Abstract

Accurate plant leaf image segmentation plays a crucial role in species recognition, phenotypic analysis, and disease detection. However, most segmentation models perform poorly in complex field environments due to challenges such as overlapping leaves and uneven sunlight. This research proposes an Edge-Aware High-Frequency Preservation Network (EHPNet) for leaf segmentation in complex field environments. Specifically, a High-Frequency Edge Fusion Module (HEFM) is introduced into the skip connections to preserve high-frequency edge information during feature extraction and enhance boundary localization. In addition, a Structural Recalibration Attention Module (SRAM) is incorporated into the decoder to refine edge structural features across multiple scales and retain spatial continuity, which leads to more accurate reconstruction of leaf boundaries. Experimental results on a composite dataset constructed from Pl@ntLeaves and ATLDSD show that EHPNet achieves 98.25%, 99.25%, 99.03%, 98.51%, and 98.77% in mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, respectively. Compared with state-of-the-art methods, EHPNet achieves superior overall performance, which demonstrates its effectiveness for leaf segmentation in complex field environments.

1. Introduction

Plant leaf segmentation is a prerequisite for various applications in precision agriculture, such as species recognition [1], phenotypic analysis [2], and disease detection [3]. Specifically, plant leaf segmentation enables the extraction of biomass characteristics such as area, shape, and texture. These characteristics provide important indicators of plant growth patterns and plant health status, which support effective crop monitoring and management [4]. Consequently, even subtle segmentation errors can propagate through subsequent analyses, which leads to unreliable trait extraction and potentially affects agricultural decision-making. Traditional plant leaf segmentation methods rely on manual measurements, which are time-consuming and cause irreversible damage to the leaf. With the development of image analysis technologies, image-based methods have gained increasing attention as efficient and non-destructive approaches to plant leaf segmentation.

Early image-based leaf segmentation methods include threshold methods [5], region-based methods [6], clustering methods [7], and edge detection methods [8]. Although numerous leaf segmentation methods have been proposed, they are sensitive to noise and easily generate fragmented boundaries in complex field environment. Moreover, these methods heavily rely on manual feature design, initial parameter selection, and complex preprocessing procedures, which require expert knowledge and make them less practical for widespread applications.

In recent years, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have shown great potential in plant leaf segmentation, which can automatically extract advanced image features with greater robustness and reduced human intervention. Numerous researchers have conducted extensive studies on CNN-based methods. For example, Wang et al. [9] proposed a two-stage soybean leaf segmentation method, which utilized bounding box localization results to guide the segmentation of the target leaf area. Similarly, Yang et al. [10] employed YOLOv8 to extract regions of interest from leaf images and introduced strip pooling to efficiently capture the structural features of bar leaves and slender petioles. In terms of boundary refinement, Hong et al. [11] combined Mask R-CNN with OTSU preprocessing, which made the leaf regions more prominent while suppressing shadows, withered grass, and soil elements in the background. Zhu et al. [12] proposed LD-DeepLabV3+ to segment apple leaves and disease spots, which introduced an adaptive loss function to reduce the weight of easily classified pixels and make the model focus on leaf edges. By combining CNN and Transformer with a bidirectional attention fusion strategy, Fang et al. [13] proposed BAF-Net for pepper leaf segmentation which effectively integrated local and global contextual information. In the context of limited labeled data, Gao et al. [14] proposed a self-supervised strategy to segment rice and wheat field images with highly variable field backgrounds. Lin et al. [15] presented a self-supervised leaf segmentation framework for images under complex lighting conditions, which combined features extracted from the CNN-based network with fully connected conditional random fields.

Although the above-mentioned methods have significantly improved leaf segmentation accuracy in complex field environments, they tend to produce blurred or fragmented results in identifying weak boundaries, such as overlapping leaves or uneven sunlight, since they overlook high-frequency edge details in the image, which are prone to loss during downsampling and convolution operations of the encoding process [16]. Furthermore, these methods rely on heuristic and non-learnable upsampling operations in the decoder, which lack the ability to recover fine-grained structural details and preserve spatial continuity [17,18].

