Abstract

Wellbore integrity maintenance constitutes a fundamental safety and technological challenge throughout the entire lifecycle of oil and gas wells (including production, injection, and CO2 sequestration operations). As a critical completion phase, perforation generates a high-temperature, high-pressure shaped charge jet that impacts and compromises wellbore structural integrity. This process may induce failure in both the cement sheath body and its interfacial zones, potentially creating fluid migration pathways along the cement-casing interface through perforation tunnels. Current research remains insufficient in quantitatively evaluating cement sheath damage resulting from perforation operations. Addressing this gap, this study incorporates dynamic jet effects during perforation and establishes a numerical model simulating high-velocity jet penetration through casing–cement target–formation composites using a rock dynamics-based constitutive model. The investigation analyzes failure mechanisms within the cement sheath matrix and its boundaries during perforation penetration, while examining the influence of mechanical parameters (compressive strength and shear modulus) of both cement sheath and formation on damage characteristics. Results demonstrate that post-perforation cement sheath aperture exhibits convergent–divergent profiles along the tunnel axis, containing exclusively radial fractures. Primary fractures predominantly initiate at the inner cement wall, whereas microcracks mainly develop at the outer boundary. Enhanced cement compressive strength significantly suppresses fracture initiation at both boundaries: when increasing from 55 MPa to 75 MPa, the undamaged area ratio rises by 16.6% at the inner wall versus 11.2% at the outer interface. Meanwhile, increasing the formation shear modulus from 10 GPa to 15 GPa reduces cement target failure radius by 0.4 cm. Cement systems featuring high compressive strength and low shear modulus demonstrate superior performance in mitigating perforation-induced debonding.

1. Introduction

With growing momentum behind the comprehensive green transition, high-emission conventional fuels are increasingly facing substitution by green energy sources [1,2,3]. Shale oil and gas represent a class of unconventional hydrocarbons hosted in organic shale formations and their interlayers, distinguished by their significant resource volume and advancements in clean, efficient extraction. They are expected to become a significant resource for future energy supply [4,5,6]. Since shale reservoir matrix typically has very low porosity and permeability, making adequate hydrocarbon flow difficult, technologies such as multi-stage fracturing are often employed during development to create a complex fracture network in the reservoir, significantly increasing the drainage area and providing high-productivity pathways for oil and gas [7,8]. Perforation technology is a key process for establishing flow channels between the wellbore and the reservoir, providing the conditions for implementing stimulation measures such as multi-stage fracturing and acidizing. This technology selectively penetrates the target production zone, perforating the casing, cement sheath, and near-wellbore region to establish a fluid communication path capable of withstanding high-pressure operations, thereby enabling precise stimulation and effective production of specific reservoir sections [9,10,11]. During this process, the high-velocity jet generated by perforation penetrates the cement sheath, causing inevitable damage and leading to a loss of its sealing integrity. In severe cases, this can lead to fluid channeling or sustained casing pressure, resulting in further deformation and damage to the wellbore and affecting well productivity, thereby shortening the well’s life cycle [12,13]. Given these concerns, a detailed assessment of the damage mechanisms inflicted upon cement sheath seals during perforation is required. Such understanding is vital to inform and enhance both future operational practices and the design of advanced cement slurries.

Perforation operations that penetrate the cement sheath can damage its structure, leading to loss of integrity. During perforation, the explosive in the perforating charge detonates, generating high temperature and pressure that compress the liner and form a metal jet. The jet’s penetrating effect perforates the casing-cement sheath assembly and forms hydrocarbon migration channels in the formation. During this penetration process, the cement sheath itself is damaged. Liu et al. [14] reported that increasing casing pressure aggravates tensile failure in cement sheaths under horizontal well perforation. Bu et al. [15] linked this to stress concentration, finding that lower elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio reduce the tensile stress. Meanwhile, Wei et al. [16] identified radial debonding at the inner wall interface as a distinct perforation-induced failure mode. Zhang et al. [17] used numerical modeling to simulate the tensile and shear damage to the cement sheath caused by the pressure wave after perforation, proposing that perforation is a main cause of cement sheath failure. Su et al. [18] studied the perforated cement sheath, using compressive strength, tensile strength, shear strength, and yield strength as evaluation indicators, established a failure criterion for multi-perforation cement sheath sections, and analyzed the influence of cement sheath mechanical parameters on the cross-sectional stress of the multi-perforation cement sheath. In summary, during the penetration of the cement sheath in perforation operations, the high temperature and pressure generated by the explosion cause irreversible structural damage to the cement sheath. However, in actual perforation operations, the inner and outer walls of the cement sheath significantly affect the cementing quality after perforation. The aforementioned previous studies have overlooked the damage caused by perforation to the inner and outer walls of the cement sheath, particularly the research on fractures around the perforations.

Although the detonation shock wave during perforation imposes considerable stress on the cement sheath, potentially leading to its failure, this is merely one facet of the damage mechanism. The perforation process itself can also initiate fractures on both the interior and exterior surfaces of the sheath. These microcracks present a significant long-term risk, as they can potentially interconnect during subsequent well stimulation or production phases, establishing unwanted flow pathways and compromising zonal isolation. Experimental studies corroborate that the creation of a perforation tunnel severely degrades the cement’s sealing integrity, primarily through the development of an extensive micro-fracture network surrounding the tunnel. This degradation manifests as a loss of zonal isolation and a marked decrease in the bonding strength at both the casing-cement and cement-formation interfaces. In critical scenarios, this can result in issues such as fluid channeling or sustained casing pressure, which may induce further wellbore deformation and damage [19,20]. Fallahzadeh and Rasouli [21], through simulations of horizontal well perforations and subsequent experiments on cement samples, investigated the conditions promoting fracture and micro-annuli generation around perforations. Their findings confirmed that perforation operations substantially increase the propensity for fracture formation within the cement sheath. Lecampion et al. [22] further emphasized that perforation-induced damage extends beyond the formation to include the cement sheath body and its critical interfaces—namely the Casing–Cement sheath Interface (CCI) and the Cement sheath–Formation Interface (CFI). They highlighted that microcracks at these interfaces can become conduits for fluid migration post-perforation, ultimately impairing hydrocarbon recovery efficiency and potentially shortening the well’s operational lifespan. In light of these challenges, significant research efforts have been directed toward understanding the genesis and impact of perforation-induced microcracks in the cement sheath. For instance, Wang et al. [23] incorporated the stress intensity factor to develop a novel theoretical model for analyzing cement sheath microcracks. This model utilizes the radial stress and stress intensity factor to predict the width of interface fractures at both the CCI and CFI. Concurrently, Yan et al. [24] established a numerical wellbore perforation model to quantify how parameters like perforating charge liner diameter, cement compressive strength, and shear modulus influence the extent of the fracture damage zone in the cement sheath. Complementary experimental target tests conducted by Yan et al. [25,26] not only confirmed the presence of post-perforation microcracks and micro-annuli but also allowed for the calculation of micro-annuli propagation length during subsequent operations [27]. Furthermore, Fan et al. [28] developed a finite element model specifically designed to simulate interface fracture propagation. Their results indicated that the extension of these fractures is governed by factors such as the quality of interfacial bonding, formation mechanical properties, and the cement sheath’s own characteristics. Notably, they concluded that a higher elastic modulus in the cement, coupled with superior interfacial bond strength, effectively alleviates stress concentration at the fracture tip, thereby suppressing the progressive extension of debonding cracks. In summary, based on the collective body of research, the failure of cement sheath sealing integrity following perforation is attributed to a combination of damage within the cement matrix itself and the initiation and propagation of microcracks at its critical interfaces.

Thus, these studies, based on research into microcracks at the cement sheath-perforation interface caused by perforation, proposed corresponding cementing optimization measures and analyzed and quantified the factors that cause microcracks in the cement sheath during perforation. However, these studies all indirectly described the generation of microcracks by using cement sheath structural stress and damage degree, failing to express and analyze the patterns of cement sheath fractures directly. This issue arises mainly for two reasons: First, the generation of rock fractures in numerical simulations heavily relies on the material’s constitutive model, which requires specific damage-failure criteria to initiate fractures and accurately describe their propagation. Current research on simulating cement sheath damage mechanisms mostly quantifies the characteristics of completely failed elements in the cement sheath, without simulating the initiation and development of cracks in the cement sheath after perforation. Second, the quantification methods for generated fractures fail to accurately describe the extent of damage on the inner and outer walls of the cement sheath. In response to the shortcomings identified in prior studies, this research presents a novel fracture propagation model at the cement-sheath interface under realistic perforation conditions. By implementing the RHT constitutive model to accurately capture rock fracture mechanics, the dynamic processes of micro-crack initiation and propagation within the cement sheath under perforation impact loading are authentically simulated. Moreover, through systematic analysis of cement slurry mechanical properties and the development of an evaluation method that quantifies interface damage by measuring post-perforation crack area, this study quantitatively elucidates the influence of cement material characteristics on fracture evolution paths and failure modes. The findings offer a new theoretical framework for field cementing and completion operations, contributing to enhanced wellbore integrity in unconventional oil and gas development.

