Featured Application

Mushroom-derived compounds with antiglycation activity have great potential for future use in health and disease prevention. Standardized extracts or purified fractions could be developed into nutraceuticals and functional foods aimed at limiting the accumulation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and reducing complications associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and ageing. Their natural origin, safety, and sustainability make mushrooms suitable candidates for preventive nutrition and healthy ageing strategies. In addition to dietary applications, mushroom bioactives can serve as a template for new drugs or as a complement to current anti-diabetic and anti-ageing therapies. Topical formulations enriched with mushroom-derived antioxidants and antiglycating agents could also be explored for skin health and anti-ageing products. Advances in biotechnology and large-scale cultivation will further support the cost-effective production of these compounds, and promote their integration into the food, medicine and cosmetics industries. Overall, fungal-based antiglycating agents represent a promising natural alternative to synthetic inhibitors that could find wide application in the future.

Abstract

Mushrooms like Inonotus obliquus and Ganoderma lucidum show significant pharmacological promise. This review analyzes fungi as sources of natural inhibitors against Advanced Glycation End-products (AGEs)—key drivers of diabetes and neurodegeneration. We highlight that extracts from Lignosus rhinocerus and Auricularia auricula exhibit antiglycation potency (IC50 as low as 0.001 mg/mL) superior to aminoguanidine. Inhibitory effects are attributed to bioactive fractions including FYGL proteoglycans, uronic acid-rich polysaccharides, and fungal-specific metabolites like ergothioneine. These compounds act through multi-target mechanisms across the glycation cascade: competitive inhibition of Schiff base formation, trapping reactive dicarbonyls (e.g., methylglyoxal), transition metal chelation, and direct scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Furthermore, the review addresses the transition from in vitro potency to in vivo efficacy (RAGE pathway modulation), stability during food processing (UV-B irradiation), and critical safety issues regarding heavy metal bioaccumulation. Mushroom-derived inhibitors represent a sustainable therapeutic alternative to synthetic agents, offering broader protection against glycative stress. This synthesis provides a foundation for developing standardized mushroom-based nutraceuticals for managing AGE-related chronic disorders.

1. Introduction

Many mushrooms have not only been prized as a valuable food for thousands of years, but also have exceptional medicinal properties and have long been used in traditional medicine [1]. Throughout history, mushrooms have played an important role in the treatment of diseases affecting the rural populations of Eastern Europe, with Inonotus obliquus [2], Fomitopsis officinalis [3,4], Piptoporus betulinus [5] and Fomes fomentarius [6,7] being the most commonly used. These species were used in the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases, various cancers, bronchitis, asthma, night sweats, etc. In addition to the current evaluation of the nutritional value of numerous mushrooms, their pharmacological acceptability and properties are also being investigated. They represent a large, still largely untapped source of new, effective pharmaceutical preparations that are important for modern medicine. Recent studies have demonstrated the antitumor [8], antiviral, antibacterial [9], antiparasitic, antifungal, detoxifying, antidiabetic [10], hepatoprotective [11], immunomodulatory [12] and antioxidant [13] effects of mushrooms. In addition to their medicinal effects, mushrooms are also used as novel products such as dietary supplements, functional foods, nutraceuticals, mycopharmaceuticals and designer foods that promote health through the daily consumption of mushrooms [14]. In addition to their nutritional and health benefits, mushrooms are also a sustainable source of food and high-quality substances. Firstly, they are very efficient at utilizing waste products, and unlike traditional crops, which require large amounts of land, water and other resources to grow, they can be grown in a controlled, contained environment using waste products such as sawdust, straw and agricultural by-products. In addition, the growth cycle of mushrooms is short, so they can be grown all year round, and because they grow in a controlled environment, they are less susceptible to weather-related crop failures and traditional production.

Glycation is a non-enzymatic process of binding carbohydrates to proteins, lipids and nucleic acids that leads to the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) [15,16]. These compounds play a key role in the development of numerous chronic diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders and accelerated aging. The identification of compounds that can inhibit the formation of AGEs represents an important therapeutic strategy to mitigate the deleterious effects of these compounds [17]. Such inhibitors offer the potential to prevent or slow the progression of age-related diseases and the debilitating complications associated with diabetes [18]. In the search for such therapeutic agents, natural products have emerged as particularly promising alternatives to synthetic inhibitors, primarily due to their potentially more favorable safety profile and often multiple mechanisms of action. This focus on natural inhibitors addresses existing concerns regarding the side effects of certain synthetic AGE inhibitors. Therefore, the investigation of mushrooms as a rich source of various natural compounds warrants a thorough exploration of their potential to provide safe and effective AGE inhibitors.

This review aims to critically synthesize current evidence on the antiglycation potential of mushroom-derived bioactives, moving beyond simple antioxidant activity to evaluate specific molecular mechanisms such as dicarbonyl trapping and metal chelation. By systematically comparing fungal extracts with synthetic inhibitors and assessing their efficacy across different experimental models (from in vitro to in vivo), this study seeks to identify the most promising fungal candidates and structural motifs, such as uronic acid-rich polysaccharides, for the development of future standardized nutraceuticals.

2. Methodology

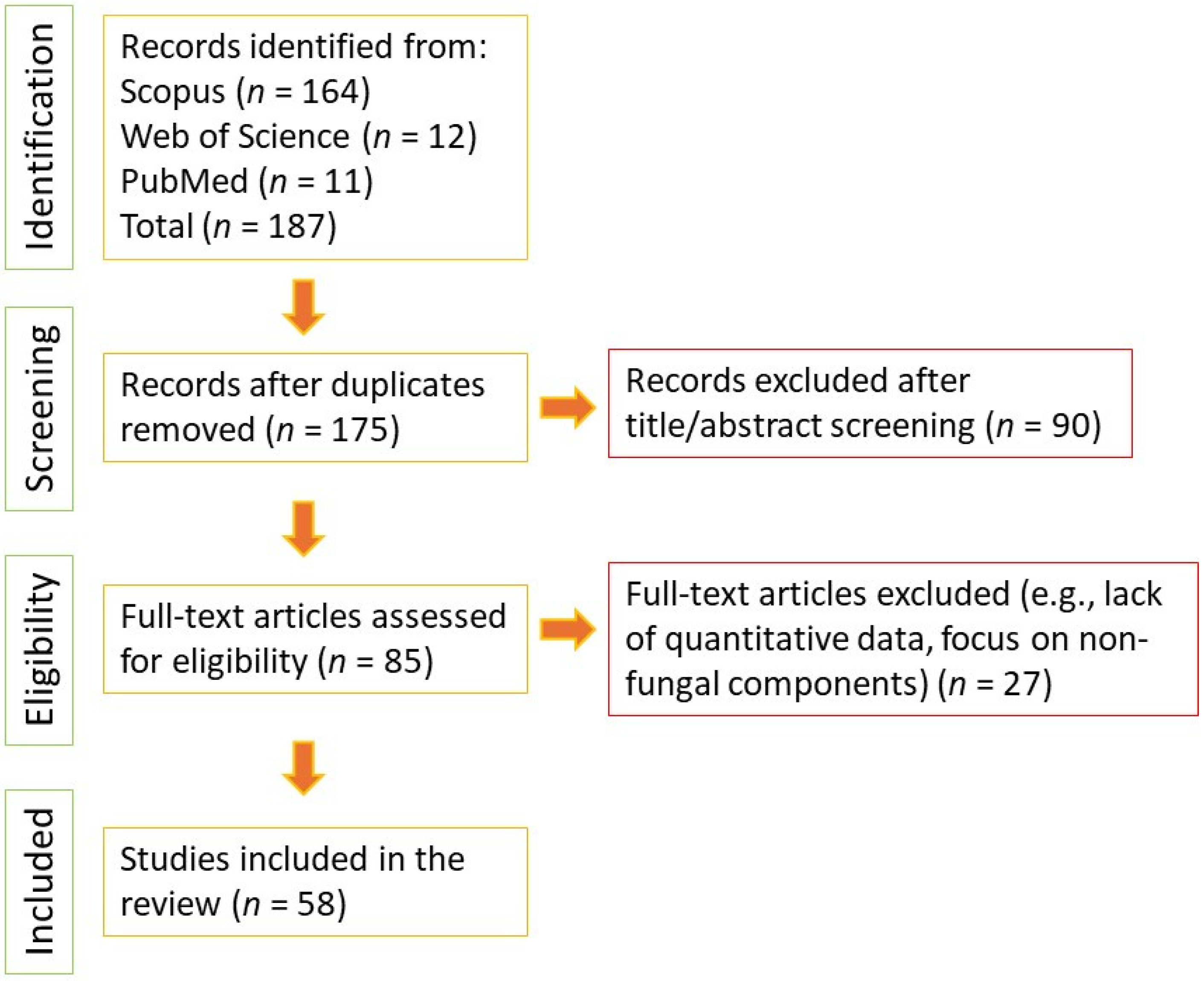

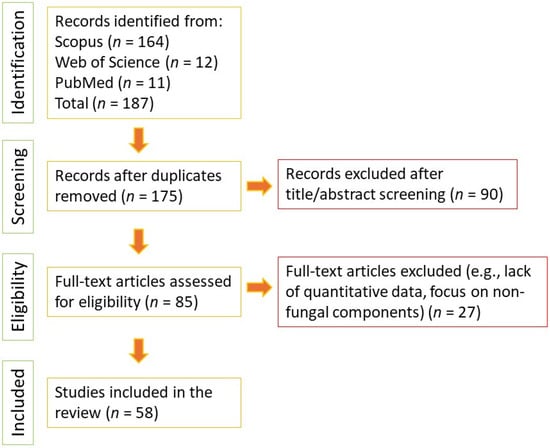

The selection of publications for this review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and a systematic approach to the literature synthesis.

