Abstract

In the last few decades, scientific evidence has stressed the importance of plants in the prevention and/or supportive treatment of a plethora of diseases, many of them chronic, age-associated disorders. Juglans regia L. is a traditional plant that has been integrated into traditional medicine since ancient times. Due to the presence of biologically active compounds, walnut was used in the treatment of various maladies. Recently, investigations have focused on the walnut by-products and waste products, with research on their valuable constituents and active properties. Among these secondary products, walnut septum was analyzed in several studies, its phytochemical profile described, and some of the biological activities examined. However, compared to other walnut by-products, no comprehensive review to gather all the pertinent scientific knowledge was found in the literature. Therefore, the aim of this study was to critically assess the information furnished by peer-reviewed articles regarding the walnut septum chemical composition and the related biological activities, including antioxidant activities, anti-inflammatory effects, antimicrobial properties, antidiabetic activities, anti-tumor properties, and anti-aging potential. In conclusion, as these preclinical studies showed that walnut septum metabolites were responsible for a wide range of preventive and therapeutic uses, further research should confirm the beneficial outcomes in clinical trials.

1. Introduction

Plant medicine is increasingly used by people due to their interest in complex natural products that are as compatible as possible with the human organism and have as few side effects and adverse reactions as possible. Therefore, the use of herbal remedies must be based on scientific evidence, including recent biological screening methods in combination with analytical approaches [1]. Diets rich in fruits, vegetables, and nuts are commonly recommended for their health benefits due to their concentrations of vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals, and dietary fiber [2].

Nuts and seeds, along with whole grains, vegetables, fruits, and legumes, are essential components of globally recommended healthy diet patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet [3] and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet [4]. Tree nuts and peanuts are nutrient-dense foods with complex phytochemical matrices [5]. They are rich in unsaturated fatty acids, folic acid, vitamin E, potassium, calcium, magnesium, phytosterols, polyphenols, and fiber [5].

Among the tree nuts, walnut (Juglans regia L.) is a valuable cultivated tree, widely appreciated for its fruits [6]. The walnut seed, or kernel, is rich in lipids, predominantly unsaturated fatty acids (MUFA and PUFA), phytosterols, tocopherols, proteins, minerals, and a number of antioxidant chemicals, such as phenolic compounds [7,8,9]. It has an important medicinal value and health function in preventing and alleviating cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and obesity [7]. Some walnut by-products have been studied and shown to be rich in bioactive constituents [10]. Walnut leaves, husks, and shells contain key phenolic compounds and are often used in traditional medicine to treat different ailments [6,11]. Walnut skin, or pellicle, is the thin, brown coating that prevents oxidation and microbial contamination of the seed [11]. It is walnut’s main source of polyphenols with powerful antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capacities [6].

Walnut septum (WS), a by-product that is frequently discarded as waste during walnut processing, has a phytochemical profile that defines the therapeutic potential. Recent studies exposed that WS contains many bioactive phytochemicals, with demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo biological activities including anti-aging potential [12,13,14].

The aim of this study was to critically examine and synthesize available data on the chemical composition and biological activities of WS. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first exhaustive systematic review of this plant matrix, and it reveals that WS metabolites could be responsible for many preventive and therapeutic actions.

2. Search Methodology

The current systematic review was performed following the PRISMA criteria guidelines [15]. The registration code is INPLASY202320075, with DOI 10.37766/inplasy2023.2.0075, https://inplasy.com/?s=INPLASY202320075 (accessed on 16 February 2023).

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Our systematic review included studies performed on walnut septum plant material or walnut septum with the following objectives: (1) identification and/or quantification of phytochemical compounds; (2) examination of the biological activity of identified compounds via in vivo and in vitro testing; and (3) English and French publications. We excluded: (1) abstracts, narrative reviews, comments, opinions, methodological papers, editorials, letters, observational studies, conference abstracts, or any other publications lacking primary data and/or explicit method explanations; (2) publications with full text not available and the corresponding author could not be contacted; and (3) duplicate studies or databases.

2.2. Information Sources

We performed a systematic literature search in PubMed, EMBASE, and ClinicalTrials.gov databases for studies describing the phytochemical profile and biological activity of walnut septum from the inception of each database through to 31 January 2023. The literature search had no language constraint. To ensure thorough research, the bibliographies of the included studies and current reviews were also screened.

2.3. Search Strategy

To search the databases, we used a combination of free-text words, along with their synonyms, singular and plural forms, thesaurus words (Medical Subject Headings for PubMed: (“juglans” [MeSH Terms] OR “juglans” [All Fields] OR “walnut” [All Fields] OR “walnuts” [All Fields] OR “juglans regia” [All Fields] OR “juglans nigra” [All Fields]) AND (“septum” [All Fields] OR “septa” [All Fields] OR “diaphragma juglandis” [All Fields] OR “diaphragma juglandis fructus” [All Fields] OR “internal septum” [All Fields]), and Emtree for EMBASE: (‘juglans’/exp OR ‘juglans’ OR ‘walnut’ OR ‘walnuts’ OR ‘juglans regia’ OR ‘juglans nigra’ OR ‘english walnut’ OR ‘persian walnut’) AND (‘walnut septum’ OR (‘walnut’ AND ‘septum’) OR ‘diaphragma juglandis’ OR (‘diaphragma’ AND ‘juglandis’) OR ‘walnut internal septum’ OR (‘diaphragma’ AND ‘internal’ AND ‘septum’)).

2.4. Selection Process

All three authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of relevant journal publications. Then, the full texts of the documents that appeared to meet the selection criteria were collected for additional screening. Each full text was independently evaluated by the same researcher. In the event of discord, the research was discussed until a consensus was achieved. In cases where there were numerous publications from the same trial, only the most relevant or useful article was selected.

2.5. Data Items

Data regarding the outcomes were extracted in a spreadsheet Microsoft (Microsoft Office 365, MS, Redmond, WA, USA) Excel file contained the following data: materials/type of extract, phytochemical composition studies, in vitro studies/ biological systems analysis methods, and in vivo studies/animal models. Furthermore, data regarding study characteristics were extracted in a spreadsheet file: country, study design, study purpose, and study outcomes.

Other investigators than those who extracted the initial full-text articles rechecked the extracted data.

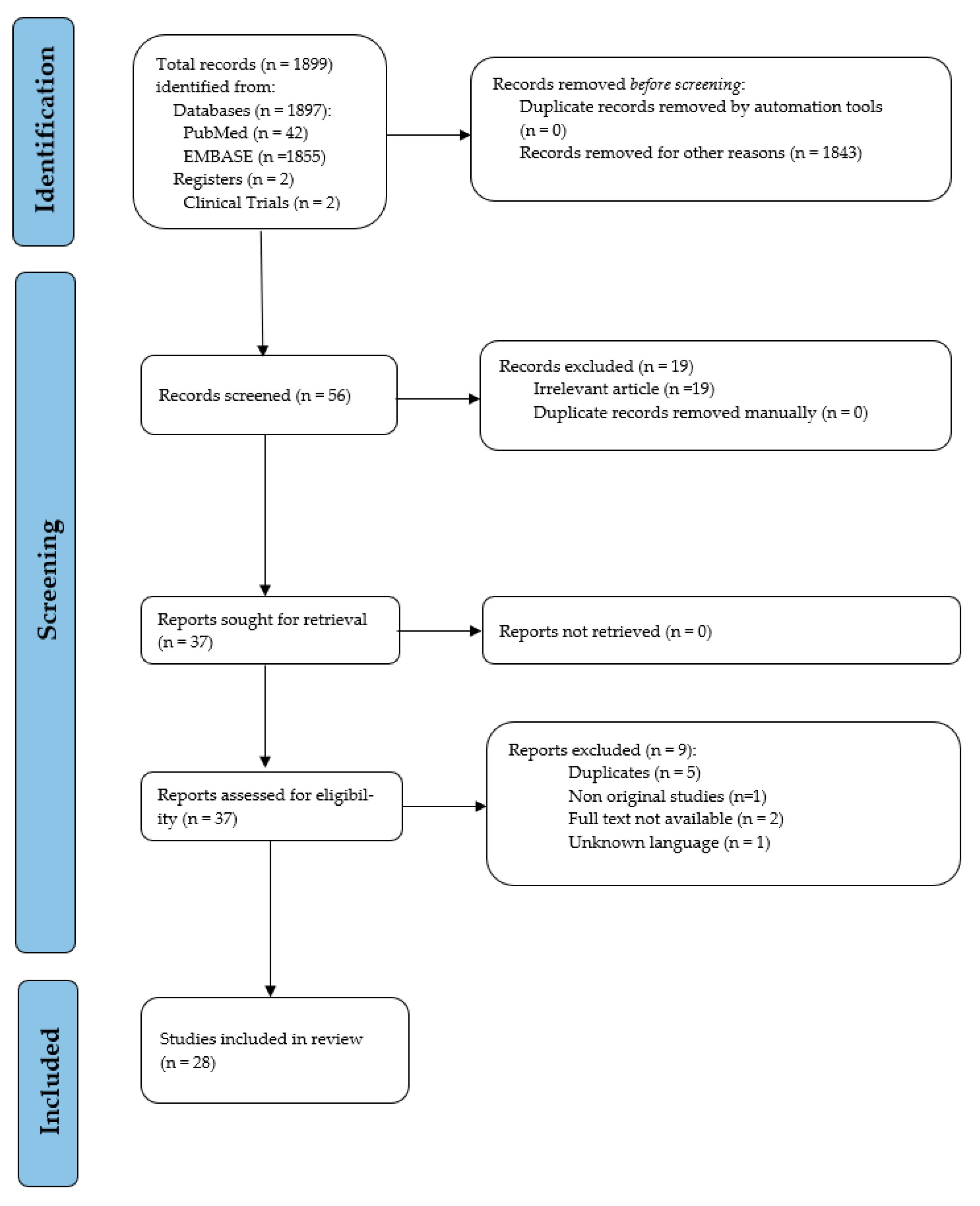

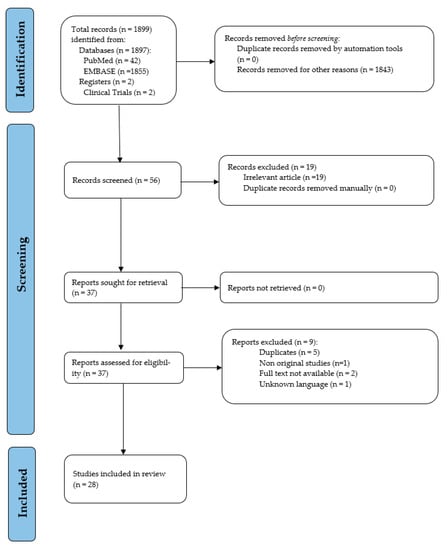

A total of 56 articles were considered from the systematic search and review of relevant reference lists. After applying exclusion criteria, 28 articles were included in the systematic review. The procedure of study inclusion and exclusion is shown in Figure 1. The characteristics of included studies are revealed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the selected studies.

