Abstract

The increasing digitization of critical infrastructure and the increasing use of Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) systems are leading to a significant increase in the exposure of operating systems to cyber threats. The integration of information (IT) and operational (OT) layers, characteristic of today’s industrial environments, results in an increase in the complexity of system architecture and the number of security events that require ongoing analysis. Under such conditions, classic approaches to monitoring and responding to incidents prove insufficient, especially in the context of systems with high reliability and business continuity requirements. The aim of this article is to analyze the possibilities of using Large Language Models (LLMs) in the protection of industrial IoT systems operating in critical infrastructure. The paper analyzes the architecture of industrial automation systems and identifies classes of cyber threat scenarios characteristic of IIoT environments, including availability disruptions, degradation of system operation, manipulation of process data, and supply-chain-based attacks. On this basis, the potential roles of large language models in security monitoring processes are examined, particularly with respect to incident interpretation, correlation of heterogeneous data sources, and contextual analysis under operational constraints. The experimental evaluation demonstrates that, when compared to a rule-based baseline, the LLM-based approach provides consistently improved classification of incident impact and attack vectors across IT, DMZ, and OT segments, while maintaining a low rate of unsupported responses. These results indicate that large language models can complement existing industrial IoT security mechanisms by enhancing context-aware analysis and decision support rather than replacing established detection and monitoring systems.

1. Introduction

The progressive digitization of critical infrastructure and the dynamic development of Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) systems are leading to fundamental changes in the way technical systems of key importance for the functioning of the economy and national security are designed, operated and managed. The integration of information systems (IT) with industrial automation and operating systems (OT) makes it possible to increase the efficiency of processes, improve monitoring and remotely manage distributed infrastructure, but at the same time it significantly increases the complexity of the system architecture and their vulnerability to cyber threats [1,2,3].

Cybersecurity in industrial environments should be considered not only in terms of information protection, but above all as an issue of ensuring the continuity of technological processes and the safety of people and the environment. The literature emphasizes that the decision to digitize industrial processes is strategic and involves the need for systemic risk management, involving people, processes and technologies [1]. This is particularly important for critical infrastructure, the disruption of which can lead to cascading effects on a local and national scale [4].

The architecture of industrial IoT systems is characterized by heterogeneity of devices, dispersion of data sources, and the need to meet stringent requirements for reliability and deterministic response times. Transmission and telecommunication systems used in industrial environments are designed for continuous operation in difficult operating conditions, which further complicates the implementation of classic cybersecurity mechanisms known from IT systems [2]. The conceptual framework and safety models of industrial automation systems have been formalized in the ISO/IEC 62443 standard, which is the basis for hazard analysis and security design in OT and IIoT systems [3].

In response to the growing importance of cyber threats in critical infrastructure, legal regulations are also being introduced, which impose on organizations the obligation of a systemic approach to risk management and the responsibility of management for the level of implemented security. An example is the NIS2 Directive, which aims to ensure a high and uniform level of cybersecurity in key sectors of the European Union economy [4]. These regulations emphasize the need for continuous monitoring of threats, responding to incidents and improving the mechanisms for the protection of ICT systems.

The literature on the subject is dominated by approaches to the protection of industrial IoT systems based on classical machine learning methods, used in intrusion detection systems, network traffic analysis and anomaly detection in process data [5,6,7]. However, review work indicates significant limitations of these methods, in particular in terms of scalability, adaptation to changing operating conditions and interpretability of results in complex industrial environments [5].

In recent years, there has been a dynamic development of research on the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) in the area of cybersecurity. These models, thanks to their ability to process sequences of events, heterogeneous data and unstructured information, have begun to be used in cyberattack prediction systems, hybrid intrusion detection systems and automation of incident analysis processes in IoT environments [8,9,10,11]. These studies indicate that LLMs can effectively support the correlation of security events and the identification of attack patterns that are difficult to detect using traditional algorithms.

An important direction of research is also the application of LLMs in the context of industrial IoT systems and OT environments. Literature reviews on the integration of large language models into the IoT ecosystem highlight their potential for system log analysis, process data interpretation, and operational decision-making support in environments with a high degree of technical complexity [9,12]. At the same time, the authors draw attention to the challenges associated with their practical application, such as computational requirements, processing delays, and the need to ensure reliability and deterministic operation of systems [7,13].

In the context of critical infrastructure, research on the integration of LLMs with safety systems with high requirements for interpretability and compliance is of particular importance. Work on IoT security frameworks based on a combination of machine learning, explainable artificial intelligence and large language models points to the possibility of increasing the effectiveness of threat detection while maintaining transparency in the decision-making process [14,15,16]. In addition, there are studies in the literature analyzing the use of LLMs to automate compliance processes with standards and regulations in the area of cybersecurity, which is important for organizations operating in the critical infrastructure sectors [17].

Recent research published in 2025 highlights a growing interest in the application of large language models to cybersecurity challenges in IoT and industrial IoT environments. Comprehensive surveys indicate that LLMs are increasingly considered as flexible reasoning components capable of integrating heterogeneous data sources, yet their practical deployment in security-critical industrial systems remains limited and insufficiently explored [18]. Existing works primarily focus on data-centric paradigms such as federated learning, digital twins, or ontology-based modeling, without addressing the operational task of cybersecurity incident triage under IT/OT architectural and organizational constraints [19,20]. At the same time, recent analyses of industrial control system security emphasize that current protection mechanisms remain largely detection-oriented and lack effective tools for contextual interpretation and decision support in complex industrial environments [21]. These findings reveal a clear research gap regarding the role of large language models as decision-support tools for incident analysis in industrial IT/OT and IIoT systems, which is addressed in this study.

Despite the intensive development of research on the application of artificial intelligence and large language models in cybersecurity, the analysis of the literature indicates insufficient recognition of their role in the protection of industrial IoT systems of critical infrastructure, taking into account the specifics of OT systems and business continuity requirements. This gap justifies the need for further architectural and conceptual research to identify potential roles of LLMs in cybersecurity systems of industrial IIoT environments.

The following research hypothesis was adopted: large language models can effectively support the triage process of cybersecurity incidents in industrial IT/OT and IIoT environments, improving the quality of event classification and the usefulness of action recommendations compared to a simple rule model, with an acceptable level of hallucinations and maintaining the requirements of OT environments.

Most existing AI- and machine-learning-based approaches to industrial IoT security focus on pattern recognition tasks, such as anomaly detection, intrusion classification, or rule generation, typically operating on structured feature representations and optimized for predictive accuracy. In contrast, the approach proposed in this study treats large language models not as classifiers, but as a semantic triage layer operating on heterogeneous, partially structured SOC artifacts. This layer integrates incident descriptions, telemetry context, architectural constraints, and operational limitations into a unified reasoning process that supports decision-oriented analysis rather than isolated predictions.

