Abstract

The rise in Blockchain-based digital assets has transformed the financial ecosystems, which has also created complex governance and taxation challenges. The pseudonymous and cross-border nature of crypto transactions undermines traditional tax enforcement, leaving regulators such as the South African Revenue Service (SARS) reliant on voluntary disclosures with limited verification mechanisms, while existing Blockchain forensic tools and regulatory technologies (RegTechs) have advanced in anti-money laundering and institutional compliance, their integration into issues related to taxpayer compliance and locally adapted solutions remains underdeveloped. Therefore, this study conducts a state-of-the-art review of Blockchain forensics, RegTech innovations, and crypto tax frameworks to identify gaps in the crypto tax compliance space. Then, this study builds on these insights and proposes a conceptual model that integrates digital forensics, cost basis automation aligned with SARS rules, wallet interaction mapping, and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) as verifiable audit anchors. The contributions of this study are threefold: theoretically, which reconceptualise the adoption of Blockchain forensics as a proactive compliance mechanism; practically, it conceptualises a locally adapted proof-of-concept for diverse transaction types, including DeFi and NFTs; and lastly, innovatively, which introduces NFTs to enhance auditability, trust, and transparency in digital tax compliance.

1. Introduction

Since the emergence of Bitcoin, as first conceptualised by Satoshi Nakamoto [1], Blockchain-based digital assets have fundamentally transformed the global financial and technological ecosystem by enabling decentralized, pseudonymous, peer-to-peer transactions [2,3]. The rapid proliferation of these digital assets, encompassing cryptocurrencies, stablecoins, utility tokens, non-fungible tokens (NFTs), and decentralized finance (DeFi) protocols, has created new avenues for financial innovation and inclusion. However, these digital assets also pose significant governance and taxation challenges for legal and regulatory bodies [4], the pseudonymous nature of crypto transactions, the cross-border mobility of digital assets, and the lack of a harmonized regulatory framework have enabled tax evasion, money laundering, and regulatory arbitrage [5,6]. Regulatory arbitrage in this case refers to the practice of exploiting differences or gaps in regulations between various jurisdictions to circumvent more stringent rules with the aim of reducing compliance costs or gaining competitive advantages. In response to this, multilateral organisations such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have called on jurisdictions to implement robust anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorism financing (CTF) measures to strengthen their tax compliance mechanisms for crypto asset holders (CAHs) [7].

The emerging economies, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, have witnessed some of the world’s fastest-growing crypto adoption rates, driven by macroeconomic volatility, structural financial exclusion, a tech-savvy population, and the search for alternative stores of value and investments [8]. In South Africa, the South African Revenue Service (SARS) continues to face substantial challenges in enforcing digital asset tax compliance, with only partial guidance covering limited transaction types [9]. SARS relies heavily on voluntary disclosure, and annual self-filing means that CAHs bear the burden of accurate reporting, leaving significant room for unintentional errors, deliberate tax evasion, and exploitation of regulatory gaps.

Furthermore, South Africa’s grey-listing by the FATF [10] highlights the urgent need for innovative compliance solutions that align with international standards. The complexity of crypto asset transactions, particularly when transacted across borders, adds another layer of difficulty in AML, CTF, and tax enforcement efforts [11]. Notably, on the 13th of March 2025, the South African Reserve Bank announced that the country is now compliant with 37 out of 40 FATF recommendations, and one of these recommendations was deemed to be inapplicable [12], while significant progress has been made, especially when it comes to mandating the crypto asset service providers (CASPs) to implement AML and CTF controls, including sharing crypto-related data with regulatory bodies such as SARS. However, the blind spots remain when it comes to harmonising these data for effective tax compliance, particularly in cases involving CASPs that operate outside the South African jurisdiction, since they are beyond direct regulatory reach. The risk of non-cooperation by foreign CASPs underscores the need for robust mechanisms to facilitate international data exchange, a concern highlighted in a media release issued by SARS on 9 October 2024, which warned taxpayers of heightened crypto tax compliance scrutiny [13].

This study is positioned within ongoing research that initially proposed a conceptual model [11] for visualising the tax compliance issues and outlining a potential technical solution. The initial model introduced the notion of leveraging advanced visualisation techniques for Blockchain wallet address interactions and employing the use of NFTs as a verification tool for tax reports. However, the NFT component within the proposed model was not explored in detail. Hence, this study extends the prior research by systematically exploring the process involved in generating and verifying crypto tax reports through NFTs. Furthermore, it examines the integration of digital forensics processes to ensure the integrity of evidence collection, secure storage, and reliable analysis of tax reports and NFT artefacts. This forensic dimension is critical to strengthening audit trails and reinforcing trust in the compliance process.

The remainder of this research study is structured as follows: the adopted research method is detailed in Section 2. Section 3 of this study provides the literature review, which explores the background details that focus on the broader global perspective of digital assets and tax compliance, as well as a thematic view of the literature, which focuses on the concepts that are related to Blockchain forensics, regulatory technology (RegTech), and taxation framework. Section 4 presents the proposed conceptual model, which outlines the previous model and the extended concepts that seek to provide emphasis on the utilisation of the NFTs as a verification mechanism for tax report metadata submitted by taxpayers to regulatory bodies. Section 5 details the analysis and synthesis of the study. Section 6 positions the research study contribution within the context of contemporary research on Blockchain forensics and RegTechs, while Section 7 outlines privacy and adoption concerns that might be associated with the proposed model. Thereafter, Section 8 details the limitations and shortcomings of this research study. Finally, Section 9 provides the concluding remarks of the study and future work.

2. Research Methods

This study has adopted the following research methods to achieve the desired objectives: design science research (DSR), literature review, and modelling methodologies. The DSR methodology is used to enhance the functionality of the existing crypto tax compliance solution [14]. A comprehensive state-of-the-art literature study is used to understand the identified problem by surveying peer-reviewed and policy-oriented sources published across major scholarly databases (e.g., Scopus, IEEE Xplore, SpringerLink, and Google Scholar) and policy documents sourced from government legislation, official publications, and other relevant sources. The following compound search strings: “blockchain forensics” AND “crypto tax”, “RegTech” AND “South Africa”, “SARS” AND “crypto assets”, “DeFi taxation”, and “NFT taxation” were used to capture a comprehensive body of literature. After obtaining a holistic understanding of crypto tax compliance, this study proposes a model that could be used by South African taxpayers to voluntarily declare their crypto assets to the South African tax authority.

3. Literature Review

This section is divided into five subsections, namely: background details on the global perspective, Blockchain forensics tools and techniques, regulatory technologies (RegTechs) and automation for compliance, crypto asset taxation frameworks, and limitations of the identified gaps. The first subsection provides a global perspective on the tax treatment of digital assets across multiple jurisdictions. The second subsections examine the existing forensic tools and techniques used to investigate Blockchain-related illicit activities, including tax evasion. The third subsection reviews regulatory technologies (RegTech) and automation models designed to support supervisory and compliance processes within digital-asset ecosystems. The fourth subsection explores the academic and policy frameworks that seek to guide the classification, treatment, and reporting of crypto-related taxable events across different jurisdictions. Finally, the last subsection synthesises cross-cutting shortcomings within the literature and articulates how these gaps motivate the need for the conceptual model proposed in this study.

