Abstract

The article presents the analytic method for real-time detection of the stationary state of a vehicle based on information retrieved from 6 DoF IMU sensor. Reliable detection of stillness is essential for the application of resetting the inertial sensor’s output bias, called Zero Velocity Update method. It is obvious that the signal from the strapped on inertial sensor differs while the vehicle is stationary or moving. Effort was then made to find a computational method that would automatically discriminate between both states with possibly small impact on the vehicle embedded controller. An algorithmic step-by-step method for building, optimizing, and implementing a diagnostic system that detects the vehicle’s stationary state was developed. The proposed method adopts the “Mahalanobis Distance” quantity widely used in industrial quality assurance systems. The method transforms (fuses) information from multiple diagnostic variables (including linear accelerations and angular velocities) into one scalar variable, expressing the degree of deviation in the robot’s current state from the stationary state. Then, the method was implemented and tested in the dead reckoning navigation system of an autonomous wheeled mobile robot. The method correctly classified nearly 93% of all stationary states of the robot and obtained only less than 0.3% wrong states.

1. Introduction

The share of autonomous vehicles in the market continues to grow. One of the fundamental challenges in this area is the accurate measurement of vehicle position [1,2,3], with vehicle orientation (rotation) being particularly difficult to determine. Measurement systems are continuously improved by various researchers [4,5,6,7,8]. Another issue directly related to the positioning of autonomous vehicles is safety [9,10]. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct comprehensive risk analyses associated with the operation of such vehicles [11,12,13].

Incremental position and orientation tracking of objects in the 3D space is commonly used for navigation purposes, particularly in autonomous vehicles. Some of these methods rely on information from linear acceleration sensors and angular position or velocity sensors attached to the vehicle frame. These methods are referred to as inertial navigation [14,15].

A measurement device that integrates accelerometers and gyroscopes is generally referred to as an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU). Thanks to microelectromechanical system (MEMS) technology, it has been possible to miniaturize and integrate inertial measurement systems, along with control and sensing electronics, into a single integrated circuit [16,17,18]. Sensors built this way offer numerous advantages, including very small size and weight, low power consumption, resistance to environmental factors, high reliability and durability, maintenance-free operation, high dynamic response, and low cost.

The effect of bias drift is one of the most important factors affecting the accuracy of measurements made with microelectromechanical (MEMS) gyroscopes. The bias directly modulates the output signal of a gyroscope by adding a (pseudo-) stochastic value to the signal proportional to the rotational speed of the body. Using an MEMS gyroscope to measure the incremental changes in body attitude is even harder as the consecutive readings must be summed up (integrated) and the effect of modulation is accumulated. The value of bias depends on the design of the sensor, sensor temperature, time, and the factors that are assumed to be of random character (like spontaneous changes in electronic elements) that are often modeled as a random walk [19].

Bias drift is a well-known characteristic of differential sensors like (micro-) mechanical gyroscopes or accelerometers used for incremental position tracking (dead reckoning). Since the sensor readings must be integrated over time to obtain the position estimate, following bias changes is vital for the accuracy of incremental navigation. The problem of gyroscope bias drift estimation is the fundamental issue widely discussed in the literature (including [4,20,21,22]) and also in the works of the authors [23].

Known methods of bias compensation include stabilization of sensor environment (sensor temperature, vibration, power supply, etc.), bias models (limited to slow changing factors, or (near-)complete models), application of digital or analog filters (low pass, Kalman), multiplication of sensors (sensor arrays), sensor rotation procedures, and periodic reset (calibration) relying on additional sensor data (magnetometer, accelerometer), or information on system state (sensor reset procedures).

One of the methods of resetting the inertial sensor is Zero Velocity Update (ZUPT [24,25]), which is based on the fact that the output of a stationary gyroscope equals its bias. This method proved to be effective for auxiliary sensors used in the environment, where regular calibration stops could be executed.

The typical movement pattern of industrial autonomous vehicles, that serve local transport tasks (like production line tending or providing transport services in storage areas), includes frequent stops for loading and unloading operations, waiting (process synchronization), or avoiding collisions (either with people or other vehicles) [26,27]. For such work conditions, ZUPT is an effective and cost-efficient way of sensor calibration.

The reliability of ZUPT is determined by the accuracy of the detection of the stationary (non-moving) state of the sensor. The detection can be based on the following: the readings of another sensor like accelerometer in pedestrian foot-mounted systems [28]; observation of the environment with on-board sensors (e.g., laser scanners or 3D cameras); observation of control signals and the forces acting on the vehicle itself (e.g., with the inertial sensor used for navigation).

Periodic bias updates in zero velocity conditions could extend the operating range of the vehicles that use inertial navigation (like AGV and AMR [23]). This could make favorable conditions for practical application data series [29] or the output of a system model [30]. But the method is effective only if the stationary state of the vehicle can be properly detected.

This paper discusses the problem of detecting zero-velocity states during the movement of a vehicle and using this information to update bias of the IMU sensor. The proposed method adopts the Mahalanobis–Taguchi strategy [31,32] for automatic discriminate movement or stationary states of a sensor attached to a vehicle chassis.

2. Methods

The Mahalanobis Distance (MD), introduced in [33], is a generalized measure expressing the deviation in a multivariate sample of measurements (vector) X from the vector of mean values mi of variables for the corresponding elements of this sample in a given population. The MD value is used to estimate the rate of similarity of vector X with a multivariate set of observations considered as a reference. The reference data set is characterized by the following:

- -

- Vector of mean values mi;

- -

- Standard deviations si;

- -

- Correlation matrix C expressing the interdependencies between variables.

These three quantities/statistics characterize the population and are used to calculate the MD value.

The MD method was then adopted by Taguchi [31,32] to define a procedure for evaluating the quality of industrial processes known as the Mahalanobis–Taguchi system or MTS. Despite the discussion over several application issues [34,35], the procedure proposed by Taguchi was successfully applied to cutting tool monitoring [36], evaluation of vehicle performance [37], fault detection in MEMS [38], cooling systems and induction motors [39], road surfaces [39,40], and the production process of tablet PCs [41]. MTS was also successfully applied in robotics, for example, in robot localization inside sewage pipes [42], controlling an assistive robot [43], vision-based navigation [44], object tracking [45], human activity monitoring [46], and in outlier detection [47,48].

Since MD provides a convenient measure of how much a set of data differs from a predefined model population (or expected value), it was used in navigation systems to detect abnormal measurements and improve measurement accuracy in noisy environments [47,49,50,51].

The Mahalanobis distance is a scalar quantity defined on an arbitrary numerical scale and allows the current state of an object to be classified as one of two distinct states, e.g., normal or abnormal.

