Abstract

Fine-grained action detection remains a challenging and actively studied problem. While previous methods predominantly rely on convolutional neural networks (CNNs), their limited modeling capacity and high computational cost restrict their effectiveness in fine-grained settings. To overcome these challenges, we propose Action-JointsLLM, a novel framework that leverages joints extracted from visual data and large language models (LLMs) for accurate and efficient fine-grained action detection. Specifically, we introduce a Joint2Text module that transforms sequences of human joints into natural language descriptions, enabling direct compatibility with LLMs. Additionally, we design an attn-pooling mechanism to identify the contributions of each joint and time step across the motion sequence, enabling more accurate action analysis. Our approach demonstrates strong generalization across different LLM backbones and achieves state-of-the-art performance on the PD-WALK dataset, using Parkinson’s disease detection as a representative fine-grained action recognition task.

1. Introduction

Fine-grained action detection refers to the subtle and precise recognition of action sequences, with wide applications in fields such as medical diagnostics and sports behavior analysis, where it holds significant research value. Unlike standard action recognition or classification, fine-grained detection emphasizes the perception and analysis of localized differences within the same action category. This form of recognition is inherently more complex and imposes heightened demands on feature extraction and processing mechanisms.

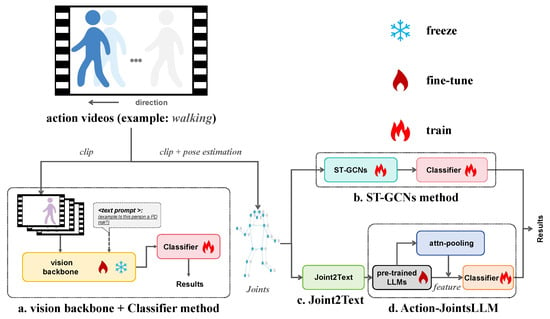

Despite its unique challenges, fine-grained detection also relies on standard action recognition architectures, typically comprising a vision backbone followed by a classifier (Figure 1a). Historically, CNN-based approaches [1,2,3,4,5,6] dominated this field. However, while effective for coarse categories, they often struggle to capture the subtle spatio-temporal nuances essential for fine-grained detection. Although auxiliary techniques like optical flow [3] can enhance sensitivity, their prohibitive computational costs restrict practical applicability.

Figure 1.

Frameworks for fine-grained action detection. (a) A classic action detection framework. (b) The ST-GCNs method framework. (c) The Joint2Text module. (d) The Action-JointsLLM framework.

The rise of Transformer architectures [7] and their extension into the visual domain through Vision Transformer (ViT) [8] have led to the development of numerous Transformer-based visual models (hereafter referred to as VisionT) [9,10,11,12,13]. These VisionT models have demonstrated performance comparable to, or even exceeding, that of CNN in action detection, making them promising candidates for the framework in Figure 1a. Nevertheless, VisionT models typically prioritize global semantic features for general recognition while often overlooking critical high-frequency local details, such as subtle kinematic variations. Moreover, their heavy reliance on massive pre-training data is incompatible with the scarcity of specialized fine-grained datasets. Consequently, although they effectively recognize coarse-grained actions, they struggle to identify fine-grained differences across individuals, a limitation empirically supported by our preliminary analysis in Appendix A.

These findings indicate that the performance bottleneck in the framework (Figure 1a) may not stem from the backbone (e.g., CNN or VisionT) itself, but rather from the framework’s overall design, which may be suboptimal for fine-grained motion understanding. An alternative framework is the Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks (ST-GCNs) method [14,15,16], as illustrated in Figure 1b. This approach leverages pose estimation [17,18] to convert subjects into joint sequences and applies ST-GCNs to capture their spatio-temporal dynamics. By abstracting away visual redundancies (e.g., clothing, background) and focusing on joint trajectories—around which human motion is naturally organized—ST-GCNs offer improved sensitivity to subtle movement variations. Meanwhile, the success of VisionT has overshadowed the potential of Transformer-based large language models (LLMs) in visual domains. Recently, these LLMs have shown strong reasoning abilities [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27], including in fine-grained medical tasks that involve clinical scores or diagnostic dialogues as input [28,29,30,31], highlighting their potential for complex action understanding. Motivated by these insights, we propose Action-JointsLLM (Figure 1d), a novel framework that integrates joint sequences derived from the visual modality into LLMs to enable efficient and accurate fine-grained action detection. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We introduce Action-JointsLLM, a novel framework that applies pre-trained Transformer-based LLMs to visual-domain motion analysis, marking a new paradigm for fine-grained action detection.

- We design a Joint2Text module that converts joint sequences into natural language descriptions, thereby enabling LLMs to perform fine-grained action reasoning on cross-modal visual data.

- We incorporate an attn-pooling mechanism to dynamically weight the importance of different joints and frames within a sequence, enabling the framework to generate a unified representation that comprehensively reflects each joint and frame’s contribution for more effective perception of overall motion.

