Abstract

Postharvest fungal pathogens, such as Botrytis cinerea, Alternaria alternata and Fusarium culmorum, pose major challenges for pepper (Capsicum annuum) storage and shelf-life. To explore the basis of induced resistance, near isogenic lines (NILs) differing in pigmentation (green vs. purple fruits and their red ripe counterparts) were artificially inoculated and evaluated for disease severity by phenotyping and by qPCR, and metabolite composition by spectroscopy and by HPLC. Infection severity was strongly dependent on whether purple or green NILs were infected and on ripening stage: economically ripe fruits were most susceptible to B. cinerea, whereas biologically ripe fruits displayed higher infection rates with A. alternata. In the case of B. cinerea infection, detailed HPLC analysis revealed that chlorogenic acid and p-coumaric acid were identified as infection-responsive metabolites after analyzing the metabolite changes upon infection. Total anthocyanin content and delphinidin derivatives measured decreased upon infection; however, this effect was not significant in correlation with the infection severity, indicating that B. cinerea infection in low, moderate or severe amounts will lead to the degradation of these compounds. Overall, our findings indicate that anthocyanin accumulation alone did not confer resistance to B. cinerea in pepper, whereas specific hydroxycinnamic acids emerged as infection-responsive markers.

1. Introduction

Solanaceous crops play a vital role not only in terms of human nutrition but from an economical point of view as well. According to FAOSTAT, tomatoes ranked first, with 186 million tons, whereas peppers ranked seventh, with almost 37 million tons, amongst the vegetables produced worldwide. From a dietary point of view, peppers are an excellent source of vitamin C, flavonols, flavones and carotenoids, which not only benefit human health but may also help reduce postharvest losses.

According to estimates, postharvest losses of the global fruit and vegetable production range from 28 to 55% [], of which 10 to 30% can be attributed to losses caused by different microorganisms []. Peppers are generally characterized by a short shelf-life; to overcome this issue, different approaches have been developed, i.e., exogenous application of melatonin [], brassinosteroids [], glutathione [], usage of edible coatings [,,] or the application of different treatments such as steam or microwave [], but the most prevalent preservation technique is still low-temperature storage [,,]. However, pepper fruits are susceptible to chilling injuries below temperatures of 7–9 °C []; further, cold temperatures do not necessarily inhibit the growth of fungal pathogens. Botrytis cinerea can grow within a temperature range of 0.5–32 °C [] and Alternaria alternata within a range of 0 to 35 °C []. B. cinerea is amongst the most researched fungal pathogens causing pre- and postharvest rotting, leading to the development of gray mold disease [,,]. Solanaceus crops are also greatly affected by A. alternata, which typically causes black mold, and Fusarium spp., causing internal fruit rot in peppers [,,,].

Upon infection, these pathogens secrete cell-wall-degrading enzymes such as pectinases, endopolygalacturonases, cellulases, cutinases and proteases that facilitate host colonization [,]; however, susceptibility to infection depends on an array of factors; for example, the ripening stage affects pathogen growth [], and during maturation, metabolic processes undergo drastic changes: the fruit starts to soften, ethylene and sugars accumulate, the amount of polyphenolics declines and the pH shifts, all of which favors pathogen colonization [,,,]. Nevertheless, the accumulation of sugars and antifungal proteins during the ripening of grapes has been correlated with resistance to B. cinerea [].

Phenolic compounds—particularly flavonoids and anthocyanins—have attracted considerable interest as they are central to plant defense. Anthocyanins, besides their well-known antioxidant properties, have been implicated in direct antifungal activity by altering fungal cell walls and membrane permeability [] and consequently inhibiting spore germination and germ tube growth []. In tomato, elevated anthocyanin levels have been associated with enhanced resistance to B. cinerea infection [,], supporting the hypothesis that these pigments may play a similar protective role in peppers. This idea was already validated with Phytophthora capsici, through a study in which purple pepper leaves were shown to be slower to develop symptoms []. With the emergence of pathogen strains resistant to different fungicides [,], there is a need for safer, natural antifungal compounds such as anthocyanins that could provide an eco-friendly alternative for postharvest disease management.

Pepper cultivars display considerable variation in anthocyanin content, especially at the stage of economical ripeness [,]. As the fruit matures to the biologically ripe stage, anthocyanin levels typically decline, while carotenoid concentrations increase []. This shift in pigment composition is accompanied by changes in the broader phenolic profile, which may influence the fruit’s susceptibility to postharvest pathogens [,]. Nevertheless, the role of anthocyanins in conferring resistance against A. alternata and Fusarium spp. in pepper remains poorly documented.

Understanding how pigment composition, phenological stage and genotype interact to influence fungal resistance could provide valuable insights for breeding programs and for the development of targeted postharvest management strategies. To address this gap, the present study investigates the response of two near isogenic pepper lines—one purple and one green at their economical ripeness—to B. cinerea, A. alternata and Fusarium culmorum infection at both economically and biologically ripe stages. Disease progression was assessed by phenotyping and by qPCR, while changes in metabolite composition were analyzed by spectrophotometer and by HPLC.

We hypothesized that fruits with higher anthocyanin and therefore higher total polyphenol contents would show greater tolerance to these fungal infections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

Samples of Capsicum annuum var. cerasiforme NILs were collected from greenhouses in Szentes, Hungary, maintained by Gábor Csilléry. One of the NILs is purple (labeled as Purple or P) at economical ripeness and matures into a red color (labeled as Red from Purple or RP); the other NIL is green (labeled as Green or G) at economical ripeness and matures into a red-colored fruit (labeled as Red from Green or RG). Fruits both at economical ripeness (ER) and at full biological ripeness (BR) were selected based on consistent maturity levels, uniform appearance and no visible physical defects. Upon harvest, the fruits were surface sterilized with 3% v/v sodium hypochlorite for 20 min and rinsed with sterile water; then, they were used immediately for the pathogen growth and inoculation tests.

2.2. Pathogen Assays

2.2.1. Pathogen Growth Tests In Vitro

For growth tests, pathogens—B. cinerea NCAIM (National Collection of Agricultural and Industrial Microorganisms) F.0075 and our own isolates of F. culmorum and A. alternata isolated and identified from decayed tomatoes and maintained in our laboratory—were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates (VWR® Chemicals, Leuven, Belgium) supplemented with 50% pepper juice, made by homogenizing approximately a kilogram of deveined and deseeded pepper pods followed by centrifugation and filtration. For the control, plain PDA was used. Five µL spore suspension was pipetted into the center of the plates. The spores were collected from 7 to 10 day-old colonies and set to a spore count of 2 × 106/mL with physiological salt solution with a hemocytometer. The plates were kept at 28 °C and mycelia growth was measured in every 8–10 h for a period of approximately 3 days. Each plate was made in three replicates.

2.2.2. Artificial Infection Studies In Vivo with B. cinerea, F. culmorum and A. alternata

Parallel to the in vitro growth tests, artificial infection studies were carried out. For this, the pepper fruits were divided into four color groups corresponding to the two phenophases. Each batch contained 10 fruits, and each fruit was wounded with a sterile scalpel in a single location, forming an ‘X’ of 2 mm wide and 2 mm deep, onto which 5 µL spore suspension as described above was pipetted. Non-inoculated but wounded fruits (mock-infected) served as the control. Fruits were kept at 25 °C in a Memmert type HPP 260 growth chamber in sterile containers and aerated in every 24 h. The samples were evaluated at 13 days post infection (dpi). The fruits evaluated were those that exhibited browning, sunken lesion or mycelia growth at the point of inoculation. For the phenotypic evaluation of infection severity (%), to calculate the size of the lesions or mycelia growth compared to the size of the fruits’ surface area, we used Fiji (ver. 2.17.0), an image processing software [].