This research proposed an Edge-Aware High-Frequency Preservation Network (EHPNet) for leaf segmentation in complex field environments. A High-frequency Edge Fusion Module (HEFM) was inserted into the skip connections to preserve high-frequency edge details during the encoding process. It applied attention-driven refinement and weight distribution to integrate edge cues from classical edge extraction methods with detailed semantic features, which enhanced edge feature representation and robustness in complex environments. In addition, a Structural Recalibration Attention Module (SRAM) SRAM was designed to refine edge structure information and retain spatial continuity across multiple scales. It captured multi-scale features using strip convolutions and dynamic attention allocation to enable the model to focus on both fine-grained details and larger structural patterns from different directions, which improved boundary localization and optimized boundary details during the decoding stage. The main contributions of this research are as follows:

- A novel method for leaf segmentation was proposed, which improved segmentation accuracy under complex field environment.

- The High-frequency Edge Fusion Module (HEFM) was introduced to preserve high-frequency edge details during the encoding process and enhance boundary localization.

- The Structural Recalibration Attention Module (SRAM) was introduced to refine edge structure information and preserve spatial continuity during the decoding process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

The diversity and realism of datasets are essential for developing robust leaf segmentation models. The Pl@ntLeaves dataset [19] contains images from diverse plant species and is widely used for leaf segmentation research. However, only 223 samples in this dataset were collected in field environments, which restricts the effectiveness for model training in practical field applications. Meanwhile, the Apple Tree Leaf Disease Segmentation Dataset [20] (ATLDSD) provides a substantial number of leaf images captured in complex environments, but it is limited to apple leaves and lacks species diversity. In order to address these limitations, this research constructed a composite dataset by combining the field images from Pl@ntLeaves and ATLDSD, which provides a more realistic benchmark for leaf segmentation tasks and enhances model robustness. Samples of the Pl@ntLeaves dataset and ATLDSD are shown in Figure 1. Specifically, the composite dataset consists of 1017 images, comprising 223 images from Pl@ntLeaves and 794 images from ATLDSD. The original annotations from both datasets were retained and standardized into a unified binary leaf-mask format, with a consistency check to ensure proper alignment between image and mask. The dataset was randomly split into training, validation, and test sets with an approximate 8:1:1 ratio. The splitting details are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Sample images from dataset (a) Samples from Pl@ntLeaves dataset (b) Samples from ATLDSD.

Table 1.

The splitting details of the composite datasets.

In order to reduce overfitting during model training, data augmentation methods were adopted to expand the training set and improve generalization. These methods included random rotations, flips, brightness adjustment, and contrast change. Ultimately, the composite dataset contained 3163 images, which included 1017 original images and 2443 augmented images.

2.2. Methods

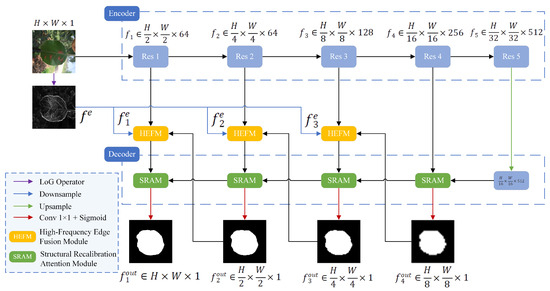

The proposed EHPNet was built upon the U-Net architecture, which comprised an encoder, a decoder, High-Frequency Edge Fusion Module (HEFM), and Structural Recalibration Attention Module (SRAM). The overall architecture is shown in Figure 2. The encoder adopted ResNet-34 [21] to capture high-level features from leaf images, which struck a balance between performance and computational cost. ResNet-34 consisted of five layers, where denoted the layer and its output was denoted as . The Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) operator was applied to the original image to extract edges that contain high-frequency details, denoted as . The LoG operator combines Gaussian smoothing with second-order differentiation, which provides accurate edge localization and sharpening while maintaining good computational efficiency. Compared to traditional operators such as Sobel or Canny, the LoG operator can better suppress background texture noise and preserve finer leaf boundaries in complex environments. It was downsampled into three maps, denoted as , each with the same resolution as . Subsequently, an HEFM was inserted into the skip connections of the first three layers to preserve edge details with edge maps . At the layer, served as one of the inputs to the HEFM. At decoding stage, EHPNet progressively reconstructed high-resolution representations through SRAM and produced predicted maps at different scales, denoted as . SRAM optimized boundary details and improved the capture of information across different scales.

Figure 2.

The architecture of EHPNet.

