Abstract

High temperatures induce oxidative stress and the production of a large amount of malondialdehyde (MDA) in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas, and they can even lead to mass mortality. Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) degrades MDA and is attracting increasing attention for its role in enhancing antioxidant defense capacity. This study identified 14 ALDH family members in the oyster genome. Among them, CgALDH6A1 harbored a conserved ALDH_F6_MMSDH domain (known to catalyze the oxidation of aliphatic and aromatic aldehydes) and was likely involved in the high-temperature stress response through the detoxification of accumulated toxic aldehydes. In the gills, CgALDH6A1 had significantly higher mRNA expression than other tissues, with a significant increase at 12 h under 28 °C high-temperature stress. During the outdoor aquaculture period, the mRNA transcripts of CgALDH6A1 in the gills exhibited a significant increase from June to October. After the expression of CgALDH6A1 was inhibited by RNAi, the MDA content in the gills increased significantly (1.31-fold, p < 0.01), while the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) (0.93-fold, p < 0.05) and catalase (CAT) (0.45-fold, p < 0.001) and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) (0.54-fold, p < 0.01) decreased significantly under high-temperature stress. Meanwhile, the gill tissue was observed to be disorganized with obvious filament swelling. After the oysters were treated with CgALDH6A1 agonist (Alda-1), the MDA content (0.59-fold, p < 0.001) in the gills decreased significantly, while the activities of SOD (1.33-fold, p < 0.001), CAT (1.81-fold, p < 0.001), and T-AOC (1.79-fold, p < 0.01) all increased significantly 48 h after high-temperature stress. However, no obvious morphological changes were observed in the gills. These results demonstrate that CgALDH6A1 plays a key role in regulating the oxidative stress response by degrading MDA under high-temperature stress and plays a cooperative role with the antioxidant system in alleviating oxidative stress under high-temperature stress.

1. Introduction

The aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) enzymes constitute a superfamily of enzymes that catalyze the oxidation of diverse aldehydes into their respective carboxylic acid products. ALDH catalysts facilitate the irreversible oxidation of internally produced aldehydes, thereby mitigating aldehyde-induced cytotoxicity [1,2,3,4]. They are integral to antioxidant defense mechanisms [5,6,7], notably because of oxidizing lipid peroxidation byproducts [8], mitigating aldehyde-mediated oxidative damage. Studies have shown that high-temperature stress significantly increases malondialdehyde (MDA) production [9,10,11] and triggers oxidative damage in marine organisms [12,13,14]. The investigation of ALDH in the oxidative stress response of marine organisms under high-temperature stress may provide fundamental insights into the high-temperature adaptation mechanisms of marine organisms.

The composition and structure of ALDH have undergone significant changes over the course of evolution. Nevertheless, ALDHs generally possess a conserved structural fold and employ a shared catalytic mechanism—one that incorporates a catalytic cysteine residue and a cofactor (e.g., NAD+ or NADP+). The traditional ALDH fold consists of four structural components: a conserved foundational structural unit, a Rossmann binding domain, a catalytic domain, and an extra oligomerization domain. The majority of ALDHs adopt a unique twisted dimerization pattern driven by the oligomerization domain; these dimers further assemble regularly to form higher-order complexes, typically tetramers or hexamers. ALDH6A1 functions as a mitochondrial tetrameric protein and is further identified as methylmalonate semialdehyde (MMS) dehydrogenase, with the alternative name MMSDH [15]. ALDH6A1 contains a unique conserved ALDH_F6_MMSDH domain. Being the only identified Coenzyme A (CoA)-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase in humans, it participates in the catabolism of valine and pyrimidines. By metabolizing malonate semialdehyde, ALDH6A1 participates in the process of converting MDA into acetyl-CoA [16]. Stress conditions elevate levels of MDA, a final product of lipid peroxidation [2,3]. MDA is initially oxidized into acetaldehyde by ALDH and then converted into acetate and finally carbon dioxide and water [17]. Therefore, ALDH plays a critical role in alleviating oxidative damage under environmental stress [18,19]. The ALDH family is widely distributed across organisms and classified into 24 different families (ALDH1~ALDH24) [20], 7 of which are plant-specific: ALDH11, 12, 19, 21, 22, 23, and 24 [21]. Up to now, 19 ALDH genes have been characterized in humans (Homo sapiens) [15], and they exert significant effects on biosynthesis and antioxidant defense pathways [22]. Among invertebrates, 11 ALDHs have been identified in the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster [23,24]. To date, research on ALDH in shellfish remains relatively limited, with 16 ALDH genes having been recognized in the razor clam Sinonovacula constricta [25].

Excessive accumulation of aldehyde compounds occurs under high-temperature stress [26,27], which can interact with proteins and nucleic acids, damaging their functions and thereby causing cell death [28]. ALDHs respond to high-temperature stress by modulating their mRNA expression levels and alleviating cell damage induced by aldehydes, thereby alleviating oxidative stress. The transcription levels of the genes ALDH3I1 and ALDH7B4 were significantly increased in mouse-ear cress Arabidopsis thaliana after high-temperature stress [29]. An increase in total ALDH activity was observed in the Antarctic microalga Chlorella vulgaris under high-temperature stress, indicating that ALDH5 and ALDH6 isozymes play important roles in heat tolerance [30]. Studies on the reaction of ALDH to high-temperature stress in invertebrates remain limited. Research has shown that the expression of ALDH is significantly upregulated in the Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei under high-temperature stress, indicating that ALDH has a significant function under high-temperature stress [31]. For instance, ALDH2 knockdown resulted in the accumulation of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and MDA under high-temperature stress, while Alda-1 (a known activator of ALDH2) alleviated the activation of inflammatory pathways that was induced by high-temperature stress in mice (Mus musculus) [32]. The information above remains largely unexplored in regard to invertebrates. Furthermore, the mechanism by which ALDH alleviates oxidative stress in oysters through the clearance of MDA remains poorly understood.

As a commercial bivalve, the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas is a leading commercial bivalve globally, being cultivated in the highest yields in the world [33,34,35]. Recent research has reported frequent summer mortality events in oyster aquaculture [36,37,38], with elevated temperatures identified as the critical contributing factor [39,40]. High-temperature stress leads to the accumulation of MDA in oysters, thereby triggering oxidative damage and even death [10]. Current research on MDA clearance in oysters primarily focuses on traditional antioxidant systems. ALDH has been demonstrated to play a crucial role in the oxidative stress caused by high temperature in animals. This study investigates the gene structure, phylogenetic relationships, and function of CgALDH in response to high-temperature stress, aiming to (1) analyze the evolutionary and molecular characteristics of ALDH in oysters, (2) determine the expression patterns of ALDH under high-temperature stress, and (3) clarify the regulatory function of ALDH in antioxidant defense mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animal

Adult oysters, with an average shell length of 120 ± 20 mm, were collected from a local farm (seawater temperature 18.1 °C) in Dalian, China, in October 2024. Prior to the experiment, a narrow notch near the adductor muscle was cut to facilitate subsequent injection, and the oysters were acclimated in aerated seawater at 15 °C at a salinity of 29–31 for one week. During acclimation, they were fed algae powder once daily, and 50% of the seawater was replaced every two days. All high-temperature-stress treatments in the experiment were conducted by directly exposing oysters to the designated temperature conditions. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Dalian Ocean University (Approval Number: SHOU-23-014), with approval granted on 15 November 2024.

