Abstract

Surface defect evaluation in steel production demands both high inference speed and accuracy for efficient production. However, existing methods face two critical challenges: (1) the diverse dimensions and irregular morphologies of surface defects reduce detection accuracy, and (2) computationally intensive feature extraction slows inference. In response to these challenges, this study proposes an innovative network based on dual-branch feature enhancement and downsampling (DFED-Net). First, an atrous convolution and multi-scale dilated attention fusion module (AMFM) is developed, incorporating local–global feature representation. By emphasizing local details and global semantics, the module suppresses noise interference and enhances the capability of the model to separate small-object features from complex backgrounds. Additionally, a dual-branch downsampling module (DBDM) is developed to preserve the fine details related to scale that are typically lost during downsampling. The DBDM efficiently fuses semantic and detailed information, improving consistency across feature maps at different scales. A lightweight dynamic upsampling (DySample) is introduced to supplant traditional fixed methods with a learnable, adaptive approach, which retains critical feature information more flexibly while reducing redundant computation. Experimental evaluation shows a mean average precision (mAP) of 81.5% on the Northeastern University surface defect detection (NEU-DET) dataset, a 5.2% increase compared to the baseline, while maintaining a real-time inference speed of 120 FPS compared to the 118 FPS of the baseline. The proposed DFED-Net provides strong support for the development of automated visual inspection systems for detecting defects on steel surfaces.

1. Introduction

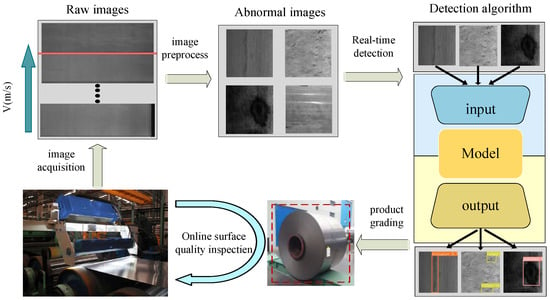

Steel is a significant industrial commodity, serving as an indispensable raw material in a multitude of fields, notably automotive, machinery manufacturing, and construction [1]. The implementation of rigorous quality monitoring measures in steel production is essential for enhancing the level of the final product [2]. Manual defect detection is a slow process whose results are highly dependent on human judgment. With the advancement of industrial automation and intelligence, inspection methods dependent on human labor are gradually being replaced by more efficient technological solutions [3]. A methodology that integrates classical image processing with machine learning is frequently employed to discern characteristics such as edge contours, texture details, and grayscale variations indicative of defects. However, these methods rely heavily on expert-defined features [4], which are often shallow and lack robustness under complex industrial conditions, leading to unreliable measurement outcomes [5]. As a result, conventional methodologies struggle to deliver consistent and deployable performance in real-world steel production environments, where defects exhibit diverse morphologies, multi-scale appearances, and low contrast [6]. In recent years, deep learning has been widely adopted in industrial inspection, particularly for automated visual inspection (AVI) of steel surface defects to ensure product quality [7]. Figure 1 concisely illustrates an AVI system wherein surface images are captured, processed in real time by deep learning models for defect detection, and assessed for automated decision-making—a performance entirely contingent on the model’s accuracy, speed, and robustness.

Figure 1.

A typical real-time AVI system.

Deep learning defect detection methods can be categorized based on task paradigms into object detection and semantic segmentation. Semantic segmentation methods, which require pixel-level annotation, demand precise labeling of every defective pixel in an image. The process of labeling is typically time-consuming and incurs high labor costs [8]. In contrast, bounding box-based object detection demonstrates higher efficiency and cost advantages. Previous studies have shown that multiple object detection frameworks can achieve excellent performance in this task. For example, one approach integrates deformable convolution with an attention mechanism to enhance feature extraction capability [9]; a lightweight adaptive activation convolutional network has been developed for real-time defect detection [10]; furthermore, a novel model achieves favorable results in steel defect detection by incorporating a global attention mechanism and a cascaded fusion network architecture [11].

Although existing methods have achieved significant results in terms of either precision or speed for detecting surface defects in steel, several critical challenges persist. First, the diversity and complexity of defect textures present a significant challenge. Steel surface defects exhibit high morphological variability, and defects of the same category may display markedly different structural characteristics [12]. Conventional convolution operations, constrained by fixed kernel sizes and limited receptive fields, struggle to adequately model complex texture differences between defects and background [13]. Secondly, significant differences in defect scale further increase detection difficulty. In convolutional neural networks, the feature extraction process gradually reduces the spatial fidelity of features. As a result, the response signals from small defects in shallow layers are likely to attenuate when propagating to deeper layers, impairing the detection accuracy [14]. Finally, the trade-off between detection efficiency and accuracy is particularly prominent in practical industrial applications. Achieving high recognition accuracy while meeting the timeliness demands of high-speed production lines remains a core challenge.

In response to these issues, this study develops a dual-branch feature enhancement and downsampling network (DFED-Net) for real-time steel surface defect inspection. The primary objective of this work is to reconcile the critical conflict between high-accuracy detection of diverse, subtle defects and the demand for real-time inference speed in production environments. The key contributions include:

- Building upon the efficient YOLOv8 framework, we integrate two novel modules: the Atrous convolution and Multi-scale Dilated Attention Fusion Module (AMFM) for robust feature representation against complex backgrounds, and the lightweight DySample for efficient upsampling.

- We propose the dual-branch downsampling as a general design principle for scale reduction in CNNs. Unlike conventional strided convolution, which inevitably discards information, this principle advocates for the explicit preservation and fusion of multi-level features during downsampling. The implemented dual-branch downsampling module (DBDM) is one concrete instantiation of this principle.

- The proposed DFED-Net establishes a new state-of-the-art balance between accuracy and speed on standard steel defect benchmarks, demonstrating the effectiveness of the above conceptual and architectural contributions in a demanding real-world application.