2.2.1. High-Frequency Edge Fusion Module (HEFM)

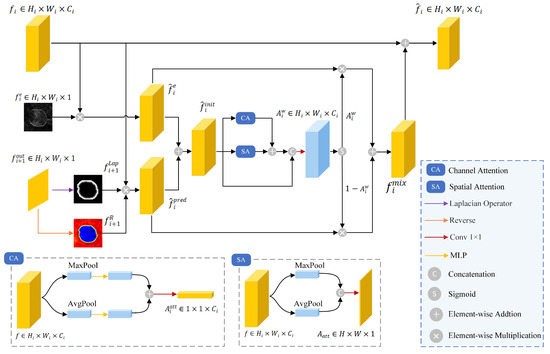

High-frequency edge details are essential for identifying weak leaf boundaries, but they are easily lost during downsampling and convolution operations. Therefore, HEFM was introduced to preserve high-frequency edge details. The structure of the HEFM is shown in Figure 3. At the layer, the HEFM took three inputs: output from , edge map , and predicted map generated from layer. The HEFM processed these inputs and generated an enhanced feature map denoted as .

Figure 3.

The architecture of HEFM.

The edge map provides superior edge localization and sharpening effects. It was element-wise multiplied with to obtain , which contained high-frequency details, expressed as

where ⊗ denoted element-wise multiplication.

Meanwhile, the predicted map was used to generate two attention maps that emphasize boundary regions: (i) a boundary attention map generated from through the LoG operator, and (ii) a reverse attention map generated from via reverse attention [22], which was calculated as . The two attention maps were element-wise multiplied with to obtain , which helped refine boundary localization by focusing on critical boundary regions, defined as

Subsequently, and were summed as the initial fusion feature . Spatial and channel attention mechanisms were applied to emphasize the key information in . The two attention maps were added and concatenated with to generate a weight , which was computed as

where and represented spatial attention and channel attention, respectively, and represented the convolution operation with a kernel size of . and were multiplied by and , respectively. These two features culminated in the creation of a fused feature , which reduced noise interference while containing edge guidance, characterized as

where denoted the Sigmoid function.

The output of HEFM was computed by summing and , which enhanced the focus on edge details, characterized as follows:

2.2.2. Structural Recalibration Attention Module (SRAM)

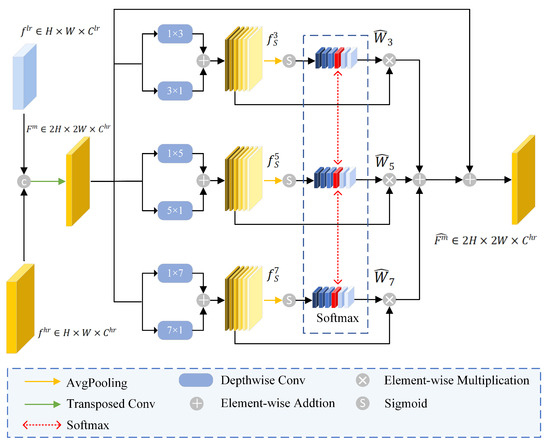

Refining structural information during the decoding stage is crucial to preserving spatial continuity and recovering fine-grained details. This research introduced SRAM into the decoder to refine edge structural details and optimize object boundaries. The structure of the SRAM is shown in Figure 4. The SRAM took two inputs: from current layer via skip connection, and output feature from deeper decoder layer denoted as . SRAM processed these inputs and generated a feature map denoted as .

Figure 4.

The architecture of SRAM.

Firstly, and were fused via a transposed convolution operation to produce , denoted as

Secondly, depthwise strip convolutions with various kernel sizes and orientations were applied to capture comprehensive boundary structure from . It resulted in three feature maps that are sensitive to directional structures such as leaf edges, as shown below:

where denoted different kernel sizes, represented depthwise strip convolution, H and W denoted horizontal and vertical directions, respectively.

Average pooling was subsequently applied to compute the channel weights of the feature , as shown below:

where represented the average pooling operation. Softmax operation was applied to the same channel across to compute the redistributed attention weights . This process avoided the model to overly focus on one single scale, characterized as follows:

where was the weight of channel at scale S, C denoted as number of channels, and was the newly assigned weight of channel after the softmax operation.

