Abstract

Heavy metals are major toxic anthropogenic contaminants released into the environment mainly through wastewater discharges. Adsorption is one of the most effective and widely applied methods for their removal from aqueous systems. However, although activated carbon is commonly used, its high cost and limited regenerability motivate the search for cheaper and more environmentally friendly alternatives. In this study, selected natural and waste-derived materials were evaluated for Cu2+ removal from both model solutions and atypical textile wastewater. Coffee grounds, chestnut seeds, acorns, potato peels, eggshells, marine shells, and poultry bones were tested and compared with commercial activated carbon. Their structural and functional properties were characterised using specific surface area measurements, optical microscopy, SEM-EDS, and FTIR analyses. Two adsorption isotherm models (Langmuir and Freundlich) were used to analyse the experimental data for the selected adsorbents, and model parameters were determined by linear regression. Based on model solution tests, two materials showed the highest Cu2+ sorption potential: coarse poultry bones (97.0% at 24 h) and fine cockle shells (96.2% at 24 h). When applied to real textile wastewater, the bone-derived material achieved the highest Cu2+ removal efficiency (79.4%). Although this efficiency is lower than typical values obtained in laboratory solutions, it demonstrates the feasibility of waste-derived materials as low-cost adsorbents and suggests that further optimisation could further improve their performance.

1. Introduction

The dynamic growth of the global population and industrial expansion are reducing drinking water resources, which are fundamental for life and the economy [1,2,3]. Water use generates multiple wastewater streams, and in Poland alone, 137.9 hm3 of untreated wastewater was discharged into the environment in 2022 [4] The composition of wastewater depends on the industrial process that generates it [5].

Among pollutants introduced via wastewater, heavy metals are particularly harmful [6,7] due to their high persistence [8], non-biodegradability, and strong bioaccumulation potential [9,10]. Their accumulation in soil reduces enzymatic activity, deteriorates soil quality, and negatively affects plant growth and biodiversity [11], while phytotoxicity includes growth inhibition and chlorosis [6]. Metals also bioaccumulate across trophic levels, reaching the highest concentrations in predators, including humans [10], where they can damage multiple organ systems and exhibit carcinogenic and mutagenic effects [12,13].

According to toxicity, heavy metals are classified into four groups: very high risk (Cd, Hg, Pb, Cu, Zn), high risk (Mo, Mn, Fe), moderate risk (Ni, Co), and low risk (Sr, Zr) [12]. They originate both from natural processes such as rock weathering and volcanism [14], and from anthropogenic sources, the latter being dominant [14,15]. Industrial wastewater from sectors such as pharmaceuticals, chemicals, leather processing, metallurgy, mining, and textiles constitutes a major pathway for metal release [7,8,16].

Copper(II) is one of the key contaminants of concern among heavy metals present in industrial effluents [17]. While copper plays an important biological role as a micronutrient, its elevated concentrations in aquatic environments can lead to severe metabolic disturbances and organ damage [18,19]. Elevated copper levels may also negatively affect male fertility as well as increase the risk of genetic disorders [20,21,22].

The contamination of water resources worldwide with copper is becoming an increasingly serious problem and poses a major threat to human health and aquatic ecosystems [23]. Numerous technologies have been developed and applied for the removal of copper from aqueous environments. This involves physicochemical methods such as membrane separation, ion exchange, chemical precipitation, electrochemistry, and adsorption, as well as biological approaches such as biosorption, bioprecipitation, and biomineralisation [7,24,25,26]. In the case of membrane techniques, polymer-enhanced ultrafiltration can achieve Cu2+ removal up to 97% [27]. Nanofiltration has proven particularly effective for copper separation, with reported removal efficiencies exceeding 96–98% for composite membranes [28,29,30]. Therefore, membrane separation has been recognised as a promising approach for Cu 2+ removal from aqueous solutions, due to the relative simplicity of system design and operation, as well as the possibility of recovering valuable metals. Nevertheless, limitations such as high operating pressures, sensitivity to pH and interference from competing ions can restrict its practical application [31,32,33]. Some studies have confirmed that reverse osmosis membranes are highly effective in removing Cu(II), particularly under high contamination loads and in the presence of coexisting ions [23,34]. Despite the availability of various advanced treatment methods, including advanced oxidation, electrochemical processes, flotation and membrane techniques [35], their practical application is often limited by high operational costs and process complexity.

One of the most widely applied methods for heavy metal removal from water is adsorption [36,37], due to its high efficiency, operational simplicity and relatively low cost [37,38].

Adsorption consists of three stages: transport from solution to the surface, attachment to the surface, and intraparticle diffusion [35,39].

Therefore, adsorption has become one of the most widely applied techniques for treating wastewater contaminated with heavy metals [36,37], owing to its high removal efficiency, operational simplicity, and relatively low cost [37,38].

The proper selection of the adsorbent is crucial in the adsorption process; its most important characteristics include: specific surface area, structure, and the chemical nature of the surface [38]. Various adsorbents, such as activated carbon, zeolite, activated alumina, lignite coke, bentonite, ash, clay, and natural fibres, were used to remove heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions [40,41,42,43]. Activated carbon is currently the most widely used adsorbent. Its broad applicability results from its well-developed porous structure, high specific surface area, and abundance of surface functional groups—features that also enable the removal of trace concentrations of heavy metals [38,44].

Literature reports indicate that activated carbon can be produced from various natural or waste-derived precursor materials, including olive branches [45], leather waste [46], orange peels [47], potato peels [48], sewage sludge, and kitchen waste [44]. However, due to the high costs of production and regeneration of activated carbon [38], new, more environmentally friendly solutions are being searched. Ideally, the adsorption process should be simple, highly efficient, environmentally friendly, and inexpensive [49].

Currently, efforts are focused on enabling the direct use of selected materials as adsorbents. One promising solution is plant-based biomass; the literature documents the use of various plant parts—including leaves, stems, peels, seeds, and roots—for this purpose [50]. Reported examples include stems of Jerusalem artichoke [51], rice husks [52], durian leaves [53], and sunflower husks [53]. Fruit peels have also been widely investigated, such as apple [54,55], watermelon [56,57], banana [58], orange [55], lemon [55], grapefruit [55], and mango peels [59]. In addition, several waste materials have been explored, including eggshells [49], modified apple pomace [60,61], ginger waste [62], and tea leaves [63,64].

The aim of this study was to assess the applicability of selected natural and waste-derived materials for the removal of copper ions from atypical textile wastewater. Coffee grounds, chestnut seeds, acorns, potato peels, eggshells, marine shells, poultry bones and commercially available activated carbon were employed as adsorbents. These materials represent widely available and low-cost resources, potentially offering an economically viable alternative to conventional adsorbents. Their specific surface area, surface morphology, chemical structure (FTIR) and elemental composition (SEM–EDS) were analysed, and their Cu2+ adsorption performance was evaluated. The utilisation of natural or waste-based materials is consistent with circular economy principles, supporting the development of sustainable adsorption technologies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Adsorbents were prepared from natural and waste materials such as potato peels, horse chestnut seeds (Aesculus hippocastanum), oak acorns (Quercus robur), chicken eggshells, common cockle shells (Cerastoderma glaucum), chicken bones, and coffee grounds. A commercially available adsorbent from ABC-Z System EKO (Katowice, Poland) was used as a reference sample. All natural and waste materials were washed with distilled water and dried at 105 °C for 24 h using an Elkon drying oven (Lodz, Poland) to remove moisture from the samples. The dried materials were then ground using a Łucznik grinder (Wroclaw, Poland) and sieved into particle-size fractions: fine (<1 mm) and coarse (1–3 mm).

Two aqueous matrices were used: (i) a copper standard solution (≈10 mg L−1 Cu, pH 3) prepared from a certified copper standard (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany); and (ii) real textile wastewater originating from the copper fibre cladding process at the Experimental Production facility of the Lukasiewicz Research Network–Lodz Institute of Technology (Lodz, Poland). Actual wastewater may contain detergents and softeners, which potentially compete for adsorption sites on the surface of the material, affecting the efficiency of the process. The presence of such compounds is typical for industrial wastewater; therefore, their inclusion allows for a better reflection of the actual operating conditions of the adsorbent. The characteristics of the actual wastewater used are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of actual wastewater.

2.2. Methods

Specific surface area and porosity measurements were performed using an Autosorb-1 analyser Quantochrome Instruments (Boynton Beach, FL, USA), employing the physical sorption method with nitrogen at a temperature of 77 K. The specific surface area was determined using the 5-point SBET method, covering a relative pressure range of P/P0 from 0.10 to 0.30. The measurement was performed twice on the same specimen: first using a 5-point adsorption isotherm and second using a detailed 39-point adsorption–desorption isotherm. Both measurements were performed on the same sample of the tested material.

Surface morphology was examined by optical microscopy using a Keyence VHX-7000 N digital microscope (Osaka, Japan).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the adsorbents was performed using a Phenom ProX G6 scanning electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The imaging was carried out under low-vacuum conditions (60 Pa) with an accelerating voltage of 15 keV. A backscattered electron detector (BSD) was used, and images were acquired at a magnification of 1250×. The elemental composition of the samples was qualitatively examined using an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) system from Oxford Instruments (Abingdon, UK).

The degree of copper (Cu) ion adsorption by the tested adsorbents was assessed. A specified mass of adsorbent (from 1 to 2 g) was placed in a liquid (100 mL) with a known concentration of copper ions—amounting to 10 mg/L for model wastewater and 4.2 mg/L for actual wastewater. At selected time intervals, samples were taken, and the content of these ions was determined again. The analysis of Cu ion content was performed using Hach Lange cuvette tests (LCK329) and a dedicated DR 3900 Hach Lange spectrophotometer (Düsseldorf, Germany). The degree of Cu ion adsorption on the tested adsorbents was determined based on the loss of Cu ions in the solution, calculated from the difference in concentrations before and after contact with the adsorbent. The process was carried out at room temperature, approximately 23 °C, with continuous stirring using a Heidolph MR Hei-Tec stirrer (Schwabach, Germany) at a speed of 500 rpm. Each marking was performed at least twice to ensure the reliability and repeatability of the results obtained.

The chemical structure of the surface of selected adsorbents was evaluated by the ATR-FTIR method in the range of 4000–400 cm−1, using a JASCO FT/IR-4200 spectrometer (JASCO Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a GladiATRTM ATR attachment (PIKE Technologies, Madison, WI, USA).

2.3. Description of Mathematical Models

To describe the equilibrium behaviour of metal ion adsorption on the tested materials, two commonly used isotherm models were selected: Langmuir and Freundlich.

