Abstract

Accurate gas analysis plays a critical role in aerospace missions, including spacecraft safety assurance, crew health monitoring, and deep-space scientific exploration. Although conventional gas chromatography (GC) techniques are well established, their large size, high power consumption, and long analysis time limit their applicability in modern aerospace missions that require miniaturized, low-power, and highly integrated analytical systems. The development of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) technology provides an effective pathway for the miniaturization of gas chromatography. MEMS-based micro gas chromatography columns enable the integration of meter-scale separation channels onto centimeter-scale chips through micro- and nanofabrication techniques, significantly reducing system volume and power consumption while improving analysis speed and integration capability. Compared with conventional GC systems, MEMS µGC exhibits clear advantages in size, weight, energy efficiency, and response time. This review systematically summarizes the fundamentals, structural designs, fabrication processes, and stationary phase preparation of MEMS micro gas chromatography columns. Representative aerospace application cases along with related experimental and engineering validation studies are highlighted; we re-evaluate these systems using Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) to distinguish flight heritage from concept demonstrations and propose a standardized validation roadmap for environmental reliability. In addition, key technical challenges for aerospace deployment are discussed. This work aims to provide a useful reference for the development of aerospace gas analysis systems and the engineering application of MEMS-based technologies.

1. Introduction

In aerospace missions, the precise monitoring and analysis of gas composition serve as a critical technical pillar for ensuring mission safety, realizing scientific objectives, and maintaining stable system operations. Whether for intra-vehicular environment monitoring in manned spaceflight or for planetary atmospheric analysis and volatile organic compound (VOC) detection in deep space exploration, gas analysis systems play a pivotal role [1,2]. Aerospace missions are typically characterized by long operating cycles, constrained resources, and extreme environmental conditions, which impose stringent requirements on the reliability, power consumption, volume, and autonomous operation capabilities of gas analysis instruments.

In manned space missions, real-time monitoring of cabin gas composition is of paramount importance for safeguarding astronaut health and ensuring the safe operation of the spacecraft. An imbalance in oxygen and carbon dioxide concentrations, or the leakage of VOCs or toxic gases (such as ammonia and formaldehyde), can pose severe threats to personnel safety and equipment reliability. Conversely, in deep space exploration missions, gas analysis systems are utilized to investigate planetary atmospheric compositions, detect organic molecules, and support the scientific search for potential biosignatures. These diverse mission scenarios impose a set of common requirements on gas analysis technology: the ability to achieve high sensitivity, high selectivity, and long-term stable operation under strictly limited mass, volume, and energy budgets.

Historically, the International Space Station (ISS) and early space missions primarily relied on traditional gas chromatography (GC) systems for gas composition analysis. Although traditional GC technology exhibits maturity in terms of separation accuracy and analytical reliability, it presents significant limitations in aerospace applications, such as large system volume, high power consumption, long analysis cycles, and substantial carrier gas consumption [3]. These drawbacks not only occupy valuable cabin space and energy resources but also increase the complexity of system maintenance and logistical resupply. To provide a more intuitive illustration of the differences between traditional GC and MEMS micro gas chromatography in key performance metrics, Table 1 presents a quantitative comparison of the two technical routes. As shown in Table 1, MEMS micro gas chromatography offers orders-of-magnitude advantages over traditional GC in terms of system volume, power consumption, and analysis time. Although its separation efficiency is generally lower than that of laboratory-grade GC, its performance is adequate to meet the practical demands of mission-driven applications such as aerospace environmental monitoring and rapid on-site analysis. As aerospace missions evolve toward long-term habitation and deep space exploration, the adaptability of traditional GC systems faces increasing challenges regarding extreme temperatures, extended operation times, and high autonomy requirements. Consequently, the development path of traditional GC is becoming increasingly contradictory to the general aerospace trend of “lightweight, low power, and high integration.”

Table 1.

Comparison of Key Performance Indicators between Traditional Gas Chromatography and MEMS Micro Gas Chromatography.

The development of Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) technology has provided novel solutions for the miniaturization and high integration of aerospace gas analysis instruments. MEMS µGC columns based on MEMS technology can be fabricated using processes such as Deep Reactive Ion Etching (DRIE) and laser micromachining to integrate chromatographic channels spanning several meters onto a chip scale of merely a few square centimeters. This allows for a simultaneous reduction in power consumption and analysis time while significantly decreasing system volume and mass [4,5,6]. Compared to traditional GC systems, MEMS µGC technology demonstrates distinct advantages in terms of size, weight, and power (SWaP), response speed, and system integration potential, making it a promising candidate for next-generation gas analysis technology in the aerospace sector.

Therefore, MEMS µGC technology represents not merely a miniaturized alternative to traditional GC, but a significant trend toward highly integrated, low-resource-consuming, and autonomous gas analysis systems. With the advancement of future space station construction and lunar and Martian exploration missions, the demand for high-performance, miniaturized gas analysis instruments will continue to grow. MEMS technology is expected to play a key role in various application scenarios, including aerospace environmental monitoring, planetary scientific research, and mission safety assurance.

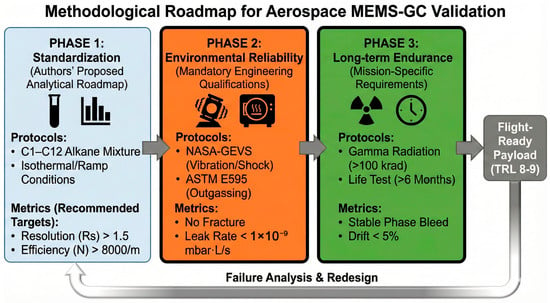

Based on the growing demand for gas analysis technology in the aerospace field, this article systematically reviews the research progress regarding the theoretical foundations, structural design, fabrication processes, and stationary phase preparation of MEMS µGC columns. Furthermore, it focuses on typical application cases in the aerospace sector, relevant experimental and engineering validation studies, and analyzes the critical scientific and engineering challenges that remain to be addressed. Unlike previous reviews that primarily catalog fabrication techniques or focus broadly on µGC applications, in addition to summarizing recent literature, this review aims to provide deeper critical analysis and engineering insights through three specific methodological improvements:

- Quantitative Comparison of Fabrication Processes: We provide a quantitative benchmarking of stationary phase preparation methods, comparing coating techniques with Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) using engineering metrics such as interfacial bond energy and thermal stability limits, rather than relying solely on qualitative descriptions.

- Engineering Readiness Assessment: We re-evaluate existing MEMS-GC systems based on Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) and analyze their adaptability to specific space environments (e.g., vacuum, radiation), highlighting the gap between laboratory prototypes and flight-proven payloads.

- Proposed Validation Workflow: To address the lack of standardized testing, we propose a structured validation roadmap that outlines specific acceptance criteria for environmental reliability and long-term endurance, providing a reference for future engineering development.

Through this review, we aim to provide a systematic reference and guide for the research and development of aerospace gas analysis systems and the engineering application of MEMS technology

To ensure a comprehensive and systematic analysis of the current status of MEMS micro gas chromatography technology for aerospace applications, this paper conducted a structured literature review. The literature search was primarily conducted through major scientific databases, including Web of Science, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and Google Scholar, covering the time span from January 2000 to December 2024.

The search strategy employed combinations of keywords related to the technology and its application fields: (“MEMS gas chromatography” OR “micro GC” OR “µGC” OR “micro column”) AND (“aerospace” OR “spaceflight” OR “space station” OR “planetary exploration” OR “vacuum” OR “microgravity”).

The inclusion criteria were defined as follows: (1) peer-reviewed journal papers, conference proceedings, and patents; (2) studies focusing on the fabrication, testing, or integration of MEMS µGC columns; and (3) studies providing quantitative performance metrics (e.g., separation efficiency, power consumption) or engineering validation data relevant to the space environment. Irrelevant studies lacking specific experimental data or purely theoretical works without an application context were excluded. Ultimately, approximately 96 key references were selected as the basis for this review to ensure both the breadth of technical coverage and the depth of aerospace engineering relevance.