To complement the phenotypic evaluation, further quantification of the pathogen growth was measured using qPCR approach. For qPCR, the inoculated fruits were freeze-dried and homogenized. DNA was extracted using a Macherey-Nagel Nucleospin Plant II Kit, Düren, Germany. For the qPCR 50 ng template, DNA was used to determine the ratio of fungal pathogens to the pepper genomic DNA. Primer pairs were designed based on the following sequences, for A. alternata GenBank accession LR778188.1 (A.alt F: CGAATGTTTGAACGCACATTG, A.alt R: CGCTCCGAAACCAGTAGG), for F. culmorum GenBank accession LT548325.1 (F.cul F: CACCGTCATTGGTATGTTGTCACT, F.cul R: CGGGAGCGTCTGATAGTCG) and for pepper gDNA GenBank accession XM_016716654.2 (Act F: GGACTCTGGTGATGGTGTCAGC, Act R: GTCCCTGACAATTTCCCGCTCAG) was used. For B. cinerea (B.cin F: ATTCCACAATATGGCATGAAATC, B.cin R: ATGTTATCTCATGTTATCTC) the primer sequences were adapted from the study of Zhang et al. (2013) []. For the qPCR, a PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania) was used with a standard cycling with the annealing set to 60 °C in a real-time PCR thermal cycler qTOWERiris (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany).

2.3. Analytical Measurements

2.3.1. Sample Preparation for Analytical Measurements

Infected peppers were compared to their mock-infected counterparts in terms of their total polyphenolic content (TPC) and antioxidant capacity (FRAP). For the sample preparation the homogenized freeze-dried samples were used. For the extractions, 60:39:1% v/v methanol/distilled water/formic acid was mixed with freeze-dried pepper powder.

2.3.2. Total Polyphenolic Content (TPC) and Antioxidant Capacity (FRAP) Measurements

The TPC was measured according to Singleton and Rossi (1965), at λ = 760 nm with a Hitachi U-2900 spectrophotometer in three repetitions []. TPC was calculated based on the calibration curve of 0, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 30 µg/mL gallic acid, and the results are expressed as mg gallic acid equivalent (Ga)/g dry weight. FRAP was measured following Benzie and Strain (1996), at λ = 593 nm with a Hitachi U-2900 spectrophotometer in triplicates []. The results are expressed in µmol ascorbic acid equivalent (As)/g dry weight, calculated against the calibration curve of 0, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 30 µmol/l ascorbic acid.

2.3.3. HPLC Determination of Phenolics and Vitamin C

The evaluation of the Vitamin C, anthocyanin and polyphenolic composition of the samples was performed by a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-diode-array detector (DAD) injection to identify changes in the compounds in each color group and each phenophase upon infection by B. cinerea. The extraction of the samples was performed by mixing 0.5 g of freeze-dried pepper samples with 25 mL of 70:30 v/v% 3% metaphosphoric acid/methanol. The mixture was shaken for 15 min at 300 rpm followed by an ultrasound bath for 5 min, centrifugation at 5000× g for 5 min, then filtration through a 0.22 µm pore sized syringe filter into glass vials.

For the measurements, an HPLC system (Hitachi Chromaster, Tokyo, Japan) with the following column type was used, Supelco Ascentis® Express 90 Å C18-PCP (St. Louis, MO, USA) 15 cm × 4.6 mm, 2.7 µm, with gradient elution of 1% ortho-phosphoric acid (A) and acetonitrile (B). The gradient elution started with 1% B in A, changed to 20% B in 20 min, remained isocratic for 10 min, changed to 30% B in 5 min, remained isocratic for 10 min, and turned to 1% B in 5 min. The DAD detection was between 190 nm and 700 nm. The operation and the data processing were performed using EZChrome Elite software (ver. 3.3.2). The quantification was based on recording the area at the maximum absorbance wavelength of each compound and relating it to the standard solutions acquired by Sigma-Aldrich via Merk (Budapest, Hungary). In those cases when a standard was not available, the compounds were putatively identified based on their spectral characteristics, chromatographic behavior and the literature data. The results are expressed as μg/g dry weight. For the measurements, four biological replicates were applied.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

For the descriptive statistics we used the IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0.1.0 software. Analysis of variance (one way or multiple) was applied to assess the statistical significance between the different color and maturity groups in terms of pathogen growth and inoculation tests, as well as total polyphenolic content and total antioxidant capacity measurements. Where a statistically significant effect was found (p-value < 0.05), Tukey’s test or Wald Χ2 test were further used.

Further analyses were conducted with the open source statistical program R (version 4.5.0). Data import and cleaning were handled with readxl, dplyr, tidyr and tibble. Statistical computations relied on base R together with dplyr; compact display of multiple-comparison results used multcompView. General plots were produced with ggplot2; figure alignment used cowplot, patchwork and grid packages. Heatmap was generated with ComplexHeatmap, with color mapping and track annotations supported by the circlize package. Image post-processing for figure assembly used png and magick packages.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pathogen Growth Tests In Vitro

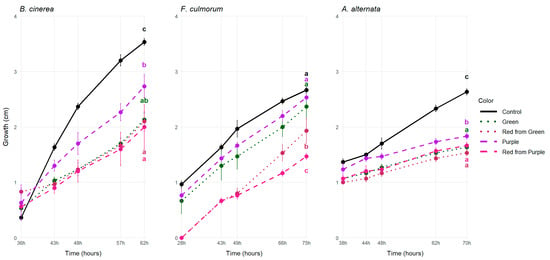

Anthocyanins have been associated with reduced susceptibility to B. cinerea in the case of grapes [] and tomatoes [,]. To test the hypothesis that anthocyanins may exert a protective role against storage pathogens B. cinerea, F. culmorum and A. alternata in the case of pepper, these pathogens were grown on a PDA medium supplemented with the economically ripe green and purple pepper juice and on a media supplemented with their biologically ripe red counterparts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean colony growth (in cm) on PDA supplemented with 50% sterile pepper juice at the last sampling date. The different lower case letters with matching colors mean significant statistical differences (p-value < 0.05) among the control (plain PDA), purple, green, red from green and red from purple pepper juices in three replicates.

Interestingly, fungal growth was the strongest on the purple pepper juice-supplemented media after the control, and the least amount of growth was measured in the case of the biologically ripe pepper juices-supplemented media (Figure 1). In the case of Botrytis, the growth on the purple media was 26% greater compared to the red from green one, while in the case of the Fusarium it was 23% greater, and this difference was the smallest in the case of Alternaria, where the growth on the P media was only 13% greater than on the RG media (Figure 1).

Overall, addition of the filtrates to the media did hinder the growth of the pathogens compared to the control. This effect was significant in the case of B. cinerea and A. alternata, indicating the presence of molecules that are active against the fungal pathogens in vitro as well, although we could not detect strong antifungal activity in the anthocyanin-rich media.

This aligns with Zhang et al.’s (2013) study, where B. cinerea growth was not inhibited on either the red or the purple tomato juice-supplemented media. Hence, they concluded that resistance against the pathogen requires living cells []. However, one in vitro study indicated that addition of anthocyanins cyanidin-3-glucoside or pelargonidin-3-glucoside to PDA media could effectively reduce the growth of B. cinerea in higher concentrations []. Therefore, we hypothesize that the enrichment of the media with the anthocyanin-rich pepper filtrate may not have reached the minimum inhibitory concentration. Similarly to our case, where only the purple extract-supplemented media differed, when Alternaria was grown on immature green and red ripe pepper extract-supplemented media, there was no significant difference in pathogen growth in between the fruit colors [].

3.2. Artificial Infection Studies In Vivo with B. cinerea, F. culmorum and A. alternata

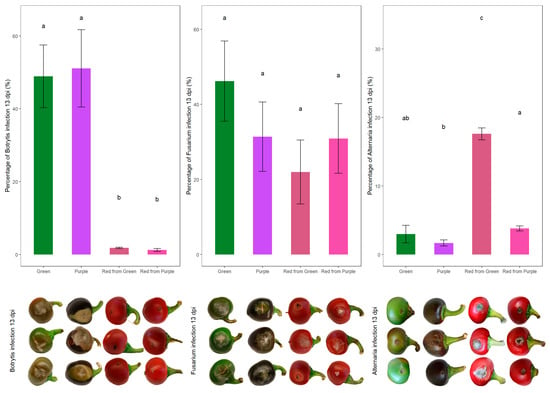

Although in vitro assay provided a controlled environment to test the antifungal activity of fruit extracts, it did not allow for the study of active host responses occurring in whole fruits. Therefore, in vivo artificial infection experiments were conducted in parallel to the in vitro assays to further evaluate the effectiveness of the NILs against storage pathogens (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of infection of B. cinerea, F. culmorum and A. alternata after 13 days post-inoculation (dpi) of infected plants from each color group (n = 10); different lower case letters mean significant statistical differences (p-value < 0.05). The lower images display the most common phenotype of infection appearing at 13 dpi.