3.1. Background Details on the Global Perspective

Most of the early research work in the digital asset taxation space was centred on classifying digital assets within existing traditional tax regimes, a debate that remains unresolved due to the lack of consistent, globally accepted definitions and standards [5,15]. For instance, the United States of America (USA) treats digital assets as property, subjecting crypto transactions to capital gains tax (CGT) under the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which is similar to how CGT is applied to tangible assets [16]. The United Kingdom treat digital assets similarly to property or shares, applying CGT on certain crypto transactions [11]. The other jurisdictions have developed sophisticated taxonomies that distinguish between digital asset types, e.g., stablecoins, utility tokens, and NFTs, each of which has distinct tax implications [17].

In South Africa, the SARS classifies digital assets as a financial instrument rather than legal tender [18,19], which has significant implications on how these assets are integrated into the existing tax rules and compliance process. A recent study by [20] has highlighted how emerging crypto activities such as staking, DeFi lending, liquidity mining, and NFT transactions create complex new taxable events that challenge legacy tax frameworks. Accurate valuation remains a persistent issue, given the extreme volatility of crypto prices across decentralised exchanges operating 24 h a day and seven days a week, unlike how the stock market operates, which mostly operates within a restricted time frame from Monday to Friday [5].

The bibliometric analysis by [17] shows that the research clusters are increasingly focusing on the development of automated reporting tools, harmonising global policy frameworks, and developing localised compliance solutions that take into consideration the realities faced by small taxpayers in emerging markets or economies. Hence, various comparative studies depict glaring jurisdictional differences in regulatory approaches. For example, Germany exempts long-term crypto holdings from CGT under certain conditions [17]. Singapore and Portugal have adopted favourable tax regimes to attract crypto investors [17], while the USA requires CASPs to report crypto transactions to the IRS [21]. Furthermore, countries such as India and Nigeria have introduced flat-rate taxation and automatic withholding mechanisms as strategies to reduce the risk associated with tax evasion [22,23].

Table 1 summarises the global approach associated with the crypto asset taxation across a selection of key jurisdictions. These jurisdictions include countries such as the USA, the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, Japan, South Korea, India, South Africa, Brazil, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Singapore, France, Russia, Nigeria, Denmark, Belgium, Malta, Bulgaria, Netherlands, and Austria. Note that all these jurisdictions were selected based on their influential roles in advancing digital asset adoption, as well as their distinct regulatory frameworks and tax policies that aim at promoting digital asset activities and attracting both investors and businesses operating within the crypto ecosystem. The tax treatment of digital assets varies across these countries, while most of them apply either income tax, CGT, or a combination of both, depending on the nature of the crypto transaction. Furthermore, each jurisdiction permits specific cost basis methods such as first-in-first-out (FIFO), specific identification (SI), weighted average cost (WAC), highest-in-first-out (HIFO), or last-in-first-out (LIFO) for calculating the acquisition (buy) value of the disposed crypto assets for tax reporting purposes.

Table 1.

Comparative overview of digital asset taxation across selected jurisdictions [24,25,26].

Most of these jurisdictions support FIFO as the preferred accounting approach for computing the disposal events. The FIFO method establishes a systematic mapping between acquisition (buy) and disposal (sell) transactions to determine the presence and magnitude of capital gains or losses. Hence, due to its widespread adoption and the specific guidelines issued by SARS, the implementation of the proof-of-concept proposed by this research study adopts FIFO as the default system configuration for computing tax liabilities.

The following subsection explores the existing Blockchain forensic tools and techniques that can be used to investigate illicit activities within the crypto space.

3.2. Blockchain Forensics Tools and Techniques

Blockchain forensics builds upon the foundational principles of digital forensics [27]. However, their concepts are distinct since Blockchain Forensics focuses on investigating Blockchain-based activities by examining Blockchain data to uncover evidence of illicit activities such as fraud, money laundering, and cybercrimes [27]. The research interest in Blockchain forensics has expanded significantly in recent years, with the foundational work by [28] that has pioneered the method of address clustering within the Bitcoin network, demonstrating how pseudonymous wallet addresses could be linked through transaction patterns to identify suspicious or fraudulent activities. Similarly, a study by [29] expanded on this work and applied transaction flow analysis to detect fraud and other illicit activities, illustrating how the transparency of Blockchain records can be leveraged for investigation purposes.

Building on these early efforts, subsequent studies such as [30] have provided comprehensive taxonomies and systematic reviews that seek to classify the existing Blockchain forensic tools, their methodological foundations, and domains of application. Despite these advancements, the authors noted that commercial implementations such as Chainalysis, CipherTrace, Elliptic, Maltego, TRM Labs, and Breadcrumbs have predominantly concentrated on AML and the detection of cybercrimes within the crypto ecosystem. There is limited evidence regarding the adoption or integration of Blockchain forensics techniques into systems that facilitate voluntary and proactive tax compliance for everyday CAHs. Given that Blockchain forensics has traditionally been deployed as a reactive investigative tool, its proactive application as a compliance enabler within the tax domain remains underexplored [28,29,30]. This creates a clear gap between post-incident investigation and proactive, real-time verification during filing or submission of the crypto obligations.

Note that this study views most of these Blockchain forensics solutions as reactive, because their investigative mechanisms seek to react to an incident that has occurred, while this study seeks to use the Blockchain forensic concept as a proactive mechanism to investigate crypto wallet interactions during the process of filling crypto-related tax obligations to uncover any illegal related connections or activities. This process also involves the comparison of the wallet interactions with an aim of connecting the wallet used to either send or receive digital assets with those that have been flagged or banned addresses to detect links to scams, money laundering, and terrorist financing-related activities.

The following subsection focuses on the concepts that outline the regulatory solutions associated with crypto taxation.

3.3. Regulatory Technology and Automation for Compliance

Similarly, RegTech has evolved rapidly, aiming to apply digital innovations to meet complex regulatory compliance requirements. The study by [31] was instrumental in defining the evolution of RegTech and outlining its potential to transform regulatory reporting through digital automation. Building on this conceptual model, the study by [7] examined how smart contracts could be designed to enforce compliance automatically, suggesting that the coding of legal rules, not Blockchain-based protocols, holds promise for transparent, tamper-proof governance. Studies performed by [32,33] have proposed that Blockchain could be leveraged for tax reporting and collection; however, these proposals largely remain at the conceptual phase and lack context-specific proof-of-concept implementations, especially in developing countries. Most of the existing solutions associated with RegTech focus on institutional-level compliance and financial market supervision rather than individual tax obligations. However, many of these solutions or models do not include robust forensic validation layers to ensure the integrity of the reported data, and they often require costly subscriptions, creating barriers to access for taxpayers in resource-constrained contexts. This reveals a second critical gap, which can be associated with the absence of locally adaptable, cost-effective RegTech models that incorporate Blockchain forensics to ensure both compliance and verification. RegTech innovations, including the use of smart contracts and automated reporting, promise to reduce compliance burdens for regulatory authorities [32]. Moreover, the emerging applications of NFTs as tamper-proof data anchors also offer novel mechanisms for enhancing the verifiability of tax records. Note that all these concepts, i.e., smart contracts and NFTs, are also incorporated within the proposed model and explored later on in Section 4.

