Abstract

Plants from the eudicot Celastraceae family are primarily cultivated for ornamental use due to their colourful autumn foliage, and, as such, their chemical composition is rarely investigated. In total, 125 samples from, altogether, 40 shrub, vine and tree species (Catha, Celastrus, Euonymus, Gymnosporia, Maytenus, Parnassia, and Tripterygium) were investigated to confirm tocotrienol dominance in the family, which was observed in the initial screenings. The tocochromanol–tocopherol (T) and tocotrienol (T3) contents ranged from 3.04 to 66.22 mg 100 g−1 dw. Almost all the samples were tocotrienol-dominated (50.1–98.5% of total tocochromanols), except for Parnassia. The two most prevalent compounds were γ-T3 and α-T3. Most Euonymus species’ seeds contained primarily α-T3 (16.2–86.0% of total tocochromanols) and tocopherol (up to 35.0%), while the other species had higher γ-T3 (36.0–87.2%) and tocopherol (up to 29.9%) contents, except the Parnassia samples, which contained primarily γ-T and δ-T. The highest total tocochromanol content was observed in E. scandens, but it was highly variable. The content of α-T3 was less variable than γ-T3 (coefficients of variation of 0.74 and 1.46, respectively). This study shows that tocotrienols are predominant in the Celastraceae family. A streamlined ethanolic extraction protocol was evaluated and deemed suitable for routine screening and, potentially, bioactive extraction.

1. Introduction

Celastraceae (staff vine) is a dicotyledonous plant family in the Celastrales order that includes 98 genera [1] and 1350 species [2] of shrubs, trees and vines. Most of the species are tropical, and many are endemic to specific areas and often endangered, largely due to habitat loss. In temperate climates, only Celastrus (staff vine, staff tree, and bittersweet), Euonymus (spindle tree, burning-bush, and strawberry bush), and Maytenus (Mayten tree) are common, while small flowering plants from the Parnassia (bog-star) genus grow in alpine and arctic climates.

Plants of the Celastraceae family are largely cultivated for ornamental purposes, as the aril and fruit of some genera turn a vivid colour in autumn, although some are used in traditional medicines [3] or for recreational purposes [4]. One plant with a long-standing role in Traditional Chinese Medicine is Tripterygium wilfordii, primarily employed for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. In general, the genus Tripterygium is chemically distinguished by the production of a diverse array of terpenoids, most notably diterpenoids, sesquiterpenoids, and triterpenoids. Among these metabolites, triptolide, a labdane-type diterpenoid, has been identified as a key bioactive compound exhibiting strong anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, and antitumor activities, and it has been increasingly recognised for its potential therapeutic relevance in central nervous system disorders such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease [5]. Plants of the Celastraceae family are not widely used for food and are often toxic to humans. It is, therefore, not surprising that there are few investigations on the lipid composition of the species. Some studies have been conducted on the fatty acid composition of Catha edulis [6], Celastrus orbiculatus [7], Celastrus paniculatus [8,9], various Euonymus species [10,11,12,13], Gymnosporia montana [14], and Maytenus boaria [15]. However, minor fixed oil lipids are rarely investigated, and research is mainly focused on terpenoids. Tocochromanols–tocopherols (Ts) and tocotrienols (T3s) have not been properly investigated in the Celastraceae family. There is only one investigation describing the presence of tocopherols in Celastraceae, which found γ-T dominance, followed by α-T, in Celastrus paniculatus [8]. However, the study did not use tocotrienol standards, nor did it provide chromatograms that would allow for a closer inspection of the tocochromanol profile. Consequently, it remains unclear whether tocotrienols are genuinely absent in this species or whether they have not been detected because suitable reference standards are not available. In another report, the role of geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase 8 was investigated in T. wilfordii diterpenoid biosynthesis. While geranylgeranyl diphosphate is a crucial precursor for synthesizing the skeleton structures of diterpenoids, it is also used as the tocotrienol lipophilic tail and is a precursor to the tocopherol lipophilic tail [5]. In light of the above, it would be highly valuable to carry out a broader survey of multiple species within the Celastraceae family to assess whether tocotrienols consistently predominate over tocopherols in their seeds.