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Sources

A comprehensive literature search was performed across three major electronic databases: Scopus, Web of Science (Core Collection), and PubMed. The search was initially conducted in June 2024 and subsequently updated through December 2025 to identify studies investigating the antiglycation potential of mushrooms. The literature search, study selection, and data extraction were independently performed by three reviewers (F.Š., M.K., and M.Č.S.) to ensure comprehensive coverage and objectivity. Any potential doubts or discrepancies regarding the eligibility of a study were resolved through collective discussion and consensus among all authors. The search strings were tailored for each database as follows:

Scopus: (mushroom AND antiglycation) OR (mushroom AND “ages inhibitor”). The search was refined by applying the ‘Keyword’ field filter, specifically requiring ‘Mushroom’ as an exact keyword to ensure focus on fungal species.

Web of Science: TS = (mushroom* AND (antiglycation OR “AGEs inhibitor*”)).

PubMed: (mushroom*[Title/Abstract] AND (antiglycation[Title/Abstract] OR “AGEs inhibitor”[Title/Abstract])).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they provided primary experimental data on the antiglycation activity of mushroom-derived crude extracts, purified fractions, or isolated fungal metabolites. We included in vitro chemical assays, cellular models, and in vivo animal studies. Review articles were excluded from the primary data synthesis but were used for cross-referencing. Non-English publications and studies focusing solely on higher plants without fungal components were excluded.

2.3. Data Synthesis and Quality Assessment

The initial search yielded a total of 187 records (Scopus: 164; Web of Science: 12; PubMed: 11). After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts for relevance, the remaining papers were subjected to a full-text review. Data were extracted regarding mushroom species, active fractions/compounds, molecular weights (where applicable), experimental models, and quantitative indicators of efficacy. The step-by-step selection process is visually summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search and selection process for mushroom-derived antiglycation compounds.

3. Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs) and Inhibition Strategies

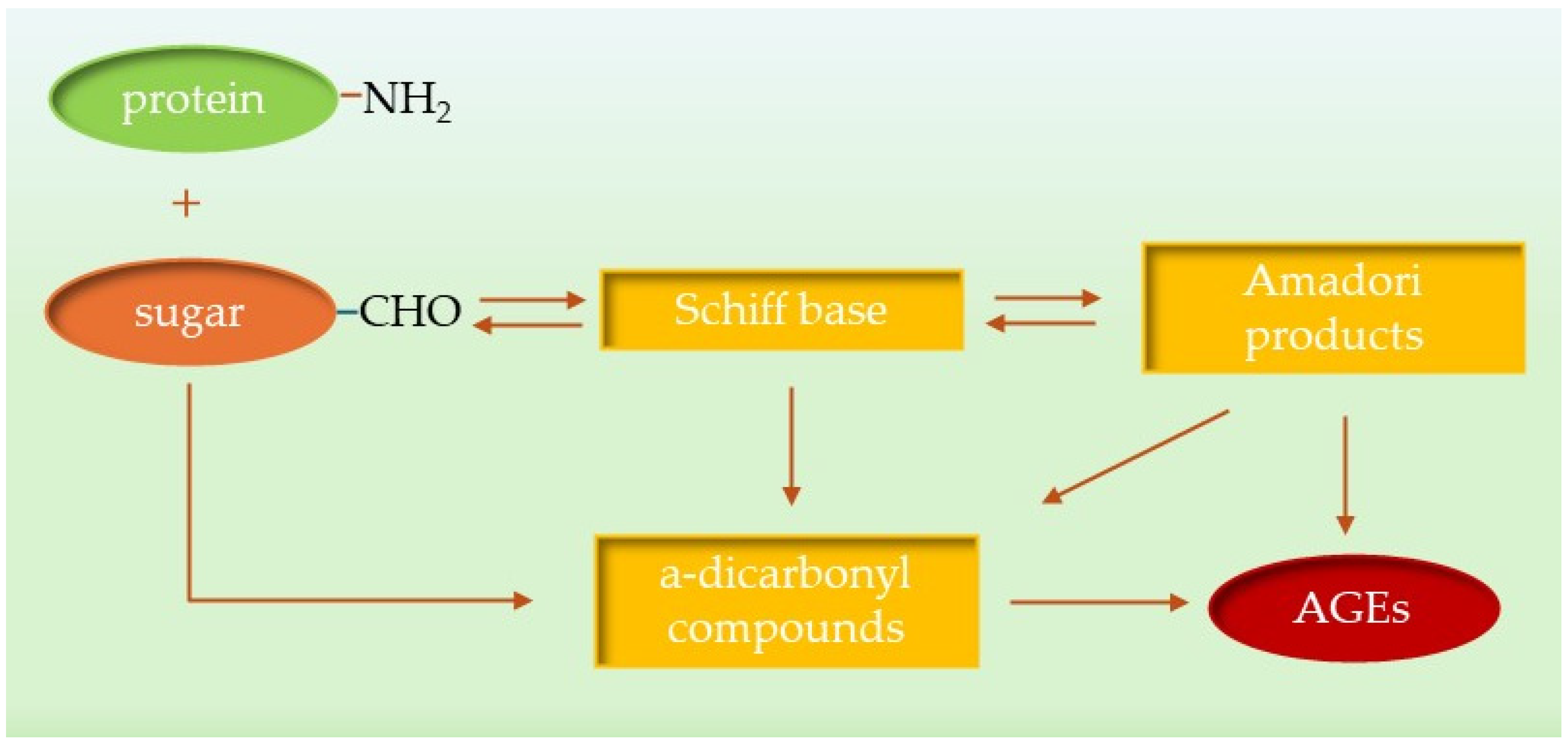

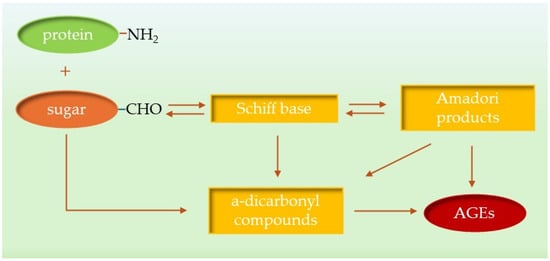

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are a heterogeneous group of compounds formed in non-enzymatic reactions between proteins and reducing sugars or lipids [15,16]. AGEs accumulate in vivo and activate several signaling pathways that are closely associated with the onset and progression of various diseases and pathological conditions, including diabetes, atherosclerosis, neuropathy, nephropathy, wound healing and Alzheimer’s disease. Decades of research have shown that AGEs are the end product of a process that begins under hyperglycemic conditions with a reaction between sugars and their autoxidation products and amino groups of biomolecules. The process of AGE formation can be divided into two basic steps; in the first, carbonyl groups of sugars react reversibly with free amino groups of proteins and nucleic acids, forming unstable Schiff bases (Figure 2). Within a few weeks, they are converted intermolecularly into relatively stable Amadori products, which are referred to as early glycation products. In the second step, a small proportion of the Amadori products is converted directly into AGEs by irreversible oxidation or hydrolysis. The remaining Amadori products can be converted into active α-dicarbonyl compounds such as glyoxal (GO), methylglyoxal (MGO) and 3-deoxyglucosone (3-DG) in dehydration, oxidation or cyclization reactions. Reactive α-dicarbonyl compounds, also known as AGE precursors, bind covalently to proteins to form stable AGEs. As a result, AGEs cause various protein modifications such as intra- and intermolecular linkages and fragmentation, leading to a change in their activity, denaturation, and irreversible damage [19].