2. Numerical Model

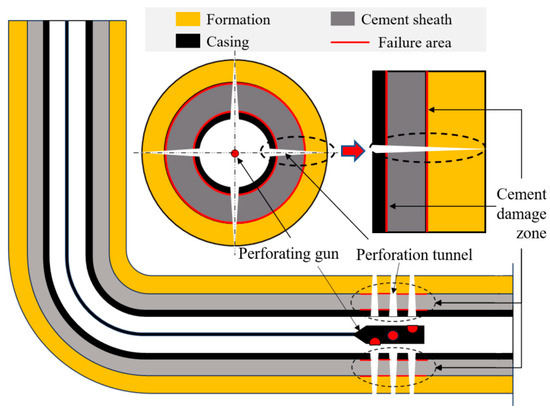

The perforation process begins with the detonation of a shaped charge, which generates a high-energy metal jet that penetrates the casing, cement sheath, and formation to create hydrocarbon flow tunnels. This intense dynamic loading imposes significant radial and circumferential stresses on the cement, inducing microcracks at its interfaces with the casing and formation. These microcracks compromise the interfacial bond, potentially leading to debonding. The schematic diagram illustrating the wellbore interface damage caused by perforation is shown in Figure 1, where the red circle indicates the location where failure has occurred. In severe cases, this creates pathways for hydrocarbon migration into the annulus, resulting in channeling and resource loss. This study quantitatively investigates the interface damage and microcrack formation in the cement sheath caused by this perforation load.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of cement sheath interface damage during perforation.

2.1. Geometry Model and Meshing

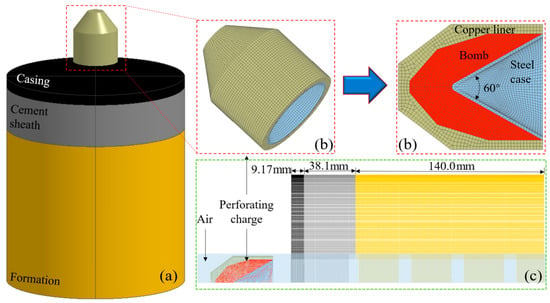

Considering that the penetration of the wellbore-assembly structure by the metal jet generated from explosive perforation is a fluid–structure interaction process with complex boundary conditions, an air domain was added to the numerical model as the propagation medium for the jet, in addition to establishing the actual wellbore geometry. The established air domain only envelops the motion path of the metal jet. Considering the symmetry of actual perforation operations and the complexity of perforation itself, a 1/4 perforation cement target model was established while ensuring calculation accuracy. The complete perforation cement target model (after two symmetries) is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Geometry and mesh of the perforation cement target model. (a) Assembly of the perforated cement-target assembly; (b) Meshing of the perforating charge; (c) Meshing of the assembly.

Based on the actual wellbore structure and relevant practical perforation engineering parameters, a geometric model of the perforation cement target was established. The wall thickness of the casing structure of the wellbore section was set to 9.17 mm, and the cement target wall thickness was set to 38.1 mm. The numerical models employed a perforating charge with a 30 mm liner (which governs jet formation), a thickness of 2 mm, a 60° cone angle, a 40 mm case diameter, and a 48 mm overall height [29]. All models maintained consistent charge parameters to ensure comparative validity.

Figure 2 illustrates the meshing strategy employed for the numerical model. Given that the primary focus of this study is on the jet formation dynamics and the resultant damage to the cement target, mesh refinement was preferentially applied to the air domain and the casing–cement target assembly. Conversely, a coarser mesh, with an element size 1.5 times larger, was adopted for the formation to optimize computational efficiency without compromising the resolution in critical regions. The refined meshing for the air and casing-cement target regions is essential for accurately capturing the jet development and casing damage.

To address the severe mesh distortion caused by large deformations during the explosive detonation, the perforating charge components (liner, explosive, and charge case) and the air domain were simulated using the Arbitrary Lagrange–Euler (ALE) algorithm. This approach effectively handles the extreme deformation and free flow of the metal jet. In contrast, the casing–cement–formation (CCF) assembly was modeled using the Lagrange algorithm. A fluid–structure interaction coupling method was defined at the interface between the ALE and Lagrange domains to ensure proper mechanical transfer.

The model initiation was configured using a conventional point detonation method, with the detonation point located at the intersection of the wellbore central axis and the interface between the charge case and the explosive. To simulate in situ conditions, a confining pressure was applied to the outer boundary of the formation, with the load curve set to 15 MPa (covering the entire perforation process) to replicate deep formation confinement. Meanwhile, free boundary conditions were assigned to the top and bottom surfaces to approximate an infinite formation extent. Furthermore, to minimize numerical inaccuracies caused by explosion-induced shock wave reflections, all external regions were assigned non-reflective boundaries.

2.2. Governing Equations

2.2.1. ALE Equations of State

The explosive part of the perforating charge uses the HIGH_EXPLOSIVE_BURN material model, and the detonation wave generated by the explosion uses the JWL equation of state. The pressure peos generated by the detonation products is calculated by the JWL (Jones–Wilkins–Lee) equation of state [30,31,32]:

where peos is the pressure generated by the explosive detonation, V is the volume of detonation products per unit volume of charge, E is the internal energy per unit volume of charge; A, B, R1, R2, and ω are material constants.

The liner, typically made of copper for its superior penetration performance, is suitably characterized by the JOHNSON_COOK constitutive model and the MIE_GRUNEISEN equation of state [33,34]. This material model is particularly effective for simulating high-strain-rate scenarios and accounting for thermal softening under adiabatic conditions. It accurately captures the strength evolution of metals at elevated temperatures and strain rates, making it widely adopted in modeling the formation of detonation-driven metal jets [31,35]. The expression for its yield stress is given as:

where A, B, C, n, and m are all material constants, is the equivalent plastic strain and is the normalized equivalent plastic strain rate, T* is the normalized tensile strength, T* = T/fc, and T is the tensile strength of the material.

The MIE_GRUNEISEN equation of state is a mature solid-state equation of state in explosion mechanics and high-pressure physics, which can accurately describe the dynamic behavior of metal materials under high-temperature, high-pressure, and high-strain-rate conditions [36,37]. Its equation of state can be expressed as Equation (3):

where pH and EH are the pressure and internal energy along the solid Hugoniot curve, respectively; pc and Ec are the pressure and internal energy of the compressed solid material; ρ is the material density; and γ is the Grüneisen coefficient.

The equation of state for air uses the Linear_Polynomial EOS, which describes the mechanical behavior of an ideal gas under ideal conditions. In LS-DYNA, the linear polynomial EOS calculates pressure by:

where μ is the relative volume, dimensionless; E1 is the internal energy per unit volume of the material, J; and C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, and C6 are material constants.

2.2.2. Wellbore Assembly Equations of State

The casing was modeled with the *PLASTIC_KINEMATIC material model, which describes its elastic-plastic response under impact loading with kinematic hardening. The model incorporates strain rate effects via the Cowper-Symonds equation [35], where the yield stress is scaled by:

where τ is the cumulative time of plastic strain, s, is the deviator of rock plastic strain.

For the rock constitutive model, Ridel et al. [38] proposed the RHT constitutive model, which is based on the HJC constitutive model. This constitutive model uses a pore compaction model that more realistically reflects microscopic physical processes within the material (such as crack propagation) and better simulates the initiation and propagation laws of cracks during cement target compression and tensile failure [39,40]. As this study mainly focuses on cement target interface damage and fractures, emphasizing the crack propagation history of the cement target material, the RHT material constitutive model is adopted for the cement target in the simulation.

The RHT model employs a tensile damage evolution law and a tensile failure criterion, introducing three limit surfaces: the failure surface, the elastic limit surface, and the residual strength surface. The relationships between parameters are shown in Equations (7)–(9), respectively [41,42]:

where σf is the equivalent strength on the failure surface, MPa; is the equivalent stress intensity function of the quasi-static failure surface compression meridian, dimensionless; R3(θ) is a function of the Lode angle θ, dimensionless; Frate(ε) is the strain rate correlation function, dimensionless; σel is the elastic limit stress, MPa; Fe is the elastic scaling function, dimensionless; FCAP(p) is the cap function, dimensionless; is the normalized residual surface strength, MPa; B, M are residual strength surface parameters, dimensionless; and p* is the normalized pressure, MPa.

In addition to the introduction of the aforementioned three limit surfaces, the RHT material constitutive model also includes a damage calculation method based on equivalent plastic strain and the material’s tensile properties. The cumulative damage calculation method is shown in Equations (10) and (11) [43]:

where εp is the increment of equivalent plastic strain; εp,f is the final failure equivalent plastic strain; D1, D2 are damage constants; and εf,min is the minimum failure strain.