The Langmuir model assumes that the surface of the adsorbent has a specific number of active sites capable of binding adsorbed molecules through physical (van der Waals forces) or chemical interactions. The model is based on the assumption that adsorption leads to the formation of a homogeneous monolayer of molecules on the surface of the adsorbent, and that there are no interactions between the adsorbed molecules [65,66,67,68].

The Langmuir isotherm in its nonlinear form is given by the following equation:

The equation can also be arranged into a linear form:

where

- qe—amount of adsorbed substance per unit mass of adsorbent [mg/g];

- Qm—maximum monolayer capacity [mg/g];

- KL—Langmuir constant [L/mg];

- Ce—concentration in the liquid phase at equilibrium [mg/L].

The Freundlich model assumes that chemical equilibrium is achieved because of dynamic exchange between adsorbed molecules and those remaining in solution. The surface of the adsorbent is heterogeneous, and the adsorbed molecules can form multiple layers on its surface. This means that individual adsorption sites differ in their affinity for the adsorbed molecules. This relationship is described by the Freundlich isotherm, whose equation is as follows [65,66,67,68]:

The equation can be expressed in a linear form:

where

- qe—amount of adsorbed substance per unit mass of adsorbent [mg/g];

- KF—Freundlich constant [L/mg];

- Ce—concentration in the liquid phase at equilibrium [mg/L].

- 1/n—exponent determining the intensity of adsorption and surface heterogeneity [-].

The kinetics of copper ion adsorption from the model solution were determined based on changes in adsorbate concentration as a function of time, using pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models.

where

- qe—amount of adsorbate adsorbed during time t [mg/g];

- V—solution volume [L];

- C0—initial concentration [mg/L];

- Ct—concentration at time t [mg/L];

- m—adsorbent mass [g].

Two kinetic models were used:

Pseudo-first-order model:

Based on the graph, ln(qe − qt) vs t allows us to determine k1 and qe.

Pseudo-second-order model:

Based on the graph, t/qt vs t allows us to determine k2 and qe.

The R2 coefficient was used to assess the fit of the model to the data.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Morphology Analysis

The morphology of the adsorbent surfaces was examined by (light) optical microscopy at magnifications of 20×, 100×, and 400×. The acquired images enabled the assessment of the structure and possible differences in the surface structure of the tested samples.

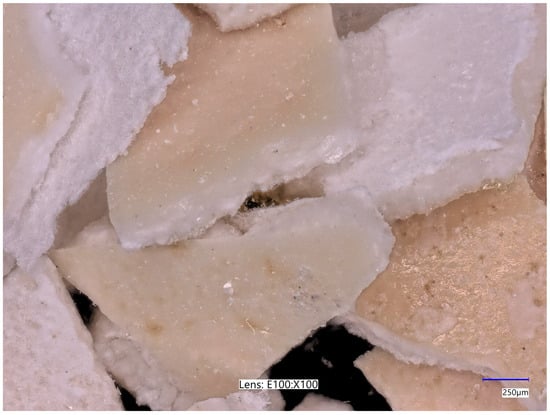

The chicken eggshell (Figure 1 and Figure 2) samples are heterogeneous—their fragments differ in shape, size, and degree of transparency. The micrographs show irregular, brittle particles of varying sizes, some of which have sharp edges. The surface of the material is slightly rough, with microaggregates and residual porosity. This heterogeneity—together with edge sharpness and surface roughness—is consistent with literature descriptions of pulverized chicken eggshell powders.

Figure 1.

Optical micrographs of a coarse-grained eggshell fraction acquired at 100× magnification.

Figure 2.

Optical micrographs of a fine-grained eggshell fraction acquired at 100× magnification.

In particular, surface irregularity has been reported to enhance the adsorption of metal ions [69,70,71].

The photograph of larger shell fragments (Figure 1) shows both more homogeneous areas and areas with a distinct crystalline texture. The presence of darker inclusions in both samples may indicate possible contamination. The presence of fragments with a crystalline structure may suggest the presence of mineral phases such as calcium carbonate and other compounds capable of binding metal ions.

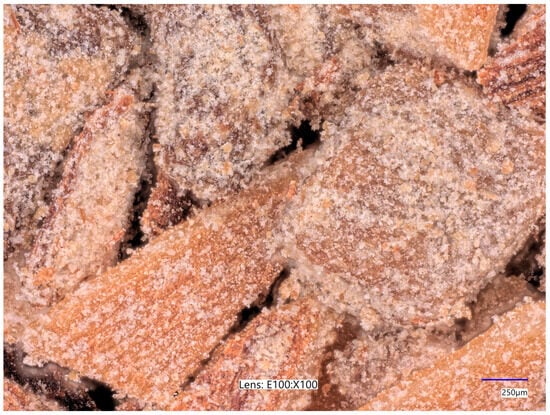

Like eggshell-derived material, adsorbents prepared from horse chestnut seeds exhibit irregular particle shapes and a broad particle-size distribution. Sharp edges and heterogeneous morphology indicate that the powder was produced by breaking/crushing. The colour contrast among fragments reflects different parts of the chestnut seed—brown (outer seed coat) versus white (inner seed tissues). The sample composed of smaller particles (Figure 3) is more homogeneous compared to the sample containing larger seed fragments.

Figure 3.

Optical micrographs of a fine-grained horse chestnut seed fraction acquired at 100× magnification.

In Figure 4, agglomerates of inner seed material are clearly visible on seed-coat fragments. The results of the observations indicate that the sample with larger particle sizes contains a higher proportion of seed coat elements.

Figure 4.

Optical micrographs of a coarse-grained horse chestnut seed fraction acquired at 100× magnification.

The surface images of both samples (Figure 5 and Figure 6) reveal a heterogeneous, granular structure.

Figure 5.

Optical micrographs of a coarse-grained acorn fraction acquired at 100× magnification.

Figure 6.

Optical micrographs of a fine-grained acorn fraction acquired at 100× magnification.

Like previous adsorbents, the samples consist of fragments of varying sizes and shapes, among which sharp, irregular elements and finer grains embedded between them are prominent.

The observed morphological features indicate the presence of pores and intergranular spaces, which increase the effective surface area of the material and enhance its adsorption properties. The variation in colour (lighter and darker areas) suggests the presence of different parts of the acorn.

As in the case of the horse chestnut seed sample, the sample with a larger grain fraction contained a higher proportion of acorn shells compared to the sample with a fine grain fraction.

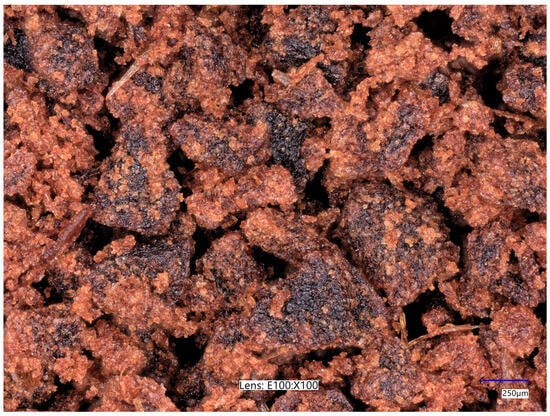

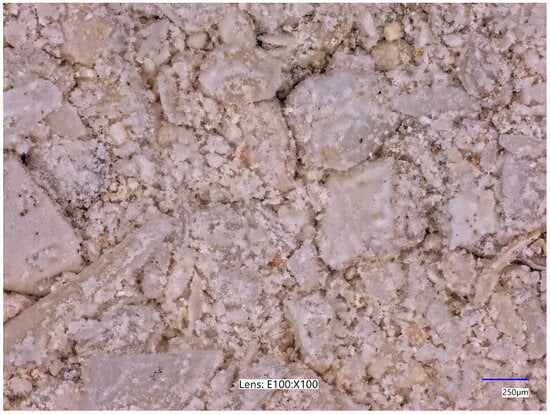

The morphology of coffee grounds (Figure 7) is characterized by a distinctly heterogeneous structure with irregularly shaped particles. Microscopic observations reveal the presence of fragments of varying sizes, from fine grains to larger, porous agglomerates. The particles are characterized by a rough, uneven, and porous structure, which may result from the roasting process and the extraction of soluble substances during coffee brewing. The structure observed in the microscopic images corresponds to the structures presented in the literature [72,73]. Lighter agglomerates are also visible on the surface, which may be residues of organic substances; according to the literature, these may be organic compounds such as lignin or hemicellulose [73]. This morphology promotes the development of specific surface area and may have a beneficial effect on the adsorption properties of coffee grounds [72].

Figure 7.

Optical micrographs of coffee grounds acquired at 100× magnification.

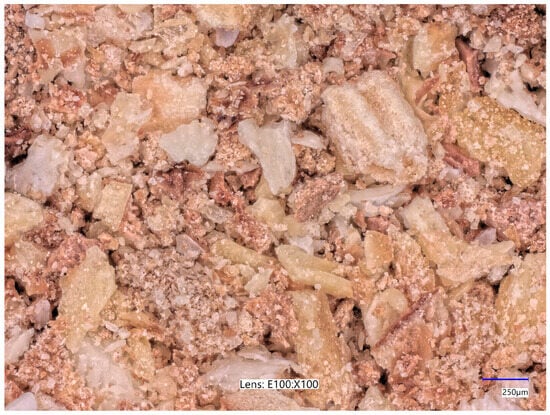

The adsorbent prepared from potato peels (Figure 8) is characterized by a heterogeneous, partially crystalline structure. The fragments are irregular in shape, which is typical for brittle material. The irregularity of the shapes is confirmed by the literature [74]. The particles exhibit a variety of colours: light brown, yellowish, and red. The surface of the particles is rough, with minor irregularities and micropores.

Figure 8.

Optical micrographs of potato peels acquired at 100× magnification.

Chicken bone fragments, like other adsorbent materials, exhibit a wide variety of particle shapes and structures. Figure 9 shows clearly larger bone fragments compared to those shown in Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Optical micrographs of coarse-grained chicken bone fraction acquired at 100× magnification.

Figure 10.

Optical micrographs of fine-grained chicken bone fraction acquired at 100× magnification.

The material is characterized by varied colouring—the shades of individual particles range from beige to brown. In both cases, there is visible porosity—there are numerous irregularly distributed empty spaces, which may be remnants of Haversian canals. The presence of pores and irregular cavities may indicate the preservation of the internal architecture of the bone tissue [75], which is important in the context of the material’s adsorption capacity. This structure promotes an increase in specific surface area. Porosity and the presence of channels may aid in the retention of pollutant molecules, making bone a promising adsorbent material.

