Abstract

Growing limitations on the use of in-feed antibiotics have accelerated the search for functional feed additives capable of supporting animal health and productivity under antibiotic-free production systems. Postbiotics, defined as non-viable microbial products or metabolic byproducts, and phytogenics, which are plant-derived bioactive compounds, have emerged as promising alternatives due to their stability and biological activity. Recent advances in the application of postbiotics and phytogenics in monogastric and ruminant nutrition are summarized, with emphasis on their mechanisms of action, synergistic effects, and impacts on gut health, immune function, and growth performance. Postbiotics modulate the gut microbiota, enhance epithelial barrier integrity, and regulate immune signaling, whereas phytogenic compounds provide antimicrobial, antioxidant, and digestive-stimulant effects. Available evidence suggests that combined strategies can enhance efficacy, particularly under production-related stress. Key challenges related to formulation, dose–response relationships, stability, and regulatory classification are discussed together with emerging omics-based approaches that support precision formulation. Overall, integration of multi-omics evidence with formulation and regulatory considerations supports the practical use of postbiotics and phytogenics in commercial livestock systems.

1. Introduction

The rapid transition toward antibiotic-free livestock production has driven global efforts to identify nutritional strategies that maintain animal health and performance while mitigating antimicrobial resistance [1]. The long-term use of sub-therapeutic antibiotics as growth promoters, which was once a cornerstone of intensive livestock systems, has been progressively banned or restricted in the European Union, North America, and other regions due to concerns over antimicrobial resistance and environmental contamination [1,2]. The withdrawal of antibiotics from feed has led to higher rates of enteric disorders, reduced feed efficiency, and economic losses. This highlights the need for safe and sustainable alternatives [3].

As a result, functional feed additives have gained attention as tools to support gut health, improve nutrient utilization, and enhance animal resilience. These include probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and phytogenic feed additives (PFAs) [4,5]. Among these, postbiotics and phytogenics are particularly promising because they combine defined chemical composition, safety, and functional efficacy, offering potential consistency across production systems.

Postbiotics are defined by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) as “preparations of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confer a health benefit on the host” and represent the next generation of microbial-derived feed components [6]. Their biologically active metabolites include short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bacteriocins, extracellular polysaccharides, enzymes, and cell-wall fragments that exert antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects [7,8,9]. These compounds modulate epithelial integrity, regulate tight-junction proteins, and interact with pattern-recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), thereby enhancing mucosal immunity and reducing pathogen colonization. In monogastric animals, postbiotic supplementation has been associated with improved villus height, better feed conversion ratio, and reduced intestinal inflammation; in ruminants, it has improved ruminal fermentation efficiency and nitrogen utilization [10,11,12] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary comparison table: Postbiotics vs. phytogenics.

Phytogenics (botanicals) constitute a heterogeneous class of plant-derived bioactive molecules, including essential oils, polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, and saponins [2,3,4,5]. Their antioxidant, antimicrobial, and digestive-stimulant properties support gut health, enhance nutrient utilization, and make phytogenic compounds effective natural growth promoters in livestock nutrition [13,14].

Mechanistically, phytogenics enhance the secretion of digestive enzymes and bile acids, modulate gut microbial populations, and protect tissues from oxidative stress through upregulation of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase. In poultry and swine, essential-oil mixtures containing thymol, carvacrol, or cinnamaldehyde have been shown to improve weight gain and feed efficiency, while in ruminants, plant secondary metabolites modulate rumen fermentation by decreasing methanogenesis and optimizing volatile-fatty-acid profiles [15,16].

Despite these promising findings, the reproducibility of outcomes across farms remains inconsistent due to variation in microbial strains, plant species, extraction methods, and interactions with basal diets [12,17]. Moreover, the biological effects of postbiotics and phytogenics are influenced by host genotype, microbiota composition, and environmental factors [6,7,8]. Emerging omics-based tools, including metagenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, now allow systematic elucidation of host–microbe–metabolite interactions [18,19,20].

The synthesis of recent advances in the application of postbiotics and phytogenics as functional feed additives in both monogastric and ruminant nutrition holds considerable significance. Emphasis is placed on elucidating their mechanisms of action, potential synergistic interactions, and combined effects on gut health, immune modulation, and growth performance [9]. In addition, key formulation, stability, and regulatory challenges related to practical implementation are addressed, together with emerging research directions such as omics-guided discovery approaches and nano-delivery technologies. These strategies aim to enhance the efficacy, stability, and consistency of bioactive compounds in support of sustainable and resilient animal production systems. Unlike conventional narrative reviews, this article integrates mechanistic evidence with formulation, stability, and regulatory considerations to provide an applied decision framework for precision deployment of postbiotics and phytogenics in commercial livestock systems.

2. Context of Postbiotics and Phytogenics in Antibiotic-Free Livestock Production

The progressive restriction and elimination of antibiotic growth promoters have prompted the development of a diverse portfolio of alternative feed additives aimed at sustaining animal health, productivity, and production efficiency under commercial production constraints. These alternatives include probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, organic acids, enzymes, immunomodulators, and plant-derived bioactives, each targeting distinct aspects of gastrointestinal function and host resilience [10,11,12]. However, variability in efficacy, sensitivity to feed processing, and inconsistent performance under commercial conditions have limited the universal applicability of many of these strategies.

Within this landscape, postbiotics and phytogenics occupy a distinct and increasingly relevant functional niche. Unlike probiotics, which rely on microbial viability and successful colonization of the gastrointestinal tract, postbiotics consist of non-viable microbial cells and/or their bioactive metabolites that exert direct biological effects independent of survival in the feed or gut environment [13,14]. This characteristic confers superior stability during pelleting, storage, and transport, thereby reducing performance variability associated with thermal processing and shelf-life constraints [15,16]. In contrast to prebiotics, whose efficacy depends strongly on resident microbiota composition, postbiotics deliver defined signaling molecules such as short-chain fatty acids, bacteriocins, and cell wall components that act directly on epithelial and immune pathways with greater reproducibility across production systems [13,17].

From an applied-nutrition perspective, postbiotics and phytogenics offer complementary advantages relative to other antibiotic alternatives. Organic acids and enzymes primarily influence digestive chemistry and substrate availability, whereas postbiotics directly modulate epithelial integrity and immune signaling, and phytogenics contribute additional layers of microbial and metabolic regulation [2,13]. Importantly, both postbiotics and phytogenics are less dependent on host-specific microbial colonization dynamics, making them particularly suitable for use during early life stages, stress periods (e.g., weaning, heat stress), and high-density commercial production systems where microbiome instability is common [4,18].

The combined use of postbiotics and phytogenics further enhances their applied value. Postbiotics provide consistent microbial-derived signals that stabilize gut barrier function and immune homeostasis, while phytogenics reduce pathogen pressure and oxidative stress at the luminal interface [19,20]. This functional complementarity supports a systems-level approach to gut health that aligns with precision-nutrition paradigms and reduces reliance on single-mechanism interventions. Consequently, postbiotics and phytogenics are increasingly viewed not merely as antibiotic substitutes, but as modular tools within integrated feed-additive strategies designed to optimize performance, resilience, and sustainability under real-world production constraints [12,13].

Given their defined composition, processing stability, and complementary biological actions, postbiotics and phytogenics are examined in detail in the following sections, with emphasis on their mechanisms of action, synergistic interactions, and practical deployment in antibiotic-free livestock systems.

3. Postbiotics in Animal Nutrition

3.1. Definition and Classification

The term postbiotic has recently gained scientific and regulatory recognition as a distinct category of microbial-derived feed components with health-promoting functions that are independent of cell viability. According to the consensus definition established by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), postbiotics are “preparations of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confer a health benefit on the host” [14]. This definition clearly distinguishes postbiotics from probiotics, which require microbial viability, and from paraprobiotics, which generally describe inactivated microbial cells without a defined functional claim [17].

Postbiotics encompass a broad spectrum of biologically active molecules, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bacteriocins, enzymes, exopolysaccharides, peptidoglycans, lipoteichoic acids, and other cell-wall–derived components generated during microbial fermentation or inactivation processes [8,21,22]. These preparations are typically produced through controlled thermal, chemical, or mechanical inactivation of selected bacterial strains, most commonly Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Bacillus, or Enterococcus spp., followed by stabilization and incorporation into feed matrices [11,14,23]. Importantly, the functional activity of a postbiotic depends not only on its chemical composition but also on manufacturing conditions, fermentation substrates, and downstream processing steps [14]. Postbiotic categories and their primary functional applications are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Classification and functional applications of major postbiotic categories in animal nutrition.