2.3. Parameter Design

The explosive material uses the MAT_HIGH_EXPLOSIVE_BURN material model and the JWL equation of state. The specific parameters are shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

Explosive material parameters.

The specific parameters for the liner and charge case are shown in Table 2 below:

Table 2.

Liner and charge case material model and equation of state parameters.

The air material model uses the MAT_NULL material model with the Linear_Polynomial EOS. Its material parameters are = 1.293 × 10−3 g/cm3, C0 = C1 = C2 = C3 = C6 = 0, C4 = C5 = 0.4.

Table 3.

The RHT model parameters of the cement target.

3. Calculation Process and Model Result

During cement target fracture generation caused by downhole perforation operations, due to their high speed and invisibility, it is impossible to observe how the cement target damage process develops. When analyzing fracture patterns at cement target interfaces caused by perforation, it is necessary to consider the fracture initiation point, the cement target’s development history, and its failure mode. Therefore, numerical simulation is used to investigate the development laws and failure mechanisms of cement target fractures after perforation.

3.1. Analysis of the Perforation Operation Process

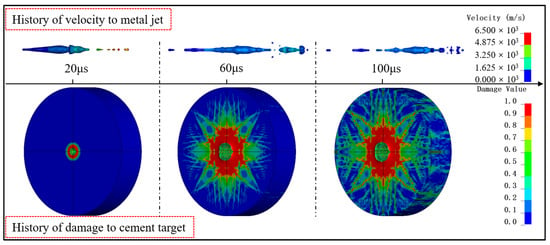

The perforation-induced failure of the cement target is an instantaneous event, driven by the detonation force and high temperature, which cause the metallic liner to rapidly deform into a penetrating jet. As illustrated in Figure 3, the fracture evolution within the cement target during this penetration can be categorized into three distinct stages: fracture initiation, propagation, and full development.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of perforated cement target interface damage.

Fracture Initiation Stage: After the explosive in the perforating charge detonates, it melts and compresses the metal liner, forming a jet. Under the action of the detonation wave, the maximum velocity of the jet can reach 6500 m/s at 0–20 μs. The metal jet begins to penetrate the cement target and causes local damage at the inner cement wall, perforating a hole, at which point fractures begin to initiate.

Fracture Propagation Stage: During the period of 20–60 μs, as the jet penetrates the cement target, the jet head is gradually compressed, and its velocity rapidly slows down to 1500 m/s. At this time, a large-area failure has occurred at the perforated hole in the cement target, and fractures are beginning to propagate.

Complete Fracture Development Stage: After the jet fully penetrates the cement target (60–100 μs), the jet head begins to dissipate, and the velocity gradually slows down. The interface failure of the cement target stops developing. At this point, the main fractures are fully developed, and additional microcracks have formed.

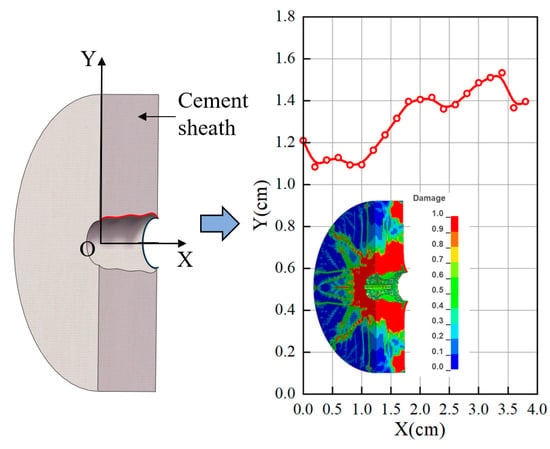

3.2. Analysis of Cement Target Failure

As the jet penetrates the interior of the cement target, failure occurs around the perforated hole at the inner cement wall, simultaneously initiating fractures that extend outward, generating four main fractures and many microcracks. During the penetration process, in addition to the failure around the perforated hole mentioned above, large-area failure also occurs inside the cement target, as shown in Figure 4. The figure shows that the internal hole diameter of the cement target first decreases and then increases along the jet direction. The hole diameter at the outer wall is 0.2 cm larger than that at the inner cement wall, which is because when the cement target is penetrated by the jet, creating two holes, the impact of the plane on the cement target causes compressive failure. The hole at inner cement wall is caused by conical fractures forming when the location exceeds the unconfined compressive strength. When the jet penetration breaks through to the outer wall, it exerts a tensile action on the area around the hole at this interface. Therefore, the hole at this interface is caused by tensile spalling and shear plugging, which is the result of free surface tension caused by the reflected stress wave [40,46,47].

Figure 4.

The diameter variation of the cement target perforated hole.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Influence of Cement Target Material Properties

There are many factors contributing to severe cement target failure during perforation operations, among which the quality of the cement target itself is particularly significant. Therefore, this section focuses on analyzing the variation law of damage degree at the inner and outer walls of the cement target after perforation caused by the cement target’s compressive strength and shear modulus through controlled variables, thereby laying the foundation for research on maintaining wellbore integrity after perforation by improving the mechanical properties of the cement slurry.

4.1.1. Cement Target Compressive Strength

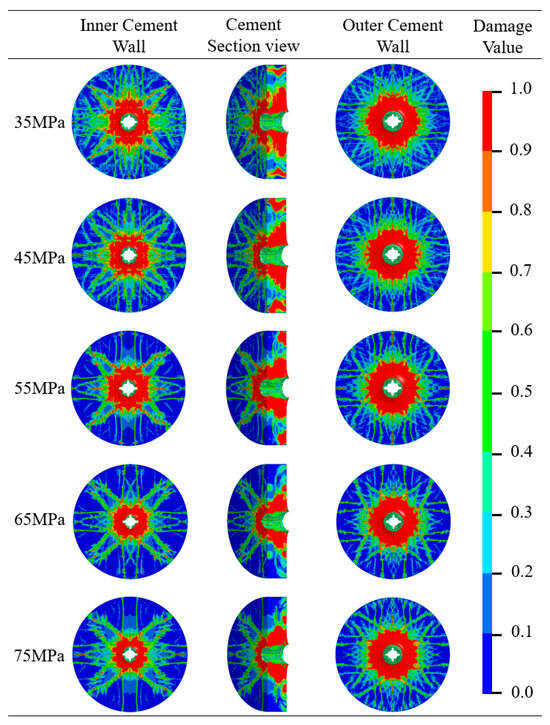

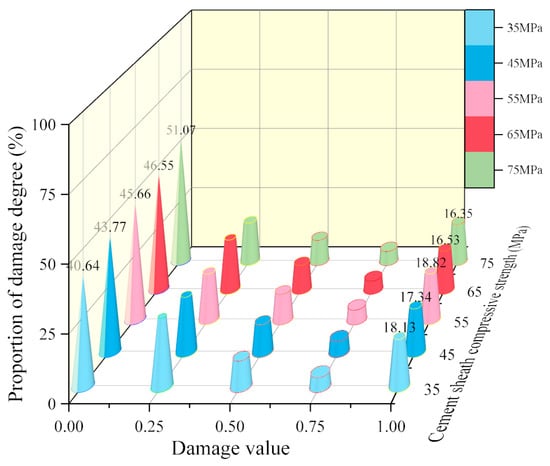

To investigate the correlation between the cement target’s compressive strength and the damage evolution at its dual interfaces, a parametric analysis was conducted with strength values set at 35, 45, 55, 65, and 75 MPa. After numerical calculations using the perforation cement target model, the damage state of the cement target under different compressive strengths after the perforation operation was analyzed, while keeping other conditions constant. The specific damage situation is shown in Figure 5:

Figure 5.

Damage nephogram of a perforated cement target under different cement compressive strength.

- (a)

- Under the condition of constant cement target material compressive strength, the hole diameter and damage area at the outer wall of the cement target after perforation are significantly larger than those at the inner cement wall, and the microcracks generated at the outer wall are all tensile and shear cracks (because tensile and shear failure mostly occur around the hole at the outer wall), with no main fractures (because the reflected stress is small compared to the perforation detonation pressure).

- (b)

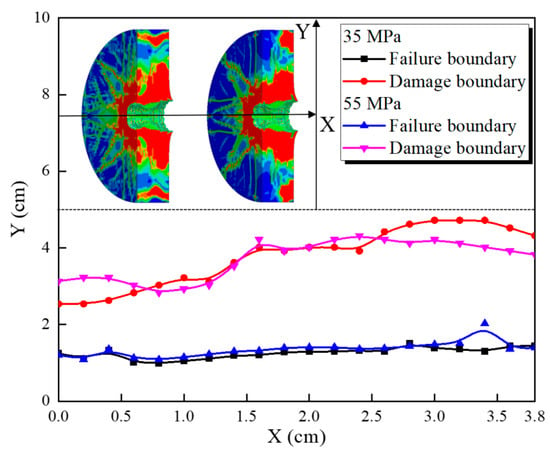

- As the compressive strength increases (35 MPa to 75 MPa), the degree of damage at the inner wall shows a significant decrease, and the number of microcracks decreases significantly; however, the reduction in damage at the outer wall is not apparent. This phenomenon also indicates that the damage at the outer wall is mainly tensile and shear failure. Figure 6 shows the variation law of the perforation tunnel radius and damage radius along the jet direction for cement targets with 35 MPa and 55 MPa compressive strength.

