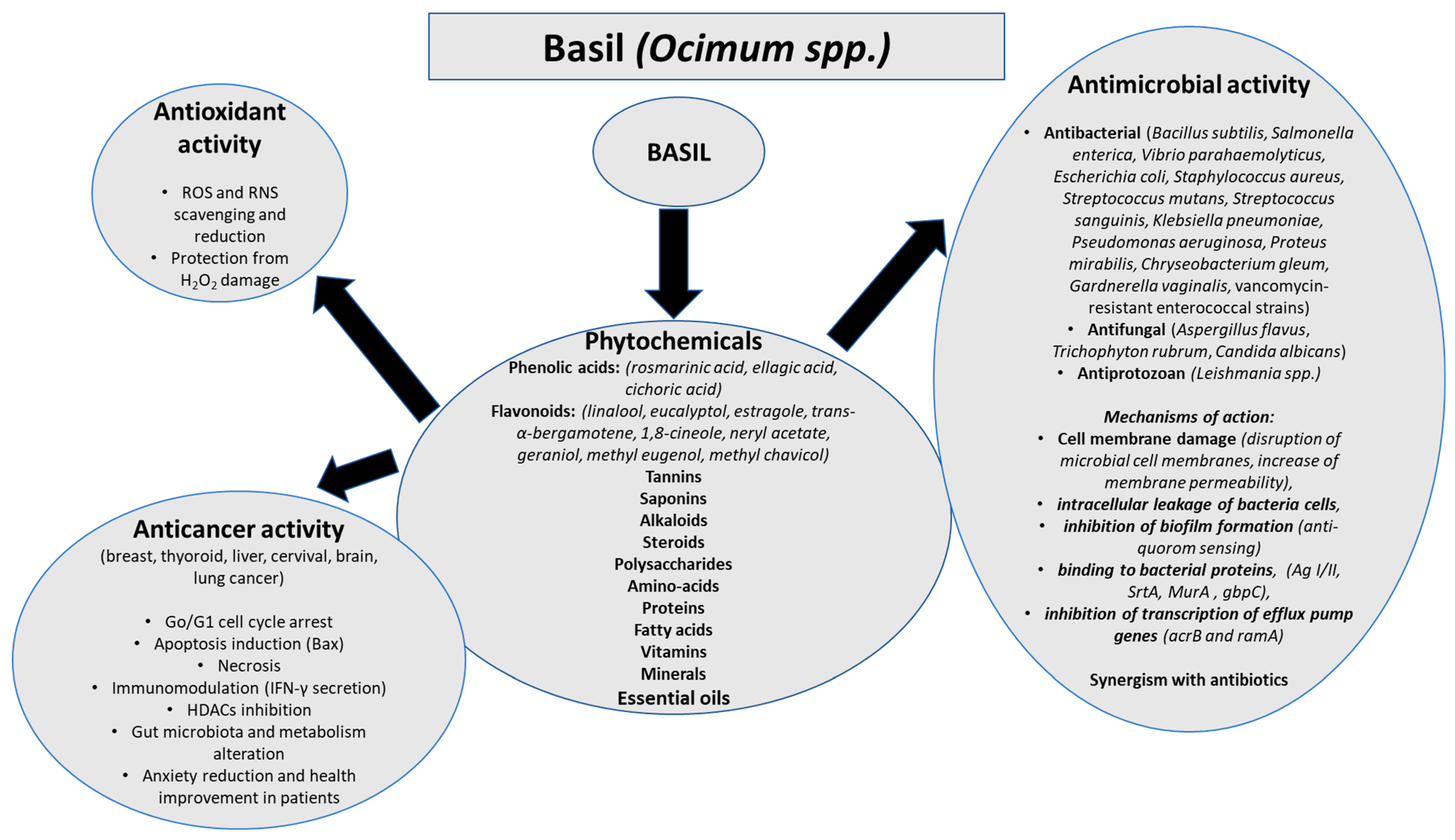

Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Anticancer Activity of Basil (Ocimum basilicum)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Antioxidant Activity of Basil

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity of Basil

3.3. Anticancer Activity of Basil

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAPH | azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride |

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid |

| ADME | absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion |

| ADMET | absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity |

| AMP | adenosine monophosphate |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| APCI | antioxidant potential composite index |

| CAT | catalase |

| CCI4 | carbon tetrachloride |

| DAD | diode-array detector |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| DTC | differentiated thyroid cancer |

| DW | dry weight |

| EC50 | half maximal effective concentration |

| EGFR-TKIs | epidermal growth factor receptor–tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| Eos | essential oils |

| ESI-HR-MS/MS | electrospray ionization–high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry |

| FIC | fractional inhibitory concentration |

| FRAP | ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) |

| GAE | gallic acid equivalent |

| GC-MS | gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| GPX | glutathione peroxidase |

| GR | glutathione reductase |

| Grx | glutaredoxin |

| GS | growth stage |

| GSH | reduced glutathione |

| HAT | histone acetyltransferases |

| HDAC | histone deacetylases |

| HDF | high-fat diet |

| HO• | hydroxyl radical |

| HPLC-DAD/ESI-ToF-MS | high-performance liquid chromatography diode-array detector/electrospray ionization time-of-flight |

| HPV | human papillomavirus |

| HS-SPME | headspace solid-phase microextraction |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| IC50 | inhibitory concentration 50 |

| Ig | immunoglobulin |

| LC-ESI-MS/MS | liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry |

| LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS | liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization-quadrupole time-of-flight-mass spectrometry |

| LC50 | lethal concentration 50 |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MBC | minimum bactericidal concentration |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| MDR | multidrug-resistance |

| MFC | minimum fungicidal concentration |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MS | mass spectrometry |

| MTCC | microbial type culture collection |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-di methyl thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| NF-kB | nuclear factor kappa-b |

| O2.− | superoxide anion |

| ORAC | oxygen radical absorbance capacity |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| PLA2 | phospholipase A2 |

| QE | quercetin equivalent |

| qPCR | quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| QSAR | quantitative structure-activity relationship |

| RAIT | radioactive iodine therapy |

| RE | rutin equivalent |

| RNS | reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RT-PCR | reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| STAI | state anxiety and trait anxiety |

| TAC | total antioxidant capacity |

| TBARS | thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| TFC | total flavonoid content |