2.2. Bioinformatics Analysis and Identification of CgALDHs

The ALDH sequence data from model organisms (Table S1) were employed as queries to retrieve homologous sequences in the oyster genome databases (GenBank Bioproject IDs: PRJNA276446 and PRJNA598006) via tblastn analysis. For domain analysis, two approaches were employed: SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/ accessed on 20 March 2025) [41] was used for initial domain prediction, and conserved domains were further identified via NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov accessed on 20 March 2025); meanwhile, conserved motifs were recognized using MEME (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme accessed on 20 March 2025) [42]. MEGA-X software (version number: v12.0.14) was used for phylogenetic tree construction via the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method with 1000 bootstrap replicates [43]. Final tree visualization was refined using ChiPlot (https://www.chiplot.online accessed on 21 March 2025) [44]. For the identification of the CgALDH6A1 sequence, Primer 5 software was used to design the cloning primers CgALDH6A1-F and CgALDH6A1-R for the ORF frame (Table 1). The Takara LA Taq enzyme system amplified the ORF sequence of CgALDH6A1 via PCR. After the PCR product was purified via gel electrophoresis, it was inserted into the pMD19-T cloning vector (Takara, Shiga, Japan) and transformed into competent Escherichia coli Trans5α cells for sequencing verification.

Table 1.

Information on experimental primers.

2.3. Transcriptomic Sequencing and mRNA Expression Under Different Conditions

Twenty-seven oysters were randomly selected for high-temperature stress treatment. Nine oysters served as the untreated control group (AC). Gill tissues were collected from nine oysters at 12 h after subjection to 28 °C high-temperature stress (AH group), and gill tissues were collected from the other nine oysters at 12 h under 35 °C high-temperature stress (AHH group). Total RNA was extracted from all samples for transcriptomic analysis. The cDNA libraries were constructed and sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) to generate paired-end reads. The clean reads were obtained by removing the reads with adapters, the reads with >10% unknown bases, and low-quality reads (reads with >50% of the total length with Qphred ≤ 20). Filtered reads were mapped to the genome using Hisat2 v2.0.5. Transcriptome data were used for the analysis of mRNA expression under high-temperature stress via TBtools (version number: v2.310) [45].

Six ALDHs genes were identified to respond to high temperatures based on transcriptomic data. To investigate the tissue-specific expression patterns of ALDHs in oysters under high-temperature stress, hepatopancreas, hemolymph, gills, mantle, labial palp, gonads, and adductor muscle were collected 24 h after the oysters underwent high-temperature stress at 28 °C; here, 28 °C was used for high-temperature exposure because it is the highest temperature recorded in the North Yellow Sea [46]. The tissues from three oysters were pooled together as one sample, and there were three samples for each tissue. Total RNA was isolated from all samples to determine the mRNA expression levels of CgALDH1β1, CgALDH1β2, CgALDH2α, CgALDH6A1, CgALDH7A1, and CgALDH8A1. Tissue-specific expression analysis revealed that three ALDH genes exhibited the highest expression levels in the gills. Given that gill tissue is the primary tissue involved in the response to high-temperature stress, these three genes were selected for time-course expression analysis. To stimulate the long-term high-temperature stress that oysters experience in summer, 72 oysters were exposed to high-temperature stress at 28 °C, with 9 oysters randomly collected at 0 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 7 d, 14 d and 21 d after being subjected to high-temperature stress. Total RNA was isolated from all samples to determine the mRNA expression levels of CgALDHs.

Given that CgALDH6A1 responds to high temperatures, an outdoor aquaculture experiment was conducted to analyze its expression pattern. The aquaculture investigation in this study was conducted during the period from March to October 2023. During the outdoor aquaculture period (March–October), the seawater temperatures were 3.6 °C, 8.4 °C, 13.2 °C, 16.8 °C, 22.4 °C, 25.5 °C, 24.3 °C, and 17.6 °C, and the salinity was 30.0, 29.6, 29.6, 29.2, 30.6, 27.6, 29.0, and 30.1, respectively. Nine oysters (two years old) were collected monthly for gill sampling. Total RNA was isolated from samples to determine the mRNA expression levels of CgALDH6A1.

2.4. RNA Interference (RNAi) and Alda-1 Treatment

A total of 54 oysters were randomly divided into six groups: the Blank group (oysters without any treatment), the negative control (NC) group (oysters that received an injection with NC dsRNA), the CgALDH6A1-RNAi group (oysters injected with CgALDH6A1 dsRNA), the DMSO group (oysters injected with DMSO), and the Alda-1 group (oysters injected with Alda-1). To interfere with the expression of CgALDH6A1, specific double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) targeting this gene was designed and synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The oysters in the NC group, CgALDH6A1-RNAi group, DMSO group, and Alda-1 group were injected with the following reagents (100 μL each): 20 μmol negative control (NC) dsRNA, 20 μmol CgALDH6A1 dsRNA (Table 1), 200 μmol DMSO, and 200 μmol Alda-1 (MCE, Shanghai, China) [47]. Untreated oysters were employed as the Blank group. At 12 h after the injection, the oysters were exposed to 28 °C for 48 h. The gills were collected to analyze the mRNA expression level of CgALDH6A1 and the measurement of the parameters of oxidative response (the content of MDA and the activities of SOD, CAT, and T-AOC).

2.5. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from the gills with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) per the manufacture’s protocol. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the SevenCleverTM First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (with dsDNase) (Seven, Beijing, China). The cDNA mixture was diluted 1:20 (cDNA:ddH2O) for use in RT-qPCR analysis.

2.6. RT-qPCR Analysis for mRNA Expression

To measure the mRNA expression levels of target CgALDH genes (CgALDH1β1, CgALDH1β2, CgALDH2α, CgALDH6A1, CgALDH7A1, and CgALDH8A1), RT-qPCR was conducted with corresponding primers (Table 1). RT-qPCR was performed with the SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM Kit (RR420, Takara, Japan) on an ABI 7500 Real-Time Detection System (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The fragment of elongation factor (CgEF, NM_001305313) was amplified with the primers CgEF-F and CgEF-R and used as internal reference. The 2−ΔΔCT method was applied to calculate the mRNA expression level [48].

2.7. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress Response

The enzymatic antioxidants, total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), and content of MDA in the tissues from the oysters in the blank, NC, CgALDH6A1-RNAi, DMSO, and Alda-1 groups were analyzed to assess the oxidative stress level following high-temperature stress and the responses to dsRNA (CgALDH6A1-RNAi) and Alda-1 treatments. The activities of catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD), total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), malondialdehyde (MDA) content, and total protein content were quantified using the respective assay kits (A007-1-1 for CAT, A001-3-2 for SOD, A015-1-2 for T-AOC, A003-1-2 for MDA, and A045-2-2 for total protein) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China).