Figure 2.

AGE formation.

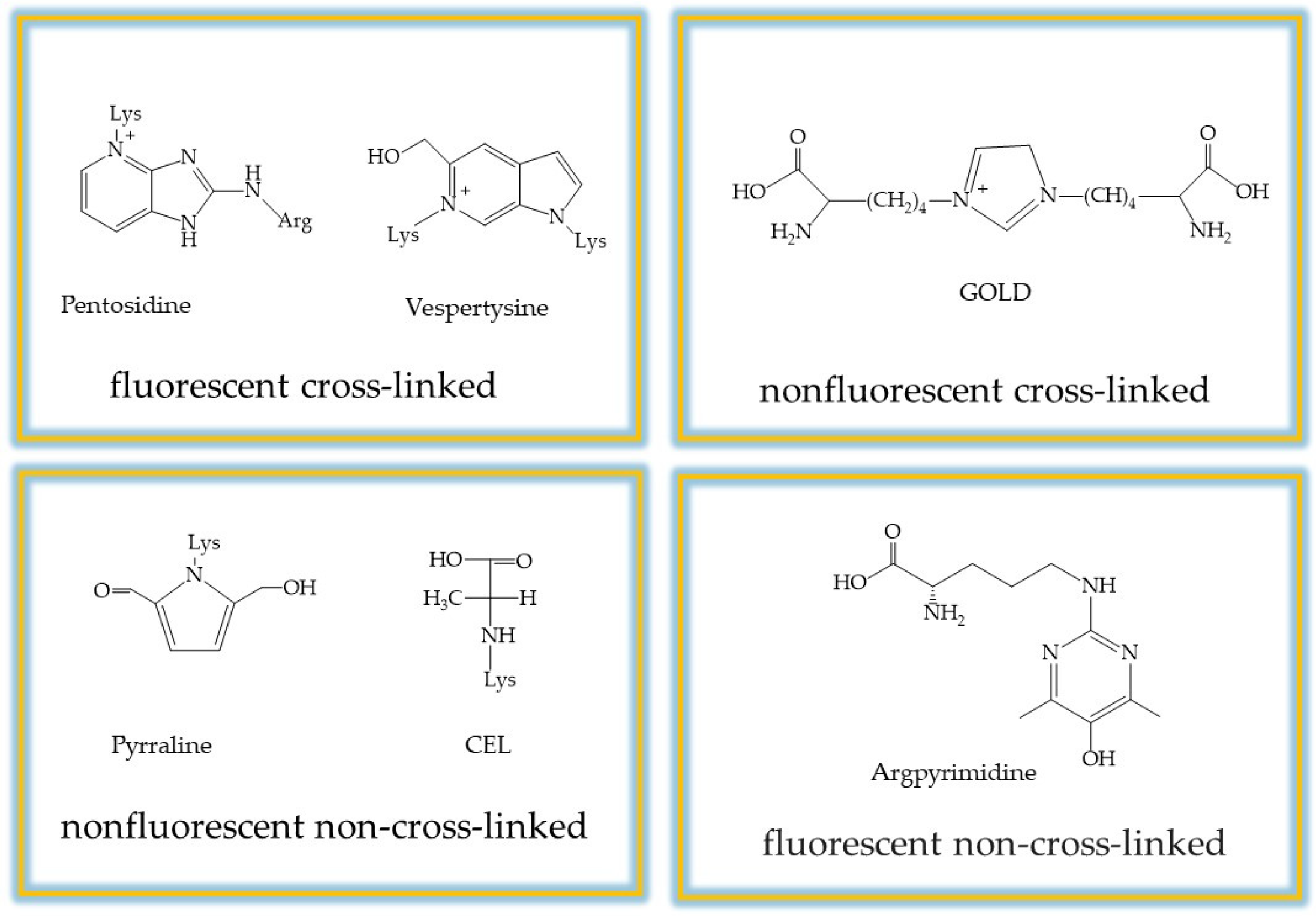

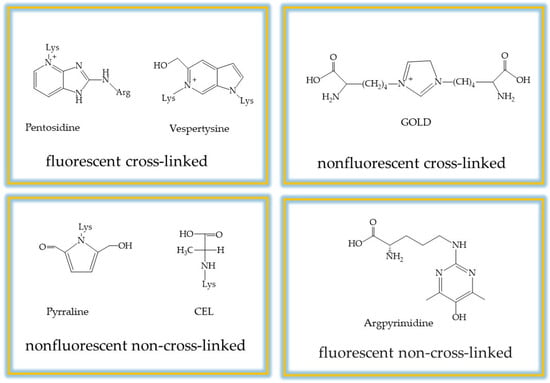

In addition, the autoxidation of glucose, the oxidative cleavage of Schiff bases and lipid peroxidation can produce dicarbonyl compounds that cause the formation of AGEs. Furthermore, glycation has been shown to contribute to oxidative stress as AGEs interact with their receptor (RAGE), leading to increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that accelerate AGE formation. Consequently, under hyperglycemic conditions and in a state of oxidative stress, there is a disruption of the spatial organization of biomolecules, aggregation, and the development of glycation-related diseases. To date, more than 20 types of AGEs have been identified. The classification of these compounds is primarily based on two structural criteria: their ability to emit fluorescence and their capacity to form intermolecular cross-links between proteins. According to these structural properties, AGEs are categorized into four groups: (i) non-cross-linked, non-fluorescent; (ii) cross-linked, non-fluorescent; (iii) non-cross-linked, fluorescent; and (iv) cross-linked, fluorescent. Fluorescent cross-linked AGEs, such as pentosidine, are often used as biomarkers for cumulative glycation damage. In contrast, non-fluorescent cross-linked AGEs, like glucosepane, represent a significant portion of the modifications found in long-lived tissues like collagen. Furthermore, non-cross-linking AGEs, such as Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine (CML) and Nε-(carboxyethyl)lysine (CEL), serve as key indicators of oxidative stress. Understanding these differences provides a good basis for measuring total AGEs [20,21] (Figure 3). In experimental practice, these compounds serve as critical markers: pentosidine is used to assess cumulative damage, while CML is the primary diagnostic indicator for oxidative-mediated glycation.

Figure 3.

Classification of advanced glycation end products according to their chemical structures.

Several strategies have been developed to inhibit the formation of AGEs, targeting different stages of the glycation process [22]. One known mechanism is carbonyl scavenging, in which certain compounds scavenge the reactive carbonyl intermediates such as GO, MGO and 3-DG, which are precursors of AGEs [23]. Examples of synthetic compounds that utilize this mechanism include aminoguanidine and pyridoxamine. Other approaches focus on inhibiting early glycation reactions by inhibiting the initial formation of Schiff bases and Amadori products or by inhibiting the advanced glycation reactions, thereby blocking the conversion of Amadori products into AGEs.

Antioxidant mechanisms also play a critical role in the inhibition of AGEs, as oxidative stress is known to contribute significantly to AGE formation [21]. Natural antioxidants such as vitamin C and quercetin have demonstrated the ability to prevent AGE formation through their free radical scavenging properties [24]. Other strategies include masking lysine residues on proteins that are primary sites for glycation, lowering blood glucose levels to reduce the availability of reactive sugars, and chelation of metal ions, as certain metal ions can catalyze the formation of AGEs [21,25]. Among these, the trapping of reactive dicarbonyl intermediates, such as MGO and GO, represents the most significant molecular target for therapeutic intervention. Consequently, aminoguanidine and quercetin have become key compounds in research, serving as the standard synthetic and natural references for evaluating new AGE inhibitors. Understanding these various mechanisms is fundamental to classifying how mushroom-derived compounds exert their anti-AGE effects and appreciating their potential therapeutic value.

In addition to inhibiting the formation of AGEs, some compounds known as AGE-breakers can directly break the cross-links that have already formed between proteins due to glycation. Examples of such compounds are Alagebrium (ALT-711) [26] and its related analogs. Furthermore, in vitro studies have shown that rosmarinic acid has the potential to break existing AGE cross-links [27]. While the focus of this work is on AGE inhibition, the possibility that certain mushroom-derived compounds also have AGE-breaking activity would represent a significant therapeutic advantage, as they could potentially reverse some of the damage already caused by glycation.

