Abstract

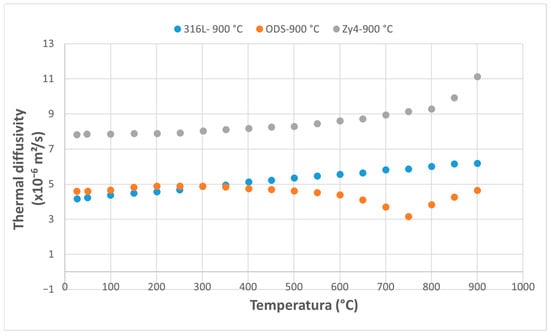

The paper presents a comparative experimental study of heat-transfer behavior in three alloys considered candidate materials for nuclear reactors: the austenitic stainless steel 316L, Zircaloy-4 (currently used in CANDU reactors), and an ODS alloy with a ferritic matrix. The investigation was conducted across five temperature intervals, each sample being subjected to a thermal shock through short-term overheating to the upper limit of its respective interval. The variation of thermal diffusivity in the three alloys was determined as a function of both measurement temperature and applied thermal shock, and trends in heat-transfer behavior were compared across the five temperature ranges. The experimental results show that up to 400 °C, Zircaloy-4 exhibits the highest thermal diffusivity, followed by the ODS alloy, with the lowest values measured for 316L steel. At approximately 450 °C, the ratio between 316L and the ODS alloy reverses. Beyond this point, increasing the temperature up to 900 °C is accompanied by a continuous rise in thermal diffusivity for both 316L stainless steel and Zircaloy-4. In contrast, for the ODS steel, increasing temperature leads to a continuous decrease in thermal diffusivity, reaching a minimum near the Curie point. The novelty of the study lies in the comparative assessment of the influence of temperature on the heat-transfer process in three alloys relevant to nuclear energy, covering the operating temperature ranges of CANDU and ALFRED reactors, as well as potential accidental overheating up to 900 °C. A particular feature of the work is the prior application of a short-duration overheating step produced using solar energy. The results are relevant not only for nuclear reactors but also for other high-temperature applications in corrosive environments.

1. Introduction

The fuel cladding plays a critical role in ensuring the tightness and structural integrity of the fuel assembly. It surrounds the UO2 pellets, forming the fuel element and providing a barrier that isolates fissile material and fission products from the coolant.

In the CANDU (Canada Deuterium Uranium) reactor, which employs natural uranium (UO2) fuel and is cooled with heavy water at a pressure of approximately 10 MPa, the operating temperature of the cladding under normal conditions is in the range of 300–350 °C. These values can be significantly exceeded during a Loss of Coolant Accident (LOCA) [1,2,3].

In the ALFRED (Advanced Lead Fast Reactor European Demonstrator) reactor, cooled with liquid lead, the fuel consists of enriched uranium oxide (MOX or UO2). Here, the operating temperature of the cladding is between 450–550 °C, and may locally reach even higher values depending on the specific core position. The use of liquid lead as coolant allows operation at higher temperatures without requiring elevated system pressure [4,5,6].

The heat flux through the cladding, for a given thickness and temperature, is governed by the thermal diffusivity of the cladding material. Candidate alloys for next-generation fuel cladding are expected to operate at higher temperatures than those of Generation III reactors, and must therefore exhibit not only good mechanical performance and thermal stability, but also high resistance to corrosion under elevated temperatures together with enhanced heat transfer properties.

Austenitic stainless steel 316L has a fully austenitic structure, stable across the entire operating temperature range of both CANDU and ALFRED reactors. Owing to its low carbon content, it exhibits excellent corrosion resistance, including resistance to intergranular corrosion [7,8,9,10,11]. It is also characterized by good weldability, absence of magnetic transition (no Curie point), and non-magnetic behavior at normal temperatures. Like all austenitic steels, however, it has relatively low thermal diffusivity compared to ferritic steels and Zircaloy-4; its thermal diffusivity at ambient temperature is approximately 3–4 × 10−6 m2/s. In nuclear applications, this drawback is compensated by its good irradiation resistance, which ensures integrity under high neutron fluence, as well as its stable mechanical strength up to 600–650 °C, superior creep resistance, corrosion resistance in light-water environments (PWR—Pressurized Water Reactor, BWR—Boiling Water Reactor) and liquid sodium, and chemical compatibility with both nuclear fuel and coolant. These properties allow for the use of thin cladding walls while maintaining thermal efficiency [10,11].