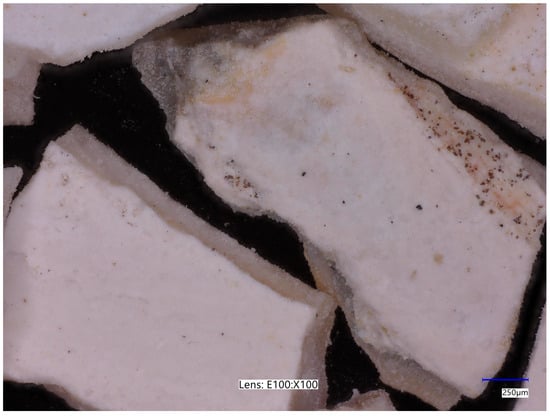

In the case of the common cockle shell (Figure 11 and Figure 12), irregular fragments of varying sizes can be observed. The larger fragments (shown in Figure 11) have sharp, clearly defined edges, while the smaller ones (Figure 12) have more rounded shapes, which may indicate varying degrees of mechanical damage.

Figure 11.

Optical micrographs of a coarse-grained cockle shell fraction acquired at 100× magnification.

Figure 12.

Optical micrographs of a fine-grained cockle shells fraction acquired at 100× magnification.

The variations in colour and brightness of the individual particles indicate a heterogeneous mineral composition of the material. The light colour and absence of a well-defined crystalline morphology suggest the presence of organic or mineral–organic phases. The surfaces of the samples are clearly irregular and porous.

There are aggregates of varying sizes, which occur in a partially compacted and partially fragmented form. Small, irregular pellets and fragments probably correspond to dust or micro-sized fragments. The presence of numerous pores and cracks indicates a microporous structure of the material, which implies a significantly developed specific surface area, important from the point of view of adsorption potential. The porosity of various types of shells has also been confirmed in the literature [76,77].

The surface of the commercially available adsorbent sample is clearly heterogeneous (Figure 13), composed of numerous grains of varying size, shape, and colour. Shades of grey and black dominate, and in some places there are small inclusions of red, yellowish, or orange colours, which may indicate the presence of different phases or mineral inclusions. The structure of the material is characterized by distinct porosity—numerous small pores and channels are visible, which may form a system of interconnected internal spaces. This microstructure suggests that the material has a very large specific surface area, which makes it a potentially excellent adsorbent.

Figure 13.

Optical micrographs of a commercially available adsorbent (MOF) acquired at 100× magnification.

3.2. Specific Surface Area Analysis

Specific surface area is one of the key parameters characterizing the effectiveness of adsorbent materials. It determines the total surface area of available active sites—both those located on the external surface of particles and within pores—per unit mass [m2/g]. A higher specific surface area provides more active sites for the adsorption of molecules from the solution, which directly affects the effectiveness of the adsorption process [78,79]. Measurement by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (SBET) method together with the analysis of the pore-size distribution are basic tools for comparing materials and for predicting their efficacy in wastewater purification from selected pollutants, including heavy metal ions such as copper [79,80].

Table 2 presents the results of specific surface area tests of all adsorbent samples, including organic materials, such as eggshells, horse chestnut seeds, acorns, potato peels, and coffee grounds, as well as mineral materials, such as shells and bones.

Table 2.

Specific surface area BET (SBET) of the tested adsorbents.

Based on these findings, it can be concluded that organic materials have significantly lower specific surface areas and smaller pore volumes compared to mineral materials. The smallest specific surface area was observed in the samples of eggshell, coarse-grained fraction acorns, and potato peels. Organic materials feature pores > 100 Å, which indicates a structure dominated by macropores and loose channels. Mineral materials (bones and shells) exhibit a significantly higher specific surface area (2–4 m2/g) and mainly medium-sized pores (<300 Å), consistent with mesoporous and fissured structure.

For most adsorbents, grinding leads to a doubling of the specific surface area.

However, chestnuts are an exception; milling causes the shell to separate from the kernel, reducing effective surface development. Bones also behave atypically; larger fragments exhibit a markedly higher specific surface area, reflecting their distinctive material structure.

The results obtained are consistent with the observed surface morphology, particularly for the kernel. Larger fragments of the material have a significantly larger specific surface area and porosity, which can be attributed to the presence of numerous channels and pores, clearly visible in optical micrographs.

However, the largest specific surface area is found in commercially used adsorbents, which have an enormous surface area thanks to pores of the order of several nanometres. This is typical for highly porous materials designed specifically for adsorption processes.

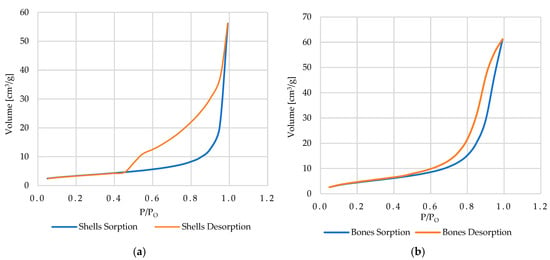

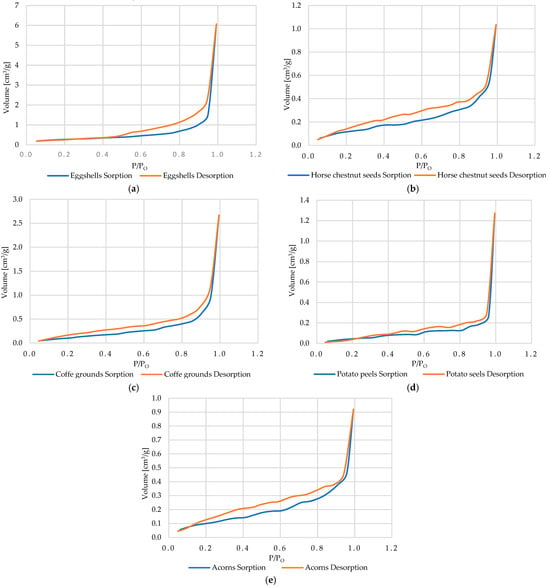

The specific surface area value alone provides only general information about the surface area of the tested materials and their potential sorption capacity. However, comprehensive structural characterisation also requires an analysis of adsorption–desorption isotherms to distinguish pore types and the mechanisms governing adsorbate retention. In particular, the presence and shape of hysteresis loops provide information about the geometry and accessibility of pores (micro-, meso-, or macropores), as well as about the condensation and desorption processes occurring in the material structure [79,80,81]. Therefore, in addition to SBET measurements, the shape of the isotherms obtained for the tested samples was also analysed, allowing them to be assigned to the appropriate hysteresis types according to the IUPAC classification [80].

The shape of the adsorption–desorption isotherm and the presence of hysteresis loops reflect the geometry of the pores and the mechanisms of condensation and evaporation occurring within them. According to the IUPAC classification, six isotherm types (I–VI) and five hysteresis loop types (H1–H5) are distinguished, each associated with specific pore forms and network effects [79,80,81]. Based on the isotherms of cockle shells and bones (Figure 14a,b), which show a pronounced increase in the volume of sorbed N2 at high relative pressures P/P0 > 0.8 together with a clear hysteresis loop, these materials can be assigned to IUPAC type IVa with H3 hysteresis [79,80]. This refers to mesoporous materials (pore diameter approx. 2–50 nm), in which adsorption initially proceeds as a monolayer, followed by a multilayer, and at higher pressures, capillary condensation dominates. The H3 type of hysteresis loop indicates slit-like, open pores, often formed in plate-like or needle-like structures, in which there are no distinct necks blocking the pores. In the context of Cu2+ ion sorption, such a structure promotes diffusion and ion exchange within the pores.

Figure 14.

The adsorption and desorption isotherms obtained for the fine-grained cockle shells fraction (a) and coarse-grained bones fraction (b).

Organic materials (eggshells, horse chestnut seeds, coffee grounds, potato peels, and acorns) exhibit sorption isotherms consistent with IUPAC type II (Figure 15a–e), characteristic of non-porous or microporous surfaces [79,80,81]. In such systems, the binding of Cu2+ ions is mainly determined by interactions with surface functional groups (amine, carboxyl, phenolic, peptide) associated with protein and polysaccharide fractions, rather than by an internal pore network. The effectiveness of sorption therefore depends primarily on the chemical composition of the surface and the possibility of its chemical modification.

Figure 15.

The adsorption and desorption isotherms or organic adsorbents: eggshells (a), horse chestnut seeds (b), coffee grounds (c), potato peels (d), and acorns (e).

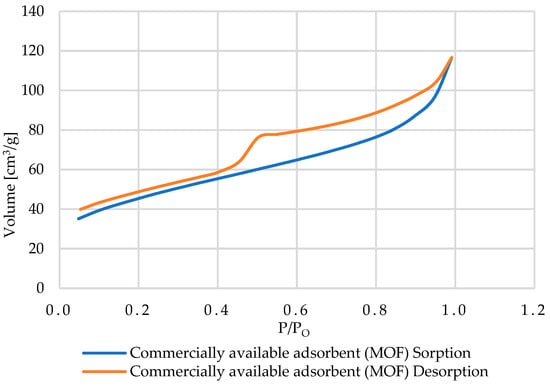

In contrast, in the case of the MOF-type carbon sample, with a very high specific surface area (~122 m2/g) and small pores, a type I isotherm was found, typical for microporous materials [79,80]. This isotherm is characterized by a rapid increase in the adsorbed gas volume at low relative pressures P/P0 and the absence of a clear hysteresis, which confirms the predominance of micropores in the material structure (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

The adsorption and desorption isotherms obtained for the commercially available adsorbent (MOF).

These characteristics are beneficial for the adsorption of gases and small molecules; however, in environmental applications (e.g., removal of Cu2+ from wastewater), performance can be hindered by micropore blocking/fouling by natural organic matter (NOM) or other colloids present in the solution. Therefore, despite its very high specific surface area, the practical sorption efficiency of MOF carbon may be lower than that of mesoporous materials (e.g., bone or cockle shell) [82,83].

3.3. Preliminary Adsorption of Cu2+ Ions from the Standard Solution

Selected adsorbents were tested in a standard (reference) solution to assess their Cu2+ sorption capacity. According to the literature, key process parameters such as solution pH, contact time, adsorbent dose, and initial contaminant concentration have a significant impact on adsorption efficiency [84].

