Abstract

The aim of the study was to determine the effects of sprint interval training (SIT) on anaerobic and aerobic performance in young physically active men, as assessed by maximal power (Pmax), maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max), and the second ventilatory threshold (VT2). The data obtained were presented against the background of the effects of aerobic interval training. Participants (n = 45) aged 19–27 years were recruited into three groups of 15 participants each. The first group performed SIT, the second performed aerobic interval training (AIT), and the third group was without any intervention (control—CON). In each study group, participants performed somatic measurements twice (before and after the exercise intervention), the Wingate test (assessing peak anaerobic power (PP)), and a graded exercise test assessing aerobic performance. The training intervention in the SIT and AIT groups lasted 6 weeks, with three training sessions per week. The duration of a single session in AIT was constant throughout the intervention and lasted 60 min, while in SIT it lasted 17 min (first session), and the longest training session lasted 30 min. Training in the SIT group resulted in a significant increase in absolute anaerobic peak power (p < 0.001, ES = 0.36), while no significant change in PP was observed after AIT (p = 0.13, ES = 0.24). Both training protocols (SIT and AIT) significantly improved VO2max (p = 0.03, ES = 0.39 and p = 0.02, ES = 0.55, respectively) and absolute Pmax (p < 0.001, ES = 0.68 and p = 0.02, ES = 0.36). Only in the AIT group were statistically significant changes related to VT2 observed: after training, oxygen uptake at VT2 increased significantly (p = 0.04, ES = 0.64). The SIT protocol improved both aerobic (VO2max) and anaerobic (PP) performance, but did not affect the VT2 level. The data indicate that SIT can be used for training in sports disciplines requiring aerobic and anaerobic performance.

1. Introduction

Sprint interval training (SIT) is defined as training with several tens of seconds of effort with long (several minutes) recovery breaks and is one of the forms of high-intensity interval training [1]. SIT is usually used to improve anaerobic performance (phosphagen and glycolytic) and to improve speed, muscle power, and acid–base balance tolerance [2,3]. SIT is based on anaerobic efforts performed with external resistance at maximal power and is a training method that induces physiological adaptations most likely resulting from increased activity of glycolytic, oxidative, and phosphagen enzymes [4,5]. Systematic SIT training induces a number of biochemical changes. It has been proven that SIT training increases the activation of glycogen-metabolizing enzymes, glycolytic enzymes, oxidative enzymes, and creatine kinase or aminotransferase [4,5]. It also increases the release of calcium ions (Ca2+) from the sarcoplasmic reticulum surrounding striated muscles [4]. The desired physiological effects of SIT include an increase in VO2max and peak anaerobic power (Pmax), as well as an improvement in the oxidative capacity of skeletal muscles [6,7,8]. After SIT training, an increase in resting muscle glycogen content of 26% was observed, as well as differences in muscle fiber changes to type IIa [9].

Although SIT is strictly anaerobic training of supramaximal intensity, its use in improving aerobic performance is increasingly being considered [10,11], as metabolic adaptations to this training may also promote improvements in aerobic performance. Interval sprint training can therefore be an excellent substitute or supplement to endurance training. Previous studies [12,13,14] have shown that SIT not only increases peak anaerobic power (PP) and mean power (MP), but may also increase maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) [11]. Similar conclusions were reached by other authors [12,13,14,15], proving the effectiveness of SIT in improving aerobic capacity in a similar way to low- or medium-intensity training of long duration. High-intensity interval training not only improves VO2max, but also leads to a reduction in body fat, and the changes observed were similar after both SIT and high-intensity interval training [11,16]. However, the data are not conclusive. Another study [17] showed that high-intensity training did not improve aerobic performance among professional judo practitioners. The results of the meta-analysis [18] indicate that long-term high-intensity interval training (power or velocity between the second ventilatory threshold and maximal oxygen consumption) may be the optimal form of interval training to augment aerobic performance. A moderate effect in favor of high-intensity interval training over SIT in maximal power (Pmax) or maximal aerobic velocity was detected.

In order to assess aerobic performance, VO2max and the intensity of work at metabolic (ventilatory) thresholds (VT1 and VT2) are taken into account [19,20,21]. After exceeding the first ventilatory threshold (VT1), metabolic acidosis occurs, causing an increase in lactate, which the body is able to compensate for [22]. Increasing exercise intensity causes the next metabolic threshold to be exceeded, which is the second ventilatory threshold (VT2), an important indicator in the assessment of aerobic endurance [23,24]. Exceeding VT2 causes hyperventilation and the development of uncompensated metabolic acidosis [25]. To improve aerobic capacity, training is usually performed at a submaximal continuous or intermittent intensity rather than supramaximal intensity, as in SIT. The study compared the effectiveness of two different training methods in improving physical performance—aerobic (AIT) and anaerobic (SIT)—i.e., methods that produce different physiological and biochemical effects. The biochemical benefits include increased oxidation of fatty acids and glucose [26], increased activity of enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation (citrate synthesis, lactate dehydrogenase, succinate dehydrogenase, phosphofructokinase) [27,28], and increased ATP production in mitochondria during physical exercise and the number of mitochondria in type Ia muscle fibers [29]. AIT increases the activity of oxidative enzymes (creatine kinase, myokinase, ATPase, phosphofructokinase, lactate dehydrogenase) [30,31,32,33,34,35] and increases erythrocyte production [36]. This type of training reduces systolic and diastolic blood pressure and improves myocardial function and vascular endothelial function [37]. Endurance training improves VO2max and shifts VT2 to higher exercise intensities, primarily through increased blood flow to skeletal muscle [38,39,40]. AIT training improves oxygen transport to cells and improves the functioning of the cardiorespiratory system [35,41]. AIT also reduces body fat [42] and causes bradycardia, thereby increasing heart rate reserve [43,44]. A typical, traditional AIT has submaximal intensity, usually not exceeding VT2, and is therefore not considered a high-intensity interval training [1].

The aim of the study was to determine the comprehensive effects of sprint interval training on exercise capacity (anaerobic and aerobic capacity), and in particular on endurance capacity among young untrained men, as assessed by maximal oxygen uptake and the second ventilatory threshold. For the aerobic metabolism, VO2max reflects maximal aerobic power measured during maximal exercise. VT2 reflects aerobic capacity. In the same manner, for anaerobic glycolysis, also called “lactic anaerobic metabolism”, peak power (PP) reflects maximal anaerobic power, and mean power (MP) reflects anaerobic capacity in the Wingate Anaerobic Test. In this study, the data obtained were presented in contrast to the effects of aerobic interval training. We hypothesized that sprint interval training would be as effective in improving endurance capacity as traditional aerobic interval training and, unlike AIT, would be effective in improving anaerobic capacity. Thus, SIT may prove to be a more versatile training method, affecting both aerobic and anaerobic capacity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The participants were physically active, but this activity was very varied, unsystematic, and varied in intensity and duration. For the duration of the intervention, they refrained from other physical activities they had previously been engaged in. They were not trained athletes and did not participate in any sports competitions.

