Abstract

Background: Strength and the strength–power continuum may increase athletic performance, although data are scarce regarding the effects of long-term periodized training on the athletic performance of adolescent track and field athletes. The purpose of this study was to investigate performance modifications following 8 weeks of strength and strength–power resistance training, focusing on the athletic performance of adolescent track and field athletes. Methods: Following an equivalent single-arm pre–post intervention design, 16 adolescent athletes (age: 16.3 ± 0.5 years; mass: 56.5 ± 10.4 kg; height: 1.67 ± 0.07 m) participated in the study. Athletes followed an 8-week periodized resistance training program aiming to increase strength and strength–power. Measurements were performed before (T1), at the middle (T2) and at the end of the training period (T3) and included the standing long jump, single-leg standing long jump, five-step long jump, seated medicine ball throw, 0–80 m sprint and 1RM in the bench press and parallel squat. Results: The standing long jump (F(2,14) = 109.564; η2 = 0.940; p = 0.001), single-leg long jump (F(2,14) > 41.801; η2 = 0.857; p = 0.001) and five-step long jump (F(2,14) = 148.564; η2 = 0.955; p = 0.001) improved significantly from T1 to T2 (p < 0.001) and from T2 to T3 (p < 0.001). The seated medicine ball throw (F(2,14) = 124.305; η2 = 0.947; p = 0.001) and sprinting performance (F(2,14) = 51.581; η2 = 0.828; p = 0.001) were significantly enhanced from T1 to T2 (p < 0.001) and from T2 to T3 (p < 0.001). The 1RM in the bench press (F(2,14) = 36.280; η2 = 0.838, p = 0.001) and in the parallel squat (F(2,14) = 48.165; η2 = 0.873, p = 0.001) increased significantly from T1 to T2 (p < 0.001) and from T2 to T3 (p < 0.01). Conclusions: Strength and the strength–power continuum appear to have a positive effect on the physical fitness of adolescent track and field athletes, which highlights the importance of strength-based resistance training programs in adolescent athletes.

1. Introduction

The year-round training of track and field athletes is designed according to the theory of periodization [1]. Periodization divides the annual training plan into smaller training periods (preparation, pre-competition, competition and transition) with different training goals (e.g., enhance endurance strength, maximum strength or strength–power) [2,3,4]. It is evident that athletes from all track and field events, including sprinters, jumpers, throwers and distance runners, spend a large part of their training on strength and strength–power resistance training, aiming to enhance power and athletic performance [5,6]. Indeed, a common training strategy, especially in designing resistance training programs, is the continuum of strength and strength–power resistance training [7,8]. However, the performance modifications following such training programs, especially in adolescent athletes, have not been clarified. This knowledge may enable coaches and strength and conditioning professionals to design more sophisticated resistance training programs and potentially enhance athletic performance in adolescent track and field athletes.

The continuum of strength and strength–power resistance training [9,10] may lead to significant increases in athletic performance in track and field athletes. Results from the classic study of Stone et al. [11] showed that 8 weeks of strength–power training not only enhanced throwing performance (approximately 5.5%) but also improved several physical attributes, such as muscle strength, the rate of force development (RFD) and the isometric peak force. Interestingly, greater percentage increases in power and RFD were found following the strength training phase, while the power training program induced greater percentage increases in isometric force. Studies in track and field athletes have shown significant increases after strength and power training in power, RFD, strength and track and field competitive performance [6,12]. However, data are scarce regarding the effects of strength and the strength–power continuum in adolescent track and field athletes. This gap is probably due to the poor resistance training experience of adolescent athletes or to the inability to recruit a sufficient number of athletes to a demanding long-term training study.

Adolescent athletes face injury risks from early specialization and excessive training exposure in sports [13]. According to the guidelines on long-term athletic development, adolescent athletes should follow integrative neuromuscular training, including strength–power training, sport-specific skills development and mobility, balance and flexibility training programs in an attempt to reduce the risk of injury and enhance performance [14,15]. In line with these guidelines, a well-organized training program designed in line with the principles of periodization and managing the training load according to each training phase [16] does not only promote the athletic performance of adolescent athletes but protects them from injuries as well. Indeed, in a recent study, a highly structured training program is proposed for adolescent athletes, which should be used frequently in order to enhance athletic performance [17,18]. Furthermore, a study on track and field athletes showed that block periodization models may provide greater benefits in athletic performance compared to non-linear models [12]. Block periodization includes the continuum of strength and strength–power in resistance training. However, whether the strength and strength–power continuum can induce positive performance modifications in adolescent athletes needs further investigation.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of 8 weeks of strength and strength–power resistance training on athletic performance in adolescent track and field athletes. Moreover, the secondary purpose of the study was to examine whether strength–power training may induce greater percentage increases in athletic performance. The hypothesis of the study was that strength training would induce positive changes in the athletic performance of the athletes, while strength–power training would induce greater percentage increases in athletic performance than strength training.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

An equivalent single-arm pre–post intervention study design was followed. Sixteen adolescent track and field athletes served as the single group of athletes for the investigation of the possible modifications in athletic performance following strength and strength–power continuum training. Specifically, all athletes served as their own controls across the 8-week training period, and no control group was used in the study.