As a result, the theoretical contribution of this work lies in reframing the role of AI in IIoT security from detection-centric automation toward context-aware incident interpretation and prioritization. By explicitly modeling impact classes, entry vectors, and actionable responses within a constrained operational setting, the proposed framework provides a complementary perspective to existing deep learning and hybrid systems, emphasizing semantic integration and decision support over raw detection performance.

This study makes the following original contributions to the field of industrial cybersecurity. First, it proposes a structured conceptual framework for applying large language models to the triage of cybersecurity incidents in industrial IT/OT and IIoT environments, explicitly accounting for operational constraints and business continuity requirements. Second, it introduces a risk-oriented classification of incident effects (deny, degrade, disrupt, destroy) and demonstrates how this classification can be operationalized within LLM-assisted analysis. Third, the paper presents a controlled experimental protocol based on synthetic yet realistic SOC incident scenarios, enabling a systematic comparison between LLM-based triage and a rule-based baseline. Finally, the study explicitly addresses the risks associated with LLM deployment in OT environments, including hallucinations and limited observability, and proposes practical mitigation mechanisms grounded in expert supervision and architectural context.

The structure of the article is as follows: the first chapter justifies the importance of cybersecurity in critical infrastructure and reviews the state of research on AI/LLM. Next, threats are characterized, the effects of attacks are classified (deny, degrade, disrupt, destroy) and the role of risk analysis in high-risk environments is indicated. The third chapter describes the adopted qualitative method of IT/OT architecture analysis, threat scenarios and risk areas in critical infrastructure. A model of a reference IT/OT architecture, a set of cyber threat scenarios, classification of attack effects, identification of risk areas and a detailed experiment with LLM for triage of incidents (synthetic SOC tickets, ground truth labels, metrics: accuracy, MacroF1, hallucinations, actionability) are built. The results of identifying cyber threat scenarios, architectural vulnerabilities, attack vectors, and security decisions in IT/OT architectures are shown in the result section. The whole work is summed up with final conclusions.

2. Cybersecurity of Industrial Automation

Ensuring the cybersecurity of industrial automation systems is one of the key challenges in critical infrastructure environments, where technological processes are strongly dependent on the correct operation of control, monitoring and teletransmission systems. The security of information and automation systems should be treated as an integral element of the security of the entire organization, and the protection procedures and technical requirements used must be subject to continuous improvement in response to changing technological and environmental threats [1,2].

Information security is traditionally defined by ensuring the confidentiality, integrity, availability and authenticity of the processed data [1]. In practice, it is the information processed in ICT systems that very often becomes the subject of cyber incidents, both intentional and accidental. However, this definition does not fully reflect the fact that the condition for information processing is the proper functioning of ICT networks and systems. From a system perspective, and, in particular, for industrial automation systems, additional characteristics such as performance, reliability and integrity of the systems are therefore crucial [2,3].

Threats to the performance of industrial automation systems can manifest themselves in delays in data transmission or slow data processing, which in industrial environments can lead to situations where important alarm signals reach operators with a delay, preventing the appropriate response [2]. Reliability risks can result in unexpected shutdowns of systems, including safety systems, and these failures are not always immediately noticeable to operational personnel. On the other hand, a violation of the integrity of industrial automation systems may lead to their modification in a way that causes incorrect reactions to process signals, for example, by continuing the operation of devices despite exceeding the established alarm thresholds [3].

The hazards described may be the result of human error, technical faults or environmental factors. Increasingly, however, they are the result of deliberate cyber activities aimed at influencing not only the information layer, but also physical processes. The literature emphasizes that modern cyberattacks on industrial automation systems are designed to have real-world effects, which increases their potential harmfulness and the pressure exerted on the organizations that target them [3,4].

Cyberattacks on industrial automation systems are most often classified due to their impact on the functioning of systems and technological processes. There are four basic categories of effects of such attacks: denying, degrading, disrupting, and permanently damaging or destroying system resources [3,5]. This classification is the basis for further risk analysis and identification of the most vulnerable facilities and technological processes.

Identification of the above safety properties is crucial for conducting an effective risk analysis in industrial automation systems. This process requires identifying the most likely objects and their processes that may be affected by cyber incidents, as well as assessing the potential consequences of their disruption. For this reason, cybersecurity of industrial automation systems should be treated as an element of risk management of strategic importance, supporting informed decision-making regarding the level of acceptable risk and the scope of security measures applied [1,4]. Particularly high requirements in the field of cybersecurity apply to industrial facilities characterized by complex technological processes carried out in environments with increased operational risk. In this type of installation, industrial automation systems not only perform the function of process control, but also directly support safety systems, responsible for monitoring critical parameters and initiating protective actions. Disruptions to these systems, resulting from reduced availability, degradation of performance or breach of the integrity of process data, can lead to consequences that go beyond economic losses, including risks to human health and the environment. For this reason, industrial environments with a high degree of automation and a close connection between IT and OT systems are a particularly important context for cyber risk analysis and the design of automation system protection mechanisms.

Recent domain-specific studies and guidelines published in 2024–2025 emphasize that cybersecurity challenges in industrial automation and OT/ICS environments differ fundamentally from those observed in classical IT systems. These challenges result from deterministic and time-critical communication, the use of legacy and proprietary industrial protocols, strict safety and availability requirements, and limited observability of process-level events. Updated industrial cybersecurity standards and threat landscape reports indicate that such constraints significantly influence threat modeling, incident detection, and response strategies, as cyber incidents may directly affect physical processes and safety-related functions. Moreover, recent analyses of ICS incidents show that attack vectors in OT environments frequently exploit remote access mechanisms, engineering workstations, and supply-chain dependencies rather than traditional IT vulnerabilities. Consequently, contemporary OT/ICS-oriented literature stresses the necessity of security analysis approaches that explicitly account for architectural segmentation, process context, and operational constraints when designing protection mechanisms for highly automated industrial environments [22,23,24,25].

3. Materials and Methods

This section presents the methodological framework adopted to investigate the applicability of large language models for cybersecurity incident triage in industrial IT/OT and IIoT environments. The methodology is structured as a sequential workflow, progressing from the definition of a reference architecture and threat scenarios, through the construction and annotation of a synthetic SOC dataset, to the execution and evaluation of an LLM-assisted triage procedure. The individual methodological stages are described in the following subsections and formally summarized in Algorithm 1, which defines the complete experimental workflow.