The following section presents an overview of the crypto-related taxation frameworks.

3.4. Crypto Taxation Framework

Various studies that seek to address digital asset taxation issues have expanded as policymakers worldwide are grappling with classification and taxing a diverse range of crypto transactions. The study by [15], along with [5], has provided a global overview of how different jurisdictions approach the taxation of digital assets, highlighting policies and concepts that often lead to regulatory arbitrage. The study by [20] further investigates the legal classification of digital assets, analysing their implications for accounting and taxation practices across multiple jurisdictions. In South Africa, SARS has clarified the tax treatment of capital gains and income derived from digital assets; however, they remain ambiguous on emerging activities such as staking rewards, DeFi interest, and NFT royalties. The studies by [9,34] also confirmed this notion by examining SARS’s current guidance and found that it is both incomplete when it comes to clarifying transactions such as airdrops, initial coin offerings, NFTs, Blockchain forks, DeFi activities, and theft losses [11]. Despite these issues, SARS has repeatedly cautioned that a significant portion of the South Africans who engage in crypto trading or investment have not been declaring these activities for tax purposes. The SARS [13] media release of 9 October 2024 raises these concerns about the widespread non-declaration because it has reported that more than 5.8 million South Africans hold crypto assets.

All this literature collectively provides meaningful insight into the global treatment of digital assets, the evolution of Blockchain forensics, the emergence of regulatory technology, and the diverse tax approaches adopted by various jurisdictions. However, the literature also reveals some of the shortcomings that might constrain the feasibility of applying these concepts directly to practical crypto-tax compliance scenarios, particularly within the South African context. Hence, the following subsection synthesises these shortcomings and outlines the key limitations inherent in the identified research gaps.

3.5. Limitations of the Identified Research Gaps

The following items outline the major limitations that persist within existing research on Blockchain forensics, RegTech, and crypto-asset taxation.

- Reactive focus of Blockchain forensics. The current Blockchain forensics research remains predominantly reactive and AML-oriented. Its foundational studies focus on clustering, taint analysis, and illicit detection, but these methods have not been adapted for routine taxpayer self-reporting or integrated into automated compliance workflows.

- RegTech models lacking taxpayer-centric design. Although RegTech literature highlights opportunities for automation, smart contracts, and policy-as-code, most of these models target institutional reporting and financial market supervision rather than individual taxpayer compliance. The existing frameworks do not provide mechanisms to validate the integrity of self-reported crypto-asset data or reconcile disclosures with on-chain evidence, thereby limiting their applicability to crypto tax administration.

- Fragmented global tax classifications. The global crypto-tax literature suffers from inconsistent classifications, definitions, and cost basis rules across jurisdictions. As discussed in Section 3.1, various countries diverge significantly in defining digital assets, identifying taxable events, and selecting cost-basis methods. These inconsistencies complicate data standardisation, hinder taxpayer compliance, and weaken the interoperability of cross-border regulatory frameworks.

- Inadequate treatment of emerging activities. As outlined in Section 3.4, the current tax frameworks inadequately address emerging activities such as DeFi lending, liquidity pools, staking rewards, airdrops, hard forks, and NFT transactions. In South Africa and many other jurisdictions, guidance remains incomplete or ambiguous, creating structural uncertainty for taxpayers and complicating auditability, while the literature highlights these descriptive gaps, it rarely proposes technically grounded mechanisms to resolve them.

- Absence of verifiable audit mechanisms. The existing research does not provide mechanisms for the tax authority to independently validate the accuracy of crypto-asset declarations against underlying Blockchain evidence. The lack of tamper-resistant, verifiable audit anchors leaves tax systems reliant on voluntary disclosures, despite the availability of on-chain forensic data that could support automated verification.

- Underdeveloped privacy-preserving mechanisms. Privacy-preserving techniques remain limited. Although some studies address pseudonymity or cryptographic primitives such as hashing, selective disclosures, and zero-knowledge proofs, these approaches have not been operationalised to balance transparency with taxpayer privacy when public Blockchains are used as compliance infrastructures.

This subsection has outlined the main limitations that persist across the literature on digital assets, Blockchain forensics, RegTechs, and crypto-asset taxation. These gaps demonstrate the need for a more integrated, verifiable, and privacy-preserving approach to crypto tax compliance. Accordingly, the following section presents the proposed conceptual model, which expands upon prior work by incorporating digital forensics, automated cost-basis computation, and the use of crypto tax NFTs as verifiable audit anchors.

4. Proposed Conceptual Model

This section is divided into two subsections, namely: the previously proposed model and the extended conceptual model. The previously proposed model subsection presents the foundational model for crypto-asset taxation, which outlines the role of key actors and processes associated with crypto-asset tax reporting. The extended conceptual model subsection expands upon this foundation by incorporating the creation of crypto tax NFTs, as well as the advanced Blockchain features such as decentralised storage, smart contract logic, and digital forensics. Note that the extended model strengthens the verification mechanisms, enhances tamper-proofing, and provides regulators with higher levels of auditability and compliance assurance.

4.1. Previously Proposed Model

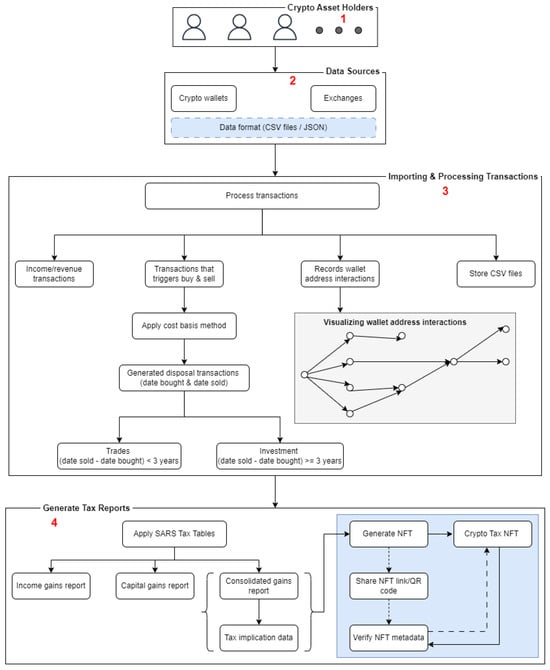

Figure 1 illustrates the foundational conceptual model [11], which involves the following actors:

Figure 1.

