β-Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Enhances Skin Barrier Function and Attenuates UV-B-Induced Photoaging in Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Animals

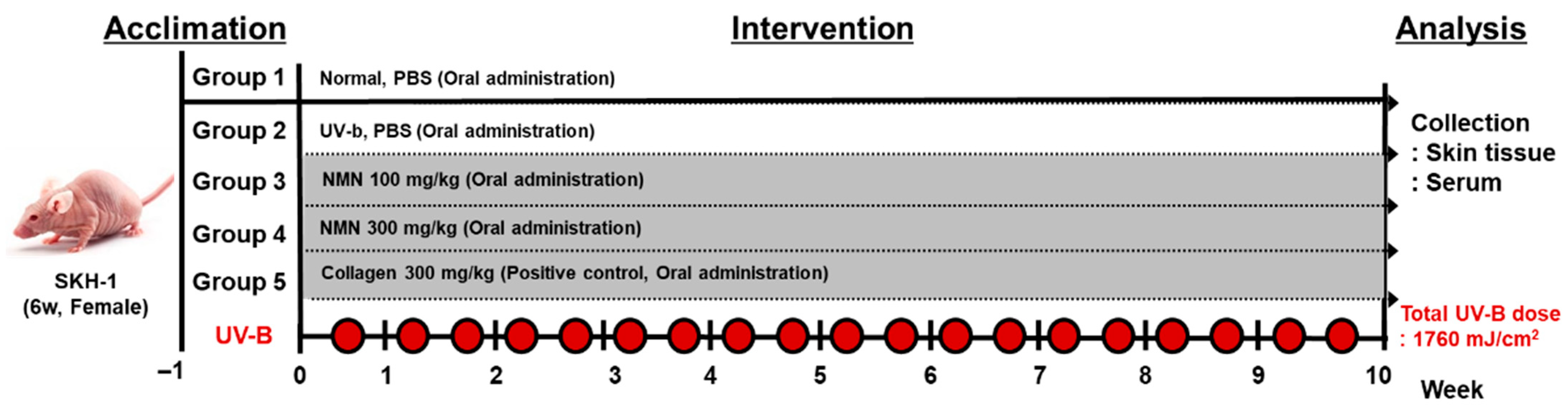

2.3. UV-B-Induced Photoaging and Treatment

2.4. Skin Moisture Measurement

2.5. Skin Elasticity Measurement

2.6. Transepidermal Water Loss (TEWL) Measurement

2.7. Skin Wrinkle and Structure Assessment

2.8. Western Blot Analysis

2.9. Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) Analysis

2.10. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity Assay

2.11. Histological Staining and Analysis

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of NMN Administration on Body Weight in UV-B–Exposed Mice

