agents. Moreover, the integration of advanced delivery systems, such as cardiac-homing nanoparticles and cardiotropic AAV9 gene therapy vectors, represents a critical frontier to achieve tissue-specific modulation. Ultimately, the successful clinical implementation of these modulators will depend on the concurrent development of validated multi-omics biomarkers to identify patient subgroups with a demonstrable “redox-deficient” phenotype. By harmonizing these pharmacological, technological, and diagnostic advancements, it is possible to harness the potent defense mechanisms of the NRF2-KEAP1 axis to arrest the progression of cardiovascular disease while navigating the complex boundary between essential physiological signaling and pathological stress.

Author Contributions

Y.P., J.W. and Y.Y.: study conception and design; Y.P.: writing—original draft preparation; Y.P.: writing—review and editing; Y.P. and Y.Y.: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Kaiyang Gao for their valuable contributions to this study. We also thank Baihe Li and Lan Tao for their helpful support during the revision process. The authors acknowledge the use of generative AI-assisted tools for limited support during the preparation of this manuscript. Specifically, Google Gemini (model 3 Pro, version current as of December 2025) was utilized for language refinement. The figures were created by the authors using BioRender.com, with valuable generative design assistance from Google Gemini. All scientific content, analyses, and conclusions were developed and validated exclusively by the authors. The authors have reviewed and edited all AI-assisted output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 147, e93–e621, Correction in Circulation 2023, 147, e622. Correction in Circulation 2023, 148, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021, Correction in J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1958–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangogiannis, N.G. Cardiac fibrosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 1450–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertero, E.; Maack, C. Metabolic remodelling in heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peoples, J.N.; Saraf, A.; Ghazal, N.; Pham, T.T.; Kwong, J.Q. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in heart disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E.T.; Pell, V.R.; Gaude, E.; Aksentijević, D.; Sundier, S.Y.; Robb, E.L.; Logan, A.; Nadtochiy, S.M.; Ord, E.N.J.; Smith, A.C.; et al. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature 2014, 515, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teuber, J.P.; Essandoh, K.; Hummel, S.L.; Madamanchi, N.R.; Brody, M.J. NADPH Oxidases in Diastolic Dysfunction and Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daiber, A.; Xia, N.; Steven, S.; Oelze, M.; Hanf, A.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Münzel, T.; Li, H. New Therapeutic Implications of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase (eNOS) Function/Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, D.; Hu, D.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Y. The role of mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 103, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Re, D.P.; Amgalan, D.; Linkermann, A.; Liu, Q.; Kitsis, R.N. Fundamental Mechanisms of Regulated Cell Death and Implications for Heart Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1765–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.H.; Fefelova, N.; Pamarthi, S.H.; Gwathmey, J.K. Molecular Mechanisms of Ferroptosis and Relevance to Cardiovascular Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Camici, G.G.; Maack, C.; Bonetti, N.R.; Fuster, V.; Kovacic, J.C. Impact of Oxidative Stress on the Heart and Vasculature: Part 2 of a 3-Part Series. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.D.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. The Nrf2 regulatory network provides an interface between redox and intermediary metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014, 39, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodson, M.; de la Vega, M.R.; Cholanians, A.B.; Schmidlin, C.J.; Chapman, E.; Zhang, D.D. Modulating NRF2 in Disease: Timing is Everything. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2019, 59, 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinan, S.B.; Gordan, J.D.; Jin, J.; Harper, J.W.; Diehl, J.A. The Keap1-BTB protein is an adaptor that bridges Nrf2 to a Cul3-based E3 ligase: Oxidative stress sensing by a Cul3-Keap1 ligase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 8477–8486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, L.; Yamamoto, M. The Molecular Mechanisms Regulating the KEAP1-NRF2 Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2020, 40, e00099-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, R.; Suzuki, T.; Hiramoto, K.; Asami, S.; Naganuma, E.; Suda, H.; Iso, T.; Yamamoto, H.; Morita, M.; Baird, L.; et al. Characterizations of Three Major Cysteine Sensors of Keap1 in Stress Response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2016, 36, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Yamamoto, M. Molecular basis of the Keap1-Nrf2 system. