Abstract

The production and assembly of large engineering structures, many requiring tight tolerances, demand accurate long-distance measurements. This poses a major challenge for metrologists across industries such as energy, aviation, automotive, and machinery. Contact measurements provide high accuracy but are slow, as tactile probes must be moved over large distances. Optical methods are much faster, yet their effective range is usually limited to a few meters, and they generally offer lower accuracy. Measurements of large-scale components are further complicated by varying environmental conditions (e.g., temperature gradients) and the accumulation of different error sources, making high-accuracy measurements difficult to achieve. These challenges motivated the authors to develop hybrid measurement systems (HMS) and methods for improving their accuracy. This paper describes the steps taken to build an HMS combining a large-volume, high-accuracy coordinate measuring machine with a structured-light scanner. It also presents a dedicated method for determining measurement uncertainty in HMS, based on a multiple-measurement strategy. A series of tests were performed on material standards with various shapes, dimensions, and geometric features, using both contact and optical systems. The measurement uncertainties were then evaluated using the developed method. Finally, the method was validated through tests conducted on a selected large-scale engineering object.

1. Introduction

The beginning of the 21st century brought many changes in the way people look at the reality around them. The challenges of climate change and ongoing globalization affect the lives of every person, touching even the most mundane matters. The rapidly changing world also poses new challenges for the metrology of geometric quantities. One of the most important is the development of accurate methods for measuring large-sized objects (those whose dimensions exceed one meter but are often given in tens of meters) that are also able to meet the requirements of modern industrial solutions [1]. Due to their specificity, measurements of this type are more exposed to the influence of environmental conditions. It is also more difficult to ensure their automation, and in the case of elements whose dimensions are given in tens of meters, manual methods are most often still in use [2]. The demand for measuring large-sized elements is constantly growing and is a trend that will likely increase in the future. This is not surprising, considering in which areas of human activity this need can be observed. Above all, attention should be paid to the transport and energy industries [3].

Both optical and contact systems are nowadays used to measure large-sized objects [4]. Optical and contact systems differ in many respects. (Coordinate measuring machines operating in contact mode were selected as a representative of contact measurements in the comparison below because they have the highest accuracy of all contact coordinate measuring systems and are very often used.) Differences can be noticed in the following, among others:

- -

- Measurement time: the main advantage of optical systems over coordinate measuring machines (CMMs) is the acquisition of larger amounts of data in a shorter time period (even a few seconds) [5].

- -

- Measurement accuracy: the main advantage of using contact measurements is the ability to measure single points with uncertainties below 1 μm. For most optical systems, it is true that they are at least an order of magnitude less accurate.

- -

- Sensitivity to the surface parameters of the object: the main limitation for optical measurements is sensitivity to the surface parameters of the measured object, i.e., color, gloss, layer finish. The greatest difficulties occur when measuring glass, marble, steel, plastic, dark, polished, and rough materials with variable reflectivity and non-uniform texture [6].

- -

- Non-invasiveness: lack of pressure related to contact force allows optical systems to measure elements made of soft, delicate materials, thin-walled profiles, and parts made of plastics, as well as anthropometric and medical measurements. However, in the case of CMMs, there is a possibility of destruction or warping of the material.

- -

- Mobility: unlike coordinate measuring machines, it is possible to move the optical system, which is important if it is not possible to transport the measured object.

- -

- Regarding the geometry of an object, its geometric features have a significant impact on the measurement results of the object. Non-contact systems have problems with measuring edges, discontinuous features, and holes. As the depth increases, and therefore the angle between the vector normal to the surface and the projection direction increases, the scattering ability decreases. On the other hand, the tip of the CMM measuring stylus is not able to penetrate all valleys or measure contours with small rounding radii.

- -

- Coordinate system: optical systems have problems with measuring edges, which makes it difficult to correctly determine the origin of the coordinate system. Moreover, in order to obtain a complete reconstruction of the object, these systems must make many images from different sides. Most of them work in several local coordinate systems, which are reduced to one global coordinate system only during the process of combining directional data. Coordinate measuring machines build one local coordinate system on an object, based on the elements of the object’s geometry [7].

- -

- Cost of the measurement system: optical systems, due to the increasingly lower prices of optoelectronic elements, i.e., CCD cameras and digital projectors, constitute a competitive offer for other measuring devices.

Due to these differences, in order to use the advantages of both methods, a hybrid measurement system (HMS) can be developed consisting of different types of measuring systems. There are several HMSs described in the subject’s literature. In [8], a system composed of a CMM and a structured-light scanner mounted at a fixed position relative to the CMM measurement volume is described. Both systems operate within a unified coordinate system established by independently measuring a ball-plate artefact with each device and subsequently determining the corresponding transformation matrices. A key stage of the measurement process is the segmentation of the point cloud obtained from scanning into regions representing individual surfaces. The accuracy of the described hybrid system for length measurement approaches 50 µm, indicating that the performance is predominantly limited by the 3D scanner, as the CMM used in the configuration is a high-precision machine with an accuracy nearly fifty times higher. Another example of a hybrid system combining a CMM and a 3D scanner is presented in [9]. In this case, the scanner is mounted on the CMM quill and can therefore change its position within the CMM measuring space. Additionally, the hybrid system incorporates a rotary table to increase scanning efficiency. The CMM is used for measuring features that are inaccessible to the scanning technique and for measuring elements serving as positioning references. Coordinate-system unification is performed by measuring a reference sphere, and the authors report that the spatial measurement accuracy is approximately 30 µm. However, the accuracy tests provided are less closely aligned with procedures known from normative documents. A further hybrid configuration is described in [10], where the system consists of a CMM and a structured-light scanner, but the novelty lies in the inclusion of a measuring arm equipped with a probing head capable of both contact measurement and laser-triangulation scanning. Coordinate-system unification for all components of the hybrid system is achieved by measuring a dedicated sphere-plate artefact, followed by a specially developed alignment method based on the centroids of the sphere centers. This approach provides higher unification accuracy than strategies relying solely on nominal sphere-center coordinates.

As shown above, a major issue addressed in most hybrid coordinate-measurement systems is the unification of coordinate systems belonging to the individual components of the hybrid configuration. This challenge forms part of the broader problem of data fusion [11] for measurements obtained using heterogeneous point-acquisition systems and devices with different accuracy levels. A related difficulty concerns ensuring metrological traceability for such systems, where current solutions typically rely on combining calibration procedures established for the individual subsystems forming the hybrid arrangement [12]. The problem of data fusion for multisensory systems is discussed in a general context in [13], where several areas requiring further research are identified, including handling regions with conflicting information, data-compression strategies, and methods for dealing with outliers. In the field of geometric measurement, numerous studies [14,15,16] present new data-fusion methods for combining datasets that are highly accurate but sparse—typically those obtained from CMMs—with datasets that are less accurate but dense, as commonly produced by 3D scanners.

A separate research area concerns hybrid systems designed for large-scale measurements. The previously cited studies describing combinations of CMMs and structured-light scanners typically concern machines operating within standard measurement volumes and therefore do not address challenges characteristic of large-scale metrology. An example of a hybrid system for large-scale applications is described in [17], where a laser total station is used to ensure the appropriate positioning of an AACMM. The coordinate systems of both devices are linked through a method based on measuring a hidden-point-bar tool, and the accuracy of coordinate-system unification within the hybrid measuring space—which extends several meters along its longest axis—was approximately 0.2 mm. Other examples of hybrid metrology systems include configurations combining theodolites with a 3D scanner [18], as well as systems in which a 3D scanner is mounted on a robot and the entire assembly is transported on a trolley positioned using tracking coded marks [19].

