Abstract

The on-machine measurement (OMM) of aero-engine blades is a critical technology for enabling closed-loop manufacturing. However, when using line laser sensors with a fixed scanning pose to measure free-form surfaces, the variation in surface geometry leads to changing incident angles, which in turn induce non-stationary noise. To address this issue, this paper proposes a multi-sensor fusion method utilizing Adaptive Heteroscedastic Gaussian Process Regression (AHGPR) based on a Spatial-Angle-Balanced Sampling (S-ABS) strategy. The AHGPR explicitly integrates the physical mapping of incident angle errors into its covariance structure, thereby automatically adjusting observation weights according to the local geometric posture. Concurrently, the S-ABS strategy captures the high-error characteristic points with large incident angles while maintaining a globally uniform spatial distribution. The experimental data indicate that this approach addresses the sampling deficiency encountered at the leading and trailing edges and in areas with large incident angles. The proposed approach reduced the impact of optical deviations on measurement accuracy and improved the precision of the process.

1. Introduction

The high-precision machining of curved thin-walled parts is a critical demand in fields such as the aerospace industry [1,2]. However, their inherent weak rigidity makes them prone to deformation during the manufacturing process [3,4,5,6], making it difficult to guarantee final accuracy. Traditional machining modes lead to a severe mismatch between the measured state and the machining state. On-machine measurement (OMM) technology has become a core link in realizing high-precision closed-loop machining of thin-walled parts by completing dimensional and geometric error detection directly on the machine tool.

OMM generally employs contact probe measurement. While this method can yield high-precision results [7], its efficiency is low. Non-contact measurement can efficiently acquire point cloud data of the workpiece surface, but it is susceptible to its own structural and environmental factors, resulting in insufficient accuracy that often fails to meet the machining precision requirements of thin-walled parts [8]. Given that no single measurement method can satisfy both precision and efficiency requirements, integrating the complementary strengths of contact and non-contact sensors has become an inevitable choice.

Existing research focuses on post-process fusion algorithms for multiple sensors, primarily categorized into two classes: weighted fusion methods and Residual Approximation (RA)-based fusion methods. Weighted fusion is applicable to sensors with similar accuracy but has limited effectiveness for data sources with different resolutions [9]. RA fusion approximates the systematic deviation (residual) between two separate datasets from different sensors; such methods can reduce the uncertainty of fusion results. Among RA modeling methods, Gaussian regression models are the most widely applied, offering advantages in handling nonlinear relationships and fusing multi-source heterogeneous data [10,11,12]. Chen [13] et al. further proposed the Implicit Residual Approximation (IRA) method, utilizing Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) to achieve the implicit expression of local residuals.

Research on sampling methods for contact probes has mainly focused on single-sensor sampling. Jia [14] et al. combined the equal chord height sampling method and the curvature distribution method to optimize the layout of sampling points by dynamically setting the chord height threshold and adding sampling midpoints. Zhang [15] et al., based on the co-Kriging method, iteratively determined the distribution of measurement points using feature anchor points; this approach utilizes the main variable and auxiliary variable as dual inputs and quantifies their correlation through a covariance matrix to complete interpolation reconstruction. A small number of multi-sensor collaborative sampling studies, such as the intelligent sampling strategy proposed by Yin [16], involve obtaining an initial high-density point cloud through laser scanning and modeling it, iteratively optimizing the positions of contact measurement points based on model deviation and variance criteria. However, few studies have improved data fusion algorithms by incorporating the measurement principles of non-contact sensors.

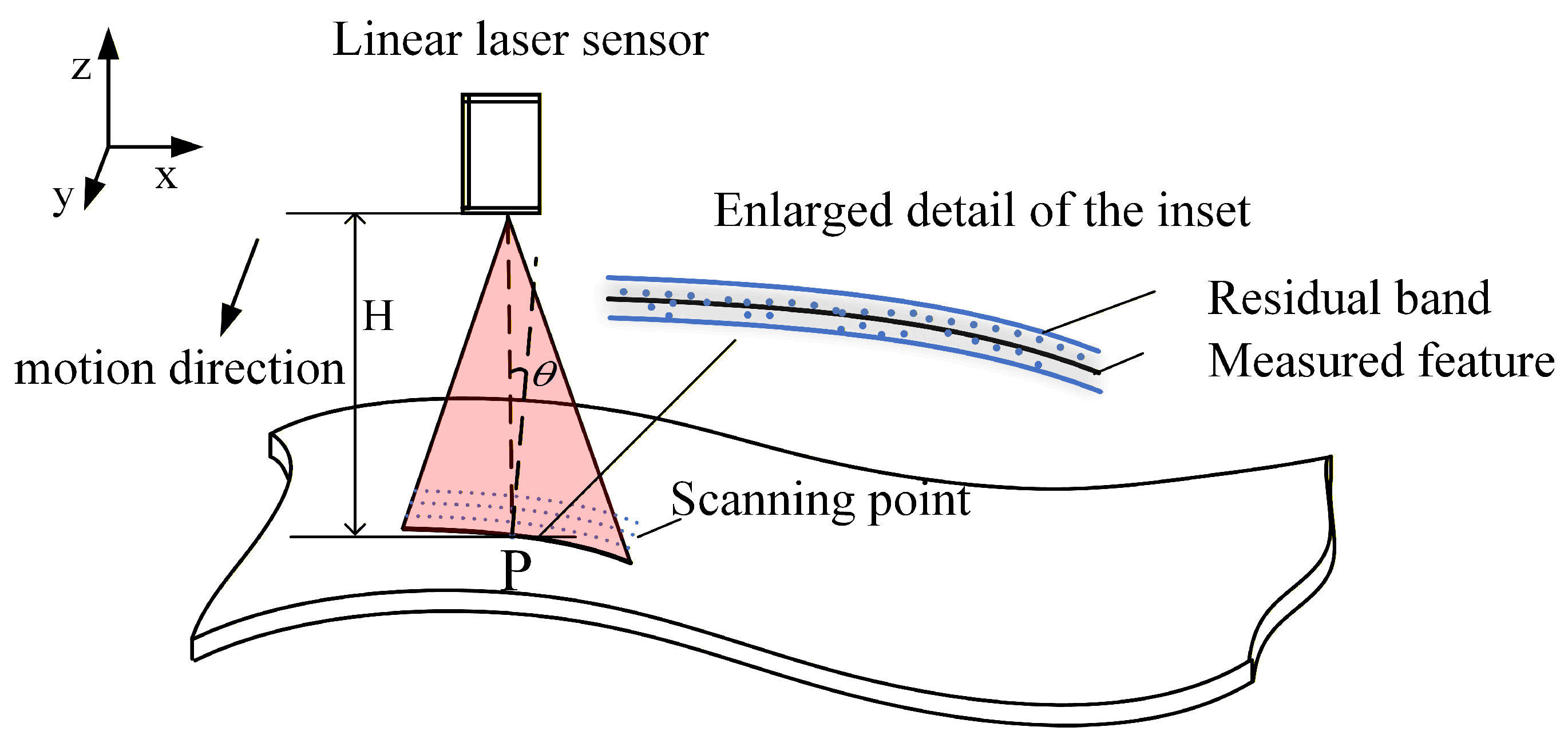

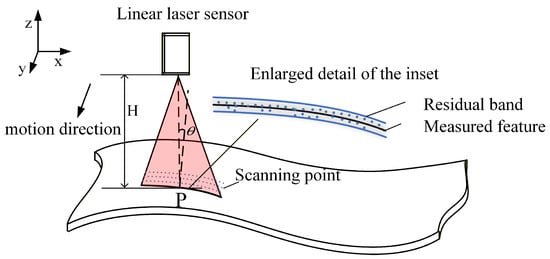

The measurement method of line laser sensors is based on the principle of optical triangulation. Dong et al. [17] pointed out that, theoretically, optimal accuracy is achieved only under conditions of vertical incidence and symmetric laser spot energy distribution. In actual curved surface measurements, as shown in Figure 1, a partitioned fixed-pose scanning strategy is often adopted in industrial settings to balance on-machine measurement efficiency. Research by An et al. [18] indicates that this alteration in geometric relationships disrupts the symmetry of the imaging spot. Further analysis by Wang et al. [19] confirmed that the inclination angle causes a nonlinear shift in the spot centroid, thereby introducing significant measurement errors. Zhao et al. [20] verified through on-machine measurement experiments that this error exhibits a positive correlation with the incident angle. Furthermore, work by Ding et al. [21] and Deng et al. [22] revealed that, in regions with high curvature, such as blade edges, the measurement noise variance rises sharply, presenting distinct Heteroscedastic characteristics.

Figure 1.

Line laser sensor measurement of curved surface parts.

Existing multi-sensor fusion algorithms are predominantly based on the Homoscedasticity assumption and have demonstrated good applicability in conventional measurements. However, under conditions involving varying incident angles generated by fixed-pose scanning, there remains potential to further enhance surface measurement accuracy through more refined modeling of non-stationary error distributions.

Therefore, to address the non-stationary error distribution induced by partitioned fixed-pose scanning in the on-machine measurement of aero-engine blades, this paper proposes a multi-sensor fusion on-machine measurement method based on Spatial-Angle-Balanced Sampling (S-ABS) and Adaptive Heteroscedastic Gaussian Process Regression (AHGPR). By refining the sampling methodology for high-precision points and improving the Gaussian regression model, the proposed method enhances measurement accuracy while simultaneously ensuring the efficiency of on-machine measurement.

2. Methods

In multi-sensor data fusion, Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) is widely used to establish error models between low-accuracy and high-accuracy data. Take a noisy observation set, , where is the spatial coordinate and is the measurement residual. Assume the latent residual function follows a Gaussian Process prior:

Assuming the mean function, , the covariance function describes the correlation between points. The observation model includes additive Gaussian white noise:

Based on Bayesian inference, for any test point , its posterior predictive distribution is analytically solved as:

where is the kernel matrix, is the covariance vector between the test point and the training points, is the observation noise covariance term, and is the identity matrix, indicating the model assumes the full-field measurement noise follows a Homoscedastic distribution. However, when applying the standard GPR framework to the specific measurement working conditions of aero-engine blades, there are two mismatches between theoretical assumptions and actual working conditions:

(1) Standard GPR employs a stationary kernel function, whose core characteristic is that correlation relies solely on Euclidean distance. As known from Equation (4), the posterior variance, , is independent of the observation values, [23]. To minimize full-field prediction uncertainty, standard GPR mathematically tends towards space-filling sampling strategies, covering the geometric space as uniformly as possible [24]. However, this strategy based on minimizing global variance often ignores the local features of the workpiece being measured, leading to under-sampling in areas with high residuals.