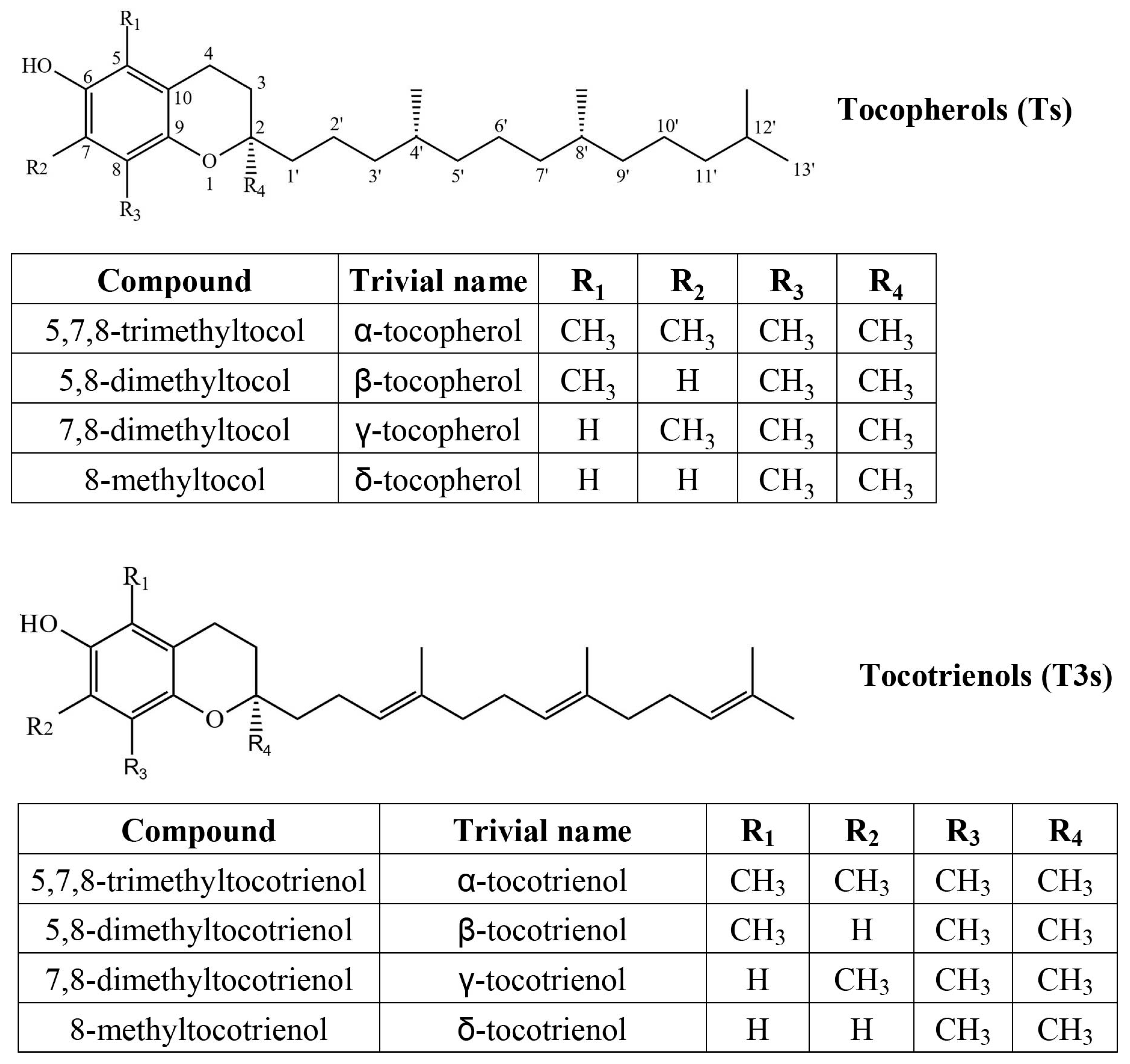

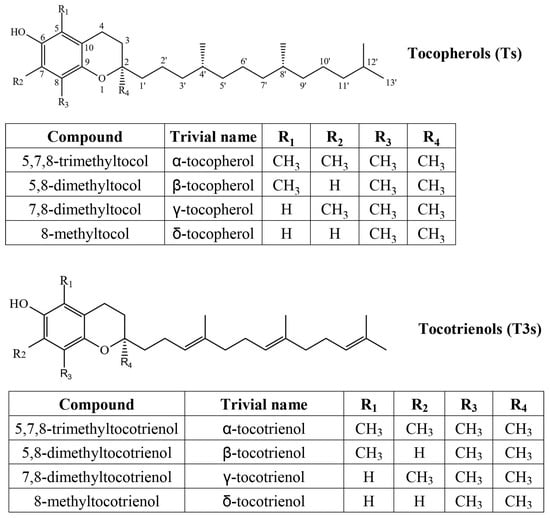

Tocochromanols consist of a chromane ring with a hydroxyl group (hydrogen donor) and a hydrophobic side chain, which is saturated in tocopherols and has three unsaturated bonds in tocotrienols, while the chromane ring is identical, and methyl group placement is analogous between the two compound groups (Figure 1). Both are used as antioxidants in the food and cosmetics industry and as dietary supplements. In addition to antioxidant activity, α-T is the preferentially absorbed and utilized form of vitamin E and the only form capable of treating vitamin E deficiency symptoms [16]. Tocotrienols are sometimes recognized as more active antioxidants [17] but may have inferior membrane permeability [18].

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of four tocopherol (T) and four tocotrienol (T3) homologs.

Previous studies have demonstrated consistent tocotrienol domination in several monocot families [19,20,21], while in dicotyledonous families, such observations are rare and exceptional [21]. Significant tocotrienol concentrations have been found in Apiaceae [22,23,24], Ranunculaceae [20,21], Sapindaceae [25,26], Vitaceae [20,27,28] and Ericaceae [20,29]. Notably, a recent investigation within Vitaceae [28] illustrates how chemotaxonomic tools can be effectively leveraged to uncover previously unrecognised natural sources of tocotrienols. The underlying concept is intentionally simple and readily transferable: when two species “A” and “B” within the same family “X” are shown to accumulate tocotrienols, it becomes highly plausible that other hitherto-unexamined species “C”, “D”, … “Z”, belonging to that same family “X”, will share this biochemical trait. This chemotaxonomic rationale underpins the approach adopted in the present study. The present research aims to (i) comprehensively characterise tocochromanol composition in Celastraceae species’ seeds, (ii) explore how these tocochromanol profiles align with the taxonomic relationships within the family, and (iii) to evaluate whether a more convenient and sustainable technique can be applied for the rapid extraction of these lipophilic molecules in a highly efficient and minimally hazardous manner.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

Solvents, including ethanol, ethyl acetate, n-hexane, and methanol (HPLC grade, >99.9%), and reagents, sodium chloride, pyrogallol, potassium hydroxide (reagent grade), were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). For UAEE protocol, 96.2% ethanol from Kalsnavas Elevators (Jaunkalsnava, Latvia) was used. Standards (purity > 95%, HPLC) of tocopherols (α, β, γ, and δ homologues) (LGC Standards, Teddington, Middlesex, UK) and tocotrienols (α, β, γ, and δ homologues) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) were used for the determination of tocochromanols in the seeds.

2.2. Plant Material

In total, 40 species, from 9 genera of the Celastraceae family, were analysed. Some samples of known genus but unknown species were received. These are included in data visualizations but were omitted from statistical calculations. A full accounting of samples is provided in Supplementary Materials. Most of the seed samples were obtained from botanical gardens across the world, mainly Eurasia, between 2019 and 2024, sent via mail, as part of seed exchange programmes between botanical gardens. The full list of botanical gardens that supported this project can be found in the Supplementary Materials. The species verification of provided plant material (seeds) was performed by the staff of the donor botanical garden, which shared their genetic resources. To reduce the impact of such factors as risk of misidentified species, crossbreeding, environmental factors, and others, origin (botanic garden) diversification was prioritised alongside species diversity. Synonymic species were checked using online databases, such as wikispecies.com (Accessed on 10 January 2024) and worldfloraonline.com (Accessed on 10 January 2024) (synonymic species), using the consensus or most recent reference available. Seeds were collected at full maturity, air-dried (20–30 °C), and stored in darkness to retain germination ability for the next vegetative season. The obtained seeds were catalogued as they were received and cleaned from other plant part residues, e.g., fruit flesh, if required. The seeds were stored in paper and plastic bags, away from direct light, under room-temperature conditions (21 ± 3 °C). Seed moisture was estimated at 10 ± 3%. To remove residual moisture before grinding, the seeds were frozen at −80 °C for 1–3 h, freeze–dried using a FreeZone freeze–dry system (Labconco, Kansas City, MO, USA) at a temperature of −51 ± 1 °C and <0.01 mbar for 24–48 h, depending on the size and number of seeds. Lyophilized seeds contained 3–7% moisture. Due to generally limited obtained seed mass, an average moisture content of 5% was used as default constant for tocochromanol calculation for all samples. Dry seeds (0.1–1 g) were powdered using an MM 400 mixer mill (Retsch, Haan, Germany), and tocochromanols were extracted the same day using ultrasound-assisted extraction and 96.2% ethanol (UAEE), as described below in Section 2.3.2. (all samples) and 2.3.1. for six randomly selected samples (recovery study).

2.3. Tocochromanol Extraction

2.3.1. Saponification

Saponification was performed according to a previously reported protocol [30]. The powdered seed samples (0.05–0.10 g) were placed in 15 mL glass tubes, mixed with 0.05 g of pyrogallol (an antioxidant), 2.5 mL ethanol, and subsequently 0.25 mL 60% aqueous potassium hydroxide (w/v). The tightly closed tubes were incubated in a water bath at 80 °C, mixed for 10 s after 10 min, and incubated for another 15 min, for a total incubation time of 25 min. After saponification, samples were cooled in a water-ice bath for 5 min, and then tocochromanols were extracted three times (re-extracted twice) using 2.5 mL n-hexane/ethyl acetate solution (9:1, v/v). The organic phase was combined in the flask, and solvents were evaporated. The remaining oily mixture was dissolved in 1 mL of ethanol, transferred to 2 mL glass vials and analysed immediately using a reversed-phase liquid chromatography system with fluorescence detection (RPLC-FLD).

2.3.2. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction in Ethanol (UAEE)

The greener method was adopted from a protocol developed for extraction of tocochromanols in cranberry seeds [30]. Unlike the saponification procedure, the UAEE protocol was implemented without adding an exogenous antioxidant, because our preliminary tests indicated that its inclusion did not significantly improve the stability or recovery of tocochromanols under the described extraction conditions. The powdered seeds (0.05–0.10 g) were placed in a 15 mL tube and supplemented with 5 mL 96.2% ethanol (v/v), mixed for 1 min at 3500 rpm using a vortex REAX top (Heidolph, Schwabach, Germany) and treated for 15 min at 60 °C in an ultrasonic bath Sonorex RK 510 H (Bandelin Electronic, Berlin, Germany). The ultrasonic bath was operated under a nominal ultrasonic power of 160 W and ultrasound frequency of 35 kHz. Extraction was carried out in sealed tubes and within a covered ultrasonic bath to restrict oxygen and light exposure. Immediately after completion of the ultrasonic step, the samples were mixed for 1 min as before, centrifuged at 11,000× g at 21 °C for 5 min on a Centrifuge 5804 R (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), and transferred directly to a 2 mL glass vial and analysed via RPLC-FLD.