Previously proposed model. The numbering from 1–4 depicts the key components of the foundational model, including the actors, data sources, transaction-processing workflows, and generate tax reports mechanisms introduced in the initial design. These numbered labels correspond to the major functional blocks highlighted in the diagram and provide a structured overview of the model’s core operational components..

- CAHs: taxpayers who directly engage in crypto transactions and fulfil their tax obligations.

- Tax practitioners: third-party professionals responsible for filing tax obligations on behalf of CAHs.

- CASPs: businesses such as Binance, Kraken or Luno, which facilitate crypto transactions and custodial services.

- Crypto asset businesses (CABs): organisations that accept or hold crypto assets for operational purposes. For example, “Pick ’n Pay” retail store in South Africa enables customers to pay for goods using digital assets, e.g., Bitcoins [35].

All these actors source their crypto-related historical data from either crypto wallets or exchanges. These data are then imported into the proposed model using either CSV or JSON format, which can be accessed through file downloads or API keys integration. Once these data are successfully imported, then the model uses the processed data to compute both income tax (from short-term trades or revenue-generating activities) and capital gains tax (from long-term investments and asset disposals), as depicted in label 3 of Figure 1. Note that all the processed transactions are computed using the SARS-approved cost basis methods (e.g., FIFO or SI) to determine the disposal events. These disposal events are classified into two categories, namely: trades (short-term investment held for less than 3 years) and investments (long-term investment held for 3 years or more). Additionally, label 3 of Figure 1 also illustrates how crypto wallet address interactions are recorded and visualised to identify connections with flagged or sanctioned addresses.

Label 4 of Figure 1 presents how the model generates various tax reports, applying SARS tax tables to compute both income and capital tax liabilities. The outcomes of these computations are classified into two categories, namely: income-related transactions (which depict the short-term investments and revenue-generating activities), and capital-related transactions (which are based on the long-term investments, and other transactions related to spending or gifting digital assets). These results produce two distinct report outputs: the income tax report and the capital gains tax report, which are then merged into a consolidated tax report. The consolidated tax report provides regulators with a holistic view of a taxpayer’s obligations and compliance metadata. Note that this metadata also forms part of the embedded information utilised during the generation of crypto tax NFTs, serving as verifiable proof of compliance. As indicated in label 4 of Figure 1, the process of generating tax reports incorporates the creation of crypto tax NFTs, which only outlines a high-level overview of the concepts involved. Hence, the following subsection seeks to expand upon this prior foundational research by presenting an extended model that details the processes and technologies involved in securely generating crypto tax NFTs as a verification mechanism.

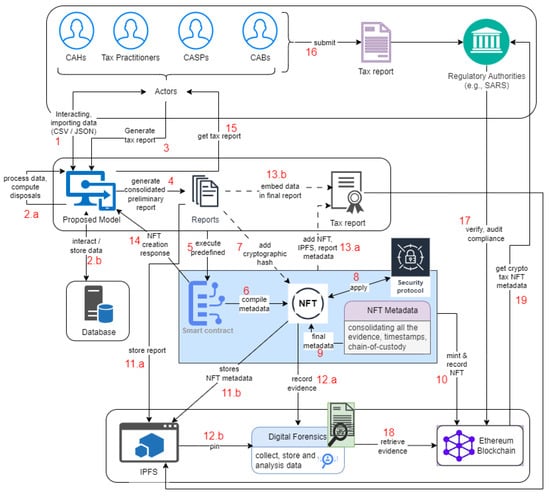

4.2. Extended Conceptual Model

Building on the foundational model outlined in the previous section, the extended conceptual model (depicted by Figure 2) introduces advanced processes that might be used for generating crypto tax NFTs securely. Therefore, to avoid repeating some of the concepts that were already discussed in the previous section, this study focuses more on the components that were not discussed and only touches base on the previous components when it is necessary to do. The extended model integrates the following components: Blockchain networks, smart contracts, decentralised storage, and digital forensics to enhance traceability, authenticity, and regulatory compliance verification of the tax reports submitted by the taxpayer. Therefore, the following steps present chronological processes used by this study to unfold how various components and actors of the proposed solution interact with each other within the extended model, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Proposed model expansion: Focusing on the creation of NFTs. The numbering from 1 to 19 depicts the processes described in Steps 1–19. These annotations indicate the flow of data, tax-computation stages, smart-contract interactions, NFT-minting operations, and the associated verification points within the extended conceptual model.

- Step 1: Depict relevant actors (e.g., CAHs, tax practitioners, CASPs, or CABs), initiate the interaction with the proposed model by importing historical transaction data from CASPs (e.g., crypto wallets or exchanges).

- Step 2: Upon successful data ingestion, the proposed model consolidates the imported data and initiates tax computation workflows (depicted by step 2 in Figure 2). Note that this process also seeks to standardise the imported data and compute disposal events using SARS-approved cost basis methods (i.e., FIFO). This allows the proposed mode to interact with the database by storing or retrieving processed data.

- Step 3: Once the imported data are processed successfully, the proposed model enables the actor to submit a request to generate a tax report associated with a particular fiscal period.

- Step 4: Depicts a process that generates a consolidated preliminary report, which enables the proposed model to identify taxable events that can be used to extract both income and capital gains tax metadata. Additionally, this process also involves recording of crypto wallet addresses used to either send or receive digital assets, as well as performing wallet clustering and address attribution based on the known risk indicators from publicly available sanctions lists and illicit activity reports, such as ransomware clusters, mixer pools, scam or fraud wallets. This results in visualising the crypto wallet address interactions to identify connections with flagged or sanctioned addresses, as shown in label 3 of Figure 1.

- Step 5: Present a process that uses the preliminary tax report inputs to execute a smart contract, which initiates the tokenisation process that results in a crypto tax NFT.

- Step 6: Depict a smart contract compiling essential metadata required for NFT creation, which includes a cryptographic hash of the tax report, a pseudonymised or hashed identifier for the taxpayer, the applicable tax year and system timestamp, as well as the unique internal system-generated reference ID for traceability.

- Step 7: The process that enables the proposed model to generate a cryptographic hash of the tax report to serve as a tamper-proof digital fingerprint. This cryptographic hash of the tax report is also appended to the NFT metadata.

- Step 8: Depicts a process that seeks to add additional security mechanisms, such as digital signatures, hash locks, or Merkle roots, that are applied to enhance the authenticity and data integrity of the report.

- Step 9: Represent a process that compiles a comprehensive metadata structure, incorporating timestamps, evidence trails, hash values, wallet address risk score, and chain-of-custody details for regulatory verification purposes. Note that all this metadata will be embedded as pseudonymised indicators to support regulatory review without exposing sensitive information.

- Step 10: Following metadata finalisation and security validation, the NFT is minted on a public Blockchain (e.g., Ethereum), ensuring immutability and global verifiability of the tax report. This study adopts the Ethereum Blockchain network, which supports the ERC-721 standards for its metadata.