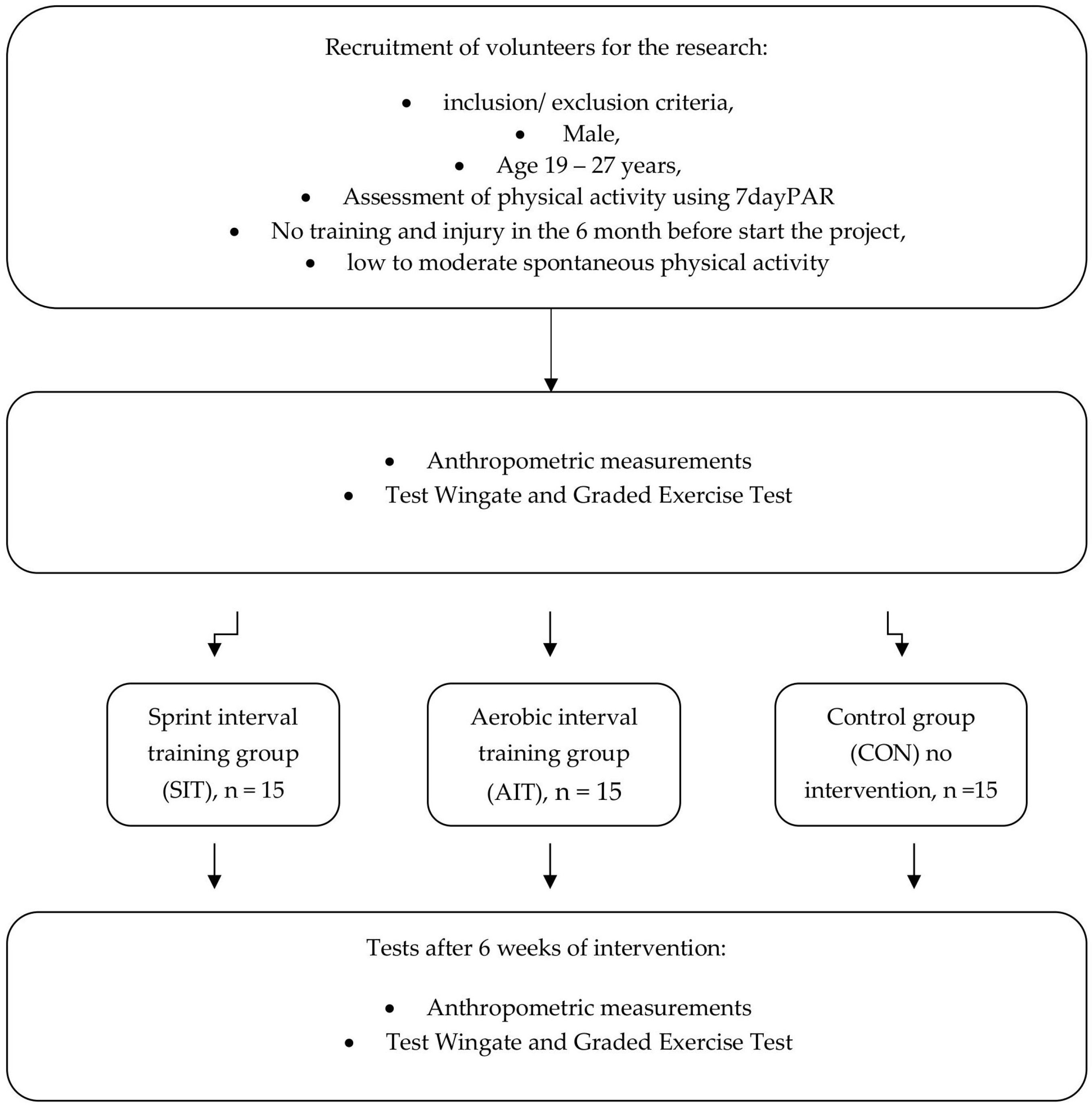

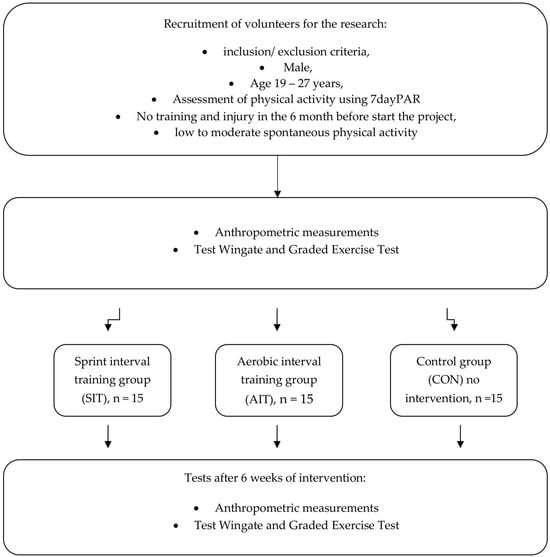

The study was experimental and designed as a parallel study. The study involved physically active men divided randomly into three groups. Randomization was performed using an online tool (www.randomizer.org, accessed on 6 March 2023). The first group performed SIT, the second group performed AIT. The last group did not undergo any training intervention (control group—CON). The sample size was determined before the study began. G*Power version 3.1.9.7 software (Germany) was used to calculate the sample size. The following data were entered into the software: test family = f tests; statistical test = ANOVA with repeated measures, within-between interaction; type of power analysis = calculation of the required sample size with assumed α, power, and effect size. The parameters entered into the software were as follows: effect size f: 0.25; error probability α: 0.05; power: 0.80; number of groups: 3; number of measurements: 2; correlation between measurements: 0.5; non-sphericity correction: 1.0. The required total sample size was 42 participants. Due to possible dropouts from the study, we decided to recruit 45 participants (15 per group). All participants completed the training sessions, and a complete set of data was obtained. Each person in the study group gave their written consent to participate in the study, and approval was obtained from the Bioethics Committee at the Regional Medical Chamber in Krakow, number: No. 187/KBL/OIL/2022 dated 1 July 2022. The exact course of the study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The course of the study.

The following inclusion criteria were used: male gender, age (19–27 years), spontaneous irregular low-to-moderate physical activity, and no medical contraindications to participate in training. Exclusion criteria included obesity and overweight, chronic medical conditions, injuries and trauma within 6 months prior to the start of the project, and training in any sport. Accompanied by the researcher, participants completed a seven-day physical activity questionnaire.

The exercise intervention in the SIT and AIT groups lasted six weeks with a frequency of three times per week. The group without intervention (CON) did not perform exercise training during this time. The study participants were introduced to the exercise test procedures and familiarized with the cycle ergometer technique (E834 Monark, Varberg, Sweden). The study participants were instructed on how to prepare for the exercise tests and training: they should be well rested, should not consume caffeine or alcohol for 24 h before the tests, should maintain their usual diet, and should not consume any dietary supplements during the intervention period. Before the training intervention, somatic measurements, a Wingate test, and a graded test took place, which were then repeated one week after the training. Measurements were taken on a single day. There was a 2 h gap between the Wingate test and the graded test. The exercise tests and workouts took place under similar conditions, with an ambient temperature of approximately 21 °C and a humidity of approximately 40%. The workouts took place under the supervision of a sports/motor training instructor.

2.2. Somatic Measurements

Each participant’s body composition was measured twice (before and after the training intervention), while body height (BH) was measured only once. Body composition was analyzed using a body composition analyzer (IOI 353, Jawon Medical, Seoul, Republic of Korea). The indices measured were: body mass index (BMI), body mass (BM), lean body mass (LBM), body fat percentage (%FM), and body fat mass (FM) expressed in kg. Body height was measured using a stadiometer (Seca 217, Hamburg, Germany) to the nearest 0.1 cm.