In this article, a hybrid system for large-scale measurements composed of a coordinate measuring machine and a structured light scanner was developed. Such a system was presented in the first part of the article. Since, as is commonly known, providing the value of a measurement result without determining its uncertainty is useless from a practical point of view, an integral part of the work on the development of a hybrid measurement system was the development of a method for assessing the uncertainty of measurements carried out using this system. The second part of the article presents this method.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Developed Hybrid Measuring System

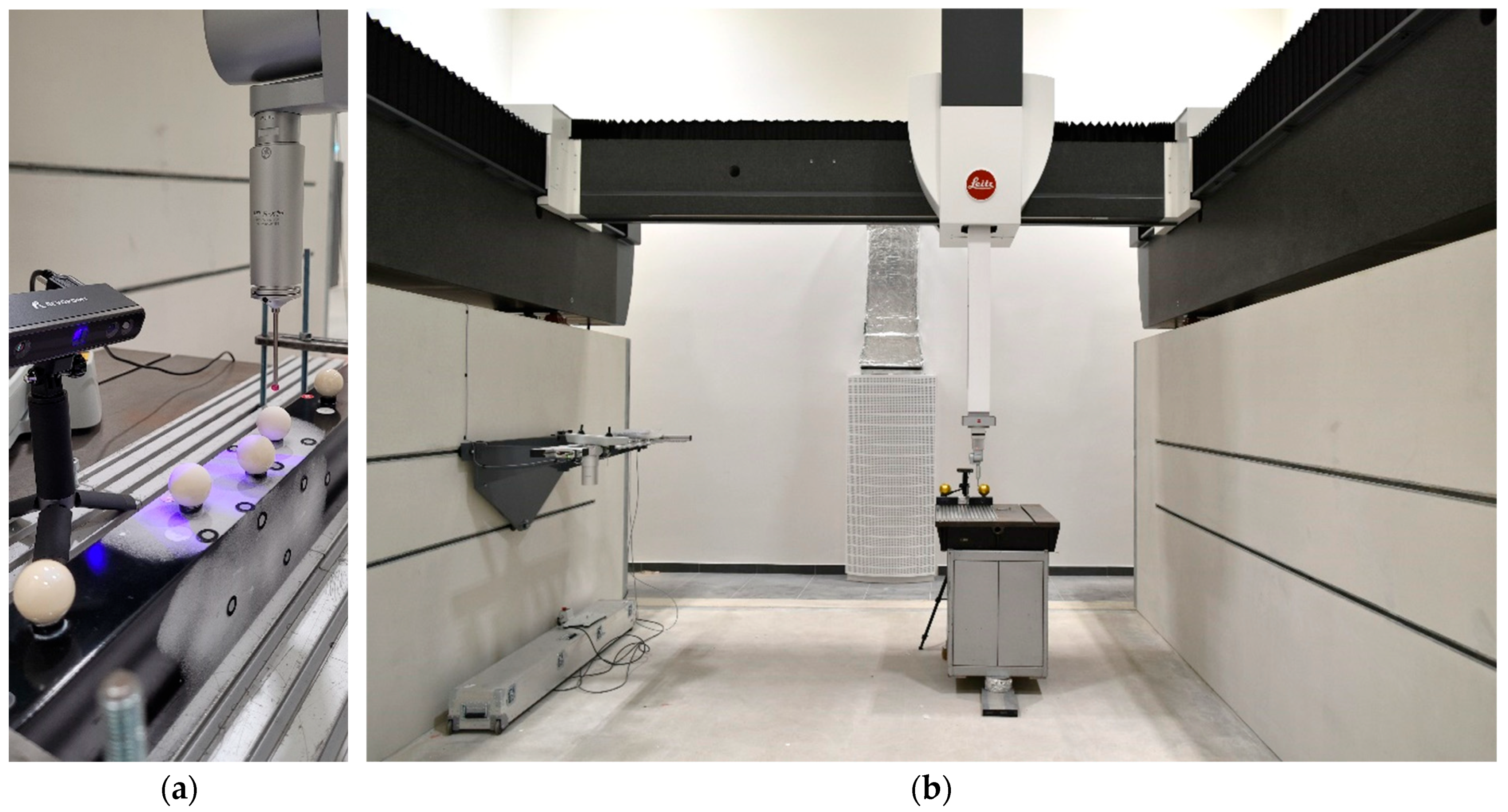

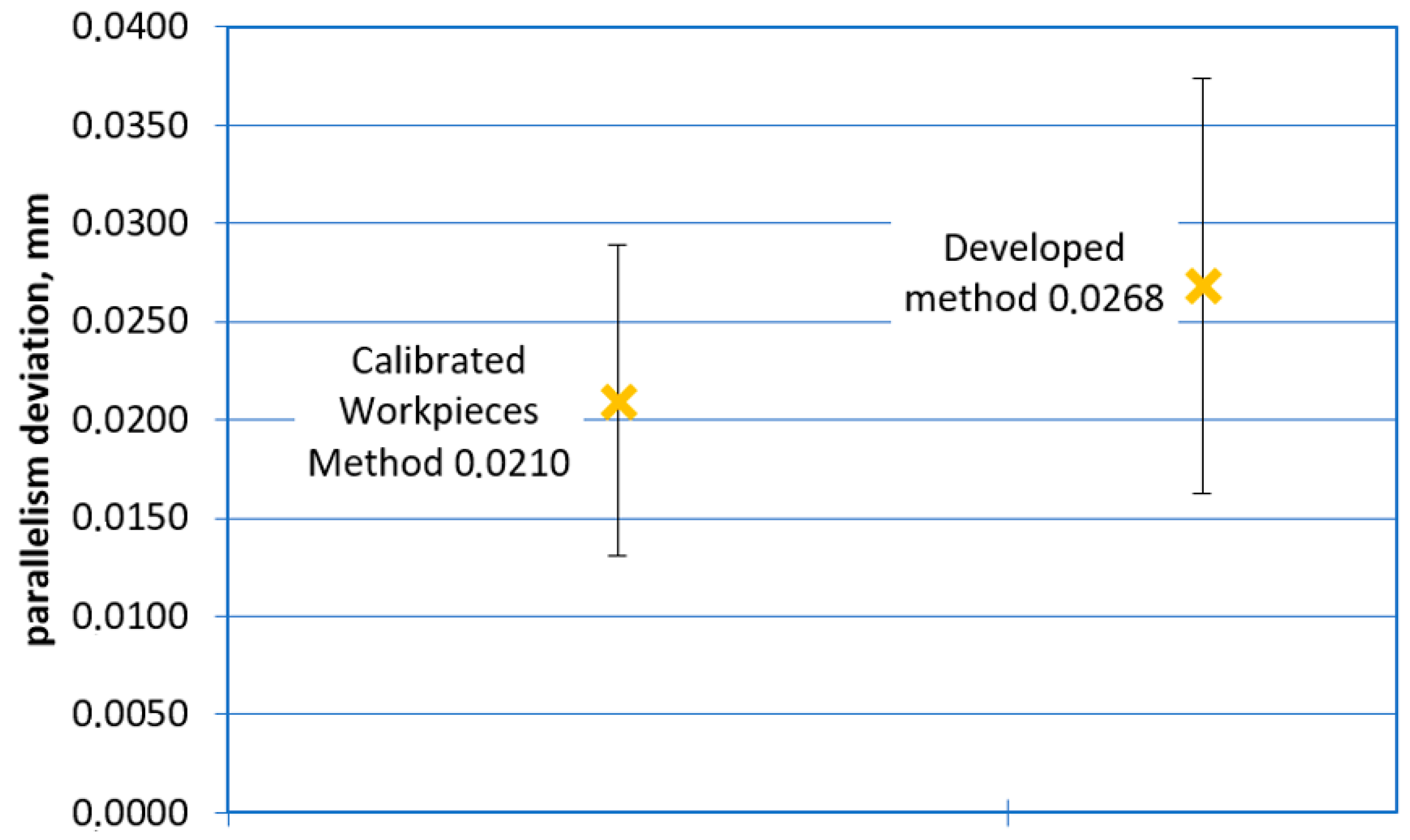

The HMS described in the article is intended for measuring the geometric features of 3D static objects by describing the surfaces of the measured parts with sets of point coordinates measured by the systems included in the HMS. This hybrid system is based on the use of an accurate large-volume coordinate measuring machine PMM-G 50.30.20 (Hexagon, Wetzlar, Germany) (with measuring volume of 5 × 3 × 2 m, E0,MPE equal to 3.0 + L/400 µm (where L is given in mm), and PForm.Sph.1x25:SS:Tact.MPE at the level of 2.2 µm made by a hexagon) and a structured light scanner produced by REVOPOINT (Hongkong, China) (3D Scanner MINI model, with measuring volume of 168 × 132 mm and MPESD = 0.02 mm) and combines the advantages of both systems (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hybrid measuring system based on the use of an accurate large-volume coordinate measuring machine PMM-G 50.30.20 and a structured light scanner 3D Scanner MINI: (a) 3D scanner and probing system of CMM; (b) general view on the hybrid system.

The principle of operation of this system can be described as follows. The first stage of measurements involves adopting one coordinate system for both measurement systems. To obtain better accuracy of the hybrid system, the less accurate measurement system (structured light scanner) reproduces the coordinate system of the more accurate system, the coordinate measuring machine. The acquisition of the system is performed by measuring any object consisting of three spheres using both systems and determining the transformation between the systems. The transformation is carried out in accordance with Equation (1), and to perform it, it is necessary to determine the translation vector and rotation matrix of the coordinate systems, which are determined using an algorithm implementing the best fit method based on the least squares method.

where x, y, z are the coordinates of the points after the transformation in the new coordinate system, x′, y′, z′ are the coordinates of the measured points, Tr is the translation vector of the coordinate system, and Rx, Ry, Rz are the rotation matrices around, respectively, the x, y, and z axes of the coordinate system.

In the next stage of measurement, the local coordinate system is defined on the measured object. If possible (it could not be possible when easily deformable parts are measured and may only be measured using optical systems), the geometric elements on the workpiece used for this definition are also reproduced using the point method (in the case of this paper, the system implementing point method is the PMM-G machine) to ensure higher measurement accuracy. Then the tested object is measured in this system by a structured light scanner. In the next stage, the point cloud obtained as a result of the measurements is analyzed. The result of this analysis is the division of the cloud into areas representing geometric features (planes, cylinders, cones, spheres) and free surfaces. In the last step, the divided cloud is sent to the metrology software, which enables the determination of deviations from the nominal dimensions or the CAD model of the measured object.

2.2. Method for Uncertainty Determination of Measurements Performed Using HMS

Initially, when developing a method for assessing the uncertainty of measurements carried out using hybrid systems, the authors assumed the use of the uncertainty budget method, which consists of individually estimating the impact of all identified components influencing the measurement uncertainty and then determining the total measurement uncertainty based on them. However, the authors abandoned this approach because hybrid systems involve interpenetration of influences, which are difficult to clearly and reliably separate into independent components across the entire range of applications. Obtaining a reliable result with this approach would require determining the relationships between the components and their variability as a function of the geometry of the measured feature, measurement