Abstract

Fast-growing invasive tree species management produces a significant amount of low-density and low-value biomass, which offers a chance for waste valorization in the environmentally friendly construction sector. This study examines the utilization potential of low-value natural waste materials of tree bark, obtained from invasive hardwood species, in the production of environmentally friendly building mortars. More specifically, this study focuses on mixing bark powder of black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) and tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima (Miller) Swingle), with two commercial commonly found lime-based mortar powders in five different ratios of bark content (0%, 5%, 10%, 20% and 30%) characterizing the produced composites, in terms of physical, hygroscopic and mechanical properties. Slightly lighter composites were created with the use of bark additives especially at the bark content of 20% and 30%. As regards the compressive strength, the bark shares of 10% and 20% exhibited the most beneficial performance among those studied, though only the weaker performance of mortar type (M1) benefited significantly from bark incorporation. For both mortars, the composites containing black locust bark presented higher resistance to compression strength and elasticity, demonstrating higher composite integration in general and milder, plastic fraction in relation to tree-of-heaven bark-based specimens, the properties of which are considered crucial for the durability of structural materials. However, black locust bark exhibited higher water absorption compared to tree-of-heaven-based specimens. Despite the drawback of higher hygroscopicity, the results show that black locust bark, especially at lower incorporation rates (10–20%), is a promising functional additive for generating lighter, more ductile mortars, supporting the creation of novel building materials and sustainable waste management.

1. Introduction

Mortar mixtures that incorporate natural fibers have been recorded extensively in the past, while, over the last few years, researchers have moved even faster towards the utilization of all available residual natural resources in building composite mixture materials, primarily the underutilized and low-value ones.

In an attempt to achieve sustainable development, the employment of natural raw materials for the improvement of building materials, extensive research has been conducted in recent years on the reinforcement of building materials and, in parallel, the employment of raw materials that decrease their environmental footprint [1]. The need to utilize all residual biomass materials has brought to the surface new innovative approaches, which aim both at saving virgin materials traditionally used in construction sector and at improving building materials (incorporating natural fibers/particles), in terms of their weight, porosity, thermal insulation capacity, mechanical resistance to compression and hardness, as well as their degree of swelling-shrinkage, so as to provide higher dimensional stability and efficiency in the building construction [1,2].

In construction projects, mortars are frequently utilized, either in their conventional form, which combines cement, water, and aggregates [3], or with modern mineral admixtures to produce concrete [4]. The main categories of mortars are cement, lime, gypsum, pozzolans and clay-based ones [5]. Aggregate materials such as sand or gravel can be used in combination to create a more malleable and stable product, in terms of volume, strength and structural performance [6].

Furthermore, mortars (applied to the building’s walls to improve the preservation of the walls’ mechanical qualities) appear to have a crucial role [7], maintaining strength and adhesion, while protecting against corrosion. However, the ability of mortars to insulate building structures appears to be a highly significant aspect, which motivates study on the use of mortars made from recovered materials or natural residues. These raw materials function usually as nanofillers [8], i.e., elements that could convert the mortar mixture into appropriate coating materials. The addition of such nanofillers is based on the characteristics of each material regarding the properties they can provide in the protection of structural works but also in their energy enrichment in terms of insulation and heat capacity.

In earlier times, mortar production included natural mortars, such as mud, coarse sand [9] and a small percentage of clay for adhesive purposes. In addition, clay was an important component for primarily bonding the mortar, while at the same time, the addition of straw in some cases contributed to prevention of crack formation during drying and shrinkage of the mortar. However, in some cases, the clay was sieved and mixed with fine straw, with the aim of applying this specific mixture to the outer layer of the mortar for enhanced assimilation [10]. An analysis of the mortars used in previous centuries revealed that natural stone is the best mortar for this particular process. This is in line with research on the preservation of historic buildings with the goal of utilizing contemporary materials that are thought to be able to blend with current ones [11]. In the past, mud, lime, and gypsum were among the basic ingredients used in mortars [12], while these aggregates served as the foundation for the creation of composite building materials employed in building reconstruction in antiquity. It became possible to be characterized and analyzed chemically after the 1980s [13].

Nowadays, mortars have been the subject of several studies, since their combination with natural raw materials can reinforce them and contribute to their energy efficiency, reducing the energy consumption of buildings and achieving indoor air quality and comfort/health for their inhabitants [14]. The composite materials used tend to absorb and release energy from and to the environment, thus regulating the internal temperature and, therefore, energy waste [1,11].

Forest biomass utilization is being studied increasingly nowadays by scientists, towards energy and bio-based product generation, among other uses. In most of those applications, bark is considered a waste material, which is only used to a low extent in refined solid biofuels like pellets/briquettes or burned alongside wood in the raw form of fuelwood [15]. According to the literature, only under specific terms, bark can be mixed with wood to create biofuels that are of acceptable quality [15,16], due to its high ash content, which is much higher than that of wood biomass. According to FAO data, Europe produced around 61 million m3 of wood waste including bark in 2020, compared to 4500 m3 in Greece. Around 233 million m3 was produced worldwide in 2020 [17]. These numbers illustrate the usefulness and necessity of bark utilization for the European market. Some of the most critical characteristics of bark towards its choice for utilization in composite and structural material production, are the content of extracts that infers biological resistance, hydrophobicity and dimensional stability [18].

