Abstract

This study presents a texture-aware image synthesis framework designed to generate material-consistent façades using adversarial learning. The proposed architecture incorporates a mask-guided channel-wise attention mechanism that adaptively merges segmentation information with texture statistics to reconcile structural guiding with textural fidelity. A thorough comparative analysis was performed utilizing three internal variants—Vanilla GAN, Wasserstein GAN (WGAN), and WGAN-GP—against leading baselines, including TextureGAN and Pix2Pix. The assessment utilized a comprehensive multi-metric framework that included SSIM, FID, KID, LPIPS, and DISTS, in conjunction with a VGG-19 based perceptual loss. Experimental results indicate a notable divergence between pixel-wise accuracy and perceptual realism; although established baselines attained elevated PSNR values, the suggested Vanilla GAN and WGAN models exhibited enhanced perceptual fidelity, achieving the lowest LPIPS and DISTS scores. The WGAN-GP model, although theoretically stable, produced smoother but less complex textures due to the regularization enforced by the gradient penalty term. Ablation investigations further validated that the attention mechanism consistently enhanced structural alignment and texture sharpness across all topologies. Thus, the study suggests that Vanilla GAN and WGAN architectures, enhanced by attention-based fusion, offer an optimal balance between realism and structural fidelity for high-frequency texture creation applications.

1. Introduction

Texture constitutes one of the most fundamental visual cues employed to perceive, describe, and analyze both natural and artificial materials. As a core attribute of visual information, it provides essential insight into the structural organization and surface properties of objects within an image. Although a universally accepted formal definition remains elusive, texture is generally characterized as the spatial distribution of intensity or color variations that exhibit repetitive or structured patterns [1]. Texture analysis and synthesis have long been pivotal research topics in computer vision, underpinning applications ranging from image editing and computer graphics to material recognition and surface inspection.

Early methodologies predominantly relied on handcrafted descriptors such as Gabor filters, Local Binary Patterns (LBP) [2,3], and statistical models [4], which effectively captured local regularities but lacked robustness to scale, illumination, and semantic variations. Traditional approaches to texture analysis were primarily statistical, spectral, or structural, employing descriptors such as the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix, wavelet transforms, and fractal-based models to quantify pixel-level intensity relationships. Although these methods characterized simple textures well, they were unable to represent complex semantics or long-range dependencies.

With the emergence of deep learning, the field underwent a profound transformation. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) enabled hierarchical feature extraction from large image datasets, while Vision Transformers (ViTs) further extended this capability by learning global dependencies through self-attention mechanisms [5]. Comparative studies have shown that ViTs often outperform both handcrafted descriptors and CNNs in capturing multiscale texture representations, especially under transfer-learning settings. Nevertheless, most deep models emphasize feature representation rather than controllable texture synthesis, leaving a methodological gap between analytical understanding and generative modeling.

The introduction of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) marked a turning point in texture synthesis, shifting from sampling-based to data-driven generation. Frameworks such as pix2pix [6] and CycleGAN [7] demonstrated adversarial learning for image-to-image translation, enabling texture and style transfer between visual domains. Despite producing realistic outcomes, these models suffered from limited spatial control and unstable training dynamics. Subsequent developments, including TextureGAN [8], improved realism through spatially aware generators and user-guided patch placement.

In parallel, diffusion models have emerged as a powerful alternative to adversarial frameworks, providing superior stability and controllability. Latent diffusion models refine generation in a latent space, balancing computational efficiency with high fidelity. Recent studies have shown that diffusion-based architectures can synthesize façade imagery aligned with perceptual and geographical descriptors, achieving both structural coherence and visual realism [9,10]. These advances highlight the potential of diffusion frameworks to unify realism, stability, and semantic consistency in texture-oriented generation tasks.

However, a central challenge persists in integrating semantic structure with texture generation. Segmentation-based frameworks generally employ texture features for classification or recognition yet rarely exploit them for generative purposes. Conversely, many generative systems overlook the structural and semantic boundaries established by segmentation masks. Recent efforts have sought to bridge this divide. For example, Guo et al. [11] proposed a dual-stream network that jointly performs structure-constrained texture generation and texture-guided structure reconstruction via bidirectional feature fusion. In the 3D domain, semi-supervised frameworks have explored mask-guided texture mapping to generate high-resolution editable textures across complex geometries [12], while data-driven approaches have demonstrated that texture clusters can be learned directly from natural scenes, allowing synthesis and editing without explicit supervision [13].

Recent façade-centric pipelines reinforce these ideas by coupling semantic layout graphs with explicit texture-image mapping, resulting in more consistent reconstruction of repetitive façade elements such as windows and balconies [14]. Complementary generative studies have demonstrated that perceptual alignment between prompts and synthesized façades can inform texture placement—facilitating coherent selection, positioning, and blending that respect both geographical and stylistic constraints [9].

Although remarkable progress has been achieved in both texture representation and synthesis, two key limitations persist in the existing literature. First, structural masks are often treated as secondary conditioning signals rather than as integral components of the generation process. Second, texture analysis and texture synthesis remain largely decoupled, preventing a unified framework capable of reasoning jointly about structure and appearance.

To address these limitations, this study introduces a mask-conditioned texture creation and fusion framework in which segmentation masks act as structural guides and texture descriptors capture localized appearance statistics. Through a dual-encoder fusion architecture, structural and textural cues are integrated directly within the generative process to achieve semantic coherence and spatial precision. The proposed approach is evaluated using the perceptual and reconstruction metrics such as Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) [15], Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) [16], Kernel Inception Distance (KID) [17], Deep Image Structure and Texture Similarity (DISTS) [18], Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) [19], and Peak Signal to Noise Ratio (PSNR) [20], confirming its ability to preserve structural integrity while maintaining high visual fidelity. By bridging segmentation-based analysis with synthesis-based generation, this research advances the development of programmable, texture-sensitive vision models applicable to both two-dimensional and three-dimensional domains.