2.8. Histopathological Observation of Tissues

Gill tissues from the blank, NC, CgALDH6A1-RNAi, DMSO, and Alda-1 groups were obtained for histopathological observation. Each tissue sample was cut into small pieces, about 3 mm square, and then immersed in Bouin’s solution to fix them for 24 h; they were then rinsed with 70% ethanol to remove fixative. Subsequently, the samples underwent sequential dehydration, wax immersion, and paraffin embedding using a paraffin-embedding machine to prepare paraffin sections, which were then dewaxed, stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E), re-dehydrated, and mounted with neutral balsam. Finally, they were dehydrated and sealed with neutral gum sealing and then subjected to microscopy, image collation, and analysis.

2.9. Data Analysis

Experimental data are presented as means ± standard deviations (n = 3) and were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparison tests using IBM SPSS 24.0 [49], with * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. The ALDH Gene Family in Oysters

A total of 14 ALDH homologues were identified in the genome pertaining to the oysters (Table 2). The ALDH18 subfamily was not detected in a substantially different intensity relative to humans, fruit flies, and razor clams. The homologues’ CDS lengths ranged from 1449 to 2775 bp, encoding 482 to 924 amino acids, with a relative molecular mass ranging from 91.23 to 102.47 kD and an isoelectric point ranging from 5.6 to 8.5.

Table 2.

The information on the CgALDH gene family.

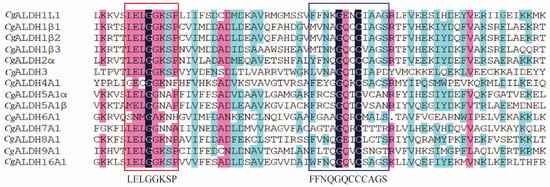

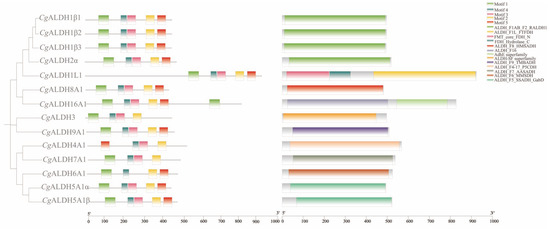

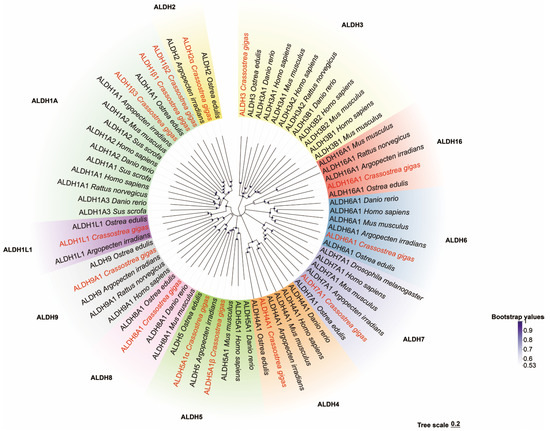

Multiple-sequence alignment revealed the presence of both glutamate active sites and cysteine active sites in all the CgALDH genes (Figure 1). Five motifs were identified from these CgALDHs using MEME online (https://meme-suite.org/meme/ accessed on 21 March 2025), and each ALDH protein contained three to five motifs (Figure 2). Structural domain prediction results revealed that 14 ALDH genes contain at least one complete ALDH domain, and genes from the same subfamily share similar structural characteristics. Among them, the CgALDH1, CgALDH2, and CgALDH5 subfamilies encompassed the ALDH_F1AB_F2_RALDH1 domain, and CgALDH6A1 possessed the ALDH_F6_MMSDH domain. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using 74 molluscan ALDH proteins, and the ALDHs from the same subfamily were clustered together (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of CgALDHs. Black shading indicates identical residues, pink shading indicates similar residues that are more than 80% similar, and blue shading indicates similar residues that are more than 50% similar. The red boxes indicate the conserved glutamic active sites, and the blue boxes indicate the conserved glutamic cysteine active sites.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree, conserved motifs, and conserved domain of CgALDH family genes.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of ALDH family genes.

The phylogenetic tree shows that these genes have aggregated into two distinct evolutionary branches. CgALDH3 was found to be associated with a single cluster, while CgALDH1, CgALDH2, CgALDH4, CgALDH5, CgALDH6, CgALDH7, CgALDH8, CgALDH9, and CgALDH16 formed a distinct evolutionary branch. Within this branch, the families of both CgALDH1 and CgALDH2, as well as CgALDH8 and CgALDH9, showed a close phylogenetic relationship, while the CgALDH3 subfamily formed a cluster distant from the other gene subfamilies. All CgALDH genes clustered closely with similar genes from other known species, with a primary alignment with the homologous genes from the European flat oyster, Ostrea edulis.

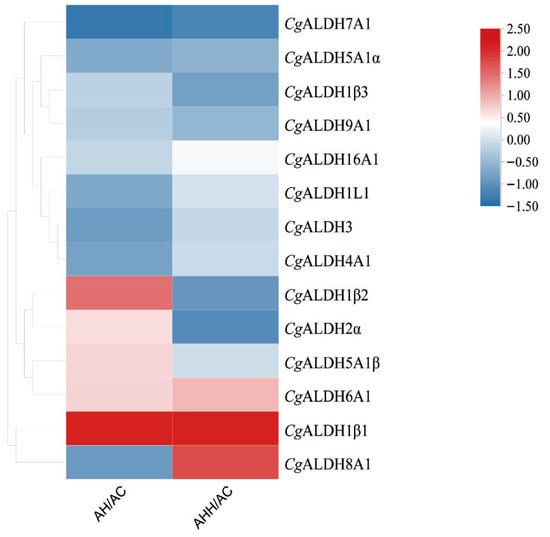

3.2. Transcriptome Heatmap Analysis and the Expression Profiles of CgALDHs in Tissues and Under High-Temperature Stress

Heat map analysis was conducted on the high-temperature stress groups and control group using the transcriptomic FPKM data (Figure 4). Following exposure to high-temperature stress at 28 °C, the expression levels of CgALDH1β1, CgALDH1β2, CgALDH2α, and CgALDH6A1 in the gills were 0.62-fold, 0.46-fold, 0.25-fold, and 0.27-fold higher than those in the AC group, respectively (p < 0.05). Conversely, the expression levels of CgALDH7A1 and CgALDH8A1 in the gills were significantly down-regulated by 24% and 12% compared with those in the AC group, respectively (p < 0.05). Additionally, 12 h after high-temperature stress at 35 °C, the expression levels of CgALDH1β1, CgALDH6A1, and CgALDH8A1 in the gills were 0.52-fold, 0.21-fold, and 0.43-fold higher than those in the AC group, respectively (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, the expression levels of CgALDH1β2, CgALDH2α, and CgALDH7A1 in the gills were significantly down-regulated by 25%, 29%, and 31% compared with those in the AC group, respectively (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Heat map of mRNA expression of CgALDHs under high-temperature stress. Each cell in the heat map corresponds to the ratio of FPKM between the high-temperature stress sample and blank sample. The intensity of the color from red to blue indicates the magnitude of differential expression. The AH group refers to oysters subjected to 28 °C high-temperature stress for 12 h; the AHH group refers to those exposed to 35 °C high-temperature stress for 12 h; and the AC group is the untreated control.