Since ancient times, tree bark has been used in the production of concrete. According to Littmann [19], during prehistoric times, Maya, Aztecs, Olmecs, etc., began to introduce tree bark into plaster and lime, since they noticed that bark extracts improved the workability and strength of mud or lime while also greatly reducing cracks. In addition, in subsequent experiments carried out by Littman, it was realized that bark’s high tannin levels can be used in the production of plaster stabilizing the mixture during the drying stage. The bark’s mucus, which contains polysaccharides, acts as a plasticizer or thickener. After peeling and soaking the bark in water, the resulting viscous liquid is mixed with soil to create bricks or earthen mortars [20,21]. Bark appears to be quite useful when mixed with cement since it reduces shrinkage and thus cracking as well (the main concern of engineers), according to Woldemariam et al. [22]. Specifically, they highlighted that the extract of blue gum bark can be used as shrinkage shrinkage-reducing admixture in concrete. Kampragkou et al. [2] incorporated cypress bark fine powder and the respective bigger-dimension particles (fibers) in lime-based mortars and reported that bark powder displayed better coherence to the matrix, compared to the corresponding bark fibers, due to the formation of fewer voids in the areas of interface between natural particles and matrix material. They also noted that bark powder of cypress promoted mortar breathability, decreased porosity and capillary absorption. Only a few studies in the literature address the addition of natural fibers into lime-based mortars, though it is highly suggested to advance and develop this type of sustainable material, which could provide a solution for saving energy and natural resources (especially compared to cement matrix) [23].

Invasive tree species are employed for reforestation since they grow well and fast in deteriorated soils. By eradicating native species and opening up new chances in marginal or deteriorated lands, climate change, especially rising temperatures, hastens their expansion [24]. Tree-of-heaven and black locust are two examples of such invasive fast-growing species that thrive because of their high flexibility, quick root systems, and low-nutrient or water requirements [25]. The bark utilization of these two non-native species, which are now quite common in the whole of Europe, is the subject of this study [25,26], since neither of these two wood species’ fibers, nor their bark particles, which are considered waste materials, have ever been employed in lime-based composites reinforcement so far [2]. Both hardwood species possess good-quality ring-porous wood (good strength to weight ratio), which is primarily used to produce energy and cladding wood, though their bark is frequently considered a challenging material to use. Therefore, it is crucial to explore these species’ bark utilization potential and eliminate the excessive accumulation of forestry residues, including bark, in logging or wood processing areas.

The utilization of bark as an additive/partial substitute for traditional raw materials (lime polymeric matrix) in bark–lime composites is examined in this work. In order to decrease building materials’ environmental impact, this research will focus for the first time to the best of our knowledge (according to the literature review) [2] on the underutilized bark of invasive species of black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) and tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima (Miller) Swingle) of Greek origin. In this preliminary experimental work, the bark was crushed up, characterized and introduced in five different ratios in two of the most commonly used commercial lime mortar mixtures. Compressive strength, elasticity, water absorption, and hygroscopic properties of the resultant composites were assessed among others, in order to characterize the resultant prepared composites. In addition to promoting sustainability, the objective is to improve key mortar qualities, including mechanical strength, resistance to cracking, hygroscopicity, dimensional stability and thermal insulation, among others. This work intends to highlight the potential of forest biomass science to introduce, or explore once again, more environmentally friendly building practices, given that by valuing residual biomass, we may reduce building energy requirements, waste accumulation, and the carbon impact of building materials.

2. Materials and Methods

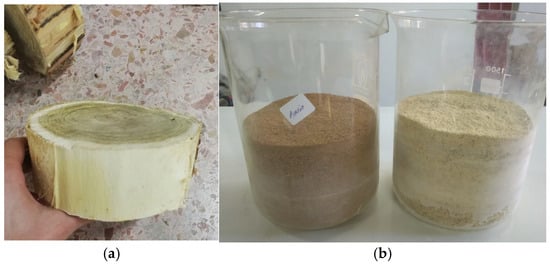

The objective of this study was to examine the impact of incorporation of two different tree bark species, at five different bark contents, in two different matrices of typical commercial lime–mortar (purchased from the market as the two most commonly used), on the performance of the prepared bark–lime composites. Therefore, for the purposes of the current study, two trunks of black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) were obtained from AUTH University Forest (Taxiarchis, Greece), of 7 and 24 years old, respectively, and two trunks of tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima (Miller) Swingle) species of 12 and 18 years old were harvested from the Forest Botanical Garden of Foinikas region (Thessaloniki, Greece). The trunk pieces were cut, numbered and transferred to lab environment, where measurements of their diameters, bark widths and the ratios of bark to wood were implemented. The black locust and tree-of-heaven trunks were of a mean diameter of 15 cm and 23 cm, respectively (measured at the trunk base of the trunks). Black locust trunks tended to be debarked more easily compared to tree-of-heaven species trunks (especially when the tree-of-heaven pieces were freshly cut). Each trunk was cut into 20 pieces/disks approximately 15 cm in height to facilitate the measurements. Respectively, the mean bark thickness for tree-of-heaven for both trunks and black locust was found to be 5.87 mm and 7.63 mm, respectively. When the bark pieces were crushed and pulverized in a Willey mill (Thomas Scientific, Swedesboro, NJ, USA) to prepare the granulometry of 0.25–0.5 mm using the respective 0.5 mm sieve, black locust bark was observed to be pulverized much easily, compared to tree-of-heaven bark, yielding a finer texture bark powder corresponding to the same granulometry (Figure 1). This could be attributed probably to the anatomical characteristics of the two bark tissues. The specific granulometry of fine bark material was chosen since the powder-formed additives usually decrease the porosity of composites, compared to long-natural fiber incorporation [2].

Figure 1.

Trunk piece debarking and processing (a) and preparation of black locust (left) and tree-of-heaven species (right) bark powder (b).

After pulverization, all materials were conditioned under stable conditions (20 °C, 65% relative humidity) till the achievement of constant weight. The equilibrium moisture content (EMC) of the two species of bark powder materials was found to be 9.43% and 8.63% for bark material of black locust and tree-of-heaven species, respectively.

Mortar preparation followed, mixing and blending adequately the powder of mortar material (of the two different types of mortars: Mortar 1 and Mortar 2, M1 and M2, respectively) with the appropriate amount of water as proposed by each mortar’s manufacturer (ratio of 93.3 mL mortar powder: 26 mL water) to be adequately homogenized (laboratory mixing device was employed for 5 min/synthesis). These two mortar types employed in the experimental work were both purchased from the market in packages of 5 kg. The mortar material 1—M1 is a rapid-setting repair mortar of general purpose with the following technical characteristics: Reaction to fire: Class A1, adhesion: 0.4 N/mm2—FP: B, water absorption: W0, water vapor permeability: μ 9, thermal conductivity: (λ10 dry), and durability: (in freezing–thawing). Evaluation of the mortar is based on the provisions in force in the intended application/place where the mortar was applied.