3.2. Mechanisms of Action

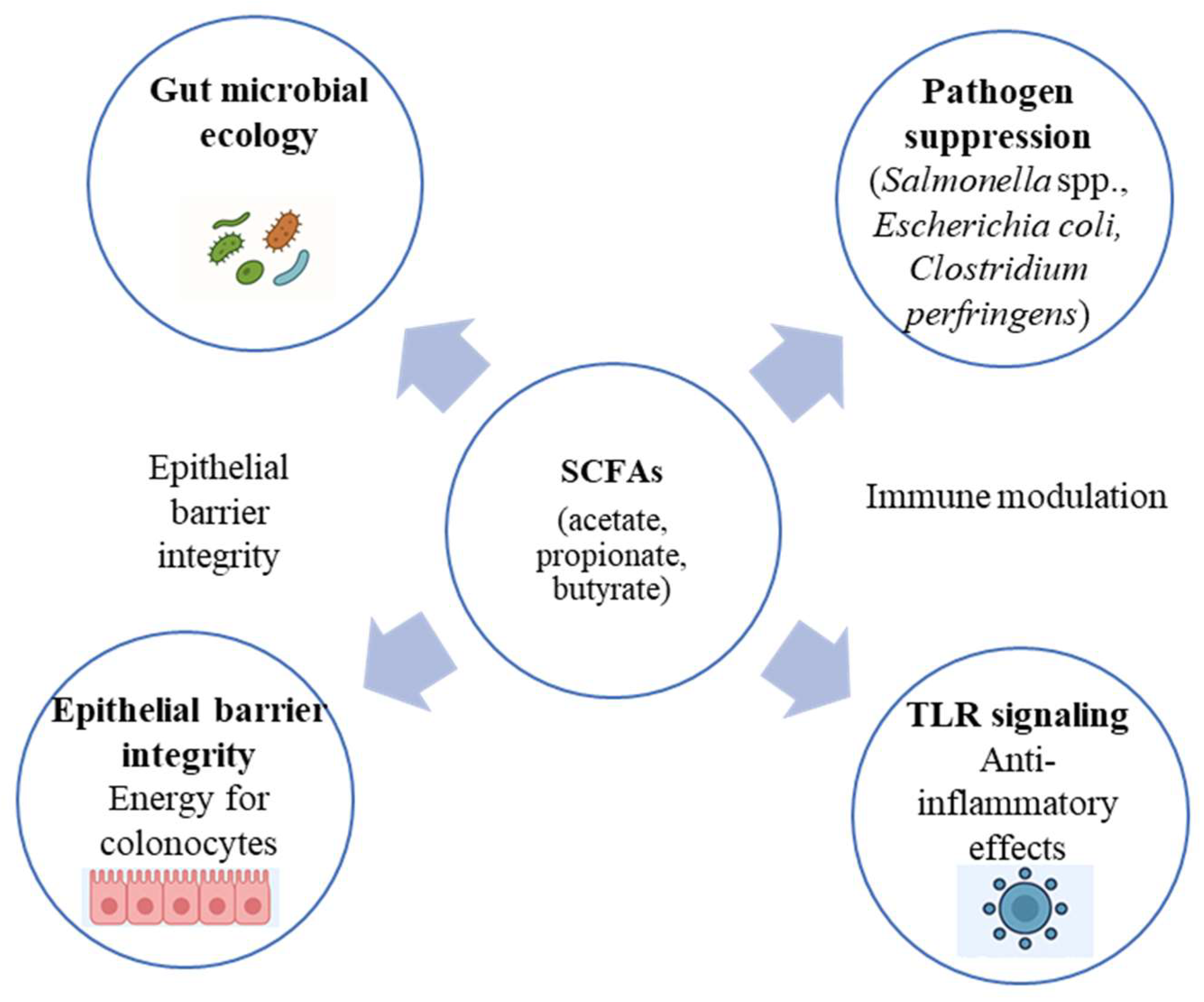

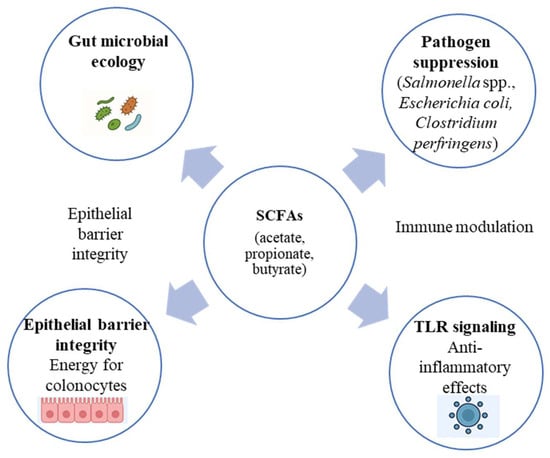

Postbiotics exert multifaceted effects on host physiology through several interconnected mechanisms involving the gut microbiota, epithelial barrier, and immune system. The integrated biological pathways underlying postbiotic activity are illustrated in Figure 1. One major mode of action is the modulation of gut microbial ecology. Postbiotic metabolites, particularly SCFAs such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, serve as energy substrates for colonocytes and simultaneously create an acidic luminal environment that suppresses the growth of pathogenic bacteria, including Salmonella spp., E. coli, and Clostridium perfringens [4,7]. Butyrate also acts as a histone-deacetylase inhibitor that regulates epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation, thereby maintaining intestinal integrity [27].

Figure 1.

Integrated biological pathways through which postbiotics influence gut barrier integrity, immune signaling, and microbial ecology in livestock.

Another key mechanism is the strengthening of the epithelial barrier. Structural components such as peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid interact with Toll-like receptors (TLR2 and TLR4) and NOD-like receptors on epithelial and immune cells, triggering controlled signaling cascades that up-regulate tight-junction proteins (occludin, claudin-1, and zonula occludens-1) and mucin secretion [9,28,29]. These effects reduce the translocation of pathogens and endotoxins, thereby lowering the risk of systemic inflammation.

Postbiotics also demonstrate anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties. Experimental studies in pigs and poultry have shown decreased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β) and enhanced production of anti-inflammatory mediators (IL-10) following supplementation with inactivated Lactobacillus plantarum or Bacillus subtilis preparations [30,31,32,33]. Some metabolites can modulate regulatory T-cell responses and influence macrophage polarization toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype [27].

Finally, postbiotics contribute to metabolic efficiency by improving feed digestibility and nutrient absorption. Enzymes and organic acids produced during fermentation stimulate pancreatic secretions and optimize the digestive milieu, leading to improved feed conversion ratios (FCRs) and growth rates [34,35].

3.3. Challenges and Limitations of Postbiotics

Despite their growing adoption, several challenges limit the broad and standardized implementation of postbiotics in livestock nutrition. A key constraint is the heterogeneity of postbiotic preparations, as bioactive composition depends strongly on microbial strain selection, fermentation substrates, and inactivation methods. Variability in manufacturing processes can result in inconsistent concentrations of functional metabolites and structural components, complicating dose optimization and cross-study comparability.

In addition, standardized metrics for postbiotic bioactivity remain underdeveloped, and optimal inclusion rates may vary across species, production stages, and health status. From a regulatory perspective, postbiotics occupy an evolving classification space that differs across regions, creating uncertainty in labeling and authorization pathways. Finally, while experimental and short-term production studies demonstrate promising effects, long-term field-scale evaluations remain limited, highlighting the need for harmonized production standards and robust validation under commercial conditions.

3.4. Evidence in Monogastric and Ruminant Species

The efficacy of postbiotics has been demonstrated across multiple livestock species, although the magnitude and consistency of responses vary depending on species, microbial strain, diet composition, and production context. In broiler chickens, dietary inclusion of heat-treated Lactobacillus fermentum has been associated with increased body-weight gain and reduced cecal counts of C. perfringens, coinciding with improvements in villus height and crypt-to-villus ratios [36,37]. Comparable outcomes have been reported in pigs, where supplementation with Bacillus subtilis postbiotic preparations improved intestinal morphology and immune-related parameters while reducing diarrhea incidence during the post-weaning period [38,39].

In ruminant systems, postbiotic research has primarily focused on modulation of rumen fermentation efficiency and mitigation of methane emissions. Yeast-derived postbiotic metabolites from Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been shown to stabilize rumen pH, promote cellulolytic bacterial populations, and enhance volatile-fatty-acid (VFA) production, resulting in improved fiber digestibility and milk yield [40,41,42]. In addition, feeding inactivated microbial cultures has been linked to improved nitrogen utilization and reduced ruminal ammonia concentrations, reflecting more efficient microbial protein synthesis [27,28,42].

Beyond digestive effects, a growing body of evidence supports a role for postbiotics in modulating immune competence. Calves receiving yeast-derived postbiotics exhibited increased serum IgA and IgG concentrations and a reduced incidence of respiratory infections during the early postnatal period [29,30]. Collectively, these findings indicate that postbiotics can support animal health and productivity through both gut-mediated and systemic pathways.

Despite these promising outcomes, variability in host response remains an important limitation in the application of postbiotics. Emerging evidence suggests that postbiotic efficacy is influenced by baseline gut microbiome composition, which differs across species, production stages, and management systems. Animals harboring distinct microbial communities may vary in their capacity to metabolize or respond to microbial-derived metabolites, leading to heterogeneous outcomes even when identical inclusion rates are applied. This context dependency constrains the effectiveness of uniform, population-wide supplementation strategies and highlights the importance of considering baseline microbiome status when interpreting postbiotic efficacy and designing targeted intervention strategies.

3.5. Formulation and Stability Challenges

Beyond the biological and regulatory considerations outlined above, several technological and formulation-related barriers limit the commercial scalability of postbiotics. The standardization of production remains difficult because fermentation conditions, strain selection, and inactivation methods strongly influence the composition and biological activity of the final product [7]. Moreover, maintaining stability during feed processing is a major challenge, as heat and moisture can degrade volatile organic acids or peptides. Encapsulation technologies using lipid matrices, alginate beads, or spray-dried carriers have been proposed to protect postbiotic compounds and enable controlled release in the gastrointestinal tract [34,35,43,44].

Another issue involves dose optimization. Most studies have been conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, with limited data on field-scale variability and long-term safety. The interaction between postbiotics and other feed components, including minerals, phytogenics, and probiotics, also requires systematic evaluation. Finally, regulatory frameworks for postbiotics are still evolving; classification as feed additives or functional ingredients varies across jurisdictions, complicating product registration and labeling [45,46]. Taken together, these challenges underscore the need for standardized analytical markers, validated efficacy assays, and harmonized safety assessments to fully realize the potential of postbiotics as precision tools for antibiotic-free animal production.

4. Phytogenics in Animals

4.1. Composition and Bioactive Classes

Phytogenic feed additives, also described as botanicals or phytobiotics, represent a broad array of plant-derived bioactive molecules that are increasingly incorporated into animal diets to support intestinal health, nutrient utilization, immune competence, and growth performance [31]. The botanical origin, chemical extraction, and formulation route all influence their functional properties. Greathead [11] highlighted early on that plant secondary metabolites (e.g., terpenoids, polyphenols, alkaloids, saponins) may enhance animal productivity by modulating digestive processes and metabolic efficiency. Windisch et al. [10] specifically cataloged the use of phytogenic products in swine and poultry, emphasizing that essential oils and related extracts were among the most widely used classes of PFAs [47].

From a functional and chemical classification standpoint, PFAs can be divided into several principal groups:

Essential oils/volatile compounds: Typically derived from aromatic herbs/spices, these include constituents such as thymol, carvacrol, cinnamaldehyde, eugenol, menthol, and anethole. These compounds are characterized by high lipophilicity, volatility, and rapid passage through the gastrointestinal tract, allowing them to interact with microbial membranes, stimulate chemoreceptors and influence gut motility [2,7].

Phenolic/polyphenolic compounds: These include flavonoids, phenolic acids, tannins, stilbenes and other backbone structures. They tend to be less volatile, exhibit stronger antioxidant capacity, can produce complex proteins (e.g., tannins), thereby influencing digestion, and can modulate microbial metabolism [11,48].

