Thickness-Driven Structural Transition and Its Impact on Thermoelectric and Phonon Transport in Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Films

Abstract

1. Introduction

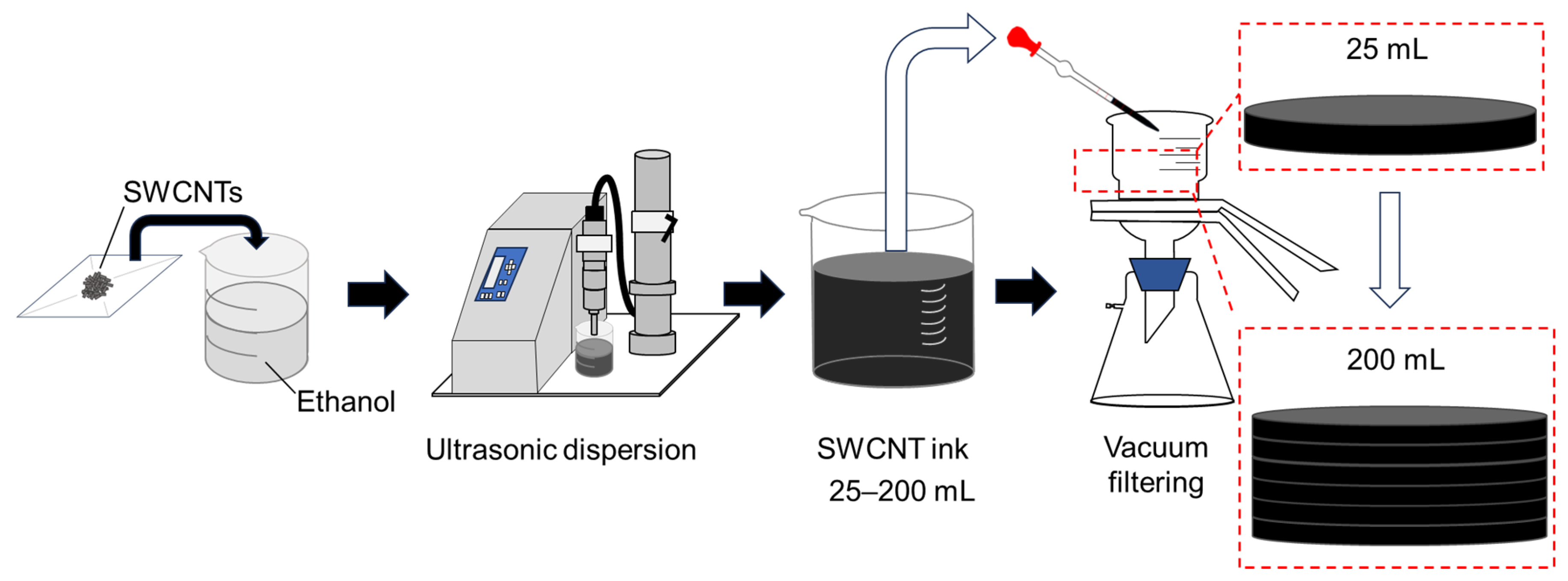

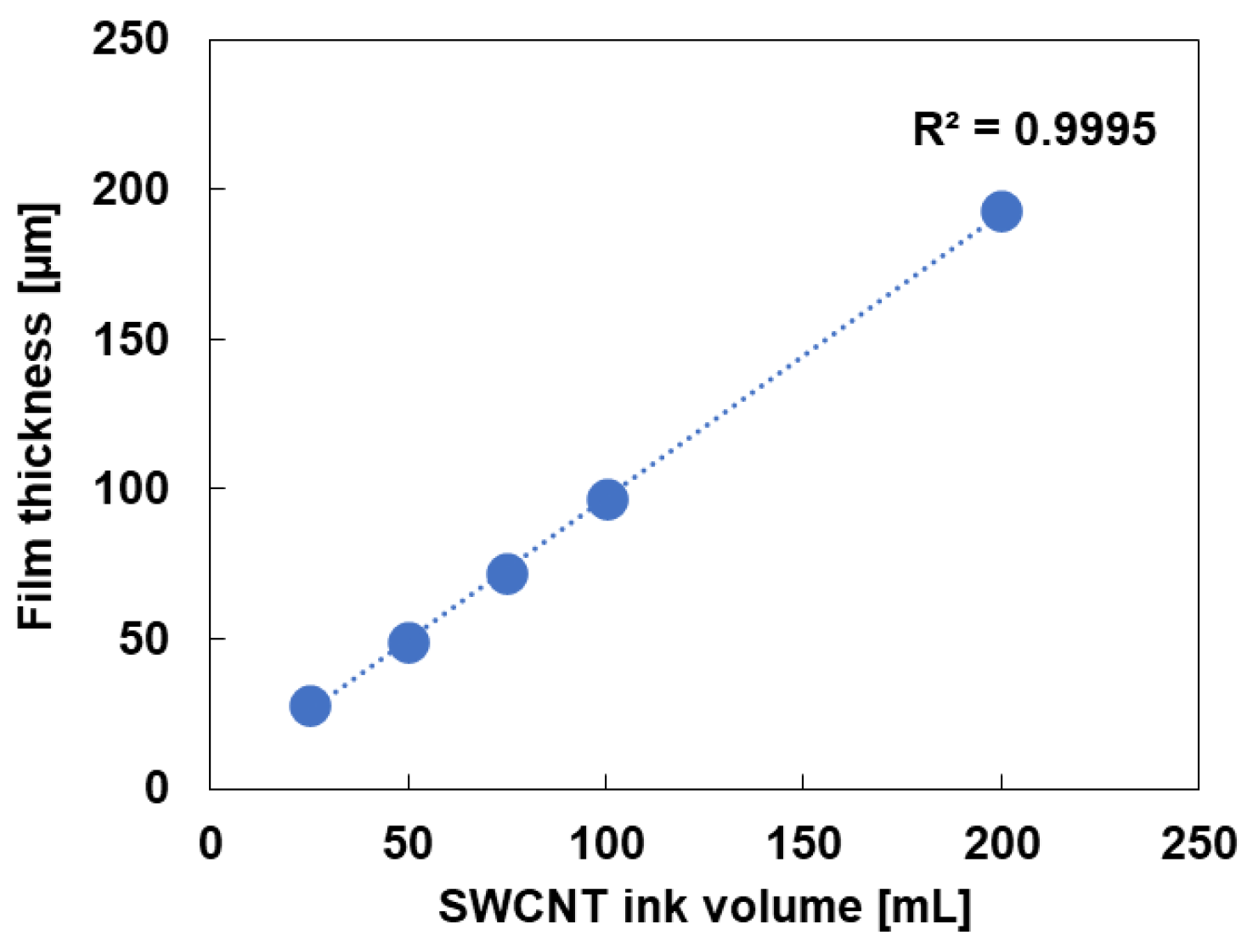

2. Materials and Methods

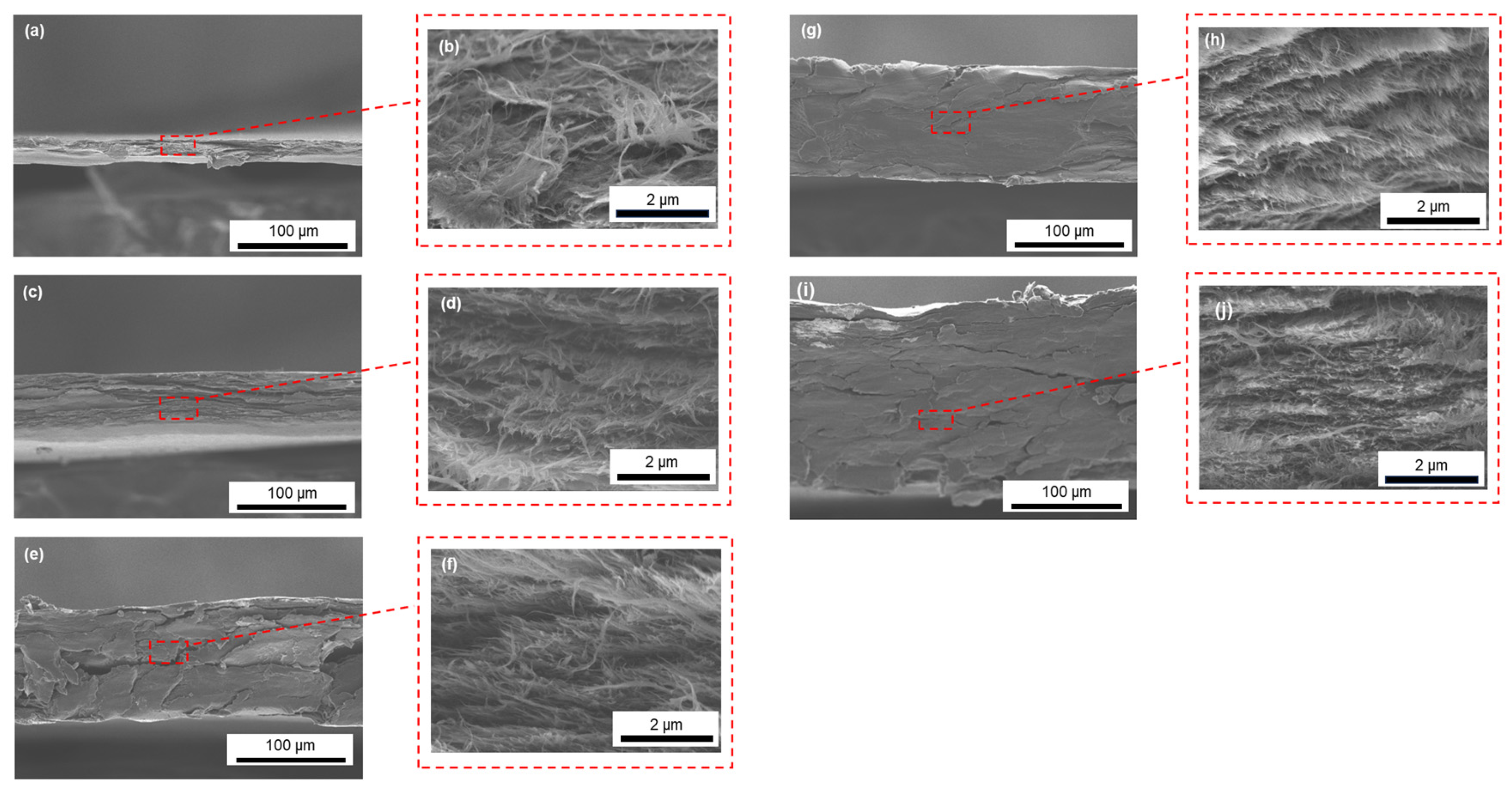

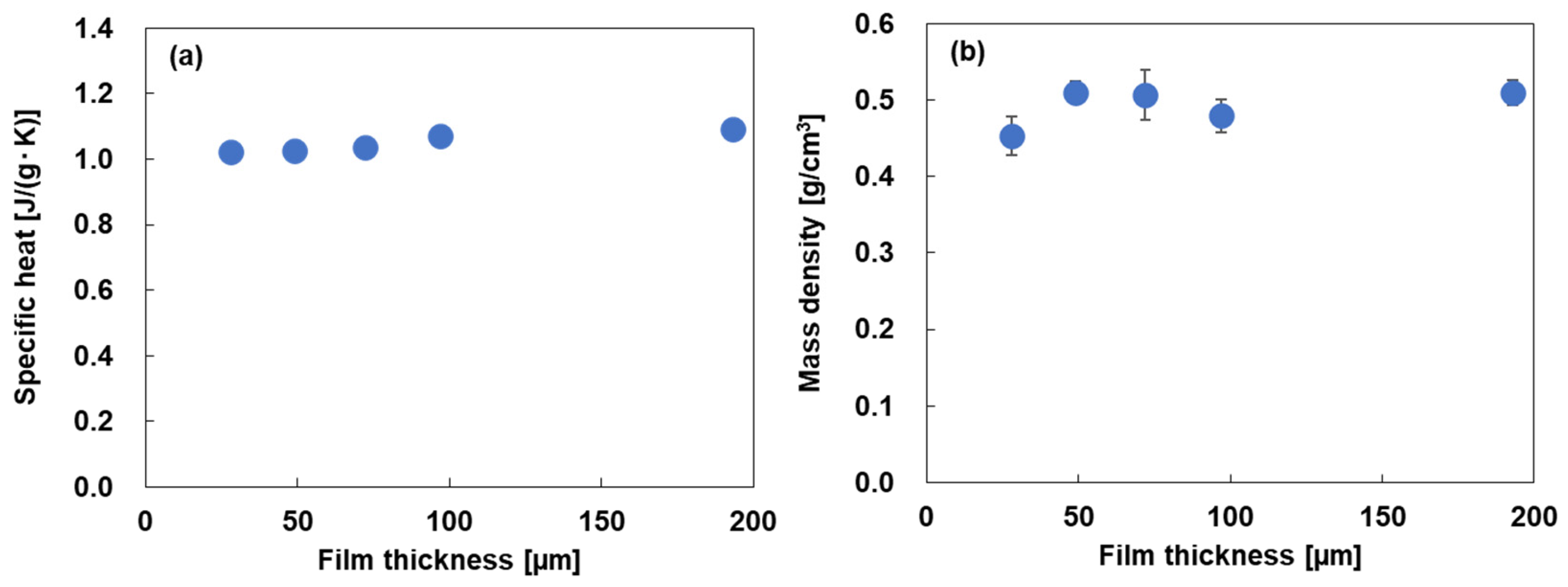

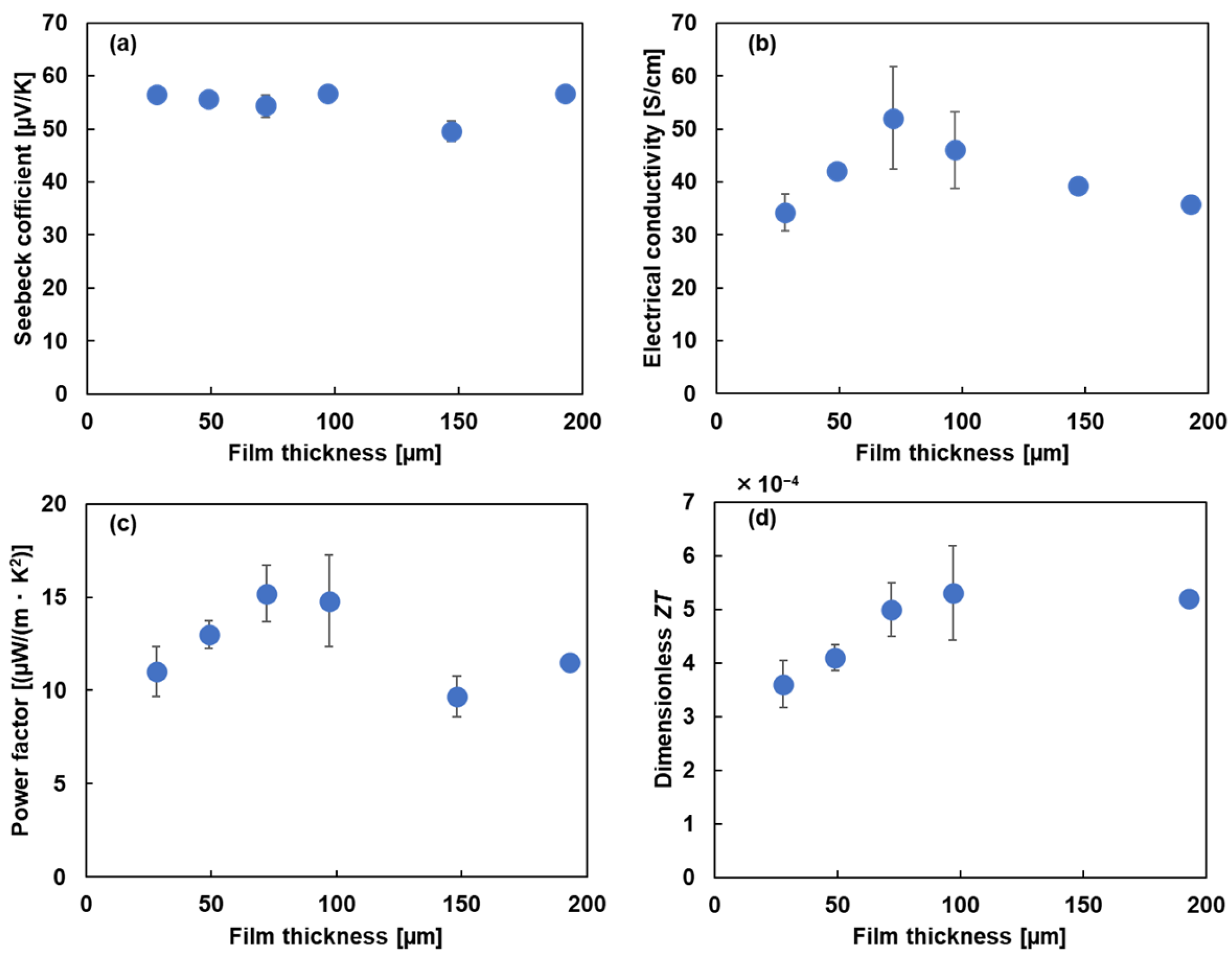

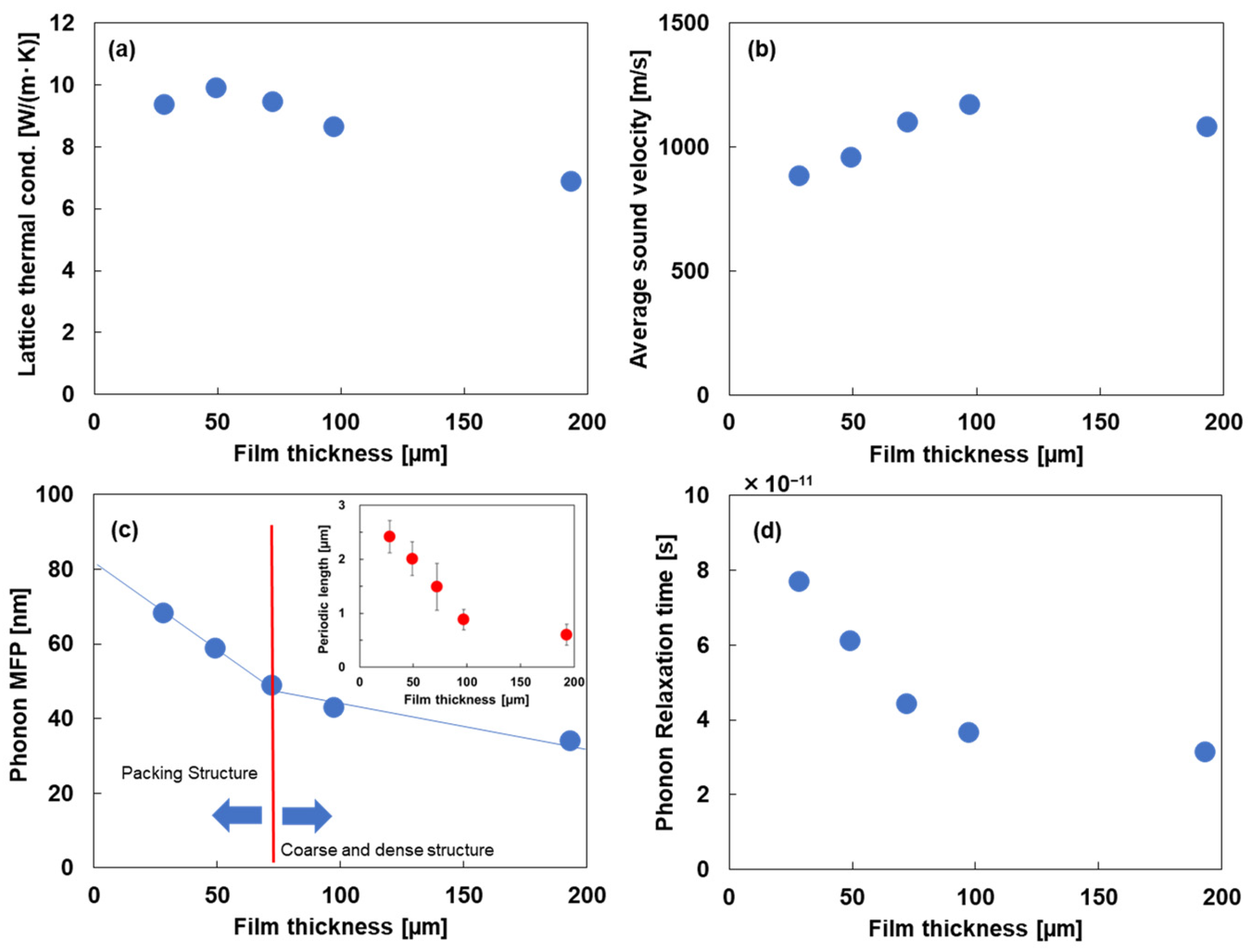

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iijima, S.; Ichihashi, T. Single-shell carbon nanotubes of 1-nm diameter. Nature 1993, 363, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolafi Rezaee, M.; Dahal, B.; Watt, J.; Abrar, M.; Hodges, D.R.; Li, W. Structural, electrical, and optical properties of single-walled carbon nanotubes synthesized through floating catalyst chemical vapor deposition. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yong, Z.; Li, Q. Continuous growth of carbon nanotube films: From controllable synthesis to real applications. Compos. Part A 2021, 144, 106359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zeng, S.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q. Fabrication and functionalization of carbon nanotube films for high-performance flexible supercapacitors. Carbon 2015, 92, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Xu, J.; Xiu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Hess, D.W.; Wong, C.P. Growth and electrical characterization of high-aspect-ratio carbon nanotube arrays. Carbon 2006, 44, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arash, B.; Wang, Q.; Varadan, V.K. Mechanical properties of carbon nanotube/polymer composites. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, D.; Heo, S.J.; Jang, D.; Kang, B.-C.; Kim, S.G.; Chae, H.G.; Kim, J.Y.; Ku, B.