2.2. Participants

Sixteen adolescent track and field athletes participated in the study. Athletes were further divided into 11 females [age: 16.2 ± 0.3 years (age ranged from 16 to 17 years); body mass: 52.7 ± 8.1 kg; body height: 1.65 ± 0.06 m] and 5 males [age: 16.4 ± 0.5 (age ranged from 16 to 17 years); body mass: 64.7 ± 10.6 kg; body height: 1.71 ± 0.07 m]. Athletes had 5.7 ± 1.74 years of training experience and 1.5 ± 0.6 years of resistance training experience combining body mass exercises, structural multi-joint exercises and weightlifting derivatives such as the bench press, the squat, the power clean and the power snatch. Athletes were sprinters (100–200 m; 2 males), jumpers (long jump: 4 females and high jump: 2 females) and short-distance runners (800–1500: 5 females and 3000 m: 3 males). Moreover, the biological age of the athletes was 15.6 ± 0.5 years, which remained unchanged throughout the 8-week training period [19]. Prior to entering the study, all athletes and their parents were informed about the experimental procedure and signed an informed consent form. The criteria for participation were (a) the absence of any cardiovascular and musculoskeletal health problems, (b) having competed in the last local competition, (c) having completed 90% of the resistance training intervention and 80% of their individual sport-specific training programs, (d) having completed all measurements and wellness questionnaire reports and (e) specializing only in their track and field event. All procedures were in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2000 and were approved by the local university ethics committee (ΔΠΘ/ΕHΔΕ/62770/540; 22/05/2025).

2.3. Procedures

Measurements were performed during the spring preparation phase. All athletes completed the winter preparation phase and participated in indoor competitions, as well as in two local outdoor competitions. Measurements had a duration of three non-consecutive days and were performed in the track and field training facilities. Specifically, during the first day, the horizontal jumps were performed, including the standing long jump, the standing single-leg long jump and the 5-step long jump, while a maximum of 0–80 m sprints was performed. During the second day, the upper-body power was measured with the seated medicine ball throw test. During the third day, three to five maximum repetitions in the bench press and parallel squat were evaluated, and then the calculation of the one-repetition maximum (1RM) was performed. All measurements were performed three times during the experimental period: at the beginning (T1), following the strength mesocycle (T2) and at the end of the strength–power mesocycle (T3). Measurements were performed in the same order at the three measurement points. In addition, during the strength and strength–power training sessions, a wellness report questionnaire was provided by athletes as an index of the internal training load [20].

2.4. Training

Training was designed according to the principles of periodization [4] and followed the guidelines on long-term athletic development for adolescent athletes [14,15,18]. Specifically, a traditional periodization model was used, while the 8-week training program was further separated into two phases with different training goals: (a) the strength phase (last phase of the specific training period), which aimed to increase the training volume and strength, and (b) the strength–power phase (beginning of the pre-competition phase), which aimed to progressively decrease the training volume, increase the training intensity and enhance power development [9]. Although the athletes came from different sports, the 8-week resistance training program was the same for all. Table 1 presents the actual resistance training program and the general training instructions for each individual sport specialization. For the strength training program, athletes performed 2 training sessions per week, which included both single-joint and multi-joint exercises, as well as core and mobility exercises. Especially for the multi-joint resistance exercises, athletes were instructed to perform the recommended repetitions while the load was set to meet the prescribed repetitions. Increases in loading were performed when necessary to meet the targeted repetition scheme. The core training program included dynamic exercises focusing on the lateral aspects of the core [21], while mobility exercises focused on the whole body but mainly on the hip joint [22]. The strength–power training mesocycle was designed with a complex pair of exercises [23,24]. Two complexes were used during Tuesday and Thursday. For example, on Tuesday, the 4 repetitions of the parallel squat were followed by 4 vertical jumps above hurdles. During this period of training, athletes were instructed to perform all complex exercises with the maximum intentional movement velocity [25]. In addition, training during Saturdays had a more playful nature, with easy and fun exercises aimed at developing mobility, balance and general flexibility. However, the last Saturday of each mesocycle included a local competition where athletes participated as part of their training. All training sessions were supervised by a certified strength and conditioning professional.

Table 1.

General training program followed by athletes during the 8-week training period. The specific strength and strength–power resistance training program is presented for Tuesday and Thursday.

2.5. Subjective Wellness Questionnaire

Thirty minutes prior to each strength and strength–power resistance training session, athletes completed a six-item subjective wellness report on a 1–5 Likert scale, where 1 was the worst response and 5 the best response. All individual responses were collected in printed form at the beginning of training, while a member of the research team collected all forms for statistical analysis. Specifically, the subjective wellness report included responses for the mood state (1—highly annoyed, irritable, down; 5—very positive mood), sleep quality (1—hardly slept at all; 5—had a great sleep, feeling refreshed), energy levels (1—very lethargic, no energy at all; 5—full of energy), muscle soreness (1—extremely sore; 5—not sore at all), diet yesterday (1—all meals high in sugar, processed foods, no fruit and vegetables; 5—ate really well, no added sugar or processed foods and lots of vegetables and some fruit) and stress (1—highly stressed; 5—very relaxed) [20,26,27]. All athletes were familiarized with the wellness report two weeks before the initiation of the experimental procedure. Moreover, the total wellness score was calculated by summing the responses to the six items, with higher scores indicating a better-perceived wellness state [20].

