Abstract

Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) are widely deployed for long-term monitoring in environments characterized by nonstationary sensing dynamics, intermittent connectivity and continuously evolving network topologies, while reliable, fine-grained labeled data capturing faults and adversarial behaviors remain scarce. This survey systematically reviews and synthesizes recent research that integrates autoencoder-based representation learning with self-supervised learning (SSL) objectives to enhance anomaly detection under these practical constraints. We structure the existing literature through a unified taxonomy encompassing autoencoder variants, self-supervised pretext tasks, spatio-temporal encoding mechanisms and the increasing use of graph-structured autoencoders for topology-aware modeling. Across distinct methodological categories, SSL-augmented frameworks consistently demonstrate improved robustness and stability compared to purely reconstruction-driven baselines, particularly in heterogeneous, dynamic and temporally drifting WSN environments. Nevertheless, this review also highlights several unresolved challenges that hinder real-world adoption, including uncertain scalability to large-scale networks, limited model interpretability, nontrivial energy and memory overheads on resource-constrained sensor nodes and a lack of standardized evaluation protocols and reporting practices. By consolidating publicly available datasets, experimental configurations and comparative performance trends, we derive concrete design requirements for robust and resource-aware anomaly detection in operational WSNs and outline promising future research directions, emphasizing lightweight model architectures, explainable learning mechanisms and federated AE–SSL paradigms to enable adaptive, privacy-preserving monitoring in next-generation IoT sensing systems.

1. Introduction

Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) form a core enabling layer for pervasive monitoring across industrial automation, environmental surveillance, and cyber–physical infrastructures [1]. By distributing lightweight sensing and communication capabilities over large areas, WSNs can capture fine-grained physical and operational signals, yet the same resource-constrained, multi-hop, and often unattended deployment model makes them vulnerable to anomalous observations. Data distortions may arise from sensor aging and calibration drift, intermittent connectivity and packet corruption, abrupt environmental changes or adversarial actions that manipulate traffic and routing behavior. Such deviations propagate to higher-level analytics, degrade energy efficiency through unnecessary retransmissions or control overhead, and ultimately undermine the dependability of the monitoring service. Consequently, anomaly detection is widely treated as a prerequisite for trustworthy information flow in large-scale WSN deployments [2]. In practice, anomalies are typically discussed at three granularities, i.e., the data level (abnormal readings), node level (faulty or compromised devices), and network level (communication or routing disruptions), highlighting the need for methods that remain effective under noise, heterogeneity, and evolving operating conditions. Classical detection strategies, including fixed thresholds, model-based statistical tests, and shallow machine learning classifiers, provide limited robustness when sensor streams are high-dimensional, temporally correlated, and nonstationary. The adoption of deep representation learning, particularly autoencoders (AEs), shifted the field toward learning compact latent structures directly from unlabeled measurements. While reconstruction-driven AEs can be effective when the nominal regime is stable, they often encode site-specific artifacts and may generalize poorly under concept drift, changing workloads or previously unseen faults. Moreover, the operational step of converting reconstruction error into a decision typically depends on carefully tuned thresholds or labeled validation anomalies, both of which are scarce and costly in real WSN settings [3,4,5]. As WSNs grow in scale and diversity, the mismatch between static modeling assumptions and the dynamics of “normal” behavior becomes more pronounced, motivating learning paradigms that can exploit abundant unlabeled data while capturing temporal continuity and inter-node dependencies.

Self-supervised learning (SSL) has gained attention as a principled mechanism for representation learning without manual annotations [6,7,8]. Instead of relying solely on reconstruction, SSL introduces auxiliary pretext objectives for example, contrastive agreement across views, masked signal completion or temporal prediction that encourage the encoder to extract stable, task-relevant factors of variation. Across diverse modalities, SSL has been shown to improve sample efficiency and robustness under distribution shifts by leveraging structure already present in raw data. For WSN anomaly detection, this suggests a path toward representations that remain informative despite noise, partial observability, and evolving patterns. Nevertheless, much of the SSL literature and many SSL-oriented anomaly-detection surveys remain largely domain-agnostic, with limited discussion of WSN-specific constraints such as energy budgets, intermittent links, topology changes or the need to localize anomalies at node and network levels [9]. Furthermore, the integration of SSL objectives with AE families and topology-aware encoders is often presented in isolated lines of work, making it difficult to compare design choices and identify generalizable principles.

Recent work at the intersection of autoencoding, SSL, and graph-based neural modeling provides additional motivation for a consolidated view. Graph neural network autoencoders (GNN–AEs) and related spatio-temporal encoders explicitly encode sensor connectivity, enabling models to capture spatial couplings and routing relationships alongside temporal dynamics [10,11,12]. When paired with SSL objectives, these architectures can learn topology-aware embeddings that frequently surpass reconstruction-only baselines, particularly in heterogeneous multivariate settings [13]. At the same time, the literature reveals persistent practical gaps: scalability is rarely stress-tested beyond moderate network sizes; interpretability is often treated as an afterthought; computational and communication overheads are not consistently reported; and evaluation protocols vary widely, complicating fair comparison and reproducibility [9,14]. Despite rapid methodological growth, a focused synthesis that organizes AE–SSL design patterns for WSNs and evaluates them through a deployment-oriented lens remains limited.

Motivated by these observations, this review adopts a taxonomy-driven survey methodology complemented by a structured narrative meta-synthesis. Rather than presenting a strictly protocolized systematic review, we curate representative studies, cluster them by shared modeling and learning principles, and develop a domain-specific taxonomy that links AE variants, SSL objectives, spatio-temporal encoders, and graph-aware formulations into a unified analytical framework.

Within this scope, the paper provides a consolidated perspective on self-supervised autoencoder-based anomaly detection tailored to WSN constraints. It analyzes how hybrid designs including GNN–AEs, Transformer–AEs, and contrastive or masked-reconstruction AEs improve robustness and label efficiency, and it contrasts architectural trends with respect to accuracy, complexity, and deployment feasibility [15]. The review also synthesizes benchmark datasets, evaluation metrics, and baseline choices, and it identifies open challenges in energy-aware modeling, cross-domain adaptation, and explainable anomaly reasoning that are central to operational WSN monitoring [16,17,18]. By integrating methodological and application-level considerations, the survey aims to support the development of adaptive, self-learning, and trustworthy anomaly detection for next-generation IoT sensing systems.

Contributions

The main contributions of this survey are fivefold. First, it consolidates and systematizes AE–SSL anomaly detection methods for WSNs, including topology-sensitive and deployment-constrained variants. Second, it introduces a four-dimensional taxonomy that organizes prior work by learning objective, architectural design, data context, and evaluation methodology. Third, it conducts a structured meta-synthesis that maps representative anchor studies to the taxonomy and clarifies key trade-offs among detection performance, robustness, and computational complexity. Fourth, it critically reviews datasets, evaluation protocols, and reproducibility practices that shape the empirical evidence base in WSN anomaly detection. Fifth, it outlines an open-problem landscape and a forward-looking research agenda emphasizing lightweight, explainable, and federated AE–SSL frameworks for secure and reliable WSN monitoring.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 summarizes anomaly detection fundamentals in WSNs and revisits existing taxonomic views. Section 3 surveys the evolution from conventional autoencoders to self-supervised and graph-enhanced variants. Section 4 consolidates datasets, evaluation metrics, and baseline practices used for comparative assessment. Section 5 discusses emerging challenges and presents prospective research directions. Together, these sections unify a fragmented body of literature and provide a roadmap for advancing self-supervised anomaly detection in wireless sensor networks.

2. Background

2.1. Overview of Anomaly Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks

Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) serve as a foundational sensing layer for IoT and cyber–physical systems, enabling persistent data acquisition across spatially distributed regions and over extended operational horizons [19]. In practice, the resulting streams are seldom pristine. Measurement quality is routinely degraded by sensor aging and calibration drift; lossy wireless links that introduce corruption or loss; irregular sampling induced by duty cycling; and exogenous environmental interference. Since control, forecasting and safety decisions are increasingly coupled to these observations, timely detection of abnormal behavior is central to both service reliability and energy-efficient operation [20,21,22]. Recent assessments further note that the decentralized, resource-constrained nature of WSNs deployments exposes failure modes and attack surfaces that differ from those commonly assumed in more provisioned IoT platforms. As networks scale in node count and heterogeneity and as topology and operating regimes evolve more rapidly, static thresholds and purely centralized monitoring tend to become brittle. These limitations have accelerated interest in autonomous, context-aware detection mechanisms that can operate under distributed constraints, adapt to shifting baselines and enable timely mitigation in situ [23].