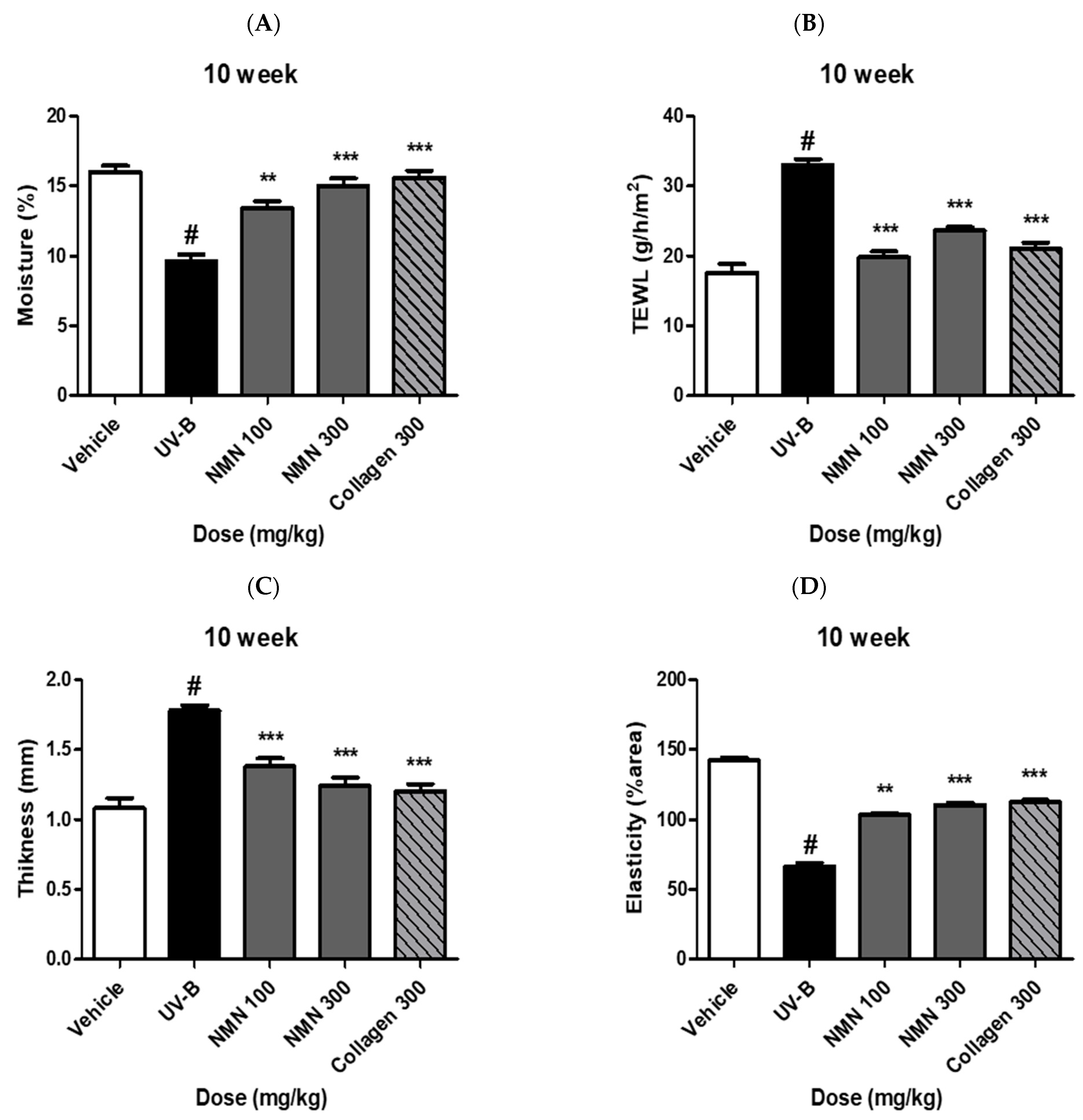

3.2. Effects of NMN Supplementation on Skin Barrier Function

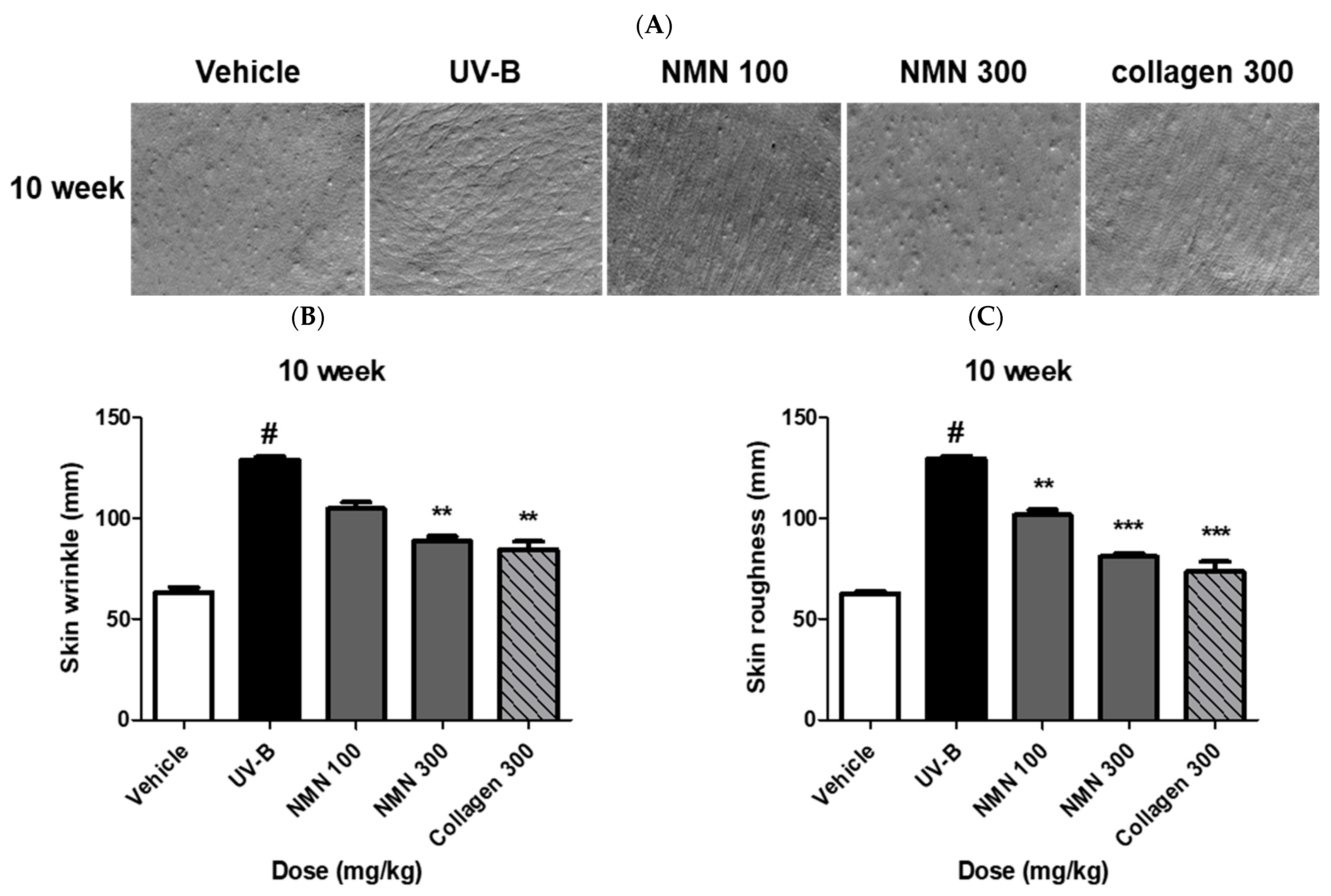