3.1. Reference IT/OT Architecture Model

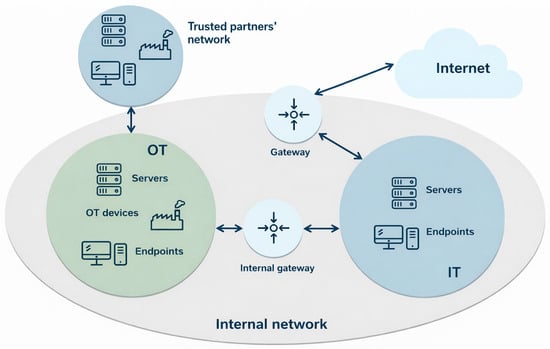

The basis for the analyses was the reference IT/OT network architecture, including separate segments of operational technology (OT), information technology (IT) and connections to external networks, including the Internet and networks of external partners. This architecture reflects typical solutions used in complex industrial installations, where automation systems, surveillance systems and telecommunications infrastructure are closely interconnected [26].

In the analyzed model, special attention was paid to the points of contact between the IT and OT segments, implemented through network gateways and intermediary systems, which are potential attack vectors and key elements of security policy enforcement.

3.2. Analysis of Cyber Threat Scenarios

The threat analysis was carried out on the basis of cyber incident scenarios, describing possible ways of influencing industrial automation systems and their surroundings. These scenarios were developed on the basis of:

- Operating experience of automation systems;

- Documented cyber incidents in critical infrastructure;

- Industry reports and post-burglary analyses [27,28,29].

Each scenario was analyzed in terms of the impact on the functioning of control systems, safety systems and decision-making processes carried out by operators.

3.3. Classification of the Effects of Cyberattacks

The analysis adopted a classification of the effects of cyberattacks based on their impact on the functioning of industrial automation systems, including four categories: deny, degrade, disrupt and destroy. This classification allows for a clear link between the type of attack and its potential operational and technical consequences and is consistent with the approaches used in cyber-physical incident analysis [27,30].

3.4. Identifying Risk Areas

Based on the analysis of the architecture and threat scenarios, key risk areas were identified, including, in particular:

- Telecommunications and alarm systems;

- Operational supervision and visualization systems;

- Remote access mechanisms;

- Systems supporting decision-making processes.

The identification of these areas was the basis for further considerations on the possibility of supporting analysis and incident response processes using AI-based tools [30,31,32,33]. The identified risk areas and architectural constraints constitute the input assumptions for the LLM-assisted incident triage procedure.

3.5. Using LLMs to Support Incident Triage in IIoT/OT Environments

The objective of this stage is to formalize the procedure by which a large language model is used to support the initial triage of cybersecurity incidents in industrial IT/OT and IIoT environments. The proposed approach does not involve autonomous decision-making or direct interaction with industrial systems. Instead, the LLM is treated as a decision-support component assisting human analysts in incident classification, interpretation, and response prioritization under operational constraints.

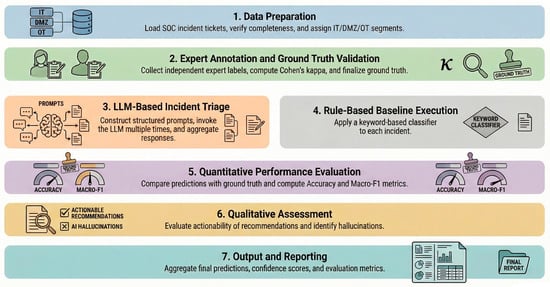

To ensure methodological clarity and reproducibility, the complete triage workflow is defined as a sequential procedure encompassing data preparation, expert validation, repeated LLM inference, baseline comparison, and quantitative as well as qualitative evaluation. This procedure is formally specified in Algorithm 1, while its conceptual workflow is visually summarized in Figure 1.

| Algorithm 1. LLM-assisted incident triage workflow for industrial IT/OT and IIoT environments |

|

Figure 1.

Workflow of the LLM-assisted SOC incident triage procedure corresponding to Algorithm 1, source: own study.

Figure 1 illustrates the sequential stages of data preparation, expert annotation and validation, LLM-based triage, rule-based baseline execution, quantitative performance evaluation, qualitative assessment of actionability and hallucinations, and final result aggregation. The experiment did not involve autonomous decision-making by the model or control of industrial equipment. The role of the LLM has been limited to supporting the security analyst, in particular in the field of incident classification, identification of potential attack vectors and organizing information from distributed IoT/IIoT sources.

Experimental dataset

Due to the lack of access to the actual operational data of critical infrastructure, the experiment used a synthetic set of security incident reports (so-called SOC tickets), developed on the basis of previously identified cyber threat scenarios, vulnerabilities and IT/OT architecture.

The dataset included a total of 60 incident reports, balanced against four categories of cyberattack impacts:

- Deny—preventing access to systems or data;

- Degrade—a decrease in efficiency or correctness;

- Disrupt—temporary interruption of the functioning of systems;

- Destroy—permanent damage or destruction of resources.

Each application contained:

- A brief description of the incident;

- Contextual information on the criticality of the process;

- Description of the architecture (IT/DMZ/OT segment, gateways, remote connections);

- A set of artifacts in the form of sample logs (e.g., firewall, IDS, IIoT edge systems, surveillance systems);

- Simplified telemetry from IoT/IIoT devices;

- Operational limitations specific to OT environments (e.g., inability to restart devices during operation).

Ground truth

For each incident report, a set of reference labels has been prepared, including:

- The category of the cyber-attack effect (Deny/Degrade/Disrupt/Destroy);

- The most likely vector of entry into the infrastructure;

- The main vulnerability that allows the attack to be carried out;

- Expected set of reactionary actions.

The labeling was carried out independently by two experts and the compliance of the assessments was verified using the Cohen factor κ. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus, creating a final set of reference data used to evaluate the model’s performance.

Due to the lack of access to data from industrial critical infrastructure environments, the experimental dataset was constructed using a structured, scenario-driven synthetic approach. The primary objective was to ensure realism and diversity of cases rather than to generate arbitrary or random incidents. Each SOC ticket was derived from a predefined incident scenario reflecting cybersecurity events commonly reported in industrial IT/OT and Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) environments. The scenario design was informed by documented real-world incidents and surveys of attacks targeting industrial control systems, supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) platforms, and cyber–physical infrastructures, including unauthorized remote access, manipulation of process data, loss of availability of supervisory systems, and indirect cascading effects originating from supporting IT systems [17,34,35,36]. All scenarios were explicitly mapped onto a reference IT/OT architecture and constrained by operational characteristics typical of industrial environments. These constraints included limited system observability, restricted logging capabilities, the presence of legacy industrial protocols, and strict availability requirements, which are widely reported as defining features of real industrial incidents [34,37]. Telemetry artifacts were simulated as time-stamped measurements generated by IIoT sensors and edge devices, representing abnormal operating states, threshold violations, or communication anomalies. Log artifacts consisted of structured excerpts representative of firewalls, gateways, intrusion detection systems, and supervisory platforms. In addition, operational constraints—such as the inability to restart devices, apply patches, or perform intrusive diagnostics during production cycles—were explicitly encoded within each ticket to preserve consistency with real OT operating conditions [37]. The final dataset comprised 60 SOC tickets, a size selected to balance scenario diversity, architectural representativeness, and feasibility of expert validation. Tickets were evenly distributed across four impact categories (deny, degrade, disrupt, destroy), with 15 cases per category, ensuring class balance and enabling meaningful quantitative comparison of classification performance while maintaining manual oversight of scenario realism.

