Abstract

This work presents the development and evaluation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) models for the automatic classification of brain tumors in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans. Several deep learning architectures were implemented and compared, including VGG-19, ResNet50, EfficientNetB3, Xception, MobileNetV2, DenseNet201, InceptionV3, Vision Transformer (ViT), and an Ensemble model. The models were developed in Python (version 3.12.4) using the Keras and TensorFlow frameworks and trained on a public Brain Tumor MRI dataset containing 7023 images. Data augmentation and hyperparameter optimization techniques were applied to improve model generalization. The results showed high classification performance, with accuracies ranging from 89.47% to 98.17%. The Vision Transformer achieved the best performance, reaching 98.17% accuracy, outperforming traditional Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architectures. Explainable AI (XAI) methods Grad-CAM, LIME, and Occlusion Sensitivity were employed to assess model interpretability, showing that the models predominantly focused on tumor regions. The proposed approach demonstrated the effectiveness of AI-based systems in supporting early diagnosis of brain tumors, reducing analysis time and assisting healthcare professionals.

1. Introduction

The growing volume and complexity of medical imaging data present a significant challenge for healthcare professionals who must analyze and interpret these images accurately and efficiently. Traditional diagnostic workflows are highly dependent on the expertise and experience of radiologists, making them susceptible to human error, variability between observers, and long analysis times. These limitations can delay diagnosis and compromise early detection of critical conditions, such as brain tumors, which are among the most aggressive and life-threatening forms of cancer.

In recent years, Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL), has emerged as a transformative solution for medical image analysis. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have shown remarkable performance in tasks such as segmentation, classification, and localization of pathological structures in modalities such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Computed Tomography (CT), and X-rays. MRI is the preferred method for brain image analysis due to its non-invasive nature and ability to produce high-resolution, detailed images of brain anatomy [1]. Its superior soft-tissue contrast enables precise localization of tumors and accurate assessment of their size, shape, and extent, which are critical for diagnosis and treatment planning. MRI also provides valuable insight into the impact of tumors on surrounding tissues and supports longitudinal monitoring of tumor progression over time. Therefore, MRI still remains a clinically indispensable tool for comprehensive brain tumor assessment.

Brain tumor MRI analysis presents significant challenges, including subtle lesion boundaries, high intra and inter-tumor variability, overlapping visual characteristics between tumor types, and slice-level ambiguity. In [2], the authors propose an automatic brain MRI tumor segmentation based on a deep fusion of Weak Edge and Context features (AS-WEC). The method emphasizes lesion edges through adaptive weak edge detection, a GRU-based edge branching structure, and a maximum index fusion mechanism for multi-layer feature maps. The experimental results show that AS-WEC outperforms other models in Dice, MAE, and mIoU, demonstrating superior feature extraction and fusion capabilities. The work by [3] provides a comprehensive review of DL methods for brain tumor analysis, organizing approaches by task and model taxonomy. The review summarizes commonly used public datasets, MRI preprocessing techniques, and evaluation metrics. It also discusses key challenges and future directions for improving the clinical applicability and reliability of AI-based brain tumor analysis systems. The study by [4] proposes a 3D brain tumor segmentation framework that addresses multimodality, spatial information loss, and boundary inaccuracies. The model integrates three modules, MIE, SIE, and BSC, applied to the input, backbone, and loss functions of deep convolutional networks. Experiments on BraTS2017–2019 datasets demonstrate that the proposed approach outperforms the state-of-the-art methods. The framework effectively improves modality utilization, spatial feature representation, and boundary segmentation accuracy. The work of [5] highlights the challenges posed by the versatility of tumor morphology, shape, size, location, and texture on MRI, which can vary widely between patients and tumor types. The study presents a comprehensive review of brain tumor imaging, covering analysis tasks, models, features, evaluation metrics, datasets, challenges, and future research directions. The survey [6] provides an in-depth analysis of common brain tumor segmentation techniques, highlighting methods that automatically learn complex features from MRI images for both healthy and tumor tissues. It reviews recent segmentation architectures, discusses evaluation metrics, and identifies directions for improving segmentation and accurate tumor diagnosis. The authors in [7] present a method to characterize variability in segmenting complex tumor shapes with heterogeneous textures and its impact on volumetric assessments across multiple time points. Probabilistic error maps are generated to quantify edge segmentation variability across algorithms, and equivalence testing determines whether observed volume changes are significant.

A key limitation of current AI-based diagnostic systems is their reliance on large, well-annotated datasets, which are often difficult to obtain in medical contexts due to patient privacy, cost, and variability in imaging protocols. Moreover, the black-box nature of DL models hinders clinical adoption, as clinicians require interpretable explanations to trust and validate automated predictions. Additionally, variability in image acquisition protocols and patient populations poses additional challenges to the generalization and robustness of these models.

To address these gaps, this work proposes an AI-based solution for a four-class slice-based classification of brain tumors from MRI images, combining state-of-the-art CNN architectures such as VGG-19, ResNet-50, EfficientNetB3, Xception, MobileNetV2, DenseNet201, InceptionV3, Ensemble and Vision Transformer with XAI techniques, including Grad-CAM, LIME, and Occlusion Sensitivity. This approach aims to achieve high diagnostic performance while improving model interpretability and clinical trust. The proposed solution is trained and evaluated on publicly available MRI datasets and demonstrates strong performance in key evaluation metrics, including Accuracy, Recall, and AUROC.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- Development and evaluation of multiple DL architectures tailored for brain tumor classification from MRI data.

- Integration of XAI methods to enhance interpretability and clinical validation of AI-driven decisions.

- Comprehensive comparison of model performance using standard metrics and visualization-based explainability tools.

- Exploration of ensemble strategies and Vision Transformers to further improve diagnostic accuracy and robustness.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a state-of-the-art overview of the application of AI and DL techniques in medical imaging, with a particular focus on the detection and classification of brain tumors. Section 3 describes the main DL architectures, the evaluation metrics used, and the XAI techniques adopted in this work. Section 4 gives details on dataset preparation, image preprocessing, model configuration, and training strategy. Section 5 and Section 6 present and discuss the simulation results, including a comparative analysis of the models and the interpretation of their decisions using XAI techniques. Finally, Section 7 summarizes the main findings of the work, highlights its contributions and limitations, and suggests possible directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

The literature review conducted within the scope of this work analyzed several recent studies on the application of AI in medical image analysis, including DL and ML techniques aimed at tasks such as segmentation, classification, and disease detection. These studies demonstrate the growing impact of AI in precision medicine, highlighting significant improvements in accuracy, sensitivity, and interpretability of results.

The work of [8] proposed a hybrid segmentation method based on the detection of the morphological edge and the watershed algorithm to identify cancerous cells. The model also integrated the U-Net architecture, achieving high accuracy and sensitivity values. The combination of classical morphological segmentation and DL demonstrated significant improvements in the precision of anomaly detection in medical images. Another study [9] conducted a comparative analysis of different semantic segmentation methods applied in the medical field. Three main approaches were categorized: region-based methods, Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs), and weakly supervised methods. The U-Net, V-Net, and DS-TransUNet architectures stood out for their performance on datasets such as BRATS, LiTS, and DRIVE, demonstrating that model selection strongly depends on the complexity and scale of the clinical images used.