Saponins, alkaloids, terpenoids and other secondary metabolites: Saponins may influence bile acid secretion, microbial adhesion, protozoal populations (in ruminants) and gut motility. Alkaloids and terpenoids may influence enzyme activities or signaling pathways [25,49].

Oleoresins, extract blends and encapsulated formulations: Commercial PFA products often contain a blend of multiple botanical extracts, combining essential oils + phenolics + saponins to attempt multi-mode functional effects [50,51,52,53]. The extraction method (steam-distillation, CO2 extraction, solvent extraction) and formulation (spray-dried, microencapsulated, matrix-coated) substantially affect release kinetics, stability, and bioavailability.

Because of the diversity of sources (herbs, spices, fruit extracts, tree bark, forages), the resulting variability in chemical profile is large. For example, a recent review of PFAs in poultry by Oni et al. [54] noted that compounds such as flavonoids, essential oil terpenes and saponins often co-occur in single extracts, yet their relative proportions vary widely, which complicates mechanistic attribution. In ruminants, tree/shrub forages rich in tannins and saponins (e.g., Leucaena spp., Sesbania spp.) have been used as PFA sources for methane mitigation [52]. Thus, when considering PFAs for animal diets, one must account for: plant part (leaf, seed, bark), cultivar, harvesting conditions, extraction method, formulation type, dose, and synergy with basal diet.

4.2. Mechanistic Pathways of Phytogenic Feed Additives

Phytogenic feed additives exert their functional effects through a multifaceted mechanistic network spanning microbial ecology, epithelial physiology, immune and metabolic responses, as well as rumen-specific fermentation pathways in ruminants. Below, the major mechanistic pathways are discussed in greater detail, with emphasis on emerging evidence.

Phytogenic compounds such as cinnamaldehyde, thymol and carvacrol have been shown to stimulate pancreatic enzyme secretion (amylase, lipase), increase bile acid secretion, improve fat emulsification, and enhance nutrient digestibility [10,47]. For example, a meta-analysis of PFA trials in broilers reported improved apparent digestibility of dry matter and crude protein when essential-oil blends were included [55]. In ruminants, PFAs rich in saponins and tannins have been shown to shift volatile fatty acid (VFA) profiles toward propionate rather than acetate/methane, thus improving the energetic efficiency of the host animal [52]. Improved digestibility reduces fermentative losses, lowers production of noxious fermentation metabolites, and improves feed conversion ratio (FCR).

PFAs exert both direct and indirect antimicrobial/microbiota-shaping effects. Essential oils can disrupt microbial cell membranes, inhibit ATP synthesis, and reduce toxin production by pathogenic bacteria [10,26,47]. At the same time, plant secondary metabolites may favor beneficial microbial populations (e.g., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) either by direct substrate modulation or by reducing pathogenic competition [54,56]. In poultry, for example, supplementation with a PFA reportedly increased cecal abundance of beneficial bacteria and reduced C. perfringens counts. In ruminants, PFAs have been used to suppress methanogenic archaea and protozoa populations, thereby modifying rumen fermentation and reducing methane emissions [51,52].

Maintaining intestinal (or ruminal) epithelial barrier integrity is critical for nutrient absorption and for preventing translocation of endotoxins or pathogens. PFAs have been shown to up-regulate tight-junction proteins (e.g., occludin, claudin-1, ZO-1), increase mucin production, improve villus height/crypt depth ratios, and reduce epithelial apoptosis under stress/challenge conditions [26,54]. For instance, in broilers fed a PFA, villus height increased and crypt depth decreased compared to control or antibiotic groups. These changes improve absorptive surface area and reduce gut permeability, thereby supporting better nutrient uptake and immune resilience [26].

Oxidative and chronic inflammatory stress can compromise gut integrity and feed conversion efficiency. Many phenolic/flavonoid PFA compounds act as free-radical scavengers, metal-ion chelators, and up-regulators of endogenous antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase) [57,58]. PFAs can also inhibit key pro-inflammatory signaling pathways (e.g., NF-κB, MAPK) in epithelial or immune cells, thereby reducing IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β and increasing IL-10 or TGF-β production [25]. In ruminants, supplementation with PFA reduced plasma malondialdehyde (MDA) and increased total antioxidant capacity [59]. By reducing the energy drain associated with immune activation and oxidative damage, PFAs help redirect nutrient use toward growth.

PFAs influence the mucosal immune system by modulating both innate and adaptive components. Bioactive phytochemicals may bind pattern-recognition receptors (e.g., TLR2/4, dectin-1) on dendritic cells or macrophages, biasing immune responses toward regulatory or anti-inflammatory phenotypes, enhancing secretory IgA production, increasing macrophage phagocytic activity, and supporting T-lymphocyte proliferation in GALT [25,54]. Improvement in mucosal immunity under challenge conditions leads to lower incidence of enteric infection and better resilience, even in the absence of antibiotics.

Beyond local gut effects, PFAs influence systemic metabolism. Improved nutrient digestibility and absorption increase substrate availability for growth or lactation. Some phytochemicals modulate endocrine signaling pathways (e.g., insulin sensitivity, IGF-1 axis, thyroid responsiveness) and lipid metabolism (e.g., hepatic fatty-acid oxidation, lipoprotein lipase activity) [11]. While livestock-specific mechanistic data are still emerging, findings from analogous model systems indicate that phytogenic-derived polyphenols can stimulate AMPK signaling, activate PPAR pathways, and promote mitochondrial biogenesis. These pathways are relevant to nutrient partitioning and improvements in feed efficiency [60,61,62].

In ruminants, PFAs exert additional mechanisms within the rumen ecosystem:

Suppression of ruminal protozoa, leading to reduced methane production and improved microbial-protein flow to the small intestine.

Shifting of volatile-fatty-acid profiles toward propionate at the expense of acetate/methane, thereby improving gluconeogenic precursor supply and reducing energy loss [52].

Improvement of fibrolytic-bacterial populations (cellulase, xylanase), especially under high-grain or acid-stress conditions—thus improving fiber digestibility and reducing acidosis risk.

These effects support improved nutrient capture, lower greenhouse-gas emissions and better animal performance [63].

Importantly, PFA efficacy is influenced by interactions with other feed additives (enzymes, organic acids, probiotics/postbiotics), basal diet composition (grain vs. forage, fat/protein level), animal genotype and environmental/management stressors (weaning, heat stress, pathogen load) [25,26]. Meta-analyses indicate the greatest benefits of PFAs under production-stress or challenge conditions, and diminished effect in optimal, low-stress systems [64]. Thus, deployment of PFAs may be most effective as part of a precision nutrition strategy rather than as blanket growth promoters.

4.3. Applications and Efficacy Studies

The practical application of phytogenic feed additives (PFAs) spans multiple animal species, including monogastric (poultry and swine) and ruminant (cattle, sheep, goats) systems. Their efficacy is determined by the animal’s physiology, diet composition, production stage, and environmental stressors [10,26].

In poultry, PFAs have been used as natural alternatives to antibiotic growth promoters, often showing comparable improvements in growth performance and feed efficiency [65]. In laying hens, addition of oregano oil and green-tea polyphenols improved egg production and yolk antioxidant status [66,67,68,69]. Across species, phytogenics demonstrate consistent effects on gut morphology, nutrient digestibility, antioxidant capacity, and immune responsiveness, although the magnitude of these effects varies by formulation and challenge conditions. Essential oils rich in thymol, carvacrol, and cinnamaldehyde enhance digestive enzyme secretion, reduce intestinal microbial load, and improve nutrient absorption [13,26]. Broiler studies report increased body weight gain, improved feed conversion ratio (FCR), and enhanced intestinal morphology, characterized by greater villus height and reduced crypt depth, following inclusion of blended phytogenic formulations [25,54].

In swine, phytogenic supplementation during post-weaning reduces diarrhea incidence and stabilizes gut microbiota [70,71]. Cinnamaldehyde and eugenol have been shown to decrease coliform counts and improve ileal digestibility [10]. Inclusion of 100–300 mg/kg essential oil blends improved daily gain and modulated immune markers such as IL-10 and IgA [72].

In ruminants, PFAs have been applied mainly to improve rumen fermentation and nutrient efficiency. Essential oils, tannins, and saponins modulate rumen microbial populations, suppress protozoa and methanogens, and enhance cellulolytic bacterial activity [15,49,52]. Supplementation with carvacrol, thymol, or eugenol has been associated with reduced methane production and increased propionate proportion in volatile-fatty-acid profiles, enhancing energy utilization [73]. In dairy cows, PFA inclusion improved milk yield, altered milk fatty-acid composition, and decreased somatic cell counts [74]. Feedlot trials have also shown increased average daily gain and improved carcass yield when PFAs were included at 250–500 mg/kg feed [75].

Beyond terrestrial livestock, phytogenic feed additives have also been evaluated in aquaculture and other non-monogastric production systems. Recent studies in aquaculture indicate that PFAs may enhance growth and disease resistance in fish and shrimp by modulating intestinal microbiota and reducing oxidative stress [76,77]. In laying hens, addition of oregano oil and green-tea polyphenols improved egg production and yolk antioxidant status [66]. Across species, phytogenics demonstrate consistent effects on gut morphology, nutrient digestibility, antioxidant capacity, and immune responsiveness, although the magnitude of these effects varies by formulation and challenge conditions [68,69,78,79,80].

4.4. Challenges and Limitations

Despite their potential, the widespread and consistent use of phytogenic feed additives (PFAs) in livestock systems faces several challenges related to variability, stability, regulatory classification, and economic return. The chemical composition of phytogenics extracts depends strongly on plant species, genotype, growth conditions, harvest time, extraction method, and storage [3]. Even within a single botanical source, the concentration of bioactive compounds can vary by up to an order of magnitude, complicating dose determination and limiting reproducibility across studies and production systems. The lack of standardization remains a major barrier to consistent efficacy, underscoring the need for harmonized analytical approaches such as GC–MS fingerprinting and HPLC profiling to ensure quality control and batch-to-batch consistency [32,33].

Essential oils, which constitute a major class of PFAs, are volatile and prone to degradation during feed pelleting and storage. Microencapsulation using lipid matrices, starch, or alginate has been shown to improve stability and enable more targeted release in the gastrointestinal tract [20,34]. However, encapsulation increases formulation costs, and release kinetics vary substantially depending on the carrier material. In addition, interactions with dietary fat, fiber, and minerals can influence absorption and biological activity [2], while bioavailability data for many phytogenics compounds remain limited.