2. Theoretical Foundations and Relevant Calculation Formulas

2.1. Theoretical Foundations

The design and optimization of MEMS µGC columns rely heavily on the guidance of chromatographic separation theory. Early chromatographic theories have provided essential theoretical support for the development of MEMS µGC columns, particularly Plate theory and Rate theory, which explain the critical factors in the separation process from the perspectives of thermodynamics and kinetics. Furthermore, the Golay equation has provided the theoretical basis for the design of columns with rectangular channels, further driving the innovative development of MEMS µGC columns.

2.1.1. Plate Theory

Plate Theory is one of the fundamental theories of chromatographic separation, first proposed by Martin and Synge in 1941 [7]. This theory conceptualizes the chromatography column as a distillation column composed of numerous theoretical plates, where each plate represents an equilibrium stage. Within the column, the separation process of a component can be viewed as the result of its repeated distribution between these plates [8,9,10]. Plate Theory quantifies the separation efficiency of a chromatography column via the number of theoretical plates (n) and the height equivalent to a theoretical plate (H), whose relationship is given by the equation:

where L represents the length of the chromatographic column, and H represents the height equivalent to a theoretical plate. A larger number of theoretical plates (n), or a smaller height equivalent to a theoretical plate (H), indicates higher separation efficiency of the column. Plate Theory provides a qualitative description of the chromatographic separation process from a thermodynamic perspective. However, as it fails to account for the influence of kinetic factors on separation efficiency, it cannot fully explain the actual performance of chromatographic columns [11,12].

2.1.2. Rate Theory

Rate Theory, proposed by Van Deemter et al. in 1956 [13], addresses the limitations of Plate Theory. It analyzes the various factors affecting the height equivalent to a theoretical plate during the chromatographic separation process from a kinetic perspective. Its core equation is as follows:

where is the linear velocity of the mobile phase. The terms A, B, and C represent the eddy diffusion term, molecular diffusion term, and resistance to mass transfer term, respectively. Specifically, the A term describes the peak broadening caused by solute molecules traveling paths of different lengths through a packed column, a phenomenon known as “eddy” diffusion, which becomes more pronounced with larger particle sizes of the packing material. The B term relates to longitudinal diffusion, referring to the natural spreading of solute molecules along the column axis, which also contributes to peak broadening. The C term involves the resistance to mass transfer of solute molecules between the stationary and mobile phases; greater resistance to mass transfer leads to more severe peak broadening.

The van Deemter equation comprehensively describes the complex kinetic factors affecting the height equivalent to a theoretical plate (H) during chromatographic separation, revealing the relationship between H and the linear velocity of the carrier gas. Specifically, the longitudinal diffusion term (B term) decreases as the carrier gas linear velocity increases, whereas the resistance to mass transfer term (C term) increases with rising carrier gas linear velocity. Consequently, the effect of carrier gas linear velocity on column efficiency is nonlinear.

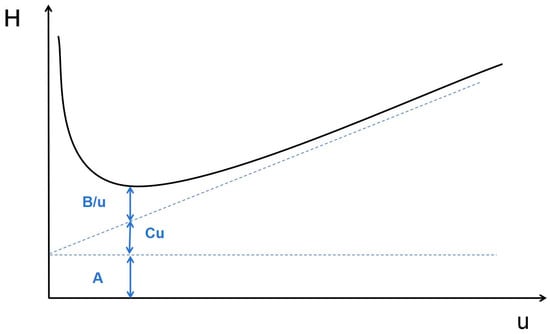

For a given chromatographic column, the values of A, B, and C in the van Deemter equation are fixed. Therefore, there exists an optimal linear velocity of the carrier gas that minimizes the height equivalent to a theoretical plate, thereby maximizing column efficiency. This relationship can be visually represented by the van Deemter curve, as shown in Figure 1. The curve clearly demonstrates that the effect of carrier gas linear velocity on column efficiency is nonlinear, with a specific optimal value at which the height equivalent to a theoretical plate is minimized, and column efficiency is maximized.

Figure 1.

Van Deemter curve.

2.1.3. Golay Equation

The Golay equation is a pivotal theoretical model describing the separation efficiency of open tubular chromatography columns, introduced by Golay in 1958 [14]. This equation analyzes the mass transfer process in rectangular channel columns from a kinetic perspective. Its expression is given by:

where is the height equivalent to a theoretical plate, is the average carrier gas velocity, is the retention factor, is the thickness of the stationary phase film, and are the diffusion coefficients of the solute in the carrier gas and stationary phase, respectively, and and are the width and depth of the rectangular channel, respectively.

From the Golay equation, it can be further deduced that a greater channel depth and a smaller channel width result in a smaller height equivalent to a theoretical plate, a higher number of theoretical plates, and consequently, better separation efficiency of the chromatographic column. This high-aspect-ratio design not only ensures sufficient gas capacity of the column but also effectively promotes the rapid distribution of gas molecules between the two phases in the mobile phase, thereby significantly enhancing the separation efficiency. However, fabricating channels with excessively high aspect ratios is prone to surface roughness and residual stress, while existing micro-nanofabrication techniques struggle to achieve precise control over excessively high aspect ratios, as errors can easily occur during photolithography and etching processes, leading to deviations in channel dimensions and shape that affect the performance and structural stability of the chromatographic column.

2.2. Applicability and Limitations of Classical Gas Chromatography Theory

Classical gas chromatography theory provides a fundamental framework for understanding mass transfer and diffusion behaviors during the separation process; consequently, it is frequently utilized for the conceptual design and performance analysis of MEMS µGC columns. However, these theoretical models were originally established based on macro-scale dimensions, ideal geometries, and steady-state operating conditions. As a result, several of their underlying assumptions often fail to hold strictly under the specific conditions of MEMS micro-scales and micro-nanofabrication.

Regarding channel geometry, classical theory typically assumes columns with axisymmetric, smooth, and uniform circular cross-sections. In contrast, MEMS µGC columns predominantly employ rectangular, trapezoidal, or complex modified microchannel structures. The sharp corners, surface roughness, and dimensional deviations introduced during microfabrication processes can lead to significant non-uniformity in the carrier gas velocity distribution, thereby undermining the assumptions regarding ideal flow and equivalent mass transfer paths inherent in Plate theory and the van Deemter model. Under these circumstances, theoretical plate numbers and optimal operating parameters derived from ideal models often serve merely as trend indicators rather than precise predictors.

To enhance separation efficiency, sample capacity, or selectivity, many MEMS µGC columns incorporate semi-packed structures, micro-pillar arrays, or high-surface-area coatings within the microchannels. Such structures significantly alter local flow fields and mass transfer characteristics, rendering the simplified mass transfer descriptions for open-tubular columns in the Golay equation less applicable. Simultaneously, increased structural complexity is typically accompanied by higher pressure drops and enhanced flow disturbances—factors not systematically accounted for in classical theory.

Furthermore, constrained by chip footprint and power consumption, MEMS µGC columns generally feature shorter lengths and often employ rapid temperature programming and non-steady-state operating modes to meet the demands of rapid detection. In such scenarios, the impacts of thermal gradients, transient mass transfer, and system-level coupling effects on separation performance become more pronounced. Since classical GC theory is primarily established on steady-state conditions, it exhibits certain limitations in describing these dynamic factors.

In summary, within the research and application of MEMS µGC columns, Plate theory, the van Deemter equation, and the Golay equation are better utilized as guiding tools for qualitative analysis and engineering design rather than as rigorous quantitative prediction models. Current research increasingly tends to combine classical theory with numerical simulation, experimental characterization, and system-level performance assessment to more accurately characterize actual separation behaviors under non-ideal microchannel conditions.

3. Structural Layout of MEMS µGC Columns

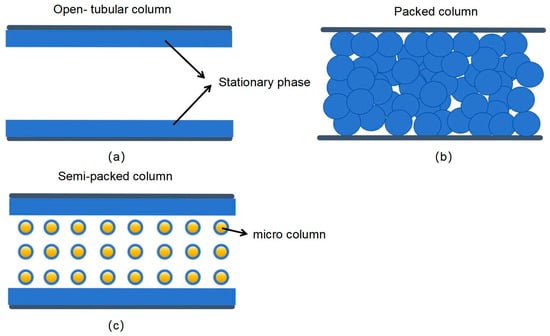

The structural layout of MEMS µGC columns is a critical factor influencing their performance. Based on the presence of packing materials or microstructures within the channel, MEMS µGC columns can be classified into three categories: open-tubular, packed, and semi-packed [15], as illustrated in Figure 2. Each category possesses distinct advantages and limitations regarding separation efficiency, sample capacity, and operational conditions. In recent years, driven by advancements in micro-nanofabrication technology, increasing research attention has been directed toward optimizing these structural layouts to enhance the separation efficiency and analysis speed of MEMS µGC columns.