2.2. Types of Anomalies in Sensor Networks

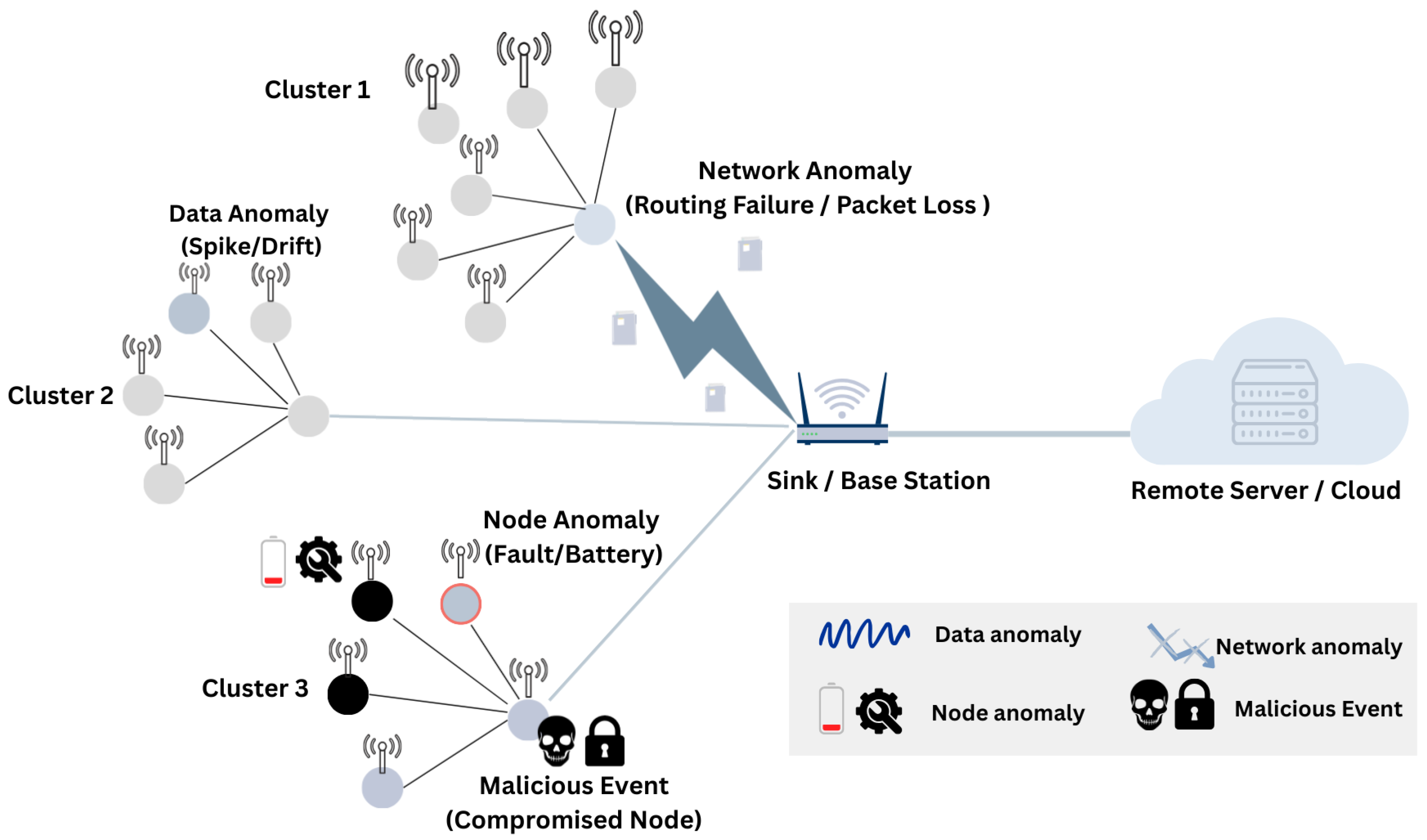

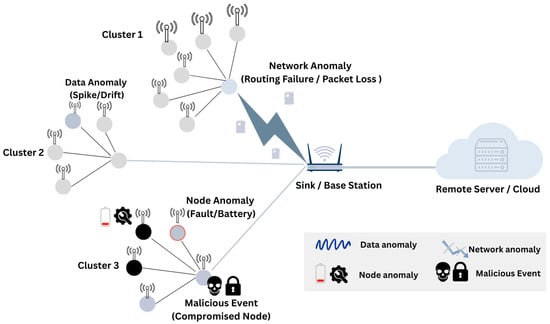

Anomalies in WSNs can be characterized by their manifestation point and their spatio-temporal evolution. Figure 1 provides a practitioner-oriented view that distinguishes (i) data-level anomalies, where individual measurements or short temporal windows deviate from expected ranges due to noise, interference or transient disturbances; (ii) node-level anomalies, reflecting sensor faults, miscalibration, power depletion or compromise that systematically alters a device’s overall behavior [24,25]; (iii) network-level anomalies, associated with communication and routing disruptions such as congestion, link instability or protocol misuse; and (iv) adversary-driven anomalies, where malicious actions intentionally induce or mask abnormal patterns. In addition to location, anomalies may appear as isolated point events, sustained contextual deviations conditioned on operating conditions or collective patterns that become apparent only when considering correlations across multiple nodes or time steps. This multi-granular structure motivates detection strategies that go beyond univariate outlier screening and instead exploit temporal continuity and inter-node dependencies to distinguish benign irregularities from faults and malicious activity. The implications of these anomaly categories for evaluation design, reporting granularity, and metric selection are discussed in Section 6.3.

Figure 1.

Conceptual view of a Wireless Sensor Network showing typical anomaly locations at the data, node, network and adversarial levels.

2.3. Traditional Approaches and Their Limitations

To improve flexibility, researchers introduced classical machine-learning models that learn decision boundaries from data [26,27]. Approaches based on k-nearest neighbors, support vector machines and tree-based predictors can capture nonlinear relationships beyond simple rules, yet their effectiveness hinges on two especially brittle requirements in WSNs settings: access to representative labeled anomalies and the availability of informative, manually engineered features [28]. Label scarcity is a recurring operational constraint, as many faults and attacks are rare, evolving or only partially observed; feature engineering, in turn, is difficult to scale and sustain as sensor modalities and network protocols diversify. Even when online or ensemble variants are applied to streaming data, these models often require periodic re-estimation to track drift [29] and can impose notable communication costs if training and aggregation are performed centrally [30].

2.4. Autoencoders for WSNs Anomaly Detection

Autoencoders (AEs) are widely used for unsupervised anomaly detection because they learn a compact representation of nominal behavior and score deviations via reconstruction error [3,31]. An AE typically encodes an input into a low-dimensional latent space and decodes it back to the original domain, thereby capturing salient regularities in unlabeled sensor streams. Robustness is often improved through denoising, sparse and variational formulations, which introduce explicit regularization and noise-tolerance mechanisms during training. These properties align well with WSNs conditions, where anomaly labels are limited and measurements can be noisy, heterogeneous and high-dimensional [32]. However, conventional AE pipelines frequently treat node observations independently, despite strong spatial and functional coupling across the network. Graph-based autoencoders mitigate this gap by incorporating message passing or graph convolution operators so that embeddings reflect inter-node dependencies [33]. Recent spatio-temporal designs further combine graph encoders with recurrent modules or transformers to better capture drift, distribution shifts and topology variability [34,35,36]. Recent studies beyond the WSN literature underscore a broader architectural trend toward hybrid autoencoder backbones that combine inductive biases from convolutional, recurrent, variational, and graph-based modeling. In transient stability assessment, for example, convolutional autoencoders have been paired with imbalance-aware optimization (including focal-loss-style objectives) to preserve sensitivity to rare but critical events [37]. Related work on oscillation source localization has explored LSTM-based variational sequence encoders, augmented with graph convolution to exploit structured correlations among measurement points [38]. In industrial monitoring, multi-scale dual-decoder autoencoders have been introduced to maintain detection fidelity under domain shift by reconstructing complementary signal views at different resolutions [39]. Collectively, these results suggest that the most transferable AE designs increasingly rely on composite backbones and data, regime-matched objectives, offering useful design cues for AE-SSL development in WSN settings.

2.5. Self-Supervised Learning in Resource-Constrained WSNs

Self-supervised learning provides a complementary strategy for extracting informative representations when labeled data are limited [40]. Instead of relying on external annotations, SSL constructs surrogate learning tasks, such as predicting masked segments, aligning augmented views or forecasting future states to guide representation learning [41]. These tasks encourage the model to discover invariances within the data and yield embeddings that transfer effectively to downstream anomaly-detection objectives. SSL has demonstrated notable gains across time-series, vision and network-traffic domains and its ability to operate without labels aligns naturally with the constraints of WSNs [42,43]. However, applying SSL to multivariate sensor data requires thoughtful adaptation: augmentations must reflect realistic transformations, temporal continuity must be preserved and relationships across nodes must remain intact [44,45]. Recent studies address these challenges through graph-contrastive learning, temporal prediction tasks and clustering-based SSL variants designed explicitly for sensor networks. Such approaches enhance robustness to noise, strengthen representation stability and reduce the calibration burden on resource-limited nodes.

2.6. Design Guide: Selecting AE Variants and SSL Objectives Under WSN Constraints

The guidance below is offered as an implementation aid rather than a new method. While the taxonomy in Section 4 structures the literature, deployment decisions in WSN practice still require a clear mapping from constraints to modeling choices for AE–SSL pipelines. A pragmatic workflow is to first choose the AE backbone (Section 2.4) according to the dominant structure and expected failure modes of the deployment—for example, primarily temporal regularity, strong inter-node coupling or time-varying topology—and then choose the SSL objective (Section 2.5) to impose the invariances the monitor must maintain in the field (e.g., tolerance to noise, missing data, drift, and node dropout). Under this view, SSL strengthens robustness mainly by stabilizing the representation rather than by adding capacity: predictive, contrastive or self-labeling signals promote (i) embedding stability under realistic perturbations, (ii) invariance to benign variability and gradual drift that would otherwise destabilize reconstruction-based thresholds, and (iii) reduced reliance on reconstruction-specific artifacts by preventing the encoder–decoder from optimizing reconstruction fidelity alone. Table 1 summarizes this constraint-to-choice mapping in a form that is consistent with the learning-objective and architecture axes formalized in Section 4. Moving beyond deterministic formulations, variational autoencoders (VAEs) model the latent space probabilistically, enabling uncertainty-aware anomaly scoring via reconstruction likelihood, ELBO-based criteria, and related variance signals that can improve calibration under drifting nominal regimes. This advantage comes with added complexity: KL regularization and stochastic sampling alter optimization dynamics, and uncertainty estimates are typically more stable when aggregated over multiple samples, increasing training cost and potentially adding deployment latency if repeated sampling is used at inference. In AE-SSL pipelines, masked-recovery and predictive pretexts align naturally with denoising and temporal AEs (and often VAEs) because they explicitly enforce robustness to missingness, corruption, and short-horizon dynamics that arise from sensing noise and unreliable links in WSNs. Contrastive objectives, in turn, tend to benefit most from temporal or graph encoders when augmentations preserve physical plausibility for instance, mild jitter, duty-cycle-consistent dropout or subgraph sampling that respects connectivity so that positive pairs remain consistent with the underlying process. A recurrent tension is that VAE-induced stochasticity can degrade contrastive alignment by injecting representation noise, unless the contrastive branch uses the mean embedding (or low-variance sampling) and the relative loss weights are carefully tuned. A second failure mode occurs when augmentations violate sensor physics or network constraints (e.g., unrealistic time warping or topology perturbations), undermining predictive consistency and inflating false positives under benign variability. For these reasons, multi-term training (reconstruction + SSL, with optional KL) should be treated as an explicit design decision: loss weights should be reported, and at minimum, narrative ablations or sensitivity checks should justify that robustness gains are not artifacts of a particular weighting. These practical pairing notes complement Table 1 by clarifying when uncertainty modeling and objective selection are synergistic, and when stabilization is required for reliable training and deployable inference.

