Abstract

Crack detection plays a pivotal role in ensuring the safety and stability of infrastructure. Despite advancements in deep learning-based image analysis, accurately capturing multiscale crack features in complex environments remains challenging. These challenges arise from several factors, including the presence of cracks with varying sizes, shapes, and orientations, as well as the influence of environmental conditions such as lighting variations, surface textures, and noise. This study introduces DAH-YOLO (Dynamic-Attention-Haar-YOLO), an innovative model that integrates dynamic convolution, an attention-enhanced dynamic detection head, and Haar wavelet down-sampling to address these challenges. First, dynamic convolution is integrated into the YOLOv8 framework to adaptively capture complex crack features while simultaneously reducing computational complexity. Second, an attention-enhanced dynamic detection head is introduced to refine the model’s ability to focus on crack regions, facilitating the detection of cracks with varying scales and morphologies. Third, a Haar wavelet down-sampling layer is employed to preserve fine-grained crack details, enhancing the recognition of subtle and intricate cracks. Experimental results on three public datasets demonstrate that DAH-YOLO outperforms baseline models and state-of-the-art crack detection methods in terms of precision, recall, and mean average precision, while maintaining low computational complexity. Our findings provide a robust, efficient solution for automated crack detection, which has been successfully applied in real-world engineering scenarios with favorable outcomes, advancing the development of intelligent structural health monitoring.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

Cracks are common infrastructure defects, particularly in constructions such as bridges, roads, and dams. These defects not only impact the appearance of these constructions, but could also pose significant safety risks [1]. Therefore, regular crack inspections are essential to ensure structural safety and maintenance. However, manual crack detection is a laborious process that requires highly skilled specialists. In addition, certain areas, such as the undersides of bridges, are difficult to access for inspections. With the development of computer vision and machine learning technologies, an increasing number of image-based automated crack detection methods have emerged [2].

From a computer vision perspective, crack detection can be categorized into three main tasks: classification, detection, and segmentation. Crack classification determines the presence or absence of cracks in an image. Majdi et al. [3] proposed a semi-automated inspection model utilizing image-processing techniques for this purpose. Crack detection employs bounding boxes to identify both the presence and location of cracks. Luo et al. [4] introduced an enhanced lightweight network, E-EfficientDet, to achieve efficient crack detection using bounding boxes. Crack segmentation, in contrast, extracts pixel-level crack regions from the image background. Wan et al. [5] propose a Context-aware Aggregation Network (CANet) to accurately pop-out the defects. Our study focuses on crack detection due to its computational efficiency, enabling the rapid identification of crack presence and location. Furthermore, in many practical applications, precise pixel-level segmentation is not required, as crack detection provides sufficient information to guide subsequent maintenance and repair decisions.

Crack detection methods are broadly classified into two types: conventional techniques and deep learning-based approaches. Conventional methods analyze fracture characteristics through digital imaging and rely on feature extraction and pattern recognition algorithms such as edge detection [6] and the Hough transform [7]. For example, Abdel-Qader et al. [8] used Fourier and Hough transformations with the Canny operator for crack edge detection, while Salman et al. [9] employed Gabor filters for automatic crack classification. Furthermore, Gunawan et al. [10] developed a motion detection application that combined a threshold function with the Canny algorithm, delivering accurate results. However, these methods exhibit limitations when applied in complex environments and under varying crack patterns, as they often fail to capture intricate details, resulting in insufficient detection accuracy. Consequently, the development of advanced automated crack detection technologies has become an urgent research priority.

With the rapid advances in deep learning technology, there has been an increasing adoption of deep learning methods for crack detection in both academic and industrial fields, enabling the accurate identification of cracks by learning crack features from extensive image datasets. However, most high-performance crack detection networks involve high computational costs. For instance, Xiang et al. [11] proposed a YOLO-based crack detection system capable of real-time identification. However, the incorporation of transformer layers enhanced performance, but at the expense of significantly increased computational complexity. Similarly, Xu et al. [12] developed a crack detection method based on Mask R-CNN, which, despite its effectiveness, has a complex model structure and high computational demands.

The challenge of crack detection arises from the irregular shapes, complex edges, and significant size variations of cracks. These cracks can be small and blend into the background, or they may span multiple spatial scales, making identification more difficult. Additionally, cracks often exhibit low contrast with their surroundings, especially in the presence of complex textures or poor lighting conditions, further complicating detection [13]. Conventional convolutional neural networks (CNNs) struggle with this issue due to down-sampling operations, which often result in the loss of essential crack characteristics. This loss reduces detection accuracy, leading to potential missed detections and a low recall rate. Recall is particularly critical in crack detection, as undetected cracks can expand over time, potentially causing structural damage or even safety hazards.

To address the limitations of existing methods regarding feature loss and computational costs, this research proposes DAH-YOLO, an enhanced crack detection model based on YOLOv8. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Standard YOLOv8 uses static kernels which limit adaptability. We introduce Dynamic Convolution to replace standard convolutions. By leveraging shared dynamic kernels, this module effectively captures complex crack features while optimizing parameter utilization and generalization capability.

- (2)

- An attention-enhanced Dynamic Head (Dyhead) is integrated to replace the traditional detection head. This mechanism refines the focus on critical feature map regions, significantly boosting detection accuracy for multi-scale cracks in complex environments.

- (3)

- Haar wavelet transformation is introduced for feature map down-sampling. Unlike the standard strided convolution in YOLOv8 which causes aliasing and detail loss, this method reduces redundant spatial information while preserving essential high-frequency edge and texture details, thereby mitigating false negatives in low-contrast conditions.

- (4)

- Comprehensive experiments demonstrate that DAH-YOLO outperforms mainstream YOLO variants and classical object detection models, offering a superior balance between robustness, accuracy, and computational efficiency.

1.2. Two-Stage Object Detection Model Based on Candidate Regions

Typical models of two-stage object detection include Mask R-CNN [14] (Mask region-based convolutional neural network), R-FCN [15] (Region-based fully convolutional networks), and Faster R-CNN [16] (faster region-based convolutional neural networks). These models operate by first generating candidate regions, followed by filtering these candidates through a classifier. The final detection frames are then refined by eliminating duplicate frames and applying non-maximal suppression (NMS).