Figure 6. Comparison of perforated cement target tunnel radius and damage radius results after perforation.

Figure 6. Comparison of perforated cement target tunnel radius and damage radius results after perforation.

As evidenced in Figure 6, an increase in the compressive strength of the cement material leads to a corresponding reduction in the diameter of the complete failure zone within the target, with a maximum observed decrease of 0.4 cm. Notably, the perforation tunnel radius remains largely unaffected by the variation in compressive strength. This indicates that enhancing the compressive strength effectively confines the damage extent in the cement without altering the primary perforation tunnel geometry.

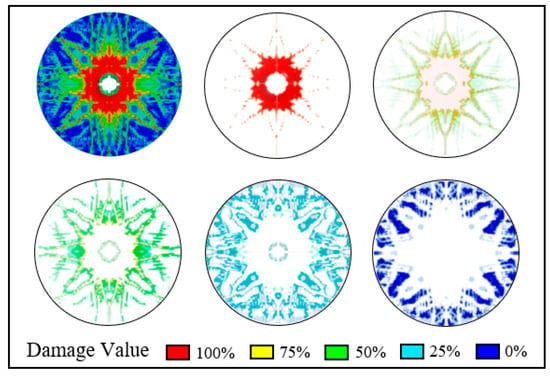

In the cement target damage nephogram, different colors indicate the degree of damage to the cement target. To quantitatively analyze the damage degree of cement targets with different compressive strengths caused by perforation, image processing software was used to extract the areas characterized by damage colors from the damage nephograms of the inner and outer walls. The extracted regions were normalized, i.e., the area of each different damage degree color was divided by the area of the interface after perforation. The extraction process is shown in Figure 7 (taking cement target compressive strength of 35 MPa as an example).

Figure 7.

Percentage of cement target damage degree (characterized by color).

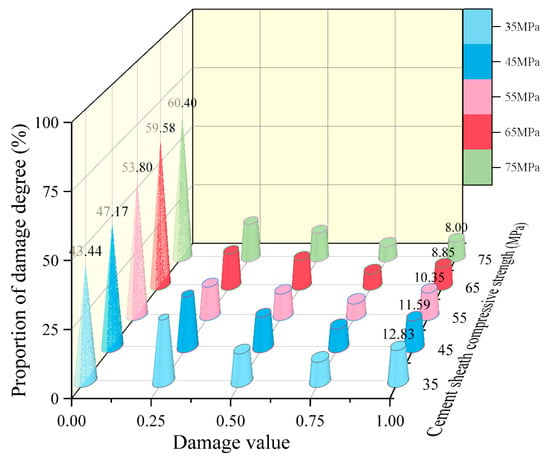

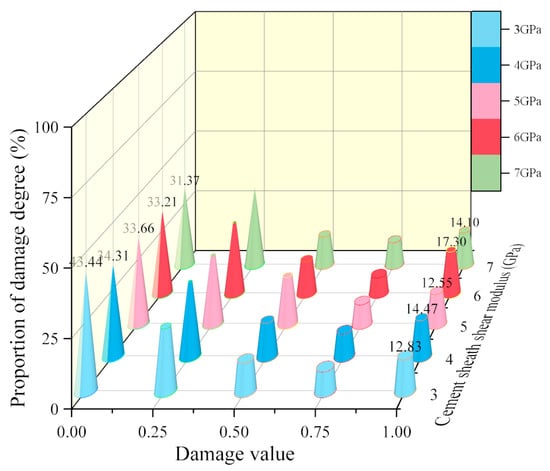

The percentages of damage degree for the inner and outer walls of cement targets with different cement material compressive strengths are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively:

Figure 8.

Percentage of inner wall of the cement target damage degrees under different cement compressive strength.

Figure 9.

Percentage of outer wall of the cement target damage degrees under different cement compressive strength.

- (a)

- Figure 8 demonstrates a positive correlation between the cement’s compressive strength fc and the undamaged area at the inner wall, consequently indicating a reduction in interface damage. For instance, at fc = 75 MPa, the undamaged area accounts for 60.4%, with only 8% classified as failed, underscoring the role of high compressive strength in mitigating damage. An anomaly, however, is observed at fc = 55 MPa, where the failed area exceeds that at fc = 45 MPa, suggesting a potential non-monotonic or threshold-dependent relationship that requires further experimental verification.

- (b)

- From Figure 9, it can be seen that as the compressive strength of the cement material increases, the variation law of the damage degree of the outer wall of the cement target is the same as that of the inner wall. Still, the trends in the undamaged and failed areas at the outer wall are weaker than those at the inner wall, indicating that the effect of cement compressive strength on the inner wall is stronger than that on the outer wall.

- (c)

- The comparative data from Figure 8 and Figure 9 reveal that, for an equivalent cement compressive strength, the complete failure area at the outer wall substantially exceeds that at the inner wall. This marked disparity is exemplified at fc = 75 MPa, where the proportion of complete failure area at the outer wall (16.44%) is more than twice that of the failure area at the inner wall (8.00%).

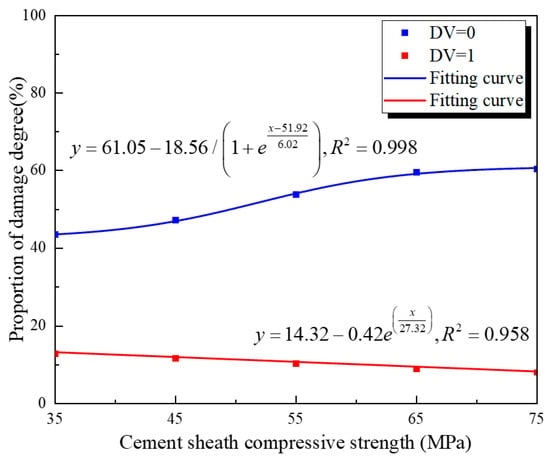

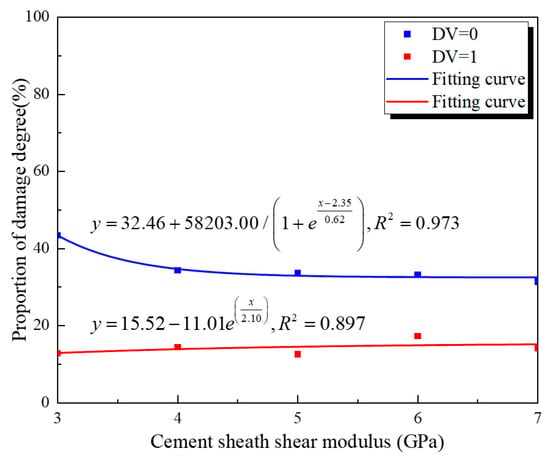

Figure 10 and Figure 11 show the fitting curves for the inner and outer walls of the cement target at damage values (DVs) of 0 and 1 (representing no damage and complete damage, respectively). From the figures, it can be concluded that the compressive strength has a greater impact on the damage at the inner cement wall than at the outer wall. When the cement material’s compressive strength increases from 35 MPa to 75 MPa, the proportion of undamaged area at the inner wall increases by 16.6%, while that at the outer wall increases by only 11.2%. At the same time, for both the inner and outer walls, the influence of compressive strength on the DV = 0 fitting curve is greater than that on DV = 1. This occurs because during the perforation process, when the metal jet penetrates the inner cement wall, the inner wall experiences compressive failure. As the jet further advances toward the outer cement wall, attenuation of the jet and blockage by the formation cause the jet tip to collapse. This generates tensile stress around the hole at the outer wall, leading to damage in the peripheral region of the outer cement wall [46]. This indicates that increasing compressive strength effectively inhibits the development of the damaged area, i.e., microcracks, at both the inner and outer walls.

Figure 10.

The inner cement wall’s damage values under different cement compressive strengths.

Figure 11.

The outer cement wall’s damage values under different cement compressive strengths.