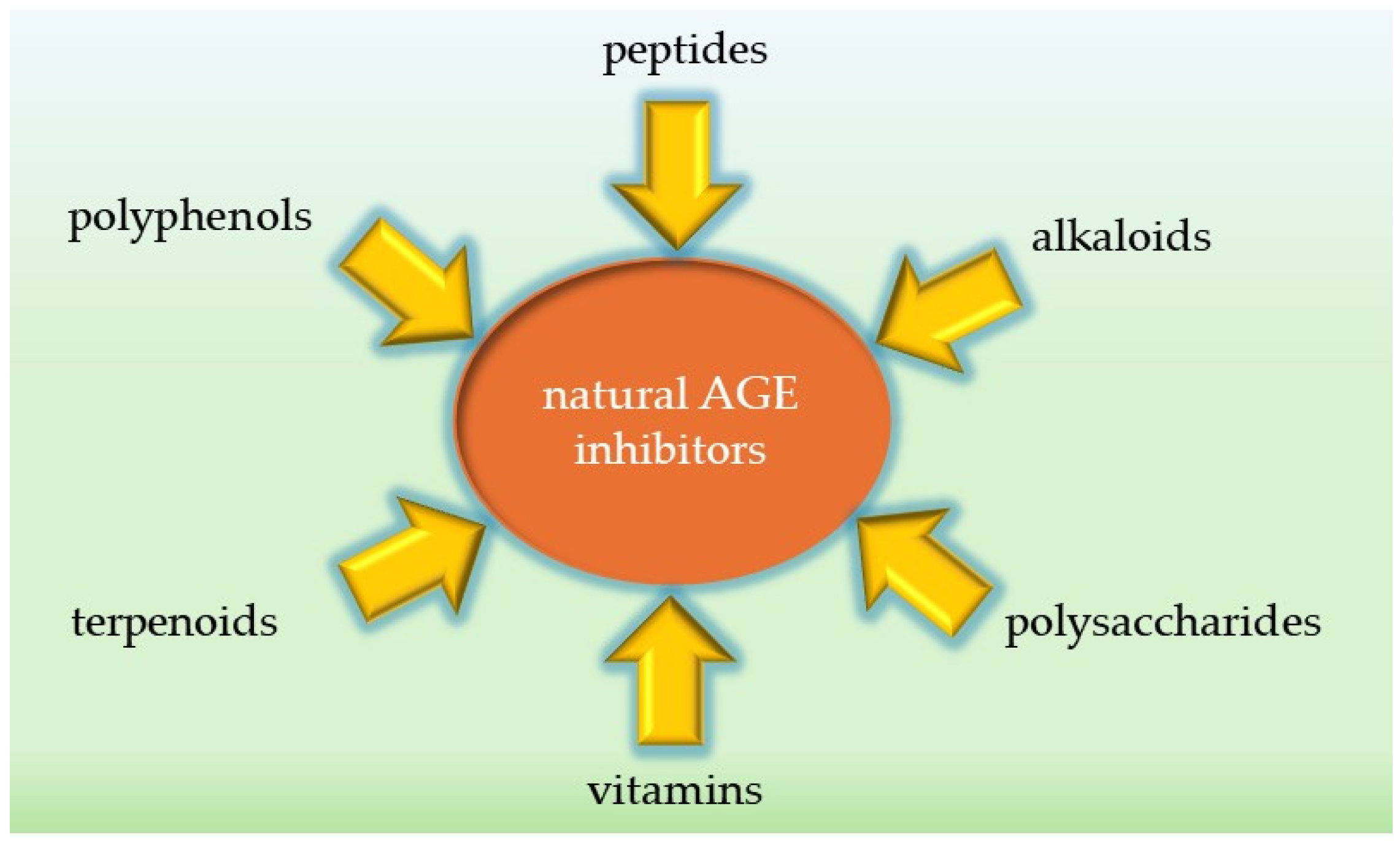

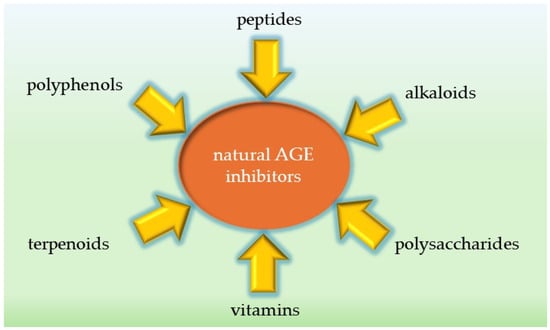

The landscape of AGE inhibitors includes both natural and synthetic compounds. Synthetic inhibitors such as aminoguanidine have demonstrated efficacy in preclinical studies, but their clinical use has been limited by significant side effects [21]. This has led to a growing interest in natural products, including plant extracts and various phytochemicals, as potential sources of safer and equally effective AGE inhibitors with different mechanisms of action [17]. Well-known examples of natural AGE inhibitors include resveratrol [28] and curcumin [29]. Numerous bioactive molecules (Figure 4) prevent or treat various pathological conditions in humans, and many plant extracts, their fractions or pure components have been thoroughly investigated as AGE inhibitors [30,31,32,33,34].

Figure 4.

AGE inhibitors derived from natural sources.

This increasing focus on natural sources emphasizes the need to thoroughly investigate mushrooms, which are known to produce a wide range of bioactive compounds, for their potential to contribute to the development of safe and effective anti-AGE therapies.

4. Mushrooms as a Potential Source of Natural AGE Inhibitors

Mushrooms represent a rich and largely unexploited reservoir of various bioactive metabolites. Beyond common compound classes like phenolics and flavonoids, mushrooms synthesize unique metabolites that are essential for pharmacological standardization. These include sulfur-containing amino acids such as ergothioneine, fungal-specific β-glucans, and genus-specific triterpenoids like ganoderic acids. These compounds comprise a broad spectrum of chemical classes such as polysaccharides, proteins, peptides, terpenoids, alkaloids, vitamins, and minerals [35]. These fungal-specific markers are responsible for a broad spectrum of pharmacological activities, including significant antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, anticancer, and immunomodulatory effects. Ergothioneine, for instance, is a primary marker of interest due to its unique transport mechanism in humans (OCTN1) and its potent ability to protect proteins from glycative stress. The sheer diversity of specialized molecules present in mushrooms greatly increases the likelihood of discovering novel molecules with potent antiglycation properties. Consequently, the systematic screening of different fungal species and their extracts, standardized by these unique metabolites, represents a promising and largely unexplored opportunity for the identification of natural AGE inhibitors.

Numerous research studies have documented the significant antioxidant properties of numerous fungal compounds, particularly polysaccharides and phenolic compounds [35]. Since oxidative stress is a critical factor in both the formation of AGEs and the mediation of their deleterious effects, the inherent antioxidant capacity of mushrooms strongly suggests their potential to mitigate the formation of AGEs and their downstream consequences. By effectively scavenging free radicals and reducing overall oxidative stress, mushroom-derived antioxidants may indirectly inhibit the glycation process [22]. This well-established link between antioxidant activity and AGE inhibition provides a compelling rationale for focusing research efforts on mushrooms as a valuable source of anti-AGE compounds.

In addition, many species of mushrooms have long been used in traditional medicine to treat conditions such as diabetes and various age-related ailments [36]. This ethnomedicinal tradition provides valuable initial evidence of their potential efficacy in the treatment of diseases in which the accumulation of AGEs is an important factor. The traditional use of these mushrooms for related health problems can serve as a guide for modern scientific research by highlighting specific species that are particularly rich in anti-AGE compounds. This intersection of traditional knowledge and modern scientific research offers a promising avenue for the discovery of new therapeutic agents.

Recent research has further expanded the potential of mushrooms by demonstrating that combinations of different mushroom species can exhibit synergistic effects, enhancing their overall anti-glycation and antioxidant capacity beyond what would be expected from the simple sum of their individual activities [37]. This synergy is particularly potent at lower concentrations of mushroom extracts, highlighting the complex and beneficial interactions between their diverse bioactive compounds, such as phenolics, tannins, and flavonoids. This finding underscores the advantage of consuming a variety of mushrooms or using multi-mushroom formulations to maximize health benefits.