Figure 2.

Various types of gas chromatography (GC) columns. (a) Open-tubular column, with a thin film of stationary phase coated on the inner wall; (b) Packed column, where small particles of stationary phase are packed inside the column; (c) Semi-packed column with a thin film stationary phase.

3.1. Open Tubular Columns

Open tubular columns represent the earliest structural type used in MEMS gas chromatography. The interior of an open tubular column contains no packing material or other microstructures; the stationary phase is directly coated onto the inner wall of the column body. This design is simple and easy to fabricate, making it suitable for relatively simple gas analyses. In 1970, Terry’s team [16] successfully fabricated the first open tubular column within a silicon-glass structure, after which numerous research groups began adopting this design. Open tubular columns are typically used for analyzing low molecular weight gases, and their separation performance is limited by the uniformity and stability of the inner wall coating. Due to the absence of packing or microstructures, the sample capacity of open tubular columns is relatively low, making them suitable for the separation of fewer components.

3.2. Packed Columns

In contrast to open-tubular designs, packed MEMS µGC columns incorporate packing materials or internal microstructures to augment the specific surface area and sample capacity. In these packed configurations, the stationary phase is typically coated onto micro-particles that are subsequently packed into the column channels. While packed designs significantly enhance the sample partition surface area and potential column efficiency, they suffer from inherent drawbacks: susceptibility to eddy diffusion effects and increased mass transfer resistance, which can compromise overall separation performance. For instance, Sun et al. [17] from the Institute of Electronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, developed a packed serpentine µGC column. With a total length of 1.6 m, this device achieved a theoretical plate number of 5800 plates/meter, demonstrating excellent separation capabilities for CO, CH4, and C2–C4 alkanes/alkenes. However, packed columns typically require higher inlet pressures to maintain adequate carrier gas flow velocities, and their complex flow path topologies often result in significant pressure drops.

3.3. Semi-Packed Columns

Semi-packed columns offer a compromise solution between packed and open-tubular designs. By incorporating micro-pillar arrays or structured packing elements within the channel, this configuration simultaneously increases the specific surface area and sample capacity of the column while effectively reducing mass transfer resistance caused by eddy diffusion, thereby optimizing separation performance [18,19]. In recent years, an increasing number of research groups have adopted semi-packed structures, particularly in the design of MEMS µGC columns.

For instance, Ali et al. [20] from Virginia Tech proposed a semi-packed column structure featuring an array of square micro-pillars. With a pillar side length of 20 μm and a spacing of 30 μm, the design facilitated a uniform distribution of flow velocity, significantly mitigating eddy diffusion effects and enhancing the separation efficiency of the column.

At the Institute of Electronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Sun et al. [21] further optimized the design of semi-packed MEMS µGC columns by adopting a circular micro-pillar array structure. This study utilized COMSOL Multiphysics simulations to optimize the layout of the pillar array, aiming to minimize pressure loss and improve flow uniformity. Ultimately, high-efficiency separation was achieved experimentally, yielding a theoretical plate number of 9500 plates/meter. However, it must be noted that such numerical simulations are typically predicated on simplified assumptions of idealized smooth walls and steady-state flow. In reality, sidewall roughness (specifically “scalloping”) and channel dimensional deviations introduced by the Deep Reactive Ion Etching (DRIE) process can significantly alter boundary layer behavior. While this study validated the final separation performance experimentally, a systematic sensitivity analysis regarding the validity of boundary condition settings and the predictive discrepancies arising from non-ideal fabrication tolerances remains absent. Consequently, future research utilizing numerical tools for design optimization should place greater emphasis on validating the alignment between model assumptions and the realistic features of micro-nanofabrication.

3.4. Serpentine Structure Design

Serpentine geometry has emerged as a significant direction in the design of MEMS µGC columns in recent years. Through ingenious tortuous channel design, serpentine structures achieve extended separation paths within a compact footprint, thereby enhancing separation performance. A distinct advantage of the serpentine configuration is the mitigation of dispersion effects; particularly under high-pressure conditions, it effectively reduces peak broadening caused by eddy diffusion.

For instance, Pai et al. [22] from the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory developed a MEMS µGC column with a circular cross-section based on a serpentine geometry. This device was successfully applied to the trace detection of hazardous chemicals, such as trinitrotoluene (TNT) and VX nerve agent, demonstrating significant achievements in enhancing analytical sensitivity and achieving rapid separation. Similarly, the Stadermann group at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory developed a serpentine column with a rectangular cross-section, demonstrating advantages in the rapid separation of a four-alkane mixture. Experimental results indicated that this serpentine design outperformed traditional spiral structures in terms of both separation speed and efficiency.

3.5. Novel Microstructure Designs

With the further advancement of MEMS technology, novel microstructure designs continue to emerge, aiming to further optimize gas flow velocity distribution and enhance separation efficiency. In 2022, Chen, B. et al. [23] from the Shanghai Institute of Microsystem and Information Technology (SIMIT), Chinese Academy of Sciences, designed and fabricated a novel semi-packed MEMS µGC column featuring an array of elliptical micro-pillars within the channel. The streamlined design of these elliptical pillars significantly improved the flow velocity field distribution, thereby enhancing separation performance. This design not only increased the channel surface area and improved the sample capacity of the column but also reduced the effective width of the column by optimizing the micro-pillar array layout, thereby further elevating column efficiency.

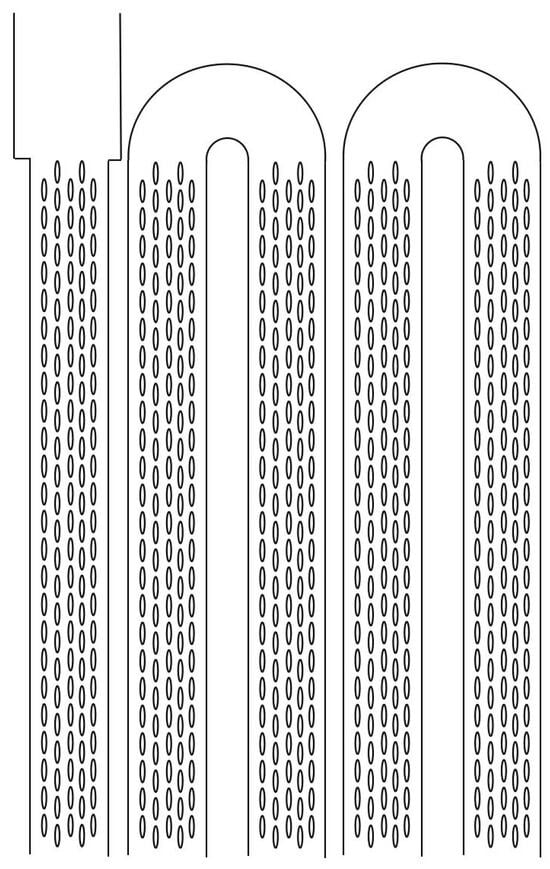

In 2024, the same team [24] proposed a semi-packed column with a staggered elliptical pillar array (SC-S) fabricated using MEMS technology and compared its separation performance with that of a semi-packed column featuring an aligned elliptical pillar array (SC-A). Figure 3 illustrates the schematic of the serpentine semi-packed gas chromatography column with staggered elliptical micro-pillars. Simulation and experimental data indicated that as the width of the stagnation zone decreased, both the area and height of the chromatographic peaks increased. When separating a C8–C10 alkane mixture at a concentration of 10 ppm, the peak heights of octane and nonane increased by 65.06% and 130.00%, respectively, while their peak areas increased by 120.45% and 168.18%, respectively. Furthermore, during the separation of the C8–C10 alkane mixture at 10 ppm, the chromatographic peak of decane was almost unidentifiable in the SC-A configuration, whereas it remained clearly visible in the SC-S configuration.

Figure 3.

Elliptical micro-pillars in staggered arrangement within a serpentine semi-packed gas chromatography column.

