Abstract

Climate change has exacerbated flood risks for urban infrastructure, rendering sewage treatment facilities (STFs) particularly vulnerable due to their typical low-lying topographic placement. However, conventional flood risk assessment methodologies often rely solely on physical hazard parameters such as inundation depth, neglecting the functional interdependencies and operational criticality of individual treatment units. To address this limitation, this study proposes the Integrated Hydro-Operational Risk Assessment (IHORA) framework. The IHORA framework synthesizes 2D hydrodynamic modeling with a modified Hazard and Operability Study(HAZOP) study to systematically identify unit-specific physical failure thresholds and employs the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to quantify the relative operational importance of each process based on expert elicitation. The framework was applied to an underground STF under both fluvial flooding and internal structural breach scenarios. The results revealed a significant risk misalignment in traditional assessments; vital assets like electrical facilities were identified as high-risk hotspots despite moderate physical exposure, due to their high operational weight. Furthermore, Cause–Consequence Analysis (CCA) was utilized to trace cascading failure modes, bridging the gap between static risk metrics and dynamic emergency response protocols. This study demonstrates that the IHORA framework provides a robust scientific basis for prioritizing mitigation resources and enhancing the operational resilience of environmental facilities.

1. Introduction

Climate change has demonstrably accelerated the hydrological cycle, leading to a global increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme rainfall events [1]. These climatic shifts have exacerbated the risk of severe urban flooding, posing critical threats to essential infrastructure systems that form the backbone of modern cities [2]. Among these, Sewage Treatment Facilities (STFs) are particularly vulnerable due to their inherent topographical placement; they are typically situated in low-lying areas to facilitate gravity-driven wastewater collection [3]. Consequently, even minor inundation events can severely disrupt treatment processes [4]. Such disruptions not only compromise the facility’s operational integrity but also lead to the uncontrolled release of untreated pollutants into receiving water bodies, triggering secondary environmental hazards and posing significant public health risks [5,6].

Despite these high stakes, traditional Flood Risk Assessment methodologies for environmental facilities have exhibited significant limitations. Conventional approaches have predominantly focused on hydrodynamic modeling to map physical hazard parameters, such as flood extents, inundation depths, and flow velocities [7]. While these hydraulic metrics are essential for understanding external exposure, they often fail to capture the internal operational vulnerabilities of complex industrial plants [8]. For instance, recent studies utilizing 1D or 2D hydraulic models have successfully quantified flood hazards at the site level [9,10]. However, these assessments frequently treat the facility as a homogeneous entity, neglecting the distinct functional criticality of individual treatment units [11]. This lack of granularity presents a critical gap in current risk management strategies. Process engineers recognize that the impact of flooding is highly non-linear and context dependent [12]. As an illustration, two areas with comparable flood depths can pose drastically different risks depending on the equipment they house—for example, a critical electrical control room versus an unused clarifier basin. Even a few centimeters of water intrusion into a Motor Control Center (MCC) can precipitate an immediate, plant-wide shutdown [13], whereas deeper flooding in non-essential storage areas may be temporarily manageable without halting operations. Therefore, a purely hydraulic assessment provides limited insight into the operational sustainability of STFs during flood events. To address the multifaceted nature of flood risks, recent scholarship has emphasized the need for integrated, Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) approaches [14]. A growing body of literature has demonstrated the efficacy of combining hydrodynamic simulations with Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to assess flood susceptibility with higher spatial precision [15,16]. In particular, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) has been widely adopted to assign quantitative weights to various risk factors based on expert judgment, allowing for a more nuanced evaluation of complex systems [17,18]. Numerous studies have successfully applied AHP-GIS frameworks to map flood risks at regional or watershed scales, incorporating factors such as topography, land use, and drainage density [19,20]. However, a critical review of existing literature reveals that most MCDA-based flood risk assessments remain focused on regional hazard mapping or community-level resilience [21,22]. There is a paucity of research that specifically targets the functional operability of industrial facilities at the unit process level. Standard risk metrics, which rely solely on external water depth and velocity, often fail to account for the intricate interdependencies and cascading failure modes characteristic of STFs. Furthermore, while HAZOP studies are standard in process safety management, their application to flood-induced scenarios remains underexplored. These approaches often fail to capture the functional operability of specific industrial units. Unlike traditional methods that rely solely on physical exposure, the proposed IHORA framework integrates hydraulic intensity with operational criticality. This distinction is vital because facility operators inherently know which assets are important but often lack a quantitative metric that links dynamic flood depths to specific functional failure thresholds. By converting qualitative expert intuition into a quantitative index, IHORA enables automated decision-making and prioritizes resources not just to the most inundated areas, but to the most operationally sensitive assets.

This study introduces the IHORA Framework for STFs, which bridges the gap between conventional hydraulic analysis and operational risk management. The framework comprises three key components: (1) 2D hydrodynamic modeling to resolve flood severity; (2) a modified HAZOP study to identify unit-specific failures under flood scenarios; and (3) the AHP method to evaluate the relative criticality of each treatment unit. Synthesizing these elements produces a composite risk metric that captures both physical hazards and their impact on facility performance. This unit-level analysis enables operators to prioritize risks and establish effective response strategies before flooding occurs.

2. Methodologies

2.1. Study Site and Flood Scenarios

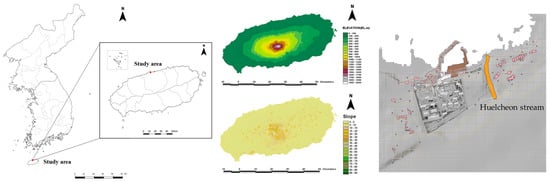

The proposed framework was applied to the Dodu sewage treatment facility (STF) in Jeju, South Korea. As shown in Figure 1, the facility is situated in a low-lying area (EL. 10–13 m) adjacent to Huelcheon Stream. which is highlighted in orange. The site layout in the figure also identifies surrounding buildings in pink and port facilities in brown. Although the facility is partially protected by natural topography, consultations with facility managers revealed a critical vulnerability: if the Huelcheon Stream located to the east overflows, the flood elevation aligns with the facility’s ground level, potentially bypassing the topographic defense. This site-specific insight, derived from local operational experience, served as the rationale for the external flooding boundary conditions used in this study.