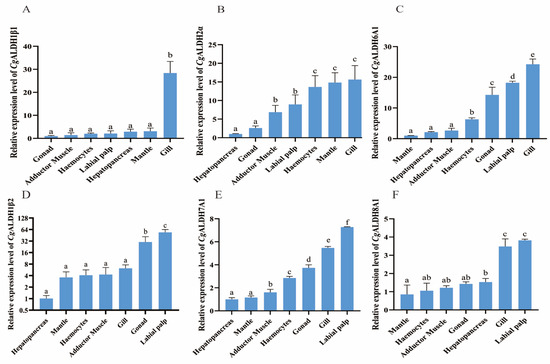

The mRNA expression levels of six CgALDHs, including CgALDH1β1, CgALDH1β2, CgALDH2α, CgALDH6A1, CgALDH7A1, and CgALDH8A1, in several tissues were analyzed using RT-qPCR. The six CgALDH genes were found to be ubiquitously expressed in all the examined tissues with different expression profiles. CgALDH1β1 showed the highest expression levels in the gills and the lowest in the gonads (Figure 5A). The expression level of CgALDH1β1 in the gills was 26.74-fold higher than that in the gonad (p < 0.001), with no significant differences observed in the mantle, hepatopancreas, labial palp, or hemocytes. CgALDH1β2 exhibited the highest expression level in the labial palp and the lowest in the hepatopancreas (Figure 5B). The expression levels of CgALDH1β2 in the labial palp and gonad were 52.56-fold (p < 0.001) and 29.00-fold (p < 0.001) higher than that in the hepatopancreas, respectively, with no significant difference in the gills, adductor muscle, hemocytes, or mantle. CgALDH2α showed the highest expression level in the gills and the lowest in the hepatopancreas (Figure 5C). The expression level of CgALDH2α in the gills, mantle, hemocytes, labial palp, and adductor muscle was 14.59-fold (p < 0.001), 13.78-fold (p < 0.001), 12.59-fold (p < 0.001), 7.93-fold (p < 0.05), and 5.86-fold (p < 0.05) higher than that in the hepatopancreas, respectively, with no significant difference in the gonad. CgALDH6A1 displayed the highest expression level in the gills and the lowest in the mantle (Figure 5D). The expression level of CgALDH6A1 in the gills, labial palp, gonad, and hemocytes was 23.24-fold (p < 0.001), 17.22-fold (p < 0.001), 13.29-fold (p < 0.001), and 5.30-fold (p < 0.001) higher than that in the mantle, respectively, with no significant difference in the hepatopancreas or adductor muscle. CgALDH7A1 showed the highest expression level in the labial palp and the lowest in the hepatopancreas (Figure 5E). The expression level of CgALDH7A1 in the labial palp, gills, gonads, hemocytes, and adductor muscle was 6.24-fold (p < 0.001), 4.44-fold (p < 0.001), 2.71-fold (p < 0.001), 1.84-fold (p < 0.001), and 0.90-fold (p < 0.05) higher than that in the hepatopancreas, respectively, with no significant differences in the mantle. CgALDH8A1 exhibited the highest expression level in the labial palp and the lowest in the mantle (Figure 5F). The expression levels of CgALDH8A1 in the labial palp, gills, hepatopancreas, gonads, adductor muscle, and hemocytes were 6.62-fold (p < 0.001), 5.95-fold (p < 0.001), 2.05-fold (p < 0.001), 1.86-fold (p < 0.001), 1.43-fold (p < 0.05), and 1.11-fold (p < 0.05) higher than those in the mantle, respectively.

Figure 5.

The mRNA expression patterns of CgALDHs in different tissues under 28 °C high-temperature stress for 24 h. (A): CgALDH1β1; (B): CgALDH2α; (C): CgALDH6A1; (D): CgALDH1β2; (E): CgALDH7A1; (F): CgALDH8A1. Vertical bars represent the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). Significant differences between groups are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05).

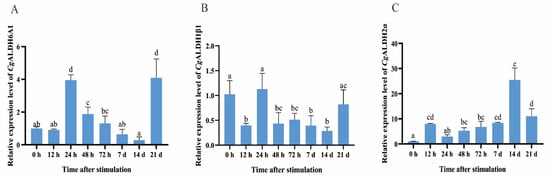

The expression levels of CgALDH1β1, CgALDH2α, and CgALDH6A1 in the gills of oysters at different time points after undergoing high-temperature stress at 28 °C were further examined via RT-qPCR. After the oysters were subjected to high-temperature stress at 28 °C, the expression level of CgALDH1β1 decreased significantly, by 50–72%, at 12 h, 48 h, 72 h, 7 d, and 14 d, with respective reductions of 61% (p < 0.01), 57% (p < 0.01), 50% (p < 0.05), 61% (p < 0.01), and 72% (p < 0.001) compared with that at 0 h. In contrast, the expression of CgALDH2α increased significantly at 12 h, 48 h, 72 h, 7 d, 14 d, and 21 d, being 6.97-fold (p < 0.01), 4.27-fold (p < 0.05), 5.76-fold (p < 0.01), 7.38-fold (p < 0.001), 23.40-fold (p < 0.001), and 10.05-fold (p < 0.001) higher than that at 0 h, respectively. The expression of CgALDH6A1 exhibited a pattern of first increasing and then decreasing. At 24 h and 21 d after exposure to high-temperature stress at 28 °C, its expression increased significantly, being 2.94-fold (p < 0.001) and 3.08-fold (p < 0.001) higher than that at 0 h, respectively (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The mRNA expression levels of six CgALDHs in gills after exposure to 28 °C. (A): CgALDH6A1; (B): CgALDH1β1; (C): CgALDH2α. Vertical bars represent the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). Significant differences between groups are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05).