Optimal inclusion levels of PFAs vary widely, typically ranging from 50 to 500 mg/kg for essential-oil blends and from 0.5% to 2% for tannin-rich extracts, with performance responses often exhibiting nonlinear or hormetic behavior [35,81]. Reported benefits are frequently more pronounced under conditions of pathogen challenge or environmental stress, whereas responses under optimal production conditions are inconsistent [19]. Excessive dosages may exert pro-oxidant or antinutritional effects, particularly in the case of high-tannin formulations [6], further emphasizing the importance of careful dose optimization.

Regulatory classification of PFAs also differs across jurisdictions. In the European Union, many phytogenics are categorized as sensory or flavoring additives, whereas in the United States they are generally treated as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) ingredients [82]. These regulatory inconsistencies complicate global market development and limit the scope of functional label claims. Toxicological evaluation and residue monitoring remain particularly important for compounds such as allicin or thymol that share metabolic pathways with human therapeutic agents.

Although PFAs can improve animal performance, their economic viability depends on whether gains in feed efficiency or productivity outweigh costs associated with raw material sourcing, extraction, and formulation. A recent techno-economic analysis indicated that a 1–2% improvement in feed efficiency may justify additional costs under conditions of high feed prices, but may not be sufficient in low-margin production systems [34]. Integration with circular bioeconomy strategies, such as recovery of bioactive compounds from agro-industrial by-products, represents a potential pathway to improve sustainability and reduce costs.

Critical research gaps remain in defining dose–response relationships, identifying reliable bioavailability markers, elucidating molecular targets, and evaluating long-term effects on animal health and welfare. Omics-based approaches, including metabolomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, are increasingly necessary to resolve the biological pathways underlying observed phenotypes and to support more predictive formulation strategies [83,84]. In parallel, large-scale field trials using standardized formulations are required to confirm reproducibility under commercial conditions.

Similarly to postbiotics, biological responses to phytogenic feed additives display substantial inter-individual and group-level variability. Differences in baseline microbiome composition, digestive physiology, and metabolic capacity can influence the bioavailability and microbial biotransformation of plant-derived compounds, leading to heterogeneous performance outcomes across production systems. In particular, microbiome-mediated metabolism of polyphenols, terpenoids, and other phytochemicals may vary depending on resident microbial populations, thereby affecting both efficacy and dose–response behavior. Collectively, these factors limit the effectiveness of standardized inclusion rates and highlight the inherent constraints of a one-size-fits-all approach, reinforcing the need for precision nutrition strategies that account for host and microbiome context.

5. Safety, Tolerance, and Risk Considerations of Phytogenic Feed Additives and Postbiotics

While postbiotics and phytogenic feed additives are widely regarded as safe alternatives to antibiotic growth promoters, their biological activity necessitates careful consideration of dose, duration, and species-specific tolerance. Unlike probiotics, postbiotics consist of non-viable microbial cells or metabolites, eliminating risks associated with microbial translocation or antibiotic resistance gene transfer; however, excessive exposure to bioactive metabolites may still perturb gut homeostasis [6,22].

SCFAs, particularly butyrate, are central mediators of postbiotic functionality, but their effects are dose dependent. At physiological concentrations, butyrate supports epithelial integrity and anti-inflammatory signaling; at excessive levels, it may induce epithelial hyperproliferation or disrupt normal cell differentiation patterns [27,85]. Similarly, strong immunostimulatory components such as lipoteichoic acids and peptidoglycan fragments may overstimulate innate immune pathways if not appropriately formulated [7].

Phytogenic feed additives also exhibit hormetic behavior. Essential oils and polyphenols exert antimicrobial and antioxidant effects at low to moderate inclusion rates, yet higher concentrations may suppress beneficial commensal bacteria, reduce feed intake due to palatability issues, or exert pro-oxidant activity [10,49]. Tannin- and saponin-rich extracts, commonly used in ruminant systems, may impair protein digestibility or mineral absorption when inclusion thresholds are exceeded [49].

Safety evaluations therefore require a dose–response framework, incorporating no-observed-adverse-effect levels (NOAELs), species-specific digestive physiology, and production stage. Long-term and multigenerational exposure studies remain limited, particularly regarding immune tolerance, microbiome resilience, and potential interactions with vaccines or therapeutic interventions. These considerations highlight the importance of precision formulation and regulatory harmonization to ensure that bioactive feed additives deliver consistent benefits without unintended physiological consequences.

6. Synergistic and Combined Use of Postbiotics and Phytogenics

6.1. Conceptual Framework and Rationale

The concurrent use of postbiotics and phytogenics represents a logical evolution of functional feed additive research. Both categories are grounded in the principle of host–microbiome modulation, yet they differ fundamentally in origin and molecular composition. Postbiotics comprise microbial metabolites or inactivated cells, whereas phytogenics supply plant-derived bioactive molecules [25,45]. When administered together, these two additive classes can provide complementary or even synergistic benefits: postbiotics stabilize microbial communities and strengthen epithelial defenses from within, while phytogenics mitigate oxidative stress and inhibit pathogens from without.

Recent feeding trials have begun to explore such dual-additive systems. Combined supplementation of yeast-derived postbiotics with essential-oil blends in broilers improved body-weight gain, villus height, and serum immunoglobulin concentrations more effectively than either additive alone [26,86]. Similarly, in weaned piglets, mixtures of bacterial fermentation postbiotics and oils from phytogenics reduced E. coli colonization and enhanced jejunal tight-junction protein expression [13,87,88]. These findings indicate a functional convergence between microbial- and botanical-derived bioactives that enhances gut homeostasis and nutrient utilization.

6.2. Mechanistic Interactions and Complementarity

Postbiotic components such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bacteriocins, and cell-wall fragments selectively promote beneficial commensals while suppressing enteric pathogens [7,9]. Phytogenics such as phenolics and terpenoids disrupt microbial membranes and interfere with quorum-sensing signals [10,47,89,90]. Together, they produce a two-tiered antimicrobial shield: postbiotics remodel the microbiome through ecological pressure, while phytogenics directly weaken pathogen viability. Multi-omics analyses of broiler microbiota have confirmed that such combinations increase the relative abundance of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium while decreasing Clostridium and Salmonella genera [91,92,93].

A central point of functional convergence between postbiotics and phytogenics is their capacity to reinforce intestinal epithelial barrier integrity while simultaneously modulating mucosal immune responses [7,25]. As described earlier, the intestinal barrier functions as a dynamic epithelial interface that regulates permeability and immune signaling. This regulation is mediated primarily by tight junction proteins, including occludin, claudins, and zonula occludens proteins such as ZO-1, which control paracellular permeability and prevent the translocation of pathogens and endotoxins into the systemic circulation [27,29].

Postbiotic components, particularly short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate and acetate, play a pivotal role in barrier reinforcement by serving as energy substrates for enterocytes and by regulating epithelial differentiation and renewal [85,94]. Butyrate further enhances epithelial integrity through epigenetic modulation, including histone-deacetylase inhibition, leading to up-regulation of tight-junction protein expression and mucin synthesis [27]. In addition, microbial-derived exopolysaccharides and cell-wall fragments interact with pattern-recognition receptors such as TLRs 2/4 and NOD-like receptors, activating controlled signaling cascades that reinforce epithelial cohesion without triggering excessive inflammation [7,9].

Phytogenic feed additives complement these effects by attenuating oxidative and inflammatory stress at the epithelial surface. Phenolic compounds and essential-oil constituents suppress activation of pro-inflammatory pathways, including NF-κB and MAPK signaling, thereby limiting cytokine-mediated disruption of tight junctions [25,26]. Concurrently, phytogenic antioxidants enhance endogenous redox defenses through up-regulation of enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, preserving epithelial structure under nutritional, thermal, or pathogenic stress [57,58].

When administered together, postbiotics and phytogenics exert additive or synergistic effects on gut barrier resilience. Postbiotics provide trophic and signaling support along the microbiome–epithelium axis, while phytogenics reduce oxidative damage and microbial pressure at the luminal interface [10,45]. This coordinated action reduces intestinal permeability, dampens immune overactivation, and lowers the energetic cost of inflammation, thereby redirecting nutrients toward growth and productive functions. Such barrier–immune cross-talk provides a mechanistic foundation for the enhanced performance and resilience reported in combined supplementation strategies [13,26].

Beyond local gut effects, both additive classes influence host metabolism. SCFAs derived from postbiotics activate G-protein-coupled receptors (GPR41/43) and modulate insulin sensitivity, while phytogenic polyphenols enhance lipid oxidation and mitochondrial function through PPAR-α and AMPK pathways [11,94,95,96,97,98]. Metabolomic analyses indicate that animals receiving combined supplementation show elevated circulating propionate, reduced plasma malondialdehyde, and higher antioxidant enzyme activities [27,52]. These data underscore metabolic convergence toward improved nutrient utilization and oxidative balance.

In ruminants, synergistic effects are expressed within the rumen ecosystem. Yeast-derived postbiotics contribute to stabilization of rumen pH, stimulation of cellulolytic bacterial populations, and enhanced volatile fatty acid production [41]. Concurrently, phytogenic feed additives rich in tannins, saponins, and essential oils can modulate protozoal and methanogenic populations, leading to reduced methane output and improved nitrogen utilization [74]. Integrated feeding strategies that combine both additive classes have been associated with improved fiber digestibility, increased milk yield, and reduced enteric emissions under experimental conditions [34].

Despite the growing body of experimental evidence, commercial adoption remains constrained by variable cost–benefit outcomes across production systems, region-specific regulatory frameworks, and differences in producer acceptance. These barriers are particularly relevant in systems with narrow economic margins or where additive claims are limited by regulatory classification.