3.3. Effects of NMN Administration on Skin Wrinkles and Roughness

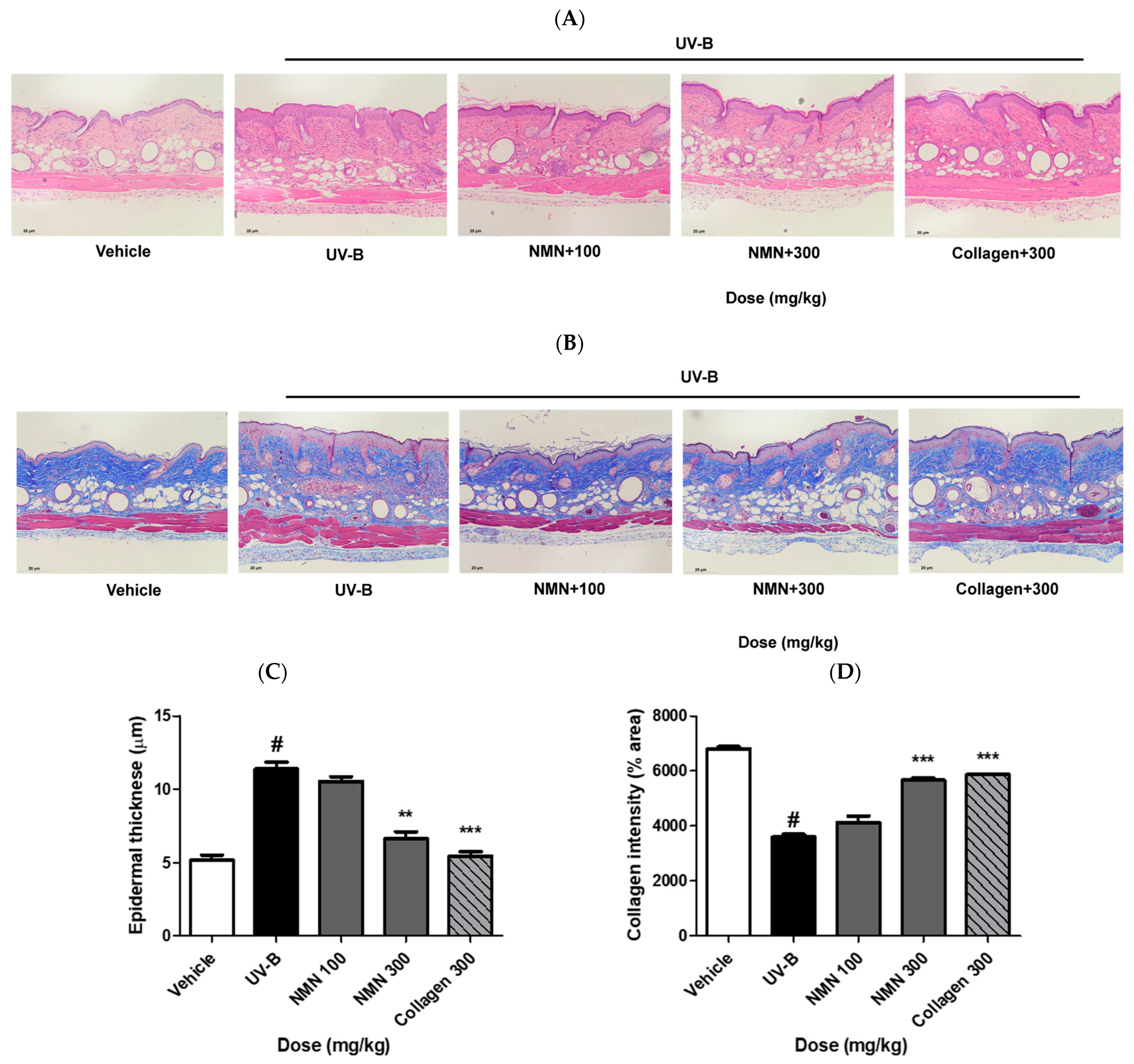

3.4. Effects of NMN Administration on Epidermal