2.3. Graded Exercise Test (Ergospirometry)

The graded exercise test, which is a direct method that determines maximal oxygen uptake under laboratory conditions, was conducted on a bicycle ergometer (Ergoline Ergoselect 100, GE, Bitz, Germany) using a Metalyzer 3B ergospirometer (Cortex, Leipzig, Germany). The following indices were measured in the test: power of effort (P), oxygen uptake (VO2), heart rate (HR), and respiratory exchange ratio (RER). To determine ventilatory thresholds, additional indicators were examined: pulmonary ventilation (VE), carbon dioxide production (VCO2), percentage of oxygen in exhaled air (FEO2), percentage of carbon dioxide in exhaled air (FECO2), ventilation equivalents for oxygen (VE/VO2), and carbon dioxide (VE/VCO2). Ventilatory thresholds were determined using the respiratory equivalents method [45,46]. The criteria for the determination of the VT1 were as follows:—minimal level of FEO2 and VE/VO2. The second ventilatory threshold was determined at the intensity at which VE/VCO2 reached a minimum value, FECO2 reached a maximum value, and a second breakdown of the linearity of pulmonary ventilation was observed. To determine VO2max, the following criteria were used: VO2 did not increase with increasing power (plateau in VO2), RER > 1.1, and heart rate (HR) was close to HRmax (±5 bpm) [47]. If no plateau was observed, but the other criteria were met, VO2peak was taken as VO2max. During the first two minutes of the test, resting data were recorded, followed by a four-minute warm-up performed at a power of 60 W. Then, every 2 min, the power of the effort was increased by 30 watts until volitional fatigue.

2.4. Wingate Test

In order to test anaerobic capacity, the Wingate test [48] was used. The following indices were determined in the test: peak power determined in absolute and relative values, mean power also expressed in absolute and relative values, and fatigue index (power loss) (FI). The test used a bicycle ergometer (E834, Monark, Sweden) and software (MCE, JBA Staniak, Warsaw, Poland). When entering the test, the participant had to have the saddle positioned, and then began the test, preceded by a 5 min warm-up with a load of 120 W and a cadence of 60 rpm. At the 2nd and 4th minute, the participant performed a maximum acceleration lasting 5–6 s. After completing the warm-up, the participant rested for 5 min (including 4 min of stretching the lower extremities). The test had a stationary start [49], and the participant’s task was to reach maximum pedaling speed (revolutions per minute) as fast as possible and then maintain it until the end of the test (all-out effort). The Wingate test consisted of a 30 s sprint with a load of 7.5% of body mass. The effort took place in a seated position, and during the Wingate test, the participant was verbally motivated to achieve the highest possible pedaling speed.

2.5. Physical Activity

Prior to the study, participants completed the Physical Activity Recall (PAR) questionnaire, which was used to determine seven days of physical activity [50,51]. Each participant was instructed on how to complete the questionnaire, and it was completed in the presence of the researcher, who clarified any doubts the participant may have had.

2.6. Aerobic Interval Training

Aerobic interval training (AIT) was performed on cycle ergometers (Wattbike, Nottingham, UK). Exercise intensity was determined by power noted at the first and second ventilatory thresholds (VT1 and VT2) (Table 1). The duration of the training was 60 min; before the training, the participant performed a 6 min warm-up with power at VT1, then the participant performed a 6 min effort with power at VT2. Between efforts there was an active recovery of 3 min with power at VT1 (the exercise/recovery ratio was therefore 2:1). During the training session, which lasted 60 min, the participant performed six such series, i.e., 6 min of effort with power corresponding to VT2 and 3 min of active recovery with power corresponding to VT1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of training loads in the AIT group.

2.7. Sprint Interval Training

The SIT was performed on a cycle ergometer (Monark 834, Sweden). Each workout consisted of a warm-up modeled on the Wingate test protocol. Immediately following the warm-up, the men performed 15 s sprint efforts of supramaximal intensity (all-out) with a load of 7.5% of body mass, i.e., a 15 s shortened version of the Wingate test. The participants were instructed to exert the same effort as during the Wingate test, i.e., their task was to sprint at maximum pedaling cadence in each effort. Neither power nor pedaling cadence was controlled during these efforts. For the first 2 weeks, participants performed three such supramaximal efforts and then increased the number of repetitions by one effort per training session per week. Thus, in the third week of training, there were 4 supramaximal efforts per training session, in the fourth week—5 efforts, in the fifth week—6 efforts, and in the last week of training, the number of efforts was reduced to 4. The shortest training session lasted 17 min, and the longest lasted 30 min. Between efforts there was a 4 min active rest, during which participants pedaled at 60 watts (Table 2).

Table 2.

Training plan implemented by the sprint interval training group.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Prior to the study, sample size calculation was conducted using G*Power 3.1.9.7 (Düsseldorf, Germany) software. After the training intervention was performed, the mean and standard deviation were calculated for each variable. STATISTICA 13 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test the distribution of the data, and the Levene test was used to assess the homogeneity of variance. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures or one-factor ANOVA was used to detect differences between groups, differences between test points (change over time), to determine interactions between main effects, and to assess effect size (partial eta squared—ηp2). If the ANOVA results were significant, the Tukey test was used for post hoc analysis. In addition, if the results of the post hoc analysis were significant (p < 0.05), the effect size (ES) was further determined between the baseline and post-training values using Cohen’s d. ES was interpreted as small (0.20), medium (0.50), or large (0.80) [52]. Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

3.1.1. Physical Activity

Physical activity did not differ significantly between groups (f = 2.48, p = 0.07, ηp2 = 0.12). Total energy expenditure during the week was: SIT: 18,745 ± 2677 kcal/week AIT: 21,487 ± 3069 kcal/week CON: 20,804 ± 2972 kcal/week.

3.1.2. Age and Somatic Build

The male participants were of similar age and did not differ in body mass or body composition. None of the workouts caused significant changes in body mass and body composition (Table 3).

Table 3.

Anthropometric measurements of the participants (data are presented as mean ± SD, N = 15 in each group).