Table 1.

Practitioner-oriented design guide mapping common WSN deployment constraints to autoencoder backbones (Section 2.4) and SSL objective families (Section 2.5), together with the underlying robustness motivation. The resulting choices are later organized and synthesized through the taxonomy axes in Section 4.

2.7. Integrating Autoencoders and SSL: Emerging Paradigms

Recent studies increasingly position the combination of autoencoders and self-supervised learning (SSL) as a practical route to more resilient WSN anomaly detection under scarce annotation [46,47,48]. In most hybrid formulations, the AE remains the reconstruction backbone, while the encoder is trained with additional self-supervised signals (e.g., contrastive agreement, temporal prediction or masked recovery) so that representation learning is not governed solely by reconstruction fidelity [46]. Optimizing reconstruction together with auxiliary discriminative or predictive objectives typically yields latent spaces that capture both recurring structure and operational context, improving robustness when nodes drop out or sensing conditions drift. Graph-aware instantiations further inject topology and temporal continuity through message passing and attention-style aggregation to model inter-node dependencies. Across recent benchmarks, SSL-augmented AEs often surpass reconstruction-only baselines, especially in label-limited and intermittently observed regimes [49]. The benefits also include stronger cross-deployment transfer and reduced retraining requirements, although open questions remain around pretext-task selection for heterogeneous modalities, loss balancing and stable training under decentralized constraints [50].

2.8. Summary and Transition to Taxonomy

Overall, the field’s evolution from rule-based thresholds to deep representation learning reflects the need for detectors that can internalize the spatio-temporal structure of WSNs signals rather than relying on static assumptions. Autoencoders provide a practical unsupervised backbone for modeling nominal behavior, while self-supervised objectives mitigate the brittleness of reconstruction-only training and strengthen generalization when labels are limited or unavailable [3]. The recent fusion of AE and SSL, increasingly realized through graph-structured formulations, signals a shift toward anomaly-detection pipelines that are better aligned with distributed sensing realities and more robust to drift and partial observability. In such settings, conventional supervised intrusion-detection solutions remain difficult to sustain, as they depend on extensive labeled data and implicitly assume stationary data-generating processes [51,52]. AE–SSL approaches offer an alternative by using pretext tasks to learn transferable, topology-aware representations from unlabeled streams, improving fault tolerance and maintaining performance under real-world uncertainty [53]. Guided by these foundations, the next section introduces a taxonomy that structures the literature by architectural design, learning paradigm and deployment context to provide a coherent view of current research trajectories.

3. Methods

3.1. Methodological Scope and Review Framework

This review was structured to enable systematic comparison across a broad spectrum of approaches, from conventional autoencoder-based detectors to emerging self-supervised and graph-centric formulations, within a single analytic lens. Rather than enumerating architectures in isolation, we employ a meta-synthesis that emphasizes how methods are motivated, instantiated and assessed under the practical realities of distributed sensing [54]. The focus is on the methodological rationale that shapes each pipeline: the design decisions used to operationalize anomaly scoring, the mechanisms by which models exploit spatio-temporal WSNs structure and the extent to which evaluation choices illuminate or inadvertently mask generalization under drift and partial observability [54,55].

3.2. Data Handling and Study Selection Logic

This article follows a taxonomy-driven structured literature review approach rather than a fully protocolized systematic review. The objective is to extract and compare methodological design patterns in AE–SSL anomaly detection for WSNs, emphasizing reproducible engineering details over exhaustive study enumeration.

We conducted an iterative literature retrieval using major scholarly indexes (e.g., IEEE Xplore, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) and backward/forward citation chasing from seed papers in AE-based WSN anomaly detection and SSL representation learning. Search strings combined terms from three facets: (i) domain (“wireless sensor network”, “WSN”, “IoT sensing”), (ii) task (“anomaly detection”, “intrusion detection”), and (iii) method (“autoencoder”, “self-supervised”, “contrastive”, “masked”, “predictive”). Candidate papers were screened in successive passes (title/abstract, then full text) to confirm domain and methodological relevance.

Inclusion focused on studies that (a) addressed anomaly detection in WSNs or WSN-like sensing deployments, and (b) proposed or evaluated autoencoder-based modeling and/or explicit self-supervised objectives, with sufficient procedural detail to enable methodological comparison (objective definition, preprocessing, training workflow, and evaluation protocol). We excluded works that were (i) generic non-WSN intrusion detection without sensing/deployment context, (ii) missing an AE/SSL methodological component relevant to this review or (iii) insufficiently specified (e.g., absent objective definition, training details or evaluation configuration).

For each retained study, we extracted a standardized set of descriptors: task granularity (node/window/network), objective type (reconstruction, contrastive, predictive/masked), architecture family (AE variants and any graph/temporal modules), data and preprocessing assumptions, and evaluation design (metrics, splits, robustness tests, and reproducibility cues). These descriptors were then used to build the multi-axis taxonomy and to structure the comparative synthesis across clusters.