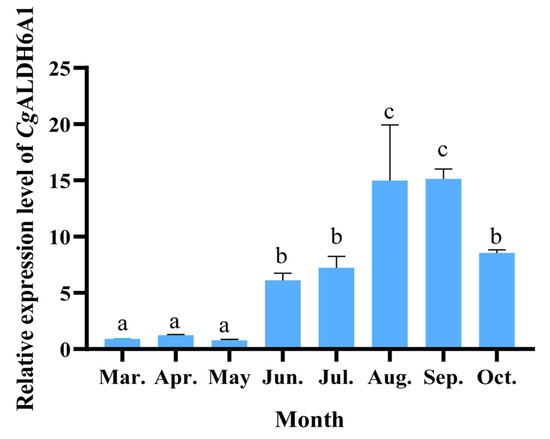

3.3. The mRNA Expression Level of CgALDH6A1 During Outdoor Aquaculture

As the expression of CgALDH6A1 in the gills increased significantly after exposure to high-temperature stress, its alteration in the gills of oysters during an outdoor aquaculture period was examined to further investigate the involvement of CgALDH6A1 in the response to high-temperature stress in aquaculture. The expression level of CgALDH6A1 in June, July, August, September, and October was significantly higher than that in March, being 5.78-fold (p < 0.01), 7.03-fold (p < 0.001), 15.67-fold (p < 0.001), 15.82-fold (p < 0.001), and 8.50-fold (p < 0.001) greater, respectively (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The mRNA expression levels of CgALDH6A1 in gill tissue of oysters during the aquaculture period. Vertical bars represent the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). Significant differences between groups are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05).

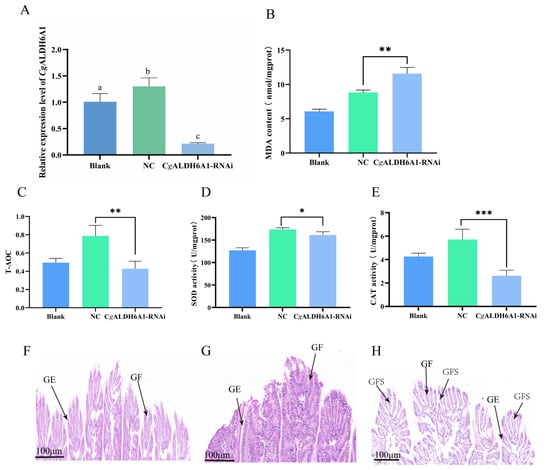

3.4. The Changes in Oxidative Stress Response and Histopathological Changes in CgALDH6A1-RNAi in Oysters

After the expression of CgALDH6A1 was suppressed by RNAi, the changes in oxidative stress response including with respect to MDA content, T-AOC, and the activities of CAT and SOD in the gills were examined to further confirm the involvement of CgALDH6A1 in the high-temperature stress response. The mRNA expression of CgALDH6A1 in the gills decreased significantly 48 h after the injection of targeted dsRNA, with a fold change equal to 0.16 (p < 0.001) of that in the NC group (Figure 8), indicating that the expression of CgALDH6A1 was suppressed effectively. The MDA content in CgALDH6A1-RNAi oyster gills significantly increased (1.31-fold, p < 0.01) relative to that in the NC group, while T-AOC and the activities of SOD and CAT in the gills all decreased significantly, with 0.54-fold (p < 0.01), 0.93-fold (p < 0.05), and 0.45-fold (p < 0.001) reductions relative to the NC group, respectively (Figure 8B–E). Gill tissues from the oysters in the CgALDH6A1-RNAi group were collected and observed under a microscope after being stained with hematoxylin–eosin. The gill epithelium of the blank group exhibited an orderly arrangement in a single layer, with clearly visible nuclei that were round or oval, while the gill filaments of CgALDH6A1-RNAi individuals were disorganized, with obvious swelling (Figure 8F–H).

Figure 8.

The mRNA expression level of CgALDH6A1 and changes in oxidative stress indexes in gills of CgALDH6A1-RNAi oysters after being subjected to high-temperature stress. The blank group consisted of untreated oysters; the NC group included oysters that were injected with negative control (NC) dsRNA; and the oysters in CgALDH6A1-RNAi group were injected with CgALDH6A1 dsRNA. (A): CgALDH6A1 mRNA expression level. (B): MDA content. (C): T-AOC. (D): SOD activity. (E): CAT activity. (F): Blank group, (G): NC group, (H): CgALDH6A1 RNAi group; GE: gill epithelium, GF: gill filament, GFS: gill filament swelling. Significant differences between groups are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05). The significant difference between the control group and the experimental group is represented by asterisks (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001).

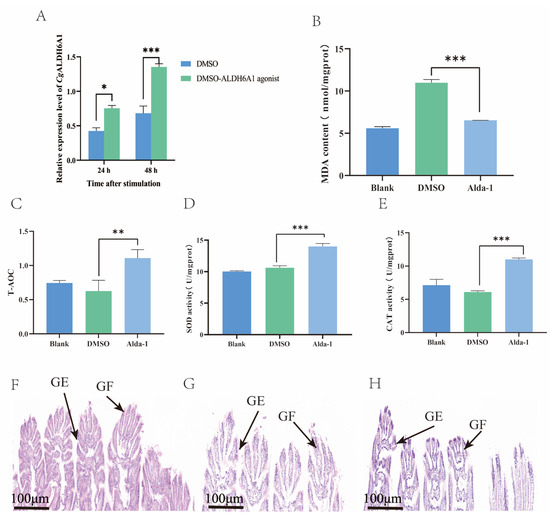

3.5. Changes in the Oxidative Stress Response After the Injection of Alda-1 In Vivo

After CgALDH6A1 expression was activated with Alda-1 injection, the changes in the oxidative stress response, including MDA content, T-AOC, and the activities of CAT and SOD, in the gills were examined to further confirm the involvement of CgALDH6A1 in the high-temperature stress response. The mRNA expression of CgALDH6A1 in the gills increased significantly 24 h and 48 h after the injection of Alda-1, being 1.78-fold (p < 0.05) and 1.98-fold (p < 0.001) of that in the DMSO group, respectively (Figure 9A), indicating that the expression CgALDH6A1 was activated effectively. The most significant change in the expression level of CgALDH6A1 was observed 48 h after agonist injection. Thus, the changes in oxidative stress indexes were explored. The Alda-1 group had a significantly reduced gill MDA content (0.59-fold of the DMSO group, p < 0.001), whereas its gill T-AOC (1.79-fold, p < 0.01), SOD activity (1.33-fold, p < 0.001), and CAT activity (1.81-fold, p < 0.001) were all significantly higher than those in the DMSO group (Figure 9B–E). Gill tissues of oysters in the Alda-1 group were collected, stained with hematoxylin–eosin (HE), and then observed under a microscope. The gill epithelium of the blank group exhibited an orderly arrangement in a single layer, with clearly visible nuclei that are round or oval, and the gills from the Alda-1 group showed no obvious morphological changes in comparison with the blank group (Figure 9F–H).

Figure 9.