Figure 1.

Description of study area.

To evaluate the facility’s resilience under critical failure modes, two distinct flood scenarios were established: (1) External Fluvial Flooding and (2) Internal Inundation driven by Compound Hazards. The specifications and rationale for each scenario are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of flood scenarios and hydraulic boundary conditions applied in the study.

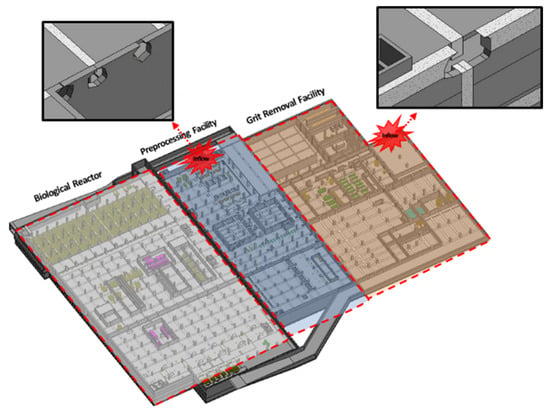

While Scenario 1 addresses standard flood risks, Scenario 2 was specifically designed to address the vulnerability of underground infrastructure to compound disasters. In South Korea, the increasing frequency of seismic activities has raised concerns about the structural safety of critical infrastructure. If an earthquake were to compromise the exterior walls of an underground STF during or prior to a flood event, the resulting high-velocity inflow through cracks could bypass standard flood defenses. Therefore, although a detailed structural dynamics analysis is outside the scope of this hydraulic study, we adopted a conservative ‘consequence-based’ approach. The inflow locations were determined based on structural vulnerability assessments, which identified the specific wall sections most susceptible to cracking under seismic loading [23]. By imposing hypothetical breaches at these scientifically determined weak points, as shown in Figure 2, we simulated a worst-case internal inundation scenario where the facility’s physical defense is compromised during a flood event.

Figure 2.

Inflow points for simulating inundation within the study area.

This allows for an independent assessment of how the facility’s complex internal layout influences flood propagation and equipment submersion risks, providing vital data for establishing emergency response protocols under catastrophic failure conditions.

2.2. Two-Dimensional Hydrodynamic Model

To simulate the complex flood propagation across the STF, the HDM-2D model was utilized. This model computes flow dynamics by solving the depth-averaged Shallow Water Equations (SWEs) using the Finite Element Method (FEM) [24]. A critical challenge in this study was accurately capturing the rapid, discontinuous flows characteristic of the flash flood scenario. To address this, the model incorporates the Streamline-Upwind/Petrov-Galerkin (SU/PG) stabilization scheme. This numerical technique effectively suppresses non-physical oscillations, ensuring stable and accurate solutions even in the presence of high-velocity shockwaves and abrupt wet/dry transitions around internal structures. Utilizing a finite element scheme, the model computes flow velocities and water depths while accurately capturing critical phenomena, including wave reflection, wet/dry transitions, and flow separation around internal obstacles.

The topographic input integrated a high-precision Digital Elevation Model (DEM) with structural elevations derived from engineering drawings, ensuring realistic simulation of floodwater ingress and diversion by on-site barriers. For the topographic data, we utilized a DEM with a spatial resolution of 5 m × 5 m, provided by the National Geographic Information Institute (NGII) of Korea. To ensure the high precision required for modeling flow within the facility, the coarse DEM data was rigorously cross-verified and refined using detailed architectural as-built drawings of the STF.

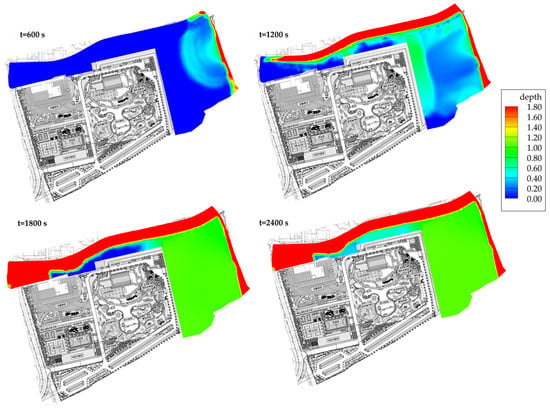

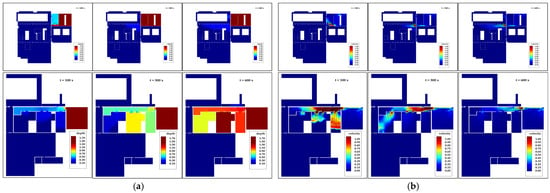

Simulation results for Scenario 1 reveal the spatiotemporal evolution of inundation driven by Huelcheon Stream overflow. As illustrated in Figure 3, floodwater initially breaches the boundary at t = 600 s, propagating towards the headworks and subsequently inundating the central facility area. The model captures the progressive accumulation of water, with the inundation extent expanding significantly between t = 1200 s and t = 2400 s. By the peak stage, the simulation indicates widespread submergence, with maximum inundation depths reaching approximately 1.80 m in low-lying zones along the northern perimeter. The color gradient (blue to red) highlights the severity of flooding, confirming that the terrain slope facilitates the rapid transport of flood volumes towards critical process units.

Figure 3.

External fluvial flooding analysis results for the study area (depth).