- Extensive experiments on a Parkinson’s disease benchmark (PD-WALK) demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach, achieving state-of-the-art performance and further show strong robustness across multiple LLM backbones.

2. Related Work

2.1. Large Language Models (LLMs)

LLMs have attracted substantial attention due to their strong generalization capabilities across a wide range of NLP tasks [20,24]. Pre-trained on massive text corpora using autoregressive objectives, these models can generate coherent text, perform reasoning, and adapt to various downstream tasks through techniques such as fine-tuning. By reformatting data to align with the input structure of LLMs, they can be effectively applied to domain-specific tasks in areas such as sports, healthcare, and human motion analysis [28,32,33].

2.2. Feature Processing in Transformer

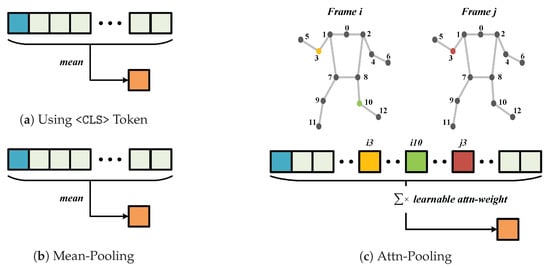

Transformer-based models typically output a last_hidden_state of shape [batch, seq, dim], representing the full token sequence. Refs. [34,35] have shown that information within this sequence is often unevenly distributed, with a significant portion concentrated on a few key tokens. To reduce computational cost and dimensionality, it is common to compress the output into a unified vector. Common strategies include prepending a special <CLS> token [36] to the input, where the corresponding output serves as the sequence representation (Figure 2a), and mean-pooling [37], which averages all token embeddings to produce a global feature representation (Figure 2b). However, these strategies often overlook the complex dynamics of human motion, where the contribution of different body parts varies dynamically over time and across different individuals. To mitigate this dilution of critical motion cues, we employ an attn-pooling mechanism to explicitly weigh these spatiotemporal features, ensuring more precise action reasoning.

Figure 2.

The compression methods of (a) <CLS> token, (b) mean-pooling and (c) attn-pooling. i3 denotes the token sequence of 3rd joint in Frame i, and i10 and j3 follow the same notation.

2.3. Transformer-Based Action Detection

Transformer architectures have been extensively adapted for action detection. Previous studies [38,39,40] have integrated textual concepts into VisionT by employing natural language to guide motion feature learning or to generate captions corresponding to visual inputs. However, their semantic alignment remains coarse-grained and still overlooks high-frequency kinematic details. Consequently, skeleton data remains a pivotal modality for fine-grained detection. Methods like MotionBERT [41] apply Transformers directly to skeleton sequences. Analogous to spatio-temporal convolutions in ST-GCNs, these models extract latent features via spatio-temporal attention. While effective at capturing body-part details, they fundamentally treat motion as numerical sequences rather than reasoning about fine-grained kinematic nuances. Distinct from these paradigms, our approach addresses these limitations by serializing fine-grained joint sequences into a “motion language” and leveraging the powerful reasoning capabilities of LLMs to efficiently detect subtle variations during motion (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Action-JointsLLM with existing action recognition paradigms. Our Action-JointsLLM uniquely integrates fine-grained kinematic capture with semantic reasoning capabilities. ✓ indicates that the method possesses this capability, while ✗ indicates that it does not.

3. Research Scenario and Dataset

3.1. Research Scenario in Action-JointsLLM

To better support fine-grained action detection, we focus on Parkinson’s disease (PD) as the primary research scenario in this paper for the following two reasons. First, PD detection requires inherently fine-grained analysis, as diagnosis depends on detecting subtle deviations from normal movement patterns within the same action category. For instance, a PD motion can be conceptualized as , where represents the anomaly. This characteristic renders PD an ideal case for studying fine-grained action detection. Second, the societal demand is considerable. As a prevalent neurodegenerative disorder, PD has seen a continuous increase in incidence, disability, and mortality over recent decades [42]. While conventional approaches (e.g., rating scales and sensors) provide reliable results, their cost and limited accessibility underscore the importance of developing vision-based, fine-grained detection methods for broader clinical use.

3.2. Dataset in Action-JointsLLM

The PD-WALK dataset [15], a representative joint-based dataset for fine-grained actions characteristic of PD, is collected in clinical settings and annotated by qualified medical professionals. Specifically, it comprises walking videos from 96 PD patients and 95 healthy controls, with each sample assigned a binary label (0 or 1). With appropriate authorization, we utilize this dataset for experimental analysis. During dataset construction, each motion video is segmented into clips, and human pose estimation is applied to each frame to obtain skeletal representations in the COCO-Pose [43] format. Each clip is represented as a tensor of shape [T, 17, 3], where T is the number of frames, 17 corresponds to body joints, and the final dimension contains the x and y coordinates along with the confidence score. After preliminary screening and basic preprocessing, we obtained a total of 9931 usable skeletal sequences.