5. Specific Mushroom Species and Their AGE-Inhibiting Properties

Several species of fungi have been investigated for their potential to inhibit the formation of AGEs and promising results have been obtained (Table 1). The study of Lignosus rhinocerus (tiger’s milk mushroom) has shown that a medium molecular weight (MMW) fraction obtained from the sclerotia of Lignosus rhinocerus has significant antiglycation activity [38]. This fraction was found to specifically inhibit the formation of the major AGEs, namely Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine (CML) and pentosidine. It is noteworthy that the IC50 value of this MMW fraction for the inhibition of AGEs is remarkably low at 0.001 mg/mL, almost 520 times lower than that of the positive control, aminoguanidine hydrochloride. The observed anti-glycation activity can be attributed, at least in part, to the potent free radical scavenging activity of superoxide anions of the MMW fraction. Furthermore, the identification of genes encoding glyoxalase I in L. rhinocerus suggests an additional mechanism by which this fungus may inhibit the formation of AGEs, namely by detoxifying methylglyoxal, an important precursor of various AGEs. However, it is important to note that the presence of these genes in the fungal genome does not automatically guarantee enzymatic activity in the final extract. The stability of such enzymes is highly dependent on the processing methods used; traditional extraction involving heat or certain solvents can denature proteins, potentially inactivating the glyoxalase system. Therefore, the anti-AGE efficacy of processed mushroom products may rely more on heat-stable secondary metabolites unless specific cold-extraction or stabilization techniques are employed. These results make L. rhinocerus a particularly promising source of potent AGE inhibitors with activity against specific AGE types, possibly acting via both antioxidant and carbonyl detoxification pathways.

Polysaccharides isolated from the mycelium of Ganoderma capense, a species that is widely used, especially in Asia, have shown both antiglycation and antiradical activities in in vitro studies [39]. In particular, the GC70 fraction, consisting of polysaccharides obtained by 70% ethanol precipitation from the mycelium of G. capense, showed significant potential to inhibit AGE formation in a manner that was both time- and dose-dependent. In addition, these polysaccharides showed concentration-dependent scavenging abilities against both DPPH and hydroxyl radicals. The dual activity of G. capense polysaccharides, namely direct inhibition of AGE formation and free radical scavenging, is particularly beneficial given the intertwining of oxidative stress and glycation in disease processes.

Ganoderma lucidum (reishi mushroom) has yielded an anti-oxidative proteoglycan named FYGL (a hyper-branched proteoglycan with a molecular weight of approximately 2.6 × 105 Da) that exhibits significant anti-glycation activity [40]. This compound inhibits glycation at every stage of the process and suppresses glycoxidation, likely due to its strong antioxidative capacity and its ability to form complexes with target proteins like bovine serum albumin. In vivo studies have confirmed that FYGL can alleviate postprandial hyperglycemia in diabetic mice and reduce AGE accumulation and vascular injury in diabetic rats. FYGL also demonstrates inhibitory effects on α-glucosidase activity, which helps slow carbohydrate metabolism and reduce postprandial hyperglycemia. This dual action against both glycation and glucose absorption makes FYGL a particularly promising compound for diabetes management.

Research indicates that polysaccharide AAP-2S extracted from Auricularia auricula (wood ear fungus) significantly inhibits the formation of AGEs during both short- and long-term glycosylation processes [41]. This polysaccharide has been shown to reduce oxidative damage to proteins and preserve important protein sulfhydryl groups. In addition, it reduces the carbonylation of proteins and prevents structural changes in proteins caused by glycation. Furthermore, AAP-2S also exhibits metal chelating capabilities. The mechanism of action may involve modulation of the RAGE/TGF-β/NOX4 pathway, possibly attenuating glycosylation and improving cell fibrosis. In addition, hydrolysates of polysaccharides from Auricularia auricula-judae also improve glucose absorption in HepG2 cells and extend the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans under conditions of high sugar stress [42].

Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom) is known to contain various phenolic compounds that have been reported to have an antiglycative function. A methanolic extract of Pleurotus ostreatus was found to have high phenolic and flavonoid content and excellent antioxidant capacity [43]. Fraction F4 of this extract showed strong in vitro inhibition of fructose-mediated hemoglobin as well as BSA protein glycation. In addition, this fraction showed fructosamine and protein carbonylation inhibition and reduced protein aggregation and fluorescence intensity associated with AGEs.

A polyphenol-rich decoction (CPD) of Inonotus obliquus (Chaga mushroom) has been shown to inhibit glycation of albumin and collagen gel three to four times more effectively than the known AGE inhibitor aminoguanidine [44]. In addition, CPD exhibits significant intracellular antioxidant effects. Chaga mushroom is known to contain high levels of various antioxidants as well as proteins, minerals, fiber and vitamins [45].

Polysaccharides obtained from water extracts of Pholiota nameko, nutritious mushroom originating in Japan, can significantly inhibit the production of AGEs in vitro and increase the reduced cell viability and growth rate caused by glycation stress [46]. The antiglycation effect originates from their excellent antioxidant activity and ROS scavenging ability.

Extracts from the edible mushroom Lactarius deterrimus used separately and in combination of chestnut Castanea sativa extracts inhibited protein glycation and AGE formation in vitro, and reduced non-enzymatic glycosylation in diabetic rats in vivo through inhibition of CML-mediated RAGE/NF-κB activation and enzymatic O-GlcNAcylation in liver and kidney tissues [47].

Phellinus linteus has shown strong potential as a natural inhibitor of AGEs due to the presence of various bioactive compounds [48]. Among its phenolic constituents, one compound from the fruiting body has demonstrated exceptional efficacy in inhibiting protein cross-linking at the final stage of glycation, performing even better than aminoguanidine. Additionally, the mushroom contains potent antioxidants such as hispidin and ergothioneine, which help mitigate oxidative stress—a key driver of AGE formation—and thus indirectly reduce AGE accumulation. Furthermore, polysaccharides extracted from P. linteus have been found to lower blood glucose levels and improve insulin sensitivity in diabetic models. This glycemic control reduces the availability of sugars that participate in glycation reactions, contributing further to the inhibition of AGE formation [49].

Ergothioneine is an unusual amino acid derivative found in various mushrooms that has been patented for use as an anti-glycation agent [50]. This compound acts as a powerful antioxidant and may protect proteins from glycation damage through its free radical scavenging properties. Although the patent focuses on topical application for reducing skin protein glycation, ergothioneine’s mechanism suggests potential benefits for systemic glycation processes as well.

A study by Sun et al. (2016) presents a detailed investigation of the antiglycation properties of two novel polysaccharide fractions (BSP-1b and BSP-2b) purified from the mushroom Boletus snicus [51]. The researchers thoroughly characterized the polysaccharides, finding that BSP-2b had a higher molecular weight (128.74 kDa) and a more complex monosaccharide composition, including a significant uronic acid content, compared to BSP-1b (59.21 kDa). In a bovine serum albumin (BSA)-glucose glycation model, both fractions showed significant, dose-dependent inhibition of AGE formation at all stages of the glycation process (initial, intermediate, and final). Notably, BSP-2b consistently exhibited stronger antiglycation activity than BSP-1b. The authors attributed this greater efficacy to the higher molecular weight and increased uronic acid content of BSP-2b, suggesting that these structural features are critical for its potent activity. This study identifies Boletus snicus as a promising source of antiglycative agents and highlights the importance of polysaccharide structure in determining bioactivity.

A crucial aspect for the practical application of mushroom-based AGE inhibitors is their stability during processing. A study on Agaricus bisporus and Pleurotus ostreatus demonstrated that UV-B irradiation, a common method to enhance Vitamin D2 content, significantly reduced the overall antioxidant capacity of the mushrooms. However, the antiglycation activity of both the water-soluble and ethanol-insoluble fractions was fully retained after irradiation [52]. This finding underscores that the bioactive compounds responsible for inhibiting AGE formation in these commercially vital species are remarkably stable, highlighting their potential for use in processed functional foods and nutraceuticals without losing efficacy.

Table 1.

Antiglycation activities of mushroom species.

Table 1.