| TLRC | thin-layer radio chromatography |

| TPC | total phenolic content |

| Trx | thioredoxin |

| TTT | total tannin content |

| UPLC | ultra-performance liquid chromatography |

| VRE | vancomycin-resistant |

References

- Grigore-Gurgu, L.; Dumitrașcu, L.; Aprodu, I. Aromatic Herbs as a Source of Bioactive Compounds: An Overview of Their Antioxidant Capacity, Antimicrobial Activity, and Major Applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.A. Health Benefits of Culinary Herbs and Spices. J. AOAC Int. 2019, 102, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerriero, G.; Berni, R.; Muñoz-Sanchez, J.A.; Apone, F.; Abdel-Salam, E.M.; Qahtan, A.A.; Alatar, A.A.; Cantini, C.; Cai, G.; Hausman, J.F.; et al. Production of Plant Secondary Metabolites: Examples, Tips and Suggestions for Biotechnologists. Genes 2018, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monjotin, N.; Amiot, M.J.; Fleurentin, J.; Morel, J.M.; Raynal, S. Clinical Evidence of the Benefits of Phytonutrients in Human Healthcare. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, E.; Giaginis, C.; Vasios, G.K. Current Advances on the Extraction and Identification of Bioactive Components of Sage (Salvia spp.). Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2019, 20, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolella, S.; Crescente, G.; Candela, L.; Pacifico, S. Nutraceutical polyphenols: New analytical challenges and opportunities. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 175, 112774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulios, E.; Giaginis, C.; Vasios, G.K. Current State of the Art on the Antioxidant Activity of Sage (Salvia spp.) and Its Bioactive Components. Planta. Med. 2020, 86, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, E.; Vasios, G.K.; Psara, E.; Antasouras, G.; Gialeli, M.; Pavlidou, E.; Tsantili-Kakoulidou, A.; Troumbis, A.Y.; Giaginis, C. Antioxidant Activity of Medicinal Plants and Herbs of North Aegean, Greece: Current Clinical Evidence and Future Perspectives. Nat. Prod. J. 2024, 14, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, K.B.; Bhat, A.H.; Amin, S.; Masood, A.; Zargar, M.A.; Ganie, S.A. Inflammation: A Multidimensional Insight on Natural Anti-Inflammatory Therapeutic Compounds. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 3775–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, B.; Elbarbry, F.; Bui, F.; Su, J.W.; Seo, K.; Nguyen, A.; Lee, M.; Rao, D.A. Mechanistic Basis for the Role of Phytochemicals in Inflammation-Associated Chronic Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J.; Vengalasetti, Y.V.; Bredesen, D.E.; Rao, R.V. Neuroprotective Herbs for the Management of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoi, M.; Maruyama, W.; Shamoto-Nagai, M. Disease-modifying treatment of Parkinson’s disease by phytochemicals: Targeting multiple pathogenic factors. J. Neural. Transm. 2022, 129, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Mittal, A.; Babu, D.; Mittal, A. Herbal Medicines for Diabetes Management and its Secondary Complications. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2021, 17, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Džamić, A.M.; Matejić, J.S. Plant Products in the Prevention of Diabetes Mellitus. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 1395–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrysant, S.G.; Chrysant, G.S. Herbs Used for the Treatment of Hypertension and their Mechanism of Action. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2017, 19, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamyab, R.; Namdar, H.; Torbati, M.; Ghojazadeh, M.; Araj-Khodaei, M.; Fazljou, S.M.B. Medicinal Plants in the Treatment of Hypertension: A Review. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 11, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.; Majeed, F.; Taleb, A.; Zubair, H.M.; Shumzaid, M.; Farooq, M.A.; Baig, M.M.F.A.; Abbas, M.; Saeed, M.; Changxing, L. A Review of Medicinal Plants in Cardiovascular Disorders: Benefits and Risks. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2020, 48, 259–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saqib, U.; Khan, M.A.; Alagumuthu, M.; Parihar, S.P.; Baig, M.S. Natural compounds as antiatherogenic agents. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2021, 67, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, E.; Vasios, G.K.; Psara, E.; Giaginis, C. Medicinal plants consumption against urinary tract infections: A narrative review of the current evidence. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2021, 19, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marouf, R.S.; Mbarga, J.A.M.; Ermolaev, A.V.; Podoprigora, I.V.; Smirnova, I.P.; Yashina, N.V.; Zhigunova, A.V.; Martynenkova, A.V. Antibacterial Activity of Medicinal Plants against Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Pharm. Bioallied. Sci. 2022, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, X.Y.; The, B.P.; Tan, T.Y.C. Medicinal Plants in COVID-19: Potential and Limitations. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 611408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, V.P.; Patel, A.B.; Vihol, D.; Vaghasiya, D.D.; Ahmed, K.M.S.B.; Trivedi, K.U.; Dave, D.J. Herbal Remedies, Nutraceuticals, and Dietary Supplements for COVID-19 Management: An Update. Clin. Complement. Med. Pharmacol. 2022, 2, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, R.; Marzabadi, L.R.; Arjmand, B.; Ayati, M.H.; Namazi, N. The effects of medicinal herbs on gut microbiota and metabolic factors in obesity models: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2022, 16, 102586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, E.; Koukounari, S.; Psara, E.; Vasios, G.K.; Sakarikou, C.; Giaginis, C. Anti-obesity Properties of Phytochemicals: Highlighting their Molecular Mechanisms against Obesity. Curr. Med. Chem. 2024, 31, 25–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aba, P.E.; Ihedioha, J.I.; Asuzu, I.U. A review of the mechanisms of anti-cancer activities of some medicinal plants-biochemical perspectives. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 34, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Jin, J.; Zhao, D.; Rong, Z.; Cao, L.Q.; Li, A.H.; Sun, X.Y.; Jia, L.Y.; Wang, Y.D.; Huang, L.; et al. Research Advances on Anti-Cancer Natural Products. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 866154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.A.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The Chemistry of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Revisited: Outlining Their Role in Biological Macromolecules (DNA, Lipids and Proteins) and Induced Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, Z.; Bansal, R.; Siddiqui, L.; Chaudhary, N. Understanding the Role of Free Radicals and Antioxidant Enzymes in Human Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2023, 24, 1265–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Pan, X.; Wei, G.; Hua, Y. Research progress of glutathione peroxidase family (GPX) in redoxidation. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1147414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, E.; Roupaka, V.; Giaginis, C.; Galaris, D.; Spyrou, G. Implication of Thioredoxin 1 and Glutaredoxin 1 in H2O2-induced Phosphorylation of JNK and p38 MAP Kinases. Curr. Mol. Med. 2025, 25, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanschmann, E.M.; Godoy, J.R.; Berndt, C.; Hudemann, C.; Lillig, C.H. Thioredoxins, glutaredoxins, and peroxiredoxins--molecular mechanisms and health significance: From cofactors to antioxidants to redox signaling. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2013, 19, 1539–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulewicz-Magulska, B.; Wesolowski, M. Total Phenolic Contents and Antioxidant Potential of Herbs Used for Medical and Culinary Purposes. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2019, 74, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayaz, M.; Ullah, F.; Sadiq, A.; Ullah, F.; Ovais, M.; Ahmed, J.; Devkota, H.P. Synergistic interactions of phytochemicals with antimicrobial agents: Potential strategy to counteract drug resistance. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019, 308, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, A.; Hu, P.; Yang, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zheng, Q. Natural Products as Anticancer Agents: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27, 8367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilina, G.; Sabitova, A.; Idrisheva, Z.; Zhumabekova, A.; Kanapiyeva, F.; Orynbassar, R.; Zhamanbayeva, M.; Kamalova, M.; Assilbayeva, J.; Turgumbayeva, A.; et al. Bio-active compounds and major biomedical properties of basil (Ocimum basilicum, lamiaceae). Nat. Prod. Res. 2025, 39, 1326–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizah, N.S.; Irawan, B.; Kusmoro, J.; Safriansyah, W.; Farabi, K.; Oktavia, D.; Doni, F.; Miranti, M. Sweet Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.)-A Review of Its Botany, Phytochemistry, Pharmacological Activities, and Biotechnological Development. Plants 2023, 12, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; An, X.; Wang, S.; Sun, M.; Zhou, H. Basil polysaccharides: A review on extraction, bioactivities and pharmacological applications. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón Bravo, H.; Vera Céspedes, N.; Zura-Bravo, L.; Muñoz, L.A. Basil Seeds as a Novel Food, Source of Nutrients and Functional Ingredients with Beneficial Properties: A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhakipbekov, K.; Turgumbayeva, A.; Akhelova, S.; Bekmuratova, K.; Blinova, O.; Utegenova, G.; Shertaeva, K.; Sadykov, N.; Tastambek, K.; Saginbazarova, A.; et al. Antimicrobial and Other Pharmacological Properties of Ocimum basilicum, Lamiaceae. Molecules 2024, 29, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, N.; Taleuzzaman, M.; Hudda, S.; Choudhary, N. In Vitro Antioxidant and Antifungal Activities of Extracts from Ocimum basilicum Leaves Validated by Molecular Docking and ADMET Analysis. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202401969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójciak, M.; Paduch, R.; Drozdowski, P.; Żuk, M.; Wójciak, W.; Tyszczuk-Rotko, K.; Feldo, M.; Sowa, I. Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry Characterization, and Antioxidant, Protective, and Anti-Inflammatory Activity, of the Polyphenolic Fraction from Ocimum basilicum. Molecules 2024, 29, 5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, H.R.; Akhtar, S.; Sestili, P.; Ismail, T.; Neugart, S.; Qamar, M.; Esatbeyoglu, T. Toxicity, Antioxidant Activity, and Phytochemicals of Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) Leaves Cultivated in Southern Punjab, Pakistan. Foods 2022, 11, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidaković, V.; Vujić, B.; Jadranin, M.; Novaković, I.; Trifunović, S.; Tešević, V.; Mandić, B. Qualitative Profiling, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Polar and Nonpolar Basil Extracts. Foods 2024, 13, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Razakh, H.H.; Bakari, G.G.; Park, J.S.; Pan, C.H.; Hoza, A.S. Phenolic Contents and Antioxidant Properties of Bauhinia rufescens, Ocimum basilicum and Salvadora persica, Used as Medicinal Plants in Chad. Molecules 2024, 29, 4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, E.; Starowicz, M.; Ciska, E.; Topolska, J.; Farouk, A. Determination of volatiles, antioxidant activity, and polyphenol content in the postharvest waste of Ocimum basilicum L. Food Chem. 2022, 375, 131692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, F.; Sana, A.; Naveed, S.; Faizi, S. Phytochemical characterization, antioxidant activity and antihypertensive evaluation of Ocimum basilicum L. in l-NAME induced hypertensive rats and its correlation analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siripongvutikorn, S.; Pumethakul, K.; Yupanqui, C.T.; Seechamnanturakit, V.; Detarun, P.; Utaipan, T.; Sirinupong, N.; Chansuwan, W.; Wittaya, T.; Samakradhamrongthai, R.S. Phytochemical Profiling and Antioxidant Activities of the Most Favored Ready-to-Use Thai Curries, Pad-Ka-Proa (Spicy Basil Leaves) and Massaman. Foods 2024, 13, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Złotek, U.; Mikulska, S.; Nagajek, M.; Świeca, M. The effect of different solvents and number of extraction steps on the polyphenol content and antioxidant capacity of basil leaves (Ocimum basilicum L.) extracts. Saudi. J. Biol. Sci. 2016, 23, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.; Chaurasia, H.; Verma, S.; Gupta, S.; Chauhan, V.; Wal, A. Basil (Ocimum basilicum): A Natural Approach to Skin Care and Its Cosmeceutical Potential. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yibeltal, G.; Yusuf, Z.; Desta, M. Physicochemical Properties, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Ethiopian Sweet Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) Leaf and Flower Oil Extracts. Recent Adv. Antiinfect. Drug Discov. 2022, 17, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, A.M.; Jaradat, N.; Shraim, N.; Hawash, M.; Issa, L.; Shakhsher, M.; Nawahda, N.; Hanbali, A.; Barahmeh, N.; Taha, B.; et al. Assessment of anticancer, antimicrobial, antidiabetic, anti-obesity and antioxidant activity of Ocimum Basilicum seeds essential oil from Palestine. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Park, J.; Hwang, D.Y.; Park, S.; Lee, H. Antimicrobial Evaluation and Fraction-Based Profiling of Basil Essential Oil Against Vaginal Pathogens. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Ge, Y.; Luo, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Q. Evaluation of the chemical composition, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of distillate and residue fractions of sweet basil essential oil. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 1882–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.D.; Kaur, I.; Angish, S.; Thakur, A.; Sania, S.; Singh, A. Comparative phytochemistry, antioxidant, antidiabetic, and anti-inflammatory activities of traditionally used Ocimum basilicum L. Ocimum gratissimum L., and Ocimum tenuiflorum L. BioTechnologia 2022, 103, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo Couto, H.G.S.; Blank, A.F.; Oliveira E Silva, A.M.; Nogueira, P.C.L.; Arrigoni-Blank, M.F.; Nizio, D.A.C.; Pinto, J.A.O. Essential oils of basil chemotypes: Major compounds, binary mixtures, and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2019, 293, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayezizadeh, M.R.; Ansari, N.A.; Sourestani, M.M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Biochemical Compounds, Antioxidant Capacity, Leaf Color Profile and Yield of Basil (Ocimum sp.) Microgreens in Floating System. Plants 2023, 12, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendran, G.; Vimolmangkang, S. Chemical compositions, antioxidant, antimicrobial, and mosquito larvicidal activity of Ocimum americanum L. and Ocimum basilicum L. leaf essential oils. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeharika, B.; Vijayalaxmi, K.G.; Chavannavar, S.; Chavan, M. Antioxidant, antidiabetic, and antimicrobial efficacy of germinated Ocimum gratissimum and Ocimum basilicum seed. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 3843–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenore, G.C.; Campiglia, P.; Ciampaglia, R.; Izzo, L.; Novellino, E. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of traditional green and purple "Napoletano" basil cultivars (Ocimum basilicum L.) from Campania region (Italy). Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 2067–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiwakoti, S.; Saleh, O.; Poudyal, S.; Barka, A.; Qian, Y.; Zheljazkov, V.D. Yield, Composition and Antioxidant Capacity of the Essential Oil of Sweet Basil and Holy Basil as Influenced by Distillation Methods. Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1600417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, A.; Asif, M.; Khalid, S.H.; Ullah Khan, I.; Asghar, S. Nanosizing of Lavender, Basil, and Clove Essential Oils into Microemulsions for Enhanced Antioxidant Potential and Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Activities. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 40600–40612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abidoye, A.O.; Ojedokun, F.O.; Fasogbon, B.M.; Bamidele, O.P. Effects of sweet basil leaves (Ocimum basilicum L.) addition on the chemical, antioxidant, and storage stability of roselle calyces (Hibiscus sabdariffa) drink. Food Chem. 2022, 371, 131170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, M.S.; Khaled, A.M.; Al-Bagawi, A.H.; Fareid, M.A.; Ghany, R.A.; Habotta, O.A.; Abdel Moneim, A.E. Hepatorenal protective efficacy of flavonoids from Ocimum basilicum extract in diabetic albino rats: A focus on hypoglycemic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic activities. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 144, 112287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftekhar, N.; Moghimi, A.; Hossein Boskabady, M.; Kaveh, M.; Shakeri, F. Ocimum basilicum affects tracheal responsiveness, lung inflammatory cells and oxidant-antioxidant biomarkers in sensitized rats. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 42, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Mansour, F.; Ayadi, H.; van Pelt, J.; Elfeki, A.; Bellassoued, K. Antioxidant and Protective Effect of Ocimum basilicum Seeds Extract on Renal Toxicity Induced by Carbon Tetrachloride in Rats. J. Med. Food 2024, 27, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakkas, H.; Papadopoulou, C. Antimicrobial Activity of Basil, Oregano, and Thyme Essential Oils. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khot, A.J.P.; Ankola, A.V.; Dodamani, S.; Sankeshwari, R.M.; Kumar, R.S.; Santhosh, V.N. Assessment of potential antimicrobial activity of Ocimum basilicum extract and chlorhexidine against Socransky’s complex pathogens of oral cavity: An in vitro study. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2023, 27, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsalamah, S.; Algonuim, M.I.; Basher, N.; Sulieman, A.M.E. Assessment of The Antibacterial Susceptibility of Ocimum basilicum. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2022, 68, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backiam, A.D.S.; Duraisamy, S.; Karuppaiya, P.; Balakrishnan, S.; Sathyan, A.; Kumarasamy, A.; Raju, A. Analysis of the main bioactive compounds from Ocimum basilicum for their antimicrobial and antioxidant activity. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2023, 70, 2038–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaldiz, G.; Camlica, M.; Erdonmez, D. Investigation of some basil genotypes in terms of their effect on bacterial communication system, and antimicrobial activity. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 182, 106247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, S.A.; Nur Shadrina, A.A.; Julaeha, E.; Kurnia, D. Potential Nevadensin from Ocimum basilicum as Antibacterial Agent against Streptococcus mutans: In Vitro and In Silico Studies. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2023, 26, 1746–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herdiyati, Y.; Astrid, Y.; Shadrina, A.A.N.; Wiani, I.; Satari, M.H.; Kurnia, D. Potential Fatty Acid as Antibacterial Agent Against Oral Bacteria of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis from Basil (Ocimum americanum): In vitro and In silico Studies. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2021, 18, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo Silva, V.; Pereira da Sousa, J.; de Luna Freire Pessôa, H.; Fernanda Ramos de Freitas, A.; Douglas Melo Coutinho, H.; Beuttenmuller Nogueira Alves, L.; Oliveira Lima, E. Ocimum basilicum: Antibacterial activity and association study with antibiotics against bacteria of clinical importance. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Samahy, L.A.; Tartor, Y.H.; Abdelkhalek, A.; Pet, I.; Ahmadi, M.; El-Nabtity, S.M. Ocimum basilicum and Lagenaria siceraria Loaded Lignin Nanoparticles as Versatile Antioxidant, Immune Modulatory, Anti-Efflux, and Antimicrobial Agents for Combating Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria and Fungi. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Ahmad, K.; Khalil, A.T.; Khan, J.; Khan, Y.A.; Saqib, M.S.; Umar, M.N.; Ahmad, H. Evaluation of antileishmanial, antibacterial and brine shrimp cytotoxic potential of crude methanolic extract of Herb Ocimum basilicum (Lamiaceae). J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2015, 35, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnia, D.; Putri, S.A.; Tumilaar, S.G.; Zainuddin, A.; Dharsono, H.D.A.; Amin, M.F. In silico Study of Antiviral Activity of Polyphenol Compounds from Ocimum basilicum by Molecular Docking, ADMET, and Drug-Likeness Analysis. Adv. Appl. Bioinform. Chem. 2023, 16, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, S.; Alawadhi, H.; Riva, A.; Allegrini, P.; Petrangolini, G.; Gasparri, C.; Alalwan, T.A.; Rondanelli, M. In Vitro and In Vivo Anticancer Activity of Basil (Ocimum spp.): Current Insights and Future Prospects. Cancers 2022, 14, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcibasi, U.; Dewa, M.T.; Karatay, K.B.; Kilcar, A.Y.; Muftuler, F.Z.B. Investigation of Bioactivity of Estragole Isolated from Basil Plant on Brain Cancer Cell Lines Using Nuclear Method. Curr. Radiopharm. 2023, 16, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhateeb, M.A.; Al-Otaibi, W.R.; AlGabbani, Q.; Alsakran, A.A.; Alnafjan, A.A.; Alotaibi, A.M.; Al-Qahtani, W.S. Low-temperature extracts of Purple blossoms of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) intervened mitochondrial translocation contributes prompted apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Biol. Res. 2021, 54, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintapula, U.; Oh, D.; Perez, C.; Davis, S.; Ko, J. Anti-cancer bioactivity of sweet basil leaf derived extracellular vesicles on pancreatic cancer cells. J. Extracell. Biol. 2024, 3, e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, R.G.; Casanova, L.; Carvalho, J.; Marcondes, M.C.; Costa, S.S.; Sola-Penna, M.; Zancan, P. Ocimum basilicum but not Ocimum gratissimum present cytotoxic effects on human breast cancer cell line MCF-7, inducing apoptosis and triggering mTOR/Akt/p70S6K pathway. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2018, 50, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Prakash, O.; Shukla, A.; Rajpurohit, C.S.; Vasudev, P.G.; Luqman, S.; Srivastava, S.K.; Pant, A.B.; Khan, F. Structure-Activity Relationship Studies on Holy Basil (Ocimum sanctum L.) Based Flavonoid Orientin and its Analogue for Cytotoxic Activity in Liver Cancer Cell Line HepG2. Comb. Chem. High Throughput. Screen. 2016, 19, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhura, N.; Gupta, P.; Gupta, J. Target-based in-silico screening of basil polysaccharides against different epigenetic targets responsible for breast cancer. J. Recept. Signal. Transduct. Res. 2022, 42, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, B.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, Y.; Su, Z.; Tang, L.; Yang, L.; Wang, T.; He, C.; Li, C.; et al. Integrated microbiome and metabolome analysis reveals synergistic efficacy of basil polysaccharide and gefitinib in lung cancer through modulation of gut microbiota and fecal metabolites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 135992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaghasia, H.; Patel, R.; Prajapati, J.; Shah, K.; Saraf, M.; Rawal, R.M. Cytotoxic and immunomodulatory properties of Tinospora cordifolia, Boerhaavia diffusa, Berberis aristata, and Ocimum basilicum extracts against HPV-positive cervical cancer cell line. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2025, 25, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, K.; Nakayama, M.; Okizaki, A. Benefits of basil tea for patients with differentiated thyroid cancer during radioiodine therapy: A randomized controlled trial. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Article (First Author) | Study | Methods | Bioactive Components | Antioxidant Activity | Antimicrobial Activity | Anticancer Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vijay et al., 2025 [40] | In vitro | Hydroalcoholic extraction of Ocimum basilicum leaves. GC-MS Phytochemical tests. DPPH, reducing power, H2O2 scavenging, and anti-lipid peroxidation assays. Poison food assay, time-killing curve assay. | - | Different IC50 values of antioxidant activity in different methods. | A dynamic interaction between the extract and microbial strain has been reported. Concentration-dependent antifungal activity. | - |