(2) The Homoscedastic term, , in Equation (1) enforces the assumption that the full-field confidence is consistent. This contradicts the characteristic in laser measurement where noise increases with the incident angle, [25]. The limitation of this assumption leads to the global optimized being higher than actual noise in low-noise areas, causing the surface to be over-smoothed; meanwhile, in high-noise areas, the global is lower than actual noise, forcing the model to track random errors, reducing measurement accuracy [26].

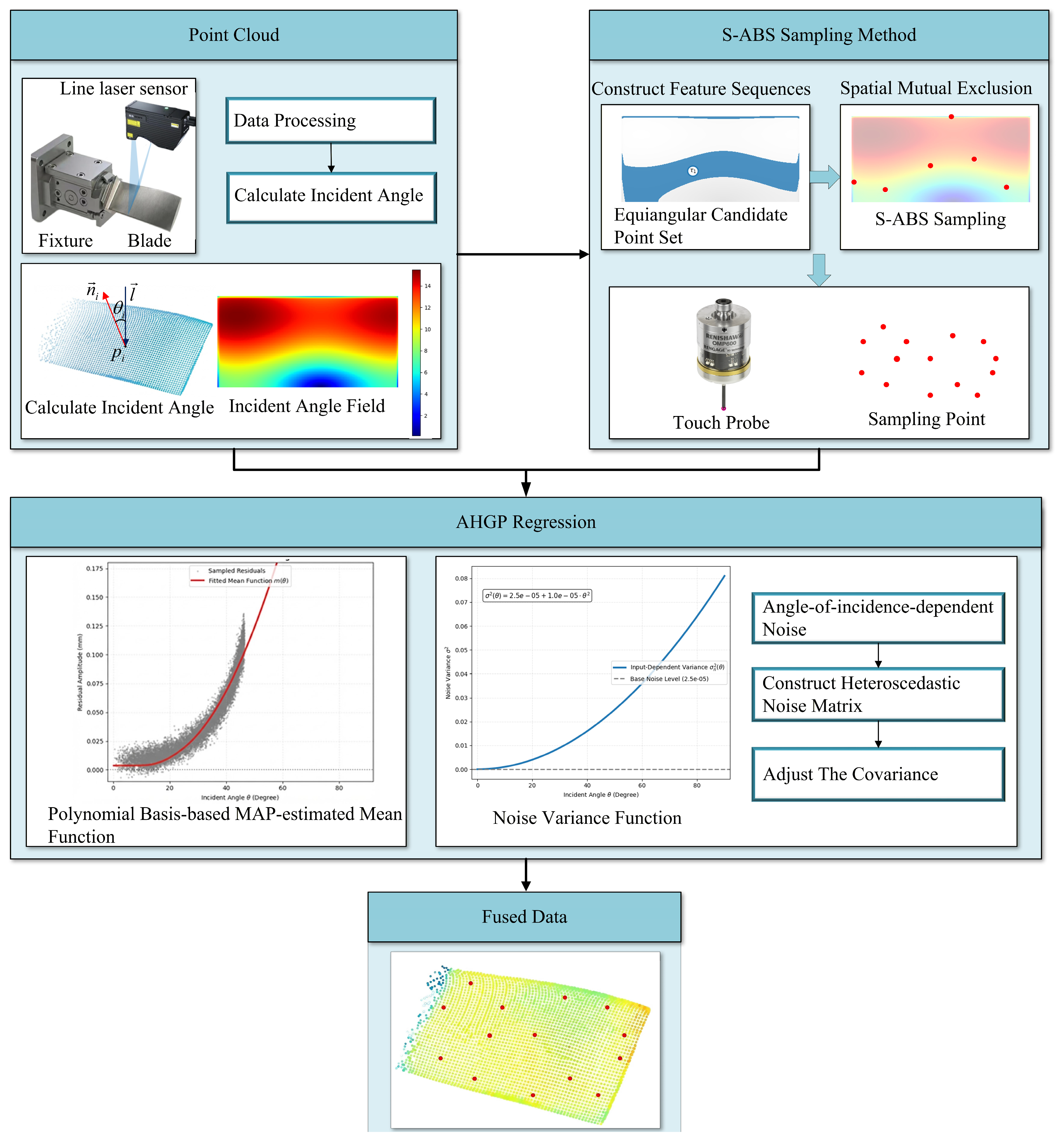

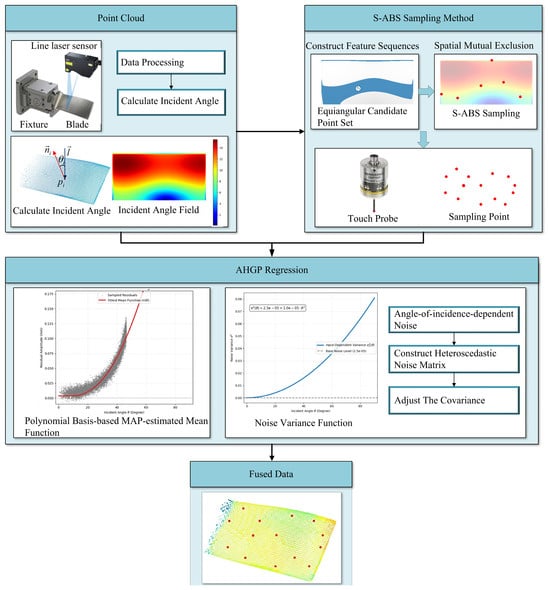

In response to the analysis of the aforementioned issues, the Spatial-Angle Sampling-Based Adaptive Heteroscedastic Gaussian process multi-sensor fusion method simultaneously considers a balanced sampling strategy for both spatial coordinates and incidence angles, and introduces a Heteroscedastic model consistent with optical error laws to adaptively suppress non-stationary noise. The schematic framework of the overall methodology is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic framework of the proposed multi-sensor fusion method using S-ABS and AHGPR.

2.1. Spatial-Angle-Balanced Sampling

This study proposes an S-ABS strategy designed to perform balanced sampling within the constrained domain of the point cloud data, . Initially, the point cloud undergoes pre-processing, where the full-field incident angle distribution field, , is reconstructed via Gaussian smoothing. Considering the strong nonlinear mapping relationship between the measurement error, , and the incident angle, (i.e., ), and to ensure the subsequent model comprehensively captures the error response characteristics, the algorithm first constructs a discretized feature target sequence, , within the incident angle range, . This sequence consists of equally spaced feature angles, , explicitly enforcing the inclusion of boundary anchor points:

For any target feature, , an angular tolerance, , is introduced to delimit an effective truncation interval centered at . The algorithm traverses the discrete geometric domain, , to filter all point cloud data where the incident angle, , falls within , thereby constructing an iso-angular candidate set, , corresponding to the specific angle:

However, relying solely on incident angle features tends to induce clustering of sampling points in regions with large incident angles, leading to ill-conditioning of the kernel matrix. To address this, the strategy introduces a spatial exclusion mechanism constrained within the candidate domain. Let denote the sampling set generated over the previous steps. The -th optimal sampling point, , is transformed into the solution to a max–min distance optimization problem over :

This optimization problem is solved using a greedy search strategy. First, for any point, , in the current set, , its spatial separation, , relative to the existing sampling set, , is calculated as the Euclidean distance to the nearest neighbor sampling point:

Subsequently, the -th optimal sampling point, , is identified as the solution within that maximizes this separation:

This procedure integrates incident angle features with geometric spatial distribution: the constraint ensures the sampling point aligns with the preset incident angle, while the objective function compels the new point to maintain maximum distance from the existing sampling set in geometric space. This effectively maintains spatial separation within the targeted feature region. The optimal solution is then incorporated into the sampling sequence, updating the state to . After iterations, the algorithm outputs the final sampling set .

2.2. Adaptive Heteroscedastic Gaussian Process Regression

Standard GPR assumes that observation noise follows independent and identically distributed Gaussian white noise; that is, the noise covariance is . To this end, this paper establishes an Adaptive Heteroscedastic Gaussian Process (AHGPR) model, embedding the angle information obtained by S-ABS into the covariance structure.

The high-confidence ground truth points in are utilized to construct the global trend term. The mean function in the Gaussian Process prior of the residual function is no longer set to zero, but is determined by the Maximum A Posteriori (MAP) estimation of the samples in through the polynomial basis function ; that is, .

In contrast to the scalar noise parameter used in standard GPR, an input-dependent noise variance function is defined. The observation noise comprises a superposition of environmental noise and angle-dependent noise. Specifically, the dispersion effect of the laser spot on inclined surfaces results in measurement uncertainty that is positively correlated with the incident angle . Consequently, the observation noise matrix can be expressed as:

where the diagonal elements are defined by:

where represents the incident angle at the sampling point; denotes the sensitivity coefficient regarding the sensor spot centroid shift; and serves as the environmental adaptive noise baseline, characterizing the global uncertainty introduced by current measurement conditions. In this case, the total covariance matrix for the training data is modified to be the superposition of the kernel matrix and the Heteroscedastic noise matrix is:

Leveraging the Heteroscedastic covariance structure constructed above, the model dynamically adjusts its confidence in observational data based on local incident angles. For any test point within the domain, the predictive mean and posterior variance of the AHGPR are derived as:

Consequently, the AHGPR method establishes an adaptive prediction framework. By incorporating the Heteroscedastic covariance structure via Equation (12), the model automatically down-weights observations in regions with large incident angles, while preserving the capture of fine measurement details in regions with small incident angles.