-C.; Kim, H. Thermal coalescence-driven structural transformation of carbon nanotube fibers for flexible thermoelectrics. Chem. Eng. J. 2026, 527, 171739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Pal, P.; Ghosh, N.K. Enhancing the thermal conductivity and viscosity of ethylene glycol-based single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT) nanofluid: An investigation utilizing equilibrium molecular dynamics simulation. Chem. Thermodyn. Therm. Anal. 2024, 16, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Sekiguchi, A.; Kobashi, K.; Sundaram, R.; Yamada, T.; Hata, K. Mechanically robust free-standing single-walled carbon nanotube thin films with uniform mesh-structure by blade coating. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 562455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasibulin, A.G.; Kaskela, A.; Mustonen, K.; Anisimov, S.A.; Ruiz, V.; Kivistö, S.; Rackauskas, S.; Timmermans, M.Y.; Pudas, M.; Aitchison, B.; et al. Multifunctional free-standing single-walled carbon nanotube films. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 3214–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, T.W.; Huang, J.L.; Kim, P.; Lieber, C.M. Structure and electronic properties of carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 2794–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.N.R.; Voggu, R.; Govindaraj, A. Selective generation of single-walled carbon nanotubes with metallic, semiconducting and other unique electronic properties. Nanoscale 2009, 1, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battie, Y.; Ducloux, O.; Thobois, P.; Dorval, N.; Lauret, J.S.; Attal-Trétout, B.; Loiseau, A. Gas sensors based on thick films of semi-conducting single-walled carbon nanotubes. Carbon 2011, 49, 3544–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, N.; Ma, Y.; Du, F.; Li, F.; He, X.; Lin, X.; Gao, H.; Chen, Y. The influence of single-walled carbon nanotube structure on the electromagnetic interference shielding efficiency of its epoxy composites. Carbon 2007, 45, 1614–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhang, M. Carbon nanotubes for thin film transistor: Fabrication, properties, and applications. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013, 627215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Wang, B.W.; Hou, P.X.; Li, J.C.; Zhang, F.; Luan, J.; Cong, H.T.; Liu, C.; Cheng, H.M. Selective growth of semiconducting single-wall carbon nanotubes using SiC as a catalyst. Carbon 2018, 135, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Sui, Q.; Wen, H.; Cao, L.; Cao, P.; Kang, L.; Tang, J.; Jin, H.; et al. Rapid annealing and cooling induced surface cleaning of semiconducting carbon nanotubes for high-performance thin-film transistors. Carbon 2021, 184, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.C.T.; Murugan, B.; Siah, C.F.; Lim, Y.K. Beyond silicon frontiers in neuromorphic computing and logic circuits: Single-walled carbon nanotube thin-film transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 70404–70428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia-Espino, E.; Sala, G.; Pino, F.; Halonen, N.; Luomahaara, J.; Mäklin, J.; Tóth, G.; Kordás, K.; Jantunen, H.; Terrones, M.; et al. Electrical transport and field-effect transistors using inkjet-printed SWCNT films having different functional side groups. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3318–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.Y.; Hou, P.X.; Zhang, F.; Liu, C.; Cheng, H.M. Gas sensors based on single-wall carbon nanotubes. Molecules 2022, 27, 5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaderi, A.I.J.; Ramakrishnan, N. Carbon-based flexible strain sensors: Recent advances and performance insights in human motion detection. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 513, 162609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulianti, R.T.; Irmawati, Y.; Destyorini, F.; Ghozali, M.; Suhandi, A.; Kartolo, S.; Hardiansyah, A.; Byun, J.H.; Fauzi, M.H.; Yudianti, R. Highly stretchable and sensitive single-walled carbon nanotube-based sensor decorated on a polyether ester urethane substrate by a low hydrothermal process. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 34866–34875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, M.; So, H. Negative temperature coefficient effect of TPU/SWCNT/PEDOT:PSS polymer matrices for wearable temperature sensors. Polym. Test. 2024, 141, 108652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Horii, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Son, K.; Hosoya, N.; Maeda, S.; Fujie, T. Ultraconformable capacitive strain sensor utilizing network structure of single-walled carbon nanotubes for wireless body sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 10420–10438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, M.H.; Bae, E.J.; Park, B.; Ha, J.W.; Han, M.; Kang, Y.H. High-performance and flexible thermoelectric generator based on a robust carbon nanotube/BiSbTe foam. Carbon Energy 2024, 7, e650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erden, F.; Danaci, I.; Ozbay, S. Flexible thermoelectric generators based on single-walled carbon Nanotube/Poly(aniline-co-acrylonitrile) composites. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2025, 11, 2500026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konagaya, R.; Takashiri, M. Dual-Type Flexible-film thermoelectric generators using all-carbon nanotube films. Coatings 2023, 13, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, T.; Amma, Y.; Takashiri, M. Heat source free water floating carbon nanotube thermoelectric generators. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shang, H.; Zou, Q.; Feng, C.; Gu, H.; Ding, F. n-type PVP/SWCNT composite films with improved stability for thermoelectric power generation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 6025–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, W.-D.; Lyu, W.; Yin, L.-C.; Yue, Y.; Gao, H.; Li, M.; Shi, X.-L.; Liu, Q.; Wang, N.; et al. Alignment of edge dislocations—The reason lying behind composition inhomogeneity induced low thermal conductivity. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, R.; Mayuzumi, Y.