4.1.2. Cement Target Shear Modulus

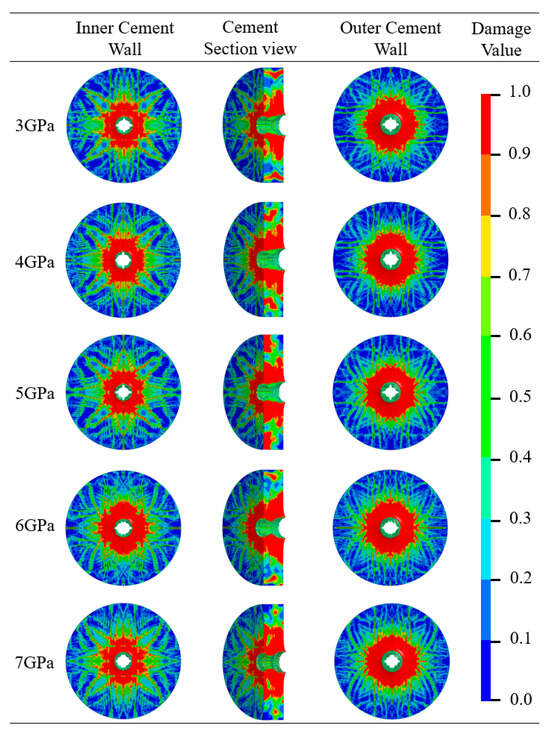

Beyond compressive strength, the shear modulus of cement is a crucial mechanical property for ensuring sheath integrity. Holding the compressive strength constant at 35 MPa, this study systematically investigated the influence of the shear modulus (varied from 3 to 7 GPa) on the post-perforation damage at the inner and outer walls. The resultant damage patterns, analyzed to elucidate the failure mechanism under different shear moduli, are presented in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Damage nephogram of a perforated cement target under different cement shear modulus.

From Figure 12, it can be seen that as the shear modulus increases, the microcracks at the inner and outer walls of the cement target become more complex. This is because, during perforation, the impact load generates shear stress. If the shear modulus of the cement material is low, it is more prone to plastic deformation or rupture under shear stress, leading to damage. Cement materials with a high shear modulus are more brittle and prone to cracking under impact. Materials with low shear modulus may absorb energy through plastic deformation, reducing crack propagation, thus resulting in less damage.

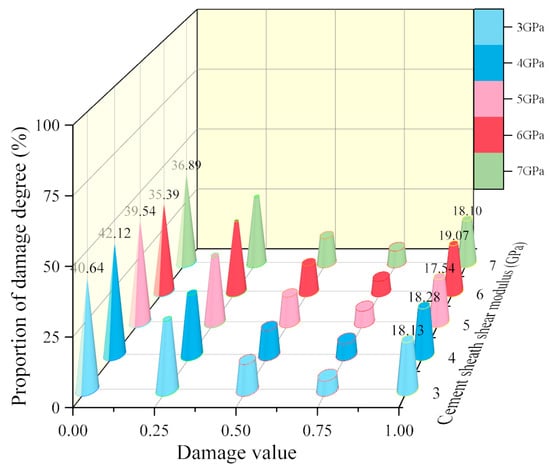

From the above analysis, it can be concluded that the shear modulus of the cement material is closely related to its damage degree. A higher shear modulus may cause the material to undergo brittle failure more easily under perforation impact, generating more cracks, thereby increasing the damage degree; while a lower shear modulus may allow the material to absorb energy through plastic deformation, reducing crack propagation, but may lead to greater local damage, potentially affecting sealing performance [48]. Therefore, there is an optimal range of shear modulus to balance crack resistance and deformation capacity, thereby minimizing damage. Consequently, it is necessary to quantitatively study the relationship between the cement material shear modulus and the damage degree, as shown in Figure 13 and Figure 14:

Figure 13.

Percentage of the inner wall of the cement target damage degrees under different cement shear modulus.

Figure 14.

Percentage of the outer wall of the cement target damage degrees under different cement shear modulus.

- (a)

- The relationship between the inner cement wall’s damage degree and the shear modulus is presented in Figure 13. The data reveal an inverse correlation: as the cement’s shear modulus increases, the undamaged area at the inner wall progressively contracts, signifying aggravated damage. This trend is further corroborated by the propensity for high-shear-modulus cement to generate a greater density of micro-cracks, a phenomenon consistent with the observed mechanical response despite the stable proportion of the fully failed area.

- (b)

- Figure 14 shows the relationship between the outer cement wall’s damage degree and the shear modulus. From this figure, it can be seen that the variation pattern of the outer wall with the cement material shear modulus is the same as that of the inner wall. High shear modulus leads to increased interface damage intensity, while low shear modulus can limit the development of microcracks.

- (c)

- It is worth noting that when G = 5 GPa, the proportions of failed area at the inner and outer walls of the cement target are both the smallest, at 12.55% and 17.54%, respectively. Therefore, a cement material with G = 5 GPa can be selected to prevent wellbore sealing failure due to severe cement target failure after perforation.

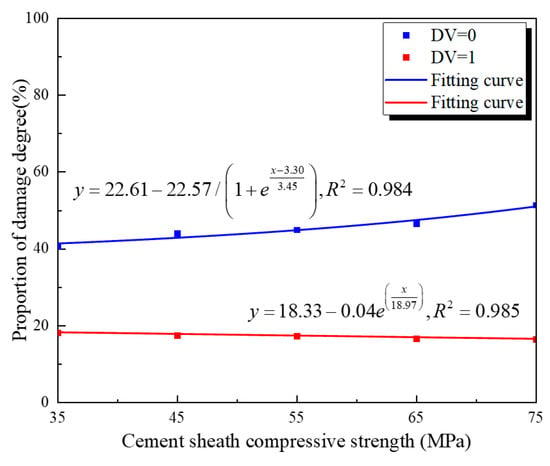

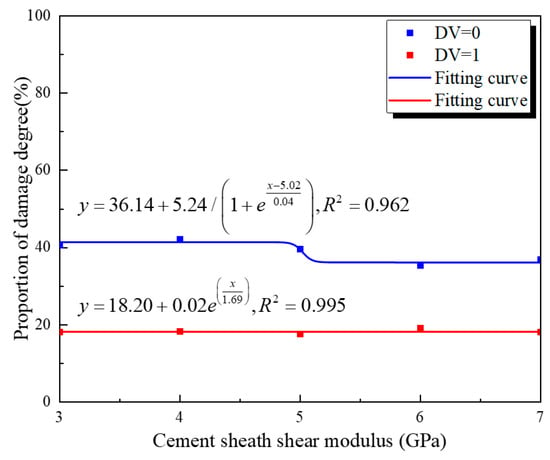

Figure 15 and Figure 16 show the fitting curves for the inner and outer walls of the cement target, at DV = 0 and DV = 1. From the statistics, it can be concluded that the shear modulus has a greater impact on the damage at the inner wall than at the outer wall. When the cement material’s shear modulus increases from 3 GPa to 7 GPa, the proportion of undamaged area at the inner wall decreases by 10.2%, while that at the outer wall remains almost unchanged. For both the inner and outer walls, the influence of the shear modulus on the DV = 0 fitting curve is greater than that on DV = 1. This indicates that reducing the cement material shear modulus can effectively inhibit the development of microcracks.

Figure 15.

The inner cement wall’s damage values under different cement shear modulus.

Figure 16.

The outer cement wall’s damage values under different cement shear modulus.

4.2. Influence of Formation Material Properties

The lithology of the formation affects the stress transmission and distribution generated during the perforation process. The material properties of the formation jeopardize its ability to absorb the stress wave generated by perforation. Therefore, analyzing the influence of the formation’s geological conditions on the damage of the cement target can help reduce cement target damage and analyze fracture propagation laws.

4.2.1. Formation Compressive Strength

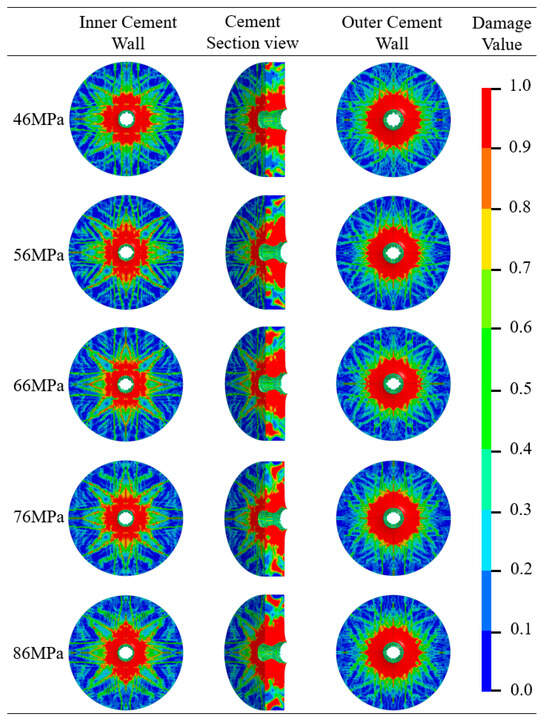

The damage nephograms of the cement target corresponding to different formation compressive strengths are shown in Figure 17. From the figure, it can be concluded that the formation compressive strength has a weak influence on the damage of the cement target, but a lower formation compressive strength can better inhibit the development of main fractures at the inner wall.

Figure 17.

Damage nephogram of the perforation cement target under different formation compressive strength.