3.2. Effects of SIT and AIT on Aerobic Capacity

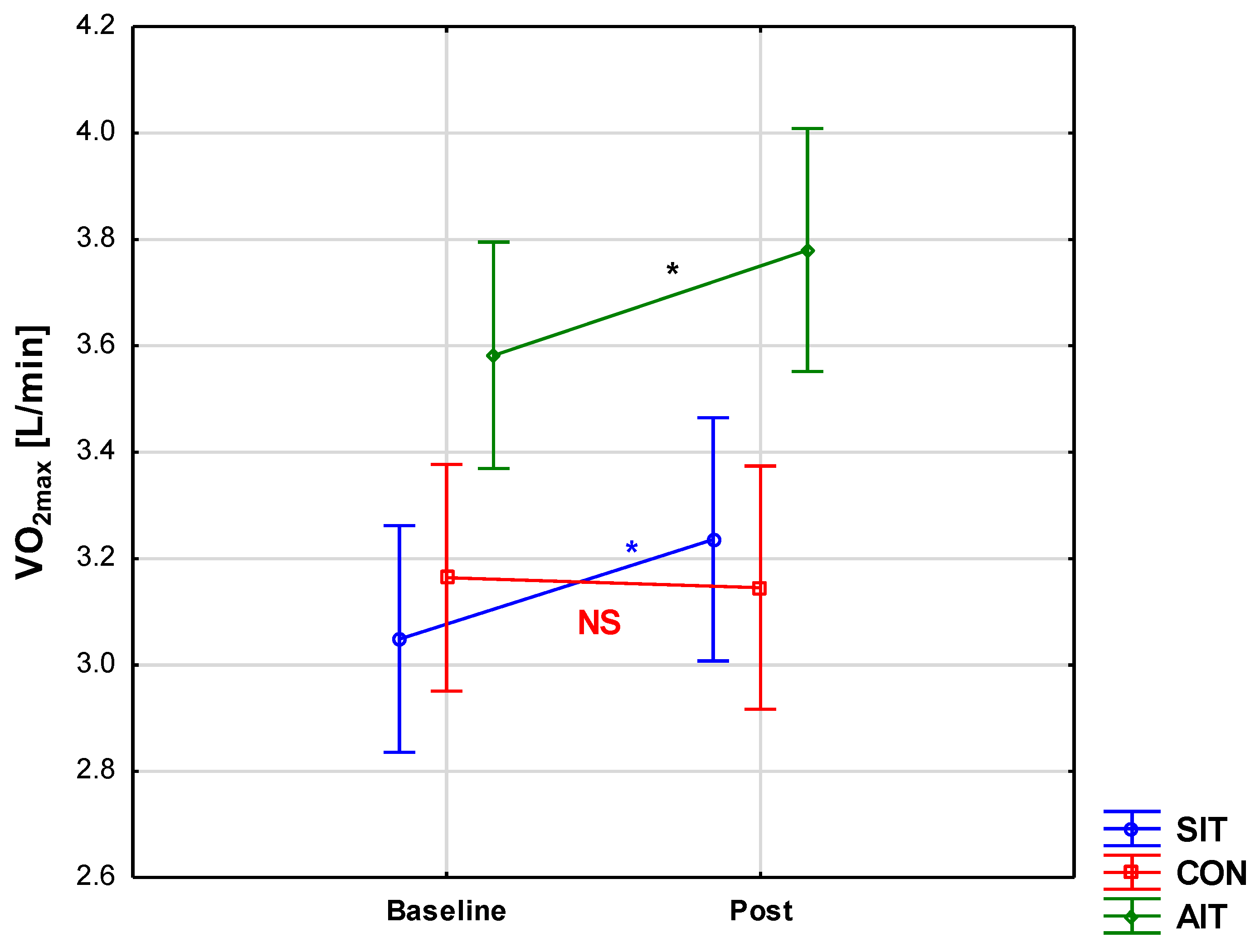

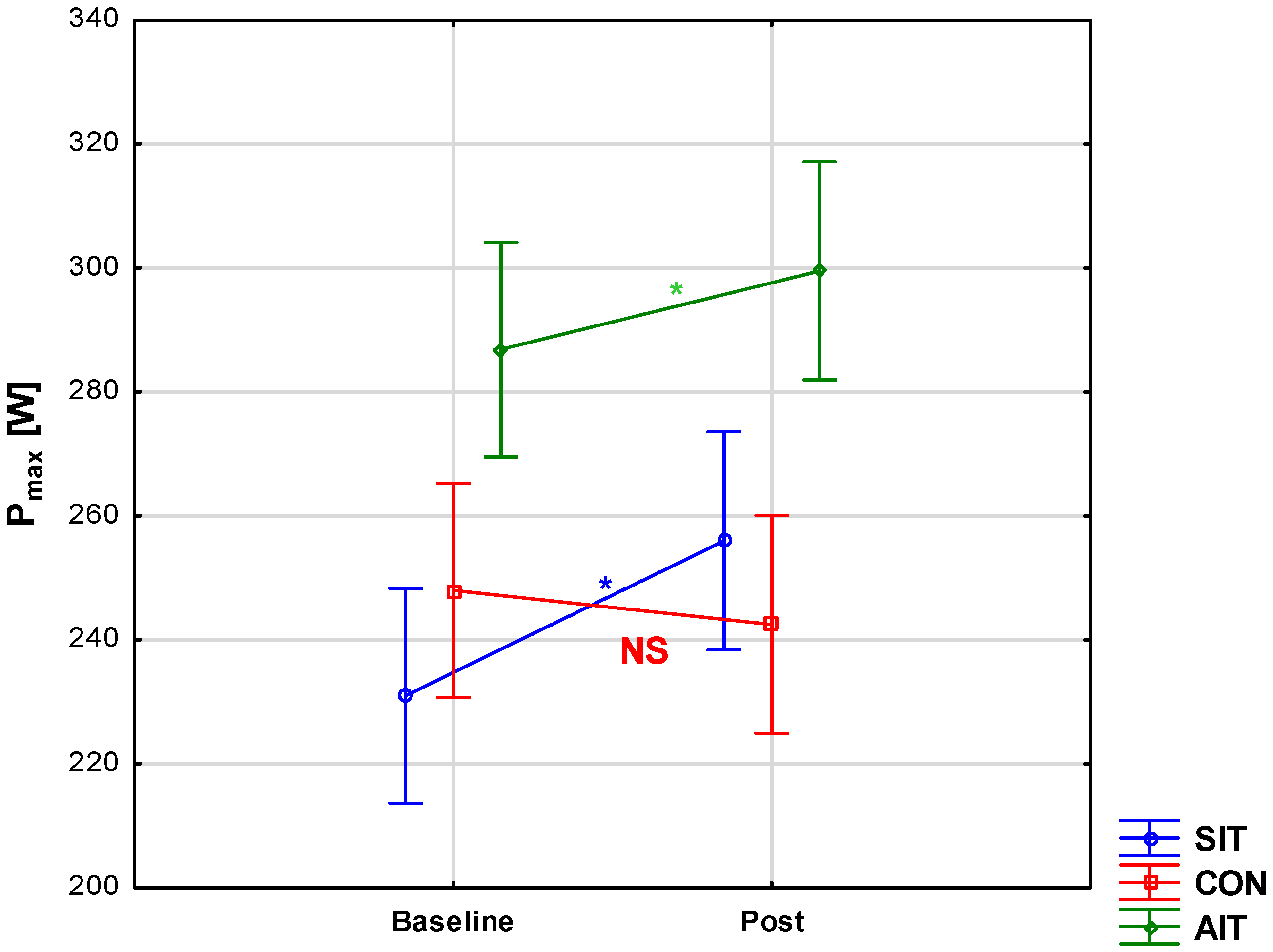

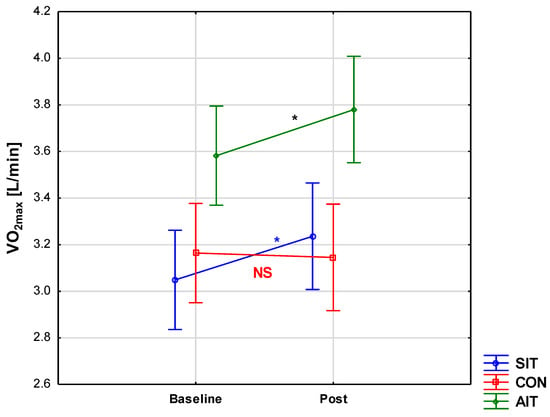

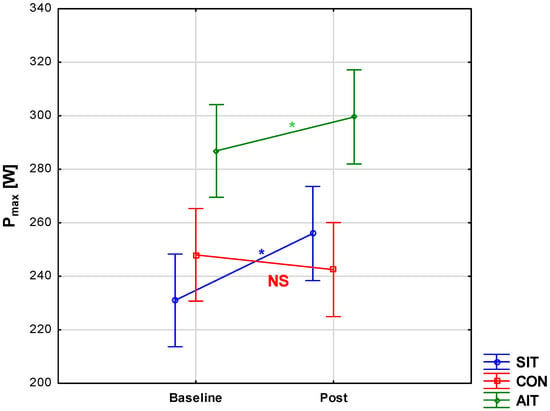

Training in the SIT and AIT groups resulted in a significant increase in absolute VO2max (p = 0.03, ES = 0.39, and p = 0.02, ES = 0.55, respectively; Figure 2). Relative maximal oxygen uptake increased (p = 0.02 and p = 0.04) after training in the SIT and AIT groups (Table 4). Absolute maximal power increased significantly in the SIT and AIT groups (p < 0.001, ES = 0.68, and p = 0.02, ES = 0.36, respectively; Figure 3). Comparing the SIT and AIT groups, significant changes in relative maximal power were observed only in the sprint group (p < 0.001, ES = 0.09) (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Effect of training on absolute maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) (*: p < 0.005; NS: non-significant; vertical bars indicate a 0.95 confidence interval; SIT: sprint interval training; AIT: aerobic interval training; CON: control group).