3. Phytochemical Composition

The phytochemical composition of walnut septum was examined in 13 out of the 28 studies selected for this review. Five of these provided quantitative determination results that could be analyzed and compared in our study [24,27,32,37,40] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Phenolic compounds identified and quantified in walnut septum.

The reviewed investigations determined the phytochemical profile focusing on the examination of the phenolic compounds, lipids, carbohydrates, amino acids, and mineral compositions.

Eleven studies examined phenolic components, including phenolic acids and their esters, flavonoids, tannins, lignans, and phenylpropanoids. Fatty acids, phytosterols, tocopherols, terpenoids, and carotenoids were among the lipid constituents identified, while the monosaccharides and polysaccharides were the main carbohydrates of walnut septum. Other compound types including coumarins, quinones, and alkaloids, known to be present in various matrices of Juglans regia L., are less extensively explored and discussed in these articles. However, the representative data for these compounds, extracted from the selected studies, are presented in this review.

3.1. Phenolic Compounds

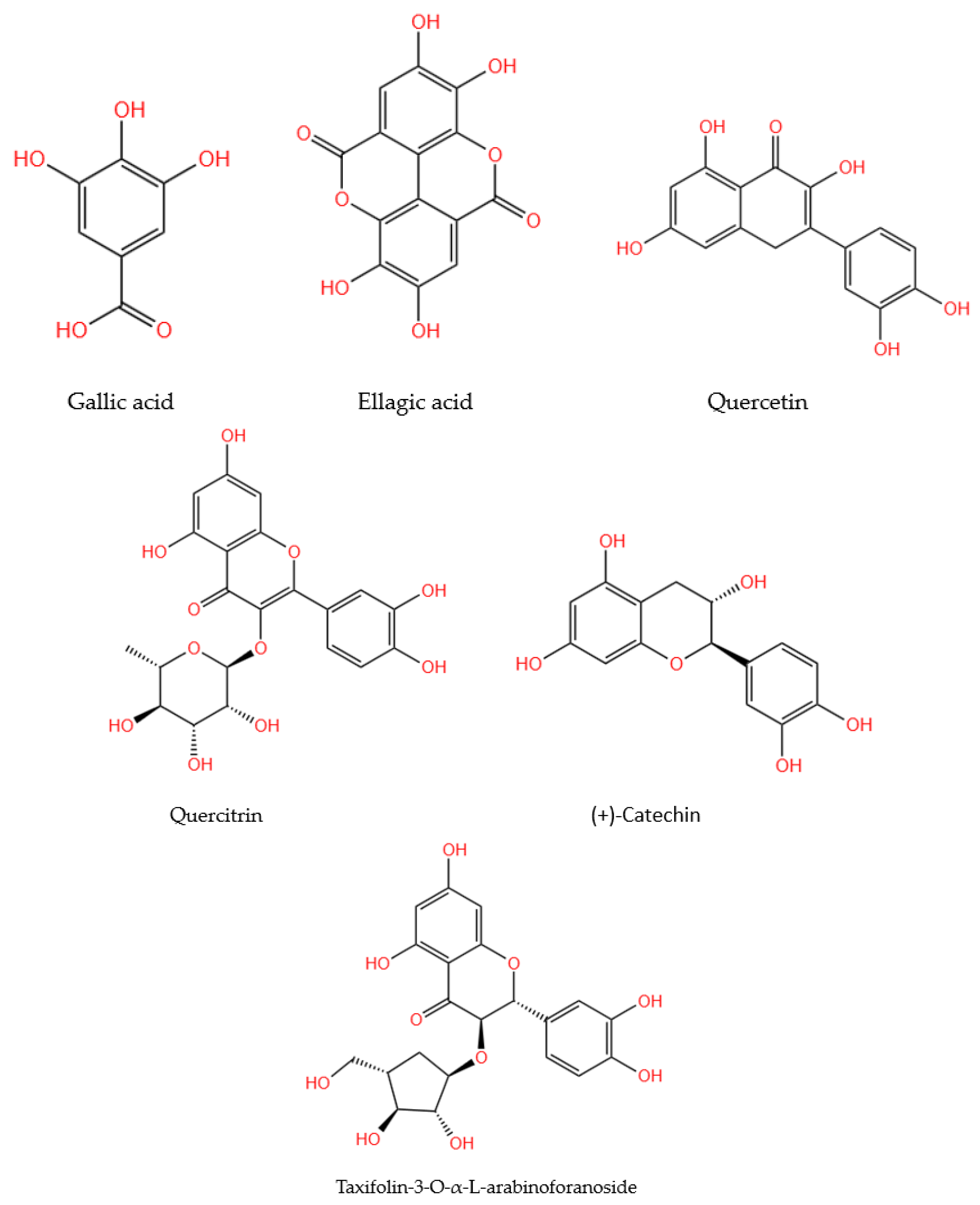

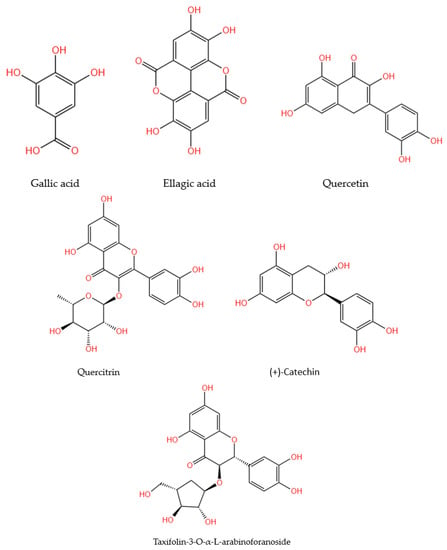

The research that identified phenolic compounds in the walnut septum was summarized, according to their methodology, in Table 2. The chemical structures of quantitatively representative phenolic compounds found in walnut septum were illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of the main phenolic compounds identified and quantified in walnut septum.

It is widely recognized that the extraction yield and the conservation of the structural and biological properties of valuable components are highly dependent on the extraction method applied [41].

Most of the reviewed studies reported the usage of WS in powder form, following the preparatory grinding of plant material. The extractions were conducted in ethanol [20,22,38,40] or methanol [26,27,32] at various concentrations, as well as in solvent mixes such as acetone:water [24], acetone:acetonitrile [25], and acetone:cyclohexane [27]. The extraction methods were generally based on ultra-turrax homogenization and stirring [24], vibrating [25], ultrasonic extraction [26,27,37], condensation and reflux, or enzyme-assisted extraction [32], then centrifugation, solvent evaporation, and lyophilization. A number of studies described preserving the lyophilized material at −20 °C [25,26,32], while others stored it at room temperature [24] (Table 2).

The reviewed studies used various chromatographic techniques for identifying phenolic compounds: liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) [24], liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [32], high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [20,22,26,37,38], or ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) differently equipped: UPLC-MS (17), UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry HRMS [27], or UPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap MS [40].

In order to quantify the detected compounds, the majority of the studies utilized electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) with positive and/or negative mode, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR): 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, and ultraviolet (UV) spectroscopy (280–360 nm).

The phenolic compounds identified in WS belong to the following classes: phenolic acids (hydroxybenzoic, hydroxycinnamic, hydroxyphenylacetic acids), and some of their esters: flavonoids (flavones, flavonols, chalcones, anthocyanins, flavanones, flavanols), tannins (gallotannins, ellagitannins, complex tannins), lignans (cyclolignans, monoepoxylignan, benzofuran lignan), phenylpropanoids (phenylpropionic acids, phenylpropanols), as well as other classes (hydroxybenzaldehydes).

In the selected studies, the following hydroxybenzoic acids were analyzed: benzoic acid [40], p-hydroxybenzoic acid [22,32,40], 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 3,4-hydroxybenzoic acid [40], p-coumaroylquinic acid [26,32], ellagic acid [26,27,32], gallic acid [22,24,25,26,27,40] gentisic acid [24], protocatechuic acid [22,24,27,32], syringic acid [24,32,40], and vanillic acid [22,24,25,40] (Table 2).

In the quantitative analyses, Liu R. et al. [27] obtained significant amounts of ellagic acid with a range of 518.38 to 1733.64 μg/g dw for the ten batches investigated. It is noteworthy that the concentration of ellagic acid was comparable to or even higher than that of other plant sources [27]. Similarly, Zhang et al. [32] reported the highest amount of ellagic acid (351.92 g/g dw) for methanolic condensation reflux extraction (ME) for all three tested methods.