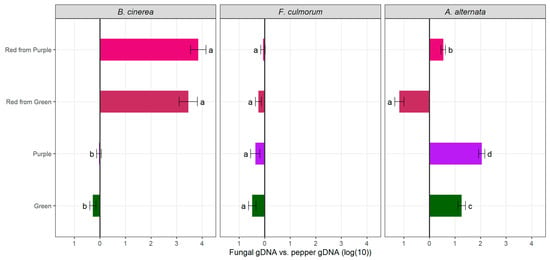

For B. cinerea, the infection phenotype yielded unexpected results (Figure 2). On the ER fruits—green and purple—severe symptoms of gray mold developed around the site of the inoculation, on the other hand, the infection was less severe on the BR red counterparts. The average infection percentage of the economically ripe fruits was 50.03%, as opposed to 1.54% in the biologically ripe fruits. In our case, necrotic lesions at the site of infection, even at 13 dpi, were characteristic only of the BR red pepper fruits (Figure 2). We could not conclude the beneficial effects of anthocyanins against the pathogen infection, as qPCR with the DNA extracted from the infected fruits at 13 dpi also confirmed that there was significantly less Botrytis growth on the RP and RG fruits than on the G and P economically ripe fruits (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Quantitative PCR at 13 dpi of each color group (n = 3); fungal growth was calculated by comparing the ratio of Botrytis, Fusarium or Alternaria DNA to pepper DNA. Different lower case letters mean significant statistical differences (p-value < 0.05) between the groups, bars to the left represent fungal gDNA excess and bars to the right represent pepper gDNA excess.

Infection carried out with Fusarium yielded uniform results across color groups and phenophases, by both phenotypic evaluation and qPCR (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Although anthocyanins have been hypothesized to act against Fusarium infections, in our case the averages of infection percentages did not confirm this hypothesis; G: 46.21%, P: 31.37%, RG: 22.04% and RP: 30.86% (Figure 2).

Inoculating the NILs with A. alternata resulted in more severe infections at the biologically ripe phenophase; however, based on the phenotypic evaluation of disease severity, the green-colored economically ripe fruits’ infection rate did not differ significantly from the ripe RP fruits’ infection rate (Figure 2). The average infection percentages at 13 dpi were G: 2.98% and P: 1.68%; the average of the economically ripe fruits: 2.33%, RG: 17.59% and RP: 3.80%; and the average of the biologically ripe ones: 10.69% (Figure 2). Although the NILs used in this study share a common genetic background, they differ in their anthocyanin content, resulting in a somewhat distinct biochemical composition; therefore, it is also interesting to compare the averages of the two NILs; the purple ones yielded an infection percentage of 2.75%, whereas the green ones yielded an infection percentage of 10.28%.

According to the generalized linear model (Gamma with log link), there was a significant effect of the variation sources: genotype (Gt), phenophase (Pp) and the interaction of Gt × Pp (Table 1).

Table 1.

Infection percentages of the three storage pathogens analyzed using a generalized linear model; fixed factors were the genotype (Gt), phenophase (Pp) and their interaction (Gt × Pp).

For Botrytis, infection severity was primarily influenced by phenophase (Χ2 = 1185.514, p < 0.001), whereas genotype alone had no significant effect (Χ2 = 2.457, p < 0.117); however, the genotype × phenophase interaction showed a weaker but statistically significant impact (Χ2 = 4.028, p < 0.045).

In the case of Fusarium, no significant differences were attributable to genotype alone, while both phenophase (Χ2 = 7.098, p < 0.008) and the genotype × phenophase interaction (Χ2 = 6.496, p < 0.011) exerted significant effects on disease intensity. These tendencies can also be seen in Figure 2—where the economically ripe fruits’ average infection percentage was 38.79%, whereas the biologically ripe fruits’ was 26.45%—and can be statistically proven by the X2 test (Table 1).

For Alternaria, infection severity was significantly affected by genotype (Χ2 = 101.634, p < 0.001), phenophase (Χ2 = 154.047, p < 0.001) and their interaction (Χ2 = 21.218, p < 0.001), indicating that both main factors and their combined effect played a decisive role (Table 1).

The ripening-dependent susceptibility of tomatoes to B. cinerea is well-established. This increased susceptibility has been linked to ripening regulatory pathways, such as the NOR transcription factor []. Further, transcriptomic and proteomic studies have revealed that defense-related proteins are less abundant in mature green (MG) fruits than in red ripe (RR) fruits [,]. Moreover, B. cinerea can accelerate host ripening, thereby facilitating colonization []. Upon infection with B. cinerea and F. acuminatum, the pathogens were able to grow on the surface of MG tomato fruits, but only the RR fruits showed symptoms of rot [,]. When MG tomato fruits were inoculated with B. cinerea at 1 dpi, the necrotic lesions were limited to the site of infection; however, RR fruits started to develop tissue rot and fungal growth. This localized necrosis could be attributed to oxidative burst, as hydrogen peroxide accumulation was detected 3–4 cell layers deep around the infection site []. Differential expression studies revealed that during maturing from MG to RR, the expression of defense-related genes undergoes changes; for example, the expression of genes that are involved in the mediation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels declines. This reduced expression could lead to a reduction in preformed defense as a result of losing control of ROS levels []. Our results contradict studies carried out with purple tomatoes, where anthocyanin accumulation has been directly linked to extended shelf life and enhanced resistance to B. cinerea. Anthocyanin-rich tomato fruit exhibited delayed overripening and reduced susceptibility to gray mold [], and a further study reported that anthocyanin-rich lines displayed a doubled shelf life compared to the wild-type tomatoes, as anthocyanins added to the overall antioxidant capacity, therefore contributing to the reduction in oxidative stress [].

According to Le et al. (2013), who studied postharvest B. cinerea infection in pepper cultivars at different ripening stages, in the cultivar ‘Papri Queen’, the strongest symptoms occurred at the breaker red stage, whereas in the ‘Aries’ cultivar, the fully ripe fruits developed disease symptoms more rapidly []. This indicates that in pepper, infection severity is not strictly correlated with ripening stage but is also strongly influenced by genotype []. Additionally, peppers infected with Colletotrichum sp. also exhibited genotype and ripening stage-dependent differences in pepper fruit responses, with unripe fruits showing larger lesion diameters on average []. Consistent with this, our observation of higher infection rates in the economically ripe stage compared with the biologically ripe stage likely reflects genotype–phenophase interactions rather than a simple ripening-dependent trend.

Effects of anthocyanins on the growth and mycotoxin production of F. culmorum was studied by Trávníčková et al. (2024) in the case of differently colored wheat grains. Red grains showed the lowest deoxynivalenol (DON) content; however, this was not consistent across all crop years, while grains with purple pericarp exhibited a constant and moderate level of DON across all studied crop years []. This was also confirmed by Gozzi et al. (2023), who found that blue wheat grains—anthocyanins accumulating only in the aleuron—exhibited higher susceptibility to Fusarium than those where the anthocyanin pigmentation was characteristic to the pericarp []. Further, when the effect of anthocyanidins was studied on the conidial growth on Fusarium avenaceum, cyanidin 3-O-glucoside and delphinidin 3-O-glucoside were found to significantly reduce conidial germination []. Therefore, it was hypothesized that the different accumulation pattern of these pigments might act against the early stages of infection; however, in our study, this phenomenon was not observed, although peppers have also been found to accumulate delphinidins in their pericarp []. Anthocyanin accumulation in peppers has also been studied in relation to Phytophthora capsici infection. When the CaMYB gene—a key factor in the anthocyanin biosynthesis of pepper—was silenced, symptoms of P. capsici infection were quicker to develop on the silenced plants’ leaves than on the control, indicating that anthocyanins might be functioning as a first line of defense [].