2.3.3. Method Validation

Since the extraction of tocopherols and tocotrienols from all tested seeds using UAEE differs from most studies investigating tocochromanol content in plant material, the results were compared with the standard saponification protocol. Recovery (%) tests of tocopherols and tocotrienols from the seeds of six selected species from three genera (genus Euonymus: E. europaeus, E. hamiltonianus, and E. pauciflorus; genus Celastrus: C. orbiculatus and C. scandens; and genus Tripterygium: T. regelii) (6 × 3 UAEE vs. 6 × 3 saponification) were performed. Recovery (%) was calculated as an average value for three sample replications and assuming the saponification protocol as 100% recovery of tocochromanols. UAEE, ultrasound-assisted extraction, in ethanol using the following equation:

Repeatability (%) for both extraction protocols was evaluated. Repeatability (coefficient of variation) was calculated based on the independent determinations of a sample by analysing three replicates on the same day. Error of measurement (standard deviation) was calculated based on the independent determinations of a sample by analysing three replicates on the same day.

2.4. Tocochromanol Determination by Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography with Fluorescent Detection (RPLC-FLD)

The determination of four tocopherols and four tocotrienols was performed according to a reported method using authentic standards and calculated using calibration curves produced earlier [31]. The separation was performed on a Luna PFP column (3 µm, 150 × 4.6 mm) (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) using 93% methanol (v/v) as the mobile phase with 1 mL/min as the set flow rate and 40 °C for the column oven temperature. Measurements were taken on an LC 10 series (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) system equipped with a RF-10AXL fluorescence detector using the following detection parameters: excitation and emission λex = 295 nm and λem = 330 nm, respectively. Details of the method validation are provided in Table S1 (Supplementary Materials).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The results of all the performed experiments of different species’ seed samples are presented as means ± standard deviation (n = 1–12). Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to determine statistically significant differences between subfamilies, and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) was used to determine statistically similar subfamilies. The main differentiating tocochromanols were identified using principal component analysis (PCA), and samples were grouped based on tocochromanol composition using non-hierarchal k-means cluster analysis. All observed tocochromanol contents were used for statistical analyses, without data transformation, and potential outlier values were not excluded from the dataset. Base and open-source R packages (20de3565) MASS, factoextra and dplyr were used for data analysis, and open-source packages ggplot2, ggpubr, gghighlight, ggrepel, ggtext, patchwork and scales were used for data visualization in Rstudio (4.4.1) software.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Saponification and UAEE Recovery and Measurement Repeatability

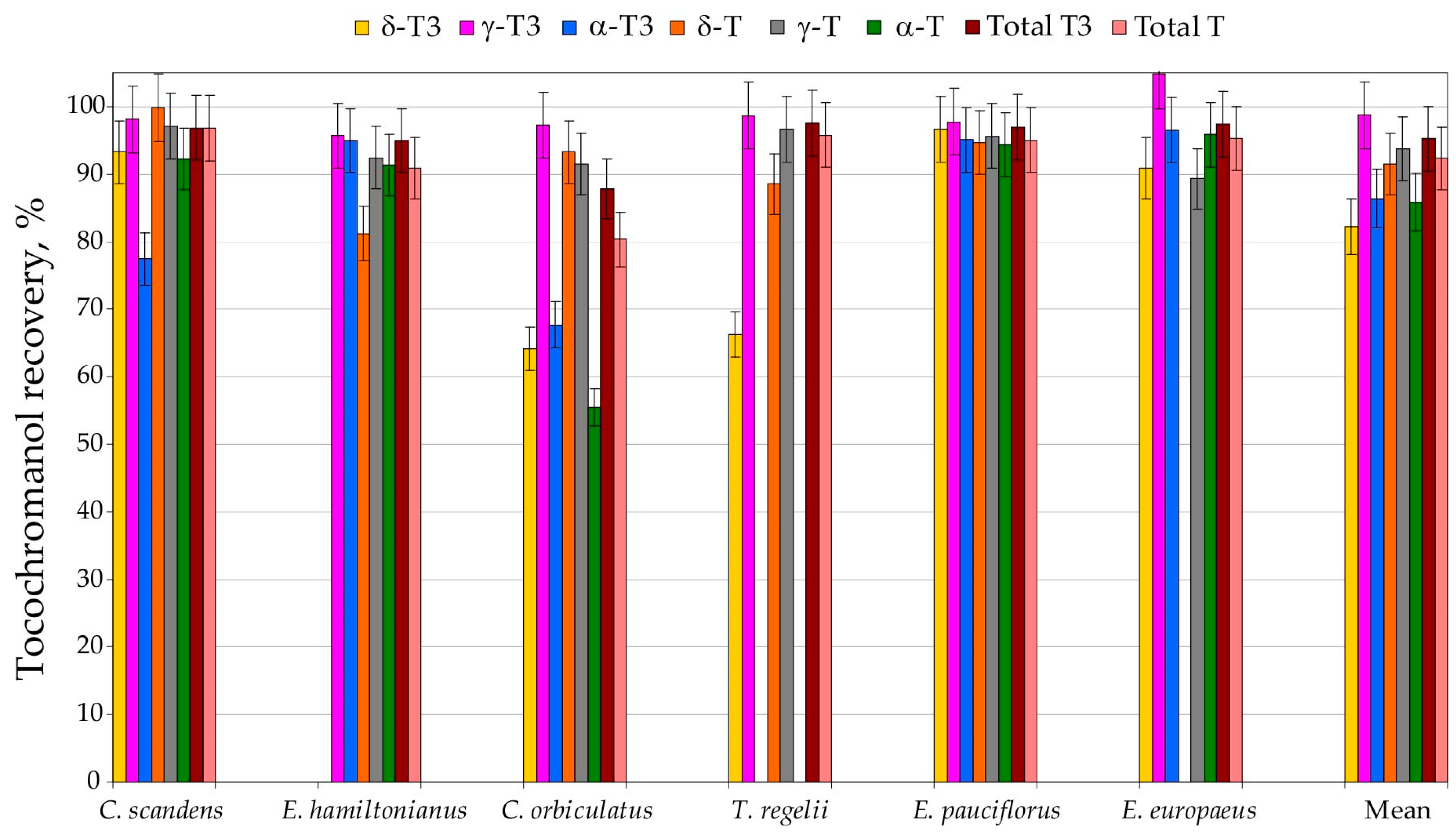

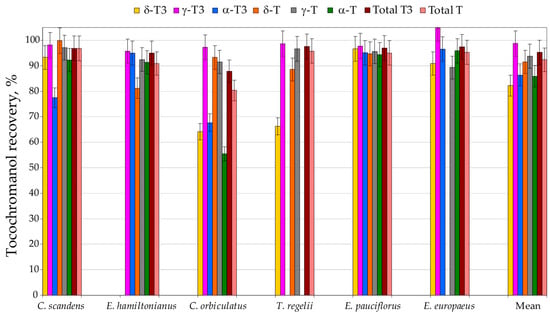

To assess the performance of the environmentally friendlier tocochromanol extraction approach, UAEE, it was compared with the conventional saponification protocol. Therefore, six selected species from three genera (genus Euonymus: E. europaeus, E. hamiltonianus, and E. pauciflorus; genus Celastrus: C. orbiculatus and C. scandens; and genus Tripterygium: T. regelii) seeds were prepared using UAEE and the saponification protocol for method validation and comparison. Recovery differed between tocochromanols and species. Recovery (relative to saponification protocol) of individual tocochromanols was the lowest for β-T3, which was detected in only three species and showed recoveries between 46% and 93% (mean 77%), and for β-T, found exclusively in C. orbiculatus seeds, where the recovery reached 83%. A considerable spread in recovery values was noted for δ-T3 (66–97%), α-T3 (68–97%), and α-T (55–96%), with corresponding mean recoveries of 82%, 86%, and 86%. In contrast, δ-T displayed a slightly narrower range (81–100%), with an average recovery of 91%. The most favourable results were obtained for the γ-homologues: γ-T3 showed recoveries of 96–105% (mean 99%), while γ-T ranged from 89% to 97% (mean 94%). In general, the lowest recoveries were typically associated with tocochromanols occurring at low and very low concentrations within the seed matrix of all species. Therefore, the overall method performance remained excellent, yielding high recoveries for total tocotrienols and total tocopherols, with averages of 95% and 92%, respectively (Figure 2, Table S2, Supplementary Materials).