In [10], the authors presented an explainable approach for medical image segmentation, introducing the concept of double-dilated convolution and the Tversky Loss function, which improved model performance in breast tumor segmentation. The study applied XAI techniques such as Grad-CAM and Occlusion Sensitivity, which allow a visual understanding of the regions most relevant to the model’s predictions and reinforce the transparency of clinical decision-making. In [11], the authors provide a systematic review of state-of-the-art XAI methods in medical image analysis, highlighting how they improve transparency and trust in ML and DL decisions. It discusses current challenges, evaluation metrics, and future research directions to enhance XAI adoption in clinical settings. The work by [12] reviews the performance of DL–based classification and detection techniques for brain tumor diagnostics, including CNNs, transfer learning, ViTs, hybrid methods, and explainable AI. It summarizes standard datasets, preprocessing techniques, and recent methodological trends. A comprehensive analysis highlights the growing adoption of ViTs and interpretability-focused models in recent years.

In [13], a comprehensive review of the use of DL in medical imaging is presented, covering architectures such as Le-U-Net, EfficientNetB4, DeepLung, Inception-ResNetV2, ResNet34 and SCDNet. The study analyzed the application of these networks for the detection of brain tumors, skin cancer, and lung and renal diseases, highlighting the role of transfer learning, data augmentation, LSTM, and GANs in improving model generalization when working with limited datasets.

The work of [14] proposed an optimized model based on the VGG-19 architecture combined with an SVM classifier for AI-assisted medical diagnosis. The model incorporated a two-layer optimizer that reduced dimensionality and enhanced feature selection, achieving superior results in skin lesion detection compared to other conventional DL approaches.

In [15], the authors presented a unified approach based on MobileNet, combined with ConvLSTM layers and XAI techniques, applied to various pathologies, including pneumonia, gliomas, and COVID-19. The proposed architecture achieved high levels of accuracy and recall, demonstrating the ability of the network to generalize between different medical modalities and provide interpretable results through Grad-CAM activation maps.

The authors in [16] analyzed the performance of multiple CNN architectures, including EfficientNetB4, VGG16, ResNet-50, DenseNet-169, InceptionResNetV2, ResNet34, and SCDNet. The results showed that transfer learning and data augmentation are essential strategies to overcome medical data scarcity, allowing high accuracy and F1-score values in disease classification tasks.

In [17], the authors conducted a comparative analysis of the main ML techniques applied to medical imaging. Both supervised algorithms—K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Decision Trees—and unsupervised ones—K-Means and PCA—were studied in the detection of brain tumors. The KNN model achieved 100% accuracy, while Decision Trees reached 99.4%, demonstrating the potential of classical algorithms in diagnostic contexts with small datasets.

The article by [18] presented a detailed review of the use of advanced ML techniques for the diagnosis of COVID-19 using X-ray and computed tomography images. Architectures such as U-Net, DeepLabV3, and COPLE-Net, as well as hybrid techniques that combine SVM, PCA, and GANs, were explored. The study described a complete processing workflow from acquisition to classification, demonstrating the crucial role of AI in automated screening and clinical decision support during pandemics.

The authors of [19] examined the use of ViT and multimodal models in digital pathology. The study highlighted the application of GANs for virtual staining of histological slides, molecular alteration prediction, and automatic generation of interpretable clinical reports. The authors concluded that transformer-based models represent a new trend in medical AI, combining high performance with strong clinical interpretability. The review by [20] compares ViTs and CNNs in medical imaging, focusing on robustness, efficiency, scalability, and accuracy. It highlights the growing potential of ViTs, which often outperform conventional CNNs, especially when pre-trained. The findings aim to guide researchers and practitioners in selecting the most suitable DL models for medical image analysis. The study by [21] evaluates several lightweight CNNs and ViTs for multi-class brain tumor classification on MRI images. Tiny-ViT-5M and EfficientNet-b0 achieved top performance with high accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-scores while maintaining low parameter counts, making them suitable for resource-limited clinical settings. The findings highlight the balance between predictive accuracy and computational efficiency, providing a reference for future autonomous diagnostic systems.

In summary, the reviewed studies converge on the conclusion that DL models, particularly convolutional networks and their variants, outperform traditional ML methods in both segmentation and classification tasks for medical images.

Moreover, there is a growing adoption of XAI techniques, which enable the interpretation of results and improve the trust of healthcare professionals in the clinical use of these technologies. Therefore, the literature highlights a consolidated trend towards the integration of explainable, efficient, and multimodal models that combine images, text, and clinical data, paving the way for a new generation of AI-based diagnostic support systems.

Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of selected articles reviewed in the literature that employ AI techniques in the processing and analysis of medical images, with applications in disease segmentation, classification, and diagnosis.

Table 1.

Summary of Selected Articles Used in the Literature Review on AI Applied to Medical Imaging.

2.1. Application Examples

The application of AI in healthcare has evolved significantly, standing out in various commercial and scientific solutions that employ ML and DL algorithms for medical image analysis. These approaches have contributed to increased diagnostic accuracy, reduced analysis time, and optimized clinical workflow, becoming essential tools for medical decision support. Among the most relevant examples of AI applications are platforms widely recognized in the field of medical imaging.

Aidoc [22] is an AI platform focused on radiology, capable of analyzing medical images in real time and helping diagnoses in critical contexts such as emergency departments and intensive care units. It integrates with hospital systems (PACS) to automatically detect severe clinical conditions, including intracranial hemorrhages, ischemic strokes, pulmonary embolisms, vertebral fractures, and aneurysms. Google Health [23], a Google division focused on innovation in digital health, developed an AI system for mammography interpretation to support early detection of breast cancer. The system outperforms average radiologists in sensitivity and specificity while reducing false positives, and provides heatmaps highlighting suspicious regions to assist radiologists in understanding and using its diagnostic outputs. PathAI [24] develops applied AI for digital pathology, analyzing histological biopsy images to identify cellular and morphological patterns associated with cancer. Its software supports the diagnosis of diseases such as liver, prostate, and breast cancers by transforming unstructured pathology images into structured insights that can be integrated with clinical and genomic data. Viz.ai [25] is an AI platform for medical image analysis and clinical workflow optimization, widely used for the detection of emergency strokes. Integrates with PACS and EHR systems and applies DL to identify pathologies in real time, rapidly notifying medical teams. Arterys [26] is a cloud-based AI platform founded in 2011 and acquired by Tempus in 2022, becoming part of a precision medicine strategy that integrates clinical, molecular and imaging data. It offers solutions in multiple specialties, including Cardio, Lung, Neuro, and Breast AI. Compatible with PACS and EHR systems, the platform enables secure remote analysis and collaboration while supporting personalized data-driven medical decision-making. Qure.ai [27] is a health technology company founded in 2016 and based in Mumbai, India, that develops AI-based solutions for automated medical image interpretation. Its products integrate with hospital systems (PACS/RIS) and include tools for lung cancer detection, stroke analysis, and tuberculosis diagnosis, supporting faster screening, clinical follow-up, and improved care coordination through X-ray and CT analysis. Finally, Lunit [28] is a South Korean company founded in 2013 that develops AI solutions for medical imaging and oncology. Its main products include Lunit INSIGHT CXR for chest X-ray analysis and Lunit INSIGHT MMG for mammography. The company also offers solutions for 3D mammography and digital pathology, including prediction of immunotherapy response. In 2025, Lunit partnered with the German Starvision network, deploying its technology in 79 healthcare facilities, and has published over 125 peer-reviewed studies.

2.2. Overview of Databases

The use of a database in this work is essential, as it enables the training, validation, and testing of the models with a substantial volume of medical images. The use of real data provides conditions that closely resemble clinical practice, facilitating the evaluation of the performance of the models in real diagnostic scenarios. This ensures that the models not only learn from the provided examples, but are also capable of correctly identifying diseases in previously unseen images.