3. Experimental Validation

3.1. Simulation Case

3.1.1. Setting of Simulation Experiment Conditions

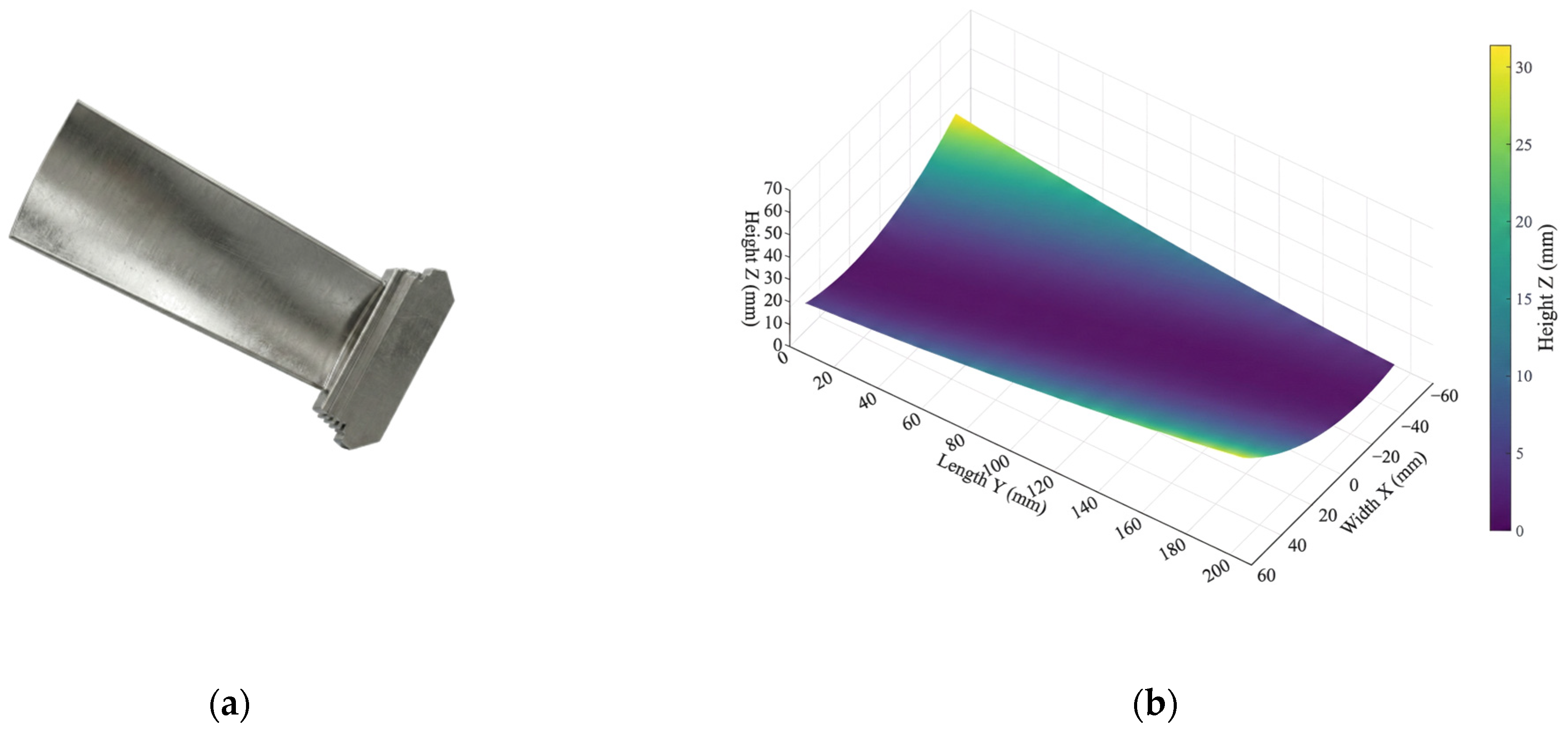

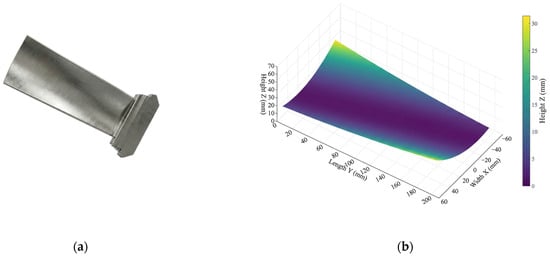

Based on the typical geometric topological features of aero-engine turbine blades, a simulation benchmark surface with a domain of is constructed, as shown in Figure 3. The surface is generated by sweeping a quadratic parabolic generatrix along the oblique ridge trajectory to replicate the continuously varying curvature and spatial twist of the blade profile.

Figure 3.

Simulation blade geometric model: (a) actual blade; (b) ideal ground truth surface.

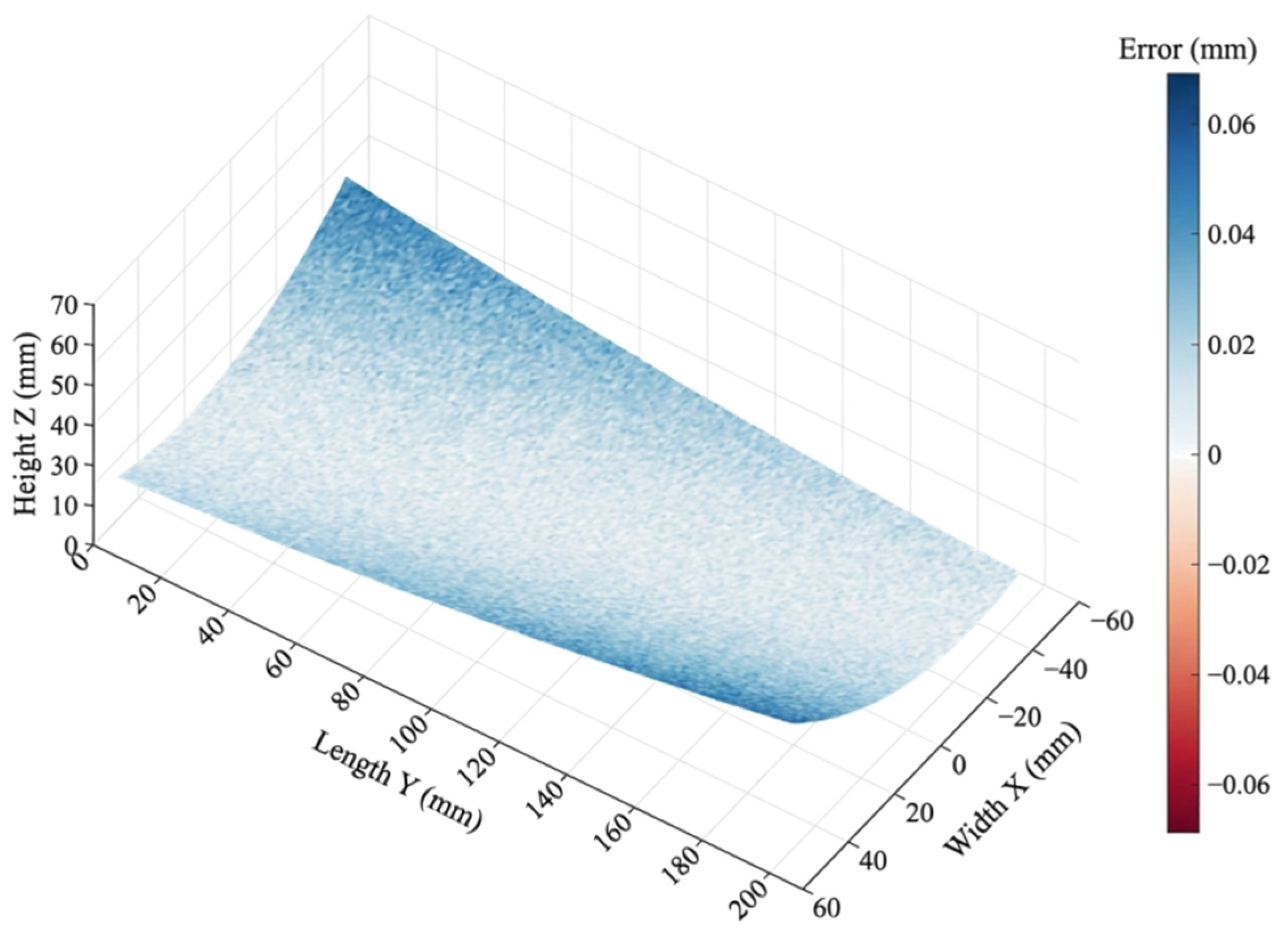

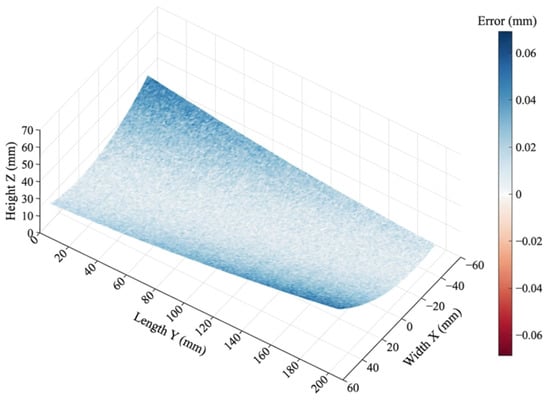

The total error for any given measurement point is defined as the superposition of the sensor’s inherent linearity error , the systematic bias induced by the incident angle , and the random noise . Consequently, the simulated measurement value is expressed as Equation (1), while the corresponding simulated data and error distribution are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Simulation measurement data and error distribution.