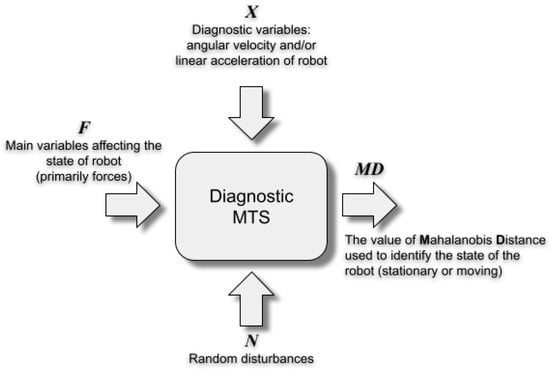

The diagram in Figure 1 shows the scheme of the diagnostic MTS dedicated to detecting the stationary state of an object (mobile robot). Vector X represents a set of easily measurable variables (Cartesian components of angular velocity and linear acceleration vectors of robot’s chassis), N symbolizes random disturbances, and F denotes a set of factors (forces) that act on the object, setting it in motion, consequently changing its state from normal (stationary state) to abnormal (moving state). The symbol MD denotes a scalar value expressed on a dedicated numerical scale used to identify the object’s state. The dimensionless MD value is calculated solely based on the current values of the X variables and quantitatively expresses how much the current object state differs from the normal (stationary) state.

Figure 1.

Causal and output variables of the diagnostic Mahalanobis–Taguchi System (MTS) for detecting the stationary state of a mobile robot.

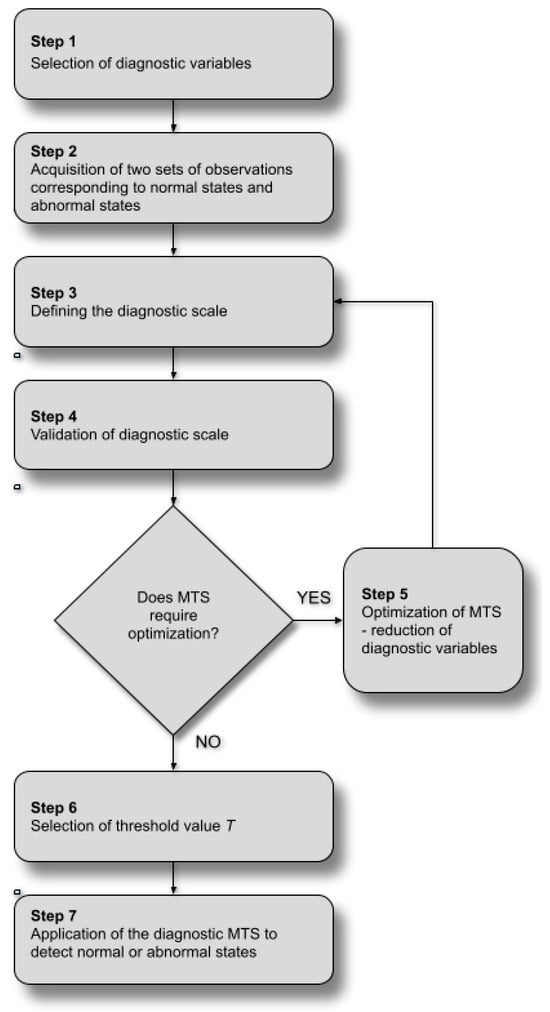

The development of a diagnostic MTS is a step-by-step procedure, graphically presented in Figure 2. The individual steps in developing an MTS are explained below.

Figure 2.

Algorithm of developing the diagnostic MTS.

Step 1. Selection of diagnostic variables X describing the object’s state.

Step 2. Acquisition of two sets of observations corresponding to normal states (referred to in the literature as a healthy data set [30] and abnormal states of the object.

Step 3. Defining the MTS diagnostic scale based on the MD. This step of the procedure uses only the set of observations related to the normal state:

- Calculation of statistics: mean values mi, standard deviations si of measurements of Xi, where i denotes variable index, i = 1, …, k

- Standardization of variables, i.e., transformation of the Xi variables into standardized Zi variables. Equation (1):

- Estimation of the elements of the inverse covariance matrix C−1 of the X variables;

- Calculation of the MD value for each observation from the normal data set. Equation (2):

- Select zero value and the unit distance for a diagnostic numerical scale, where an MD value of zero refers to the normal conditions of the object and indicates the origin of the scale, while an MD of one indicates the average deviation of observation X from the normal state.

Step 4. Validation of the MTS diagnostic scale. Use the inverse covariance matrix C−1. Mean values mi and standard deviations si is determined in step 3 to estimate the set of MD values corresponding to abnormal observations. The diagnostic scale of the MTS is considered correct when the calculated set of MD values are high (in other words: values of MD for abnormal state are disjoint from the set of MDs calculated for normal observations).

Step 5. Optimization of the diagnostic MTS. Use an orthogonal array (a fraction of a two-value experimental design) [52] and the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) to reduce the number of variables used to calculate the MD. This step aims to improve the MTS to identify abnormal object states. A useful set of variables is selected based on the analysis of S/N gain ηq Equation (3). This optimization is based on measurements solely from the set of abnormal observations.

The orthogonal array contains contractual values representing the states: one (the presence of a variable in the set of diagnostic variables) or zero (its absence). The table’s columns are associated with individual MTS diagnostic variables and the rows with combinations of states of these variables. The structure of the orthogonal table and the ηq coefficients calculated from it allow for the evaluation of the contribution of a given variable to the overall value of the MD. According to Formula (3), the distance MDi = Di2 is calculated for all abnormal observations for each table row, taking into account the contractual states, and then their inverse values are summed. For a given table row, the MD is calculated only for variables that are assigned the value one. Then the calculated ηq value is assigned to the q-th row of the table.

In turn, two average values of the ηq are calculated for each column. One of these is calculated based on the summation of ηq corresponding to states zero, and the other one, corresponding to states one. The difference in these averages expresses the S/N gain. A negative S/N gain value is a premise for excluding a variable from the set of useful variables.

Step 6. Selection of a threshold value T of MD. Calculated MD values greater than or equal to T will indicate abnormal observations, while lower values will indicate normal observations. The T value can be chosen arbitrarily. However, in the discussed application, the threshold value T was determined based on the empirical distribution of MD values for normal observations, so that 99% of them fall below T.