The mRNA expression level of CgALDH6A1 and changes in oxidative stress indexes in gills after the injection of agonist in vivo after exposure to high-temperature stress. (A): CgALDH6A1 mRNA expression level. (B): MDA content. (C): T-AOC. (D): SOD activity. (E): CAT activity. (F): Blank group, (G): DMSO group, (H): Alda-1 group; GE: gill epithelium, GF: gill filament. Vertical bars represent the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences (*: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

Intertidal organisms, including oysters, have evolved highly conserved molecular regulatory strategies to cope with environmental stress [50]. ALDH plays an important role in the process by cooperating with the antioxidant system in alleviating oxidative stress under high-temperature stress. In this study, we found that CgALDH6A1-targeted MDA mediates the oxidative stress response of oysters, with the aim of elucidating its role in regulating antioxidant function under high-temperature stress.

A total of 14 ALDH family members were identified in the oyster genome, exceeding the 11 ALDH genes reported in fruit flies [19,20] but amounting to less than the 19 and 16 ALDHs identified in humans [51] and razor clams [21], respectively. This pattern suggests that the CgALDH family has undergone moderate gene expansion during invertebrate evolution. Results from structural-domain prediction indicated that ALDH genes within the same subfamily share similar structural characteristics. Among them, CgALDH6A1 contains the ALDH_F6_MMSDH domain and oxidizes various aliphatic and aromatic aldehydes [52]. ALDH6A1, also known as methylmalonate semialdehyde (MMS) dehydrogenase, is the only known human ALDH isoform that depends on coenzyme A (CoA) for its catalytic activity, as it metabolizes methylmalonate semialdehyde and converts lipid-peroxidation-derived aldehydes, such as MDA, into acetyl-CoA. The degradation of MDA by other ALDH isoforms proceeds through NAD(P)+-dependent oxidative reactions, ultimately leading to the decomposition of MDA into carbon dioxide and water. Phylogenetic analysis showed that the ALDH1 and ALDH2 subfamilies, as well as CgALDH8 and CgALDH9, cluster into the same phylogenetic branch, suggesting a close evolutionary relationship. The CgALDH genes primarily cluster with homologs from the European flat oyster, forming a sister clade with the bay scallop Argopecten irradians, indicating evolutionary conservation and potential functional significance of ALDH genes across bivalve lineages. Conservative site analysis showed that CgALDH proteins possess both a glutamate-active site (LELGGKSP) and a cysteine-active site (FFNQGQCCCAGS), which are essential for ALDH catalytic function [53]. These conserved sequences highlight the evolutionary stability and structural importance of ALDH catalytic domains across species.

As key aldehyde-detoxifying enzymes, ALDHs maintain cellular homeostasis and play essential roles in stress responses [54,55,56]. In this study, six CgALDH genes (CgALDH1β1, CgALDH1β2, CgALDH2α, CgALDH6A1, CgALDH7A1, and CgALDH8A1) were found to be involved in high-temperature stress based on transcriptomic data obtained under high-temperature stress. The expression of some CgALDHs was almost specific to a certain tissue (e.g., CgALDH1β1 in the gills), while others were expressed in all tissues, with only slight differences among tissues. Notably, the hepatopancreas, a detoxification tissue, showed high expression only for CgALDH8A1, warranting further investigation. It was found that CgALDH1β1, CgALDH2α, and CgALDH6A1 mRNA levels were highly expressed in the gills. Gill tissue is the main tissue responsible for triggering a response to high-temperature stress, and it achieves this response by synthesizing heat shock proteins, amplifying antioxidant capacity, and governing apoptosis [57]. Thus, the expression levels of the three CgALDHs after high-temperature stress were examined. In response to high-temperature stress, the expression of CgALDH6A1 and CgALDH2α in the gills significantly upregulated, and CgALDH6A1 was chosen for the further investigation. Monthly expression profiles of CgALDH6A1 during the outdoor aquaculture period revealed a significant increase around summer from June to October. Oysters exhibit antioxidant responses to thermal stress, and previous studies have reported increased ALDH activity under such conditions [31]. Similarly, high temperatures induce oxidative stress in shrimp, triggering increased ALDH expression to detoxify accumulated aldehydes. These results indicate that ALDH6A1 is responsive to high-temperature stress and plays a role in regulating antioxidant activity in response to stress.

High-temperature stress induces oxidative stress damage in oysters through elevated MDA accumulation [58]. Traditionally, this is mitigated by antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and CAT, which reduce MDA levels under stress [59]. ALDH enzymes also contribute to this defense by converting toxic aldehydes into non-toxic acids, thereby alleviating oxidative stress [54]. For instance, ALDH1A1 mediates the conversion of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde into 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid in neuronal tissues [60], whereas ALDH2 is essential for detoxifying aldehydes derived from lipid peroxidation, including 4-HNE and MDA [29]. In this study, MDA content in the gills of CgALDH6A1-RNAi group oysters significantly increased under 28 °C exposure, while SOD activity, CAT activity, and T-AOC were all significantly decreased. Conversely, MDA content in Alda-1 group significantly decreased, while SOD activity, CAT activity, and T-AOC all significantly increased, suggesting that CgALDH6A1 functions as an antioxidant enzyme by degrading MDA. This is consistent with previous observations that ALDH7B4 degrades MDA under thermal stress [29] and OsALDH7 participates in MDA detoxification during oxidative stress in desiccated rice seeds [61]. Histological analysis showed that CgALDH6A1-RNAi oysters exhibited pronounced gill damage, including filament swelling, while Alda-1-injected oysters showed slight damage, suggesting a functional link between CgALDH6A1 and the antioxidant system. Similar results have been reported for mice, where elevated ALDH activity restores oxidative stress levels through the activation of SOD and CAT and the lowering of MDA [62] and the activation of ALDH2 results in a significant increase in the activities of CAT and SOD and a significant decrease in MDA content [63]. Previous studies have reported that antioxidant mechanisms trigger prior to the formation of MDA, mainly by neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) through specific chemical reactions to alleviate oxidative damage in organisms and indirectly reduce MDA content [64]. As aldehyde dehydrogenases, ALDHs are able to decompose aldehydes such as MDA to mitigate oxidative damage. These results collectively indicate that CgALDH6A1 cooperates with the antioxidant system to jointly alleviate oxidative stress under high-temperature stress.