Figure 2.

The recovery (%) of tocochromanols, total tocopherols (Ts) and tocotrienols (T3s), from seeds of six Celastraceae family species by using the UAEE protocol. Recovery (%) was calculated as the average value for three sample replications and assuming the saponification protocol as 100% recovery of tocochromanols. UAEE, ultrasound-assisted extraction, in ethanol.

The slightly elevated tocochromanol values obtained following saponification, compared with those from UAEE, are most likely due to the alkaline hydrolysis of ester- or glycoside-bound tocochromanols, as well as the release of compounds that are physically bound within the seed matrix and, therefore, not efficiently extracted through direct solvent treatment [32]. In some cases, the standard deviation bars imply recoveries above 100%, suggesting that UAEE can yield slightly higher values than saponification. This pattern is primarily a consequence of analytical variability inherent to extraction and quantification workflows. Nevertheless, it is also important to recognise that saponification should not be considered a completely loss-free reference procedure. Degradation of tocochromanols, mainly tocotrienols, may occur during alkaline hydrolysis, even when pyrogallol is included as a protective antioxidant, as was observed in grapes [33]. The comparatively lower extractability of tocopherols versus tocotrienols may arise not only from the potentially higher presence of bound tocopherols than tocotrienols in seeds but also from intrinsic physicochemical characteristics, especially α-T, due to it having the lowest solubility and extraction efficiency in 96.2% ethanol [33]. Because the differences between the two protocols were modest, individual tocochromanol concentrations were often low, the identification and quantification of bound forms is analytically demanding, and measurement variability is inherent [33], we did not undertake a detailed structural elucidation of these conjugates in the present work. Both methods showed acceptable repeatability; however, the UAEE protocol yielded, on average, approximately half the coefficient of variation for total tocopherols and tocotrienols compared with saponification, highlighting its practical advantages and suitability as a more environmentally friendly extraction procedure for Celastraceae seed tocochromanols. The average recovery of total tocochromanols was 95% (ranging 85–97%) relative to saponification. The UAEE protocol is clearly appropriate for routine, high-throughput comparative screening of Celastraceae seed samples. It is important to acknowledge that only six species were tested in this validation. Therefore, we cannot entirely rule out the possibility that certain species with unusually high levels of esterified tocochromanols might exhibit reduced recoveries when analysed using UAEE. That said, the current literature consistently indicates that free tocochromanols are the dominant forms in seed tissues [3], and no instances of extensive tocochromanol esterification in seeds have been documented to date. Processing hundreds or even thousands of samples requires extraction protocols that are rapid, reproducible, and safe both for operators and the environment. Alkaline saponification is still the most widely used sample preparation procedure for the analysis of tocochromanols and typically affords the highest recoveries of those lipophilic phytochemicals [31]. However, this approach is laborious and time-consuming and involves the use of unpleasant and hazardous organic solvents such as hexane and ethyl acetate, without distinguishing between free and esterified tocochromanols [32]. In this study, we show that a markedly simplified UAEE protocol can substantially reduce sample preparation time, labour demands, and occupational hazards related to solvent toxicity, while maintaining high tocochromanol recovery and repeatability. For large-scale screening, the optimised method, thus, represents a more sustainable and cost-effective alternative to the conventional saponification protocol, without compromising analytical performance. The protocol has already been successfully applied to tocochromanol profiling in cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) [30], grape (Vitis spp.) seeds [33], and in the Vitaceae family [28], yielding recoveries comparable to those obtained after the saponification method. Nevertheless, results generated by UAEE should not be directly equated with data from the saponified protocol; when investigating a new plant matrix, an initial comparative study against a standard saponification procedure is advisable. The proportion of esterified tocochromanols in plant tissues can vary widely—from constituting only a minor fraction to representing nearly the entire tocochromanol pool [5]. In addition, a portion of these compounds may be physically entrapped within the plant matrix, further influencing extractability and the interpretation of analytical results [32].

3.2. Tocochromanol Profile

In total, 125 samples from 40 species and 9 genera were analysed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Free tocochromanol content (mg 100 g−1 dw) in Celastraceae species’ seeds.

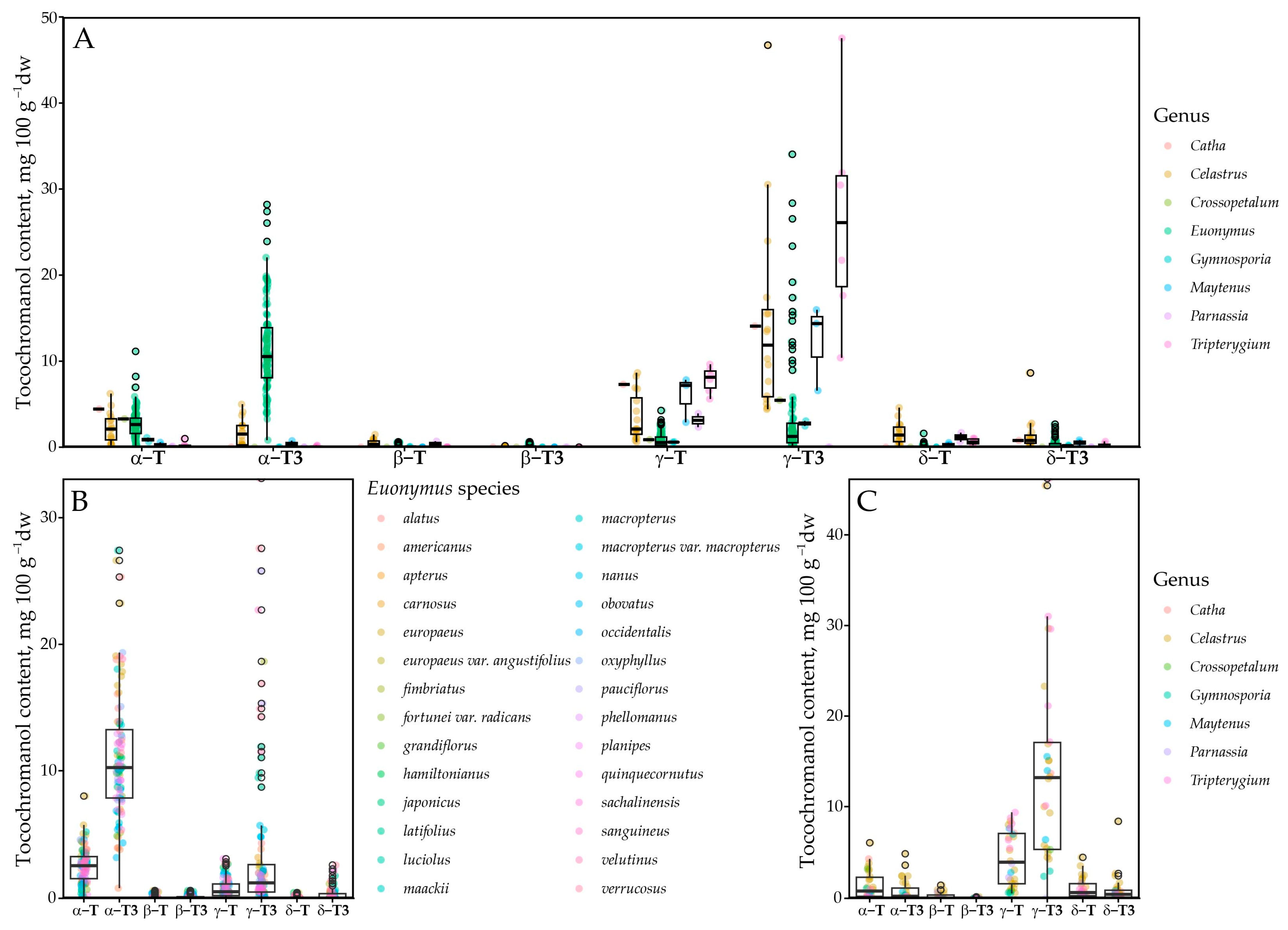

This study included samples from Catha (n = 1), Celastrus (n = 16), Crossopetalum (n = 1), Euonymus (n = 94), Maytenus (n = 3), Gymnosporia (n = 2), Parnassia (n = 2) and Tripterygium (n = 6) genus. The highest number of samples was analysed from the Euonymus genus, which constituted a majority (75%) of the analysed samples. Almost all species were tocotrienol-dominated, except Parnassia palustris, in which the tocochromanol content was very low and free T3s were not present. Although it is possible that tocochromanols are present in near-exclusively bound form in the species’ seeds [34], it is also possible that the seeds do not contain a significant amount of tocochromanols. Samples were generally tocotrienols-dominated (Figure 3). Of tocopherols, α-T and γ-T were present at the highest concentration. Among the taxa analysed, Parnassia palustris was distinctive in that no tocotrienols were detected and tocopherols were present only at low levels (4.72 mg 100 g−1 dw). When considering the γ-T3/α-T3 ratio, γ-T3 predominated in 17 species, whereas α-T3 predominated in 22, indicating a modest overall shift in favour of α-T3 across the dataset (Supplementary Materials).