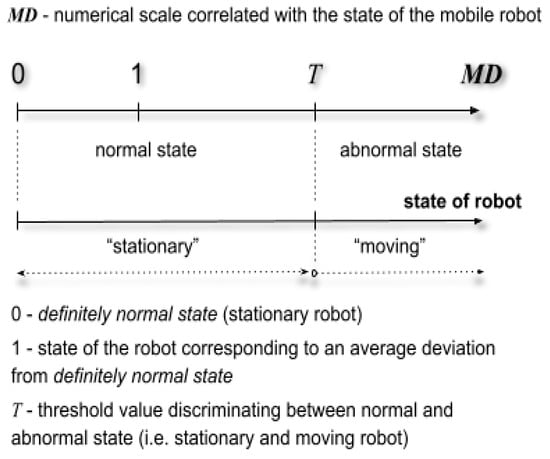

Step 7. Application of the diagnostic MTS to detect abnormal states. Calculation of the MD for the current observation based on the selected set of standardized variables Z (step 3). Comparison of the MD of the current observation with the threshold T and classification of the observations into a set of normal (MD < T) or abnormal (MD >= T) observations. Figure 3 shows the MD scale of the diagnostic MTS with zero value and the unit distance. The threshold T defines the boundary between the object states treated as normal or abnormal (e.g., stationary or moving).

Figure 3.

Numerical scale of diagnostic MTS based on Mahalanobis distance (MD).

The procedure described was used to build a diagnostic MTS for detecting the stationary state of a wheeled mobile robot.

3. Measurements and Results

3.1. Measurements

The data used to build the MTS and its further validation was recorded during the experiment documented in [53], where a mobile robot was replaying a simple time-based sequence of movements. Some data was also collected during the later experiments, where a robot was following a predefined path, using odometry and gyroscope for navigation (dead reckoning). During the test runs, the robot was programmed to move along straight lines and make in-place turns (around its own central axis). Due to the mechanical inaccuracies, the actual path of the robot differed slightly from the programmed one. This issue of path deviation was acknowledged in [53], where it was concluded that such discrepancies have a negligible impact on the detection of stationary and moving states.

In all cases, the moments when the robot was not moving were known beforehand. The purpose of the experiment was to evaluate the accuracy of the proposed zero-velocity detection method that uses diagnostic MTS.

In all experiments, the readings of angular velocities (ωx, ωy, ωz) and linear accelerations (aX, aY, aZ) were simultaneously recorded from the LSM6DS33 chip (6 DoF IMU) [54] mounted on top of the robot, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

IMU chip mounted on the mobile robot used during the experiment.

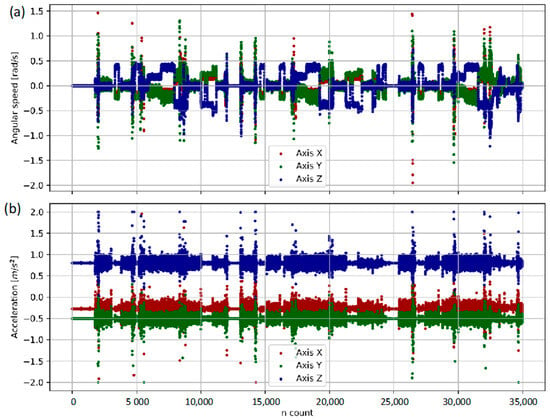

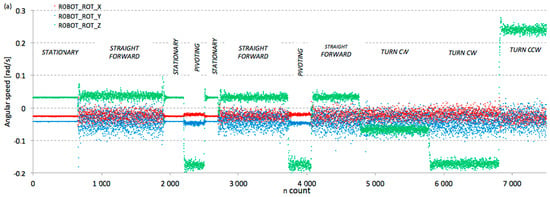

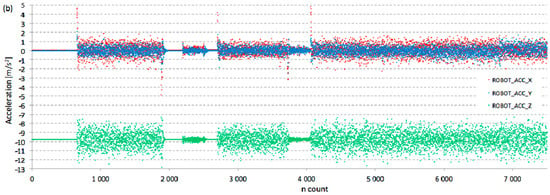

The sensor sampling rate was 100 Hz. The sensor was mounted in such a way that none of its measuring axes was vertical, so the effect of the rotation on the floor (around the world vertical axis) could be seen in at least two gyroscope axes, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Raw data readings from IMU during mobile robot run: (a) angular speed around sensor’s axes; (b) acceleration along sensor’s axes.

3.2. Selection of Diagnostic Variables of MTS (Step 1)

The proposed method of detecting the stationary state was intended to be directly implemented to reduce the error in estimating the position and azimuth of a mobile robot using an incremental method based on an IMU sensor (ZUPT method [24,25]). Hence, the natural choice of input variables for the diagnostic MTS was the readings of angular velocity components (ωx, ωy, ωz) and the linear acceleration components (aX, aY, aZ) from the IMU chip.

3.3. Acquisition of Observations for a Stationary Robot and for a Moving Robot (Step 2)

Data was collected during 20 test runs of the robot described in [53]. In each run, the robot was repeatedly alternated in one of two states: stationary state (intentionally stopped) or moving state (automatically driven by path following algorithm). In the context of the proposed diagnostic MTS, the first state corresponds to the normal state, while the second to the abnormal state. Figure 5 presents example raw IMU sensor data recorded during the robot run.

3.4. Defining the MTS Diagnostic Scale (Step 3)

The robot was held stationary for at least 10 s at the beginning of each of the 20 test runs. Only the data collected during this time were used to define the MTS diagnostic scale based on the MD. The number of observations, in the initial normal state, used in each test run was approximately 1000. The remaining measurements were later treated as diagnostic observations used to validate the developed MTS.

It should be noted that a total of 20 MTSs were built independently for each test run of the robot.

According to the assumptions presented in step 3 of the procedure (see Section 2), the mean value mi and standard deviation si were calculated for each of the input variables (ωx, ωy, ωz, aX, aY, aZ), and the elements of the inverse covariance matrix C-1 were computed. Only the measurement values corresponding to the robot’s initial stationary state were considered in these calculations. The calculated mi, si, and C−1 statistics formed the basis for the construction of each of the 20 MTSs. Next, using Formula (1), the observations were standardized to calculate the Mahalanobis distance MD (2).

In this way, the numerical scales of the MTS were created. The value zero on the MD scale corresponds to the definitely stationary state of the robot, and the unit distance MD = 1 indicates the average deviation of the observations from this state caused by random disturbances (Figure 3).

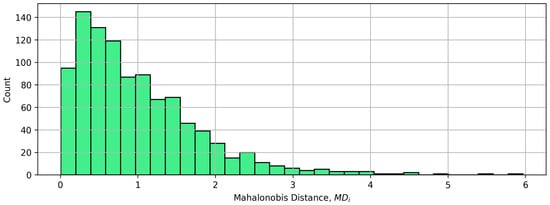

Figure 6 shows a histogram of MD for the initial stationary state of the robot during one of the test runs.