Thickness and Collagen Fibers

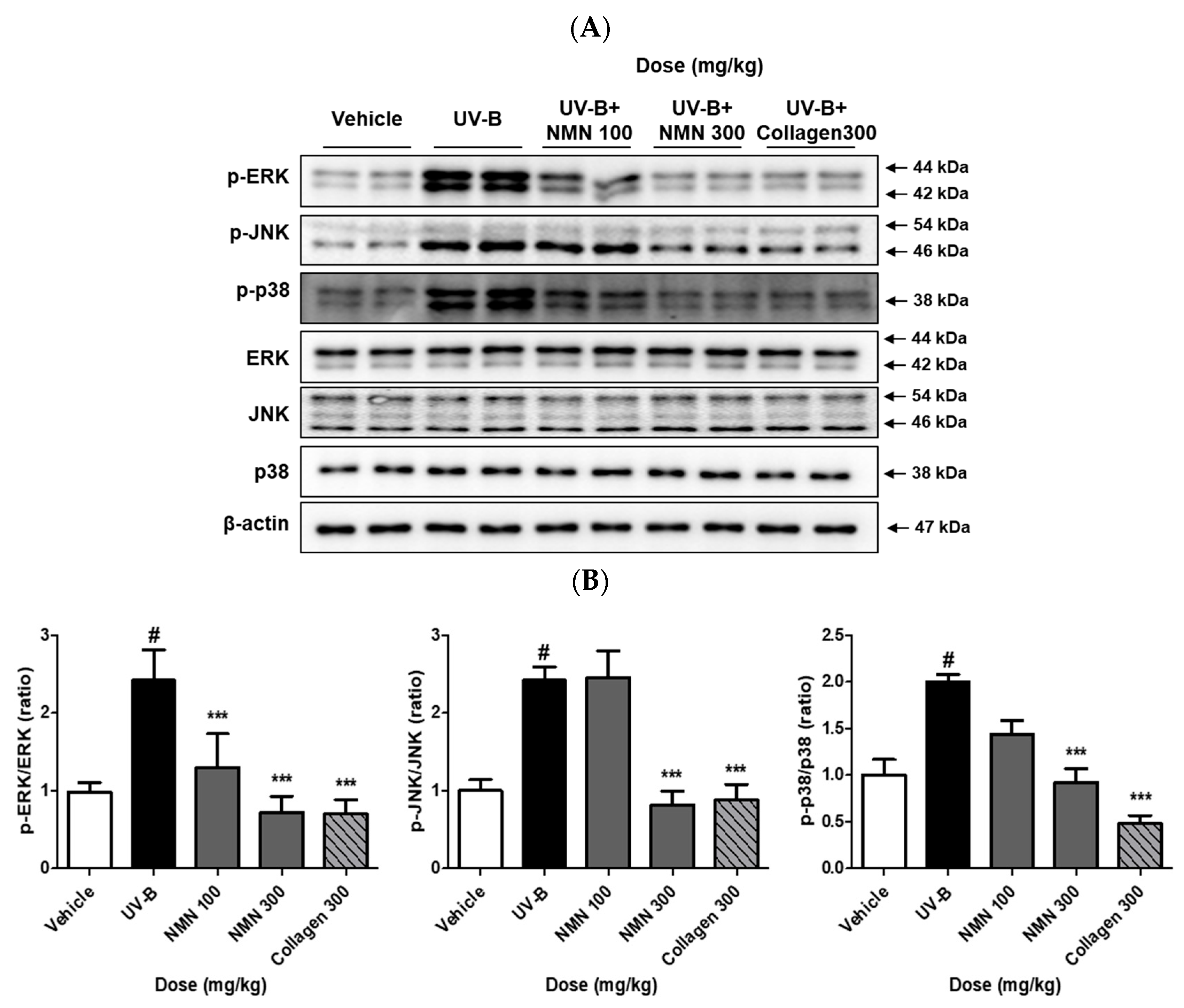

3.5. Effects of NMN Administration on MAPKs Phosphorylation