Finally, were element-wise multiplied with , and summed with . This process created an enhanced feature , which contained edge structure information across different scales, as shown below:

2.2.3. Loss Function

In leaf segmentation tasks, the combination of Binary Cross-Entropy loss () and Dice loss () has shown great effectiveness [23]. This combination mitigates foreground-background class imbalance and maintains pixel-level classification precision. However, the BCE and Dice losses are based on integrals over the segmentation regions, which are insensitive to small boundary errors and lead to jagged leaf contours. In this research, Boundary loss [24] () is employed to enhance the sensitivity to boundary discrepancies. It weights each pixel’s error by computing its signed distance to ground-truth boundary, and directs gradients toward boundary pixels. The Boundary loss is defined as

where is the spatial domain of the image, is the signed distance map derived from the ground truth mask G, and is the softmax probability output.

Consequently, a combination of , , and was used in this research to enhance model convergence speed and training stability. Notably, was applied to the final output as it captured the most precise boundary information. The loss function of this research can be expressed as

where L represents the number of output predicted maps and is a coefficient to balance the importance between loss functions. is the predicted map at the layer, and is the ground truth at the layer. In this research, and .

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Setup

All experiments were conducted in the Ubuntu 20.04.6 environment with Python 3.9 and PyTorch 2.1.2. The experimental platform configuration is an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU, Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-13620H CPU, 256.0 GB RAM, CUDA 12.1. During the training phase, all images were resized to pixels. The hyperparameter settings are as follows: the number of epochs is 100, and the batch size is 8. The Adam optimizer was employed with an initial learning rate of , which was halved after every 10 epochs. All backbone variants and compared models were trained under an identical training protocol, including the same loss function, data augmentation strategy, optimizer settings, learning rate schedule, and training, validation, and test splits.

3.2. Evaluation Indicators

In this research, five evaluation indices were employed to evaluate the proposed method: mean intersection over union (mIoU), pixel accuracy (PA), pixel recall (PR), pixel precision (PP), and F1 score (F1). mIoU is the ratio of the intersection to the union of the predicted results and the ground truth for each class. PA is the ratio of correctly predicted pixels to the total number of pixels. PP is the proportion of correctly predicted positive pixels among all the pixels predicted as positive. PR is the proportion of correctly predicted positive pixels out of all actual positive pixels. F1 combines PP and PR, which provides a balanced measure of model performance. The formulas for mIoU, PA, PP, PR, and F1 are defined as follows:

where TP is the number of true positives, TN is the number of true negatives, FP is the number of false positives, FN is the number of false negatives, and N is the number of categories. In this research, , which represents the leaf region and background classes.

3.3. Selection of Backbone Network

Backbone choice influences segmentation accuracy, generalization performance, and computational complexity. In selecting the optimal backbone architecture, this research conducted a comparative experiment to select the optimal backbone by using MobileNetV2 [25], VGG16 [26], ResNet-18, ResNet-34, and ResNet-50 to train and evaluate the proposed EHPNet on the dataset. The results are presented in Table 2. In addition to segmentation metrics, FLOPs and parameters were used to evaluate the computational efficiency.

Table 2.

Comparison with different backbone networks.

As shown in Table 2, ResNet-50 slightly outperformed ResNet-34 in terms of segmentation accuracy, but the FLOPs and parameters increased by 25.67 G and 32.14 M, respectively. This gap mainly stems from deeper bottleneck blocks and wider channels, which propagate through skip connections and decoder, and sharply increase the computational complexity. Conversely, lightweight backbones such as MobileNetV2 and ResNet-18 achieved lower computation and parameters, but their shallower depth and narrower channels limit the detail of leaf boundary representations, which lead to lower segmentation performance. Based on the results, ResNet-34 was selected as the backbone for EHPNet as it achieved a favorable balance between segmentation accuracy and computational complexity.

3.4. Different Combinations of Loss Function

Loss function plays a critical role in the accuracy and robustness of segmentation models. In order to evaluate the influence of different combinations of loss function on segmentation performance, this research conducted a series of comparative experiments. Five different loss function settings were evaluated, where indicated that boundary loss applied to all outputs, and referred to boundary loss applied to final output.

As shown in Table 3, the introduction of boundary loss further improved segmentation accuracy by minimising the distance between the predicted boundary and the ground-truth boundary. Furthermore, boundary loss applied to the final output resulted in better performance than its application to all outputs. This avoided the noise introduced by low-resolution feature maps and preserved fine-grained boundary detail. Based on these results, the combination of binary cross-entropy loss, dice loss, and boundary loss was adopted as the default loss function in all subsequent experiments, as it balanced pixel-wise supervision, region-level consistency, and contour refinement.

Table 3.

Comparison with different loss function combinations. The best results are in bold.