The use of Zircaloy-4 as fuel cladding material in Pressurized Water Reactors is motivated by a well-defined set of properties that make it highly suitable for nuclear applications: good compatibility with nuclear fuel (UO2), favorable mechanical performance within the operating temperature range, excellent corrosion resistance in light water and steam, very low thermal neutron absorption cross-section, dimensional and structural stability at elevated temperatures (350–400 °C), and advantageous processing characteristics, as it can be readily rolled, welded, and extruded into tubes and rods. Zircaloy-4 also exhibits good behavior under Loss of Coolant Accident (LOCA) conditions [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Over the years, extensive research has been conducted on this alloy, resulting in a comprehensive database. Studies indicate that its thermal diffusivity is relatively high, reaching values of α ≈ 10–12 × 10−6 m2/s. However, its use is constrained by the fact that, at very high temperatures (such as those occurring during severe accidents), Zircaloy-4 reacts with water, generating hydrogen. This process leads to hydriding-induced embrittlement of the cladding, degrading its mechanical properties and representing a major safety concern [16]. Furthermore, its heat transfer performance is significantly influenced by corrosion processes [18].

Oxide-Dispersion-Strengthened (ODS) steels have been regarded as a promising option for nuclear fuel cladding owing to their high resistance to creep and irradiation—both essential features for operation in the extreme environments of nuclear reactors. The presence of finely dispersed oxide nanoparticles, particularly Y2O3, provides structural stability and ensures adequate mechanical performance at elevated temperatures [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. The advantages of employing ODS steels as cladding materials in advanced nuclear reactors must, however, be weighed against the technological challenges associated with their processing, which necessitates advanced manufacturing techniques such as hot extrusion and Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS). The implementation of ODS steels for nuclear fuel cladding is expected to contribute significantly to enhancing both safety and long-term efficiency in advanced reactor operation. Numerous studies have investigated fabrication technologies [19,20,21,22,23], as well as the effects of chemical composition and irradiation on the microstructure and properties of these steels [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

The present study provides a comparative analysis of heat transfer in three candidate cladding materials: an austenitic stainless steel, an oxide-dispersion-strengthened (ODS) alloy, and the Zircaloy-4 alloy.

2. Materials and Experimental Techniques

The comparative study was carried out on three materials considered as candidates for the cladding matrix of nuclear fuel elements: austenitic stainless steel 316L (Gnee, Tianjin, China), Zircaloy-4 (EDZ Eldorado Nuclear Ltd./Cameco, Cobourg, ON, Canada, currently employed in CANDU reactors), and an ODS-type alloy with a ferritic matrix, produced by mechanical alloying and SPS.

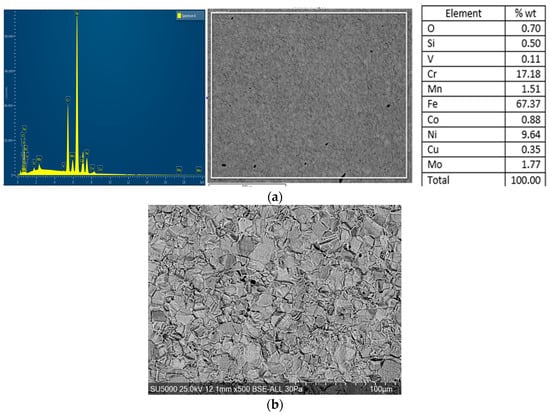

The austenitic stainless steel 316L investigated in this study is molybdenum-alloyed (EURONORM: 1.4404, ASTM/ASME: UNS S31603). Its standard chemical composition is given in Table 1, while the elemental composition obtained by SEM-EDS analysis is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of 316L stainless steel according to EURONORM: 1.4404.

Figure 1.

316L alloy in delivery condition: (a)—Chemical composition of 316L stainless steel determined by SEM-EDS; (b)—SEM microstructure of the 316L alloy (500×, PV-BSE, 25 kV, 30 s; file: 30 si.bmp), etched by immersion in nitric acid (HNO3) with a 65% volume concentration. The samples were then rinsed with distilled water and dried.

316L steel is hot-worked, annealed for homogenization and carbide solution treatment at temperatures above 1000 °C, and rapidly quenched to restore corrosion resistance.

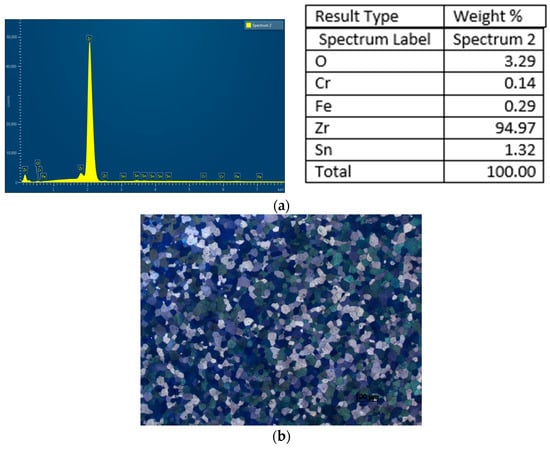

Zircaloy-4 is a zirconium-based alloy containing small additions of tin, iron, and chromium. Its standard chemical composition is as follows: Sn: 1.2–1.7%; Fe: 0.18–0.24%; Cr: 0.07–0.13%; N: <0.03%. The elemental composition determined experimentally is shown in Figure 2. The Zy-4 alloy, in the form of a plate resulting from the flattening of the tube, is in a cold-worked and recrystallized state, resulting in a fine structure with equiaxed grains, suitable for fuel cladding—providing excellent corrosion resistance and the necessary mechanical properties.