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, M.; Kurokawa, H.; Waguri, S.; Taguchi, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Ichimura, Y.; Sou, Y.S.; Ueno, I.; Sakamoto, A.; Tong, K.I.; et al. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloer, E.W.; Siesser, P.F.; Cousins, E.M.; Goldfarb, D.; Mowrey, D.D.; Harrison, J.S.; Weir, S.J.; Dokholyan, N.V.; Major, M.B. p62-Dependent Phase Separation of Patient-Derived KEAP1 Mutations and NRF2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2018, 38, e00644-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, K.; Chiba, T.; Takahashi, S.; Ishii, T.; Igarashi, K.; Katoh, Y.; Oyake, T.; Hayashi, N.; Satoh, K.; Hatayama, I.; et al. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 236, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajares, M.; Cuadrado, A.; Rojo, A.I. Modulation of proteostasis by transcription factor NRF2 and impact in neurodegenerative diseases. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.M.U.; Luo, L.; Namani, A.; Wang, X.J.; Tang, X. Nrf2 signaling pathway: Pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuishi, Y.; Taguchi, K.; Kawatani, Y.; Shibata, T.; Nukiwa, T.; Aburatani, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Motohashi, H. Nrf2 redirects glucose and glutamine into anabolic pathways in metabolic reprogramming. Cancer Cell 2012, 22, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, K.M.; Kostov, R.V.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. The multifaceted role of Nrf2 in mitochondrial function. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2016, 1, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merry, T.L.; Ristow, M. Nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-like 2 (NFE2L2, Nrf2) mediates exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis and the anti-oxidant response in mice. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 5195–5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.M. Nrf2 for cardiac protection: Pharmacological options against oxidative stress. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 42, 729–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, B.; Wei, J.; Zheng, Z.; Su, J.; Bian, C.; Xin, Y.; Jiang, X. Sulforaphane regulates Nrf2-mediated antioxidant activity and downregulates TGF-β1/Smad pathways to prevent radiation-induced muscle fibrosis. Life Sci. 2022, 311, 121197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, C.; Alves, I.; Singh, P.; Palade, P.T.; Carvalho, E.; Børsheim, E.; Jun, S.R.; Cheema, A.; Boerma, M.; Awasthi, S.; et al. Sulforaphane prevents age-associated cardiac and muscular dysfunction through Nrf2 signaling. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, A.M.; Griendling, K.K. NADPH oxidases and angiotensin II receptor signaling. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 302, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkens, R.; Suvorava, T.; Sutton, T.R.; Fernandez, B.O.; Mikus-Lelinska, M.; Barbarino, F.; Flögel, U.; Kelm, M.; Feelisch, M.; Cortese-Krott, M.M. Nrf2 Deficiency Unmasks the Significance of Nitric Oxide Synthase Activity for Cardioprotection. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 8309698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, W.; Johnson, F.K.; Johnson, R.A. Role of carbon monoxide in cardiovascular function. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2006, 10, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.R.; Lyon, C.J.; Xia, X.; Liu, J.Z.; Tangirala, R.K.; Yin, F.; Boyadjian, R.; Bikineyeva, A.; Praticò, D.; Harrison, D.G.; et al. Age-accelerated atherosclerosis correlates with failure to upregulate antioxidant genes. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, e42–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, E.H.; Suzuki, T.; Funayama, R.; Nagashima, T.; Hayashi, M.; Sekine, H.; Tanaka, N.; Moriguchi, T.; Motohashi, H.; Nakayama, K.; et al. Nrf2 suppresses macrophage inflammatory response by blocking proinflammatory cytokine transcription. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.; Aistrup, G.; Shiferaw, Y.; Ng, J.; Mohler, P.J.; Hund, T.J.; Waugh, T.; Browne, S.; Gussak, G.; Gilani, M.; et al. Oxidative stress creates a unique, CaMKII-mediated substrate for atrial fibrillation in heart failure. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e120728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhyani, N.; Tian, C.; Gao, L.; Rudebush, T.L.; Zucker, I.H. Nrf2-Keap1 in Cardiovascular Disease: Which Is the Cart and Which the Horse? Physiology 2024, 39, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Ichikawa, T.; Villacorta, L.; Janicki, J.S.; Brower, G.L.; Yamamoto, M.; Cui, T. Nrf2 protects against maladaptive cardiac responses to hemodynamic stress. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009, 29, 1843–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsumata, Y.; Shinmura, K.; Sugiura, Y.; Tohyama, S.; Matsuhashi, T.; Ito, H.; Yan, X.; Ito, K.; Yuasa, S.; Ieda, M.; et al. Endogenous prostaglandin D2 and its metabolites protect the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury by activating Nrf2. Hypertension 2014, 63, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, W.; Tao, L.; Lu, P.; Wang, Y.; Hu, R. Nuclear Factor E2-Related Factor-2 Negatively Regulates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activity by Inhibiting Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced NLRP3 Priming. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 26, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Pan, J.; Huang, S.; Chen, X.; Chang, A.C.Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. Hydrogen sulfide protects cardiomyocytes from doxorubicin-induced ferroptosis through the SLC7A11/GSH/GPx4 pathway by Keap1 S-sulfhydration and Nrf2 activation. Redox Biol. 2024, 70, 103066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Cui, W.; Xin, Y.; Miao, X.; Barati, M.T.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Q.; Tan, Y.; Cui, T.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Prevention by sulforaphane of diabetic cardiomyopathy is associated with up-regulation of Nrf2 expression and transcription activation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2013, 57, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkens, R.; Kramer, C.M.; Lückstädt, W.; Panknin, C.; Krause, L.; Weidenbach, M.; Dirzka, J.; Krenz, T.; Mergia, E.; Suvorava, T.; et al. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in Nrf2 knock out mice is associated with cardiac hypertrophy, decreased expression of SERCA2a, and preserved endothelial function. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, M.; Rajasekaran, N.S. Exercise, Nrf2 and Antioxidant Signaling in Cardiac Aging. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Ichikawa, T.; Li, J.; Si, Q.; Yang, H.; Chen, X.; Goldblatt, C.S.; Meyer, C.J.; Li, X.; Cai, L.; et al. Diabetic downregulation of Nrf2 activity via ERK contributes to oxidative stress-induced insulin resistance in cardiac cells in vitro and in vivo. Diabetes 2011, 60, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Pan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, M.; Yin, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Han, L.; Bai, J.; Jiang, T.; et al. Comprehensive overview of Nrf2-related epigenetic regulations involved in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Theranostics 2022, 12, 6626–6645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, Y. The role of Nrf2-mediated pathway in cardiac remodeling and heart failure. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 260429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Islas, C.A.; Maldonado, P.D. Canonical and non-canonical mechanisms of Nrf2 activation. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 134, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.M. Nrf2 for protection against oxidant generation and mitochondrial damage in cardiac injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 179, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, N.S.; Connell, P.; Christians, E.S.; Yan, L.J.; Taylor, R.P.; Orosz, A.; Zhang, X.Q.; Stevenson, T.J.; Peshock, R.M.; Leopold, J.A.; et al. Human alpha B-crystallin mutation causes oxido-reductive stress and protein aggregation cardiomyopathy in mice. Cell 2007, 130, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, D.; Loscalzo, J. Redox regulation of mitochondrial function. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 16, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhong, J.-H.; Wei, X.-D.; Huang, C.-Y.; Peng, P.-L.; Yao, J.; Song, X.-S.; Fan, W.-L.; Li, G.-C. Pachymic Acid Ameliorates Pulmonary Hypertension by Regulating Nrf2-Keap1-ARE Pathway. Curr. Med. Sci. 2022, 42, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Vega, M.R.; Chapman, E.; Zhang, D.D. NRF2 and the Hallmarks of Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, W.; Men, H.; Bao, T.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Tan, Y.; Keller, B.B.; Tong, Q.; et al. Ferroptosis is essential for diabetic cardiomyopathy and is prevented by sulforaphane via AMPK/NRF2 pathways. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 708–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Holtzclaw, W.D.; Cole, R.N.; Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Katoh, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Talalay, P. Direct evidence that sulfhydryl groups of Keap1 are the sensors regulating induction of phase 2 enzymes that protect against carcinogens and oxidants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 11908–11913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagishita, Y.; Fahey, J.W.