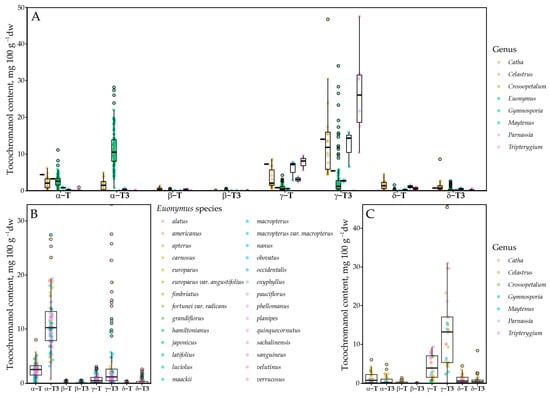

Figure 3.

Tocochromanol profile in the Celastraceae family. (A) All tested samples; (B) in the Euonymus genus; (C) excluding Euonymus genus. Point color denotes genus in (A,C), and species in (B) panel.

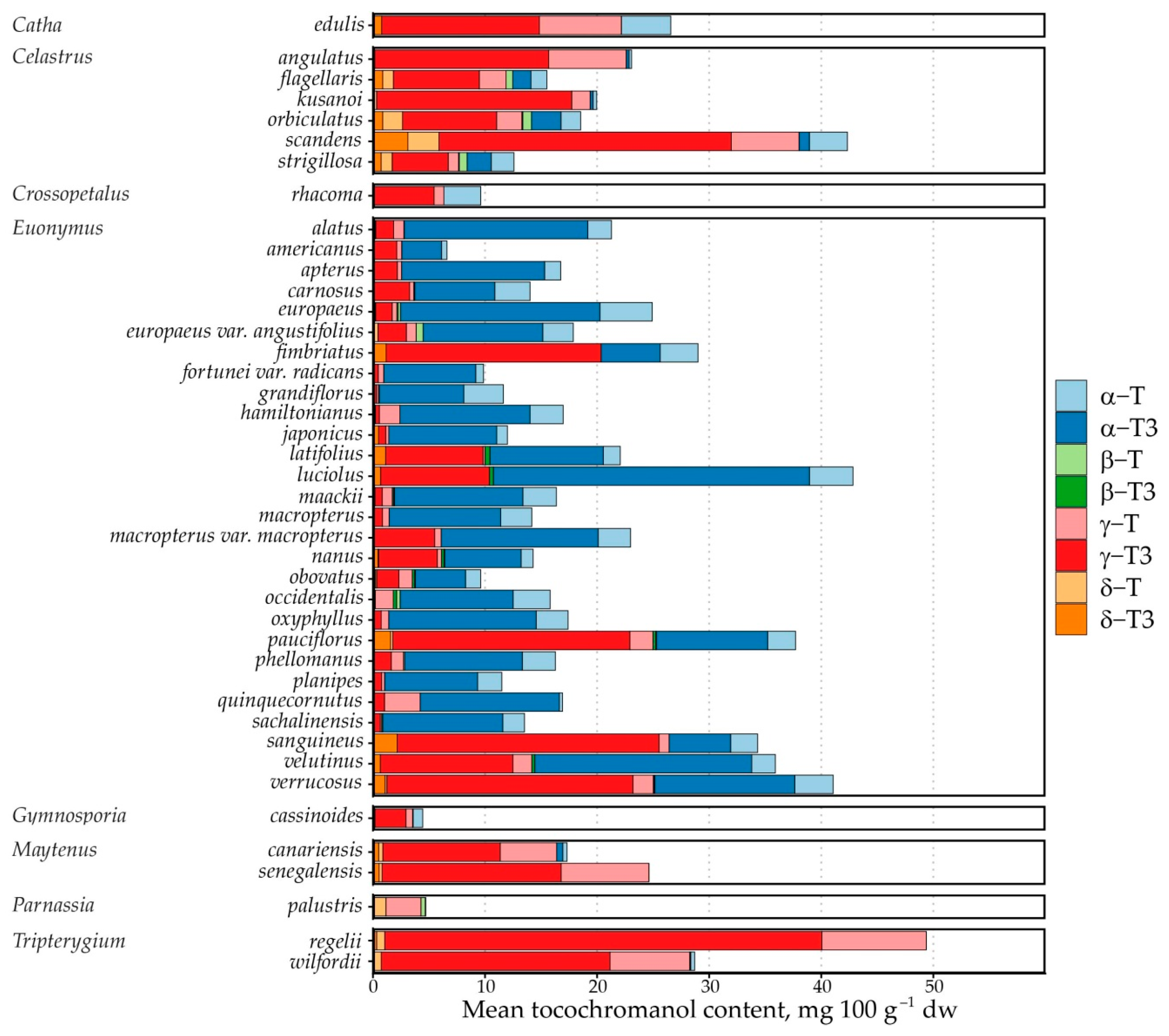

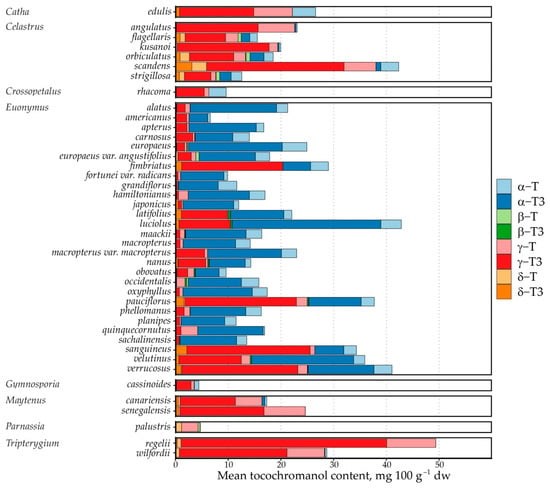

The tocochromanol profile was somewhat genus-dependent. Of the six Celastrus species, all contained mostly γ-T3, constituting between 35.5 and 70.6% of total tocochromanols, while the γ-homologue sum constituted up to 95.4% of total tocochromanols. In other genera, the tocochromanol profile is less consistent. The observed tocochromanol profile agrees to some extent with the only existing investigation of tocochromanols on the genus; γ-T domination over α-T was observed in C. paniculatus, but only tocopherols were investigated in the study. Additionally, the observed concentrations of γ-T (104 mg 100 g−1 dw) and α-T (52 mg 100 g−1 dw) were much higher [8] than in any of the samples in the present study. The highest total tocochromanol content was 66.22 mg 100 g−1 dw in C. scandens. This is likely because C. paniculatus oil was investigated, while the present study focuses on the seed. Other tocochromanols were not detected or present, or their content was low in Celastrus samples. In the Euonymus genus, α-T3 generally constituted the highest percentage of tocochromanols in most of the species, up to 86% of total tocochromanols. However, there were several exceptions, such as E. fimbriatus, E. pauciflorus, E. sanguineus, E. verrucosus, in which γ-T3 was generally dominant, and E. latifolius, E. luciolus, E. nanus, E. velutinus, in which γ-T3 content was higher.