3.1.2. Simulation Experiment Analysis

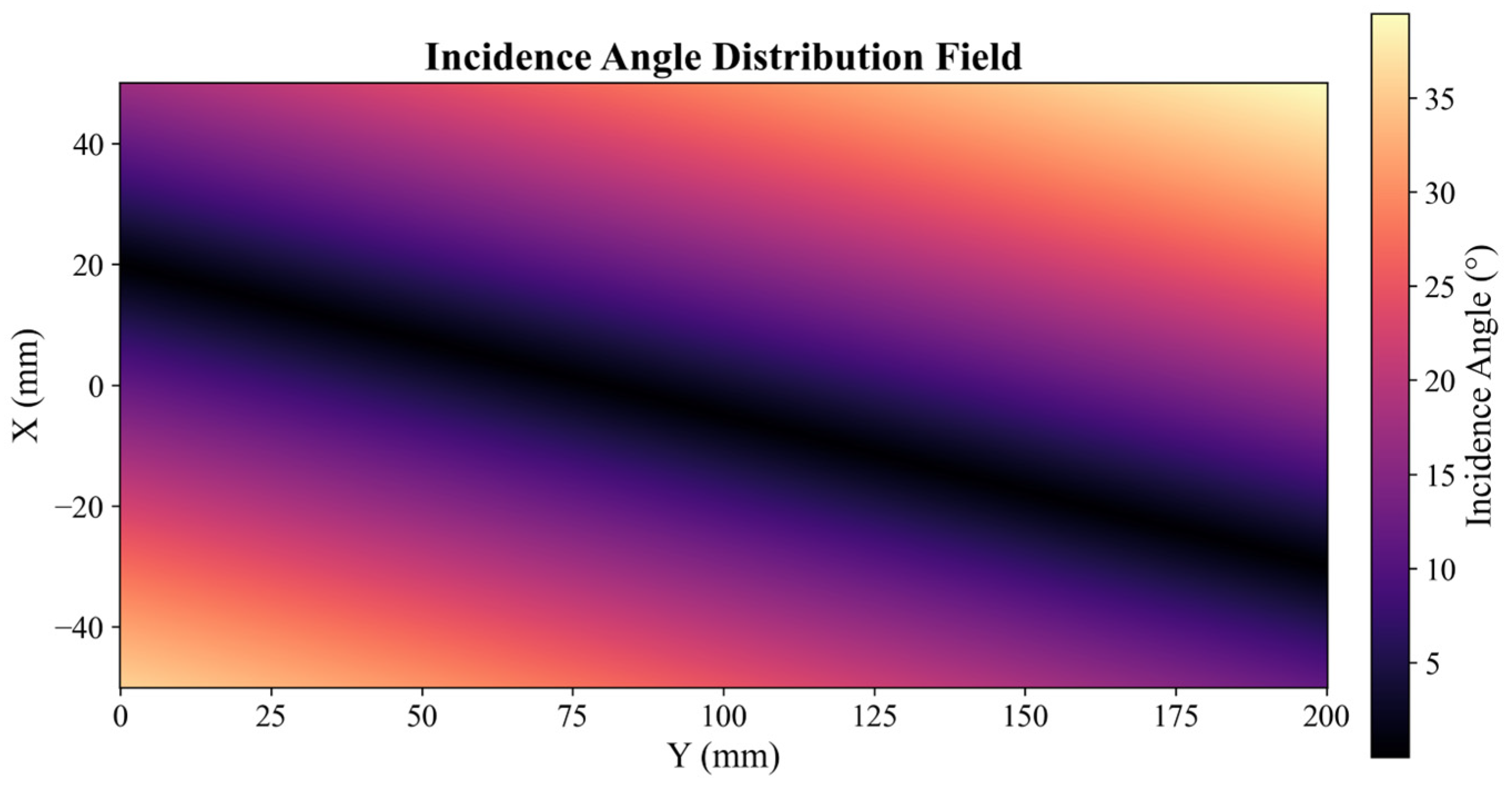

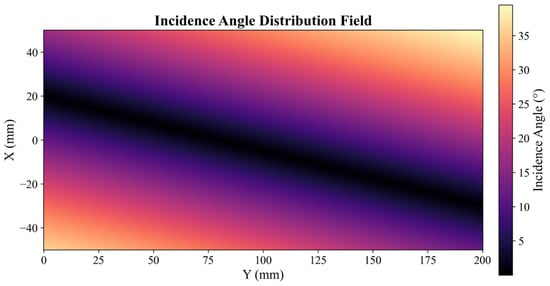

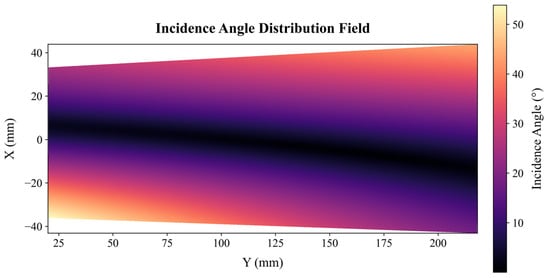

The normal vectors of the preprocessed point cloud data were calculated, and the angles between them and the incident direction of the laser sensor were also determined. The resulting incident angle distribution field of the line laser sensor is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Simulated incident angle distribution field.

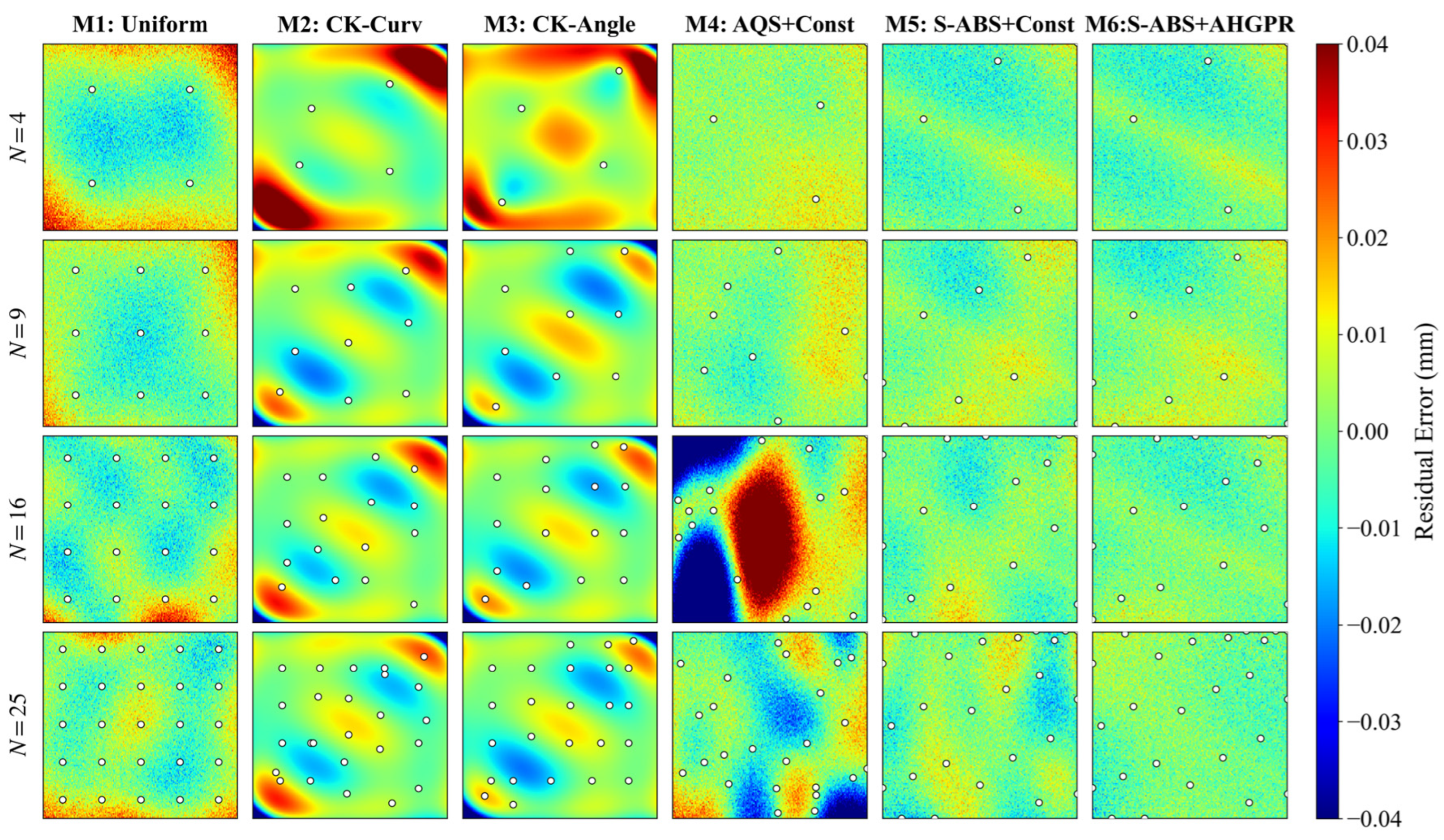

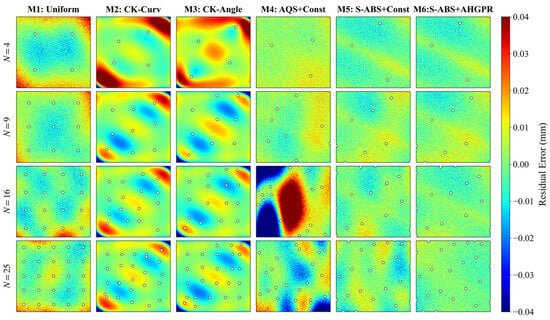

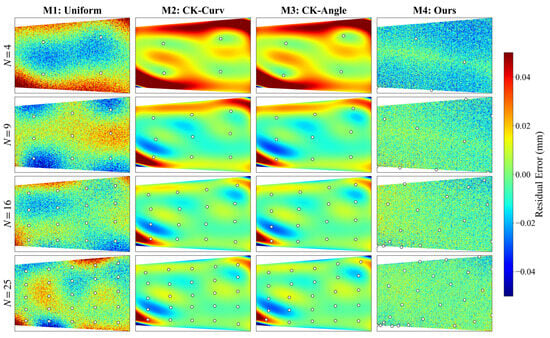

Figure 6 illustrates the error distributions across varying sampling densities and distinct multi-sensor fusion strategies. M1 represents the traditional fusion approach employing uniform sampling with a Homoscedastic GPR. M2 and M3 denote Co-Kriging fusion methods based on curvature and incident angle sampling, respectively. M4 corresponds to Homoscedastic GPR fusion with angle-based sampling, while M5 and M6 employ S-ABS sampling combined with Homoscedastic GPR and Heteroscedastic GPR, respectively. M1 is employed as the comparative baseline.

Figure 6.

Simulated error distribution diagrams of different fusion methods.