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kobayashi, A.; Seki, Y.; Takashiri, M. Improved thermoelectric properties of solvothermally synthesized Bi2Te3 nanoplate films with homogeneous interconnections using Bi2Te3 electrodeposited layers. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 818, 152901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Hatasako, Y.; Uchino, M.; Nakata, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Hayakawa, T.; Adachi, C.; Miyazaki, K. Flexible porous bismuth telluride thin films with enhanced figure of merit using micro-phase separation of block copolymer. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 1, 1300015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Shi, L.; Yao, Z.; Li, D.; Majumdar, A. Thermal conductance and thermopower of an individual single-wall carbon nanotube. Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 1842–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Wang, G.; Wolan, B.F.; Wu, N.; Wang, C.; Zhao, S.; Yue, B.; Li, B.; He, W.; Liu, J.; et al. Printable aligned single-walled carbon nanotube film with outstanding thermal conductivity and electromagnetic interference shielding performance. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.-T.; Tai, N.-H. Investigations on the thermal conductivity of composites reinforced with carbon nanotubes. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2008, 17, 1577–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiga, T.; Terada, Y.; Chiashi, S.; Kodama, T. Effect of bundling on phonon transport in single-walled carbon nanotubes. Carbon 2024, 223, 119048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.; Chen, Y.W.; Shi, Q.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Mo, R.W.; Wang, J.N. Highly aligned and densified carbon nanotube films with superior thermal conductivity and mechanical strength. Carbon 2022, 186, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamasaki, H.; Takimoto, S.; Hirahara, K. Visualization