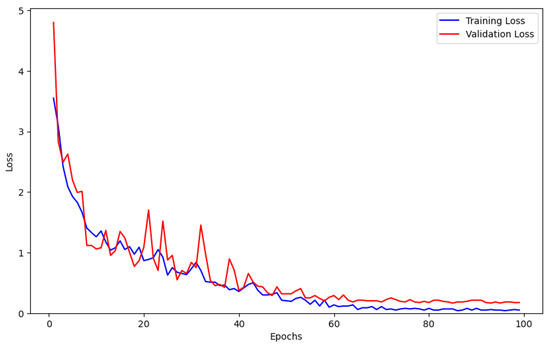

3.5. Model Optimization and Loss Curve Evaluation

In order to evaluate the optimization behavior of our method, this research plot the training and validation loss across epochs. As shown in Figure 5, the model’s loss function exhibits a rapid decline, eventually stabilizing, which demonstrates the strong feature learning ability of the proposed algorithm. When the model trained 60 epochs, the loss function gradually tended to be stable, and when the model trained 100 epochs, it basically converged, which indicated that the model was saturated at this time, and that the detection performance of the model was optimal.

Figure 5.

Training and validation loss curves.

3.6. Comparison with Different Model

This research compared the proposed EHPNet with state-of-the-art methods in leaf segmentation (U-Net [27], Attention U-Net [28], DeeplabV3+ [29], HRNet [30], and SegFormer [31]) to validate its performance on the composite dataset. The evaluation involved both quantitative analysis and qualitative comparison. In addition to segmentation metrics, FLOPs and parameter were used to evaluate the performance.

Table 4 shows the quantitative results of different methods. EHPNet outperformed all state-of-the-art methods on the leaf segmentation dataset. Compared with SegFormer, EHPNet achieved 1.2% improvement in mIoU, and 0.5%, 1.32%, 0.45%, and 0.88% in PA, PP, PR, and F1, respectively. Notably, the computation cost and parameter count of EHPNet are on a par with HRNet and SegFormer, which show that the performance incurs no additional computational burden. These improvements validate the effectiveness of EHPNet in leaf segmentation.

Table 4.

Comparison with different segmentation methods. The best results are in bold.

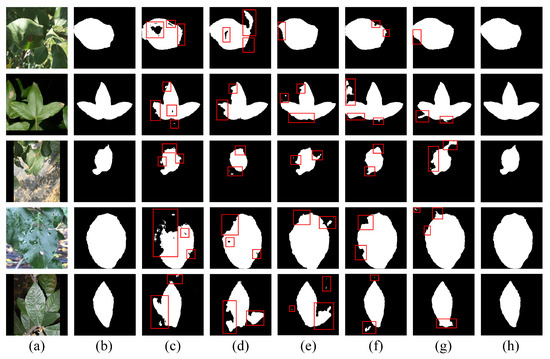

Figure 6 presents qualitative comparisons to support these conclusions. As shown in Figure 6c,d, it can be observed that traditional models like U-Net and Attention U-Net often produce fragmented or incomplete leaf regions, because they rely on simple convolutional operations and skip connections, which are insufficient to capture fine-grained features in complex environments. As shown in Figure 6e–g, although advanced models such as DeeplabV3+, HRNet, and SegFormer introduce multi-scale context aggregation, high-resolution representations, and global context modeling respectively, they still struggle to accurately segment fine boundaries as they lack explicit edge awareness. As shown in Figure 6h, EHPNet can clearly segment the entire target leaf. These advantages stem from the edge-aware enhancements introduced by HEFM and the structural recalibration provided by SRAM.

Figure 6.

The segmentation results of different methods. The red boxes indicate regions with segmentation errors. (a) Original image. (b) Ground truth. (c) U-Net. (d) Attention U-Net. (e) DeepLabV3+. (f) HRNet. (g) SegFormer. (h) EHPNet.