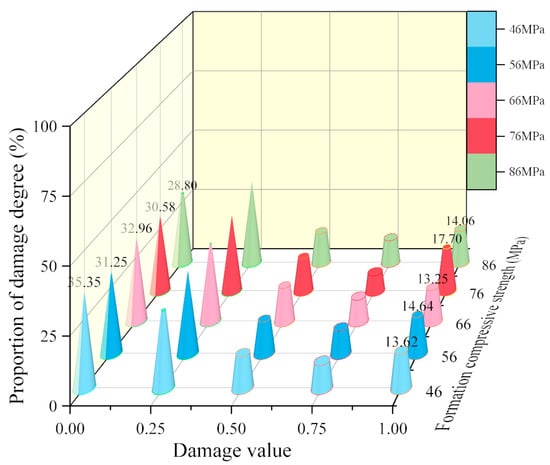

Using the same image processing method as in Section 4.1.1, the areas of different damage degrees were normalized to analyze the proportion of different damage values. The processing results are shown in Figure 18 and Figure 19. As the formation compressive strength increases, the proportion of DV = 0 at both the inner and outer walls decreases, while the proportion of DV = 1 increases, indicating that the damage degree at both interfaces gradually increases.

Figure 18.

Percentage of the inner wall of the cement target damage degrees under different formation compressive strength.

Figure 19.

Percentage of the outer wall of the cement target damage degrees under different formation compressive strength.

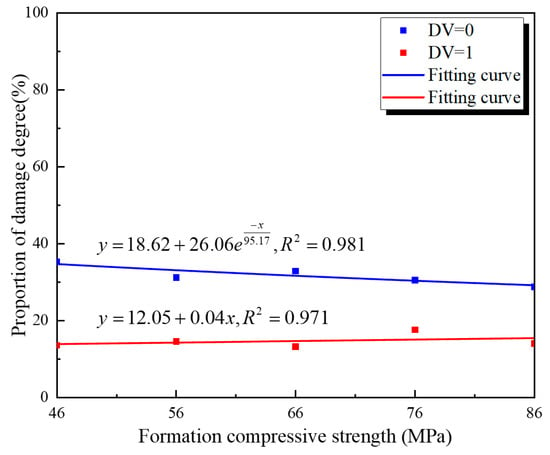

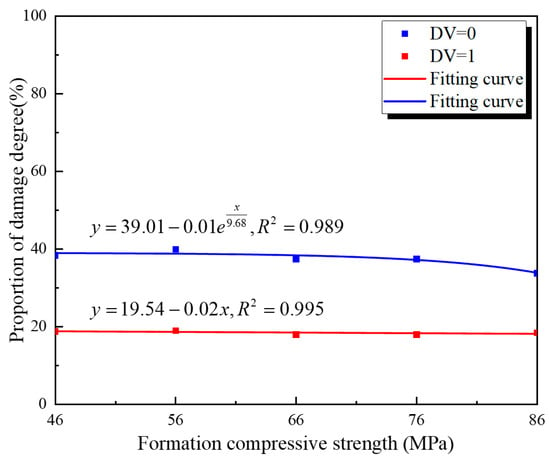

Data for DV = 0 and DV = 1 for the inner and outer walls of the cement target were fitted. The fitting curves are shown in Figure 20 and Figure 21. From the figures, it can be concluded that the formation compressive strength has a negligible influence on damage at both the inner and outer walls. When the formation compressive strength increases from 46 MPa to 86 MPa, the proportion of failed area at the inner wall of the cement target increases by only 1.6%. In contrast, the proportion of failed area at the outer wall decreases by only 0.8%. However, the damage degree of both interfaces shows approximately linear increases with increasing formation compressive strength. This is because formations with lower compressive strength are more likely to absorb the stress wave and undergo plastic deformation during perforation, thereby reducing the impact of the reflected stress wave on the cement sheath.

Figure 20.

The inner cement wall’s damage values under different formation compressive strengths.

Figure 21.

The outer cement wall’s damage values under different formation compressive strengths.

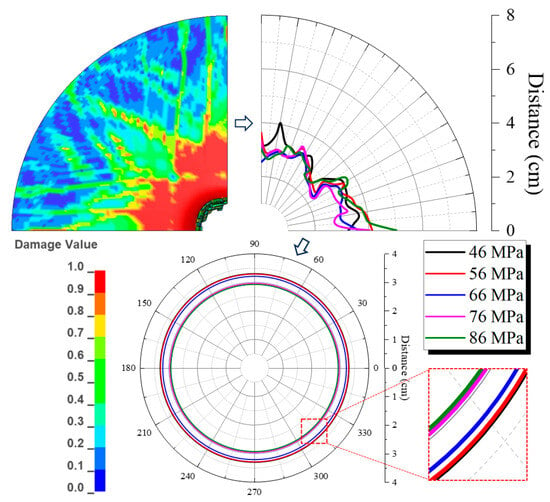

To further analyze the influence of the formation compressive strength on the failure of the inner wall of the cement target, the failure boundary coordinates of the inner wall were extracted, converted to polar coordinates, and the average diameter was calculated. Then, the comparison of the cement target failure range under different formation compressive strengths was analyzed. The comparison result is shown in Figure 22. From the figure, it can be seen that as the formation compressive strength increases, the failure diameter of the cement target gradually decreases, and the maximum reduction occurs when the formation compressive strength increases from 56 MPa to 66 MPa, with a decrease of 0.4 cm.

Figure 22.

Comparison of the inner cement wall’s failure diameters under formation compressive strengths.

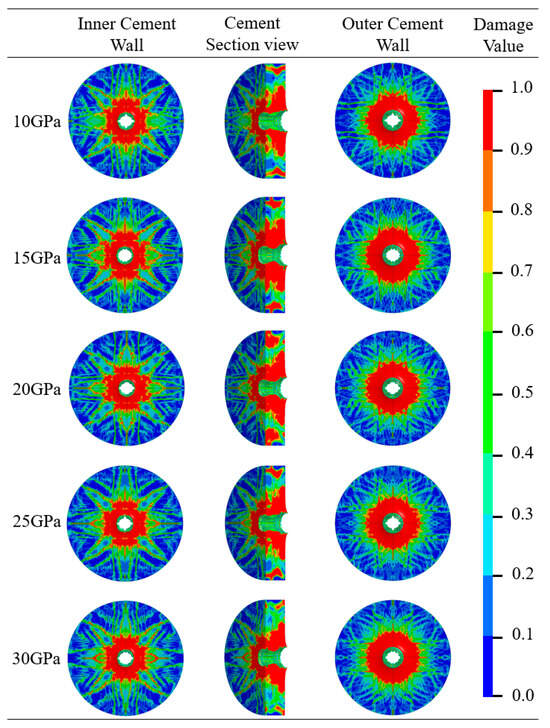

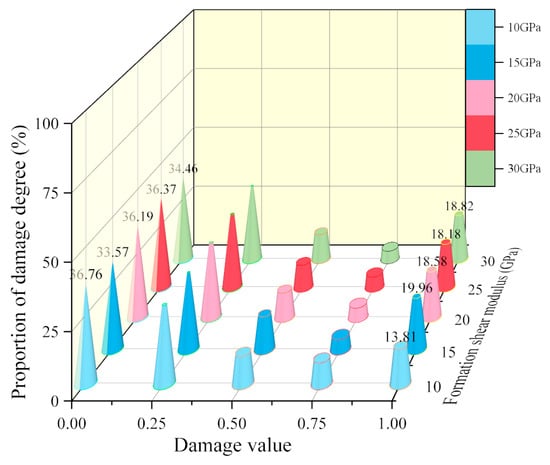

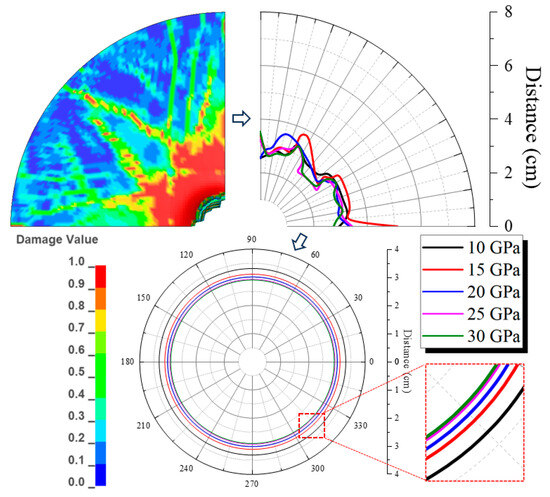

4.2.2. Formation Shear Modulus

A parametric study was conducted to evaluate the influence of formation shear modulus on the integrity of the inner and outer walls. While holding other parameters constant, numerical simulations were performed with the formation shear modulus varying between 10 GPa and 30 GPa. The resultant damage nephograms (Figure 23) reveal that the interfaces exhibit minor sensitivity to this parameter, with no conspicuous changes in damage extent observed across the range. To quantitatively assess this limited influence, the damage data were post-processed to precisely quantify the effect on both interfaces.