of thermal transport within and between carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 3134–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.; Dutta, M.; Sarkar, D.; Biswas, K. Insights into low thermal conductivity in inorganic materials for thermoelectrics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 10099–10118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundle, J.; Leoni, S. Layered tin chalcogenides SnS and SnSe: Lattice thermal conductivity benchmarks and thermoelectric figure of merit. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 14036–14046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Tan, G.; Luo, Y.; Su, X.; Yan, Y.; Tang, X. Thermal stability of p-type BiSbTe alloys prepared by melt spinning and rapid sintering. Materials 2017, 10, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Park, D.; Kim, J. A review on recent selenium- and tellurium-based thermoelectric materials and chalcogenide/organic flexible thermoelectric applications. Mater. Diamond Relat. Mater. 2008, 17, 1577–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, K.; Karttunen, A.J. Bridging the junction: Electrical conductivity of carbon nanotube networks. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 17266–17274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilatovskii, D.A.; Gilshtein, E.P.; Glukhova, O.E.; Nasibulin, A.G. Transparent conducting films based on carbon nanotubes: Rational design toward the theoretical limit. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2201673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Shearer, C.; Shapter, J. Recent development of carbon nanotube transparent conductive films. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 13413–13453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkov, A.N.; Zhigilei, L.V. Effects of material density and structural anisotropy on thermal transport in carbon nanotube materials. Carbon 2025, 243, 120393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