The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- A new and well-structured dataset is introduced, comprising facade images, corresponding segmentation masks, and material texture exemplars. This dataset enables controlled and reproducible evaluation of texture generation under explicit structural constraints.

- A texture-aware, mask-conditioned facade synthesis framework is proposed, in which segmentation masks provide spatial and semantic guidance while texture descriptors encode localized appearance statistics for material-consistent texture placement.

- A dual-encoder fusion architecture is developed to jointly integrate structural and textural cues within the generative process. Channel-wise attention is systematically incorporated into multiple adversarial learning frameworks (GAN, WGAN, and WGAN-GP) to enhance feature discrimination and texture fidelity.

- The proposed framework is evaluated across diverse facade configurations and material categories, including brick, stone, rock, and marble, demonstrating its robustness to architectural and material variability.

- A comprehensive evaluation is conducted using multiple perceptual, reconstruction, and distribution-based metrics (e.g., PSNR, SSIM, FID, KID, LPIPS, and DISTS), supported by statistical significance analysis, to objectively validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

The overall pipeline of this study integrates dataset preparation, mask-conditioned dual-encoder fusion, and quantitative evaluation into a unified framework for texture-aware façade generation, bridging the gap between segmentation-based analysis and generative synthesis.

In the remainder of this paper, Section 2 explains the materials and methods. Details of the proposed method are given in Section 3. Experimental settings used for the study are explained in Section 4. The experiments carried out and the results obtained are described and discussed in Section 5 and Section 6, respectively. Finally, the conclusions and potential future research directions are mentioned in Section 7.

2. Materials and Methods

This section describes the methodological framework of the proposed approach. It is divided into two parts: materials and method design. Each part is explained in detail to give a clear picture of the workflow followed in this study.

2.1. Materials

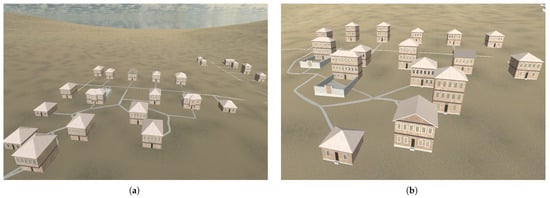

The dataset used in this study was created to capture a controlled yet varied set of material textures within architectural façades. For this purpose, a procedural city environment method [21] has been used. Figure 1 illustrates the city scenes. This setup made it possible to generate synthetic but visually realistic scenes with clearly defined material regions. The approach provided both flexibility and consistency across samples, which supported reliable learning and quantitative evaluation.

Figure 1.

Sample views from the procedurally generated cities. (a) The city view generated with population of 200, (b) The city view generated with population of 250.

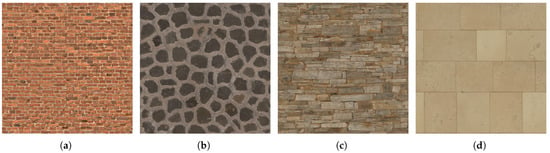

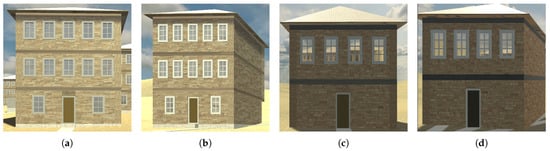

Within this synthetic city, multiple building structures were modeled and rendered using four primary types: brick, marble, stone, and rock. Several of the texture exemplars were sourced from the Poly Haven open-source texture repository [22], as shown in Figure 2. These materials were selected for their significant variability within classes and frequent appearance in real-world urban environments. Each facade was assigned a single dominant material type, while lighting direction, intensity, and camera viewpoints were systematically varied to introduce controlled diversity, as shown in Figure 3. Each façade is captured from a variety of angles, ranging from −30 to 30 degrees with respect to the direct front capture position. To increase dataset diversity, each material type is divided into two subtypes. For example, brick textures are divided into two subtypes: dense and non-dense. This strategy enhances the generalization capability of the network while avoiding domain overfitting.

Figure 2.

Samples of material textures used for training: (a) Brick, (b) Rock, (c) Stone, (d) Marble.

Figure 3.

Different camera viewpoints and lighting instances: (a,b) and (c,d) pairs are images of the same building from different angles.

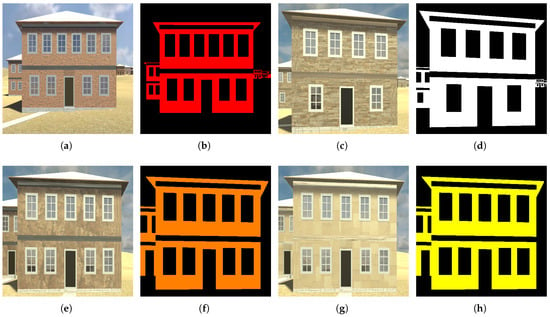

Alongside the RGB texture images, corresponding segmentation masks were generated concurrently using Unity’s material labeling and rendering layers. Since the positions of all buildings were known beforehand, the segmentation masks were generated programmatically within the Unity environment. Figure 4 illustrates that each material class is designated a distinct color: red for brick, yellow for marble, white for stone, and orange for rock. This established a one-to-one relationship between the texture and label regions.

Figure 4.

Examples of our dataset include textured and segmented building images; they should be listed as: (a) A brick-textured building. (b) Segmented image of (a). (c) A stone-textured building. (d) Segmented image of (c). (e) A rock-textured building. (f) Segmented image of (e). (g) A marble-textured building. (h) Segmented image of (g).

The final dataset comprises paired samples of texture and segmentation images, each with a spatial resolution of pixels. The entire dataset contains approximately 1000 façade instances, with an even distribution across the four material categories. Data augmentation techniques, including random rotations, horizontal flips, and brightness variations, have been widely adopted in the literature to enhance dataset diversity [23,24,25].