Figure 2.

Zircaloy-4 alloy: (a)—Chemical composition determined by SEM-EDS; (b)—Microstructure in a transverse section of the rod after etching with 45% nitric acid, 45% water, and 10% hydrofluoric acid.

The ODS alloy with a ferritic steel matrix investigated in the present study was produced by mechanical alloying followed by SPS. High-purity powders were employed, with the following particle sizes: Fe < 74 μm, Cr < 10 μm, Ti < 45 μm, W ≈ 80 nm, and nanometric Y2O3 (50–70 nm). Mechanical alloying was performed in a PM400 Retsch planetary ball mill for a total effective time of 40 h, in 480 cycles (5 min milling + 15 min pause), at a rotational speed of 350 rpm and with a ball-to-powder weight ratio of 10:1. As a process control agent, 2% n-heptane was used.

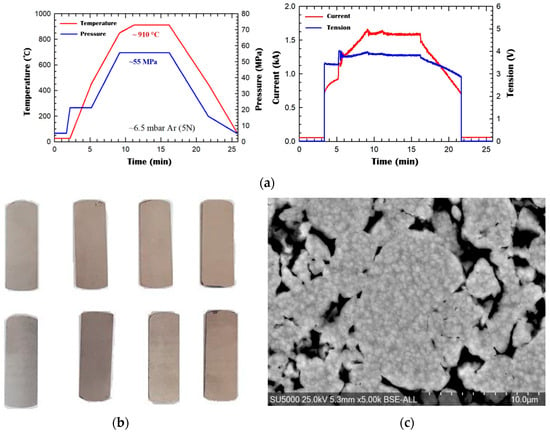

Sintering was conducted using SPS with an HPD50 system. The sintering parameters (Figure 3a) were: maximum temperature 910 °C with a 5 min dwell at peak temperature; Emax = 4.33 V; Imax = 1.81 kA; maximum pressure 45 MPa; argon atmosphere under continuous flow.

Figure 3.

ODS 14YWTi alloy obtained by mechanical alloying and SPS sintering: (a) sintering conditions; (b) samples used for thermal shock testing in the solar furnace; (c) SEM microstructure.

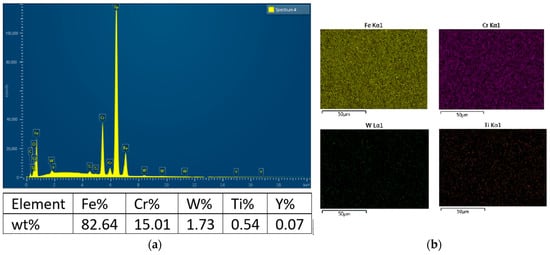

The elemental chemical analysis by EDX (Figure 4a) highlighted concentrations of Fe, Cr, W, and Ti close to the initial proportions in the powder mixture. The Y content was difficult to determine due to the very low addition of Y2O3 (0.3%). The elemental composition (Figure 4b) indicates good dissolution of tungsten within the ferritic matrix.

Figure 4.

SEM-EDX spectral analysis in (a) and elemental chemical composition map in (b) of the ODS 14YWTi alloy obtained by mechanical alloying and SPS sintering.

The ODS steel, produced by mechanical alloying, falls into the category of ferritic ODS steels according to international standards for advanced nuclear materials, even though there is as yet no dedicated ISO/EN standard for 14Cr ODS Ferritic Steels. It is recognized under the designation “14Cr ODS Ferritic Steel” within ASME Sec. III Div. 5/IAEA/EUROfusion programs. The composition Fe–14Cr–2W–0.35Y2O3 (wt.%) has been used in several experimental studies (manufacturing via MA + HIP/PM).

The nominal compositions for this group of alloys are as follows: Fe: balance, Cr: 14.0 ± 1.0, W: 2.0 ± 1.0, Ti: 0.3–0.5, Y2O3: 0.25–0.35, Zr: optional 0.0–0.3, Al: optional 0–5.0 (if oxidative protection is required), C, N: ≤0.02 wt.% (or according to embrittlement requirements), Mo, Nb, Ni, Cu: restricted/avoided for reduced-activation purposes.

The samples used for thermal shock and diffusivity measurements are flat specimens with dimensions of 10 × 10 × 1.5 [mm].

Investigations on the evolution of thermal diffusivity of the three alloys as a function of measurement temperature were conducted over five temperature ranges, with the maximum temperature spanning 500–900 °C. It was assumed that, under operational conditions, the alloy experienced a brief overheating at the upper limit of each range.