Antiglycation activities of mushroom species.

| Mushroom Species | Active Fraction/ Compound(s) | Proposed Mechanism(s) | Experimental Model | Activity (Outcome) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lignosus rhinocerus | Medium-molecular- weight (MMW sclerotial fraction, 30–100 kDa) | Inhibition of CML and pentosidine, superoxide anion radical scavenging, glyoxalase I activity | In vitro: HSA-glucose BSA-MGO | IC50 = 0.001 mg/mL, 520-fold lower than aminoguanidine (positive control) | [38] |

| Ganoderma capense | Polysaccharides (GC70 fraction, polysaccharides obtained by 70% ethanol precipitation from mycelium) | Inhibition of AGE formation, DPPH and hydroxyl radical scavenging | In vitro: BSA-glucose | 30.1% inhibition at 0.5 mg/mL | [39] |

| Ganoderma lucidum | FYGL proteoglycan (highly branched anti-oxidative proteoglycan, MW ~260 kDa, isolated from fruiting bodies) | Multi-stage glycation inhibition; suppression of glycoxidation; α-glucosidase inhibition; protein-FYGL complex formation | In vitro: BSA-fructose, BSA-MGO In vivo: db/db mice, diabetic rats | Reduced postprandial hyperglycemia, AGE accumulation, and vascular injury. | [40] |

| Auricularia auricula | AAP-2S (acidic water-soluble polysaccharide fraction, primarily composed of glucose, glucuronic acid, and mannose) AAPs and AAPs-F (degraded polysaccharides via acid hydrolysis) | RAGE/TGF-β/NOX4 modulation; metal chelation; protection of protein thiols Inhibition of AGE formation; enhancement of glucose metabolism; stress resistance | In vitro: BSA-fructose Cellular: CML-induced HK-2 cells. In vitro: BSA-glucose Cellular: HepG2 cells In vivo: C. elegans | Mitigated cell fibrosis (reduced FN and α-SMA expression); preserved protein sulfhydryl groups; inhibited AGE formation. In vitro: significant AGE inhibition (p < 0.05) Cellular: +24.4% glucose uptake In vivo: +32.9% lifespan extension | [41,42] |

| Pleurotus ostreatus | Methanolic extract (Fraction F4), phenolic and flavonoid compounds | Antioxidant scavenging; inhibition of protein carbonylation and aggregation | In vitro: Fructose-induced hemoglobin glycation mode | F4: 58.8% inhibition of HbA1c; 64.3% reduction in fructosamine; 51.4% reduction in protein carbonyls | [43] |

| Inonotus obliquus | Polyphenol decoction (CPD) | ROS scavenging; electrostatic protection of proteins; inhibition of collagenase overexpression | In vitro: Albumin and collagen gel glycation Cellular: UV-A irradiated NHDF cells | Albumin: IC50 = 72.5 μg/mL; collagen: IC50 = 126 μg/mL; Cellular: 50% ROS reduction at 190 μg/mL | [44] |

| Pholiota nameko | PNPs (Polysaccharides: PNP-40, 60, 80; rich in βbeta-glucan) | MGO-trapping; metal ion chelation; inhibition of Amadori products; ROS scavenging | In vitro: BSA-MGO Cellular: MGO-induced damage in Hs68 (fibroblasts) | PNP-80: 97.7% Fe2+ chelation; significant reduction in protein carbonyls and ε-NH2 loss; enhanced survival of Hs68 cells | [46] |

| Lactarius deterrimus | 50% methanolic extract | Reduction in the RAGE/NF-κB activation, reduction in enzymatic O-GlcNAcylation, reduction in oxidative stress | In vitro: BSA/Protein glycation assay In vivo: STZ-induced diabetic rats | In vitro: significant inhibition of fructosamine and total AGE formation. In vivo: Reduced AST, ALT and BUN levels; protected pancreatic islets | [47] |

| Phellinus linteus | Ethyl acetate fraction; interfungin A, davallialactone, inoscavin A | Multistage inhibition: early (HbA1c), middle (MGO-trapping), and last stage (protein cross-linking) | In vitro: Hb-delta-gluconolactone (early), BSA-MGO (middle), GKM-ribose (last) | Interfungin A: inhibition at all stages; more effective than aminoguanidine in preventing protein cross-linking, inoscavin A: IC50 = 158.66 μM (MG-trapping) | [48,49] |

| Various mushrooms | Ergothioneine | Inhibition of Schiff’s base rearrangement; free-radical scavenging; protection of dermal collagen | In vitro: BSA-D-ribose | Dose-dependent inhibition: 1 mM = 28.6% inhibition; 5 mM = 42.9% inhibition of glycation fluorescence | [50] |

| Boletus sinicus | Polysaccharides: BSP-1b (59 kDa) and BSP-2b (128 kDa; high uronic acid) | Inhibition of Amadori products; scavenging of dicarbonyl compounds; inhibition of AGE fluorescence | In vitro: BSA-glucose | BSP-2b: Stronger activity than BSP-1b and AG (at >100 μg/mL); 45.21% inhibition of total AGEs at 250 μg/mL | [51] |

| Agaricus bisporus, Pleurotus ostreatus | Ethanol-insoluble fraction | Metal chelation and carbonyl-trapping (inferred); maintenance of redox stability | In vitro: BSA-fructose | High resistance to UV: antiglycation activity remained stable despite UV-B irradiation; A. bisporus fraction showed 555 mg AG/g potency | [52] |

| A. bisporus, L. edodes, P. ostreatus, P. eryngii, F. velutipes | Crude extracts (rich in phenolics, tannins, and polysaccharides) | Direct radical scavenging; dicarbonyl trapping; metal chelation | In vitro: BSA-glucose and BSA-fructose models | Synergistic effects at low doses (e.g., A. bisporus + F. velutipes); antagonistic at high doses due to pro-oxidative shifts | [37] |

Beyond the activity of individual species, the strategic combination of common edible mushrooms has emerged as a promising approach to boost anti-glycation effects. A comprehensive study evaluating pairwise combinations of Agaricus bisporus, Lentinula edodes, Flammulina velutipes, Pleurotus ostreatus, and Pleurotus eryngii revealed that specific mixtures can produce synergistic interactions [37]. Interestingly, the study also found that these synergistic effects were most pronounced at lower extract concentrations, while higher concentrations often led to antagonistic interactions. This suggests that the balance and ratio of bioactive compounds are critical for achieving optimal functional benefits. The anti-glycation activity of these mushroom combinations showed a significant positive correlation with their total phenolic content and radical scavenging capacity (DPPH assay), reinforcing the role of polyphenols as primary agents against AGE formation.