4. Method

4.1. Joint2Text

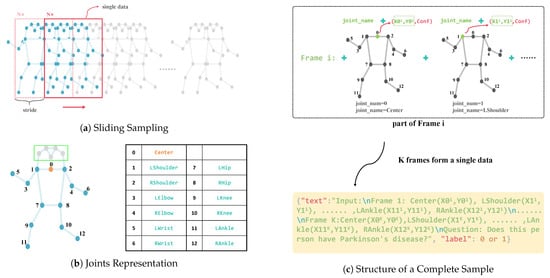

To make skeleton joint sequences compatible with LLMs, we propose a Joint2Text module that converts them into natural language descriptions (Figure 1c). The module comprises three main steps—sliding sampling, optimization, and reconstruction—which collectively perform resampling of the original data, joint selection and refinement, and the generation of new textual descriptions.

4.1.1. Sliding Sampling

Each raw sample typically contains 72 frames, with 17 joints per frame, resulting in high-dimensional and lengthy sequences that are unsuitable for direct input into models like Llama [21,23,24,26]. To address this, a sliding sampling strategy is employed to regulate the number of frames in each constructed sample. As illustrated in Figure 3a, a window of size N slides across the sequence to extract fixed-length clips. A stride parameter is introduced to enable data augmentation. When the stride is smaller than N, overlapping windows generate additional samples and promote the learning of intra-group similarities during training.

Figure 3.

Key components of Joint2Text. (a) The sampling procedure for constructing new samples. (b) Visualization of joints and their corresponding indices. (c) The reconstruction process of a complete sample.

4.1.2. Optimization

In this paper, we focus on postural movements of the arms and legs while placing less emphasis on head motion. As illustrated in Figure 3b, five head-related joints (eyes, ears, and nose) are excluded. To better represent overall body posture, the midpoint of the left and right shoulders is computed and used as the center of body (Equation (1)), where denotes the (x, y) coordinates of joint name at frame t. In this case, the coordinates of the body center are obtained by averaging the coordinates of the two shoulders. The skeletal sequences are then normalized. Let represent a sample with K frames and V joints per frame. The mean and variance of joint coordinates are computed per frame (Equation (2) and (3)), where denotes the frame index and denotes the joint index. A small constant is added to prevent division by zero. The final normalized coordinates are calculated using Equation (4), ensuring zero mean and unit variance per frame, thereby improving model stability during training. After processing, each frame contains 13 joints, which are re-indexed and relabeled as illustrated in Figure 3b.

4.1.3. Reconstruction

Finally, each sample is formatted as a dictionary: {‘text’: ..., ‘label’: ...}. As illustrated in Figure 3c, the ‘text’ field encodes a temporal textual description derived from K frames of joint data. For each frame, the description includes joint names followed by their (x,y) coordinates, arranged following a predefined indexing scheme. These per-frame descriptions are concatenated in chronological order to form the complete ‘text’ sequence. A task-specific prompt—such as ‘Question: Does this person have Parkinson’s disease?’—is appended to the end of the sequence to guide the model toward the detection task.

4.1.4. Design Principles

To ensure the robustness and effectiveness of the Joint2Text, our design choices are grounded in the following rationale:

- Joint Selection: We specifically excluded five head-related keypoints (eyes, ears, and nose) to eliminate high-frequency jitter often introduced by pose estimators. This directs the model’s focus to core body joints, which possess the most significant diagnostic value for identifying PD-related motor symptoms.

- Normalization: The normalization strategy aims to decouple action semantics from the camera viewpoint. By enforcing zero mean and unit variance per frame, the LLMs process relative motion patterns rather than absolute pixel coordinates, avoiding errors arising from changes in camera perspective.

- Textual Format Encoding: The encoding method used in reconstruction binds each joint coordinate with a corresponding joint name. This aligns numerical motion data with the LLM’s pre-trained knowledge of human anatomy, facilitating a more efficient reasoning process compared to processing raw numerical sequences.

4.2. Action-JointsLLM

As illustrated in Figure 1d, following the Joint2Text module, we propose a novel Action-JointsLLM framework comprising two key stages: (1) fine-tuning the pre-trained LLMs on the reconstructed dataset, and (2) performing action classification on the LLMs-extracted features, which are effectively compressed by our proposed attn-pooling mechanism.

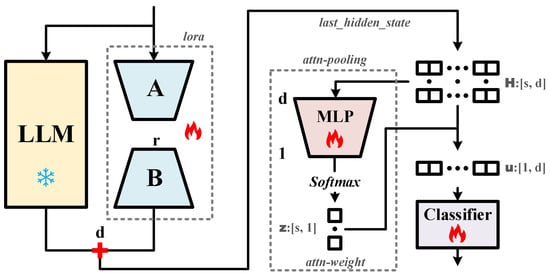

4.2.1. Fine-Tuning LLMs

To reduce computational costs during the fine-tuning of LLMs, we adopt the Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) technique [44]. Since transformer-based LLMs such as Llama [21,23,24,26] rely heavily on self-attention mechanisms, LoRA modules are inserted into key components of the attention blocks, specifically the q_proj, k_proj, v_proj, and o_proj layers. As illustrated in Figure 4 (left), the majority of the original LLM remains frozen during fine-tuning, with updates restricted to the low-rank modules (A and B). This results in a highly efficient training process, updating only 0.15–0.25% of the total trainable parameters (Table 2), thereby substantially reducing the demand for computational resources.

