Abstract

Purpose: To investigate associations between lipid oxidation biomarkers (oxylipins), antioxidant micronutrients, lipoprotein particles, and apolipoproteins in multiple sclerosis (MS). Methods: Blood and neurological assessments were collected from 30 healthy controls, 68 relapsing remitting MS subjects, and 37 progressive MS subjects. Hydroxy (H) and hydroperoxy lipid peroxidation products of the polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) arachidonic (20:4, ω-6), linoleic (octadecadienoic acid or ODE, 18:2, ω-6), eicosapentaenoic (20:5, ω-3), and α-linolenic (18:3, ω-3) acids were measured using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Antioxidant micronutrients, including β-cryptoxanthin and lutein/zeaxanthin, were quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography. Lipoprotein and metabolite profiles were obtained using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Regression models were adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, and disease status. Results: The 9-hydroxy octadecadienoic acid to 13-hydroxy octadecadienoic acid ratio (9-HODE/13-HODE ratio), which reflects autoxidative versus enzymatic oxidation, was associated with MS status (p = 0.002) and disability on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (p = 0.004). Lutein/zeaxanthin (p = 0.023) and β-cryptoxanthin (p = 0.028) were negatively associated with the 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio. Apolipoprotein-CII, a marker of liver-X-receptor (LXR) signaling, was associated with 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio and other oxylipins. Octadecadienoic fatty acid-derived oxylipins were negatively associated with LC3A, a mitophagy marker, and positively correlated with 7-ketocholesterol, a cholesterol autoxidation product. Conclusions: Autoxidation of PUFAs is associated with greater disability in MS. Higher β-cryptoxanthin and lutein/zeaxanthin were associated with reduced auto-oxidation. Lipid peroxidation shows associations with LXR signaling, mitophagy, inflammation, and cholesterol autoxidation.

1. Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurodegenerative disease affecting the brain and spinal cord, characterized by progressive physical and cognitive disability [1,2,3]. Blood–brain barrier breakdown, inflammation, demyelination, and neurodegeneration are the central pathophysiological mechanisms in MS. Oxidative stress is a central metabolic mechanism that can cause neurodegeneration.

Oxidative stress is an imbalance between the damaging effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the detoxifying effects of antioxidant defense molecules that eliminate or scavenge ROS and repair damaged biomolecules.

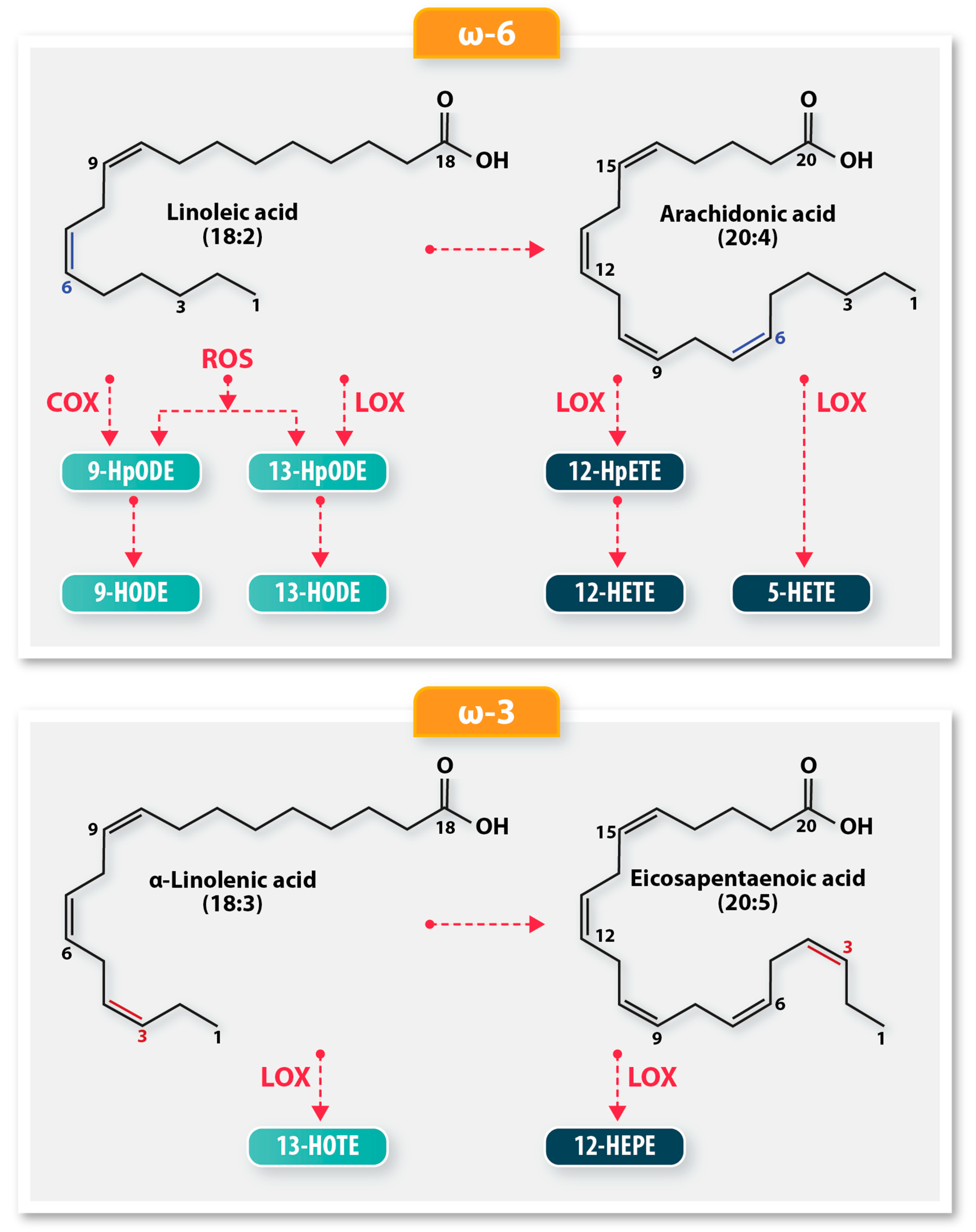

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in lipids are a common target of ROS, leading to lipid peroxidation, a free radical chain reaction, producing hydroperoxy-derivatives. Hydroperoxides are rapidly converted to less reactive hydroxy derivatives by cellular peroxidases. As a group, these hydroperoxy and hydroxy PUFA oxidation products are known as oxylipins (Figure 1). PUFAs can also be oxidized to oxylipins by enzymes such as cyclooxygenases (COX) and lipoxygenases (LOX), including COX-1, COX-2, 15-LOX-1, and 15-LOX-2. In the presence of transition metals like iron, lipid hydroperoxides can form reactive aldehydes that can react with proteins [4]. The continued oxidation of PUFAs can result in altered lipoprotein structure and function, cellular membrane integrity loss, and inactivation of membrane-bound proteins, triggering apoptosis, necrosis, ferroptosis, and inflammatory effects [5,6].