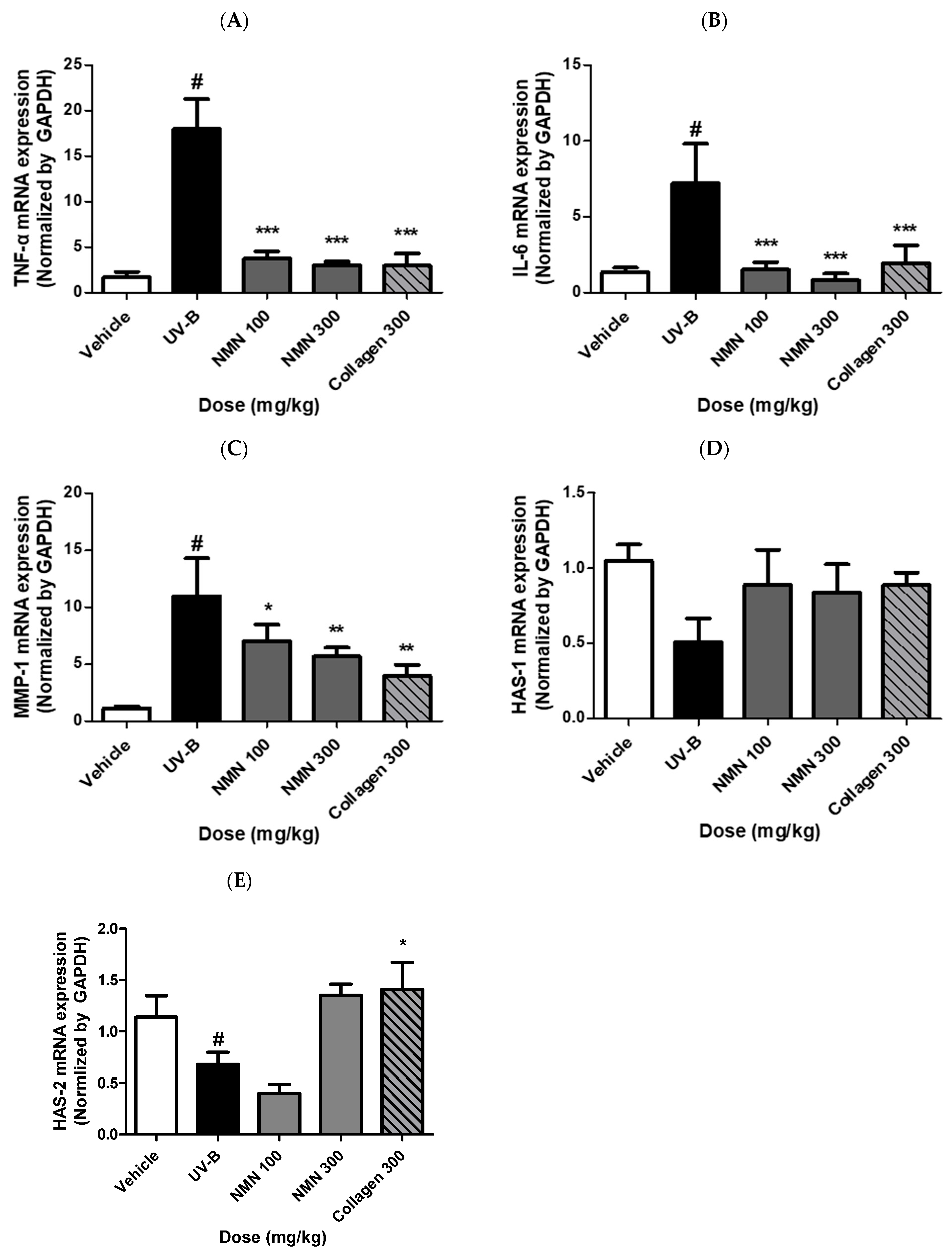

3.6. Effects of NMN Administration on mRNA Expression of Genes Related to Inflammation, Wrinkle Formation, and Skin Hydration