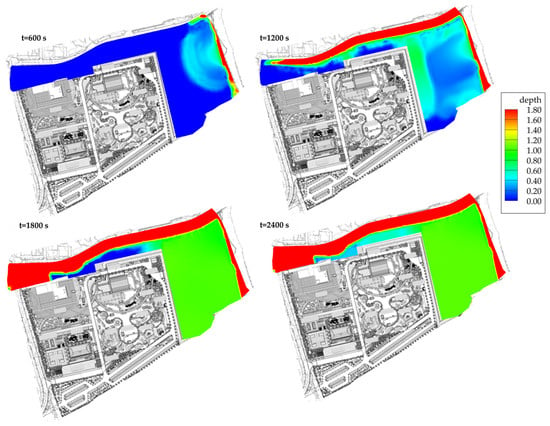

Simulation results for Scenario 2 demonstrate a markedly different hydraulic behavior characterized by rapid, localized intensification. Figure 4 presents the distribution of inundation depth and flow velocity at the peak of the flash flood event (t = 600 s). Unlike the gradual rise observed in the fluvial scenario, the structural breach leads to immediate, high-velocity intrusion. The hydrodynamic analysis shows that flow velocities exceed 1.90 m/s near the breach points (e.g., Grit Removal Facility), creating hazardous conditions capable of causing structural scouring and equipment dislodgement. Spatially, the inundation is concentrated along the facility’s perimeter and basement levels of the biological reactor, where depths quickly escalate to 1.70 m. These results underscore that internal failures can generate dangerous hydraulic loads in confined spaces, even if the total flood duration is shorter compared to riverine flooding. The hydraulic outputs—specifically the spatial distribution of maximum water depth () and peak flow velocity ()—serve as the foundational hazard metrics for the subsequent risk assessment. These quantitative indicators allow for the identification of “hotspots” where hydraulic intensity exceeds the design thresholds of critical equipment.

Figure 4.

Inundation analysis results for the bioreactor and pretreatment facility: (a) depth; (b) flow velocity.

2.3. Vulnerability Analysis of Unit Processes Based on Modified HAZOP and AHP

To translate the hydraulic hazard metrics derived from the 2D modeling into operational risk indicators, this study employs a hybrid framework integrating a Modified Hazard and Operability (HAZOP) study with the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). This dual approach allows for a comprehensive evaluation that considers both the physical failure probability of equipment and its functional criticality to the overall treatment process.

2.3.1. Modified HAZOP Study for Flood Risk Assessment

While the traditional HAZOP method is extensively used in the process industry to identify internal operational deviations (e.g., pressure or temperature fluctuations), it often lacks the spatial dimension required for natural disaster assessment. To overcome this, we adopted the Modified HAZOP study proposed by Nakhaei et al. [25], which tailors the conventional principles to explicitly address flood-induced hazards. Unlike standard safety reviews, this modified approach incorporates hydrologic and hydraulic data to evaluate how external inundation triggers internal process failures.

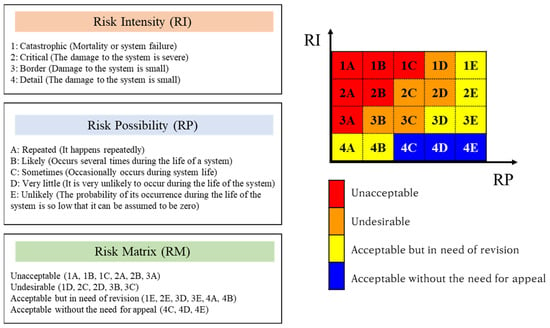

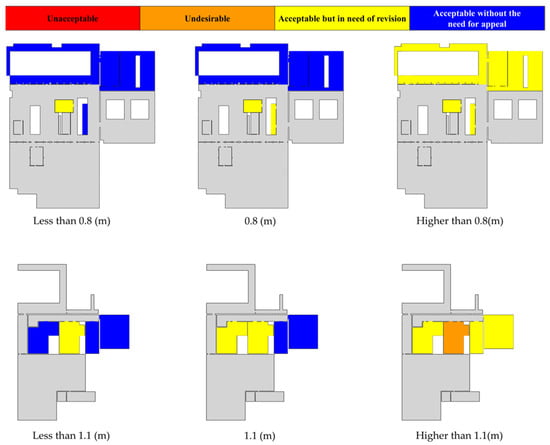

The procedure applied in this study is systematically visualized in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The workflow begins with the (1) Identification of Risk Items, where specific unit processes exposed to flooding are selected based on the 2D simulation results. Subsequently, (2) Expert Scoring is conducted to estimate two fundamental parameters: Risk Intensity (RI), representing the severity of consequences (e.g., from minor damage to catastrophic system failure), and Risk Possibility (RP), representing the likelihood of occurrence under the simulated flood scenarios. These parameters are then mapped onto a (3) Risk Matrix (RM), which categorizes the risk level of each unit into four distinct zones: Unacceptable, Undesirable, Acceptable with revision, and Acceptable. This structured process ensures that qualitative expert judgments are converted into semi-quantitative risk indices compatible with spatial flood maps.

Figure 5.

Modified HAZOP study for flood risk assessment process.

Figure 6.

Structure of the risk matrix integrating risk intensity and risk possibility for the modified HAZOP study.

2.3.2. Reliability of Expert Elicitation and Data Collection

The validity of both the modified HAZOP study and AHP relies heavily on the expertise of the participants. To ensure high reliability and operational relevance, the assessment was carried out by a panel of 20 veteran practitioners with extensive field experience in Combined STFs. The panel composition was carefully stratified to represent both private operational expertise and public management perspectives:

- Private Sector Experts (n = 15): Operators and engineers currently managing combined sewer treatment plants, with professional experience ranging from 7 to 20 years.

- Public Sector Experts (n = 5): Facility managers and supervisors from public environmental corporations, with experience ranging from 8 to 17 years.

The survey was conducted using a structured questionnaire where participants were presented with the specific inundation depth and velocity maps generated in Section 2.2. The questionnaire was divided into two main parts: pairwise comparisons for AHP weights and scenario-based risk scoring for the Modified HAZOP. To ensure informed decision-making, all participants were provided with a “Reference Packet” containing the HDM-2D flood maps and vertical cross-sections of critical equipment. The specific structure and examples of the questions are summarized in Table 2. Participants evaluated the relative importance and vulnerability of each unit process based on criteria such as functional significance, locational vulnerability, downtime impact, and recovery feasibility. To verify the consistency of the expert judgments, the Consistency Ratio (CR) was calculated for all AHP pairwise comparisons, and responses with a CR > 0.1 were reevaluated to maintain statistical validity.