For instance, Li et al. [17] employed an R-FCN-based deep learning algorithm combined with a sliding window and coordinate mapping technique to detect broken insulators, achieving an average accuracy of 90.5%. Similarly, Gan et al. [18] proposed a crack detection approach utilizing Faster R-CNN, training a deep learning model to identify and localize bridge cracks. This approach also facilitates the visualization of bridge fractures, contributing to a more comprehensive assessment of structural health. Hacıefendioğlu K et al. [19] used a Faster R-CNN for detecting concrete roadway defects, investigating the impact of shooting height, distance, weather conditions, and light levels on detection performance. In contrast, Pei et al. [20] adopted a cascade R-CNN model in combination with various data enhancement techniques to achieve an F1 score of 0.635 in the Global Road Damage Detection Challenge 2020 (RDD2020) [21]. Additionally, Gonthina M et al. [22] developed a convolutional neural network-based model to identify and quantify cracks using image-processing techniques. While two-stage detection models offer significant advantages in terms of accuracy, their inherent computational complexity and large model sizes pose challenges for real time detection, especially in resource-constrained environments. Therefore, in order to achieve real-time object detection, Single-stage detection algorithms have emerged.

1.3. Single-Stage Object Detection Model Based on Regression Analysis

Single-stage target detection models, which utilize regression analysis, include notable algorithms such as SSD [23] (Single Shot MultiBox Detector) and YOLO [24] (You Only Look Once). Unlike two-stage models, these algorithms perform both coordinate and category prediction in a single forward pass, bypassing the candidate frame generation step, and thereby significantly improving detection speed. However, this enhancement in detection efficiency often comes at the cost of accuracy, particularly in scenarios involving small targets or complex backgrounds. For instance, Yan et al. [25] introduced an improved SSD network, integrating deformable convolutional modules into the backbone feature extraction network. This modification effectively enhanced the detection of pavement cracks under challenging conditions, yet the performance of SSD remains limited when handling small targets in complex backgrounds. Despite this limitation, SSD still provides a notable improvement in detection efficiency compared to two-stage methods like R-CNN.

In parallel, the YOLO detection algorithm, first introduced by Redmon et al. [26] in 2015, revolutionized single-stage object detection by unifying target localization and category prediction into a single task, thereby streamlining the detection process. Nie et al. [27] developed a pavement crack detection system based on YOLOv3, which significantly boosted both detection accuracy and speed. Additionally, Xiang et al. [11] enhanced the YOLOv5 model by integrating the Transformer module, which improved the model’s ability to capture long-range dependencies and contextual knowledge of crack sites, proving particularly effective for detecting cracks with complex morphologies.

Moreover, Wan et al. [28] proposed a lightweight road defect detection algorithm, YOLO-LRDD, which effectively reduces model size while preserving detection accuracy by employing a novel backbone network, Shuffle-ECANet. This approach is optimized for deployment on mobile devices, offering a balance between performance and resource efficiency. Yang et al. [29] introduced PDNet, an efficient lightweight framework derived from enhanced YOLOv5 architecture, which demonstrates significant capabilities in model compression, detection acceleration, and multi-scale recognition accuracy. it remains limited in addressing the critical challenge of small target identification in road surface defect detection scenarios. Xiang et al. [30] proposed YOLOv5s-DSG to address small-scale road damage detection across varying resolutions, optimizing the depth and width of YOLOv5s to reduce computational overhead with minimal performance impact. Qiu et al. [31] compared the performance of YOLOv2 and YOLOv4-tiny models, based on ResNet5, for detecting small cracks in tiled sidewalks. These models are distinguished by their high precision, fast processing speed, and lightweight design. However, their relatively low model complexity and fewer parameters restrict their ability to capture subtle details. In cases where crack edges are unclear or lighting conditions vary, the detection performance of these models is notably compromised. Further advancements has been made by Lan et al. [32], who introduced a cross-scale fusion module into YOLOv8 to enhance feature fusion capabilities, resulting in improved defect detection performance. Gao et al. [33] introduced BL-YOLOv8, a YOLOv8-based variant featuring a redesigned neck structure with BiFPN integration to reduce both parameter size and computational demands. Similarly, Wang et al. [34] proposed a lightweight detection model using YOLOv8 as a baseline, integrating the VaniIIaNet network and the SPD (Space-to-Depth) module to maintain high detection accuracy while reducing computational resource consumption.

Despite advancements in balancing accuracy and resource efficiency, detecting small or indistinct cracks under complex conditions remains challenging. Low contrast, varying crack widths, and background noise often hinder the accuracy and robustness of detection models. Existing methods struggle to generalize across scenarios or require high computational resources, highlighting the need for more efficient and effective crack detection solutions to ensure reliability and practical application in real-world settings.

2. Proposed Model

2.1. YOLOv8 Network Architecture

In this paper, YOLOv8 was chosen as the baseline model, comprising three components: the backbone, neck, and detection head. The backbone extracts essential image features through convolutional layers, while the neck aggregates and processes these features. The detection head predicts target categories and positions using three detectors at different scales, enabling recognition of objects of varying sizes.