Mortar material 2—M2 is a final layer/surface mortar suitable for indoor and outdoor applications, with proposed ratio of 93 mL mortar to 30 mL of water, and with the following technical characteristics according to the manufacturer: Form: lime/cementitious mortar, granulometry: 0.5–0.15 mm, application temperature: +5 °C to +35 °C, flexural strength after 28 days: 7 N/mm2, and compressive strength after 28 days: 24 N/mm2.

The molds that were formed to receive the mixtures were of 40 × 40 × 40 mm dimensions (Figure 2). The dimensions of the produced specimens are considered ideal for the subsequent measurement of moisture content, density, compression strength, elasticity, hardness, swelling and shrinkage according to the literature [27]. Additionally, Lakshmi et al. [28] and Cemalgil et al. [29], who have conducted experiments on the introduction of natural residues into mortars, state that the mold dimensions of 40 × 40 × 160 mm can be considered even more suitable for the measurements of bending strength in the first step and subsequently (after bending strength test) for compression strength and hygroscopic (absorption/swelling) properties measurement, among others.

Figure 2.

Molds prepared for the specimens’ compression strength test (A), Mortar 1 synthesis materials introduced in the molds (B,C).

The incorporation of the bark material in the mortars was carried out, stirring and homogenizing the mixtures adequately (for 5 min/synthesis at 500 131 r/min) before the syntheses were introduced into the molds, etc. Bark material was incorporated by 0%, 5%, 10%, 20% and 30% of the volume of lime (Mortars 1 and 2). Since there are extremely few relevant studies in the literature for the examination of natural fiber incorporation in lime-based mortars, and even fewer dealing with bark particle incorporation, the authors decided to study in this preliminary work the specific percentages of bark content. According to the literature, a percentage higher than 30% would not have a point since the mechanical strength of those composites would be extremely degraded to be used in building materials/products [2]. The mean moisture content of bark materials at the time of introduction into lime matrix material was 8.6% and 9.4% for tree-of-heaven and black locust species. It was observed that the incorporation of bark changed the workability of the mixtures (especially the black locust bark decreased workability). More specifically, as concerns the black locust species, its incorporation necessitated the introduction of an additional amount of water recording for both mortar types the following ratios:

- Ratio of 7.1–0.38–3 for mortar powder–bark–water for 5% bark content.

- Ratio of 6.7–0.75–3.3 for mortar powder–bark–water for 10% bark content.

- Ratio of 6–1.5–2.5, for mortar powder–bark–water for 20% content.

- Ratio of 5.3–2.2–3.7 for mortar powder–bark–water for 30% bark content.

As concerns tree-of-heaven bark incorporation the proportions of the mixtures were as follows:

- Ratio of 7.1–0.38–3 for mortar powder–bark–water for 5% bark content.

- Ratio of 6.7–0.75–2.6 for mortar powder–bark–water for 10% bark content.

- Ratio of 7.5–1.8–2.5 for mortar powder 1–bark–water for 20% bark content.

- Ratio of 7.5–1.8–3.5 for mortar powder 2–bark–water for 20% bark content.

- Ratio of 5.2–2.2–3 for mortar powder–bark–water for 30% bark content.

All specimens were removed from the molds one week later (5–7 days), to be placed under stable conditions (20 ± 2 °C, 65 ± 3% rh) for 90 days to be cured (ASTM C1585-13 [30]) before the characterization phase. The EMC (%) of the specimens of the different categories was measured based on 5 specimens per material category, and the values are presented in Table 1. As evidenced, no significant differences were marked among the mean EMC values of the specimens of different categories, though Mortar type 1 (M1) revealed a tendency of slightly higher hygroscopicity (higher EMC), which could be attributed to the different chemical composition and properties.

Table 1.

Mean EMC values (%) of the lime–mortar composites for the different bark contents, 0–30%, and the two different mortar types (M1 and M2).

Using laser diffraction analysis, the particle size distribution (PSD) of the raw materials and the lime–bark composites was evaluated. The median particle size (D50) was chosen as the main index for the comparative assessment of the blending effect. The two commercially available lime-based mortars that were employed as matrices were of baseline D50 values of 14 µm (M1) and 17 µm (M2), as observed in Table 2. The shift in fineness was quantified, and the sensitivity of the two mortars to the addition of the coarse organic phase was compared using the evolution of D50 with increasing bark content (from 0% to 30%). This indicator efficiently monitors the gradual coarsening and growing impact of the bark on the total PSD.

Table 2.

Median particle size (MPS) of D50 (μm) of lime–bark composites.

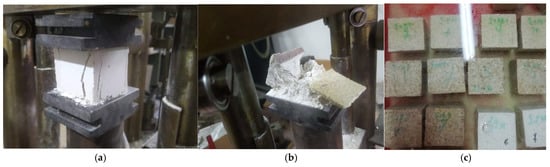

A Universal Testing Machine was used for the testing of samples to assess their mechanical durability against compression forces (Figure 3a,b) and elasticity applying the methodology described in the standards ASTM C 349-02 [31] and ASTM C 469-02e1 [32], respectively. According to the applied standards and literature, 10 samples/category of material have been tested for compression strength and elasticity test to assess mean and standard deviation values.

Figure 3.

Fracture of specimens to measure compression strength and elasticity modulus of materials (a,b), water immersion of specimens in the frame of absorption and swelling test (c).