The pH of the solution is one of the key factors that influence the effectiveness of adsorption of both organic pollutants, such as dyes, and heavy metals, e.g., copper. This parameter affects the surface charge of the adsorbent and the degree of ionization of pollutant molecules, which in turn determines the adsorption mechanisms, including electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and hydrophobic interactions [85]. Based on the literature data, the most optimal pH for copper removal is 5–6 [86,87]. Considering the acidic nature of real wastewater, a reference solution at a pH of 3.0 was used in this study. Although a higher pH could potentially improve adsorption efficiency, the aim of the experiment was to compare the effectiveness of different adsorbents, not to evaluate the effect of pH, so it was important to maintain the same conditions for all tests. The initial concentration of the solution was approximately 10 mg/L, and the adsorbent mass was 1 g.

In this study, 1.00 g of natural adsorbent (e.g., chicken bone, eggshell, mussel shell, chestnut, or acorn material) was used in batch experiments for Cu(II) removal. The selected mass follows common practice in similar studies, where adsorbent doses typically range from 0.1 to several grams depending on solution volume and concentration [88,89,90]. A dose of 1 g provides an appropriate solid-to-liquid ratio, ensuring sufficient active sites and measurable concentration changes, while avoiding both under- and over-saturation [91]. This mass also allows for direct comparison with other research using waste-derived biosorbents and is practical for repeated laboratory testing [92]. The contact times were selected to accurately monitor the adsorption kinetics and identify the time required to reach equilibrium. The final point (24 h) verifies whether equilibrium has been achieved and checks for possible desorption at longer times [88,89,91]. This time sequence is consistent with previous kinetic studies on Cu(II) adsorption by natural waste materials.

Based on the obtained results, two adsorbents with the highest Cu2+ removal efficiency and adsorption capacity were selected—cockle shells (fine-grained fraction) and bones (coarse-grained fraction). The selected materials, fine-grained fraction shells and coarse-grained fraction bones, formed the basis for further optimization studies, including the determination of process parameters and adsorption mechanisms. These materials were selected for further optimization of key process parameters and elucidation of adsorption mechanisms.

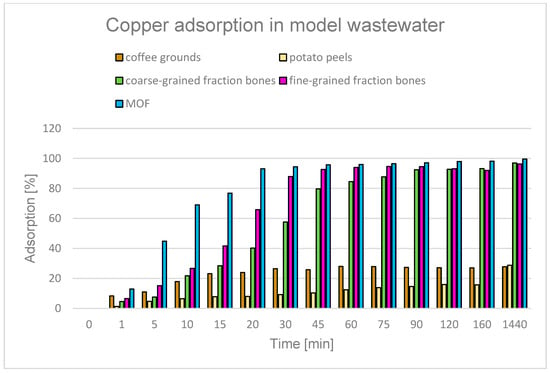

The literature describes various ways of using coffee grounds for wastewater treatment. One of the most frequently studied approaches is converting them into biochar [93,94,95,96] or modifying the raw material to improve its adsorption properties [97,98]. Some studies have also used unprocessed coffee grounds as an adsorbent to remove various pollutants, such as tetracycline [99], chromium [100], and cadmium [101]. The possibility of using coffee grounds as an adsorbent for the treatment of acidic wastewater containing copper ions was evaluated in this study. It was found that 1 g of material adsorbed approximately 23% of Cu2+ ions within the first 15 minutes of the process. In the following minutes, the degree of adsorption increased only slightly, reaching a maximum of approximately 28% (Figure 17). The halt in the increase in efficiency may indicate rapid saturation of the adsorbent surface and exhaustion of available sorption sites.

Figure 17.

Degree of Cu2+ adsorption over time for different adsorbents: bones, coffee grounds, potato peels, and MOF.

Another adsorbent tested was potato peels. Potato peels, which are readily available organic waste with a high carbon content, have attracted considerable interest in the literature as a raw material for the production of biochar [102,103,104,105]. Studies available in the literature indicate the possibility of using unprocessed potato peels to remove heavy metals. For example, they were used to adsorb cadmium from a model solution with a concentration of 100 mg/L, using 1 g of biosorbent, which allowed for a maximum removal efficiency of 76% at pH 5.8 [106]. Another study showed that 0.5 g of charred potato peels was able to remove 61% of the total heavy metal content from a solution containing a mixture of heavy metals (cobalt, magnesium, iron, lead, and cadmium) at a concentration of 10 mg/L within one hour at pH 9 [107]. In the study, potato peels showed the ability to remove only 28.8% of the copper content from the solution (Figure 17), which may be due to the properties of copper itself and the conditions under which the process took place, e.g., a much lower pH of the solution.

Compared to potato peels and coffee grounds, bones showed significantly higher efficiency in removing copper ions from the model solution—at a level of 96–97%. The high effectiveness of bone use—mainly in the form of biochar [39,108,109,110,111,112]—is confirmed in the literature, which emphasizes the high efficiency of adsorbents obtained from bone materials in the process of purifying aqueous solutions. For example, chicken bone ash was effectively used to remove phenol from wastewater, achieving an efficiency of 51.4–100% depending on the initial concentration of the contaminant (10–500 mg/L) [113]. Fish bones were used to adsorb Cd2+ and Pb2+ [114] and pharmaceuticals from contaminated water [115]. Modified bone powder was used to remove cobalt, achieving a purification efficiency of approximately 68% [116]. Charred chicken bones were used to remove methyl blue dye, achieving an adsorption rate of approximately 90% [110]. Charred cow bones were used to remove copper and nickel ions from an aqueous solution; at lower concentrations (0–50 mg L), the removal efficiency of both ions was almost 100% [112]. The literature describes the use of hydroxyapatite, the main mineral component of bone, to remove lead ions from aqueous solutions. In one study, a sorption efficiency of 99.04% was achieved at an initial Pb2+ concentration of 50 mg/L, in the pH range of 3–7 and with a contact time of 60 min [117].

In this study, only dried bones were used, without high-temperature thermal treatment, achieving a solution purification efficiency of over 96% after 24 h, even at a pH unfavourable for the process (Figure 17). These results indicate the possibility of effective use of bones as an adsorbent without the need for costly heat treatment, which can significantly reduce the production costs of the purification material.

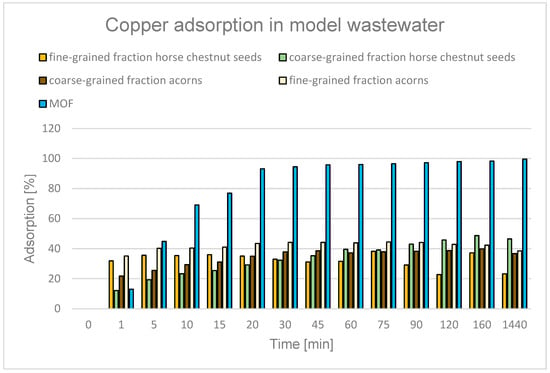

As with previous adsorbents, there is a wealth of information available in the literature on the processes of producing biochar from horse chestnut, mainly from its shells [118,119,120,121,122,123] and acorns [124,125]. Such biochar is highly effective—for example, biochar obtained from horse chestnut shells, used to remove lead and zinc ions, achieved a maximum efficiency of 98.7% (at a dose of 1.5 g) and 91% (at a dose of 0.5 g) in 60 min [123]. In another experiment, oak acorns employed as a natural sorbent achieved approximately 97% Cr removal at 5 g L−1 [126].

In this study, biosorbents derived from horse chestnut seeds and acorns achieved Cu2+ removals of 23.2% (horse chestnut, fine-grained fraction), 46.4% (horse chestnut, large seeds), 38.5% (acorn, fine-grained fraction), and 36.7% (acorn, coarse-grained fraction) (Figure 18). The lower removal efficiency may be attributed to the low pH. Literature data confirm the significant influence of pH on copper removal using acorns [125].

Figure 18.

Degree of Cu2+ adsorption over time for different adsorbents: horse chestnut seeds, acorns, and MOF.

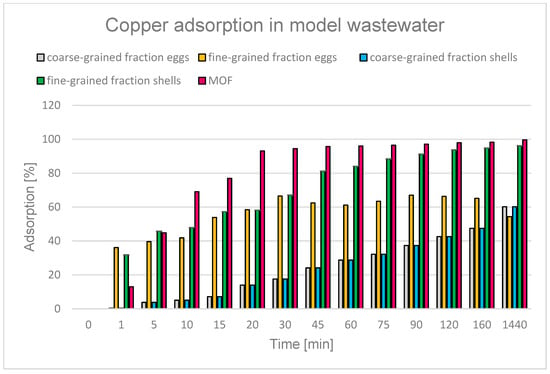

Eggshells are a well-known and effective adsorbent used to remove heavy metals from aqueous solutions. They are characterized by high adsorption capacity, and their effectiveness has been confirmed, among others, in the process of removing chromium, lead, mercury, and cadmium [71,127,128,129,130,131]. In this study, the effectiveness of Cu2+ ion removal was 54.3% (fine-grained fraction eggshells) and 60.2% (coarse-grained fraction eggshells) after 24 h at pH 3 (Figure 19).

Figure 19.

Degree of Cu2+ adsorption over time for different adsorbents: eggs, shells, and MOF.

Another adsorbent tested was common cockle shells. Shells from both fresh and salt water are widely used, especially in the field of environmental protection. Thanks to their physicochemical properties, they are used as natural adsorbents in processes for removing heavy metals from aqueous solutions. The literature describes the use of various types of mollusc shells for the adsorption of heavy metals, including cadmium, copper, lead, and chromium [132,133]. Studies have shown that the adsorption efficiency was significantly lower at pH 2, but increased with increasing pH, achieving the best results at pH 6 [134]. In this study, the possibility of using shells from salt waters to remove copper ions was tested, achieving copper adsorption efficiency of 96.2% (fine-grained fraction shells) and 60.2% (coarse-grained fraction shells) after 24 h at pH 3 (Figure 19). The clear change in the effectiveness of the adsorbent depending on its specific surface area emphasizes the key importance of this parameter for the efficiency of the adsorption process.

Based on the results obtained, it can be concluded that the degree of copper adsorption by the selected adsorbents is closely related to their specific surface area, which is confirmed by the fact that the best copper adsorption results were obtained for bone, shells, and commercially available activated carbon, which had the highest specific surface area values. In the case of organic materials, the process may also depend on the presence of compounds such as proteins or polysaccharides. Shells, although they contain organic components such as proteins, are primarily composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Their alkaline surface could promote the binding of positively charged heavy metal ions, making them effective sorbents for these pollutants. In turn, the main component of bones is hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2), which is a form of calcium phosphate. It can exchange ions, i.e., Ca2+ ions in hydroxyapatite can be exchanged for heavy metal ions, such as copper ions. Bones also contain collagen and other proteins containing –COOH and –NH2 groups, which can form complexes with metals [135].