Table 2.

Structure and representative questions of the expert survey.

2.3.3. Integration of Operational Criticality (AHP)

While the Modified HAZOP study identifies the likelihood of failure, it does not inherently account for the importance of the failed unit to the entire process function. Therefore, AHP weights were integrated to quantify the operational criticality. For instance, while a storage warehouse and a main electrical room might face similar flood depths (Hazard), the electrical room is assigned a significantly higher weight due to its potential to cause a total facility blackout. The index is thus derived by coupling the modified HAZOP-based risk levels with AHP-derived importance weights.

2.4. Integrated Hydro-Operational Risk Assessment (IHORA) Framework

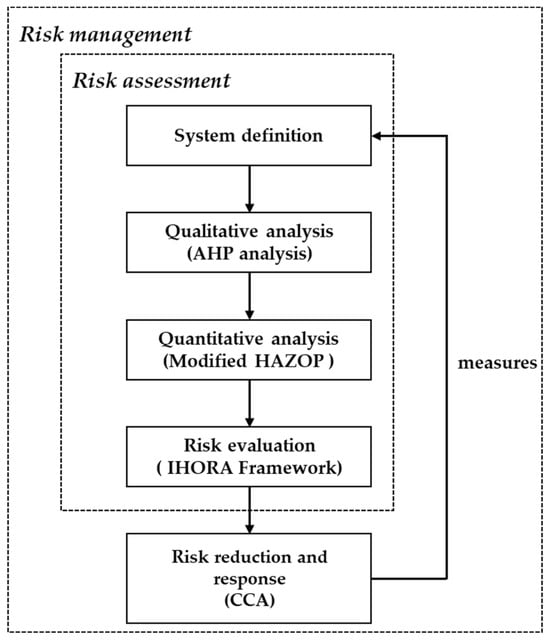

To overcome the limitations of conventional flood hazard mapping, which often treats industrial facilities as homogeneous entities, this study establishes the Integrated Hydro-Operational Risk Assessment (IHORA) framework. As conceptualized in Figure 7, the IHORA framework synthesizes physical hazard data with operational vulnerability parameters into a coherent workflow. This process begins with defining risk indicators (Table 3) and culminates in a unified risk metric that guides emergency response.

Figure 7.

Diagram linking risk assessment with management strategies.

Table 3.

Indicators for the IHORA framework.

2.4.1. Quantitative Formulation and Physical Meaning of IHORA

The core of the IHORA framework lies in quantifying flood risk not merely as a probability of inundation, but as the potential for operational disruption. In this study, the proposed concept of vulnerability serves as a criterion for determining whether individual treatment processes and facilities at a sewage treatment facility can remain operational under inundation. Understanding the characteristics of each unit process allows for the delineation of the domain in which flood impacts are assessed. Accordingly, the flood risk assessment for a sewage treatment facility was defined as Equation (1),

However, the absolute levels of flood depth and velocity that cause damage are not known a priori. To quantify the hydraulic impact more rigorously, we adopted the Flood Intensity Index (FI) proposed by Beffa and used it as the primary metric for flood risk [26,27]. The IHORA framework formulates the IHORA Index for each unit process i as follows:

where = composite flood risk index of the i-th unit process

- = Flood Intensity Index of the i-th unit process

- = maximum FI among all unit processes

- = Operational criticality weight of the i-th unit process, derived by the AHP

- S = Standard scaling factor

In this equation, the first term, represents the Normalized Physical Hazard, serving as a dimensionless ratio of physical stress. Here, corresponds to Beffa’s Flood Intensity index calculated from the depth and velocity outputs of the 2D hydrodynamic simulation, while is the maximum intensity observed across the entire facility domain. This normalization process quantifies the relative hydraulic severity exerted on a specific unit compared to the worst-case scenario within the site. The second term, , denotes the Operational Criticality Weight, which reflects the relative functional importance of the -th unit process. Unlike the physical hazard, which depends on external floodwaters, , is an intrinsic property of the facility derived from the AHP analysis. Crucially, this weight acts as a differentiator for vulnerability. It indicates how critical a specific unit is to maintain the facility’s biological and chemical continuity, thereby distinguishing essential processes from auxiliary areas even under identical flood conditions. Finally, the term S represents the standard scaling factor, set to 10 in this study. This scaling approach is consistent with established methodologies in composite index construction, such as the water quality index (WQI) [28], where raw weighted sums are scaled to user-friendly ranges (e.g., 0–100). Given that AHP weights for multiple unit processes (in this study, n = 13) are inherently small due to the sum-to-one constraint (Weight Dilution), S amplifies the final score into a perceptible range (0–10) without altering the relative risk ranking. This ensures that the IHORA index functions effectively as an operational warning signal. Mathematically, since S is applied uniformly across all variables, variations in its value affect only the magnitude of the index, not the relative risk ranking of the unit processes. Thus, the prioritization of high-risk assets remains stable and robust regardless of the scaling factor chosen. The resulting IHORA index represents the “Operational Paralysis Intensity”. A high IHORA score indicates that a unit is not only exposed to severe hydraulic forces but is also a functional bottleneck in the treatment process. Conversely, a low score implies that the unit is either hydraulically safe, or its failure has a minimal impact on the overall facility effluent quality.

2.4.2. Risk Level Categorization and Response Protocols

To translate the quantitative IHORA index into actionable protocols, we established a four-level Emergency Alert System (Table 4). This classification aligns with the National Disaster Management System of South Korea, which standardizes crisis alerts into four stages: Attention, Caution, Alert, and Severe. This alignment ensures that the proposed framework can be seamlessly integrated into existing municipal safety protocols. The threshold values (0.2, 0.5, 0.8) were strategically calibrated to ensure the IHORA index effectively translates quantitative risk into actionable response protocols aligned with the facility’s functional tolerance. Specifically, these thresholds, validated by expert elicitation, demarcate critical transitions in operational status: 0.2 signifies the transition to a Preventive Phase (onset of physical threat to sensitive, low voltage equipment), 0.5 marks the point of critical loss of redundancy (severe hindrance to unit efficiency and process continuity), and 0.8 denotes the threshold for imminent system paralysis (high probability of catastrophic failure requiring total shutdown and evacuation).