Table 2 presents a diverse set of databases used in research in the field of AI applied to medical image analysis. Each database has specific characteristics and is designed for different clinical purposes. Several types of medical imaging modalities are represented, including MRI, CT, mammography, chest X-rays, ultrasound, and dermatoscopic images. The objectives include classification of skin lesion, detection of pneumonia and diagnosis of COVID-19, as well as brain, kidney, and liver tumor segmentation. These databases enable the development and validation of ML and DL models, covering a wide range of pathologies and clinically relevant contexts.

Table 2.

Summary of Databases.

3. Methods

This section describes the methodologies and techniques used in the development of the proposed system for brain tumor classification.

3.1. Architecture Details

The main CNN-based architectures applied to medical image analysis share fundamental structural components, such as convolutional layers and pooling operations. Each model introduces specific architectural variations designed to optimize computational efficiency, accuracy, and adaptability to different tasks, including classification, segmentation, and pattern detection.

Table 3 provides a detailed comparison of the main architectures implemented in this work, considering essential structural aspects such as the presence of convolutional layers, pooling operations, the use of residual connections (skip connections), activation functions, as well as normalization and regularization techniques. This analysis highlights the characteristics and distinctive features of models such as VGG-19, ResNet-50, EfficientNet-B3, Xception, MobileNetV2, DenseNet201, InceptionV3, the ensemble approach and the ViT, emphasizing their capabilities for critical medical imaging tasks such as lesion or pathology classification and detection. Unlike the pretrained CNN architectures, the ViT follows a fundamentally different design [39]. ViT does not use convolutional layers; instead, input images are divided into fixed-size 16 × 16 patches that are linearly projected into patch embeddings. Conventional pooling operations are omitted, with global representations obtained via a dedicated [CLS] token and attention-based aggregation. Although ViT lacks convolutional skip connections, residual connections are incorporated within each transformer block to support gradient flow. Furthermore, ViT uses GELU activations instead of ReLU and applies Layer Normalization within transformer blocks to ensure training stability.

Table 3.

Comparison of Architectures.

3.2. Performance Metrics

Here, the main metrics used in the evaluation of medical image models are described, with a particular focus on disease classification tasks.

Accuracy is a common metric used to assess the performance of classification models [40]. This metric represents the percentage of correct predictions made by the model in the test data, allowing an objective comparison of performance between different architectures.

where:

- N—Total number of samples in the test dataset;

- —Class predicted by the model for sample i;

- —True class of sample i;

- —Indicator function that takes the value 1 when the prediction is correct and 0 when it is incorrect.

Precision evaluates the proportion of true positives among all instances classified by the model as positive. This metric is particularly relevant in contexts where false positives may have significant clinical consequences [15].

where:

- —Represents cases identified as true positives;

- —Represents cases identified as false positives.

Recall measures the model’s ability to correctly identify all positive instances. In clinical contexts, this metric is essential to avoid failing to detect cases with relevant pathologies [40].

where:

- —Represents cases identified as false negatives.

The F1-Score corresponds to the harmonic mean between Precision and Recall, providing a balance between both metrics. This measure is useful in contexts where it is important to simultaneously minimize false positives and false negatives [15].

Specificity measures the proportion of true negatives among all actual negative instances. This metric is particularly important when aiming to reduce the probability of misclassifying healthy individuals as diseased [40].

where:

- —Represents cases identified as true negatives.

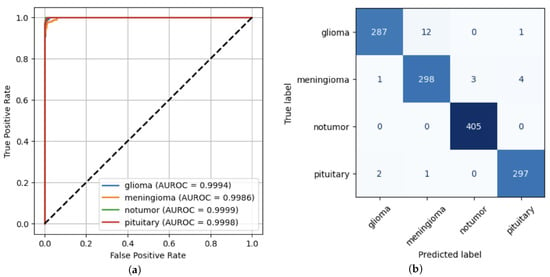

The ROC curve represents the relationship between true positive rate and the false positive rate across different decision thresholds [15]. The confusion matrix provides a detailed analysis of the model’s performance, allowing visualization of the number of correct and incorrect predictions for each class. This tool is particularly useful for identifying the specific types of errors that have been made [14]. Figure 1 shows both the ROC curve and the confusion matrix derived from the evaluation metrics computed for the ViT model. The ROC curves for each class confirm the high discriminative capacity of the model. All classes show AUROC values above 0.998, demonstrating excellent overall discriminative performance. The confusion matrix indicates that the classification errors were minimal, occurring mainly between the glioma and meningioma classes, which exhibit more similar visual characteristics, with true positive values (287, 298, 405, 297), false positives (3, 13, 3, 5), true negatives (1008, 992, 903, 1006) and false negatives (13, 8, 0, 3).

Figure 1.

ViT Model performance. (a) ROC Curve. (b) Confusion Matrix.

Table 4 presents a comparison of the main metrics used to evaluate classification models in the context of AI applied to the medical field. Each metric is described in terms of its fundamental characteristics and typical applications, highlighting the role it plays in model evaluation. This comparison is essential for the correct interpretation of the results obtained, especially in scenarios with class imbalance or where the costs associated with false positives and false negatives vary significantly.

Table 4.

Comparison of Metrics Used in Model Evaluation.

3.3. Applied XAI Techniques

The XAI techniques applied in the present work provide different perspectives on the behavior of the model, as detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Applied XAI Techniques and Clinical Interpretation.

The LIME [41] technique offers a local perspective, allowing the identification of specific regions of the image that contribute significantly to each individual prediction. Although useful for understanding specific decisions, its interpretation may be limited by superpixel resolution and instability in highly complex regions, which can lead to less intuitive relevance maps.

Grad-CAM [42], on the other hand, visually highlights the regions that activate most of the network, providing an intuitive understanding of the focus of the model. The generated activation maps can be compared with the actual anatomical structures in the images, facilitating the validation that the model is focusing on relevant areas. From a critical point of view, Grad-CAM is considered the most effective technique in this context, as it combines visual clarity with anatomical relevance, offering a direct interpretation of the areas that influence the model’s decision.

The Occlusion Sensitivity Technique [10] tests the robustness of the model’s decision, indicating which regions are critical for correct classification by systematically occluding parts of the image and observing changes in the confidence of the model. Although it provides valuable information on the importance of each region, this technique is more computationally expensive and may be less visually intuitive, making rapid interpretation in clinical settings more challenging.

In summary, although each technique presents its own advantages and limitations, Grad-CAM stands out for its ability to deliver clear visual explanations directly relatable to anatomical structures, making it particularly suitable for evaluating models in clinical contexts.

3.4. Dataset

The dataset used in this work is the Brain Tumor MRI Dataset, a well-known and widely used dataset in research and AI projects focused on the automatic detection of brain tumors through MRI [41,43]. This dataset is publicly available on the Kaggle platform and is widely applied in multiclass classification studies using CNNs [44]. Its popularity stems from both its accessibility and the visual clarity of the images, which enable high accuracy even when using relatively simple model architectures. The dataset consists of a total of 7023 JPG images organized into two main directories: Training and Testing, corresponding to training and testing images, respectively. Each of these directories is divided into four subfolders, representing the four classes present in the dataset: glioma, meningioma, notumor and pituitary, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Tree structure of the dataset.