Based on the results obtained, large bones and small shells were selected for further testing, as they showed the highest degree of copper removal among natural and waste adsorbents under specific experimental conditions.

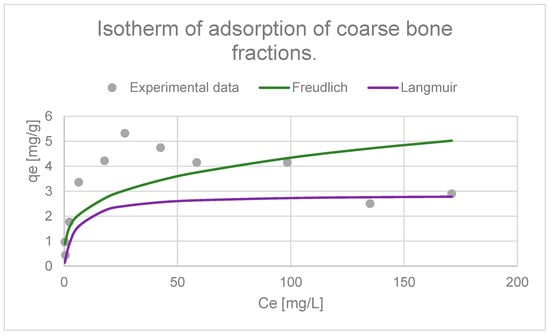

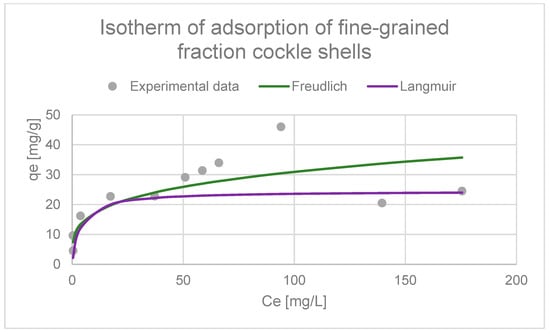

The adsorption of copper ions by selected adsorbents was described using the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms, which show the relationship between the amount of adsorbed metal and its equilibrium concentration in solution. The use of both models allows for the determination of the maximum adsorption capacity (qe) and the equilibrium constant (K) associated with the adsorption energy. The parameters obtained allow the comparison of the properties and effectiveness of different adsorbents in removing copper ions from the aquatic environment (Figure 20 and Figure 21) [65].

Figure 20.

Adsorption isotherm graph (Langmuir and Freundlich) of coarse bone fractions.

Figure 21.

Adsorption isotherm graph (Langmuir and Freundlich) of fine-grained fraction comprising cockle shells.

In order to describe the adsorption equilibrium, experimental data were fitted to the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models. These studies were conducted in an acidic environment with a pH of 3.0. The fit coefficients obtained for coarse bone fractions indicate that the Langmuir model (R2 = 0.9535) better describes the adsorption process than the Freundlich model (R2 = 0.59). This suggests that adsorption occurs mainly according to the Langmuir mechanism, which means the formation of a monolayer of adsorbate on the surface of the adsorbent, where all active sites exhibit similar affinity for metal ions (Figure 20, Table 3). The lower fit to the Freundlich model indicates that this model only partially describes the adsorption process in the tested system. However, the literature states that a value of n in the range of 2–10 indicates good adsorption. The calculated value of n for copper adsorption was 3.68, which suggests high efficiency of copper ion adsorption by the coarse bone fractions’ adsorbent [66,136].

Table 3.

Parameters of the Langmuir and Freundlich models.

Similar fit coefficients were obtained for fine-grained fraction cockle shells, indicating that the Langmuir model (R2 = 0.9226) better describes the adsorption process than the Freundlich model (R2 = 0.7501). This means that adsorption occurs mainly according to the Langmuir mechanism. However, the lower, but still relatively high fit of the Freundlich model indicates that the surface of the adsorbent is not completely homogeneous, and that the adsorption process may also involve sites with varying binding energies. This may indicate a partial contribution of the multilayer adsorption mechanism or a certain degree of heterogeneity of the surface of the tested materials (Figure 21, Table 3).

In order to better understand the mechanism of copper ion adsorption on selected adsorbents, a kinetic analysis was performed using pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic models.

Analysis of kinetic data showed that the pseudo-first-order model is characterized by a higher coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.9052) compared to the pseudo-second-order model (R2 = 0.7368). This means that the kinetics of copper adsorption on coarse-grained fraction bones is better described by the pseudo-first-order equation, indicating that the process proceeds mainly through a mechanism of physisorption controlled by external diffusion.

Analysis of the kinetics of copper adsorption by the fine-grained fraction containing cockle shells showed that both the pseudo-first-order model (R2 = 0.9798) and the pseudo-second-order model (R2 = 0.9926) describe the experimental data very well. The equilibrium value qe for the pseudo-first-order model was 0.828 mg·g−1, while for the pseudo-second-order model it was 1.007 mg·g−1. Given the equally high statistical fit, the differences between the models may result from the mechanism of the process. The results obtained suggest that both physisorption (pseudo-first-order model) and chemisorption (pseudo-second-order model) may play a role in the adsorption process under study, and their kinetics are complex.

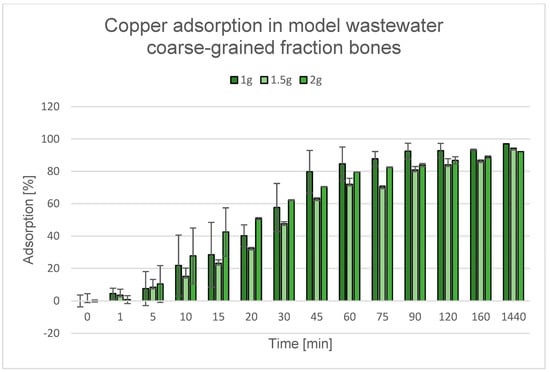

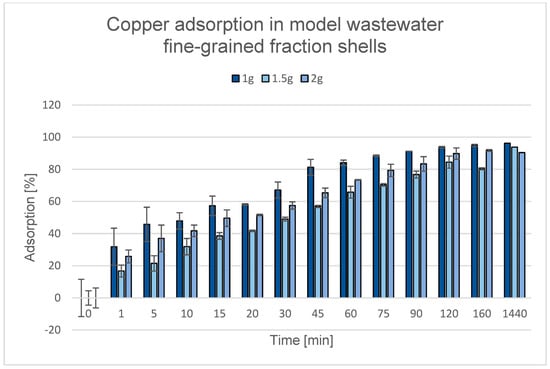

3.4. Mass of Adsorbent Used

One of the important factors affecting the effectiveness of adsorption is the mass of the adsorbent used, which can determine both the degree of contaminant removal and the efficiency of the entire process. The aim of the next study was to determine the relationship between the mass of the adsorbent and its ability to remove copper. Selected adsorbents were tested in an identical model solution using three different masses of the adsorbent: 1.0 g, 1.5 g, and 2.0 g (Figure 22 and Figure 23).

Figure 22.

Degree of Cu2+ removal during the adsorption process using various quantities of coarse-grained fraction bones.

Figure 23.

Degree of Cu2+ removal during the adsorption process using various quantities of fine-grained fraction comprising cockle shells.

Although according to the literature, a higher dose of adsorbent usually increases the adsorption efficiency [85,137,138,139], experimental observations indicate that this relationship is not always linear. In the case of both bones and cockle shells, the highest adsorption efficiency was observed when 1.0 g of adsorbent was used. This may be because at this mass, the sorption material was evenly dispersed in the solution, which ensured optimal contact between the liquid phase and the active surface of the adsorbent. However, when larger amounts of adsorbents (1.5 g and 2.0 g) were used, a decrease in efficiency was observed, which was probably due to difficulties in thoroughly mixing the material. The increased mass promoted particle aggregation and their settling to the bottom of the vessel, which ultimately led to a reduction in the available contact surface between the solution and the active surface of the adsorbent. The effectiveness of the adsorption process largely depends on the contact surface between the adsorbent and the solution, which determines the availability of active adsorption sites. An increase in the effective contact surface engages more adsorption sites that can be involved in the process, thereby enhancing contaminant removal. Therefore, the observed decrease in the degree of adsorption with increasing amounts of adsorbent can be explained by the limited availability of the solution to the active adsorption sites on its surface [140].

The renewed increase in adsorption efficiency during the process at an adsorbent mass of 2.0 g may be related to an overall increase in the available active surface area; a similar effect was observed in the studies described by Rápó, E. and Tonk, S. [141]—although some of the material formed aggregates at the bottom of the container, the larger amount could partially compensate for this effect. Thus, even with limited dispersion, the increased mass of the adsorbent could lead to a higher total degree of contaminant removal due to an increase in the number of available adsorption sites. It should be emphasized that the observed effect changes after 24 h of phase contact.

Across all tested conditions, the 1.0 g dosage exhibited the highest adsorption efficiency and was therefore selected for subsequent experiments.

3.5. Cu2+ Removal from Real Textile Wastewater

Studies of copper ion removal conducted on model solutions often do not fully reflect the complexity of the processes occurring in real industrial wastewater. These differences result from the presence of a multicomponent wastewater matrix, including various coexisting ions, organic substances, and other contaminants that can affect the availability and competition for adsorption sites on the adsorbent surface. In addition, the physicochemical parameters of real wastewater, such as pH, conductivity, ionic strength, and the presence of complexing ligands, modulate the kinetics and equilibrium of Cu ion adsorption [142]. The adsorption efficiency of Cu2+ is often lower in real wastewater compared to model laboratory solutions. This decrease is mainly due to the complex composition of real effluents, which contain various competing cations (e.g., Ca2+, Mg2+, Zn2+, Fe2+) and anions (e.g., Cl−, SO42−, NO3−) that compete with Cu(II) for active adsorption sites [143,144].

The results obtained under laboratory conditions on model solutions are only preliminary and need to be confirmed under real conditions. To properly assess the potential of selected adsorbents for copper removal, tests were performed using real textile wastewater from copper plating.

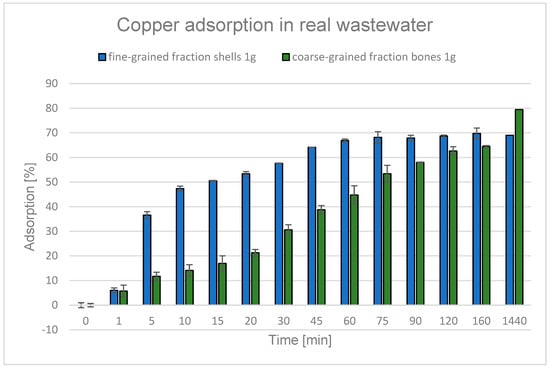

For both adsorbents, a decrease in the degree of Cu2+ ion adsorption was observed in real wastewater conditions compared to model wastewater: coarse-grained fraction bones from 97% to 69%, fine-grained fraction cockle shells from 96.2% to 79.4% (Figure 24).