Figure 1.

A schematic of the biochemical pathways resulting in oxylipin derivatives from polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). The ω-6 PUFA, linoleic acid, is oxidized by lipoxygenases (LOX), cyclooxygenases (COX), or autoxidation to produce 9-HODE and 13-HODE. LOX oxidation produces more 13-HODE, while COX oxidation produces a preponderance of 9-HODE oxylipins. Auto-oxidation produces equal amounts of 9-HODE and 13-HODE. Arachidonic acid utilizes different LOX enzymes to produce oxylipin derivatives 12-HpETE, 12-HETE, and 5-HETE. The ω-3 fatty acids, α-linolenic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid, are enzymatically oxidized by LOX to produce the hydroxy oxylipins, 13-HOTE and 12-HEPE, respectively.

The 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio is an important indicator of lipid peroxidation, as it reflects the relative contributions of auto-oxidation, COX, and LOX mechanisms to the oxidative stress environment [7]. 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio values near 1 indicate autoxidation, values greater than 1 reflect predominant COX activity, and values less than 1 are indicative of LOX activity.

Increased dietary intake of ω-3 fatty acids, α-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) are associated with lower levels of pro-inflammatory mediators, C-reactive protein (CRP), and GlycA [8], and with lower incidence of cardiovascular diseases [7], which have been linked to MS progression [9]. ω-6 fatty acids are thought to exert a negative effect on human health.

The balance between anti-inflammatory properties of ω-3 and pro-inflammatory properties of ω-6 PUFAs could also be clinically relevant, given the central role of neuroinflammation in MS pathogenesis. The correlation between fish consumption and lower MS prevalence, [9,10,11] as well as slower disease progression [12,13] in epidemiological studies, can be plausibly attributed to the vitamin D and ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid content in fish. A diet high in ω-3 over ω-6 PUFAs has been suggested to be crucial for bodily processes and overall health in MS. A review of 5554 studies on the effects of EPA, DHA, and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) demonstrated increased ω-3 and fish oil supplementation was beneficial in improving quality of life and disability [10], and reduced relapse rates [14] in patients with MS (pwMS). Excessive consumption of ω-6 PUFAs correlated with increased MS incidence [15]. While ω-6 fatty acids such as arachidonic acid (ARA) may be a precursor for inflammation [16], there are potential benefits of ω-6 PUFA intake. Long-term mixed intake of ω-6 and ω-3 fatty acids improved gait and functional capacity in relapsing-remitting MS patients (RRMS) [17], and total ω-6 PUFAd levels contributed to a decreased MS risk [18]. However, interventional studies with fish oil, ω-3 [19], and ω-6 [20] polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation showed no positive effects on MS clinical outcomes [19,21].

Dietary carotenoids, retinols, and provitamins are potent antioxidants that can reduce oxidative damage by scavenging and terminating free radical-driven chain reactions. Trials of antioxidants as disease-modifying treatments (DMT) in MS have yielded limited and conflicting effects [22,23].

Lipid peroxidation is thought to be a significant contributor to MS inflammation [24] and disease development [25] through oxylipin signaling. The central premise therefore was to investigate whether the products and mechanistic processes (enzymatic versus auto-oxidative) of oxidation, rather than the PUFAs themselves, are relevant to the progression of MS. Determining the involvement of oxylipins in MS could provide mechanistic insight into the failure of fish oil and PUFA supplementation trials. The objective of the research was to investigate the mechanistic contributions, if any, of oxylipins, with antioxidants, lipoproteins, apolipoproteins, and chronic inflammation to MS disability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Study setting and design: This single-center, cross-sectional exploratory study was performed at the Jacobs Multiple Sclerosis Center for Treatment and Research of the University at Buffalo, an academic MS center in Buffalo, NY, USA.

Informed consent: The study protocol was approved by the University at Buffalo Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (Approval code: MODCR00009015), and written consent was obtained from all patients in line with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical assessment: Demographic information was documented, and neurological assessments were performed on all subjects.

Healthy controls (HC) were included if they had a normal examination and were free of neurological disease. Exclusion criteria for HC were preexisting medical conditions associated with brain pathology, including cerebrovascular disease and alcohol abuse disorders.

MS disease course was diagnosed by a licensed neurologist utilizing the 2010 revision of the McDonald criteria. The inclusion criteria for participants with MS for the sub-study included age ≥ 18 and the availability of one or more oxylipin markers as well as NMR biomarkers. The exclusion criteria were: presence of a relapse, use of corticosteroids within 30 days prior to the study, history of cerebral congenital vascular malformations, contraindications for MRI contrast agents, and pregnant or nursing mothers.

The progressive MS (PMS) group consisted of secondary-progressive MS (SPMS) and primary-progressive MS (PPMS) subtypes. The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) was used as a measure of disability.

2.2. Serum Biomarker Analysis

2.2.1. Serum Analysis

Non-fasting blood samples from all participants were separated into serum and plasma within 24 h, and frozen in aliquots at −80 °C. The clinical samples were de-identified for analysts.

2.2.2. Lipid Peroxidation Products Measurements

Total monohydroxy (H) and monohydroperoxy (Hp) lipid peroxidation products of eicosatetraenoic (ETE, 20:4 or arachidonic acid), octadecadienoic (ODE, 18:2 or linoleic acid), and octadecatrienoic (OTE, 18:3 or linolenic acid) fatty acid species were measured from serum samples precisely as described by Zhu et al. [26]. The fatty acids standards; ((±)-9-hydroxy-10E,12Z-octadecadienoic acid (9-HODE), (±)-13-hydroxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13-HODE), 9-hydroperoxy-10E,12Z-octadecadienoic acid (9-HpODE), (±)13-hydroperoxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13-HpODE), 13S-hydroxy-9Z,11E,15Z-octadecatrienoic acid (13(s)-HOTrE), ±12-hydroxy-5Z,8Z,10E,14Z,17Z-eicosapentaenoic acid (12-HEPE), (±)5-hydroxy-6E,8Z,11Z,14Z-eicosatetraenoic acid (5-HETE), (±)12-hydroxy-5Z,8Z,10E,14Z-eicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE)), and deuterated internal standards 12S-hydroxy-5Z,8Z,10E,14Z-eicosatetraenoic-5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-d8 acid (12(s)-HETE-d8) were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Oxylipin concentrations were expressed in ng/mL.

The 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio was computed as a measure of auto-oxidative vs. enzymatic activation. A ratio closer to 1 indicates a more equal balance between auto-oxidation and enzymatic oxidation.