Figure 6.

Histogram of distances MDi calculated for initial stationary state of the robot.

3.5. Validation of the MTS’s Diagnostic Scale (Step 4)

Using the statistics calculated in Section 3.4 (mi, si, and C−1), MDs (2) corresponding to the remaining measurements (ωx, ωy, ωz, aX, aY, aZ) were calculated for each of the 20 test data sets. These measurements were treated as diagnostic observations, used to verify the MD scales of each of the 20 MTSs. For each test data series, it was found that the MDs calculated for abnormal states (i.e., moving robot) were relatively high (>>1) and were disjoint from the set of MDs calculated for normal states (stationary robot). This verified the correctness of the MTS scales.

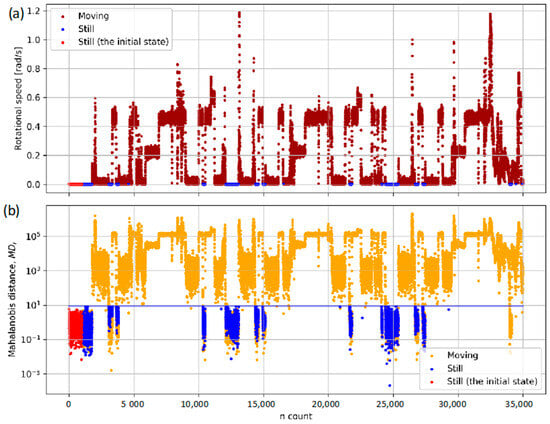

Figure 7 presents the results of MD calculations for observations from the initial section of the selected run (data recorded in the initial stationary state are highlighted).

Figure 7.

Mahalanobis distance values (a) and the resulting classification of stationary condition (b) during the test run for the input data set of 4 DoF (ωx, ωy, ωz, aZ). Points classified as a stationary/still robot are shown in blue. The blue line represents the threshold value. Data points included in the initial stationary set are marked in red color.

3.6. Optimization of the MTS (Step 5)

When designing MTSs, it is assumed that each of the pre-selected diagnostic variables (see step 1) contributes significantly to the calculated MD (2). The decision on the initial classification of each variable is arbitrary and not always appropriate. Therefore, the selection of diagnostic variables should be verified. Eliminating variables that contribute little or nothing to the MD value positively impacts the performance of the MTS by reducing the number of calculations and increasing the ability to distinguish between normal and abnormal states.

The experimental technique proposed in [32] was intended for verification and possible reduction in the number of variables of MTS. The technique is based on orthogonal arrays and signal-to-noise ratio calculations ηq (3). Orthogonal arrays are used to organize the MTS test variants (array rows) and to calculate the ratio ηq caused by the absence/presence of a variable in the system (array columns). The calculations used in this technique are presented in step 5 of the developed method (see Section 2 and Figure 2).

Each of the 20 initially constructed MTSs was subjected to the optimization procedure, and the overall results are summarized in Table A1. The last row of the table presents the average values of the ηq coefficients. Only observations corresponding to abnormal states were used for the calculations. An average coefficient value less than zero indicates that the initially chosen diagnostic variable should be removed from the MTS.

3.7. Selection of a Threshold Value T of MD (Step 6)

The final step in designing a diagnostic MTS is to determine the threshold value T on the MD diagnostic scale. Observations for which MD values are equal to or greater than T will indicate an abnormal state (moving robot). For each MTS, the threshold value T was found based on the empirical probability distribution (histogram) of MDs calculated only for data in the initial stationary state. The MD value corresponding to the 99-th percentile of the distribution was chosen as the T threshold.

3.8. Application of the Diagnostic MTS to Detect Stationary State of the Mobile Robot (Step 7)

Fully functional MTSs were evaluated for their effectiveness in distinguishing the robot’s stationary and moving states. As previously mentioned, each of the 20 test runs was divided into two parts:

- -

- An initial phase, when the robot was intentionally stopped;

- -

- A phase of traveling along a predetermined path, in which the robot was guided automatically.

Only the observations in the second phase were used to verify the accuracy of the robot’s state identification by the MTSs.

The MD was calculated for each observation and compared to the threshold value T, resulting in the classification of the observation as representing a normal (stationary) or abnormal (moving) state. The result of this classification was compared with the actual robot state. A detailed number of correct and incorrect classifications of the robot states by the MTS in all 20 test runs is presented in Table A2.

Table 1 shows the summarized results of classifications of robot state by the MTSs before optimization (before step 5). Data show that the proposed classification method is very effective in detecting robot movement (only 0.06% of measurements were classified wrong). However, the classification of stationary states was much worse (25% of measurements classified wrong). Therefore, the optimization of the MTSs was necessary (according to step 5 on Figure 2).

Table 1.

Classification results based on data from all 6 DoF of the IMU sensor.

To address the relatively high error rate of non-movement state classification (Table 1), the input data analysis was performed with the orthogonal array as proposed in [42]. Each of the 20 initially constructed MTSs was subjected to an optimization procedure, and the overall computation results are summarized in Table A1. The last row of the table presents the average values of the ηq coefficient gains. The calculations included only the measurement values of the variables associated with abnormal observations. Negative averaged gain values indicate that the initially selected diagnostic variable should be removed from the system. Finally, two diagnostic variables’ linear-acceleration components (aX, aY) were excluded.

Using the diagnostic data from 4 DoF instead of 6 resulted in decreased classification error down to 7.26% when the robot was not moving (Table 2.). However, the detection of movement was slightly less effective than before optimization (99.73% vs. 99.94%) since some points were classified as stationary while the robot was actually moving. The detailed results of the robot state classification by the optimized MTS during an example run are shown in Figure 7.

Table 2.

Classification results based on data from 4 DoF of the IMU sensor (ωx, ωy, ωz, aZ).

4. Discussion

The stationary state detection method described in the manuscript is based on the Mahalanobis distance. This method differs from commonly used single-signal thresholding techniques, such as acceleration variance or angular velocity magnitude criteria [55,56]. Threshold-based detectors are computationally efficient and easy to implement; however, their effectiveness can be sensitive to empirically determined parameters and to changes in motion dynamics or sensor noise characteristics. The MTS presented in this work, based on the Mahalanobis distance, enables the transformation of multiple diagnostic variables into a single scalar measure while explicitly accounting for their mutual correlations via the inverse covariance matrix. The use of multiple variables allows for a more objective separation of stationary states from motion states, particularly in scenarios where individual variables might provide ambiguous state classification.