directions, object setup configuration, and environmental conditions. In practice, this would require conducting a very large number of additional tests across multiple variants to reliably characterize the interdependencies between the influences and avoid arbitrary assumptions. Such a research program would be time-consuming and difficult to generalize to typical laboratory quality control tasks for large components. Furthermore, it should be emphasized that the classic uncertainty budget is conservative. In conditions of complex interdependencies between influences, this can lead to an overestimation of uncertainty compared to approaches based on empirical verification, limiting the practical usefulness of the result.

For these reasons, the authors adopted a multiple measurements strategy as a more practical solution for the hybrid system. This approach allows for the empirical assessment of the combined impact of various influences on the measurement result, including influences that are difficult to model unambiguously and interrelated influences, without the need to determine correlation coefficients in a budget model. This strategy involves multiple measurements of an uncalibrated object and, in some situations, a length standard, using different positions in the measuring system’s volume and different locations of measurement points. The above procedure is based on the assumption that for each geometric feature (e.g., distance, angle), measurements will be made in the appropriate number of directions. Only then may it be possible to obtain enough data to determine the collective impact of all components of measurement uncertainty (listed above) on measurement uncertainty. In the proposed uncertainty assessment method, it is recommended to set the measured object (and, if necessary, a length standard, the measurement of which is recommended in the case of measuring tasks involving the determination of distances, diameters, positions, etc., and is performed to correct systematic errors related to distance measurement) in the following three positions: one basic and two additional resulting from the rotation of the object around the individual axes of CMM, starting from the basic position. Due to the fact that in the case of the hybrid measurement systems under consideration, the measured objects are often very large and heavy, it is possible to limit the number of positions in which measurements of the measured object and the standard should be made to two. The recommended number of repetitions in each position is a minimum of 3 if 4 positions are used or a minimum of 6 if 2 positions are used.

The general formula for determining the expanded uncertainty of measurement in accordance with the proposed method has the following form (2):

Component urep describes repeatability of HMS during assessed feature measurements and is calculated from results obtained from all utilized positions using the following Formula (3):

where is the number of repetitions in each utilized position; is the number of positions used in the uncertainty estimation procedure; and is the standard deviation of mean calculated for each position.

Next, component ugeo describes the influences of the geometrical errors of the measurement system on measurement uncertainty and can be formulated as follows (4):

where is the number of positions used in the uncertainty estimation procedure; is the mean value of the results obtained in the i-th position; and is the mean value from all measurements included in uncertainty estimation procedure calculated as follows (5):

where is the number of repetitions in each utilized position; is the number of positions used in the uncertainty estimation procedure; and is the result obtained for the i-th repetition in the j-th position.

The subsequent element of expended uncertainty formula is ucorrL, which is used to assess influences related to the correction of the systematic error of length measurement. It can be determined based on results obtained from length standard measurements, which should be performed in orientations compliant with the main axes of CMM included in HMS. It should be noted that the utilized standard does not need to fulfill very strict similarity requirements formulated in [20]. Equation (6) for calculating ucorrL can be given as follows:

where L is the nominal value of the length under measurement; is the nominal length represented by the standard utilized for length correction; is the expanded uncertainty of the nominal length calibration of the standard utilized for length correction taken from the calibration certificate; is the expansion factor read from the calibration certificate of length standard; and is the standard uncertainty calculated from all measurements of the standard of length.