2.2.3. Antioxidants

Retinols, tocopherols, and carotenoids collected from serum samples consisted of α-carotene, β-carotene, α-tocopherol, δ-tocopherol, γ-tocopherol, β-cryptoxanthin, lutein/zeaxanthin, and lycopene. Calibrators were prepared in ethanol or hexane, and their absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically using the absorptivity coefficients provided by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). All coefficients of variation were <15%. Antioxidant concentrations were expressed in µg/mL.

The analytes were assayed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using previously published methods, validated in accordance with Food and Drug Administration guidelines, and quality assured through the NIST Micronutrient Measurement Quality Assurance Program [27].

2.2.4. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy was used to measure lipoproteins particle number and sizes (LabCorp, Morrisville, NC, USA) in serum samples analyzed by the LP4 algorithm [28]. The algorithm quantified lipoprotein subclasses of different sizes: low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles (LDLP), triglyceride-rich lipoprotein (TRL) particles (TRLP), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles (HDLP).

The HDL particle subspecies provided were H1P (diameter: 7.4 nm), H2P (7.8 nm), H3P (8.7 nm), H4P (9.5 nm), H5P (10.3 nm), H6P (10.8 nm), and H7P (12.0 nm), and were further categorized into small (H1P + H2P), medium (H3P + H4P), and large-HDLP (H5P + H6P + H7P).

In addition, the signal from glycan residues of acute-phase glycoproteins, known as GlycA, was measured as an NMR-derived biomarker of inflammation.

Lipoprotein particle diameters were presented in nm, TRLP and LDLP concentrations were expressed in nM; HDLP and GlycA concentrations were expressed in µM.

2.2.5. Apolipoproteins

Apolipoprotein (Apo), Apo-AI, Apo-AII, ApoB, ApoC-II, and ApoE, levels were measured with immunoturbidometric diagnostic reagent kits, calibrators, and quality control materials (Kamiya Biomedical, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA) as previously published [29]. Apolipoprotein concentrations were expressed in mg/dL.

2.2.6. Neurofilament Light Chain (NfL)

Serum NfL (sNfL) was measured using a single-molecule array (SIMOA) immunoassay through a collaboration with the University of Basel. sNfL concentrations are in pg/mL.

2.2.7. Cholesterol Auto-Oxidation

As a measure of cholesterol autooxidation, 7-ketocholesterol (7-KC) was measured in EDTA plasma using low-temperature saponification, solid-phase extraction, and LC-MS analysis as previously described [30]. 7-KC concentration was expressed in ng/mL.

2.2.8. Mitophagy Marker

Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B light chain 3 alpha (LC3A), a structural protein of autophagosomes, was measured in serum samples using an immunoassay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). LC3A concentration was expressed in ng/mL.

2.2.9. C-Reactive Protein

CRP was measured with the high-sensitivity assay (hs-CRP) on the ABX Pentra 400 automated chemistry analyzer (Horiba Medical, Montpellier, France).

2.3. Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted with the R (4.1.2) statistical computing program; plots were generated with the ggplot2 package.

Oxylipins, apolipoproteins, and NMR biomarkers were logarithm (base 10) transformed for regression analysis. Oxylipins were treated as predictor variables, and age, sex, BMI, and the individual biomarker measure of interest as dependent variables in the regression analysis.

The rstatix R package was used to compute the generalized eta-squared (a measure of effect size, η2) and predictor p-values from regression analyses [31]. Small, medium, or large effect sizes of η2 thresholds are ≥0.01, 0.06, and 0.14, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study groups. The PMS group had higher EDSS scores, was older, and had a longer disease duration than the RRMS group, which reflects the individualized disease courses.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study subjects.