| Wójciak et al., 2024 [41] | In vitro | Polyphenolic fraction isolated from O.basilicum. UPLC-DAD-MS DPPH, FRAP, SOD, and CAT activity, and MDA levels of human normal colon epithelial and human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells after H2O2 treatment. | Caffeic acid derivatives (rosmarinic and chicoric acids). | High radical scavenging activity. Prevention of SOD and CAT depletion. MDA levels decrease. Protection of H2O2-induced cytotoxicity in human normal colon epithelial cells. | - | - |

| Nadeem et al., 2022 [42] | In vitro | Basil extracts by using n-hexane, dichloromethane, ethanol, and water at three different growth stages (GS), i.e., GS-1 (58 days of growth), GS-2 (69 days of growth), and GS-3 (93 days of growth). LC-ESI-MS/MS DPPH, FRAP, and H2O2 assays. | Higher concentration of phenolic acid, flavonoids, and tannin content in ethanolic extracts. Rosmarinic acid, ellagic acid, catechin, liquiritigenin, and umbelliferone. | Ethanolic extracts exhibited the highest antioxidant activity. | - | - |

| Vidaković et al., 2024 [43] | In vitro | Basil aerial parts were extracted using ethanol, dichloromethane, and sunflower oil separately. Re-extraction of the extracted oil with acetonitrile was also prepared. HPLC-DAD/ESI-ToF-MS DPPH assay. Antimicrobial activity was explored in 8 bacterial, 2 yeast, and 1 fungal species by using the broth microdilution method. | In total, 109 compounds were identified in ethanolic, dichloromethane, and acetonitrile extracts. Fatty acids were present in all extracts. Phenolic acids and flavonoids were dominant in ethanolic extracts. Triterpenoids were dominant in dichloromethane and diterpenoids in acetonitrile extracts. | Ethanolic and acetonitrile extracts showed significant radical scavenging potential. | All extracts exhibited high antifungal activity, as compared to the antimicrobial drug nistatin. Antibacterial activities were notable for ethanolic and acetonitrile extracts, whereas the dichloromethane extract showed no activity against bacteria. | - |

| Abdel-Razakh et al., 2024 [44] | In vitro | Ethanolic, ethyl acetate extracts, and solvent fractions. Total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), and total tannin content (TTC). LC-MS. HPLC-ABTS. DPPH and ABTS. | TPC of O. basilicum ranged from 64.70 ± 5.2 to 411.16 ± 8.11 mgGAE (gallic acid equivalents) /g DW (dry weight). The ethyl acetate extract obtained the maximum TPC, TFC, and TTC. Rosmarinic acid was identified as the major component in all extracts and all fractions of O. basilicum. | Ethyl acetate fractions have the strongest antioxidant activities. | - | - |