Table 4.

Effects of training on parameters noted at maximal intensity in graded test (data are presented as mean ± SD).

Figure 3.

Effect of training on maximal power (Pmax) (*: p < 0.005; NS: non-significant; vertical bars indicate a 0.95 confidence interval; SIT: sprint interval training; AIT: aerobic interval training; CON: control group).

3.3. Effects of SIT and AIT on Second Ventilatory Threshold

The applied training significantly increased absolute VO2 only in the AIT group (p < 0.04; ES = 0.64), and this was a moderate effect (Table 5). No significant changes were observed in the other groups.

Table 5.

Effects of training on parameters noted at second ventilatory threshold in graded test (data are presented as mean ± SD).

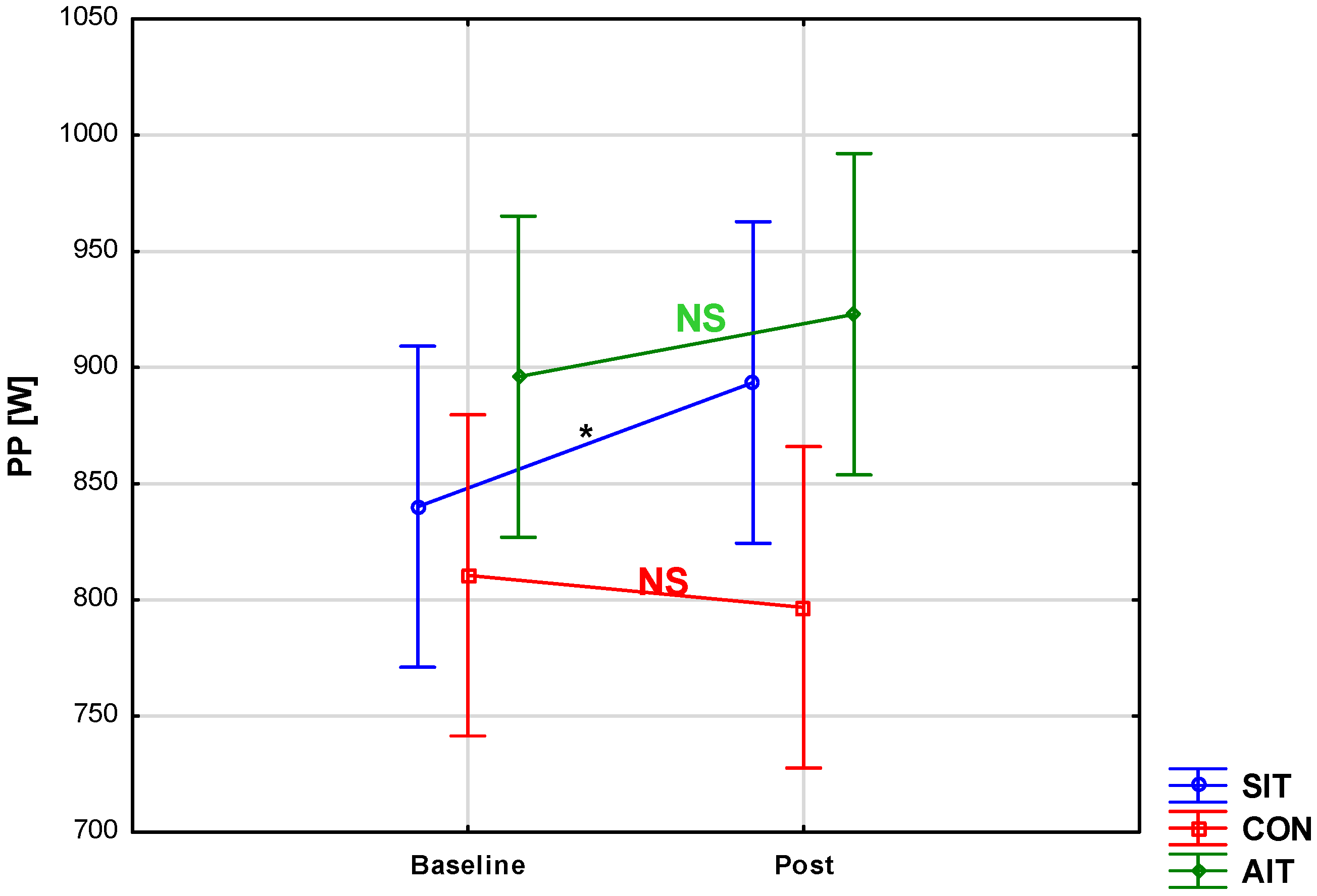

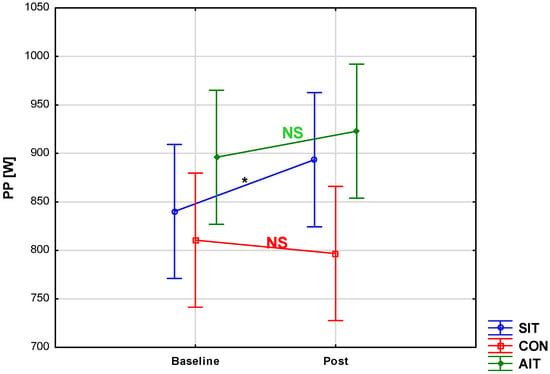

3.4. Effects of SIT and AIT on Anaerobic Capacity

Training in the SIT group resulted in a significant increase in absolute PP (p < 0.001, ES = 0.36; Figure 4). Relative peak power also increased (p < 0.001, ES = 0.61) after training in the SIT group (Table 6). Absolute mean power significantly increased only in the SIT group in absolute (p < 0.001, ES = 0.28) and relative (p = 0.03, ES = 0.40) values (Table 6). A tendency toward an increase in the fatigue index was observed only in the group that completed SIT (p = 0.05, ES = 0.28). No changes were observed in the AIT and CON groups during the observation period.

Figure 4.

Effect of training on anaerobic peak power (PP) (*: p < 0.005; NS: non-significant; vertical bars indicate a 0.95 confidence interval; SIT: sprint interval training; AIT: aerobic interval training; CON: control group).

Table 6.

Effects of training on parameters noted in Wingate Anaerobic Test (data are presented as mean ± SD).