Gallic acid was quantitatively assessed in three investigations [24,27,40] with comparable results. In one research [24], gallic acid was found in a significantly higher concentration (79.58 µg/g dw) compared to other detected phenolic acids (protocatechuic, syringic, and vanillic acids). However, this concentration was lower than that determined by Liu R. et al. [27]. The highest quantity of gallic acid (272.52 μg/g dry weight) was encountered in the study of Chen et al. [40].

Protocatechuic acid was found in substantial amounts (a range of 44.28–154.04 μg/g dw in ten samples) compared to the other hydroxybenzoic acid compounds investigated [27].

Hydroxycinnamic acids detected and described were caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, neochlorogenic acid, caftaric acid, ferulic acid and its isomer, p-coumaric acid, and sinapic acid (Table 2). Among them, the isomer of ferulic acid has the highest concentration (87.96 µg/g dw) in ME [32].

Flavonoids are low-molecular-weight secondary metabolites [42]. The flavonoids identified in this research included flavones (apigenin, luteolin, and vitexin), flavonols (isorhamnetin, kaempferol, dihydrokaempferol, myricetin, myricetol, dihydrokaempferol, quercetin, avicularin, hyperoside, rutin, and various quercetin glycosides, quercitrin, taxifolin, taxifolin-3-O-arabinofuranoside, taxifolin 3-rhamnoside), chalcones (naringenin chalcone), anthocyanins (B-type procyanidin dimer, trimer, tetramer, pentamer, hexamer, and their isomers), flavanones (naringenin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, sakuranetin 5-O-β-D xylopyranoside, (2R)-eriodictyol-5-O-β-D-glucoside), flavanols ((−)-epicatechin, (+)-catechin, (−)- epicatechin gallate).

Fruits and vegetables, herbal tea, and red wine are rich in flavonols, which give them a spectrum of colors from white to yellow. The most prevalent flavonol found in plant sources was quercetin [43]. Quercetin [32,40], isoquercetin [24,40], quercitrin [24,40], taxifolin-3-O-arabinofuranoside [27], catechin [24,27,40], epicatechin [40], and epicatechin gallate [27] were detected in walnut septum in significant quantities compared to other components. Among all the assessments, [40] found the highest values for these compounds: quercetin (54.10 μg/g dw), isoquercetin (399.00 μg/g dw), quercitrin (6816.18 μg/g dw), catechin (9989.16 μg/g dw), and epicatechin (362.10 μg/g dw) (Table 2).

Gallotannins, such as monogalloyl-glucose, digalloyl-glucose, trigalloyl-glucose, and tetragalloyl-glucose [32], as well as their isomers [26], methyl galloyl hexoside, and caffeoyl glucopyranose isomer [32], were detected in the selected studies for this review. Although in very small amounts compared to the other phenolic compounds, monogalloyl-glucose (4.87 μg/g dw, EE) and trigalloyl glucose (4.90 μg/g dw, ME) stood out for their higher amounts between the investigated tannins in the study of Zhang et al. [32].

Elagitanins were identified as ellagic acid hexoside, elagic acid pentoside, and isomers, bis-HHDP glucose [26], HHDP-glucose isomer, and galloyl-HHDDP glucose [26,32]. Quantitatively, distinct compounds were the HHDP-glucose isomer (6.75 μg/g dw, EE) and galloyl-HHDP glucose (5.77 μg/g dw, ME) [32].

The investigation performed by Tan et al. 2022 (a) [38] also reported cyclolignans (5-methoxy-(+)-isolariciresinol), monoepoxylignans (erythro-guaiacyl-glycerol-β-O-4′-(5′)-methoxylariciresinol), rhoiptelol B, and benzofuran lignans (dihydrodehydodiconiferyl alcohol). However, these compounds were not quantified. Certain phenylpropanoic compounds, including 1,6-di-O-(E)-coumaroyl-D-glucopyranoside (phenylpropionic acid) and various phenylpropanols, among them erythro-(7S,8R)-guaiacyl-glycerol-O-4′-dihydroconiferyl ether and rosalaevin B were also identified in the same study.

3.2. Lipidic Compounds

The studies that identified lipidic compounds in the walnut septum, along with their methodology, are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Lipidic compounds identified and quantified in walnut septum.

The lipidic molecules were identified in three of the thirteen investigations that aimed to define the phytochemical composition of walnut septum [12,24,25] and include fatty acids [25], phytosterols [24], and tocopherols [12].

In the study of Hu Q. et al. (2019) [25], the total amount of reported saturated fatty acids (SFAs) was 1099.10 mg/kg dw, with the highest quantity in palmitic acid (C16:0). The proportion of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in WS was 63.5%, with a prevalence of linoleic acid (18:2) and oleic acid (18:1 cis-9). Small amounts of other PUFAs including eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5, n-3), arachidonic acid (20:4, n-6), and nervonic acid (24:1, n9) were also found in WS.

According to the quantitative analysis of the phytosterols beta-sitosterol was found to be ten times more abundant (31,018.16 µg/g dw) than campesterol in the analyzed sample of WS [24]. The identified quantities of tocopherols were significantly lower than those of phytosterols, with a predominance of α-tocopherol [24].

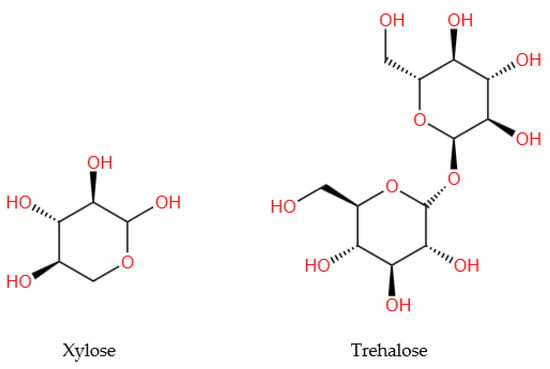

3.3. Carbohydrate Compounds

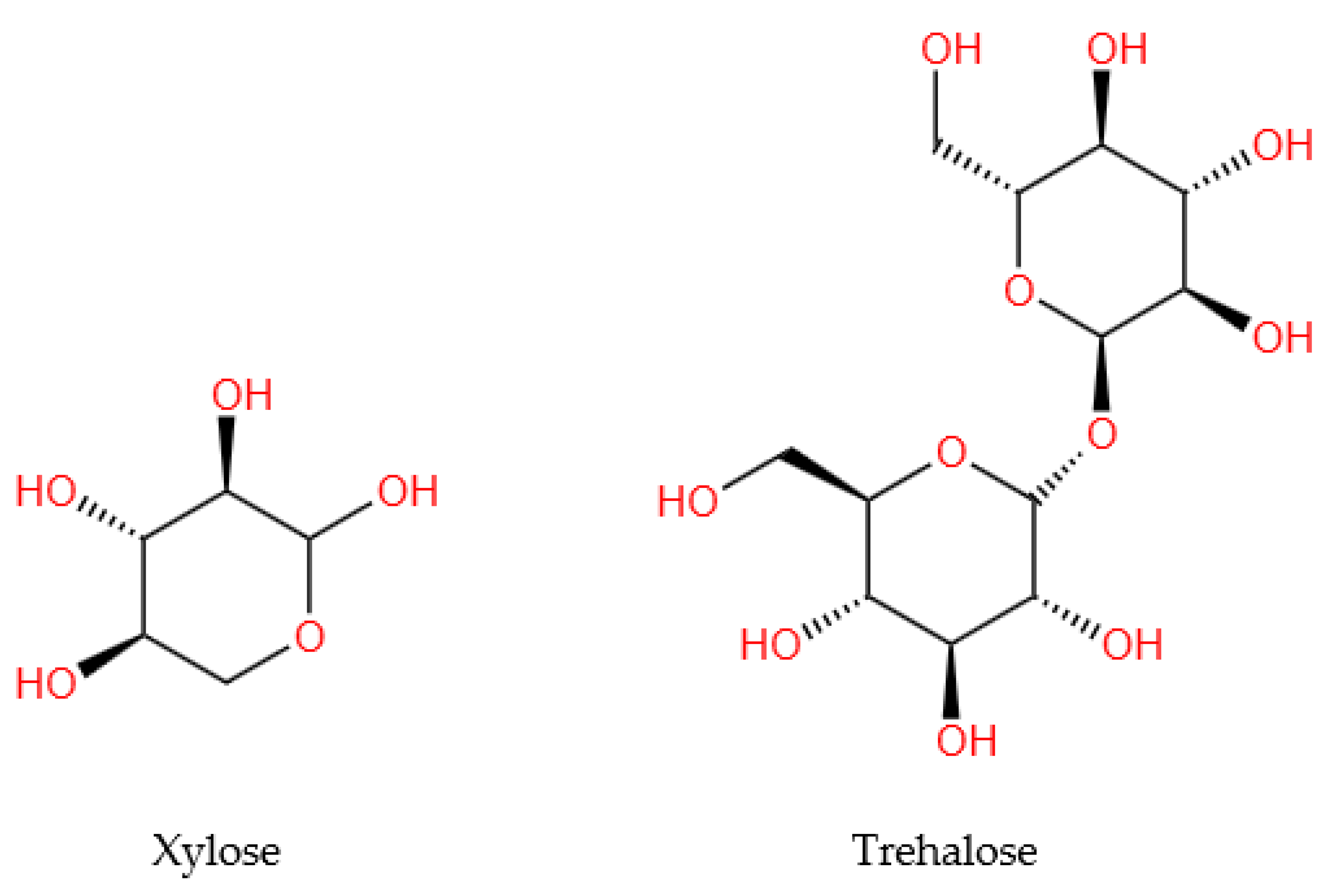

Of the 13 analyzed studies, only two [23,25] reported the evaluation of carbohydrates (monosaccharides and polysaccharides) in WS, of which only one [25] provided information on their quantity. The extracted data were systematized in Table 4, and the structures of the representative compounds (trehalose and xylose) were presented in the Figure 3.