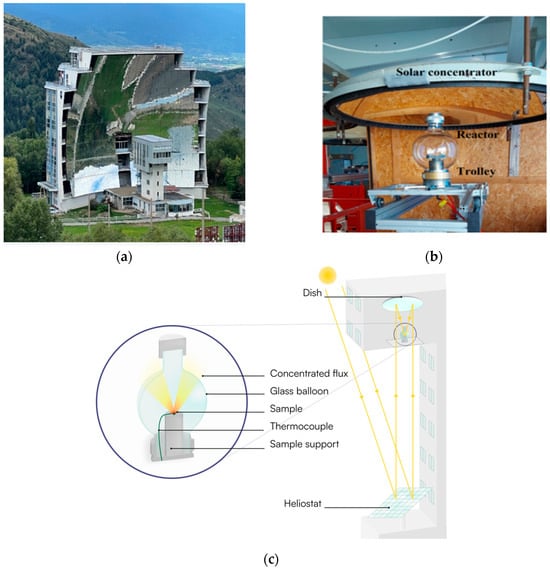

Thermal shock testing was performed in a 1.5 kW Solar Furnace at the PROMES laboratory, Font Romeu-Odeillo, France (Figure 5). The solar facility consists of a 2-axis heliostat that tracks the sun and a 2 m parabolic dish, along with shutters allowing regulation of the incident power. The samples were placed on a water-cooled support in a reactor under air (Figure 5b,c). The temperature was monitored using a K-type thermocouple inserted into the sample, together with a data acquisition system operating at a recording frequency of 1 Hz. The typical heating ramp ranged between 16 °C/s and 30 °C/s. Cooling was performed in air. Thermal shocks were applied with an overheating duration of 30 s at maximum overheating temperatures between 500 °C and 900 °C in 100 °C steps

Figure 5.

CNRS PROMES laboratory at Odeillo Font Romeu: (a) solar furnace; (b) testing setup and schematic in (c).

Microstructural characterization was performed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) coupled with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) on a Hitachi SU5000 microscope equipped with an EDX system for elemental chemical analysis.

The thermal transport properties (thermal diffusivity, α) were investigated using a Laser Flash Analyzer (Netzsch LFA 457 Microflash, Selb, Germania) from room temperature up to 900 °C [32,33,34,35]. The measurements were performed in Ar flow (30 mL/min) after 3 purging cycles (vacuum + Ar gas filling). The samples were cleaned with ethanol to remove any detaching particles resulting from heat exposure, but the exposed surface was not ground and/or polished in order to preserve the heat exposure induced surface modification. The measured surfaces (bottom unexposed and top exposed) were covered with a graphite (aerosol) coating. Typical thickness of the graphite layer is 30–50 nm. However, the surface roughness can lead to local covering of a few microns. State the number of repeated flashes/measurements per data point and give an estimate of measurement scatter or uncertainty.

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

For each material, the effect of overheating temperature on thermal diffusivity was investigated, and the corresponding thermal diffusivity–measurement temperature curves were plotted.

Thermal diffusivity measurements were carried out from ambient temperature up to the maximum thermal shock temperature specific to each domain.

3.1. Influence of Thermal Shock Overheating on Heat Transfer in the Three Alloys

With the exception of the investigations conducted by Pichler on the determination of thermal diffusivity of alloy 316L at high temperatures in the liquid state [36], most studies on this alloy have focused on the influence of processing technologies on its thermal diffusivity [35,37,38,39,40]. Kim examined the evolution of thermal diffusivity in steels as a function of measurement temperature [37].

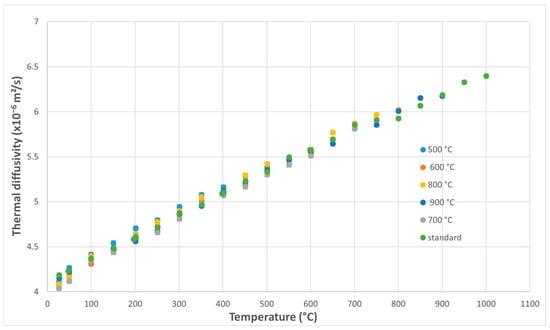

For austenitic stainless steel 316L, the thermal diffusivity values exhibit a consistent increase with measurement temperature, while remaining relatively similar across the five overheating conditions investigated (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Variation of thermal diffusivity of 316L steel samples with measurement temperature as a function of applied thermal shock temperature.

The measured thermal diffusivity values for 316L steel, determined after short-term overheating at elevated temperatures, are 12–30% higher than those reported by Kim [37], with the largest differences observed at measurement temperatures below 600 °C. The difference is explained by the improvements made to 316L steel through composition and heat treatment, which significantly influence the values of its thermophysical properties.

The influence of thermal shock temperature on the diffusivity of 316L steel is small. In practice, the variation curves for the five overheating temperatures produced by thermal shock are very close to that of the reference sample, the untreated specimen.