6. Mechanisms of Action of Mushroom-Derived AGE Inhibitors

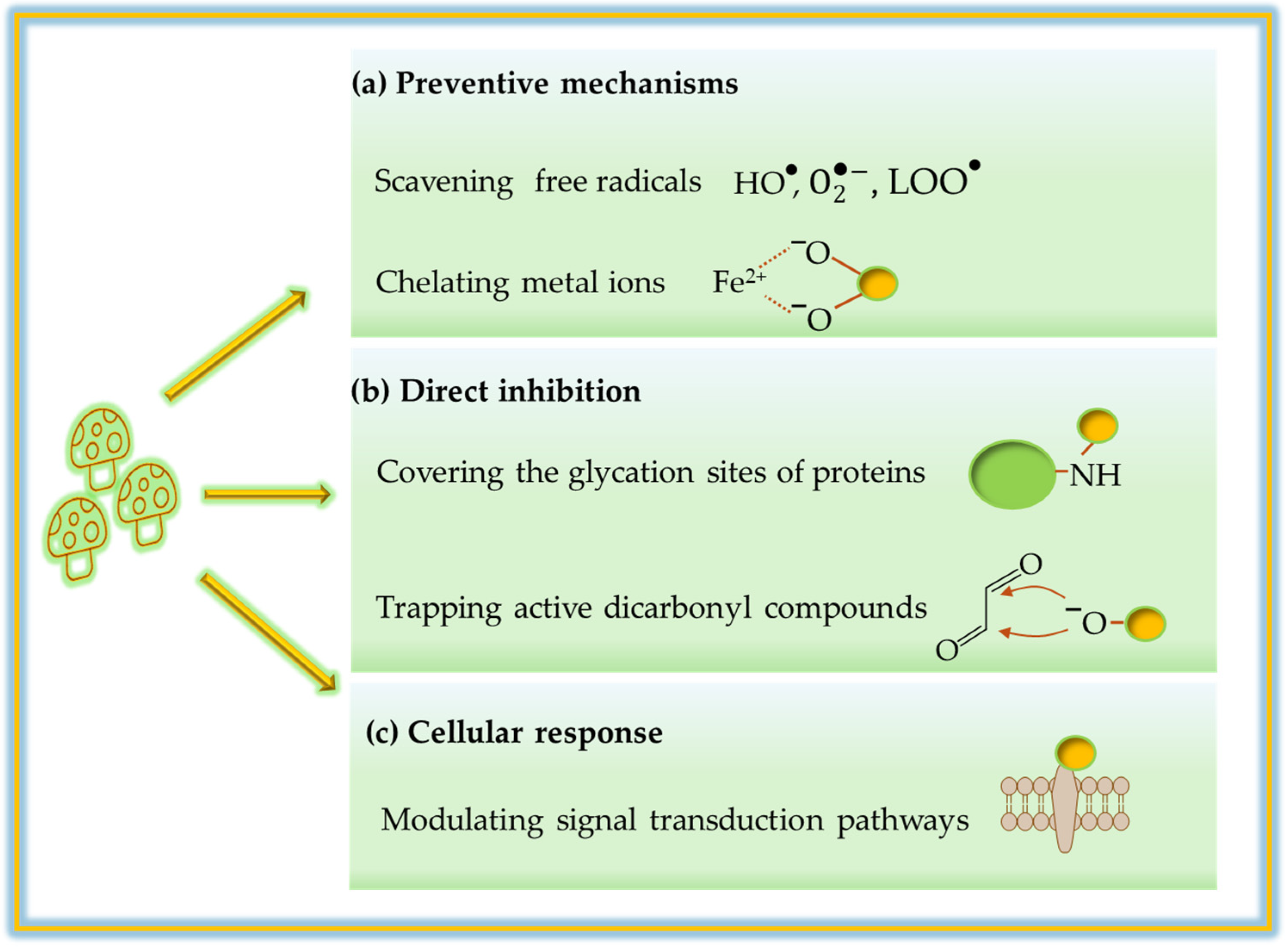

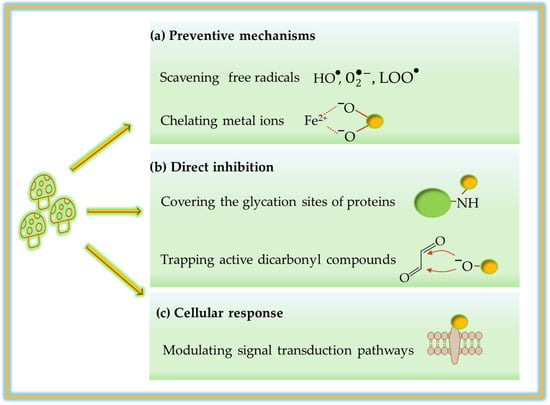

The fungal species identified in the Section 5 exert their AGE-inhibitory effects through a variety of mechanisms that reflect the different chemical nature of their bioactive compounds (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Proposed mechanisms of action of mushroom-derived AGE inhibitors: (a) preventive antioxidant mechanisms including the scavenging of specific reactive species and chelation of metal ions; (b) direct inhibition pathways by covering protein glycation sites and trapping reactive dicarbonyl compounds; (c) modulation of downstream cellular signaling and transduction pathways.

6.1. Antioxidant Activity

A primary mechanism by which mushrooms combat AGE formation is the mitigation of oxidative stress, a critical driver of both the formation and deleterious effects of AGEs. It is crucial to distinguish between direct radical scavenging and indirect antioxidant mechanisms, which are often intertwined in complex fungal extracts.

Direct radical scavenging by phenolics: The high phenolic and flavonoid content in species like Pleurotus ostreatus and Inonotus obliquus contributes to excellent direct antioxidant capacity by donating hydrogen atoms or electrons to neutralize ROS. This includes the highly aggressive hydroxyl radical (HO•), the superoxide anion (), and lipid peroxyl radicals (LOO•), which participate in distinct chemical pathways of protein and lipid oxidation [43,44]. For instance, while HO• triggers non-specific damage, LOO• is a key driver of lipid peroxidation, which subsequently generates reactive dicarbonyl precursors of AGEs. This antioxidant protection typically follows the Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT) mechanism, where the bioactive inhibitor—represented as a polysaccharide (PS-OH) or a phenolic compound (Ar-OH)—reacts directly with a free radical (R•):

PS-OH + R• ⟶ PS-O• + R-H

The resulting macro-radical (PS-O•) is chemically stabilized by the electron-delocalizing properties of the carbohydrate or phenolic ring, preventing further oxidative damage to biomolecules.

The antioxidant role of polysaccharides and proteins: The reported radical (DPPH, HO•) scavenging by polysaccharide fractions (e.g., from Ganoderma capense [39] or Pholiota nameko [46]) requires mechanistic clarification. While pure polysaccharides may exhibit moderate direct activity, their significant effect in biological systems often stems from associated compounds and indirect mechanisms:

- Metal Chelation: Many fungal polysaccharides, particularly those with high uronic acid content (see Section 6.7), can chelate transition metal ions (Fe2+, Cu2+), thereby inhibiting metal-catalyzed Fenton reactions that generate highly reactive HO•. The carboxyl groups of uronic acids act as ligands, sequestering metals into stable coordination complexes:

2(PS-COO−) + Fe2+ ⟶ PS-COO-Fe-OOC-PS

This reduction in oxidative stress indirectly decelerates glycation.

- Bound bioactives: Crude polysaccharide fractions often contain associated phenolic compounds or peptides that contribute directly to radical scavenging activity measured in assays.

- Enzymatic detoxification pathways: A key protein-based antioxidant mechanism is the enzymatic detoxification of carbonyl precursors. For instance, the identification of glyoxalase I genes in Lignosus rhinocerus points to a capacity to metabolize MGO—a highly reactive dicarbonyl and potent AGE precursor—into harmless D-lactate via the glutathione-dependent glyoxalase pathway [38]. This represents a crucial, indirect anti-glycation strategy.

6.2. Scavenging of Carbonyl

Beyond managing ROS, a potent anti-AGE strategy is the direct trapping or sequestration of RCS like GO, MGO, and 3-DG, which are central intermediates in AGE formation. The principle of chemical trapping mechanisms involves a nucleophilic attack on the electrophilic carbonyl carbons of RCS. Bioactive compounds with nucleophilic centers, such as amino groups in arginine-rich peptides or catechol structures in polyphenols, can form stable adducts with MGO/GO, thereby preventing their reaction with protein amino groups [38]. This sequestration occurs via a nucleophilic addition where the inhibitor’s nucleophilic center (Nu) attacks the dicarbonyl:

R-CO-CHO + Nu ⟶ R-CO-CH(OH)-Nu ⟶ stable adduct

This reaction yields stable, non-reactive adducts, effectively reducing the pool of reactive carbonyl species available for AGE formation and preventing the subsequent cross-linking of proteins. This chemical sequestration is a crucial defense, especially in the intermediate stages of the glycation cascade.

6.3. Interfering with the Glycation Process

Compounds derived from fungi can interfere with the glycation cascade at various points, acting as multi-stage inhibitors. At the early stage, these compounds can compete with reducing sugars for free amino groups (e.g., lysine, arginine) on proteins, thus preventing the initial formation of Schiff bases. For example, the polyphenol decoction from Inonotus obliquus may effectively block these initial binding sites on albumin and collagen [44]. In the specific case of hemoglobin glycation, it is essential to note that fungal bioactives act as preventive kinetic inhibitors. Rather than modifying the final glycated product (HbA1c), they interfere with the initial nucleophilic attack of glucose on the N-terminal valine of the β-chain of hemoglobin. Specifically, these compounds slow down the rate-limiting Amadori rearrangement, thereby reducing the steady-state concentration of the unstable aldimine (Schiff base) precursor before it can transition into stable HbA1c. Moving to the intermediate stage, fungal extracts provide intervention by scavenging reactive dicarbonyls (as described in Section 6.2) or chelating transition metal ions that catalyze sugar autoxidation, thereby inhibiting the formation of advanced glycation intermediates. Specifically, by trapping dicarbonyls like MGO, mushroom metabolites prevent the irreversible cross-linking that characterizes the transition from early to late glycation stages. Polysaccharides from Auricularia auricula have been shown to mitigate these intermediate oxidative processes through robust metal chelation and ROS scavenging [41]. Finally, at the late stage, fungal compounds offer structural protection; specifically, the proteoglycan FYGL from Ganoderma lucidum may form complexes with target proteins, sterically protecting vulnerable amino acid residues and suppressing subsequent glycoxidation and cross-linking [40]. Similarly, the inhibition of protein carbonyl formation and aggregation by Pleurotus ostreatus extracts further underscores the efficacy of mushroom-derived bioactives in intervening at these advanced stages of the glycation process [43]. This multi-stage intervention is crucial for reducing the accumulation of permanent AGE-mediated damage in long-lived proteins.

6.4. Modulation of Signal Transduction Pathways

Beyond direct chemical interference with the glycation process, some mushroom-derived compounds exert potent anti-AGE effects by modulating key cellular signaling pathways activated by these products, offering a vital downstream therapeutic strategy. A primary target in this approach is the inhibition of RAGE (Receptor for AGEs) activation. By reducing the formation of specific AGE ligands, such as carboxymethyl-lysine (CML)—as demonstrated with Lactarius deterrimus extracts [47]—fungal compounds effectively prevent the binding and subsequent activation of this receptor. This intervention is crucial as it disrupts various deleterious signaling cascades triggered by the AGE-RAGE axis. For instance, polysaccharides from Auricularia auricula have been shown to modulate the RAGE/TGF-β/NOX4 pathway, thereby attenuating oxidative stress and profibrotic responses [41]. Similarly, the ability of fungal bioactives to suppress CML-induced RAGE/NF-κB pathway activation results in a significant reduction in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, highlighting the broader anti-inflammatory potential of these mushroom extracts [47].