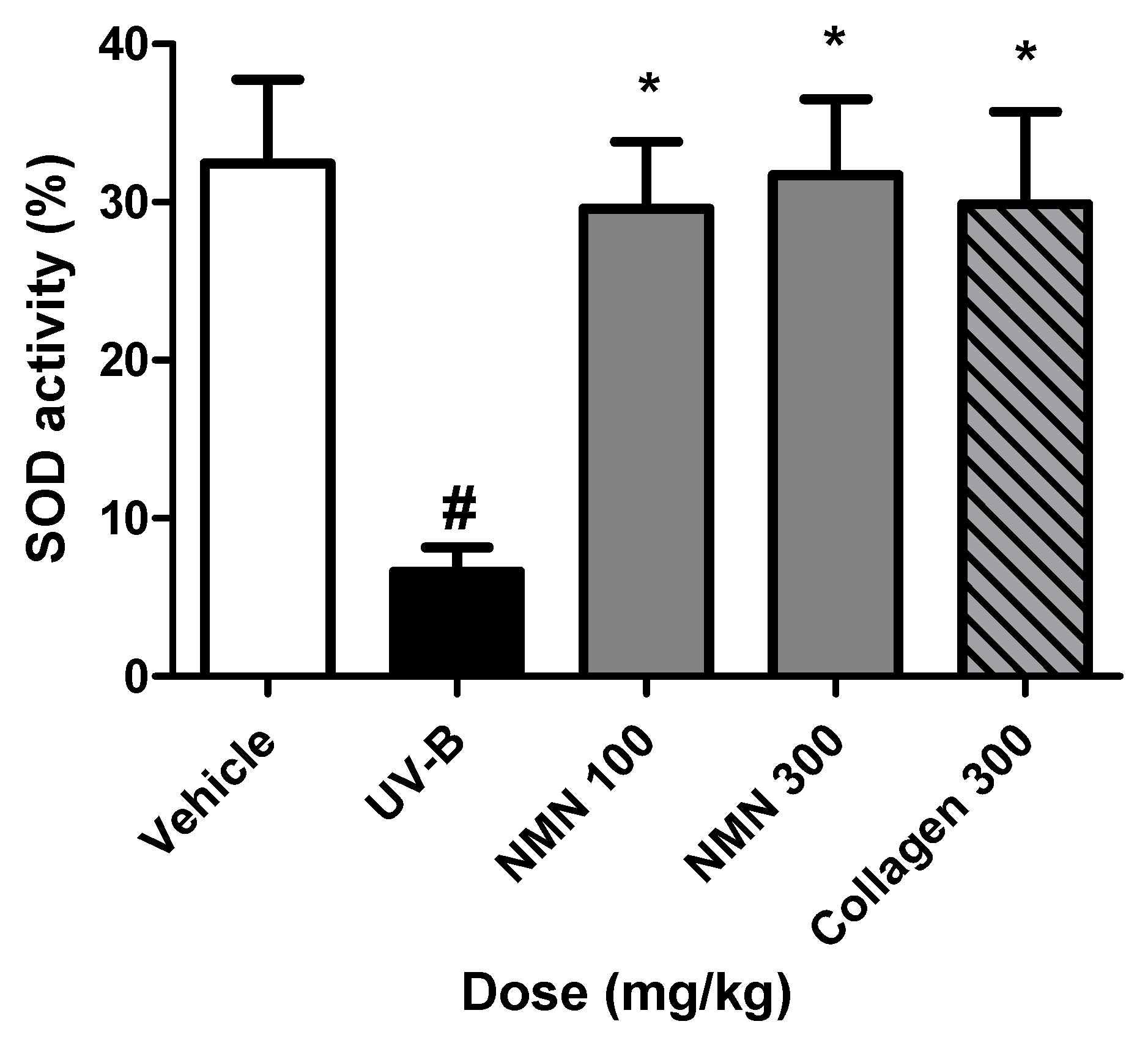

3.7. Effects of NMN Administration on SOD Activity in Serum

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A. Photoaging: UV radiation-induced inflammation and immunosuppression accelerate the aging process in the skin. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 71, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilchrest, B.A. Photoaging. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, E2–E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.J.; Kang, S.; Varani, J.; Bata-Csorgo, Z.; Wan, Y.; Datta, S.; Voorhees, J.J. Mechanisms of photoaging and chronological skin aging. Arch. Dermatol. 2002, 138, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittayapruek, P.; Meephansan, J.; Prapapan, O.; Komine, M.; Ohtsuki, M. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in photoaging and photocarcinogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, H.-M.; Lin, T.-J.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Chang, C.-W.; Hsu, K.-C.; Fan, P.-C.; Wen, K.-C. Coffea arabica extract and its constituents prevent photoaging by suppressing MMPs expression and MAP kinase pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Ma, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Ye, M. Luteolin prevents UVB-induced skin photoaging damage by modulating SIRT3/ROS/MAPK signaling: An in vitro and in vivo studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 728261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Mo, F.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, M.; Wei, X. Nicotinamide mononucleotide: A promising molecule for therapy of diverse diseases by targeting NAD+ metabolism. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, G.F.S.; Pastore, G.M. NAD+ precursors nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and nicotinamide riboside (NR): Potential dietary contribution to health. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, L.; Vafaee, M.S.; Badalzadeh, R. Melatonin and nicotinamide mononucleotide attenuate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via modulation of mitochondrial function and hemodynamic parameters in aged rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 25, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Du, H.-H.; Ni, L.; Ran, J.; Hu, J.; Yu, J.; Zhao, X. Nicotinamide mononucleotide combined with lactobacillus fermentum TKSN041 reduces the photoaging damage in murine skin by activating AMPK signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 643089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oblong, J.E. The evolving role of the NAD+/nicotinamide metabolome in skin homeostasis, cellular bioenergetics, and aging. DNA Repair 2014, 23, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soma, M.; Lalam, S.K. The role of nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) in anti-aging, longevity, and its potential for treating chronic conditions. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 9737–9748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ai, C.; Huang, F.; Zhao, J.-L.; Ling, Y.; Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gao, F.; Li, S. β-Nicotinamide mononucleotide blocks UVB-induced collagen reduction via regulation of ROS/MAPK/AP-1 and stimulation of mitochondrial proline biosynthesis. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2025, 24, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Cruz, G.; León-López, A.; Cruz-Gómez, V.; Jiménez-Alvarado, R.; Aguirre-Álvarez, G. Collagen hydrolysates for skin protection: Oral administration and topical formulation. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihl, C.; Kara, R.D.; Granborg, J.R.; Olesen, U.H.; Bjerring, P.; Haedersdal, M.; Untracht, G.R.; Lerche, C.M. Oral nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) increases tissue NAD+ content in mice but neither NMN nor Polypodium leucotomos protect against UVR-induced skin cancer. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2025, 24, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Im, A.-R.; Shim, K.-S.; Seo, C.-S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.; Yoo, J.S.; Choi, S.; Chae, S. Chikusetsusaponin IVa from Dolichos lablab Linne attenuates UVB-induced skin photoaging in mice by suppressing MAPK/AP-1 signaling. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2024, 67, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.-L.; Bae, Y.-J.; Bang, J.-H.; Jeong, W.-S. Combination of red ginseng and velvet antler extracts prevents skin damage by enhancing the antioxidant defense system and inhibiting MAPK/AP-1/NF-κB and caspase signaling pathways in UVB-irradiated HaCaT keratinocytes and SKH-1 hairless mice. J. Ginseng Res. 2024, 48, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Jang, D.; Lee, M.J.; Shin, M.-S.; Kim, C.