| Mahmoud et al., 2022 [45] | In vitro | Ocimum basilicum residues were dried in an oven and in a microwave. HS-SPME. GC-MS. LC-MS/MS. Folin–Ciocalteu photochemiluminescence. | In total, 30 volatiles were identified in raw material, with β-linalool, methyleugenol, methylcinnamate, and estragole identified as the predominant molecules. A total of 24 and 18 volatiles were detected in the oven- and microwave-dried samples, with a significant decrease in methyleugenol content. The highest TPC was found in the microwaved waste. In total, 8 phenolic acids and 9 flavonoids were identified, with significant contents of rosmarinic acid and luteolin (1042.45 and 11.68 µg/g of dry matter, respectively) in the microwaved samples. | The highest radical scavenging ability was achieved for microwaved waste. | - | - |

| Qamar et al., 2023 [46] | In vitro and ex vivo | Basil leaf extracts. GC-MS of non-polar extracts. ESI-HRMS/MS of polar extracts. TPC and TFC were measured spectrophotometrically and calculated as GAE/ g DW and rutin equivalent (RE)/g DW, respectively. DPPH, AAPH, and ABTS assays. | In total, 75 compounds (monoterpenes, hydrocarbons, sesquiterpenes, triterpenes, phyto-sterols, and phthalates) were found in non-polar extracts. High fatty acid concentrations. Predominant compounds: linalool (7.65%), terpineol (1.42%), tau-cadinol (13.55%), methyl palmitate (14.24%), palmitic acid (14.31%), linolenic acid (1.30%), and methyl linolenate (17.72%). Alkaloids, phenolic acids, amino acids, coumarins, lignins, flavonoids, and terpenes were identified in polar extracts. The highest TPC and TFC were found in ethyl acetate extract (9.40 mg GAE/g and 15.9 mg RE/g of dry weight, respectively. | All the extracts showed significant antioxidant activity in DPPH and ABTS assays. Dichloromethane extract showed the highest DPPH scavenging activity, i.e., 64.12% ± 0.23 at a concentration of 4 mg/mL. All the extracts inhibited AAPH-induced oxidation in human erythrocytes, being 69.24% ± 0.18 in the dichloromethane extract, 64.44% ± 0.04 in ethyl acetate, and 53.33% ± 0.09 in the acetone extract. | - | - |

| Siripongvutikorn et al., 2024 [47] | In vitro | Spicy basil leaf extracts LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS DPPH, FRAP, ABTS, and ORAC. | 62 components, including quininic acid, hydroxycinnamic acid, luteolin, kaempferol, catechin, eugenol, betulinic acid, and gingerol. | High antioxidant activity, mainly depending on cynaroside and luteolin-7-O-glucoside. | - | - |

| Złotek et al., 2016 [48] | In vitro | Fresh, frozen, and lyophilized basil leaves. Extraction with acetone or methanol, with/without the addition of acetic acid in different steps. Folin–Ciocalteau, DPPH, Reducing power assays. | Highest TPC in acetone mixtures with the highest addition of acetic acid of fresh and freeze-dried material. The three-fold procedure was more effective than the once-shaking procedure in most of the extracts obtained from fresh basil leaves, unlike the extracts from frozen material. No differences in the TPC between the two procedures used in the lyophilized basil leaves. | Positive correlation between TPC and antioxidant activity. | - | - |

| Yibeltal et al., 2022 [50] | In vitro | Ocimum basilicum leaf and flower essential oils extraction. DPPH and H2O2 free radical scavenging assays. Disk diffusion, broth dilution assays. | Higher DPPH scavenging activity (86.45%) for leaf oil extract. | The strongest antibacterial activity with maximum zone of inhibition (15.47 mm), MIC (0.09 μg/mL, and MBC (0.19 μg/mL) was exhibited by the flower oil extract against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC-25923. The strongest antifungal activity with maximum zone of inhibition (15.90 mm), MIC (0.125 μg/mL), and MFC (0.09 μg/mL) was recorded for leaf oil against Candida albicans. | - | |

| Eid et al., 2023 [51] | In vitro | Ocimum basilicum seed from Palestine. Essential oil extraction. DPPH. Broth microdilution assay, cytotoxicity assay. | IC50 of 23.44 ± 0.9 µg/mL compared with trolox (IC50 2.7 ± 0.5 µg/mL). | Antibacterial activity against Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Proteus mirabilis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and antifungal activity against Candida albicans. | O. basilicum seed EO showed high anticancer activity against Hep3B (IC50 56.23 ± 1.32 µg/mL) and MCF-7 (80.35 ± 1.17 µg/mL), as compared to doxorubicin. | |

| Park et al., 2025 [52] | In vitro | Basil essential oil extraction. HPLC, GC-MS, DPPH, and ABTS assays. Disk diffusion test, broth microdilution assay (MIC). | Monoterpene, phenylpropene, and sesquiterpene derivatives. Methyl trans-cinnamate was identified as the major compound in fraction 3 obtained by preparative HPLC. | DPPH and ABTS assays returned EC50 values of 115.36 (DPPH) and 54.77 (ABTS) µg/mL. | Significant antimicrobial activity against Gardnerella vaginalis, Fannyhessea vaginae, Chryseobacterium gleum, and Candida albicans, with inhibition zones of up to 25.88 mm and MIC values ranging from 31 to 500 µg/mL. Fraction 3 showed the highest antimicrobial activity. | - |

| Li et al., 2017 [53] | In vitro | Sweet basil crude oil was processed via molecular distillation. GC-MS. DPPH and ABTS assays. | Major constituents of the residue fraction: estragole (17.06%), methyl eugenol (11.35%), and linoleic acid (11.40%). Major constituents of the distillate fraction: methyl eugenol (16.96%), α-cadinol (16.24%), α-bergamotene (11.92%). | The residue fraction markedly scavenged the DPPH (IC50 = 1.092 ± 0.066 mg/mL) and ABTS (IC50 = 0.707 ± 0.042 mg/mL) radicals. | - | - |

| Sharma et al., 2022 [54] | In vitro | Leaf extracts from dried powder of Ocimum basilicum (Green tulsi), O. gratissimum (Jungli tulsi), and O. tenuiflorum (Black tulsi) were prepared by using acetone, ethanol, methanol, and water. Folin–Ciocalteu (TPC), AlCl3 assay (TFC), and total condensed tannin analysis. Fingerprint analysis using UV, Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR), and fluorescent spectroscopy, DPPH, and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) assay. | High levels of polyphenolics were detected in all the solvent extracts. Acetone provided the highest concentrations of phenolics, flavonoids, and tannins in all Ocimum species. O. tenuiflorum showed the maximum level of antioxidants. | O. tenuiflorum showed the highest antioxidant activity. | - | - |

| Araújo Couto et al., 2019 [55] | In vitro | Essential oils extraction of 24 different basil genotypes. DPPH and linoleic acid peroxidation assays. | Eugenol was the major component identified. | A total of 9 essential oils exhibited high antioxidant potential, with at least 52.68% of inhibition of the linoleic acid peroxidation at 10 µL/mL and 76.34% of inhibition of the DPPH radical at 1 µL/mL. The major compound eugenol had the highest antioxidant activity. Synergism between minor compounds results in high antioxidant activity. | - | - |

| Fayezizadeh et al., 2023 [56] | In vitro | In total, 21 cultivars and genotypes of basil microgreen extracts. Folin–Ciocalteu (TPC), AlCl3 assay (TFC), anthocyanin, and vitamin C content measurement. DPPH and APCI. | Variation in phytochemical components between basil genotypes. | The highest APCI was measured in the Persian Ablagh genotype (70.30). In total, 21 basil genotypes were classified into 4 clusters: cluster 1 (lowest antioxidant capacity and TPC), cluster 2 (lowest anthocyanin, vitamin C, and APCI), cluster 3 (highest vitamin C, TPC, antioxidant capacity, and APCI), and cluster 4 (highest levels of anthocyanin). The average annual temperature of the origin of basil seeds plays an important role in the synthesis of antioxidant components. Most of the seeds with moderate origin had a higher APCI. | - | - |