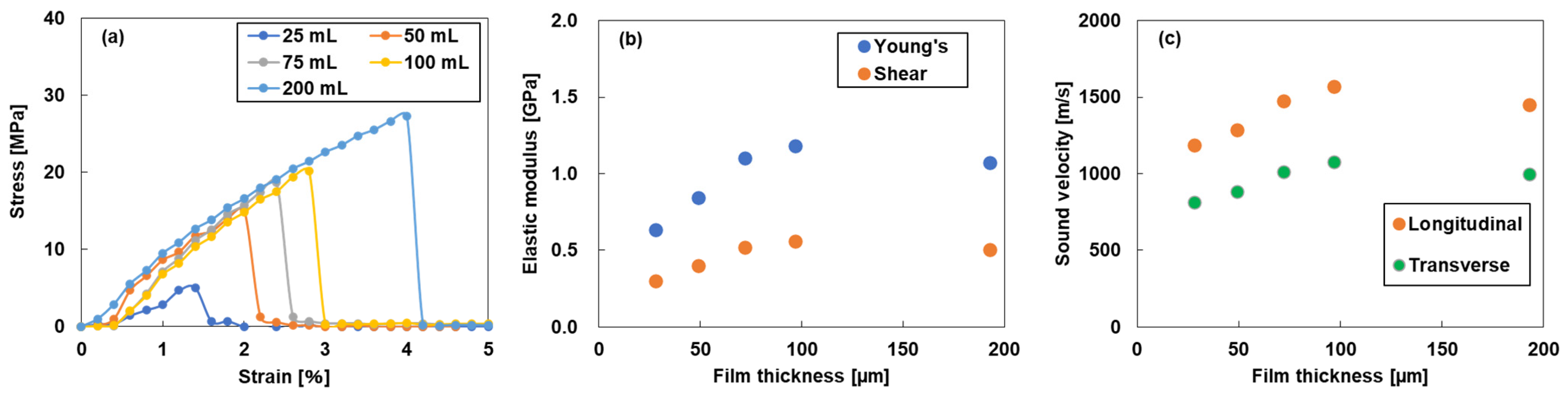

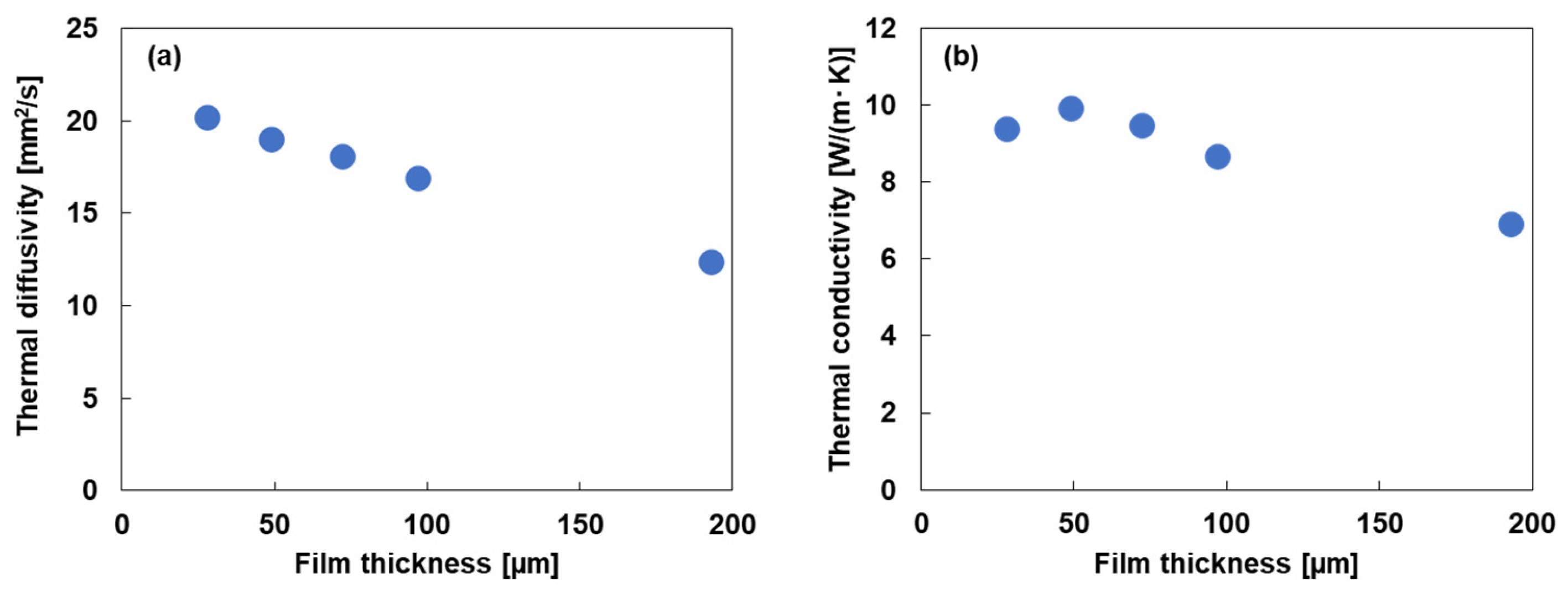

- Yamamoto, H.; Okano, Y.; Uchida, K.; Kageshima, M.; Kuzumaki, T.; Miyake, S.; Takashiri, M. Phonon transports in single-walled carbon nanotube films with different structures determined by tensile tests and thermal conductivity measurements. Carbon Trends 2024, 17, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, S.; Shinozaki, Y.; Eguchi, A.; Nagai, K.; Miyake, S.; Takashiri, M. Evaluation of thermal transport in composite SWCNT films with pseudo-heterogeneous interfaces obtained by blending different SWCNTs. Diamond Relat. Mater. 2025, 159, 112925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanisawa, D.; Shionozaki, Y.; Takizawa, T.; Yamaguchi, A.; Murotani, H.; Takashiri, M. Ultralow thermal conductivity of amorphous silicon–germanium thin films for alloy and disorder scattering determined by 3ω method and nanoindentation. Appl. Phys. Express 2024, 17, 011005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norimasa, O.; Hase, M.; Hayamizu, M.; Nagata, S.; Tanaka, S.; Miyake, S.; Nishi, T.; Murotani, H.; Takashiri, M. Phonon transport properties depending on crystal orientation analyzed by nanoindentation using single-crystal silicon wafers. Appl. Phys. Express 2021, 14, 126502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norimasa, O.; Chiba, T.; Hase, M.; Komori, T.; Takashiri, M. Improvement of thermoelectric properties of flexible Bi2Te3 thin films in bent states during sputtering deposition and post-thermal annealing. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 898, 162889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, T.S.L.; Gibson, C.T.; Gascooke, J.R.; Shapter, J.G. The use of gravity filtration of carbon nanotubes from suspension to produce films with low roughness for carbon nanotube/silicon heterojunction solar device application. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafii-Tabar, H. Computational Physics of Carbon Nanotubes; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 135–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, L.J.; Coluci, V.R.; Galvão, D.S.; Kozlov, M.E.; Zhang, M.; Dantas, S.O.; Baughman, R.H. Sign change of Poisson’s ratio for carbon nanotube sheets. Science 2008, 320, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, N.; Yang, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P. Synergistically enhancing dispersibility and thermoelectric performance of carbon nanotubes by biomass carboxymethyl cellulose. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 17759–17768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putatunda, A.; Singh, D.J. Lorenz number in relation to estimates based on the Seebeck coefficient. Mater. Today Phys. 2019, 8, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Gibbs, Z.M.; Tang, Y.; Wang, H.; Snyder, G.J. Characterization of Lorenz number with Seebeck coefficient measurement. APL Mater. 