The ripening-dependent manner of Alternaria infection was also studied in tomatoes; upon comparing MG and RR phenophases of three varieties kept at 25 °C for 10 days, the RR fruits showed the quickest progression of disease; on the contrary, the MG stage of ‘Charleston’ and ‘Geronimo’ varieties showed no lesions during the storage period []. The phenophase dependency of A. alternata infection in pepper fruits has been described previously; no lesions were evident after 10 dpi in the mature green fruits; however, with as little as 10% red coloration on the fruits, lesions were formed []. The ripening stage dependency of Alternaria infection in peppers was also studied in a temperature-dependent manner []. In cold storage, the symptoms and lesion diameter were similar in the economically and biologically ripe fruits; however, at 22 °C lesions were significantly larger on the ripe fruits []. This is in line with our study, as the symptoms of the fruits kept at 25 °C were more advanced on the red ripe fruits, while only smaller lesions were observable on the G and P fruits (Figure 2). This was confirmed by qPCR analyses as well, where we detected higher fungal load in the biologically ripe red peppers, with the RG exhibiting the most fungal DNA compared to the pepper DNA, which also aligns with the phenotypic evaluation of the disease severity (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

3.3. Total Polyphenolic Content, Antioxidant Capacity and Anthocyanin Content of the Infected Pepper Fruits

As the differences could be attributable to the metabolic changes occurring during ripening, the total polyphenolic content and total antioxidant capacity were measured by spectrophotometric methods and by HPLC, together with the total monomeric anthocyanin content. Measurements were carried out at the time of harvest (Week 0) and at 13 days post infection with the three pathogens, respectively, and mock-infected plants were used for the control (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antioxidant capacity (FRAP), anthocyanin content (TMA) and total polyphenolic content (TPC) of the samples measured by spectrophotometry and HPLC at the time of harvest (Week 0) and at 13 days post infection.

Both with the spectrophotometric methods and with the HPLC, a similar trend was visible in terms of changes in FRAP, TMA and TPC values (Table 2). At the time of the harvest, the P fruits showed the highest values for all the tested parameters; TPC: 610.69 ± 54.16 mg GA/g DW, which showed a statistically significant difference from the G, RG and RP samples. As for the FRAP of P samples: 293.76 ± 27.50 µmol As/g DW differed significantly from the rest of the samples, and the same trend was also observed for the HPLC measurement, where the total polyphenolics measured was higher and the difference compared to the rest of the samples was statistically significant. At Week 0, statistically significant differences were also scored between the phenophases; in the case of FRAP, in the economically ripe fruits, we measured 256.76 ± 1.66 compared to the biologically ripe 189.07 ± 9.59 µmol As/g DW. There was a significant decrease as well in the TPC values when measured by HPLC, although when spectroscopy was applied, the decrease in the ripened fruits was only trend-like. The TPC measured using a spectrophotometric method showed a greater decrease in the purple samples compared to the green ones, whereas this was the contrary when TPC was measured using the HPLC method; nevertheless, there was a decrease in the TPC from Week 0 to the control stage (mock-infected plants stored at 25 °C for 13 days) (Table 2). The 13-day storage period also affected the anthocyanin levels; however, the decrease was not statistically significant (Table 2). FRAP values changed according to the phenophase studied; the economically ripe fruits showed a significant decrease, whereas a trend-like increase was detected in the biologically ripe fruits (Table 2).

In the case of the infections with the three storage pathogens, FRAP, TMA and TPC values all differed significantly from the Week 0 data, and most of them showed significant differences compared to the control data as well. There were only two cases where there was only a trend visible; TMA of the RP in the case of the control (17.81 ± 4.81 µg/g DW) did not differ from the Botrytis-infected fruits (2.85 ± 0.71 µg/g DW) and the TPC measured by HPLC in the case of the control RG fruits (468.98 ± 34.65 µg/g DW) was not significantly different from that of the Botrytis-infected fruits (326.88 ± 11.25 µg/g DW), although they differed from the Week 0 data (Table 2.).

The correlation analysis showed high association between the phenophase and the infection percentage of the Alternaria (r = 0.646), where the biologically ripe phenophase showed more fungal growth than the economically ripe fruits (Figure 2, Table 3). The ripening showed a negative correlation with FRAP (r = −0.200), meaning that the biologically ripe fruits possessed lower antioxidant capacity (Table 2 and Table 3). The FRAP and TPC values showed a strong positive association in each case studied (r = 0.830, r = 0.835, r = 0.834, in the case of the Alternaria, Fusarium and Botrytis, respectively). The infection percentage showed a negative correlation with the genotype (r = −0.389), indicating that the green NIL was more prone to Alternaria infection (Figure 2, Table 3).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation between the variables: total polyphenolic content (TPC) measured by two methods, antioxidant capacity (FRAP), anthocyanin content (TMA), infection percentages and the genotypes studied.

Regarding the Fusarium data, a negative correlation was scored between the phenophase and infection percentage (r = −0.531). As Figure 2 shows, the infection was more severe in the case of the economically ripe fruits on average. The TPC and FRAP values showed a positive association with the genotype, indicating that the purple NIL exhibited higher scores for these measured indices (Table 2 and Table 3).

In the case of the Botrytis data, a negative correlation was observed between phenophase and infection severity (r = −0.974), with economically ripe fruits developing greater fungal growth. TPC (r = −0.597) and TMA (r = −0.462) measured by HPLC showed a negative correlation with the phenophase, indicating that the biologically ripe fruits contain smaller amounts of these compounds. The genotype studied showed a strong positive correlation with the measured variables, TPC (r = 0.208), FRAP (r = 0.202), HPLC–TPC (r = 0.526) and HPLC–TMA (r = 0.519), indicating that these compounds are more abundant in the purple NIL. The two different approaches for the TPC measurements also showed a strong correlation (r = 0.453), and the amount of anthocyanins measured also correlated with the measured polyphenolics (r = 0.462 measured by spectrophotometer, r = 0.858 measured by HPLC) and with the antioxidant capacity (r = 0.458). Although TMA showed a strong positive correlation with the infection percentage of Botrytis (r = 0.486), as Figure 2 shows, the purple NIL was the most severely infected fruit (Figure 2, Table 3).

Our results align with Marin et al. (2004), who also observed decreasing polyphenolic content during ripening []. As for the differences between the Week 0 and control data, Garra et al. (2020) found that the amount of polyphenols during storage is affected by genotype, as in some accessions there was a 32% increase, while others showed a 22–24% decrease during storage []. When infecting pepper cultivars with Alternaria, Tukuljac et al. (2023) obtained genotype-dependent responses in terms of TPC and antioxidant capacity, with ‘Amfora’ and ‘Una’ showing an increase, whereas in ‘Kurtovska kapia’ TPC remained unchanged and the antioxidant capacity showed a decrease upon infection []. Upon investigating the effect of Alternaria on the antioxidant responses of tomato, Meena et al. (2017) found a significant decrease in the TPC with the dpi []. A study conducted by Tzortzakis (2019) found that FRAP showed an increase, while the total phenolics did not showing significant differences between the Botrytis-infected tomatoes and the control []. These differences may arise from the different experimental settings in terms of storage time, plant material or pathogen strain used. For example, in terms of storage time, as Bui et al. (2019) concludes, Vitamin C levels of infected apples were comparable to the control after 5 days, but showed a decrease after 14 days of incubation [].

3.4. HPLC Determination of Phenolics and Vitamin C of the Botrytis-Infected Fruits

As Botrytis infection showed contradicting results with the purple tomato studies, subsequent biochemical analyses focused on this pathogen. To gain a deeper understanding of the changes in polyphenolics upon Botrytis infection, HPLC measurement was carried out (Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 4.

Putative identification of compounds of the purple NIL at two phenophases at Week 0 and after 13 dpi: control (mock-infected) and Botrytis-infected fruits.

Table 5.

Putative identification of compounds of the green NIL at two phenophases at Week 0 and after 13 dpi: Control (mock-infected) and Botrytis-infected fruits.