- Step 11: The associated tax report and NFT metadata are stored off-chain using the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), and a unique IPFS content identifier (CID) is generated, which provides a link between on-chain data stored in the Ethereum network, and off-chain data stored in the internal database and IPFS.

- Step 12: During the process of storing data to an IPFS, a dedicated forensic module is used to log digital forensic evidence. This forensic evidence includes a recording of the following information: smart contract version histories, cryptographic hashes, NFT minting proofs, and the IPFS CIDs, to ensure tamper detection and traceability for future audits. Note that all the critical data elements (e.g., NFT metadata, IPFS CID, and report hashes) are redundantly stored across multiple platforms, such as the Ethereum network (on-chain), IPFS (off-chain), and an internal database.

- Step 13: All the metadata and forensic evidence collected from various components are appended to the final tax report, creating a compliance-ready package. This final tax report package is then made available for authorised actors to download and submit it to the relevant authority.

- Step 14: Depicts a process that enables the smart contract to respond to the request made by the proposed model regarding the NFT creation.

- Step 15: The proposed model allows the actor to download the finalised tax report that consists of all the necessary metadata required for the regulatory authority to securely and independently verify the authenticity of the submitted report.

- Step 16: After the authorised actor has successfully downloaded the tax report, he then submits it to the relevant tax authority (e.g., SARS).

- Step 17: The regulatory authority initiates a process that seeks to verify or validate the tax report submitted by the taxpayer by cross-referencing the embedded NFT metadata with the submitted tax report, establishing a first layer of authenticity.

- Step 18: A comprehensive audit process is conducted by retrieving the original tax report from the IPFS, verifying the forensic logs, cross-checking timestamps, and confirming NFT minting proofs. These verification steps enable the regulatory authorities, e.g., SARS, to assess the tax report’s integrity and authenticity with high confidence.

- Step 19: Depicts a process whereby the regulatory authority, e.g., SARS, obtains the final corresponding results associated with the crypto tax NFT.

As indicated in Figure 2, a smart contract can be viewed as the core component of the extended model, and it is a self-executed programme or logic triggered by certain requirements. These requirements form part of the metadata (i.e., report hash, tax year, timestamp, IPFS CID, and user hashed ID) as discussed in the above steps. Hence, the smart contract receives a MintInput payload containing only the metadata required for cryptographic verification, to avoid exposing sensitive personal information on-chain. Note that the MintInput payload is associated with step 9, while step 10 confirms that all the requirements have been met and the smart contract can proceed to use the mintTaxNFT(MintInput) function to mint the crypto tax NFT. This study conceptualises the MintInput payload as:

MintInput = {

reportHash,

taxpayerIdHash,

taxYear,

filingPeriod,

jurisdictionCode,

costBasisMethod,

ipfsCid,

systemReferenceId,

timestamp,

signerPublicKey

}

The proposed solution is not yet integrated with the SARS eFiling system, even though the effort of this research is working towards achieving this desirable goal. However, the finalised tax report generated by the proposed solution can be used as proof of crypto asset declarations, as well as outlining how crypto gains and losses were calculated. Therefore, for a taxpayer to be able to declare their crypto assets using SARS eFiling platform, they have to perform certain checks that will allow them to submit the tax report as proof for their crypto asset declarations. These checks can be found under the Comprehensive tab, within the Capital Gain/Loss section [19]. After successfully uploading the finalised report, the regulatory authority, e.g., SARS in this case, will independently assess the tax report and use a read-only function, as explored during steps 14–15, to verify the details submitted by the taxpayer using the following report function:

verifyReport(tokenId, reportHash) → boolean

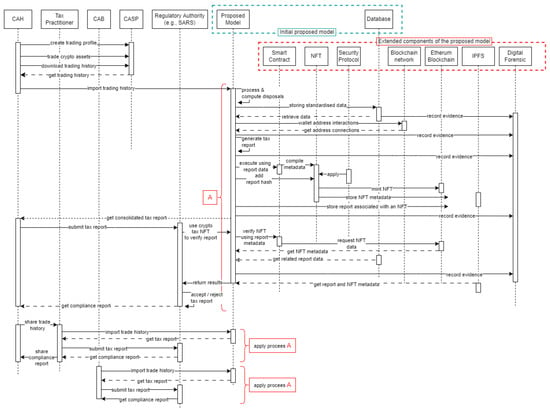

Figure 3 present a sequence diagram that visualises all the processes or steps involved in the proposed model to achieve the desirable objectives.

Figure 3.

Proposed model sequence diagram. Label “A” represents the process flows triggered when a CAH imports crypto-asset transactions into the proposed model. This sequence of events begins with the ingestion, processing, and computing of transactions or disposals, and proceeds to the generation of a crypto tax report, which is subsequently submitted to the regulatory authority (e.g., SARS) for verification of its authenticity. The same sequence of events applies when the transactions are imported by a tax practitioner or a CAB, hence the use of the notation “apply process A” to avoid duplicating the same procedural steps.

This section has demonstrated how the integration of Blockchain technology, decentralised storage, NFTs, and digital forensics can significantly enhance the auditability, security, and regulatory reliability of crypto tax reporting. By enabling the systematic generation of crypto tax NFTs, the extended model allows both taxpayers and regulatory authorities to operate within a verifiable and tamper-proof compliance ecosystem. Building on this foundation, the following section presents the analysis and synthesis of the proposed model in comparison with existing solutions and related academic contributions.

5. Analysis and Synthesis

This section explores the comparative analysis of the existing solutions and the synthesis of the related academic contributions. First, the following subsection explores the evaluation of the existing solutions as compared to the proposed conceptual model, while the subsection following that focuses on the synthesis of the related academic contributions compared to the proposed model.

5.1. Evaluation of the Existing Solutions vs. Proposed Model

This section provides a systematic comparative analysis of the existing solutions (i.e., operational systems, commercial tools, and conceptual models) to identify opportunities and gaps that motivate a unified and integrated solution. This study classifies these existing solutions into three categories, namely [11]:

- Global tax tools—these are consumer-oriented crypto tax calculators used by CAHs to generate the required tax report that can be submitted to the regulatory authorities during the process of filing tax obligations. Some of these notable solutions include CoinLedger, Recap, Kryptos, CryptoTaxCalculator, CoinPanda, and Koinly, as discussed in [11].

- Blockchain forensic solutions—these are enterprise solutions such as Chainalysis, CypherTrace, Elliptic, Maltego, TRM Labs, and Breadcrumbs, that perform clustering, tracing, attribution, and risk scoring aligned to AML or CFT expectations [28,29]. These tools are powerful for post-incident investigations but are not embedded in taxpayer filing workflows and generally do not compute tax outcomes for CAHs. Hence, these solutions employ sophisticated techniques primarily for investigative purposes, rather than the issues faced by taxpayer during the process of filing their crypto tax obligations.