Table 4.

Flood risk levels and corresponding response measures based on the IHORA index.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Vulnerability Analysis

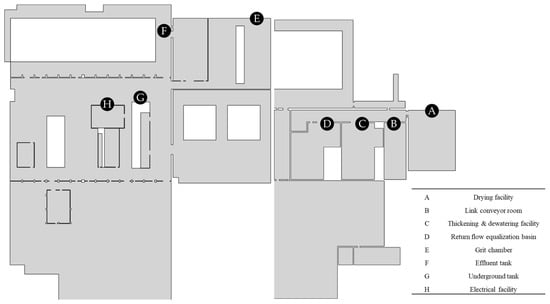

The spatial vulnerability assessment commenced with the identification of critical flood ingress locations based on the hydrodynamic simulation results. As delineated in Figure 8, eight specific compartment inflow points (designated A–H) were established, representing the primary pathways through which floodwaters propagate into key unit processes. These points were selected by overlaying the maximum inundation extent from the 2D model onto the facility’s architectural layout, ensuring that the risk assessment specifically targets operational nodes rather than generalized open spaces.

Figure 8.

Compartment specific inflow points based on the inundation analysis results for the study area.

To quantify the operational vulnerability at these identified inflow nodes, a modified HAZOP survey was conducted involving 20 industry practitioners. Table 5 summarizes the aggregated expert evaluations for Risk Intensity (RI) and Risk Possibility (RP). Crucially, the depth standards (e.g., 0.8 m and 1.1 m) presented in Table 4 were not arbitrarily selected; they were rigorously established based on a detailed analysis of the facility’s cross-sectional design drawings and equipment mounting elevations. The 0.8 m threshold was applied to highly sensitive units (e.g., Electrical Facility, Points E–H) as it corresponds to the typical installation height of low-voltage control panels and instrumentation sensors, where even minimal water contact induces immediate electrical short circuits. The 1.1 m threshold was utilized for mechanically intensive zones (e.g., Drying Facility, Points A–D), representing the critical elevation of motor housings and air intakes for heavy machinery, beyond which structural inundation leads to irreversible mechanical failure. By anchoring the HAZOP parameters to these physical tipping points, the reliability of the qualitative expert judgments was significantly enhanced. This consistency was statistically corroborated by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.74 to 0.93 [29,30], confirming a high degree of consensus among the panel regarding the functional criticality of each unit under specific hydraulic loads.

Table 5.

Modified HAZOP study results and reliability analysis.

The integration of these expert-derived risk matrices with the hydraulic depth variations yielded the spatial risk distribution illustrated in Figure 9. A critical observation from this mapping is the non-linear threshold sensitivity of operational safety. Unlike linear damage functions often used in economic loss estimation, the results demonstrate that risk levels for specific units transition abruptly from “Acceptable” to “Unacceptable” as water depths cross distinct critical thresholds. This trend is most vividly observed in the Underground Tank (Point G) and Electrical Facility (Point H). As shown in Figure 9, the Electrical Facility enters the “Unacceptable” (Red) risk zone at significantly shallower depths compared to robust civil structures like the Grit Chamber (Point E). This disparity highlights that vulnerability is highly localized and intrinsic to the asset type; for units housing sensitive electronic components, the “tipping point” for operational failure is significantly lower. Consequently, Figure 9 empirically validates the necessity of the proposed framework, proving that a uniform flood protection standard is insufficient. This disparity highlights that vulnerability is intrinsic to the asset type, validating the framework’s capability to differentiate risk based on the specific “failure elevation” of each process unit.

Figure 9.

Risk estimation of inundation areas of interest by flood depth.

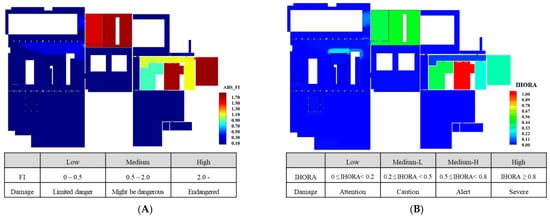

3.2. Quantitative Assessment of Hydro-Operational Risk

The Integrated Hydro-Operational Risk Assessment (IHORA) framework was applied to the study site to quantitatively evaluate the flood risk for each facility component. Table 6 summarizes the computed IHORA indices, which integrate the normalized Flood Intensity (FI) derived from the hydrodynamic model with the Operational Criticality Weights () obtained from the AHP analysis. To ensure a granular assessment of the facility’s vulnerabilities, the assets were classified into three distinct functional levels: (1) Units, representing discrete equipment critical for specific functions such as the Electrical Facility and Groundwater Collection Tank; (2) Processes, indicating continuous core treatment stages essential for meeting effluent standards, including the Grit Chamber and Digester; and (3) Auxiliary Processes, which denote supporting infrastructure like the Link Conveyor Room and Drying Facility that facilitate operations but are not part of the primary liquid treatment line.

Table 6.

Results of the IHORA.

The assessment results indicate significant disparities in risk levels across different assets. The Sludge Thickening & Dewatering Room exhibited the highest risk score (IHORA = 1.00) among all evaluated components. This peak risk is driven by the convergence of high physical exposure (FI = 1.75), resulting from its low-lying location, and its significant operational weight (W = 0.106), which reflects the difficulty of sludge recovery processes. A particularly notable finding is the evaluation of the Electrical Facility. Despite having a relatively low physical exposure (FI = 0.26) due to its specific location, it recorded a substantial IHORA score (IHORA = 0.22). This elevation in risk ranking is primarily attributed to its paramount operational weight (W = 0.150), identifying it as the “nervous system” of the facility where even minor inundation can trigger a total system blackout. In contrast, the Mixed Sludge Storage Tank, located in a non-inundated zone, maintained a zero risk score (IHORA = 0.00) regardless of its process importance, confirming the framework’s capability to correctly filter out non-exposed assets.