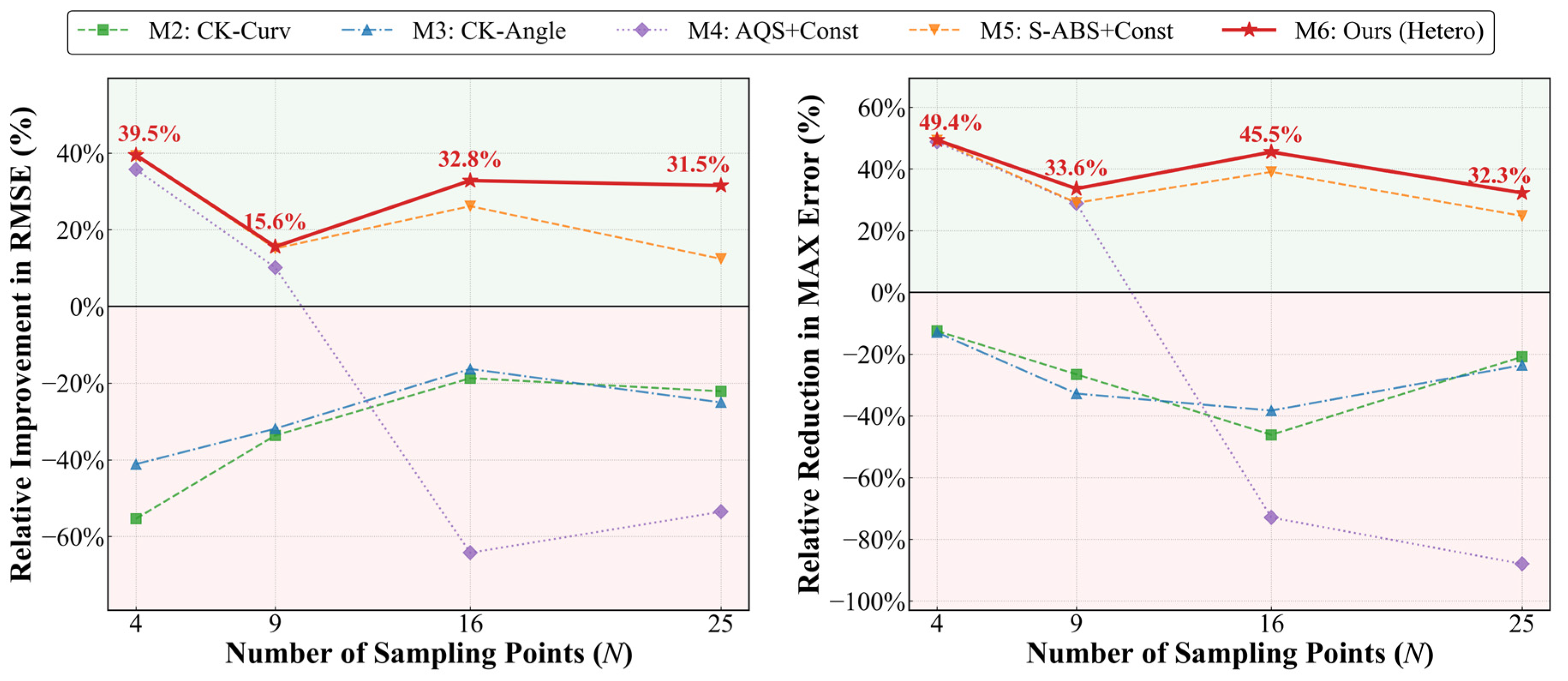

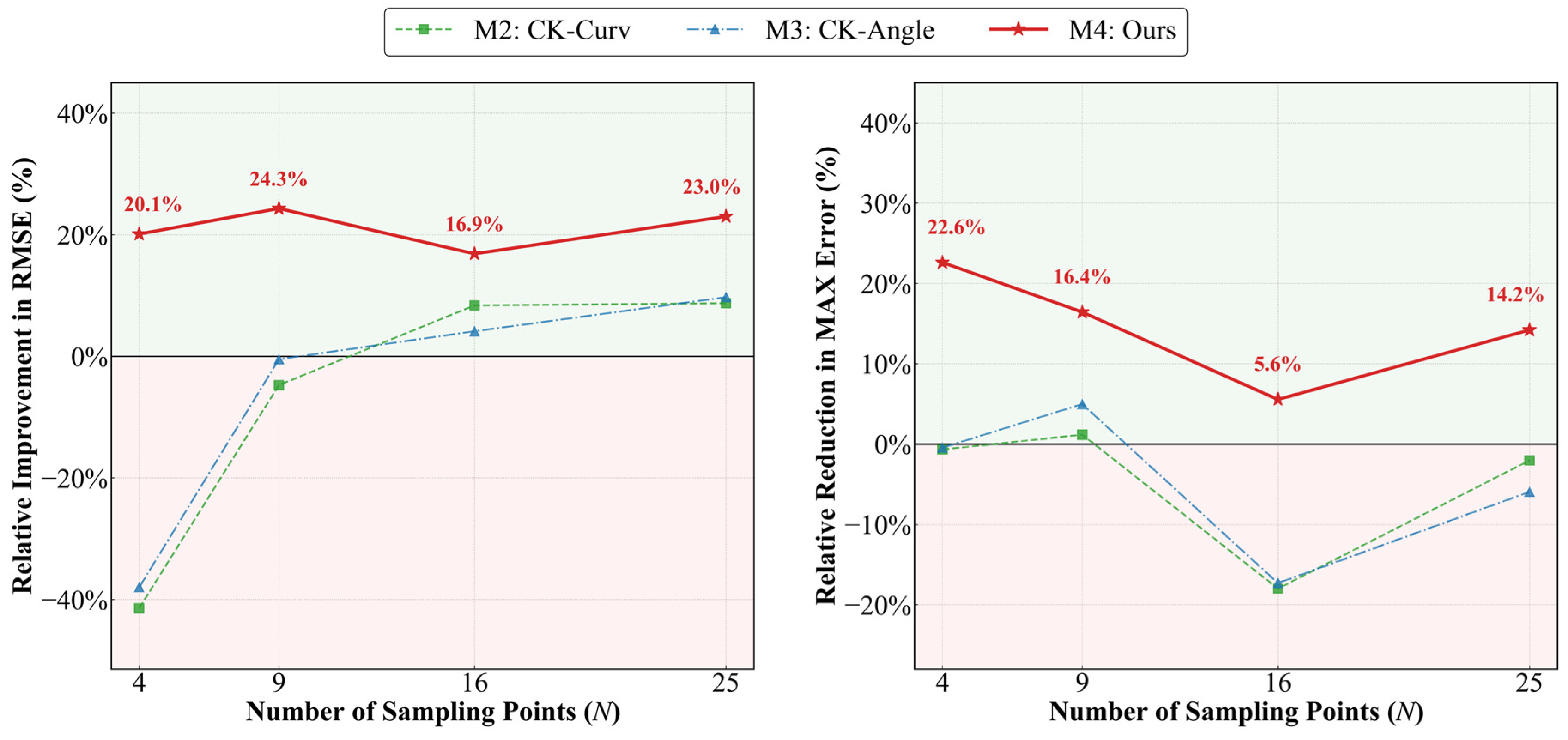

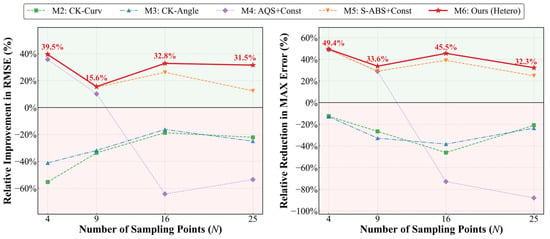

Table 1 presents the experimental results, while Figure 7 illustrates the error improvement of various fusion methods relative to M1.

Table 1.

Simulated RMSE and maximum error of different fusion methods.

Figure 7.

Simulated error improvement effects of different fusion methods relative to M1.

(1) Comparison between Gaussian Process Regression (GPR)-based methods (M1, M4–M6) and Co-Kriging-based methods (M2, M3): As illustrated on the left side of Figure 6, at a low sampling density of , the RMSE of the Gaussian-based methods is lower than that of the Co-Kriging methods. This discrepancy diminishes as sampling density increases. The reliance of Co-Kriging theory on sample size constrains the accurate estimation of cross-covariance parameters under sparse sampling conditions. Furthermore, acting as an exact interpolator with an inherent all-pass characteristic, the Co-Kriging model struggles to filter observation noise, resulting in local overfitting oscillations. Figure 6 reveals distinct error fluctuations for M2 and M3 at the boundaries, with maximum errors reaching 0.0686 . Conversely, GPR models the noise term independently, offering superior smoothing capabilities. Consequently, it demonstrates greater noise robustness and numerical stability when sampling points are scarce.

(2) Comparison of sampling strategies within the Homoscedastic GPR framework: Although M4 achieves an RMSE reduction of approximately 39.5% relative to M1 with sparse sampling (), Figure 7 indicates that it exhibits poor stability. As illustrated in Figure 7, at , the accuracy of M4 deteriorates, with its RMSE exceeding that of the benchmark method M1. This degradation is attributed to the angle-guided sampling, which causes under-sampling at the surface center, leading to a maximum error of 0.08121 . M5 integrates angular and spatial distributions, effectively mitigating the local under-sampling issue of M4. Quantitative results indicate that at , the MAX error of M5 decreases to 0.02861 compared to M4, and the RMSE is reduced by 26% relative to M1. This demonstrates the robust performance of the S-ABS algorithm in non-stationary error fields. Furthermore, even under the Homoscedastic assumption, the fusion accuracy of M5 surpasses those of the M2 and M3 methods.

(3) Comparison between the Heteroscedastic (M6) and Homoscedastic (M5) models: As illustrated in Figure 6, while M5 resolves under-sampling issues in certain regions, residual errors persist at the blade edges. Conversely, M6 exhibits a more uniform error distribution across the entire domain, with a marked reduction in edge errors. Table 1 and Figure 7 indicate that M6 yields further error reductions compared to M5 at and , and achieving an RMSE reduction of approximately 31.5% relative to the baseline. This improvement is attributed to the ability of the AHGPR model (M6) to dynamically adjust weights based on local variance. Specifically, it lowers fitting weights in high-noise edge regions to filter noise, while maintaining high-precision interpolation in high-confidence central regions. Consequently, M6 enhances measurement accuracy without requiring additional sampling points.