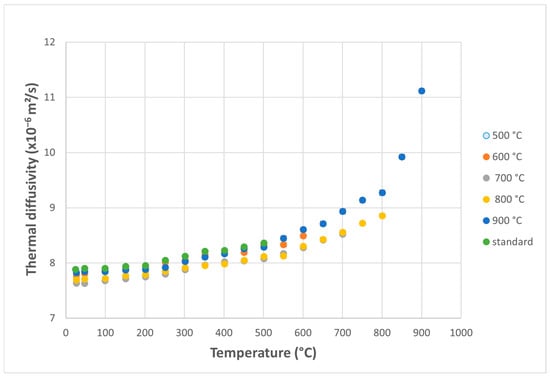

For the Zircaloy-4 alloy, thermal diffusivity values continuously increase with measurement temperature, with a pronounced rise in the curve above 600 °C (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Variation of thermal diffusivity with measurement temperature for Zircaloy-4 samples subjected to thermal shocks, as a function of applied shock temperature.

The thermal diffusivity values obtained for the Zy-4 alloy samples subjected to overheating are in good agreement with previously reported data in the literature [38,39].

The thermal diffusivity curves for the five overheating temperatures are closely spaced, maintaining a strongly increasing trend at high temperatures.

The evolution of diffusivity with the measurement temperature and with increasing thermal shock temperature is always upward, so these do not negatively affect the heat transfer properties.

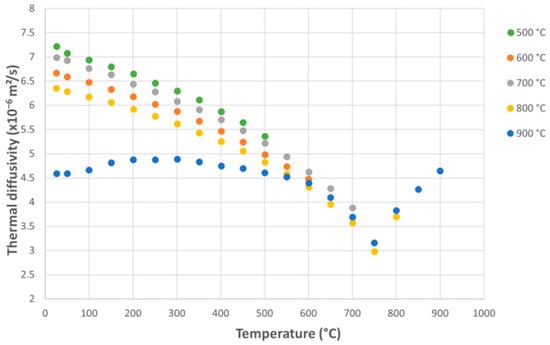

Measurements of thermal diffusivity as a function of measurement temperature for the ODS alloy with a ferritic matrix showed a decrease in diffusivity with increasing thermal shock temperature. Increasing the measurement temperature for the same overheating level leads to a continuous decrease in diffusivity, reaching a minimum around 750 °C (Figure 8), after which the trend reverses, showing a gradual increase.

Figure 8.

Variation of thermal diffusivity with measurement temperature for ODS alloy samples subjected to thermal shocks, as a function of applied shock temperature.

The variation of thermal diffusivity in ferritic steel around the Curie point can be explained by the ferromagnetic–paramagnetic transition, which directly affects the mechanisms of heat transport. As the temperature approaches the Curie point, the material gradually loses its magnetic order, and magnetic excitations (magnons) absorb a significant part of the thermal energy. At the same time, the concentration of crystalline defects increases, and the electronic contribution to thermal conductivity decreases. These mechanisms lead to a pronounced drop in thermal diffusivity. Near the Curie point, the specific heat exhibits a peak due to the latent magnetic heat associated with the phase transition, which contributes to the formation of a local minimum in thermal diffusivity-resulting in an inverted V-shaped trend. Above the Curie point, once ferromagnetism and magnetic excitations have vanished, the heat transport mechanisms normalize, and the diffusivity gradually increases again with temperature, mainly influenced by phonon conduction and microstructural stabilization. This characteristic evolution-a sharp decrease in diffusivity down to a minimum near the Curie temperature, followed by a gradual increase-is consistent with observations reported in previous studies [40,41,42].

3.2. Comparative Study of Thermal Diffusivity Variation Across Five Temperature Ranges

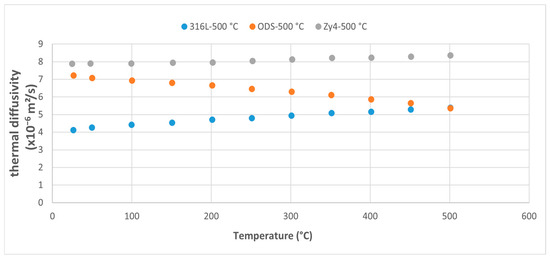

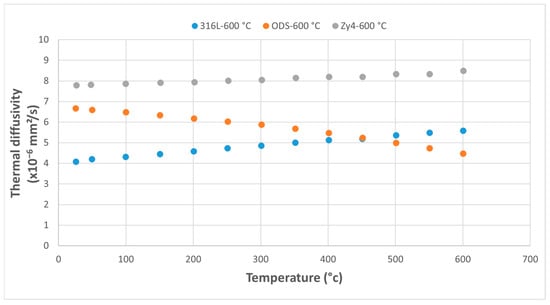

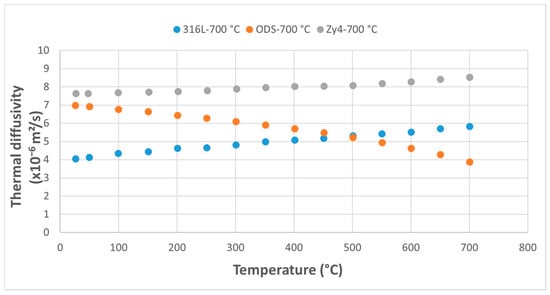

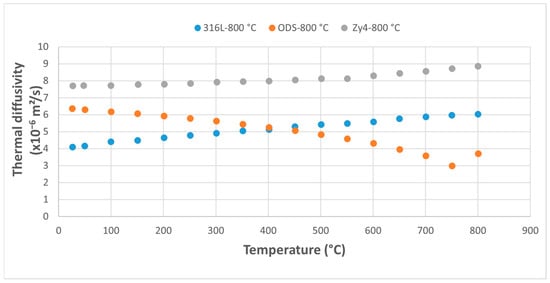

The variation of thermal diffusivity with measurement temperature for the three materials across five temperature ranges, following the application of thermal shock overheating at the maximum temperature of each range, is presented in Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 9.