Table 4.

Carbohydrate compounds identified and quantified in walnut septum.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of the main carbohydrate compounds quantified in walnut septum.

3.4. Other Compounds

This category consists of other compounds identified in WS, which were presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Other compounds identified and quantified in walnut septum extracts.

Apart from the previously presented compounds, sesquiterpenoids quinones, coumarins, amino acids, and minerals were also identified in WS.

The majority of the sesquiterpenoid compounds were megastigmanes, including blumenol B [22,25,38], blumenol C glucosides [22,38], and diamegastigmanes (A, B, and C) [38]. This class also includes taraxasteranes (Juglansin A, B, C, and D) [38]. In the study conducted by Hu et al. [25], glutamate and lysine were quantitatively highlighted among the amino acids identified in WS, whereas Ca, K, and Mg were the most abundant minerals (Table 5).

4. Biological Activities

Table 6 summarizes the studies reported in the scientific literature that highlight the biological activities of walnut septum extracts or compounds isolated from walnut septum.

Table 6.

Biological activities reported on in vivo studies performed with walnut septum extracts or compounds isolated from walnut septum.

4.1. Antioxidant Activities

The overproduction of free radicals, such as ROS and RNS, could generate oxidative impairment to biomolecules and consequently lead to many chronic ailments including cardiometabolic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancers [45]. ROS form in mammalian cells and have distinct effects on oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and biological aging. Therefore, controlling and targeting ROS sources and overproduction are measures involved in antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, or healthy aging therapeutics [46].

Antioxidants are important molecules and play key roles in food industry against oxidative deterioration of products and against oxidative stress-mediated pathological processes in the body. Several tests were used to determine the antioxidant activity of extracts of walnut septum. The most common methods were DPPH and ABTS, discoloration assays based on electron or hydrogen atom donation, and the ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay, a color-formation reaction applicable for both in vitro and in vivo experiments that is based on electron transfer rather than hydrogen atom transfer [47].

Various studies reported the antioxidant activities of phytochemicals in walnut matrices [6]. One of our previous experiments showed good antioxidant activity via ABTS assay for the 75% and 50% acetone septum extracts at 174.28 ± 8.22 and 168.62 ± 9.68 mg TE/g dw septum, respectively, both samples obtained by the UTE method [24]. The best DPPH radical scavenging activity was expressed by an equal acetone/water septum extract [24]. The two antioxidant activities were positively influenced by the number of hydroxyls present in the aromatic ring of the extract phenolics.

Similarly, Zhang et al. revealed that the septum antioxidant capacity increased in a phenolic concentration-dependent manner. Moreover, the antioxidant activity was also affected by the extraction method applied. Thus, septum extracts obtained using methanolic condensation reflux extraction were more active compared to extracts derived through enzyme-assisted (EAE) and ultrasonic wave-assisted extraction (UWAE) methods [32].

The DPPH and FRAP test results of Mehdizadeh et al. demonstrated high antioxidant capability of the septum hydroalcohol extracts compared to butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) [28].

Hu et al. analyzed the antioxidative effects of two extracts, water and alcohol septum samples obtained using hot water (1:20 w/v) at 85 °C and 70% ethanol at room temperature, respectively [35]. Both extracts exposed significant HepG2 cell protective capacities and were capable of scavenging DPPH and ABTS in dose-dependent manners [35].

As the major ROS contributor in cells, H2O2 is considered relevant to endogenous oxidative stress. Treatment with septum extract significantly ameliorated the oxidative damage in a concentration-dependent manner in human hepatic L02 cells exposed to H2O2 and the polysaccharides found in septum were found to be the active molecules [29]. These saccharides, mostly glucose, followed by galactose and arabinose, and trace amounts of xylose and mannose, indicated that they had antioxidant and bacteriostatic activities [21].

The antioxidant effect of the WSE was evaluated on cancerous (A549, T47D-KBluc, and MCF-7) and normal (human gingival fibroblasts (HGF)) cell lines. In the non-stimulated conditions, as well as the H2O2-stimulated conditions, the septum extracts decreased the quantity of ROS in a dose-dependent manner [12]. Using the DCFH-DA assay, a dose-dependent and statistically significant decrease of ROS in lung tissues was also noticed, exposing the ability of WSE to mitigate oxidative stress [36].

Tocopherols, key lipophilic radical-scavenging antioxidants, could interrupt the lipid peroxidation cycle. In addition to their direct action against ROS, quercetin glycosides and tocopherols revealed an indirect antioxidant potential by activating the Nrf2/ARE pathway, thus initiating the synthesis of cellular antioxidants including [12]. Other antioxidant biomolecules from septum are the ellagitannins and ellagic acid that could modulate oxidative stress and inflammatory actions via urolithins, their gut microbiota metabolites [48].

The antioxidant activity of septum extracts was also researched on animal aging models, both in old rats and in D-gal-aged young rats [31]. Measured by the TEAC assay, the antioxidant activity in the brain of old Wistar rats significantly increased after repeated (8 weeks) septum extract intake compared to control (9.585 ± 0.287 mg TE/100 g, p < 0.05). The septum treatment also improved, but was not statistically significant, the antioxidant activity in the liver when measured by the DPPH assay. Moreover, several oxidative stress biomarkers were lowered after repeated (8 weeks) septum extract intake in old rats. In the liver and brain, ROS, AGE, NO, and MDA levels were reduced after septum treatment but only the liver MDA level was statistically decreased.

However, all these parameters were significantly lowered in the analyzed organs in young animals treated with D-gal to induce aging. The trend was also noticed for acetylcholinesterase (AChE) levels in the brains of both age-groups. Although, as mentioned above, the ROS, AGE, NO, and MDA biomarkers were not significantly modified in old rats after 8 weeks of septum extract treatment, it could be possible that longer time periods of supplementation could statistically impact these indices. The levels of glutathione, a key endogenous antioxidant molecule related to cellular detoxification and redox homeostasis, were increased, although not significantly, after septum extract consumption in this in vivo experiment [31].

In a subacute toxicity study, elevations in the serum, liver, and kidney MDA levels after treatment with a septum methanol extract were noticed, but no severe subacute toxicity was observed for doses of 1000 mg/kg bw after 4 weeks of repeated administration [19].

Recently, Chen et al. evaluated the antioxidant effects of WSE on refined soybean oil during deep frying [40]. The septum extract effectively delayed the thermal oxidation of unsaturated triglycerides and inhibited the formation of potentially toxic components, such as oxidized triglyceride monomers and polymers, or toxic aldehydes. These outcomes could be due to the antioxidant capabilities and synergistic activities of the 31 polyphenols determined in the septum extract, the main compounds being catechin, quercitrin, taxifolin, quercetin 3-β-d-glucoside, epicatechin, gallic acid, and 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid [40].

4.2. Anti-Inflammatory Effects

The anti-inflammatory effects of fourteen isolated molecules from septum were evaluated by an in vitro model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated murine RAW 264.7 macrophages. Gallic acid, ethyl gallate, and (+)-dehydrovomifoliol were major components that showed potent inhibitory activity on the nitric oxide production (suppression of 70% of NO production) [22]. However, it was highlighted before that relying only on RAW 264.7 cells to assess immune reactivity might not furnish an extensive picture of the bioactive properties of the investigated matrix [49].

Additionally, the ability of WSE to inhibit inflammation in LPS-stimulated HGF cells was evaluated. The results demonstrated a decrease in the levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), and interleukin-1 β (IL-1β) after exposure to WSE. The action mechanism could be the stimulation of the Nrf2 transcription factor by the bioactive compounds present in septum, followed by the downregulation of the NF-κB pathway and inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion [12].

The anti-inflammatory effect of septum extract was also evaluated in an antitussive animal model using 3-month-old, healthy male Wistar rats [36]. The WSE treatment statistically decreased two tested inflammatory biomarkers, IL-6 and the receptor CXC-R1 for IL-8, in the lung tissue homogenates, and had no effect on the other receptor for IL-8 or CXC-R2. Another anti-inflammatory biomarker assessed in the lung tissue homogenates, NO concentration, revealed no significant changes after WSE treatment. The histopathological analysis of lung tissues at the level of alveolar parenchyma disclosed the largest area occupied by the alveolar spaces in the WSE group compared to both the control and codeine-treated groups in this citric acid aerosol-induced cough experimental model in rats [36]. The bioactive phytochemical content in septum manifesting antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities could be part of the mechanism for the positive effects.

Several other extracts of J. regia matrices, including leaves, bark, husk, and kernels, exhibited inhibition of inflammatory processes and downregulation of the production of inflammatory mediators including leukotrienes [50]. Walnut oil reduced LPS-induced neuroinflammation, a condition related to cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases, in rat microglial cells by lowering nitrite generation, as well as COX2 and iNOS expression, in a concentration- and time-dependent manner [51]

4.3. Antidiabetic Activities

The diabetic pathology relates to hyperglycemia that causes health problems associated with ROS generation, glycation of proteins, lipoperoxidation, or insulin sensitivity, resistance, and secretion. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a chronic metabolic condition more common in the adult overweight and obese population, can lead to CVD, diabetic retinopathy, kidney failure, or mental health disorders [52]. An effective preventive and therapeutic strategy against diabetes is the improvement of blood glucose homeostasis through several interventions [53,54].