2.6. Anthropometric Characteristics

During the morning hours of the first day, anthropometric characteristics (body mass and body height) were measured with a portable body mass scale (Tanita BC-545N, Amsterdam, Netherlands), which measured with accuracy of 0.1 kg, and a stadiometer (Seca, 206, Hamburg, Germany), which measured with 0.1 cm precision. All measurements were performed two times, and the mean value was used for the statistics. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for body mass was 0.99 (95% confidence interval (CI): lower = 0.97, upper = 0.99) and that for body height was 0.99 (95%CI: lower = 0.96, upper = 0.99).

2.7. Horizontal Jump and 0–80 Sprint

Later, during the noon hours of the first day, athletes performed the horizontal jump tests and the 0–80 maximum linear sprint. During all measurements, the weather was calm, with an ambient temperature of approximately 21–25 °C. Measurements began with the horizontal jumps. Following a standardized warm-up including 10 min of running and both static and dynamic stretching, athletes started with the standing long jump. Athletes placed their feet on the wooden long-jump vault and, with hands swinging, jumped as far as they could, landing on both legs in the sand pit. Athletes were instructed to push off as fast as they could [28]. Flags were used as individual marks to motivate athletes to jump further. Three maximum attempts were allowed with 1 min rest, and the best was used for the statistics. Following the standing long jump, athletes performed the single-leg standing long jump [29]. Similarly, athletes stood on one leg and, with arms swinging, pushed as far as possible and landed with both legs on the sand pit. Two maximum attempts with 1 min rest were given to all athletes, and the best was recorded for statistical analysis. The last horizontal jump was the 5-step long jump. Specifically, athletes started with both legs parallel and then started jumping from one leg to the other, covering as much distance as they could. The 5th step was the landing in the sand pit with both legs. Three maximum attempts were allowed with 2 min rest, and the best was used for the statistics. During all horizontal jumps, athletes wore track and field spike shoes. Moreover, together with the flags in the sand pit, verbal feedback was also provided to athletes to motivate them towards higher jumping performance. The ICCs for the standing long jump, single-leg long jump and 5-step long jump were 0.96 (95%CI lower = 0.78, upper = 0.96), 0.87 (95%CI lower = 0.75, upper = 0.95) and 0.90 (95%CI lower = 0.83, upper = 0.97), respectively.

Ten minutes after the horizontal jump tests, athletes performed 2 maximum 0–80 m sprint time trials. Briefly, athletes performed an additional warm-up including 2–4 skipping exercises and 2–3 submaximal sprints. Then, 2 maximum 0–80 m sprints were performed. All time sprints were performed from a standing position while athletes started 50 cm behind the first photocell. Three photocell gates (Witty, Microgate, Bolzano, Italy) were used to measure the acceleration phase (0–20 m), the maximum speed phase (20–80 m) and the total distance (0–80 m) [30]. Athletes received feedback on their total time trial performance. The ICC for the 0–80 m sprint was 0.94 (95%CI lower = 0.76, upper = 0.98).

2.8. Seated Medicine Ball Throw

During the second day of measurements, the upper-body power was evaluated via the seated medicine ball throw test. Five different medicine balls were used: 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 kg. All throws were performed randomly to minimize learning and post-activation performance enhancement effects [31]. Following the standardized warm-up, athletes were seated on the floor of the gym with their backs touching the wall and their legs apart. From this position, athletes performed 2 warm-up throws (with a 2 kg medicine ball for females and a 3 kg medicine ball for males) and then performed the maximum throws with all medicine balls. The distance was measured with a metallic measuring tape to the nearest cm, starting from the wall to the point where the medicine ball landed on the floor. Two maximum throws with 1 min rest between attempts were given to athletes with each medicine ball, and the best performance was used for the statistics. During all throws, feedback was provided to athletes to motivate them towards higher performance. Following the measurements, the mean value of all throws was calculated as an upper-body power index. The ICC for the seated medicine ball throws was 0.96 (95%CI: lower = 0.90, upper = 0.98).

2.9. Maximum Strength

During the third day, athletes reported to their track and field gym facilities for the 1RM measurements in the bench press and the parallel squat. The bench press was the first exercise. Briefly, after the standard warm-up procedure, athletes began a specific warm-up with an empty barbell (15 kg) and the load was progressively increased until they performed 3–5 repetitions to failure [32]. Then, the equations of Mayhew et al. [33] for the bench press and Wathan et al. [34] for the parallel squat were used to calculate the 1RM [35]. Fifteen minutes after the bench press, the parallel squat was performed. Specifically, a hurdle was used to determine the individual depth of the squat where the thighs were parallel to the ground. Similarly to the bench press, a warm-up with an empty barbell was allowed, and then the loads were increased until 3–5 maximum repetitions were achieved. During all efforts, one researcher monitored the technique and vocally encouraged athletes to ensure their best efforts. Criteria for a successful attempt were (a) complete with proper technique across all 3–5 repetitions; failure was determined by (b) loss of technique or failure to complete one of the repetitions. The ICCs for the bench press and parallel squat were 0.97 (95%CI: lower = 0.91, upper = 0.98) and 0.87 (95%CI: lower = 0.91, upper = 0.97), respectively.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation. All ANOVA assumptions were met. Data were normally distributed according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and no violations of sphericity were observed according to Mauchly’s test [36,37]. A one-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni adjustment was used to investigate differences between T1, T2 and T3 measurements. Moreover, η2 was calculated for the ANOVA. In addition, a paired-samples T-test was used to investigate the differences between subjective wellness and percentage differences between T1–T2 and T2–T3. Hedges g effect size was also calculated, and the interpretation was performed according to the following ranking: <0.2 (trivial), 0.2–0.5 (small), 0.5–0.8 (moderate) and >0.8 (large). An a priori sample calculation was performed (given effect size f = 0.40, a err prob = 0.05, power = 0.95), and a total sample size of 15 participants was required to detect statistically meaningful effects [38]. Reliability for all measurements was assessed using a two-way random effect ICC with 95%CI. All data were analyzed with SPSS-30, while the significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