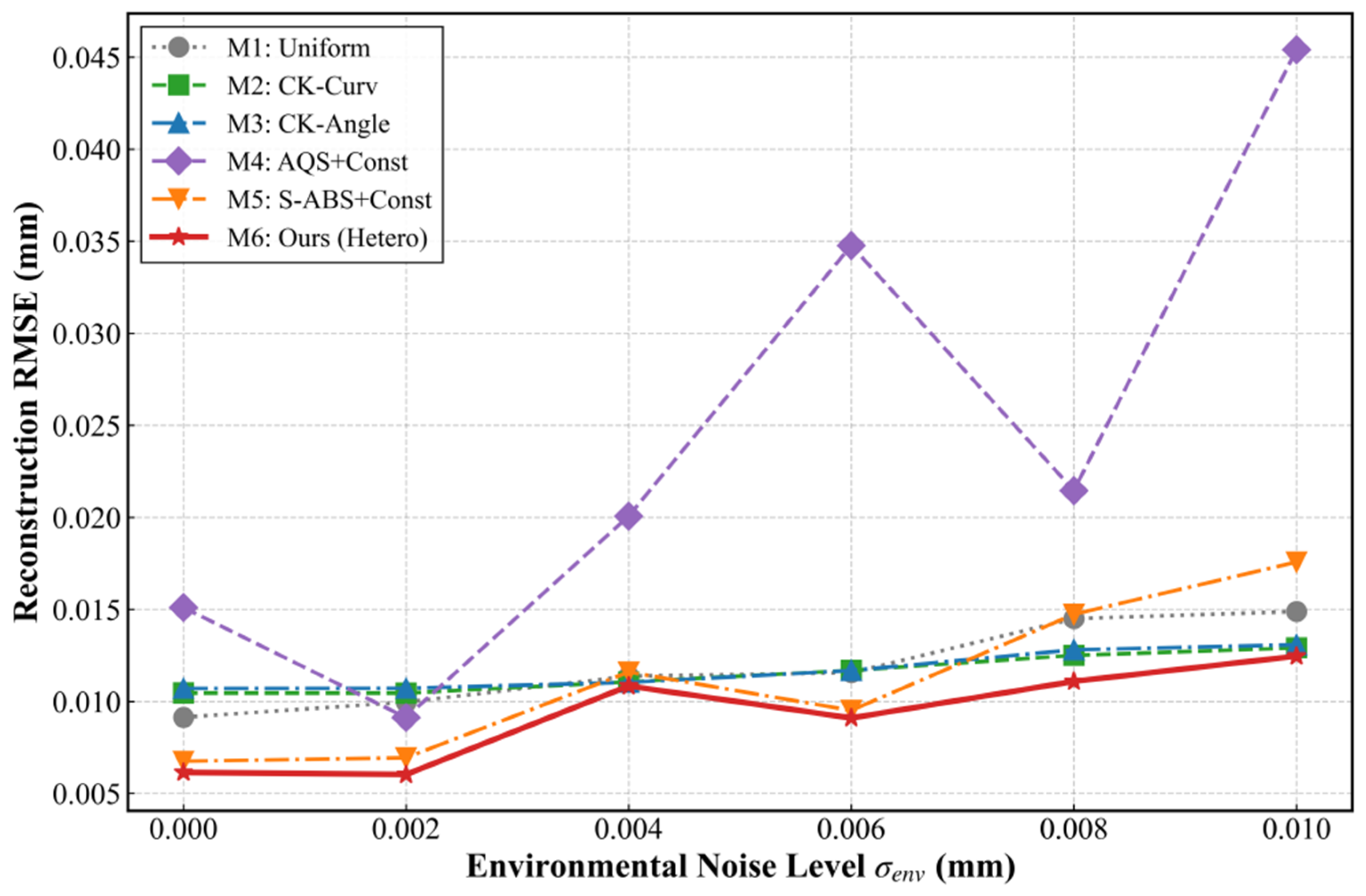

3.1.3. Noise Robustness and Computational Complexity

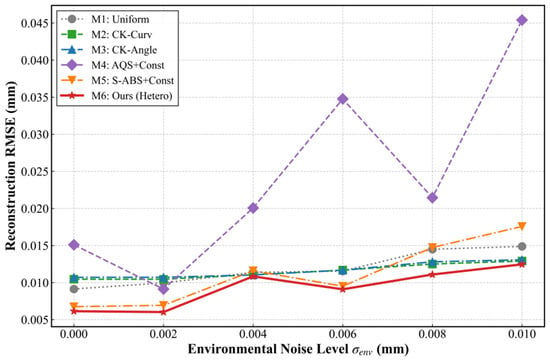

To further assess the noise robustness of the S-ABS-based adaptive Heteroscedastic GPR fusion method within actual industrial environments, random white noise with a standard deviation of was superimposed onto the fixed incident angle-dependent errors. This simulation was intended to replicate machine tool vibrations and ambient light interference. With the sampling size fixed at , variations in RMSE for the different fusion methods were recorded as the noise intensity increased.

As illustrated in Figure 8, disparities in robustness among the methods emerge as the environmental noise level rises from 0 to 0.010 . M4 shows numerical instability at high noise levels, characterized by violent nonlinear fluctuations. Conversely, the Co-Kriging methods (M2, M3) retain good stability, showing the best resistance to noise. M6 demonstrates favorable noise immunity, keeping the fusion error small and stable in strong interference environments. Nevertheless, it is slightly less robust against environmental noise compared to Co-Kriging.

Figure 8.

Robustness comparison of different fusion methods under varying environmental noise levels.

Regarding computational complexity, under identical simulation conditions with sampling points, the CK method requires the introduction of approximately auxiliary points to capture non-stationary features. This results in an increase in the covariance matrix dimension to , with a theoretical complexity of . In contrast, the AHGPR method characterizes Heteroscedastic noise by explicitly constructing a mapping function based on the incident angle, eliminating the need for auxiliary points to implicitly learn features. Consequently, its theoretical computational complexity is . Under these simulation conditions, AHGPR reduces the dimensionality of matrix inversion from order 425 to 25, thereby lowering computational complexity.

3.2. Measurement Case

3.2.1. Experimental Setup

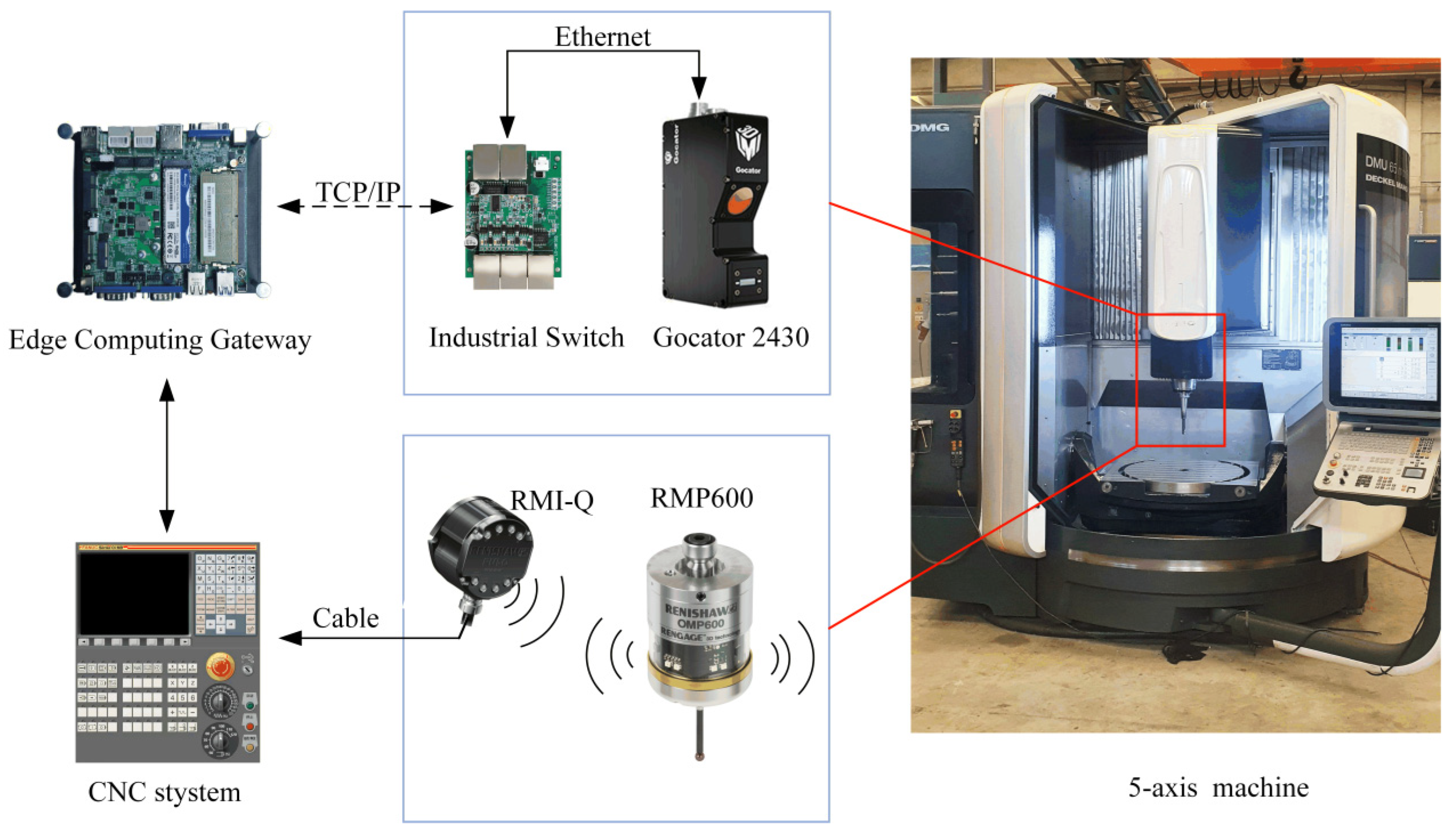

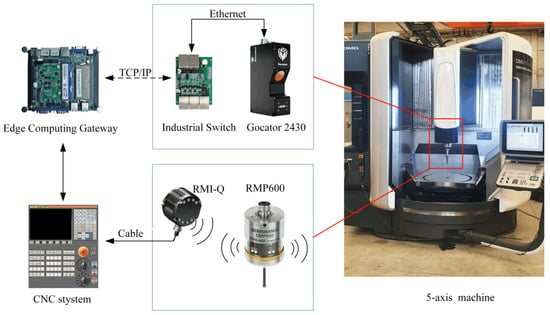

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm within a real machining environment, an on-machine measurement platform integrating multi-sensor fusion was established, as illustrated in Figure 9. The experimental setup utilizes a DMG MORI DMU 65 monoBLOCK five-axis simultaneous machining center, an LMI Technologies Gocator 2430 line laser sensor (X-axis resolution: 0.037 ; Z-axis repeatability: 0.0008 ), and a Renishaw RMP600 high-precision touch-trigger probe (unidirectional repeatability: ). Furthermore, a Hexagon Leitz Reference HP Coordinate Measuring Machine (CMM) was employed to acquire the ground truth point cloud of the blade surface, serving as the absolute benchmark for evaluating reconstruction accuracy.

Figure 9.

On-machine measurement experimental platform for multi-sensor fusion.