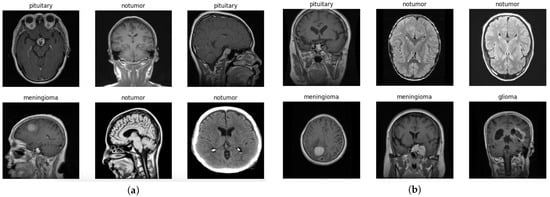

The images are two-dimensional, grayscale, and represent axial slices of MRI scans (Figure 3). The image resolution is standardized to 512 × 512 pixels, which facilitates preprocessing operations.

Figure 3.

Dataset images. (a) Examples of training dataset images. (b) Examples of testing dataset images.

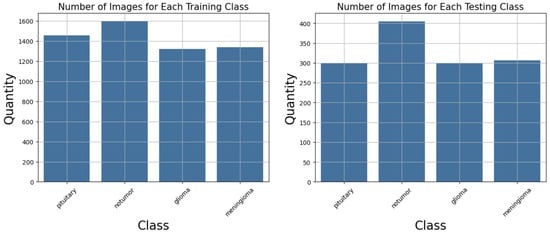

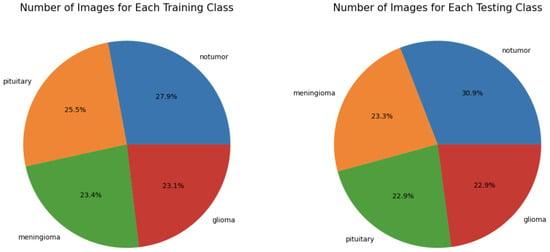

This organization allows the development and evaluation of models capable not only of detecting the presence of tumors but also of distinguishing between glioma, meningioma, notumor, and pituitary classes. Figure 4 shows the number of images for each training and testing class in the dataset. Despite slight variations among classes, the dataset can be considered reasonably balanced, which benefits classification model performance and reduces the risk of bias towards any dominant class.

Figure 4.

Number of images per class in the dataset.

The dataset includes a predefined split between training and testing data, with 81.3% of the images used for training (23.1% glioma, 23.4% meningioma, 27.9% notumor, and 25.5% pituitary) and the remaining 18.7% used for testing (22.9% glioma, 23.3% meningioma, 30.9% notumor, and 22.9% pituitary), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Percentage of images per class in the dataset.

4. Implementation

This section presents the practical implementation of the proposed approach. Details the workflow followed during model development, from data preparation and preprocessing to training and evaluation. The architecture of each implemented model, the corresponding hyperparameters, and the configuration of the training process are also discussed.

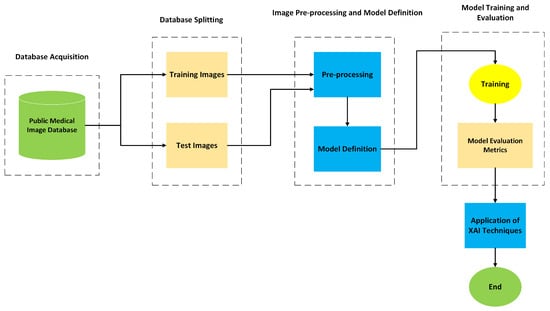

4.1. Proposed Solution

Figure 6 illustrates the overall diagram of the models developed for the detection of brain tumors on medical images. This diagram provides a structured representation of the different stages that make up the processing workflow, from data acquisition to the final evaluation of the model. Each block corresponds to an essential and interconnected phase within the global operation of the system. The workflow begins with the acquisition of the database, composed of medical images, followed by the image pre-processing stage to ensure data quality and consistency. Subsequently, the architectures of the CNNs to be used are defined, followed by the training of the models. After this phase, evaluation metrics and XAI techniques are applied to interpret and analyze the results obtained.

Figure 6.

Diagram of the proposed solution.

- Medical Image Database: This block represents the starting point of the model and corresponds to the repository of medical images used for the development and validation of the system. The images were obtained from public databases, selected based on their quality, anatomical and pathological diversity, as well as their clinical relevance. The dataset is then divided into two subsets, training images and testing images, ensuring a clear separation between the data used to train the models and the data used to evaluate their performance.

- Training and Testing Images: Training images are used to teach the model to identify visual patterns associated with the pathology, allowing it to adjust its internal parameters. The testing images, in turn, are reserved exclusively for evaluating the model’s performance on unseen data, ensuring that the generalization of learned knowledge is effectively tested.

- Pre-processing: Before being fed into the models, all images undergo a pre-processing stage. The purpose of this process is to improve the quality of the input data and to ensure consistency during training.

- Model Definition: Pre-processed images are fed into CNN models selected for their proven effectiveness in classifying and detecting patterns in medical images.

- Training: After defining the architectures, the models enter the training phase, during which they learn from the data previously allocated for this purpose. In parallel, validation is performed to continuously monitor the performance of each model throughout the epochs. This process involves defining a loss function, selecting an optimizer, determining the number of epochs, and analyzing the learning curve. These elements are crucial to ensure that the training process is effective and that the models achieve good generalization performance on unseen data.

- Model Evaluation: Once the training is completed, a quantitative evaluation of the performance of the model is performed. Metrics such as Accuracy, Recall, Specificity, confusion matrix, and AUROC are used for this purpose. These metrics allow for quantification of the effectiveness of the model in the classification task and help identify potential limitations or areas for optimization.

- Application of XAI Techniques: XAI techniques were applied to make the decision-making process of the model more transparent and interpretable. Techniques such as Grad-CAM are used to generate heatmaps that highlight the regions of the image that most influenced the decision of the model. This explanatory capacity is particularly relevant in a clinical context, as it supports the validation of results by healthcare professionals and strengthens trust in the use of AI-based systems.

- End: The solution concludes with the analysis and interpretation of the results obtained.

The modular and systematic structure of this solution ensures not only the scalability and adaptability of the system to different clinical contexts but also its scientific robustness.

4.2. Models

Table 6 details the architecture of each implemented model, including the type of pooling layer, the number of neurons in the dense layers, the use of dropout, the output layer configuration, the optimizer, the loss function and the callbacks used. The type of pooling reduces the spatial dimensions of the feature maps, facilitating the extraction of relevant features. The number of neurons in the dense layers defines the model’s capacity to learn complex patterns, while dropout helps prevent overfitting. The output layer determines the format of the predictions, usually corresponding to the number of classes and the activation function used. The optimizer and loss function guide the learning process, and callbacks enable training monitoring, saving the best model, or dynamically adjusting parameters. This information provides a comprehensive view of the architecture and training strategy of each model.

Table 6.

Comparison of the Implemented Models.

With respect to the training strategy, the validation set was constructed by partitioning a fixed proportion of the training data, while the test set remained completely independent and was not used during either model training or validation. The validation subset was used exclusively to monitor performance and to trigger validation-based callbacks such as EarlyStopping. The predefined test set provided with the dataset was reserved solely for the final performance evaluation. It is important to note that the dataset does not provide patient-level identifiers or metadata. Consequently, the training–validation split was necessarily performed at the image (slice) level rather than at the patient level.

4.3. Data Augmentation

Data augmentation was performed dynamically at runtime, without creating new physical images on disk. The original images were loaded from the training and validation folders using a TensorFlow API function. During training, each batch of images from the training dataset was passed through a preprocessing function that applied data-augmentation strategies. These transformations were applied randomly and independently at each epoch, ensuring that the network was not repeatedly exposed to the same instances. The techniques used included random horizontal and vertical flipping, adjustments to color properties such as brightness, contrast, saturation, and hue, and spatial translation with shifts of up to 20% of the height and width of the image. This procedure enabled the generation of multiple variations in the original images, virtually increasing the size of the dataset and enhancing the robustness of the model to variations in the visual characteristics of the samples.