-E.; Park, J.Y.; Kang, K.S. Regulation of appetite-related neuropeptides by herbal medicines: Research using microarray and network pharmacology. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2023, 66, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Choi, S.; Kang, K.S. Protopanaxadiol ameliorates palmitate-induced lipotoxicity and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction in INS-1 cells. J. Ginseng Res. 2023, 47, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-R.; Eom, D.H.; Kim, J.H.; Shin, J.-C.; Shin, M.-S.; Shin, K.-S. Composition analysis and oral administered effects on dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis of galactooligosaccharides bioconverted by Bacillus circulans. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 270, 118389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, E.; Choi, J.G.; Choi, Y.; Ju, I.G.; Kim, B.; Shin, Y.-J.; An, J.M.; Park, M.G.; Yim, S.V.; Chung, S.J.P. mirabilis-derived pore-forming haemolysin, HpmA drives intestinal alpha-synuclein aggregation in a mouse model of neurodegeneration. EBioMedicine 2023, 98, 104887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bai, W.; Deng, X.; Wu, Z.; Xu, X.; Ding, W.; Qian, H. Small extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stromal cells loaded with β-nicotinamide mononucleotide activate NAD+/SIRT3 signaling pathway-mediated mitochondrial autophagy to delay skin aging. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryšavá, A.; Vostálová, J.; Rajnochova Svobodova, A. Effect of ultraviolet radiation on the Nrf2 signaling pathway in skin cells. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2021, 97, 1383–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Choi, Y.-J.; Yoo, J.; Choi, S.-Y.; Kim, E. Antiphotoaging Effect of AGEs Blocker™ in UVB-Irradiated Cells and Skh: HR-1 Hairless Mice. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 4181–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, W.-J.; Ahn, J.; Lim, W.; Son, D.J.; Lee, E.; Lim, T.-G. Anti-skin aging activity of eggshell membrane administration and its underlying mechanism. Mol. Cell. Toxicol. 2023, 19, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Du, H.-H.; Long, X.; Pan, Y.; Hu, J.; Yu, J.; Zhao, X. β-Nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) administrated by intraperitoneal injection mediates protection against UVB-induced skin damage in mice. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 5165–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Ai, Z.; Hu, Y.; Cui, L.; Zou, H.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Nan, B. Ginsenosides as dietary supplements with immunomodulatory effects: A review. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2024, 67, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lu, A.; Guan, X.; Ying, T.; Pan, J.; Tan, M.; Lu, J. An Updated Review on the Mechanisms, Pre-Clinical and Clinical Comparisons of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN) and Nicotinamide Riboside (NR). Food Front. 2025, 6, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, L.; Sangwung, P.; Fujioka, H.; Zhang, L.; Liao, X. Short-term administration of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide preserves cardiac mitochondrial homeostasis and prevents heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2017, 112, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-Y.; Lee, C.-Y.; Kim, C.-E. Predicting activatory and inhibitory drug–target interactions based on structural compound representations and genetically perturbed transcriptomes. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayoshi, T.; Nakajo, T.; Tsuji-Naito, K. Restoring NAD+ by NAMPT is essential for the SIRT1/p53-mediated survival of UVA-and UVB-irradiated epidermal keratinocytes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2021, 221, 112238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Lim, W.; Sim, W.-J.; Lim, T.-G. Oral administration of collagen peptide in SKH-1 mice suppress UVB-induced wrinkle and dehydration through MAPK and MAPKK signaling pathways, in vitro and in vivo evidence. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Asteriou, T.; Bernert, B.; Heldin, C.-H.; Heldin, P. Growth factor regulation of hyaluronan synthesis and degradation in human dermal fibroblasts: Importance of hyaluronan for the mitogenic response of PDGF-BB. Biochem. J. 2007, 404, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, S.; Baek, J.-M.; Cha, B.; Heo, H.; Lee, S.-H.; Lei, L.; Jung, S.Y.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, S.H.; Kwak, B.-M. Nicotinamide mononucleotide reduces melanin production in aged melanocytes by inhibiting cAMP/Wnt signaling. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2022, 106, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Assession No. | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | NM_001314054.1 | sense: 5′-GAGGATACCACT CCCAACAG-3′ |