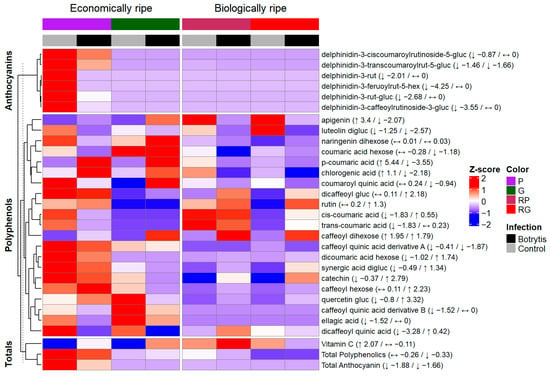

The changes in the metabolite levels were analyzed by pairwise column mean comparisons using two-sample t-tests (two-sided, equal variances assumed), with a significance level of p < 0.05. Three aggregated values, Vitamin C, total polyphenolics and total anthocyanins, were analyzed. We identified a phenophase-dependent change in the case of Vitamin C: in the G and P fruits the content of it increased significantly compared to the control, whereas in the case of RP no significant change was detected, and in the RG fruits, a significant decrease was found (Table 4 and Table 5). This ripening stage difference in the Vitamin C content may arise from the 13-day-long storage at 25 °C and from the Botrytis infection itself as well, as Botrytis accelerates ripening processes, and with ripening the Vitamin C content increases (Table 4 and Table 5). Meanwhile, in the RG fruit, a strong decrease was experienced as expected upon oxidative stress. In terms of the anthocyanin content, a strong decrease in the total amount of anthocyanins was measured in both phenophases of the NILs (−1.88 and −1.66) (Figure 4). A similar reduction was also experienced in the individual anthocyanin compounds (Figure 4). We observed a severe degradation—a 73% reduction compared to the control in the case of the P fruits—of these compounds (Table 4, Figure 4), which can be explained by the oxidative degradation of these metabolites by the pathogen.

Figure 4.

Heatmap (Z-score) representing the differences in the amount of the different compounds between the Botrytis-infected (black) and the mock-infected (gray) control group; purple color (P) represents the economically ripe purple NIL, green color (G) represents the data of the economically ripe green NIL, maroon (RP) represents the Red from Purple biologically ripe stage of the purple NIL, red (RG) represents the Red from Green biologically ripe stage of the green NIL and arrows and numbers in the brackets indicate the direction of the fold of change in the Z-score related to the metabolites measured in the economically ripe stage or at the biologically ripe stage. hex: hexoside, rut: rutinoside, gluc: glucoside.

Ascorbic acid is one of the most well-known and major antioxidant molecules of peppers, acting as a key substrate for neutralizing reactive oxygen species []. A decrease in the amount of it upon pathogen infection has already been demonstrated in studies involving strawberry [], Arabidopsis [] and apple []. As Meena et al. (2017) reports, ascorbic acid was also depleted after A. alternata infection [], and this depletion was also confirmed in the case of peppers in a genotype-dependent manner []. Studying the polyphenolics, Zimdars et al. (2017) found that besides caffeic and ferulic acids, malvidin-3-O-glycosides are also oxidized rapidly by the secretomes of the pathogen []. On the other hand, when white-skinned berries were analyzed after Botrytis infection, Blanco-Ulate et al. (2015) found that the anthocyanin accumulation was induced, especially in terms of the production of cyanidin and delphinidin glycosides []. This is unlike Echnenique-Martínez et al.’s (2023) study, where upon infecting the strawberries with Botrytis there was a significant reduction in the amount of pelargonidin-3-glucoside []. A study carried out on Botrytis-infected grape berries showed that upon infection, the amount of anthocyanins in the skin decreased by more than 80% []. Gimenez et al. (2023) studied the effect of active laccase extracts obtained from a Botrytis isolate on different anthocyanins and found that petunidin-3-O-glucoside and delphinidin-3-O-glucoside were the fastest to be degraded by the enzyme []. In our case, in the P and RP fruits, the most prevalent anthocyanin was the delphinidin-3-transcoumaroylrutinoside-5-glucoside; the amount of this compound in the infected fruits decreased by approximately 70% compared to Week 0, and by approximately 63% compared to the control fruits in the P fruits (Table 4, Figure 4).

An overall decreasing trend was observed in the aggregated TPC value; however, some metabolites showed an increase upon infection, either at both phenophases or in a single phenophase (Figure 4). For example, amongst the simple hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives, coumaric acids showed different responses to the infection according to the phenophase studied. The greatest difference was recorded in the case of p-coumaric acid, with higher values measured in the economically ripe phenophase. As for the more complex chlorogenic-type derivatives, there was a also difference recorded between the phenophases in the response of chlorogenic acid levels to the pathogen infection. Other flavonoids, such as the luteolin diglucoside, showed a decrease, while the levels of rutin remained unchanged in the P and RP fruits.

In the case of the polyphenolics, the trend is not so clear; for instance, Muñoz Aries et al. (2021) detected higher amounts of polyphenols in the inoculated Rubus glaucus fruits, and the amounts of them correlated with the Botrytis infection severity []. However, when the amount of polyphenolics was studied in relation to the days post-inoculation, Wang et al. (2012) found a significant decrease in TPC in each strawberry genotype studied [].

3.5. Relationship Between Botrytis Infection Severity and Metabolite Levels

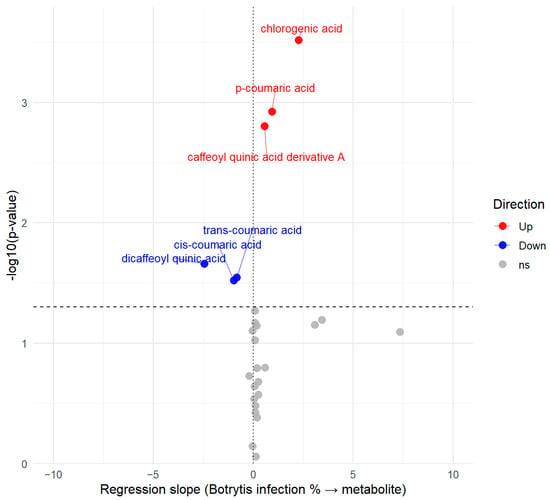

Since infection severity was also evaluated, it was possible to examine the relationship between the level of infection and the abundance of individual compounds of the Botrytis-infected batch. This relationship is illustrated in a volcano plot (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Volcano plot representing the relationship between the Botrytis infection and the metabolites measured, with red metabolites showing positive correlation, blue metabolites showing negative correlation with the infection percentage and gray color showing a non-significant (ns) relationship.

Compounds that did not show a significant association with infection severity are located underneath the vertical threshold line displayed in gray. The volcano plot highlights several phenolic acid compounds located above the significance threshold line that were modulated by the Botrytis infection. Chlorogenic acid, p-coumaric acid and a caffeoyl quinic acid derivative increased with infection (positive slopes in red), whereas cis- and trans-coumaric acid and dicaffeoyl quinic acid decreased (negative slopes indicated with blue). For metabolites exhibiting statistical significance, the magnitude of their deviation was also taken into account, as reflected by the distance from the central vertical line in the volcano plot.

To enable a more detailed assessment of the amount of metabolites across the infection levels, the samples were further grouped into three categories according to Botrytis infection percentages: low (0–15%), moderate (15–45%) and severe (>45%). Therefore, the influence of Botrytis infection on the metabolic composition was evaluated using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), allowing for parallel analysis of multiple metabolites. The grouping of metabolites was similar to the one used for the creation of the heatmap: the totals and the anthocyanins were grouped. The polyphenolics were, however, separated into three blocks: simple hydroxycinnamic acid derivates, more complex chlorogenic-type derivatives and other flavonoids.