3.3. Conceptual Clustering of Methods

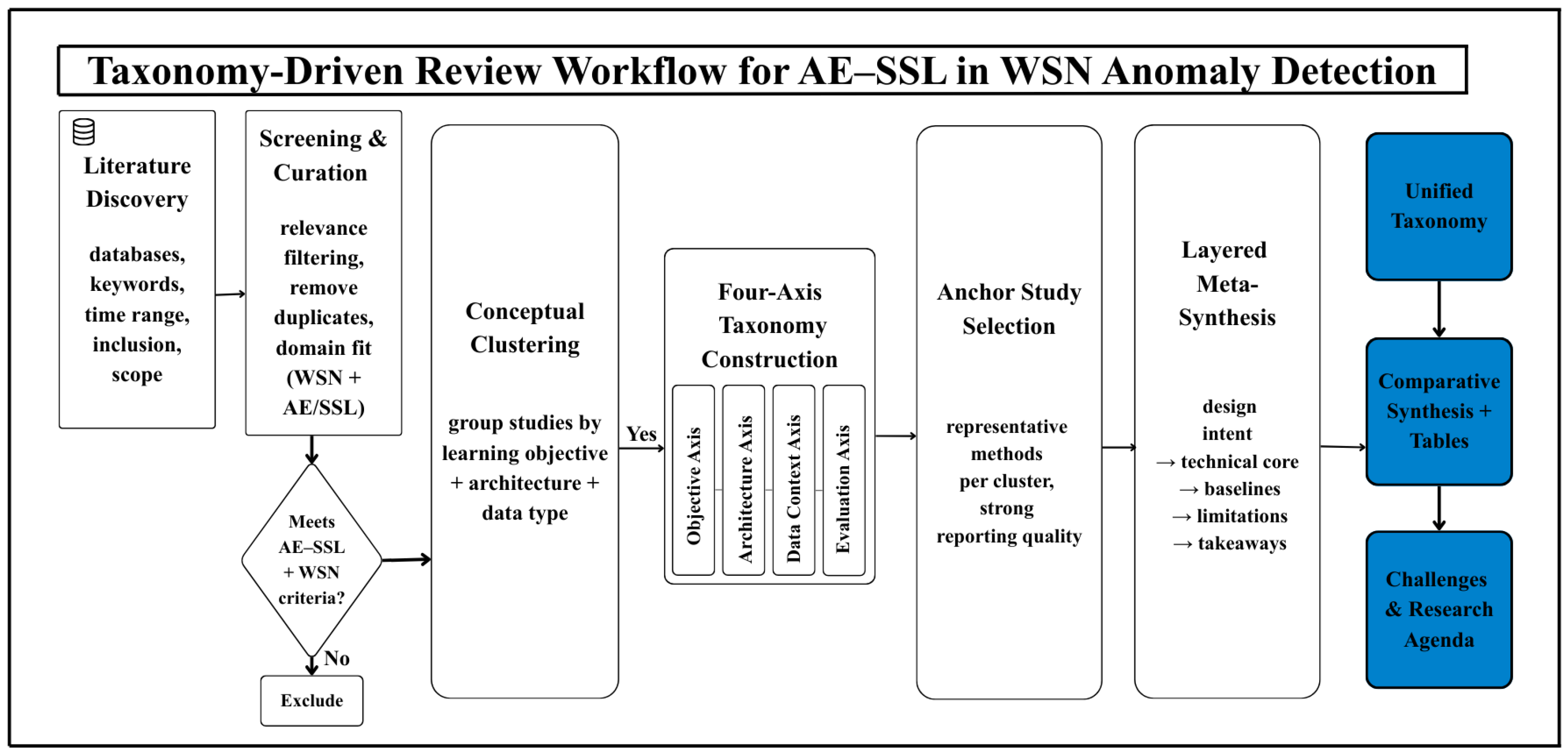

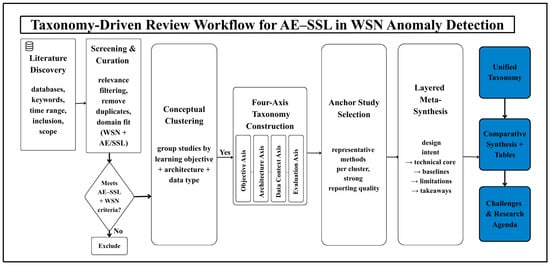

The end-to-end review workflow used for literature curation, clustering, and taxonomy construction is depicted in Figure 2. To organize the comparative synthesis, we group the literature into four conceptual clusters that reflect recurring design patterns and evaluation emphases. C1 comprises autoencoder-centric anomaly detectors in which reconstruction-based learning is the primary mechanism for unsupervised detection. These studies typically use reconstruction error as the anomaly score and extend the baseline AE through temporal modules, sparsity/denoising constraints or topology-aware encoders to better capture coupling and heterogeneity in WSN telemetry. C2 captures hybrid designs that combine autoencoding with explicit self-supervised learning objectives. Here, auxiliary tasks such as masked recovery, temporal prediction or contrastive consistency regularize representation learning, producing latent spaces that are less dependent on reconstruction alone and more robust under limited anomaly labels or weak supervision. C3 focuses on topology-aware AE–SSL formulations, where graph-structured encoders and contrastive/predictive objectives are jointly used to model spatio-temporal dependencies and scalability trade-offs in WSN-like graphs. C4 summarizes survey and review contributions that consolidate evaluation practices and deployment considerations (e.g., federated settings, non-IID effects, communication/privacy constraints, and protocol transparency) [56]. This cluster is included to contextualize how empirical results should be interpreted under real-world WSN constraints rather than to introduce a new detector. Table 2 summarizes representative exemplars by cluster, backbone configuration, and each study’s central empirical takeaway, with selections guided by the selection rubric in Section 3.4.

Figure 2.

Taxonomy-driven review and meta-synthesis workflow adopted in this paper to systematically analyze AE- and self-supervised-learning-based anomaly detection methods for WSNs.

Table 2.

Representative exemplars anchoring the cluster-wise AE–SSL synthesis for WSN anomaly detection (methods and survey context).

3.4. Anchor Paper Identification Process

Anchor studies were chosen to represent each methodological cluster in a way that supports a transparent and auditable synthesis. They were not selected on the basis of citation counts, venue prestige or headline accuracy. Instead, anchors serve as high-resolution exemplars from which methodological choices can be extracted consistently, including objective formulation, architectural design, data handling, and evaluation protocol to enable the layered analysis in Section 3.5.

To limit subjectivity, anchor selection followed a predefined, rule-based rubric applied within each cluster after screening (Section 3.2 and Section 3.3) and conceptual clustering (Section 3.3). All included studies inform the taxonomy and comparative narrative; the anchor label only determines which papers receive deeper, exemplar-level analysis, not which evidence is considered.

Representative/Anchor Selection Rubric (applied per cluster). Each eligible study was scored using a three-level scale (0 = not reported/not met, 1 = partially met, 2 = clearly met). Anchors were drawn from the highest-scoring candidates in each cluster; when scores tied, we selected the set that maximized complementarity across the taxonomy axes (architecture, SSL objective family, data context, and evaluation emphasis) to avoid over-representing a single design pattern.

- Direct relevance to AE-SSL anomaly detection in WSN/IoT sensing contexts: the work targets anomaly detection on WSN/IoT telemetry and uses an AE and/or an explicit SSL objective as a core methodological component.

- Methodological distinctiveness within the cluster: the study reflects a clearly differentiable design aligned with the taxonomy (e.g., AE backbone/variant, temporal or topology module, SSL objective family or scoring pipeline), rather than a minor variant without clear conceptual separation.

- Reporting adequacy for reproducible interpretation: the paper discloses sufficient detail on data preparation (e.g., preprocessing and windowing), model specification, training workflow, and evaluation protocol to support consistent comparison.

- Evaluation rigor and attribution of gains: the study includes controlled comparisons (baselines and/or ablations) and a well-defined scoring and decision procedure (e.g., reconstruction-error scoring and thresholding/calibration), enabling attribution of gains to specific components.

- Coverage contribution across taxonomy axes (set-level complementarity): when candidates are comparable, preference is given to those that improve coverage of underrepresented objective families, architectures, data regimes or evaluation settings within the cluster.

3.5. Layered Meta-Synthesis Strategy

Each anchor study was examined using a layered analytic scheme designed to recover the methodological intent underlying its design choices. The first layer characterized the authors’ operational definition of anomaly, distinguishing whether abnormality was expressed through reconstruction deviation, instability in latent representations, temporal incoherence or disruptions tied to graph structure. The second layer interrogated the technical core of the method, including encoder–decoder composition, temporal modeling components, graph operators and neighborhood aggregation, augmentation policies and the construction and weighting of hybrid loss functions. A third layer captured the comparative positioning of the contribution by documenting the baselines, prior methods and evaluation framing used to substantiate claimed advances. A final layer distilled a concise takeaway that links the study’s contribution to broader methodological trajectories. This multi-layer reading supports a more faithful synthesis of how AE-centric, SSL-augmented and spatio-temporal graph models formalize and detect anomalies from distinct, yet partially convergent, perspectives.

3.6. Integrative Methodological Insight and Transition

Viewed collectively, these clusters indicate a steady movement away from purely reconstruction-driven reasoning toward representation learning informed by structural priors and complementary training signals. Reconstruction-based autoencoder pipelines continue to provide a useful baseline, yet their sensitivity to distribution drift and their limited ability to encode inter-node dependencies have accelerated interest in SSL-augmented and graph-aware formulations. At the same time, benchmarking and comparative contributions repeatedly highlight a practical gap between methodological novelty and reproducibility: seemingly incidental choices such as the ordering of preprocessing steps, window construction or sampling alignment often govern whether reported gains can be reproduced. A broader tension thus persists across the literature: increasing model expressiveness and training complexity must be reconciled with deployment realities, including energy constraints, bandwidth limitations and heterogeneous sensing schedules. These observations motivate the taxonomy developed in the next section, which formalizes the architectural patterns and learning paradigms identified above into a structured classification of recent AE–SSL approaches for WSNs anomaly detection.

4. Taxonomy of Self-Supervised Autoencoder Methods for Wireless Sensor Networks

4.1. Purpose and Scope of the Taxonomy

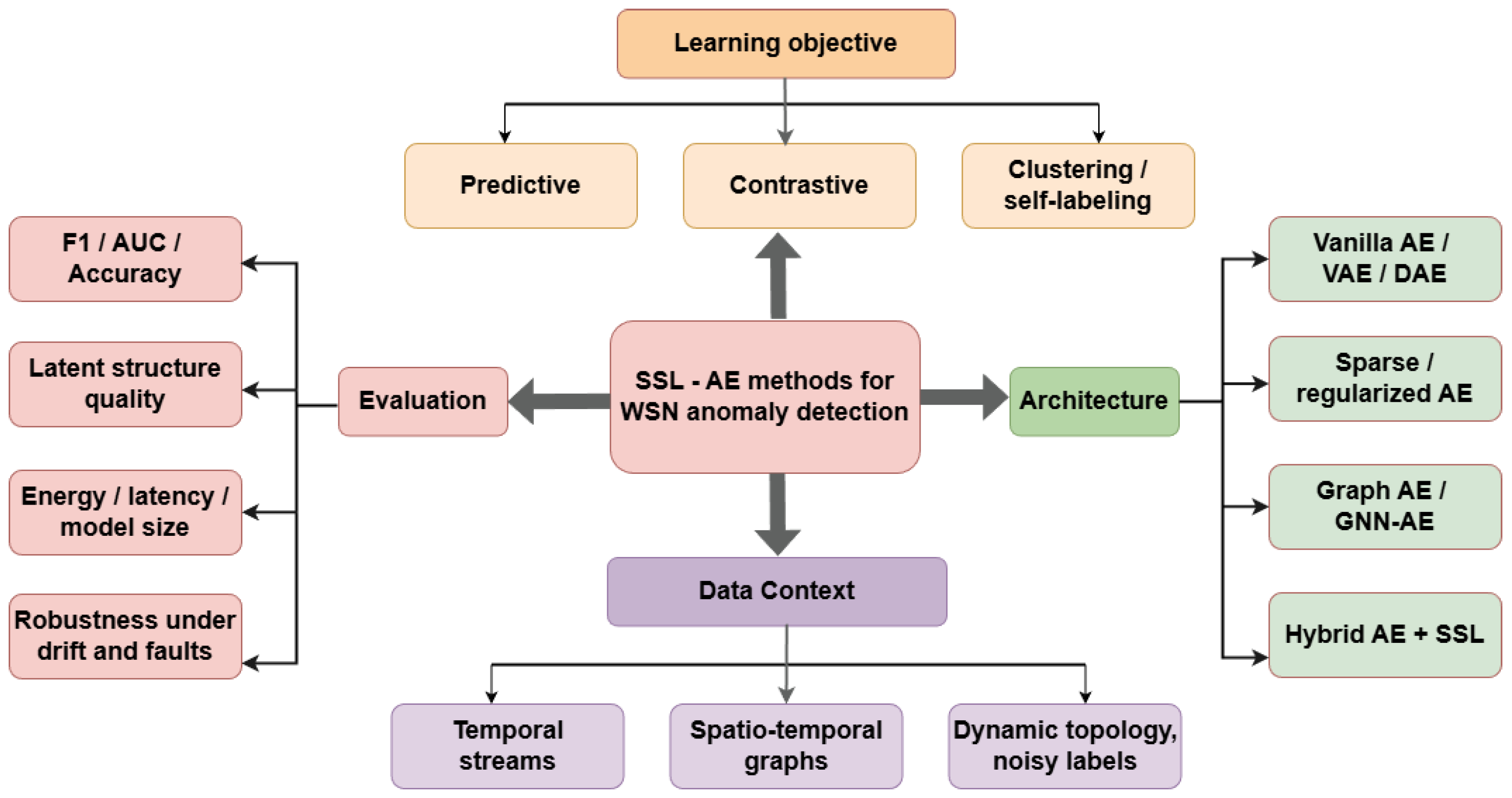

Differences extend beyond network architecture to training objectives, data representations, and the assumptions embedded in experimental validation under realistic WSNs constraints. A principled taxonomy is therefore required to impose structure on this diversity, exposing the design logic that connects modeling choices to deployment needs. The taxonomy developed in this review categorizes prior work along four orthogonal dimensions: (i) the learning objective that shapes representation formation, (ii) the architectural backbone used to encode WSNs signals, (iii) the data context and characteristics being modeled and (iv) the evaluation methodology used to substantiate performance claims. This multi-axis organization supports consistent comparison across studies and clarifies the methodological trends that currently define the AE–SSL research landscape for WSNs anomaly detection.