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Kensler, T.W. Broccoli or Sulforaphane: Is It the Source or Dose That Matters? Molecules 2019, 24, 3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, P.E.; Raskin, P.; Toto, R.D.; Meyer, C.J.; Huff, J.W.; Grossman, E.B.; Krauth, M.; Ruiz, S.; Audhya, P.; Christ-Schmidt, H.; et al. Bardoxolone methyl and kidney function in CKD with type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zeeuw, D.; Akizawa, T.; Audhya, P.; Bakris, G.L.; Chin, M.; Christ-Schmidt, H.; Goldsberry, A.; Houser, M.; Krauth, M.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; et al. Bardoxolone methyl in type 2 diabetes and stage 4 chronic kidney disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 2492–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, M.P.; Wrolstad, D.; Bakris, G.L.; Chertow, G.M.; de Zeeuw, D.; Goldsberry, A.; Linde, P.G.; McCullough, P.A.; McMurray, J.J.; Wittes, J.; et al. Risk factors for heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stage 4 chronic kidney disease treated with bardoxolone methyl. J. Card. Fail. 2014, 20, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, M.P.; Bakris, G.L.; Block, G.A.; Chertow, G.M.; Goldsberry, A.; Inker, L.A.; Heerspink, H.J.; O’grady, M.; Pergola, P.E.; Wanner, C.; et al. Bardoxolone Methyl Improves Kidney Function in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease Stage 4 and Type 2 Diabetes: Post-Hoc Analyses from Bardoxolone Methyl Evaluation in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Study. Am. J. Nephrol. 2018, 47, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Assmann, J.C.; Krenz, A.; Rahman, M.; Grimm, M.; Karsten, C.M.; Köhl, J.; Offermanns, S.; Wettschureck, N.; Schwaninger, M. Hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 mediates dimethyl fumarate’s protective effect in EAE. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 2188–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisman, E.; Duarte, P.; Dauden, E.; Cuadrado, A.; Rodríguez-Franco, M.I.; López, M.G.; León, R. KEAP1-NRF2 protein-protein interaction inhibitors: Design, pharmacological properties and therapeutic potential. Med. Res. Rev. 2023, 43, 237–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.Y.; Lu, M.C.; You, Q.D. Discovery and Development of Kelch-like ECH-Associated Protein 1. Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 (KEAP1:NRF2) Protein-Protein Interaction Inhibitors: Achievements, Challenges, and Future Directions. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 10837–10858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, W.C.; Shieh, J.M.; Wu, W.B. P38 MAPK and Nrf2 Activation Mediated Naked Gold Nanoparticle Induced Heme Oxygenase-1 Expression in Rat Aortic Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Arch. Med. Res. 2020, 51, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; He, Z. ROS-responsive drug delivery systems for biomedical applications. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 13, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacak, C.A.; Mah, C.S.; Thattaliyath, B.D.; Conlon, T.J.; Lewis, M.A.; Cloutier, D.E.; Zolotukhin, I.; Tarantal, A.F.; Byrne, B.J. Recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 9 leads to preferential cardiac transduction in vivo. Circ. Res. 2006, 99, e3–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsebo, K.; Yaroshinsky, A.; Rudy, J.J.; Wagner, K.; Greenberg, B.; Jessup, M.; Hajjar, R.J. Long-term effects of AAV1/SERCA2a gene transfer in patients with severe heart failure: Analysis of recurrent cardiovascular events and mortality. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Xue, M.; Li, X.; Han, F.; Liu, X.; Xu, L.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Li, T.; et al. SGLT2 inhibition with empagliflozin attenuates myocardial oxidative stress and fibrosis in diabetic mice heart. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2019, 18, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M. SGLT2 Inhibitors Produce Cardiorenal Benefits by Promoting Adaptive Cellular Reprogramming to Induce a State of Fasting Mimicry: A Paradigm Shift in Understanding Their Mechanism of Action. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustarini, D.; Dalle-Donne, I.; Milzani, A.; Fanti, P.; Rossi, R. Analysis of GSH and GSSG after derivatization with N-ethylmaleimide. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 1660–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, D.; Portales-Casamar, E.; Singh, A.; Srivastava, S.; Arenillas, D.; Happel, C.; Shyr, C.; Wakabayashi, N.; Kensler, T.W.; Wasserman, W.W.; et al. Global mapping of binding sites for Nrf2 identifies novel targets in cell survival response through ChIP-Seq profiling and network analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 5718–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.