In order to assess the hygroscopic properties of the prepared samples (40 × 40 × 40 mm), they were accurately weighted with a high-precision analytical scale and immersed in water (tap water of 23 ± 1 °C) for the total duration of 72 h, while weight and dimensions measurements of the samples were carried out before the immersion and after 2, 24 and 72 h of immersion in water. Seven samples were immersed/category for the implementation of hygroscopic property tests (Figure 3c). The equations used for absorption (1) and swelling percentage (2) of the specimens were the following (ISO 13061-15 [33]):

Absorption = ((Weight after immersion − Weight before immersion)/Weight before immersion) × 100

Swelling = ((Dimension after immersion − Dimension before immersion)/Dimension before immersion) × 100

Microsoft Excel software was used for results processing and the preparation of the diagrams and tables of the experimental results, while one-way ANOVA was conducted through SPSS software (version 28, provided by AUTH University). Specifically, we applied Tukey post hoc test of One-Way ANOVA, which, in parallel, runs the test of Tukey HDS (Honesty Significance Difference) to find exactly which group means differ significantly, controlling for Type I errors (false positives) across all pairwise comparisons. Differences were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

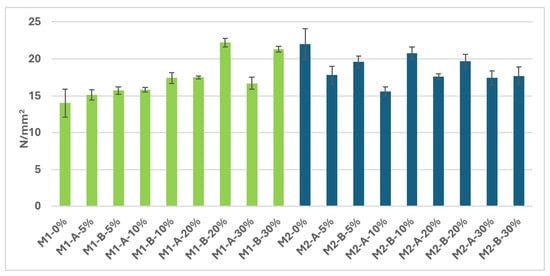

The results of the compression strength test measurements of each different material category are presented in Figure 4. The compressive strength measurements were of great interest, especially in the samples containing black locust bark, since, as it is evident, the groups of these samples recorded the highest compressive strength values. In all categories of Mortar 1, the incorporation of bark benefited the compressive strength of the specimens. Black locust in all cases presented a highly beneficial role compared to tree-of-heaven/ailanthus bark, though both species benefited the compressive strength of the specimens compared to the reference (0% bark). Comparing the control samples of the two mortars, it is apparent that Mortar 2 (M2 reference) marked a statistically significantly higher compressive strength compared to Mortar 1 (M1 reference) strength values (p = 0.008). In the case of Mortar 2, the incorporation of bark did not appear to favor the compressive strength of the specimens, since all the values were found lower than the respective ones of the reference specimens. Nevertheless, black locust bark again benefited more the compressive strength of specimens compared to tree-of-heaven species bark, probably due to the fiber/particle anatomical characteristics and chemical composition of black locust (higher extract content) [34]. According to Kraszkiewicz [35], black locust bark includes per average carbon 48–52%, hydrogen 4.6–6.8%, nitrogen 0.3–0.8%, sulphur < 0.05% (considerably more sulphur and nitrogen than black locust wood or other species bark), pH ~5–7, while it contains potent antioxidants like resveratrol and piceatannol, contributing to decay resistance. As regards the chemical composition of tree-of-heaven species bark, it is characterized by a significant proportion of extractives (15–20%, mainly alkaloids, quassinoids, phenolic compounds, suberin), a relatively high mineral content (7–15%) and pH rather alkaline (>7) [36], which seems to be more compatible to alkaline environment of lime (pH ~12.4).

Figure 4.

Mean compression strength (N/mm2) for the two mortars (M1 in Green and M2 in Blue) and incorporated bark particles of ailanthus species (A) and black locust species (B) at 5 different bark content values (0%, 5%, 10%, 20%, 30%).

The content of 20% of bark introduction in lime–bark composites of the current study was found to be beneficial for both mortars (especially M1) and both bark species (especially black locust). The 10% content of bark seems to improve as well, though without recording such a high improvement, while 30% bark incorporation seems to start to adversely affect the compressive strength of specimens.

Statistical analysis of the research results concerning compressive strength of the bark–lime composites of M1, proved significant differences between average values of the following composites categories presented in Table A1 (multiple pairwise comparison results): M1-Black locust-20% Bark (M1-B-20%) and M1-B-30% with all the other categories of M1 mortar material. M1-B-10% differed significantly from the categories of reference material (M1-0%) and those categories of both species bark at 5% (M1-A-5%, M1-B-5%), as well as the category of tree-of-heaven-10% (M1-A-10%). As regards M2 mortar material samples, the composite categories of M2-A-5%, M2-A-20%, M2-A-30% and M2-B-30% exhibited similar values, while all these categories marked statistically significant differences from the categories of reference material (M2-0%), M2-B-5%, M2-B-10% and M2-B-20% (Appendix, Table A1).

In any case, it was observed that ductility of the composite specimens was greatly improved with the incorporation of bark, increasing proportionally to the bark content. Cracks were detected in the composites, though they were less deep compared to the reference lime-based composites. During the fraction of the composites, no sudden breaking was observed, only a loss of adhesion with the matrix and the composite deformation. According to the literature review, most studies deal with the incorporation of plant-fibers or powders at low content till 2% w/w to matrix material [23]; therefore, it is difficult to compare the performance of the composites prepared in the current study. In any case, when fibers are being utilized (no powders) and incorporated in the matrix, the mechanical properties seem to be more intensively improved (compression, tensile, flexural strength).

Kampragkou et al. [2] mentioned that the granulometry of the bio-additives usually defines the physical, hygrothermal and mechanical behavior of the reinforced mortars, with the more fiber-formed ones to enhance the specimens’ mechanical performance (mainly post fracture), while the powder particles (as used also in the current study) improve the physical properties and dimensional stability. A comprehensive understanding of the morphological influence of the bio-additives could be achieved through more research on the long-term mechanical properties and microstructure of the final bio-reinforced lime-based composites.