4.2. Learning-Objective Axis

Self-supervised anomaly detection in WSNs is grounded in the premise that supervisory signals can be constructed from the data-generating process itself, allowing representations to be learned without explicit anomaly labels. Across the literature, learning objectives tend to fall into three recurring families. The first comprises predictive objectives, where models are trained to reconstruct masked segments, predict future windows or otherwise recover withheld temporal content [63]. Because WSNs telemetry often exhibits strong temporal continuity, these objectives encourage encoders to capture regular rhythms; faults, drift or abrupt disruptions then manifest as increased prediction error or reconstruction residuals [64]. A second family is contrastive learning, which shapes embeddings by pulling together representations of related sensor states while separating those deemed unrelated [65]. In WSNs settings, positive and negative pairs are typically defined through time adjacency, spatial neighborhood relations or cross-sensor correlation structure rather than through aggressive augmentation schemes common in vision [66]. The third family uses clustering or self-labeling mechanisms that induce latent prototypes and treat cluster assignments as implicit supervision, thereby organizing the representation space even when task labels are entirely absent.

4.3. Architectural Axis

Model architecture strongly determines which aspects of WSNs behavior can be represented and, consequently, which anomaly signatures can be expressed. Conventional AE families, including basic encoder–decoder designs, as well as denoising, sparse and variational variants, remain widely used because they are comparatively lightweight and typically train reliably on unlabeled streams [67]. However, when anomalies arise from coordinated effects across nodes or from dynamics that couple topology with time, purely feature-wise encoders can be insufficient, as they do not explicitly encode inter-node relationships or structured temporal dependence [68]. This limitation has motivated graph-based autoencoders that incorporate message passing or graph convolution operators so that latent representations are informed by neighborhood context and network connectivity. Recent advances in graph anomaly detection extend beyond pairwise neighborhoods by using hypergraph transformations to represent higher-order correlation structure. This line of work suggests a complementary avenue for WSN/IoT telemetry, where group-level dependencies among sensors, links or routing components may encode anomaly signatures that conventional edge-based graphs fail to capture [69]. Contemporary systems frequently adopt spatio-temporal backbones that pair graph modules with sequence encoders, such as GRUs, LSTMs or attention mechanisms, to model both temporal evolution and topology-conditioned interactions, yielding more faithful representations of distributed sensing processes [70]. Parallel hybrid architectures in adjacent domains similarly fuse convolutional feature extractors with recurrent and/or variational latent modeling and graph convolution, leveraging structured dependencies to improve robustness under class imbalance and domain shift [37,38,39]. A further architectural trend integrates self-supervised objectives directly into the AE backbone. In these hybrids, reconstruction provides a stable generative pathway, while SSL regularizes and structures the latent space to improve robustness, discriminability and transfer across deployments [71].

4.4. Data-Context Axis

The data regime of a WSNs and its operating context often dictates which modeling choices are appropriate and which objectives are most informative. In some deployments, observations are dominated by temporal dynamics and anomalies manifest as isolated spikes, slow drifts or short-lived deviations within individual node streams [72]. In such cases, predictive or reconstruction-oriented autoencoders can be effective because fixed-length windows provide a natural unit for learning recurring temporal structure [73]. Many real networks, however, exhibit pronounced spatial coupling: environmental effects diffuse across regions, failures can propagate across adjacent nodes and communication artifacts introduce correlated distortions across links and routes. To reflect these conditions, recent AE–SSL methods increasingly operate on spatio-temporal graphs, pairing per-node sequence modeling with topology-aware aggregation or relational inference [74]. This joint view supports more nuanced localization by distinguishing irregularities that track neighborhood trends from those that remain isolated and therefore more indicative of local faults or compromise [75].

4.5. Evaluation and Performance Axis

Evaluating SSL-augmented autoencoders requires evaluation criteria that extend beyond conventional detection scores. Measures such as F1-score, AUC and accuracy remain central for quantifying classification and ranking quality, yet they do not fully reflect operational suitability or decision stability in resource-limited WSNs deployments [76]. As a result, many studies additionally report indicators of representation quality, including embedding separability, cluster compactness and linear-probe performance, to assess whether self-supervised objectives produce a structured latent space rather than merely improving reconstruction [77,78]. System-level constraints are equally consequential: memory footprint, inference latency, communication overhead and node-side energy cost can determine whether a method is deployable even when detection performance is strong. Robustness is also increasingly treated as a first-class requirement, with evaluations probing behavior under node dropout, distribution drift and irregular sampling, acknowledging that resilience to field conditions can be as important as peak metrics. Collectively, these practices reflect a shift toward assessments that link algorithmic gains to deployment viability in real WSNs settings.

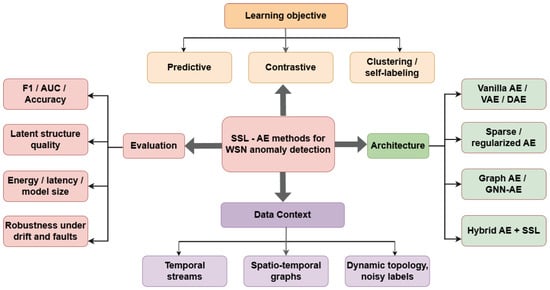

4.6. Cross-Axis Synthesis and Integrative Insight

Considering the four axes jointly highlights that performance is rarely attributable to a single design choice. Figure 3 visualizes the proposed four-axis taxonomy, connecting objectives, architectures, data contexts, and evaluation dimensions. The learning objective specifies which invariances and predictive relations the model is encouraged to preserve; the architecture determines how those constraints are instantiated through temporal encoding and where applicable, topology-aware aggregation; and the data regime shapes the validity of both assumptions and implementations. Evaluation, in turn, determines whether these choices translate into detectors that remain reliable under realistic WSNs irregularities.

Figure 3.

Taxonomy of self-supervised autoencoder-based methods for WSN anomaly detection organized along learning objectives, architectural choices, data context, and evaluation criteria.

Example (GLSL method [57]). Using the four-axis taxonomy in Figure 3, GLSL can be situated as follows. Learning objective: the method first pretrains a reconstruction-based autoencoder to model nominal behavior then introduces a self-supervised classification stage (self-labeling) to further structure the latent space beyond reconstruction alone. Architecture: GLSL adopts a spatio-temporal GNN-AE, combining a graph autoencoder backbone with a GRU-based temporal encoder to capture inter-node dependence and short-range temporal dynamics. Data context: it is designed for multi-node WSN/IoT routing and traffic telemetry where relational structure is informative; in this review it is evaluated on WSN-DS and IoT-23 (Table 2). Evaluation protocol: the study is interpreted according to its reported benchmark protocol and detection metrics (e.g., F1/AUC/accuracy as applicable) while any additional system indicators (e.g., latency, memory, energy proxies) are treated as deployment evidence rather than taxonomy-defining attributes. The same mapping can be applied to other works by explicitly identifying (i) the SSL objective family (pretext loss) (ii) the AE backbone and any temporal or topology modules (iii) the assumed sensing and topology regim and (iv) the evaluation protocol and reported metrics.

5. Comparative Methodological Synthesis

5.1. Purpose of the Comparative Synthesis

Building on the taxonomy, a comparative synthesis is necessary to translate abstract categories into concrete insight about how design decisions affect empirical behavior. The surveyed literature differs not only in backbone architecture, but also in the objectives used to shape representations, the treatment of spatio-temporal telemetry, dataset selection and preprocessing conventions and the transparency with which performance and resource costs are reported [79]. Accordingly, this section contrasts representative methods across these dimensions, emphasizing the implications of reconstruction-dominated versus self-supervised training, architectural capacity and depth, explicit topology modeling, robustness to noise and drift and computational and communication overhead.

5.2. Comparative Analysis by Methodological Cluster

5.2.1. Hybrid AE + SSL Frameworks

Methods in the second cluster augment reconstruction with self-supervised objectives, treating the autoencoder as a base learner whose encoder is shaped by additional training signals. In these formulations, anomaly detection is no longer driven solely by the ability to reproduce inputs; the model is simultaneously encouraged to solve auxiliary tasks such as forecasting, masked-value completion or contrastive separation of related versus unrelated sensor segments. The gains, however, are less automatic than the headline results can suggest. Outcomes are highly contingent on pretext-task selection, augmentation policy and the construction of positive–negative pairs, which together determine the stability and discriminability of the learned latent space. A recurring concern is that many studies report substantial improvements while providing insufficient detail on pretraining schedules, transformation details or sampling logic, which complicates replication and weakens cross-paper comparability. Overall, the literature indicates that AE–SSL hybrids tend to generalize more reliably than pure AEs, but this benefit comes with added methodological complexity and a greater requirement for transparent reporting [80].