Fewer samples were analysed in the other genera. Catha, Crossopetalum, Gymnosporia, Maytenus, and Tripterygium were all dominated by γ-T3, followed by γ-T, consistently. Tocotrienols were not detected in Parnassia palustris, which instead contained only a small amount of α-T (3.12 mg 100 g−1 dw, on average). This can be explained by plant physiology to some extent. Parnassia are the only flowering herbs in the dataset, while the others are trees, shrubs and vines with seeds relatively exposed to elements. Alternatively, tocochromanols may be chemically bound in the seeds and not detected during analysis, as the sample preparation did not have a saponification step. Fatty acid tocopheryl esters have been observed in several species and can constitute a significant portion of total tocochromanols [34].

Tocochromanol content varied significantly within species. While the highest observed tocochromanol content was 66.22 mg 100 g−1 dw in Celastrus scandens, another sample of the same species contained only 23.88 mg 100 g−1 dw. Similarly, E. verrucosus seeds contained between 62.11 and 26.45 mg 100 g−1 dw, and T. wilfordii seed tocochromanol content was between 41.42 and 17.81 mg 100 g−1 dw. The composition of tocochromanols was slightly less varied: in C. scandens seeds, γ-T3 constituted between 55.05 and 70.56% of total tocochromanols. The coefficient of variation for γ-T3 (1.46 for content, 0.98 for percentage values) was higher than α-T3 (0.73 for content, 0.60 for percentage values).

The relatively high standard deviation values (variability) observed for some species is a result of multiple factors, which can potentially affect the tocochromanols content. The main factors are as follows: abiotic factors, genetic background, and storage time. Abiotic factors, such as rainfall, sun radiation, temperature, and soil, can have a great impact on the tocochromanols profile in the seeds; however, the exact explanation for each of them is complex and ambiguous. For instance, in soybean, it was shown that temperature and water availability affect the profile of tocopherols, while total tocochromanols content was only modestly affected [35]. Genetic background within the same species is highlighted as the most significant factor affecting the profile and content of tocochromanols in seeds (from 10% up to 250%) [30,33,36,37]. Storage of some seeds, e.g., Brassica napus over 6 months, under suitable conditions, showed a lack of detectable tocochromanol degradation [38], while soybean storage under moderate conditions (25 °C; 12% moisture) for 12 months showed 6–7% tocopherol losses [39]. In summary, the foregoing considerations indicate that the principal drivers of variation in both tocochromanol composition and abundance among the seeds examined are genetic and abiotic factors [30,33]. As shown in Figure S1 (Supplementary Materials), there are several genus-dependant relationships between tocochromanols. Tocopherol and tocotrienol contents are mildly but consistently correlated (ρ = 0.501). In Celastrus, Euonymus and Tripterygium, tocotrienols are consistently methylated at chromane ring C7 (ρ = 0.978); tocochromanols with a methyl group at C7 are more abundant in Celastrus species. Tocopherol biosynthesis appears more differentiated and is less associated with specific biosynthetic steps (correlation coefficients are lower than respective tocotrienol values). Intermediary (δ- and γ-tocochromanols) products appear favoured over final (β- and α-tocochromanols) products, as tocotrienol and tocopherol contents are more strongly associated with intermediary (ρ = 0.765 and 0.639, respectively) than final (ρ = 0.279 and 0.034, respectively) biosynthesis products.

Analogous tocochromanols, e.g., α-T and α-T3, did not have strong and consistent correlation. The strongest and most consistent correlations between analogous tocochromanols were observed in the Celastrus genus, where analogous δ-, β- and γ-tocochromanols were correlated (ρ = 0.529, 0.701 and 0.752, respectively) but not α-tocochromanols, which were strongly correlated in Euonymus species (ρ = 0.667), while in Tripterygium species, only a reciprocal relationship between α-T and γ-T was observed (ρ = −0.857) but not between α-T3 and γ-T3.

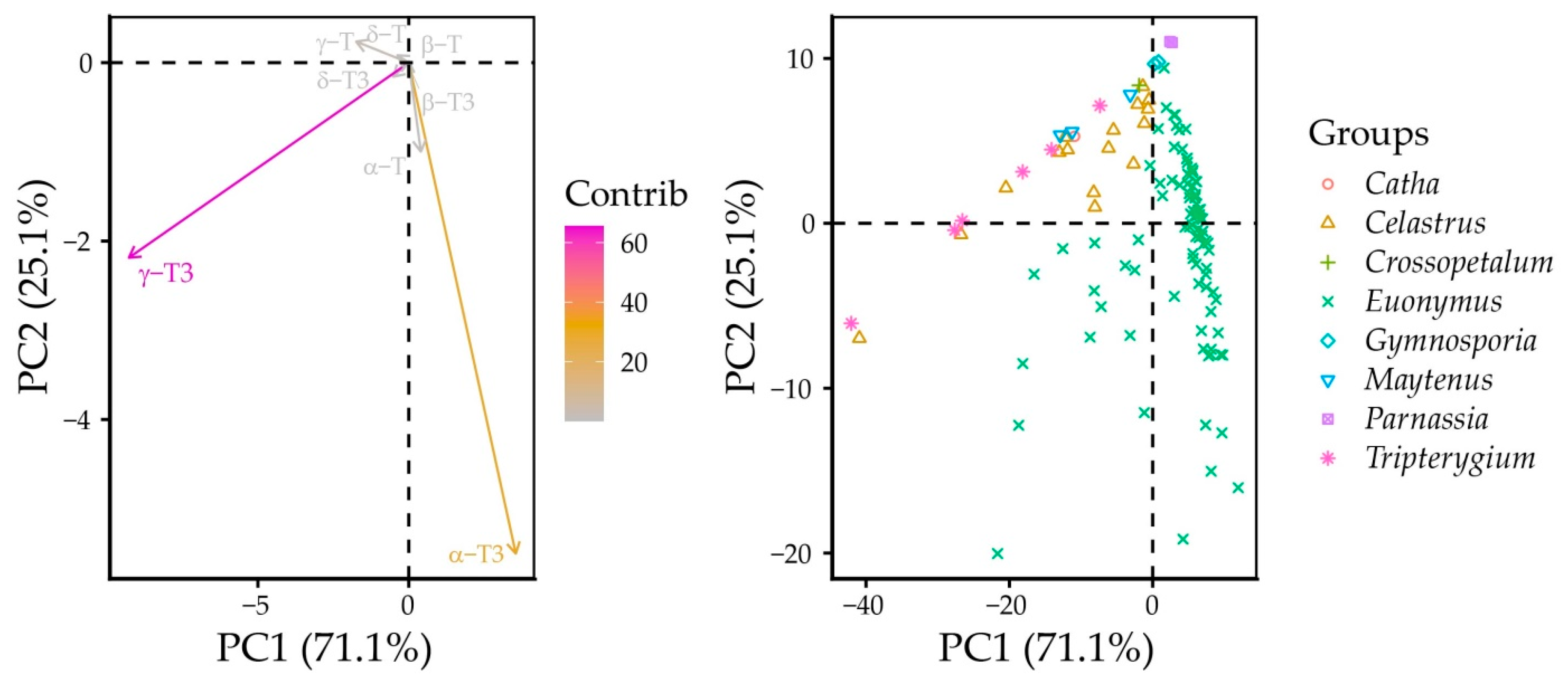

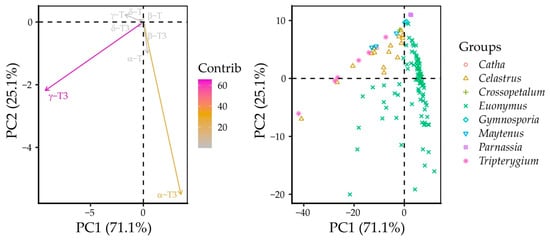

3.3. Tocochromanol Composition as Shaped by Phylogeny

Principal component (PC) analysis identified PC1 and PC2, which explained 71.1% and 25.1% of the total variance for a total of 96.2% explained variance. PC1 had high loadings with γ-T3 (−0.91) and α-T3 (0.35), while PC2 had high loadings with α-T3 (−0.92), γ-T3 (−0.36), and α-T (−0.17). As a result, γ-T3 had the highest contribution to PCA scores, followed by α-T3. Individual datapoints were located across these variable vectors, with Catha, Crossopetalum, Gymnospora, Maytenus, and Tripterygium forming a parallel ellipse to the γ-T3 vector, as were most of the Celastrus datapoints. Most of Euonymus grouped parallel to the α-T3 vector. Some of the Celastrus and Euonymus datapoints were located between the two branches of the dataset PCA scores (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Principal component analysis of unscaled Celastraceae seed tocochromanols.