4. Discussion

In this study, we performed a comprehensive assessment of the impact of SIT on exercise capacity, evaluating all performance indicators rather than selected ones, such as VO2max or PP/MP only. This study evaluated whether a form of training with dominant anaerobic metabolism would be equally effective in improving anaerobic and aerobic performance. Sprint interval training and aerobic interval training were used in the training. This is one of the few studies in which VO2max and VT2 were both taken into account in the assessment of aerobic performance. Based on the results of the study, it was hypothesized that sprint interval training would be as effective in improving endurance capacity as traditional aerobic interval training, and at the same time, unlike AIT, it would be effective in improving anaerobic performance. Anaerobic character training has been shown to be effective in improving anaerobic capacity by increasing PP and MP. Sprint interval training, as well as aerobic interval training, was effective in improving maximal oxygen uptake. It was shown that there was a significant increase in absolute VO2max in both training groups. In addition, both training methods resulted in a significant increase in the maximal power obtained in the graded test. The results indicate that the SIT used was as effective as aerobic interval training in improving the indices measured in the graded test. A surprising effect of SIT was an increase in FI, which can be interpreted as a deterioration in anaerobic endurance. There may be two reasons for this. Firstly, SIT was a supramaximal intensity training session and caused high fatigue. Perhaps the period between the 6-week training session and the control exercise test (1 week) was too short for full recovery. Secondly, the duration of the SIT exercise (15 s) was too short to effectively improve anaerobic endurance, which should be verified in further studies.

The novelty of this study is the demonstration that SIT is not an effective training method in improving work intensity at VT2. The applied sprint interval training only induced significant changes in the indicators studied at the maximal intensity level (Pmax and VO2max), while it did not affect their submaximal level, i.e., the second ventilatory threshold. Only AIT training had a significant effect on increasing oxygen uptake at VT2. Thus, it can be concluded that SIT did not significantly affect endurance performance assessed by ventilatory thresholds. Our data, therefore, indicate that SIT may be an interesting alternative to traditional aerobic interval training. It is of great applied importance because, particularly in sports requiring good aerobic and anaerobic capacity, only SIT can be used instead of two separate training methods aimed at improving aerobic and anaerobic capacity. It should be noted, however, that SIT did not induce significant changes in the indicators studied at submaximal levels (i.e., at VT2), but only at maximal intensity. This indicates that in endurance disciplines where VT2 is important, SIT is not a recommended training method.

The reported effects of SIT on peak and mean power were not surprising and could be expected, since power is a product of strength and speed, and the training itself was of a speed (sprinting) nature. This confirms the results of a previous study [53] in which sprint interval training was shown to increase peak power during the Wingate Test. This phenomenon can be explained by the improved efficiency of enzymes after applied sprint training (myokinase, creatine kinase, phosphofructokinase, lactate dehydrogenase, hexokinase, glycogen phosphorylase, aldolase, succinate dehydrogenase, and citrate synthase) [5,54,55].

In contrast, the effects of SIT on aerobic capacity are less obvious and are currently under intensive investigation. The results of the present study are partially consistent with previously published studies [10,11,12,13,15,16,17,53,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67], which showed an increase in maximal oxygen uptake after anaerobic training, with less time commitment from the trainee. It has been shown [10] that high-intensity interval training is able to significantly improve endurance to a similar degree as typical aerobic training.

In planning SIT, it seems crucial to consider the duration, volume, and intensity of this training. Bailey et al. [12] showed that an SIT protocol based on an effort similar to the Wingate Test, in which participants performed only six training units over two weeks, induced a significant increase in VO2peak despite the short training period. A study by Bayati et al. [13] proved that the intensity of SIT does not have to be “all-out”. The effects of SIT at “all-out” and 125% Pmax intensities were similar—both groups showed an increase in VO2max after the training intervention of 9.6% and 9.7%, respectively. The results of these studies may indicate that the key is the high intensity of effort during training, which must be at least maximal intensity. A similar work intensity was used in the present study, in which participants performed supramaximal (all-out) efforts during SIT. The intensity of SIT is referred to as “all-out”, i.e., it must be performed at the highest possible intensity and with the maximum commitment of the trainee [11]. Due to its similarity to the Wingate Test, both athletes and amateurs, when performing SIT, obtain peak power output between 5 and 10 s of exercise, followed by a rapid decline for the subsequent duration of the exercise [68]. The intensity of SIT results in increasing fatigue and decreased power output, as well as lactate accumulation. The recovery between repeated bouts of exercise allows for partial or complete restoration of phosphagen stores and is usually around 4 min [60,69].

Sprint interval training has a beneficial effect on improving maximal oxygen uptake, contributing to endurance [11,52]. The physiological adaptations occurring during SIT are not well understood, but its effect on endurance capacity is most likely due to an increase in the activity of glycogen-metabolizing enzymes, glycolytic enzymes, oxidative enzymes, and creatine kinase or aminotransferase [4,5]. It also increases the release of calcium ions (Ca2+) from the sarcoplasmic reticulum surrounding muscle fibers [4]. Sprint interval training improved maximal oxygen uptake among obese women, compared to a non-training group [14]. In contrast, results from a graded exercise test showed no difference between HRmax and cardiac output, suggesting that the improvement in aerobic performance was not the result of adaptive changes in the cardiovascular system. Improved exercise performance and VO2max after SIT are associated with peripheral muscular adaptations [70]. The effectiveness of SIT in improving aerobic capacity is primarily attributed to enzymatic changes following such training. Anaerobic training, such as SIT, induces changes in VO2max primarily through metabolic adaptations, specifically enzymatic changes, i.e., increased activity of enzymes involved in the phosphagenic, glycolytic, and aerobic energy pathways [5]. Cadefau et al. [4] believed that the increase in creatine kinase activity is greater among sprinters, in whom phosphocreatine is broken down more rapidly, than in non-trainees or those with a sedentary lifestyle. This suggests that training effects in other groups (including athletes) than those in this study may be different.

Despite an increase in VO2max after SIT, there was no significant increase in glycolytic enzyme activity [71]. Although most of the studies had increases in enzyme activity, their relationship to changes in endurance capacity is not clear, as increases in glycolytic enzyme activity in sprint interval training with durations exceeding 10 s are understandable, given the large contribution (and improvement) of the glycolytic energy pathway [69].

The great advantage of SIT is that it can be performed not only with a bicycle ergometer but also with a rowing ergometer or while running. This form of training makes it possible for athletes of different sports to use SIT to improve their endurance capacity—the training becomes sport-specific [17,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. The shortcoming of SIT in the first place is that it is mainly recommended for people who are physically active, rather than those with sedentary lifestyles, due to the high intensity of the exercise [72,73].

AIT and SIT obviously differed in terms of training volume, intensity, load, and duration. AIT sessions lasted ~60 min, whereas a single SIT session lasted about 17–30 min. This large discrepancy in training volume complicates direct comparisons. SIT is more time-efficient, but not strictly equally effective when considering matched training loads. However, the aim of this study was to demonstrate whether SIT can be used instead of AIT in selected sports disciplines to achieve similar (or better) overall training effects, rather than to directly compare the two training methods.

Limitations of the study

This study also did not investigate the physiological and biochemical mechanisms underlying the observed changes, but only assessed the effects of training on aerobic and anaerobic capacity in young, untrained men. The study involved healthy, young men who did not participate in competitive sports. For this reason, the effects of SIT and AIT in athletes need to be verified. In the AIT group, no modifications were made to the training loads during the intervention, which may have reduced the effectiveness of this training. In SIT, the modification of training over time consisted only of increasing the volume of training and not extending its duration, which could potentially have had a better effect on anaerobic endurance (fatigue index). The reported effects, therefore, only apply to the training protocols described. In further studies, it would be additionally advisable to increase the duration of the training mesocycle from 6 weeks to 8 or 12 weeks, testing whether and how these training modifications would affect the variables studied. Manipulating parameters in SIT, such as recovery time and the duration of the “all-out” intensity up to 20 or 30 s (we used 4 min of active recovery and 15 s of effort), could also have other effects, as in previous studies [10,11,12,13,15,16,17,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. Although the mean data indicate beneficial effects of training, the standard deviation values indicate increased data scattering, suggesting that individual responses to training may vary. Additional physical activity of participants during the intervention was not controlled. During SIT, neither power nor pedaling cadence was controlled during efforts.