To demonstrate the validity of this result, an additional data analysis was conducted, taking into account a data set consisting of 106,222 samples, including 32,711 instances of the stillness class (positive class) and 73,511 instances of the moving class (negative class).

The evaluation was performed for two variants of the classifier: opt—an optimized version based on an optimized MTS (reduced number of variables); rot—a version incorporating the magnitude of angular velocity only.

The performance of the classifiers was assessed using the following metrics, namely accuracy, precision, recall, specificity, and F1-score, which were all computed for each classifier using the same test data set.

The classification results obtained for the two analyzed classifiers are as follows:

- opt version: TP = 31,708; FN = 960; FP = 430; TN = 73,046;

- rot version: TP = 31,914; FN = 754; FP = 8111; TN = 65,365;

Where TP—True Positive; FN—False Negative; FP—False Positive; TN—True Negative.

Based on the results obtained, the classification performance metrics were calculated and are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

The classification performance metrics.

The opt version achieves very high classification performance across all key metrics. Particularly noteworthy are the high recall (0.971) (indicating effective detection of the stillness class), the very high precision (0.987) (which corresponds to a low number of false alarms), and the highest F1-score (0.979) (confirming a good balance between sensitivity and precision).

The rot version is characterized by a slightly higher sensitivity (recall = 0.977); however, this improvement comes at the cost of a substantial increase in the number of false positives (FP = 8111). As a result, a significant decrease in precision (0.797), a reduction in specificity (0.890), and a lower F1-score (0.877) are observed.

The analysis of the results indicates that the opt version provides the best compromise between detection effectiveness and prediction stability and is therefore the most suitable for practical applications in which both false alarms and missed detections are costly.

The rot version may be considered in scenarios where maximizing the detectability of the stillness class is the primary objective and an increased number of false positives is acceptable.

Numerous studies are being conducted on machine learning-based ZUPT detection methods [57,58,59]. While these approaches can achieve high detection accuracy, they typically require representative datasets and a training phase. They are often based on black-box methods, which can be difficult to interpret and refine. The proposed method eliminates these limitations by offering a fully deterministic, training-free solution with moderate computational requirements. By utilizing standardized variables, covariance modeling, and a fixed decision threshold, this method is well-suited for real-time implementation in industrial mobile robots characterized by frequent stops and starts.

The idea of zero velocity update (ZUPT [24,30,60]) is to re-calibrate the IMU sensor at any moment when the robot is not moving. Since frequent stops (for loading/unloading, waiting for clearance, etc.) are typical for the movement pattern of industrial mobile robots, zero velocity updates proved to be effective in keeping the orientation error low. But to reduce the error value, an objective detection of the robot’s stationary state is needed.

For the purposes of robot motion control, as well as localization and navigation, a Cartesian coordinate system is defined, associated with the robot’s chassis. The robot used in the experiments had a simple differential drive. For robots with this kinematics, the origin of the coordinate system is typically placed at the midpoint of the segment, connecting the centers of both drive wheels. The positive X-axis of the system is oriented toward the front of the robot, the positive Z-axis is vertically upward, and the positive Y-axis is oriented toward the left drive wheel. This choice of coordinate system naturally follows from the robot’s mobility and allows for an intuitive description and interpretation of the robot’s behavior as a rigid body in a global reference frame (usually related to Earth).

However, as seen in Figure 4, the measurement axes of the IMU sensor do not align with the axes of the robot’s coordinate system. The sensor was intentionally mounted “obliquely” (by rotating it through Euler angles of 15, 35, and 10 degrees) so that the robot’s rotation around its Z axis (around the vertical) affected all three Cartesian components of the sensor’s gyroscope. To analyze and discuss the robot’s behavior in the robot’s coordinate system (its acceleration, vibration, and rotation), it was necessary to transform the measurement results from the IMU sensor into the robot’s Cartesian components. Figure 8 shows the charts of the angular velocity and linear acceleration components in the coordinate system associated with the robot’s chassis during a selected test run, with the various stages of its motion marked. Figure 8a clearly shows non-zero angular velocity components (even in stationary states). These values result from the non-zero offsets of the IMU sensor’s gyroscope.

Figure 8.

Orthogonal components of angular speed (a) and linear acceleration (b) of the mobile robot acquired during test run (direction +X towards the front of the robot, direction +Z vertically upwards, direction +Y towards the left of the robot). The IMU sensor sampling rate was 100 Hz.

In all tests, the robot moved on a clean, even, smooth, and leveled surface in an indoor environment. It can be assumed that the surface was stable and vibration-free (at least at the level perceived by human senses). No potential sources of ground vibration were identified. When the robot was objectively stationary, there were no moving parts in it (e.g., motors, fans, buzzers). Therefore, the scatter in the IMU sensor measurement results visible in the stationary states in Figure 8 was almost exclusively due to the sensor’s internal noise.

However, during robot movement, it is clearly visible that the measurement results for all acceleration and angular velocity components have greater dispersion than in stationary states. This is believed to be due to the operation of the wheel drive motors and multi-stage reduction gears operating dry (the noise emitted by these components was clearly audible). The second source of vibration appears to be the fine tread of the robot’s drive wheel tires, which can be confirmed by the greater dispersion of the measured results for the vertical acceleration component (along the robot’s Z axis) compared to the dispersion of the acceleration components in the X and Y axes (colloquially speaking, the robot “jumps” on the tread of its tires). Therefore, as a result of MTS optimization (step 5 of the algorithm in Figure 2), the acceleration components along the X and Y axes of the IMU sensor were removed from the set of diagnostic variables (even despite a slight change in the IMU orientation relative to the robot’s coordinate system axes).

5. Conclusions

The developed method for detecting the stationary state of a mobile robot was effective in all 20 test runs and correctly found all the areas where the robot was stationary. It clearly separated the standstill condition from moving along a straight line, which was difficult to accomplish using rotational speed-based measure described in [23]. The method is characterized by the following, among others:

- It utilizes multiple available sources of information describing the state of the object, represented by easily measurable signals obtained from the mobile robot’s sensors. These variables may be either continuous or discrete (categorical) [32]. Although the study considered only signals provided by the IMU sensor, namely the components of angular velocity and linear acceleration, the diagnostic variables of the MTS may be extended depending on the deployment context. Such extensions may include, for example, distance measurements to objects in the robot’s surroundings and/or measurements of changes in the robot’s position relative to those objects. Increasing the diversity and quantity of such sources can therefore enhance the reliability of the detection process.