2. Related Works

2.1. Deep Learning-Based Defect Detection

Deep learning-based surface defect detection mainly falls into object detection and semantic segmentation. Semantic segmentation labels each pixel, providing precise defect contours, shapes, and boundaries, enabling flexible detection of irregular or multi-scale defects. Recently, various segmentation models have been adopted for defect detection tasks. For instance, lightweight fully convolutional networks (FCN) perform exceptionally well in time-sensitive scenarios [15]; the U-Net achieves superior performance in fine structure segmentation due to the encoder–decoder architecture and skip connection mechanism [16]; DeepLabv3 enhances the modeling of multi-scale contextual features by incorporating the atrous spatial pyramid pooling (ASPP) module [17]. Despite significant advancements in deep learning-based segmentation, these methods still face high computational complexity, heavy reliance on costly pixel-level annotations, susceptibility to class imbalance, and an inherent inability to distinguish between instances of the same class.

Object detection methods identify defects by localizing bounding boxes and are typically divided into two-stage and single-stage paradigms. Two-stage approaches, exemplified by region-based convolutional neural networks (R-CNN) [18] and Faster R-CNN [19], employ a cascaded pipeline: initially generating region proposals, followed by refinement of classification and regression. However, the two-stage nature gives rise to elevated computational costs and substantial model sizes, thus posing challenges for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices and failing to meet real-time requirements in industrial steel production.

Single-stage detectors directly classify objects and regress bounding boxes in a unified pass, bypassing region proposal generation. The design enables a simpler architecture and higher inference efficiency, making single-stage methods well-suited for real-time applications. For instance, a novel fusion attention network (FANet) has been proposed as a means of recognizing a range of steel defects [20]. Similarly, a novel model improves detection under complex industrial conditions by integrating dynamic channel attention with an optimized feature fusion strategy [21].

2.2. YOLO-Based Defect Detection

You only look once (YOLO) represents a series of one-stage object detection frameworks known for high efficiency. As an end-to-end model, YOLO performs feature extraction, spatial localization, and semantic classification in a single forward pass, enabling quick inference suitable for industrial real-time applications. Each cell in the grid representation of the input image is responsible for generating multiple bounding box proposals, accompanied by confidence estimates and class likelihoods. Multi-scale features are extracted through stacked convolutional layers and fed into detection heads to generate predictions. Final results are obtained via post-processing to eliminate duplicate detections.

The YOLO series has been a mainstream approach for defect detection because of the strong balance between accuracy and efficiency. For steel inspection, various YOLO-based improvements have been proposed. One efficient network restructures the spatial pyramid pooling (SPP) and integrates a global feature aggregation and redistribution (GFAR) module, enhancing multi-scale feature representation [22]. To improve small defect detection, another study introduces an attention-embedded feature transformation module that optimizes feature fusion and mitigates loss of local details and spatial information in deep networks [23]. Additionally, MPA-YOLO, built on YOLOv8, proposes a multi-path convolutional attention (MPCA) module to strengthen cross-channel and spatial responsiveness, improving defect feature extraction and discrimination under complex industrial conditions [24].

The existing works have advanced steel defect detection, yet prevailing methods face pronounced limitations when subjected to the core industrial triad of real-time speed, detection of small, low-contrast defects, and complex backgrounds. Specifically, advanced attention and fusion modules often compromise speed or dilute local details; standard downsampling loses fine spatial information irreversibly; and upsampling methods trade accuracy for efficiency. To address these interrelated constraints, we propose DFED-Net: an AMFM for efficient local–global feature enhancement, a DBDM principle to preserve spatial details across scales, and a lightweight DySample for accurate yet efficient upsampling.

3. Materials and Methods

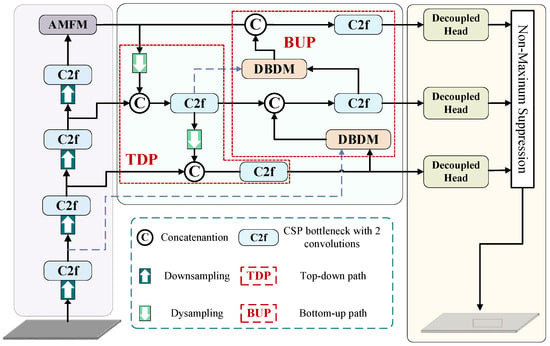

The overall architecture of the proposed DFED-Net is illustrated in Figure 2. The network is built upon the YOLOv8 framework, comprising three core components: the AMFM replaces the original Spatial Pyramid Pooling—Fast (SPPF) module in the backbone network; the DBDM is integrated into the feature pyramid network (FPN) path; the DySample modules replace the traditional upsampling operations in the neck. The interaction is sequential and complementary: AMFM provides high-quality, context-aware features; DBDM carefully downsamples these features while preserving detail; and DySample efficiently upsamples them to recover precise spatial localization for the detection heads. This co-design ensures that both semantic richness and spatial accuracy are maintained throughout the network, enabling precise and fast detection.

Figure 2.

Architecture of DFED-Net.

3.1. YOLOv8 Overview

The YOLOv8 marks a major evolution in the YOLO family, incorporating novel features and enhancements that collectively enhance performance and adaptability. Firstly, the cross-stage partial (CSP) [25] bottleneck with 2 convolutions (C2f) module is introduced as a replacement for the CSP module of the YOLOv5 model; in the neck, YOLOv8 builds upon the PANet feature extraction concept introduced in YOLOv5, thereby facilitating the comprehensive integration of multi-scale information, and removes the original convolutional structure in the upsampling process; in the detection head structure, the decoupled head of YOLOv8 no longer employs the same convolution for sharing parameters between classification and regression tasks. In addition, in contrast to the anchor-based methodology employed in earlier algorithms, YOLOv8 utilizes an anchor-free approach, thereby facilitating the detection of objects with irregular aspect ratios. Furthermore, the distribution focal loss (DFL) function facilitates the calculation of the regression loss, enabling the model to rapidly converge on areas near the target. The YOLOv8 is classified into 5 categories based on size. In this work, the smallest YOLOv8n is utilized as the baseline due to the excellent balance between computational efficiency and detection accuracy, which makes it particularly suitable for edge deployment in industrial inspection.