3.2. Oxylipin Biomarkers of Lipid Peroxidation in MS

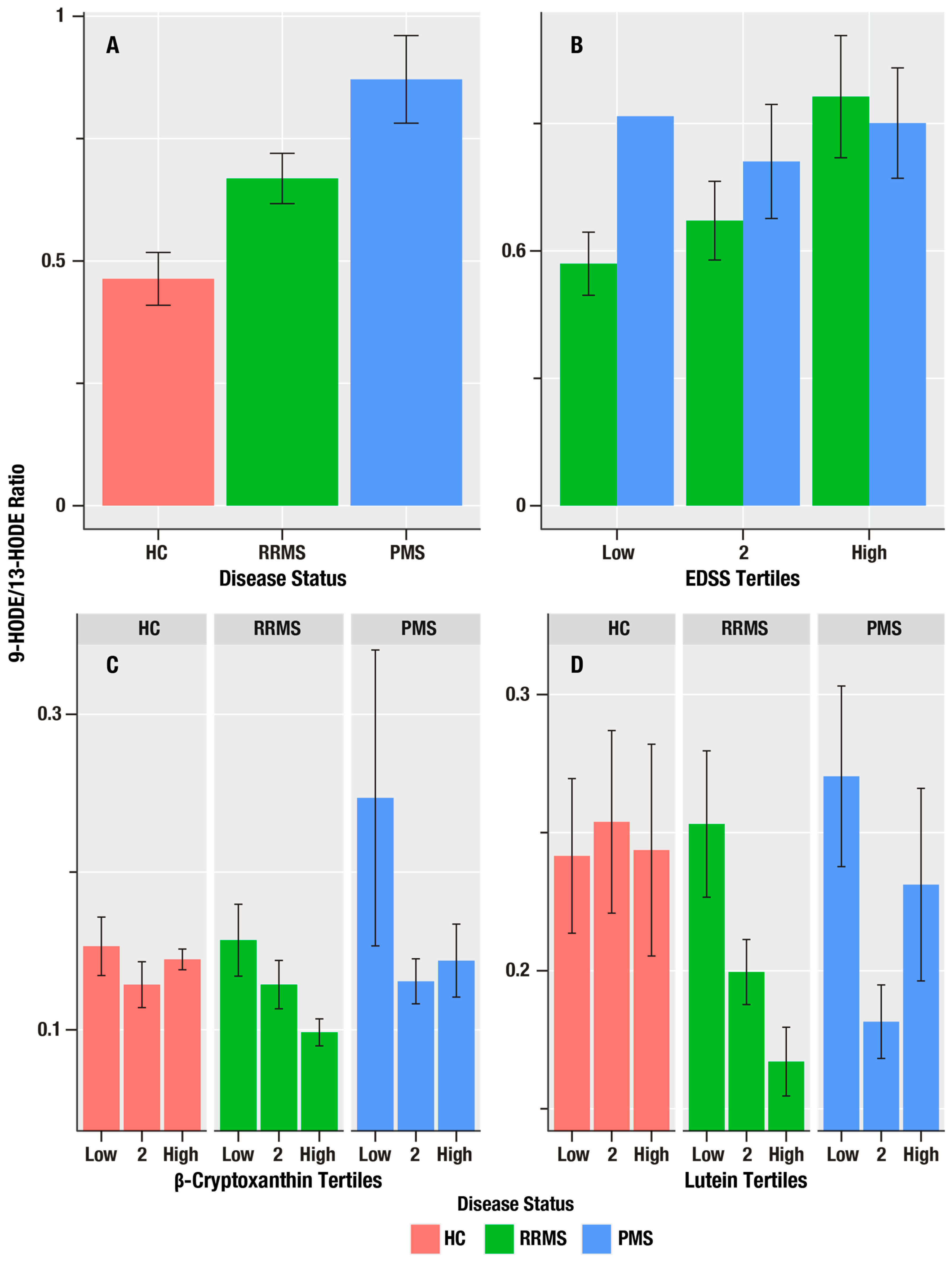

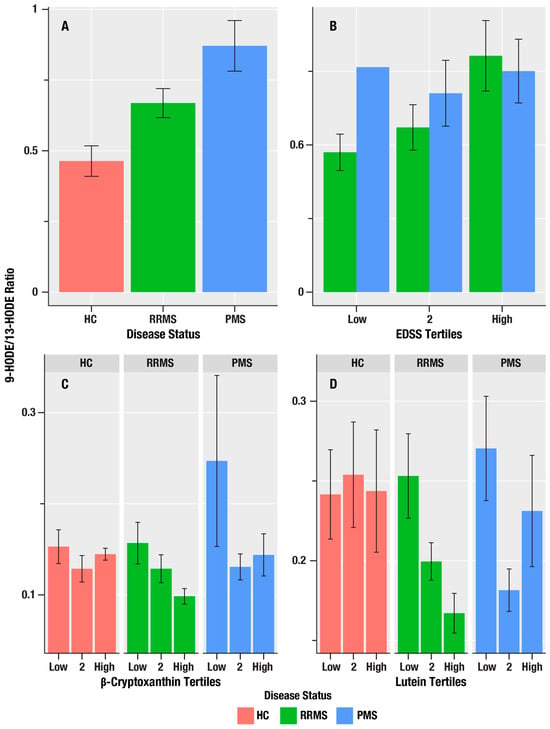

Table 2 summarizes associations of the oxylipin markers, 9-HODE, 13-HODE, 9-HpODE, 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio, 13-HOTE, 12-HEPE, 5-HETE, 12-HETE, and 12-HpETE, with markers of MS disease course (HC-RR-PMS status), disability (EDSS), and neuroaxonal injury (sNfL). The 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio, which reflects the ratio of auto-oxidation to enzymatic oxidation, was greatest in the PMS group and lowest in the HC group (i.e., in the order PMS > RR > HC), and was positively correlated with EDSS scores (β = 1.19, η2 = 0.094, p = 0.004; Figure 2). We did not obtain evidence for associations of oxylipins with sNFL.

Table 2.

Associations of oxylipins with MS disease status (HC, RR, or PMS), EDSS, and sNfL. The regression slope (β) in the RR and PMS groups (βRR and βPMS), generalized eta-squared effect size (η2), and p-value are shown.

Figure 2.

The associations of MS disease course status, disability, and antioxidant micronutrients on 9-HODE/13-HODE oxylipin ratio in HC, RR, and PMS Groups. (A) is a bar graph of the mean 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio in healthy controls (HC, salmon bars), relapsing remitting MS (RRMS, green bars), and progressive MS (PMS, blue bars). (B) shows the mean 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio (y-axis) for the lowest, middle, and highest tertiles of disability on the Expanded Disability Severity Scale (EDSS) score and the 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio in RRMS (green bars), and PMS (blue bars). (C,D) show the mean 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio (y-axis) associations for the lowest, middle, and highest tertiles of the antioxidant micronutrients, β-cryptoxanthin and lutein/zeaxanthin, in HC (salmon bars), RRMS (green bars), and PMS (blue bars). The error bars are standard errors; the p-values from the linear regression analyses are in Table 2 for (A,B), and Table 3 for (C,D).

To further corroborate the role of auto-oxidation in the associations of the 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio with the MS disease status, we assessed 7-ketocholesterol (7KC), which is known to result from cholesterol auto-oxidation. 7KC was positively associated with 9-HODE (β = 0.076, η2 = 0.051, p = 0.025) and 13-HODE (β = 0.097, η2 =0.053, p = 0.022), and its levels showed an increasing trend in the order PMS > RR > HC.

3.3. Antioxidant Micronutrients Are Associated with Lower Oxylipin Levels

Retinol, tocopherols, and carotenoids (RTC) are important fat-soluble vitamins and micronutrients with antioxidant properties that could inhibit lipid peroxidation to reduce oxylipin levels. Table 3 summarizes the regression results for the antioxidant micronutrients, α- and β-carotene, α-, γ-, and δ-tocopherol, β-cryptoxanthin, lutein/zeaxanthin, and lycopene, with oxylipins.

Table 3.

Associations of oxidized lipid products with antioxidant micronutrients. The regression slope (β), generalized eta-squared effect size (η2), and p-value are shown.

9-HODE, 13-HODE, 9-HpODE, 12-HEPE, 5-HETE, and 12-HpETE were associated with γ-tocopherol. 13-HpODE and 13-HOTE correlated with α-tocopherol.

The 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio was associated with β-cryptoxanthin (η2 = 0.040, p = 0.028) and lutein/zeaxanthin (η2 = 0.043, p = 0.023; Figure 3).