2.2. Overview of the Proposed Method

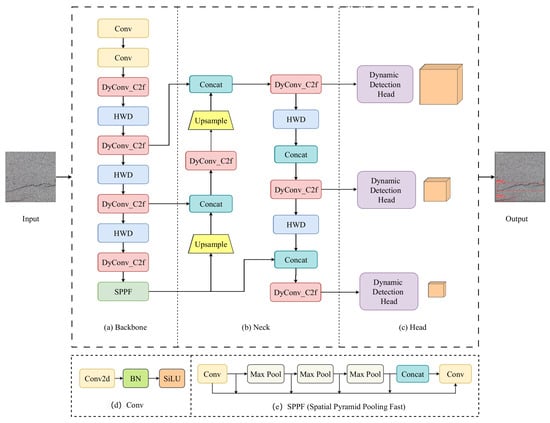

The structure of the DAH-YOLO model proposed in this study is shown in Figure 1. This model builds on YOLOv8 with three key modifications to enhance crack detection performance. First, we introduce the dynamic convolution module (DyConv_C2f) to replace the original C2f (Concatenate 2 fused layers) module. Unlike the fixed convolution kernel in C2f, DyConv_C2f dynamically adjusts convolution kernel parameters across different regions. This adaptive approach enhance parameter utilization, effectively capturing complex crack features, while simultaneously reducing computational complexity. Secondly, we introduce a dynamic detection head (Dyhead) to replace the original YOLOv8 detection head. Dyhead integrates scale, spatial and task awareness through self-attention mechanisms. Particularly, the scale awareness mechanism improves detail detection for small cracks and preserves structure for larger ones. The spatial awareness mechanism focuses on crack regions while reducing irrelevant background information, minimizing false detections. Finally, to optimize the retention of crack features and minimize the loss of essential information, we employ Haar wavelet down-sampling (HWD), a technique that more effectively preserves essential features, reducing the likelihood of information leakage and misdetection.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed DAH-YOLO. (a) The backbone network for feature extraction; (b) The neck network for feature fusion; (c) The dynamic detection heads; (d) Structure of the Conv module; (e) Structure of the SPPF module.

The novelty of DAH-YOLO lies in the strategic integration of these three components, which creates a complementary effect. This synergistic design positions DAH-YOLO as a specialized solution superior to generic YOLO variants for surface crack detection.

2.3. Dynamic Convolution Module

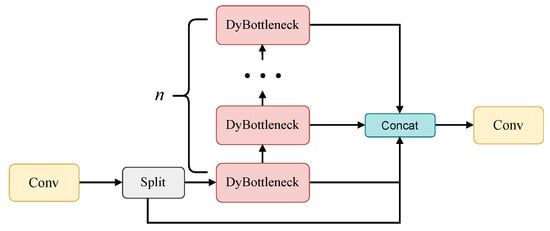

The C2f (Concatenate 2 fused layers) module of YOLOv8 functions as the primary residual learning module. It incorporates the benefits of the ELAN (Efficient Layer Aggregation Networks) structure from YOLOv7 [35], reducing one standard convolutional layer while optimizing the bottleneck module to strengthen the gradient branch. This approach effectively retains the lightweight characteristics of the network while capturing more abundant gradient flow information. However, this design increases the number of output channels and parameters, which impacts parameter utilization efficiency. To address this, we propose the DyConv_C2f module, in which dynamic convolution is adopted. The structure of the proposed DyConv_C2f module is illustrated in Figure 2. The feature map initially passes through a convolution block to extract basic features and generate an intermediate feature map. Following the Split layer, the intermediate feature map is divided into two parts: one is directly sent to the Concat block, while the other is fed into the DyBottleneck module in sequence. Within the DyBottleneck modules, the input feature maps undergo dynamic convolution, and the resulting feature maps are fused in the Concat block.

Figure 2.

DyConv_C2f Structure diagram.

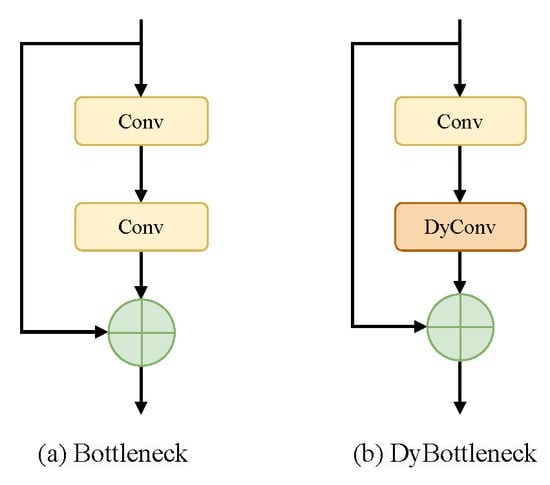

The proposed model replaces the second convolutional block in the original Bottleneck module with dynamic convolution, as illustrated in Figure 3. The first convolutional block reduces the number of channels, thereby lowering computational complexity, while the second dynamic convolutional block extracts additional features to enhance the model’s expressive capacity. Traditional convolutional layers, which use fixed weights, lack adaptability during inference, relying on the same kernel regardless of variations in the input features. This limitation restricts the model’s ability to capture the complex characteristics of cracks. In contrast, the dynamic convolutional layer adaptively selects and weights multiple kernels based on the input data, providing greater flexibility to accommodate varying features. This architecture enhances the feature representation and adaptability of the neural network while maintaining low computational complexity.

Figure 3.

Bottleneck and DyBottleneck.

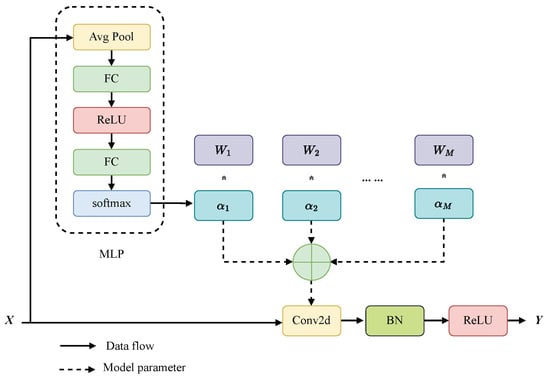

The dynamic convolution structure is illustrated in Figure 4. Given the input feature and the weight tensor , the output of the conventional convolutional layer is as follow:

where , and ∗ represents the convolution operation. To keep the FLOPs low while adding more parameters, we introduce a parameter enhancement function :

Figure 4.

Dynamic convolution structure diagram.

In this paper, dynamic convolution is employed as a parameter enhancement mechanism. The dynamic convolution module comprises M convolutional kernels, all sharing the same kernel size as well as input-output dimensions. These kernels are weighted and aggregated based on attention weights . Following the aggregation, the dynamic convolutional layer is constructed by incorporating batch normalization and activation function. The computation of the dynamic convolution with M convolutional kernels is as follows:

where is the i -th convolutional weight tensor and is the corresponding dynamic coefficient. The primary strategy relies on generating inputs from the MLP (Multilayer Perceptron) module. This MLP module utilizes a compression and excitation mechanism to compute the kernel attention weights . Initially, Global spatial information is compressed and fused into a vector via global average pooling. Subsequently, two fully connected layers (with a ReLU activation in between) and softmax function are applied to construct the normalized attention weight coefficients for the M convolutional kernels. The computation is as follows:

where .