Figure 23.

Damage nephogram of the perforation cement target under different formation shear modulus.

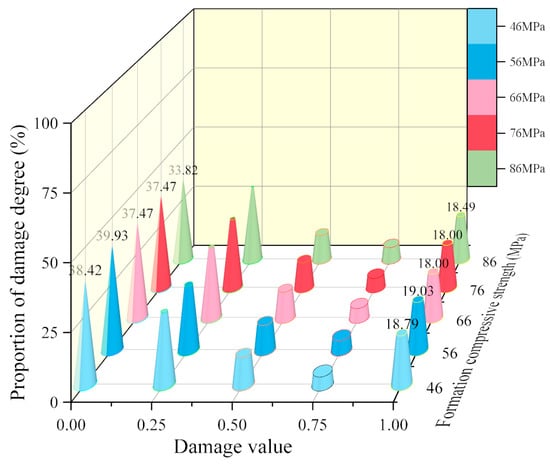

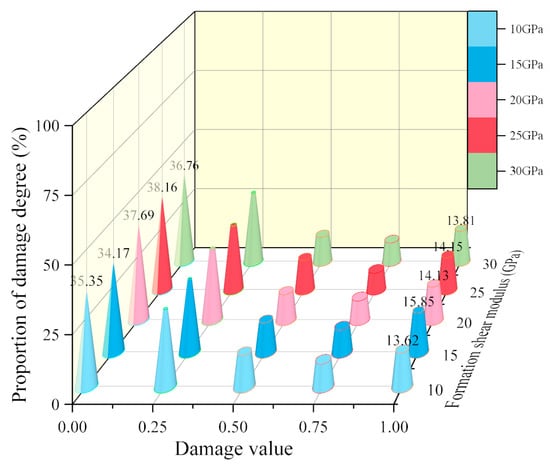

From Figure 24 and Figure 25, it can be seen that the proportion of undamaged area at both inner and outer walls first decreases, then increases, and then decreases again as the formation shear modulus increases. The proportion of undamaged area at the inner wall reaches a minimum value of 34.17% when the formation shear modulus G = 15 GPa, and reaches a maximum value of 38.16% when G = 25 GPa. Moreover, when G = 15 GPa, the proportion of completely damaged area at the inner wall is the largest, at 15.85%. The proportion of undamaged area at the outer wall reaches a minimum value of 33.57% when the formation shear modulus G = 15 GPa, and reaches a maximum value of 36.76% when G = 10 GPa. Moreover, when G = 15 GPa, the proportion of completely damaged area at the outer wall is the largest, at 19.96%, indicating that when the formation shear modulus is 15 GPa, the perforation damage to the cement target is the greatest.

Figure 24.

Percentage of the inner wall of the cement target damage degrees under different formation shear modulus.

Figure 25.

Percentage of the outer wall of the cement target damage degrees under different formation shear modulus.

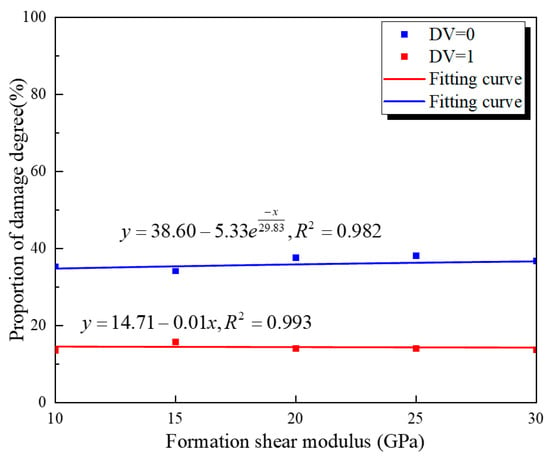

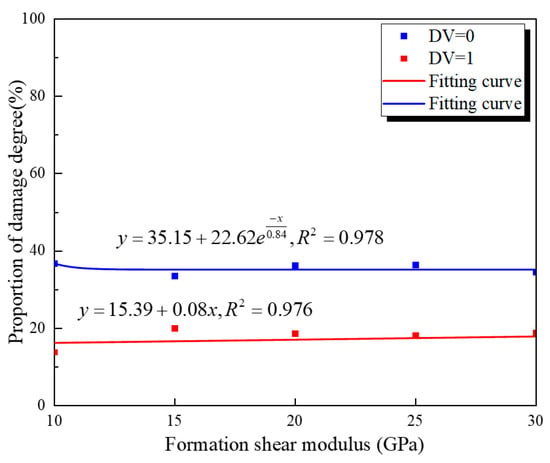

Data for DV = 0 and DV = 1 for the inner and outer walls of the cement target were fitted. The fitting curves are shown in Figure 26 and Figure 27. From the figures, it can be concluded that the formation shear modulus has a negligible effect on damage at both the inner and outer walls. The damage degree of both interfaces hardly changes with the increase in the formation shear modulus.

Figure 26.

The inner cement wall’s damage values under different formation shear modulus.

Figure 27.

The outer cement wall’s damage values under different formation shear modulus.

To quantitatively assess the influence of formation shear modulus on inner wall’s failure, the interface’s failure boundary was extracted, converted into polar coordinates, and its average radius was computed. A comparison of this failure metric across different moduli is presented in Figure 28. The results demonstrate an inverse relationship: the failure diameter contracts as the formation shear modulus increases. The most significant reduction of 0.4 cm occurs when the modulus rises from 10 GPa to 15 GPa, indicating that a stiffer formation more effectively confines damage at the inner wall.

Figure 28.

Comparison of the inner cement wall’s failure diameters under different formation shear modulus.

5. Conclusions

This study investigates the influence of high-velocity jets during perforation operations, focusing on the microcracks generated within the cement target body and at its interfaces. A numerical model was established to simulate high-speed jet penetration through the casing–cement target–formation assembly. By utilizing the proportion of different damage levels in the cement target after perforation as evaluation factors, the influence of various mechanical parameters of the cement target and formation on the development of microcracks in the cement target body and at its interfaces was analyzed, leading to the following main conclusions:

- (1)

- A numerical model of high-speed jet penetration through the casing–cement target–formation assembly was developed using fluid–structure interaction algorithms. The evolution of metal jet morphology during perforation was analyzed, along with its impact on the inner and outer walls of the cement target during penetration, revealing the aperture variation patterns within the cement target.

- (2)

- The influence of cement material compressive strength on interface damage of the cement target during perforation was investigated. Results demonstrate that increasing compressive strength effectively suppresses the development of microcracks in partially damaged areas. When cement compressive strength increases from 35 MPa to 75 MPa, the undamaged area ratio on the inner wall increases by 16.6%, compared to 11.2% on the outer wall, indicating greater influence on inner wall damage. Therefore, in actual field perforation operations, using high-strength cement can more reliably ensure the integrity of the cement target after perforation.

- (3)

- The effect of cement shear modulus on interface damage of the cement target post-perforation was examined. Variations in cement shear modulus show a more significant impact on inner wall damage compared to the outer wall. As cement shear modulus increases from 3 GPa to 7 GPa, the undamaged area ratio on the inner wall decreases by 10.2%, while the outer wall remains largely unaffected.

- (4)

- The influence of formation physical parameters on interface damage of cement targets during perforation was investigated. Increasing the formation compressive strength and shear modulus can reduce the damage on both the inner and outer walls of the cement target; however, the extent of reduction is significantly more limited compared to the effects of altering cement material properties. As the formation compressive strength and shear modulus increase, the failure diameter of the cement target decreases, with the maximum reduction (0.4 cm) occurring when the formation compressive strength increases from 56 MPa to 66 MPa or the shear modulus increases from 10 GPa to 15 GPa.

Author Contributions

Writing—review and editing, Y.X.; funding acquisition, Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; resources, J.H.; investigation, X.S.; supervision, J.Z.; data contribution, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52374001), Chongqing Natural Science Foundation (CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX0882), and Foundation of the State Key Laboratory of Petroleum Resources and Engineering (PRE/open-2408).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52374001) for the financial support. The authors also thank all the participants for their help and friendship.