All athletes completed the training period without injuries. In addition, athletes were consistent in strength and strength–power training sessions and completed all 16 training sessions. Moreover, no significant difference was found in the percentage change in performance between male and female athletes. For example, no significant difference was found for mean performance in the seated medicine ball throw (males: 13.7 ± 1.8% vs. females: 12.4 ± 8.3%; p = 0.612; g = 0.183; trivial), the standing long jump (males: 13.3 ± 5.3% vs. females: 14.1 ± 5.3%; p = 0.789; g = 0.142; trivial), the 0–80 m linear sprint (males: −6.8 ± 2.2% vs. females: −6.6 ± 2.9%; p = 0.874; g = 0.074; trivial) and the 1RM strength in the bench press (males: 23.8 ± 20.9% vs. females: 33.6 ± 13.9%; p = 0.283; g = 0.569; moderate) and parallel squat (males: 42.8 ± 11.7% vs. females: 40.6 ± 19.2%; p = 0.811; g = 0.124; trivial). Therefore, the results are presented as one group [6,9].

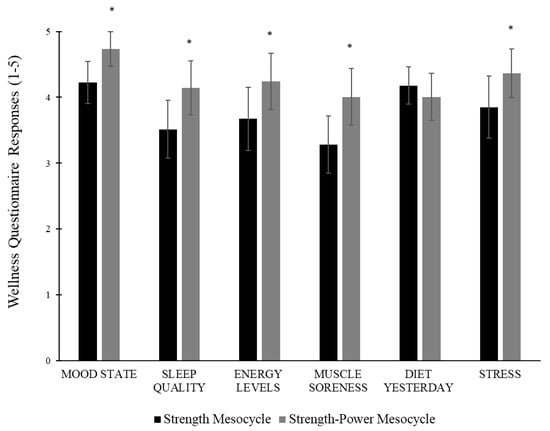

All athletes responded to all wellness questionnaires throughout the 8-week training program. Figure 1 presents the average values of the 4-week strength and strength–power mesocycles. Significant differences were found for mood state (t = −5.586; p = 0.001; g = −1.325; large), sleep quality (t = −4.502; p = 0.001; g = −1.068; large), energy levels (t = −3.534; p = 0.003; g = −0.839; large), muscle soreness (t = −7.199; p = 0.001; g = −1.708; large) and stress (t = −5.154; p = 0.001; g = −1.223; large). No significant difference was found for diet yesterday (t = 1.381; p = 0.187; g = 0.328; small). Additionally, the total score for the wellness reports showed a statistically significant difference between the strength and strength–power training periods (strength: 22.7 ± 1.7 AU vs. strength–power: 25.5 ± 1.7 AU; p = 0.001; g = −1.285; large).

Figure 1.

Changes in wellness questionnaire variables during strength and strength–power mesocycles. * = significant difference between strength and strength–power mesocycles.

Body mass remained unchanged following the 8-week training period (T1: 56.5 ± 10.4 kg vs. T2: 56.7 ± 10.3 kg, t = −1.379; p = 0.195; g = −0.322; small), while a similar result was found for body height (T1: 167.2 ± 0.7 cm vs. T2: 167.2 ± 0.7 cm; t = 1.000; p = 0.333; g = 0.237; small). Significant increases were found for all horizontal jump tests from T1 to T2 measurements and from T2 to T3. Although similar results were observed for the 0–80 m linear sprint, no significant difference was found for 20–80 m between T2 and T3 measurements (p = 0.986). Table 2 presents the increases in horizontal jumps and the sprint time trial.

Table 2.

Changes in horizontal jumps and linear sprint following the 8-week training program.