Tasks carried out by the LLM model

For each incident report, the LLM received a complete set of information contained in the tick and was asked to generate a structured response including:

- Classification of the impact of the incident (Deny/Degrade/Disrupt/Destroy).

- Identification of the most likely attack vector.

- Indication of the main architectural or operational susceptibility.

- A short justification of the decision based solely on the data provided.

- A proposal for reactionary actions in three time horizons:

- ∘

- Immediate;

- ∘

- Short-term;

- ∘

- Long-term;

- The declared level of certainty of the answer.

Model responses were generated in a standardized format to enable quantitative comparisons.

Experimental protocol and evaluation metrics

For each submission, the experiment was conducted in three independent model runs with a low randomness parameter value, and the results were aggregated by majority voting. A simple baseline model based on dictionary rules is used as a baseline.

The effectiveness of LLMs was assessed using the following measures:

- Accuracy and Macro-F1 measures for classification of incident effects;

- Accuracy of attack vector identification;

- Expert assessment of the usefulness of recommended actions;

- Hallucination rate, understood as the percentage of responses containing information that is absent from the input or does not comply with the limitations of OT environments.

To limit hallucinations during real-time operation, the LLM was constrained to use only information explicitly provided in the incident ticket, including descriptions, logs, telemetry, and operational limitations. In addition, structured response schemas and the explicit option to indicate insufficient evidence were enforced to prevent unsupported inference and speculative recommendations.

3.6. Limitations of the Method

The methodology used does not allow for a quantitative assessment of the effectiveness of individual security mechanisms or a comparison of technical solutions in real conditions. Its aim is to structure expert knowledge, identify typical threat patterns and identify areas where analytical tools based on large language models can be applied.

The identified risk areas formed the basis for the identification of specific architectural and organizational vulnerabilities, which are presented in the results chapter.

Although the analysis is based on synthetically generated incident scenarios, they are designed to reflect realistic industrial architectures, operational constraints, and threat classes specific to IT/OT and IIoT environments. Therefore, the main limitations of the proposed approach are not due to the lack of realism of the scenarios, but to the implementation conditions, such as the organizational variability of SOC teams, the evolution of industrial systems architecture, limited data availability and integration, and the role of analysts in the decision-making process.

The identified risk areas formed the basis for the identification of specific architectural and organizational vulnerabilities, which were presented in the results chapter, and at the same time indicate directions for further validation of the proposed approach using operational data from real industrial environments.

4. Results

In the context of this study, industrial IoT (IIoT) devices constitute the primary source of telemetry and event data used for cybersecurity analysis. These devices include distributed sensors, edge controllers, and network-connected automation components that continuously generate data streams describing the physical state of industrial processes. The proposed LLM-based analysis does not operate directly on the devices themselves but processes and interprets data originating from IIoT components, integrating it with IT/OT security events to support incident classification and decision-making.

4.1. Identified Cyber Threat Scenarios in Industrial OT/IIoT Systems

On the basis of the reference analysis of the IT/OT architecture and the analysis of cyber threat scenarios, a set of representative scenarios of the impact of cyberattacks on industrial automation systems operating in critical infrastructure environments has been identified.

Scenario 1: Delay or falsification of process data. This scenario involves interfering with data from measurement systems that monitor critical process parameters. Transmission delays or the generation of incorrect values cause supervisory systems and operators to make decisions based on a misrepresentation of the situation, which can lead to a delayed response to dangerous conditions.

- Impact classification: Degrade/Disrupt.

Scenario 2: Control logic integrity violation. In this scenario, the control algorithms in the automation systems are modified, resulting in an inappropriate response of the actuators. An example is the further increase in process parameters despite exceeding alarm thresholds or the deactivation of safety mechanisms.

- Impact classification: Destroy/Disrupt.

Scenario 3: Loss of availability of operational surveillance systems. The scenario involves the temporary or permanent immobilization of visualization and operational surveillance systems, which forces personnel to work in emergency mode, based on limited information. In dynamic industrial processes, this significantly increases the risk of decision-making errors.

- Impact classification: Deny/Disrupt.

Scenario 4: Indirect impact through supporting systems. Disruption of support systems, such as reporting, planning or data archiving systems, leads to disorganization of decision-making processes and indirectly affects the operational safety of the installation.

- Classification of effects: Degrade.

The identified scenarios provide a direct reference point for the analysis of architectural vulnerabilities and attack vectors presented in the following subsections of the results chapter.

4.2. Identified Vulnerabilities in Industrial IT/OT Architectures

The analysis showed that the cyber threat scenarios described above are possible due to the presence of a number of technical, architectural and organizational vulnerabilities. One of the key factors contributing to the occurrence of these vulnerabilities is the phenomenon of technological debt, commonly observed in large organizations operating extensive ICT infrastructure. Regularly updating and upgrading all infrastructure elements is a complex and costly process, and production environments often have outdated and unsupported systems, posing a significant security risk to the entire infrastructure.

The second significant vulnerability is the presence of external network connections implemented through separate tunnels, used, for m.in example, to provide technical support services or integration with external partners’ systems. Each such connection increases the attack surface and can be a potential route for unauthorized access to the internal network.

Another group of vulnerabilities results from operational practices related to enabling remote access to industrial automation systems. These solutions are often implemented to increase work efficiency, improve supervision or reduce operating costs. Taking over the account of a user with privileged access, in particular in the case of the use of private or less secure workstations, makes it possible to use these rights to carry out destructive activities in the industrial automation network.

The last of the key vulnerabilities identified in the analysis is the use of the so-called flat network architecture, which consists of connecting multiple subnets within a single trust relationship. In such solutions, breaking the security of any element of the network, including systems operating in the office network, can lead to the compromise of the entire infrastructure, including industrial automation systems.