4.4. Hyperparameters of the Models

Table 7 presents the hyperparameters applied during training, such as image size, batch size, number of epochs, learning rate, number of classes, decay rate and decay step. Each of these hyperparameters plays a crucial role in the performance and convergence of the model. The size of the image defines the resolution of the input images, where larger dimensions can capture more visual details but increase computational cost. The batch size indicates the number of samples processed before the network weights are updated, influencing gradient stability and the frequency of updates. The number of epochs corresponds to the number of times the entire training dataset is traversed during training. A higher number of epochs allows the model to adjust more effectively but increases the risk of overfitting. The learning rate controls how quickly the weights are adjusted; excessively high rates may cause instability, while very low rates result in slower training. The decay rate and the decay step define the gradual reduction in the learning rate, which helps with training stability and network convergence. The number of classes determines the number of distinct categories that the model must learn to classify. Most models used a batch size of 32, except DenseNet201, which used a batch size of 64 due to the complexity of its architecture, and the Ensemble model, which used a batch size of 16 to balance memory usage and gradient diversity during the fusion of model predictions. These choices of hyperparameters reflect a balance between computational efficiency, training stability, and the model’s ability to generalize.

Table 7.

Hyperparameters Used in the Implemented Models.

5. Results

This section discusses the experimental results obtained from the training and evaluation of the implemented models. It includes an analysis of classification performance based on several metrics as well as the interpretability of the models using XAI techniques.

5.1. Setup

The work was developed using the Python programming language, version 3.12.4, employing the Keras framework together with TensorFlow, which served as the execution engine (backend) [45]. Both libraries are open-source and widely used in the development of DL models. For model development and testing, the Jupyter Notebook (version 7.3.2) environment was used as an interactive tool that allows the combination of executable code, visualizations, documentation, and notes in a single document. The combination of these tools proved to be well-suited to the complexity of the problem under study, allowing the training and validation of models with satisfactory performance and generalization capability on the medical image analysis dataset.

Table 8 presents the main specifications of the computer used in this work, including processor, memory, GPU, and storage.

Table 8.

Computer Specifications.

5.2. Performance of the Models

This section presents a summary of the performance of the classification models used in this work. Table 9 shows the per-class metrics, including Precision, Recall, F1-Score, Specificity, and AUROC, as well as the global metrics of each model, such as Accuracy and Loss. The per-class metrics allow for the evaluation of the individual performance of each model for each tumor type, while the global metrics provide an overall view of the model’s effectiveness throughout the dataset. Precision indicates the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples compared to all positive predictions, while Recall measures the model’s ability to correctly identify all positive samples. The F1-Score combines Precision and Recall into a single metric, providing a balance between precision and sensitivity. AUROC values provide a measure of the model’s ability to discriminate between positive and negative classes. Specificity evaluates the ability of the model to correctly identify negative samples. Accuracy indicates the total percentage of correct predictions and Loss measures the average error, reflecting the model’s ability to adapt to the data. A joint analysis of per-class and global metrics is essential to understand the strengths and limitations of the models, identify potential challenges in specific classes, and ensure a comprehensive evaluation of overall performance.

Table 9.

Per-Class Metrics and Overall Performance of Each Model.

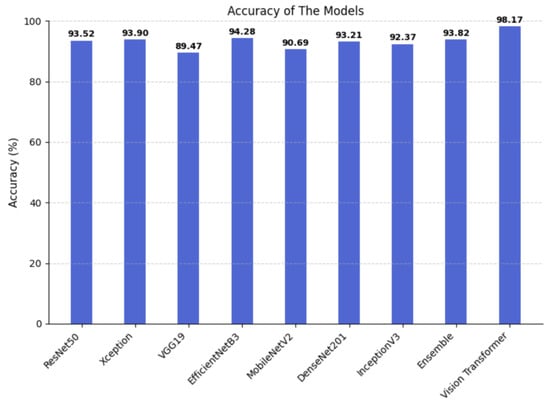

Figure 7 shows the Accuracy achieved by different models in brain tumor classification. It can be observed that all models achieved relatively high Accuracy values, ranging from 89.47% to 98.17%, demonstrating the overall strong performance of the tested architectures. The Vision Transformer model achieved the highest Accuracy, reaching 98.17% and clearly outperforming all other architectures. Next are EfficientNetB3 (94.28%), Xception (93.90%), Ensemble (93.82%), ResNet-50 (93.52%), DenseNet201 (93.21%) and InceptionV3 (92.37%), all of which showed comparable performance. Meanwhile, MobileNetV2 (90.69%) and VGG19 (89.47%) achieved slightly lower results. These results demonstrate that more recent and optimized architectures, such as Vision Transformer and EfficientNetB3, are capable of extracting more discriminative features, leading to significant improvements in performance for medical image classification tasks.

Figure 7.

Accuracy of the implemented models.

Table 10 presents the training times observed for each model implemented in this work. These values reflect the computational performance of the hardware used and allow a comparison of the relative efficiency of each architecture during model training. The inference times of the models, i.e., the average time required by each architecture to process a single image, were also evaluated. This metric is particularly relevant as it is directly related to the efficiency of the model in practical applications and real-time scenarios.

Table 10.

Training and Inference Times of the Implemented Models.

To enable statistically meaningful interpretation and robust comparison between models, confidence intervals were calculated to quantify the uncertainty in classification performance estimates. Table 11 presents the 95% confidence intervals for the accuracy of each model, estimated using the percentile bootstrap method [46]. This approach enables us to quantify the uncertainty associated with the accuracy metric, providing a more reliable and informed performance comparison amongst the models. The bootstrap-based confidence intervals reveal clear performance differences among the evaluated models. ViT achieves the highest and most stable accuracy, indicating superior predictive performance and low variability. VGG19 and MobileNetV2 exhibit lower accuracy ranges and greater uncertainty. EfficientNetB3, Xception, DenseNet201, and the Ensemble model show competitive and statistically similar performance. ResNet50 and InceptionV3 achieve intermediate accuracy levels. Overall, these results demonstrate that ViT consistently outperforms the remaining models.

Table 11.

Confidence intervals for the evaluated models.

5.3. Interpretation of Applied XAI Techniques

In addition to the quantitative analysis of the performance of the implemented models, it was essential to apply XAI techniques with the aim of understanding and interpreting the decisions made by the neural networks. Explainability is a fundamental requirement in clinical contexts, as it not only allows validation of the obtained results but also strengthens the trust of healthcare professionals in the use of AI models as decision-support tools.

In this work, several XAI techniques were employed, namely Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping), Occlusion Sensitivity, and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations). Each of these techniques provides a distinct perspective on how the model processes the image and makes decisions, allowing a more comprehensive analysis of its internal behavior.

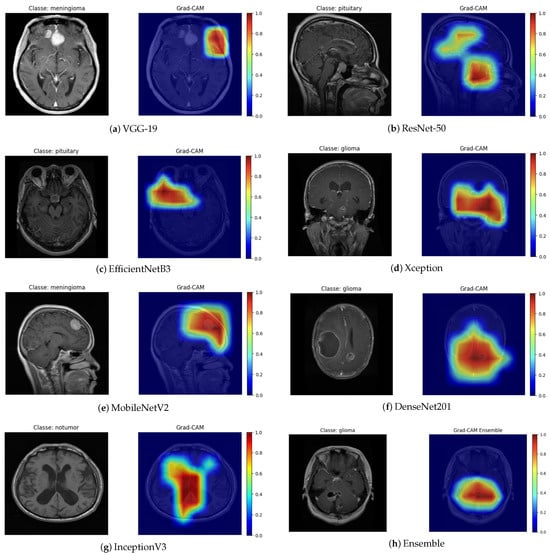

The Grad-CAM technique generates activation maps that highlight the regions of the image that contributed the most to the final prediction. By analyzing the heat maps (Figure 8), it can be observed that the models mainly focus their attention on the anatomical regions corresponding to the brain tumor. The areas highlighted in red indicate higher relevance in the decision-making process, suggesting that neural networks effectively focus on clinically significant regions. This characteristic is particularly important, as it ensures that predictions are not based on noise or irrelevant image artifacts.