Unlike the C2f module, the DyConv_C2f module dynamically selects different convolution kernels for each input. The feature visualization in Figure 5 clearly demonstrates the differences between the C2f module and the DyConv_C2f module features. This adaptive approach significantly enhances parameter utilization efficiency and adaptability to diverse input features. Consequently, the model’s generalization capacity is increased, ensuring stable and accurate performance in complex environments.

Figure 5.

Visualization of C2f and DyConv_C2f feature maps at different layers.

2.4. Dynamic Detection Head

The YOLOv8 detection head consists of multiple convolutional layers for feature extraction and target localization. While it effectively supports multi-scale object detection, it encounters difficulties when dealing with cracks that exhibit elongated and irregular morphologies, as well as complex features such as blurred edges. The fixed size and orientation of the convolutional kernels limit the model’s ability to capture these intricate details, resulting in missed or misdetected cracks.

Additionally, the lack of an explicit attention mechanism reduces the model’s spatial and channel selectivity, making it challenging to focus on relevant crack regions. This limitation decreases the model’s robustness against complex backgrounds, increasing susceptibility to external noise and compromising detection accuracy.

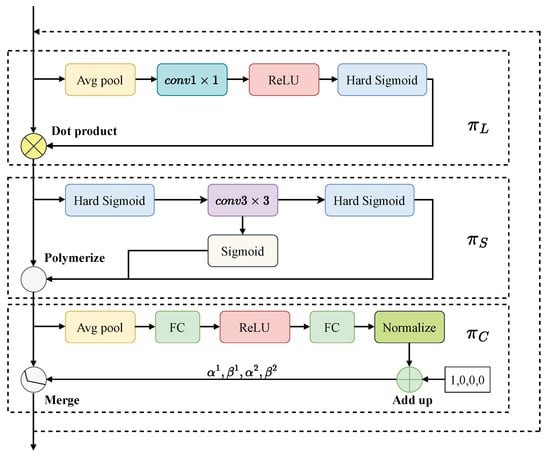

To address these issues and further improve detection performance, this paper proposes the adoption of a dynamic head (Dyhead) block that integrates scale-awareness, spatial-awareness and task awareness into a unified framework. The effective implementation of the attention mechanism within this detection head significantly improves crack detection capabilities. The structure of the dynamic head block is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Dyhead block.

In Figure 6, represents scale-aware attention, formulated as:

where is a four-dimensional tensor, with L as the number of layers, H and W as height and width, and C as the number of feature channels. The tensor is reshaped into with , and the function is approximated by a convolutional layer, followed by a hard sigmoid function .

By merging information from different feature layers, enhances the model’s discriminative capacity in complex backgrounds, enabling accurate crack detection even with blurred edges or poor lighting. This fusion of multi-layers features improves the model’s ability to capture fine crack details, resulting in exceptional detection performance in challenging scenarios.

represents spatial-aware attention, formulated as:

This two-step approach employs deformable convolution for sparse attention learning and aggregates features at the same spatial locations. Here, denotes the weights in the convolutional kernel, and K represents the number of sparsely sampled locations, with focusing on discriminative regions, while captures self-learned importance.

denotes task-aware attention, formulated as:

where represents the feature maps for the c-th channel. The vector is a hyper function that learns to control the activation threshold. The hyper function is implemented via global average pooling, fully connected layers, and a normalized sigmoid function [36].

intelligently adjusts the model’s attention across different feature layers based on the specific needs of crack detection. For fine crack identification, the model relies more on low-level spatial detail features, whereas for large-scale cracks, it prioritizes high-level semantic information. This dynamic adjustment enables the model to effectively recognize both fine and large cracks.

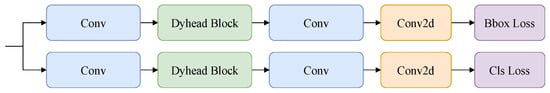

Based on the Dyhead block, we have reconstructed the model’s detection head, as shown in Figure 7. The architecture consists two branches: one for bounding box prediction and the other for category prediction. Feature pyramids from the Neck network are passed through convolution blocks to form a 3D tensor , which serves as input to the dynamic detection head. The output from Dyhead block are then forwarded to a convolution block, and final predictions are made through two Conv2d layers.

Figure 7.

Dynamic detection head structure.

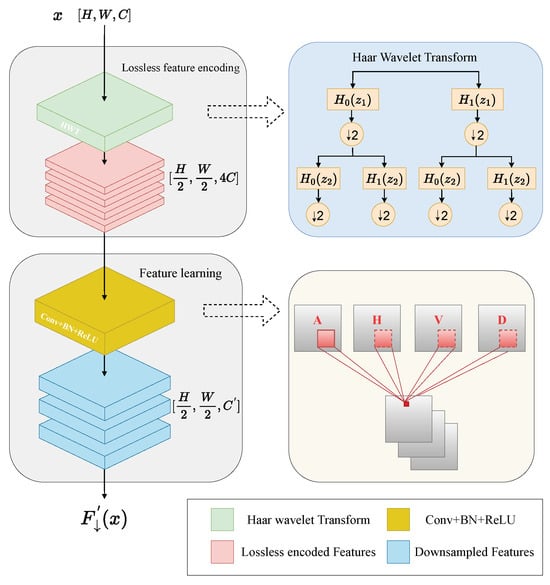

2.5. Haar Wavelet Down-Sampling Module

YOLOv8 primarily achieves down-sampling through convolutional strides. When the stride is set to 2, the convolution kernel advances two pixels at a time, effectively halving the spatial dimensions of the feature map. While effective, this can result in the loss of critical information, especially for subtle cracks. To address this, we introduce the Haar wavelet down-sampling module, which enhances information retention by increasing the number of channels and applying the Haar wavelet transform for down-sampling. The model then use convolution operations to extract representative features and filter out redundant information. The structure of this module is illustrated in Figure 8, which consists of two components: the lossless feature encoding block and the feature learning block.

Figure 8.

Haar wavelet down-sampling module.