Figure 2 shows an example of an internal network architecture that, despite its apparent orderly structure, is characterized by a number of vulnerabilities resulting from design errors and operational negligence. Analysis of this architecture has shown that even minor irregularities in the configuration of connections and access control mechanisms can enable a sequence of attacks leading to a complete compromise of network security.

Figure 2.

Typical IT/OT network architecture showing internal network, gateways, Internet and trusted partners’ network, source: own study based [1].

The identified architectural vulnerabilities were the basis for distinguishing common attack vectors that can be used by cybercriminals to gain access to industrial automation systems or influence technological processes.

4.3. Identified Attack Vectors

Based on the architecture and vulnerability analysis, six key scenarios for entering the industrial automation network were identified:

- Direct connection of the OT network to the Internet, bypassing standard security mechanisms.

- An incorrectly configured OT network connection to the Internet.

- Infecting workstations of OT operators with access to the Internet.

- Improper segregation of internal networks.

- Transition to the OT network from a previously acquired network of suppliers or external partners.

- Direct infection of OT operators’ workstations.

The identified attack vectors confirm that threats to industrial automation systems do not result only from direct attempts to attack OT infrastructure, but are very often a consequence of compromising systems operating in other network segments.

4.4. Identified Hedging Decisions and Their Consequences

As a result of the analysis, a set of possible decisions regarding the protection of industrial automation infrastructure was indicated. One of the basic solutions is the complete separation of the OT network from other network segments, in the extreme case implemented at the galvanic level. This approach effectively reduces the risk of cyberattacks, but it can be difficult to implement for business reasons.

In situations where full separation is not possible, the possibility of using unidirectional data transmission mechanisms is indicated, allowing remote reading of parameters without the possibility of interfering with the control process. Alternatives are more complex and costly solutions, such as network micro-segmentation, implementation of NDR and IPS systems, as well as continuous monitoring of symptoms of cyberattacks in office networks, which may indirectly affect the OT network.

The analysis also showed the importance of solutions to ensure the continuity of system operation in the event of a failure, including redundancy mechanisms and business continuity restoration plans. The need to identify critical operational moments and realistically assess repair time in order to make rational investment decisions was indicated.

Particular attention was also paid to the risks associated with the possibility of taking control of systems of key importance for process safety. In this context, the need to physically separate security systems such as SIS and to ensure the possibility of manual takeover of control in emergency situations was highlighted.

4.5. The Role of AI Tools as a Result of Analysis

The last important result of the analysis is the identification of potential areas of application of AI-based tools, in particular large language models. It was indicated that these solutions can support the automation of repetitive activities performed by SOC teams, the identification of anomalies in network traffic and the analysis of transmitted process parameters. Attention was also drawn to the growing importance of threats related to the use of AI by attackers, which in the long term may lead to the need to use defensive solutions based on similar technologies.

The experiment allowed to assess the usefulness of large language models as tools supporting the process of initial analysis of cybersecurity incidents in industrial environments using IoT/IIoT solutions and industrial automation systems. The analysis of the results was carried out based on a set of synthetic but realistic incident scenarios, reflecting the typical architectural and operational conditions of critical infrastructure.

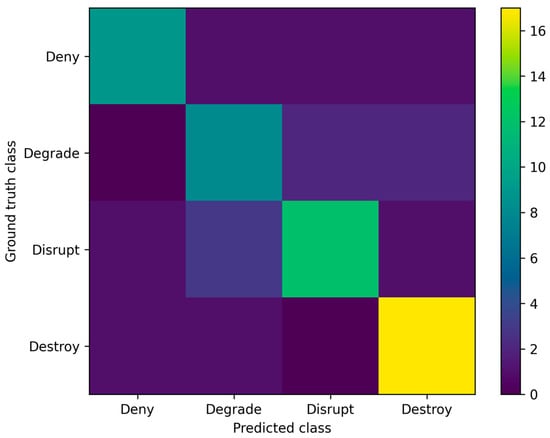

Figure 3 shows the results of the classification of the effects of incidents. It can be observed that the evaluations indicate that the LLM model achieves high compliance with the reference labels, both in terms of accuracy and Macro-F1 measure. A detailed analysis of the error matrix shows that classification errors are mainly concentrated between the Degrade and Disrupt categories. This phenomenon is consistent with the characteristics of IoT/IIoT environments, in which the boundary between gradual degradation of operating parameters and temporary disruption of systems is sometimes ambiguous. At the same time, the absence of systematic errors between the extreme classes (Deny and Destroy) suggests that the model correctly interprets the scale and potential consequences of the analyzed incidents.

Figure 3.

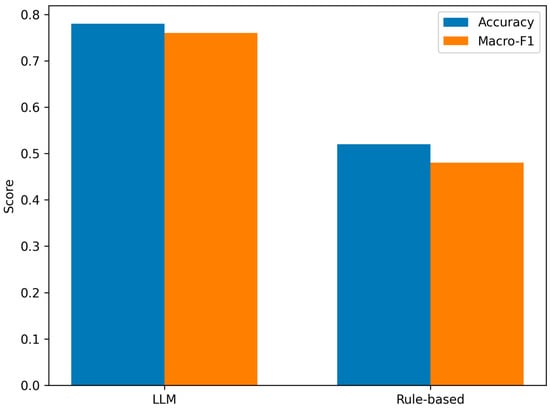

Confusion matrix for LLM-based classification of incident impact categories., source: own study.

A comparison of the results obtained by the LLM with the results of the baseline model based on dictionary rules clearly indicates the advantage of the approach using language models (Figure 4). The baseline model, limited to keyword analysis, does not take into account the architectural context or the relationship between the IT, DMZ, and OT segments, resulting in lower ranking performance. In contrast, an LLM can integrate information from a variety of data sources, including IIoT telemetry and security system logs, resulting in a more accurate recognition of the nature of incidents. Table 1 reports the numerical values of the key performance metrics obtained for both the LLM-based approach and the rule-based baseline.

Figure 4.

Comparison of classification performance between the LLM-based approach and a rule-based baseline, source: own study.

Table 1.

Comparative performance of the LLM-assisted approach and the rule-based baseline.