2.2. Methods

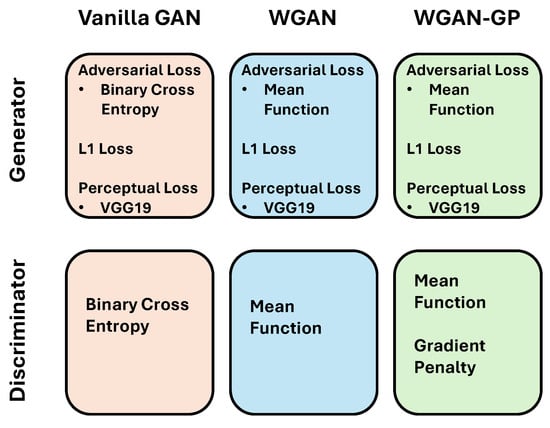

The proposed framework for texture-aware image synthesis is structured around three adversarial models: the baseline Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), the Wasserstein GAN (WGAN), and the Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP). Each variant contributes to the progression of stability, realism, and structural consistency in the generated textures. The following subsections describe these architectures and their mathematical foundations in detail.

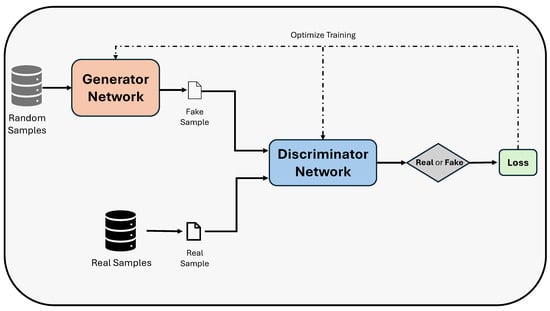

2.2.1. Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)

The baseline architecture, shown in Figure 5, is the vanilla Generative Adversarial Network [26], which consists of two competing neural networks—a generator (G) and a discriminator (D)—trained simultaneously. The generator learns to produce synthetic texture images conditioned on segmentation inputs, while the discriminator aims to differentiate real from fake samples. The training objective follows a minimax game:

This setup enables the model to capture complex texture distributions while preserving the spatial structure of the segmented regions.

Figure 5.

Basic Vanilla GAN Architecture.

2.2.2. Wasserstein GAN (WGAN)

To overcome the instability and mode collapse issues observed in the standard GAN, the Wasserstein GAN [27] was employed. WGAN optimizes the Earth Mover’s (Wasserstein-1) distance between real and generated data distributions instead of the Jensen–Shannon divergence, yielding a smoother optimization landscape. Its critic network estimates the Wasserstein distance, and weight clipping is applied to satisfy the Lipschitz constraint:

This approach substantially improves the training stability and produces more consistent texture outputs.

2.2.3. Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP)

To further enhance convergence and alleviate the limitations of weight clipping, the WGAN with Gradient Penalty [28] was adopted. This variant introduces a differentiable penalty term that enforces the Lipschitz constraint more effectively:

where represents samples interpolated between real and generated data, and is a regularization coefficient. This formulation enables stable and efficient convergence while maintaining high fidelity and structural realism in texture generation.

The training pipeline incorporated these three architectures under a unified implementation in PyTorch 2.7.1 (CUDA 12.6). For all models, Adam optimizer was used with a learning rate of 0.0002, , , and a batch size of 16. Loss functions included adversarial loss, pixel-wise L1 loss, and perceptual loss to balance realism and structural alignment.

3. Proposed Methodology

The proposed texture synthesis methodology seeks to produce high-fidelity material textures based on semantic segmentation inputs. The approach integrates several input modalities, such as segmentation masks and texture exemplars, via a dual-encoder fusion architecture, facilitating the model’s acquisition of both structural and material-specific representations. The architecture consists of two main modules: a multi-encoder generator and a patch-based discriminator, which are collaboratively optimized using a mix of adversarial and reconstruction losses.

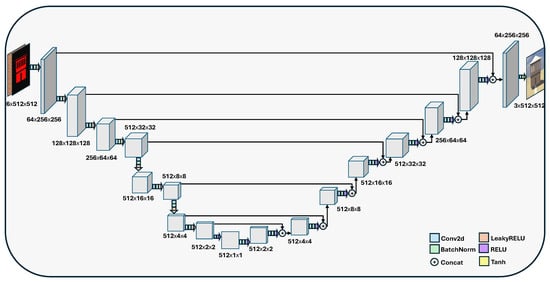

The generator shown in Figure 6 employs an encoder-fusion-decoder design. The encoder processes two different inputs simultaneously: the segmentation mask and the raw texture image, which are concatenated and fed into the encoder. The feature maps obtained from the encoder are concatenated and integrated at the bottleneck layer using channel-wise attention. To enhance the representational power of the bottleneck features, we employ a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) block [29] at the bottleneck. Unlike simple concatenation, this block models channel attachments to perform adaptive feature recalibration. Specifically, global spatial information is first aggregated into a descriptor z via global average pooling. The network then learns channel-specific weights s through a gating mechanism:

where is the ReLU function, is the sigmoid activation, and are the learned parameters of the fully connected layers. Finally, the original feature map is re-weighted by these scale factors via . This fusion process enables the network to accurately connect structural boundaries from the segmentation mask with detailed texture signals from the example.

Figure 6.

Architecture of proposed generator network.

The decoder reconstructs the final texture-aware image at the original resolution, maintaining material consistency and structural bounds. Skip connections are included between encoder and decoder layers to preserve spatial features. Batch normalization and LeakyReLU activations are utilized consistently across the network to enhance training stability.