| Mahendran & Vimolmangkang, 2023 [57] | In vitro | O. americanum and O. basilicum EOs extraction by steam distillation in a Clevenger-type apparatus. GC-MS DPPH, FRAP, ABTS, and metal-chelating assays. Disk-diffusion test and broth microdilution method. | Camphor (33.869%), limonene (7.215%), longifolene (6.727%), caryophyllene (5.500%), and isoledene (5.472%) were the major compounds in O. americanum leaf EO. The EO yield was 0.4%, and citral (19.557%), estragole (18.582%), camphor (9.224%), and caryophyllene (3.009%) were the major compounds found among the 37 chemical constituents identified in O. basilicum EO. | O. basilicum exhibited a more potent antioxidant activity than O. americanum. | Zone of inhibition and MIC of the Eos in the disk diffusion and the microdilution methods were 8.00 ± 0.19 mm to 26.43 ± 2.19 mm and 3.12–100 µg/mL, respectively. | - |

| Neeharika et al., 2025 [58] | In vitro | Ethanolic, methanolic, and distilled water extracts of O. gratissimum and O. basilicum seeds. ABTS, O2−, lipid peroxidation assays. Agar well diffusion, fungal biomass inhibition assays | Ethanolic extracts of germinated O. gratissimum and O. basilicum seeds exhibited higher concentrations of phenols (21.03 ± 0.01 mg GAE/g and 21.46 ± 0.01 mg GAE/g, respectively) and flavonoids (11.92 ± 0.03 mg quercetin equivalent (QE)/g and 14.45 ± 0.04 mg QE/g, respectively), as compared to other extracts. | Ethanolic extracts of germinated O. gratissimum and O. basilicum exhibited IC50 values for scavenging ABTS (0.013 ± 0.00 mg/mL and 0.007 ± 0.00 mg/mL, respectively) and superoxide anion radical (4.33 ± 0.01 mg/mL and 4.14 ± 0.00 mg/mL respectively) and for inhibiting lipid oxidation (2.57 ± 0.00 mg/mL and 2.33 ± 0.00 mg/mL, respectively, as compared to other extracts. | Ethanolic extracts of germinated O. gratissimum and O. basilicum exhibited higher inhibition zones for Bacillus subtilis (13.98 ± 0.18 mm, 17.02 ± 0.18 mm, respectively), Vibrio parahaemolyticus (19.00 ± 0.20 mm, 22.58 ± 0.45 mm, respectively), Salmonella enterica (24.98 ± 0.18 mm, 22.17 ± 0.15 mm, respectively), and Escherichia coli (23.50 ± 0.50 mm, 27.00 ± 0.20 mm, respectively) and better inhibition of Aspergillus flavus growth (93.28% and 81.77%, respectively), as compared to other extracts. | - |

| Tenore et al., 2017 [59] | In vitro | Napoletano green and purple basil (Ocimum basilicum) varieties extracts. DPPH and FRAP assays. MIC. | Higher polyphenolic concentration as compared to other, more conventional, and geographically different basil varieties. | Napoletano purple basil revealed higher radical-scavenging and ferric-reducing capacities than the green one, probably due to its anthocyanin content. | Both basil varieties exhibited activity against a broad spectrum of food-borne and human pathogenic microorganisms (Gram+ and Gram− bacteria, yeasts). | - |

| Shiwakoti et al., 2017 [60] | In vitro | EO extraction of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum) and holy basil (Ocimum tenuiflorum) by steam distillation and hydrodistillation. ORAC | In both basil species, the EO yield was higher from steam distillation than from hydrodistillation. Same compounds were identified in both types of extraction, with differences in concentration. In the EO of O. basilicum, the concentration of 74% of the identified compounds was higher in steam distillation as compared to the hydrodistillation, whereas in the EO of O. tenuiflorum, the concentration of 84% of the identified compounds was higher in steam distillation. However, the concentrations of estragole and methyl cinnamate in O. basilicum EO and methyl eugenol in O. tenuiflorum EO were significantly higher in hydrodistillation extracts. | The type of distillation did not affect the antioxidant capacity of basil EO in both species. | - | - |

| Manzoor et al., 2023 [61] | In vitro | Nanosized lavender, basil, and clove EO in microemulsions. DPPH. Agar well diffusion, broth microdilution assays. The crystal violet assay was used to measure the growth and development of biofilms. | EOs concentration had a great impact on the physicochemical and biological properties of microemulsions. | Dose-dependent antioxidant capacity. | Microemulsions demonstrated more efficient antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli, at concentrations lower than pure EOs. | - |

| Abidoye et al., 2022 [62] | In vitro | A drink made with roselle calyces (Hibiscus sabdariffa) and sweet basil leaves (Ocimum basilicum). The roselle–basil samples at different blend ratios were analyzed for pH, total soluble solids, total titratable acidity, vitamin C, lycopene, TPC, antioxidant properties (ABTS, ORAC), and storage stability at different temperatures (4 and 29 °C). | The incorporation of sweet basil leaves to roselle calyces slightly decreased the vitamin C and lycopene content of the drink, whereas they increased the total carotenoid and antioxidant activities. Storing samples at 29 °C resulted in higher antioxidant activity, as compared to storage at 4 °C. | |||

| Othman et al., 2021 [63] | In vivo | Hail Ocimum extract and its total flavonoids against hepatorenal damage in experimental diabetes induced by HFD and injection of streptozotocin in rats. Diabetic animals were co-treated daily with HOE, flavonoids, or metformin as a standard anti-diabetic drug for 4 weeks. GSH levels. SOD, CAT, GPX, GR activity. | - | Co-treatment of diabetic animals with Hail Ocimum extract or its total flavonoids protected them from oxidative stress induced by HFD and streptozotocin treatment (GSH levels increased, and SOD, CAT, GPX, and GR enzyme activity were induced). | - | - |

| Eftekhar et al., 2019 [64] | In vivo | Effect of O. basilicum on tracheal responsiveness to methacholine and ovalbumin, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid levels of oxidant-antioxidant biomarkers in sensitized rats. In total, 6 groups of rats, including the control (group C), sensitized rats to ovalbumin (group S), S groups treated with 3 concentrations of O. basilicum (0.75, 1.5, and 3 mg/mL), and 1.25 μg/mL of dexamethasone were studied. MDA, TBARS, total stable oxidation products of NO metabolism (NO2−/NO3−), and total thiol content. SOD and CAT activity. | - | Decrease in the tracheal bronchoalveolar lavage fluid levels of oxidant markers of rats sensitized to methacholine and ovalbumin, and an increase in antioxidant marker levels, in a dose-dependent manner. | - | - |

| Ben Mansour et al., 2024 [65] | In vivo | Ocimum basilicum seeds methanolic extraction. A single dose of CCl4 was used to induce oxidative stress in rats, which was demonstrated by a significant rise in serum enzyme markers. Extract was administered for 15 consecutive days (200 mg/kg body weight) to Wistar rats before CCl4 treatment. Kidney SOD, CAT, GPX activities and GSH, TBARS, urea, creatinine, lipid peroxidation and protein carbonyl levels were measured. | - | Basil seed extract administration resulted in a significant reduction in urea, creatinine, TBARS, protein carbonyls, and lipid peroxidation levels, whereas antioxidant enzyme activity, like GPΧ, SOD, catalase, and GSH levels, was elevated. | - | - |

| Khot et al., 2023 [67] | In vitro | Ethanol-based extraction of Ocimum basilicum seed was performed by the Soxhlet method, and aqueous-based extracts by the hot infusion procedure. Extracts were assessed for MIC, MBC, zone of inhibition, and time-kill assay on periodontal pathogens, and compared the effectiveness against 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate. | - | - | 10 mg/mL of ethanolic extract was effective against periodontal pathogens, whereas 4.7 mg/mL of aqueous extract was proven effective. Aqueous extract developed a wider zone against periodontal pathogens compared to ethanolic extract. A statistically significant difference was found in the effectiveness between the extract and chlorhexidine. | - |