The uncertainty component ud related to the correction of the systematic error of diameter measurement can be obtained by measuring the ring gauge or spherical standard in at least two positions. The following Formula (7) should be used to determine this component:

where is the expanded uncertainty taken from the calibration certificate of the utilized standard; is the expansion factor read from the calibration certificate; and is the standard uncertainty calculated from all standard measurements.

The last component utemp is related to thermal influences affecting the measurement process. The temperature of the workpiece should be monitored throughout the whole procedure that leads to uncertainty estimation, as well as the temperature in measuring the volume of HMS and, if applicable, the temperature of the utilized standards. The component can be assessed utilizing the following Formula (8):

where is the component related to thermal influences during workpiece measurements, and is the component related to thermal influences during standard element measurements. Both can be calculated using Formula (9):

where x is the indicator, which can take one of two forms, W for workpiece and S for standard element; L is the length to be measured; is the average temperature of the measurement system during the measurements; is the average temperature of the workpiece/standard element during the measurements; αM is the thermal expansion coefficient of the measurement system; αx is the thermal expansion coefficient of the workpiece/standard element; u(αM), u(αx) is the standard uncertainty of the thermal expansion coefficient of the measuring system and workpiece/standard element; and u(tM), u(tx) is the standard uncertainty of the temperature sensor used to measure the temperature of the measuring systems and the standard uncertainty of the temperature sensor used to measure the temperature of the workpiece/standard element.

When developing a method for assessing the uncertainty of measurements carried out using hybrid systems, the use of other methods was considered. They included a method based on measurements of calibrated objects (material standards) and a method involving multiple simulations of a single measurement based on previously determined models of variability of errors occurring during the measurement process. The calibrated workpieces method was rejected because for the measurement of large-sized objects, it would be necessary to build a very extensive and expensive (in preparation and later in operation, due to the need for periodic calibration of all standards included in the database) database of standards that meet the similarity conditions specified in the ISO 15530-3:2011 standard [20]. The simulation method based on [21] has been recognized as giving good prospects for the measurement of large-size elements; however, it requires the development of error models for all measurement systems that may be used in HMS. While such models already exist for systems implementing point-measurement methods for most types of devices, very few models have so far been developed for systems based on field-measurement methods.

3. Results

In this section, the results of two phases of implementation of the measurement uncertainty determination method for hybrid measuring systems are presented.