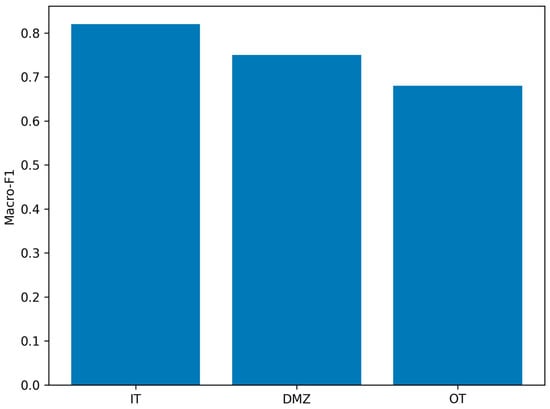

Analysis of the results taking into account network architecture segments indicates a different effectiveness of classification depending on the location of the incident (Figure 5). The best results were obtained for the IT segment, where the availability of diagnostic data and logs is the highest. Slightly lower efficiency in the DMZ confirms its role as an intermediate area, connecting the IT and OT worlds. The lowest values of effectiveness measures were recorded in the OT segment, which can be associated with limited observability of events, restrictive rules for interference with production systems, and the specificity of data generated by industrial automation and IIoT devices. The exact Macro-F1 values obtained for individual network segments are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 5.

LLM classification performance across IT, DMZ, and OT network segments, source: own study.

Table 2.

Macro-F1 score of the LLM-assisted triage across network segments.

The observed performance differences across IT, DMZ, and OT segments, particularly the lower results obtained for OT environments (Figure 4), can be explained by inherent architectural and operational constraints specific to industrial control systems.

OT environments are characterized by limited observability, restricted logging capabilities, and the use of specialized industrial protocols that expose fewer semantic cues compared to IT systems. Telemetry in OT networks is often sparse, highly aggregated, or constrained by real-time and safety requirements, which reduces the contextual richness available for automated analysis. In addition, strict operational constraints limit the deployment of intrusive monitoring mechanisms, resulting in incomplete or delayed visibility into incident progression.

By contrast, IT and DMZ segments typically provide more comprehensive logs, standardized protocols, and higher data availability, enabling more accurate semantic interpretation and classification. Consequently, the reduced performance observed in OT segments reflects not a limitation of the LLM-based approach itself, but rather the structural characteristics of industrial environments in which security analysis must operate under constrained visibility and strict operational boundaries.

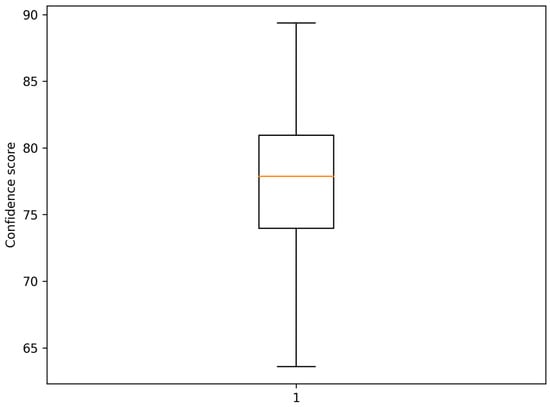

An important element of the analysis was the evaluation of the stability of the model’s response in subsequent experiment runs, which is shown in Figure 6. The small spread of claimed confidence levels and the high percentage of consistent classifications in the three independent triggers indicate that the LLM behaves in a predictable and repeatable manner. Table 3 provides a quantitative summary of the distribution of confidence scores across repeated runs.

Figure 6.

Stability of LLM confidence scores across multiple runs, source: own study.

Table 3.

Distribution of LLM confidence scores across repeated runs.

This feature is crucial in the context of decision-making applications, where inconsistency in responses could lead to erroneous or contradictory operational recommendations.

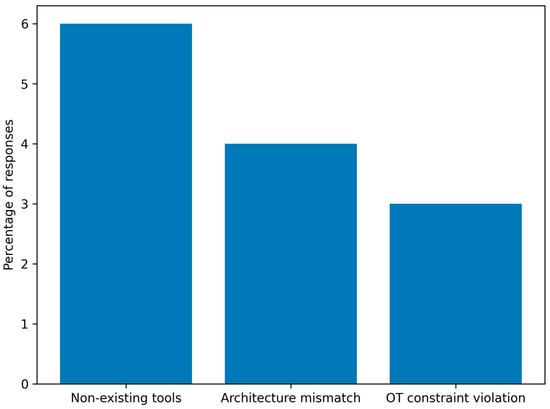

Figure 7 shows a graph on LLM hallucinations. Analysis of the hallucination rate shows that most errors of this type are related to references to non-existent tools or infrastructure elements that were not included in the input. Less commonly, violations of operational constraints of OT environments or errors in the interpretation of network architecture were observed. These results confirm that with a properly formulated experimental protocol and explicit input limitations, the risk of hallucinations can be significantly reduced, although it cannot be completely eliminated. A detailed breakdown of hallucination categories and their relative frequency is reported in Table 4.

Figure 7.

Hallucination rate detected in LLM-generated responses, source: own study.

Table 4.

Distribution of hallucination types in LLM responses.

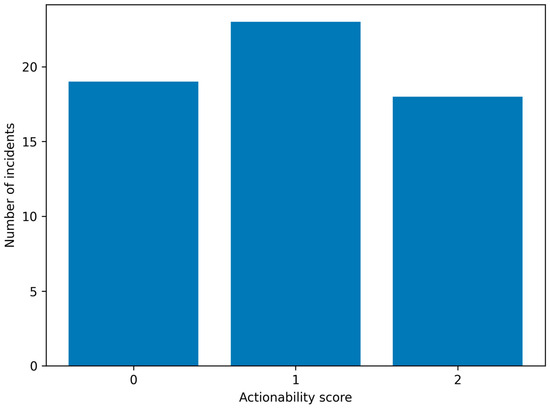

An expert assessment of the usefulness of the recommended reaction actions indicates that a significant part of the proposals generated by the LLM are of a practical nature and can provide real support for SOC analysts (Figure 8). Most often, recommendations on initial isolation of network segments, verification of anomaly sources, and analysis of available logs and telemetry were highly useful. At the same time, it was emphasized that these recommendations should be treated as support for the decision-making process, and not as autonomous implementing instructions. Table 5 summarizes the distribution of actionability scores assigned by domain experts.

Figure 8.

Distribution of actionability scores for LLM-recommended response measures, source: own study.

Table 5.

Distribution of actionability scores for LLM recommendations.

The analysis confirms that large language models can effectively support selected stages of triage of cybersecurity incidents in IoT/IIoT and OT environments, provided that their role is strictly limited to analytical and decision-making functions and expert supervision is maintained.

5. Discussion

The research confirms that large language models can be a valuable tool supporting the analysis of cybersecurity incidents in industrial environments using IoT/IIoT systems and industrial automation. The results indicate that LLMs are able to integrate heterogeneous information from different layers of IT/OT architecture, which allows for a more contextual interpretation of events compared to classic rule- or keyword-based methods.