This is due to the higher γ-T3 content in certain Euonymus species (E. fimbriatus, E. latifolius, E. luciolus, E. pauciflorus, E. sangiuneus, E. velutinus, and E. verrucosus), while in the Celastrus genus, certain species had slightly higher α-T3 contents: C. flagellaris, C. orbiculatus, and C. strigillosa (Figure 5). Although the γ-T content was quite variable between the genera, it did not have as significant contribution to PCA scores. Although its content was not statistically most different between genera, its proportion was distinctly lower in Euonymus species. Higher δ-tocochromanol content in Celastrus species’ seeds also did not affect their PCA scores. Notably, some genera, like Gymnosporia, Maytenus, Parnassia, and Tripterygium, appear to produce and accumulate exclusively γ-tocochromanols. This can be explained by the low activity of γ-tocopheryl methyl transferase activity in these species.

Figure 5.

Mean tocochromanol contents in Celastraceae species’ seeds. Data are expressed as mean tocochromanol content, mg 100 g−1 seeds dw.

The species’ tocochromanol contents do not match their phylogenetic tree entirely. Several phylogenetic studies place Tripterygium and Celastrus close [40,41], and their tocochromanol profiles are quite similar; Maytenus is placed closer to Euonymus [40,41], but the tocochromanol profile of Maytenus is more similar to Celastrus and Tripterygium, and more recent phylogenetic studies investigating a larger number of species place them even farther from Euonymus than Celastrus and Tripterygium [42]. Euonymus and Maytenus are estimated to have diverged much longer ago than Tripterygium and Celastrus [40], which may explain the divergence to some degree. Notably, there is significant variation within Celastrus and Euonymus as well. Of the Celastrus species in the study, C. flagellaris and C. scandens are placed the most closely on the phylogenetic tree [41], and their tocochromanol profile is similar. On the other hand, species which produced some exceptionally rare tocochromanols, like β-T3 in the Euonymus genus, are not on similar branches of the genus, nor are the γ-T accumulating species. Catha edulis is placed on the same Celastraceae branch as Maytenus and Euonymus, while Parnassia species constituted a separate branch from Celastraceae and Plumbaginaceae species in a Parnassia-centred study [43].

Comparisons with phylogenetic studies are limited by the narrow overlap between species in the present study and the existing literature and the scale of the existing literature. PCA results support the hypothesis for phylogeny-driven tocochromanol profiles through similarities between closely related genera (Triperygium and Celastrus) and the separation of phylogenetically separate genera (like Parnassia), but this does not easily explain differences between species within the same genus. Moreover, the recovery of certain tocochromanols in C. orbiculatus and T. regelii was relatively low—a significant portion of them may be esterified or otherwise bound. Future studies on these genera are especially recommended to use both protocols in parallel (UAEE and saponification) for detailed tocochromanol analysis. In addition to tocochromanol analysis, we highly recommend including carotenoid and chlorophyll content analysis in future studies, as these compounds and tocochromanols use common precursors, and many species are differentiated by bright fruit colour and characteristic terpenoids.

4. Conclusions

Based on the presented evidence, the tocochromanol profile of Celastraceae species seeds is tocotrienol-dominated, γ-T3 (17 species) or α-T3 (22 species), which is considered rare in eudicots. Only P. palustris was distinctive in that no tocotrienols were detected, while tocopherol levels were relatively low (4.72 mg 100 g−1 dw). The greatest tocotrienol accumulation—driven largely by γ-tocotrienol—was observed in Celastrus scandens, Euonymus verrucosus, and Tripterygium regelii, with concentrations exceeding 47 mg 100 g−1 dw. Although many species in the family have significant seed oil content, many of them are known to be toxic to humans, and further analysis is needed before recommendation in ingestible or topical application products.

UAEE had good repeatability and slightly lower recovery than the saponification protocol, and UAEE can be considered a reliable tocochromanol extraction method for Celastraceae family seeds. It can be recommended for routine monitoring but should be validated for any new plant material, since it only allows one to extract free tocochromanols, and information on the proportion of esterified and otherwise-bound tocochromanols is very limited at this time.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16031521/s1. Figure S1: Pair chart showing Pearson correlation coefficients (above diagonal), content density chart (diagonal) and scatter plots (below diagonal) between tocochromanol groups in the Celastrus, Euonymus and Tripterygium genus. Other genera have been excluded due to insufficient datapoints. Tocochromanols are grouped based on their biosynthetic pathway: tocotrienols, tocopherols, intermediary (δ- and γ-tocochromanols), final (β- and α-tocochromanols), R2-methyl group (γ- and α-tocochromanols), R2-hydrogen atom (δ- and β-tocochromanols) at chromane ring C7. Table S1: Linearity, limit of detection (LOD), limits of quantification (LOQ), and retention time (RT) of the RP-HPLC-FLD method for tocochromanols determination. Table S2: Repeatability (%) for the determination of tocopherols and tocotrienols in the seeds of Celastraceae family.

Author Contributions

D.L.: conceptualization, investigation, resources, data curation, validation, software, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; I.M.: resources, formal analysis; K.D.: resources, formal analysis, data curation; P.G.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, visualization, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Latvian Council of Science project “Dicotyledonous plant families and green tools as a promising alternative approach to increase the accessibility of tocotrienols from unconventional sources”, project No. lzp-2020/1-0422.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Materials and from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Georgijs Baškirovs for his contribution to the sample analysis and data handling and Arturs Stalažs for his support in the collection of seeds. We were able to perform this research due to generous support from over 150 botanical gardens around the world, in the form of seed donations. A list of botanical gardens that supported this project is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

RP-HPLC, reversed-phase liquid chromatography; dw, dry weight; T, tocopherol; T3, tocotrienol.

References

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Celastraceae. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:30000478-2 (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Christenhusz, M.J.; Byng, J.W. The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase. Phytotaxa 2016, 261, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, B.E. A review of commercially important African medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 176, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekuria, W. Public discourse on Khat (Catha edulis) production in Ethiopia. J. Agric. Ext. Rural Dev. 2018, 10, 192–201. [Google Scholar]