Figure 4.

Model architecture of Action-JointsLLM. The left panel illustrates the LoRA-based fine-tuning process of the LLM, while the right panel depicts the feature processing and classification pipeline incorporating attn-pooling. The symbols used to indicate frozen, fine-tuned, and trained components are consistent with those in Figure 1.

Table 2.

The parameters in Action-JointsLLM. Total Params include backbone, LoRA, attn-pooling and classifier, Trainable Params denote the number of parameters updated during training, while Ratio indicates the proportion of trainable parameters relative to the total number of model parameters.

4.2.2. Classifier and Feature Processing

To perform downstream classification, the features extracted by LLMs must be further processed. In fine-grained action detection, we employ a classifier composed of several linear layers and activation functions that map the features to class logits. As discussed in Section 2.2, these features require effective compression before classification. A major challenge in fine-grained action detection is the unequal importance of different joints and time steps (frames). However, the <CLS> token and mean-pooling may fail to capture the varying importance of different tokens, thereby limiting the model’s capacity to comprehensively evaluate the motion sequence. This motivates the adoption of the proposed attn-pooling mechanism.

4.2.3. Attn-Pooling

To address the challenges discussed in Section 4.2.2, inspired by [45], we propose attn-pooling. However, distinct from the initial purpose of [45], where importance scores are computed primarily to enhance inference efficiency, the objective of our attn-pooling is to adaptively learn a specific weight for each input token. By prioritizing tokens that represent active motion features during the aggregation into a unified vector representation, our method accurately captures the unequal contributions from different joints and frames.

Figure 2c illustrates the fundamental mechanism of our attn-pooling, where Frame i and Frame j represent skeletal data at distinct timestamps. In practice, although the representation of a single joint consists of a sequence of multiple tokens (as detailed in Figure 3c), we depict it as a single token block in this figure for clarity and visual simplification. During the compression process, learnable weights are assigned to each token individually, enabling the model to capture fine-grained variations at the token level. In this paper, we denote these learnable weights as attn-weight.

The right panel of Figure 4 illustrates the computation of attn-weights within the Action-JointsLLM framework. For notational clarity, we assume a batch size of 1 and denote the last_hidden_state as , where s is the sequence length and d is the feature dimension. This feature sequence is passed through a lightweight, learnable multi-layer perceptron (MLP) tailored for this task. During training, the MLP learns a scalar score l for each token via projection and activation functions. Specifically, taking the i-th token as an example, its corresponding feature vector is processed by the MLP to yield a raw score (Equation (5)). It is important to note that invalid or placeholder tokens may be present in the LLM output. To address this, we implement a score masking strategy (Equations (6) and (7)). As defined in Equation (6), any invalid token is assigned a score of , ensuring that its contribution approaches zero after the subsequent Softmax, thereby effectively masking it. Let denote the updated score for token i, and (in Equation (7)) represent the vector containing the updated scores for the entire sequence. As shown in Equation (8), is then normalized via Softmax to yield the final attn-weights vector , which quantifies the relative importance of each token.

Equation (9) formulates the final pooling process. Let denote the attn-weight assigned to the i-th token. The feature vector corresponding to this token is aggregated based on to yield the final unified vector representation , which serves as the input for subsequent classifier training.

5. Experimental Results and Discussion

To evaluate the performance of our Action-JointsLLM framework and its key components, we conduct extensive experiments using various pre-trained LLMs as backbone, including Llama2-7B URL: https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/Llama-2-7b-hf (accessed on 8 January 2026), Llama3-8B URL: https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/Meta-Llama-3-8B (accessed on 8 January 2026), Qwen2-7B URL: https://huggingface.co/Qwen/Qwen2-7B (accessed on 8 January 2026) and Qwen3-8B URL: https://huggingface.co/Qwen/Qwen3-8B (accessed on 8 January 2026). To mitigate computational costs and ensure convergence, we employed LoRA fine-tuning (Rank = 8, alpha = 16, dropout = 0.05) and each model is trained on 4 RTX3090 GPUs (lr = , batch_size = 2, epoch = 20). The main results are summarized in Table 3. The experiments demonstrate that the proposed Action-JointsLLM achieves consistently strong performance across all evaluated backbone architectures, underscoring its effectiveness and robustness. In the following subsections, we provide a detailed discussion of each key component.

Table 3.

Results of Action-JointsLLM with various LLM backbones under different settings of N and stride. ✗ in the Stride column denotes ‘no stride’.