The lossless feature encoding block uses the Haar wavelet transform to reduce feature map spatial resolution while preserving all information. Low-pass () and high-pass () filters extract low and high frequency information, respectively. With downsampling () generating four components: the approximate (low-frequency) component (A), as well as the detail components (high-frequency) in the horizontal (H), vertical (V), and diagonal (D) directions. Each component’s size and resolution are , while the channel count quadruples. The Haar wavelet transform can encode spatial information into the channel dimension without loss. Thereafter, the low-frequency and high-frequency components are concatenated along the channel dimension to generate a new tensor. Consequently, the subsequent convolutional layers are able to extract representative features from the transformed components, which have reduced spatial resolution.

The feature learning block integrates a convolution with batch normalization and ReLU activation, optimizing feature map channels for subsequent layers while eliminating redundant information to improve computational efficiency.

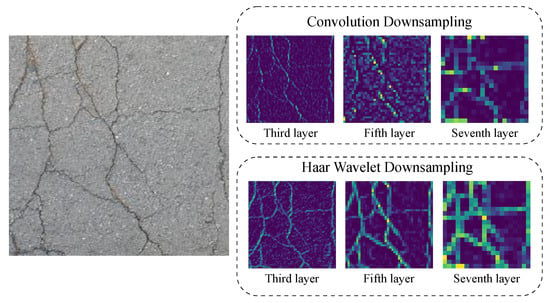

The feature visualization in Figure 9 clearly demonstrates the differences between the Convolution Down-sampling and Haar Wavelet Down-sampling features. Overall, the Haar wavelet transform preserves critical image details, improving detection accuracy and multi-scale information of cracks. This approach significantly enhances recognition of edge features and complex morphological changes, boosting the model’s robustness and accuracy in crack detection and reducing leakage and false detections.

Figure 9.

Visualization of Convolution Down-sampling and Haar Wavelet Down-sampling feature maps at different layers.

3. Experimental Analysis

3.1. Experimental Datasets

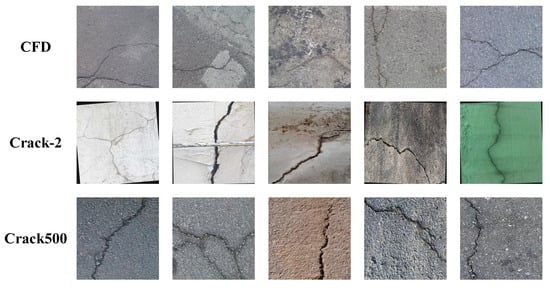

In this article, the proposed DAH-YOLO is thoroughly evaluated on three publicly available datasets: CFD [37], Crack-2 [38], and Crack500 [13], with samples shown in Figure 10. Additionally, ablation analysis experiments were conducted using the Crack500 dataset. All the datasets were divided into training, validation, and testing sets in the proportions of 70%, 20%, and 10%, respectively.

Figure 10.

Some samples from three datasets.

- (1)

- CFD [37]: This dataset includes 584 images of size , collected using an iPhone 5 on an urban pavement in Beijing, China. All images have the real contours of the cracks traced by hand. This dataset poses significant challenges due to its dynamic background, which includes shadows, oil patches, water stains, and zebra crossings.

- (2)

- Crack-2 [38]: This dataset contains a total of 3102 images recorded in various road and wall scenarios, with an approximate image size of 416 by 416 pixels. The dataset includes a diverse array of images taken in different locations, environments, and densities.

- (3)

- Crack-500 [13]: This dataset is dedicated to the detection and identification of concrete cracks containing 9972 images with corresponding pixel-level annotations. The images have a resolution of and were captured using smartphones around Temple University. The images were taken from different concrete structures under varying angles and lighting situations; thereby encompassing images of cracks in shadows, occlusions, and diverse lighting environments.

3.2. Experimental Environment

To ensure experimental fairness and reproducibility, a strictly controlled protocol was implemented for all comparisons. The specific hardware and software environments are detailed in Table 1, while the consistent hyperparameter configurations used throughout the training process are specified in Table 2. Crucially, to mitigate the sensitivity to random initialization, all models were initialized using official pre-trained weights from the YOLOv8 repository (COCO dataset) and trained with a fixed random seed (set to 0). While we report the best performance metrics from these fixed-seed runs due to computational constraints, we acknowledge the potential existence of statistical variance. However, previous studies on YOLO architectures suggest that when using pre-trained backbones, the performance variance across different seeds is typically marginal. Consequently, given that DAH-YOLO outperforms the baseline YOLOv8 by a significant margin, we contend that the observed improvements are statistically meaningful and not merely artifacts of random variance.

Table 1.

Configuration and training environment.

Table 2.

Implementation details and hyper-parameter settings for all baseline models.

3.3. Performance Metrics

Five widely detection evaluation metrics are employed: Precision (Pr), Recall (Re), F1 score, mean Average Precision at IoU threshold 0.5 () and mean Average Precision across IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 (). Additionally, Giga Floating Point Operations Per Second (GFLOPS) is used to compare the complexity of models. The lower the GFLOPs, the lower the number of floating-point operations the model needs to complete and the higher the computing efficiency. These metrics are defined as follows:

where , , and refer to the true positive, false positive, and false negative, respectively.

3.4. Complexity Analysis

For the standard convolutional layer, the number of parameters is and the number of parameters is . The dynamic convolution consists of three components: the coefficient generation module, dynamic weight fusion, and the convolution process. The coefficient generation module, which has hidden dimensions, requires parameters and the same number of FLOPs. Dynamic weight fusion is parameter-free and incurs FLOPs. Therefore, the total number of parameters and FLOPs for dynamic convolution are: and respectively, where , , .

The parameter and FLOPs ratios of dynamic convolution over standard convolution are:

Therefore, compared to standard convolution, the number of parameters in dynamic convolution is approximately M times, while the additional FLOPs are negligible.

3.5. Results Comparison

This subsection conducts experiments on three public datasets, and compares with other object detection models, like YOLOv3 [39], YOLOv5 [40], YOLOv6 [41], YOLOv8n [42], YOLOv9 [43], YOLOv10 [44], Faster-RCNN, and SSD. All model parameter values were kept consistent based on the principle of regulating variables.