One of the measures is the inhibition of the activity of α-amylase and α-glucosidase, two typical postprandial digestive enzymes. Natural bioactive compounds that could inhibit these enzymes have recently been investigated because acarbose, an effective inhibitor, can cause side effects such as gastrointestinal symptoms. The action mechanism was related to the monosaccharide composition, polysaccharide molecular weight, spatial structure, or glycosidic bonds in a microwave-assisted polysaccharide fraction extracted from the septum that inhibited α-amylase and α-glucosidase. Furthermore, the same septum extract significantly lowered blood glucose levels in male ICR mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes [29].

The α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of WSE was also investigated by Tan et al. [38]. The main bioactive compounds presenting inhibitory effects were four flavonoids, taxifolin, (+)-catechin, quercetin, and luteolin, with IC50 values in the range of 29.47–54.82 μM, stronger than the positive control acarbose (60.01 μM). Thus, the flavonoids through the structures of the A, B and C rings might be the primary molecules contributing to the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of WSE. This evidence is in agreement with another study in which catechin and three quercetin glycosides, namely quercitrin (quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside), isoquercitrin (quercetin 3-β-D-glucoside), and hyperoside (quercetin 3-D-galactoside), the bioactive molecules isolated from walnut septum, could obstruct the activity of α-glucosidase [12].

Further phytochemical analysis isolated four new taraxasterane-type triterpenes in walnut septum, compounds that could suppress α-glucosidase [39].

The antihyperglycemic activity of septum was studied in diabetic mice induced with streptozotocin. After 4 weeks, the aqueous septum extract significantly reduced blood glucose (p < 0.05), but did not affect pancreatic structure [14]. Besides decreasing blood glucose levels, the aqueous septum extract inhibited hepatic damage in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice [55].

In streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, ethanolic septum extracts also decreased their blood glucose levels, without changing the insulin levels in diabetic and non-diabetic rats, and nor the normoglycemia in healthy, non-diabetic rats [16]. The hypoglycemic effect of septum was also analyzed in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. After 28 days, the ethanol septum extract significantly decreased blood glucose (p < 0.001), triglyceride levels (p < 0.05), and attenuated the low-density lipoprotein and total cholesterol [56].

The hypoglycemic capacity of WSE was evaluated in young rats, treated with D-gal to induce aging, and in old rats. Glycemia was significantly decreased in young rats compared to the D-gal group (p < 0.01) and in old rats compared to the control (p < 0.05) [31].

In a recent in vivo study, Zhang et al. combined a high-fat diet with low-dose streptozotocin and assessed the preventive effects of septum extract and regulation of gut microbiota on diabetic rats [57]. For the first time, it was indicated that supplementing with septum extract in advance could halt the onset of T2DM and inhibit metabolic disorders by reducing insulin resistance, liver damage, aberrant lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, and inflammation. The main components found in septum that also modulated the intestinal flora in rats were phenolic acids (rugosin F isomer, gallic acid, phlorizin, p-coumaric acid, vanillic acid, quercetin), flavonoids, and quinones [57].

Besides J. regia septum, the effects on blood glucose of other matrices from this species were also evaluated. Boulfia et al. showed that macerated acetone and ethanol extracts from walnut bark inhibited the activities of alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase [58]. These effects may be due to the various polyphenolics that were reported in walnut husk, buds, and bark [59]. The hypoglycemic activity of these bioactive compounds in terms of absorption, which could be influenced by the chemical and enzymatic changes during digestion and the plant matrix, was shown to be stronger for walnut green husk compared to brown shell [60].

Preclinical and clinical studies assessed the influence of walnut leaves. Thus, in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, an extract of walnut leaves decreased fasting blood glucose and MDA levels, improved the lipid profile, and significantly increased antioxidant enzyme activity in a dose-dependent manner compared to control [61]. The results of a randomized, double-blind, clinical trial of diabetic patients receiving hydroalcoholic walnut leaf extracts disclosed that glycemia and insulin resistance conditions were not modified, but other parameters, such as body mass index and systolic blood pressure, significantly decreased compared to baseline [62].

4.4. Antimicrobial Properties

Many bioactive molecules are known for their immunostimulant and antimicrobial activities [63]. Recent reports ascribed the antimicrobial inhibitory potential of J. regia to its rich and diverse phytochemical content [64]. Vieira et al. reported that the hydroethanolic extract of walnut green husk displayed good antimicrobial activities against Gram-positive and some Gram-negative bacteria, with the exception of Pseudomonas aeruginosa [65]. However, another study revealed that walnut extract, in a dose-dependent manner, could present activity against biofilm-related infections caused by this microorganism [66]. The macerated acetone extract from walnut bark presented antimicrobial capacity against Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Proteus mirabilis, P. aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Listeria innocua [58], while the walnut pellicle extract displayed antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities in a dose-dependent manner [67].

The antimicrobial properties of the walnut extracts could be related to the polar part compounds, such as phenolic acids, and to the non-polar part compounds including tocopherols, sterols, monoterpenes, and juglone [68]. The inhibition of microbial activity was also related to vegetative phases [69].

Several experiments exposed that microbial strains have different sensibilities to septum extract. For example, walnut septum hydroalcohol extract incorporated in traditional butter presented good antimicrobial activity and inhibited the growth of the microorganisms (Coliforms, Psychrotrophic bacteria, yeasts, and molds) used in the study, excepting S. aureus [28].

The results of Genovese et al. showed that Gram-positive compared to Gram-negative bacteria were more sensitive to the WSE action, perhaps due to the wall structure and composition of bacteria [30]. Similar to these findings, another study showed that WSE presented strong antibacterial activity against S. aureus and a low effect against Gram-negative E. coli [12]. However, the extract was active against the other Gram-negative bacteria (P. aeruginosa and Salmonella enteritidis) and had no effect on the two fungi (Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis). The results of a new study confirmed that WSE inhibited Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus and B. subtilis) and again did not affect E. coli [70].

Besides phenolic compounds, Meng et al. highlighted that polysaccharides from septum, in a concentration-dependent manner, could also present antibacterial activity by disrupting the permeability of the cell wall and membrane of bacteria and inhibiting their growth [21]. Other studies also proved that the types of the extraction methods could influence the phytochemical profile of septum extracts and their biological effects [33].

4.5. Enzyme Inhibitory Activities

Tyrosinase is a copper-containing enzyme that controls the production of melanin. Thus, decreasing tyrosinase activity can prevent conditions related to the hyperpigmentation of the skin including melasma and age spots [71]. A hydroacetone septum extract revealed good tyrosinase inhibitory activity [24]. Previous studies reported that kernel and bark walnut extracts exhibited strong tyrosinase inhibition effects [50,72].

Among the therapies against obesity, a leading health issue linked to many cardiometabolic diseases is the inhibition of pancreatic lipase, an important enzyme involved in the hydrolysis of dietary fats. The inhibition of this enzyme may reduce overweight and obesity and regulate hyperglycemia [73]. One study analyzed the inhibitory capacity of septum extract [12]. It revealed an inhibition capacity of 50.79%, which was lower than those of walnut, pistachio, and pecan at 57, 68, and 69%, respectively [74].

The cholinergic system was proposed to be the most affected in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Therefore, one potential therapeutic strategy in these conditions is to increase the brain cholinergic levels by inhibiting the activities of AChE and butylcholinesterase (BuChE) [75].

Although some plant methanolic extracts including Citrus limon, Ocimum basilicum, and Mentha spicata displayed concentration-dependent inhibition of AChE and BuChE [76], WSE revealed no AChE inhibitory potential [12]. However, a recent study demonstrated that treatment with walnut hull extract could preserve antioxidant activity and significantly lower the cortical architectural damage in isoprenaline-induced pathological damage in rat brain tissue [77].

4.6. Antitumor Properties

In the past few decades, as the average life expectancy increased substantially, the prevalence of many chronic age-related diseases, including cancer, also increased [78]. Scientific evidence demonstrated that engaging in a healthier lifestyle or employing innovative curative treatments were key preventive and therapeutic strategies against these disorders [79]. Several studies revealed the beneficial effects of nut intake in lowering all-cause mortality and decreasing cancer incidence and mortality [80,81]. Walnut consumption in particular reduced the growth and survival of cancer cells via modifying the expression of cancer genes in mice and humans [82]. In addition, green walnut husk extracts inhibited the survival, migration, and invasion of gastric cancer cells in vivo and induced apoptosis, while in vitro they reduced cancer cell growth [57]. Juglone and its derivatives, found in most walnut matrices, play significant roles in cancer cell apoptosis, induction of autophagy, inhibition of cancer cell migration and proliferation [83].

Polysaccharides in the septum extract also showed antitumor activity, suppressing the proliferation of the human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (HepG2) and gastric carcinoma cell line (BGC-823) in a dose-dependent manner (8–500 μg/mL) [23]. In a recent study, the antiproliferative activity of septum aqueous decoction was manifested not only against cancerous cells but also against normal mesenchymal stem cells, thus, further investigations are warranted [33].

Meanwhile, Genovese et al., investigating the cytostatic and cytotoxic effects of walnut septum extract on the human A172 glioblastoma cell line, showed that only the highest dose of the extract (140 μg/mL at 24 and 48 h) reduced the viability of non-cancerous human foreskin fibroblast (HFF-1) cells [30]. Yet, a reduction in the viability of cancerous cells was noted in a dose-dependent manner, from 35 to 140 μg/mL, with a significant reduction being observed at a WSE concentration of 70 μg/mL. Further cytostatic activity evaluation demonstrated a reduced ability of treated cancerous cells to proliferate and migrate. Moreover, after 48 h of the WSE treatment, caspase-3 activity showed a significant increase, which resulted in cancerous cell apoptosis. The septum phytochemical analysis disclosed several bioactive compounds that could be responsible for the antitumor activity including p-coumaric acid hexoside, quercetin 3-O-glucoside, and quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside (quercitrin), which are all predicted to be pro-apoptotic agents through caspase-3 expression stimulation, as well as epigallocathechin and epigallocathechin gallate, two flavonoids expected to promote apoptosis [30]. In addition to these molecules, other bioactive compounds found in plants were associated with a lower risk of cancer [84].