- The method provides tools for objectively assessing which diagnostic variables are most and least useful (step 5 of the method). To this end, orthogonal arrays and the S/N ratio are employed. Depending on the characteristics of the robot’s operating environment and its sensors, these variables may be added to or removed from the MTS in a procedural manner.

- A numerical scale was introduced, with a threshold value T, that defines the normal (stationary) and abnormal (moving) states of the object/mobile robot.

- Information from multiple diagnostic variables is transformed (fused) into a single scalar variable, referred to as the Mahalanobis distance (MD). This value can then be referenced against the previously established numerical scale to assess the degree of deviation in the robot’s current state from the normal (stationary) state.

- The method accounts for the interdependencies between the diagnostic variables by computing the inverse covariance–variance matrix C−1. Incorporating the correlations among the relevant variables enhances the detection of abnormal states. Additionally, the method enables a reduction in the number of variables through vector-basis orthogonalization (the MTGS method [4]). This facilitates the integration of measurement results, for example, from multiple IMU sensors, which are inherently correlated. Such integration may, in turn, lead to an improvement in stationary-state detection accuracy.

- The method is easy to automate, both in terms of constructing the MTS (as shown in Figure 2) and in terms of its subsequent numerical implementation for real-time robot state identification. The Mahalanobis distance is computed in three steps: (i) standardization of the diagnostic variables; (ii) multiplication of the resulting vector by the matrix; and (iii) comparison of the obtained value with the threshold T. The simplicity of the procedure and the modest computational requirements enable the MTS to be implemented even on microcontrollers with limited memory resources and low processing power.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and A.K.; methodology, M.B., R.C., and M.R.; software, R.C.; validation M.R., W.S., and A.K.; formal analysis, W.S., M.R., and M.B.; investigation, R.C., M.B.; resources, R.C.; data curation, R.C. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C., M.B., P.S., and W.S.; writing—review and editing, A.K. and M.R.; visualization, R.C., M.B., P.S., and W.S.; supervision, M.B. and P.S.; project administration, M.B. and P.S.; funding acquisition, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is included in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AGV | Automated Guided Vehicle |

| AMR | Autonomous Mobile Robot |

| DoF | Degree(s) of Freedom |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| MD | Mahalanobis Distance |

| MEMS | Microelectromechanical system |

| MTGS | Mahalanobis–Taguchi–Gram–Schmidt (method) |

| MTS | Mahalanobis–Taguchi System |

| S/N | Signal-to-Noise (ratio) |

| ZUPT | Zero Velocity Update (method) |

Appendix A

Detailed results of detection of “non-moving robot” states with Mahalanobis distance method

NN-Robot was not moving; points classified as not moving. NP-Robot was not moving; points classified as moving. PP-Robot was moving; points classified as moving. PN-Robot was moving; points classified as not moving. Routes: Time-based route; route with stops described in [53]. Square 3 m × 3 m with diagonals, only initial stop, no in-route stops. Delivery: a closed path route simulating storage pickup and delivery with stops.

Table A1.

Gains of the input variables calculated according to equations taken from [32].

Table A1.

Gains of the input variables calculated according to equations taken from [32].

| Gain [dB] | ||||||

| Run | ωx | ωy | ωz | ax | ay | az |

| 1 | −0.20 | 1.12 | 2.15 | 1.08 | −4.13 | −0.92 |

| 2 | 0.19 | 1.08 | 2.41 | 0.53 | −3.53 | −1.58 |

| 3 | 2.21 | 0.98 | 1.36 | −3.00 | −1.63 | −0.03 |

| 4 | 2.21 | −0.61 | −1.92 | −1.61 | −1.10 | 1.75 |

| 5 | 1.95 | 0.75 | 1.14 | −2.62 | −2.09 | 0.32 |

| 6 | 2.35 | 0.67 | 1.36 | −2.16 | −2.81 | −0.22 |

| 7 | 2.13 | 0.84 | 1.63 | −1.65 | −2.64 | −0.64 |

| 8 | −0.27 | −2.52 | 1.12 | 0.63 | −1.08 | 0.29 |

| 9 | 2.27 | −2.18 | −4.50 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 1.65 |

| 10 | −0.05 | −1.24 | −2.71 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 1.26 |

| 11 | 0.05 | −0.95 | −2.31 | 0.42 | 0.83 | 1.37 |

| 12 | 2.75 | 0.30 | 0.24 | −3.69 | −2.28 | 0.99 |

| 13 | 2.51 | 0.32 | 0.78 | −3.58 | −1.73 | 0.81 |

| 14 | 2.12 | 0.64 | 0.85 | −3.13 | −1.59 | 0.59 |

| 15 | 1.27 | 0.55 | 0.81 | −2.14 | −0.46 | −0.10 |

| 16 | 2.10 | 0.92 | 1.06 | −3.28 | −2.11 | 0.30 |

| 17 | 1.87 | −0.51 | 0.49 | −1.37 | −2.10 | 0.70 |

| 18 | 2.12 | 0.66 | 0.83 | −1.91 | −2.30 | −0.05 |

| 19 | 2.54 | 0.85 | 0.90 | −2.98 | −1.71 | −0.22 |

| 20 | 2.05 | 0.27 | 0.80 | −1.46 | −2.08 | 0.07 |

| Average | 1.61 | 0.10 | 0.32 | −1.54 | −1.65 | 0.32 |

ωx, ωy, ωz—readings from the gyroscope (rotational speed; sensor’s axes X, Y, Z); ax, ay, az—readings from accelerometer (linear acceleration; sensor’s axes X, Y, Z).

Table A2.

Number of data points classified in test runs.

Table A2.

Number of data points classified in test runs.