2015, 3, 041506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, T.; Mori, R.; Norimasa, O.; Chiba, T.; Eguchi, R.; Takashiri, M. Influences of substrate types and heat treatment conditions on structural and thermoelectric properties of nanocrystalline Bi2Te3 thin films formed by DC magnetron sputtering. Vacuum 2020, 179, 109535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasher, R.S.; Hu, X.J.; Chalopin, Y.; Mingo, N.; Lofgreen, K.; Volz, S.; Cleri, F.; Keblinski, P. Turning carbon nanotubes from exceptional heat conductors into insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 105901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reihani, A.; Soleimani, A.; Kargar, S.; Sundararaghavan, V.; Ramazani, A. Graphyne nanotubes: Materials with ultralow phonon mean free path and strong optical phonon scattering for thermoelectric applications. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 7277–7288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, A.; Rodriguez, A.; Zhang, X.; Comstock, A.H.; Yang, C.; Sun, D.; Jiang, X.; Kumah, D.; Hu, M.; Liu, J. Thickness-dependent thermal conductivity and phonon mean free path distribution in single-crystalline barium titanate. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2301273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-M.; Shrestha, R.; Dangol, A.; Chang, W.S. Dependence of thermal conductivity on thickness in single-walled carbon nanotube films. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2016, 16, 1028–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nakazawa, Y.; Shinozaki, Y.; Uchida, K.; Ochiai, S.; Miyake, S.; Takashiri, M. Thickness-Driven Structural Transition and Its Impact on Thermoelectric and Phonon Transport in Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Films. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031377

Nakazawa Y, Shinozaki Y, Uchida K, Ochiai S, Miyake S, Takashiri M. Thickness-Driven Structural Transition and Its Impact on Thermoelectric and Phonon Transport in Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Films. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031377

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakazawa, Yuto, Yoshiyuki Shinozaki, Keisuke Uchida, Shuya Ochiai, Shugo Miyake, and Masayuki Takashiri. 2026. "Thickness-Driven Structural Transition and Its Impact on Thermoelectric and Phonon Transport in Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Films" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031377

APA StyleNakazawa, Y., Shinozaki, Y., Uchida, K., Ochiai, S., Miyake, S., & Takashiri, M. (2026). Thickness-Driven Structural Transition and Its Impact on Thermoelectric and Phonon Transport in Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Films. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031377