- RegTech solutions—these solutions leverage policy-as-code or smart contracts to automate elements of regulatory reporting, while they show promise for rule execution and workflow automation, they often lack integrated forensic verification to reconcile declarations with on-chain reality and are seldom tailored to SARS forms, periods and evidentiary requirements.

Table 2 illustrates the comparative perspective by benchmarking the key features of representative global tax tools, Blockchain forensic solutions, and RegTech models against the features of the concepts proposed in Section 4. Note that the conceptual model presents a solution that might be used to address crypto tax compliance issues. This model incorporates concepts such as automation, transaction tracing, and tamperproof verification mechanisms. Additionally, the proposed conceptual model also seeks to provide an integrated, cost-free solution that automates cost-based calculations aligned with the South African context, which is based on the SARS tax rules.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of existing solutions vs. the proposed model. Note that the symbol “✓” indicates that the feature is supported, while “✗” indicates that the feature is not supported.

All these criteria emphasise that the current existing solutions lack most of the features that can enable taxpayers to voluntarily declare their crypto obligations without facing obstacles. Even though this study acknowledges that the global tax tools also offer an alternative solution that might be used by CAHs to generate their tax reports. However, the regulatory authorities, such as SARS, rely heavily on voluntary disclosure, and annual self-filing means that CAHs bear the burden of accurate reporting, and the subscription fees attached to these solutions deter the CAHs who have made little fortune to pay the prescribed amount in order to generate the required tax obligation report by SARS.

This section benchmarked the existing solutions, with tax tools calculations without verification, forensic suites investigation without filing integration, and RegTech models automated without localisation or assurance. Therefore, the following section focuses on the academic contributions and examines how prior research addresses some of these gaps.

5.2. Synthesis of Related Academic Contributions

This subsection synthesises how prior research has engaged with Blockchain forensics, tax automation, RegTech, smart contracts, and NFTs. The objective is to position this study within the broader academic discourse and to highlight persisting gaps that motivate the proposed model, rather than stating this study’s contributions.

Table 3 presents a comparative analysis of the academic contributions in line with these five dimensions: Blockchain forensics, tax automation, smart contracts, hllocal contextualisation, and NFTs. It further identifies the limitations of each study, illustrating the extent to which existing efforts have advanced conceptual frameworks but have not translated into integrated, taxpayer-oriented solutions.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of academic contributions. Note that the symbol “✓” indicates that the study supports the feature, while “✗” indicates that the study does not include the feature.

Various studies highlight that the pseudonymous, borderless nature of Blockchain undermines the conventional tax systems that rely on centralised intermediaries and clearly defined national jurisdictions [7]. Despite this growing body of work, most of the proposed solutions remain largely descriptive, offering conceptual insights without providing integrated, operational models that link taxpayer self-reporting to Blockchain-verified data. This gap underscores the need for a more comprehensive, technically grounded approach that bridges forensic analysis, regulatory technology, and practical tax-compliance mechanisms. Building on this identified gap, the following section outlines the key research contributions of this study.

6. Research Contribution

This study makes significant contributions at both academic and practical levels. The academic contributions are classified into three categories:

- Theoretical—it reconceptualises digital forensics concepts from being primarily an investigative AML tool into an active, proactive mechanism for routine crypto tax compliance. This theoretical shift broadens the scope of Blockchain forensics, embedding it within fiscal governance and taxpayer self-reporting.

- Practical—it proposes a robust, locally adapted proof-of-concept model tailored to South Africa’s context. It aligns fully with SARS’s cost basis methods while addressing emerging transaction types such as staking, DeFi, and NFT activities. This ensures both regulatory relevance and practical applicability for diverse taxpayer scenarios.

- Innovative—it introduces the use of NFTs as verifiable audit anchors. By embedding cryptographic metadata into NFTs, the model enhances trust, ensures tamper-proof integrity, and creates an immutable audit trail for self-reported tax data, strengthening transparency and accountability in tax governance.

Beyond these academic contributions, this study also positions itself at a crucial intersection between Blockchain forensics, RegTech, and tax compliance, which results in practical, applicable contributions:

- Linking digital forensics and tax compliance—by extending the application of Blockchain forensic methods to routine tax reporting and not just criminal investigations, it redefines the role of digital forensics in fiscal governance.

- Verification compliance through NFTs—adds a verifiable audit layer that enables regulatory bodies, e.g., SARS, to independently validate tax submissions, bridging trust gaps between taxpayers and regulators.

- Automation within local rules—unlike generic global calculators, the proposed model is designed to fully align with SARS-specific cost basis methods and distinguish between income and capital gains, ensuring contextual compliance. Note that this research also aimed at presenting the proof of concept to SARS, with the hope that it can be adopted and integrated into their e-filing platform.

- Scalable and cost-free—By prioritising a subscription-free, automated proof-of-concept, the model addresses the practical barriers that deter small-scale taxpayers or CAHs from fulfilling their crypto-related tax obligations, which enhances inclusivity and voluntary compliance.

While these contributions position the proposed model as a promising and locally relevant solution for crypto tax compliance, its successful real-world implementation requires careful consideration of broader contextual factors. In particular, technological innovation alone is insufficient without accounting for the privacy implications of anchoring compliance metadata on public Blockchains, as well as the diverse adoption challenges faced by taxpayers, tax authorities, and CASPs. These concerns are fundamental to ensuring that the model is not only technically robust but also socially acceptable and operationally viable.

7. Privacy Considerations and Adoption Barriers

The practical implementation of the proposed model requires a systematic analysis of the following two critical issues that extend beyond technical design: protecting taxpayer privacy when cryptographic metadata are anchored on a public Blockchain, and understanding the adoption motivations and potential barriers faced by taxpayers, tax authorities, and CASPs. These aspects are essential for ensuring that the model is not only technically sound but also socially acceptable, operationally feasible, and institutionally sustainable.

7.1. Privacy Risks Associated with Public Blockchain Anchoring

Although the proposed model incorporates hashing, pseudonymisation, and off-chain storage to mitigate direct exposure of taxpayer information, anchoring verification metadata on a public Blockchain inevitably introduces residual privacy risks. These risks arise from the transparent, immutable, and globally accessible nature of public ledgers. Three notable privacy concerns include:

- Pattern recognition and behavioural inference: even without explicit personal identifiers, observable metadata, such as transaction timings or recurring interactions with a verification smart contract, may allow adversaries to infer taxpayer behaviour. Over time, such interactions may form behavioural fingerprints that reveal filing habits or trading frequency.

- Cross-contextual linkage and re-identification: public Blockchain metadata (e.g., event logs, timestamps, or IPFS content identifiers) can be correlated with external datasets such as leaked exchange records, Blockchain analysis clusters, or network-level identifiers. This cross-dataset correlation increases the risk of re-identification, thereby undermining the intended pseudonymity of taxpayers.

- Longitudinal traceability: immutability of public ledgers ensures that all the interactions with smart contracts remain visible indefinitely. Over time, patterns emerging from NFT issuance, hash submissions, or smart contract interactions may enable inference attacks capable of deanonymising pseudonymised identifiers.