7. Insights from Omics and Systems Biology

7.1. Advances in Omics Technologies and Systems-Level Understanding

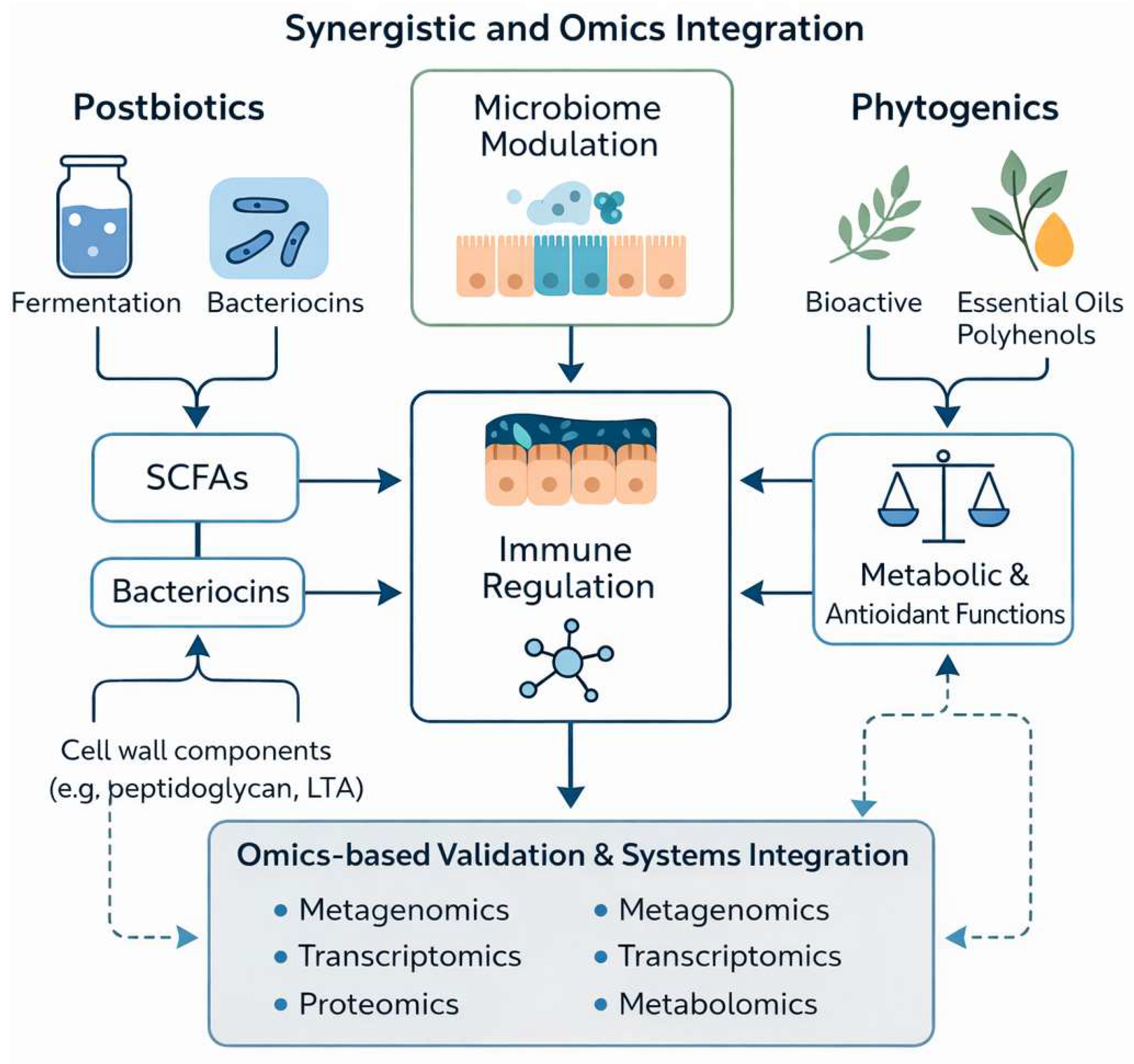

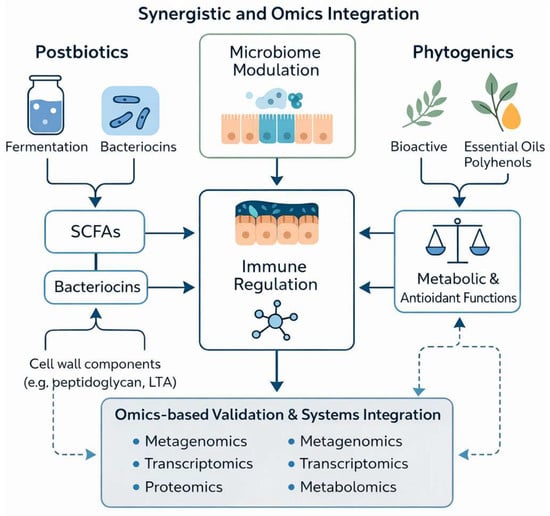

Advances in omics technologies, including metagenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, have substantially advanced the understanding of how postbiotics and phytogenics interact with the gut ecosystem. Earlier evaluations of these additives largely relied on empirical performance indicators such as growth rate, feed efficiency, or health status [2]. While informative, such outcomes provided limited insight into the biological mechanisms underlying observed responses. In contrast, integrated omics approaches now allow detailed interrogation of causal relationships linking additive composition, microbiome restructuring, metabolite production, and host physiological responses [99,100]. This shift supports a systems-nutrition perspective in which the gut is viewed as an active microbial–host interface shaped by coordinated metabolic, immune, and signaling networks rather than as a passive site of digestion.

Metagenomic analyses indicate that combined postbiotic–phytogenic supplementation modulates functional microbial gene clusters associated with short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) synthesis, amino-acid metabolism, and antioxidant defense pathways [101,102]. These functional shifts extend beyond changes in microbial abundance and suggest remodeling of microbial metabolic capacity. Complementary metabolomic profiling further demonstrates enrichment of biologically relevant metabolites, including butyrate, acetate, and phenolic derivatives, which support epithelial energy metabolism and redox balance [103]. At the host level, transcriptomic studies consistently report upregulation of genes involved in epithelial barrier maintenance, such as MUC2 and TJP1, alongside downregulation of inflammatory mediators including NF-κB and COX-2, providing molecular evidence for enhanced barrier integrity and immune homeostasis.

The integration of metagenomic, metabolomic, and transcriptomic datasets through systems-biology frameworks enables the identification of interaction patterns and predictive biomarkers associated with gut health and performance outcomes (Figure 2). Such integrative analyses move the field beyond descriptive associations toward mechanistic interpretation, allowing coordinated responses across the microbiome–epithelium–metabolic axis to be mapped in a biologically coherent manner. This approach is increasingly recognized as a critical step in the development of precision-formulated, species-specific feed additive strategies [104,105].

Figure 2.

Systems-level integration of postbiotics and phytogenics validated by metagenomic, metabolomic, and transcriptomic evidence across the microbiome–epithelium–metabolic axis in livestock.

Within this mechanistic context, the practical considerations summarized earlier (Table 1) can be more clearly interpreted. Postbiotics appear to provide relatively consistent immunomodulatory and epithelial-support functions, whereas phytogenics contribute dose-dependent antimicrobial and antioxidant effects. When used in combination, these additive classes support multi-axis regulation of gut function that is particularly relevant under conditions of environmental stress, dietary challenge, or microbial instability. Omics-derived evidence therefore reinforces the rationale for context-dependent, precision deployment of postbiotic–phytogenics strategies rather than uniform inclusion across production systems.

7.2. Metagenomics: Decoding Microbial Restructuring

Metagenomic sequencing provides insight into how postbiotic and phytogenic supplementation reshapes microbial community structure and gene function. In broilers, combined postbiotic-phytogenic supplementation increased the abundance of Lactobacillus reuteri and Bifidobacterium animalis, taxa associated with improved SCFA production and mucosal defense [106]. Functional gene profiling revealed enrichment of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZy families GH13 and GH43) and butyrate-synthesis pathways, consistent with enhanced fermentative energy yield [18,107,108]. In ruminants, metagenomic studies have shown reduced expression of archaeal mcrA genes and protozoal rRNA sequences when essential oils were co-fed with yeast-derived postbiotics, indicating suppression of methanogenic consortia [74]. Such microbial-gene-level insights explain observed reductions in methane and improvements in volatile-fatty-acid profiles [73].

7.3. Metabolomics: Mapping Biochemical Intermediates

Metabolomic profiling bridges microbial gene activity with host physiology. Nuclear-magnetic-resonance and mass-spectrometry analyses have revealed that animals receiving postbiotic-phytogenics blends exhibit elevated intestinal concentrations of butyrate, acetate, and propionate, coupled with lower lactate and ammonia levels [7,27]. These SCFAs fuel colonocytes, regulate epithelial tight junctions, and signal through G-protein-coupled receptors to influence insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism [22]. Concurrently, phytogenic polyphenols and terpenoids contribute antioxidative metabolites such as ferulic and caffeic acids, which scavenge free radicals and modulate redox signaling [57]. Integrated metabolic pathway reconstruction demonstrates that these additive combinations create a metabolite landscape that favors energy efficiency and immune tolerance.

7.4. Transcriptomic and Proteomic Validation of Host Responses

While the mechanistic roles of postbiotics and phytogenics in epithelial reinforcement and immune modulation are described in Section 4.2. transcriptomic and proteomic approaches provide molecular-level validation of these effects and link phenotypic outcomes with underlying biological pathways [18,20]. These omics technologies enable direct assessment of host gene and protein expression in response to functional feed additives.

Transcriptomic analyses of intestinal tissues from poultry and swine receiving combined postbiotic–phytogenic supplementation consistently demonstrate up-regulation of genes associated with epithelial barrier function, including TJP1 (ZO-1), CLDN1, and OCLN, alongside increased expression of mucin-encoding genes such as MUC2 [18,109,110]. These transcriptional changes correspond with histological findings of increased villus height, reduced crypt depth, and improved epithelial continuity reported in feeding trials [25,26]. Concurrently, the downregulation of pro-inflammatory mediators, including IL-1β, TNF-α, and NF-κB-related transcripts, indicates suppression of inflammatory signaling pathways that would otherwise compromise tight junction integrity [25,45].

Proteomic studies further corroborate these responses by identifying increased abundance of proteins involved in epithelial structure, stress tolerance, and antioxidant defense, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, and heat-shock proteins [74,93]. In ruminant systems, proteomic profiling of intestinal and hepatic tissues following supplementation with yeast-derived postbiotics and essential-oil-based phytogenics has revealed shifts toward proteins associated with mitochondrial respiration, lipid oxidation, and energy metabolism, suggesting systemic benefits linked to improved gut functionality [74,102].

Notably, these molecular adaptations are more pronounced under combined supplementation than with either additive class alone, supporting the concept of functional synergy [26,74]. By integrating transcriptomic and proteomic evidence, omics-based validation confirms that improvements in gut integrity and immune homeostasis are underpinned by coordinated host-response signatures rather than isolated phenotypic observations [96,97,98]. This mechanistic substantiation enhances the translational relevance of postbiotic–phytogenics strategies and supports their application within precision-nutrition frameworks for antibiotic-free livestock production [106,111,112].