MANOVA showed that the Botrytis infection had no significant effect (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.293, F(6,12) = 1.693, p = 0.206) on the totals (Vitamin C, total anthocyanin and total polyphenolics). Upon focusing on each component separately, no significant differences were scored either, although the total polyphenolics showed a trend-like pattern with regard to the infection groups (p = 0.061). Analyzing the delphinidin derivatives group (Wilk’s Lambda = 0.229, F(8,10) = 1.360, p = 0.318) showed that there was no significant effect on this group, although the amount of these compounds decreased significantly upon infection (Table 2 and Table 4, Figure 4). However, this effect was not significant compared to the three infection categories, meaning that Botrytis infection, regardless of severity, leads to the degradation of these compounds. Testing the hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives, the severity of Botrytis infection was not significant in this group of metabolites (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.006, F(4,2) = 5.951, p = 0.149). However, the overall effect was not significant. When analyzed separately, several compounds showed trend-like differences between infection groups: caffeoyl quinic acid derivative A (p = 0.057), caffeoyl quinic acid derivative B (p = 0.108), p-coumaric acid (p = 0.069), cis-coumaric acid (p = 0.136) and trans-coumaric acid (p = 0.106). MANOVA indicated a significant overall effect (Wilk’s Lambda = 0.000, F(8,2) = 26.230, p = 0.37) of infection groups on the chlorogenic-type derivatives. In our study, the amount of CGA significantly increased in the P and G fruits upon infection, but showed a decrease in the biologically ripe PR and PG fruits (Figure 4). Further, in the univariate tests, chlorogenic acid (p < 0.001) and dicaffeoyl-glucoside (p = 0.002) were significantly affected by the infection groups, and there was also a trend visible for the dicaffeoyl quinic acid (p = 0.077). As for the rest of the compounds, MANOVA showed no significant overall effect (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.000, F(6,2) = 18,421, p = 0.052). When tested separately, quercetin glucoside was greatly affected by the infection groups (p < 0.001). In the case of rutin, there was a trend-like manner (p = 0.055); however, the other metabolites, catechin, naringenin dihexose and apigenin, as well as the luteolin diglucoside, were not significantly affected by the infection groups. These patterns indicate that infection-induced changes in hydroxycinnamic acids may be more relevant for postharvest defense in pepper than changes in bulk anthocyanin levels.

Some of these compounds have already been proven not only to be responsive, but also to be effective against infection; for example, Liu et al. (2020) found that p-coumaric acid significantly inhibited the mycelia growth of Botrytis in sweet cherries []. Glazener (1982) found an increase in this compound after inoculating young tomato fruits with Botrytis []. Chlorogenic acids (CGAs) are well-known to inhibit spore formation and reduce the fungal growth of F. solani and B. cinerea [] by disrupting the cell membrane []. López-Gresa et al. (2011) found that upon infecting tomatoes with Pseudomonas syringae, there was an accumulation in CGAs []. Exogenous application of quercetin and cathecin hindered the germ tube and mycelia growth of Botrytis []. However, in our case, quercetin was greatly affected by the infection groups. This could be explained by the laccases produced by Botrytis; as Quijada-Morin et al. (2018) found, these laccases and peroxidases can detoxify or degrade these hydroxycinnamates. In their study, they determined that the best substrate was quercetin []. On the other hand, when rutin was tested against Alternaria, F. solani and B. cinerea, it was found that it was only effective against the growth of B. cinerea, as it stimulated the formation of conidia in the case of Alternaria and F. solani [].

Overall, this study combines phenotypic, spectrophotometric and targeted metabolomic analyses to assess how different pigment composition, phenophase and genotype affect the responses of pepper fruits to major postharvest fungal pathogens. However, there are several limitations of this work, i.e., the experiments were performed under controlled laboratory conditions using artificial inoculation and a single storage temperature, which may not fully represent the variable environments of postharvest handling and distribution. Further, only C. annuum var. cerasiforme NILs were used, and responses may differ in other varieties. Moreover, the strains were not isolated from the used NILs, which may slightly limit the representativeness of the infection dynamics observed. Detailed metabolite profiling was carried out only for B. cinerea, while A. alternata and F. culmorum were examined primarily at the phenotypic level. Future studies should extend metabolomic analyses to other pathogens, storage periods or temperatures, as well as genotypes. It is also important to integrate transcriptomic analysis to better link metabolic changes with gene expression. Functional validation of key metabolites—such as chlorogenic and p-coumaric acids—in antifungal defense will be essential to clarify their exact roles so that they can serve as biochemical markers for breeding programs targeting improved postharvest disease tolerance in peppers. These findings may help breeding efforts aimed at combining pigmentation and nutritional value with improved resistance against storage pathogens, thus supporting a more sustainable postharvest management strategy that relies on natural, polyphenol-based defenses rather than synthetic fungicides.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that pepper susceptibility to postharvest pathogens is shaped primarily by ripening stage and genotype rather than by anthocyanin accumulation alone, in contrast to findings in tomato studies. Economically ripe fruits were more vulnerable to Botrytis cinerea, while biologically ripe fruits showed higher susceptibility to Alternaria alternata. Fusarium infections were not strongly influenced by pigmentation. Botrytis infection led to a marked depletion of total phenolics, antioxidant capacity, Vitamin C and anthocyanins. Multivariate analysis revealed that Botrytis infection percentage did not significantly alter the totals of Vitamin C, total anthocyanins and total polyphenols, indicating that their levels are altered by the infection itself and not by the severity of it, yet several individual metabolites showed correlation with infection severity. Chlorogenic acid and certain hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives (caffeoyl quinic acids, coumaric acids) and flavonoids such as quercetin-glucoside and rutin were affected by the severity of Botrytis infection. Total anthocyanin content and the delphinidin derivatives measured decreased upon infection; however, this effect was not significant in correlation with infection severity, indicating that Botrytis infection in a low, moderate or severe amount will lead to the degradation of these compounds. Therefore, although anthocyanins have been proven to be effective against B. cinerea infection in the case of purple tomatoes, we could not conclude the beneficial effects of these molecules against this pathogen in the case of pepper.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.K., Á.T. and Á.J.; validation, A.V. and A.S.; investigation, H.G.D.; data curation, J.B. and K.A.T.-L.; writing, Z.K., Á.T. and Á.J.; supervision, G.C.; funding acquisition, K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office of the Hungarian Government (grant no: RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00007 for Agribiotechnology and precision breeding for food security National Laboratory).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All of the data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office of the Hungarian Government (grant no: RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00007 for Agribiotechnology and precision breeding for food security National Laboratory) and by the EKÖP-MATE/2024/25/K university research Scholarship Programme of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Author Gábor Csilléry is employed by the company PepGen Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A. alternata | Alternaria alternata |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| B. cinerea | Botrytis cinerea |

| BR | Biological Ripeness |

| CGA | Chlorogenic acid |

| dpi | days post infection |

| ER | Economical Ripeness |

| F. avenaceum | Fusarium avenaceum |

| F. culmorum | Fusarium culmorum |

| F. solani | Fusarium solani |

| FRAP | Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| G | Green |

| Gt | Genotype |

| MANOVA | Multivariate Analysis of Variance |

| MG | Mature Green |

| NILs | Near Isogenic Lines |

| nd. | not detected |

| ns | not significant |

| P | Purple |

| P. capsici | Phytophthora capsici |

| PDA | Potato Dextrose Agar |

| Pp | Phenophase |

| qPCR | quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RG | Red from Green |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RP | Red from Purple |