| Alsalamah et al., 2022 [68] | In vitro | Ethanolic and methanolic extracts of Ocimum basilicum seeds and leaves. Disk diffusion and direct contact test were used for antibacterial activity measurement against 3 strains. Spectrophotometry. | Methanolic extracts of leaves contained tannins, flavonoids, glycosides, and steroids, whereas seed extracts contained saponins, flavonoids, and steroids. Stems contained saponins and flavonoids. | - | The plant extracts inhibited Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and E. coli. Leaf extracts were more potent than seed and stem extracts. | - |

| Backiam et al., 2023 [69] | In vitro | Ocimum basilicum leaf extract was prepared using ethanol, methanol, and water. GC-MS. Folin–Ciocalteu (TPC) and AlCl3 (TFC). Antibacterial activity against vancomycin-resistant (VRE) enterococcal strains and microbial type culture collection (MTCC) strains. Agar well-diffusion assay and MIC. DNA and protein absorption at 260 nm, scanning electron microscopy (SEM). | The ethanol and methanol extracts contain alkaloids, flavonoids, phenolic compounds, tannins, saponins, quinones, carbohydrates, and proteins, except for steroids and terpenoids. In addition to steroids and terpenoids, tannin was also absent in the aqueous extract. Total phenolic and flavonoid content was high in ethanolic, followed by methanolic and aqueous extracts. Ethanolic extracts included 19 compounds. | - | Ethanolic and methanolic extracts showed strong antimicrobial activity against VRE and MTCC strains at a concentration of 20 mg/mL, as compared to the aqueous extract. Staphylococcus aureus is highly susceptible to ethanolic extract at a concentration of 8 mg/mL and followed by other MTCC strains. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci pathogens were inhibited at the MIC of 14, 16, and 20 mg/mL of ethanolic, methanolic, and aqueous extracts, respectively. The loss of cell membrane integrity and cell membrane damage were the effective mechanisms of plant extract antimicrobial activity. | - |

| Yaldiz et al., 2023 [70] | In vitro | Essential oil and ethanol extract of basil. Agar well, disk, and agar well diffusion assays. Anti-quorum-sensing activity and violacein pigment isolation by spectrophotometric analysis. Biofilm biomass measurement. | - | - | EO and ethanol extracts of basil exhibited both antibacterial activity and anti-quorum-sensing activity against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial species, and antifungal effects on C. albicans. Among the tested microorganisms, the genotypes of PI 531396, PI 296390, PI 414199, PI 253157, PI 296391, PI 652071, midnight, and Dino cultivars have been found to be more susceptible than other genotypes. The highest effect on the quorum-sensing system was found in Moonlight and Dino cultivars, PI 296391, PI 414199, PI 652070, PI 172997, and PI 190100 genotypes. Dendrogram analysis has shown that there is a relationship between different genotypes, depending on microorganisms and anti-quorum-sensing activity. Ames 29184, PI 207498, and PI 379412 genotypes were clustered in the same group. | - |

| Putri et al., 2023 [71] | In vitro and in silico | Nevadensin (a flavonoid of basil) is an antibacterial against S. mutans. Disk diffusion and micro-dilution assays. Ligand–protein docking. | - | - | MIC and MBC values of nevadensin are 900 and 7200 μg/mL, respectively. The binding energy of nevadensin to SrtA, gbpC, and Ag I/II genes was −4.53, 8.37, and −6.12 kcal/mol, respectively. | - |

| Herdiyati et al., 2021 [72] | In vitro and in silico | Fresh leaves from O. americanum were extracted with n-hexane and purified by a combination of column chromatography on normal and reverse phases, together with in vitro bioactivity assay against S. mutans ATCC 25175 and S. sanguinis ATCC 10556, respectively, while in silico molecular docking simulation of lauric acid was conducted using PyRx 0.8. | - | - | The structure determination of an antibacterial compound by spectroscopic methods resulted in an active compound, lauric acid. The in vitro evaluation of antibacterial activity in lauric acid showed MIC and MBC values of 78.13 and 156.3 ppm and 1250 and 2500 ppm against S. sanguinis and S. mutans, respectively. In silico evaluation determined lauric acid as a MurA enzyme inhibitor. Lauric acid showed a binding affinity of −5.2 Kcal/mol, which was higher than fosfomycin. | - |

| Araújo Silva et al., 2016 [73] | In vitro | O. basilicum leaves extraction by steam distillation. Broth microdilution (MIC). Combinations of O. basilicum oil with ciprofloxacin or imipenem were analyzed by the checkerboard method, where fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) indices were calculated. | - | - | O.basilicum EO, imipenem, and ciprofloxacin showed respective MIC antibacterial activities of 1024, 4, and 2 μg/mL against S. aureus. In S. aureus, the oil with imipenem association showed a synergistic effect (FIC = 0.0625), while the oil with ciprofloxacin showed antagonism (FIC value = 4.25). In P. aeruginosa, the imipenem/oil association showed an additive effect for ATCC strains, and synergism for the clinical strain (FIC values = 0.75 and 0.0625). The association of O. basilicum EO with ciprofloxacin showed synergism for clinical strains (FIC value = 0.09). | - |

| El-Samahy et al., 2024 [74] | In vitro and in vivo | O. basilicum lignin nanoparticles were tested for their antimicrobial potential against Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella enterica, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton rubrum, and Microsporum canis, and further tested for their anti-efflux activity against ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella enterica strains and for treating Salmonella infection in a rat model. Antifungal efficacy for treating T. rubrum infection in a guinea pig model was also tested. Disk diffusion and broth microdilution assays. Real-time PCR (polymerase chain reaction). | - | - | Nanoparticles showed antibacterial activity against Salmonella enterica species with a MIC range of 0.5–2 µg/mL and antifungal activity against T. rubrum with a MIC range of 0.25–2 µg/mL. Downregulation of the expression of ramA and acrB efflux pump genes (fold change values ranged from 0.2989 to 0.5434—0.4601 to 0.4730 for ramA and 0.3842–0.6199; 0.5035–0.8351 for acrB) was also obtained. Oral administration of basil lignin nanoparticles in combination with ciprofloxacin had a significant effect on all blood parameters, as well as on liver and kidney function parameters. Oxidative stress mediators, total antioxidant capacity, and MDA were abolished by oral administration of basil lignin nanoparticles (0.5 mL/rat once daily for 5 days). INF-γ and TNF-α were also reduced in comparison with the positive control group and the ciprofloxacin-treated group. Histopathological examination of the liver and intestine of basil lignin nanoparticles-treated rats revealed an elevation in Salmonella clearance. Treatment of T. rubrum-infected guinea pigs with basil lignin nanoparticles topically in combination with itraconazole resulted in a reduction in lesion scores, microscopy, and culture results. | - |

| Khan et al., 2015 [75] | In vitro | Antileishmanial, antibacterial, and brine lethality assays of the leaf extract of O. basilicum from the Peshawar region. In total, 6 Gram+ and 6 Gram− were tested. Negative bacteria. Brine shrimp cytotoxicity assay. | - | - | LC50 = 21.67 µg/mL for Leishmania. Significant inhibitory activity at the highest two concentrations, ranging from 20.66 ± 0.31 to 31.86 ± 0.80 for Gram+ strains Clostridium perfringens type C and Bacillus subtitilis, respectively, as compared to gentamycin (27.36 ± 0.55 and 21.80 ± 0.72, respectively). Good activity was observed Gram- strains. The highest zone of inhibition was recorded for Pseudomonas aeroginosa (28.83 ± 0.28) at the highest concentration (10 mg/mL). The LC50 value obtained for the brine shrimp lethality assay was 91.56 µg/mL. | - |

| Kurnia et al., 2023 [76] | In silico | Inhibition of the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 by apigenin-7-glucuronide, dihydrokaempferol-3-glucoside, and aesculetin from O. basilicum. Autodock 4.0 tools were used for the prediction of the molecular docking inhibition mechanism, such as the pkcsm and protox online web server for ADMET analysis and drug likeness. | - | - | The binding affinity for apigenin-7-glucuronide was −8.77 Kcal/mol, for dihydrokaempferol-3-glucoside −8.96 Kcal/mol, and for esculetin −5.79 Kcal/mol. Inhibition constant values were 375.81 nM, 270.09 nM, and 57.11 µM, respectively. Apigenin-7-glucuronide and dihydrokaempferol-3-glucoside bind to the main protease enzymes on the active sites of Cys145 and His41, while aesculetin only binds to the active sites of Cys145. On ADMET analysis, all 3 compounds met the predicted pharmacokinetic parameters, although there are some specific parameters that must be considered, especially for aesculetin compounds. For drug-likeness analysis, apigenin-7-glucuronide and dihydrokaempferol-3-glucoside compounds have one violation, and aesculetin has no violations. | - |