Figure 24.

Graph showing the degree of copper adsorption from actual textile wastewater during the process using selected adsorbents. Degree of Cu2+ adsorption over time in real textile wastewater with fine-grained cockle shell and coarse-grained bone fractions.

The decrease in adsorption efficiency could have been due to a change in pH—while the model wastewater had a pH of 3.0, the actual wastewater had a lower pH of 2.25. According to the literature, the efficiency of Cu2+ ion adsorption decreases in a strongly acidic environment. At lower pH values, the H+ ions present in the solution compete with Cu2+ ions for active sites on the adsorbent surface, and in addition, electrostatic repulsion of metal ions occurs [86,87,145]. Lowering the pH from 3.0 to 2.25 could therefore have intensified this effect, leading to a decrease in the effectiveness of the adsorption process.

Model wastewater contains a strictly defined concentration of copper ions, without any interfering additives. The observed decrease in the degree of copper adsorption could therefore have been influenced by the presence of other substances present in real wastewater, such as detergents, organic compounds, or salts, which may interact with metal ions or active sites on the surface of the adsorbent.

3.6. The Effect of the Cu2+ Ion Removal Process on the Adsorbent

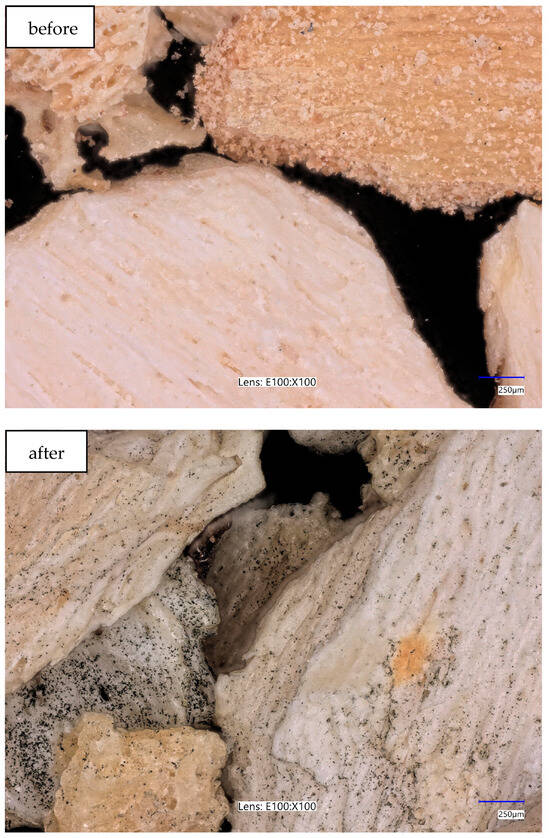

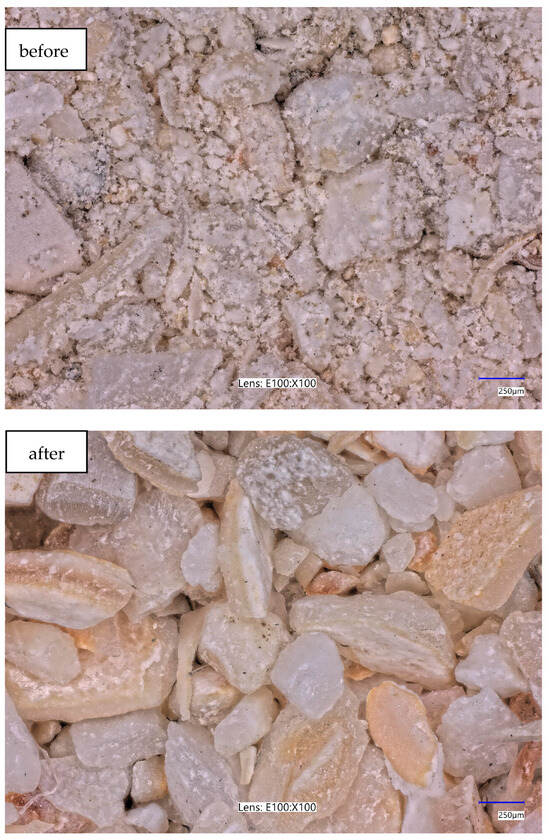

To verify the impact of the copper removal process from actual textile wastewater on selected adsorbents, their specific surface area was re-examined (Table 4 and Table 5), and the morphology and chemical structure of the surface were evaluated (Figure 25 and Figure 26, respectively).

Table 4.

Adsorption kinetics parameters modelled by pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order equations for coarse-grained bone fractions.

Table 5.

Adsorption kinetics parameters modelled by pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order equations for fine-grained cockle shell fractions.

Figure 25.

Optical micrographs of coarse-grained bone fraction (before) and (after) the adsorption process, acquired at 100× magnification.

Figure 26.

Optical micrographs of fine-grained cockle shell fraction (before) and (after) the adsorption process, acquired at 100× magnification.

Specific surface area tests were performed for both the clean adsorbent and the material after the actual wastewater treatment process (Table 6). A significant decrease in specific surface area was observed after the process for both adsorbents tested. This change indicates that the available active sites were occupied by adsorbed contaminants, including copper ions. The decrease in specific surface area confirms the effectiveness of adsorption and may indicate partial saturation of the sorbent surface.

Table 6.

The effect of the adsorption process on the specific surface area BET (SBET) of the adsorbent.

In the case of both adsorbents, clear and significant visual changes were observed, indicating modifications to the surface structure and the presence of adsorbed substances after the adsorption process (Figure 25 and Figure 26). The adsorbent prepared from cockle shells (Figure 26) differed in structure after the process was completed: lighter particles with distinct edges, with no significant amounts of fines. Finer particles may have been washed out during the separation of the solution from the adsorbent. Small inclusions are visible on the surface of the particles, which may indicate the presence of impurities or adsorbed substances on the surface.

In the case of bone adsorbent (Figure 25), changes were also observed—the surface after cleaning became noticeably lighter, whiter, more matte, and smoother, and the pores and crevices became less visible. At the same time, numerous contaminants deposited on the surface of the particles can be observed, which may indicate effective occupation of active sites by wastewater components. This result is also confirmed by a decrease in the specific surface area of the adsorbent.

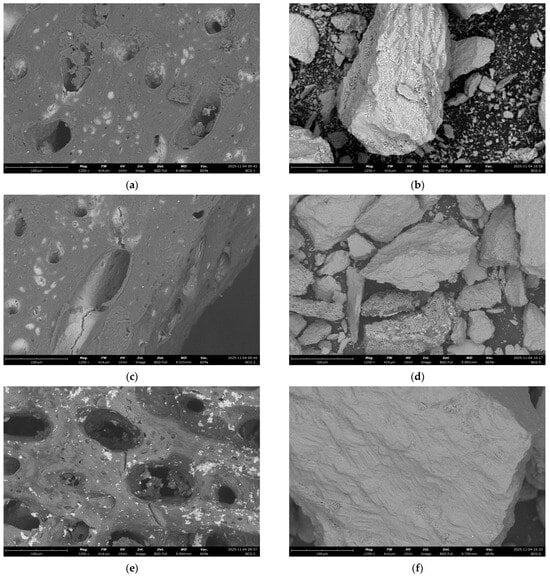

To confirm the observations obtained and to examine the surface morphology of selected adsorbents in detail, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis was performed. This test was performed on three samples: pure adsorbent, adsorbent after contact with the reference solution, and after the adsorption process from actual wastewater. SEM analysis enabled the assessment of changes in surface structure, pore distribution, and material texture, which provided a better understanding of the impact of the adsorption process on the physical properties of adsorbents.

In the sample of coarse-grained bone fraction, it was observed that the pores of the adsorbents were significantly cleaner—the previously visible particles had been removed, which may indicate that they were washed out or detached during the process (Figure 27a,b). On the other hand, after the adsorbent encountered actual wastewater, an irregular, fine, localized deposit appeared on its surface, giving it a non-uniform appearance. This may indicate the deposition of organic or mineral residues from the wastewater (Figure 27c).

Figure 27.

SEM images of the adsorbent surface of coarse-grained fraction bones: (a) clean sample; (b) after adsorption from the reference solution; (c) after adsorption from actual wastewater, taken at 1250× magnification. SEM images of the adsorbent surface of fine-grained fraction cockle shells: (d) clean sample; (e) after adsorption from the reference solution; (f) after adsorption from actual wastewater, taken at 1250× magnification.

In the sample of fine-grained cockle shell fraction, a clearly heterogeneous surface structure was observed, with particles of varying sizes (Figure 27d–f). Both after contact with the model solution and after the adsorption process from real wastewater, a smaller amount of fine fraction is visible, which may indicate its partial leaching or removal during the process (Figure 27e,f). In addition, after exposure to real wastewater, a delicate, darker sediment was observed on the surface, suggesting the deposition of components from the real medium (Figure 27f).

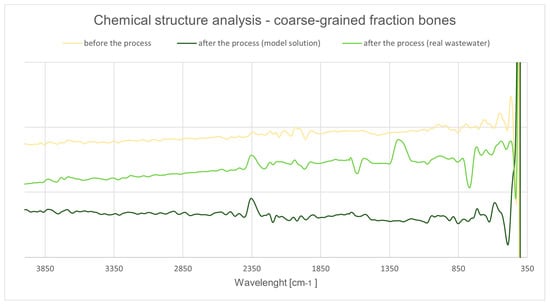

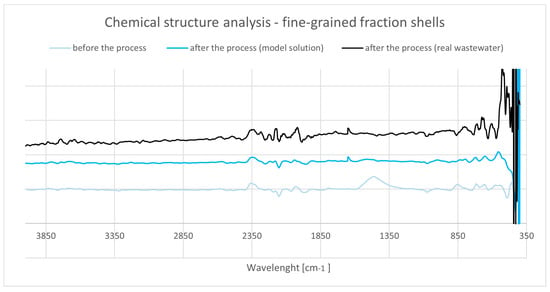

The chemical structure of the surface of selected adsorbents was analysed (Figure 28 and Figure 29).

Figure 28.

ATR-FTIR spectra of chicken bones (coarse fraction) before and after Cu2+ adsorption.

Figure 29.

ATR-FTIR spectra of cockle shells (fine fraction) before and after Cu2+ adsorption.