A recent in vitro experiment analyzed the WSE cytotoxicity on three cancerous cell lines (human lung adenocarcinoma cell A549 and breast cancer cells T47D-KBluc and MCF-7) and one normal cell line (human gingival fibroblasts HGF) [12]. Significant cytotoxic activity was observed in A549 and T47D-KBluc after 48 h of WSE treatment in a dose-dependent manner at concentrations greater than 75 g/mL. However, the MCF-7 line was not affected by the extract, while the normal cell line was more resilient to the WSE cytotoxic activity. The flow cytometry assay confirmed that the WSE treatment induced dose-dependent cytotoxicity in the evaluated cell lines, with the process involved proving to be mainly necrosis while apoptosis had a minor contribution [12].

Some of the anti-cancer mechanisms initiated by bioactive molecules include the regulation of signaling pathways in cancer cells, such as p53, NF-κB, MAPK, and PI3K/AKT, as well as the control of the activity of oncogenic and tumor suppressor ncRNAs [85,86]. Many dietary polyphenols present in septum extracts can positively modulate some of these mechanisms. Moreover, some of them, including rutin, quercetin, myricetin, and ellagic acid, can inhibit glucose uptake in some cancerous cells, such as Caco-2 cells, thus, being able to arrest cancer advancement [87].

4.7. Antitussive Effect

In a recent study, the antitussive potential of an optimized WSE was investigated in a citric acid-induced cough model by exposing Wistar rats to citric acid aerosols (17.5%) [36]. In the WSE treated-animals at a dose of 134 mg GAE/kg bw/day, the number of coughs decreased by approximately 68% versus negative control, a comparable effect to codeine. In addition, the WSE treatment significantly increased the latency of coughs and lowered pulmonary inflammation by reducing ROS and oxidative stress. Similarly, other plant extracts revealed antitussive, expectorant, and anti-inflammatory properties in rodent models [88]. Higher antitussive or expectorant effects were observed for Thymus spp., Tilia spp., Nigella sativa, Linum usitatissimum, or Artemisia absinthium [89]. As mentioned before, phytochemicals from walnut septum could act as antioxidants and antitussive agents. Hence, quercetin and its glycosides were reported to possess antioxidant potential and health benefits in age-related diseases [90,91]. Naringenin and its suspensions improved the antitussive and expectorant outcomes, and decreased cough frequency [92]. Other phenolic acids and flavonoids could also be potential treatments against asthma and chronic bronchitis [93].

4.8. Myelopoiesis Activation

Several medical procedures, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, are followed by negative side effects including leukopenia and reduced immune system function. Likewise, cyclophosphamide is linked to leukopenia, cytotoxicity, and immunosuppressive effects in a dose-dependent manner. In mice, after receiving a single injection of cyclophosphamide, the number of leukocytes significantly decreased. However, the treatment with aqueous septum extract stimulated the division, differentiation, and maturation of myeloblasts and lymphoblasts, thus showing an immune correction capacity through myelopoiesis activation [17]. Moreover, sorption capacity of erythrocytes increased in the blood of experimental mice that received septum and cyclophosphamide treatment compared to mice on cyclophosphamide only. The mechanism could be that the glutathione-dependent system, one of the key erythrocyte antioxidant systems, known for binding and detoxifying cyclophosphamide metabolites, might be activated by the bioactive compounds in septum. Experimental results also exposed that septum extract had a preventive outcome on erythrocyte hemolysis [13].

4.9. Anti-Aging Potential

Aging, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation are considered major risk factors for most chronic disorders and age-related diseases. Oxidative stress and inflammation significantly impact aging, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer [94]. Recent findings emphasized the potential of nutrition, i.e., the intake of bioactive antioxidant compounds, in preventing these conditions and extending health into aging [95]. For example, the consumption of walnuts was shown to decrease the levels of ROS and inflammatory cytokines, modulate the Nrf2/EpRE, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, and NF-κB signaling pathways, prevent mitochondrial dysfunction, inhibit carcinogenesis, and regulate energy homeostasis [81]. Thus, walnut intake could improve and extend the health span and lifespan. Many bioactive compounds in walnuts are responsible for these beneficial effects. Moreover, in vivo studies on animal aging models that were mentioned (Table 6) and discussed above demonstrated the anti-aging time-dependent exposure potential of WSE administered repeatedly [31]. With the knowledge that the phytochemical profiles of different J. regia matrices are almost identical, we can extrapolate that the biological activities noticed in this review after septum extract treatment, identified walnut septum as a potential candidate of healthy aging.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review surveyed the published studies on walnut septum, one of the Juglans regia by-products, known and used in folk medicine for its medicinal properties.

Recent investigations described the phytochemical composition of this plant matrix and revealed a diverse and rich profile including polyphenols, among them phenolic acids, flavonoids, tannins, lignans, as well as carbohydrate and lipidic constituents. Other identified molecules were glutamate, histidine, and lysine, from amino acids, and potassium, calcium, and magnesium amid the minerals. Various in vitro and in vivo experiments highlighted the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of walnut septum extracts. Besides, some bioactive compounds were shown to control α-amylase and α-glucosidase, postprandial digestive enzymes, or lower glycemia in rodent model studies, demonstrating a significant preventive role in diabetes. Furthermore, p-coumaric acid hexoside, quercetin 3-O-glucoside, quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside, epigallocathechin, and epigallocathechin gallate promoted apoptosis via activating caspase-3 expression, while quercetin, rutin, myricetin, and ellagic acid inhibited glucose uptake in cancerous cells and slowed cancer progression. Other experimental outcomes exposed the antimicrobial effects, AChE and tyrosinase inhibition properties, antitussive potential, or immune correction capacity through myelopoiesis activation. Thus, walnut septum, through lowering oxidative stress, inhibiting inflammation, and modulating several important signaling pathways, could have anti-aging potential and play a role in healthy aging, a key attribute of lifespan.