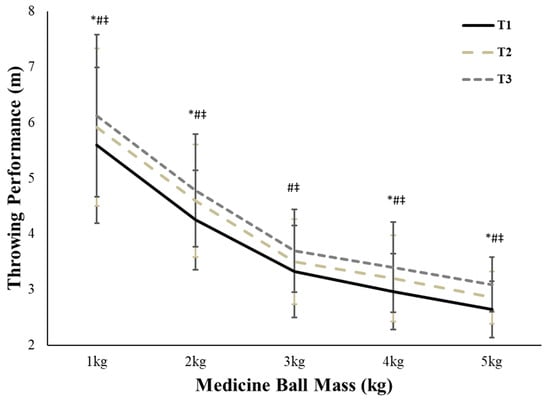

Increases in the seated medicine ball throw are presented in Figure 2. Overall, performance significantly increased from T1 to T2 and from T2 to T3 for almost all medicine balls. Specifically, the seated medicine ball throw with the 1 kg ball was significantly improved (F(2,14) = 31.576; η2 = 0.819; p = 0.001) from T1: 5.59 ± 1.40 m to T2: 5.91 ± 1.42 m and to T3: 6.13 ± 1.46 m. Performance with the 2 kg medicine ball was significantly increased (F(2,14) = 30.696; η2 = 0.814; p = 0.001) from T1: 4.25 ± 0.89 m to T2: 4.59 ± 1.01 m and to T3: 4.78 ± 1.01 m. Similarly, the seated medicine ball throw with the 3 kg ball was significantly improved (F(2,14) = 35.501; η2 = 0.835; p = 0.001), albeit not from T1: 3.32 ± 0.83 m to T2: 3.50 ± 0.76 m (p = 0.530) but from T2 to T3: 3.70 ± 0.74 m. Additionally, performance with the 4 kg medicine ball was significantly increased (F(2,14) = 32.276; η2 = 0.822; p = 0.001) from T1: 2.96 ± 0.68 m to T2: 3.20 ± 0.76 m and to T3: 3.40 ± 0.81 m. Lastly, the seated medicine ball throw with the 5 kg ball was significantly improved (F(2,14) = 40.649; η2 = 0.853; p = 0.001) from T1: 2.64 ± 0.51 m to T2: 2.85 ± 0.47 m and to T3: 3.09 ± 0.49 m.

Figure 2.

Increases in seated medicine ball throws following the 8-week training period. * = significant difference between T1 and T2, # = significant difference between T2 and T3, ‡ = significant difference between T1 and T3.

Moreover, when the seated medicine ball throws were combined into one variable (the mean medicine ball throwing performance), a significant increase was found (F(2,14) = 124.305; η2 = 0.947; p = 0.001) from T1: 3.75 ± 0.81 m to T2: 4.01 ± 0.87 m and to T3: 4.22 ± 0.87 m. The maximum strength increased significantly for both the bench press (F(2,14) = 36.280; η2 = 0.838, p = 0.001) and parallel squat (F(2,14) = 48.165; η2 = 0.873, p = 0.001). Specifically, the bench press 1RM increased significantly from T1 to T2 (T1: 37.5 ± 16.1 kg to T2: 44.9 ± 16.2 kg, p = 0.001) and from T2 to T3 (T2: 44.9 ± 16.2 kg to T3: 47.6 ± 15.7 kg, p = 0.001). A total increase of 30.6 ±16.4% was found from T1 to T3. Similarly, the 1RM in the parallel squat increased significantly from T1 to T2 (T1: 43.7 ± 9.9 kg to T2: 53.2 ± 10.2 kg, p = 0.001) and from T2 to T3 (T2: 53.2 ± 10.2 kg to T3: 61.1 ± 12.5 kg, p = 0.001). A total increase of 41.3 ±16.8% was found from T1 to T3.

Table 3 presents the percentage changes in performance for the horizontal jumps, sprint, strength and throwing. The upper-body strength 1RM was mainly increased following the strength mesocycle, while smaller increases were found following the strength–power mesocycle. In contrast, the lower-body 1RM strength percentage increase was similar for both training mesocycles. Likewise, the percentage increase in seated medicine ball throwing performance for all medicine balls was similar following the strength and strength–power mesocycles. The percentage changes in the standing and single-leg long jumps were the same between the strength and strength–power mesocycles; however, the five-step long jump was mainly enhanced following the strength mesocycle compared to the strength–power mesocycle. The percentage change in sprinting in the acceleration phase was similar following both training mesocycles, but the strength mesocycle induced greater percentage enhancements in the maintenance phase of speed and in the total time.

Table 3.

Percentage changes following strength (T1–T2) and strength–power (T2–T3) mesocycles.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the possible effects of 8-week strength and strength–power training on the physical fitness and performance of adolescent track and field athletes. Moreover, it sought to explore the possible differences in training-induced adaptations between strength and strength–power training mesocycles. The main finding of the study was that athletic performance, as measured in the current study through horizontal jumping ability, sprint, medicine ball throws and 1RM strength, was significantly enhanced following the strength mesocycle, while the strength–power mesocycle induced further increases in all variables. However, the strength–power mesocycle induced smaller performance modifications compared to the strength mesocycle, although athletes reported higher subjective wellness scores during the strength–power mesocycle. The results of the current study suggest that strength training is a vital component of athletic conditioning in adolescent track and field athletes, and coaches may consider including strength training programs in their periodized training plans. In addition, strength–power training seems to continue the rate of adaptation and may improve athletic performance. Moreover, strength–power training may lead to significant enhancements in the subjective wellness of athletes; consequently, this may explain the further increases in athletic performance.

Strength training is an important parameter for the enhancement of all physical abilities in young and adolescent athletes [17,39]. Therefore, when designing periodized training programs for adolescent athletes, strength training should be a priority in order to create the foundation for strength–power training [7]. Strength training induced significantly greater percentage increases in the 1RM bench press, five-step long jump and 0–80 m sprinting time trial compared to strength–power training. These results demonstrate the importance of including strength training programs in adolescent athletes [15]. However, strength–power training induced similar increases in the 1RM parallel squat, upper-body power (medicine ball throws), standing long jumps and the acceleration phase (0–20 m) compared to strength training. A previous study has shown that strength and power ballistic training may induce similar increases in athletic performance but with different muscular adaptations [40]. Specifically, strength training may lead to significant increases in strength and hypertrophy and a reduction in the percentage of type IIx muscle fibers [41], with a subsequent increase in athletic performance. However, strength–power training may increase strength and the velocity of movement and maintain the percentage of type IIx muscle fibers, leading therefore to increases in muscle power [40,42]. In addition, when power development is the main goal of training, strength–power resistance training may be used [43]. Training studies in collegiate throwers, young track and field throwers and well-trained throwers showed that, when strength–power training followed strength training, significant increases were found in peak force, RFD and muscle architecture characteristics [4,25]. Therefore, it would be reasonable to assume that these changes were also present in the current study, leading to the conclusion that a periodized training program including strength and the strength–power continuum may induce positive modifications in athletic performance in adolescent track and field athletes. Nevertheless, both technical learning and maturation may affect the results of the strength and strength–power training program regarding the physical fitness of adolescent athletes.