7.5. Systems-Biology Modeling and Predictive Analytics

Integration of multi-omics datasets through network modeling enables quantitative prediction of additive responses. Computational frameworks that combine microbial abundance, metabolite fluxes, and host transcriptomics have begun to identify predictive biomarkers such as the ratio of Lactobacillus to Enterobacteriaceae, fecal butyrate concentration, and plasma antioxidant capacity, which correlate with feed efficiency outcomes [106,113]. Machine-learning approaches, including random-forest and Bayesian network models, now permit prediction of additive synergy based on chemical composition and microbiome baseline [114]. Such predictive analytics facilitate precision formulation, allowing nutritionists to match specific postbiotics–phytogenics blends to the microbiome state of target populations, thereby improving reproducibility across herds and production systems.

7.6. Integrative Outlook

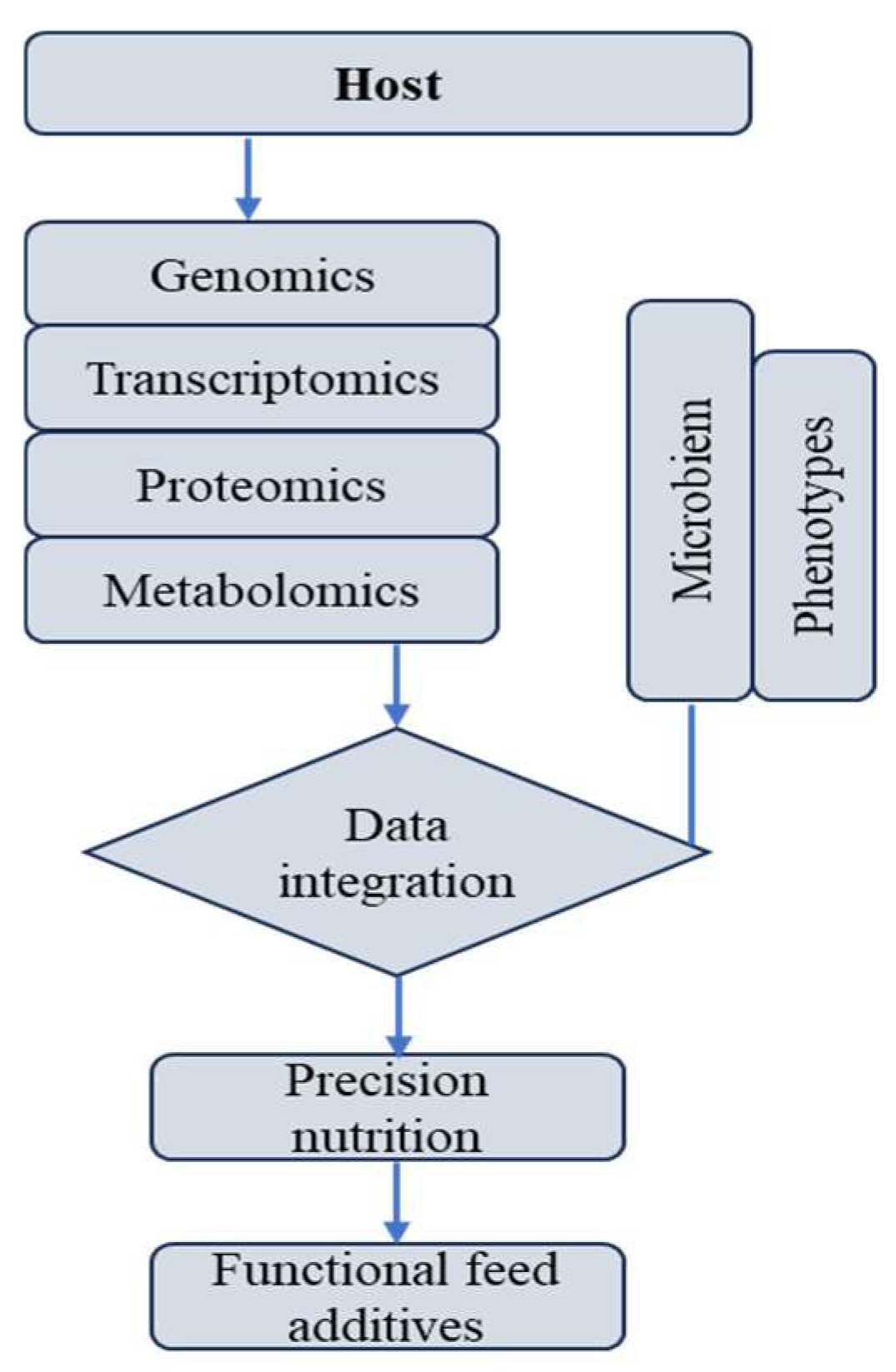

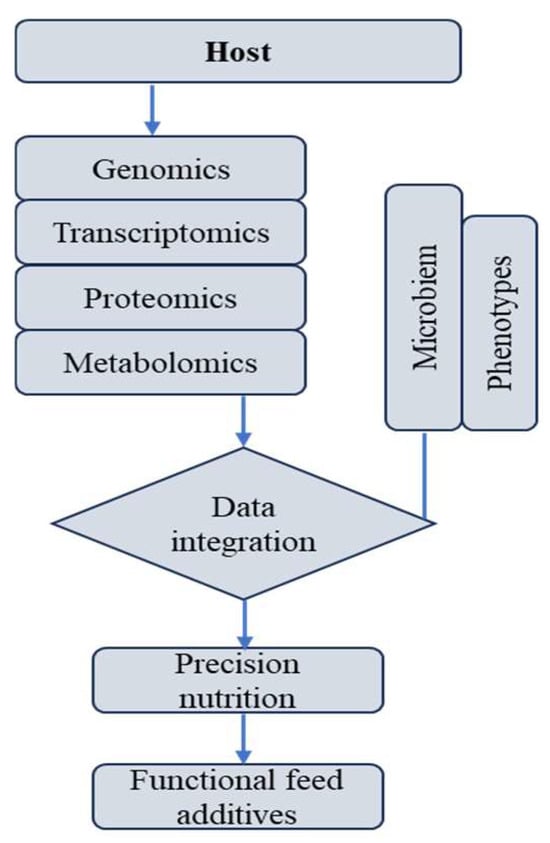

Omics-driven approaches are redefining functional-feed-additive research from descriptive trials to mechanistic precision science. By coupling high-resolution molecular data with physiological and performance endpoints, researchers can identify causal relationships and refine additive design. Future integration of metatranscriptomics, metabolite fluxomics, and spatial imaging (e.g., MALDI-MSI) will further illuminate tissue-specific additive responses. Ultimately, a systems-biology understanding of postbiotic-phytogenics interactions will enable data-driven, adaptive nutrition strategies that support sustainable productivity, reduced antibiotic use, and improved animal welfare (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Multi-omics-guided precision nutrition model for functional feed additives.

8. Future Directions and Research Gaps

8.1. Integrative Framework for Next-Generation Functional Additives

Although considerable progress has been made in understanding postbiotics and phytogenics, the field remains at an early stage of translation from empirical feeding trials to precision-engineered functional nutrition. Future research must adopt an integrative framework that couples multi-omics data, mechanistic modeling, and animal-level performance indicators to delineate causality rather than correlation. This approach will help overcome variability across studies [25,115]. Developing computational “nutribiome” models that simulate additive-host–microbiome interactions will allow hypothesis-driven formulation design and rapid screening of synergistic combinations. When validated experimentally, such in silico–to–in vivo pipelines could reduce dependency on long feeding trials and accelerate discovery of sustainable antibiotic alternatives.

8.2. Standardization, Reproducibility, and Regulatory Alignment

A persistent limitation is the lack of standardization in additive characterization. Bioactive content in plant extracts or microbial metabolites varies widely with raw-material source, extraction process, and storage [12,73,116,117]. Harmonized quality control frameworks, including chromatographic fingerprinting using HPLC and GC–MS, bioactivity assays, and validated potency metrics, are critical for reproducibility and cross-study comparison.

Regulatory alignment is equally pressing. Currently, postbiotics and phytogenics are variably classified as feed additives, flavoring agents, or functional ingredients depending on jurisdiction [22,74]. A unified global regulatory standard that recognizes their mechanistic mode of action, rather than focusing solely on origin, would streamline market authorization and encourage innovation while safeguarding animal and consumer health.

8.3. Multi-Omics Integration and Precision Nutrition

Omics-driven research should progress beyond single-layer datasets toward multi-omics integration, combining metagenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics within systems-biology models [118,119]. For instance, correlating microbial functional genes with host gene-expression networks can identify additive-responsive biomarkers such as mucin-gene up-regulation or butyrate-pathway activation.

Precision nutrition platforms could then utilize these biomarkers to predict individual or herd-level responses, tailoring additive blends according to microbiome composition, production stage, or environmental stressors [120]. Such predictive personalization, supported by machine learning, represents the next frontier in functional feed additive science—moving from universal inclusion rates to adaptive, data-guided supplementation.

8.4. Sustainable Sourcing and Circular Bioeconomy Approaches

Future development must also address sustainability. Many phytogenic compounds are extracted from high-value crops or imported botanicals, raising concerns about environmental footprint and supply security. Circular bioeconomy models that recover phenolics, terpenes, and organic acids from agro-industrial by-products such as fruit peels and distillery residues offer a sustainable alternative [52]. Similarly, postbiotics derived from fermentation side-streams or valorized microbial biomass can reduce waste while providing cost-effective functional ingredients. Integrating life-cycle assessment (LCA) into additive evaluation will ensure that future formulations align with climate-neutral livestock production goals.

8.5. Host–Microbiome Development and Welfare Outcomes

Beyond productivity, postbiotics and phytogenics may influence animal welfare and resilience through modulation of the gut–brain and gut–immune axes. Emerging evidence links microbial metabolites and polyphenols to neuroendocrine signaling, stress reduction, and behavior regulation [7,27]. Future research should examine how additive supplementation shapes behavioral phenotypes, thermal tolerance, and disease recovery. Integrating physiological, behavioral, and omics data will clarify whether improvements in feed efficiency also correspond to genuine welfare benefits.