Figure 8.

Grad-CAM visualization for different architectures.

The Grad-CAM maps highlight regions that the models consider most important for classification. In most cases, these regions correspond to the approximate location of the tumor, capturing the general area where abnormal tissue is present. For example, in the VGG-19 and MobileNetV2 outputs, the highlighted areas roughly align with the visible tumor mass in the original MRI slice. The DenseNet201 and Ensemble maps also show activations concentrated in the central or upper portions of the tumor, consistent with the lesion’s main location. Overall, the Grad-CAM maps provide a qualitative understanding of model focus, showing that the networks largely attend to tumor regions, though some false positives are present. This emphasizes the need for careful clinical interpretation and potential integration with more precise segmentation methods for clinical use.

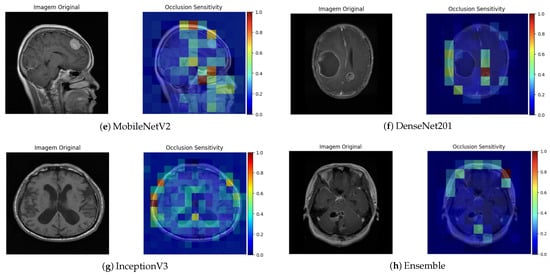

The Occlusion Sensitivity technique complements this analysis by measuring the variation in prediction confidence when different parts of the image are occluded. As shown in the figures associated with this technique (Figure 9), a significant reduction in the probability of classification was observed when the tumor region was partially hidden. This behavior indicates that the model strongly relies on that area for its decision, which supports consistency between the reasoning of the network and the relevant clinical anatomy.

Figure 9.

Occlusion Sensitivity visualization for different architectures.

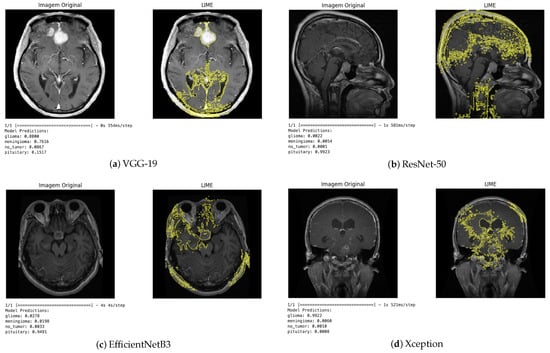

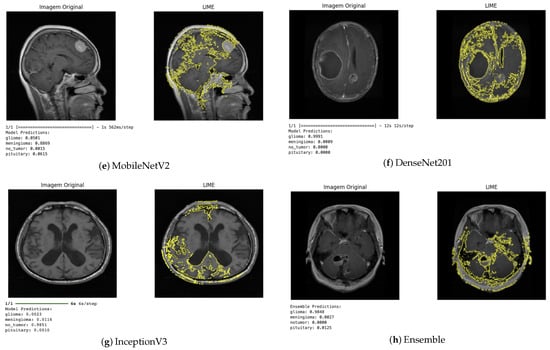

The LIME technique, in turn, provides local explanations by identifying which regions of the image contributed positively or negatively to the classification (Figure 10). This approach enabled a more detailed analysis of the influence of each image segment on the decision-making process. In general, the regions highlighted by LIME showed a high correspondence with those identified by Grad-CAM, reinforcing the consistency of the explanations produced by the different methods.

Figure 10.

LIME visualization for different architectures.

Qualitative analysis of the results obtained using the XAI techniques demonstrated that the models developed not only achieved high quantitative performance but also made decisions based on clinically relevant features. This interpretation is crucial in the medical context, as it provides visual and objective evidence that the models focus on tumor regions rather than irrelevant areas of the image.

In summary, the use of XAI techniques proved indispensable in this study by enabling a qualitative assessment of model behavior, offering insight into the consistency and robustness of the implemented models, and reinforcing their potential usefulness as diagnostic support tools. Thus, explainability contributes to the safe and responsible integration of AI systems in clinical environments, promoting more transparent, trustworthy, and patient-centered medicine.

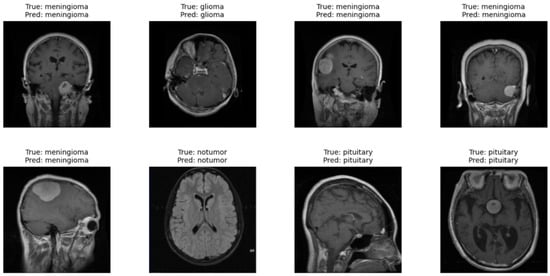

5.4. Vision Transformer

Figure 11 presents the results obtained with the Vision Transformer model applied to the test dataset. In each brain MRI image, it is possible to observe the indication of the true label (True) and the prediction of the model (Pred). The same figure shows correctly classified cases across all categories, where the model was able to identify both images of brains without tumors (no tumor) and different types of brain tumors, such as glioma, meningioma, and pituitary. This qualitative result demonstrates the ability of the ViT model to distinguish complex visual patterns in images, even when the differences between classes may be subtle. These observations complement the quantitative metrics obtained during model evaluation. The results show that the model can generalize effectively and correctly identify different conditions present in the images. Thus, qualitative analysis supports the quantitative results, reinforcing the robustness of the ViT model in the task of classifying brain tumors in magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 11.

Qualitative results of the Vision Transformer model.

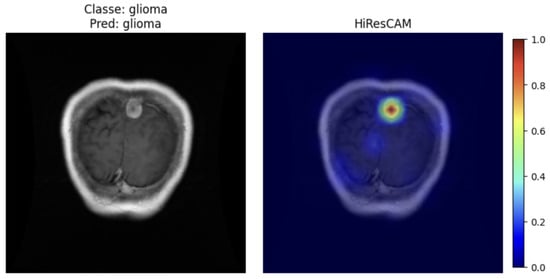

For the Vision Transformer model, the HiResCAM technique was chosen because it is more suitable for architectures of this type. Figure 12 shows the application of the HiResCAM method [47], adapted for Transformers, on a correctly classified glioma image. It can be observed that the region highlighted by the model corresponds to the tumor location: the red and yellow areas indicate regions of higher relevance assigned by the model during the tumor identification process, whereas the blue areas represent regions of lower influence.

Figure 12.

HiResCAM ViT.

6. Discussion of the Results

The comparative evaluation of the different models implemented allowed for a comprehensive analysis of the impact of DL architectures on the performance of brain tumor classification on MRI. The results obtained demonstrate that, although all CNNs exhibited satisfactory performance, there were significant differences in terms of the accuracy, robustness, and interpretability of the models.

Comparative Analysis of Model Performance

According to the metrics presented in Section 3, it was observed that the EfficientNetB3, Ensemble, and Vision Transformer models achieved the best balance between accuracy, recall, and AUROC, demonstrating a high capacity for generalization and effective classification of tumor patterns.