- (1)

- Results on the CFD Dataset

The crack regions in the CFD dataset are extremely narrow, posing a challenge for the model’s sensitivity in detecting fine-grained crack regions. As listed in Table 3, our model achieved the highest performance in terms of recall (Re), mAP@0.5, and F1-score. Specifically, the proposed model attained the highest F1-score of 84.2%, which assesses the balance between precision and recall. SSD, as a single-stage target detection model, exhibits limited detection performance. The mAP@0.5 score of Faster-RCNN is 78.2%, indicating that, as a two-stage detection technique, it achieves high detection accuracy by generating candidate regions and applying classification and bounding-box regression. However, the structure of Faster-RCNN is complex, and the computational complexity is substantial.

Table 3.

Results on the CFD Dataset.

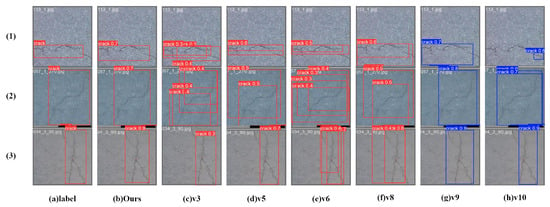

Figure 11 illustrates the qualitative comparison on the CFD dataset. The YOLOv3-tiny model comprises only 7 convolutional layers, which cannot extract visual characteristics at a deep level. Therefore, it is not effective in tasks such as identifying cracks. While YOLOv5 yields comparable metrics, its bounding boxes often lack spatial precision. Furthermore, YOLOv9 and YOLOv10 struggle to suppress background noise and often overlook subtle crack branches. In contrast, our method effectively filters irrelevant noise and captures fine-grained crack details more accurately, producing results that most closely align with the ground truth.

Figure 11.

Visualization of testing results on the CFD dataset.

- (2)

- Results on the Crack-2 Dataset

Compared with the CFD dataset, the background of the Crack-2 dataset is more complex and contains various interferences, such as dirt and debris. As shown in Table 4, the proposed model outperforms other models in terms of all metrics except for precision metric. Specifically, our precision is 83%, which is 5.1% lower than YOLOv5, while YOLOv5’s recall rate is only 64.7%, which is 6.9% lower than ours. Overall, the proposed network demonstrates stronger performance.

Table 4.

Results on the Crack-2 dataset.

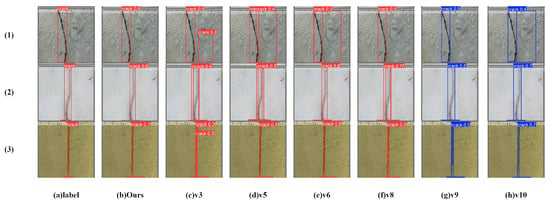

To clearly highlight the advantages of the proposed model, several samples from the Crack-2 dataset are selected for intuitive comparison. As demonstrated in Figure 12, the YOLOv3-v6 and YOLOv10 not only misclassify the normal texture of the wall as a crack, but also exhibit poor confidence in the crack prediction box. In contrast, the model presented in this article displays greater robustness and higher detection accuracy in complex scenarios with diverse background colors and distracting textures, completely avoiding misclassification and demonstrating its superior identification capability.

Figure 12.

Visualization of testing result on the Crack-2 Dataset.

- (3)

- Results on the Crack500 Dataset.

In Crack500 dataset, crack areas are relatively wide, but have a more complex structure. Compared to the other two datasets, this one not only has a larger number of samples but also features higher resolution images, making it more suitable for the proposed model. As listed in Table 5, the proposed model demonstrated significantly superior performance in terms of all metrics except for GFLOPS. It outperforms the second-best methods on Pr, Re, mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5:0.95 and F1 by 2.2%, 7.7%, 5.2%, 7.8%, and 5.3%, respectively. Although the GFLOPS metric of YOLOv5 and YOLOv9 is slightly better than that of our method, their other metrics are far lower than our method.

Table 5.

Results on the Crack500 dataset.

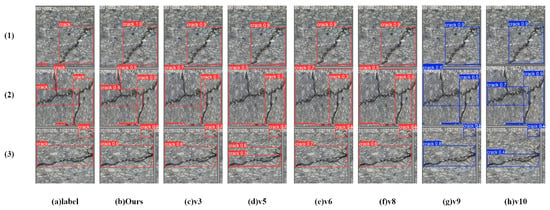

Figure 13 show several detection results. Obviously, the proposed model not only demonstrates high confidence in its predictions but also achieves outstanding detection performance, especially for cracks with complex topological structures (as illustrated in Figure 13(2)).

Figure 13.

Visualization of testing results on the Crack500 dataset.

3.6. Comparison with Other Models

To further validate the proposed model’s effectiveness, it was compared with three other dedicated crack detection methods, YOLO-LRDD [28], YOLOv5s-DSG [30], BL-YOLOv8 [33] on the CFD, Crack-2 and Crack500 datasets, with the results displayed in Table 6. All three comparison models were reproduced using open-source implementations and evaluated with the same hyperparameters as the proposed model to ensure a fair comparison.

Table 6.

Comparison with other models.

The proposed model was compared with YOLO-LRDD across three datasets. YOLO-LRDD, which employs ShuffleECA-Net for feature extraction, reduces computational demands through channel splitting and shuffling but struggles with irregular and diverse cracks due to information loss during integration and down-sampling, particularly for microscopic cracks. In contrast, the proposed model with its dynamic inspection head, improves complex crack detection. On the CFD dataset, it achieved 84.5% accuracy, outperforming YOLO-LRDD’s 77.8%, and demonstrated superior recall and F1 score through a multiple-attention mechanism, effectively enhancing multi-scale crack detection.

Comparative results with YOLOv5s-DSG on the Crack500 dataset indicate that while YOLOv5s-DSG utilizes GhostNet convolutional module decreases computational complexity by producing several low-computation feature maps in lieu of conventional convolutional computation, but it often loses crack features, leading to reduced accuracy in high-resolution images. The Haar wavelet down-sampling module introduced here effectively retains key features, achieving precision and recall rates of 90.2% and 84.9%, significantly higher than YOLOv5s-DSG’s 88.5% and 79.9%.