5.2.2. Benchmark and Evaluation-Focused Studies

The final cluster shifts attention from proposing new detectors to interrogating how existing methods are validated and compared. These benchmarking and survey-oriented contributions repeatedly identify structural weaknesses in current evaluation practice, including over-reliance on a small set of legacy datasets, non-uniform train–test partitioning and incomplete disclosure of preprocessing pipelines and hyperparameter settings [81]. A consistent implication is that reported improvements across papers are often not directly comparable, since differences in data preparation and protocol choices can dominate observed performance. To address this, several studies advocate taxonomy-aligned evaluation procedures, broader multi-metric reporting that combines detection quality (e.g., F1 and AUC) with operational indicators (e.g., latency, memory and energy) and explicit guidance for non-IID data and federated or distributed learning scenarios.

5.3. Anchor Study Comparisons

Within the AE-centric stream, representative anchors illustrate two complementary design logics. One line couples topology-aware encoding with temporal modeling by integrating a graph autoencoder with a GRU-based sequence module, showing that jointly capturing inter-node dependence and local temporal continuity can deliver a clear advantage over reconstruction-only AEs. A second line adopts a modular pipeline in which a transformer-based autoencoder is used purely for representation learning, while anomaly decisions are delegated to downstream detectors such as Isolation Forest models or gradient-boosted trees; this separation can simplify thresholding and, in some cases, improve interpretability through more transparent decision rules [82]. Beyond headline performance, these anchors are notable for relatively complete architectural and training documentation, making them useful reference points for reproducible system design.

Anchors in the hybrid AE–SSL cluster emphasize the effect of objective design and protocol rigor. A prominent time-series-oriented study benchmarks contrastive and predictive pretext tasks on AE backbones across multiple sensor datasets, reporting consistent gains (typically several percentage points) over reconstruction-only baselines and demonstrating that windowing, augmentation and scoring conventions can materially affect outcomes [83]. Complementing this, another anchor introduces semantic-aware masking designed for industrial sensor telemetry and supports its claims with extensive ablation experiments, illustrating how domain-aligned pretexts and rigorous controls can make self-supervised behavior more stable and interpretable. For topology-aware methods, a representative graph-focused work combines graph-contrastive learning with predictive losses on simulated WSNs configurations and reports strong detection performance alongside reported energy reductions achieved through cluster-level graph handling [84]. Finally, anchors in the benchmarking-oriented cluster contribute less through new modeling components than through evaluation infrastructure, offering reproducible blueprints that specify dataset curation, aggregation and windowing settings and where relevant, privacy and communication assumptions, rather than relying on incompletely standardized headline metrics.

5.4. Cross-Cluster Synthesis

Across the surveyed clusters, a consistent set of trade-offs becomes apparent. Reconstruction-oriented AEs remain strong baselines, yet their performance can deteriorate under concept drift and increasing network heterogeneity, where nominal behavior is neither fixed nor uniformly observed. AE–SSL hybrids tend to strengthen robustness and reduce reliance on labeled anomalies, but they also amplify sensitivity to objective design, augmentation policy and training protocol, increasing the practical cost of insufficient methodological disclosure [85]. Graph-aware models are often best positioned to detect anomalies that are inherently relational or propagative, although their advantages are accompanied by higher computational and memory overhead that can complicate deployment on constrained nodes. Benchmark-focused studies further underscore that evaluation design, including preprocessing choices, windowing and split strategy, can materially influence results and, in some cases, eclipse architectural differences. Overall, the literature suggests that credible progress depends on jointly balancing detection performance, model and system complexity and deployability, with the most promising advances emerging when structure-aware modeling is paired with transparent, rigorously specified evaluation protocols [86].

5.5. Consolidated Comparative Takeaways

The comparative synthesis indicates that the literature does not converge on a single best paradigm; instead, each cluster occupies a distinct region of the design space with different operational assumptions. Reconstruction-based autoencoders remain a strong reference point and can be well suited to stable regimes or highly constrained deployments where simplicity and predictable training behavior are paramount [87]. AE–SSL hybrids generally offer improved robustness and label efficiency, particularly when pretext tasks are chosen to reflect sensing physics, temporal continuity and network structure rather than being transplanted wholesale from other domains [88,89,90]. Topology-aware models are most compelling when abnormality is fundamentally relational and existing evidence suggests that combining graph structure with self-supervised objectives is a particularly promising path for strengthening generalization and localization [91,92]. Benchmarking and evaluation-focused work, although less visible than model proposals, is critical for ensuring that reported improvements are reproducible and that progress is trustworthy rather than artifact-driven.

6. Datasets, Metrics, and Evaluation Protocols

6.1. Overview of the Evaluation Landscape

Evaluating AE–SSL anomaly detectors in WSNs settings is intrinsically challenging, and the current literature reflects substantial variability in both data and protocol choices. Studies rely on heterogeneous datasets, apply non-uniform preprocessing and windowing procedures and report performance using an eclectic mix of indicators, which complicates direct cross-paper comparison [93]. As a result, apparent improvements may reflect differences in data curation, split strategy or scoring conventions rather than genuine methodological advances. This concern is amplified in WSNs deployments, where irregular sampling, cross-node correlation and tight energy budgets distinguish the operating regime from many mainstream IoT benchmarks; consequently, dataset selection and metric design can strongly shape reported outcomes [94]. A clear characterization of evaluation practice is, therefore, necessary to interpret existing evidence, identify credible baselines and support more reliable, reproducible comparisons in future research [95].

6.2. Datasets for WSN Anomaly Detection

Simulated WSNs traces dominate the literature, largely because collecting diverse, well-instrumented anomalies at scale in operational networks is difficult and expensive [96]. Typical simulators generate networks with tens to hundreds of nodes under stylized topologies (e.g., grids, trees, clustered layouts) and allow controlled injection of events such as communication faults, routing disruptions, replay activity, packet corruption and node dropout [97]. This controllability is valuable for stress testing under calibrated noise and failure regimes, but simulation assumptions can flatten the heterogeneity and irregularities that characterize field deployments, potentially overstating generalization to nonstationary, resource-constrained conditions. A concise summary of commonly used datasets and their suitability for AE–SSL evaluation is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Representative datasets used in AE–SSL anomaly-detection studies targeting WSNs and closely related IoT/network settings, and their suitability for evaluation.

Real-world datasets are comparatively scarce and often tied to specific application contexts. Environmental monitoring deployments commonly provide long, regular sequences of temperature, humidity or air-quality measurements [103]. Industrial WSNs traces, by contrast, tend to exhibit greater volatility, multiple sensing modalities and more pronounced missingness due to harsh operating conditions and intermittent connectivity [104]. Smart-home and building-automation datasets contribute additional modalities such as occupancy, energy and motion telemetry, yet they are frequently limited in scale and may not reflect diverse network topologies [105]. Across these real deployments, anomaly labels are typically incomplete or absent at node granularity, which favors self-supervised representation learning while complicating supervised baselines and standardized comparisons [106].

To broaden coverage, many studies also rely on open benchmarks such as WSNs-DS, IoT-23, SensorScope and selected UCR subsets, although each captures only a partial slice of the operational challenges encountered in geographically distributed WSNs [107]. Across all dataset categories, recurring characteristics include sparse labeling, strong spatio-temporal dependence and heterogeneous sampling behavior, reinforcing the need for methods that can learn robust structure directly from raw telemetry under realistic uncertainty [108].

6.3. Evaluation Metrics

Assessing AE–SSL anomaly detectors in WSNs typically requires more than a single detection score: reported evidence spans classical classification metrics, representation-quality probes, and deployability indicators that reflect operational overhead. For binary detection settings, studies most often report accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score [109]. Among these, F1-score is generally the most informative under heavy class skew because it balances missed detections against false alarms. AUC–ROC is also widely used as a threshold-agnostic summary of ranking quality; however, in WSN evaluations, its interpretation can vary with class imbalance, scoring conventions, and how negatives are constructed or sampled.

Anomaly-aware reporting and evaluation unit. Because WSN anomalies differ in duration, prevalence, and dependence structure, metric selection should be tied to both the anomaly type and the intended reporting unit. For point-like events (isolated deviations), sample- or short-window reporting is common; precision/recall/F1 typically provide clearer insight than accuracy when anomalies are rare, while AUC–ROC can be included provided the scoring convention and class skew are stated. For contextual anomalies (sustained deviations conditioned on operating state), window-level reporting with explicitly defined windowing and aggregation is preferable, since prolonged events can artificially inflate scores if the evaluation unit is not made explicit. For collective anomalies (cross-node and temporal correlation patterns), evaluation should match the target of detection (e.g., node-level localization versus network-level alarms), and detection scores are most interpretable when paired with evidence that relational structure is captured (e.g., reconstruction-error summaries and latent-space probes). Across all regimes, explicitly specifying the reporting unit (sample/window/node/network) and any negative construction assumptions materially improves cross-paper comparability.

For reconstruction-oriented pipelines, authors often report mean squared error and related input–reconstruction distances as direct indicators that nominal structure has been learned and that anomalies induce systematic reconstruction degradation [110]. In SSL-enhanced settings, evaluation increasingly includes representation diagnostics: qualitative projections (e.g., t-SNE or UMAP) and quantitative probes such as linear evaluation are used to assess whether the self-supervised objective yields embeddings that are separable and transferable without task-specific tuning.

Finally, because WSN deployments are resource-constrained, system-facing metrics are becoming part of the evidentiary standard alongside detection quality [111]. Commonly reported proxies include inference latency, parameter count, memory footprint, and occasionally operation counts (e.g., multiply–accumulate estimates). Taken together, these measures support a multidimensional assessment that links detection performance to representation utility and operational feasibility, rather than treating accuracy alone as sufficient evidence of progress.