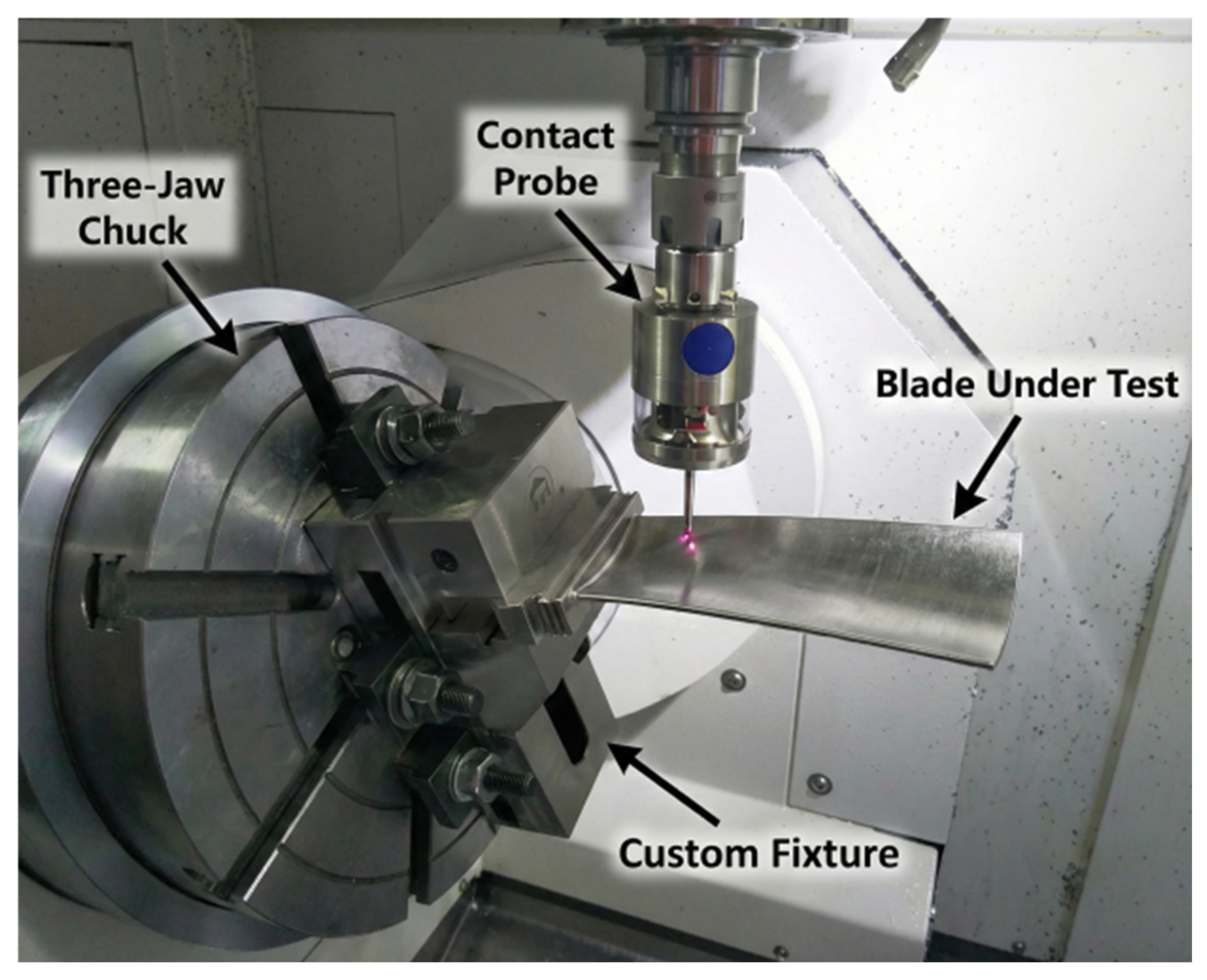

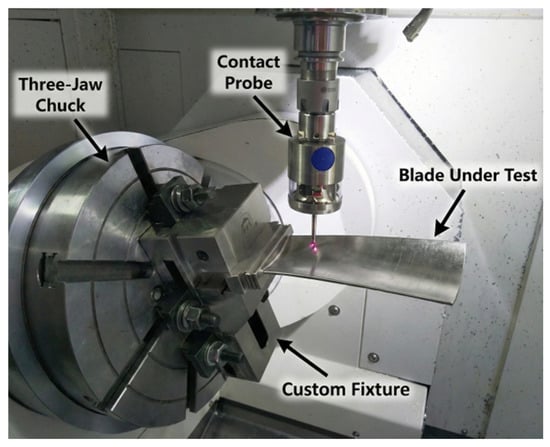

The experimental object is an aero-engine blade sample, as shown in Figure 10, and its profile projection size is . Before the measurement, each sensor must be calibrated and error-compensated, and the matching of the multi-sensor measurement data must be completed.

Figure 10.

On-machine measurement of actual blades.

3.2.2. Analysis of Measurement Experiments

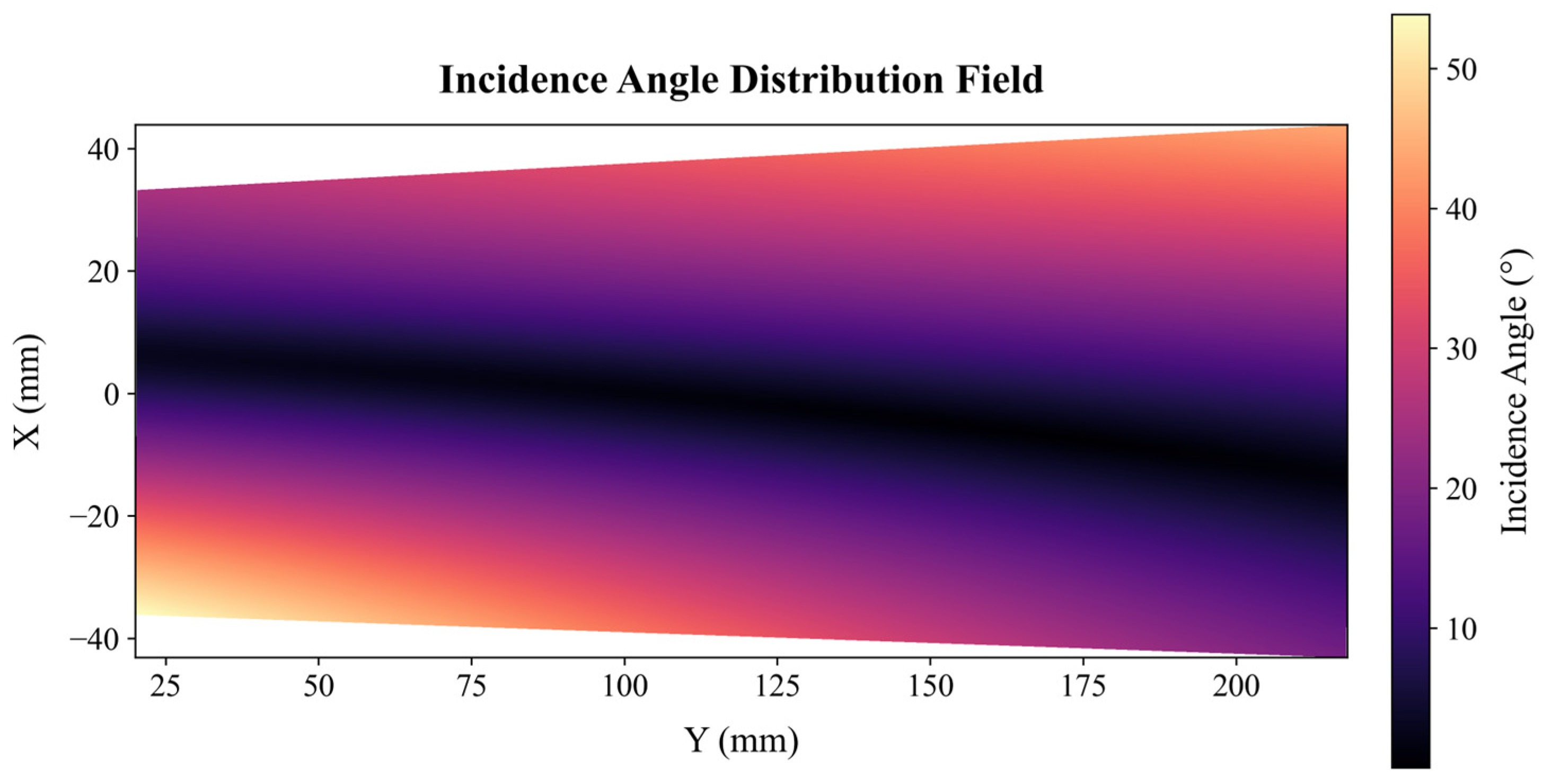

This measurement experiment conducts a comparative validation of four distinct fusion methods: M1, the Homoscedastic GPR fusion method utilizing uniform sampling; M2 and M3, Co-Kriging fusion methods based on curvature and angle sampling, respectively; and M4, the AHGPR fusion method employing S-ABS sampling. Figure 11 shows the incident angle distribution field of the actual blade profile during the experiment.

Figure 11.

Experimental incident angle distribution field.

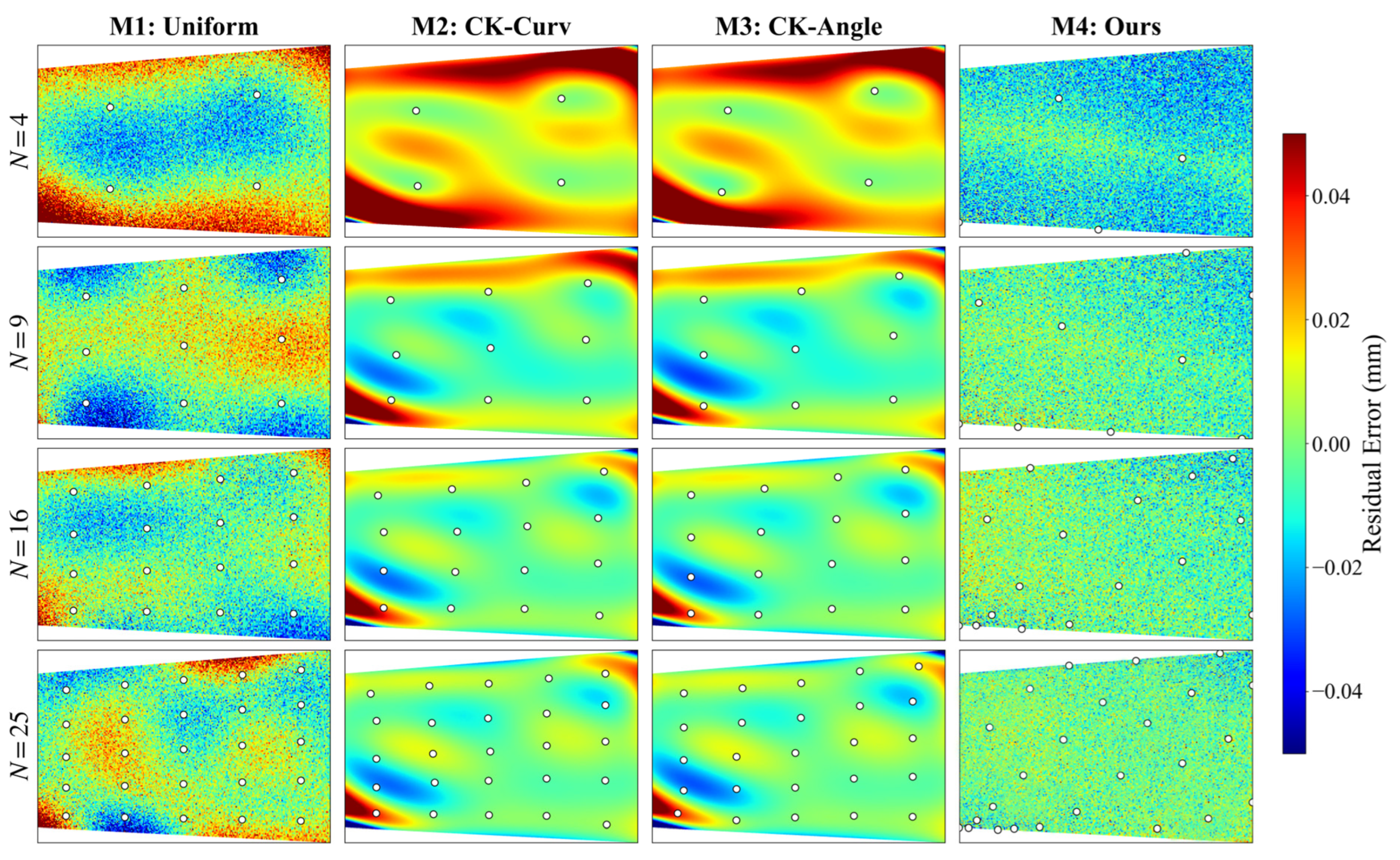

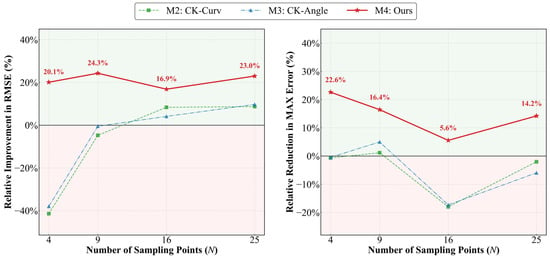

The experimental error distribution maps (Figure 12), error statistics (Table 2), and the error improvement effects of various fusion methods relative to M1 (Figure 13) demonstrate a trend of overall consistency between the experimental results and the simulation findings.