To mitigate these risks, several advanced privacy-preserving techniques may be considered, which include

- a.

- The use of zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) to verify tax-report authenticity without exposing underlying data.

- b.

- Commit–reveal protocols to decouple the timing of tax computations from on-chain minting events.

- c.

- Periodically rotating pseudonymous identifiers to prevent long-term behavioural correlation.

- d.

- Utilisation of privacy-preserving layer-2 rollups, where metadata exposure is significantly reduced compared to base-layer public chains.

All these mechanisms can be adopted to enhance the privacy posture of the proposed model and reduce the risk of inference-based attacks.

7.2. Adoption Barriers Across the Compliance Ecosystem

The effectiveness of the proposed model relies on its adoption by three key stakeholders: taxpayers, tax authorities, and CASPs. Each of these stakeholders exhibits unique incentives, constraints, and operational realities that shape their readiness to adopt a Blockchain-based tax verification solution.

- Taxpayer adoption considerations: the majority of taxpayers lack the technical literacy necessary to interact with NFT-based audit trails, IPFS-linked metadata, or Blockchain-anchored attestations. Some of the concerns that might reduce voluntary adoption include privacy exposure, misunderstanding of cryptographic proofs, and unfamiliarity with Blockchain mechanisms. Furthermore, gas fees, even when they are relatively low, may pose a financial barrier for small-scale traders. Despite these challenges, the model offers clear incentives: automated disposal-event computation, simplified reporting processes, and reduced audit disputes, all of which may encourage adoption once adequate education and support structures are in place.

- Tax authority readiness and institutional constraints: For tax authorities such as SARS, adoption depends on alignment with institutional mandates, compatibility with existing audit workflows, and the legal recognition of cryptographic attestations. Integrating Blockchain-based verification tools may require procedural reforms, staff capacity building, and the establishment of standards for evaluating cryptographic artefacts. Additionally, regulatory uncertainty regarding the admissibility of NFTs or hash-anchored proofs in legal audits may impede institutional adoption.

- CASP integration challenges: Local CASPs may face additional compliance burdens associated with generating standardised datasets, maintaining risk-assessment metrics, or enabling API-based interactions with the proposed model. Foreign CASPs, particularly those outside South Africa’s regulatory perimeter, may be unwilling or unable to provide structured and standardised data, exacerbating the existing interoperability and data-harmonisation challenges.

A comprehensive understanding of the privacy considerations and adoption barriers discussed above is essential for advancing the proposed conceptual model from theoretical feasibility to real-world operational readiness. Building on this foundation, the following section reflects on the broader limitations and shortcomings of the study, acknowledging factors that may influence the interpretation, applicability, and future refinement of the model.

8. Limitations and Shortcomings of the Study

This study acknowledges that there are several limitations that can be associated with technical constraints, methodological boundaries, and design assumptions of the proposed model. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the results and assessing the feasibility of future implementation.

- Privacy preservation mechanisms: Although hashing and pseudonymisation are employed, the model does not implement advanced privacy-preserving cryptographic techniques such as zero-knowledge proofs. Future work should incorporate such mechanisms to strengthen privacy guarantees.

- Cost and variability of NFT minting fees: The reliance on public Blockchain networks introduces variable gas fees, which may limit accessibility for low-income or small-scale taxpayers. Layer-2 Blockchain roll-ups and alternative networks remain unexplored.

- Environmental considerations: Despite Ethereum’s shift to proof-of-stake, Blockchain interactions still incur environmental and computational costs, warranting further investigation of sustainable alternatives.

- Long-term data availability: While IPFS provides decentralised storage, long-term persistence is not guaranteed unless data are continuously pinned, creating potential reliability concerns.

- Lack of standardisation: The absence of formal standards for NFT-based tax-report metadata limits the immediate interoperability of the model with existing regulatory frameworks.

These limitations highlight technical and methodological areas requiring refinement in future prototype implementations.

9. Conclusions

This study has examined the intersection of Blockchain forensics, RegTech and crypto asset tax compliance, with a specific focus on the South African regulatory landscape. Through a critical review of the current global practices and forensic capabilities, the research has highlighted the unique challenges posed by pseudonymous, cross-border crypto transactions and the limitations of conventional tax enforcement tools. To address these gaps, this study proposed a conceptual model that leverages Blockchain forensics and NFTs to ensure the integrity, traceability, and verifiability of the crypto tax report submitted by the taxpayer.

The integration of smart contracts and decentralised storage within the proposed model offers a transformative approach to automating compliance, mitigating fraud, and enhancing transparency for tax authorities. By assigning tamper-evident NFTs to cryptographically hashed tax reports, the proposed model not only preserves evidential integrity but also creates an immutable audit trail. Ultimately, this research contributes to the growing discourse on RegTech solutions for digital taxation and opens new avenues for implementing Blockchain forensic solutions within the crypto tax administration space.

Future research focuses on the systematic design and implementation of the proposed model by developing a functional prototype that serves as proof-of-concept. To ensure that the proposed model aligns with SARS requirements, the prototype will be developed using standardised, regulator-acceptable data structures, and it will also adopt some of the concepts used within the shares or commodity disclosure. As part of the dataset preparation process, the researchers have already created trading profiles across several licenced South African CASPs and executed multiple real-world transactions to obtain representative datasets. These datasets, together with publicly available Blockchain records and synthetic transaction histories, will be imported into the prototype using CSV or JSON formats and standardised before computation. The following phases will be used to develop and evaluate the proposed solution:

- Phase 1: Importing, processing, and computing transactions. These are the development functions or components used to import data collected from various CASPs and the Blockchain network with an aim of standardising the data used by the proposed model. Once the transactions have been processed successfully, an implementation of a component that computes disposal events using SARS-approved cost basis methods (e.g., FIFO and SI) should be triggered automatically.

- Phase 2: Implement the reporting component that seeks to utilise the processed transactions and disposal events to generate a tax report that will be submitted to SARS as part of declaring digital or crypto assets.

- Phase 4: Smart contract development, forensic engine integration, NFT minting, and IPFS integration. it involves the creation of the NFT contract, metadata schema, and verification function, while the forensic element incorporates wallet address clustering, taint analysis, and risk scoring into the compliance workflow. An additional component will be an implementation of off-chain storage using IPFS, generation of IPFS CIDs, and linking these data to on-chain NFT metadata.