3.6. Critical Assessment of Structural Trade-Offs

Although various MEMS µGC columns have demonstrated excellent separation performance in laboratory settings, the engineering selection for aerospace applications requires a rigorous confrontation of the multi-dimensional trade-offs between chromatographic efficiency, hydraulic resistance, and fabrication robustness. There is no universally “optimal” structure; the choice of topology is fundamentally a multi-objective optimization process tailored to specific mission constraints:

- Separation Efficiency vs. Pneumatic Cost: Packed columns offer superior retention capabilities through high phase ratios and surface areas. However, the immense hydraulic resistance induced by random packing leads to a sharp increase in power consumption, posing a severe challenge to the limited energy budget of spacecraft payloads. In contrast, open-tubular columns exhibit the lowest pressure drop, making them suitable for low-power, rapid analysis. However, they are fundamentally limited by the “Corner Effect” in rectangular channels, where liquid phase pooling in corners significantly increases mass transfer resistance, thereby capping the peak capacity.

- Theoretical Models vs. Fabrication Defects: Semi-packed micro-pillar arrays are theoretically regarded as the optimal balance between efficiency and pressure drop, designed to eliminate eddy diffusion (A-term) through ordered geometry. However, this theoretical advantage is often compromised in practice by fabrication defects such as “scalloping” and sidewall tapering introduced by the DRIE process. These microscopic roughness features not only disrupt the ideal laminar flow field but also lead to non-uniform stationary phase coating. Consequently, experimental efficiencies often fall short of COMSOL simulation predictions due to significant peak tailing.

- Structural Complexity vs. Mechanical Reliability: Considering the harsh vibration environment of launch (e.g., 14.1 Grms), simpler structures correlate with higher reliability. Open-tubular columns, consisting of simple channels, present the lowest risk of mechanical failure. Conversely, high-aspect-ratio micro-pillar arrays, while increasing surface area, pose a risk of fracture or collapse under high-frequency vibrations (especially at aspect ratios > 10:1). Furthermore, the dead volumes inherent in complex pillar structures increase the risk of sample carry-over, a potential failure mode for long-term, maintenance-free space station monitoring missions.

In conclusion, future designs should not blindly pursue maximum theoretical plate numbers. Instead, selection must be mission-specific: for rapid screening of light gases, open-tubular columns remain the preferred choice due to their robustness and low power consumption; for high-resolution separation of complex organics, semi-packed columns require not only optimized lithographic design but also strict control of etching roughness and mechanical simulation validation to ensure survivability in harsh environments.

4. Fabrication Processes of MEMS µGC Columns

The fabrication of MEMS µGC columns encompasses a diverse array of micro-nanofabrication technologies, each offering distinct advantages that enable the optimization of column performance tailored to specific design requirements. The primary fabrication techniques include Deep Reactive Ion Etching (DRIE), Laser Etching Technology (LET), LIGA (Lithographie, Galvanoformung, Abformung), and 3D printing technologies.

4.1. Deep Reactive Ion Etching (DRIE) Technology

Deep Reactive Ion Etching (DRIE) is a dry etching process based on fluorine-based gases, utilizing alternating cycles of etching and passivation to achieve high-aspect-ratio silicon etching. The core of this technology is the “Bosch process,” which employs SF6 gas to generate F radicals that react with the silicon surface, forming the volatile product SiF4. Simultaneously, C4F8 gas deposits a protective film during the etching process to prevent sidewall etching, thereby enabling highly vertical etch profiles. DRIE technology is characterized by high precision, high aspect ratio, and high anisotropy, making it widely applicable in MEMS manufacturing, 3D integration of integrated circuits, and advanced packaging. For instance, the team led by Ali at Virginia Tech used standard Bosch process DRIE to etch silicon wafers to a depth of 180 µm, increasing the column’s surface area to approximately 15 cm2. This significantly enhanced the column’s separation efficiency, more than doubling the surface area compared to a similar open tubular MEMS column (approximately 7 cm2).

4.2. Laser Etching Technology (LET)

Laser Etching Technology (LET) utilizes high-precision laser beams to directly inscribe microfluidic channel structures onto substrates, characterized by high precision and flexibility. By modulating parameters such as laser power, frequency, and scanning speed, the etch depth and width can be precisely controlled, making it suitable for fabricating complex microchannel architectures. A distinct advantage of laser etching lies in its material versatility; it is not limited to silicon but is also applicable to substrates such as glass and polymers, thereby broadening the material selection for column fabrication.

For instance, Sun et al. from the Institute of Electronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, employed laser etching technology to fabricate serpentine micro-packed gas chromatography columns. They successfully etched rectangular microchannels with cross-sectional dimensions of 0.6 mm × 0.6 mm on both silicon and glass wafers, achieving a total column length of 1.6 m. Additionally, Kaanta et al. [25] utilized laser etching technology to develop a monolithic gas chromatography assembly integrated with micro-pillars and a thermal conductivity detector (TCD).

4.3. LIGA Technology

LIGA (Lithographie, Galvanoformung, Abformung)—a micro-nanofabrication technology that combines lithography, electroplating, and molding—is distinguished by its capability to fabricate microstructures with high aspect ratios. Its primary process steps include: defining microstructure patterns on a substrate via photolithography, enhancing the height and structural strength through electroplating, and finally achieving mass production via injection molding. LIGA technology facilitates the large-scale manufacturing of high-aspect-ratio microstructures and is compatible with a diverse range of materials, including metals and plastics, thereby meeting various application requirements.

For instance, Bhushan et al. [26] reported the first nickel-based MEMS µGC column chips fabricated using LIGA technology, achieving an aspect ratio as high as 12:1. Due to the superior thermal conductivity of nickel, these columns are particularly well-suited for temperature-programmed applications. Such MEMS µGC columns are capable of achieving high-efficiency separation within short timeframes, making them ideal for rapid gas analysis.

4.4. Three-Dimensional Printing Technology

In recent years, Three-dimensional printing technology has emerged as a prominent force in the field of micro-nanofabrication, demonstrating immense potential particularly in low-volume production and customized manufacturing. 3D printing enables the rapid translation of design models into physical prototypes, thereby shortening the research and development cycle. Furthermore, it is capable of fabricating microstructures with complex geometries, making it well-suited for the design of innovative MEMS µGC column channel architectures. Common 3D printing techniques include Stereolithography (SLA) and Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), both of which are capable of fabricating MEMS µGC columns with high precision.

For instance, Phyo et al. [27] utilized 3D printing technology to fabricate a 1 m long µGC column with a rectangular spiral geometry using Ti6Al4V alloy powder, featuring an internal diameter of 500 μm. This column successfully separated a mixture of 12 alkane gases, demonstrating the application potential of 3D printing technology in the field of gas chromatography. Although 3D printing technology remains in the exploratory stage, it exhibits significant advantages in personalized and customized manufacturing, particularly in the realms of rapid prototyping and low-volume production.

5. Stationary Phases and Preparation of MEMS µGC Columns

5.1. Role and Requirements of the Stationary Phase

In MEMS µGC columns, the stationary phase serves as the critical functional layer for gas separation. Its primary mechanism involves inducing differential partitioning behaviors through physical or chemical interactions with sample components, thereby achieving effective separation within the mobile phase [28,29,30,31,32,33]. In aerospace missions, the performance of the stationary phase directly impacts the accuracy and repeatability of analytical results, as well as the long-term operational stability of the system. Given that spacecraft typically operate in enclosed or semi-enclosed environments characterized by extended mission durations and limited maintenance capabilities, stationary phase materials are required not only to possess superior separation performance but also to comply with the stringent requirements of aerospace systems regarding miniaturization, low-power operation, and long-term reliability.

Regarding material properties, the stationary phase must exhibit exceptional chemical and thermal stability to withstand the complex and extreme operating conditions of spacecraft. The materials are required to maintain structural integrity and performance stability over prolonged periods within environments characterized by vacuum, high radiation, and severe temperature fluctuations [34,35,36,37,38]. For instance, in deep-space exploration missions, columns often operate across a temperature range spanning from −100 °C to over 200 °C. Consequently, the stationary phase must possess characteristics such as resistance to thermal decomposition, radiation hardness, and low column bleed (evaporation loss) to ensure that separation performance does not suffer significant degradation throughout the duration of the mission.