Figure 12.

Experimental error distribution diagrams of different fusion methods.

Table 2.

RMSE and maximum error of different fusion methods.

Figure 13.

Experimental error improvement effects of different fusion methods relative to M1.

(1) In the sparse sampling regime (), M4 achieves an RMSE of 0.01875 , representing a 20.1% error reduction relative to M1 (RMSE = 0.02341 ). Conversely, M2 exhibits an RMSE increase to 0.03311 , a deterioration of approximately 41.4%. These results suggest that the Co-Kriging algorithm struggles to accurately estimate cross-covariance parameters between measurement points and the auxiliary ground truth surface when subjected to high-frequency vibration noise and extremely sparse data.

(2) As the number of sampling points increases to 16 and 25, the Co-Kriging method effectively suppresses machine tool vibration noise, causing its RMSE to rapidly converge towards that of the S-ABS +AHGP method, with the gap narrowing to within 0.003 mm. However, from the perspective of MAX error, residual accumulation persists in the blade edge regions. Even at N = 25, its MAX error remains at 0.21109 mm, which is higher than the −0.17749 mm of the S-ABS+AHGP method.

(3) In comparison to M1, M4 achieves an RMSE of 0.01426 at , outperforming M1 at (0.01696 ). As the sample size increases from 16 to 25, M1 exhibits numerical instability: its MAX error rises from 0.18583 to 0.20688 , accompanied by a slight increase in RMSE. This phenomenon indicates that uniform sampling neglects the non-uniformity of feature distribution, resulting in insufficient capture of local details. Furthermore, the Homoscedastic assumption constrains the model’s local adaptive capability, causing the fusion results to exhibit instability across different sampling scales.

4. Conclusions

To address non-stationary noise caused by varying incidence angles during the fixed-pose laser measurement of aero-engine blades, this paper proposes a multi-sensor fusion method integrating Spatial-Angle-Balanced Sampling (S-ABS) and Adaptive Heteroscedastic Gaussian Process Regression (AHGPR). Through improvements to the Gaussian process regression model, optimization of the touch probe sampling, and comparative analysis, the following main conclusions are drawn:

(1) The proposed AHGPR model integrates an incidence-angle-dependent function within the covariance structure to enable the automatic modulation of observation weights based on local geometry. This approach successfully regulates noise interference caused by large incidence angles, ensuring that optical deviations do not compromise measurement accuracy while strictly capturing the details of the ground truth.

(2) The proposed S-ABS strategy provides a more representative sample distribution for the AHGPR model by balancing the spatial coverage and incident angle diversity of the sampling set. Experimental results demonstrate that this strategy effectively ameliorates the issue of insufficient statistical information encountered with uniform sampling, particularly in regions such as the blade leading/trailing edges and areas with large incident angles.

(3) The AHGP method compresses the inversion dimension of the full-field covariance matrix from the order required by the Co-Kriging method (typically ) to a single order (). This reduction lowers the theoretical computational overhead associated with matrix inversion. Simulation analysis confirms that the framework maintains a certain degree of robustness when subjected to superimposed random environmental interference.

(4) Co-Kriging is robust against strong noise, with accuracy approaching the uniform sampling Homoscedastic model as density increases. In contrast, the proposed AHGPR method shows superior adaptability under sparse sampling. It overcomes local geometric distortion to provide better edge detail capture than Co-Kriging. While slightly inferior in noise robustness, AHGPR holds an advantage in recovering key geometric features.

In summary, the S-ABS+AHGPR framework constructed in this paper provides an improved measurement scheme for multi-sensor integrated measurement of blade surfaces in non-stationary noise environments. The research findings offer new insights into the precision measurement of aero-engine blades and provide valuable engineering references for the design of measurement schemes in on-machine measurement systems.

Author Contributions

Y.Z. spearheaded the conceptualization, study design, original manuscript writing, and experimental execution; X.G. and L.L. oversaw the conceptual development and manuscript refinement; X.L. formulated the research methodology and assisted with experimental work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China, grant number 2023-YBGY-123.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shaanxi Wangao Aerospace Intelligent Manufacturing Technology Co., Ltd. for the professional technical support provided for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Symbol | Definition |

| Measurement residual | |

| Latent residual function to be estimated | |

| Mean function of the Gaussian Process | |

| Covariance function (Kernel function) | |

| -th observation | |

| Global noise variance | |

| Identity matrix | |

| Gram matrix (Kernel matrix) of the training data | |

| Reconstructed incidence angle distribution field | |

| Value range of the incidence angle on the blade surface | |

| Discrete feature target sequence of incidence angles | |

| - | |

| Total number of sampling points | |

| Angle tolerance for constructing candidate sets | |

| -th iteration | |

| -th step | |

| Spatial separation degree | |

| Polynomial basis function for the mean function | |

| Coefficients of the basis function, estimated via MAP | |

| Heteroscedastic noise covariance matrix | |

| Baseline variance component representing environmental noise | |

| Sensitivity coefficient of the sensor to incidence angle variations | |

| Total covariance matrix including Heteroscedastic noise term | |

| Simulated measurement value | |

| True value of the surface height | |

| Inherent linearity error of the sensor |

References

- Bi, Q.; Huang, N.; Zhang, S.; Shuai, C.; Wang, Y. Adaptive machining for curved contour on deformed large skin based on on-machine measurement and isometric mapping. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2019, 136, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Hao, X. A posture adjustment optimization method of the laser inspection device for large complex surface parts. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2018, 232, 2375–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, A.; Lazoglu, I.; Liang, S.Y. Prediction and control of residual stress-based distortions in the machining of aerospace parts: A review. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 76, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, W.; Liu, C. Dynamic machining process planning incorporating in-process workpiece deformation data for large-size aircraft structural parts. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2019, 32, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ma, L.; Wan, M.; Peng, J.; Meng, B. Modeling and simulation of machining distortion of pre-bent aluminum alloy plate. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 258, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Hao, Y.; Qin, S.; Fan, J.; Sun, L. On-machine measurement and compensation of thin-walled surface. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 271, 109308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.; Wan, N.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, G.; Qian, D. A state-of-the-art review on the research and application of on-machine measurement with a touch-trigger probe. Measurement 2024, 224, 113923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Ding, W.; Huang, R.; Fu, Y.; Xu, F. Research progress of laser triangulation on-machine measurement technology for complex surface: A review. Measurement 2023, 216, 113001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.J.; Sun, L.J.; Liu, M.Y.; Cheung, C.F.; Yin, Y.H.; Cao, Y.L. A weighted least square based data fusion method for precision measurement of freeform surfaces. Precis. Eng. 2016, 43, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.J.; Cheung, C.F.; Xiao, G.B. Gaussian process based Bayesian inference system for intelligent surface measurement. Sensors 2018, 18, 4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, D.; Peng, T. Three-dimensional measurement method of four-view stereo vision based on Gaussian process regression. Sensors 2019, 19, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.B.; Ren, J.M.; Xu, M.; Cheung, C.F. Development of data registration and fusion methods for measurement of ultra-precision freeform surfaces. Sensors 2017, 17, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Souzani, M.C.; Yu, L. Implicit residual approximation for multi-sensor data fusion in surface geometry measurement. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 75, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Chen, H.; Chen, C.; Wei, G.; Shi, J.; Tan, J. Research on path planning technology of a line scanning measurement robot based on the CAD model. Actuators 2024, 13, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Feng, P.; Sun, Z.; Cheng, X.; Zeng, L.; Fan, C. Efficient sampling method based on co-kriging for free-form surface measurement. Precis. Eng. 2023, 84, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Ren, M.J.; Sun, L. Dependant Gaussian processes regression for intelligent sampling of freeform and structured surfaces. CIRP Ann. 2017, 66, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Sun, X.; Chen, C.; Sun, M. A fast and on-machine measuring system using the laser displacement sensor for the contour parameters of the drill pipe thread. Sensors 2018, 18, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Xu, M.; Huang, D.; Kong, L. Modeling and compensation of specular reflection errors in laser displacement sensors for complex curved surface measurements. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 192, 113909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, X.; Lei, Z. Research on inclination error between line laser sensor and workpiece surface. Instrum. Tech. Sens. 2023, 7, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Ding, D.; Fu, Y. Error identification and compensation for a laser displacement sensor based on on-machine measurement. Optik 2021, 225, 165902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Fu, Y.; Xu, J. Evaluation and compensation of laser-based on-machine measurement for inclined and curved profiles. Measurement 2020, 151, 107236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Lü, Y.; Wang, K.; Guo, K.; Zhang, Y. Prediction and compensation of point cloud data error in line laser measurement. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2022, 59, 1628006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.E.; Williams, C.K.I. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santner, T.J.; Williams, B.J.; Notz, W.I. The Design and Analysis of Computer Experiments; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudarissanane, S.; Lindenbergh, R.; Menenti, M.; Teunissen, P. Scanning geometry: Influencing factor on the quality of terrestrial laser scanning points. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2011, 66, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersting, K.; Plagemann, C.; Pfaff, P.; Burgard, W. Most likely heteroscedastic Gaussian process regression. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Corvallis, OR, USA, 20–24 June 2007; pp. 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.