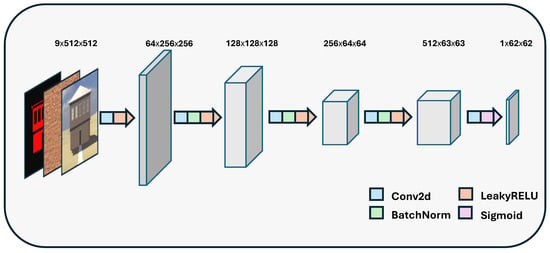

The discriminator employs a patch-based architecture akin to PatchGAN [6], assessing local texture genuineness across receptive fields. This architecture, illustrated in Figure 7, prompts the generator to yield locally coherent and realistic texture details throughout the surface areas delineated by the segmentation mask. The discriminator is trained to differentiate between authentic material textures and those generated by the generator, thus ensuring high-frequency fidelity.

Figure 7.

Architecture of proposed discriminator network.

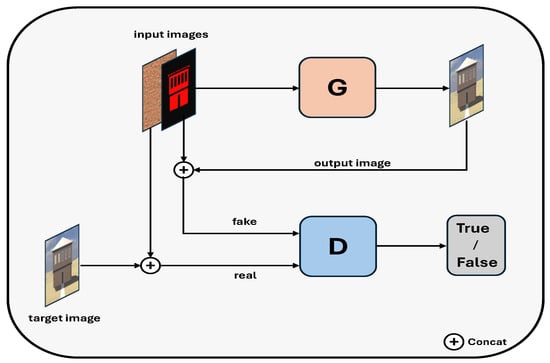

The overview of our framework is depicted in Figure 8. Both the generator and discriminator networks are denoted by the letters G and D, respectively. The generator produces an output image utilizing a segmented image and a texture image as inputs, without a specified target image. The output image and two input images are concatenated to serve as input for the discriminator network’s false image assessment. The true input consists of the target image, its segmented image, and the texture image concatenated for the discriminator network. The discriminator determines the authenticity of the images, classifying them as either genuine or counterfeit.

Figure 8.

Overview of Proposed Method: G represents the generator network, and D represents the discriminator network.

The optimization of the proposed framework relies on a set of adversarial and reconstruction-based losses, designed to ensure both visual realism and structural accuracy. Although all three models—vanilla GAN, Wasserstein GAN, and WGAN with Gradient Penalty—share the same fundamental adversarial learning principle, their objective functions differ in the way the discriminator (or critic) estimates the divergence between real and generated data distributions. A general equation is employed to compute the loss of the generator component for the three utilized GAN models:

Adversarial, perceptual, and L1 losses are utilized for the backpropagation of the generator part of our network. The adversarial loss of the used vanilla GAN is directed by the Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) loss, which is frequently employed in binary classification and adversarial learning problems. It quantifies the divergence between the expected probability and the actual binary labels. Binary Cross-Entropy loss [26] was adopted to measure the discriminator’s performance, as it effectively quantifies the divergence between predicted and real probability distributions [30]. The adversarial loss, used in the vanilla GAN model, is expressed as

where denotes synthesized samples. The BCE formulation encourages the generator to create textures that enhance the discriminator’s probability of misclassification, hence fostering perceptual realism.

Moreover, WGAN and WGAN with Gradient Penalty models are based on the mean function of the computation of their adversarial loss.

This approach enhances gradient smoothness and augments convergence stability in adversarial training.

The term represents the pixel-wise reconstruction loss, which measures the absolute difference between the generated image and the corresponding ground truth target. This loss encourages the generator to produce outputs that are structurally consistent with the reference images by minimizing large deviations in pixel intensity values. The L1 loss [6,7] was incorporated to enforce pixel-wise consistency between generated and target images, minimizing structural deviations while complementing the adversarial objective. The loss is defined as follows:

where denotes the generated image, is the ground truth target image, and is a weighting coefficient that controls the contribution of this loss term during training. In all GAN models, the loss helps the generator maintain spatial coherence and preserve fine structural details while reducing pixel-level noise.

The perceptual loss function [31] is utilized to assess the high-level similarity between the generated image and its associated ground truth, focusing not only on the pixel-level comparison but also inside the feature space of a pretrained convolutional neural network. In contrast to pixel-based metrics like L1 loss, which mainly assess low-level intensity variations, perceptual loss measures structural and semantic fidelity by analyzing deep feature activations obtained from a reference network.

This study employed the framework established by Johnson et al. [31] and utilized the VGG-19 network [32] to calculate perceptual loss. The rationale for utilizing VGG-19 in this framework is its deeper architecture, which offers a more comprehensive feature space for capturing detailed mid- and high-level textural and structural information. The hierarchical representations enable the model to identify perceptually important differences in texture, edge alignment, and material continuity, which are crucial for texture-aware synthesis tasks. The perceptual loss for each of the three models utilized (vanilla GAN, WGAN, and WGAN-GP) is specified as follows:

where , denote the generated and ground truth images, respectively, and is the scaling factor that equilibrates the perceptual component within the overall generator loss. The integration of perceptual loss compels the generator to maintain intricate texture details and material consistency, resulting in visually coherent outcomes that correspond with human perception. The integration of adversarial, pixel-based, and perceptual objectives enables the model to effectively balance realism and structural precision.

Besides the generator, the discriminator plays a crucial role in distinguishing real images from synthetically generated ones, guiding the generator toward producing more realistic textures and material structures. Depending on the chosen adversarial framework, the discriminator loss function varies across the three implemented models—vanilla GAN, WGAN, and WGAN-GP—each incorporating distinct formulations to improve stability and convergence.

In the vanilla GAN framework, the discriminator is optimized using the BCE loss function [26]. This objective measures the divergence between predicted probabilities and true binary labels, encouraging the discriminator to correctly classify real and generated samples. The discriminator loss is expressed as follows:

where denotes the discriminator output, represents real samples, and the samples of generated images. This formulation penalizes incorrect classifications symmetrically and is widely used in conventional adversarial training.