5.1. Sliding Size (N) and Stride in Joint2Text

We consider two critical parameters in the Joint2Text module: sliding size (N) and stride. Specifically, we use sizes of 24 and 18, and evaluate two stride strategies—‘no stride’ and ‘stride =N/2’—to assess their impact. As shown in Table 3, selecting a smaller size (N) effectively increases the number of samples, thereby enhancing model performance under identical training conditions. Furthermore, across all backbone architectures, the model consistently outperforms the ‘no stride’ configuration when the ‘stride =N/2’ is applied. This indicates that capturing intra-group similarities during training significantly improves the model’s performance.

5.2. Ablation for Textual Prompt

To assess the contribution of the textual prompt in the data construction process, we conduct an ablation experiment with a sequence length of N = 72. Under this condition, the length of a single constructed data sequence exceeds the input capacity of the LLMs. Consequently, the model only has access to joint information and is unable to incorporate the textual prompt during training. The experimental results, presented in Table 4, reveal a significant performance drop when the prompt is excluded. This finding underscores the critical role of the textual prompt in guiding the model to interpret the skeletal data correctly.

Table 4.

Ablation study on the effect of the textual prompt. N = 72 indicates the absence of textual prompt information. All results are generated under the ‘no-stride’ setting.

5.3. Ablation for Attn-Pooling

We further demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed attn-pooling mechanism. As presented in Table 5, an ablation study performed on Llama-based backbone models reveals that replacing attn-pooling with simple mean-pooling results in a significant decline in performance. This confirms that different frames and joints contribute unequally to the overall movement patterns. The attn-pooling mechanism enables the model to assign relative importance (weights) to each component, integrate these weights into the unified vector representation, and more effectively capture the subtle nuances of overall motion.

Table 5.

Ablation study on the effect of attn-pooling using Llama as the backbone. ✓ indicates the use of attn-pooling, while ✗ (mean) denotes mean-pooling. All results are generated under the ‘no-stride’ setting.

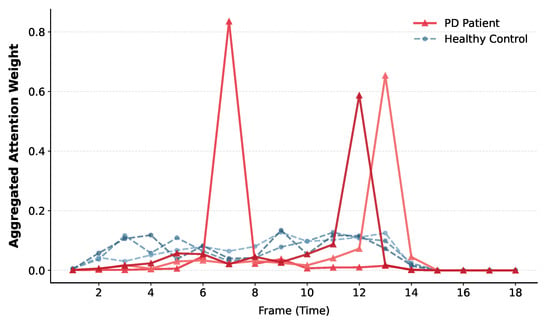

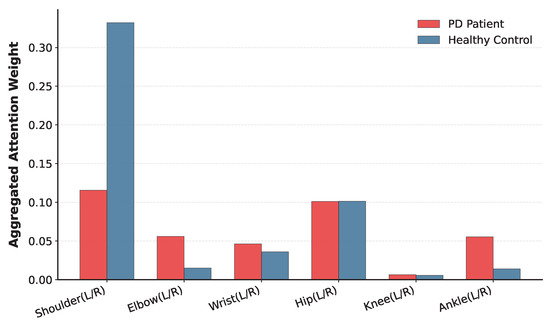

To explicitly visualize these dynamic contributions, we aggregated the attention weights associated with tokens representing different frames and joints, conducting visualization analyses in both temporal and spatial domains, respectively. Figure 5 illustrates the results of the temporal visualization analysis. We use data processed with N = 18 and ‘stride =N/2’, randomly selecting 3 PD patients and 3 healthy controls. It can be observed that PD patients exhibit distinct motion anomalies at specific moments during locomotion. Consequently, the model assigns significantly higher attention weights to these timestamps; the prominent peaks in the red lines correspond to instances of abnormal actions. In contrast, since healthy controls maintain a relatively stable gait, the attention distribution remains comparatively uniform (blue lines). Figure 6 presents the visualization analysis in the spatial domain. Distinct differences can be observed in the model’s attention focus on anatomical joints. Specifically, the main trunk (e.g., shoulders) of PD patients tends to be rigid with minimal variation; thus, the model pays less attention to these areas compared to healthy controls. Conversely, due to tremors in the extremities, the model exhibits higher attention levels at joints such as the elbows and ankles in PD patients.

Figure 5.

Temporal visualization analysis of attn-pooling mechanism. The red lines represent the frame-wise attention weights for PD patients, while the blue lines represent healthy controls. 3 representative samples are displayed for each group. The distinct peaks in the red lines indicate specific moments where the model focuses on abnormal motion patterns.

Figure 6.

Spatial visualization analysis of attn-pooling mechanism. The red bars represent the spatial attention weights on different anatomical parts for PD patients, and the blue bars represent healthy controls. Note that bilateral joints (left and right sides) are aggregated, and the center positioning joint is excluded for clearer visualization.

5.4. Comparison with Prior Works

To further illustrate the effectiveness of our model, beyond the backbone comparison in Table 3, we compare our method with previous state-of-the-art approaches evaluated on the PD-WALK dataset [15]. The results are presented in Table 6. While the original STGCN method [14] provides a reasonable performance baseline, the method proposed in [15] demonstrates marked improvements by dividing joints into Local connections and Global connections branches, enabling a more comprehensive assessment of each joint’s contribution to movement.