High temperatures frequently induce oxidative stress and even summer mortality in oysters. Current prevention strategies, including health assessment, environmental monitoring, and screening of disease-resistant strains, remain limited because shellfish health evaluation still depends largely on morphological observation and physiological–biochemical assays [65]. Several indicators related to oxidative damage and antioxidant capacity (e.g., LPS, LTA, MDA, SOD, CAT, and HSPs) have been proposed for early disease warning for aquaculture animals [66,67]. Our study demonstrates that CgALDH6A1 mitigates high-temperature stress in oysters by degrading MDA and interacting with the antioxidant system. Its expression level correlates strongly with oxidative damage and antioxidant capacity, suggesting its potential as an early molecular marker for oxidative stress. This study focused on a single species (the Pacific oyster) under controlled laboratory conditions, constraining the generalizability of the findings to other species or field settings. Future research should expand validation under realistic environmental conditions and further assess the applicability of CgALDH6A1 as a molecular marker. These efforts will support the development of an integrated, multi-target early-warning and management system for sustainable oyster aquaculture.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, 14 ALDH homologues were identified in the genome of the Pacific oyster, among which CgALDH6A1 responded to high-temperature stress. The MDA content in the gills increased significantly after CgALDH6A1 was inhibited via dsRNA injection, while T-AOC and the activities of CAT and SOD all decreased significantly. Meanwhile, the gill filaments were observed to be disorganized with obvious swelling under a microscope. The activation of CgALDH6A1 led to a decrease in gill MDA content, accompanied by significant increases in T-AOC, SOD activity, and CAT activity. However, no obvious morphological change was observed in the gills. These results demonstrate that CgALDH6A1 mediated oxidative stress responses under high-temperature stress through MDA degradation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antiox14121423/s1, Table S1: The ALDH sequences of model organisms used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W. and L.S.; methodology, X.F.; software, X.F.; validation, H.X., J.Y. and L.P., formal analysis, X.F.; investigation, X.F.; resources, L.W. and L.S.; data curation, X.F.; writing—original draft preparation, X.F.; writing—review and editing, L.G. and X.F.; visualization, X.F.; supervision, L.W. and L.S.; project administration, L.G.; funding acquisition, L.W. and L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32373170), the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (SML2023SP237), the earmarked fund for Agriculture Research System (CARS-49), the Outstanding Talents and Innovative teams of Agricultural Scientific Research in MARA, the Scientific Research Project of Liaoning Province Department of Education (No. QL201902), the Liaoning Applied Basic Research Program (2022JH2/101300140), and the Dalian High-Level Talent Innovation Support Program (2022RG14, 2024RJ010).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Dalian Ocean University (approval number: SHOU-23-014), with approval granted on 15 November 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the laboratory members for their technical advice and helpful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALDH | aldehyde dehydrogenase |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| CAT | catalase |