3.3. Comparative Evaluation

The distinct advantage of the proposed IHORA framework is vividly demonstrated through a comparative evaluation with the conventional Flood Intensity (FI) map, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Comparison of flood risk assessment results by index: (A) FI index; (B) IHORA index.

The FI Index map (a), based solely on hydraulic parameters of depth and velocity, identifies the grit chamber and drying facility as the highest hazard zones. This conventional approach essentially treats the facility as a passive topography, highlighting areas simply because they experience deep inundation. However, the IHORA Index map (b) redistributes these “hotspots” based on operational reality, revealing a critical “Risk Misalignment” inherent in traditional assessments. Two key discrepancies were identified. First, the Auxiliary Processes, such as connecting corridors and open spaces, showed high FI values but dropped significantly in the IHORA map. Allocating limited mitigation resources to these areas based on FI alone would represent an inefficient investment. Second, and more crucially, the Electrical Facility and Grit Chamber appeared as low to moderate hazard zones in the FI map but were reclassified as high-priority risk areas in the IHORA assessment. The quantitative comparison reveals significant ‘Rank Shifts’ that highlight the limitations of traditional assessments. For instance, the Drying Facility exhibited the highest physical exposure (FI = 1.77), ranking 1st in the conventional hazard map. However, due to its low operational weight ( = 0.034), its priority dropped to Rank 4 in the IHORA assessment. Conversely, the Electrical Facility, despite a low physical exposure (FI = 0.26), saw its risk index rise to 0.22, crossing the ‘Caution’ threshold defined in the safety protocols. This shift from a negligible hydraulic risk to a prioritized operational threat demonstrates the IHORA framework’s capability to correct risk misalignment and focus resources on assets that safeguard facility continuity.

This correction occurs because the IHORA index accounts for the catastrophic consequences of failure in these units. Consequently, while the FI index merely answers, “Where is the water deep?”, the IHORA index provides the more decision-relevant answer: “Where will the flooding most severely disrupt operations?”. This shift in perspective is vital for decision makers, ensuring that mitigation efforts are strategically directed toward assets that safeguard the facility’s continuity.

3.4. Establishment of Response Scenarios and Safety Systems

3.4.1. Application of Cause-Consequence Analysis (CCA) for Failure Mode Tracing

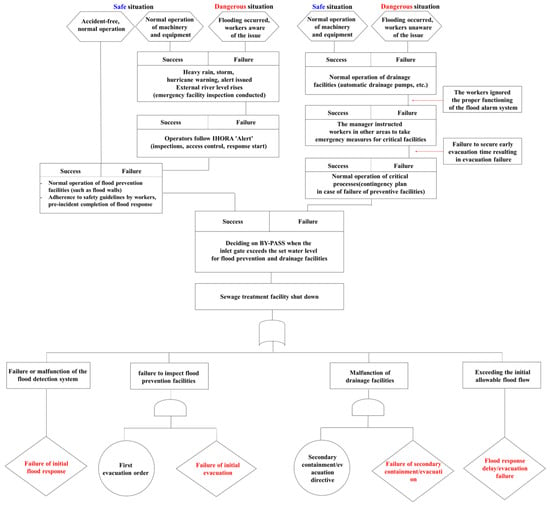

In this study, the Cause-Consequence Analysis (CCA) technique was introduced to bridge the gap between the static flood risk derived from the IHORA framework and dynamic operational response scenarios. CCA integrates Fault Tree Analysis (FTA) and Event Tree Analysis (ETA) to logically trace the final outcome (e.g., facility shutdown) from an initial disaster trigger, depending on the success or failure of various Safety Barriers. This approach is effective in elucidating the complex interdependencies among processes and identifying cascading failure mechanisms, which conventional hydraulic analyses often overlook. Recent studies have demonstrated its utility in evaluating complex disaster risks in STFs and ensuring operational sustainability [31]. Furthermore, its validity has been proven as a tool for identifying dynamic failure modes and quantitatively assessing system reliability under uncertain conditions, such as extreme rainfall or equipment malfunction [32]. In this research, CCA was utilized to identify “latent risks” beyond simple inundation depth and to visualize how the failure of a specific unit (e.g., drainage pump) propagates into a total paralysis of the treatment process.

3.4.2. Development and Tracking of Flood Disaster Scenarios

To bridge the gap between static risk quantification and dynamic operational reality, this study utilized Cause-Consequence Analysis (CCA) to trace the progression of flood disasters based on the vulnerability profiles established by the IHORA framework. While the IHORA index effectively identifies which assets, such as the Electrical Facility, possess the highest criticality (W = 0.150, IHORA = 0.22), the CCA complements this by visualizing how specific failures in safety barriers can lead to a catastrophic system shutdown. As illustrated in Figure 11, the analysis delineates two distinct operational trajectories starting from an initiating event: a resilient response path and a catastrophic escalation path. In the resilient response path, the system effectively neutralizes threats through a sequence of successful defensive actions. Upon the detection of an initiating event, such as rising external river levels or storm warnings, the facility activates ‘Alert’ phase protocols corresponding to the IHORA risk levels. Crucially, this path relies on the timely execution of safety barriers, including the deployment of flood stop logs and the activation of emergency generators. The successful functioning of these measures, particularly for high-risk assets identified by the IHORA assessment, ensures that the facility intercepts the flood threat and maintains operational continuity without service interruption.

Figure 11.

Development of flood disaster scenarios for sewage treatment facilities using CCA.