Table 6.

Comparison of Action-JointsLLM and prior methods on the PD-WALK dataset. Reported scores for Action-JointsLLM reflect the best-performing settings for each LLM backbone.

However, our ActionJoints-LLM yields substantial performance gains over these approaches. These improvements are primarily attributed to two factors:

- The powerful comprehension and reasoning capabilities of LLMs enable a deeper interpretation of joint dynamics through textual descriptions.

- The introduction of attn-pooling allows the model to account for the varying importance of different joints over time.

Consequently, these components facilitate a more nuanced and precise assessment of movement.

5.5. Generalizability Analysis

To evaluate the generalizability of our METHOD, we conduct additional experiments using raw skeletal data from the widely used multi-class NTU RGB+D 60 dataset [46]. We select a diverse subset of 10 action classes, including pickup, throw, sitting down, putting on a hat, hand waving, kicking, jumping, phone call, punching, and pushing, which encompasses movements involving different body parts and interactive scenarios (Total samples: 9455). Following the optimal configuration (N = 18, ‘stride =N/2’, Llama3-8B), the results are presented in Table 7. While the performance on this 10-class task is modest compared to the PD scenario, it is important to note that our method is originally tailored for binary fine-grained anomaly detection. A performance drop when extending to a diverse multi-class task is expected. Nevertheless, the model achieves an accuracy of over 62%, significantly outperforming random guessing. This demonstrates the method’s fundamental capability to learn motion representations and indicates a promising degree of generalizability. Consequently, our method may offer valuable insights for future work aiming to adapt fine-grained action reasoning frameworks to general-purpose scenarios.

Table 7.

Generalizability analysis. Performance comparison between the fine-grained PD-WALK dataset and the NTU RGB+D dataset (10-class).

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes Action-JointsLLM, a novel framework for fine-grained action detection in the visual modality, which leverages Transformer-based LLMs to capture the features of overall movement. The framework fully exploits the advantages of joint data—information-rich and robust to environmental noise. With our proposed Joint2Text module, joint data is converted into an LLM-compatible format, enabling our framework to harness the reasoning capabilities of LLMs for effectively capturing subtle joint movements. An additional textual prompt further steers LLMs toward fine-grained action understanding, enhancing both accuracy and efficiency. Moreover, we introduce an attn-pooling mechanism with learnable weights to fuse temporal and joint features, effectively mitigating uneven contributions from different joints and time steps. By integrating these components and taking PD detection as a representative scenario, the proposed Action-JointsLLM achieves state-of-the-art performance on the PD-WALK dataset () and demonstrates robustness across various LLM backbones.

However, this work inevitably exhibits several limitations. First, the current evaluation is primarily limited to binary PD anomaly detection on a single dataset (PD-WALK), with ST-GCNs–based methods serving as the main baselines. This focus restricts the functional scope and comprehensive performance evaluation of the proposed model. Although we conducted a generalization analysis on an additional action dataset in Section 5.5, substantial room for improvement remains. Second, employing LLMs as the primary backbone incurs substantial computational overhead during inference. Furthermore, to address the specific requirements of the PD task and mitigate real-world pose estimation errors, we adopt strict data optimization strategies within the Joint2Text module. While these strategies yield strong task-specific performance, they introduce inherent constraints on model generalizability. Nevertheless, these limitations do not undermine the validity of our findings; rather, they underscore the foundational nature of the framework and motivate future research directions.

Consequently, future research will focus on the following directions. First, we plan to expand the scope of evaluation to larger-scale datasets and multi-class settings for general fine-grained action detection (e.g., hand-centric movements), and to extend the framework’s applicability to other specialized medical scenarios, including multiple sclerosis, Huntington’s disease, and essential tremor. Second, we will systematically benchmark the proposed attn-pooling mechanism against modern pooling alternatives [47,48,49,50], with the goal of improving feature quality and inference efficiency while modeling unequal joint and frame contributions. Third, we will explore alternative encodings that preserve full skeletal topology, aiming to construct efficient motion sequences that robustly handle real-world pose estimation errors. Through these advancements, we seek to further unlock the potential of LLM-based reasoning for complex action analysis in both clinical and general domains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Q. and C.S.; methodology, Y.Q. and C.S.; software, Y.Q.; validation, Y.Q.; formal analysis, Y.Q.; investigation, Y.Q. and C.S.; resources, H.Z. and Y.Y.; data curation, Y.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Q.; writing—review and editing, Y.Q., H.Z. and Y.Y.; supervision, H.Z. and Y.Y.; project administration, H.Z.; funding acquisition, H.Z. and Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the “Leading Goose + X” Science and Technology Program of Zhejiang Province of China (2025C02104).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study used publicly available datasets (PD-WALK, TULIP) for which ethical approval and participant consent were already obtained by the dataset providers.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study used publicly available datasets (PD-WALK, TULIP), for which all necessary participant consents were previously obtained by the dataset providers.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are publicly available and can be accessed from their respective official websites.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all contributors who provided administrative and technical support during the course of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| VisonT | Transformer-based visual models |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| ST-GCNs | Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks |

| LLMs | Large language models |

| LoRA | Low-Rank Adaptation |

Appendix A. Experiments for VisionT

This Appendix material presents preliminary experiments to assess the suitability of VisionT for fine-grained action detection.