3.2. AMFM

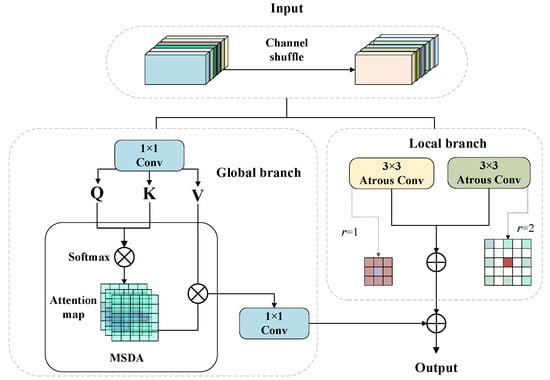

Convolutions are limited in modeling the global context for steel defects because of fixed receptive fields that lack scale adaptability. In contrast, attention mechanisms excel at capturing global semantics and long-range dependencies. The synergistic integration of convolutions and attention mechanisms enables simultaneous local feature extraction and global contextual understanding [26]. This study proposes the atrous convolution and multi-scale dilated attention fusion module (AMFM), which adopts a dual-branch architecture, to replace SPPF. The local pathway utilizes atrous convolutions at multiple dilation rates, enabling effective extraction of multi-scale context at minimal computational cost. The global branch introduces a multi-scale dilated attention (MSDA) mechanism to learn non-local interactions [27]. The collaborative integration of the two branches enables effective fusion of local details and global semantics, thereby strengthening perceptual accuracy and discriminative performance in complex scenes.

The input, illustrated in Figure 3, is first reshuffled via a channel shuffle operation to enhance cross-group channel interaction. The reorganized features are then processed in parallel by the local and global branches to promote multi-scale feature representation.

Figure 3.

Architecture of AMFM.

In the local branch, an enhanced feature representation is produced by summing the outputs from two parallel 3 × 3 atrous convolutions. Multi-scale receptive fields are achieved without additional parameters, enabling expanded contextual coverage while preserving spatial resolution. Capture of diverse local contexts proceeds without loss of spatial detail. The structure is formalized in Equation (1).

where denotes local branch output, refer to the output from the atrous convolution paths, refer to branch input features, and denote positional information, indicates the dilation rate, and signifies the weights.

In the global branch, Q (query matrix), K (key matrix), and V (value matrix) are first generated by applying a 1 × 1 convolutional layer, denoted as. , to the input , as formulated in Equation (4). These matrices are then fed into the MSDA mechanism, as shown in Equation (5), where refer to the attention-enhanced feature map. Finally, as per Equation (3), another 1 × 1 convolution is applied to to integrate the features and produce the global branch output .

Finally, a comprehensive feature representation is achieved through the AMFM, which integrates the local and global branch outputs. The output computation is expressed in Equation (6):

3.3. DBDM

In convolutional neural networks, downsampling progressively reduces feature map resolution to expand receptive fields and extract high-level semantics, while inevitably leading to the loss of low-level details and spatial structural information. For industrial images containing small defects or complex textures, in which discriminative features are closely tied to fine-grained local patterns, such degradation of spatial fidelity can significantly impair model performance.

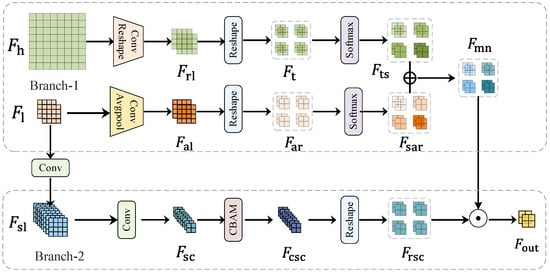

Conventional downsampling loses fine details irreversibly. DBDM rethinks this process as a detail-preserving fusion of information from two levels: the current feature map and a higher-resolution, shallower feature map . As shown in Figure 4, DBDM operates via two complementary branches:

Figure 4.

Architecture of DBDM.

Branch-1: Downsample and fuse and to propagate detailed spatial information forward.

Branch-2: Processes to generate guidance for selecting and fusing the important details from the first branch.

The outputs of both branches are fused to produce a downsampled feature map that retains both semantic strength and spatial richness, crucial for detecting small defects.

The first branch achieves detail-preserving by fusing upper-level and current-level features to generate lower-level feature maps containing detailed information from both levels. The process involves the following steps: First, the upper-level feature is reshaped to for spatial alignment. Subsequently, a convolutional layer reduces the channel count by half, yielding a pseudo-current-level feature . Next, a second reshape operation downsamples spatially to produce a pseudo-lower-level , reconstructed from the detailed information of the upper-level feature. Finally, the Softmax normalization is applied along the final dimension to obtain the normalized output . The current-level feature is first processed via average pooling, followed by a convolution to yield . Subsequently, a Reshape operation is applied to perform downsampling, generating a downsampled feature . Softmax normalization along the final dimension produces . Finally, and are element-wise summed to generate the first branch output , which integrates detailed information from both the upper-level and current-level feature maps.

The second branch employs an improved convolutional downsampling method. First, the current-level feature map undergoes a stride of 1 convolution to preserve spatial information, producing . A subsequent stride of 2 convolution downsamples F_sl generating with rich spatial details. The convolutional block attention module (CBAM) [28] is then applied to F_sc, yielding the enhanced feature map . Finally, a reshape operation restores the original spatial structure, producing the output , an enriched lower-level feature representation with preserved spatial information.