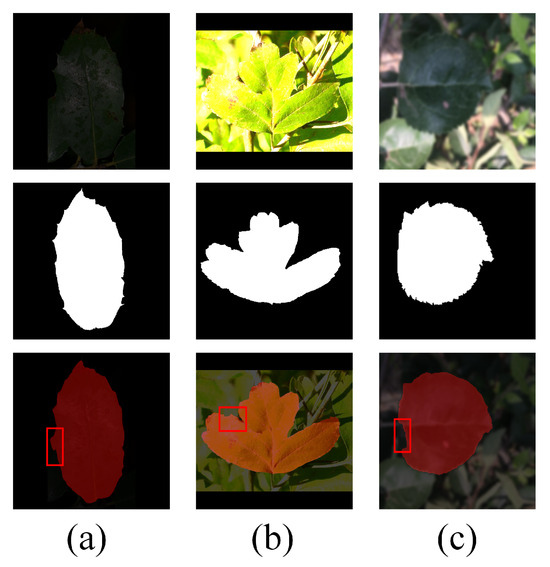

Overall, the proposed method demonstrates strong performance in leaf segmentation under real-world conditions. However, due to the uncertainties associated with sample collection in field environments, such as extreme lighting conditions and image blurriness, some errors in segmentation still occurred. Figure 7 presents the segmentation performance of EHPNet under these challenging conditions. As shown in Figure 7a,b, EHPNet is still able to perform segmentation when the environment is either too dark or overexposed, but there are instances of misdetection. As shown in Figure 7c, when the image is blurred, it poses significant challenges to boundary refinement, which highlights the difficulty in accurately segmenting fine details under such conditions. Despite these challenges, EHPNet continues to exhibit robust performance in most practical scenarios.

Figure 7.

Segmentation fault analysis. The red boxes indicate regions with segmentation errors. (a) Insufficient light. (b) Overexposure. (c) Blurred image.

3.7. Ablation Study

In this section, an ablation study was designed to validate the effectiveness of each module in EHPNet. In addition to segmentation metrics, FLOPs, parameter and inference latency (ms/image) were used to evaluate the performance. The latency was measured under the experimental setting with a batch size of 1. In order to evaluate the impact of each component on performance, a baseline model was constructed, the HEFM was replaced with a skip connection, and SRAM was replaced with standard U-Net decoder structure. As shown in Table 5, the mIoU, PA, PP, PR, and F1 of the Baseline were 95.70%, 98.18%, 98.02%, 95.76%, and 96.87%, respectively. When HEFM was introduced, these metrics were improved by 2.3%, 0.96%, 0.44%, 2.77%, and 1.72%, respectively, while SRAM produced improvements of 2.16%, 0.9%, 0.57%, 2.64%, and 1.62%. These substantial improvements show the importance of high-frequency edge preservation and structural information refinement within the network. Finally, compared with the baseline, when both HEFM and SRAM were introduced, the mIoU, PA, PP, PR, and F1 of the EHPNet improved by 2.55%, 1.07%, 1.01%, 3.27%, and 1.9%, respectively, with only a minimal increase in model parameters and FLOPs (+0.81M Params and +0.48G FLOPs). These results demonstrate their complementary roles in addressing different challenges in complex field environments. Meanwhile, compared with the baseline, the latency of EHPNet increased by only 1.1 ms (from 8.1 ms to 9.2 ms), which demonstrates that EHPNet introduces only a modest runtime overhead and supports real-time segmentation in practical field applications.

Table 5.

Result of ablation study on EHPNet. The best results are in bold.

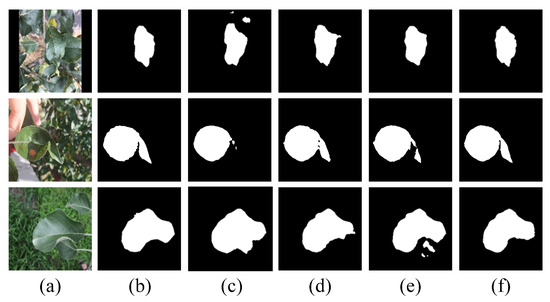

Visual comparisons of this ablation study illustrate the impact of each component on segmentation performance. As shown in Figure 8, the Baseline produced incomplete masks and failed to delineate fine-grained leaf boundaries in cluttered scenes. The introduction of HEFM preserved high-frequency edge details lost during encoding stage, which resulted in more coherent contours around individual leaves. The introduction of SRAM mitigated structural fragmentation by eliminating false positives and enhancing spatial continuity during the decoding stage. When both modules were combined in EHPNet, the segmentation results exhibited improved completeness, cleaner contours, and more accurate separation of overlapping regions. These visual outcomes align closely with the quantitative improvements presented in Table 5, which confirms the effectiveness of HEFM and SRAM in addressing the challenges of complex field environments.

Figure 8.