Compared to the BL-YOLOv8 model, which uses BiFPN for iterative multi-scale feature fusion and LSK-attention for global feature weighting, resulting in high computational complexity with 25.5 GFLOPs, our proposed model adopts a dynamic convolution design with only 7.9 GFLOPs. By optimizing the C2f structure of YOLOv8, it achieves adaptability to diverse input features, offering greater efficiency and accuracy without substantial computational overhead.

3.7. Generalization Experimental Verification

We conducted additional generalization experiments using practically collected datasets. The data acquisition site was situated at the confluence of the Luozhou River (Nantai Island) and the Wulong River within the Minjiang Main Stream Flood Control Improvement Project (as illustrated in Figure 14), specifically focusing on the cracks on the inner wall of the newly constructed Phase I Luocheng Sluice chamber. The image acquisition was performed using a DJI AIR3S dual-camera travel drone, which was positioned at a distance of 1–2 m from the sluice wall and operated in a frontal photography mode to ensure clear capture of crack features. The onboard camera was the DJI FC9184 model, equipped with a -inch CMOS medium-telephoto sensor. Key technical parameters of the camera are as follows: Effective pixels: 48 million; Aperture: ; Image resolution: pixels. This setup ensured high-quality image acquisition with sufficient detail to capture subtle crack features. These datasets include 200 images with subtle cracks, and 100 images with complex backgrounds (containing graffiti, surface labels, and varied concrete textures).

Figure 14.

Photos of the on-site shooting location.

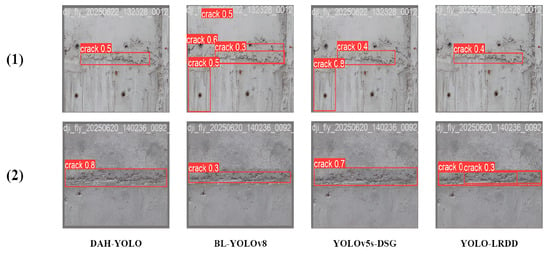

Figure 15 illustrates the generalization performance on the drone dataset. In Row 1, where surface stains mimic crack features, BL-YOLOv8 and YOLOv5s-DSG produced significant false positives. In contrast, DAH-YOLO robustly distinguished true cracks from background noise. In Row 2, YOLO-LRDD failed to maintain continuity, resulting in fragmented detections for long cracks, whereas DAH-YOLO successfully preserved feature integrity with a single, high-confidence bounding box (). These results confirm DAH-YOLO’s superior adaptability to real-world interference compared to other state-of-the-art models.

Figure 15.

Generalization verification effect on actual datasets.

3.8. Validation on Cross-Datasets

To evaluate the model’s generalization and adaptability, we performed cross-dataset validation on three datasets of different scales. As presented in Table 7, the model exhibits optimal performance when the training and test sets are identical, achieving precision rates of 84.5%, 83%, and 90.2%, along with recall rates of 84%, 71.6%, and 84.9% for CFD, Crack-2, and Crack500, respectively. However, training with CFD results in limited test performance on larger datasets such as Crack-2 and Crack500. Training on Crack-2 enhances performance on the CFD test set, resulting in 66.5% precision and 64% recall; however, the model continues to face challenges with the larger Crack500 test set. Conversely, training on Crack500 significantly improves performance across both the CFD and Crack-2 test sets, demonstrating robust generalization and adaptability. This indicates that the proposed network has superior cross-dataset generalization capability and resilience in crack detection.

Table 7.

Results of the model on cross-datasets.

3.9. Ablation Experiment

To evaluate each module’s effectiveness in the proposed model, we conducted ablation experiments on the Crack500 dataset, with results presented in Table 8. Compared to the based model, YOLOv8, the addition of the dynamic convolution module decreases the model’s floating-point operations by 1.3 billion and increases the Re, mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5:0.95, and F1 scores by 1.8%, 1.1%, 1.4%, and 0.2%, respectively. Although the introduction of the dynamic convolution module results in a slight drop in accuracy, its optimization in terms of computational efficiency is evident.

Table 8.

Ablation experiment results on the Crack500.

Further introducing the dynamic detecting head significantly improves the model’s performance on Pr, Re, mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5:0.95, and F1 scores by 6.9%, 7.7%, 8.4%, 11.6%, and 7.4%, respectively. This indicates that the dynamic detection head effectively enhances feature extraction capabilities and regression accuracy. Additionally, after implementing the Haar wavelet down-sampling module, the model’s Pr, Re, mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5:0.95, and F1 improve by 3.9%, 5%, 4.3%, 5.7%, and 4.5%, respectively. This demonstrates the Haar Wavelet down-sampling module’s ability to capture detailed information from the scaled feature maps, particularly edge and texture features, thereby further improving detection accuracy.

In summary, compared to the baseline model YOLOv8, the enhanced model achieves 9%, 14.5%, 13.8%, 18.7%, and 12.1% improvement in Pr, Re, mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5:0.95, and F1 scores, respectively, along with a reduction of 300 million floating-point operations. The results of the ablation experiments reveal that the joint application of the three revised algorithms not only yields the best crack detection results but also effectively reduces the model’s computational complexity.

4. Conclusions

To enhance detection accuracy without increasing the computational complexity, the DAH-YOLO network proposed in this study introduces the dynamic convolution-based DyConv_C2f module. The module adaptively selects multiple convolutional kernels based on the input characteristics, facilitating more flexible and dynamic feature extraction. Additionally, the incorporation of the dynamic detection head further improves the model’s accuracy; the Haar wavelet down-sampling module is also introduced to capture more detailed information in the scale feature maps, particularly with regard to edge and texture features, thereby improving the detection accuracy of the model. Experiments conducted on three public datasets and in practical engineering scenarios have verified the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed method.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F. and Q.L.; methodology, Y.F.; software, Q.L.; validation, Q.L. and W.Z.; formal analysis, Q.L.; investigation, Y.C. and Z.Y.; resources, Y.S.; data curation, Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.F.; visualization, Z.Y.; supervision, Y.S.; project administration, Y.F.; funding acquisition, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project ‘The Key Technologies and Applications of the Min Jiang Mainstream Flood Control Enhancement Project (Fuzhou Section) for Efficient, Safe, and Intelligent Management’ grant number 824081116.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