| T-AOC | total antioxidant capacity |

| 4-HNE | 4-hydroxynonenal |

References

- Jackson, B.; Brocker, C.; Thompson, D.C.; Black, W.; Vasiliou, K.; Nebert, D.W.; Vasiliou, V. Update on the aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (ALDH) superfamily. Hum. Genom. 2011, 5, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, A.; Brown, D.; Koutalos, Y.; DeGregori, J.; White, C.; Vasiliou, V. Human aldehyde dehydrogenase 3A1 inhibits proliferation and promotes survival of human corneal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 27998–28006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, C.E.; Brocklehurst, K.; Pickersgill, R.W.; Warren, M.J. Characterization of retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 3. Biochem. J. 2006, 394, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Xiang, Q.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y. The influence of UGT2B7, UGT1A8, MDR1, ALDH, ADH, CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 genetic polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics of silodosin in healthy Chinese volunteers. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2013, 28, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydow, K.; Daiber, A.; Oelze, M.; Chen, Z.; August, M.; Wendt, M.; Münzel, T. Central role of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species in nitroglycerin tolerance and cross-tolerance. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lassen, N.; Pappa, A.; Black, W.J.; Jester, J.V.; Day, B.J.; Min, E.; Vasiliou, V. Antioxidant function of corneal ALDH3A1 in cultured stromal fibroblasts. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 41, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estey, T.; Cantore, M.; Weston, P.A.; Carpenter, J.F.; Petrash, J.M.; Vasiliou, V. Mechanisms involved in the protection of UV-induced protein inactivation by the corneal crystallin ALDH3A1. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 4382–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, J.; Fu, Y.; Shen, L.; Yao, Y.; Guo, J. SpBADH of the halophyte Sesuvium portulacastrum strongly confers drought tolerance through ROS scavenging in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 96, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apraiz, I.; Mi, J.; Cristobal, S. Identification of proteomic signatures of exposure to marine pollutants in mussels (Mytilus edulis). Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2006, 5, 1274–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Gao, L.; Liu, R.; Yang, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, L.; Song, L. The oxidative stress of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas under high-temperature stress. Aquaculture 2023, 577, 739998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segner, H.; Schmitt-Jansen, M.; Sabater, S. Assessing the impact of multiple stressors on aquatic biota: The receptor’s side matters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 7690–7696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, S.; Johnstone, J.; Rahman, M.S. Elevated temperature attenuates ovarian functions and induces apoptosis and oxidative stress in the American oyster, Crassostrea virginica: Potential mechanisms and signaling pathways. Cell Stress Chaperones 2019, 24, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, D.; Tesch, C.; Wencke, P.; Pörtner, H.O. How does oxidative stress relate to thermal tolerance in the Antarctic bivalve Yoldia eightsi. Antarct. Sci. 2001, 13, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Bai, J.; Ma, Z. Physiological adaptations and stress responses of juvenile yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) in aquaculture: An Integrative Review. Aquat. Life Ecosyst. 2025, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchitti, S.A.; Brocker, C.; Stagos, D.; Vasiliou, V. Non-P450 aldehyde oxidizing enzymes: The aldehyde dehydrogenase superfamily. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2008, 4, 697–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanski, J.; Behring, A.; Pelling, J.; Schoneich, C. Proteomic identification of 3-nitrotyrosine-containing rat cardiac proteins: Effects of biological aging. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 288, H371–H381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhai, W. Mechanisms and preventive measures of ALDH2 in ischemia-reperfusion injury: Ferroptosis as a novel target. Mol. Med. Rep. 2025, 31, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliou, V.; Pappa, A.; Estey, T. Role of human aldehyde dehydrogenases in endobiotic and xenobiotic metabolism. Drug Metab. Rev. 2004, 36, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Gao, J.; Shao, X.; Lu, W.; Chen, L.; Jin, L. The effects of Alda-1 treatment on renal and intestinal injuries after cardiopulmonary resuscitation in pigs. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 892472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, W.; Vasiliou, V. The aldehyde dehydrogenase gene superfamily resource center. Hum. Genom. 2009, 4, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, H.; Cai, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, F. Genome-wide characterization and expression analysis of the aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene superfamily under abiotic stresses in cotton. Gene 2017, 628, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliou, V.; Nebert, D.W. Analysis and update of the human aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene family. Hum. Genom. 2005, 2, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, J.D.; Saweikis, M. Aldehyde dehydrogenase is essential for both adult and larval ethanol resistance in Drosophila melanogaster. Genet. Res. 2006, 87, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, J.D.; Bahnck, C.M.; Mikucki, M.; Phadnis, N.; Slattery, W.C. Dietary ethanol mediates selection on aldehyde dehydrogenase activity in Drosophila melanogaster. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2004, 44, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Wu, B.; Dong, Y.; Lin, Z.; Yao, H. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the aldh gene family in Sinonovacula constricta bivalve in response to acute hypersaline stress. Animals 2025, 15, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikas, D. Assessment of lipid peroxidation by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) and relatives in biological samples: Analytical and biological challenges. Anal. Biochem. 2017, 524, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid peroxidation: Production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del, R.D.; Stewart, A.J.; Pellegrini, N. A review of recent studies on malondialdehyde as toxic molecule and biological marker of oxidative stress. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2005, 15, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Missihoun, T.D.; Bartels, D. The role of Arabidopsis aldehyde dehydrogenase genes in response to high temperature and stress combinations. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 4295–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.M.; Lee, M.Y. Differential protein expression associated with heat stress in Antarctic microalga. BioChip J. 2012, 6, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.R.; Hung, H.C.; Leu, J.H.; Wang, H.C.; Kou, G.H.; Lo, C.F. The role of aldehyde dehydrogenase and hsp70 in suppression of white spot syndrome virus replication at high temperature. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 3517–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.Y.; Hsu, Y.J.; Lu, C.Y.; Tsai, M.C.; Hung, W.C.; Chen, P.C.; Tsai, S.H. Pharmacological activation of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 protects against heatstroke-induced acute lung injury by modulating oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 740562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, Q.; Yu, H.; Du, S. Developmental dynamics of myogenesis in Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 227, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerissi, C.; De Lorgeril, J.; Petton, B.; Lucasson, A.; Escoubas, J.M.; Gueguen, Y.; Toulza, E. Microbiota composition and evenness predict survival rate of oysters confronted to Pacific oyster mortality syndrome. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X. Use and exchange of genetic resources in molluscan aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2009, 1, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dégremont, L.; Ernande, B.; Bédier, E.; Boudry, P. Summer mortality of hatchery-produced Pacific oyster spat (Crassostrea gigas). I. Estimation of genetic parameters for survival and growth. Aquaculture 2007, 262, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, T.A.; Morrissey, T.; Geoghegan, F.; Martin, S.W.; Lyons, K.; Ashe, S.; More, S.J. Risk factors associated with increased mortality of farmed Pacific oysters in Ireland during 2011. Prev. Vet. Med. 2014, 113, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, S.; Strand, A.; Bodvin, T.; Alfjorden, A.; Skar, C.K.; Jelmert, A.; Albretsen, J. Summer mortalities and detection of ostreid herpesvirus microvariant in Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas in Sweden and Norway. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2016, 117, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samain, J.F.; Degremont, L.; Soletchnik, P.; Haure, J.; Bédier, E.; Ropert, M.; Boudry, P. Genetically based resistance to summer mortality in the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) and its relationship with physiological, immunological characteristics and infection processes. Aquaculture 2007, 268, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soletchnik, P.; Ropert, M.; Mazurié, J.; Fleury, P.G.; Le Coz, F. Relationships between oyster mortality patterns and environmental data from monitoring databases along the coasts of France. Aquaculture 2007, 271, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Chen, Y.; Cai, G.; Cai, R.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H. Tree visualization by one table (tvBOT): A web application for visualizing, modifying and annotating phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W587–W592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, R.; Yang, C.; Wang, L.; Song, L. Cortisol modulates glucose metabolism and oxidative response after acute high temperature stress in Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2022, 126, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.; Ju, K.; Xu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Luan, X. Structural and biochemical basis of methylmalonate semialdehyde dehydrogenase ALDH6A1. Med. Plus 2024, 1, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duricki, D.A.; Soleman, S.; Moon, D.F. Analysis of longitudinal data from animals with missing values using SPSS. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1112–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Li, J.; Gao, Y.; Mao, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Du, M.; Fang, J. Effects of temperature change on physiological and biochemical responses of Yesso scallop, Patinopecten yessoensis. Aquaculture 2016, 451, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsdon, H.; Brombin, A.; Peterson, S.; Postlethwait, J.H.; Patton, E.E. ALDH2 is a lineage-specific metabolic gatekeeper in melanocyte stem cells. Development 2022, 149, dev200277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliou, V.; Pappa, A. Polymorphisms of human aldehyde dehydrogenases: Consequences for drug metabolism and disease. Pharmacology 2000, 61, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Bartels, D. Comparative study of the aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene superfamily in the glycophyte Arabidopsis thaliana and Eutrema halophytes. Ann. Bot. 2015, 115, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yang, L.; Peng, X.; Mao, M.; Liu, X.; Song, J.; Li, H. ALDH2 Hampers Immune Escape in Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma through ROS/Nrf2-mediated Autophagy. Inflammation 2022, 45, 2309–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.H.; Budas, G.R.; Churchill, E.N.; Disatnik, M.H.; Hurley, T.D.; Mochly-Rosen, D. Activation of aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 reduces ischemic damage to the heart. Science 2008, 321, 1493–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, H.; Nakamura, S.; Sato, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Miyamoto, K.; Oya, A.; Miyamoto, T. ALDH2 mutation promotes skeletal muscle atrophy in mice via accumulation of oxidative stress. Bone 2021, 142, 115739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, L.M.; Mata, C.; Oliveros, A.; Salazar-Lugo, R. Histology of gill, liver and kidney in juvenile fish Colossoma macropomum exposed to three temperatures. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2013, 61, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Henderson, S.; Miller-Ezzy, P.; Li, X.X.; Qin, J.G. Immune response to temperature stress in three bivalve species: Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas, Mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis and mud cockle Katelysia rhytiphora. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2019, 86, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes-Lima, M. Oxygen in biology and biochemistry: Role of free radicals. Funct. Metab. Regul. Adapt. 2004, 1, 319–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galter, D.; Buervenich, S.; Carmine, A.; Anvret, M.; Olson, L. ALDH1 mRNA: Presence in human dopamine neurons and decreases in substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease and in the ventral tegmental area in schizophrenia. Neurobiol. Dis. 2003, 14, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Kim, S.R.; An, G. Rice aldehyde dehydrogenase7 is needed for seed maturation and viability. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Anwaier, G.; Tuerdi, N.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Y. Antrodia cinnamomea triterpenoids attenuate cardiac hypertrophy via the SNW1/RXR/ALDH2 axis. Redox Biol. 2024, 78, 103437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Song, Y.; Pan, J.; Mei, C.; Chen, S. Sirtuin 5—Mediated desuccinylation of ALDH2 alleviates mitochondrial oxidative stress following acetaminophen—Induced acute liver injury. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2402710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, J.; Luo, W.; Niu, S.; Qu, L.; Li, J.; Lu, D. Salicylic acid cooperates with lignin and sucrose signals to alleviate waxy maize leaf senescence under heat stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 4341–4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narbonne, J.F.; Daubeze, M.; Clerandeau, C.; Garrigues, P. Scale of classification based on biochemical markers in mussels: Application to pollution monitoring in European coasts. Biomarkers 1999, 4, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Xiong, D. Nitrite stress disrupts the structural integrity and induces oxidative stress response in the intestines of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. J. Exp. Zool. Part A Ecol. Integr. Physiol. 2018, 329, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleng, N.A.; Sung, Y.Y.; MacRae, T.H.; Abd Wahid, M.E. Non-lethal heat shock of the Asian green mussel, Perna viridis, promotes Hsp70 synthesis, induces thermotolerance and protects against Vibrio infection. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).