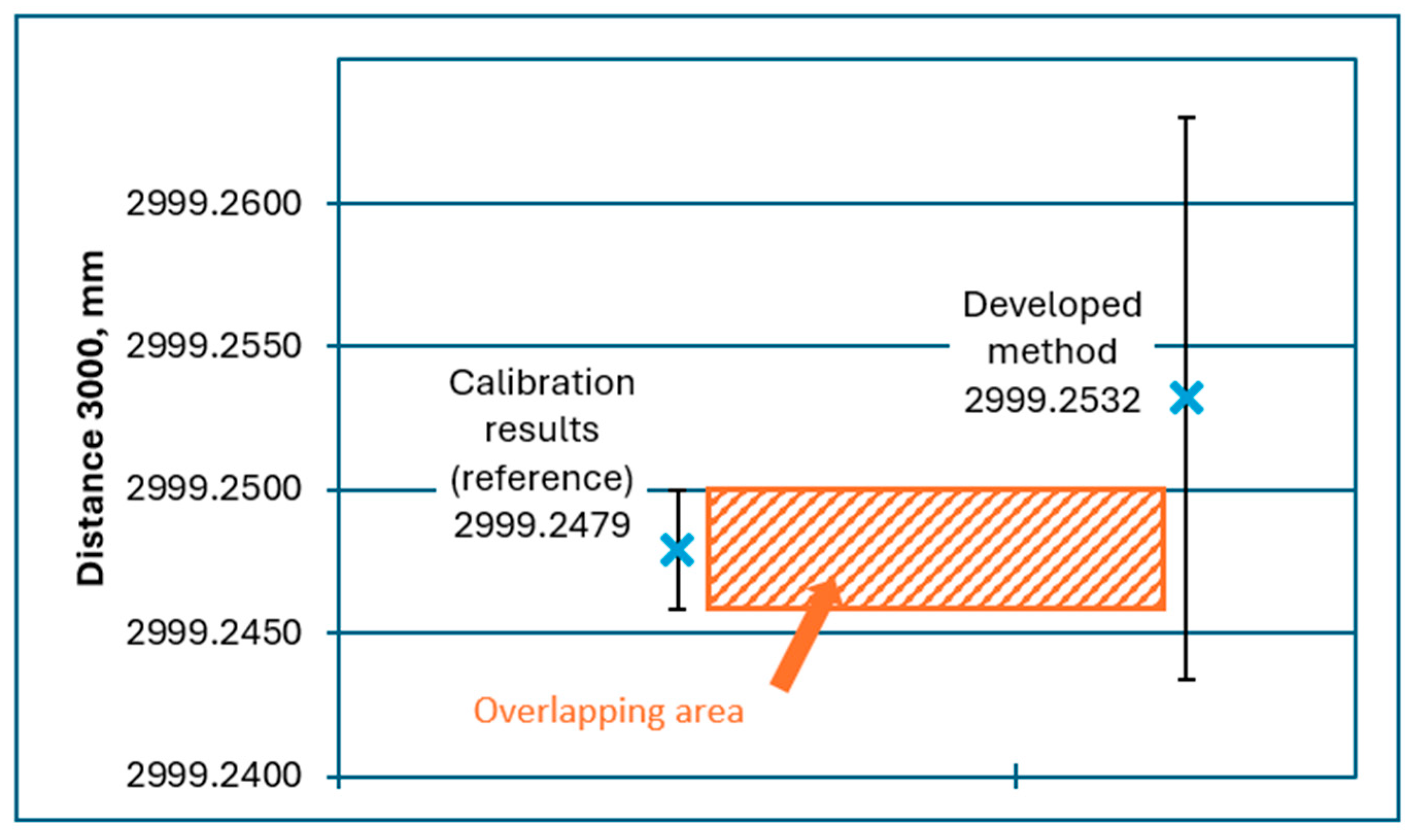

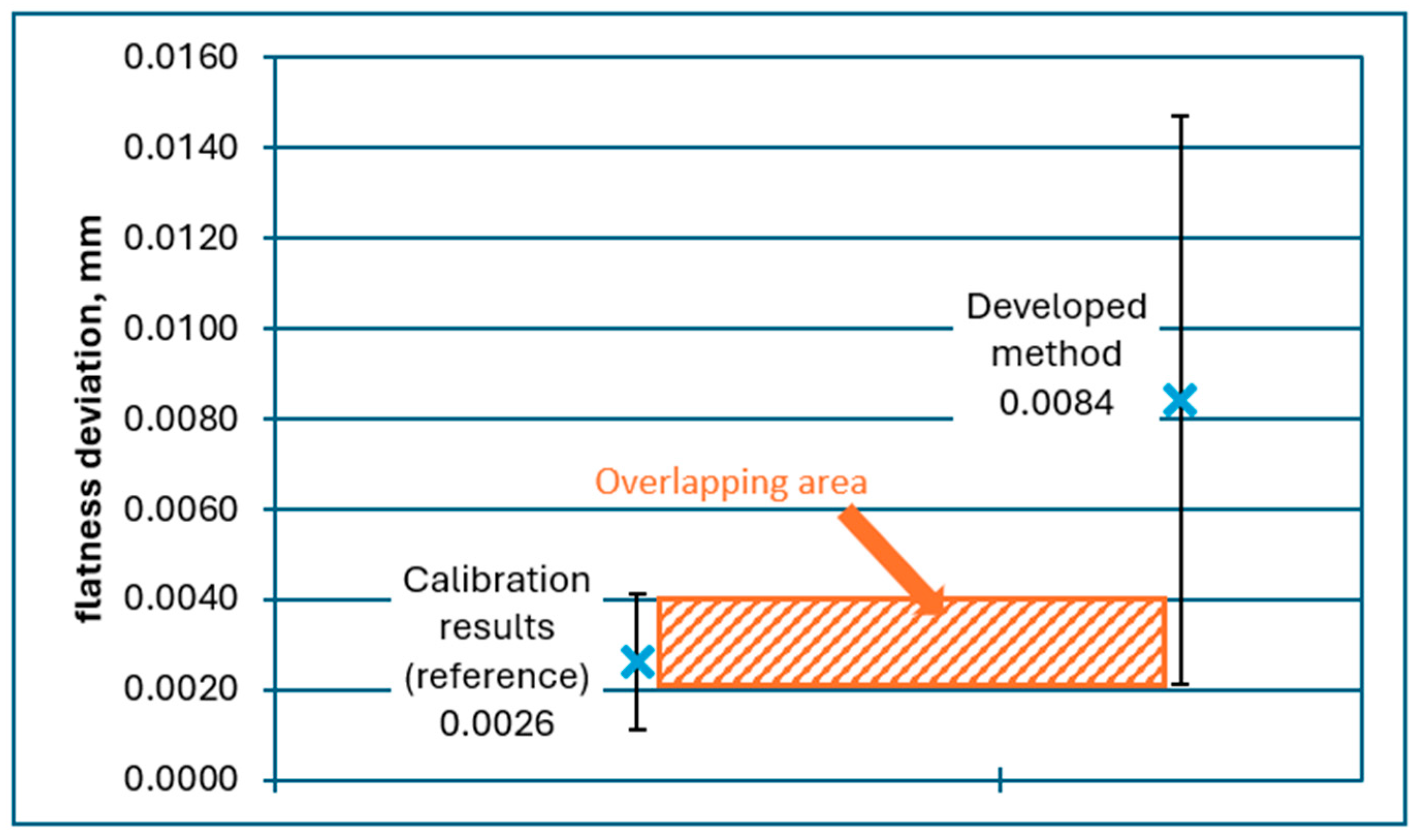

The first one consists of a measurement series aiming to measure different material standards. Results of measurements with corresponding measurement uncertainty values were compared to results of the calibration of standards that were used. This comparison aimed in presenting that the developed hybrid measuring system is capable of finding the correct measurement result with specified probability (95% in this case). If the intervals presenting the determined result of the measurement plus/minus the value of expanded uncertainty overlap with the intervals presenting the results of standard calibration, it is the most probable that the real measurement value determined using HMS is inside the interval that is a common part of the two intervals mentioned before. In this phase, a three-meter-long ball-bar standard, the spherical standard for optical measurements (consisting of a sphere made from steel covered with a titanium nitride layer), and a flatness standard (in the shape of a rectangular block with a reference flat surface of a size of about 200 × 300 mm) were measured. All standards were calibrated in accredited calibration laboratories, and calibration certificates issued no longer than two years ago are available. Standards were measured in two positions with a change in alignment angle (measured along the vertical axis) equal to 90 degrees. In each position, measurements were repeated six times.

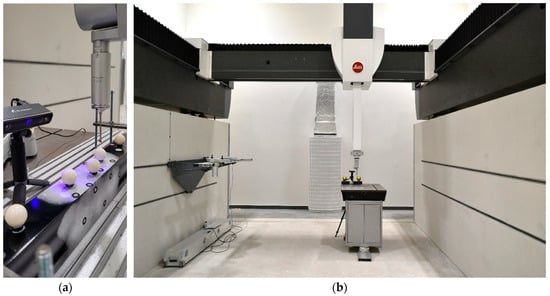

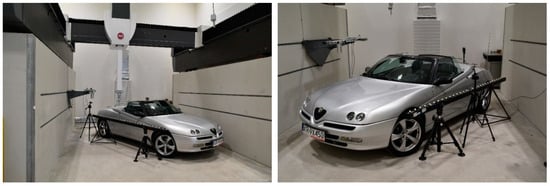

The second phase included measurements of the chosen large-volume workpiece. As a measured workpiece, a car body was chosen. The measurement involved determining the distance between two planes corresponding to the license plate mounting locations, which constituted a measurement of the object’s length along its axis. Additionally, the spacing of the roof guide pin holes was measured (distance between axes of cylinders). These holes were located in the rear part of the car body just behind the passenger cabin and were cylindrical. For one of the roof guide pin holes, the inner diameter was determined. Additionally, the parallel deviation between the axes of the two measured pin holes was determined. The measurement of the roof guide pin holes is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Measurements of roof guide pin holes in the car body using developed hybrid measuring system.

Result analysis was conducted in GOM Inspect 2019 software. Data from the coordinate measuring machine and the optical system software were exported to the common GOM Inspect analysis environment, where they were fused using the fusion method described in [12]. Next, geometry matching and feature calculations were performed.