5. Conclusions

The applied sprint interval training of 6 weeks significantly improved anaerobic performance by increasing PP and MP. In addition, SIT improved aerobic performance by increasing VO2max, similar to the group performing endurance training. The applied SIT did not significantly affect work intensity at the level of the second ventilatory threshold. The only significant increase in VO2 at the level of the second ventilatory threshold was observed as a result of training in the AIT group. The training performed in the SIT group is of great applied importance for both coaches and individuals wishing to improve anaerobic and aerobic performance using interval sprint training. SIT can be a useful solution if the training goal is to increase anaerobic power, maximal power, and maximal oxygen uptake, but this training does not provide benefits to improve submaximal intensity at VT2. SIT improves endurance performance only by increasing maximal values, while it does not affect endurance performance assessed by ventilatory thresholds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and A.D.; methodology, M.M. and A.D.; validation, M.M.; formal analysis, M.M.; investigation, A.D.; resources, M.M.; data curation, A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.; writing—review and editing, M.M.; visualization, A.D.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, M.M.; funding acquisition, A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Physical Education, Kraków, Poland, grant number: 156/MN/INB/2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Regional Medical Chamber in Kraków, Poland (no. 187/KBL/OIL/2022; date: 1 July 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

SIT—sprint interval training; AIT—aerobic interval training; CON—control group; PP—peak power; MP—mean power; FI—fatigue index; Pmax—maximal power; VO2max—maximal oxygen uptake; HRmax—maximal heart rate; RER—respiratory exchange ratio; VT—ventilatory threshold; BH—body height; BM—body mass; LBM—lean body mass; FM—fat mass

References

- Buchheit, M.; Laursen, P.B. High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle: Part I: Cardiopulmonary emphasis. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastin, P.B. Quantification of anaerobic capacity. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 1994, 4, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözen, H. The effects of aerobic and anaerobic training on aerobic and anaerobic capacity. J. Int. Anatolia Sport Sci. 2018, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadefau, J.; Casademont, J.; Grau, J.M.; Fernandez, J.; Balaguer, A.; Vernet, M.; Urbano-Marquez, A. Biochemical and histochemical adaptation to sprint training in young athletes. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1990, 140, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, A.; Leveritt, M. Long-term metabolic and skeletal muscle adaptations to short-sprint training. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 1063–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgomaster, K.A.; Hughes, S.C.; Heigenhauser, G.J.; Bradwell, S.N.; Gibala, M.J. Six sessions of sprint interval training increases muscle oxidative potential and cycle endurance capacity in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 98, 1985–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgomaster, K.A.; Heigenhauser, G.J.; Gibala, M.J. Effect of short-term sprint interval training on human skeletal muscle carbohydrate metabolism during exercise and time-trial performance. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 100, 2041–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgomaster, K.A.; Cermak, N.M.; Phillips, S.M.; Benton, C.R.; Bonen, A.; Gibala, M.J. Divergent response of metabolite transport proteins in human skeletal muscle after sprint interval training and detraining. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007, 292, 1970–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, J.D.; Hicks, A.L.; MacDonald, J.R.; McKelvie, R.S.; Green, H.J.; Smith, K.M. Muscle performance and enzymatic adaptations to sprint interval training. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 84, 2138–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Farland, C.V.; Guidotti, F.; Harbin, M.; Roberts, B.; Schuette, J.; Porcari, J. The effects of high intensity interval training vs. steady state training on aerobic and anaerobic capacity. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2015, 14, 747–755. [Google Scholar]

- Gist, N.H.; Fedewa, M.V.; Dishman, R.K.; Cureton, K.J. Sprint Interval Training Effects on Aerobic Capacity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, S.J.; Wilkerson, D.P.; DiMenna, F.J.; Jones, A.M. Influence of repeated sprint training on pulmonary O2 uptake and muscle deoxygenation kinetics in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 106, 1875–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayati, M.; Farzad, B.; Gharakhanlou, R.; Agha-Alinejad, H. A practical model of low-volume high-intensity interval training induces performance and metabolic adaptations that resemble ‘all-out’sprint interval training. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2011, 10, 571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Trilk, J.L.; Singhal, A.; Bigelman, K.A.; Cureton, K.J. Effect of sprint interval training on circulatory function during exercise in sedentary, overweight/obese women. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babraj, J.A.; Vollaard, N.B.; Keast, C.; Guppy, F.M.; Cottrell, G.; Timmons, J.A. Extremely short duration high intensity interval training substantially improves insulin action in young healthy males. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2009, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naves, J.P.A.; Viana, R.B.; Rebelo, A.C.S.; De Lira, C.A.B.; Pimentel, G.D.; Lobo, P.C.B.; Gentil, P. Effects of high-intensity interval training vs. sprint interval training on anthropometric measures and cardiorespiratory fitness in healthy young women. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, N.; Trilk, J.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, M.; Cho, H.C. Effects of sprint interval training on elite Judoists. Int. J. Sports Med. 2011, 32, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblat, M.A.; Perrotta, A.S.; Thomas, S.G. Effect of high-intensity interval training versus sprint interval training on time-trial performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 1145–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneke, R. Methodological aspects of maximal lactate steady state—Implications for performance testing. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 89, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, E.F. Integration of the physiological factors determining endurance performance ability. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 1995, 23, 25–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahood, N.V.; Kenefick, R.W.; Kertzer, R.; Quinn, T.J. Physiological determinants of cross-country ski racing performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, K.; Beaver, W.L.; Whipp, B.J. Gas exchange theory and the lactic acidosis (anaerobic) threshold. Circulation 1990, 81, 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Maciejczyk, M.; Szymura, J.; Cempla, J.; Gradek, J.; Więcek, M.; Bawelski, M. Respiratory compensation point during incremental test in overweight and normoweight boys: Is it useful in assessing aerobic performance? A longitudinal study. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2014, 34, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciejczyk, M.; Wiecek, M.; Szymura, J.; Cempla, J.; Wiecha, S.; Szygula, Z.; Brown, L.E. Effect of body composition on respiratory compensation point during an incremental test. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 2071–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, T.; Faude, O.; Scharhag, J.; Urhausen, A.; Kindermann, W. Is lactic acidosis a cause of exercise induced hyperventilation at the respiratory compensation point? Br. J. Sports Med. 2004, 38, 622–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billat, L.V. Interval training for performance: A scientific and empirical practice: Special recommendations for middle-and long-distance running. Part I: Aerobic interval training. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haff, G.G.; Triplett, N.T. Essentials of strength training and conditioning. National Strength & Conditioning Association. Hum. Kinet. 2021, 60–61, 121. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson, J.; Reitman, J.S. Quantitative measures of enzyme activities in type I and type II muscle fibres of man after training. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1976, 97, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, E.; Hoppeler, H.; Claassen, H.; Billeter, R.; Aebi, U.; Horber, F.; Marti, B. Ultrastructural modification of human skeletal muscle tissue with 6-month moderate-intensity exercise training. Int. J. Sports Med. 1995, 16, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costill, D.L.; Fink, W.J.; Pollock, M.L. Muscle fiber composition and enzyme activities of elite distance runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1976, 8, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, G.A.; Abraham, W.M.; Terjung, R.L. Influence of exercise intensity and duration on biochemical adaptations in skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 1982, 53, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holloszy, J.O.; Booth, F.W. Biochemical adaptations to endurance exercise in muscle. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1976, 38, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klausen, K.; Andersen, L.B.; Pelle, I. Adaptive changes in work capacity, skeletal muscle capillarization and enzyme levels during training and detraining. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1981, 113, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schantz, P.G.; Sjöberg, B.; Svedenhag, J. Malate-aspartate and alpha-glycerophosphate shuttle enzyme levels in human skeletal muscle: Methodological considerations and effect of endurance training. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1986, 128, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, R.J.; Chi, M.; Hopkins, M. Mitochondrial enzymes increase in muscle in response to 7–10 days of cycle exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996, 80, 2250–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chromiak, J.A.; Mulvaney, D.R. A review: The effects of combined strength and endurance training on strength development. J. Strength Cond. Res. 1990, 4, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, M.H.; Roseguini, B. Mechanisms for exercise training-induced increases in skeletal muscle blood flow capacity: Differences with interval sprint training versus aerobic endurance training. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2008, 59, 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Franch, J.; Madsen, K.; Djurhuus, M.S.; Pedersen, P.K. Improved running economy following intensified training correlates with reduced ventilatory demands. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1998, 30, 1250–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaesser, G.A.; Poole, D.C.; Gardner, B.P. Dissociation between and ventilatory threshold responses to endurance training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1984, 53, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, E.S.; Jessup, G.T.; Wells, T.D.; Werthmann, D.A. Effects of various training intensity levels on anaerobic threshold and aerobic capacity in females. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 1983, 23, 315–318. [Google Scholar]