- Su, P.; Gao, L.; Tong, Y.; Guan, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, T.; Tu, L. Analysis of the role of geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase 8 from Tripterygium wilfordii in diterpenoids biosynthesis. Plant Sci. 2019, 285, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, H.N.; Joseph, K.S.; Madiwal, A.; Rajan, G.D.; Badiger, M.; Kolkar, L.; Hiremath, R.; Shirugumbi, M. Chemical composition and fatty acid profile of Khat (Catha edulis) seed oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2016, 93, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, V.S.; Das, M. Fatty acid and non-fatty acid components of the seed oil of Celastrus paniculatus willd. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2017, 17, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, M.F.; Kinni, S.G.; Rajanna, L.N.; Seetharam, Y.N.; Seshagiri, M.; Mörsel, J.-T. Fatty acids, bioactive lipids and radical scavenging activity of Celastrus paniculatus Willd. seed oil. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 123, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.; Ahmad, M.; Waseem, A.; Zafar, M.; Saeed, M.; Wakeel, A.; Nazish, M.; Sultana, S. Scanning electron microscopy leads to identification of novel nonedible oil seeds as energy crops. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2019, 82, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorov, R.A.; Pchelkin, V.P.; Zhukov, A.V.; Tsydendambaev, V.D. Positional-species composition of diacylglycerol acetates from mature euonymus seeds. Chem. Biodivers. 2016, 13, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorov, R.A.; Zhukov, A.V.; Pchelkin, V.P.; Vereshchagin, A.G.; Tsydendambaev, V.D. Content and fatty acid composition of neutral acylglycerols in Euonymus fruits. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorov, R.A.; Pchelkin, V.P.; Zhukov, A.V.; Vereshchagin, A.G.; Tsydendambaev, V.D. Positional-species composition of triacylglycerols from the arils of mature Euonymus fruits. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 2053–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-Z.; Cui, Q.; Kang, Y.-F.; Meng, Y.; Gao, M.-Z.; Efferth, T.; Fu, Y.-J. Euonymus maackii Rupr. Seed oil as a new potential non-edible feedstock for biodiesel. Renew. Energy 2019, 133, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benni, S.D.; Munnolli, R.S.; Katagi, K.S.; Kadam, N.S. Mussel shells as sustainable catalyst: Synthesis of liquid fuel from non edible seeds of Bauhinia malabarica and Gymnosporia montana. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 4, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginocchio, R.; Muñoz-Carvajal, E.; Velásquez, P.; Giordano, A.; Montenegro, G.; Colque-Perez, G.; Sáez-Navarrete, C. Mayten tree seed oil: Nutritional value evaluation according to antioxidant capacity and bioactive properties. Foods 2021, 10, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, A. Tocopherols, tocotrienols and tocomonoenols: Many similar molecules but only one vitamin E. Redox Biol. 2019, 26, 101259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmowski, J.; Hintze, V.; Kschonsek, J.; Killenberg, M.; Böhm, V. Antioxidant activities of tocopherols/tocotrienols and lipophilic antioxidant capacity of wheat, vegetable oils, milk and milk cream by using photochemiluminescence. Food Chem. 2015, 175, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, Y.; Saito, Y.; Jones, L.S.; Shigeri, Y. Chemical reactivities and physical effects in comparison between tocopherols and tocotrienols: Physiological significance and prospects as antioxidants. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2007, 104, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles, L.; Cela, J.; Munné-Bosch, S. Vitamin E analyses in seeds reveal a dominant presence of tocotrienols over tocopherols in the Arecaceae family. Phytochemistry 2013, 95, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siger, A.; Górnaś, P. Free tocopherols and tocotrienols in 82 plant species’ oil: Chemotaxonomic relation as demonstrated by PCA and HCA. Food Res. Int. 2023, 164, 112386. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, G.; Wessjohann, L.; Bigirimana, J.; Jansen, M.; Guisez, Y.; Caubergs, R.; Horemans, N. Differential distribution of tocopherols and tocotrienols in photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic tissues. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 1185–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagci, E. Fatty acids and tocochromanol patterns of some Turkish Apiaceae (Umbelliferae) plants; a chemotaxonomic approach. Acta Bot. Gallica 2007, 154, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.A.; Aitzetmüller, K. Untersuchungen über die tocopherol-und tocotrienolzusammensetzung der samenöle einiger vertreter der familie Apiaceae. Lipid/Fett 1995, 97, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnaś, P. Domination of tocotrienols over tocopherols in seed oils of sixteen species belonging to the Apiaceae family. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 142, 107535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeutsop, J.F.; Zébazé, J.N.; Nono, R.N.; Frese, M.; Chouna, J.R.; Lenta, B.N.; Nkeng-Efouet-Alango, P.; Sewald, N. Antioxidant and cytotoxicity activities of δ-tocotrienol from the seeds of Allophylus africanus. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 36, 4655–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangsopha, W.; Schevenels, F.T.; Lekphrom, R.; Kanokmedhakul, S. A new tocotrienol from the roots and branches of Allophylus cobbe (L.) Raeusch (Sapindaceae). Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wie, M.; Sung, J.; Choi, Y.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, H.S.; Lee, J. Tocopherols and tocotrienols in grape seeds from 14 cultivars grown in Korea. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2009, 111, 1255–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazdiņa, D.; Mišina, I.; Dukurs, K.; Górnaś, P. Seed tocochromanol-based chemotaxonomy of Euroasian grapevine (Vitaceae) species. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2026, 150, 108893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Ahotupa, M.; Määttä, P.; Kallio, H. Composition and antioxidative activities of supercritical CO2-extracted oils from seeds and soft parts of northern berries. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2009–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnaś, P.; Lazdiņa, D.; Mišina, I.; Sipeniece, E.; Segliņa, D. Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Aiton) seeds: An exceptional source of tocotrienols. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 331, 113107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnaś, P.; Siger, A.; Czubinski, J.; Dwiecki, K.; Segliņa, D.; Nogala-Kalucka, M. An alternative RP-HPLC method for the separation and determination of tocopherol and tocotrienol homologues as butter authenticity markers: A comparative study between two European countries. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2014, 116, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnaś, P.; Baškirovs, G.; Siger, A. Free and esterified tocopherols, tocotrienols and other extractable and non-extractable tocochromanol-related molecules: Compendium of knowledge, future perspectives and recommendations for chromatographic techniques, tools, and approaches used for tocochromanol determination. Molecules 2022, 27, 6560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Górnaś, P.; Mišina, I.; Waśkiewicz, A.; Perkons, I.; Pugajeva, I.; Segliņa, D. Simultaneous extraction of tocochromanols and flavan-3-ols from the grape seeds: Analytical and industrial aspects. Food Chem. 2025, 462, 140913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauß, S.; Darwisch, V.; Vetter, W. Occurrence of tocopheryl fatty acid esters in vegetables and their non-digestibility by artificial digestion juices. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britz, S.J.; Kremer, D.F. Warm temperatures or drought during seed maturation increase free α-tocopherol in seeds of soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6058–6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siger, A.; Michalak, M.; Bąkowska, E.; Dwiecki, K.; Nogala-Kałucka, M.; Grześ, B.; Piasecka-Kwiatkowska, D. The effect of the genotype-environment interaction on the concentration of carotenoids, tocochromanol, and phenolic compounds in seeds of Lupinus angustifolius breeding lines. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 123, 105511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siger, A.; Michalak, M.; Lembicz, J.; Nogala-Kałucka, M.; Cegielska-Taras, T.; Szała, L. Genotype× environment interaction on tocochromanol and plastochromanol-8 content in seeds of doubled haploids obtained from F1 hybrid black× yellow seeds of winter oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 3263–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, F.D.; Möllers, C. Changes in tocopherol and plastochromanol-8 contents in seeds and oil of oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) during storage as influenced by temperature and air oxygen. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, V.; Vanier, N.L.; Ferreira, C.D.; Paraginski, R.T.; Monks, J.L.F.; Elias, M.C. Changes in the bioactive compounds content of soybean as a function of grain moisture content and temperature during long-term storage. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, H762–H768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Dai, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Qiu, G.; Gao, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, S. Comparative analysis the chloroplast genomes of Celastrus (Celastraceae) species: Provide insights into molecular evolution, species identification and phylogenetic relationships. Phytomedicine 2024, 131, 155770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.-Y.; Zhao, L.-C.; Zhang, Z.-X. Phylogeny of Celastrus L. (Celastraceae) inferred from two nuclear and three plastid markers. J. Plant Res. 2012, 125, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, M.P.; Savolainen, V.; Clevinger, C.C.; Archer, R.H.; Davis, J.I. Phylogeny of the Celastraceae inferred from 26S nuclear ribosomal DNA, phytochrome B, rbcL, atpB, and morphology. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2001, 19, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, M.-Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, F.-Q.; Yu, J.-Y.; Khan, G.; Chi, X.-F.; Xu, H.; Chen, S.-L. Reassessment of the phylogeny and systematics of Chinese Parnassia (Celastraceae): A thorough investigation using whole plastomes and nuclear ribosomal DNA. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 855944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.