6.4. Evaluation Protocols

Evaluation practice for AE–SSL anomaly detection remains heterogeneous and protocol variation is a primary source of limited reproducibility. A common pattern is the one-class setup in which training is restricted to nominal data, followed by testing on mixtures of normal and anomalous segments [112]. For temporal telemetry, most studies rely on sliding-window segmentation, yet window lengths and overlap ratios differ substantially across papers, often reflecting sampling rate and application context rather than a shared convention [113].

Decision rules for anomaly scoring and thresholding also vary. Reconstruction-centric AEs frequently calibrate thresholds using simple statistics of training error (e.g., mean plus a multiple of the standard deviation) [114]. In contrast, SSL-augmented pipelines may score anomalies through distances in embedding space, density estimates or downstream classifiers trained on learned representations, which introduces additional degrees of freedom in scoring and calibration. Reporting discipline is similarly uneven. While some recent studies include multi-seed runs, ablation analyses and explicit hyperparameter logs, many present results from a single configuration with limited sensitivity analysis, making it difficult to attribute gains to the proposed method rather than to favorable protocol choices [115].

Without harmonized preprocessing, standardized splits and clearer disclosure of scoring and calibration procedures, improvements reported across papers can be driven as much by experimental design as by algorithmic innovation.

6.5. Integrated Commentary on Current Limitations

Several constraints recur across the dataset landscape, metric choices and protocol design. First, there remains a shortage of widely accepted WSNs benchmarks that simultaneously reflect realistic topology dynamics, multimodal sensing and clearly documented anomaly events, limiting the field’s ability to test generalization under deployment-like conditions [116]. Second, reporting is often incomplete with respect to deployment-relevant costs. Energy expenditure, inference latency, memory footprint and communication overhead are not measured or reported consistently, which makes it difficult to judge whether improved detection scores translate into practical feasibility [117]. Third, reproducibility is uneven: key details such as data partitioning rules, preprocessing order, windowing configurations and the specification of SSL pretext tasks and augmentations are frequently underspecified, preventing faithful replication and fair comparison. Collectively, these gaps introduce substantial uncertainty into the evidence base and obscure how AE–SSL methods will behave in long-running, safety-critical or mission-constrained WSNs deployments [118].

7. Challenges and Future Research Agenda

7.1. Technical Challenges

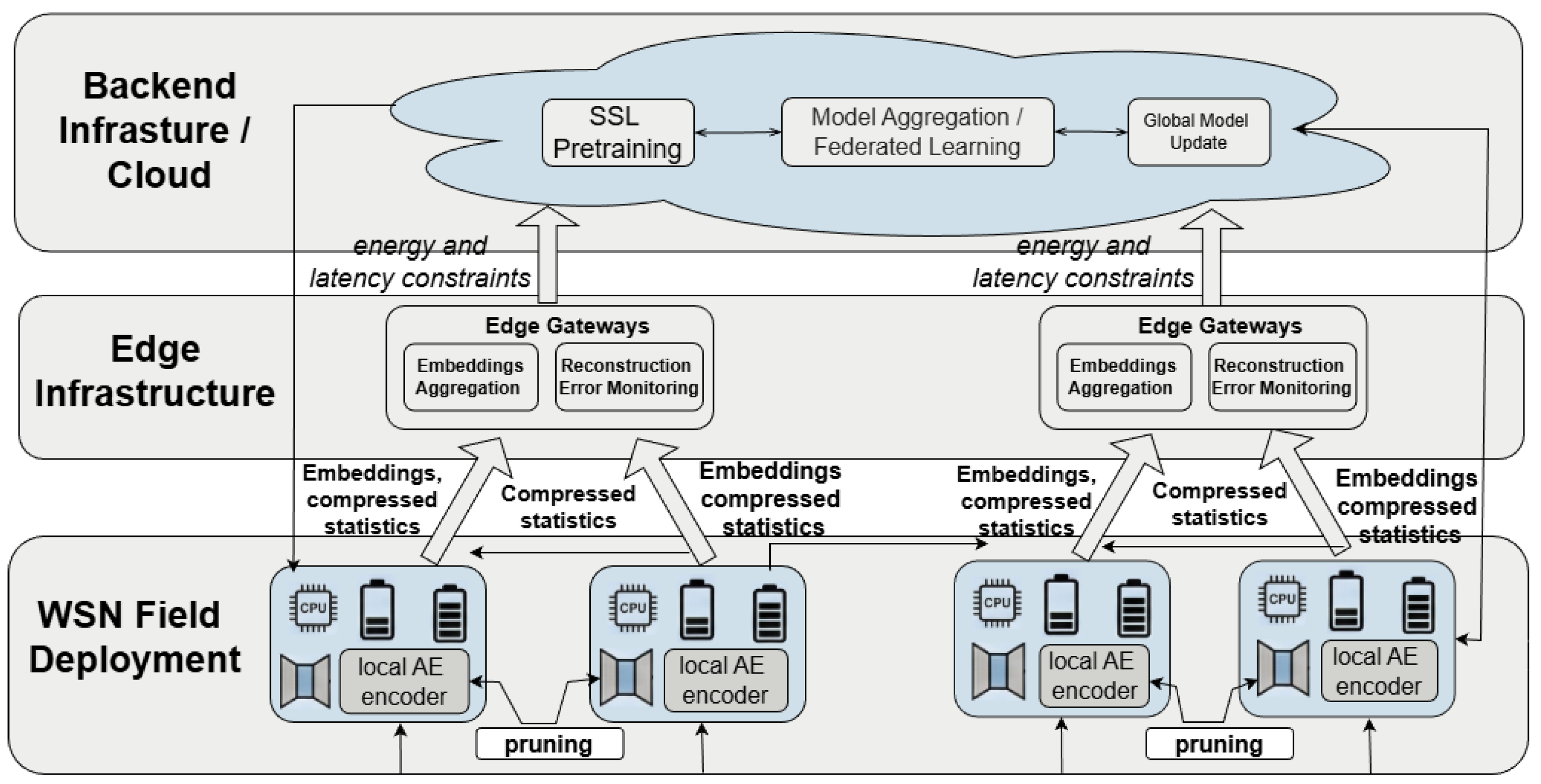

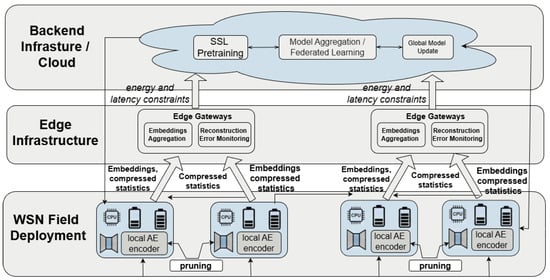

Despite recent advances in self-supervised autoencoder-based anomaly detection, several technical obstacles continue to limit reliable deployment in WSNs [119]. Contemporary models can learn informative latent structure from multivariate telemetry, but their behavior often becomes less stable as network scale and operational variability increase. When extended to hundreds or thousands of nodes, training can exhibit brittle optimization dynamics, inconsistent convergence or poorly conditioned embeddings that are difficult to diagnose and validate, particularly in spatio-temporal and graph-conditioned settings [120]. Interpretability remains an equally persistent gap: anomaly alarms are frequently delivered as scores or labels without actionable attribution, making it hard for operators to identify whether the trigger reflects sensor drift, communication artifacts, routing disruption or a coordinated attack. Data irregularities further complicate learning. A deployment-aware view of how on-node encoding can be paired with upstream self-supervised training and aggregation is illustrated in Figure 4. Missingness, class imbalance and non-uniform sampling rhythms can bias reconstruction losses and distort self-supervised objectives, leading to detectors that overreact to benign noise or degrade under gradual drift [121]. Finally, the effectiveness of SSL pretext tasks is not uniform across modalities and domains; objectives that perform well in one deployment can become unstable or uninformative under heterogeneous sensors, evolving topology or shifting environmental regimes [122].

Figure 4.

Example deployment-aware architecture combining on-node autoencoding with upstream self-supervised training and model aggregation.

7.2. Deployment and Resource Constraints

A central obstacle for WSN anomaly detection is the persistent mismatch between experimental conditions and field operation. Many AE–SSL frameworks are designed and validated on workstation-class platforms under assumptions of stable power, ample memory, and reliable connectivity that seldom hold for microcontroller-class sensor nodes. In practice, tight energy and storage budgets constrain architectural capacity and operational behavior, forcing trade-offs in model depth, latent dimensionality, and how frequently models can be updated or recalibrated [123]. While compression techniques such as pruning, quantization, and mixed-precision inference are increasingly mature, their adoption within AE–SSL pipelines remains uneven and the impact of compression on anomaly sensitivity, and calibration is not always quantified [124]. Offloading computation through edge–cloud partitioning can mitigate node-side constraints, but it introduces new failure modes, including added latency, synchronization requirements, and increased communication overhead that can conflict with duty-cycled operation [125]. These challenges are compounded by limited system-level reporting: many studies provide detection metrics without detailed energy, runtime or bandwidth profiles, leaving deployability largely speculative. Progress toward real-world readiness therefore depends on designing AE–SSL methods with explicit energy, memory, and communication constraints as first-order objectives rather than after-the-fact considerations [126].

Comparative overhead remarks across AE-SSL families (qualitative synthesis). Because overhead reporting is uneven across the surveyed literature, defensible numeric aggregation is rarely possible; nevertheless, several relative cost drivers recur by family. Reconstruction-centric AEs are typically lightweight at inference (one forward pass per window) whereas AE–SSL hybrids primarily increase training cost through auxiliary heads and pretext-task computation. Topology-aware (graph) variants impose additional compute and activation memory due to message passing and neighborhood aggregation with overhead scaling, graph size/density and temporal window length.

Reported deployment and overhead indicators (traceable inventory). To keep this qualitative synthesis auditable despite heterogeneous reporting, Table 4 lists the assumed deployment locus and any explicitly reported latency, memory or energy indicators for a deployment-explicit subset of exemplars. Fields not reported by the original studies are marked as NR and missing values are not imputed.