The untreated bone shows the canonical hydroxyapatite (HAp) phosphate vibrations: ν3(PO43−) as a broad envelope at ~1030–1090 cm−1, ν1(PO43−) at ~960 cm−1, and the ν4(PO43−) doublet at ~602/565 cm−1; weak lattice OH signatures of apatite appear near ~3570 and ~630 cm−1. Residual collagen yields amide I (~1650 cm−1) and amide II (~1540 cm−1). After exposure to Cu2+, phosphate bands broaden and shift slightly (≈2–6 cm−1) with a modest decrease in relative intensity, which is consistent with surface complexation/partial ion exchange of Ca2+ by Cu2+ at phosphate sites in non-stoichiometric biological apatite [146,147]. Concomitantly, the H–O–H bending band at ~1630–1650 cm−1 becomes more pronounced and the 3000–3600 cm−1 region broadens, indicating additional bound/structural water associated with adsorbate coverage [148]. These spectral changes align with the post-process textural evidence (reduced accessible surface and pore volume), pointing to occupation of reactive HAp sites by solutes from the real-matrix wastewater.

The initial spectrum is diagnostic of aragonitic CaCO3 (Figure 29), with ν1 (CO32−) at ~1080–1085 cm−1, split ν3 (CO32−) components in the ~1500–1400 cm−1 region, ν2 (CO32−) near ~855–857 cm−1, and ν4 (CO32−) at ~712–714 cm−1 [149]. Following Cu2+ treatment, carbonate bands display modest broadening and small wavenumber shifts (≈2–4 cm−1), accompanied by a slight intensity decrease, consistent with surface complexation and minor acid etching of aragonite in the working matrix. A weak band at ~1630–1650 cm−1 emerges, tracking increased physiosorbed water [148]. The spectral evolution mirrors the measured drop in specific surface area and subtle pore rearrangements, indicating coverage of reactive carbonate sites by wastewater components together with limited structural modification.

Taken together, ATR-FTIR evidence supports distinct yet complementary adsorption pathways: on bone, Cu2+ primarily engages phosphate groups of biological apatite (with a possible auxiliary contribution from collagenous functionalities) [147,148]; on shells, perturbations of carbonate vibrations indicate Cu2+ attachment at CaCO3 surfaces under slightly acidic conditions [149]. The growth of bound-water signatures and band broadening in both sorbents is congruent with solute overlayer formation and matches the post-adsorption textural trends observed experimentally [148].

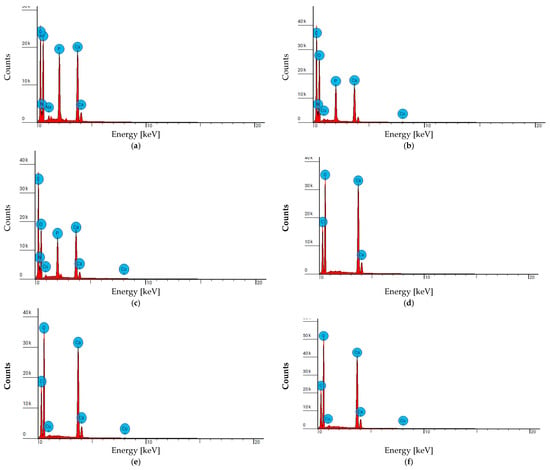

To confirm the presence of copper on the surface of the adsorbent, elemental composition analysis was performed using EDS, which enabled the identification of elements present on the examined surfaces (Figure 30).

Figure 30.

EDS spectra of the adsorbent surfaces: (a–c) chicken bones (coarse fraction)—clean sample, after adsorption from the model solution, and after adsorption from real wastewater, respectively; (d–f) cockle shells (fine fraction)—clean sample, after adsorption from the model solution, and after adsorption from real wastewater, respectively.

In all tests, after contact with the Cu-containing solution, copper was detected on the surface of the adsorbents, confirming the occurrence of the adsorption process. The presence of Cu peaks in the EDS spectra, together with the simultaneous decrease in Cu concentration in the solutions, indicates that the metal was effectively bound to the surface of both materials: chicken bones (coarse fraction) and cockle shells (fine fraction). These results demonstrate that the tested waste-derived materials exhibit a high capacity for copper ion adsorption from aqueous solutions.

4. Conclusions

Based on the results of tests conducted using a model solution, two natural/waste origin adsorbents with the highest Cu2+ removal were selected: the coarse-grained bone fraction (97.0% after 24 h) and the fine-grained cockle shell fraction (96.2% after 24 h). For comparison, the same amount of commercially available adsorbent reached 99.6% Cu2+ removal from the solution, which makes the developed materials promising adsorbents with relatively high adsorption efficiency.

The study showed that increasing the amount of adsorbent used does not directly correlate with an increase in the effectiveness of the purification process.

Results of the studies performed using a model solution differ significantly from the results obtained for real wastewater streams. The differences may result, among other things, from the presence of interfering substances, the complexity of the matrix, and different physicochemical parameters (e.g., pH, conductivity), which can significantly reduce the adsorption efficiency observed under laboratory conditions.

Of all the materials tested, chicken bones proved to be the best natural adsorbent, showing the highest effectiveness in removing contaminants. This result may be due to the presence of hydroxyapatite and collagen, which have strong sorption properties towards heavy metals. Metal ions can replace calcium in the calcium phosphate structure or form complexes with proteins, which may have made the bones an effective adsorbent.

Although the bones had a significantly smaller specific surface area (4.0850 m2/g for coarse-grained fraction bones vs. 122 m2/g for MOF), longer operating time and slightly lower adsorption efficiency compared to commercially available adsorbents, their advantage is their availability as waste, which makes them an environmentally friendly solution and promotes a circular economy. Waste materials such as bones show potential for use as sorbents in copper ion removal processes, which enables the utilization of food industry residues and may contribute to reducing wastewater treatment costs. In addition, an unquestionable advantage of the tested adsorption materials is that their production does not require complex, high-energy processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.G., K.P. and M.O.-K.; methodology: M.G., M.H.K. and Z.M.; data analysis: M.G., Z.M. and M.H.K.; writing—original draft preparation: M.G.; writing—review and editing, I.K.-K. and M.O.-K.; supervision: K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Work financed under the “FU2N—Fund for the Improvement of Young Scientists’ Skills” programme supporting scientific excellence at the Lodz University of Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was completed while the first author was a doctoral candidate in the Interdisciplinary Doctoral School at the Lodz University of Technology, Poland.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sharma, V.; Sharma, A. Nanotechnology: An Emerging Future Trend in Wastewater Treatment with Its Innovative Products and Processes. Int. J. Enhanc. Res. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2012, 1, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Teow, Y.H.; Mohammad, A.W. New Generation Nanomaterials for Water Desalination: A Review. Desalination 2019, 451, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, P.; Jaspal, D.; Malviya, A. Adsorption of Dyes Using Custard Apple and Wood Apple Waste: A Review. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2023, 100, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny/Obszary Tematyczne/Środowisko. Energia/Środowisko/Zielone Płuca Polski w 2021 Roku. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/srodowisko/ochrona-srodowiska-2022,1,23.html (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Jedrzejczak, M.; Wojciechowski, K. Effectiveness of Dyeing Wastewater Treatment. Chemik 2016, 70, 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Romanowska-Duda, Z. Heavy Metals as Specific Pollutants of the Aquatic Environment. Uniwersytet Łódzk, Faculty of Biological Environmental Protection. 2015. Available online: https://www.proakademia.eu/gfx/baza_wiedzy/32/metale_ciezkie_jako_specyficzne_zanieczyszczenia_srodowiska_wodnego.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Srivastava, N.K.; Majumder, C.B. Novel Biofiltration Methods for the Treatment of Heavy Metals from Industrial Wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 151, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, S.S.; Goyal, D. Microbial and Plant Derived Biomass for Removal of Heavy Metals from Wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 2243–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.E.; Olin, T.J.; Bricka, R.M.; Adrian, D.D. A Review of Potentially Low-Cost Sorbents for Heavy Metals. Water Res. 1999, 33, 2469–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ociepa-Kubicka, A.; Ociepa, E. The Toxic Effects of Heavy Metals on Plants, Animals and Humans. Inżynieria i Ochr. Środowiska 2012, 15, 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, D.; Li, X.; Yue, J. Effects of Heavy Metals on Variation in Bacterial Communities in Farmland Soil of Tailing Dam Collapse Area. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, J.; Gworek, B.; Florek-Łuszczki, M.; Nowak-Starz, G.; Wójtowicz, B.; Wójcik, T.; Żeber-Dzikowska, I.; Strzelecka, A.; Szpringer, M. Heavy Metals in the Environment and Their Impact on Human Health. Przem. Chem. 2020, 1, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Human Health Effects of Benzene, Arsenic, Cadmium, Nickel, Lead and Mercury; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh, S.; Suryavanshi, H.S.; Tiwari, M.; Pulhani, V.A. Assessment of Heavy Metals Associated Health Risk to Humans from Biota in Thane Creek, India. Discov. Environ. 2025, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meftah, S.; Meftah, K.; Drissi, M.; Radah, I.; Malous, K.; Amahrous, A.; Chahid, A.; Tamri, T.; Rayyad, A.; Darkaoui, B.; et al. Heavy Metal Polluted Water: Effects and Sustainable Treatment Solutions Using Bio-Adsorbents Aligned with the SDGs. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Białecka, B.; Daraiusz, Z. Sources of Copper Ions and Selected Methods for Their Removal from Wastewater Originating from the Production of Printed Circuit Boards. Inżynieria Ekol. 2014, 37, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, M.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; Anbu, P.; Packirisamy, V.; Yaakub, A.R.W.; Wu, Y.S. Efficient Copper Adsorption from Wastewater Using Silica Nanoparticles Derived from Incinerated Coconut Shell Ash. Bionanoscience 2024, 14, 2739–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganji, H.; Taghavijeloudar, M. Efficient Adsorption of Lead and Copper from Water by Modification of Sand Filter with a Green Plant-Based Adsorbent: Adsorption Kinetics and Regeneration. Environ. Res. 2024, 259, 119529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hama Aziz, K.H.; Mustafa, F.S.; Omer, K.M.; Hama, S.; Hamarawf, R.F.; Rahman, K.O. Heavy Metal Pollution in the Aquatic Environment: Efficient and Low-Cost Removal Approaches to Eliminate Their Toxicity: A Review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 17595–17610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, S.; Lipiński, P.; Ogórek, M.; Starzyński, R.; Grzmil, P.; Bednarz, A.; Lenartowicz, M. Molecular Regulation of Copper Homeostasis in the Male Gonad during the Process of Spermatogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Romaña, D.L.; Olivares, M.; Uauy, R.; Araya, M. Risks and Benefits of Copper in Light of New Insights of Copper Homeostasis. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2011, 25, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.A.; Tsuji, J.S.; Garry, M.R.; McArdle, M.E.; Goodfellow, W.L.; Adams, W.J.; Menzie, C.A. Critical Review of Exposure and Effects: Implications for Setting Regulatory Health Criteria for Ingested Copper. Environ. Manage 2020, 65, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Cui, Y.; Chen, N. Removal of Copper Ions from Wastewater: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhawan, S.; Jain, A.; Nayyar, J.; Mehta, S.K. Role of Nanomaterials as Adsorbents in Heavy Metal Ion Removal from Waste Water: A Review. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 33, 101038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, V.G.; Misra, A.K. Copper Contaminated Wastewater—An Evaluation of Bioremedial Options. Indoor Built Environ. 2018, 27, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, T.; Parry, D.L. Removal of Sulfate and Heavy Metals by Sulfate Reducing Bacteria in Short-Term Bench Scale Upflow Anaerobic Packed Bed Reactor Runs. Water Res. 2003, 37, 3379–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, D.; Wang, X.; Huang, W.; Lawless, D.; Feng, X. Removal of Heavy Metals from Water Using Polyvinylamine by Polymer-Enhanced Ultrafiltration and Flocculation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 158, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Zhu, L.; Shen, X.; Sotto, A.; Gao, C.; Shen, J. Polythyleneimine-Modified Original Positive Charged Nanofiltration Membrane: Removal of Heavy Metal Ions and Dyes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 222, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Chang, H.; Gao, S.; Zhang, R. How to Fabricate a Negatively Charged NF Membrane for Heavy Metal Removal via the Interfacial Polymerization between PIP and TMC? Desalination 2020, 491, 114499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Jiao, Y.; Yan, F.; Qin, Q.; Qin, S.; Ma, X.; Li, J.; Cui, Z. Construction of Hollow Fiber Nanofiltration Separation Layer with Bridging Network Structure by Polymer-Anchored Co-Deposition for High-Concentration Heavy Metal Ion Removal. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Hu, J.; Lin, S.; Tu, Y.; Chen, L.; Ni, Y.; Huang, L. Recent Advances on Cellulose-Based Nanofiltration Membranes and Their Applications in Drinking Water Purification: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 333, 130171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Wu, Z. Removal of Cu(II) Ions from Contaminated Waters Using a Conducting Microfiltration Membrane. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 339, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, A.W.; Teow, Y.H.; Ang, W.L.; Chung, Y.T.; Oatley-Radcliffe, D.L.; Hilal, N. Nanofiltration Membranes Review: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Desalination 2015, 356, 226–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabane, T.; Taha, S.; Taleb Ahmed, M.; Maachi, R.; Dorange, G. Removal of Copper from Industrial Effluent Using a Spiral Wound Module—Film Theory and Hydrodynamic Approach. Desalination 2006, 200, 403–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Sun, W.; Chen, Z.; Wei, X.; Liu, M. Research Progress on Heavy Metal Wastewater Treatment in the Integrated Circuit Industry: From Pollution Control to Resource Utilization. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 376, 134033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, R.M.; Hassan, I.; El-Abd, M.Z.; El-Tawil, Y.A. Lactic Acid Removal from Wastewater by Using Different Types of Activated Clay. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Water Technology Conference (IWTC), Hurghada, Egypt, 12–15 March 2009; Volume 13, pp. 403–416. [Google Scholar]