WGAN [27] modifies the adversarial training objective by replacing the BCE loss with the estimation of the Earth Mover’s (Wasserstein-1) distance, which provides smoother gradients and better stability. The discriminator, referred to as the critic in this context, minimizes the following objective:

subject to the 1-Lipschitz constraint, typically enforced through weight clipping. This formulation measures the mean difference between real and fake scores, alleviating mode collapse and improving convergence.

To address the limitations of weight clipping, the WGAN-GP [28] introduces a gradient penalty term that enforces the Lipschitz constraint more effectively. The discriminator loss is expressed as

where denotes samples interpolated between real and fake images, and is the gradient penalty coefficient. Equation (11) provides a smoother optimization landscape, ensuring more stable training and preventing gradient vanishing or explosion. Figure 9 also provides a description of the methodologies employed to compute the losses of the generator and discriminator.

Figure 9.

Summary of Used Loss Functions.

4. Experimental Setting

All experiments were performed on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4060 GPU (8 GB VRAM), Intel i9 CPU, and 128 GB RAM, operating under Windows 11, 64-bits operating system. This setup provided sufficient computational resources for training the GAN variants while maintaining efficient memory management. Prior to training, all images were resized to a uniform spatial resolution of 512 × 512 pixels and normalized to the [0, 1] intensity range. The Adam optimizer is used for both the generator and the discriminator. The models were trained using a learning rate of . To balance structural correctness, perceptual quality, and training stability, the hyperparameters for the loss terms were set to , , and . Following the standard WGAN-GP training protocol, the discriminator (critic) was updated times for every generator iteration. For the model development and training stages, the PyTorch deep learning framework was employed, with CUDA acceleration to fully utilize GPU parallelism. Supporting libraries—including Torchvision (v0.22.1 cuda 12.6), Matplotlib (v3.10.3), OpenCV (v4.12.0), and Pillow (v11.3.0)—were used for dataset handling, image preprocessing, visualization, and quantitative evaluation.

5. Results

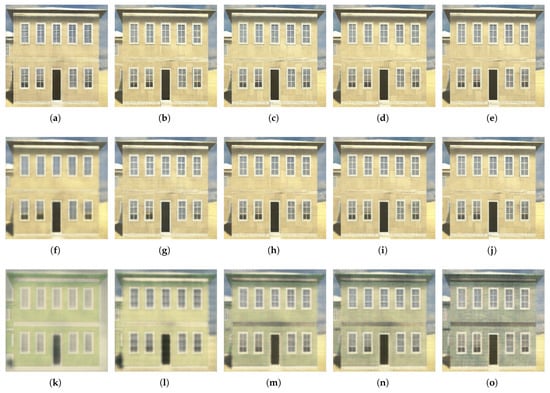

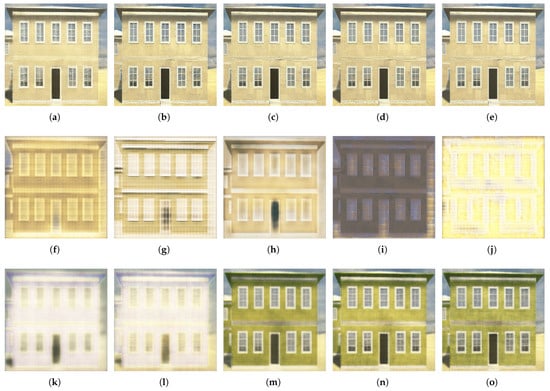

The progression of the training process demonstrates significant variations in the manner each adversarial model acquires texture and material representation. Figure 10 and Figure 11 illustrate that the Vanilla GAN and WGAN models of with channel-wise attention and only the Vanilla GAN model without channel-wise attention exhibited consistent enhancement in visual quality during the training epochs, attaining more defined façade textures and improved structural alignment after roughly 500 epochs. Conversely, the WGAN-GP model produced smoother yet softer outcomes, signifying a delayed convergence in accurately capturing intricate texture patterns. Although gradient penalty regularization enhanced training stability, it also somewhat limited the model’s ability to replicate high-frequency details.

Figure 10.

Outcomes following evaluations with identical inputs of marble material at every 100 epochs throughout the training process with channel-wise attention: (a–e) correspond to results from Vanilla GAN, (f–j) results from Wasserstein GAN, and (k–o) results from Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty. The Vanilla GAN and WGAN progressively enhance realism, while WGAN-GP yields smoother but less sharp textures during early epochs.

Figure 11.

Outcomes following evaluations with identical inputs of marble material at every 100 epochs throughout the training process without channel-wise attention: (a–e) correspond to results from Vanilla GAN, (f–j) results from Wasserstein GAN, and (k–o) results from Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty. The Vanilla GAN enhances realism, while WGAN-GP yields smoother but less sharp textures during early epochs.