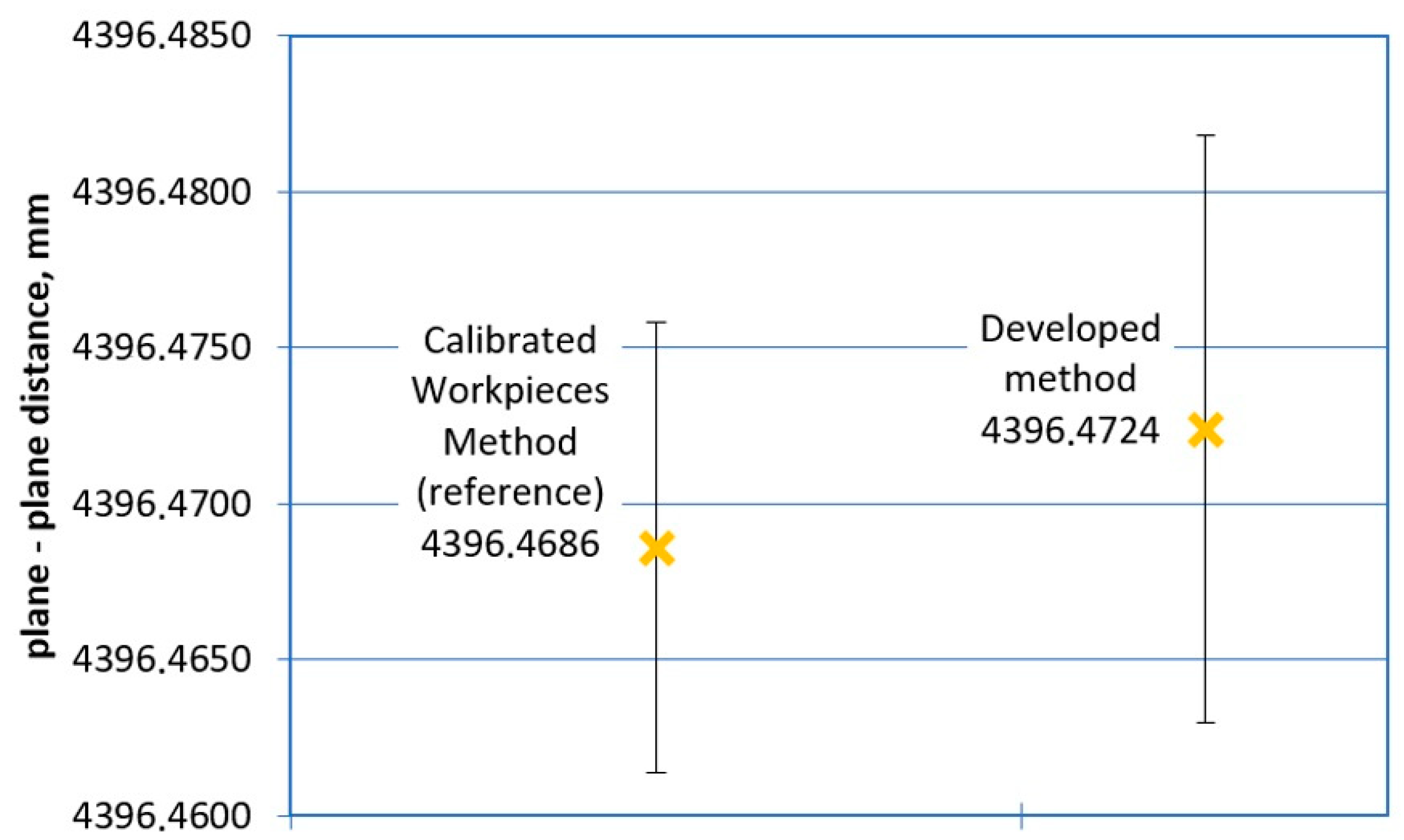

Measurements were performed according to the guidelines of the method presented in this paper and the method based on the use of calibrated workpieces known from [20]. In the case of the measurements done according to the developed method, the measured workpieces were located in two positions, described in Section 3.2. It should be noted that in this case, the relation between the two positions was not exactly 90°; it was as close to this value as possible taking into consideration the limited measuring volume of the utilized large-scale CMM. The chosen geometrical features were measured six times in each position. In the case of measurements performed in accordance to the guidelines of [20], as a calibrated workpiece, the three-meter-long ball-bar standard and ball plate were used. Measurements of the same geometrical features/relations as in the case of the measurements according to the developed method were repeated 20 times both for car measurements and material standards measurements.

3.1. Measurements of Material Standards

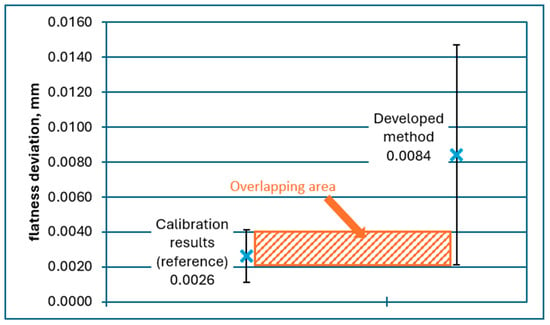

Figure 3 presents the measurements of material standards using HMS. The results of the measurements are presented in Table 1 and Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 3.

Measurements of spherical standard for optical measurements using developed hybrid measuring system.

Table 1.

Results of measurements of different standards using developed hybrid measuring system compared to results of standards calibration: x—measurement/calibration result, U(x)—expanded uncertainty of measurement/calibration.

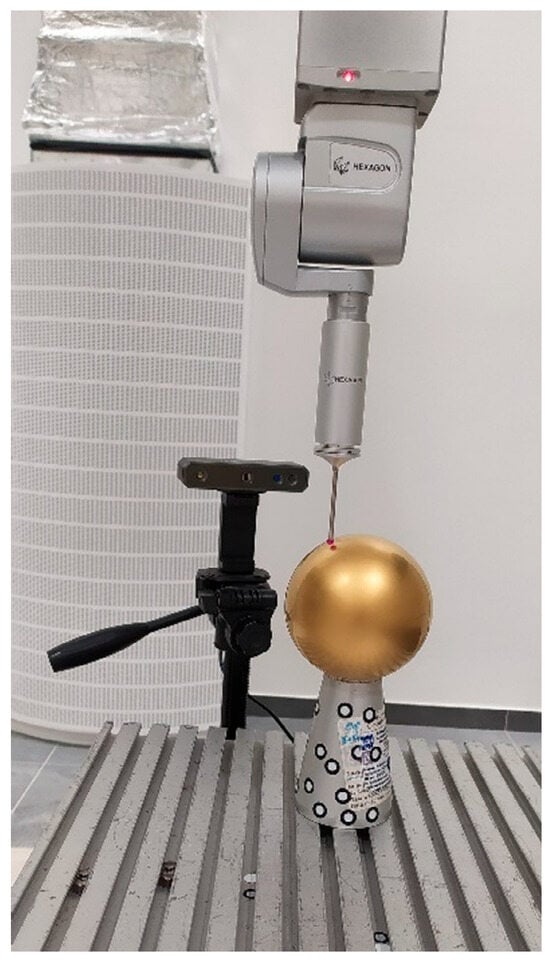

Figure 4.

Graphical comparison of standards measurements results with results presented in calibration certificates of standards for distance 3000 of 3 m ball-bar standard.

Figure 5.

Graphical comparison of standards measurements results with results presented in calibration certificates of standards for distance flatness deviation of flatness standard.

Overlapping of the intervals described at the beginning of Section 3 may be observed for all presented results.

3.2. Measurements of Chosen Large-Volume Workpiece

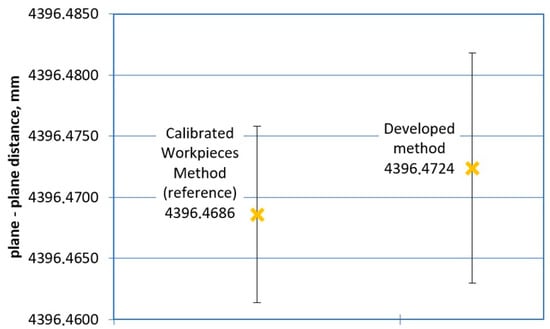

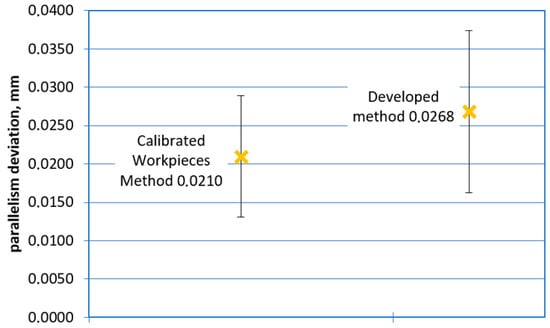

Figure 6 presents measurements of large-scale element and material standards (3 m long) using HMS. The results of the measurement are presented in Table 2 and Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 6.

Measurements of car body using developed hybrid measuring system.

Table 2.

Results of measurements of car body performed on developed hybrid measuring system using developed methodology and methodology based on calibrated-workpieces approach: x—measurement result, U(x)—expanded uncertainty of measurement.

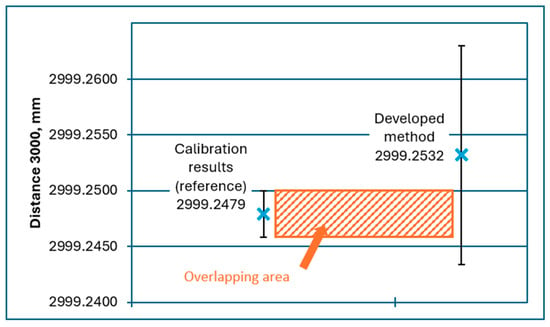

Figure 7.