Comparative study of thermal diffusivity evolution for the three alloys in the 0–500 °C range.

Figure 10.

Comparative study of thermal diffusivity of the three alloys following thermal shock application at 600 °C.

Figure 11.

Comparative study of thermal diffusivity of the three alloys following thermal shock application at 700 °C.

Figure 12.

Comparative study of thermal diffusivity of the three alloys following thermal shock application at 800 °C.

Figure 13.

Variation of thermal diffusivity of the three alloys following thermal shock application at 900 °C.

In all temperature ranges, the thermal diffusivity curves for Zircaloy-4 and 316L steel are nearly parallel, with Zircaloy-4 exhibiting significantly higher values and a faster increase at elevated temperatures. The thermal diffusivity curve of the ODS alloy, however, shows a different trend compared to the other two alloys across all five temperature ranges.

At room temperature, the ODS alloy shows values close to those of Zircaloy-4, and higher than those of 316L steel. In the temperature range up to 500 °C, increasing the temperature leads to a decrease in the diffusivity of the ODS alloy, approaching the values of 316L steel. At the upper end of the temperature range, it intersects the curve of the austenitic 316L steel (Figure 9).

At overheating temperatures of 600 °C and 700 °C, the thermal diffusivity of the ODS alloy decreases below that of the austenitic stainless steel, while the diffusivity of the Zy-4 and 316L alloys shows a continuously increasing trend (Figure 10 and Figure 11).

Increasing the overheating temperature results in a more rapid decrease in the thermal diffusivity in the ODS alloy. Its diffusivity drops below that of 316L steel at 400 °C for overheating at 800 °C (Figure 12) and at 350 °C for the previous overheating at 900 °C (Figure 13). The results highlight the rapid decrease in the ODS alloy’s diffusivity with increasing temperature, while the diffusivity of the 316L and Zy-4 alloys continues to increase. A reduction in the difference between the values for 316L and Zy-4 is also observed as the thermal shock temperature increases (Figure 12 and Figure 13).

4. Conclusions

The influence of overheating and measurement temperature on the thermal diffusivity of three candidate materials for nuclear fuel cladding was investigated: austenitic stainless steel 316L, Zircaloy-4 (currently used for CANDU reactor fuel cladding), and an ODS-type alloy produced by mechanical alloying and sintering.

The temperature ranges for thermal diffusivity measurements cover the operational domains of fuel cladding, as well as other high-temperature applications in corrosive environments.

For Zircaloy-4 and austenitic 316L steel, thermal diffusivity values increase continuously with measurement temperature, with Zircaloy-4 exhibiting higher values. Increasing the pre-measurement overheating temperature results in thermal diffusivity curves that remain closely spaced for both Zircaloy-4 and 316L steel.

The ferritic ODS alloy shows thermal diffusivity curves that decrease continuously with measurement temperature up to near the Curie point. Around the Curie temperature, thermal diffusivity exhibits a minimum associated with the magnetic transition, reduction in thermal conductivity, and an increase in heat capacity. Above the Curie point, diffusivity stabilizes and increases gradually with temperature

The experimental results obtained provide a comparative analysis of the heat transfer properties of the three investigated alloys, as a function of both the degree of superheating and the measurement temperature.

In the thermal range of 400–800 °C corresponding to normal operating conditions, the diffusivity of the ODS alloy with a ferritic matrix lies below that of the austenitic steel 316L and far below that of the Zy-4 alloy, with a minimum at approximately 750 °C. In this range, heat transfer through the ODS alloy is poor.

In the case of steels, the data highlight the influence of the matrix on the variation of thermal diffusivity with temperature.

The study highlights the influence of the ferritic matrix structure on the variation of the thermal diffusivity of the ODS alloy. In the thermal range of 400–800 °C corresponding to normal operating conditions, the diffusivity of the ODS alloy with a ferritic matrix lies below that of the austenitic steel 316L and far below that of the Zy-4 alloy, with a minimum at approximately 750 °C. In this range, heat transfer through the ODS alloy is poor.