| anti-sense: 5′-AAGTGCATCATCGTTGTT CA-3′ | ||

| TNF-α | NM_013693.3 | sense: 5′-GCCTCTTCTCATTCCTGCTTG-3′ |

| anti-sense: 5′-CTGATGAGAGGGAGGCCATT-3′ | ||

| MMP-1 | NM_032006.3 | sense: 5′-TTGCCCAGAGAAAAGCTTCAG-3′ |

| anti-sense: 5′-TAGCAGCCCAGAGAAGCAACA-3′ | ||

| HAS-1 | NM_010441.3 | sense: 5′-CTATGCTACCAAGTATACCTCG-3′ |

| anti-sense: 5′-TCTCGGAAGTAAGATTTGGAC-3′ | ||

| HAS-2 | NM_008224.4 | sense: 5′-CGGTCGTCTCAAATTCATCTG-3′ |

| anti-sense: 5′-ACAATGCATCTTGTTCAGCTC-3′ | ||

| GAPDH | NM_008084.3 | sense: 5′-GAGGATACCACTCCCAACAG-3′ |

| anti-sense: 5′-AAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTGTTCA-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.J.; Lee, S.; Choi, Y.J.; Kang, M.; Lee, J.; Hwang, G.S.; Roh, S.-S.; Jin, M.H.; Park, S.; Park, M.; et al. β-Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Enhances Skin Barrier Function and Attenuates UV-B-Induced Photoaging in Mice. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121424

Kim SJ, Lee S, Choi YJ, Kang M, Lee J, Hwang GS, Roh S-S, Jin MH, Park S, Park M, et al. β-Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Enhances Skin Barrier Function and Attenuates UV-B-Induced Photoaging in Mice. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121424

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Sung Jin, Sullim Lee, Yea Jung Choi, Minseo Kang, Junghwan Lee, Gwi Seo Hwang, Seok-Seon Roh, Mu Hyun Jin, Sangki Park, Minji Park, and et al. 2025. "β-Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Enhances Skin Barrier Function and Attenuates UV-B-Induced Photoaging in Mice" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121424

APA StyleKim, S. J., Lee, S., Choi, Y. J., Kang, M., Lee, J., Hwang, G. S., Roh, S.-S., Jin, M. H., Park, S., Park, M., Cho, H. S., & Kang, K. S. (2025). β-Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Enhances Skin Barrier Function and Attenuates UV-B-Induced Photoaging in Mice. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121424