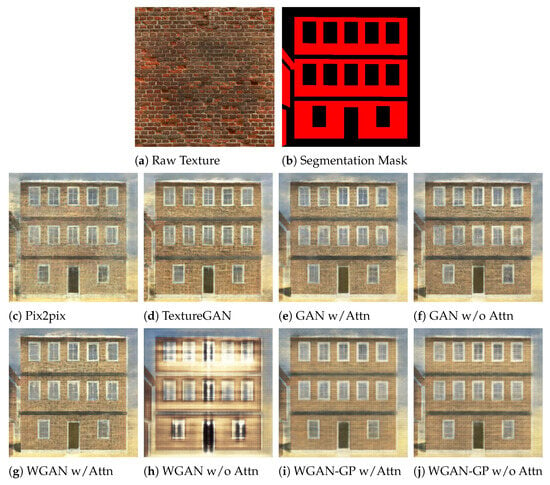

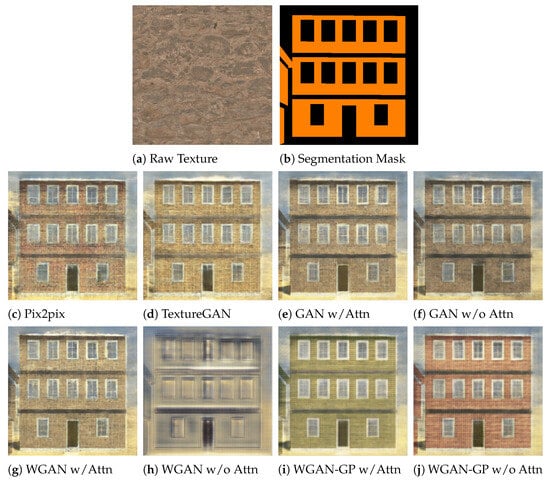

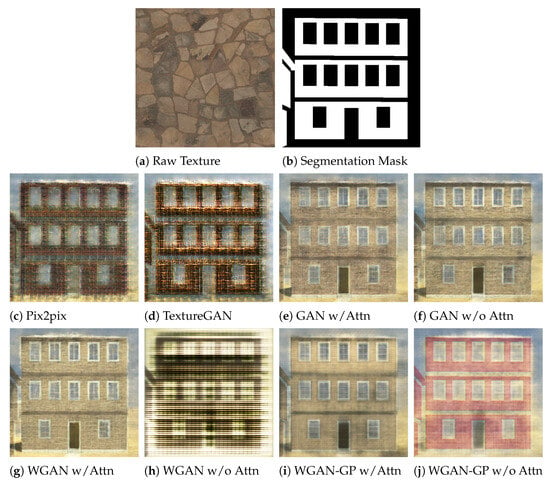

As shown in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14, a consistent qualitative trend is observed across the brick, rock, and stone material samples. For all materials, the inclusion of channel-wise attention leads to visibly improved texture fidelity and sharper structural boundaries compared to their non-attention counterparts. In particular, the conventional GAN with channel-wise attention produces the most visually convincing results, preserving fine-grained texture details and clear material boundaries that closely resemble real-world surface appearances. While the WGAN-based models generate smoother and more uniform textures, they exhibit a noticeable loss of high-frequency details, especially in the absence of attention mechanisms. The WGAN-GP variants further accentuate this effect, often resulting in overly smoothed surfaces with reduced perceptual sharpness. These qualitative evaluations indicate that channel-wise attention consistently improves texture realism across all adversarial frameworks, with the typical GAN architecture deriving the greatest advantage from the suggested attention method.

Figure 12.

Qualitative comparison results for the brick material. The first row presents the raw texture and the corresponding segmentation mask. The second and third rows show the outputs of Pix2Pix, TextureGAN, and the proposed GAN, WGAN, and WGAN-GP models with and without channel-wise attention.

Figure 13.

Qualitative comparison results for the rock material. The first row presents the raw texture and the corresponding segmentation mask. The second and third rows show the outputs of Pix2Pix, TextureGAN, and the proposed GAN, WGAN, and WGAN-GP models with and without channel-wise attention.

Figure 14.

Qualitative comparison results for the stone material. The first row presents the raw texture and the corresponding segmentation mask. The second and third rows show the outputs of Pix2Pix, TextureGAN, and the proposed GAN, WGAN, and WGAN-GP models with and without channel-wise attention.

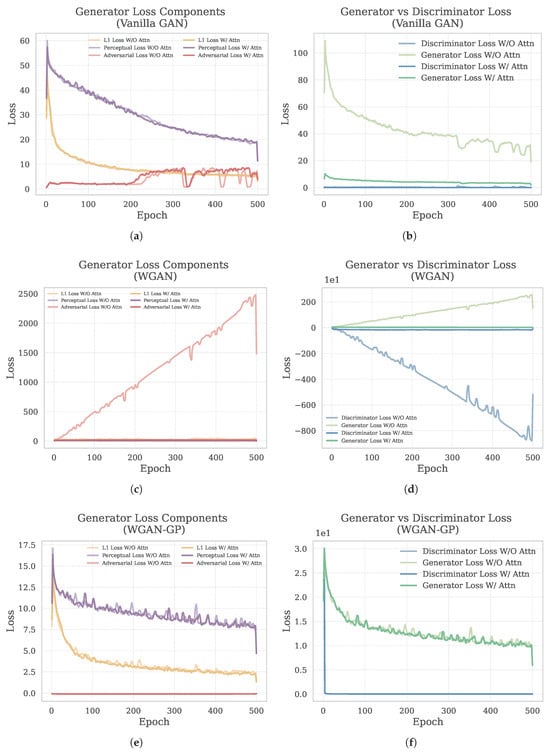

The loss curves depicted in Figure 15 demonstrate the training dynamics of the GAN, WGAN, and WGAN-GP models, both with and without channel-wise attention. In the Vanilla GAN (Figure 15a,b), the components of the generator loss diminish continuously, with channel-wise attention facilitating accelerated convergence and a more equitable generator–discriminator interaction. A comparable pattern is seen in the WGAN model (Figure 15c,d), wherein attention diminishes loss variance and fosters more stable optimization throughout epochs. Conversely, the WGAN-GP model (Figure 15e,f) demonstrates significant oscillations in both generator and discriminator losses, typical of gradient-penalty-based training, potentially constraining pixel-level reconstruction precision. These results demonstrate that whereas WGAN-GP imposes more robust regularization, the Vanilla GAN and WGAN architectures—especially when augmented with channel-wise attention—attain more efficient convergence and superior alignment between adversarial and reconstruction goals.

Figure 15.

Training loss comparison of GAN, WGAN, and WGAN-GP models. (a,c,e) show generator loss components (L1, perceptual, and adversarial losses),while (b,d,f) illustrate the relationship between generator and discriminator losses.