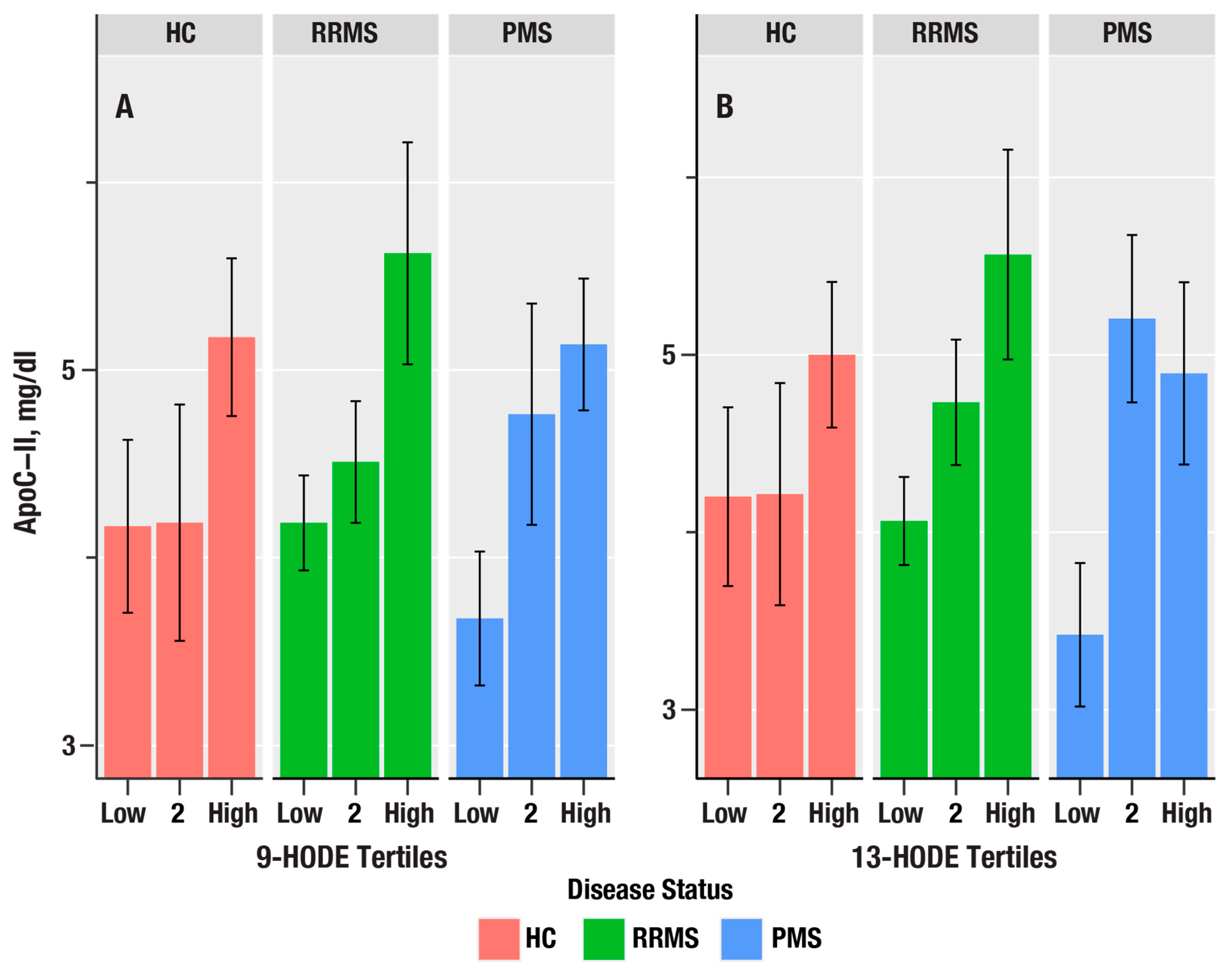

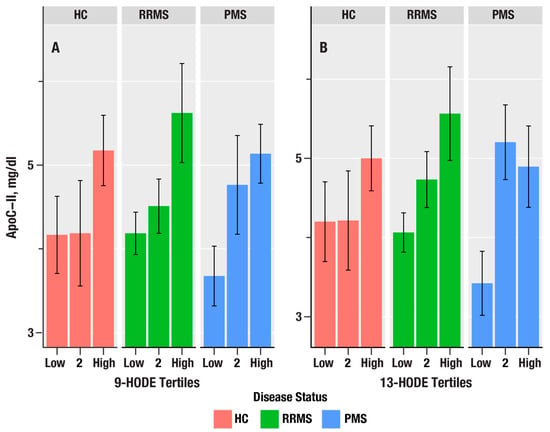

Figure 3.

The bar plots in (A,B) show the dependence of apolipoprotein C-II (ApoC-II in mg/dL) on tertiles of 9-HODE and 13-HODE in healthy controls (HC, salmon bars), relapsing remitting MS (RRMS, green bars), and progressive MS (PMS, blue bars). The bars represent mean values, and the error bars are standard errors. The p-values from linear regression are in Table 4.

3.4. Associations of Oxylipins with Lipoprotein Particle Size Subclasses

Lipoproteins are critical for the distribution of lipid peroxidation substrates, oxylipins, and diverse lipid nutrients. We examined the associations between oxylipins and lipoproteins to identify candidate lipoprotein particle size subclasses. The associations of individual oxylipins with the MS disease status (HC-RR-PMS), as estimated from regression analyses adjusted for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI), are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Associations of oxidized lipid products with triglyceride-rich lipoprotein (TRL) particle subsets. The regression slope (β), generalized eta-squared effect size (η2), and p-value are shown.

Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins: Chylomicrons, very low-density (VLDL), and intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL) comprise the triglyceride-rich lipoprotein class. Table 4 summarizes the associations between TRL particle size subsets and oxylipins. Very small TRL (VS-TRL), which correspond to IDL, were associated with 9-HODE (p < 0.001), 13-HODE (p = 0.049), 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio (p = 0.005), 12-HEPE (p = 0.046), and 5-HETE (p = 0.038).

Since triglyceride levels are increased by liver X receptor (LXR) activation, we examined the associations of oxylipins with ApoC-II, an apolipoprotein biomarker induced by LXR [32]. 9-HODE, 13-HODE, 9-HpODE, 5-HETE, and 12-HpETE were positively associated with ApoC-II and increased from PMS > RR > HC. In contrast, ApoE, which is a key apolipoprotein expressed on TRL, was not associated with any of the oxylipins.

Low-density lipoproteins: Seven of the nine oxylipins were positively correlated with overall LDL particle (LDLP) size (Table S1). 5-HETE was associated with medium LDLP.

13-HODE, 9-HpODE, 13-HpODE, 12-HEPE, 5-HETE, and 12-HpETE were positively associated with ApoB, which is the characteristic apolipoprotein of LDL (Table S1).

High-density lipoproteins: Associations with high-density lipoprotein particles (HDLP) can be found in the Supplementary Materials (Table S2). 9-HODE and 13-HODE were negatively associated with large HDLP. There were no correlations between oxylipins and ApoA-I or ApoA-II.

3.5. Association of Chronic Inflammation and Mitophagy Biomarkers

C-reactive protein (CRP) and GlycA, which are established biomarkers of chronic inflammation, were measured using high-sensitivity immunoassay and NMR spectroscopy. GlycA levels correspond to glycan modifications on proteins induced by inflammation; CRP is induced by cytokines such as interleukin-6 and interleukin-1β. CRP and GlycA were positively associated with both 9-HODE and 13-HODE (See Table 5).

Table 5.

Associations of oxidized lipid products with biomarkers of chronic inflammation, mitophagy, and autoxidation. The regression slope (β), generalized eta-squared effect size (η2), and p-value are shown.

Mitochondria are a key intracellular source of ROS. Mitophagy is an active clearance process that maintains mitochondrial homeostasis. LC3A, a structural protein of autophagosomes that is a biomarker of mitophagy, was negatively associated (See Table 5) with 9-HODE (β = −0.028, p = 0.041), 13-HODE (β = −0.049, p = 0.004), 9-HpODE (β = −0.122, p < 0.001), and 13-HpODE (β = −0.122, p < 0.001). We did not obtain evidence for an association between LC3A and the 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio in the regression analysis that adjusted for disease status. These results indicate that increased mitophagy is associated with lower auto-oxidation and oxylipin levels.