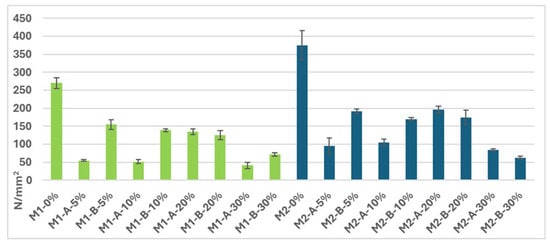

The results of elasticity measured during the compression strength test (Figure 5) revealed that the incorporation of bark material strongly decreased the elasticity of the lime–bark composites in almost all cases corresponding to all bark content levels and both bark species. Mortar 2 revealed statistically significantly higher elasticity values compared to mortar 1 (p = 0.008), though the trend of elasticity decline after the incorporation of bark was quite similar. In most cases, black locust-based composites recorded higher elasticity values compared to tree-of-heaven bark, as observed in the case of compressive strength test performance/tendencies. Mortar 2 reference samples (0% bark) recorded the highest elasticity among all the sample categories, marking statistically significant differences from the rest of the mean values (M1-0% and the categories containing bark). Mortar 1 reference composite specimens followed M2-0% in elasticity values (marking as well statistically significant differences, p < 0.05 from all the rest of mean values recorded in this test, regardless of bark species of type of mortar). Afterwards, the samples of mortar 2 containing 20% black locust bark were the next in mean elasticity values. As regards M1 mortar, the categories of composites containing tree-of-heaven bark at 5%, 10% and 30% recorded similar elasticity values, though all of them differed from all the other categories of M1. Concerning the composite categories of M2, according to statistical analysis (multiple pairwise comparisons, Tukey post hoc test), differences were recorded as well between the categories of 30% bark of both species with all the rest of the mean elasticity values of all the other categories, with composites of 30% bark content to present the lowest elasticity values in both cases of mortars.

Figure 5.

Mean elasticity values during fracture of the specimens (M1 in Green and M2 in Blue) with ailanthus species—A and black locust species—B and 5 different bark content values (0%, 5%, 10%, 20%, 30%).

Quagliarini and Lenci [37] reported as well that Young’s modulus decreases when natural aggregate or fiber content increases in earth-based mortars. For example, the highest modulus was found to be 211 MPa for earth alone, but it fell to between 100 and 150 MPa with an addition of up to 1% of straw. Several scientists have correlated this decrease in Young’s modulus to the compressive strength decrease [38].

In the following, the diagram of Figure 6 shows the mean values of water absorption recorded after the immersion of the samples for 2, 24 and 72 h in tap water. As is evident, comparing the mean absorption values of the samples, there are obvious differences between mortar 1 (M1) specimens and the rest prepared with mortar 2 (M2). In parallel, the difference in absorption values of the samples with the highest percentages of bark (20% and 30%) is of particular interest, since, as the bark percentage increases, the absorption also seems to increase, with tree-of-heaven to exhibit a significantly lower absorption percentage in both cases of mortars (Figure 7). Therefore, the samples of the reference material of the two mortars employed showed a relatively low, not statistically significant difference in absorption values, as mortar M1 recorded a slightly lower absorption percentage. Excluding the reference material, at 20% and 30% of bark introduction, the absorption of the samples of mortar 2 (M2) was found to be higher on both the tree-of-heaven and the black locust. In the samples with a bark percentage of 5% and 10%, the absorption values fluctuated to similar levels without marking statistically significant differences.

Figure 6.

Mean water absorption values (%) of the specimens recorded after 2 h (blue bars), 1 day (24 h—orange bars) and 3 days (72 h—gray bars).

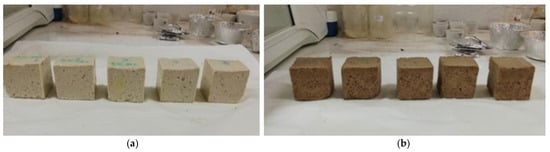

Figure 7.

Images of the composite samples during the time of hygroscopic measurements implementation in order to investigate the dimensional stability ((a): M1 5% black locust bark, (b): M1 30% black locust bark).

Comparing the absorption results recorded from the immersion duration differences, in which the measurements were conducted, an upward trend is observed from one point in time (2 h) to another (24 h, 72 h). However, the picture given by the composites of tree-of-heaven bark is clear, which reveals a significant difference in the absorption rate at each level of immersion duration, which is more apparent in the samples with higher percentages of bark. Statistical analysis of the research results concerning absorption values of the bark–lime composites of M1, exhibited significant differences between the mean values of the following composites categories: Reference M1 with the categories of 5%, 10% and 20% bark of both species (tree-of-heaven and black locust). Absorption values of the specimens containing 30% bark of both species marked similar values to those of the Reference M1 category (M1-0%), though presenting statistically significant differences from the rest of the material categories of M1 mortar. As regards absorption values of M2 categories, composites of black locust-10% (M2-B-10%) and M2-B-30% marked the highest mean absorption values, marking statistically significant differences from the rest of the composite categories and the reference category of M2 (M2-0%) as well.

At the same time, measurements were implemented regarding the dimensions (length, width and height) of the samples, in order that the swelling of specimens’ dimensions be recorded. Based on the above measurements, the mean value and the standard deviation value of the dimensions of each group of samples were obtained.

The differences between the categories of the samples are visible but certainly not statistically significant, apart from the case of differences from the reference of mortar 1 (M1) category. In the rest of the categories, the samples containing tree-of-heaven bark showed a slight increasing trend in all percentages compared to the samples with black locust bark, though without marking statistically significant differences among the mean values of swelling (%). In parallel, among the samples of the same categories, it is obvious that the swelling percentage values difference is negligible, as concerns the length or width of the samples, while in some cases not no increase in their length dimensions was observed, even though there were differences in absorption values of specimens.

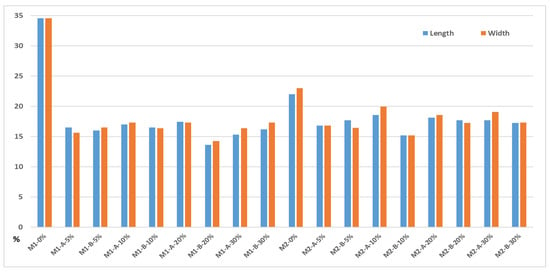

The mean values of the width dimensions (Figure 8) of each group of samples were necessary to interpret the swelling of each sample after 2, 24 and 72 h of immersion in water. A similar observation was implemented with the measurement of the length dimensions, with the reference category of mortar 1 (M1) to record the highest values, while the rest fluctuated at a similar level. Despite the similarity of these values, the differences in values that corresponded to the different immersion durations demonstrated very low, negligible differences (not statistically significant) among the categories, while in some cases the differences were almost zero.