The results contribute to enriching existing databases and are important for selecting suitable materials that operate in corrosive environments and specific temperature ranges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and M.G.S.P.; methodology, M.A., N.C., A.G., M.G. and A.D.N.; software, F.P. and A.G.J.; validation, I.C.P., A.H. and R.S.; formal analysis, M.I.P. and A.H.; investigation, M.A., N.C., A.D.N. and R.S.; resources, M.I.P.; data curation, A.G. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A. and F.P.; writing—review and editing, M.I.P.; visualization, M.G.S.P. and A.H.; supervision, M.A. and R.S.; project administration, N.C. and A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 823802. We thank the CNRS-PROMES laboratory, UPR 8521, belonging to the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) for providing access to its installations, the support of its scientific and technical staff, within this grant agreement No. 823802 (SFERA-III).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Goldberg, M.; Rosner, R. Nuclear Reactors: Generation to Generation; American Academy of Arts and Sciences: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 0-87724-090-6. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA). Nuclear Fuel Behaviour in Loss-of-Coolant Accident (LOCA) Conditions; State-of-the-Art Report No. 6846; NEA-CSNI-R-2009-15; OECD Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA): Paris, France, 2009; Volume 48, p. 369. ISBN 978-92-64-99091-3. [Google Scholar]

- Health and Safety Executive. Report of the System Design and Security Review of the AP1000 Nuclear Reactor (Step 3 of the Generic Design Assessment Process). November 2009. Available online: http://www.hse.gov.uk (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Dumitrescu, A.-V.; Nistor-Vlad, R.M.; Dupleac, D.; Allison, C. ALFRED fuel assembly model development and validation with RELAP/SCDAPSIM/MOD4. 1. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. C 2023, 85, 319–330. [Google Scholar]