Visual results of ablation study on EHPNet. (a) Original image. (b) Ground truth. (c) Baseline (d) with HEFM and (e) with SRAM. (f) EHPNet.

3.8. In-Domain and Cross-Dataset Evaluation

In order to assess the segmentation stability and generalization performance of EHPNet across plant species and data sources in complex field environments, this research conducted a set of comparative experiments, which includes in-domain evaluation and cross-dataset evaluation. Specifically, the composite dataset was split into two source-specific subsets (ATLDSD and Pl@ntLeaves). Following the ablation setting in Section 3.7, a Baseline model was also included for comparison in both in-domain and cross-dataset evaluations. For in-domain evaluation, both models were trained on the training set of each subset and evaluated on its corresponding test set. For cross-dataset evaluation, the models trained on one subset was directly evaluated on the test set of the other subset. Each subset was independently partitioned into training, validation, and test sets. The results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Performance Comparison of In-domain and Cross-dataset Results. The best results are in bold.

As shown in Table 6, under the in-domain evaluation, the mIoU, PA, PP, PR, and F1 of EHPNet on ATLDSD were 98.32%, 99.30%, 99.08%, 98.66%, and 98.84%, respectively. On Pl@ntLeaves, the corresponding metrics were 98.04%, 99.12%, 98.98%, 98.32%, and 98.65%, respectively. Compared with the Baseline, EHPNet achieved improvements on ATLDSD by 2.48% in mIoU, 0.97% in PA, 0.98% in PP, 2.51% in PR, and 1.72% in F1, and on Pl@ntLeaves by 2.63% in mIoU, 1.10% in PA, 1.12% in PP, 2.88% in PR, and 2.06% in F1. These results indicate that EHPNet maintains stable segmentation performance across different data sources and plant species, and its edge-aware and structure-refinement designs effectively enhance boundary localization and overall generalization in complex field environments.

Under cross-dataset evaluation, compared with the corresponding in-domain results, training on ATLDSD and testing on Pl@ntLeaves led to decreases of 9.12%, 3.47%, 1.39%, 8.46%, and 5.14% in mIoU, PA, PP, PR, and F1 for the Baseline, while the decreases for EHPNet were 7.12%, 2.14%, 1.23%, 6.23%, and 3.82%, respectively. When trained on Pl@ntLeaves and tested on ATLDSD, the Baseline decreased by 6.95%, 2.39%, 3.22%, 3.37%, and 3.25%, while EHPNet decreased by 5.16%, 1.31%, 2.79%, 2.99%, and 2.95%, respectively. Despite this degradation, EHPNet outperforms the Baseline in both cross-dataset evaluations, and the performance drop under cross-dataset testing is smaller than the corresponding drop observed for the Baseline. This demonstrates that EHPNet has improved robustness to domain shift and stronger cross-dataset generalization across different plant species and acquisition conditions.

4. Conclusions

This research proposed EHPNet for plant leaf segmentation in complex field environments. The experimental results show that EHPNet outperforms several state-of-the-art methods on the composite dataset constructed from Pl@ntLeaves and ATLDSD, providing an effective solution for leaf disease segmentation in complex environments. From this research, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- The introduction of HEFM effectively preserves high-frequency edge details during the encoding process, which ensures that the model retains key spatial information. This contribution is particularly crucial for segmenting weak boundaries in complex field environments.

- The proposed SRAM refines edge structure information by incorporating an attention mechanism that selectively enhances important spatial features and suppresses irrelevant background noise. This enables the model to effectively merge global context with local details, which improves segmentation consistency and fine-grained boundary localization.

Although EHPNet significantly improves reconstruction performance, it still relies heavily on large amounts of annotated training data, and its segmentation accuracy deteriorates notably when training samples are scarce. In addition, the current network design introduces relatively high computational costs, which hinders real-time deployment on resource-constrained devices such as UAVs.