Figure 8.

Length and width swelling (%) of the samples after 72 h of immersion in water.

The above diagram (Figure 8) clearly shows the dimensions of the specimens in the measurements carried out at the third-duration level (72 h). The dimensions and, therefore, the swelling of the specimens did not present statistically significant differences at any of the three levels of immersion duration. Compared to the width–length dimensions, the differences were quite low to negligible. This specific measurement stage revealed encouraging results for the exposure of the composites to environments of increased humidity since mainly minimal dimensional changes were observed in all categories of specimens (even though natural organic material was embedded). In general, the incorporation of hydrophobic bark powder seems to reduce capillary water absorption in lime-based composites, which is a critical theoretical mechanism for enhancing long-term durability [39]. As it is widely known, by limiting moisture ingress, this modification mitigates degradation processes such as freeze–thaw damage and biogenic colonization, thereby extending the service life of the composite material.

According to the literature, some of the natural aggregates/fibers have presented a decrease in the water absorption and swelling by the material, which was intensified with the natural particle weight content. In one of the previous studies, 2% coconut fibers were proven among the most efficient, followed by 2% cellulose fibers, 3% sawdust, 1% coconut fibers, 2% wheat straw and 3% cement (higher humidity sorption after 15 h) [40]. However, there are some other studies reporting that water absorption increased with the addition of natural aggregates or fibers [23], because of their high capacity of absorption, but there have been in total very few studies in the literature on bark–lime mortars. However, in general, humidity regulation is very rapid due to the high permeability of the earth and lime matrix material [41]. Research is still required to complete databases of lime composites containing plant and bark powders, particularly regarding hygrothermal properties of the composites.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanical Performance and the Role of Bark as a Composite Component

The different mechanical performance of mortars M1 and M2 after adding bark emphasizes how important the base matrix composition is in determining how functional bio-based additives perform. The commercially available mortars that were employed in this study were found to differ in a significant way in properties and performance. The increase in compressive strength for Mortar 1 with bark addition—especially with black locust one—indicates a favorable interaction where the bark particles may function as a micro-reinforcement inside the weaker matrix, thereby reducing the spread of cracks. Bark incorporation, on the other hand, predominantly introduces discontinuities and stress concentration areas, outweighing any reinforcing effect, as evidenced by the strength reduction observed for the intrinsically stronger mortar 2 (M2). This emphasizes that bark is an active composite element whose influence is matrix-dependent rather than just a filler. Remarkably, black locust bark outperforms tree-of-heaven in terms of strength and preserved elasticity across all mixtures, indicating inherent material advantages. These may be triggered by its chemical composition (such as tannins, phenolics content) and anatomical structure (such as cell shape and aspect ratio), which seem to promote improved interfacial bonding with the lime matrix, resulting in a more integrated and durable composite. For both species, the ideal performance emerges at a bark share of 20%, which strikes a critical balance between maximizing bio-content and preserving structural integrity. Beyond this point, for example, at 30%, the binding matrix dilution takes over, weakening the composites.

4.2. Hygroscopic Behavior and Implications for Material Durability and Application

The bark–mortar composites’ hygroscopic characteristics show a defining feature for their potential uses. The introduction of hydrophilic organic material into the inorganic matrix was expected to result in a significant increase in water absorption with increased bark content (20%, 30%). However, a crucial discovery is that tree-of-heaven-based composites showed significantly lower absorption than the respective black locust ones. This indicates that tree-of-heaven bark may be more beneficial in applications when moisture resistance is crucial due to basic differences in the bark’s porosity, chemical hydrophobicity, or interaction with the mortar. Notably, length and width swelling values following a 72 h immersion were insignificant, indicating that this enhanced water uptake did not result in significant dimensional swelling in any composite. The marked differentiation between absorption and dimensional instability seems to be very promising, since it shows that, even though the composites absorb moisture, the bark particles are sufficiently constrained and well-integrated within the hardened matrix to avoid the expansive strains that usually cause frost damage or cracking. Because of its higher hygroscopicity, black locust bark requires design considerations, such as use in sheltered environments or with integrated water repellents, even if it provides superior mechanical enhancement. Tree-of-heaven bark, on the other hand, may be even more appropriate for non-structural, insulating, or finishing mortars when weight and moisture dynamics are the main concerns due to its reduced mechanical contribution, though superior moisture performance.

5. Conclusions

Lime-based composites that were lighter and dimensionally more stable were created with the addition of bark material. Mortar 2 performed better than Mortar 1 material in terms of mechanical, physical and hygroscopic properties, due to the different compositions and reacted differently when the bark material was incorporated. Regarding the mechanical strength performance, it was noticed that the tree-of-heaven bark-based specimens crumbled faster compared to those of black locust, and their rupture was observed to be more intense compared to black locust. At higher percentages of participation of tree-of-heaven and black locust bark, fraction appeared faster at low levels of strength. As evidenced, the strength of black locust-based samples was higher on average, while in parallel the elasticity showed higher percentages in the samples of black locust bark powder. In general, the samples containing black locust bark provided enhanced behavior overall, while in a few cases the samples with tree-of-heaven bark outperformed in strength.

Concerning the hygroscopic property measurement, a gradual water uptake was observed. It is noteworthy that absorption was clearly higher in the samples of a higher bark content, with tree-of-heaven bark to fluctuate at low levels of absorption, while, in the groups of lower bark participation percentages, absorption was at close levels between the two groups that contained the same bark share. In general, negligible swelling levels were observed. In conclusion, the bark content of the samples seems to play a decisive role in their properties, with 10–20% to be proven as the most favorable (bark presence by >20% seems to be totally out of interest), while it appears to be necessary to continue similar research efforts exploring lower bark contents with the aim of subsequently improving the production of mortars utilizing the lignocellulosic waste of bark in a rational way.