For details of the data sources supporting the report results, please refer to the references.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Ye Chen was employed by the company Minjiang Lower Reaches Flood Control Engineering Construction Co., Ltd., Zhiqiang Yao was employed by the company Water Conservancy Investment and Construction Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Mohan, A.; Poobal, S. Crack detection using image processing: A critical review and analysis. Alex. Eng. J. 2018, 57, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, H.S.; Hammad, A.W.; Haddad, A.; Soares, C.A.P.; Waller, S.T. Image-based crack detection methods: A review. Infrastructures 2021, 6, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flah, M.; Suleiman, A.R.; Nehdi, M.L. Classification and quantification of cracks in concrete structures using deep learning image-based techniques. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 114, 103781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Li, C.; Wu, M.; Cai, L. An enhanced lightweight network for road damage detection based on deep learning. Electronics 2023, 12, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, B.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, B.; Xiao, M.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, J.; Yan, C. CANet: Context-aware aggregation network for salient object detection of surface defects. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2023, 93, 103820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, F.A.; Vanzella, W.; Torre, V. Edge detection revisited. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part B (Cybern.) 2004, 34, 1500–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenfried, K. Processing calibration-grid images using the Hough transformation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2002, 13, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Qader, I.; Pashaie-Rad, S.; Abudayyeh, O.; Yehia, S. PCA-based algorithm for unsupervised bridge crack detection. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2006, 37, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Mathavan, S.; Kamal, K.; Rahman, M. Pavement crack detection using the Gabor filter. In Proceedings of the 16th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC 2013), The Hague, The Netherlands, 6–9 October 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 2039–2044. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan, G.; Nuriyanto, H.; Sriadhi, S.; Fauzi, A.; Usman, A.; Fadlina, F.; Dafitri, H.; Simarmata, J.; Utama Siahaan, A.P.; Rahim, R. Mobile application detection of road damage using canny algorithm. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1019, 012035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Wang, Z.; Qiao, Y. An improved YOLOv5 crack detection method combined with transformer. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 14328–14335. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Zhao, M.; Shi, P.; Ren, R.; He, X.; Wei, X.; Yang, H. Crack detection and comparison study based on faster R-CNN and mask R-CNN. Sensors 2022, 22, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, L.; Yu, S.; Prokhorov, D.; Mei, X.; Ling, H. Feature pyramid and hierarchical boosting network for pavement crack detection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 21, 1525–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J.; Li, Y.; He, K.; Sun, J. R-FCN: Object detection via region-based fully convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 5–10 December 2016; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 29. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhou, H.; Wang, G.; Zhu, X.; Kong, L.; Hu, Z. Cracked insulator detection based on R-FCN. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1069, 012147. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, L.; Liu, H.; Yan, Y.; Chen, A. Bridge bottom crack detection and modeling based on faster R-CNN and BIM. IET Image Process. 2024, 18, 664–677. [Google Scholar]

- Hacıefendioğlu, K.; Başağa, H.B. Concrete road crack detection using deep learning-based faster R-CNN method. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2022, 46, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Lin, R.; Zhang, X.; Shen, H.; Tang, J.; Yang, Y. CFM: A consistency filtering mechanism for road damage detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–13 December 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 5584–5591. [Google Scholar]

- Arya, D.; Maeda, H.; Ghosh, S.K.; Toshniwal, D.; Omata, H.; Kashiyama, T.; Sekimoto, Y. Global road damage detection: State-of-the-art solutions. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–13 December 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 5533–5539. [Google Scholar]

- Gonthina, M.; Chamata, R.; Duppalapudi, J.; Lute, V. Deep CNN-based concrete cracks identification and quantification using image processing techniques. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 24, 727–740. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2016, Proceedings of the 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016, Proceedings, Part I; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P.; Ergu, D.; Liu, F.; Cai, Y.; Ma, B. A Review of Yolo algorithm developments. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 199, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Zhang, Z. Automated asphalt highway pavement crack detection based on deformable single shot multi-box detector under a complex environment. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 150925–150938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, M.; Wang, C. Pavement Crack Detection based on yolo v3. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Safety Produce Informatization (IICSPI), Chongqing, China, 28–30 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 327–330. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, F.; Sun, C.; He, H.; Lei, G.; Xu, L.; Xiao, T. YOLO-LRDD: A lightweight method for road damage detection based on improved YOLOv5s. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2022, 2022, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Luo, W. PDNet: Improved YOLOv5 nondeformable disease detection network for asphalt pavement. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 5133543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, W.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Duan, Y. Road disease detection algorithm based on YOLOv5s-DSG. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2023, 20, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Lau, D. Real-time detection of cracks in tiled sidewalks using YOLO-based method applied to unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) images. Autom. Constr. 2023, 147, 104745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Zhu, H.; Luo, R.; Ren, Q.; Chen, C. PCB defect detection algorithm of improved YOLOv8. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Image, Vision and Computing (ICIVC), Dalian, China, 27–29 July 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Gao, H.; Jia, Z.; Li, Z. BL-YOLOv8: An improved road defect detection model based on YOLOv8. Sensors 2023, 23, 8361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunmei, W.; Huan, L. YOLOv8-VSC: Lightweight algorithm for strip surface defect detection. J. Front. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2024, 18, 151. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Dai, X.; Liu, M.; Chen, D.; Yuan, L.; Liu, Z. Dynamic ReLU. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Proceedings of the 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020, Proceedings, Part XIX; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 351–367. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Cui, L.; Qi, Z.; Meng, F.; Chen, Z. Automatic road crack detection using random structured forests. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 17, 3434–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crack Dataset. 2022. Available online: https://universe.roboflow.com/university-bswxt/crack-bphdr (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Farhadi, A.; Redmon, J. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 1804, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wu, J.; Tian, Y.; Tang, H.; Guo, X. Real-time vehicle detection based on improved yolo v5. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terven, J.; Córdova-Esparza, D.M.; Romero-González, J.A. A comprehensive review of yolo architectures in computer vision: From yolov1 to yolov8 and yolo-nas. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2023, 5, 1680–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Mark Liao, H.Y. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2024, Proceedings of the 18th European Conference, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024, Proceedings, Part XXXI; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14458. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.