In terms of selectivity, stationary phase materials require targeted design and optimization based on the physicochemical properties of the gases to be analyzed in aerospace missions. Gas analysis targets in aerospace applications typically encompass major constituent gases (e.g., oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide) as well as various trace gases and volatile organic compounds (e.g., ammonia, methane, formaldehyde), which exhibit significant differences in polarity, molecular weight, and volatility. The surface chemical composition and polarity characteristics of the stationary phase must be capable of inducing differentiated physical or chemical interactions with target components, thereby enhancing the selectivity and resolution of chromatographic separation. For example, non-polar polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) is suitable for separating low-polarity gases, whereas polar polyethylene glycol (PEG) demonstrates superior performance in the separation of polar molecules. Through the rational design of polarity gradients and molecular recognition characteristics of the stationary phase, high-efficiency separation of complex gas mixtures can be achieved.

Under long-term operating conditions, the stationary phase must also possess low column bleed and superior resistance to contamination. If the stationary phase material undergoes leaching, degradation, or adsorption side reactions, it will lead to detection baseline drift and peak distortion, subsequently affecting separation reproducibility and analytical accuracy [39,40,41,42]. This is particularly critical in deep-space missions where equipment maintenance or replacement is impossible; therefore, the stationary phase must exhibit excellent anti-aging properties and chemical inertness to ensure the stability and reliability of the system over extended operation periods.

From a fabrication process perspective, stationary phase materials must be highly compatible with MEMS microfabrication technologies. Since MEMS µGC columns feature micro-scale channel structures, the stationary phase must achieve a uniform, controllable, and robust coating on the inner channel walls. The preparation method must be coordinated with photolithography, etching, and bonding processes to ensure consistency in film thickness, adhesion, and surface integrity. Process compatibility not only influences the separation performance of the stationary phase but also determines the integration level and reproducibility of the entire MEMS system.

In summary, the role of the stationary phase in MEMS µGC columns is reflected not only in separation efficiency but also directly correlates with the reliability, stability, and long-term availability of the system in complex space environments. Its design requires achieving a balance between chemical stability, selectivity, contamination resistance, and process adaptability to meet the comprehensive requirements of aerospace gas monitoring equipment for high precision, low power consumption, and long operational life. The continuous optimization and innovation of stationary phases will be key to driving MEMS µGC columns toward achieving efficient, stable, and intelligent gas analysis in aerospace missions.

5.2. Selection of Stationary Phase Materials

Traditionally, Traditionally, polymeric stationary phases such as Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) have been widely used in MEMS GC systems [43,44,45,46]. Their widespread adoption is due to mature fabrication processes, low cost, diverse polarity options, and the ability to be uniformly coated onto the inner column wall via static or dynamic coating methods. PDMS, a typical non-polar polymer, offers excellent thermal stability, chemical inertness, and good film-forming properties, making it suitable for separating most low-polarity volatile organic compounds (VOCs), such as alkanes, aromatic hydrocarbons, and some halogenated compounds. Its high flexibility also facilitates the formation of uniform coatings within MEMS channels. In contrast, PEG exhibits strong polar selectivity, enabling effective interactions with polar small molecules like water, alcohols, and amines through hydrogen bonding and dipole–dipole interactions, thus making it widely applicable for the analysis of polar components. However, these polymers have limitations in high-temperature or strongly polar gas environments, such as thermal decomposition, swelling, or bleeding, which can compromise film stability and analytical reproducibility [47,48,49,50]. Furthermore, in high-aspect-ratio microchannels, the pooling effect—where coating liquid accumulates at channel corners—often leads to non-uniform stationary phase film thickness and aggregation, ultimately causing chromatographic peak broadening and reduced column efficiency.

With advancements in materials science, researchers are increasingly introducing novel functional materials to address the shortcomings of traditional polymeric stationary phases. Ionic Liquids (ILs), composed of organic cations and inorganic or organic anions, have emerged as a research focus for μGC stationary phases due to their negligible vapor pressure, excellent thermal stability, highly tunable molecular structures, and dual solubility for both polar and non-polar compounds [51,52]. For example, ILslikeTrihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide([P6,6,6,14][NTf2]) have been demonstrated to maintain good physical stability and chemical inertness even at elevated temperatures, making them suitable for the selective recognition of trace components in complex gas mixtures. Moreover, supporting ILs on high-surface-area mesoporous silica or nanoporous frameworks can effectively control film thickness and enhance stationary phase selectivity, proving particularly useful for detecting multi-component VOCs in spacecraft cabins, such as amines, aldehydes, and thiols.

Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) represent another frontier in stationary phase research. Comprising metal ions/clusters and organic linkers, MOFs possess highly ordered three-dimensional porous structures, extremely high specific surface areas (up to several thousand m2/g), and tunable pore sizes and functional sites, making them an ideal platform for adsorption/separation [53,54,55]. Studies have shown that coating MOF materials like ZIF-8 and UiO-66 onto the inner walls of microcolumns or the surfaces of micropillar arrays not only enhances the resolution of molecules with similar sizes but different polarities but also enables high-resolution separation under shorter column lengths and lower pressure drops. Additionally, MOFs demonstrate good thermodynamic stability in extreme environments such as high vacuum and elevated temperatures, showing great potential for the online monitoring of complex atmospheric samples in manned space missions.

Carbon-based nanomaterials, such as reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO), Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), and Graphene Oxide (GO), have gained significant attention in MEMS stationary phase research in recent years due to their ultra-high specific surface area, abundant surface functional groups, good thermal conductivity, and tunable interfacial interactions. Literature reports indicate that composites of rGO and PDMS can form structurally stable, uniformly distributed composite coatings, exhibiting excellent response rates and separation selectivity for C5–C12 alkanes [56,57,58,59]. CNTs can be surface-functionalized with groups like carboxyl, hydroxyl, or aryl groups to enhance their recognition capabilities for aromatic compounds, halogenated compounds, and explosive precursors, making them particularly suitable for military security and space toxic gas monitoring scenarios. Furthermore, carbon materials possess excellent radiation resistance and anti-oxidation capabilities, ensuring good long-term stability in the high-radiation, highly oxidative space environment.

Beyond the intrinsic properties of the materials, the morphological control of the stationary phase within the microchannels, along with film uniformity and adhesion stability, are also critical factors determining separation quality [60,61,62,63,64]. In high-aspect-ratio micropillar channels, introducing micropillar arrays and optimizing the channel geometry can effectively mitigate coating pooling and edge effects, thereby improving film uniformity and the plate number. Furthermore, modern micro-nanofabrication techniques such as Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD), sol–gel methods, and electrospinning are being extensively explored to construct nanoscale-controlled stationary phase films. These methods not only enhance the interfacial adhesion between the material and the substrate but also provide technical support for the design of multi-layer gradient stationary phases and the realization of programmable separation paths.

To address the challenges in directly comparing diverse MEMS-GC devices due to variations in geometric structures and operating conditions, this review adopts a normalized methodological framework. Instead of relying solely on absolute metrics—which are heavily biased by column length and chip dimensions—we employ the following normalized indicators for assessment:

Efficiency per Unit Length (N/m): This metric normalizes separation efficiency relative to the column length, eliminating the influence of the total chip footprint. It serves as a direct reflection of the precision of the microfabrication process and the quality of the stationary phase coating.

Specific Power Consumption: We evaluate thermal efficiency by correlating power consumption with the temperature ramp rate, thereby offering a more equitable comparison across designs with varying thermal masses.

Table 2 synthesizes the performance data of representative MEMS-GC studies using these normalized metrics to facilitate a rigorous cross-comparison.

Table 2.

Overview of MEMS Column Characteristics and Stationary Phases.

5.3. Preparation of Stationary Phases

5.3.1. Coating Methods

Static coating and dynamic coating are the two primary methods currently used for applying stationary phases in capillary chromatographic columns [65,66,67,68]. In the dynamic coating process, a stationary phase solution is propelled through the capillary column by an inert gas, forming a thin film on the inner wall. The thickness of this liquid film can be controlled by adjusting the gas flow rate and the concentration of the stationary phase solution. The film thickness is closely related to the gas flow rate during coating, the surface tension and viscosity of the coating solution, and the velocity of the liquid plug, as described by the following formula:

In the formula, represents the stationary phase film thickness, is the capillary radius, is the surface tension of the coating solution, is the viscosity of the coating solution, and is the velocity of the liquid plug.