Further investigation into the long-term mechanical properties and on the microstructure of the final bio-reinforced lime-based composites could contribute to a thorough understanding of the bio-additives’ morphology impact, while more experiments are necessary for the optimization of the bark content and granulometry, to obtain the most efficient material.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.K. and I.B.; methodology, I.B. and V.K.; software, V.K. and G.P.; validation, G.P. and V.K.; formal analysis, G.P.; investigation, G.P. and V.K.; resources, I.B.; data curation, V.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P.; writing—review and editing, V.K.; visualization, V.K. and G.P.; supervision, I.B.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Statistically significant differences among materials categories (Groups) compressive strength values and the respective p-adjusted values (Sig.).

Table A1.

Statistically significant differences among materials categories (Groups) compressive strength values and the respective p-adjusted values (Sig.).

| Group 1 | Group 2 | p-Adjusted Values (Sig.) |

|---|---|---|

| M1-0% | M1-B-10% | 0.02 |

| M1-A-20% | 0.012 | |

| M1-B-20% | 0.0085 | |

| M1-B-30% | 0.0076 | |

| M2-0% | 0.008 | |

| M2-B-5% | 0.013 | |

| M2-B-10% | 0.006 | |

| M2-A-20% | 0.023 | |

| M2-B-20% | 0.015 | |

| M2-A-30% | 0.03 | |

| M2-B-30% | 0.03 | |

| M1-A-5% | M1-B-10% | 0.032 |

| M1-A-20% | 0.03 | |

| M1-B-20% | 0.008 | |

| M1-B-30% | 0.0085 | |

| M2-0% | 0.009 | |

| M2-B-5% | 0.015 | |

| M2-B-10% | 0.007 | |

| M2-A-20% | 0.029 | |

| M2-B-20% | 0.018 | |

| M2-A-30% | 0.03 | |

| M2-B-30% | 0.032 | |

| M1-B-5% | M1-B-10% | 0.036 |

| M1-A-20% | 0.035 | |

| M1-B-20% | 0.009 | |

| M1-B-30% | 0.0096 | |

| M2-0% | 0.01 | |

| M2-B-5% | 0.019 | |

| M2-B-10% | 0.008 | |

| M2-A-20% | 0.03 | |

| M2-B-20% | 0.021 | |

| M2-A-30% | 0.032 | |

| M2-B-30% | 0.034 | |

| M1-A-10% | M1-B-10% | 0.037 |

| M1-A-20% | 0.035 | |

| M1-B-20% | 0.011 | |

| M1-B-30% | 0.0097 | |

| M2-0% | 0.012 | |

| M2-B-5% | 0.02 | |

| M2-B-10% | 0.008 | |

| M2-A-20% | 0.032 | |

| M2-B-20% | 0.023 | |

| M2-A-30% | 0.032 | |

| M2-B-30% | 0.035 | |

| M1-B-10% | M1-B-20% | 0.034 |

| M1-B-30% | 0.03 | |

| M2-0% | 0.033 | |

| M2-B-5% | 0.039 | |

| M2-A-10% | 0.044 | |

| M2-B-10% | 0.032 | |

| Μ2-Β-20% | 0.039 | |

| M1-A-20% | M1-B-20% | 0.028 |

| M1-B-30% | 0.025 | |

| M2-0% | 0.031 | |

| M2-B-5% | 0.033 | |

| M2-A-10% | 0.041 | |

| M2-B-10% | 0.03 | |

| Μ2-Β-20% | 0.031 | |

| M1-B-20% | M1-A-30% | 0.034 |

| M2-A-5% | 0.036 | |

| M2-A-10% | 0.011 | |

| M2-A-20% | 0.027 | |

| M2-A-30% | 0.028 | |

| M2-B-30% | 0.027 | |

| M1-A-30% | M1-B-30% | 0.03 |

| M2-0% | 0.022 | |

| M2-B-5% | 0.029 | |

| M2-B-10% | 0.031 | |

| M2-B-20% | 0.038 | |

| M1-B-30% | M2-A-5% | 0.042 |

| M2-A-10% | 0.0076 | |

| M2-A-20% | 0.041 | |

| M2-A-30% | 0.044 | |

| M2-B-30% | 0.042 | |

| M2-0% | M2-A-5% | 0.038 |

| M2-A-10% | 0.016 | |

| M2-A-20% | 0.029 | |

| M2-A-30% | 0.031 | |

| M2-B-30% | 0.029 | |

| M2-A-5% | M2-A-10% | 0.044 |

| M2-B-10% | 0.047 | |

| M2-B-5% | M2-A-10% | 0.02 |

| M2-A-20% | 0.046 | |

| M2-A-10% | M2-B-10% | 0.011 |

| M2-A-20% | 0.044 | |

| M2-B-20% | 0.016 | |

| M2-B-10% | M2-A-20% | 0.047 |

| M2-A-30% | 0.044 | |

| M2-B-30% | 0.046 | |

| M2-A-20% | M2-B-20% | 0.044 |

| M2-B-20% | M2-A-30% | 0.045 |

| M2-B-30% | 0.047 |

References

- Kesikidou, F.; Stefanidou, M. Natural fiber-reinforced mortars. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 25, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampragkou, P.; Dabekaussen, M.; Kamperidou, V.; Stefanidou, M. Bio-additives in lime-based mortars: An investigation of the morphology performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 474, 141177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzileroglou, C.; Stefanidou, M.; Kassavetis, S.; Logothetidis, S. Nanocarbon materials for nanocomposite cement mortars. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 6938–6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, M.; Lawrence, P.; Ringot, E. Mineral admixtures in mortars: Qualification of the physical effects of inert materials on short-term hydration. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 719–730. [Google Scholar]