The subjective wellness report analysis showed significantly higher responses following the strength–power training mesocycle compared to the strength mesocycle. The inclusion of complex training with pairs of strength and power–plyometric–ballistic exercises (including weightlifting derivatives) [16] may have caused greater training variety in resistance training, which in turn may have led to higher anticipation and excitement for training in athletes. These positive changes in subjective wellness among athletes during strength–power training also suggest that the wellness questionnaire may be a feasible training strategy to monitor changes in athletic performance; at the same time, it may be an effective physiological marker of fatigue. Indeed, a previous study on Australian football players showed that regular monitoring of subjective wellness may allow coaches to increase the training load during a mesocycle of training [26].

Muscle strength was significantly increased across the entire training period, by 30.6 ± 16.4% in the bench press and by 41.3 ± 16.8% in the parallel squat. These large percentage increases in the 1RM were expected since the athletes in the current study were adolescents with relatively low initial strength levels and resistance training experience. Another possible explanation is the application of a periodized training program, which seems to favor increases in strength and performance in track and field athletes [12,44]. Similar increases in 1RM strength were found in a previous study in the bench press (22%) and almost in the squat (28%) following 14 weeks of resistance training in 17 male physical education students [41]. In addition, long-term strength training with and without weightlifting derivatives increased isometric midthigh pulls approximately by 27.95 ± 22.95% and 20.66 ± 18.71%, respectively, in youth students with similar training experience to the athletes in the current study [16]. In contrast, a study on well-trained young track and field throwers showed significant but smaller increases in the back squat (4.68 ± 2.98%), although these athletes had a higher initial level of strength compared to the adolescent athletes in the current study [6]. Periodized resistance training may lead to significant enhancements in muscle strength; coaches therefore may apply two training sessions per week, focusing on upper- and lower-body exercises, to enhance the muscle strength of adolescent track and field athletes. Moreover, complex training may be used as a strength–power training method since it might induce further increases in athletic performance [23,24]. Indeed, strength–power training seems to induce similar increases in seated medicine ball throws to a strength training mesocycle. Figure 2 presents the increases in medicine ball throws, forming a force–velocity curve. When the strength–power training mesocycle was applied, the force–velocity curve shifted to the right and above the T2 and T1 curves, which highlights the increases in upper-body muscle power [43]. Similarly to this finding, a previous study on well-trained throwers showed increases in the force–velocity curve only in low-mass medicine balls (1 kg, 2 kg and 3 kg) following 20 weeks of periodized training [31]. Coaches may use this effective, low-cost and easy-to-use performance test as an index of training-induced adaptations in upper-body muscle power.

Similarly to the upper-body muscle power, the lower-body muscle power, measured here with horizontal jumps, increased following the 8-week training period. Specifically, performance modifications in the standing long jump, both bilateral and unilateral, were positive following the strength and strength–power mesocycles, while the five-step long jump seemed to be improved to a greater extent after the strength compared to the strength–power mesocycle. For track and field athletes, horizontal jumps are essential exercises, mainly due to their strong correlations with running and throwing performance [31,45]. In addition to these findings, the time trial in 0–80 m was significantly decreased, and the acceleration phase (0–20 m) was also decreased, following the 8-week training program. These results may be explained by the possible increases in strength, in neuromuscular adaptations and in the increases in the vastus lateralis fascicle length following the strength–power training program [46,47]. It can be hypothesized that strength and the strength–power continuum may induce significant increases in fascicle length, which in turn may have led to an enhanced RFD, strength, sprints and overall performance [6]. Moreover, the changes in horizontal jumps might be explained by the frequent application of long-jump exercises during the training program, which could not be avoided and may have impacted the athletes’ performance.