In contrast, the static coating method involves first completely filling the entire chromatographic column with the stationary phase solution, then sealing one end and applying a vacuum to the other end. This allows the solvent to evaporate slowly at a controlled temperature, leaving a stationary phase film on the column wall. This method offers superior controllability because the stationary phase deposits entirely onto the wall. The thickness of the stationary phase film can be precisely calculated based on parameters such as the surface area of the chromatographic column, the concentration of the stationary phase, and its density.

Typically, static coating is superior to dynamic coating and represents the most widely adopted method. Primarily, during the static coating process, the stationary phase deposits entirely onto the column wall, ensuring highly uniform film thickness. As the stationary phase undergoes no axial movement during coating, this method yields a more uniform and stable film, which is particularly critical for analyses demanding high separation efficiency. Secondly, the uniform coating of the column wall inherent to the static method guarantees high consistency in the thickness of the stationary phase layer. This consistency is paramount for the precise control of chromatographic column performance and for achieving enhanced separation efficiency.

To further enhance the stability and adhesion of the stationary phase film, cross-linking techniques can be employed. Cross-linking strengthens the adhesion of the stationary phase by forming covalent bonds between molecules or bonding them to the column wall, thereby improving the film’s durability and stability. For instance, prior to coating polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), a thermally activated cross-linking agent (such as dicumyl peroxide) can be added to the stationary phase solution. After coating, the cross-linking process is completed by heating the column to 180 °C at a ramp rate of 5 °C/min and maintaining this temperature for 4 h under a nitrogen atmosphere. This method enhances the adhesion between the stationary phase and the column wall, consequently improving the column’s stability and service life, particularly under high-temperature conditions and prolonged operation.

The combination of static coating and cross-linking techniques effectively enhances the film thickness uniformity and stability of the stationary phase, thereby providing a guarantee for the long-term reliability and high-efficiency performance of MEMS µGC columns.

5.3.2. Semiconductor Process-Based Stationary Phase Preparation

Conventional coating or solid particulate packing processes are often incompatible with the requirements of microfabrication; furthermore, these steps typically necessitate “offline” execution following the completion of the microfabrication process. Consequently, the development of a reproducible stationary phase preparation process remains one of the primary challenges in the fabrication of MEMS µGC columns [69,70].

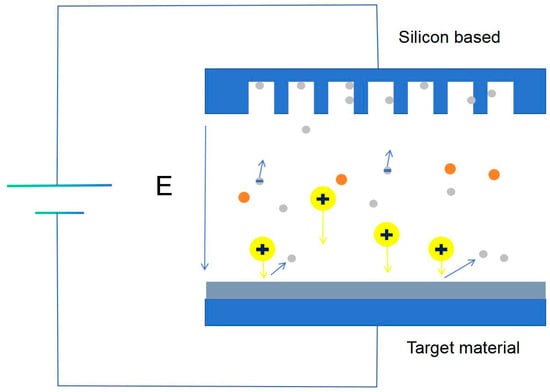

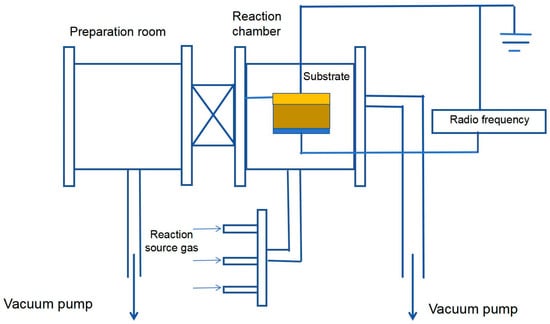

To address this issue, stationary phase preparation methods based on semiconductor processing have emerged, principally comprising techniques such as sputtering and Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD). Sputtering, as a pivotal Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) technique, achieves the release of atoms or molecules through the ion bombardment of a target material, subsequently depositing a high-quality thin film onto the substrate [71].

For instance, Narayanana, S. et al. [72] employed a physical sputtering method to deposit silicon and graphite onto a single-layer silicon wafer. The wafer was then bonded with heat-resistant glass to form the chromatographic column, achieving a separation time of 15 s for C1 to C9 hydrocarbons. The team led by Vial at ESPCI Paris [73] utilized sputtering technology to grow a silicon dioxide (SiO2) layer approximately 3 µm thick as the stationary phase within the channels of a semi-packed MEMS micro gas chromatography column. Experimental results demonstrated that this stationary phase effectively separated mixtures such as methane, ethane, propane, and butane, achieving a theoretical plate number of up to 5000 plates/m. Figure 4 shows a schematic diagram of the stationary phase prepared by sputtering technology. This method offers significant advantages, including high-purity thin film deposition, good adhesion, and a wide selection of materials. However, it also faces challenges such as complex equipment, low deposition rates, and low target material utilization.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the sputtering technique.

Unlike Physical Vapor Deposition, Chemical Vapor Deposition involves chemical reactions during the process. CVD directly uses gases, or transforms solids/liquids into gases by other means, as reactant source gases. These source gases are then decomposed, reduced, or undergo other chemical reactions induced by light, electricity, magnetism, heat, or other energy sources, leading to film deposition on the substrate. Figure 5 shows a schematic diagram of the stationary phase prepared by CVD technology. Based on the different excitation sources, the reactions can be broadly classified into Low-Pressure Chemical Vapor Deposition (LPCVD), Photochemical Vapor Deposition (PCVD), Thermal Chemical Vapor Deposition (TCVD), and Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition (PECVD), among others. The process typically includes steps such as gas transport, surface adsorption, chemical reaction, film growth, removal of unreacted species and by-products, and cooling. CVD offers advantages such as the generation of high-quality films, precise control, scalability, and conformal deposition. Nevertheless, it also presents drawbacks including high cost, the production of toxic by-products, and sensitivity to process parameters.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of CVD.

Serrano, G. et al. [74] employed Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) technology to deposit single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) as the stationary phase into microchannels with a square cross-section of 100 µm × 100 µm and a length of 50 cm. The fabricated micro gas chromatography column chip effectively separated compounds such as hexane, octane, nonane, and decane. Similarly, Reed et al. utilized Chemical Vapor Deposition to deposit single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) with a high specific surface area within a MEMS column, intended for ultra-fast gas chromatography analysis at a ramp rate of 26 °C/s.

5.3.3. Quantitative Benchmarking of Preparation Methods

Addressing the lack of quantitative comparison in existing literature, Table 3 benchmarks the quality of stationary phase films using engineering metrics derived from fundamental physicochemical principles:

Table 3.

Quantitative Benchmarking of Typical Performance Indicators for Stationary Phase Preparation Methods.

Uniformity (Thickness Deviation): CVD technology achieves the highest uniformity due to its surface-reaction-controlled mechanism, typically yielding a thickness deviation of <1%. Even within high-aspect-ratio channels, it guarantees a step coverage exceeding 95%. In contrast, dynamic coating is limited by the “pooling effect” of liquid solvents at the corners of rectangular channels, resulting in thickness deviations often exceeding 10–20%.

Adhesion (Bond Energy): Mechanical reliability is fundamentally quantified by interfacial bond energy. Traditional coating methods rely on weak physisorption (<50 KJ/mol), posing a risk of delamination under launch vibrations (e.g., 14.1 Grms). Semiconductor-based methods (CVD/sputtering) establish robust covalent or mixed bonding (>300 KJ/mol) with the substrate, providing superior structural integrity.

Aging (Temperature Limits): Aging behavior is benchmarked via the Maximum Operating Temperature (MOT). Polymeric phases (e.g., PDMS) typically exhibit significant bleed or degradation above 260 °C, whereas inorganic films prepared via CVD or sputtering remain stable at temperatures exceeding 400 °C, effectively mitigating baseline drift caused by stationary phase bleed in vacuum environments.

5.4. Column Heating Technologies

Column heating technology is a critical factor influencing the separation efficiency [75,76,77], response speed, and energy consumption level of MEMS gas chromatography systems. Compared to traditional benchtop gas chromatographs that rely on external ovens for column temperature control, MEMS systems require heating methods that are more miniaturized, faster-responding, and offer higher thermal uniformity. Consequently, developing heating technologies that are structurally compact, feature rapid heating rates, precise temperature control, and low power consumption has become a core aspect of MEMS µGC system integration.