From the point of view of risk management, the key result is the ability to link the classification of incidents (deny, degrade, disrupt, destroy) with the potential effects on the continuity of technological processes, human safety and the environment. This type of mapping is an important element of qualitative risk analysis, allowing for better estimation of the consequences of incidents and their prioritization in decision-making processes. The results suggest that an LLM can support analysts in identifying areas of higher risk, especially in environments characterized by high architectural complexity and limited observability.

A particularly important result is the observed ability of the model to correctly classify the effects of incidents in the categories of deny, degrade, disrupt and destruction. Error analysis shows that errors are mainly concentrated between classes with similar operational consequences, reflecting the actual ambiguity that occurs in IoT/IIoT environments. From a risk analysis perspective, this means that the boundary between an acceptable level of degradation and an unacceptable disruption to process continuity may require additional expert assessment, which the LLM can support but not replace.

A comparison with the rule-based baseline model clearly shows the advantage of the language-based approach. In the context of risk management, this means that classical methods can lead to underestimation of risk in complex multi-segment scenarios, where single technical symptoms do not reflect the full picture of the threat. An LLM, through context analysis, can support a more holistic risk assessment, taking into account both technical and operational aspects.

The stability of the model’s response is of direct importance for risk analysis processes. The repeatability of the classification and the small dispersion of confidence levels are conducive to the use of LLMs as a tool to support the cyclical risk reviews and updating of risk registers. At the same time, the results of the hallucination analysis confirm the need to be careful in automating decision-making processes. The risk of generating unsubstantiated information must be treated as an additional risk factor, which in itself should be subject to assessment and control.

The use of synthetic incident scenarios and the lack of direct quantitative validation of risk remain a limitation of the presented studies. Nevertheless, the proposed approach allows for qualitative support for key steps of risk analysis, such as the identification of risks, the initial assessment of their impacts and the identification of areas requiring in-depth analysis.

The presented framework highlights a fundamental distinction between LLM-based triage and prior AI/ML approaches applied to IIoT security. Whereas deep learning and hybrid systems typically rely on fixed feature spaces, predefined labels, or manually engineered rules, the proposed approach leverages the ability of LLMs to reason over incomplete, heterogeneous, and semantically rich inputs. This enables the integration of technical signals with architectural and organizational context, which is often critical in industrial environments but difficult to encode in traditional models.

Importantly, the proposed framework does not aim to replace existing detection or monitoring systems. Instead, it introduces a higher-level reasoning layer that operates downstream of detection, supporting analysts in interpreting incidents, assessing impact, and prioritizing responses under operational constraints. This shift from detection-oriented modeling to decision-oriented reasoning constitutes the main conceptual contribution of this work and suggests a new role for generative AI in the security architecture of industrial IoT systems.

6. Conclusions

The conducted analyses and the designed research experiment allow for confirmation of the research hypothesis, according to which large language models can effectively support the initial analysis (triage) of cybersecurity incidents in industrial IT/OT and IIoT environments. The results demonstrate that LLM-based analysis improves the quality of incident classification and the usefulness of recommended actions when compared to simple rule-based approaches, while maintaining an acceptable level of risk associated with model hallucinations.

The article provides a comprehensive qualitative analysis of cyber threats affecting critical infrastructure, with particular emphasis on industrial architectures integrating information systems, industrial automation, and IIoT devices. Based on an extensive review of the literature, standards, regulations, and commonly deployed architectural solutions, a reference IT/OT model was developed, which was used to identify realistic cyber threat scenarios, architectural vulnerabilities, and attack vectors. The classification of incident effects into deny, degrade, disrupt, and destroy categories enabled a direct linkage between cyber events and their potential impact on process continuity, human safety, and environmental protection.

A key component of the study was the design and execution of an experiment employing a large language model as a decision-support tool for cybersecurity incident triage. The experiment relied on a synthetic yet realistic set of SOC tickets reflecting typical operational and architectural conditions of IIoT/OT environments. The obtained results indicate that the LLM is capable of integrating heterogeneous information derived from system logs, IIoT telemetry, and architectural context, leading to higher effectiveness in incident classification compared to a dictionary-based baseline model.

The analysis further revealed that LLM performance varies across architectural segments, achieving the highest effectiveness in the IT layer, with a gradual decrease in DMZ and OT zones. This behavior reflects inherent limitations in event observability within industrial automation systems and strict constraints on interference in production environments. At the same time, the high stability of model responses across repeated experimental runs suggests that LLMs can support cyclical processes of security event review and risk analysis.

From a risk management perspective, an important outcome of this work is the demonstrated potential of large language models to qualitatively support threat identification, impact assessment, and prioritization of security actions in critical infrastructure environments. LLMs are not intended to replace formal risk analysis methods or expert judgment, but rather to support decision-making in the face of increasing IT/OT complexity and growing volumes of security events.

At the same time, the study confirms that the use of LLMs entails the risk of generating unsupported or OT-incompatible information. This risk is explicitly treated as an integral element of cybersecurity risk management and mitigated through control mechanisms, including strict task scoping, enforced reliance on input data, structured response formats, and expert supervision.

Overall, the presented approach demonstrates that large language models can be responsibly integrated into cybersecurity systems for industrial IIoT/OT environments as decision-support tools, while preserving the central role of human operators. Future research directions are explicitly identified, including validation using real operational data, deeper integration with formal risk assessment methodologies, and evaluation of regulatory impacts—such as the NIS2 Directive—on practical deployment in critical infrastructure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and J.S.; methodology, A.M. and J.S.; software, A.M.; validation, A.M. and J.S.; formal analysis, A.M. and J.S.; investigation, A.M. and J.S.; resources, A.M. and J.S.; data curation, A.M. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and J.S.; visualization, A.M. and J.S.; supervision, A.M.; project administration, A.M. and J.S.; funding acquisition, A.M. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Statutory Research 06/010/BK_25/0064.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Syta, J. Zarządzanie Cyberbezpieczeństwem. Pracownicy. Procesy. Technologie; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Miśkiewicz, K.; Wojaczek, A. Telekomunikacja w Górnictwie II: Wybrane Zagadnienia Teletransmisyjne; Wydawnictwo Katedry Elektrotechniki i Automatyki Przemysłowej, Politechnika Śląska: Gliwice, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC 62443-1:2024; Security for Industrial Automation and Control Systems—Part 1: Terminology, Concepts and Models. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- European Parliament and Council. Directive (EU) 2022/2555 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union (NIS2 Directive). Off. J. Eur. Union 2022, L 333, 80–152. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2555/oj/eng (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Chvednko, S.; Rocha, F.; Barbosa de Araujo, D. Anomaly Detection in Industrial Machinery Using IoT Devices and Machine Learning: A Systematic Mapping. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 140834–140858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elouardi, S.; Motii, A.; Jouhari, M.; Amadou, A.N.H.; Hedabou, M. A survey on Hybrid-CNN and LLMs for intrusion detection systems: Recent IoT datasets. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 180009–180033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.; Dawar, O.; Demir, S. When IoT Meets LLMs: Applications and Challenges. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2024, 8, 204. [Google Scholar]