The outputs of the two downsampling branches are fused through element-wise multiplication, which is expressed as:

3.4. DySample

In steel defect detection, the upsampling module is critical for recovering boundary details and object shapes from low-resolution features. Conventional methods such as nearest-neighbor interpolation depend only on pixel coordinates and neglect semantic content, limiting detail reconstruction in complex scenes. While recent approaches improve feature modeling via dynamically generated kernels [29], these approaches incur high computational cost and parameter overhead because of dynamic convolutions and auxiliary subnetworks. To address these limitations, this study adopts DySample [30], a dynamic, point-based upsampling module, instead of conventional upsampling operations.

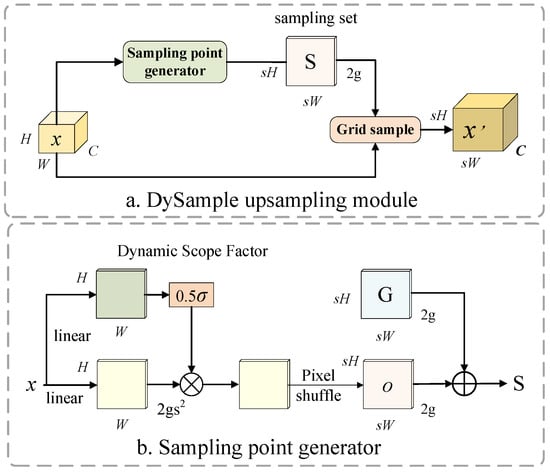

The DySample introduces the concept of a sampling point generator as a replacement for the computation method of dynamic convolution, thereby reconstructing the upsampling procedure through point sampling operations. Figure 5a shows the design of the DySample. Given a feature map and a sampling set , the sampling function (grid sample) resamples the given bilinear interpolation of utilizing positions specified in S, yielding the upsampled output .

Figure 5.

Architecture of DySample upsampling network.

The generation process of the sampling set S is shown in Figure 5b, obtained by adding the initial sampling grid and the generated offset . The initial sampling grid is dynamically generated based on the resolution of the input feature map and the upsampling factor, serving to calibrate the default positions of target pixels after upsampling. The generation of is achieved through linear mapping and pixel reorganization. First, the linear mapping calculates point-by-point positional offsets for the input features while introducing a scope factor to constrain the offsets, preventing excessive dispersion or overlap in the sampling point distribution. Subsequently, the offset values are rearranged through a pixel shuffling operation, adjusting their resolution to match the initial sampling grid, ultimately generating the dynamic offset values. The point sampling design preserves more detail by directly utilizing raw pixel values while reducing computational overhead.

Therefore, DySample is designed to be critical for both accuracy and efficiency, providing superior reconstruction quality over fixed interpolation while maintaining significantly lower computational cost than dynamic convolution-based upsamplers like Content-Aware ReAssembly of FEatures (CARAFE), making it ideal for real-time industrial deployment.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Dataset Introduction

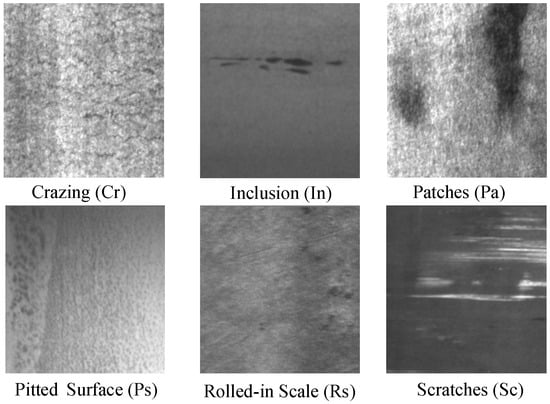

To evaluate the proposed DFED-Net for industrial steel surface defect measurement, we conduct experiments on the Northeastern University Surface Defect Detection (NEU-DET) [31]. The dataset comprises 1800 grayscale images captured under controlled production-line conditions, covering six common defect types: crazing, inclusion, patches, pitted surface, rolled-in scale, and scratches. Each class contains 300 samples, with high intra-class variability in shape, scale, and contrast, reflecting real-world challenges in steel quality control. Example images are shown in Figure 6. To assess cross-dataset generalization capability, we further evaluate the model on the GC10-DET dataset [32]. The GC10-DET dataset consists of 2280 preprocessed defect images sourced from real industrial settings, covering 10 distinct categories of steel surface defects following manual screening. Both datasets are divided into training, validation, and test sets in an 8:1:1 ratio.

Figure 6.

Dataset examples of NEU-DET.

4.2. Experimental Setup

Experimental settings are summarized in Table 1. Additionally, input images are resized to 640 × 640, with a batch size of 8, 8 workers, an initial learning rate of 0.01, momentum of 0.937, and weight decay of 5 × 10−4. Training runs for 300 epochs using SGD with cosine annealing. Exponential Moving Average (EMA) is applied with a decay rate of 0.999 to stabilize training and enhance final performance. The loss function combines CIoU, binary cross-entropy, and distribution focal loss. Mosaic augmentation (probability = 1.0) is disabled in the last 10 epochs. Inference uses NMS with a confidence threshold of 0.5 and an IoU threshold of 0.7, and FPS is measured end-to-end, including NMS.

Table 1.

Experimental configuration.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively verify the performance of DFED-Net, among the metrics employed in this evaluation are mean average precision (mAP), which assesses the detection accuracy of models; floating point operations (FLOPs) and parameters, which evaluate the lightweight nature of models; and frames per second (FPS), which assesses the inference speed of models. The related metrics are calculated as follows:

where indicates that the positive sample has been classified as positive, while denotes that the negative sample has been classified as positive. Conversely, signifies that the positive sample has been classified as negative. signifies the number of categories.

4.4. Comparative Experiments

This study conducted multiple comparative experiments on NEU-DET to assess the architectural enhancements of DFED-Net. The specific results and analyses are as follows:

4.4.1. Comparative Study Between DFED-Net and YOLOv8

To assess the performance impact of the complete network design of DFED-Net, this study conducted comparative experiments against YOLOv8. Table 2 presents the detailed results. The mAP value for “All” is presented as mean ± standard deviation over three independent runs with different random seeds. Class-wise, APs are from a representative run.