| Full Data Set (All 6 DoF) | Limited Data Set (ωx, ωy, ωz, az) | ||||||||

| Run | Route | NN | NP | PP | PN | NN | NP | PP | PN |

| 1 | Time-based route [52] | 4205 | 526 | 9248 | 12 | 4416 | 315 | 9157 | 103 |

| 2 | 3643 | 486 | 9271 | 28 | 4065 | 64 | 9208 | 91 | |

| 3 | 1281 | 1278 | 11,427 | 0 | 2528 | 31 | 11,345 | 82 | |

| 4 | 8533 | 868 | 1627 | 0 | 9092 | 309 | 1615 | 12 | |

| 5 | 2018 | 1510 | 9712 | 1 | 3395 | 133 | 9691 | 22 | |

| 6 | 1957 | 636 | 11,026 | 18 | 2536 | 57 | 10,988 | 56 | |

| 7 | 2726 | 346 | 9751 | 23 | 3044 | 28 | 9710 | 64 | |

| 8 | 2541 | 114 | 11,316 | 16 | 2473 | 182 | 11,319 | 13 | |

| 9 | Square 3 × 3 m | 1560 | 84 | 12,354 | 0 | 1581 | 63 | 12,354 | 0 |

| 10 | 1495 | 26 | 12,477 | 0 | 1471 | 50 | 12,476 | 1 | |

| 11 | 137 | 1092 | 12,766 | 0 | 140 | 1089 | 12,766 | 0 | |

| 12 | Delivery route | 820 | 2339 | 9055 | 0 | 2990 | 169 | 9052 | 3 |

| 13 | 1559 | 2480 | 9104 | 0 | 3004 | 1035 | 9103 | 1 | |

| 14 | 2397 | 1456 | 9483 | 0 | 3359 | 494 | 9474 | 9 | |

| 15 | 4072 | 919 | 9004 | 0 | 4901 | 90 | 8994 | 10 | |

| 16 | 2309 | 1315 | 9197 | 0 | 3293 | 331 | 9197 | 0 | |

| 17 | 2884 | 1350 | 9404 | 0 | 3682 | 552 | 9400 | 4 | |

| 18 | 5732 | 36 | 1947 | 0 | 5712 | 56 | 1940 | 7 | |

| 19 | 2212 | 1407 | 9091 | 0 | 3529 | 90 | 9086 | 5 | |

| 20 | 2902 | 157 | 9225 | 10 | 2865 | 194 | 9213 | 22 | |

| Total (all routes): | 54,983 | 18,425 | 186,485 | 108 | 68,076 | 5332 | 186,088 | 505 | |

References

- Gnap, J.; Jagelčák, J.; Marienka, P.; Frančák, M.; Kostrzewski, M.; Gnap, J.; Jagelčák, J.; Marienka, P.; Frančák, M.; Kostrzewski, M. Application of MEMS Sensors for Evaluation of the Dynamics for Cargo Securing on Road Vehicles. Sensors 2021, 21, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieoczym, A.; Caban, J.; Stopka, O.; Krajka, T.; Stopková, M. The Planning Process of Transport Tasks for Autonomous Vans. Open Eng. 2021, 11, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondruš, J.; Jančár, A.; Gogola, M.; Varga, P.; Šarić, Ž.; Caban, J. Smartphone Sensors in Motion: Advancing Traffic Safety with Mobile Technology. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanella, R.; Accardo, D.; Moriello, R.S.L.; Angrisani, L.; Simone, D.D. An Innovative Strategy for Accurate Thermal Compensation of Gyro Bias in Inertial Units by Exploiting a Novel Augmented Kalman Filter. Sensors 2018, 18, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, J.; Skog, I. Fifteen Years of Progress at Zero Velocity: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucki, M.; Barisic, B.; Ocenasova, L. Dynamic Calibration of Air Gauges. Arch. Technol. Masz. Autom. 2010, 30, 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Surblys, V.; Kozłowski, E.; Matijošius, J.; Gołda, P.; Laskowska, A.; Kilikevičius, A. Accelerometer-Based Pavement Classification for Vehicle Dynamics Analysis Using Neural Networks. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilek, P. Vehicle Wheel Positioning Innovation on a Machine for Measuring the Contact Parameters between a Tyre and the Road. Arch. Motoryz. 2023, 100, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, P.; Siczek, K.; Karpushkin, V.; Nikulenkov, O.; Krzemieniewski, A.; Mierzejewska, P.; Gołębiowski, W.; Seńko, J.; Szosland, A.; Woźniak, M. Precision Method of Velocity Determination Based on Measurements of Car Body Deformation—Non-Linear Method for Intermediate Vehicle Class. Lect. Notes Eng. Comput. Sci. 2018, 2236, 746–750. [Google Scholar]

- Nieoczym, A.; Caban, J.; Dudziak, A.; Stoma, M. Autonomous Vans—The Planning Process of Transport Tasks. Open Eng. 2020, 10, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Qin, W. Safety Risk Assessment for Connected and Automated Vehicles: Integrating FTA and CM-Improved AHP. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 257, 110822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samociuk, W. Modernization of the Control System to Reduce a Risk of Severe Accidents during Non-Pressurized Ammonia Storage Modernizacja Układu Sterowania w Celu Redukcji Ryzyka Poważnych Awarii Bezciśnieniowego Przechowywania Amoniaku. Przem. Chem. 2016, 1, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujna, M.; Prístavka, M.; Lee, C.K.; Borusiewicz, A.; Samociuk, W.; Beloev, I.; Malaga-Toboła, U. Reducing the Probability of Failure in Manufacturing Equipment by Quantitative FTA Analysis. Agric. Eng. 2023, 27, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, A.; Bhat, K.N.; Kurian, T. Fundamentals of Navigation and Inertial Sensors; PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd.: Delhi, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Noureldin, A.; Karamat, T.; Georgy, J. Fundamentals of Inertial Navigation, Satellite-Based Positioning and Their Integration; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, D.; Yu, C.; Kong, L. The Development of Micromachined Gyroscope Structure and Circuitry Technology. Sensors 2014, 14, 1394–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaro, V.M.N.; Cuccovillo, A.; Vaiani, L.; De Carlo, M.; Campanella, C.E. Gyroscope Technology and Applications: A Review in the Industrial Perspective. Sensors 2017, 17, 2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, W.A.; Howard, I.; Mazhar, I.; McKee, K. A Review of MEMS Vibrating Gyroscopes and Their Reliability Issues in Harsh Environments. Sensors 2022, 22, 7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feller, W. An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 1, ISBN 978-81-265-1805-0. [Google Scholar]