Appendix A.1. Experimental Setup

With permission from the authors, we use the TULIP dataset [51], focusing on gait-related videos, which are then preprocessed into frame sequences. We design three experimental settings: (1) no-text guidance, (2) post-temporal guidance, and (3) pre-temporal guidance. For no-text guidance, we employ pre-trained backbones vivit-b-16x2 URL: https://huggingface.co/google/vivit-b-16x2 (accessed on 8 January 2026)and vivit-b-16x2-kinetics400 URL: https://huggingface.co/google/vivit-b-16x2-kinetics400 (accessed on 8 January 2026) to directly process the temporal frame sequence. In post-temporal guidance, we enhance the ViViT model by incorporating a textual prompt and fusing it with visual information through cross-attention, guiding the model after temporal modeling. In pre-temporal guidance, we leverage VLMs such as Qwen2.5-VL URL: https://huggingface.co/Qwen/Qwen2.5-VL-7B-Instruct (accessed on 8 January 2026) to align visual and textual features at the frame level, using prompts to guide attention before temporal modeling. A Transformer is then used for final temporal aggregation. Across all settings, we also adopt PD detection as research scenario.

Appendix A.2. Experimental Results and Discussion

As shown in Table A1, when using ViViT alone, the model exhibits limited performance. Incorporating the ViViT backbone pre-trained on Kinetics-400 [52] leads to a moderate improvement, as the model has learned general priors related to human actions. However, the overall performance remains suboptimal. With the introduction of textual guidance, we observe a significant performance boost, demonstrating the effectiveness of VisionT. Nonetheless, video data inherently contains non-motion-related noise, including clothing styles, backgrounds, and lighting conditions. When applied to unseen subjects, model performance drops substantially, indicating limited generalization ability. Further experiments using pre-temporal guidance show that VLMs like Qwen2.5-VL can leverage textual prompts to focus attention on target individuals. However, the extracted features struggle to capture subtle temporal distinctions necessary for fine-grained motion analysis.

Based on these results, we conclude that although VisionT offers strong performance under controlled conditions, it still falls short in capturing nuanced action patterns required for fine-grained action detection. Future research should focus on suppressing visual distractions and exploring data modalities that better capture subtle motion variations.

Table A1.

Experimental results of VisionT under three different settings. XATTN denotes the use of textual guidance with cross-attention; unseen indicates evaluation on previously unseen subjects; ATTN refers to the standard attention mechanism used for temporal modeling.

Table A1.

Experimental results of VisionT under three different settings. XATTN denotes the use of textual guidance with cross-attention; unseen indicates evaluation on previously unseen subjects; ATTN refers to the standard attention mechanism used for temporal modeling.

| Method | F1-Score | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| vivit-b-16x2 | ||

| vivit-b-16x2-kinetics400 | ||

| vivit-b-16x2 + XATTN | ||

| vivit-b-16x2-kinetics400 + XATTN | ||

| vivit-b-16x2 + XATTN + unseen | ||

| vivit-b-16x2-kinetics400 + Xattn + unseen | ||

| Qwen2.5-VL + 3 layers ATTN |

References

- Karpathy, A.; Toderici, G.; Shetty, S.; Leung, T.; Sukthankar, R.; Li, F.-F. Large-scale video classification with convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1725–1732. [Google Scholar]

- Yue-Hei Ng, J.; Hausknecht, M.; Vijayanarasimhan, S.; Vinyals, O.; Monga, R.; Toderici, G. Beyond short snippets: Deep networks for video classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 4694–4702. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Two-stream convolutional networks for action recognition in videos. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Feichtenhofer, C.; Pinz, A.; Zisserman, A. Convolutional two-stream network fusion for video action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1933–1941. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, D.; Bourdev, L.; Fergus, R.; Torresani, L.; Paluri, M. Learning spatiotemporal features with 3d convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 4489–4497. [Google Scholar]

- Carreira, J.; Zisserman, A. Quo vadis, action recognition? a new model and the kinetics dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 6299–6308. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Arnab, A.; Dehghani, M.; Heigold, G.; Sun, C.; Lučić, M.; Schmid, C. Vivit: A video vision transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 6836–6846. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual instruction tuning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 36, pp. 34892–34916. [Google Scholar]