Table 2.

Detection results for YOLOv8 and DFED-Net on NEU-DET.

As shown in Table 2, the DFED-Net outperforms YOLOv8 across all defect categories. Specifically, for Cr, the mAP of DFED-Net increases by 7.6 percentage points, demonstrating superior sensitivity to elongated and irregular structures. For In, Pa, Ps, and Sc, improvements of 4.7%, 2.9%, 2.7%, and 6.4% are observed, respectively, reflecting enhanced detection robustness across diverse defect geometries. Overall, the DFED-Net achieves an mAP of 81.5%, which is 5.2% higher than YOLOv8, confirming the superiority in comprehensive detection performance.

The DFED-Net contains 3.2 million parameters and 8.6 GFLOPs, representing a marginal increase over YOLOv8. However, the modest augmentation in resource allocation yields substantial performance enhancements, underscoring an optimal equilibrium between accuracy and efficiency. The incremental resource demand remains within acceptable limits for edge deployment, particularly given the improved detection reliability. Moreover, the DFED-Net maintains a real-time inference speed of 120 FPS, comparable to YOLOv8, indicating that the proposed modules enhance feature representation without introducing substantial computational bottlenecks.

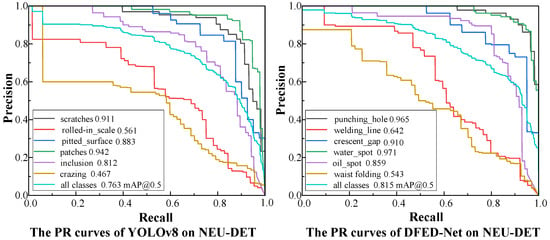

The PR curves of the baseline and DFED-Net are compared in Figure 7. The PR curve of DFED-Net consistently lies above that of the baseline and closer to the top-right corner, indicating a superior balance between precision and recall across defect detection tasks. Specifically, at high recall rates (e.g., >0.8), DFED-Net exhibits significantly higher precision, meaning it generates fewer false positives when attempting to detect most true defects. Conversely, at elevated precision levels, DFED-Net attains enhanced recall, signifying it omits fewer genuine defects under stringent confidence thresholds.

Figure 7.

Precision–Recall analysis of YOLOv8 and DFED-Net on NEU-DET.

4.4.2. Comparative Study Between DFED-Net and Object Detection Models

To further evaluate DFED-Net, a comparison among state-of-the-art object detection algorithms is carried out under a consistent data partitioning scheme and identical experimental configurations. The algorithms selected for comparison include Faster R-CNN, SSD [33], Real-Time Detection Transformer (RT-DETR) [34], and various versions of the YOLO model [35].

As demonstrated in Table 3, the proposed model exhibits the highest overall performance among all compared methods, with an mAP of 81.5%. The DFED-Net surpasses YOLOv11, the second-best model, by 2.9 percentage points and outperforms YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 by 3.8 and 5.2 percentage points, respectively, demonstrating superior feature representation and detection robustness. Although SSD offers higher inference speeds, the detection accuracy is significantly low, limiting the application in high-reliability industrial inspection. Conversely, DFED-Net attains a more optimal balance between accuracy and speed.

Table 3.

Experimental results compared with mainstream algorithms on NEU-DET. Bolded numbers indicate the best performance.

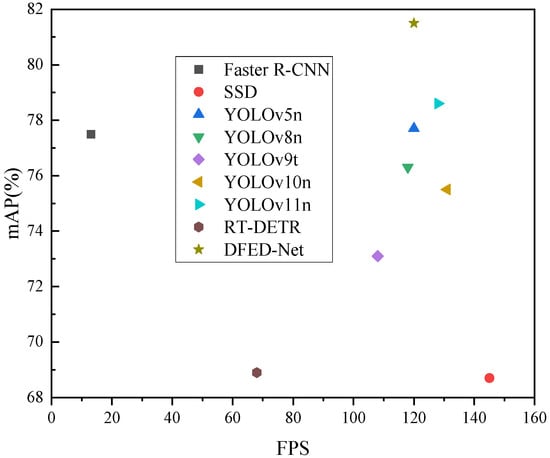

Figure 8 presents the FPS-mAP curve, where DFED-Net lies closer to the top-right region, demonstrating superior performance in both accuracy and speed.

Figure 8.

FPS-mAP curve of different models.

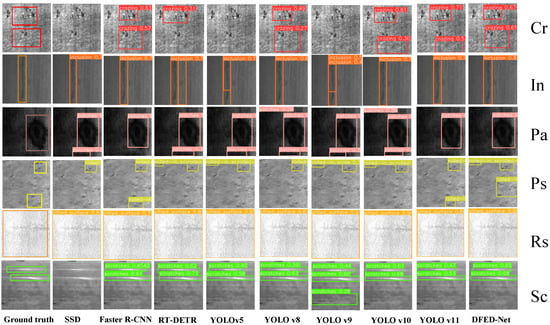

Additionally, a set of sample images exhibiting diverse defect types was randomly selected for comparative analysis, as shown in Figure 9. The visualization results demonstrate that DFED-Net achieves more accurate localization and identification of defects, with tighter bounding boxes and overall superior detection performance compared with other algorithms.

Figure 9.

Detection results of various models on NEU-DET.

4.4.3. Comparative Study Between DFED-Net and Steel Surface Defect Detection Models

The superiority of DFED-Net is validated through comparison with SOTA models in industrial inspection. The experimental outcomes are compiled in Table 4.

Table 4.

Detection results on the NEU-DET. Bolded numbers indicate the best performance.