- (1)

- Integrated Microheaters

The most prevalent current heating method involves integrating thin-film microheaters onto the chromatographic column substrate, typically using metals (such as Pt, Ni) or polysilicon materials, achieving localized heating through the Joule heating effect [78,79,80]. Microheaters can be directly fabricated onto silicon-based or glass-based column structures using standard MEMS processes (such as sputtering, photolithography, and etching), enabling high integration and rapid temperature control. This method can achieve heating rates of 10–30 °C/s, making it suitable for fast gas chromatography analysis requirements. Its advantages include fast heating response, concentrated heat generation, and high control precision, while also allowing for precise temperature control through the integration of temperature sensors in closed-loop systems. However, microheaters face issues such as current density limitations, heat loss concentrated at the edges, and potential material fatigue due to localized thermal stress, which can affect their long-term stability [81,82,83].

- (2)

- Monolithic or Bulk Heating Structures

Some MEMS µGC systems employ a bulk heating approach, where the entire chip is heated to achieve column temperature control [84,85]. For example, the µGC column is embedded within a packaging cavity, and a uniform heat source is provided by an off-chip ceramic heater or a flexible heating film. This method is structurally simple and highly adaptable, suitable for early-stage designs or temporary integration platforms. However, it suffers from slow heating rates, large thermal inertia, and relatively high power consumption, which is detrimental to high-throughput and fast-response applications.

- (3)

- Infrared Laser Heating and Inductive Heating Technologies

In recent years, researchers have proposed novel non-contact heating methods such as Infrared Laser Heating and high-frequency electromagnetic Inductive Heating. Infrared heating enables rapid, uniform heating of the MEMS chip surface or localized areas through laser scanning, making it suitable for multi-channel parallel chromatography systems. Inductive heating relies on eddy currents generated within metallic structures on the chip, achieving high heating rates of tens of °C/s while avoiding the direct contact issues associated with traditional heaters. These technologies offer advantages such as high response speed, low latency, non-contact operation, and suitability for miniaturized system packaging [84,85,86]. However, they still require further optimization in terms of system integration complexity and power control precision.

- (4)

- Temperature Control Strategies and Intelligent Thermal Management

As the complexity of MEMS µGC systems increases, temperature control extends beyond heating itself to include high-precision sensing, feedback, and thermal field uniformity regulation [87,88,89]. Most current systems integrate temperature sensors (e.g., Pt RTDs, thermocouples) with PID temperature control loops to achieve stable temperature control and programmed temperature ramps. Furthermore, some systems incorporate thermal isolation trenches, thermal coupling layers, and heat shielding structures to further enhance heating efficiency and reduce energy consumption.

6. Aerospace Applications of MEMS µGC Columns

In aerospace missions, gas analysis systems are required to operate stably over long periods under conditions of extreme resource constraints and complex space environments, presenting engineering constraints that are fundamentally different from those in ground-based laboratory or industrial applications. Compared to terrestrial applications, aerospace systems impose significantly more stringent requirements regarding volume, mass, power consumption, system integration, and adaptability to vacuum, radiation, vibration, and thermal cycling environments. These aerospace-specific constraints directly influence the structural design, material selection, and system integration strategies of micro gas chromatography systems, endowing aerospace µGC technology with distinct application-specific characteristics in terms of design objectives and engineering implementation paths.

From the perspective of technical development trajectories, micro gas chromatography systems in the aerospace domain can be categorized into two types: one comprises flight-heritage systems—spacecraft-borne gas analysis systems that have completed on-orbit deployment and acquired flight validation data; the other consists of mission-oriented demonstrations—MEMS micro gas chromatography laboratory or engineering prototype systems developed to meet specific aerospace mission requirements, with performance and engineering feasibility validated under ground or simulated space conditions. Distinguishing between these two categories helps to clarify the maturity levels and actual application potential of different technical solutions within the context of aerospace missions.

6.1. Validation Studies of Mission-Oriented MEMS µGC Systems

In deep space planetary exploration missions, exploration payloads are typically required to perform in situ analysis of organic molecules in unknown environments under conditions of vacuum, radiation, and significant temperature fluctuations, all while being subject to stringent volume and power limitations. However, adaptability validation for such extreme environments is generally a focus of engineering efforts in the later stages of technology maturity. Consequently, current core research primarily prioritizes breakthroughs in separation performance, sensitivity, and the capability to analyze complex matrices.

To meet the core demand for high-fidelity identification of organic molecules in deep space exploration, Blase et al. [90] conducted research on coupling a MEMS gas chromatography system with mass spectrometry (MS) for the separation and analysis of organic compounds in space environments. The results indicated that the MEMS µGC column, when coupled with a high-sensitivity MS system, maintained superior separation performance and stable retention behavior, achieving effective separation of alkanes and their isomers in the C5–C9 range. The relative standard deviation (RSD) of retention times was ≤2%, and the average theoretical plate number reached 16,239, demonstrating excellent separation efficiency. This study validated the core potential of MEMS µGC columns for effective separation and stable operation within a space application context at the device level, although it did not conduct specific adaptability validation for aerospace extreme environments such as launch vibration, radiation exposure, and extreme thermal cycling.

In subsequent research, Blase et al. [91] further systematically evaluated the separation performance and applicability of MEMS µGC columns for future planetary landing missions. This study utilized a 5.5 m long MEMS column with a 150 μm × 240 μm rectangular channel (coated with OV-5 stationary phase, consistent with that used in mature space instruments like SAM and MOMA). The research focused on validating the analytical capability for organic matter (alkanes) and biologically relevant molecules (fatty acid methyl esters, derivatized amino acids). Results showed that the column exhibited a good linear response over a concentration range of two orders of magnitude, with a limit of detection (LOD) as low as 3–43 pmol, approaching the sensitivity requirements for detecting organics in ice samples for the Europa exploration mission (1 pmol/g). The reproducibility of retention times was excellent, with the RSD for most compounds being ≤0.3%, and remaining ≤0.7% even during the analysis of a 40-component “mixture sample.” The chromatographic resolution reached 200–300, with a peak capacity of 124 ± 2 within a 435 s retention time window, successfully achieving baseline separation of multiple components in complex samples. Furthermore, this column could be employed as the primary column in comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography; compared to a commercial 30 m column, it achieved similar separation effects but reduced analysis time by 30%, further verifying its potential for complex matrix analysis. These results indicate that, although the relevant systems are still in the ground validation stage and have not yet involved reliability testing under extreme aerospace environments, MEMS µGC columns possess clear development prospects in meeting the core requirements of deep space exploration missions regarding separation performance, sensitivity, and analytical efficiency.

Beyond device-level research, aerospace applications also place a high priority on system-level integration and resource utilization efficiency. Rizk-Bigourd M et al. [92] reported an ultra-compact micro gas chromatography prototype system designed for space exploration missions. Based on lab-on-a-chip MEMS technology, this system integrates a MEMS preconcentrator, a MEMS µGC column approximately 5 m in length, and micro-detection modules (μ-TCD and Nanometric Gravimetric Detector, NGD). The overall volume is merely 300–400 cm3, with an operating power consumption of less than 10 W, significantly satisfying the rigorous constraints on payload volume and power for space missions. Experimental results demonstrated that when analyzing typical volatile organic compounds such as n-pentane, n-hexane, benzene, and toluene, the coefficient of variation for retention time reproducibility was below 0.2%, and the detection limit was as low as 3.1 pmol (toluene), indicating good separation performance and repeatability. By optimizing stainless steel fluidic interfaces and selecting flight-heritage materials (such as Tenax TA adsorbent), the study enhanced the system’s mechanical robustness and adaptability potential, verifying the engineering feasibility of achieving high system-level integration of MEMS µGC technology under strict volume and power constraints. However, similar to previous studies, specific tests under vacuum, radiation, vibration, and extreme thermal cycling conditions were not conducted.