- Diaf, A.; Korba, A.A.; Karabadji, N.E.; Ghamri-Doudane, Y. Beyond Detection: Leveraging Large Language Models for Cyber Attack Prediction in IoT Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 20th International Conference on Distributed Computing in Smart Systems and the Internet of Things (DCOSS-IoT), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 29 April –1 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Khatiwada, K.; Hopper, J.; Cheatham, J.; Joshi, A.; Baidya, S. Large Language Models in the IoT Ecosystem—A Survey on Security Challenges and Applications. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.17586. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Li, C.; Wang, H. Towards General Industrial Intelligence: A Survey of Continual Learning in Industrial IoT. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 45678–45695. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.; Chen, P. A LLM-based agent for the automatic generation and generalization of IDS rules. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), Sanya, China, 17–21 December 2024; pp. 1875–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. FCLLM-DT: Empowering Federated Continual Learning with Large Language Models for Digital Twin-Based Industrial IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 6070–6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.; Sutton, J. An Adaptive End-to-End IoT Security Framework Using Explainable AI and LLMs. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 10th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 10–13 November 2024; pp. 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, A.; Alhazmi, A.; Alqarni, F. BARTRPred: Empowering IoT Security with LLM-Driven Cyber Threat Prediction. In Proceedings of the Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8–12 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, E.; Javed, M.; Saeed, Y. Modeling Industrial IoT Security Using Ontologies: A Systematic Review. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2025, 6, 2792–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.; Gupta, R.; Kaur, K.; Ahmad, F. Enhancing Cybersecurity in Critical Infrastructure with LLM-Assisted Explainable IoT Systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), New Delhi, India, 13–15 March 2019; pp. 801–805. [Google Scholar]

- Shameli-Sendi, A.; Cherdantseva, Y.; Burnap, P.; Jones, K. A Survey of Cyber Security Risk Assessment Methods for SCADA Systems. Comput. Secur. 2016, 56, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oranekwu, I.; Elluri, L.; Batra, G. Automated Knowledge Framework for IoT Cybersecurity Compliance. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Washington, DC, USA, 15–18 December 2024; pp. 6336–6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertino, E.; Islam, N. Botnets and Internet of Things Security. Computer 2017, 50, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouffer, K.; Lightman, S.; Pillitteri, V.; Abrams, M.; Hahn, A. Guide to Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Security; NIST Special Publication 800-82; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamare, D.; Zolanvari, M.; Erbad, A.; Jain, R.; Khan, K.; Meskin, N. Cybersecurity for industrial control systems: A survey. Comput. Secur. 2020, 89, 101677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) 2024/2847 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2024 on horizontal cybersecurity requirements for products with digital elements and amending Regulations (EU) No 168/2013 and (EU) No 2019/1020 and Directive (EU) 2020/1828 (Cyber Resilience Act). Off. J. Eur. Union 2024, L 2847, 1–29. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/2847/oj (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA). Threat Landscape for Industrial Control Systems; ENISA: Athens, Greece, 2024; Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/enisa-threat-landscape-2024 (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) 2019/881 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on ENISA (the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity) and on information and communications technology cybersecurity certification, repealing Regulation (EU) No 526/2013 (Cybersecurity Act). Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, L 151, 15–69. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/881/oj (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). Cross-Sector Industrial Control Systems Top 10 Cybersecurity Incidents; CISA: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.cisa.gov/ics (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Miśkiewicz, K.; Wojaczek, A. Telekomunikacja w Górnictwie. Systemy Łączności Telefonicznej, Alarmowej i Głośnomówiącej; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2018; ISBN 978-83-7880-599-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zetter, K. Countdown to Zero Day: Stuxnet and the Launch of the World’s First Digital Weapon; Crown Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Winterford, B. Hackers Attempt to Poison American Town’s Water Supply. Risky Business Bulletin February 2021. Available online: https://risky.biz/newsletter43/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC). Notifiable Data Breaches Report: January–June 2024. Available online: https://www.oaic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/242050/Notifiable-data-breaches-report-January-to-June-2024.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Manowska, A.; Syta, J. Przegląd cyberzagrożeń w środowiskach przemysłowych z uwzględnieniem rosnącej roli systemów OT. In Proceedings of the 6. Polski Kongres Górniczy, Lublin, Poland, 24–26 September 2025; Dyczko, A., Woźniak, G., Klojzy-Karczmarczyk, B., Hutniczak, A., Galica, D., Kulpa, J., Eds.; Instytut Gospodarki Surowcami Mineralnymi i Energią Polskiej Akademii Nauk: Kraków, Poland, 2025; pp. 28–29. Available online: https://pkg.edu.pl/pkg6-referaty (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Institute of Public Affairs. The Politics of a Tragedy: The Gretley Mine Disaster; IPA: Melbourne, Australia, 1996; Available online: https://ipa.org.au/archived-program/the-politics-of-a-tragedy-the-gretley-mine-disaster-and-nsw-ohs (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Manowska, A.; Boros, M.; Hassan, M.W.; Bluszcz, A.; Tobór-Osadnik, K. A modern approach to securing critical infrastructure in energy transmission networks: Integration of cryptographic mechanisms and biometric data. Electronics 2024, 13, 2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manowska, A.; Boros, M.; Bluszcz, A.; Tobór-Osadnik, K. The use of the Command Line Interface in the Verification and Management of the Security of IT Systems and the Analysis of the Potential of Integrating Biometric Data in Cryptographic Mechanisms. Zeszyty Naukowe Politechniki Śląskiej. Organizacja i Zarządzanie 2024, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, W.; Prince, D.; Hutchison, D.; Disso, J.-P.; Jones, K. A survey of cyber security management in industrial control systems. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2015, 9, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.; Rowe, D. A survey of SCADA and critical infrastructure incidents. In Proceedings of the 1st Annual Conference on Research in Information Technology; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Krotofil, M.; Larsen, J. Rocking the Pocket Book: Hacking Chemical Plants for Competition and Extortion. 2015. Available online: https://blackhat.com/docs/us-15/materials/us-15-Krotofil-Rocking-The-Pocket-Book-Hacking-Chemical-Plant-For-Competition-And-Extortion.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- World Economic Forum. Global Cybersecurity Outlook 2025; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-cybersecurity-outlook-2025/ (accessed on 5 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.