- Mier, C.M.; Turner, M.J.; Ehsani, A.A.; Spina, R.J. Cardiovascular adaptations to 10 days of cycle exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997, 83, 1900–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomqvist, C.G.; Saltin, B. Adaptations to physical training. Ann. Physiol. Rev. 1983, 4, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppeler, H.; Howald, H.; Conley, K.; Lindstedt, S.L.; Claassen, H.; Vock, P.; Weibel, E.R. Endurance training in humans: Aerobic capacity and structure of skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985, 59, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppeler, H. Exercise-induced ultrastructural changes in skeletal muscle. Int. J. Sports Med. 1986, 7, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhambhani, Y.; Singh, M. Ventilatory thresholds during a graded exercise test. Respiration 1985, 47, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, R.K.; Wonisch, M.; Corra, U.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Vanhees, L.; Saner, H. Methodological approach to the firstand second lactate threshold in incremental cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2008, 15, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, E.T.; Bassett, D.R.; Welch, H.G. Criteria for maximal oxygen uptake: Review and commentary. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1995, 27, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbar, O.; Bar-Or, O. Anaerobic characteristics in male children and adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1986, 18, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S.G.S.; Hale, T.; Hamley, E.J. A comparison of power outputs with rolling and stationary starts in the Wingate Anaerobic Test. J. Sports Sci. 1985, 3, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, S.N.; Haskell, W.L.; Ho, P.; Paffenbarger, R.S., Jr.; Vranizan, K.M.; Farquhar, J.W.; Wood, P.D. Assessment of habitual physical activity by a seven-day recall in a community survey and controlled experiments. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1985, 122, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkin, J.; Campbell, J.; Gross, L.; Roby, J.; Bazzo, S.; Sallis, J.; Calfas, K. Sevenday physical activity recall. Med. Sci. Sports Excerc. 1997, 29, 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Burgomaster, K.A.; Howarth, K.R.; Phillips, S.M. Similar metabolic adaptations during exercise after low volume sprint interval and traditional endurance training in humans. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra, J.; Cadefau, J.A.; Rodas, G.; Amigo, N.; Cusso, R. The distribution of rest periods affects performance and adaptations of energy metabolism induced by high-intensity training in human muscle. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2000, 169, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorstensson, A.; Sjödin, B.; Karlsson, J. Enzyme activities and muscle strength after “sprint training” in man. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1975, 94, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, D.S.; Ollis, S.; Young, J.D.; Thomas, N.E.; Cooper, S.M.; Tong, T.K.; Baker, J.S. The effects of time and intensity of exercise on novel and established markers of CVD in adolescent youth. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2011, 23, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M.; Mendez-Villanueva, A.; Quod, M.; Quesnel, T.; Ahmaidi, S. Improving acceleration and repeated sprint ability in well-trained adolescent handball players: Speed versus sprint interval training. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2010, 5, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzad, B.; Gharakhanlou, R.; Agha-Alinejad, H.; Curby, D.G.; Bayati, M.; Bahraminejad, M.; Mäestu, J. Physiological and performance changes from the addition of a sprint interval program to wrestling training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 2392–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaia, F.M.; Hellsten, Y.; Nielsen, J.J.; Fernström, M.; Sahlin, K.; Bangsbo, J. Four weeks of speed endurance training reduces energy expenditure during exercise and maintains muscle oxidative capacity despite a reduction in training volume. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 106, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, R.E.; Hazell, T.J.; Olver, T.D.; Paterson, D.H.; Lemon, P.W. Run sprint interval training improves aerobic performance but not maximal cardiac output. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, D.; Xie, H.; Ji, H.; Lu, J.; He, J.; Sun, J. Effects of sprint interval training on maximal oxygen uptake in athletes: A meta-analysis. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boullosa, D.; Dragutinovic, B.; Feuerbacher, J.F.; Benítez-Flores, S.; Coyle, E.F.; Schumann, M. Effects of short sprint interval training on aerobic and anaerobic indices: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2022, 32, 810–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, J.; Guan, D. Comparison of different interval training methods on athletes’ oxygen uptake: A systematic review with pairwise and network meta-analysis. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 17, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renwick, J.R.; Crukley, J.; Kudsi, M.; Binet, E.R.; Bone, J.; Mulkewich, N.J.; Gibala, M.J. Six Weeks of Low-Volume Sprint Interval Training Improves Peak Oxygen Uptake Compared to a Non-Exercise Control: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2025, 35, 70130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hov, H.; Wang, E.; Lim, Y.R.; Trane, G.; Hemmingsen, M.; Hoff, J.; Helgerud, J. Aerobic high-intensity intervals are superior to improve V̇O2max compared with sprint intervals in well-trained men. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 2023, 33, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Cai, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, B.; Yang, Y. Effects of 6-week sprint interval training compared to traditional training on the running performance of distance runners: A randomized controlled trail. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1536287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslankeser, Z.; Altinsoy, C. The effects of sprint interval training and detraining on aerobic fitness in young adults. Pensar Mov. 2024, 22, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazell, T.J.; MacPherson, R.E.; Gravelle, B.M.; Lemon, P.W. 10 or 30-s sprint interval training bouts enhance both aerobic and anaerobic performance. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 110, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.S.; McCormick, M.C.; Robergs, R.A. Interaction among skeletal muscle metabolic energy systems during intense exercise. J. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 1, 905612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloth, M.; Sloth, D.; Overgaard, K.; Dalgas, U. Effects of sprint interval training on VO 2max and aerobic exercise performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2013, 23, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boobis, L.; Williams, C.; Wootton, S.A. Human-muscle metabolism during brief maximal exercise. J. Physiol. 1983, 40, 10011–14211. [Google Scholar]

- Astorino, T.A.; Thum, J.S. Response: Commentary: Why sprint interval training is inappropriate for a largely sedentary population. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, S.J.; Ray, H.; Beale, L.; Hagger, M.S. Why sprint interval training is inappropriate for a largely sedentary population. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.