The EfficientNetB3, in particular, stood out due to its optimized architecture that balances depth, width, and resolution, resulting in accuracy values greater than 94%, with high recall and a low number of false negatives. This outcome confirms the efficiency of the model in recognizing subtle structural variations in brain tissue.

The ResNet-50 model also showed consistent performance, with an AUROC close to 0.98, a result that can be attributed to the use of residual connections, which mitigate the vanishing gradient problem and allow for more stable training in deep networks. Although slightly inferior to EfficientNetB3 in terms of accuracy, ResNet-50 demonstrated high sensitivity, making it particularly useful in clinical contexts where the priority is to detect all positive cases, even at the cost of some false positives.

The DenseNet201 model achieved results comparable to the previous two networks. Its dense layer connections promote feature reuse and facilitate information propagation, contributing to stable and efficient training performance.

However, models such as VGG-19 and MobileNetV2 showed lower accuracy and recall, ranging between 89% and 90%. The VGG-19, despite its architectural simplicity, exhibited reduced efficiency in detecting tumors with diffuse boundaries, possibly due to the absence of internal normalization mechanisms and skip connections. The MobileNetV2, designed for environments with limited computational resources, offered a good trade-off between performance and inference speed, making it a suitable alternative for mobile applications or hospital systems with hardware constraints.

The Xception model demonstrated performance similar to EfficientNetB3 in terms of precision, indicating the relevance of depthwise separable convolutions in extracting complex textural patterns. However, it exhibited greater variability between classes, suggesting lower robustness in distinguishing tumors with similar morphologies.

The Xception model demonstrated performance similar to EfficientNetB3 in terms of precision, indicating the relevance of depthwise separable convolutions in extracting complex textural patterns.

The InceptionV3 model maintained satisfactory performance, with accuracy around 92%, but showed a higher sensitivity to overfitting, possibly due to the high dimensionality of the data and the large number of trainable parameters.

The Ensemble model, which combined ResNet18, EfficientNetB0, and MobileNetV3, showed a slight overall improvement in performance, achieving accuracy close to 93%. The use of ensembling proved advantageous by integrating the individual strengths of different architectures, reducing variance, and increasing the reliability of the prediction. This behavior is consistent with recent literature, where ensemble models have been successfully applied in complex medical diagnosis tasks.

The ViT achieved highly promising results, with an accuracy greater than 98% and a good balance between precision and recall. The ViT demonstrated strong generalizability and robust performance in the identification of diffuse tumor regions. This effectiveness is due to its attention-based architecture, capable of capturing long-range spatial dependencies in medical images, a typical limitation of traditional CNNs.

The superior performance of ViT can be attributed to several factors. Unlike convolutional neural networks, which capture local patterns through receptive fields, ViTs leverage self-attention mechanisms that allow modeling long-range dependencies and global relationships across the entire image. This is particularly advantageous for brain MRI images, where tumor characteristics may span large spatial regions. By dividing the image into patches and embedding them linearly, the ViT can capture structural and textural patterns at multiple scales, improving its ability to discriminate between tumor classes. The ViT model benefits from deep transformer blocks with residual connections and layer normalization, which enable efficient feature extraction and representation learning without losing information across layers. With attention-based global aggregation and dropout regularization, ViTs can generalize well even with limited training data, which is often the case in medical imaging datasets. These architectural characteristics collectively explain why the ViT outperforms classical CNN architectures on this dataset.

The application of XAI techniques, namely Grad-CAM, LIME, and Occlusion Sensitivity, validated the interpretability of the models. The heatmaps generated by Grad-CAM showed that the networks consistently focused on relevant tumor regions, demonstrating clinical coherence.

LIME reinforced this evidence by identifying the areas of the image that contributed the most to the final classification, facilitating expert validation. The Occlusion Sensitivity, in turn, confirmed the robustness of the models by showing that the occlusion of tumor regions caused significant drops in prediction confidence, demonstrating the focus of the models on regions of interest.

Integration of these techniques improves the transparency of the system and its feasibility for clinical use, as it enables radiologists to understand the reasoning behind the model’s decisions, minimizing the perception of opacity often associated with DL systems.

The regions highlighted by the models were evaluated in comparison with expert knowledge and the available MRI annotations. In most cases, the heatmaps align well with the tumor boundaries, capturing the main regions of interest for classification. Occasional activations were also observed in regions outside the tumor, which likely reflect spurious correlations or limitations in slice-level labeling. These false highlights are discussed as a limitation, emphasizing the importance of careful interpretation in a clinical context.

7. Conclusions

This work demonstrated the potential of AI in automatic multi-class classification of brain tumors from magnetic resonance imaging. The implementation and evaluation of different architectures, such as VGG-19, ResNet50, EfficientNetB3, Xception, MobileNetV2, DenseNet201, InceptionV3, Ensemble and Vision Transformer, allowed performance comparison and identification of the most suitable solutions for the proposed problem.

The results obtained, with accuracy values exceeding 98% and high precision, recall, and AUROC metrics, confirm the effectiveness of the models in distinguishing between different types of tumors and healthy cases. Furthermore, the use of XAI techniques such as Grad-CAM, LIME, and Occlusion Sensitivity contributed to improving model transparency, providing qualitative insights into model behavior, and strengthening clinical confidence in diagnostic support. In the present work, the primary focus was on a qualitative interpretability analysis aimed at providing intuitive and visual insights into model behavior. Future developments will include quantitative evaluations, such as ablation studies, to further validate the interpretability results.

Among the main contributions of this work are the comparative exploration of various advanced DL architectures, the application of data augmentation and hyperparameter tuning techniques to improve robustness and generalization, and the integration of interpretability methods that bring AI closer to clinical practice.

Despite the encouraging results, some limitations were identified, such as the reliance on public datasets with potential class imbalances and the need for validation in real clinical environments. Nevertheless, this work shows that AI-based solutions can significantly reduce the time required for medical image analysis, support early diagnosis, and alleviate the workload of healthcare professionals.

Therefore, it can be concluded that the integration of AI into medical practice represents a promising path towards more efficient, preventive, and patient-centered healthcare, which should be continuously improved through future research aimed at expanding data diversity, exploring new architectures, and consolidating the clinical application of the solutions proposed here.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.F.G. and R.S.B.; methodology, E.F.G. and R.S.B.; software, E.F.G.; validation, E.F.G. and R.S.B.; formal analysis, E.F.G.; investigation, E.F.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.F.G.; writing—review and editing, E.F.G. and R.S.B.; visualization, E.F.G.; supervision, R.S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this article can be found on https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/masoudnickparvar/brain-tumor-mri-dataset (acessed on 6 November 2025). The source code will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| FCN | Fully Convolutional Network |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbours |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory Network |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| ViT | Vision Transformers |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Missaoui, R.; Hechkel, W.; Saadaoui, W.; Helali, A.; Leo, M. Advanced Deep Learning and Machine Learning Techniques for MRI Brain Tumor Analysis: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Zhou, B.; Fan, C. Automatic brain MRI tumors segmentation based on deep fusion of weak edge and context features. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, T.A.; Alam, F.B.; Hossain, M.A. Brain tumor detection, classification and segmentation by deep learning models from MRI images: Recent approaches, challenges and future directions. Array 2025, 28, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qi, G.; Mazur, N.; Yang, P.; Liu, Y. Brain tumor segmentation in MRI with multi-modality spatial information enhancement and boundary shape correction. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 153, 110553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailunaz, K.; Alhajj, S.; Özyer, T.; Rokne, J.G.; Alhajj, R. A survey on brain tumor image analysis. Med Biol. Eng. Comput. 2024, 62, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Y.M.A.; El Garouani, S.; Jellouli, I. A survey of methods for brain tumor segmentation-based MRI images. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2023, 10, 266–293. [Google Scholar]