To provide a comprehensive assessment of the synthesized textures, we employed a multi-dimensional evaluation protocol covering pixel-level fidelity, distribution similarity, and perceptual quality,according to the results given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison of different GAN models on texture synthesis metrics. ↑ indicates higher is better. ↓ indicates lower is better. Bold numbers denotes the best results among all methods.

- Pixel-wise Metrics: We utilized Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) [20] to measure reconstruction error and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) [15] to evaluate structural degradation. While baselines like TextureGAN achieved higher PSNR values, this metric often penalizes the high-frequency stochastic variations inherent in rough textures. Conversely, our proposed method achieved higher SSIM scores, indicating better preservation of the structural layout defined by the segmentation masks.

- Distribution Metrics: To assess realism, we calculated the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) [16] and its unbiased estimator, Kernel Inception Distance (KID) [17]. These metrics measure the distance between the feature distributions of real and generated images. The significantly lower FID and KID scores achieved by our Vanilla GAN and WGAN variants (e.g., FID ≈ 104) confirm that our generated textures are statistically closer to the real data manifold compared to WGAN-GP and other baselines.

- Perceptual Metrics: Addressing the limitations of pixel-based metrics, we adopted Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) [19] and Deep Image Structure and Texture Similarity (DISTS) [18]. LPIPS evaluates distance in deep feature space, aligning closely with human perception, while DISTS explicitly focuses on texture and structure consistency. Our method demonstrated superior performance with the lowest LPIPS and DISTS scores, quantitatively validating its ability to synthesize realistic, high-frequency texture details that purely pixel-based models fail to capture.

A Kruskal–Wallis H test [33] was used for all quantitative metrics in order to statistically assess the effect of channel-wise attention. The addition of channel-wise attention produced statistically significant differences for the majority of assessment criteria (), as shown in Table 2, suggesting that the observed performance improvements are not the consequence of random variation. However, in the absence of channel-wise attention, the SSIM measure did not exhibit a statistically significant difference (), indicating that structural similarity by itself is less sensitive to the suggested attention mechanism. Overall, these findings support the idea that channel-wise attention can improve perceptual and distribution-based image quality metrics.

Table 2.

Kruskal–Wallis H test results comparing the effect of channel-wise attention across different evaluation metrics. Statistically significant results () are shown in bold and indicate meaningful differences between the compared methods.

The findings demonstrate that especially the Vanilla GAN with channel-wised attention exhibited enhanced quantitative and qualitative performance for the specified dataset and texture synthesis challenge. Their outputs were more accurate to the ground truth and visually intricate, while WGAN-GP attained only modest enhancements in smoothness, compromising clarity. The results indicate that, in this case, the further regularization provided by the gradient penalty was superfluous and may have constrained the discriminator’s capacity to retain high-frequency input.

6. Discussion

The comprehensive evaluation of the proposed mask-guided texture synthesis framework reveals critical insights into the limitations of pixel-wise metrics and the trade-offs inherent in adversarial training objectives. By contrasting our proposed GAN variants with established baselines such as TextureGAN and Pix2Pix, as well as analyzing internal architectural choices (Vanilla GAN vs. WGAN vs. WGAN-GP), we identify distinct patterns in texture fidelity and structural coherence. A significant finding of this study is the marked discrepancy between traditional pixel-based metrics (PSNR) and modern perceptual metrics (LPIPS, DISTS, FID). As evidenced in the quantitative results, baseline methods like TextureGAN and Pix2Pix achieved the highest PSNR values. However, qualitative visual inspection and perceptual metrics provide a different perspective. These baselines exhibited significantly higher LPIPS and FID scores, indicating that while they minimize pixel-level error, they tend to produce overly smooth and blurry textures that lack high-frequency details. This confirms that PSNR inherently rewards averaging behaviors and penalizes the stochastic variance required for realistic texture synthesis. In contrast, our proposed Vanilla GAN and WGAN models achieved the lowest LPIPS and DISTS scores, quantitatively validating their superior ability to capture perceptual realism and intricate material details that pixel-wise metrics fail to represent.

The comparative analysis of the proposed variants yields further insights. The Vanilla GAN and WGAN architectures demonstrated high learning efficiency, generating clearly defined material patterns with crisp edges. Conversely, the WGAN-GP model, while theoretically designed to stabilize training via gradient penalty regularization, demonstrated a trade-off between stability and sharpness. The gradient penalty term, effectively restricted discriminator divergence but also hindered the model’s capacity to capture sharp, granular texture details, resulting in perceptually smoother but less detailed surfaces compared to the Vanilla GAN. This observation suggests that for specific domains requiring high-frequency texture reproduction, excessive regularization may inhibit the crucial adversarial gradients needed for fine detail generation.

A pivotal contribution of this work is the integration of the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) based channel-wise attention mechanism. The ablation study demonstrates that regardless of the underlying adversarial loss (Vanilla, WGAN, or WGAN-GP), the inclusion of the attention module consistently improved structural consistency (SSIM) and perceptual quality (FID/KID). By explicitly modeling channel interdependencies at the bottleneck, the attention mechanism enabled the generator to better fuse the structural layout from the segmentation masks with the detailed texture statistics from the exemplars. This is corroborated by the significantly reduced DISTS scores in the “Full” models compared to their “w/o Attention” counterparts, highlighting the necessity of intelligent feature fusion in multi-modal synthesis tasks.

7. Conclusions

This study presented a novel mask-guided GAN framework for texture-aware architectural façade generation, integrating a channel-wise attention mechanism to bridge the gap between structural guidance and textural fidelity. Through rigorous quantitative and qualitative comparisons with state-of-the-art methods like TextureGAN and Pix2Pix, we drew several key conclusions.

First, the evaluation highlighted the inadequacy of PSNR for texture synthesis tasks. While baseline methods achieved superior numerical accuracy (high PSNR), they failed to generate convincing high-frequency textures. Our proposed method, particularly the Vanilla GAN and WGAN variants utilizing the attention mechanism, surpassed these baselines in perceptual metrics, achieving the best LPIPS, FID, and DISTS scores. This confirms that our approach generates textures that are statistically and perceptually closer to real-world distributions.