- Hammad, W.A.; Darweesh, M.A.; Eweida, B.; Amr, M.H.A.; Bakr, A. Exploring the Efficiency of Chemically Activated Palm Frond Carbon in Heavy Metal Adsorption a Modeling Approach. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khraisheh, M.A.M.; Al-degs, Y.S.; Mcminn, W.A.M. Remediation of Wastewater Containing Heavy Metals Using Raw and Modified Diatomite. Chem. Eng. J. 2004, 99, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.S.; Cheun, J.Y.; Kumar, P.S.; Mubashir, M.; Majeed, Z.; Banat, F.; Ho, S.-H.; Show, P.L. A Review on Conventional and Novel Materials towards Heavy Metal Adsorption in Wastewater Treatment Application. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Xu, Z.; Feng, Q.; Yao, D.; Yu, J.; Wang, D.; Lv, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, N.; Zhong, M.; et al. Accepted Manuscript Effect of Pyrolysis Condition on the Adsorption Mechanism of Lead, Cadmium and Copper on Tobacco Stem Biochar. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 996–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Xu, X.; Miao, R.; Wang, M.; Zhou, H.; He, L.; Guan, Q. Mn-Embedded Porous Rubber Seed Shell Biochar for Enhanced Removal of Copper Ions and Its Ingeniously Re-Functionalizing. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.Q.; Jin, X.Y.; Lu, X.Q.; Chen, Z. liang Adsorption of Pb(II), Cd(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) onto Natural Kaolinite Clay. Desalination 2010, 252, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Yao, L.; Yang, L.; Jiang, W.; Jiang, X. Utilization of Industrial Waste Lithium-Silicon-Powder for the Fabrication of Novel Nap Zeolite for Aqueous Cu(II) Removal. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Jiang, J.; Jiang, M. Effect of Different Production Methods on Physicochemical Properties and Adsorption Capacities of Biochar from Sewage Sludge and Kitchen Waste: Mechanism and Correlation Analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkherraz, A.M.; Ali, A.K.; Elsherif, K.M. Removal of Pb (II), Zn (II), Cu (II) and Cd (II) from Aqueous Solutions by Adsorption onto Olive Branches Activated Carbon: Equilibrium and Thermodynamic Studies. Chem. Int. 2020, 6, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan, N.; Krishna, A.; Fathima, N.N. Leather Solid Waste Derived Activated Carbon as a Potential Material for Various Applications: A Review. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 176, 106249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, F.O.; Musonge, P. Synthesis, Characterization, and Biosorption of Cu2+ and Pb2+ Ions from an Aqueous Solution Using Biochar Derived from Orange Peels. Molecules 2023, 28, 7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, T.; Kazi, A.A.; Sabri, M.U.; Bano, Q. Potato Peels as Solid Waste for the Removal of Heavy Metal Copper(II) from Waste Water/Industrial Effluent. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2008, 63, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, M.-Y.; Lee, T.-A.; Lin, Y.-S.; Hsu, S.-Y.; Wang, M.-F.; Li, P.-H.; Huang, P.-H.; Lu, W.-C.; Ho, J.-H. On the Removal Efficiency of Copper Ions in Wastewater Using Calcined Waste Eggshells as Natural Adsorbents. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranjape, P.; Sadgir, P. Heavy Metal Removal Using Plant Origin Biomass and Agricultural Waste-Derived Biomass from Aqueous Media: A Review. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2023, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopov, T. Removal of Copper (Ii) from Aqueous Solution by Biosorption onto Powder of Jerusalem Artichoke. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Prot. 2015, 1, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Singha, B.; Das, S.K. Adsorptive Removal of Cu(II) from Aqueous Solution and Industrial Effluent Using Natural/Agricultural Wastes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 107, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abood, M.M.; Istiaque, F.; Azhari, N.N. Remediation of Heavy Metals Using Selected Agricultural Waste: Sunflower Husk and Durian Leaves. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 557, 12080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzadi, I.; Mubarak, S.; Farooq, A.; Hussain, N. Apple Peels as a Potential Adsorbent for Removal of Cu and Cr from Wastewater. AQUA-Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc. 2023, 72, 914–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiewer, S.; Patil, S.B. Pectin-Rich Fruit Wastes as Biosorbents for Heavy Metal Removal: Equilibrium and Kinetics. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 1896–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Gogate, P.R. Intensified Removal of Copper from Waste Water Using Activated Watermelon Based Biosorbent in the Presence of Ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 30, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmipathy, R.; Sarada, N.C. Metal Ion Free Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) Rind as Adsorbent for the Removal of Lead and Copper Ions from Aqueous Solution. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 15362–15372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, J.A.T.; Penido, E.S.; Ferreira, G.M.D. Production of Surfactant-Modified Banana Peel Biosorbents Applied to Treatment and Decolorization of Effluents. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 680, 132650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Saeed, A.; Kalim, I. Characterization of Adsorptive Capacity and Investigation of Mechanism of Cu2+, Ni2+ and Zn2+ Adsorption on Mango Peel Waste from Constituted Metal Solution and Genuine Electroplating Effluent. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2009, 44, 3770–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, P.; Bafana, A.; Pakade, Y.B. Xanthate Modified Apple Pomace as an Adsorbent for Removal of Cd (II), Ni (II) and Pb (II), and Its Application to Real Industrial Wastewater. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2015, 97, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Bai, Y.; Qi, C.; Du, Y.; Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, P.; Chen, S.; Zhang, S. Adsorption of Pb(II) and Cu(II) by Succinic Anhydride-Modified Apple Pomace. Biochem. Eng. J. 2024, 201, 109136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Kumar, R. Adsorption Studies of Hazardous Malachite Green onto Treated Ginger Waste. J. Environ. Manage 2010, 91, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, S.S.; Goyal, D. Removal of Heavy Metals by Waste Tea Leaves from Aqueous Solution. Eng. Life Sci. 2005, 5, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Das, P.; Sinha, K. Modeling of Biosorption of Cu(II) by Alkali-Modified Spent Tea Leaves Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN). Appl. Water Sci. 2015, 5, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cișmașu, M.; Modrogan, C.; Orbuleț, O.D.; Bosomoiu, M.; Răileanu, M.; Dăncilă, A.M. Bone Meal as a Sustainable Amendment for Zinc Retention in Polluted Soils: Adsorption Mechanisms, Characterization, and Germination Response. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyun, T.S.; Mseer, A.H. Comparison of the Experimental Results with the Langmuir and Freundlich Models for Copper Removal on Limestone Adsorbent. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, T.; Yan, B.; Li, L.; Xu, D.; Xiao, X. Characterization of the Adsorption of Cu (II) from Aqueous Solutions onto Pyrolytic Sludge-Derived Adsorbents. Water 2018, 10, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, M.; Guo, W.; Wu, Q.; Wang, J. Study on Adsorption Model and Influencing Factors of Heavy Metal Cu2+ Adsorbed by Magnetic Filler Biofilm. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Innovative Solutions in Hydropower Engineering and Civil Engineering, Hangzhou, China, 25–27 September 2022; Wang, S., Li, J., Hu, K., Bao, X., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 503–513. [Google Scholar]