We consider walnut septum to be an important biological matrix, a rich natural source of bioactive compounds that deserves to be investigated in the future in order to be fully exploited in the food, cosmetic, or pharmaceutical industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.R., L.M. and D.-S.P.; methodology, L.M.; investigation, L.M., M.E.R. and D.-S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M., M.E.R. and D.-S.P.; writing—reviewing, and editing, L.M., M.E.R. and D.-S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Salem, M.A.; Aborehab, N.M.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A.; Fernie, A.R.; Alseekh, S.; Ezzat, S.M. Potential Valorization of Edible Nuts By-Products: Exploring the Immune-Modulatory and Antioxidants Effects of Selected Nut Shells Extracts in Relation to Their Metabolic Profiles. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, J.L.; Lloyd, B. Health Benefits of Fruits and Vegetables. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Tessier, A.-J.; Petersen, K.S.; Sapp, P.A.; Tapsell, L.C.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Ros, E.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Effects of Nut Consumption on Blood Lipids and Lipoproteins: A Comprehensive Literature Update. Nutrients 2023, 15, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for the Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, S.K.; Viguiliouk, E.; Kendall, C.W.C.; Jenkins, D.J.A.; Hu, F.B.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Atzeni, A.; Misra, A.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Nuts in the Prevention and Management of Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2023, 15, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanban-Esfahlan, A.; Ostadrahimi, A.; Tabibiazar, M.; Amarowicz, R. A Comparative Review on the Extraction, Antioxidant Content and Antioxidant Potential of Different Parts of Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Fruit and Tree. Molecules 2019, 24, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Ning, D.; Ma, T.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. Comprehensive Analysis of the Components of Walnut Kernel (Juglans regia L.) in China. J. Food Qual. 2021, 2021, 9302181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.L.; Labuckas, D.O.; Lamarque, A.L.; Maestri, D.M. Walnut (Juglans regia L.): Genetic Resources, Chemistry, by-Products. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 1959–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xiao, X.; Li, J.; Wang, F.; Mi, J.; Shi, Y.; He, F.; Chen, L.; Zhang, F.; Wan, X. Chemical Compositions of Walnut (Juglans spp.) Oil: Combined Effects of Genetic and Climatic Factors. Forests 2022, 13, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Barros, L.; Calhelha, R.C.; Dueñas, M.; Carvalho, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Leaves and Decoction of Juglans regia L.: Different Performances Regarding Bioactive Compounds and In Vitro Antioxidant and Antitumor Effects. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 51, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, F.; Carpena, M.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Taofiq, O.; Otero, P.; Cao, H.; Xiao, J.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M.A. By-Products of Walnut (Juglans regia) as a Source of Bioactive Compounds for the Formulation of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2022, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, M.E.; Fizesan, I.; Pop, A.; Mocan, A.; Gheldiu, A.M.; Babota, M.; Vodnar, D.C.; Jurj, A.; Berindan-Neagoe, I.; Vlase, L.; et al. Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Septum: Assessment of Bioactive Molecules and In Vitro Biological Effects. Molecules 2020, 25, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramishvili, L.; Gordeziani, M.; Tavdishvili, E.; Bedineishvili, N.; Dzidziguri, D.; Kotrikadze, N. The Effect of Extract of Greek Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Septa on Some Function Characteristics of Erytrocytes. Georgian Med. News 2016, 261, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani, F.; Mashhoody, T.; Panjehshahin, M. Effect of Aqueous Extract of Walnut Septum on Blood Glucose and Pancreatic Structure in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Mouse. Iran. J. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 11, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajikhani, R.; Solati, J. Effects of Walnut Alcoholic Extract (Juglans regia L.) Septum on Serum Glucose, Insulin and Activities of Aminotransferase Enzymes. J. Appl. Chem. Res. 2010, 12, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dzidziguri, D.; Rukhadze, M.; Modebadze, I.; Bakuradze, E.; Kurtanidze, M.; Giqoshvili, V. The Study of the Immune Corrective Properties of Greek Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Septa on the Experimental Model of Leukopenia. Georgian Med. News 2016, 252, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiravani, Z.; Hosseini, M.; Hassanzadeh Taheri, M.M.; Reza Abedini, M. Evaluation of Hypoglycemic and Hypolipidemic Effects of Internal Septum of Walnut Fruit in Alloxan-Induced Diabetic Rats. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 13, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanbakhsh, A.; Mahdavi, M.; Jalilzade-Amin, G.; Javadi, S.; Maham, M.; Mohammadnejad, D.; Rashidi, M.R. Acute and Subchronic Toxicity Study of the Median Septum of Juglans regia in Wistar Rats. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 6, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Bai, H.; Jing, Y.; Li, W.; Yin, S.; Zhou, H. A Pair of Taxifolin-3-O-Arabinofuranoside Isomers from Juglans regia L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Li, Y.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, L.; Xu, D. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Polysaccharides Isolated and Purified from Diaphragma juglandis Fructus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Mu, Y.; Dong, H.; Yan, H.; Hao, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Chemical Constituents of the Ethyl Acetate Extract from Diaphragma juglandis Fructus and Their Inhibitory Activity on Nitric Oxide Production In Vitro. Molecules 2018, 23, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, F.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, L. Polysaccharides from Diaphragma Juglandis Fructus: Extraction Optimization, Antitumor, and Immune-Enhancement Effects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 115, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, M.E.; Gheldiu, A.M.; Mocan, A.; Moldovan, C.; Popa, D.S.; Tomuta, I.; Vlase, L. Process Optimization for Improved Phenolic Compounds Recovery from Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Septum: Phytochemical Profile and Biological Activities. Molecules 2018, 23, 2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Dong, N.; Geng, Y.-Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y. Phenolic Composition and Nutritional Attributes of Diaphragma Juglandis Fructus and Shell of Walnut (Juglans regia L.). Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Li, L.; Song, L.; Sun, X.; Yan, S.; Huang, W. Characterisation of Phenolics in Fruit Septum of Juglans regia Linn. by Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer. Food Chem. 2019, 286, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhao, Z.; Dai, S.; Che, X.; Liu, W. Identification and Quantification of Bioactive Compounds in Diaphragma juglandis Fructus by UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS and UHPLC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 3811–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, T.; Mohammadipour, N.; Langroodi, A.M.; Raeisi, M. Effect of Walnut Kernel Septum Membranes Hydroalcoholic Extract on the Shelf Life of Traditional Butter. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Chen, F.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, L. Inhibitory Effects of Polysaccharide from Diaphragma juglandis Fructus on α-Amylase and α-D-Glucosidase Activity, Streptozotocin-Induced Hyperglycemia Model, Advanced Glycation End-Products Formation, and H2O2-Induced Oxidative Damage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 124, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, C.; Cambria, M.T.; D’Angeli, F.; Addamo, A.P.; Malfa, G.A.; Siracusa, L.; Pulvirenti, L.; Anfuso, C.D.; Lupo, G.; Salmeri, M. The Double Effect of Walnut Septum Extract (Juglans regia L.) Counteracts A172 Glioblastoma Cell Survival and Bacterial Growth. Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 57, 1129–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, M.E.; Georgiu, C.; Pop, A.; Mocan, A.; Kiss, B.; Vostinaru, O.; Fizesan, I.; Stefan, M.G.; Gheldiu, A.M.; Mates, L.; et al. Antioxidant Effects of Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Kernel and Walnut Septum Extract in a D-Galactose-Induced Aging Model and in Naturally Aged Rats. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Kan, H.; Chen, S.X.; Thakur, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.G.; Shang, Y.F.; Wei, Z.J. Comparison of Phenolic Compounds Extracted from Diaphragma Juglandis Fructus, Walnut Pellicle, and Flowers of Juglans regia Using Methanol, Ultrasonic Wave, and Enzyme Assisted-Extraction. Food Chem. 2020, 321, 126672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghapour, S.K.F.; Sisakhtnezhad, S. Effect of the Internal Septum Extract of the Walnut Kernel on the Mesenchymal Stem Cells Cycle and MSCs-Derived Insulin-Producing Β-Cells Differentiation and Glucose Uptake. Jentashapir J. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2021, 12, e115014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Geng, S.; Ji, J.; Ye, Y.; Xu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. Separation and Identification of Antioxidant Chemical Components in Diaphragma juglandis Fructus and Functional Evaluation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 80, 104422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Gao, S.; Mou, D. Water and Alcohol Extracts from Diaphragma juglandis on Anti-Fatigue and Antioxidative Effects in Vitro and Vivo. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 3132–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fizeșan, I.; Rusu, M.E.; Georgiu, C.; Pop, A.; Ștefan, M.G.; Muntean, D.M.; Mirel, S.; Vostinaru, O.; Kiss, B.; Popa, D.S. Antitussive, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of a Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Septum Extract Rich in Bioactive Compounds. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalogiouri, N.P.; Samanidou, V.F. A Validated Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Coupled with Spe-Hplc-Dad for the Determination of Flavonoids in by-Products of Plant Origin: An Application Study for the Valorization of the Walnut Septum Membrane. Molecules 2021, 26, 6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Ren, H.; Qiao, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y. The Chemical Constituents of Diaphragma Juglandis Fructus and Their Inhibitory Effect on α-Glucosidase Activity. Molecules 2022, 27, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.Y.; Cheng, Y.G.; Li, J.L.; Ren, H.Q.; Li, H.; Huang, Y.R.; Qiao, Y.B.; Li, Q.S.; Wang, Y.L. New Taraxasterane-Type Triterpenes from Diaphragma juglandis Fructus. Tetrahedron Lett. 2022, 100, 153868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, Q.; Gao, Y.; Yu, X. Utilization of Diaphragma Juglandis Extract as a Natural Antioxidant for Improving the Oxidative Stability of Soybean Oil during Deep Frying. Food Chem. X 2022, 14, 100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Sayed, A.M.; Elmaidomy, A.H. Natural Products’ Extraction and Isolation-between Conventional and Modern Techniques. Front. Nat. Prod. 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An Overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand David, A.V.; Arulmoli, R.; Parasuraman, S. Overviews of Biological Importance of Quercetin: A Bioactive Flavonoid. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2016, 10, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schädel, C.; Blöchl, A.; Richter, A.; Hoch, G. Quantification and Monosaccharide Composition of Hemicelluloses from Different Plant Functional Types. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, E.C.; Vousden, K.H. The Role of ROS in Tumour Development and Progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Almeida, A.J.P.O.; de Oliveira, J.C.P.L.; da Silva Pontes, L.V.; de Souza Júnior, J.F.; Gonçalves, T.A.F.; Dantas, S.H.; de Almeida Feitosa, M.S.; Silva, A.O.; de Medeiros, I.A. ROS: Basic Concepts, Sources, Cellular Signaling, and Its Implications in Aging Pathways. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 1225578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, I.G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical Methods Used in Determining Antioxidant Activity: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banc, R.; Rusu, M.E.; Filip, L.; Popa, D.-S. The Impact of Ellagitannins and Their Metabolites through Gut Microbiome on the Gut Health and Brain Wellness within the Gut–Brain Axis. Foods 2023, 12, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merly, L.; Smith, S.L. Murine RAW 264.7 Cell Line as an Immune Target: Are We Missing Something? Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2017, 39, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourais, I.; Elmarrkechy, S.; Taha, D.; Badaoui, B.; Mourabit, Y.; Salhi, N.; Alshahrani, M.M.; al Awadh, A.A.; Bouyahya, A.; Goh, K.W.; et al. Comparative Investigation of Chemical Constituents of Kernels, Leaves, Husk, and Bark of Juglans regia L., Using HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS Analysis and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Molecules 2022, 27, 8989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.; Cahoon, D.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Walnut Oil and Blueberry Treatments Have Beneficial Individual but Not Synergistic Effects on Neuroinflammation In Vitro. Am. Soc. Nutr. 2021, 5, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J.; Aroda, V.R.; Collins, B.S.; Gabbay, R.A.; Green, J.; Maruthur, N.M.; Rosas, S.E.; del Prato, S.; Mathieu, C.; Mingrone, G.; et al. Management of Hyperglycaemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2022. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia 2022, 65, 1925–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landgraf, R.; Aberle, J.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Gallwitz, B.; Kellerer, M.; Klein, H.; Müller-Wieland, D.; Nauck, M.A.; Reuter, H.M.; Siegel, E. Therapy of Type 2 Diabetes. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2019, 127, S73–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akpoveso, O.-O.P.; Ubah, E.E.; Obasanmi, G. Antioxidant Phytochemicals as Potential Therapy for Diabetic Complications. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangeneh, A.; Zangeneh, M.M.; Goodarzi, N.; Najafi, F.; Hagh Nazari, L. Protective Effects of Aqueous Extract of Internal Septum of Walnut Fruit on Diabetic Hepatopathy in Streptozocin-Induced Diabetic Mice. Sci. J. Kurd. Univ. Med. Sci. 2018, 93, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiravani, Z.; Hassanzadeh-Taheri, M.; Hassanzadeh-Taheri, M.; Hosseini, M. Internal Septum of Walnut Kernel: A Neglected Functional Food. Res. J. Pharmacogn. (RJP) 2020, 7, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, C.; Sui, H.; Feng Li, C.; Zhong, L.; Zhou, Q.; Bai, Y.; An, S.; Du, X.; et al. Green Walnut Husk Extracts Proliferation and Migration in Gastric Cancer. J. Cancer 2022, 13, 1130–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulfia, M.; Lamchouri, F.; Toufik, H. Mineral Analysis, in Vitro Evaluation of Alpha-Amylase, Alpha-Glucosidase, and Beta-Galactosidase Inhibition, and Antibacterial Activities of Juglans regia L. Bark Extracts. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 1585692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, A.; Jakopic, J.; Solar, A.; Hudina, M.; Veberic, R. Walnut (J. regia) Agro-Residues as a Rich Source of Phenolic Compounds. Biology 2021, 10, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, S.; Zeng, F.; Qi, J.; Qin, W.; Tan, C.; Luo, Q.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, D.; et al. Functional Components, Antioxidant Activity and Hypoglycemic Ability Following Simulated Gastro-Intestinal Digestion of Pigments from Walnut Brown Shell and Green Husk. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelodar, G.; Mohammadi, M.; Akbari, A.; Nazifi, S. Cyclohexane Extract of Walnut Leaves Improves Indices of Oxidative Stress, Total Homocysteine and Lipids Profiles in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Physiol. Rep. 2020, 8, e14348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiei, K.; Ebrahimzadeh, M.A.; Saeedi, M.; Bahar, A.; Akha, O.; Kashi, Z. Effects of a Hydroalcoholic Extract of Juglans regia (Walnut) Leaves on Blood Glucose and Major Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Type 2 Diabetic Patients: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedeanu, N.; Voica, C.; Magdas, D.A.; Kiss, B.; Stefan, M.G.; Simedrea, R.; Georgiu, C.; Berce, C.; Vostinaru, O.; Boros, R.; et al. Subacute Co-Exposure to Low Doses of Ruthenium(III) Changes the Distribution, Excretion and Biological Effects of Silver Ions in Rats. Environ. Chem. 2020, 17, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, M.E.; Simedrea, R.; Gheldiu, A.M.; Mocan, A.; Vlase, L.; Popa, D.S.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Benefits of Tree Nut Consumption on Aging and Age-Related Diseases: Mechanisms of Actions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, V.; Pereira, C.; Abreu, R.M.V.; Calhelha, R.C.; Alves, M.J.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Ferreira, O.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Hydroethanolic Extract of Juglans regia L. Green Husks: A Source of Bioactive Phytochemicals. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 137, 111189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolatabadi, S.; Moghadam, H.N.; Mahdavi-Ourtakand, M. Evaluating the Anti-Biofilm and Antibacterial Effects of Juglans regia L. Extracts against Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 118, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquaviva, R.; D’Angeli, F.; Malfa, G.A.; Ronsisvalle, S.; Garozzo, A.; Stivala, A.; Ragusa, S.; Nicolosi, D.; Salmeri, M.; Genovese, C. Antibacterial and Anti-Biofilm Activities of Walnut Pellicle Extract (Juglans regia L.) against Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 2076–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barekat, S.; Nasirpour, A.; Keramat, J.; Dinari, M.; Meziane-Kaci, M.; Paris, C.; Desobry, S. Phytochemical Composition, Antimicrobial, Anticancer Properties, and Antioxidant Potential of Green Husk from Several Walnut Varieties (Juglans regia L.). Antioxidants 2022, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Madrid, D.; Gutiérrez-Cutiño, M.; Pozo-Martínez, J.; Zúñiga-López, M.C.; Olea-Azar, C.; Matiacevich, S. Dependence of the Ripeness Stage on the Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Green Husk Extracts from Industrial by-Products. Molecules 2021, 26, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delibaş, E.A.Ö.; Kiray, E. Investigation of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Kernel Septum. Eur. Res. J. 2022, 9, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, D.; Cardinali, G.; Picardo, M.; Bastonini, E. Shining Light on Autophagy in Skin Pigmentation and Pigmentary Disorders. Cells 2022, 11, 2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besrour, N.; Oludemi, T.; Mandim, F.; Pereira, C.; Dias, M.I.; Soković, M.; Stojković, D.; Ferreira, O.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Barros, L. Article Valorization of Juglans regia Leaves as Cosmeceutical Ingredients: Bioactivity Evaluation and Final Formulation Development. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Keogh, J.; Clifton, P.M. Nuts and Cardio-Metabolic Disease: A Review of Meta-Analyses. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojdyło, A.; Turkiewicz, I.P.; Tkacz, K.; Nowicka, P.; Bobak, Ł. Nuts as Functional Foods: Variation of Nutritional and Phytochemical Profiles and Their In Vitro Bioactive Properties. Food Chem. X 2022, 15, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzimski, T.; Petruczynik, A. Determination of Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease Activity of Selected Plant Ingredients. Molecules 2022, 27, 3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amat-Ur-rasool, H.; Symes, F.; Tooth, D.; Schaffert, L.N.; Elmorsy, E.; Ahmed, M.; Hasnain, S.; Carter, W.G. Potential Nutraceutical Properties of Leaves from Several Commonly Cultivated Plants. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Verma, P.K.; Sood, S.; Pankaj, N.K.; Agarwal, S.; Raina, R. Neuroprotective Potential of Hydroethanolic Hull Extract of Juglans regia L. on Isoprenaline Induced Oxidative Damage in Brain of Wistar Rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Schoufour, J.; Wang, D.D.; Dhana, K.; Pan, A.; Liu, X.; Song, M.; Liu, G.; Shin, H.J.; Sun, Q.; et al. Healthy Lifestyle and Life Expectancy Free of Cancer, Cardiovascular Disease, and Type 2 Diabetes: Prospective Cohort Study. BMJ 2020, 368, l6669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, M.E.; Fizeșan, I.; Vlase, L.; Popa, D.S. Antioxidants in Age-Related Diseases and Anti-Aging Strategies. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, E.; Singh, A.; O’keefe, J.H. Nuts: Natural Pleiotropic Nutraceuticals. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, M.E.; Mocan, A.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Popa, D.S. Health Benefits of Nut Consumption in Middle-Aged and Elderly Population. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardman, W.E.; Primerano, D.A.; Legenza, M.T.; Morgan, J.; Fan, J.; Denvir, J. Dietary Walnut Altered Gene Expressions Related to Tumor Growth, Survival, and Metastasis in Breast Cancer Patients: A Pilot Clinical Trial. Nutr. Res. 2019, 66, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.T.; Li, Y.; Chu, P.; Ma, D.X.; Tang, Z.Y.; Sun, L.Z. Molecular Biological Mechanism of Action in Cancer Therapies: Juglone and Its Derivates, the Future of Development. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 148, 112785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocetto, F.; di Zazzo, E.; Buonerba, C.; Aveta, A.; Pandolfo, S.D.; Barone, B.; Trama, F.; Caputo, V.F.; Scafuri, L.; Ferro, M.; et al. Kaempferol, Myricetin and Fisetin in Prostate and Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgharian, P.; Tazekand, A.P.; Hosseini, K.; Forouhandeh, H.; Ghasemnejad, T.; Ranjbar, M.; Hasan, M.; Kumar, M.; Beirami, S.M.; Tarhriz, V.; et al. Potential Mechanisms of Quercetin in Cancer Prevention: Focus on Cellular and Molecular Targets. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrânceanu, M.; Galimberti, D.; Banc, R.; Dragoş, O.; Cozma-Petruţ, A.; Hegheş, S.C.; Voştinaru, O.; Cuciureanu, M.; Stroia, C.M.; Miere, D.; et al. The Anticancer Potential of Plant-Derived Nutraceuticals via the Modulation of Gene Expression. Plants 2022, 11, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angeli, F.; Malfa, G.A.; Garozzo, A.; Volti, G.L.; Genovese, C.; Stivala, A.; Nicolosi, D.; Attanasio, F.; Bellia, F.; Ronsisvalle, S.; et al. Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Cytotoxic Activities of Juglans regia L. Pellicle Extract. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.R.; Jung, C.J.; Ku, S.M.; Jung, D.H.; Bashir, K.M.I.; Ku, S.K.; Choi, J.S. Anti-Inflammatory, Expectorant, and Antitussive Properties of Kyeongok-Go in ICR Mice. Pharm. Biol. 2021, 59, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottoni, M.; Milani, F.; Colombo, L.; Nallio, K.; Colombo, P.S.; Giuliani, C.; Bruschi, P.; Fico, G. Using Medicinal Plants in Valmalenco (Italian Alps): From Tradition to Scientific Approaches. Molecules 2020, 25, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakyriakopoulou, P.; Velidakis, N.; Khattab, E.; Valsami, G.; Korakianitis, I.; Kadoglou, N.P.E. Potential Pharmaceutical Applications of Quercetin in Cardiovascular Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, P.K. Health Benefits of Quercetin in Age-Related Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, M.; Meng, Z.; Wang, X.; Han, M.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X. Preparation of Naringenin Nanosuspension and Its Antitussive and Expectorant Effects. Molecules 2022, 27, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafian, Y.; Hamedi, S.S.; Kaboli Farshchi, M.; Feyzabadi, Z. Plantago Major in Traditional Persian Medicine and Modern Phytotherapy: A Narrative Review. Electron Phys. 2018, 10, 6390–6399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, S.; Frenis, K.; Oelze, M.; Kalinovic, S.; Kuntic, M.; Jimenez, M.T.B.; Vujacic-Mirski, K.; Helmstädter, J.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Münzel, T.; et al. Vascular Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: Major Triggers for Cardiovascular Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 7092151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, V.D.; Anderson, R.M. Nutrition, Longevity and Disease: From Molecular Mechanisms to Interventions. Cell 2022, 185, 1455–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).