- Phase 5: Prototype testing and evaluation. involves a comprehensive assessment using synthetic scenarios and real CASPs transaction data to validate readiness for regulatory engagement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T.R. and H.V.; methodology, P.T.R.; validation, P.T.R. and H.V.; formal analysis, P.T.R.; investigation, P.T.R.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T.R.; writing—review and editing, P.T.R. and H.V.; visualization, P.T.R.; supervision, H.V.; project administration, P.T.R.; funding acquisition, P.T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research study was supported by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) and the University of Pretoria (UP). Special thanks go to H.S. Venter (UP) for his continuous support and contributions towards the success of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SARS | South African Revenue Service |

| RegTech | Regulatory technology |

| NFTs | Non-fungible tokens |

| DeFi | Decentralised finance |

| ML | Money laundering |

| AML | Anti-money laundering |

| TF | Terrorist financing |

| CTF | Counter-terrorism financing |

| CAHs | Crypto asset holders |

| FATF | Financial Action Task Force |

| CASPs | Crypto asset service providers |

| CABs | Crypto asset businesses |

| CGT | Capital gains tax |

| FIFO | First-in-first-out |

| LIFO | Last-in-first-out |

| HIFO | Highest-in-first-out |

| WAC | Weighted average cost |

| SI | Specific identification |

| OECS | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| USA | United States of America |

| IRS | Internal Revenue Service |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates |

| IPFS | Inter-Planetary File System |

| CID | Content identifier |

References

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. 2008. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Catalini, C.; Gans, J. Some simple economics of the blockchain. Commun. Acm 2020, 63, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, M. Blockchain: Blueprint for a New Economy; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, S.; Karlsen, J.; Putniņš, T. Sex, drugs, and bitcoin: How much illegal activity is financed through cryptocurrencies? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 1798–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxing Virtual Currencies: An Overview of Tax Treatments and Emerging Tax Policy Issues. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/topics/policy-issues/tax-policy/flyer-taxing-virtual-currencies-an-overview-of-tax-treatments-and-emerging-tax-policy-issues.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- 12-Month Review of the Revised FATF Standards on Virtual Assets and Virtual Asset Service Providers. Available online: https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/publications/Fatfrecommendations/12-month-review-virtual-assets-vasps.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Zetzsche, D.; Arner, D.; Buckley, R. Decentralized finance. J. Abbr. 2020, 6, 172–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryptocurrency Penetrates Key Markets in Sub-Saharan Africa as an Inflation Mitigation and Trading Vehicle. Available online: https://www.chainalysis.com/blog/africa-cryptocurrency-adoption/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Vumazonke, N.; Parsons, S. An analysis of South Africa’s guidance on the income tax consequences of crypto assets. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2023, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurisdictions Under Increased Monitoring—13 June 2025. Available online: https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/publications/High-risk-and-other-monitored-jurisdictions/increased-monitoring-june-2025.html (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Ramazhamba, P.T.; Venter, H.S. Conceptual Model for Taxation and Regulatory Governance among South African Crypto Asset Holders. In Proceedings of the ISSA Conference, Gqeberha, South Africa, 2 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Exchange Control Circular No 2/2025 Statement on Exchange Control. Available online: https://www.resbank.co.za/content/dam/sarb/what-we-do/financial-surveillance/financial-surveillance-documents/2025/2-2025.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Media Release: SARS Warns About Crypto Asset Compliance. Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/latest-news/media-release-sars-warns-about-crypto-asset-compliance/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Ramazhamba, P.T.; Venter, H.S. Using distributed ledger technology for digital forensic investigation purposes on tendering projects. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2023, 15, 1255–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, T.; Yılmaz, G. Taxation of Virtual/Crypto Assets/Currencies. Sosyoekonomi 2022, 30, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crypto Taxes: Expert USA Guide 2025. Available online: https://koinly.io/guides/crypto-taxes/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Lazea, G.; Balea-Stanciu, M.; Bunget, O.; Sumănaru, A.; Coraș, A. Cryptocurrency Taxation: A Bibliometric Analysis and Emerging Trends. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2025, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consultation Paper on Policy Proposals for Crypto Assets. Available online: https://www.ifwg.co.za/IFWG%20Documents/IFWG_CAR_WG-Position_Paper_on_Crypto_Assets.pdf#search=consultation%20paper%20on%20crypto%20assets (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Crypto Assets & Tax. Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/individuals/crypto-assets-tax/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Huang, R.; Deng, H.; Chan, A. The legal nature of cryptocurrency as property: Accounting and taxation implications. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2023, 51, 105860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTS Global Financial Services Newsletter #2/2025 Is Now Available. Available online: https://wts.com/global/publishing-article/20240117-financial-services-newsletter-2-2024~publishing-article (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Nigeria Crypto Tax Advice. Available online: https://taxnatives.com/jurisdiction/nigeria/crypto-tax-advice/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Taxation on Cryptocurrency: Guide to Crypto Taxes in India 2025. Available online: https://cleartax.in/s/cryptocurrency-taxation-guide (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Cryptocurrency Tax Guides. Available online: https://koinly.io/blog/tags/guides/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Crypto Tax Guides. Available online: https://coinledger.io/guides (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Tax Guides. Available online: https://kryptos.io/guides (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Nikkel, B. Fintech forensics: Criminal investigation and digital evidence in financial technologies. Forensic Sci. Int. Digit. Investig. 2020, 33, 200908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiklejohn, S.; Pomarole, M.; Jordan, G.; Levchenko, K.; McCoy, D.; Voelker, G.M.; Savage, S. A fistful of bitcoins: Characterizing payments among men with no names. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Internet Measurement Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 23–25 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnuolo, M.; Maggi, F.; Zanero, S. Bitiodine: Extracting intelligence from the bitcoin network. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Christ Church, Barbados, 3–7 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Balaskas, A.; Franqueira, V. Analytical tools for blockchain: Review, taxonomy and open challenges. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cyber Security and Protection of Digital Services (Cyber Security), Scotland, UK, 11–12 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arner, D.; Barberis, J.; Buckley, R. FinTech and RegTech in a Nutshell, and the Future in a Sandbox; CFA Institute Research Foundation: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Demirhan, H. Effective taxation system by blockchain technology. In Blockchain Economics and Financial Market Innovation: Financial Innovations in the Digital Age; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Massad, T. It’s time to strengthen the regulation of crypto-assets. In Economic Studies at Brookings; The John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bornman, M.; Soobramoney, J. Encouraging a Culture of Tax Compliance for South Africans Owning and Using Crypto Assets; College of Business & Economics, University of Johannesburg: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- The Top 10 Places to Spend Your Crypto in SA. Available online: https://www.moneyweb.co.za/in-depth/fivewest/the-top-10-places-to-spend-your-crypto-in-sa/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Javarone, M.; Wright, C. From bitcoin to bitcoin cash: A network analysis. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Cryptocurrencies and Blockchains for Distributed Systems, Munich, Germany, 15 June 2018; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, M.; Kumar, E.; Lal, C.; Ruj, S. A survey on security and privacy issues of bitcoin. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 20, 3416–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, M. Is non-fungible token pricing driven by cryptocurrencies? Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 44, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, l.; He, Z.; Li, J. Decentralized mining in centralized pools. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2021, 34, 1191–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.; Rishiwal, V.; Tanwar, S.; Yadav, M. Blockchain and crypto forensics: Investigating crypto frauds. Int. J. Netw. Manag. 2024, 34, e2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.