Second, the ablation studies confirmed the critical role of the proposed channel-wise attention module. The integration of this module consistently enhanced structural alignment and texture sharpness across all tested architectures, proving its effectiveness in adaptively recalibrating features for complex material synthesis.

Finally, we observed a distinct trade-off in the WGAN-GP formulation. While it offers training stability, the gradient penalty constraints resulted in a loss of high-frequency detail compared to the standard Vanilla GAN and WGAN. Therefore, for applications prioritizing textural sharpness and visual realism over pure training stability, simpler adversarial formulations combined with robust perceptual losses proved to be the most efficacious configuration.

Future work will focus on bridging the simulation-to-real gap by incorporating real-world façade datasets and exploring diffusion and transformer-based architectures to further enhance global structural coherence. Additionally, we aim to investigate adaptive regularization techniques that can provide the stability of WGAN-GP without compromising the high-frequency detail retention observed in standard GANs. This study utilizes advanced perceptual metrics such as LPIPS and DISTS to assess visual quality; nevertheless, we intend to perform an extensive human perceptual investigation in future research to corroborate these results with subjective human evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Ş. and M.A.B.; methodology, E.Ş. and M.A.B.; software, E.Ş.; validation, E.Ş. and M.A.B.; formal analysis, E.Ş. and M.A.B.; investigation, E.Ş.; data curation, M.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.Ş.; writing—review and editing, M.A.B.; visualization, E.Ş.; supervision, M.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| WGAN | Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network |

| WGAN-GP | WGAN with Gradient Penalty |

| BCE | Binary Cross-Entropy |

| PSNR | Peak Signal to Noise Ratio |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity Index Metric |

| FID | Fréchet Inception Distance |

| KID | Kernel Inception Distance |

| DISTS | Deep Image Structure and Texture Similarity |

| LPIPS | Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity |

References

- Khaksar Ghalati, M.; Nunes, A.; Ferreira, H.; Serranho, P.; Bernardes, R. Texture Analysis and Its Applications in Biomedical Imaging: A Survey. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 15, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.K.; Farrokhnia, F. Unsupervised Texture Segmentation Using Gabor Filters. In Proceedings of the 1990 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics Conference Proceedings, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 4–7 November 1990; pp. 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, T.; Pietikäinen, M.; Mäenpää, T. Multiresolution Gray-Scale and Rotation Invariant Texture Classification with Local Binary Patterns. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, B.S.; Ma, W.Y. Texture Features for Browsing and Retrieval of Image Data. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1996, 18, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scabini, L.; Sacilotti, A.; Zielinski, K.M.; Ribas, L.C.; De Baets, B.; Bruno, O.M. A Comparative Survey of Vision Transformers for Feature Extraction in Texture Analysis. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.-Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation Using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xian, W.; Sangkloy, P.; Agrawal, V.; Raj, A.; Lu, J.; Fang, C.; Yu, F.; Hays, J. TextureGAN: Controlling Deep Image Synthesis with Texture Patches. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Law, S.; Valentine, C.; Kahlon, Y.; Seresinhe, C.I.; Tang, J.; Morad, M.G.; Fujii, H. Generative AI for Architectural Façade Design. Buildings 2025, 15, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Ding, H. Predicting Building Façade Deterioration Using Diffusion Models. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Qi, M.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, Y. Image Inpainting via Conditional Texture and Structure Dual Generation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, B.; Sarafianos, N.; Shapiro, L.; Tung, T. Semi-supervised Synthesis of High-Resolution Editable Textures for 3D Humans. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 7991–8000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, X. Scraping Textures from Natural Images for Synthesis and Editing. In Proceedings of the ECCV 2022: 17th European Conference, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Jiao, W.; Fan, H.; Zhou, G. A framework for fully automated reconstruction of semantic building model at urban-scale using textured LoD2 data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 216, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image Quality Assessment: From Error Visibility to Structural Similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heusel, M.; Ramsauer, H.; Unterthiner, T.; Nessler, B.; Hochreiter, S. GANs Trained by a Two Time-Scale Update Rule Converge to a Local Nash Equilibrium. In Proceedings of the NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Binkowski, M.; Sutherland, D.J.; Arbel, M.; Gretton, A. Demystifying MMD GANs. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vancouver Convention Center, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, K.; Ma, K.; Wang, S.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image Quality Assessment: Unifying Structure and Texture Similarity. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 44, 2567–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. Deep Features as a Perceptual Metric. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2018, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 586–595. [Google Scholar]

- Tanchenko, A. Visual-PSNR Measure of Image Quality. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2014, 25, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulbul, A. Procedural Generation of Semantically Plausible Small-Scale Towns. Graph. Models 2023, 126, 101170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poly Haven Team. Poly Haven—Public Domain Texture Library. Available online: https://polyhaven.com/textures (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Chung, S.H.; Khan, W.A.; Wang, T.; Xu, D.J. ALADA: A Lite Automatic Data Augmentation Framework for Industrial Defect Detection. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 58, 102205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A Survey on Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubuk, E.D.; Zoph, B.; Mane, D.; Vasudevan, V.; Le, Q.V. AutoAugment: Learning Augmentation Policies from Data. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 2019; pp. 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Nets. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2014, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; pp. 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Arjovsky, M.; Chintala, S.; Bottou, L. Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 214–223. [Google Scholar]

- Gulrajani, I.; Ahmed, F.; Arjovsky, M.; Dumoulin, V.; Courville, A.C. Improved Training of Wasserstein GANs. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 5767–5777. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, CVPR Workshops 2018, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.; Alahi, A.; Li, F.-F. Perceptual Losses for Real-Time Style Transfer and Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the ECCV 2016-14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 694–711. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.