| Avcibasi et al., 2023 [78] | In vitro | Estragole isolation from basil leaves via ethanolic extraction using an 80% ethanol concentration and HPLC. Estragole was radiolabeled with 131I using the iodogen method. Quality control studies were carried out by using TLRC. Next, in vitro cell culture studies were performed to investigate the bio-affinity of with human medulloblastoma (DAOY) and human glioblastoma-astrocytoma (U-87 MG) cell lines. Finally, the cytotoxicity was determined, and cell uptake was investigated on cancer cell lines by incorporation studies. | - | - | - | 131I-estragole has a significant uptake in the brain cancer cells. |

| Alkhateeb et al., 2021 [79] | In vitro | Fresh dark purple blossoms of basil were extracted at low temperature (0 °C) using a watery solvent. Human MCF7 breast cancer cells were then treated with 3 separate fluctuated concentrations of 0, 50, 150, and 250 µg/mL for 24 and 48 h. Mitochondrial fission contributed to the induced apoptosis, which was evaluated. | Anthocyanins, anthraquinones, tannins, reducing sugars, glycosides, proteins, amino acids, flavonoids, and volatile oils were detected, whereas terpenoids and alkaloids were absent. A frail presence of steroids in basil blossom aqueous concentrate was noticed. | - | - | Glucose uptake was alleviated in a dose-dependent manner in MCF7 cells with the extract induced for 24 h, resulting in mitochondrial fission and apoptosis induction. |

| Chintapula et al., 2024 [80] | In vitro | Extracellular vehicles purified from apoplast washing fluid of basil leaves were used as a therapeutic agent against cancer. Characterization of extracellular vehicles revealed a size range of 100–250 nm, which were later assessed for their cell uptake and apoptosis-inducing abilities in pancreatic cancer cell line MIA PaCa-2. Cell viability and clonogenic assays. Reverse-Transcription (RT)-PCR and Western blotting. | - | - | - | Basil extracellular vehicles showed a significant cytotoxic effect on pancreatic cancer cell line MIA PaCa-2 at a concentration of 80 and 160 μg/mL in cell viability, as well as clonogenic assays. Similarly, RT-PCR and Western blot analysis have shown upregulation in apoptotic gene and protein expression of Bax, respectively, in BasEV treatment groups compared to untreated controls of MIA PaCa-2. |

| Torres et al., 2018 [81] | In vitro | The unfractionated aqueous leaf extracts of O. basilicum and O. gratissimum were chemically characterized and tested for their cytotoxic, cytostatic, and anti-proliferative properties against the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. | Both extracts presented cytostatic effects with an 80% decrease in MCF-7 cell growth at 1 mg/mL. However, only O. basilicum extract promoted cytotoxicity, interfering with the cell viability even after interruption of the treatment, and affected the cell proliferation and metabolism, as evaluated in terms of lactate production and intracellular ATP content. After 24 h of treatment, O. basilicum extract-treated cells were induced for apoptosis, whereas O. gratissimum extract-treated cells were induced for necrosis. The treatment with both extracts activated AMPK, but O. basilicum extract was much more efficient. Only O. basilicum extract activated mTOR signaling. | |||

| Sharma et al., 2016 [82] | In silico and in vitro | An in silico structure-activity relationship study on orientin from Ocimum sanctum L. (O. tenuiflorum) was performed, and a pharmacophore mapping and QSAR model was built to screen out the potential structurally similar analogs from the chemical database of Discovery Studio (DSv3.5, Accelrys, USA) as potential anticancer agents. Analog fenofibryl glucuronide was selected for in vitro cytotoxic/anticancer activity evaluation through MTT assay. The binding affinity and mode of action of orientin and its analog were explored through molecular docking studies on quinone oxidoreductase. Cytotoxicity of HepG2 liver cancer cell line. | - | - | - | Only 41% of cell death at 202.389 μM after 96 h of treatment was observed. The selected orientin analog fenofibryl glucuronide was non-cytotoxic/non-anti-carcinogenic up to 100 μg/mL (202.389 μM) concentrations for a long-term exposure in HepG2 cells. Orientin and its analog showed no activity or less cytotoxicity on HepG2 cells. |

| Bhura et al., 2022 [83] | In silico | Basil polysaccharides were screened against HDAC1-2, 4–8, and HAT (targets for breast cancer) using molecular docking studies along with swissADME studies to check the drug likeliness. | - | - | - | Glucosamine ring, glucosamine linear, glucuronic acid linear, rhamnose linear, glucuronic acid ring, galactose ring, mannose, glucose, and xylose exhibited consistent binding potential against the epigenetic targets (HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC6, HDAC7, HDAC8, and HAT). |

| Feng et al., 2024 [84] | In vivo and in vitro | Basil polysaccharides were administered in a gefitinib-resistant xenograft mouse model in order to investigate whether BPS enhances the antitumor effects of gefitinib. A multi-omics approach, including 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing and LC-MS, was used to elucidate these synergistic effects. | - | - | - | Basil polysaccharides can enhance tumor responsiveness to gefitinib by modulating the gut microbiota and its metabolites through multiple metabolic pathways. These changes could potentially affect cancer-related signaling pathways and lung resistance-related proteins, which are pivotal in determining the efficacy of EGFR-TKIs, such as gefitinib, in cancer treatment. |

| Vaghasia et al., 2025 [85] | In vitro | Extracts from Ocimum basilicum were tested on CaSki and HEK 293 HPV-positive cervical cancer cells alongside cisplatin. Cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, cell migration, HPV DNA inhibition, IFN-γ secretion, and cell cycle modulation were assessed using quantitative PCR (qPCR), Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), and flow cytometry. | - | - | - | O. basilicum extract in combination with cisplatin significantly enhanced IFN-γ secretion and induced G0/G1 phase cell cycle arrest. |

| Nomura et al., 2023 [86] | Clinical study | A total of 44 differentiated thyroid cancer patients after total thyroidectomy were randomly divided into Group A (Basil tea group, n = 22) and Group B (Control group, n = 22). Subjects in Group A drank 180 mL of Basil tea prepared from 2.0 g of holy basil (Ocimum tenuiflorum Linn.) leaves after each meal for 4 days, starting on the day radioactive iodine therapy was performed. Those in Group B drank the same amount of distilled water after each meal for the same period as those in Group A. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was used to assess anxiety, while the saliva component test and salivary gland scintigraphy were used to assess the oral cavity. | - | - | - | The rate of change in the STAI score was significantly lower in Group A than in Group B (p < 0.05). The rates of change in cariogenic bacteria, ammonia, protein, and occult blood were significantly lower in Group A than in Group B (p < 0.05). The rate of change of the washout ratio for salivary gland scintigraphy was significantly lower in Group B than in Group A (p < 0.05). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poulios, E.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Psara, E.; Giaginis, C. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Anticancer Activity of Basil (Ocimum basilicum). Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1469. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121469

Poulios E, Papadopoulou SK, Psara E, Giaginis C. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Anticancer Activity of Basil (Ocimum basilicum). Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1469. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121469

Chicago/Turabian StylePoulios, Efthymios, Sousana K. Papadopoulou, Evmorfia Psara, and Constantinos Giaginis. 2025. "Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Anticancer Activity of Basil (Ocimum basilicum)" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1469. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121469

APA StylePoulios, E., Papadopoulou, S. K., Psara, E., & Giaginis, C. (2025). Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Anticancer Activity of Basil (Ocimum basilicum). Antioxidants, 14(12), 1469. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121469