- Rios Piedra, E.A.; Taira, R.K.; El-Saden, S.; Ellingson, B.M.; Bui, A.A.T.; Hsu, W. Assessing variability in brain tumor segmentation to improve volumetric accuracy and characterization of change. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical & Health Informatics (BHI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27 February 2016; pp. 380–383. [Google Scholar]

- Rajeyyagari, S.; Hung, B.T.; Chakrabarti, P. Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Biomedical Image Processing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Energy (ICAIS-2022), Coimbatore, India, 23–25 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, I.; Yan, J.; Abbas, Q.; Shaheed, K.; Bin Riaz, A.; Wahid, A.; Jan Khan, M.W.; Szczuko, P. Medical Image Segmentation Using Deep Semantic-based Methods: A Review of Techniques, Applications and Emerging Trends. Inf. Fusion 2023, 90, 316–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrag, A.; Gad, G.; Fadlullah, Z.M.; Fouda, M.M.; Alsabaan, M. An Explainable AI System for Medical Image Segmentation With Preserved Local Resolution: Mammogram Tumor Segmentation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 125543–125558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, D.; Bendechache, M. Unveiling the black box: A systematic review of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in medical image analysis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 24, 542–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, K.M.; Mohammed, M.A. Explainable AI and vision transformers for detection and classification of brain tumor: A comprehensive survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agneya, D.A.; Shekar, M.S.; Bharadwaj, A.; Vineeth, N.; Neelima, M.L. Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis: A Survey. BMS Coll. Eng. 2024, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Samma, H.; Bin Sama, A.S.; Hamad, Q.S. Optimized Deep Learning Model for Medical Image Diagnosis. J. Eng. Res. 2024, 13, 3147–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.R.; Asif, S.; Zhao, M.; Zou, W.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Optimized Deep Learning Model for Comprehensive Medical Image Analysis Across Multiple Modalities. Neurocomputing 2025, 619, 129182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Tat, T.B.; Hung, T.Q.; Nam, P.T.; Ngo, V.M. Evaluating Pre-processing and Deep Learning Methods in Medical Imaging: Combined Effectiveness Across Multiple Modalities. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 119, 558–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, B.M.; Popescu, N. Machine Learning Techniques for Medical Image Processing. In Proceedings of the 9th IEEE International Conference on e-Health and Bioengineering (EHB), Iasi, Romania, 18–19 November 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Fayyaz, A.M.; Abdulkadir, S.J.; Hassan, S.U.; Al-Selwi, S.M.; Sumiea, E.H.; Talib, L.F. The Role of Advanced Machine Learning in COVID-19 Medical Imaging: A Technical Review. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komura, D.; Ochi, M.; Ishikawa, S. Machine Learning Methods for Histopathological Image Analysis: Updates in 2024. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 27, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Kouno, N.; Takasawa, K.; Ishizu, K.; Akagi, Y.; Aoyama, R.; Teraya, N.; Bolatkan, A.; Shinkai, N.; et al. Comparison of Vision Transformers and Convolutional Neural Networks in Medical Image Analysis: A Systematic Review. J. Med Syst. 2024, 48, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attallah, O.; Pacal, I. Comparative evaluation of lightweight convolutional neural network and vision transformer models for multi-class brain tumor classification using merged large MRI datasets. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2025, 269, 105609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidoc. AI Solutions for Radiology. 2023. Available online: https://www.aidoc.com (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Health, G. Health Solutions. 2023. Available online: https://health.google (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- PathAI. AI-Powered Pathology Solutions. 2023. Available online: https://www.pathai.com (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Viz.ai. Viz 3D CTATM. 2024. Available online: https://www.viz.ai/large-vessel-occlusion (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Tempus. Tempus Pixel Lung. 2024. Available online: https://www.tempus.com/radiology/tempus-pixel-lung/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Qure.ai. Qure.ai. 2025. Available online: https://www.qure.ai (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Lunit. AI-powered Cancer Screening and Treatment Solutions. 2025. Available online: https://www.lunit.io/en (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Orvile. Annotated Ultrasound Liver Images Dataset. 2022. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/orvile/annotated-ultrasound-liver-images-dataset (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Orvile. Human Bone Fractures Image Dataset (HBFMID). 2023. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/orvile/human-bone-fractures-image-dataset-hbfmid (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Oza, P.; Oza, U.; Oza, R.; Sharma, P.; Patel, S.; Kumar, P.; Gohel, B. Digital Mammography Dataset for Breast Cancer Diagnosis Research (DMID)—Breast Cancer Mammography Dataset. 2023. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/orvile/dmid-breast-cancer-mammography-dataset?select=ROI+Masks (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- González, J.L. Tumores Cerebrales—MRI Dataset. 2023. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/gonzajl/tumores-cerebrales-mri-dataset (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Mooney, P. Chest X-Ray Images (Pneumonia) Dataset. 2018. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/paultimothymooney/chest-xray-pneumonia (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Heller, N.; Sathianathen, N.; Kalapara, A.; Walczak, E.; Moore, K.; Kaluzniak, H.; Rosenberg, J.; Blake, P.; Rengel, Z.; Oestreich, M.; et al. KiTS19-Kidney Tumor Segmentation Challenge Dataset. 2019. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/orvile/kits19-png-zipped (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Tschandl, P.; Rosendahl, C.; Kittler, H. HAM10000: Human Against Machine with 10,000 Training Images—A Large Collection of Multi-Source Dermatoscopic Images of Pigmented Skin Lesions. 2018. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kmader/skin-cancer-mnist-ham10000 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Soares, E.; Angelov, P.; Biaso, S.; Fróes, M.H.; Abe, D.K. SARS-CoV-2 CT-Scan Dataset: A Large Dataset of Real Patients CT Scans for SARS-CoV-2 Identification. 2020. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/plameneduardo/sarscov2-ctscan-dataset (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Andrew-MVD. DRIVE—Digital Retinal Images for Vessel Extraction. 2020. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/andrewmvd/drive-digital-retinal-images-for-vessel-extraction (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Daithal, N. ImageOASIS Dataset. 2021. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ninadaithal/imagesoasis (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Khan, S.H.; Naseer, M.; Hayat, M.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, F.S.; Shah, M. Transformers in Vision: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 200:1–200:41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.; Soto-Rey, I.; Kramer, F. Towards a guideline for evaluation metrics in medical image segmentation. BMC Res. Notes 2022, 15, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Agrawal, R. Unmasking VGG16: LIME Visualizations for Brain Tumor Diagnosis. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computer Vision and Machine Intelligence (CVMI), Prayagraj, India, 19–20 October 2024; pp. 979–987. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2020, 128, 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Barua, P.; Rahman, M.; Ahammed, T.; Akter, L.; Uddin, J. Transfer learning architectures with fine-tuning for brain tumor classification using magnetic resonance imaging. Healthc. Anal. 2023, 4, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickparvar, M. Brain Tumor MRI Dataset. 2024. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/masoudnickparvar/brain-tumor-mri-dataset?select=Training (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Chollet, F. Deep Learning with Python; Manning Publications: Shelter Island, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hesterberg, T.C. Bootstrap. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2011, 3, 497–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draelos, R.L.; Carin, L. Use HIRE-SCAM instead of Grad-CAM for faithful explanations of convolutional neural networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.08891. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.