- GEN IV International Forum. Lead-Cooled Fast Reactor (LFR). Available online: https://www.gen-4.org/generation-iv-criteria-and-technologies/lead-fast-reactors-lfr (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Robinson, A.L.; Was, G.S. Materials hurdles for advanced nuclear reactors. MRS Bull. 2015, 40, 554–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroušek, P.; Kvačkaj, T.; Bidulská, J.; Bidulský, R.; Actis Grande, M.; Manfredi, D.; Weiss, K.-P.; Kočiško, R.; Lupt, M.; Pokorn, I. Investigation of the properties of 316L stainless steel after AM and heat treatment. Materials 2023, 16, 3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, C.; Qin, F.; Chen, H.; Zhao, X.; Liu, R.; Gao, S. The microstructure and mechanical properties of 316L austenitic stainless steel prepared by forging and laser melting deposition. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 870, 144820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, Y.; Gao, B.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y. Superior strength and ductility of 316L stainless steel with heterogeneous lamella structure. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 10442–10456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Nam, K.-E.; Eoh, J. High-temperature material properties of type 316L stainless steel for pressure boundary components at 700 °C coolant. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024, 56, 4698–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Liu, F.; Wang, Q.; Nai, S.M.L.; Zhou, W. Cryogenic and high temperature tensile properties of 316L steel additively manufactured by laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 900, 146461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pshenichnikov, A.; Stuckert, J.; Walter, M. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Zircaloy-4 cladding hydrogenated at temperatures typical for loss-of-coolant accident (LOCA) conditions. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2015, 283, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieurmel, R.; Besson, J.; Pouillier, E.; Parrot, A.; Ambar, A.; Gourgues-Lorenzon, A.-F. Contribution to the understanding of brittle fracture conditions of zirconium alloy fuel cladding tubes during LOCA transient. J. Nucl. Mater. 2019, 527, 151815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.; Khan, M.K.; Pathak, M.; Singh, R.N. Effects of hydrogen on thermal creep behaviour of Zircaloy fuel cladding. J. Nucl. Mater. 2018, 498, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanellato, O.; Preuss, M.; Buffiere, J.Y.; Ribeiro, F.; Steuwer, A.; Desquines, J.; Andrieux, J.; Krebs, B. Synchrotron diffraction study of dissolution and precipitation kinetics of hydrides in Zircaloy-4. J. Nucl. Mater. 2012, 420, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinga, A.I.; Abrudeanu, M.; Radu, V.; Nițu, A.; Stoica, L.; Toma, D.; Petrescu, M.I. Evaluation of the Zirconium Hydride Morphology at the Flaws in the CANDU Pressure Tube Using a Novel Metric. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Jabbar, N.M.; Mann, S.C.; White, J.T.; Kardoulaki, E. Measuring thermal diffusivity and gap conductance in uranium nitride and Zircaloy relevant for microreactor applications. J. Nucl. Mater. 2025, 603, 155399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrudeanu, M.; Archambault, P. L’influence de l’oxydation à haute température sur la diffusivité thermique de l’alliage Zy-4. In Proceedings of the 9e Congrés International du Traitement Thermique et de l’Ingénierie des Surfaces, Nice, France, 26–28 September 1994; pp. 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bergner, F.; Hilger, I.; Virta, J.; Lagerbom, J.; Gerbeth, G.; Connolly, S.; Hong, Z.; Grant, P.S.; Weissgärber, T. Alternative fabrication routes towards oxide dispersion strengthened steels and model alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2016, 47, 5313–5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogachev, I.G. Fabrication of 13Cr-2Mo ferritic/martensitic oxide-dispersion-strengthened steel components by mechanical alloying and spark-plasma sintering. JOM 2014, 66, 1020–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imagawa, Y.; Hashidate, R.; Miyazawa, T.; Onizawa, T.; Ohtsuka, S.; Yano, Y.; Tanno, T.; Kaito, T.; Ohnuma, M.; Mitsuhara, M.; et al. Creep deformation and rupture behavior of 9Cr-ODS steel cladding tube at high temperatures from 700 °C to 1000 °C. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2024, 61, 762–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, M.A.; De Castro, V.; Leguey, T.; Monge, M.A.; Muñoz, A.; Pareja, R. Microstructure and tensile properties of oxide dispersion strengthened Fe–14Cr–0.3Y2O3 and Fe–14Cr–2W–0.3 Ti–0.3Y2O3. J. Nucl. Mater. 2013, 442, S142–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzaza, S.; Al-Jabri, S. Microstructure characterization and thermal stability of the ball milled iron powders. J. Thermal. Anal. Calorim. 2015, 119, 1037–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Morphology and structure evolution of Y2O3 nanoparticles in ODS steel powders during mechanical alloying and annealing. Adv. Powder Technol. 2015, 26, 1578–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinkle, S.J.; Ice, G.E.; Miller, M.K.; Pennycook, S.J.; Wang, X.L. Advances in microstructural characterization. J. Nucl. Mater. 2009, 386, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shen, X. Research Progress of ODS FeCrAl Alloys–A Review of Composition Design. Materials 2023, 16, 6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luptáková, N.; Svoboda, J.; Bártková, D.; Weiser, A.; Dlouhý, A. The Irradiation Effects in Ferritic, Ferritic–Martensitic and Austenitic Oxide Dispersion Strengthened Alloys: A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozar, L.; Hohenauer, W. Flash method of measuring the thermal diffusivity. A review. High Temp.—High Press. 2004, 36, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnoli, E.; Matteis, P.; Mortarino, G.M.; Scavino, G. Thermal diffusivity of traditional and innovative sheet steels. In Defect and Diffusion Forum; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Wollerau, Switzerland, 2010; Volume 297, pp. 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miculescu, M.; Cosmeleata, G.; Branzei, M.; Miculescu, F. Thermal diffusivity of materials using flash method applied on CoCr alloys. UPB. Sci. Bull. Ser. B 2008, 70, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Arva, E.R.; Abrudeanu, M.; Negrea, D.A.; Galatanu, A.; Galatanu, M.; Rizea, A.D.; Anghel, D.C.; Branzei, M.; Jinga, A.I.; Petrescu, M.I. Experimental Research on the Influence of Repeated Overheating on the Thermal Diffusivity of the Inconel 718 Alloy. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, P.; Simonds, B.J.; Sowards, J.W.; Pottlacher, G. Measurements of thermophysical properties of solid and liquid NIST SRM 316L stainless steel. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 4081–4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissonnet, G.; Bonnet, G.; Pedraza, F. Thermo-physical properties of HR3C and P92 steels at high-temperature. J. Mater. Appl. 2019, 8, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, I.; Sevostianov, I.; Azarmi, F.; Tangpong, X. Mechanical and thermal properties of stainless steel parts, manufactured by various technologies, in relation to their microstructure. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2021, 159, 103398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.C.; Chen, X.; Azizi, A.; Daeumer, M.A.; Zavalij, P.Y.; Zhou, G.; Schiffres, S.N. Influence of processing and microstructure on the local and bulk thermal conductivity of selective laser melted 316L stainless steel. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 32, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koniorczyk, P.; Zmywaczyk, J.; Dębski, A.; Zieliński, M.; Preiskorn, M.; Sienkiewicz, J. Investigation of thermophysical properties of three barrel steels. Metals 2020, 10, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.S. Thermophysical Properties of Stainless Steels; ANH 75-55; Argonne National Laboratory: Lemont, IL, USA, 1975; p. 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Wang, H.; McAuliffe, R.; Yan, Y.; Curlin, S.; Graening, T.; Linton, K.; Nelson, A. Report Summarizing Demonstration of Thermal Conductivity Measurement Methods for Coated Zirconium Cladding; Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrudeanu, M.; Dicu, M.M.; Pasare, M.M. Structure and Heat Transfer in Zircaloy-4 Treated at High Temperatures. Materials 2021, 14, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, L.; Dabhade, V.V. Synthesis of Fe-15Cr-2W oxide dispersion strengthened (ODS) steel powders by mechanical alloying. Powder Technol. 2023, 425, 118554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agazhanov, A.S.; Samoshkin, D.A.; Stankus, S.V. Thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity of iron in the temperature range of 300–1700 K. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2023, 124, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ResearchGate. Measured Transport Properties of Steel Along the Ferromagnetic to Paramagnetic Transition (Curie Point). Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Thermal-diffusivity-of-various-steel-alloys-close-to-the-Curie-point_fig1_237609982 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.