Conversely, the catastrophic escalation path reveals the cascading consequences of safety barrier failures. The CCA diagram explicitly highlights that disaster propagation is not solely driven by mechanical malfunctions, such as the failure of drainage pumps, but is significantly exacerbated by human error. Specific failure nodes, such as workers ignoring flood alarms or failing to secure early evacuation time, serve as critical tipping points that allow a manageable incident to escalate into a full-scale disaster. For instance, under the compound hazard conditions of Scenario 2, a structural breach combined with a failure in initial detection allows high velocity inflows to rapidly inundate critical subsurface units. The analysis demonstrates that when these high-risk assets identified by IHORA, specifically the “nervous system” of the facility like the electrical room—are compromised due to such coupled failures, it precipitates a total paralysis of the treatment process. The analysis further identifies the decision to execute a “BY-PASS” as the ultimate safeguard for facility survival. When the inlet gate water level exceeds critical thresholds, the failure to implement this strategic bypass serves as the final breach in the defense layers, leading directly to the “Top Event” of a sewage treatment facility shutdown. Consequently, the CCA scenario tracking empirically validates the IHORA framework’s prioritization, confirming that the resilience of the facility depends on a dual strategy: reinforcing the physical hardening of high-risk assets while simultaneously establishing robust decision support protocols to mitigate human error during the critical response window.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study addressed a critical gap in current flood risk management practices by establishing and validating the Integrated Hydro-Operational Risk Assessment (IHORA) framework. While traditional methodologies have predominantly focused on regional-scale hydraulic hazard mapping, they often fail to capture the functional intricacies of industrial facilities. To overcome this limitation, this research proposed a novel approach that synthesizes 2D hydrodynamic modeling (HDM-2D) with operational criticality derived from a Modified HAZOP study and AHP. By applying this framework to a representative underground sewage treatment facility under both external fluvial flooding and internal structural breach scenarios, this study derived several key scientific findings and practical recommendations.

4.1. Scientific Findings and Contributions

First, the quantitative assessment demonstrated that flood risk in industrial facilities is fundamentally a function of process interdependency, not merely physical exposure. The application of the IHORA index revealed a critical “Risk Misalignment” inherent in conventional assessments. While the traditional Flood Intensity (FI) map identified auxiliary corridors and open spaces as high-hazard zones based solely on inundation depth, the IHORA framework successfully reallocated risk priorities to operationally critical assets. Specifically, the Electrical Facility and Sludge Thickening Room were identified as the highest risk units. Despite experiencing relatively moderate hydraulic stress, their high operational weights reflecting their role as the facility’s “nervous system” drove their risk scores to the upper quartiles. This finding empirically proves that neglecting operational weights leads to a significant underestimation of risk for critical infrastructure.

Second, the spatial vulnerability analysis highlighted the non-linear threshold sensitivity of facility assets. The integration of the Modified HAZOP study allowed for the visualization of how safety levels deteriorate abruptly once water depths cross specific critical thresholds (e.g., 0.8 m for electrical panels). This granular mapping provides a more accurate diagnostic tool than uniform flood maps, enabling managers to pinpoint exactly where “tipping points” for system failure exist within the facility layout.

Third, the Cause-Consequence Analysis (CCA) provided a dynamic perspective on these static risk indices, uncovering latent failure mechanisms. The scenario tracking revealed that standard response protocols, while effective against gradual riverine flooding (Path A), are insufficient for compound hazards such as seismic-induced structural breaches (Path B). The analysis showed that the failure of internal sensors to detect rapid, localized inflows could lead to a cascading failure sequence starting from a structural crack, propagating to the electrical room, and culminating in a total biological process shutdown. This validates the necessity of extending vulnerability analysis beyond physical damage to include the reliability of safety barriers.

4.2. Practical Recommendations for Resilience

Based on the empirical findings of this study, we advocate for a paradigm shift in flood mitigation strategies for environmental facilities, moving beyond traditional “Flood Defense” toward a more holistic “Operational Resilience.” To achieve this, a strategic reallocation of mitigation resources is paramount. Investments should be prioritized based on the IHORA index rather than the conventional FI index. Engineering reinforcements, such as watertight compartmentalization and the elevated mounting of sensitive equipment, must be concentrated on high IHORA assets—specifically, the Electrical Facility and Grit Chamber rather than on auxiliary zones that may exhibit high physical exposure but low operational criticality. This targeted hardening ensures that limited resources are effectively utilized to safeguard the facility’s most vital functional nodes.

Furthermore, to address the detection blind spots identified by the Cause-Consequence Analysis (CCA), particularly regarding compound hazards, the implementation of redundant monitoring systems is essential. Independent internal inundation sensors should be installed in critical subsurface units to detect localized breaches that external warning systems fail to capture. These sensors must be linked to an automated control logic capable of triggering isolation protocols, such as closing watertight doors, even when external river levels appear normal, thereby preventing the escalation of internal structural failures. Finally, physical hardening must be complemented by the refinement of emergency protocols. The Activity Diagrams developed in this study should be adopted to standardize human responses and reduce procedural ambiguity. Specifically, emergency manuals must be updated to include distinct response tracks for “Structural Integrity Failure” events. This ensures that operators possess clear decision nodes and actionable procedures for scenarios where external warnings are silent but internal operational integrity is compromised, ultimately closing the loop between risk identification and effective crisis management.

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

Notwithstanding the robust architecture of the IHORA framework, it is acknowledged that the operational criticality weights were determined via expert elicitation. This reliance on semi-quantitative judgments introduces a degree of epistemic uncertainty, representing a static snapshot of process importance rather than a dynamic variable. However, this methodological approach was deliberately adopted to establish a fundamental baseline for differentiating the functional hierarchy of unit processes, a dimension frequently overlooked in conventional hydraulic assessments.

A critical avenue for future research involves demonstrating the comparative efficacy of this process-centric risk assessment over traditional hazard-centric methodologies. Unlike conventional studies that are confined to external inundation mapping, the IHORA framework explicitly quantifies the operational dimension, specifically, the non-linear functional interdependencies of treatment units. Subsequent studies should focus on assessing the transferability and robustness of the proposed index across heterogeneous environmental facilities with varying treatment capacities and hydraulic boundary conditions. Comparative benchmarks across multiple sites would serve to validate the versatility of the IHORA index, confirming that the integration of operational criticality significantly refines risk diagnosis and resource prioritization regardless of site-specific configurations.