Table 4.

Reported deployment and overhead indicators across representative AE-based anomaly monitoring studies (NR = not reported; values are as reported and not normalized across platforms or protocols).

Minimal reporting checklist for cross-paper cost comparison. To improve comparability and reproducibility, future AE–SSL studies should report, at minimum, (i) parameter count and an operation proxy (MACs/FLOPs) per window, (ii) peak memory (weights plus activations) at the stated precision, (iii) inference latency on representative edge hardware (or a clearly defined proxy), and (iv) communication volume per update round (bytes per client per round), together with update frequency for distributed or federated settings.

7.3. Real-World Readiness and Deployment Constraints

Real-world readiness is shaped not only by compute and energy budgets, but also by how inference and learning are mapped onto the sensing hierarchy. Some AE–SSL designs implicitly assume end-to-end execution on sensor nodes, whereas others push representation learning to cluster heads or cloud services and retain only lightweight scoring or feature-extraction components at the edge [133]. These placement choices induce distinct trade-offs: edge-heavy deployments can reduce latency and dependence on backhaul connectivity but may be limited in model capacity; offloaded pipelines can support richer training and aggregation but introduce communication overhead, synchronization latency, and additional attack surfaces that can affect integrity and availability [134]. In operational WSNs, intermittent links, missing readings, and infrequent maintenance further complicate both on-device self-supervised adaptation and centralized retraining cycles [135].

Achieving robust deployment, therefore, requires architectures that degrade gracefully and update mechanisms that preserve continuity of monitoring. Models should maintain acceptable behavior under node dropout and partial observability and update procedures should refresh parameters without destabilizing running detectors or violating duty-cycle constraints [136]. Incremental and federated AE–SSL strategies are particularly attractive in this regard: local encoders can adapt to site-specific conditions while exchanging compact updates that limit bandwidth use and reduce raw-data exposure [137,138]. However, evidence from truly embedded deployments remains limited and practical questions around convergence under non-IID data, scheduling under intermittent connectivity and energy-aware aggregation are not yet well understood, so that long-lived WSN installations remain trustworthy over time.

7.4. Robustness, Security, and Reliability Challenges

Table 5 summarizes recurring challenges, concrete research directions, and their expected impact for deployable AE–SSL systems in WSNs. Robustness remains comparatively underemphasized in many AE–SSL anomaly-detection pipelines. Although denoising and variational formulations can attenuate unstructured measurement noise, they often remain vulnerable to structured operational disturbances that are common in deployed WSNs, including coordinated node outages, clock misalignment, routing and congestion irregularities and spoofed or replayed sensing signals. Security considerations are similarly underspecified: only a limited subset of studies explicitly evaluates adversarial conditions or incorporates threat-aware objectives that could harden representations against intentional manipulation [139]. Work in adjacent anomaly-monitoring settings has begun to incorporate explicit adversarial evaluation for example through bidirectional-consistency discrimination to identify adversarial perturbations in deep-learning based soft sensors. These consistency-based defenses reinforce the need to treat adversarial validation and threat-aware objectives as first-class evaluation components when AE-SSL representations are deployed in open environments [140]. Long-horizon reliability further complicates deployment because sensing distributions evolve gradually due to seasonal effects, hardware aging and changing workloads; under these shifts, reconstruction-dominated detectors can become miscalibrated and exhibit unstable decision boundaries [141]. Dependable operation in open, fault-prone environments will therefore require designs that explicitly model and anticipate failure modes and that couple detection with principled adaptation, calibration and security-aware validation rather than relying on post hoc error signals alone.

Table 5.

Challenges, Future Research Directions and Expected Impact for AE–SSL Frameworks in WSNs.

7.5. Reproducibility and Benchmarking Limitations

Despite growing enthusiasm for self-supervised learning, reproducibility in AE–SSL research has progressed more slowly. Public datasets that capture realistic WSNs topology, sensing heterogeneity and well-documented anomaly events remain limited and many studies continue to depend on proprietary traces or simulation outputs whose generation settings are only partially specified [142,143]. Code availability is also uneven. Even when repositories are released, differences in preprocessing order, feature construction, windowing parameters or train–test partitioning can introduce subtle shifts that materially affect reported outcomes. The problem is amplified for SSL-based pipelines, where configuration choices, including pretext-task definitions, augmentation policies and contrastive sampling strategies, often strongly shape representation quality and, consequently, detection performance [144,145]. In this environment, headline gains can reflect extensive protocol tuning as much as genuine architectural advantage. More unified benchmarks, standardized reporting conventions and transparent end-to-end evaluation pipelines are, therefore, necessary to support fair comparison and to establish whether proposed methods generalize beyond controlled experimental regimes.

7.6. Future Research Agenda

As this survey is taxonomy-driven, the forward agenda is derived directly from the axes in Section 4 and the evidence gaps identified through the comparative synthesis and evaluation analysis (Section 5 and Section 6). We therefore express the outlook as eight explicit testable research questions (RQ1–RQ8), each anchored to one or more axes (objective, architecture, data context, evaluation, deployment and security). Rather than broad directions, each question specifies what remains under-explored, why it is consequential under WSN constraints and what would constitute credible validation under realistic protocols. Table 6 distills this agenda into eight research questions. In aggregate, the questions prioritize (i) objective design that remains stable under missingness and drift (RQ1) (ii) resource-aware architectures and compression that preserve anomaly sensitivity (RQ2) (iii) data-context realism under dynamic topology and partial observability (RQ3) and (iv) operational utility through localization and interpretable decision support (RQ4) Complementary themes include deployment-grade adaptation via continual or federated self-supervision (RQ5) decision stability through calibration and uncertainty-aware scoring (RQ6) explicit threat-aware robustness evaluation (RQ7) and reproducible protocol-aligned benchmarking and reporting (RQ8).

Table 6.

Taxonomy-driven research questions (RQ1–RQ8) for AE–SSL anomaly detection in WSNs and their corresponding validation expectations.

Across the agenda, progress is most credible when demonstrated under WSN-realistic protocols: multi-seed reporting; long-horizon evaluation under drift and missingness; explicit operating-point and false-alarm control; and system-level profiling (latency, memory and energy proxies) under matched computational and communication budgets.

8. Conclusions

This survey has synthesized the evolution of anomaly detection in Wireless Sensor Networks from reconstruction-centric pipelines to self-supervised frameworks that leverage temporal continuity, spatial coupling and increasingly, graph-structured reasoning. By organizing the literature through a unified taxonomy spanning learning objectives, architectural backbones, data context and evaluation practice, the review highlights a clear methodological shift toward richer representation learning. At the same time, it makes equally clear that progress is constrained by recurring gaps in scalability, interpretability and deployment feasibility.

A central outcome of this work is the consolidation of a fragmented research landscape into a coherent methodological account. Through cross-cluster comparison of AE-only, AE–SSL hybrid and topology-aware approaches, the survey differentiates advances that reflect genuine improvements in robustness and generalization from results that are difficult to interpret due to inconsistent datasets, heterogeneous preprocessing or incomplete reporting. This synthesis provides a grounded reference for researchers designing anomaly detectors for distributed sensing and for practitioners seeking to judge which classes of methods are credible under realistic operational constraints.

The analysis further underscores a persistent tension between algorithmic sophistication and practical viability. While self-supervised autoencoders can deliver label-efficient learning and improved resilience to noise, their operational value depends on alignment with embedded limitations, intermittent communication and long-horizon drift. Without explicit attention to energy cost, memory footprint, calibration stability and resilience to missingness and topology change, high detection scores alone are insufficient evidence of deployability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M.S. and I.K.; methodology, R.M.S., Y.-D.L. and I.K.; validation, R.M.S. and Y.-D.L.; formal analysis, R.M.S. and Y.-D.L.; investigation, R.M.S.; resources, I.K.; data curation, R.M.S. and Y.-D.L.; writing—original draft, R.M.S.; writing—review and editing, R.M.S., Y.-D.L. and I.K.; visualization, R.M.S. and Y.-D.L.; supervision, I.K.; project administration, I.K.; funding acquisition, I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This result was supported by the “Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE)” through the Ulsan RISE Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Ulsan Metropolitan City, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-07-001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Taj, I.; Zaman, N. Towards industrial revolution 5.0 and explainable artificial intelligence: Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2022, 12, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigka, M.; Dritsas, E. Wireless Sensor Networks: From Fundamentals and Applications to Innovations and Future Trends. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 96365–96399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berahmand, K.; Daneshfar, F.; Salehi, E.S.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y. Autoencoders and their applications in machine learning: A survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakati, A.; Bhattacharjya, U.; Medhi, J.P.; Sarma, K.K. AACNet: Attention aided CNN-autoencoder network for precise categorization of respiratory conditions from HRCT scans. Netw. Model. Anal. Health Inform. Bioinform. 2025, 14, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, D.; Bouadjenek, M.R.; Dazeley, R.; Aryal, S. Data-driven machinery fault detection: A comprehensive review. Neurocomputing 2024, 627, 129588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Rawat, P.; Chauhan, S. Contrastive self-supervised learning: Review, progress, challenges and future research directions. Int. J. Multimed. Inf. Retr. 2022, 11, 461–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, L.; Gouk, H.; Loy, C.C.; Hospedales, T.M. Self-supervised representation learning: Introduction, advances, and challenges. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2022, 39, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yin, H.; Xia, X.; Chen, T.; Li, J.; Huang, Z. Self-supervised learning for recommender systems: A survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 36, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jin, M.; Pan, S.; Zhou, C.; Zheng, Y.; Xia, F.; Yu, P.S. Graph self-supervised learning: A survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 35, 5879–5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, I.R.; Joyner, J.; Lickfold, C.; Guo, Y.; Bennamoun, M. A practical tutorial on graph neural networks. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2022, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]