8.6. Translational and Field-Scale Validation

Most mechanistic studies remain limited to laboratory or pilot-scale settings. Large-scale, longitudinal field trials under commercial conditions are urgently needed to validate mechanistic findings, quantify economic returns, and assess long-term safety. Such trials should employ harmonized endpoints, including growth metrics, microbiota composition, immune biomarkers, and environmental outputs such as methane and nitrogen, to support meta-analytic integration across species and regions [73]. Furthermore, collaborative networks among academia, industry, and regulatory agencies are essential to share data and establish open-access repositories for additive performance and composition profiles. This will accelerate progress toward evidence-based, reproducible feed-additive innovation.

8.7. Concluding Perspective

The synergistic interplay between postbiotics and phytogenics offers a credible pathway toward sustainable, antibiotic-independent livestock systems. By uniting multi-omics insights, precision-nutrition algorithms, and circular-bioeconomy sourcing, the next generation of functional feed additives can transcend traditional paradigms of growth promotion to deliver comprehensive animal health, productivity, and environmental stewardship. Achieving this will require interdisciplinary collaboration across microbiology, chemistry, animal physiology, data science, and policy to translate molecular insights into scalable, field-ready solutions.

8.8. Performance Variability and Context-Dependent Efficacy

Despite promising outcomes, the performance benefits of postbiotics and phytogenics are not universal across production systems. Meta-analyses and field trials indicate that responses are often context dependent, with the greatest benefits observed under conditions of nutritional imbalance, environmental stress, pathogen challenge, or early-life developmental stages [25,64]. In high-performing herds or flocks with optimal hygiene and balanced diets, improvements in feed conversion ratio or growth rate may be marginal and economically insignificant. Furthermore, baseline microbiome composition strongly influences responsiveness; animals with resilient, mature microbial ecosystems may exhibit limited modulation following supplementation [121,122]. This variability underscores the importance of targeted application rather than blanket inclusion.

Economic analyses also suggest diminishing returns when additive costs exceed gains from small improvements in feed efficiency, particularly in low-margin production systems [10]. Consequently, future application strategies should integrate microbiome diagnostics, stress profiling, and production-stage considerations to maximize cost-effectiveness and biological relevance.

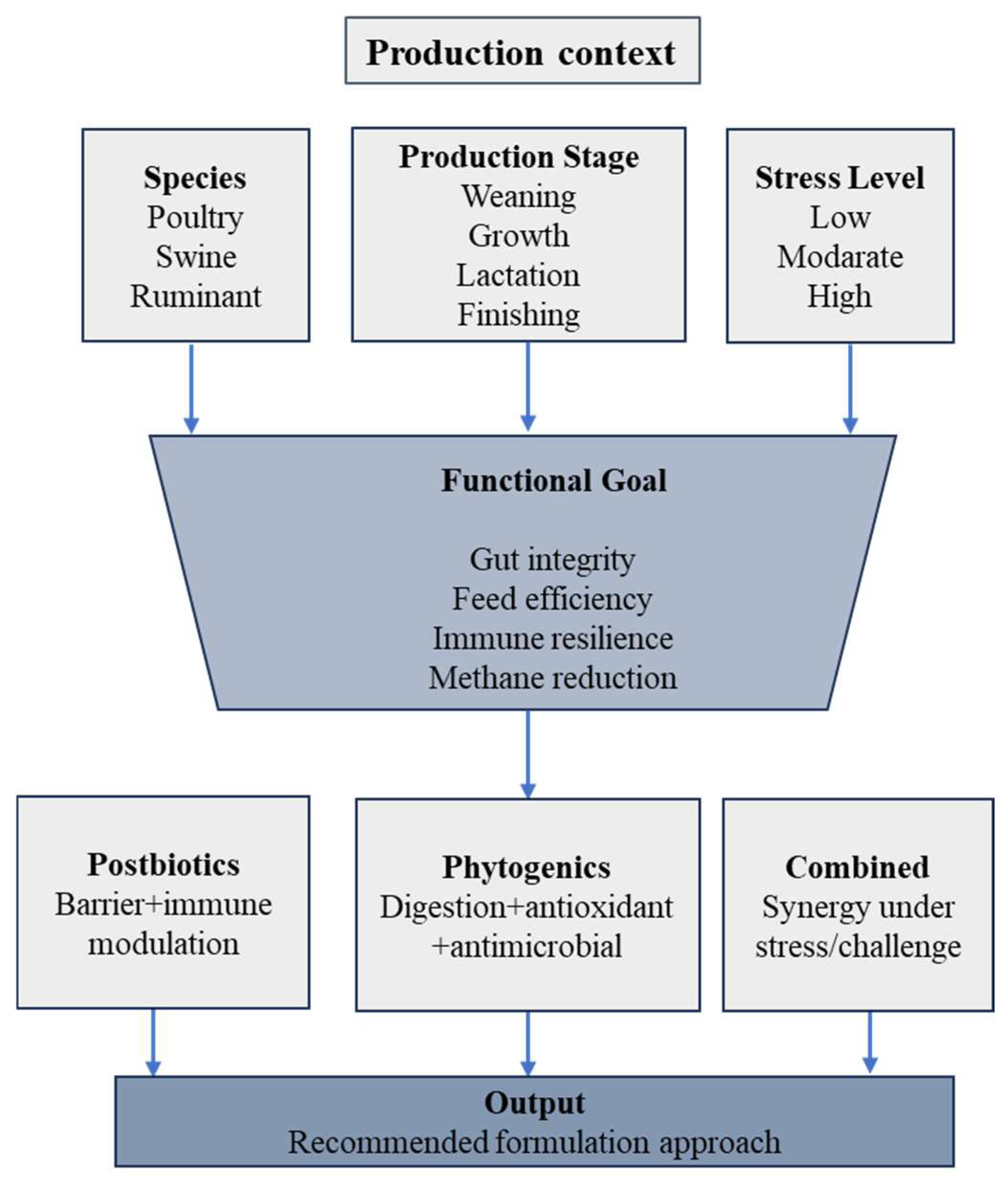

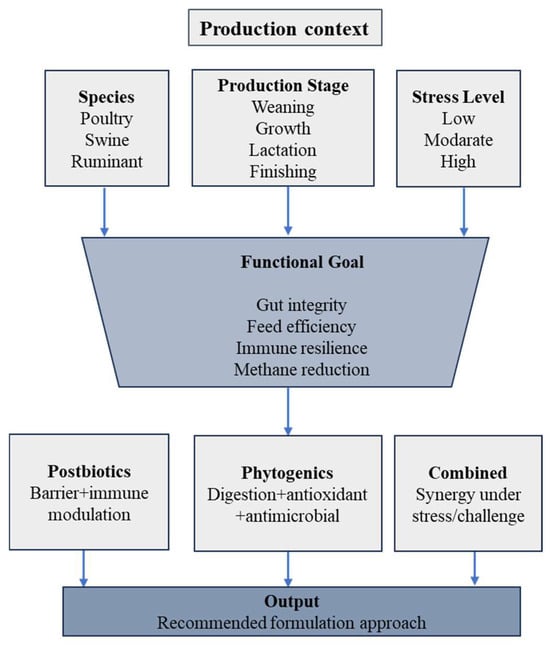

8.9. Commercial Readiness and Industrial Translation

From an applied-science standpoint, postbiotics and phytogenics have progressed beyond experimental concepts toward commercially viable feed technologies. Several postbiotic categories, such as yeast fermentation products and bacterial cell-free metabolites, are already incorporated into commercial diets for poultry, swine, and ruminants, demonstrating consistent performance under pelleted feed conditions [22,102]. Figure 4 provides a conceptual visualization of how the practical considerations outlined in Table 1 can be integrated into context-specific deployment strategies.

Figure 4.

Conceptual decision framework illustrating context-dependent deployment of postbiotics and phytogenics across production stages, stress conditions, and livestock systems.

Phytogenic feed additives are similarly well established in global markets, particularly as flavoring and sensory additives, although their functional claims often exceed what is permitted under current regulatory labeling frameworks [2]. Advances in encapsulation and co-formulation technologies now enable more precise synchronization of release profiles between microbial-derived and botanical bioactives, thereby enhancing efficacy while reducing losses associated with volatility during feed processing [20]. Key barriers to broader adoption nonetheless remain, including variability in production costs, supply chain stability of botanical raw materials, and inconsistent regulatory classification across regions. Addressing these challenges will require closer collaboration among academia, industry, and regulatory bodies, as well as transparent reporting of additive composition and efficacy in commercial-scale trials.

Beyond technological and formulation-related considerations, the economic viability and large-scale adoption of functional feed additives are also influenced by producer organizational and market structures. Recent evidence indicates that participation in agricultural cooperatives can significantly enhance livestock farm profitability by improving access to shared resources, technical knowledge, and market channels. For example, an empirical analysis of the beef cattle sector in China demonstrated that cooperative membership increased profitability across both small-scale and large-scale operations, in part by reducing financial risk and facilitating technology uptake [123]. Such organizational models may therefore play an enabling role in the adoption of precision nutrition strategies, particularly for postbiotics and phytogenics, which often require upfront investment, coordinated feeding practices, and large-scale validation. Encouraging cooperative or collective production frameworks could help lower perceived economic barriers and accelerate the translation of these functional additives into commercial farming systems, especially among smallholder producers.

In addition to production-level outcomes, future research should also consider the potential indirect implications of postbiotic and phytogenic feed additives for human health within a One Health framework. By improving gut health, immune resilience, and reducing reliance on in-feed antimicrobials, these additives may indirectly influence food safety, antimicrobial resistance dynamics, and the nutritional and bioactive profiles of animal-derived products consumed by humans. Integrating animal, environmental, and human health perspectives will be essential for fully evaluating the broader societal impact of these functional feed strategies.