| RR | Red Ripe |

| TFC | Total Flavonoid Content |

| TMA | Total Monomeric Anthocyanin Content |

| TPC | Total Polyphenolic Content |

References

- Karoney, E.M.; Molelekoa, T.; Bill, M.; Siyoum, N.; Korsten, L. Global research network analysis of fresh produce postharvest technology: Innovative trends for loss reduction. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 208, 112642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrios, G.N. Plant Pathology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Han, K.; Ma, W.; Zhang, J.; Xie, J. Exogenous Melatonin Application Enhances Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Fruit Quality via Activation of the Phenylpropanoid Metabolism. Foods 2025, 14, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahamad, S.; Asrey, R.; Vinod, B.; Meena, N.K.; Menaka, M.; Prajapati, U.; Saurabh, V. Maintaining postharvest quality and enhancing shelf-life of bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) using brassinosteroids: A novel approach. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 169, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Das, A.; Sarkar, B.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Adak, M.K. Modulation of secondary metabolism and redox regulation by exogenously applied glutathione improves the shelf life of Capsicum annuum L. fruit. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 212, 108789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathare, A.M.; Pawase, P.A.; Bora, P.P.; Rout, S.; Bashir, O.; Sharma, E.; Roy, S. Advances in packaging technologies for capsicum: Enhancing shelf life and post-harvest quality through packaging film and coating technologies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 163, 105140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, K.; Bhattacharjee, S.K.; Mudenur, C.; Ghosh, T.; Goud, V.V.; Katiyar, V. Development of antioxidant-rich edible active films and coatings incorporated with de-oiled ethanolic green algae extract: A candidate for prolonging the shelf life of fresh produce. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 13295–13313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limchoowong, N.; Sricharoen, P.; Konkayan, M.; Techawongstien, S.; Chanthai, S. A simple, efficient and economic method for obtaining iodate-rich chili pepper based chitosan edible thin film. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3263–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravallika, K.; Chakraborty, S. Comparative Effects of Steam, Microwave, and Pulsed Light Treatments on the Shelf Life of Fresh Red Chillies (Capsicum annum) at 28 °C and 4 °C. Food Humanit. 2025, 5, 100714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, T.R.; Gol, N.B.; Shah, K.K. Effect of postharvest treatments and storage temperatures on the quality and shelf life of sweet pepper (Capsicum annum L.). Sci. Hortic. 2011, 132, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Oh, S.-M.; Park, M.K.; Park, J.-D.; Ahn, J.H.; Sung, J.M. Enhancing quality and shelf life of fresh-cut Paprika (Capsicum annuum L.) using insulated packaging with ice packs. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 222, 113360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jiang, H.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. Advances in biochemical mechanisms and control technologies to treat chilling injury in postharvest fruits and vegetables. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 113, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, Y.; Wu, X.; Shi, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yue, X.; Xu, X.; Zuo, J.; Yuan, S.; Wang, Q. Rutin treatment delays postharvest chilling injury in green pepper fruit by modulating antioxidant defense capacity. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 230, 113753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanazzi, G.; Smilanick, J.L.; Feliziani, E.; Droby, S. Integrated management of postharvest gray mold on fruit crops. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 113, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xiao, C.-L. Phylogenetic, morphological, and pathogenic characterization of Alternaria species associated with fruit rot of blueberry in California. Phytopathology 2015, 105, 1555–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.; Van Kan, J.A.; Pretorius, Z.A.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Di Pietro, A.; Spanu, P.D.; Rudd, J.J.; Dickman, M.; Kahmann, R.; Ellis, J. The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.; Sharma, R. Postharvest diseases of fruits and vegetables and their management. In Postharvest Disinfection of Fruits and Vegetables; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi, H.; Masunaka, A.; Nomiyama, K.; Tomioka, K. Internal fruit rot of sweet pepper caused by Fusarium lactis in Japan and fungal pathogenicity on tomato and eggplant fruits. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2021, 87, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, A.; Kumar, A. Postharvest fruit rot of Bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.): Pathogenicity and Host range of Alternaria alternata. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 319, 112156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, G.K.; Adekunle, A.A.; Ogundipe, O.T.; Solanki, M.K.; Sadhasivam, S.; Sionov, E. Identification and toxigenic potential of fungi isolated from capsicum peppers. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampersad, S.; Teelucksingh, L. First report of Fusarium proliferatum infecting pimento chili peppers in Trinidad. Plant Dis. 2011, 95, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwomadu, T.I.; Mwanza, M. Fusarium fungi pathogens, identification, adverse effects, disease management, and global food security: A review of the latest research. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Yong, C.; Zhanquan, Z.; Boqiang, L.; Guozheng, Q.; Shiping, T. Pathogenic mechanisms and control strategies of Botrytis cinerea causing post-harvest decay in fruits and vegetables. Food Qual. Saf. 2018, 2, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, M.M.; Biles, C.L. Alternaria fruit rot of ripening chile peppers. Phytopathology 1993, 83, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Halim, G.; Chowdhury, M.; Hossain, M.; Rahman, M. Changes in physicochemical attributes of sweet pepper (Capsicum annum L.) during fruit growth and development. Bangladesh J. Agric. Res. 2014, 39, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusky, D.; Alkan, N.; Mengiste, T.; Fluhr, R. Quiescent and necrotrophic lifestyle choice during postharvest disease development. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2013, 51, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, N.; Kaur, C.; George, B.; Singh, B.; Kapoor, H. Antioxidant constituents in some sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes during maturity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantu, D.; Blanco-Ulate, B.; Yang, L.; Labavitch, J.M.; Bennett, A.B.; Powell, A.L. Ripening-regulated susceptibility of tomato fruit to Botrytis cinerea requires NOR but not RIN or ethylene. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150, 1434–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzman, R.A.; Tikhonova, I.; Bordelon, B.P.; Hasegawa, P.M.; Bressan, R.A. Coordinate accumulation of antifungal proteins and hexoses constitutes a developmentally controlled defense response during fruit ripening in grape. Plant Physiol. 1998, 117, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; An, H.; Guo, Y.-N.; Wang, Q.; Shang, Y.-Y.; Chen, M.-K.; Liu, Y.-X.; Meng, J.-X.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Wei, J. Anthocyanins from Malus spp. inhibit the activity of Gymnosporangium yamadae by downregulating the expression of WSC, RLM1, and PMA1. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1152050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Zhang, S.; Tsao, R.; Charles, M.T.; Yang, R.; Khanizadeh, S. In vitro antifungal activity and mode of action of selected polyphenolic antioxidants on Botrytis cinerea. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2010, 43, 1564–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassolino, L.; Zhang, Y.; Schoonbeek, H.j.; Kiferle, C.; Perata, P.; Martin, C. Accumulation of anthocyanins in tomato skin extends shelf life. New Phytol. 2013, 200, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Butelli, E.; De Stefano, R.; Schoonbeek, H.-j.; Magusin, A.; Pagliarani, C.; Wellner, N.; Hill, L.; Orzaez, D.; Granell, A. Anthocyanins double the shelf life of tomatoes by delaying overripening and reducing susceptibility to gray mold. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, D.-W.; Jin, J.-H.; Yin, Y.-X.; Zhang, H.-X.; Chai, W.-G.; Gong, Z.-H. VIGS approach reveals the modulation of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes by CaMYB in chili pepper leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Kim, Y.; Huang, L.; Xiao, C. Resistance to thiabendazole and baseline sensitivity to fludioxonil and pyrimethanil in Botrytis cinerea populations from apple and pear in Washington State. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2010, 56, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, S.; Veloukas, T.; Leroch, M.; Menexes, G.; Hahn, M.; Karaoglanidis, G. Population structure, fungicide resistance profile, and sdhB mutation frequency of Botrytis cinerea from strawberry and greenhouse-grown tomato in Greece. Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lightbourn, G.J.; Griesbach, R.J.; Novotny, J.A.; Clevidence, B.A.; Rao, D.D.; Stommel, J.R. Effects of anthocyanin and carotenoid combinations on foliage and immature fruit color of Capsicum annuum L. J. Hered. 2008, 99, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tikunov, Y.; Schouten, R.E.; Marcelis, L.F.; Visser, R.G.; Bovy, A. Anthocyanin biosynthesis and degradation mechanisms in Solanaceous vegetables: A review. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, J.; Ma, R.; Miao, Y.; Chen, W.; Zheng, J.; Pang, X.; Wan, H. Pigment biosynthesis and molecular genetics of fruit color in pepper. Plants 2023, 12, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oney-Montalvo, J.E.; Avilés-Betanzos, K.A.; Ramírez-Rivera, E.d.J.; Ramírez-Sucre, M.O.; Rodríguez-Buenfil, I.M. Polyphenols content in Capsicum chinense fruits at different harvest times and their correlation with the antioxidant activity. Plants 2020, 9, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, R.; Aires, A.; Rodrigues, N.; Peres, A.M.; Pereira, J.A. Phenolics and antioxidant activity of green and red sweet peppers from organic and conventional agriculture: A comparative study. Agriculture 2020, 10, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, L.; Cotoras, M.; Vivanco, M.; Matsuhiro, B.; Torres, S.; Aguirre, M. Evaluation of antifungal properties against the phytopathogenic fungus botrytis cinereaof anthocyanin rich-extracts obtained from grape pomaces. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2013, 58, 1725–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnow, C.S.; Cohen, F.; Sadhasivam, S.; Raphael, G.; Sionov, E.; Ziv, C. Sweet Pepper cv. Lai Lai Ripeness Stage Influences Susceptibility to Mycotoxinogenic Alternaria alternata Causing Black Mold. Plant Pathol. J. 2025, 41, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.J.; van den Abeele, C.; Ortega-Salazar, I.; Papin, V.; Adaskaveg, J.A.; Wang, D.; Casteel, C.L.; Seymour, G.B.; Blanco-Ulate, B. Host susceptibility factors render ripe tomato fruit vulnerable to fungal disease despite active immune responses. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 2696–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, P.; Powell, A.L.; Orlando, R.; Bergmann, C.; Gutierrez-Sanchez, G. Proteomic analysis of ripening tomato fruit infected by Botrytis cinerea. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 2178–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.J.; Adaskaveg, J.A.; Mesquida-Pesci, S.D.; Ortega-Salazar, I.B.; Pattathil, S.; Zhang, L.; Hahn, M.G.; Van Kan, J.A.; Cantu, D.; Powell, A.L. Botrytis cinerea infection accelerates ripening and cell wall disassembly to promote disease in tomato fruit. Plant Physiol. 2023, 191, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrasch, S.; Silva, C.J.; Mesquida-Pesci, S.D.; Gallegos, K.; Van Den Abeele, C.; Papin, V.; Fernandez-Acero, F.J.; Knapp, S.J.; Blanco-Ulate, B. Infection strategies deployed by Botrytis cinerea, Fusarium acuminatum, and Rhizopus stolonifer as a function of tomato fruit ripening stage. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.D.; McDonald, G.; Scott, E.S.; Able, A.J. Infection pathway of Botrytis cinerea in capsicum fruit (Capsicum annuum L.). Australas. Plant Pathol. 2013, 42, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamara, A.; El-Argawy, E.; Korany, A.E.; Amer, G. Potential of certain cultivars and resistance inducers to control gray mould (Botrytis cinerea) of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 10, 1926–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilha, H.K.M.; Madruga, N.d.A.; Aranha, B.C.; Hoffmann, J.F.; Crizel, R.L.; Barbieri, R.L.; Chaves, F.C. Defense responses of Capsicum spp. genotypes to post-harvest Colletotrichum sp. inoculation. Phytoparasitica 2019, 47, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trávníčková, M.; Chrpová, J.; Palicová, J.; Kozová, J.; Martinek, P.; Hnilička, F. Association between Fusarium head blight resistance and grain colour in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Cereal Res. Commun. 2024, 52, 1599–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzi, M.; Blandino, M.; Dall’Asta, C.; Martinek, P.; Bruni, R.; Righetti, L. Anthocyanin content and Fusarium mycotoxins in pigmented wheat (Triticum aestivum L. spp. aestivum): An open field evaluation. Plants 2023, 12, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felici, L.; Atanasova, V.; Ponts, N.; Ducos, C.; Francesconi, S.; Sestili, F.; Richard-Forget, F.; Balestra, G.M. Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside and other anthocyanins affect enniatins production in Fusarium avenaceum. Fungal Biol. 2025, 129, 101640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; He, L.; Feng, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Qiu, Q.; Liu, J.; Han, H.; Huang, X. Metabolome and Transcriptome Analyses of the Molecular Mechanism Underlying Light-Induced Anthocyanin Accumulation in Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Peel. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cota, I.; Troncoso-Rojas, R.; Sotelo-Mundo, R.; Sánchez-Estrada, A.; Tiznado-Hernández, M. Chitinase and β-1, 3-glucanase enzymatic activities in response to infection by Alternaria alternata evaluated in two stages of development in different tomato fruit varieties. Sci. Hortic. 2007, 112, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, A.; Ferreres, F.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Gil, M.I. Characterization and quantitation of antioxidant constituents of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 3861–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garra, A.; Alkalai-Tuvia, S.; Telerman, A.; Paran, I.; Fallik, E.; Elmann, A. Anti-proliferative activities, phytochemical levels and fruit quality of pepper (Capsicum spp.) following prolonged storage. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 3574–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peić Tukuljac, M.; Danojević, D.; Medić-Pap, S.; Gvozdanović-Varga, J.; Prvulović, D. Antioxidant response of sweet pepper fruits infected with Alternaria alternata. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2023, 88, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.; Zehra, A.; Swapnil, P.; Dubey, M.K.; Patel, C.B.; Upadhyay, R. Effect on lycopene, β-carotene, ascorbic acid and phenolic content in tomato fruits infected by Alternaria alternata and its toxins (TeA, AOH and AME). Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2017, 50, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzakis, N. Physiological and proteomic approaches to address the active role of Botrytis cinerea inoculation in tomato postharvest ripening. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.T.; Wright, S.A.; Falk, A.B.; Vanwalleghem, T.; Van Hemelrijck, W.; Hertog, M.L.; Keulemans, J.; Davey, M.W. Botrytis cinerea differentially induces postharvest antioxidant responses in ‘Braeburn’and ‘Golden Delicious’ apple fruit. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 5662–5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, N.A.; Shafiq, F.; Ashraf, M. Ascorbic acid-a potential oxidant scavenger and its role in plant development and abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echenique-Martínez, A.A.; Ramos-Parra, P.A.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, D.G.; Troncoso-Rojas, R.; Islas-Rubio, A.R.; Montoya-Ballesteros, L.d.C.; Hernández-Brenes, C. Botrytis cinerea induced phytonutrient degradation of strawberry puree: Effects of combined preservation approaches with high hydrostatic pressure and synthetic or natural antifungal additives. CyTA-J. Food 2023, 21, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muckenschnabel, I.; Goodman, B.; Williamson, B.; Lyon, G.; Deighton, N. Infection of leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana by Botrytis cinerea: Changes in ascorbic acid, free radicals and lipid peroxidation products. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimdars, S.; Hitschler, J.; Schieber, A.; Weber, F. Oxidation of wine polyphenols by secretomes of wild Botrytis cinerea strains from white and red grape varieties and determination of their specific laccase activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 10582–10590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Ulate, B.; Amrine, K.C.; Collins, T.S.; Rivero, R.M.; Vicente, A.R.; Morales-Cruz, A.; Doyle, C.L.; Ye, Z.; Allen, G.; Heymann, H. Developmental and metabolic plasticity of white-skinned grape berries in response to Botrytis cinerea during noble rot. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 2422–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ky, I.; Lorrain, B.; Jourdes, M.; Pasquier, G.; Fermaud, M.; Gény, L.; Rey, P.; Doneche, B.; TEISSEDRE, P.L. Assessment of grey mould (Botrytis cinerea) impact on phenolic and sensory quality of Bordeaux grapes, musts and wines for two consecutive vintages. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2012, 18, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, P.; Just-Borras, A.; Gombau, J.; Canals, J.M.; Zamora, F. Effects of laccase from Botrytis cinerea on the oxidative degradation of anthocyanins. Oeno One 2023, 57, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Arias, S.; Guerrero Álvarez, G.E. Effect of Botrytis cinerea inoculation on the antioxidant capacity and total phenolic content in Rubus glaucus benth. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2021, 54, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Tao, S.; Dubé, C.; Tury, E.; Hao, Y.J.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, M.; Wu, W.; Khanizadeh, S. Postharvest changes in the total phenolic content, antioxidant capacity and L-phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity of strawberries inoculated with Botrytis cinerea. J. Plant Stud. 2012, 1, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ji, D.; Cui, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; Xu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tian, S. p-Coumaric acid induces antioxidant capacity and defense responses of sweet cherry fruit to fungal pathogens. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 169, 111297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazener, J. Accumulation of phenolic compounds in cells and formation of lignin-like polymers in cell walls of young tomato fruits after inoculation with Botrytis cinerea. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 1982, 20, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, G.; Regente, M.; Jacobi, S.; Del Rio, M.; Pinedo, M.; de la Canal, L. Chlorogenic acid is a fungicide active against phytopathogenic fungi. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2017, 140, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, W.S.; Lee, D.G. Antifungal action of chlorogenic acid against pathogenic fungi, mediated by membrane disruption. Pure Appl. Chem. 2010, 82, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gresa, M.P.; Torres, C.; Campos, L.; Lisón, P.; Rodrigo, I.; Bellés, J.M.; Conejero, V. Identification of defence metabolites in tomato plants infected by the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2011, 74, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijada-Morin, N.; Garcia, F.; Lambert, K.; Walker, A.S.; Tiers, L.; Viaud, M.; Sauvage, F.X.; Hirtz, C.; Saucier, C. Strain effect on extracellular laccase activities from Botrytis cinerea. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2018, 24, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinova, J.; Radova, S. Effects of rutin on the growth of Botrytis cinerea, Alternaria alternata and Fusarium solani. Acta Phytopathol. Entomol. Hung. 2009, 44, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).