It is important to emphasize that the aforementioned MEMS µGC systems are primarily in the laboratory or engineering prototype validation stage. Their system-level reliability under extreme aerospace environments—such as launch vibration, long-term radiation exposure, and extreme thermal cycling—remains to be further confirmed through subsequent specific experiments and flight validation. Nevertheless, these mission-oriented demonstrations have fully validated the core advantages of MEMS-GC technology in terms of separation performance, sensitivity, miniaturization, and low power consumption, laying a key experimental and engineering foundation for the technology’s progression toward higher Technology Readiness Levels (TRL).

6.2. Flight-Heritage Aerospace Gas Chromatography Systems

In the field of manned spaceflight, gas chromatography and its miniaturized systems have been successfully applied in actual flight missions. Chutjian et al. introduced the Vehicle Cabin Atmosphere Monitor (VCAM) [93], a spacecraft cabin gas monitoring system developed by the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in collaboration with multiple institutions. Based on preconcentrator-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (PCGC/MS) technology, this miniaturized analytical instrument was designed specifically for the International Space Station (ISS) and the Crew Exploration Vehicle (CEV). VCAM is capable of autonomous, maintenance-free on-orbit operation (with a 1-year service life and daily automatic runs). It captures volatile organic compounds (VOCs) within the cabin using a carboxyl-adsorbent preconcentrator, separates them via a gas chromatography column, and detects them using a Paul ion trap mass spectrometer. The system achieves sub-ppm level detection for 90% of target compounds (covering three priority classes of contaminants) within a concentration range of 0.1 ppm to 100 ppm, complying with the 180-day Spacecraft Maximum Allowable Concentration (SMAC) standards. Simultaneously, it can directly identify major cabin gases such as nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon dioxide. By utilizing FPGA-based digital RF technology, the system significantly optimized volume, weight, and power consumption. Following its deployment on the ISS in 2008, VCAM provided reliable support for cabin air quality safety in long-duration manned missions and laid the foundation for the development of subsequent closed-environment atmosphere monitoring systems. Subsequent publications further reported the application results of VCAM in ISS and Orion missions, demonstrating the system’s ability to effectively separate and quantitatively analyze various volatile organic contaminants, thereby providing a reliable technological means for assessing cabin air quality in manned spacecraft [94].

Building upon the engineering validation of VCAM, NASA further developed and deployed the Spacecraft Atmosphere Monitor (SAM). Its Technology Demonstration Unit 1 (TDU1) was delivered to the ISS aboard the SpaceX-18 cargo mission in July 2019 and achieved continuous on-orbit operation from August 2019 to July 2021, accumulating extensive field data [95]. The system employs miniaturized Quadrupole Ion Trap (QIT) mass spectrometry technology, featuring compact dimensions of , a weight of , and power consumption of (). Its portability allows for deployment at various nodes within the ISS for environmental monitoring. Equipped with autonomous data analysis software, SAM can automatically perform mass spectral calibration, background subtraction, target species identification, and abundance reporting. Based on data collected by the SAM system, Madzunkov et al. systematically analyzed major cabin gas components (, , , , , etc.) and isotope ratios of , , , , and . The results indicated that the system maintained excellent stability and analytical performance under conditions of microgravity, space radiation, long-term thermal cycling, and continuous on-orbit operation. Its isotope ratio measurement precision and accuracy were comparable to laboratory-grade magnetic sector mass spectrometers, achieving a measurement precision of up to over h. Furthermore, it successfully completed a benzene contamination investigation within the ISS cabin with a detection limit as low as , validating its capability to monitor trace contaminants even without a gas chromatography module. As an upgraded version, TDU2 is planned to incorporate a micro gas chromatography unit to expand its capability for analyzing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and was scheduled for launch to the ISS in 2023. As typical gas analysis platforms with flight heritage, the long-term on-orbit operational experience of VCAM and SAM not only validates the reliability of miniaturized mass spectrometry technologyunder strict resource constraints and complex space environments but also establishes a solid engineering foundation for the deepened application of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) technology in the field of manned spaceflight.

Although the VCAM and SAM systems have not yet incorporated MEMS-fabricated µGC columns, their system-level design philosophies and operational experiences under aerospace environmental conditions—including vacuum, radiation, launch vibration, and thermal cycling—serve as critical engineering references and reliability benchmarks for the future integration of MEMS µGC technology into manned spaceflight missions.

6.3. Engineering Status and Mission Relevance of Aerospace µGC Systems

As the demand for miniaturized analytical technologies in aerospace missions continues to grow, the engineering maturity and mission relevance of gas chromatography systems have become critical metrics for evaluating their suitability for space applications. Compared to terrestrial applications, the aerospace environment imposes significantly more stringent requirements on analytical systems, including the capability for stable operation under vacuum and microgravity conditions, tolerance to mechanical vibrations and shocks during launch and on-orbit phases, reliability under long-term thermal cycling and radiation environments, and adherence to power and volume constraints under resource-limited conditions.

To more clearly demonstrate the engineering status of different gas chromatography systems in aerospace missions, Table 4 provides a comparative summary of flight-proven spacecraft-borne gas analysis systems versus MEMS micro gas chromatography research oriented toward aerospace applications. The comparison covers aspects such as adaptability to vacuum environments, considerations for radiation environments, launch vibration and structural robustness, adaptability to thermal cycling, and Technology Readiness Levels (TRL). It is evident that systems such as VCAM and SAM have been validated through long-term on-orbit operations, possessing clear flight heritage and achieving TRLs of 8–9. In contrast, existing MEMS μGC systems remain primarily at the laboratory validation or engineering prototype stage, with TRLs concentrated in the 3–5 range.

Table 4.

Comparison of Engineering Status and Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Aerospace Gas Chromatography Systems.

It is worth noting that although some MEMS-GC systems have conducted targeted performance validation studies within the context of space applications—such as coupling tests with mass spectrometry systems or separation performance assessments for planetary exploration missions—the majority of research still focuses on separation performance itself, without systematically covering the full environmental engineering validation processes required by aerospace missions. Consequently, from the perspective of engineering maturity, current MEMS μGC technology is still in a transitional phase, moving from “mission-relevant experimental validation” toward becoming “aerospace-qualified engineering systems.”

6.4. Engineering Maturity and Aerospace Deployment Challenges

Despite the series of experimental and engineering validation achievements obtained by micro gas chromatography and MEMS µGC technologies in aerospace-related applications, the transition from laboratory prototype systems to deployed systems for actual aerospace missions remains subject to significant challenges. Existing research indicates distinct differences in engineering maturity and application stages among different types of gas chromatography systems.

From the perspective of technology readiness, gas analysis systems currently operating on-orbit, such as VCAM and SAM, possess clear flight heritage, with their Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) reaching high standards. The stability of these systems under conditions of microgravity, radiation, thermal cycling, and long-term operation has been validated through actual flight missions. However, systems that have currently achieved flight validation have not yet incorporated MEMS-fabricated µGC columns; their core chromatographic components continue to rely primarily on conventional or semi-micro technologies.

In contrast, the majority of MEMS µGC systems reported in recent years remain at the stage of laboratory validation or engineering prototyping, with their technology maturity typically falling within the low-to-medium range (TRL 3–5). These studies focus primarily on validating the feasibility of separation performance, miniaturized integration, and low-power operation, whereas system-level reliability assessments addressing aerospace environmental conditions—such as launch vibration, long-term radiation exposure, vacuum compatibility, and extreme thermal cycling—remain relatively limited.

Analyzing from the perspective of engineering transition, the major challenges facing the deployment of MEMS µGC technology for aerospace applications include: the stability of microchannels and stationary phases under conditions of long-term radiation and thermal cycling; the reliability of chip-scale structures under launch vibration and mechanical shock loads; the hermeticity and material compatibility of packaging and interfaces in vacuum environments; and the synergistic integration of the micro chromatography system with spacecraft power, thermal control, and data sub-systems. These factors often determine whether a system can successfully transition from a laboratory environment to an actual aerospace mission.

Therefore, regarding aerospace applications, the further development of MEMS µGC technology depends not only on enhancements in separation performance and system miniaturization but also requires the conduct of systematic validation research regarding engineering reliability, environmental adaptability, and long-term operational stability. By combining ground-based environmental simulation testing, engineering-grade system integration, and the gradual elevation of TRL, MEMS µGC technology is poised to achieve actual deployment in future aerospace environmental monitoring and life support systems.

7. Challenges and Future Directions

7.1. Key Technical Challenges in Aerospace Applications