Although the results of the study are promising for adolescent track and field athletes, there are some limitations that should be mentioned. The small sample size (which might affect the power of the results), the different sport-specific training and the coexistence of both female and male athletes may limit the generalization of the results to higher-level athletes. Another limitation is the lack of a control group. However, for ethical reasons, it was not possible to exclude an adolescent athlete from the training program. Moreover, the lack of physiological measurements like electromyography, muscle ultrasound or body composition analysis may have led to the omission of useful information about the possible training-induced modifications following the 8-week training program. However, a strength of this study was the periodized training program, which may have led to significant increases in athletic performance. More studies are needed to understand the rate of adaptation following strength and strength–power continuum training in different physical fitness domains among adolescent track and field athletes. Moreover, future studies with athletes from the same sport, of a similar age and the same sex, might provide useful information about the impacts of strength and strength–power training on physical fitness.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, 8 weeks of strength and strength–power periodized resistance training may be associated with positive modifications in the physical fitness components of adolescent track and field athletes. Changes in performance seemed to be higher during strength training, although strength–power training added significant increases in performance with higher subjective wellness. Therefore, coaches may apply the strength and strength–power continuum effectively in adolescent track and field athletes as it appears to enhance athletic performance. In addition, the training program used in the current study had a positive impact on the athletic performance of adolescent athletes. Strength training in adolescent track and field athletes is crucial for their long-term athletic development. The continuum of strength and strength–power training exhibits potential benefits in strength, upper- and lower-body power and linear sprints. Therefore, it is suggested to apply two training sessions per week, including the complex method with two pairs of exercises for both the upper and lower body, which may enhance the athletic performance of adolescent athletes. Additionally, track and field athletes may benefit from different training programs and various resistance training methods, which might affect their subjective wellness prior to training and competitions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D., N.Z., A.A., P.F.F. and A.C.; Investigation, A.D. and A.K.; Methodology, A.D., N.Z., S.M., P.F.F., I.S. and M.H.; Resources, N.Z., A.A., P.F.F., I.S. and A.C.; Formal analysis, N.Z. and S.M.; Writing—original draft, A.D., N.Z., A.K., P.F.F., S.M. and M.H.; Writing—review and editing, A.D., N.Z., A.A., P.F.F., I.S. and A.C.; Supervision, N.Z., A.A. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Democritus University of Thrace (protocol code ΔΠΘ/ΕHΔΕ/62770/540; 22/05/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, as well as from all parents and legal guardians.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author (N.Z.) following reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the athletes who participated in the study and to Pagxiakos G.S. for hosting all experimental procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 1RM | One-repetition maximum |

| RFD | Rate of force development |

| Med-Ball | Medicine ball |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| reps | Repetitions |

References

- DeWeese, B.H.; Hornsby, G.; Stone, M.; Stone, M.H. The training process: Planning for strength–power training in track and field. Part 1: Theoretical aspects. J. Sport Health Sci. 2015, 4, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWeese, B.H.; Hornsby, G.; Stone, M.; Stone, M.H. The training process: Planning for strength–power training in track and field. Part 2: Practical and applied aspects. J. Sport Health Sci. 2015, 4, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazis, T.; Methenitis, S.; Zaras, N.; Stasinaki, A.-N.; Karampatsos, G.; Georgiadis, G.; Terzis, G. Effects of complex vs. compound training on competitive throwing performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 9, 1510–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.H.; Hornsby, W.G.; Haff, G.G.; Fry, A.C.; Suarez, D.G.; Liu, J.; Gonzalez-Rave, J.M.; Pierce, K.C. Periodization and block periodization in sports: Emphasis on strength-power training—A provocative and challenging narrative. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 2351–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, T.; Sandbakk, Ø.; Enoksen, E.; Seiler, S.; Tønnessen, T. Crossing the Golden Training Divide: The Science and Practice of Training World-Class 800- and 1500-m Runners. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 1835–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaras, N.D.; Stasinaki, A.-N.E.; Methenitis, S.K.; Krase, A.A.; Karampatsos, G.P.; Georgiadis, G.V.; Spengos, K.M.; Terzis, G. Rate of force development, muscle architecture, and performance in young competitive track and field throwers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchomel, T.J.; Nimphius, S.; Bellon, C.R.; Stone, M.H. The importance of muscular strength: Training considerations. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 765–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomei, S.; Hoffman, J.R.; Merni, F.; Stout, J.R. A comparison of traditional and block periodized strength training programs intrained athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, H.; Wirth, K.; Keiner, M.; Mickel, C.; Sander, A.; Szilvas, E. Short-term periodization models: Effects on strength and speed-strength performance. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howatson, G.; Brandon, R.; Hunter, A.M. The response to and recovery from maximum-strength and-power training in elite track and field athletes. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2016, 11, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.H.; Sanborn, K.I.M.; O’bryant, H.S.; Hartman, M.; Stone, M.E.; Proulx, C.; Ward, B.; Hruby, J. Maximum strength-power-performance. relationships in collegiate throwers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2003, 17, 739–745. [Google Scholar]

- Painter, K.B.; Haff, G.G.; Ramsey, M.W.; McBride, J.; Triplett, T.; Sands, W.A.; Lamont, H.S.; Stone, M.E.; Stone, M.H. Strength gains: Block versus daily undulating periodization weight training among track and field athletes. Int. J. Sports Phys. Perform. 2012, 7, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.P. Oversized young athletes: A weighty concern. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Oliver, J.L.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Howard, R.; De Ste Croix, M.B.A.; Williams, C.A.; Best, T.M.; Alvar, B.A.; Micheli, L.J.; Thomas, D.P.; et al. Long-term athletic development, part 2: Barriers to success and potential solutions. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faigenbaum, A.; Myer, G. Resistance Training among Young Athletes: Safety, Efficacy and Injury Prevention Effects. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 44, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichardo, A.W.; Oliver, J.L.; Harrison, C.B.; Maulder, P.S.; Lloyd, R.S.; Kandoi, R. Effects of combined resistance training and weightlifting on motor skill performance of adolescent male athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 3226–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retzepis, N.-O.; Avloniti, A.; Kokkotis, C.; Stampoulis, T.; Balampanos, D.; Gkachtsou, A.; Aggelakis, P.; Kelaraki, D.; Protopapa, M.; Pantazis, D.; et al. The Effect of Peak Height Velocity on Strength and Power Development of Young Athletes: A Scoping Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Oliver, J.L.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Howard, R.; De Ste Croix, M.B.A.; Williams, C.A.; Best, T.M.; Alvar, B.A.; Micheli, L.J.; Thomas, D.P.; et al. Long-term athletic development-part 1: A pathway for all youth. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 1439–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirwald, R.L.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.; Bailey, D.A.; Beunen, G.P. An assessment of maturity from anthropometric measurements. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 689–694. [Google Scholar]