Furthermore, future investigations should aim to enhance the temporal resolution of the framework by coupling it with real-time hydro-informatics systems, such as SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) based digital twins. By evolving the current static model into a dynamic decision-support tool capable of real-time data assimilation, future research can enhance its utility in adaptive flood management. Such advancements would empirically prove that a process-based approach not only identifies vulnerability hotspots with greater precision but also substantially augments the operational resilience and continuity of critical infrastructure under extreme hydrological loading.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G.S.; Methodology, T.E. and E.S.; Analysis, T.E. and E.S.; Writing—original draft preparation, T.E.; Writing—review & editing, D.S.R.; Funding acquisition, C.G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through Research and Development on the Technology for Securing the Water Resources Stability in Response to Future Change (RS-2024-00335281) Program, funded by Korea Ministry of Climate, Energy, Environment (MCEE).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tabari, H. Climate change impact on flood and extreme precipitation increases with water availability. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Su, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, G.; Huang, J.; Jiang, T. Flood risk in a range of spatial perspectives–from global to local scales. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 19, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, M.A.; Berry, M.S.; Stacey, M.T. Sea level rise impacts on wastewater treatment systems along the US coasts. Earth’s Future 2018, 6, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersonius, B.; Ashley, R.; Pathirana, A.; Zevenbergen, C. Climate change uncertainty: Building flexibility into water and flood risk infrastructure. Clim. Change 2013, 116, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liziński, T.; Wróblewska, A.; Rauba, K. Application of CVM method in the evaluation of flood control and water and sewage management projects. J. Water Land Dev. 2015, 26, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olds, H.T.; Corsi, S.R.; Dila, D.K.; Halmo, K.M.; Bootsma, M.J.; McLellan, S.L. High levels of sewage contamination released from urban areas after storm events: A quantitative survey with sewage specific bacterial indicators. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, J.; Jakeman, A.J.; Vaze, J.; Croke, B.F.; Dutta, D.; Kim, S.J. Flood inundation modelling: A review of methods, recent advances and uncertainty analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 90, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrighi, C.; Brugioni, M.; Castelli, F.; Franceschini, S.; Mazzanti, B. Flood risk assessment in art cities: The exemplary case of Florence (Italy). J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 11, S616–S631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojinovic, Z.; Tutulic, D. On the use of 1D and coupled 1D–2D modelling approaches for assessment of flood damage in urban areas. Urban Water J. 2009, 6, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandro, J.; Chen, A.S.; Djordjević, S.; Savić, D.A. Comparison of 1D/1D and 1D/2D coupled (sewer/surface) hydraulic models for urban flood simulation. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2009, 135, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankow, N.; Krause, S.; Schaum, C. Resilience Adaptation Through Risk Analysis for Wastewater Treatment Plant Operators in the Context of the European Union Resilience Directive. Water 2024, 16, 3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, C.; Beteringhe, A.; Răduc, M.A. Vulnerability of urban floods in association with the sewage system and geographical features in the Giulești–Sârbi neighborhood, Bucharest, Romania. Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 15, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, D.A. Damage to wastewater treatment facilities from great flood of 1993. J. Environ. Eng. 1997, 123, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brito, M.M.; Evers, M. Multi-criteria decision-making for flood risk management: A survey of the current state of the art. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 16, 1019–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, D.S.; Lutz, M.A. Urban flood hazard zoning in Tucumán Province, Argentina, using GIS and multicriteria decision analysis. Eng. Geol. 2010, 111, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.M.; Sun, W.J.; Shen, S.L.; Arulrajah, A. Flood risk assessment in metro systems of mega-cities using a GIS-based modeling approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 626, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, S.; Stathis, D. Assessment of flood hazard based on natural and anthropogenic factors using analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Nat. Hazards 2013, 68, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2008, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, Y.O.; Tateishi, R. Urban flood vulnerability and risk mapping using integrated multi-parametric AHP and GIS: Methodological overview and case study assessment. Water 2014, 6, 1515–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danumah, J.H.; Odai, S.N.; Saley, B.M.; Szarzynski, J.; Thiel, M.; Kwaku, A.; Kouame, F.K.; Akpa, L.Y. Flood risk assessment and mapping in Abidjan district using multi-criteria analysis (AHP) model and geoinformation techniques,(cote d’ivoire). Geoenviron. Disasters 2016, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, G.; Vasiliades, L.; Loukas, A. Multi-criteria analysis framework for potential flood prone areas mapping. Water Resour. Manag. 2015, 29, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souissi, D.; Zouhri, L.; Hammami, S.; Msaddek, M.H.; Zghibi, A.; Dlala, M. GIS-based MCDM–AHP modeling for flood susceptibility mapping of arid areas, southeastern Tunisia. Geocarto Int. 2020, 35, 991–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Development and Demonstration of Simulation Technology for Predicting Damage to Environmental Facilities During Earthquakes and Flooding; R&D Report 1485019223; Ministry of Environment: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, I.W.; Song, C.G. Specification of wall boundary conditions and transverse velocity profile conditions in finite element modeling. J. Hydrodyn. 2010, 22, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhaei, M.; Nakhaei, P.; Gheibi, M.; Chahkandi, B.; Wacławek, S.; Behzadian, K.; Campos, L.C. Enhancing community resilience in arid regions: A smart framework for flash flood risk assessment. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 153, 110457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beffa, C. Two-dimensional modelling of flood hazards in urban areas. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Hydroscience and Engineering, Copenhagen, Denmark, 24–26 August 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, E.; Kim, H.J.; Rhee, D.S.; Eom, T.; Song, C.G. Spatiotemporal flood risk assessment of underground space considering flood intensity and escape route. Nat. Hazards 2021, 109, 1539–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutadian, A.D.; Muttil, N.; Yilmaz, A.G.; Perera, B.J.C. Development of river water quality indices—A review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, L.M. Cronbach’s alpha. Medsurg Nurs. 2011, 20, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tušer, I.; Oulehlová, A. Risk assessment and sustainability of wastewater treatment plant operation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analouei, R.; Taheriyoun, M.; Amin, M.T. Dynamic failure risk assessment of wastewater treatment and reclamation plant: An industrial case study. Safety 2022, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.