Experimental results show that DFED-Net achieves SOTA performance on the NEU-DET benchmark, delivering an mAP of 81.5% at an inference speed of 120 frames per second. The model outperforms multiple advanced defect detection methods. The dual advantages in both accuracy and speed validate the effectiveness of DFED-Net in complex industrial environments, provide robust technical support for the detection of steel surface defects, and demonstrate strong potential for engineering applications.

4.5. Ablation Study

In this study, systematic ablation experiments were conducted on the NEU-DET dataset to evaluate the effectiveness of the three core improvement modules proposed in DFED-Net. Specifically, these experiments encompass the overall network architecture design, the contribution of the AMFM to local feature representation capabilities, and the role of DySample in efficient upsampling.

4.5.1. The Ablation Study of DFED-Net

To systematically assess the contribution of the three core innovations to the performance improvement of YOLOv8, this study conducts eight ablation studies on the NEU-DET dataset, with results summarized in Table 5. The specific analysis is as follows:

Table 5.

The ablation studies on NEU-DET.

(1) Integrating AMFM increases mAP to 79.3, validating the effectiveness in multi-scale feature extraction and contextual modeling, though computational cost rises and FPS drops to 108. (2) Incorporating DBDM raises mAP to 78.2%, indicating the benefit in preserving spatial details. However, structural complexity reduces FPS to 102 and increases FLOPs to 8.8 G, resulting in lower efficiency. (3) Employing DySample reduces computational cost and only marginally improves mAP to 76.5%, indicating the primary role in optimizing upsampling efficiency and quality rather than accuracy. (4) Combining AMFM and DBDM results in an mAP of 77.8%, lower than AMFM alone, with further degradation in speed, suggesting feature redundancy. (5) AMFM combined with DySample achieves 78.9% mAP at 125 FPS, demonstrating a favorable accuracy-efficiency trade-off and synergistic interaction, where DySample mitigates the inference burden introduced by AMFM. (6) The combination of DBDM and DySample achieves an mAP of 79.8% at 122 FPS, surpassing DBDM alone, balancing efficiency and accuracy. (7) The full DFED-Net model achieves the highest performance: 81.5% mAP at 120 FPS, with 3.2 M parameters and 8.6 G FLOPs. By combining local and global features, preserving low-level details, and enabling efficient upsampling, the architecture promotes deep feature integration, leading to substantial gains in detecting small and structurally intricate defects. Despite a slight complexity increase, real-time inference is maintained, confirming an optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency.

4.5.2. The Ablation Experiments of AMFM

This study evaluates the effectiveness of the AMFM within the DFED-Net framework by replacing AMFM with several mainstream attention modules. Table 6 summarizes the experimental outcomes.

Table 6.

Comparison of different attention performances in the DFED-Net framework.

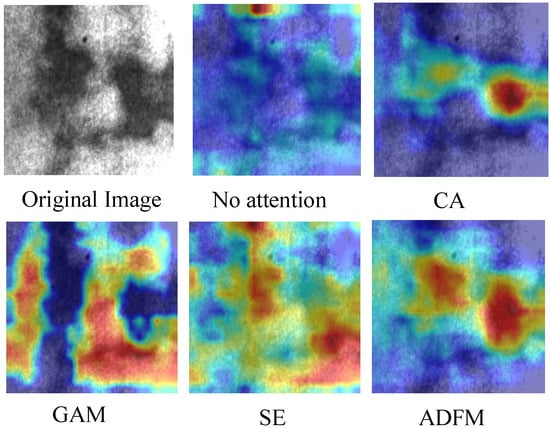

The findings indicate that AMFM achieves superior performance compared to existing attention mechanisms, demonstrating superior capability in global feature fusion and critical region enhancement. By integrating the large receptive field of dilated convolution with the feature selection ability of attention mechanisms, AMFM effectively focuses on fine defect structures, strengthening key feature representation while suppressing background noise. In comparison, global attention mechanism (GAM) and coordinate attention (CA) achieve only 77.8% and 78.4% mAP, respectively, with significantly reduced inference speed, indicating that the structural complexity introduces excessive computational overhead. Squeeze-and-excitation (SE) achieves accuracy comparable to no attention under low parameter counts and provides no substantial improvement, highlighting the limited representational capacity.

Figure 10 illustrates the feature activation maps under different modules. Diffuse responses occur in the absence of attention, primarily concentrated on image edges and background areas, with insufficient focus on defect regions. CA exhibits weak activation intensity and poor response to defect structures. SE and GAM are biased by bright textures, assigning high responses to non-defective regions. In contrast, AMFM achieves the strongest and most compact activation over defect regions, effectively suppressing background interference and yielding more discriminative feature representations. The enhanced focusing capability stems from the synergistic design of global feature fusion and key-region feature enhancement, enabling precise defect localization while reducing redundant computations. Compared to existing attention mechanisms, which are compromised by background distraction, scattered attention, or limited accuracy gain, AMFM demonstrates superior feature aggregation capability, confirming its effectiveness and suitability as the core module in DFED-Net.

Figure 10.

Visual comparison of feature map activations across different attention mechanisms.

4.5.3. The Ablation Experiments of DySample

To evaluate the effectiveness of DySample, this study conducted experiments using several different upsampling methods within the DFED-Net framework, including bilinear interpolation and CARAFE. Table 7 summarizes the experimental results.

Table 7.

Comparison of different upsampling performances in the DFED-Net framework. Bolded numbers indicate the best performance.

Compared to the default nearest-neighbor interpolation in YOLOv8, the bilinear interpolation method maintains the same number of parameters but leads to a decrease in FPS to 94 due to its higher computational complexity. Furthermore, a decline in mAP to 77.6% is observed, which is ascribed to the blurring effect on feature edges. CARAFE, as a representative content-aware upsampling approach, achieves an mAP of 78.8% by dynamically generating convolutional kernels, corresponding to an improvement of 1.0 percentage points over the baseline. However, this gain entails a substantial computational cost, reducing the inference speed by 20.4% to 78 FPS. In industrial defect detection scenarios that require high real-time performance, such a speed reduction is generally unacceptable. In contrast, the DySample method has been demonstrated to deliver substantial enhancements across all primary metrics, attaining the highest levels of accuracy while preserving the fastest possible inference speed. This outcome confirms that DySample combines exceptional feature reconstruction capability with high computational efficiency.