To address these limitations, future research will focus on enhancing the generalization ability and reducing dependence on large-scale annotated datasets by exploring strategies such as domain adaptation, semi-supervised learning, and weakly-supervised learning. In addition, efforts will be directed toward optimizing the model architecture to lower computational costs, which enables efficient deployment on mobile devices and supports real-time agricultural monitoring systems.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by J.G., K.C. and J.Z. The first draft of the manuscript was written by J.G. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all reviewers for their valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, K.; Zhong, W.; Li, F. Leaf segmentation and classification with a complicated background using deep learning. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhou, R.; Tjahjadi, T.; Das Choudhury, S.; Ye, Q. A segmentation-guided deep learning framework for leaf counting. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 844522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.; Khan, R.U.; Albattah, W.; Qamar, A.M. End-to-End Semantic Leaf Segmentation Framework for Plants Disease Classification. Complexity 2022, 2022, 1168700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, M.; Mahmoud, A.; Shalaby, A.; El-Baz, A. Automated framework for accurate segmentation of leaf images for plant health assessment. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaivani, S.; Shantharajah, S.; Padma, T. Agricultural leaf blight disease segmentation using indices based histogram intensity segmentation approach. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 9145–9159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Du, K.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, F.; Chu, J.; Sun, Z. A segmentation method for greenhouse vegetable foliar disease spots images using color information and region growing. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 142, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Li, J.; Zeng, J.; Evans, A.; Zhang, L. Segmentation of tomato leaf images based on adaptive clustering number of K-means algorithm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 165, 104962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zeng, W.; Guo, Y.; Yin, S. Edge detection algorithm of plant leaf image based on improved Canny. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Signal Processing (ICSP), Xi’an, China, 9–11 April 2021; pp. 342–345. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Huang, Z.; Yuan, H.; Liang, Y.; Tu, S.; Yang, C. Target Soybean Leaf Segmentation Model Based on Leaf Localization and Guided Segmentation. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhou, S.; Xu, A.; Ye, J.; Yin, J. An approach for plant leaf image segmentation based on YOLOV8 and the improved DEEPLABV3+. Plants 2023, 12, 3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Zhou, L.; Xu, J. Improved mask R-Cnn combined with Otsu preprocessing for rice panicle detection and segmentation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Ma, W.; Lu, J.; Ren, B.; Wang, C.; Wang, J. A novel approach for apple leaf disease image segmentation in complex scenes based on two-stage DeepLabv3+ with adaptive loss. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 204, 107539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, S.; Sun, L.; Hu, X.; Liu, J.; Gong, M.; Liu, H.; Fu, Y. BAF-Net: Bidirectional attention fusion network via CNN and transformers for the pepper leaf segmentation. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1123410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, R.; Zhan, X.; Lu, H.; Guo, W.; Yang, W.; Ding, Y.; Liu, S. Enhancing green fraction estimation in rice and wheat crops: A self-supervised deep learning semantic segmentation approach. Plant Phenomics 2023, 5, 0064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Li, C.T.; Adams, S.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Jiang, R.; He, L.; Hu, Y.; Vernon, M.; Doeven, E.; Webb, L.; et al. Self-supervised leaf segmentation under complex lighting conditions. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 135, 109021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, N.T.; Hoang, D.H.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Tran, M.T.; Le, N. Meganet: Multi-scale edge-guided attention network for weak boundary polyp segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 7985–7994. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; He, T.; Shen, C.; Yan, Y. Decoders matter for semantic segmentation: Data-dependent decoding enables flexible feature aggregation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–17 June 2019; pp. 3126–3135. [Google Scholar]

- Sediqi, K.M.; Lee, H.J. A novel upsampling and context convolution for image semantic segmentation. Sensors 2021, 21, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grand-Brochier, M.; Vacavant, A.; Cerutti, G.; Kurtz, C.; Weber, J.; Tougne, L. Tree leaves extraction in natural images: Comparative study of preprocessing tools and segmentation methods. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2015, 24, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Chao, X. Apple Tree Leaf Disease Segmentation Dataset; Science Data Bank: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, D.P.; Ji, G.P.; Zhou, T.; Chen, G.; Fu, H.; Shen, J.; Shao, L. Pranet: Parallel reverse attention network for polyp segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Lima, Peru, 4–8 October 2020; pp. 263–273. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Tsaftaris, S.A.; Giuffrida, M.V. Gmt: Guided mask transformer for leaf instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 26 February–6 March 2025; pp. 1217–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Kervadec, H.; Bouchtiba, J.; Desrosiers, C.; Granger, E.; Dolz, J.; Ayed, I.B. Boundary loss for highly unbalanced segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Imaging with Deep Learning. PMLR, London, UK, 8–10 July 2019; pp. 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Sun, K.; Cheng, T.; Jiang, B.; Deng, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, D.; Mu, Y.; Tan, M.; Wang, X.; et al. Deep high-resolution representation learning for visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 43, 3349–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.