Graphical comparison of car body measurements results obtained using developed methodology and methodology based on calibrated-workpieces approach for measurement of plane–plane distance.

Figure 8.

Graphical comparison of car body measurements results obtained using developed methodology and methodology based on calibrated-workpieces approach for measurement of parallelism deviation.

After the measurements were performed, the statistical consistency test presented in [22,23] and in relation to coordinate measurements in [24] was performed in order to statistically compare the results obtained using both methods. For all performed measurements of the car body, the statistical consistency test gave positive results; therefore, the developed method for assessing the uncertainty of measurements carried out using HMS was considered to be giving metrologically correct results in relation to the measurement tasks for which the verification was performed.

4. Discussion

The results obtained in both phases of the study demonstrate that the developed HMS, together with the proposed uncertainty determination method, provides reliable measurement performance for dimensional metrology tasks involving large-volume workpieces. The measurements of calibrated material standards showed that all evaluated features—including lengths, diameters, form deviations, and flatness—exhibited overlapping intervals between the measurement results obtained using the HMS and the corresponding calibration certificates. This confirms that the HMS, despite combining measurement data from devices with significantly different accuracy levels, is capable of producing results that align with traceable reference values. Such behavior is consistent with observations reported in earlier studies on hybrid tactile–optical systems [8,9,10], where the overall accuracy was strongly influenced by the optical subsystem yet remained predictable and stable when coordinate-system unification was properly established.

The analysis of measurement uncertainty determined using the newly developed method indicates that the multiple-measurement strategy provides a robust alternative to classical uncertainty budgeting or the calibrated-workpiece approach defined in ISO 15530-3 [20]. Furthermore, when applied to the large-scale workpiece (car body), the method demonstrated metrological consistency with the calibrated-workpiece method, which remains one of the most established approaches for task-specific uncertainty evaluation. All analyzed geometrical features showed statistically consistent results across both methods, as confirmed by statistical consistency testing [22,23,24]. Importantly, the HMS achieved this performance despite requiring significantly fewer repetitions and without the need for costly and extensive sets of length standards typically associated with ISO 15530-3 procedures. This indicates that the proposed approach offers a more practical and scalable solution for industrial environments, especially in applications involving large, heavy, or difficult-to-reposition workpieces. The measurement accuracy achieved for the car body confirms that hybridization can overcome limitations inherent to individual systems, such as the restricted accuracy of optical sensors or the slow measurement speed of tactile devices. The successful use of the HMS in an industrial-scale measurement scenario further supports observations from previous studies demonstrating the potential of hybrid configurations for large structures [17,18,19].

For industrial applications, the proposed hybrid measurement system and uncertainty determination method can be considered in the context of quality control of large components, where both accuracy requirements and time-efficient inspection are essential. In such a scenario, contact measurement can serve as a reference for functional features requiring high metrological reliability, while optical measurement can support the rapid acquisition of global geometry information and the identification of critical areas. The practical application of this approach requires consistent alignment of the coordinate systems of both subsystems, so that data can be analyzed within a single reference frame. Potential applications include the automotive industry, where large body components and structures such as frames or tubular bodies, structures, and instrumentation are inspected; the aerospace industry, where panels and supporting structures with high tolerance requirements are verified; and heavy industry, where large machine parts and structural elements require geometric evaluation.

The use of an optical scanner can also be helpful in cases where more complete information about geometric features is required, especially for features with complex surface topology and areas difficult to access by contact measurement. This can be particularly important in situations where the measured part is flexible and contact measurement can lead to local deformation, thus introducing additional measurement error. This applies, among other things, to thin-walled elements and details made of flexible materials such as plastics or elastomers, where non-contact measurement with a scanner can limit the impact of the measuring head on the surface. In such cases, a hybrid system allows for the selection of a measurement strategy tailored to the nature of the feature and material properties, which can help improve the reliability of results in specific measurement tasks.

It should be emphasized that the presented method for determining uncertainty is currently primarily laboratory based. This is because its practical application requires access to an appropriate set of standards and reference results that allow the procedure to be carried out under conditions ensuring measurement traceability.

Although the presented method performed effectively across all evaluated cases, several aspects require further investigation. The current approach assumes that the dominant sources of measurement variability can be captured through repeated measurements in a limited number of object orientations. This assumption proved valid for the studied workpieces.

The main limitation of the proposed method is likely related to situations in which it is difficult to obtain at least two distinct orientations of the measured object. Although the presented example of a car body measurement using the HMS demonstrates that even for such a large object it was possible to achieve two significantly different orientations, in the case of certain workpieces—particularly elongated ones (e.g., with a length comparable to the travel range of the longest axis of a large-volume CMM)—the use of the calibrated-workpiece method with measurements performed in a single orientation may prove to be a more appropriate solution. However, this method requires the use of a reference artefact with characteristics very similar to those of the measured feature, which, if such an artefact is not already available to the HMS user, may involve additional costs for its acquisition or even prevent the application of the method altogether.

Another potential limitation is the complex geometry of the measured object. The proposed method assumes a different distribution of measurement points for each position and orientation of the object, which makes it possible to account for the influence of variations in the geometry of the measured part. In such cases, if feasible, the measurement should be performed with reference to the CAD model of the inspected object, as this would allow the minimization of errors related to probe-tip compensation.

Considering the above limitations, it may be expected that the most effective approach to uncertainty estimation for HMS could be the digital twin method, which offers the possibility of determining the measurement uncertainty for each point used in the evaluation of measured features. The development of such a solution undoubtedly constitutes an interesting direction for future research. However, given the fact that there are currently very few functional simulation-based uncertainty-estimation systems for large scale geometric measurements, it should be anticipated that the development of such a solution for HMS will be a demanding task. An open challenge concerns the modelling of field-measurement systems, particularly optical scanners, for future potential implementation of simulation-based uncertainty estimation. As noted in [21], such an approach offers promising capabilities but requires detailed error models that are currently unavailable or incomplete for many structured-light systems.

Future work could focus on the development of advanced models of optical measurement errors, particularly optical scanner error models, with the prospect of ultimately implementing simulation-based uncertainty estimation. This approach offers promising opportunities because it allows for the controlled and repeatable assessment of the impact of multiple influences on the result. At the same time, it requires the development of detailed error models, which are currently unavailable or incomplete for many structured light systems. Model development requires first identifying the main error sources and then constructing a mathematical description of the impact of each of these sources on the measurement result. In the case of optical scanners, key challenges include the variability of acquisition and 3D reconstruction parameters, the dependence of the result on the object’s surface properties, and the influence of observation geometry and lighting conditions, as well as environmental influences, including the effect of temperature on the stability of the measurement system. The limited availability of diagnostic data and internal device parameters also remains a significant problem, hindering the direct modeling of some phenomena and necessitating the use of experimental identification procedures based on standards and comparative measurements. From a methodological perspective, a possible approach might involve combining geometric and kinematic models of the optical system with models of the point reconstruction process and environmental influences, followed by identification of model parameters based on measured patterns in multiple configurations. This approach could provide a basis for building a digital equivalent of the optical system and for estimating uncertainty in simulation mode. The authors want to point out that work in this area is being conducted at the Cracow University of Technology, where models have already been developed for measuring machines equipped with contact measuring heads, articulated arm CMMs, and multisensor systems equipped with video probes for 2D measurements. This experience could be used as a starting point for extending the methodology to 3D optical scanners and for further development of simulation approaches for uncertainty estimation.