4.6. Generalization Validation of DFED-Net on the GC10-DET Dataset

The generalization ability of DFED-Net is further validated on the GC10-DET dataset, demonstrating consistent and robust performance across diverse industrial defect types, as summarized in Table 8. Compared with representative baselines, DFED-Net achieves a 3.5 percentage point improvement in overall mAP, reaching 75.3%, the highest among all evaluated methods. The gains are particularly pronounced on defect categories that are inherently challenging due to low contrast, irregular geometry, or subtle appearance, including rolled_pit, crease, inclusion, and oil spot. For instance, DFED-Net improves the average precision for crease by 9.4 points and for rolled_pit by 7.4 points over the baseline, reflecting the enhanced sensitivity to fine structural deformations and surface depressions.

Table 8.

Detection results on GC10-DET.

A slight performance reduction is observed in two high-accuracy categories: punching_hole and crescent_gap, where AP decreases by 0.8 points each relative to YOLOv8n. This minor degradation likely stems from the fact that these defects exhibit strong visual saliency and near-perfect detection rates even with simpler models.

Despite these negligible declines in already well-solved categories, DFED-Net consistently outperforms YOLOv5n, YOLOv9t, YOLOv10n, YOLOv11n, and YOLOv8n across the majority of defect types. These results highlight strong cross-domain transfer capability and effective capture of discriminative features under varying defect morphologies, which is a critical attribute for real-world instrumentation systems deployed across heterogeneous production lines.

5. Discussion

This work addresses key challenges in automated steel surface inspection, including the multi-scale nature of defects, low contrast against complex backgrounds, structural irregularity, and the trade-off between detection accuracy and real-time efficiency through the proposed DFED-Net. The experimental results presented demonstrate its superior performance. Compared to the baseline YOLOv8, DFED-Net achieves a significant 5.2% mAP improvement on the NEU-DET dataset while maintaining real-time speed. The DFED-Net also outperforms a wide range of state-of-the-art object detectors and specialized defect detection models, establishing a new balance point on the accuracy-efficiency frontier.

The performance gains can be attributed to the synergistic design of the three core innovations: (1) By fusing multi-scale local details with global context, AMFM learns to suppress background noise and amplify defect signatures, boosting precision on low-contrast defects. (2) The DBDM preserves fine spatial information across scales by mitigating detail loss during downsampling, thereby improving recall—especially for small defects. (3) The lightweight DySample reconstructs high-resolution features adaptively and efficiently, enabling accurate boundary recovery and tight bounding box regression without slowing inference. The ablation studies confirm the individual and combined efficacy of these components.

Despite the promising results, this work has certain limitations. First, the model’s performance, particularly on low-contrast defects like crazing (Cr) and rolled-in scale (Rs), while improved, still has room for enhancement. The complex texture of steel surfaces can sometimes overshadow subtle defect signatures. Second, the generalizability of DFED-Net, though validated on the NEU-DET and GC10-DET, is ultimately constrained by the scale and diversity of publicly available steel defect datasets. Performance in entirely new industrial environments with unseen defect types or imaging conditions remains to be fully tested.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents DFED-Net, a novel and efficient network for real-time steel surface defect detection. The model is built upon the YOLOv8 framework and integrates three key contributions: the AMFM for enhanced feature representation, the DBDM for detail-preserving scale reduction, and the lightweight DySample module for dynamic and efficient upsampling. Extensive experiments on the NEU-DET and GC10-DET benchmarks demonstrate that DFED-Net achieves state-of-the-art accuracy while maintaining high inference speed, demonstrating promising application prospects in real-time industrial inspection scenarios.

Building upon this research, future work will focus on the following areas: (1) Publicly available steel defect datasets remain limited in scale and diversity, potentially constraining model generalization. Future efforts will focus on establishing industry-academia collaborations to collect large-scale, multi-source datasets or leveraging advanced data augmentation and synthetic generation techniques to enhance training robustness. (2) To further improve performance on low-contrast defects, integrating advanced image preprocessing pipelines for contrast enhancement and noise reduction will be studied. (3) To facilitate deployment on even more resource-constrained edge devices, the application of model compression techniques such as pruning and quantization will be pursued to develop an ultra-lightweight variant of DFED-Net.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Y.; methodology, L.Y.; software, Q.L.; validation, M.G.; formal analysis, Q.L.; investigation, Q.L.; resources, L.Y.; data curation, Q.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.; writing—review and editing, L.Y.; visualization, M.G.; supervision, L.Y.; project administration, L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62463001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AMFM | Atrous convolution and sliding window dilated attention fusion module |