- Bordes, F.; Pang, R.Y.; Ajay, A.; Li, A.C.; Bardes, A.; Petryk, S.; Mañas, O.; Lin, Z.; Mahmoud, A.; Jayaraman, B.; et al. An introduction to vision-language modeling. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.17247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Yang, S.; Wang, S.; Tan, S.; Wang, P.; Lin, J.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J. Qwen-VL: A Versatile Vision-Language Model for Understanding, Localization, Text Reading, and Beyond. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12966. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; Song, S.; Dang, K.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; et al. Qwen2.5-vl technical report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.13923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Xiong, Y.; Lin, D. Spatial temporal graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Yang, T.; Yang, C.; Zhou, H. Integrated Equipment for Parkinson’s Disease Early Detection Using Graph Convolution Network. Electronics 2022, 11, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q. Actional-structural graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 3595–3603. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.E.; Sheikh, Y. Realtime multi-person 2d pose estimation using part affinity fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 7291–7299. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Xiao, B.; Liu, D.; Wang, J. Deep high-resolution representation learning for human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 5693–5703. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Chu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Dang, K.; Deng, X.; Fan, Y.; Ge, W.; Han, Y.; Huang, F.; et al. Qwen technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grattafiori, A.; Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Vaughan, A.; et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.21783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, Q. Qwen2 technical report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.15115. [Google Scholar]

- Meta, A. The Llama 4 Herd: The Beginning of a New Era of Natively Multimodal AI Innovation. 2025. Available online: https://ai.meta.com/blog/llama-4-multimodal-intelligence/ (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Yang, A.; Li, A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Gao, C.; Huang, C.; Lv, C.; et al. Qwen3 technical report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.09388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, A.; Lawler, P.R.; Ba, J.; Krishnan, R.G.; Rubin, B.B.; Wang, B. Clinical camel: An open-source expert-level medical language model with dialogue-based knowledge encoding. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.12031. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Yang, G.; Du, Z.; Fan, L.; Li, X. ClinicalGPT: Large language models finetuned with diverse medical data and comprehensive evaluation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.09968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Cheng, T.; Cheng, Y.; Feng, R. Finemedlm-o1: Enhancing the medical reasoning ability of llm from supervised fine-tuning to test-time training. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.09213. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, T.; Schaekermann, M.; Palepu, A.; Saab, K.; Freyberg, J.; Tanno, R.; Wang, A.; Li, B.; Amin, M.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Towards conversational diagnostic artificial intelligence. Nature 2025, 642, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tracy, R.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, D.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.f.; Shen, W. Sportqa: A benchmark for sports understanding in large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.15862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Bi, J.; Xu, S.; Song, L.; Liang, S.; Wang, T.; Zhang, D.; An, J.; Lin, J.; Zhu, R.; et al. Video understanding with large language models: A survey. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025. early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Tian, Y.; Chen, B.; Han, S.; Lewis, M. Efficient streaming language models with attention sinks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.17453. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, G.; Lin, J.; Seznec, M.; Wu, H.; Demouth, J.; Han, S. SmoothQuant: Accurate and Efficient Post-Training Quantization for Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning; JMLR.org: Norfolk, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-bert: Sentence embeddings using siamese bert-networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.10084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xing, J.; Liu, Y. Actionclip: A new paradigm for video action recognition. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.08472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Bing, L. Video-llama: An instruction-tuned audio–visual language model for video understanding. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.02858. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Leng, S.; Zhang, H.; Xin, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, G.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Luo, Z.; Zhao, D.; et al. Videollama 2: Advancing spatial-temporal modeling and audio understanding in video-llms. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.07476. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Ma, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L.; Wu, W.; Wang, Y. MotionBERT: A Unified Perspective on Learning Human Motion Representations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Parkinson disease: A public health approach. Technical Brief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common objects in context. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Proceedings, Part V 13; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Virtual, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Datta, G.; Kundu, S.; Beerel, P.A. Self-Attentive Pooling for Efficient Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 3974–3983. [Google Scholar]

- Shahroudy, A.; Liu, J.; Ng, T.T.; Wang, G. NTU RGB+D: A large scale dataset for 3D human activity analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1010–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Bolya, D.; Fu, C.Y.; Dai, X.; Zhang, P.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Hoffman, J. Token Merging: Your ViT But Faster. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2210.09461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girdhar, R.; Ramanan, D. Attentional pooling for action recognition. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo, M.; Piergiovanni, A.; Arnab, A.; Dehghani, M.; Angelova, A. Tokenlearner: Adaptive space-time tokenization for videos. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 34, pp. 12786–12797. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Liu, B.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J.; Hsieh, C.J. Dynamicvit: Efficient vision transformers with dynamic token sparsification. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 34, pp. 13937–13949. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Lyu, S.; Mantri, S.; Dunn, T.W. TULIP: Multi-camera 3D Precision Assessment of Parkinson’s Disease. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 22551–22562.

- Kay, W.; Carreira, J.; Simonyan, K.; Zhang, B.; Hillier, C.; Vijayanarasimhan, S.; Viola, F.; Green, T.; Back, T.; Natsev, P.; et al. The kinetics human action video dataset. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.06950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.