9. Conclusions and Practical Implications

The transition toward antibiotic-free livestock production has catalyzed a paradigm shift in feed additive science, moving from single-purpose growth promotion toward multifunctional modulation of gut health, immunity, and metabolism. Within this evolving framework, postbiotics and phytogenics have emerged as two of the most promising natural additive classes, exerting complementary effects through microbial-derived metabolites that stabilize the gut ecosystem and modulate host immunity, and plant-based bioactives that enhance digestion, mitigate oxidative stress, and suppress pathogens. The evidence reviewed demonstrates that these additives, applied individually or in combination, can improve nutrient utilization, reinforce epithelial integrity, and reduce inflammatory burden, thereby enhancing growth performance and welfare across monogastric and ruminant species, with synergistic formulations showing superior efficacy under environmental or pathogenic stress conditions. Advances in systems biology, including multi-omics and network modeling approaches, have begun to elucidate the molecular and microbial pathways underlying these effects, bridging the gap between empirical feeding trials and mechanistic understanding and enabling identification of biomarkers that support precision nutrition tailored to species, production stage, and microbiome state. From a practical perspective, successful translation into commercial application will depend on robust formulation and delivery strategies, harmonized standardization and regulatory frameworks, favorable cost–benefit and sustainability profiles supported by circular bioeconomy approaches, and large-scale field validation under commercial conditions. Overall, the strategic integration of postbiotics and phytogenics represents a holistic and evidence-based approach to sustainable animal nutrition that extends beyond conventional antibiotic replacement, with continued interdisciplinary collaboration being essential for advancing precision livestock production.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Brower, C.; Gilbert, M.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Robinson, T.P.; Teillant, A.; Laxminarayan, R. Global Trends in Antimicrobial Use in Food Animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5649–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, B.M.; Levy, S.B. Food Animals and Antimicrobials: Impacts on Human Health. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 718–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluske, J.R.; Turpin, D.L.; Kim, J.-C. Gastrointestinal Tract (Gut) Health in the Young Pig. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 4, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowiak, P.; Śliżewska, K. Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on Human Health. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntsongota, Z.; Ikusika, O.; Jaja, I.F. The Role of Phytogenic Feed Additives in Growth and Immune Response in Livestock Production: A Global Systematic Review. Front. Anim. Sci. 2025, 6, 1703112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinderola, G.; Druart, C.; Gosálbez, L.; Salminen, S.; Vinot, N.; Lebeer, S. Postbiotics in the Medical Field under the Perspective of the ISAPP Definition: Scientific, Regulatory, and Marketing Considerations. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1239745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Toalá, J.E.; Garcia-Varela, R.; Garcia, H.S.; Mata-Haro, V.; González-Córdova, A.F.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B.; Hernández-Mendoza, A. Postbiotics: An Evolving Term within the Functional Foods Field. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 75, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani, N.; Soleimani, R.A.; Homayouni-Rad, A. Potential of Postbiotics for the Biodegradation of Xenobiotics: A Review. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2025, 21, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokryazdan, P.; Faseleh Jahromi, M.; Liang, J.B.; Ho, Y.W. Probiotics: From Isolation to Application. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2017, 36, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windisch, W.; Schedle, K.; Plitzner, C.; Kroismayr, A. Use of Phytogenic Products as Feed Additives for Swine and Poultry1. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, E140–E148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greathead, H. Plants and Plant Extracts for Improving Animal Productivity. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, Z.D.; Bošnjak-Neumüller, J.; Pajić-Lijaković, I.; Raj, J.; Vasiljević, M. Essential Oils as Feed Additives—Future Perspectives. Molecules 2018, 23, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemipour, H.; Kermanshahi, H.; Golian, A.; Veldkamp, T. Effect of Thymol and Carvacrol Feed Supplementation on Performance, Antioxidant Enzyme Activities, Fatty Acid Composition, Digestive Enzyme Activities, and Immune Response in Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, L.O.; Muir, J.P.; Naumann, H.D.; Norris, A.B.; Ramírez-Restrepo, C.A.; Mertens-Talcott, S.U. Nutritional Aspects of Ecologically Relevant Phytochemicals in Ruminant Production. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 628445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.; Choudhuri, I.; Paria, P.; Samanta, A.; Khanra, K.; Chakraborty, A. Phytochemicals as Potential DNA Polymerase β Inhibitors for Targeted Ovarian Cancer Therapy: An In-Silico Approach. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia 2024, 21, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Shand, H.; Manna, A.; Bose, D.; Some, S.; Mondal, R. Ethnopharmacological and Nutritional Insights into Wild Leafy Vegetables: Implications for Food Security, Nutraceutical Potential, and Environmental Remediation. Discov. Plants 2024, 1, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegh, C.A.M.; Geerlings, S.Y.; Knol, J.; Roeselers, G.; Belzer, C. Postbiotics and Their Potential Applications in Early Life Nutrition and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandohee, J.; Basu, R.; Dasgupta, S.; Sundarrajan, P.; Shaikh, N.; Patel, N.; Noor, A. Applications of Multi-Omics Approaches for Food and Nutritional Security. In Sustainable Agriculture in the Era of the OMICs Revolution; Prakash, C.S., Fiaz, S., Nadeem, M.A., Baloch, F.S., Qayyum, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 103–118. ISBN 978-3-031-15568-0. [Google Scholar]

- Becchi, P.P.; Rocchetti, G.; Lucini, L. Advancing Dairy Science through Integrated Analytical Approaches Based on Multi-Omics and Machine Learning. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2025, 63, 101289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, Y.; Seldin, M.; Lusis, A. Multi-Omics Approaches to Disease. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Habsi, N.; Al-Khalili, M.; Haque, S.A.; Elias, M.; Olqi, N.A.; Al Uraimi, T. Health Benefits of Prebiotics, Probiotics, Synbiotics, and Postbiotics. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on the Definition and Scope of Postbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Lu, Y.; Ding, W.; Xu, B.; Zhang, C.; Li, L.; Jian, F.; Huang, S. The Role of Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics, and Postbiotics in Livestock and Poultry Gut Health: A Review. Metabolites 2025, 15, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żółkiewicz, J.; Marzec, A.; Ruszczyński, M.; Feleszko, W. Postbiotics—A Step Beyond Pre- and Probiotics. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, B.; Toschi, A.; Piva, A.; Grilli, E. Single Components of Botanicals and Nature-Identical Compounds as a Non-Antibiotic Strategy to Ameliorate Health Status and Improve Performance in Poultry and Pigs. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2020, 33, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, G.R.; Ledoux, D.R.; Naehrer, K.; Berthiller, F.; Applegate, T.J.; Grenier, B.; Phillips, T.D.; Schatzmayr, G. Prevalence and Effects of Mycotoxins on Poultry Health and Performance, and Recent Development in Mycotoxin Counteracting Strategies1. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 1298–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Formation of Propionate and Butyrate by the Human Colonic Microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, S.R. Diet, Microbiome, and Colorectal Cancer. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2017, 31, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, S.R.; Kuipers, E.J.; Peppelenbosch, M.P. Functional Genomic Analyses of the Gut Microbiota for CRC Screening. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 10, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Gong, L.; Huang, K.; Li, F.; Tong, D.; Zhang, H. Effect of Heat-Inactivated Compound Probiotics on Growth Performance, Plasma Biochemical Indices, and Cecal Microbiome in Yellow-Feathered Broilers. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 585623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham Thi, H.H.; Phan Thi, T.V.; Pham Huynh, N.; Doan, V.; Onoda, S.; Nguyen, T.L. Therapeutic Effect of Heat-Killed Lactobacillus Plantarum L-137 on the Gut Health and Growth of Broilers. Acta Trop. 2022, 232, 106537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incharoen, T.; Charoensook, R.; Onoda, S.; Tatrakoon, W.; Numthuam, S.; Pechkong, T. The Effects of Heat-Killed Lactobacillus Plantarum L-137 Supplementation on Growth Performance, Intestinal Morphology, and Immune-Related Gene Expression in Broiler Chickens. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2019, 257, 114272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, S.; Di, H.; Deng, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, H. Gut Health Benefit and Application of Postbiotics in Animal Production. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Huangfu, L.; Liu, C.; Bonfili, L.; Xiang, Q.; Wu, H.; Bai, Y. Electrospinning and Electrospraying: Emerging Techniques for Probiotic Stabilization and Application. Polymers 2023, 15, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Huang, R.; Wu, R.; Wei, Y.; Zong, M.; Linhardt, R.J.; Wu, H. A Novel Route for Double-Layered Encapsulation of Probiotics with Improved Viability under Adverse Conditions. Food Chem. 2020, 310, 125977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Sabharwal, V.; Kaushik, P.; Joshi, A.; Aayushi, A.; Suri, M. Postbiotics: From Emerging Concept to Application. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 887642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, R.C.; Sarkar, S.L.; Roy, P.C.; Anwar, A.; Hossain, M.A.; Jahid, I.K. Prebiotics, Probiotics and Postbiotics for Sustainable Poultry Production. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2021, 77, 825–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J.; Mwangi, F.; Pewan, S.B.; Holman, B.W.; Malau-Aduli, A. Emerging Applications of Postbiotics to Sustainable Livestock Production Systems. Aust. J. Agric. Veter-Anim. Sci. (AJAVAS) 2025, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Zoetendal, E.G.; Venema, K.; de Vos, W.M.; Smidt, H. Review: Tools for the Tract: Understanding the Functionality of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2009, 2, S9–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoetendal, E.G.; Rajilić-Stojanović, M.; de Vos, W.M. High-Throughput Diversity and Functionality Analysis of the Gastrointestinal Tract Microbiota. Gut 2008, 57, 1605–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Afzal, Z.; Afzal, F.; Khan, R.U.; Elnesr, S.S.; Alagawany, M.; Chen, H. Use of Postbiotic as Growth Promoter in Poultry Industry: A Review of Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2023, 43, 1111–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humam, A.M.; Loh, T.C.; Foo, H.L.; Samsudin, A.A.; Mustapha, N.M.; Zulkifli, I.; Izuddin, W.I. Effects of Feeding Different Postbiotics Produced by Lactobacillus Plantarum on Growth Performance, Carcass Yield, Intestinal Morphology, Gut Microbiota Composition, Immune Status, and Growth Gene Expression in Broilers under Heat Stress. Animals 2019, 9, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Regassa, A.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, W.K. The Effect of Dietary Fructooligosaccharide Supplementation on Growth Performance, Intestinal Morphology, and Immune Responses in Broiler Chickens Challenged with Salmonella Enteritidis Lipopolysaccharides. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 2887–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, P.; Zong, M.-H.; Linhardt, R.J.; Feng, K.; Wu, H. Electrospinning: A Novel Nano-Encapsulation Approach for Bioactive Compounds. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 70, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Stahl, B.; Vinderola, G.; Szajewska, H. Infant Formula Supplemented with Biotics: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salminen, S.; Gibson, G.R.; McCartney, A.L.; Isolauri, E. Influence of Mode of Delivery on Gut Microbiota Composition in Seven Year Old Children. Gut 2004, 53, 1388.2–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]