| CA | Coordinate attention |

| CBAM | Convolutional block attention module |

| CSP | Cross-stage partial |

| C2f | CSP bottleneck with 2 convolutions |

| DFL | Distribution focal loss |

| DL | Deep learning |

| DBDM | Dual-branch downsampling module |

| FCN | Fully convolutional networks |

| FPS | Frames per second |

| Faster | R-CNN: Faster region-based convolutional neural network |

| GAM | Global attention mechanism |

| mAP | Mean average precision |

| ML | Machine learning |

| P | Precision |

| R | Recall |

| RT-DETR | Real-time detection transformer |

| SE | Squeeze-and-excitation |

| YOLOv8 | You only look once v8 |

References

- Guclu, E.; Aydin, I.; Akin, E. Enhanced Defect Detection on Steel Surfaces Using Integrated Residual Refinement Module with Synthetic Data Augmentation. Measurement 2025, 250, 117136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Mi, T.; Feng, K.; Zhou, S.; Jiang, Z. DiffDD: A Surface Defect Detection Framework with Diffusion Probabilistic Model. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S.S.A.; Ohata, E.F.; Sousa, P.C.; Barroso, C.B.; Nascimento, N.M.M.; Loureiro, L.L.; Bittencourt, V.Z.; Capistrano, V.L.M.; da Rocha, A.R.; Filho, P.P.R. Sex-Based Approach to Estimate Human Body Fat Percentage from 2D Camera Images with Deep Learning and Machine Learning. Measurement 2023, 219, 113213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzammil, P.M.; Mishra, S.K.; Nandini, K.; Ahammad, S.H.; Inthiyaz, S.; Altahan, B.R.; Smirani, L.K.; Hossain, M.A.; Rashed, A.N.Z. Machine Learning Based Models for Defect Detection in Composites Inspected by Barker Coded Thermography: A Qualitative Analysis. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2023, 178, 103425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhong, Y.; Dian, S. Rethinking Unsupervised Texture Defect Detection Using PCA. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2023, 163, 107470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Gong, F.; Wang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Shi, Z. Pixel-Level Semantic Parsing in Complex Industrial Scenarios Using Large Vision-Language Models. Inf. Fusion 2025, 116, 102794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Xu, B.; Yin, H. A Survey of Deep Learning Approaches to Image Restoration. Neurocomputing 2022, 487, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, X. Soldering Defect Segmentation Method for PCB on Improved UNet. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Du, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, H. DCAM-Net: A Rapid Detection Network for Strip Steel Surface Defects Based on Deformable Convolution and Attention Mechanism. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 5005312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Lu, Z.; Xia, K.; Zuo, H.; Jia, X.; Li, H.; Xu, Y. LAACNet: Lightweight Adaptive Activation Convolution Network-Based Defect Detection on Polished Metal Surfaces. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chu, M.; Gong, R.; Zheng, Z. Global Attention Module and Cascade Fusion Network for Steel Surface Defect Detection. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 158, 110979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Li, G.; Liu, Z. Two-Stage Edge Reuse Network for Salient Object Detection of Strip Steel Surface Defects. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 5019812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makanda, I.L.D.; Jiang, P.; Yang, M.; Shi, H. Emergence of Collective Intelligence in Industrial Cyber-Physical-Social Systems for Collaborative Task Allocation and Defect Detection. Comput. Ind. 2023, 152, 104006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jiang, S.; Wang, X.; Sun, P.; Hua, C.; Sun, J. An Efficient Detector for Detecting Surface Defects on Cold-Rolled Steel Strips. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 138, 109325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, I.F.S.; Silva, A.C.; de Paiva, A.C.; Gattass, M.; Cunha, A.M. A Multi-Stage Automatic Method Based on a Combination of Fully Convolutional Networks for Cardiac Segmentation in Short-Axis MRI. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Du, B.; Xu, Y. Shape-Intensity-Guided U-Net for Medical Image Segmentation. Neurocomputing 2024, 610, 128534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaowei, W.; Jiangbo, X.; Xiong, W.; Jiajun, Z.; Zixuan, Z.; Xinyu, C. Concrete Crack Recognition and Geometric Parameter Evaluation Based on Deep Learning. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2025, 199, 103800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, C.-C.; Lam, K.-M. Efficient Fused-Attention Model for Steel Surface Defect Detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 2510011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Yu, J. RetinaNet with Difference Channel Attention and Adaptively Spatial Feature Fusion for Steel Surface Defect Detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 2503911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Zou, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W. Metallic Surface Defect Recognition Network Based on Global Feature Aggregation and Dual Context Decoupled Head. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 158, 111589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Q.; Han, Y.; Zhao, M. DsP-YOLO: An Anchor-Free Network with DsPAN for Small Object Detection of Multiscale Defects. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 241, 122669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Z. MPA-YOLO: Steel Surface Defect Detection Based on Improved YOLOv8 Framework. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 168, 111897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M.; Wu, Y.H.; Chen, P.Y.; Hsieh, J.W.; Yeh, I.H. CSPNet: A New Backbone That Can Enhance Learning Capability of CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Gao, F.; Zhou, X.; Dong, J.; Du, Q. Hybrid Convolutional and Attention Network for Hyperspectral Image Denoising. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 5504005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Tang, Y.-M.; Lin, K.-Y.; Gao, Y.; Ma, A.J.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, W.-S. DilateFormer: Multi-Scale Dilated Transformer for Visual Recognition. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 8906–8919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praharsha, C.H.; Poulose, A. CBAM VGG16: An Efficient Driver Distraction Classification Using CBAM Embedded VGG16 Architecture. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 180, 108945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Xu, R.; Liu, Z.; Loy, C.C.; Lin, D. CARAFE: Content-Aware ReAssembly of FEatures. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Lu, H.; Fu, H.; Cao, Z. Learning to Upsample by Learning to Sample. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Song, K.; Meng, Q.; Yan, Y. An End-to-End Steel Surface Defect Detection Approach via Fusing Multiple Hierarchical Features. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 1493–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Duan, F.; Jiang, J.; Fu, X.; Gan, L. Deep Metallic Surface Defect Detection: The New Benchmark and Detection Network. Sensors 2020, 20, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; An, E.-J.; Kim, S.; Sri Preethaa, K.R.; Lee, D.-E.; Lukacs, R.R. SRGAN-Enhanced Unsafe Operation Detection and Classification of Heavy Construction Machinery Using Cascade Learning. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, R.; Zhao, T.; Wei, B.; Peng, B.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X. Mechanical Fault Diagnosis of On-Load Tap Changers Using Time–Frequency Vibration Analysis and a Lightweight YOLO Model. Measurement 2025, 256, 118441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Jia, M. DCC-CenterNet: A Rapid Detection Method for Steel Surface Defects. Measurement 2022, 187, 110211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Jiang, C.; Liang, T. REDef-DETR: Real-Time and Efficient DETR for Industrial Surface Defect Detection. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 105411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.