4. Discussion

We investigated the associations of oxylipins with disability, antioxidants, and lipoprotein particle subclasses in MS. We found that a high 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio was associated with HC-RRMS-PMS status and EDSS. VS-TRL particles and antioxidants, β-cryptoxanthin and lutein/zeaxanthin, were correlated with the 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio. LA-derived oxylipins were negatively associated with LC3A and positively associated with 7-KC.

A strength of our study was the availability of diverse oxylipin profiles. We utilized a sophisticated multimodal analytical strategy combining LC-MS and HPLC assays for oxylipins and antioxidant micronutrients, respectively, NMR spectroscopy for detailed lipoprotein particle analysis, and immunoassays for signaling proteins. The LC-MS and HPLC assays for oxylipins [33,34] and antioxidant micronutrients [27,35] were validated in accordance with FDA guidelines, and we have employed them in population [36], epidemiological, and clinical studies, as well as in animal experiments [37]. Likewise, our NMR spectroscopy method has been used in large clinical studies of cardiovascular disease [38]. Limitations to the study include the single-center design and modest sample size. Given the exploratory nature of the study, we did not adjust for multiple testing.

Oxidative stress is a driver of pathological processes such as mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptosis, neurodegeneration, and tissue ageing [39]. Myelin is more susceptible to oxidative stress because it is rich in PUFAs, and the brain requires substantial oxygen uptake to maintain its high metabolic rate. The presence of high levels of oxidized lipids in pre-phagocytic lesions implicates oxidative stress at the earliest steps in MS lesion formation. Oxidatively modified LDL, malondialdehyde, and 4-hydroxynonenal, which are important, toxic products of lipid peroxidation, are prominent in early and actively demyelinating MS lesions [40]. Oxidative injury to oligodendrocytes and neurons occurs during demyelination and axonal injury in MS [41]. Plasma biomarkers, including plasma fluorescent lipid peroxidation products [42,43], total conjugated dienes [44], antibodies to oxidized LDL, [45] and F2-isoprostanes, [46,47,48] are also increased in MS. There is, however, a significant knowledge gap in our understanding of the mechanisms causing lipid peroxidation and the role of antioxidants in MS, due to the lack of integrated data on both primary oxidatively damaged products and antioxidant factors.

Hakansson et al. found higher CSF levels of 9-HODE and 13-HODE in MS patients compared to healthy controls, but did not find evidence for prognostic associations with disease activity at 2 or 4 years [49]. Auto-oxidation of linoleic acid by reactive oxygen species free radicals tends to be nonspecific and produces nearly equal amounts of 9-HODE and 13-HODE, resulting in a 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio of approximately 1. Enzymatic oxidation of linoleic acid by cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 and COX-2 enzymes predominantly results in 9-HODE; COX-1 and COX-2 also catalyze the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins. 13-HODE is the major product when linoleic acid is oxidized by 15-LOX-1; however, 15-LOX-2, COX-1, COX-2, and cytochrome P450 enzymes produce 13-HODE from linoleic acid. Thus, COX activities, which favor the production of 9-HODE, shift the 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio to greater than 1, and the LOX activities shift the 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio to less than 1. A higher 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio is indicative of auto-oxidation and unregulated lipid peroxidation, whereas a lower ratio is indicative of more balanced or controlled lipid metabolism via enzymatic pathways. While we did not obtain evidence for associations of oxylipins with WBV or LVV , baseline 9-HODE has been reported to be associated with greater white matter and thalamic neurodegeneration in RRMS [50].

Natural carotenoids have emerged as promising antioxidant agents to counteract redox and inflammatory cascades in MS [51]. A randomized, prospective study of 88 RRMS patients demonstrated that increased α-tocopherol intake reduced the odds for new and subsequent T2- and T1-lesions [52]. Higher intake of antioxidants did not reduce the risk of MS in females [53], or improve cognitive function [54]; however, the impact on oxylipins in MS has not been investigated.

We measured LC3A to assess the effect of oxylipins on autophagy and selective mitophagy and found that greater 9-HODE and 13-HODE levels were associated with lower LC3A levels. The conjugation of phosphatidylethanolamine to cytosolic LC3 or LC3-I results in the membrane-bound form, LC3-II (LC3-PE). Lipid peroxidation stimulates the preferential removal of oxidized LC3-PE by autophagy-related (ATG) protein-4, which inhibits autophagy [55]. ATG protein activity has been reported to be decreased in post-mortem human MS brain tissue [56]. Additionally, LC3A selectively binds externalized cardiolipin on the outer mitochondrial membrane of oxidatively damaged mitochondria to nucleate the formation of an autophagosome that triggers mitophagy [57]. Reduced mitophagy in the presence of oxylipins could lead to the buildup of damaged mitochondria, which might promote inflammation. To our knowledge, LC3A levels in MS patient samples have not been extensively investigated.

5. Conclusions

The 9-HODE/13-HODE ratio may be a useful biomarker in the assessment of MS. Targeted interventional therapies aimed at reducing auto-oxidation may improve disability progression and decrease chronic inflammation; however, further research is necessary to validate their effects, if any, on MS outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antiox15010102/s1. Table S1. Associations of oxidized lipid products with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particle subsets. Table S2. Associations of oxidized lipid products with high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particle distributions. Figure S1. Figures (A,B) show the associations of the cholesterol autoxidation product 7-ketocholesterol for the lowest, middle, and highest tertiles of 9-HODE and 13-HODE, respectively, in HC (salmon bars), RRMS (green bars), and PMS (blue bars).

Author Contributions

T.R.W., A.W.—Data analysis, manuscript preparation. D.G.—Data analysis. R.W.B.—Data analysis, manuscript preparation. I.S.—Data analysis, manuscript preparation. B.W.-G., R.Z., A.T.R.—Manuscript preparation. M.R.—Study concept and design, data analysis, manuscript preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Award MS190096 from the Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs, USAMRDC, Multiple Sclerosis Research Program. The underlying clinical studies were funded by the Annette Funicello Research Fund for Neurological Diseases, Jacquemin Family Foundation, and private donations to the Buffalo Neuroimaging Analysis Center, Department of Neurology, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, Buffalo, NY. The funders had no role in the study’s design or data analysis.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the University at Buffalo Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (MODCR00009015, 1 July 2014).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the principal investigator of the clinical study (Dr. Robert Zivadinov). The data are not publicly available due to containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgments

We express our profound gratitude to the patients and caregivers whose invaluable participation and contributions have been vital to our MS research. Use of Artificial Intelligence: Artificial intelligence-enabled tools, such as Grammarly (v1.143), ChatGPT (v5.o), and Microsoft Word (v16), were utilized to enhance readability and language clarity. Additionally, AI-enabled tools such as Google and EndNote were used to collect and curate references, add citations, and generate the bibliography.