- Moropoulou, A.; Bakolas, A.; Bisbikou, K. Physico-chemical adhesion and cohesion bond in joint mortars imparting durability to the historic structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2000, 14, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidou, M.; Papayianni, I. The role of aggregates on the structure and properties of lime mortars. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2005, 27, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, Z.W., Jr. Mortars. In Encyclopaedia of Polymer Science and Technology; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Montanari, G.C.; Mulhaupt, R. Polymer nanocomposites as dielectrics and electrical insulation-perspectives for processing technologies, material characterization and future applications. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2004, 11, 763–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Arbad, B.R. Characterization of traditional mud mortar of the decorated wall surfaces of Ellora caves. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 65, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twaissi, S.A.; Abuhalaleh, B.; Abudanah, F.; Al-Salammen, A. The architectural aspects of the traditional villages in Petra region with some anthropological notes. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 7, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventola, L.; Vendrell, M.; Giraldez, P.; Merino, L. Traditional organic additives improve lime mortars: New old materials for restoration and building natural stone fabrics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 3313–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsen, J. Microscopy of historic mortars—A review. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middendorf, B.; Hughes, J.J.; Callebaut, K.; Baronio, G.; Papayianni, I. Investigative methods for the characterisation of historic mortars-Part 2: Chemical characterisation. Mater. Struct. 2005, 38, 771–780. [Google Scholar]

- Frigione, M.; Lettieri, M.; Sacrinella, A. Phase change materials for energy efficiency in buildings and their use in mortars. Materials 2019, 12, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pásztory, Z.; Ronyecz Mohácsiné, I.; Gorbacheva, G.; Börcsök, Z. The utilization of tree bark. BioResources 2016, 11, 7859–7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maj, I.; Niesporek, K.; Płaza, P.; Maier, J.; Łój, P. Biomass Ash: A Review of Chemical Compositions and Management Trends. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindiš, P.; Stajnko, D.; Lakota, M.; Berk, P.; Muršec, B. Energy efficiency of two types of greenhouses heated by wood biomass. In DAAAM International Scientific Book 2012, Proceedings of the 23rd International DAAAM Symposium “Intelligent Manufacturing & Automation”, Zadar, Croatia, 24–27 October 2012; DAAAM scriptorium GmbH: Lankowitz, Austria, 2012; pp. 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Giannotas, G.; Kamperidou, V.; Barboutis, I. Tree bark utilization in insulating bio-aggregates. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin.—BIOFPR 2021, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littmann, E.R. Ancient mesoamerican mortars, plasters, and stuccos: The use of bark extracts in lime plasters. Am. Antiq. 2017, 25, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa, D. Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán; Editorial Porrúa: Mexico City, Mexico, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kita, Y. The Functions of Vegetable Mucilage in Lime and Earth Mortars–A Review. In Proceedings of the 3rd Historic Mortars Conference, Glasgow, Scotland, 11–14 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Woldemariam, A.M.; Oyawa, W.O.; Abuodha, S.O. The use of plant extract as Shrinkage Reducing Admixture (SRA) to reduce early age shrinkage and cracking on cement mortar. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. 2015, 13, 136–144. Available online: https://ijisr.issr-journals.org/abstract.php?article=IJISR-14-302-10 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Laborel-Préneron, A.; Aubert, J.E.; Magniont, C.; Tribout, C.; Bertron, A. Plant aggregates and fibers in earth construction materials: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 111, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliou, V.; Barboutis, I.; Kamperidou, V. Strength of corner and middle joints of upholstered furniture frames constructed with black locust and beech wood. Wood Res. 2016, 61, 495–504. [Google Scholar]

- Call, L.J.; Nilsen, E.T. Analysis of interactions between the invasive tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima) and the native black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia). Plant Ecol. 2005, 176, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas, L.H.; Eissenstat, D.M. Linking fine roots traits to maximum potential growth rate among 11 mature temperate tree species. Funct. Ecol. 2004, 18, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topꞔu, I.B.; Bilir, T. Experimental investigation of drying shrinkage cracking of composite mortars incorporating crushed tile fine aggregate. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 4088–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, P.S.; Jayanshakar Babu, B.S.; Balaji, N.C.; Caithra, G.B. Influence of bagasse ash replacement on strength properties of cement mortar. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2019, 10, 954–962. [Google Scholar]

- Cemalgil, S.; Onat, O.; Kayra Tanaydin, M.; Etli, S. Effect of waste textile dye absorbed almond shell on self compacting mortar. Constr. Builting Mater. 2021, 300, 123978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1585-13; Standard Test Method for Measurement of Rate of Absorption of Water by Hydraulic Cement Concrete. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- ASTM C349-02; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic-Cement Mortars, Using Portions of Prisms Broken in Flexure. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2002.

- ASTM C469-02e1; Standard Test Method for Static Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete in Compression. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2002.

- ISO 13061-15; Physical and Mechanical Properties of Wood—Test Methods for Small Clear Wood Specimens. Part 15: Determination of Radial and Tangential Swelling. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- Philippou, I. Wood Chemistry and Chemical Products; Yiahoudi-Yiapouli: Thessaloniki, Greece; Aristotle University of Thessaloniki: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2014; p. 357. [Google Scholar]

- Kraszkiewicz, A. Chemical Composition and Selected Energy Properties of Black Locust Bark (Robinia pseudoacacia L.). Agric. Eng. 2016, 20, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzopoulou, P.; Kamperidou, V. Chemical characterization of Wood and Bark biomass of the invasive species of Tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle), focusing on its chemical composition horizontal variability assessment. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 17, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quagliarini, E.; Lenci, S. The influence of natural stabilizers and natural fibres on the mechanical properties of ancient Roman adobe bricks. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millogo, Y.; Aubert, J.-E.; Hamard, E.; Morel, J.-C. How Properties of Kenaf Fibers from Burkina Faso Contribute to the Reinforcement of Earth Blocks. Materials 2015, 8, 2332–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Slizkova, Z. Hydrophobic lime based mortars with linseed oil: Characterization and durability assessment. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 61–62, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minke, G. Building with Earth: Design and Technology of a Sustainable Architecture, 4th and revised ed.; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2021; p. 224. ISBN 3035622558. [Google Scholar]

- Cagnon, H.; Aubert, J.E.; Coutand, M.; Magniont, C. Hygrothermal properties of earth bricks. Energy Build. 2014, 80, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.