- Isbiril, M.; Ispirlidis, I.; Chatzinikolaou, A.; Pafis, G.; Gioftsidou, A. Optimizing pre-match preparation: Impact of four warm-up protocols on yo-yo IR2 and sprint performance in youth footballers. J. Phys. Educ. Sports 2025, 25, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar]

- Shinkle, J.; Nesser, T.W.; Demchak, T.J.; McMannus, D.M. Effect of core strength on the measure of power in the extremities. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichmann, J.; Burchardt, H.; Tan, R.; Healy, P.D. Hip mobility and flexibility for track and field athletes. Adv. Phys. Educ. 2021, 11, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, P.; Freitas, T.T.; Rubio-Arias, J.Á.; Alcaraz, P.E. Complex and contrast training: Does strength and power training sequence affect performance-based adaptations in team sports? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 1461–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebben, W.P. Complex training: A brief review. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2002, 1, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Blazevich, A.J.; Wilson, C.J.; Alcaraz, P.E.; Rubio-Arias, J.A. Effects of Resistance Training Movement Pattern and Velocity on Isometric Muscular Rate of Force Development: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis and Meta-regression. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 943–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, T.F.; Cormack, S.J.; Gabbett, T.J.; Lorenzen, C.H. Self-reported wellness profiles of professional Australian football players during the competition phase of the season. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govus, A.D.; Coutts, A.; Duffield, R.; Murray, A.; Fullagar, H. Relationship between pretraining subjective wellness measures, player load, and rating-of-perceived-exertion training load in American college football. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yu, P.; Thirupathi, A.; Liang, M. How to improve the standing long jump performance? A mininarrative review. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2020, 2020, 8829036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, J.; Bezodis, N.E.; Blagrove, R.C.; Bezodis, I.N. A biomechanical comparison of accelerative and maximum velocity sprinting: Specific strength training considerations. Prof. Strength Cond. 2011, 21, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hermassi, S.; Schwesig, R.; Aloui, G.; Shephard, R.J.; Chelly, M.S. Effects of short-term in-season weightlifting training on the muscle strength, peak power, sprint performance, and ball-throwing velocity of male handball players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 3309–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaras, N.; Stasinaki, A.-N.; Arnaoutis, G.; Terzis, G. Predicting throwing performance with field tests. New Stud. Athl. 2016, 31, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dohoney, P.; Chromiak, J.A.; Lemire, D.; Abadie, B.R.; Kovacs, C. Prediction of one repetition maximum (1-RM) strength from a 4-6 RM and a 7-10 RM submaximal strength test in healthy young adult males. J. Exerc. Physiol. 2002, 5, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew, J.L.; Ball, T.E.; Arnold, M.D.; Bowen, J.C. Relative muscular endurance performance as a predictor of bench press strength in college men and women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 1992, 6, 200–206. [Google Scholar]

- Wathan, D. Load assignment. In Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning; Baechle, T.R., Ed.; Human Kinetics: Champain, IL, USA, 1994; pp. 435–439. [Google Scholar]

- LeSuer, D.A.; McCormick, J.H.; Mayhew, J.L.; Wasserstein, R.L.; Arnold, M.D. The accuracy of prediction equations for estimating 1-RM performance in the bench press, squat, and deadlift. J. Strength Cond. Res. 1997, 11, 211–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P.; Pandey, C.M.; Singh, U.; Gupta, A.; Sahu, C.; Keshri, A. Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2019, 22, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Zahediasl, S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: A guide for non-statisticians. Int. J. Endocr. Metab. 2012, 10, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G* power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faigenbaum, A.D.; Lloyd, R.S.; MacDonald, J.; Myer, G.D. Citius, Altius, Fortius: Beneficial effects of resistance training for young athletes: Narrative review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaras, N.; Spengos, K.; Methenitis, S.; Papadopoulos, C.; Karampatsos, G.; Georgiadis, G.; Stasinaki, A.; Manta, P.; Terzis, G. Effects of strength vs. ballistic-power training on throwing performance. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2013, 12, 130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Terzis, G.; Stratakos, G.; Manta, P.; Georgiadis, G. Throwing performance after resistance training and detraining. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Schlumberger, A.; Wirth, K.; Schmidtbleicher, D.; Steinacker, J. Different effects on human skeletal myosin heavy chain isoform expression: Strength vs. combination training. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 94, 2282–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haff, G.G.; Nimphius, S. Training principles for power. Strength Cond. J. 2012, 34, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.D.; Tolusso, D.V.; Fedewa, M.V.; Esco, M.R. Comparison of periodized and non-periodized resistance training on maximal strength: A meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2083–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapartidis, I.; Makroglou, V.; Kepesidou, M.; Milacic, A.; Makri, A. Relationship between sprinting, change of direction and jump ability in young male athletes. J. Phy. Educ. 2018, 5, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, T.; Fukashiro, S.; Harada, Y.; Kawamoto, K. Relationship between sprint performance and muscle fascicle length in female sprinters. J. Physiol. Anthropol. Appl. Hum. Sci. 2001, 20, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimphius, S.; McGuigan, R.M.; Newton, U.R. Changes in muscle architecture and performance during a competitive season in female softball players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 2655–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.