Conflicts of Interest

Irina A. Shalaurova is an employee of LabCorp. Authors Anna Wolska and Alan T. Remaley are employed by the National Institute of Health. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. This publication is solely the work of the authors and should not be interpreted to represent the views, perspectives, or policies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, or the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

References

- McGinley, M.P.; Goldschmidt, C.H.; Rae-Grant, A.D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. JAMA 2021, 325, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakimovski, D.; Bittner, S.; Zivadinov, R.; Morrow, S.A.; Benedict, R.H.; Zipp, F.; Weinstock-Guttman, B. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2024, 403, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, T.T. Lipid peroxidation and neurodegenerative disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 1302-1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, T.; Shimizu, K.; Hirano, K.; Nakashima, F.; Kikuchi, R.; Matsushita, T.; Uchida, K. Adductome-based identification of biomarkers for lipid peroxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 8223–8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Sun, J.; Luo, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y. Emerging mechanisms of lipid peroxidation in regulated cell death and its physiological implications. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochette, L.; Dogon, G.; Rigal, E.; Zeller, M.; Cottin, Y.; Vergely, C. Lipid Peroxidation and Iron Metabolism: Two Corner Stones in the Homeostasis Control of Ferroptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, D.C.P.; Halligan, S.L.; Davey Smith, G.; Khandaker, G.M.; Jones, H.J. The relationship between polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammation: Evidence from cohort and Mendelian randomization analyses. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2025, 54, dyaf065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djuricic, I.; Calder, P.C. Beneficial Outcomes of Omega-6 and Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Human Health: An Update for 2021. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baarnhielm, M.; Olsson, T.; Alfredsson, L. Fatty fish intake is associated with decreased occurrence of multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 2014, 20, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinek, G.A.; Hadgkiss, E.J.; Weiland, T.J.; Pereira, N.G.; Marck, C.H.; van der Meer, D.M. Association of fish consumption and Omega 3 supplementation with quality of life, disability and disease activity in an international cohort of people with multiple sclerosis. Int. J. Neurosci. 2013, 123, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaeizadeh, H.; Mohammadpour, Z.; Bitarafan, S.; Harirchian, M.H.; Ghadimi, M.; Homayon, I.A. Dietary fish intake and the risk of multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedstrom, A.K.; Olsson, T.; Kockum, I.; Hillert, J.; Alfredsson, L. Low fish consumption is associated with a small increased risk of MS. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm 2020, 7, e717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, E.; Guo, J.; Wu, J.; Olsson, T.; Alfredsson, L.; Hedstrom, A.K. Impact of fish consumption on disability progression in multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2025, 96, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAmmar, W.A.; Albeesh, F.H.; Ibrahim, L.M.; Algindan, Y.Y.; Yamani, L.Z.; Khattab, R.Y. Effect of omega-3 fatty acids and fish oil supplementation on multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matveeva, O.; Bogie, J.F.J.; Hendriks, J.J.A.; Linker, R.A.; Haghikia, A.; Kleinewietfeld, M. Western lifestyle and immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1417, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innes, J.K.; Calder, P.C. Omega-6 fatty acids and inflammation. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2018, 132, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aristotelous, P.; Stefanakis, M.; Pantzaris, M.; Pattichis, C.S.; Calder, P.C.; Patrikios, I.S.; Sakkas, G.K.; Giannaki, C.D. The Effects of Specific Omega-3 and Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Antioxidant Vitamins on Gait and Functional Capacity Parameters in Patients with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, E.; Daly, A.; Mori, T.A.; Langer-Gould, A.; Pereira, G.; Black, L.J. Plasma levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids and multiple sclerosis susceptibility in a US case-control study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 92, 105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkildsen, O.; Wergeland, S.; Bakke, S.; Beiske, A.G.; Bjerve, K.S.; Hovdal, H.; Midgard, R.; Lilleas, F.; Pedersen, T.; Bjornara, B.; et al. omega-3 fatty acid treatment in multiple sclerosis (OFAMS Study): A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch. Neurol. 2012, 69, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, L.R.; Dworkin, R.H.; Schwid, S.R. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their potential therapeutic role in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2009, 5, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock-Guttman, B.; Baier, M.; Park, Y.; Feichter, J.; Lee-Kwen, P.; Gallagher, E.; Venkatraman, J.; Meksawan, K.; Deinehert, S.; Pendergast, D.; et al. Low fat dietary intervention with omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in multiple sclerosis patients. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2005, 73, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruschil, C.; Dubois, E.; Stefanou, M.I.; Kowarik, M.C.; Ziemann, U.; Schittenhelm, M.; Krumbholz, M.; Bischof, F. Treatment of progressive multiple sclerosis with high-dose all-trans retinoic acid—No clear evidence of positive disease modifying effects. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2021, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, N.G.; Rose, J.W. Antioxidants in multiple sclerosis: Do they have a role in therapy? CNS Drugs 2006, 20, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegoretti, V.; Swanson, K.A.; Bethea, J.R.; Probert, L.; Eisel, U.L.M.; Fischer, R. Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Multiple Sclerosis: Consequences for Therapy Development. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 7191080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohl, K.; Tenbrock, K.; Kipp, M. Oxidative stress in multiple sclerosis: Central and peripheral mode of action. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 277, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Browne, R.W.; Blair, R.H.; Bonner, M.R.; Tian, M.; Niu, Z.; Deng, F.; Farhat, Z.; Mu, L. Changes in arachidonic acid (AA)- and linoleic acid (LA)-derived hydroxy metabolites and their interplay with inflammatory biomarkers in response to drastic changes in air pollution exposure. Environ. Res. 2021, 200, 111401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, R.W.; Armstrong, D. Simultaneous determination of serum retinol, tocopherols, and carotenoids by HPLC. Methods Mol. Biol. 1998, 108, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otvos, J.D.; Collins, D.; Freedman, D.S.; Shalaurova, I.; Schaefer, E.J.; McNamara, J.R.; Bloomfield, H.E.; Robins, S.J. Low-density lipoprotein and high-density lipoprotein particle subclasses predict coronary events and are favorably changed by gemfibrozil therapy in the Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention Trial. Circulation 2006, 113, 1556–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, R.W.; Weinstock-Guttman, B.; Horakova, D.; Zivadinov, R.; Bodziak, M.L.; Tamaño-Blanco, M.; Badgett, D.; Tyblova, M.; Vaneckova, M.; Seidl, Z.; et al. Apolipoproteins are associated with new MRI lesions and deep grey matter atrophy in clinically isolated syndromes. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2014, 85, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanaswamy, R.; Iyer, V.; Khare, P.; Bodziak, M.L.; Badgett, D.; Zivadinov, R.; Weinstock-Guttman, B.; Rideout, T.C.; Ramanathan, M.; Browne, R.W. Simultaneous determination of oxysterols, cholesterol and 25-hydroxy-vitamin D3 in human plasma by LC-UV-MS. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassambara, A. rstatix: Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rstatix/index.html (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Wolska, A.; Dunbar, R.L.; Freeman, L.A.; Ueda, M.; Amar, M.J.; Sviridov, D.O.; Remaley, A.T. Apolipoprotein C-II: New findings related to genetics, biochemistry, and role in triglyceride metabolism. Atherosclerosis 2017, 267, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, R.W.; Armstrong, D. Simultaneous determination of polyunsaturated fatty acids and corresponding monohydroperoxy and monohydroxy peroxidation products by HPLC. Methods Mol. Biol. 2002, 186, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, R.W.; Armstrong, D. HPLC analysis of lipid-derived polyunsaturated fatty acid peroxidation products in oxidatively modified human plasma. Clin. Chem. 2000, 46, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, R.W.; Armstrong, D. Reduced glutathione and glutathione disulfide. Methods Mol. Biol. 1998, 108, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, M.; Browne, R.; Ram, M.; Muti, P.; Freudenheim, J.; Carosella, A.M.; Armstrong, D. Correlates of markers of oxidative status in the general population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 154, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rideout, T.C.; Carrier, B.; Wen, S.; Raslawsky, A.; Browne, R.W.; Harding, S.V. Complementary Cholesterol-Lowering Response of a Phytosterol/alpha-Lipoic Acid Combination in Obese Zucker Rats. J. Diet. Suppl. 2016, 13, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otvos, J.D.; Shalaurova, I.; May, H.T.; Muhlestein, J.B.; Wilkins, J.T.; McGarrah, R.W., 3rd; Kraus, W.E. Multimarkers of metabolic malnutrition and inflammation and their association with mortality risk in cardiac catheterisation patients: A prospective, longitudinal, observational, cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023, 4, e72–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan, K.; Jain, S.K. Oxidative stress and apoptosis. Pathophysiol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Pathophysiol. 2000, 7, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, J.; Li, H.; Cuzner, M.L. Low density lipoprotein uptake by macrophages in multiple sclerosis plaques: Implications for pathogenesis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1994, 20, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, L.; Fischer, M.T.; Frischer, J.M.; Bauer, J.; Hoftberger, R.; Botond, G.; Esterbauer, H.; Binder, C.J.; Witztum, J.L.; Lassmann, H. Oxidative damage in multiple sclerosis lesions. Brain A J. Neurol. 2011, 134, 1914–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, R.; Knapp, M.L. Studies of lipid peroxidation products in cerebrospinal fluid and serum in multiple sclerosis and other conditions. Clin. Chem. 1992, 38, 2449–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Mostert, J.; Arutjunyan, A.; Stepanov, M.; Teelken, A.; Heersema, D.; De Keyser, J. Peripheral blood leukocyte NO production and oxidative stress in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 2008, 14, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallaur, A.P.; Reiche, E.M.; Oliveira, S.R.; Simao, A.N.; Pereira, W.L.; Alfieri, D.F.; Flauzino, T.; Proenca, C.M.; Lozovoy, M.A.; Kaimen-Maciel, D.R.; et al. Genetic, Immune-Inflammatory, and Oxidative Stress Biomarkers as Predictors for Disability and Disease Progression in Multiple Sclerosis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gironi, M.; Borgiani, B.; Mariani, E.; Cursano, C.; Mendozzi, L.; Cavarretta, R.; Saresella, M.; Clerici, M.; Comi, G.; Rovaris, M.; et al. Oxidative stress is differentially present in multiple sclerosis courses, early evident, and unrelated to treatment. J. Immunol. Res. 2014, 2014, 961863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; Mrowicka, M.; Saluk-Juszczak, J.; Ireneusz, M. The level of isoprostanes as a non-invasive marker for in vivo lipid peroxidation in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurochem. Res. 2011, 36, 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, A.; Minghetti, L.; Sette, G.; Fieschi, C.; Levi, G. Cerebrospinal fluid isoprostane shows oxidative stress in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1999, 53, 1876–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartova, R.; Petrlenicova, D.; Oresanska, K.; Prochazkova, L.; Liska, B.; Turecky, L.; Durfinova, M. Changes in levels of oxidative stress markers and some neuronal enzyme activities in cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis patients. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2016, 37, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hakansson, I.; Gouveia-Figueira, S.; Ernerudh, J.; Vrethem, M.; Ghafouri, N.; Ghafouri, B.; Nording, M. Oxylipins in cerebrospinal fluid in clinically isolated syndrome and relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2018, 138, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, W.H.; van Lingen, M.R.; Broos, J.Y.; Lam, K.H.; van Dam, M.; Fung, W.K.; Noteboom, S.; Koubiyr, I.; de Vries, H.E.; Jasperse, B.; et al. 9-HODE associates with thalamic atrophy and predicts white matter damage in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 92, 105946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadimi, E.; Jamal Omidi, S.; Ghasemi, M.; Hashempur, M.H.; Iraji, A. Carotenoids as neuroprotective agents in multiple sclerosis: Pathways, mechanisms, and clinical prospects. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 191, 118496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loken-Amsrud, K.I.; Myhr, K.M.; Bakke, S.J.; Beiske, A.G.; Bjerve, K.S.; Bjornara, B.T.; Hovdal, H.; Lilleas, F.; Midgard, R.; Pedersen, T.; et al. Alpha-tocopherol and MRI outcomes in multiple sclerosis--association and prediction. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.M.; Hernan, M.A.; Olek, M.J.; Spiegelman, D.; Willett, W.C.; Ascherio, A. Intakes of carotenoids, vitamin C, and vitamin E and MS risk among two large cohorts of women. Neurology 2001, 57, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martell, S.G.; Kim, J.; Cannavale, C.N.; Mehta, T.D.; Erdman, J.W., Jr.; Adamson, B.; Motl, R.W.; Khan, N.A. Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Single-Blind Study of Lutein Supplementation on Carotenoid Status and Cognition in Persons with Multiple Sclerosis. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 2298–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Luo, L.X.; Zhou, Q.Q.; Gong, H.B.; Fu, Y.Y.; Yan, C.Y.; Li, E.; Sun, J.; Luo, Z.; Ding, Z.J.; et al. Phospholipid peroxidation inhibits autophagy via stimulating the delipidation of oxidized LC3-PE. Redox Biol. 2022, 55, 102421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misrielal, C.; Alsema, A.M.; Wijering, M.H.C.; Miedema, A.; Mauthe, M.; Reggiori, F.; Eggen, B.J.L. Transcriptomic changes in autophagy-related genes are inversely correlated with inflammation and are associated with multiple sclerosis lesion pathology. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2022, 25, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriondo, M.N.; Etxaniz, A.; Varela, Y.R.; Ballesteros, U.; Hervas, J.H.; Montes, L.R.; Goni, F.M.; Alonso, A. LC3 subfamily in cardiolipin-mediated mitophagy: A comparison of the LC3A, LC3B and LC3C homologs. Autophagy 2022, 18, 2985–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.