Integration of additional sensing modalities and automated pose optimization algorithms may also further improve the robustness and efficiency of large-volume hybrid measurement systems.

5. Conclusions

Three main conclusions come out of the analysis of presented work and experiment results:

- It is possible to use the hybrid measuring system developed within the work described in this paper for measurement of large-volume workpieces that are used in different branches of industry. This conclusion alone would not be significant, but when pointed out with conclusions 2 and 3, it shows that not only can the developed HMS be applied for measurement of large-volume workpieces, but additionally, the quality (which in the case of such measurement methods may be proven by confirming the high accuracy of performed measurements) of this application is high.

- Results of measurements performed using the developed HMS along with their uncertainties determined with use of the uncertainty determination method that was also developed by authors of this paper are metrologically consistent with the results of material standards’ calibrations performed with micrometric uncertainties.

- A comparison of results obtained using the developed HMS and uncertainty determination method with results obtained using another uncertainty determination method that is based on normative documents and commonly used by practitioners of dimensional metrology shows that the results of measurements done with the HMS are statistically consistent with the results obtained using the already validated and well-established method. This proves that the developed HMS may be correctly used for basic dimensional metrology tasks known from a geometrical dimensioning and tolerancing framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and A.S.; methodology, W.H. and T.K.; validation, A.G., P.G. and M.J.; investigation, N.S. and K.S.; data curation, A.G. and A.W.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G., P.G., T.K., M.J. and K.S.; writing—review and editing, W.H., P.G., A.S., N.S. and A.W.; visualization, A.G. and W.H.; supervision, A.G.; funding acquisition, A.G., T.K., M.J. and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Scientific work/publication co-financed from the state budget under the program of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Poland) called “Polska Metrologia” (Polish Metrology), project number PM/SP/0058/2021/1 titled: “Development of the basis for hierarchical measurements of large engineering structures using point-measurement and field-measurement methods (Opracowanie podstaw hierarchicznych pomiarów dużych obiektów inżynierskich z wykorzystaniem metod punktowych i polowych)”, grant amount 999 900.00 PLN, the total value of the project 999 900.00 PLN.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HMS | Hybrid Measuring System |

| CMM | Coordinate Measuring Machine |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

References

- Schmitt, R.H.; Peterek, M.; Morse, E.; Knapp, W.; Galetto, M.; Härtig, F.; Goch, G.; Hughes, B.; Forbes, A.; Estler, W.T. Advances in Large-Scale Metrology—Review and future trends. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 2, 643–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estler, W.T.; Edmundson, K.L.; Peggs, G.N.; Parker, D.H. Large-Scale Metrology—An Update. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2002, 51, 587–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peggs, G.N.; Maropoulos, P.G.; Hughes, E.B.; Forbes, A.B.; Robson, S.; Ziebart, M.; Muralikrishnan, B. Recent Developments in Large-Scale Dimensional Metrology. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2009, 223, 571–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.G.; Yang, X.Y. Distributed Optical Sensor Network with Self-Monitoring Mechanism for Accurate Indoor Location and Coordinate Measurement. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 190–191, 972–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, R.; Jatzkowski, P.; Janssen, M.; Bertelsmeier, F. Self-Optimization in Large Scale Assembly. Procedia Eng. 2013, 63, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenke, H.; Neuschaefer-Rube, U.; Pfeifer, T.; Kunzmann, H. Optical Methods for Dimensional Metrology in Production Engineering. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2002, 51, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisano, D.A.; Jamshidi, J.; Franceschini, F.; Maropoulos, P.G.; Mastrogiacomo, L.; Mileham, A.R.; Owen, G.W. Indoor GPS: System Functionality and Initial Performance Evaluation. Int. J. Manuf. Res. 2008, 3, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sładek, J.; Błaszczyk, P.M.; Kupiec, M.; Sitnik, R. The hybrid contact–optical coordinate measuring system. Meas 2011, 44, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q. Complete 3D measurement in reverse engineering using a multi-probe system. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2005, 45, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Longstaff, A.P.; Fletcher, S.; Myers, A. A practical coordinate unification method for integrated tactile–optical measuring system. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2014, 55, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckenmann, A.; Jiang, X.; Sommer, K.D.; Neuschaefer-Rube, U.; Seewig, J.; Shaw, L.; Estler, T. Multisensor data fusion in dimensional metrology. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2009, 58, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gąska, A.; Gąska, P.; Gruza, M.; Harmatys, W.; Kowaluk, T.; Styk, A.; Jakubowicz, M.; Wójtowicz, A.; Wiśniewski, M.A.; Sładek, J. Traceability Assurance Method for Measurements Performed Using Hybrid Measuring Systems Consisting of Tactile and Optical Devices. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2024, 18, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghi, B.; Khamis, A.; Karray, F.O.; Razavi, N.A. Multisensor data fusion: A review of the state-of-the-art. Inf. Fusion 2014, 14, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colosimo, B.M.; Pacella, M.; Senin, N. Multisensor data fusion via Gaussian process models for dimensionaland geometric verification. Precis. Eng. 2015, 40, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rena, M.J.; Suna, L.J.; Liub, M.Y.; Cheungb, C.F.; Yina, Y.H.; Caoc, Y.L. A weighted least square based data fusion method for precisionmeasurement of freeform surfaces. Precis. Eng. 2017, 48, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Liu, Q.; Bai, M.; Sun, P. A Multisensor Data Fusion Method Based on Gaussian Process Model for Precision Measurement of Complex Surfaces. Sensors 2020, 20, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaisarlis, G.; Gikas, V.; Xenakis, T.; Stathas, D.; Provatidis, C. Combined use of Total Station and Articulated Arm Coordinate Measuring Machine on Large Scale Metrology Applications. In Proceedings of the 21th IMEKO World Congress, Prague, Czech Republic, 30 August–4 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R.S.; Li, Y.F. A global calibration method for large-scale multi-sensor visual measurement systems. Sens. Actuators 2004, 116, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tao, B.; Gong, Z.; Yu, S.; Yin, Z. A Mobile Robotic Measurement System for Large-scale Complex Components Based on Optical Scanning and Visual Tracking. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2021, 67, 102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 15530-3:2011; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMM): Technique for Determining the Uncertainty Of Measurement—Part 3: Use of Calibrated Workpieces or Measurement Standards. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- ISO/TS 15530-4:2008; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMM): Technique for Determining the Uncertainty of Measurement—Part 4: Evaluating Task-Specific Measurement Uncertainty Using Simulation. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Kacker, R.N.; Kessel, R.; Sommer, K.D.; Bian, X. Comparison of statistical consistency and metrological consistency. In Proceedings of the XIX IMEKO World Congress, Lisbon, Portugal, 6–11 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kacker, R.N.; Kessel, R.; Sommer, K.D. Metrological compatibility and statistical consistency. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Measurement and Quality Control, Osaka, Japan, 5–9 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gromczak, K.; Gąska, A.; Kowalski, M.; Ostrowska, K.; Sładek, J.; Gruza, M.; Gąska, P. Determination of validation threshold for coordinate measuring methods using a metrological compatibility model. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2017, 28, 015010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.