Conflicts of Interest

Author J.H. and J.Z. were employed by the company CNPC Xibu Drilling Engineering Co., Ltd. Author M.L. was employed by the company TEDA Sea Star Shipping Engineering Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Shen, N.; Wang, Y.F.; Peng, H.; Hou, Z.P. Renewable Energy Green Innovation, Fossil Energy Consumption, and Air Pollution—Spatial Empirical Analysis Based on China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.N.; Li, S.X.; Bo, X.; Liu, H.L.; Ma, F. Revolution and significance of “Green Energy Transition” in the context of new quality productive forces: A discussion on theoretical understanding of “Energy Triangle”. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 1611–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Yao, Y.; Chen, P.H.; Li, J.; Wang, H.T.; Li, H. Investigation of casing stress distribution and parameter optimization during the transient impact process of multi-hole perforation operations. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 155, 107761. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, H.; Ge, H.K.; Yao, Y.; Shen, Y.H.; Wang, J.C.; Bai, J.; Zhang, Z.D. A new insight into casing shear failure induced by natural fracture and artificial fracture slip. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 137, 106287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Fan, Z.H. Key technologies for increasing production based on the best practices of major shale oil and gas basins. Energy Geosci. 2025, 6, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.X.; Li, Q.E.; Liu, W.; Zhao, X.R.; Zhang, S.R. Optimization of perforation parameters for horizontal wells in shale reservoir. Energy Rep. 2025, 7, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Guan, Z.C.; Han, L.H.; Liu, Y.H. Coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical analysis of perforated cement sheath integrity during hydraulic fracturing. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 218, 110950. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, H.; Jin, Y.; Qu, H.; Lu, Y.H. Experimental investigation and correlations for proppant distribution in narrow fractures of deep shale gas reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2022, 19, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.Z.; Zhang, S.S.; Cheng, N.; Tian, G.; Zeng, D.Z.; Yu, H.Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Erosion characteristics and simulation charts of sand fracturing casing perforation. Pet. Sci. 2023, 20, 3638–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, G.; Han, F.; Wu, J.M.; Yuan, P.J.; Fu, S.S.; Ma, Y. Dynamic simulation of double-cased perforation in deepwater high temperature and high-pressure oil and gas wells. Pet. Sci. 2024, 21, 3482–3495. [Google Scholar]

- Kareem, H.J.; Hasini, H.; Abdulwahid, M.A. Effect of perforation density distribution on production of perforated horizontal wellbore. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorogood, J.L.; Younger, P.L. Discussion of “Oil and gas wells and their integrity: Implications for shale and unconventional resource exploitation” by Davies, R.J., Almond, S., Ward, R.S., et al. (Marine and Petroleum Geology 2014). Mar. Pet. Geol. 2015, 59, 671–673. [Google Scholar]

- King, G.E.; Valencia, R.L. Well integrity for fracturing and re-fracturing: What is needed and why. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 9–11 February 2016; Society of Petroleum Engineers: Richardson, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Gao, D.L.; Zeng, J.; Wang, Z.X. Study on cement sheath integrity in horizontal wells during hydraulic fracturing process. In Proceedings of the 52nd U.S. Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–20 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, Y.H.; Yang, H.; Zhao, L.Y.; Guo, S.L.; Liu, H.J.; Ma, X.L. Stress concentration of perforated cement sheath and the effect of cement sheath elastic parameters on its integrity failure during shale gas fracturing. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 980920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.M.; Kuru, E.; Jin, Y.; Yang, X.X. Numerical investigation of the factors affecting the cement sheath integrity in hydraulically fractured wells. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 215, 110582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.Y.; Wu, Z.Q.; Cheng, X.W.; Sun, X.L.; Zhang, C.M.; Zhou, M. Mechanical properties of high-ferrite oil-well cement used in shale gas horizontal wells under various loads. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 319, 126067. [Google Scholar]

- Su, D.; Li, Z.; Huang, S.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Xue, Y.T. Experiment and failure mechanism of cement sheath integrity under development and production conditions based on a mechanical equivalent theory. Energy Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 2400–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecampion, B.; Bunger, A.; Zhang, X. Interface debonding driven by fluid injection in a cased and cemented wellbore: Modeling and experiments. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2013, 18, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Jin, J.Z.; Fan, L.F.; Guo, X.L.; Shen, J.Y.; Li, J. Research on the establishment of gas channeling barrier for preventing SCP caused by cyclic loading-unloading in shale gas horizontal wells. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahzadeh, S.; Rasouli, V.; Sarmadivaleh, M. An investigation of hydraulic fracturing initiation and near-wellbore propagation from perforated boreholes in tight formations. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2014, 48, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecampion, B.; Bunger, A.; Zhang, X. Numerical methods for hydraulic fracture propagation: A review of recent trends. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 49, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.B.; Liu, K.; Gao, D.L. Investigation of the interface cracks on the cement sheath stress in shale gas wells during hydraulic fracturing. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 205, 108981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Guan, Z.C.; Xu, Y.Q.; Yan, W.J.; Wang, H.T. Numerical investigation of perforation to cementing interface damage area. J. Pet. Sci. Engineering. 2019, 179, 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Guan, Z.C.; Yan, W.J.; Wang, H.T. Mechanical response and damage mechanism of cement sheath during perforation in oil and gas well. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 188, 06924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Guan, Z.C.; Xu, Y.Q.; Yan, W.J.; Chen, W.Q. Study on Debonding Issue of Cementing Interfaces Caused by Perforation with Numerical Simulation and Experimental Measures. SPE Drill. Complet. 2020, 35, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Guan, Z.C.; Zhang, B.; Chen, W.Q. Numerical investigation of debonding extent development of cementing interfaces during hydraulic fracturing through perforation cluster. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 197, 107970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhu, Z.M.; Zhao, Y.L.; Zhou, C.L.; Zhang, X.S. The effects of some parameters on perforation tip initiation pressures in hydraulic fracturing. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 176, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North Schlumberger, STimStream Isobaric Deep-Penetration Projectiles. 2017. Available online: http://www.north-slb.com/Product/detail/id/32.html (accessed on 1 July 2017).

- Chen, C.Y.; Shiuan, J.H.; Lan, I.F. The Equation of State of Detonation Products obtained from cylinder expansion test. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 1994, 19, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- LSTC. L.S.D. Keyword User’s Manual II; Livermore Software Technology Corporation (LSTC): Livermore, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Guo, X.Q.; Liu, Z.J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Q.Y. Pressure field investigation into oil&gas wellbore during perforating shaped charge explosion. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 172, 1235–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuzé, O. General form of the Mie–Grüneisen equation of state. C. R. Méc. 2012, 340, 679–687. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, W.Q.; Zhang, P.; Xie, J.M.; Hou, M.Y.; Wang, Z.J.; Bai, X.F. Investigation of impact performance of perforated plates and effects of the perforation arrangement and shape on failure mode. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 140, 106638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.B.; Li, J.; Yang, H.W.; Liu, G.H.; Lian, W.; Wang, B.; Zhang, G. A new investigation on optimization of perforation key parameters based on physical experiment and numerical simulation. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 13997–14008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zeng, X.G.; Chen, H.Y.; Wang, Y.T.; He, L.; Wang, F. Molecular dynamics investigation on complete Mie-Grüneisen equation of state: Al and Pb as prototypes. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 808, 151702. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.S.; Yao, C.B.; Wang, P.; Cheng, L.D.; Ying, W.J. Physics-informed data-driven cavitation model for a specific Mie–Grüneisen equation of state. J. Comput. Phys. 2025, 524, 113703. [Google Scholar]

- Riedel, W.; Thoma, K.; Hiermaier, S.; Schmolinske, E. Penetration of reinforced concrete by Beta-B-500 numerical analysis using a new macroscopic concrete model for hydrocodes. In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Interaction of the Effect of Munitions with Structures, Berlin, Germany, 3–7 May 1999; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Kader, M. Modified settings of concrete parameters in RHT model for predicting the response of concrete panels to impact. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2019, 132, 103312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, H.; Cheng, Y.H. A modified bond-based peridynamic approach for rigid projectile perforation on concrete slabs. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2025, 195, 105102. [Google Scholar]

- Pattajoshi, S.; Ray, S. Dynamic fracture analysis of multi-layer composites using an improved RHT model. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 325, 111220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.L.; Tang, Z.Q.; Liu, J.M.; Zhong, L.; Yuan, Q.; Li, X.H.; Pan, H.; Yao, X.H. Improvement to RHT constitutive model for predicting dynamic impact performance of UHPC structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 489142, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.; Xu, X.Y.; Ren, W.J.; Liu, S.; Jiang, J.Z. Determination and application of the RHT constitutive model parameters for ultra-high-performance concrete. Structures 2024, 69, 107488. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.B.; Han, Z.X.; Guo, H.J.; Wang, T.; Liu, B.; Wang, D.G. Numerical simulation damage analysis of pipe-cement-rock combination due to the underwater explosion. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 105, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, G.Y. Research on Mechanism of Shaped Charge Perforation in Deep Shale Reservoir; China University of Mining and Technology: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Li, W.B.; Ding, C.F.; Gao, D.C.; Shi, Z.; Liang, J.G. Numerical and analytical investigations on projectile perforation on steel–concrete–steel sandwich panels. Results Eng. 2020, 8, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, P.; Kucewicz, M.; Małachowski, J.; Sielicki, P.W. Failure behavior of a concrete slab perforated by a deformable bullet. Eng. Struct. 2021, 245, 112832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Justin, J.P.; Arthur, G.B.; Mukiibi, S.I.; Yan, C.L.; Cheng, Y.F. Mechanisms of near-wellbore fracture growth considering the presence of cement sheath microcracks and their implications on wellbore stability. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 309, 110422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.