- Barshan, B.; Durrant-Whyte, H.F. Inertial Navigation Systems for Mobile Robots. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 2002, 11, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Xue, L.; Qin, W.; Yuan, G.; Yuan, W. An Integrated MEMS Gyroscope Array with Higher Accuracy Output. Sensors 2008, 8, 2886–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Xue, L.; Chang, H.; Yuan, G.; Yuan, W. Signal Processing of MEMS Gyroscope Arrays to Improve Accuracy Using a 1st Order Markov for Rate Signal Modeling. Sensors 2012, 12, 1720–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cechowicz, R. Bias Drift Estimation for MEMS Gyroscope Used in Inertial Navigation. Acta Mech. Autom. 2017, 11, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddle, J.R. Trends in Inertial Systems Technology for High Accuracy AUV Navigation. In Proceedings of the 1998 Workshop on Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (Cat. No. 98CH36290), Cambridge, MA, USA, 21 August 1998; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, A. Inertial Surveying Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Stączek, P.; Pizoń, J.; Danilczuk, W.; Gola, A. A Digital Twin Approach for the Improvement of an Autonomous Mobile Robots (AMR’s) Operating Environment—A Case Study. Sensors 2021, 21, 7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, R.; Jackson, L.M.; Dunnett, S.J. Automated Guided Vehicle Mission Reliability Modelling Using a Combined Fault Tree and Petri Net Approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 92, 1825–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Yang, H.; Höflinger, F.; Reindl, L.M. Adaptive Zero Velocity Update Based on Velocity Classification for Pedestrian Tracking. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 2137–2145. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Qiu, S.; Gao, Q. Stance-Phase Detection for ZUPT-Aided Foot-Mounted Pedestrian Navigation System. IEEEASME Trans. Mechatron. 2015, 20, 3170–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiling, W.; Guoqiang, F.; Huachao, Y.; Yafeng, L.; Yi, Y.; Xuan, X. A Loosely Coupled MEMS-SINS/GNSS Integrated System for Land Vehicle Navigation in Urban Areas. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Vehicular Electronics and Safety (ICVES), Vienna, Austria, 27–28 June 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, G.; Chowdhury, S.; Wu, Y. Quality Engineering: The Taguchi Method. In Taguchi’s Quality Engineering Handbook; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, G.; Taguchi, G.; Jugulum, R. The Mahalanobis-Taguchi Strategy: A Pattern Technology System; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalanobis, P.C. On the Generalized Distance in Statistics. Sankhyā Indian J. Stat. Ser. 2008- 2018, 80, S1–S7. [Google Scholar]

- Woodall, W.H.; Koudelik, R.; Tsui, K.-L.; Kim, S.B.; Stoumbos, Z.G.; Carvounis, C.P. A Review and Analysis of the Mahalanobis—Taguchi System. Technometrics 2003, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xu, X.; Cao, K.; Yuan, S.; Xie, L. Unsupervised Anomaly Detection for Autonomous Robots via Mahalanobis SVDD with Audio-IMU Fusion. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.05811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnam, R.B.; Rai, B.; Singh, N. Tool-Condition Monitoring from Degradation Signals Using Mahalanobis–Taguchi System Analysis. In Proceedings of the ASI’s 20th Annual Symposium of Robust Engineering, Novi, MI, USA, 2004; pp. 343–351. [Google Scholar]

- Cudney, E.A.; Paryani, K.; Ragsdell, K.M. Applying the Mahalanobis-Taguchi System to Vehicle Ride. Int. J. Ind. Syst. Eng. 2007, 1, 251–259. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrier, S.; Waegli, A.; Skaloud, J.; Victoria-Feser, M.-P. Fault Detection and Isolation in Multiple MEMS-IMUs Configurations. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2012, 48, 2015–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Chow, T.W. Anomaly Detection of Cooling Fan and Fault Classification of Induction Motor Using Mahalanobis–Taguchi System. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 5787–5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowiec, M.; Caban, J.; Giri, A.; Syed, A.A. Study of Dynamics of Car Suspension Model: Dynamic Elimination of Road Surface Vibration. In Proceedings of the 24th International Scientific Conference Engineering for Rural Development, Jelgava, Latvia, 21–23 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C.-F.; Ho, L.-H.; Tsai, S.-B.; Hsiao, Y.-C.; Zhai, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chang, L.-C.; Shang, Z. Applying the Mahalanobis–Taguchi System to Improve Tablet PC Production Processes. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtra, A.C.; Tur, J.M.M. IMU and Cable Encoder Data Fusion for In-Pipe Mobile Robot Localization. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Conference on Technologies for Practical Robot Applications (TePRA), Woburn, MA, USA, 22–23 April 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.A.; Riaz, S.; Iqbal, J. Surface Estimation of a Pedestrian Walk for Outdoor Use of Power Wheelchair Based Robot. Life Sci. J. 2013, 10, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Lee, D.; Oh, T.; Choi, H.-T.; Myung, H. A Probabilistic Feature Map-Based Localization System Using a Monocular Camera. Sensors 2015, 15, 21636–21659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Chen, S.; Yang, B.; Chen, K. Feedback Robust Cubature Kalman Filter for Target Tracking Using an Angle Sensor. Sensors 2016, 16, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadi, M.; Esfahani, E.T. A Robust Automatic Gait Monitoring Approach Using a Single Imu for Home-Based Applications. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2017, 17, 1750077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Organero, M.; Ruiz-Blázquez, R. Detecting Steps Walking at Very Low Speeds Combining Outlier Detection, Transition Matrices and Autoencoders from Acceleration Patterns. Sensors 2017, 17, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Chen, J.; De Strycker, L. An Outlier Detection Method Based on Mahalanobis Distance for Source Localization. Sensors 2018, 18, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Ji, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Sun, W. Refractory High-Entropy Alloys Fabricated Using Laser Technologies: A Concrete Review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 7497–7524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Blasio, G.; Quesada-Arencibia, A.; García, C.R.; Molina-Gil, J.M.; Caballero-Gil, C. Study on an Indoor Positioning System for Harsh Environments Based on Wi-Fi and Bluetooth Low Energy. Sensors 2017, 17, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Zhang, S.-B. A Novel Adaptively-Robust Strategy Based on the Mahalanobis Distance for GPS/INS Integrated Navigation Systems. Sensors 2018, 18, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cechowicz, R. Indoor Mobile Robot Attitude Estimation with MEMS Gyroscope. In Proceedings of the ITM Web of Conferences, Wuhan, China, 5 September 2017; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2017; Volume 15, p. 05010. [Google Scholar]

- LSM6DS3TR-C|Product—STMicroelectronics. Available online: https://www.st.com/en/mems-and-sensors/lsm6ds3tr-c.html (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Skog, I.; Handel, P.; Nilsson, J.-O.; Rantakokko, J. Zero-Velocity Detection—An Algorithm Evaluation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 57, 2657–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatini, A.M. Quaternion-Based Strap-down Integration Method for Applications of Inertial Sensing to Gait Analysis. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2005, 43, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kone, Y.; Zhu, N.; Renaudin, V.; Ortiz, M. Machine Learning-Based Zero-Velocity Detection for Inertial Pedestrian Navigation. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 12343–12353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, B.; Kelly, J. LSTM-Based Zero-Velocity Detection for Robust Inertial Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Nantes, France, 24–27 September 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Pan, X. Deep Learning for Inertial Positioning: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 10506–10523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grejner-Brzezinska, D.A.; Yi, Y.; Toth, C.K. Bridging GPS Gaps in Urban Canyons: The Benefits of ZUPTs. Navigation 2001, 48, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.