6.5. Metal-Ion Chelation

The chelation of transition metal ions, such as Fe2+ and Cu2+, represents a significant and highly effective anti-glycation mechanism in mushroom-derived bioactives. As documented for Auricularia auricula polysaccharides [41], this sequestration process is primarily driven by the presence of acidic functional groups, notably the carboxyl groups of uronic acids, which act as ligands to form stable coordination complexes with metals. By effectively “masking” these catalytic ions, the extracts inhibit metal-catalyzed oxidation reactions, such as the Fenton reaction, which is a major source of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals. This inhibition is doubly beneficial: it reduces the immediate oxidative stress within the cellular environment and simultaneously slows the oxidation of Amadori products into advanced glycation end-products (AGEs). Therefore, by removing these essential catalysts, mushrooms reduce the rate of both protein glycoxidation and the subsequent formation of reactive dicarbonyl intermediates.

6.6. Synergistic Interactions

The beneficial effects of mushroom-derived compounds are often significantly amplified through synergistic interactions that occur when different chemical classes, such as polysaccharides, phenolics, and proteins, coexist within an extract. These interactions are not merely additive; rather, the combined biological effect often exceeds the sum of the individual components’ activities due to their multi-target engagement [37]. Specifically, these constituents attack distinct molecular targets within the glycation cascade: while phenolic fractions (e.g., from Flammulina velutipes) primarily focus on direct radical scavenging and the chemical trapping of reactive dicarbonyl intermediates, the associated polysaccharide fractions provide a complementary defense by chelating transition metal catalysts and sterically shielding protein amino groups from sugar attachment. This simultaneous intervention at different stages explains the superior efficacy of crude extracts compared to single-target synthetic inhibitors. However, it is crucial to note that these interactions are dose-dependent and can transition into antagonism at supra-optimal concentrations. This phenomenon is often linked to the pro-oxidant potential of fungal phenolics in the presence of metal ions [53]. At high concentrations, instead of neutralizing radicals, these compounds can participate in Fenton-like reactions, accelerating the production of hydroxyl radicals and protein carbonylation [54]. Additionally, at excessive doses, different bioactive molecules may compete for the same binding sites on target proteins, leading to a “saturation effect” that reduces overall inhibitory efficiency. Such pleiotropic but dose-sensitive effects underscore the need for standardized dosing to maintain the extract within a safe and effective therapeutic window. Recent findings by Tan et al. [37] further support this, demonstrating that pairwise combinations of common edible mushrooms (e.g., A. bisporus and F. velutipes) exhibit synergy only at lower concentrations, while higher doses may trigger antagonistic interactions, possibly due to the saturation of bioactive binding sites or pro-oxidative shifts.

6.7. The Critical Role of Molecular Weight and Uronic Acid Content

The molecular weight and the presence of uronic acid are pivotal structural features determining the anti-glycation potency of mushroom polysaccharides. As seen in species like Boletus sinicus, lower molecular weight fractions often exhibit superior inhibitory activity, likely due to their enhanced mobility and accessibility to reactive centers. Furthermore, a high content of uronic acids (as discussed in Section 6.5) increases the polyanionic character of the polysaccharide, significantly enhancing its ability to sequester pro-oxidant metal ions and interact with protein surfaces, thereby offering superior protection against glycoxidation.

6.8. Role of Stable, High-Molecular-Weight Compounds

The resilience of anti-glycation compounds to processing stresses provides valuable mechanistic insights. Research on UV-irradiated Agaricus bisporus and Pleurotus ostreatus showed that their anti-glycation activity remained intact despite a reduction in general antioxidant power [52]. This stability indicates that the primary anti-glycative agents are likely high-molecular-weight polysaccharides or glycoproteins, which operate through robust mechanisms such as carbonyl trapping and metal chelation. These mechanisms are not easily compromised by photo-oxidation, unlike the activity of more labile, low-molecular-weight phenolic antioxidants. The stability of these compounds further confirms their suitability for development into reliable therapeutic formulations and functional food ingredients.

6.9. Comparative Efficacy: Mushrooms vs. Synthetic Inhibitors

When compared to synthetic AGE inhibitors such as aminoguanidine, mushroom-derived compounds offer a more biocompatible and multi-targeted alternative. While synthetic agents often focus on a single pathway (e.g., dicarbonyl trapping) and are frequently associated with adverse side effects in clinical trials, mushroom extracts provide a holistic defense. By combining radical scavenging, metal chelation, and direct protein protection with low systemic toxicity, fungal bioactives represent a safer and more versatile strategy for the long-term management of glycation-related diseases.

7. Evidence from Research Studies

The antiglycation properties of the identified fungal species are supported by various in vitro and in vivo studies. In vitro studies, usually performed in the laboratory, allow direct evaluation of the ability of mushroom extracts or isolated compounds to inhibit AGE formation under controlled conditions.

For example, the potent antiglycation activity of the MMW fraction from Lignosus rhinocerus was demonstrated in a human serum albumin-glucose system, where it significantly inhibited the formation of CML and pentosidine [38]. Similarly, the polysaccharides of Ganoderma capense showed significant anti-glycation activity in vitro using non-enzymatic glycation reaction assays [39]. The degraded polysaccharides of Auricularia auricula judae were also effective in inhibiting AGE formation in vitro in both short-term and long-term glycosylation experiments [42]. Furthermore, the methanolic extract of Pleurotus ostreatus and its fraction F4 showed significant in vitro inhibitory effects on the formation of glycated hemoglobin, fructosamine and protein carbonyls [43]. The polyphenol decoction of Chaga mushroom also showed strong in vitro antiglycation activity against albumin and collagen [44]. Furthermore, the study on Boletus snicus demonstrated that its purified polysaccharide fraction BSP-2b effectively inhibited AGE formation across all three stages of glycation (initial, intermediate, and final) in a BSA-glucose model [51]. Similarly, research on UV-irradiated Agaricus bisporus and Pleurotus ostreatus confirmed that their antiglycation activity in the BSA-fructose system remained stable despite processing, highlighting the robustness of the active compounds [52].

Several in vivo studies have demonstrated the potential of mushrooms to inhibit the formation and accumulation of AGEs, particularly in diabetic animal models. For instance, Ganoderma lucidum has been shown to significantly reduce AGE accumulation in diabetic rats through the action of a proteoglycan called FYGL [40]. This compound not only inhibited glycation at various stages but also alleviated vascular injury and postprandial hyperglycemia. Its mechanism involves strong antioxidant activity and the inhibition of α-glucosidase, which helps regulate blood glucose levels and reduces the substrate availability for glycation. Similarly, polysaccharides extracted from Auricularia auricula have shown protective effects in vivo by reducing oxidative protein damage and preserving essential protein structures in the context of high sugar stress. These effects were also associated with the modulation of the RAGE/TGF-β/NOX4 signaling pathway, suggesting a molecular basis for the observed antiglycation activity [41]. Another in vivo study involving Lactarius deterrimus, particularly in combination with chestnut (Castanea sativa) extracts, demonstrated that these mushrooms could reduce protein glycation and AGE formation in diabetic rats [47]. The treatment inhibited the activation of the RAGE/NF-κB inflammatory pathway and also affected enzymatic O-GlcNAcylation in the liver and kidneys, processes that are typically dysregulated in diabetes.

Collectively, these studies provide compelling in vivo evidence that mushroom-derived compounds can effectively inhibit AGE formation and its associated pathologies through antioxidant effects, improved glucose metabolism, and suppression of glycation-related signaling pathways. Nevertheless, further research specifically designed to evaluate the AGE-inhibitory effects of these fungal species and their isolated compounds in vivo is warranted to fully validate their therapeutic potential.

8. Potential Applications and Future Directions

The findings presented in this review highlight the significant potential of several fungal species as a source of natural compounds that can inhibit the formation of AGEs. Given the known role of AGEs in the development of numerous chronic diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease and neurodegenerative disorders, these mushroom-derived inhibitors hold promise for a variety of therapeutic applications. One of the most immediate applications is in the treatment of diabetes and its complications. The accelerated formation of AGEs in diabetic patients contributes significantly to the development of micro- and macrovascular complications. Mushroom extracts and isolated compounds, particularly from Lignosus rhinocerus, Ganoderma capense and Auricularia auricula, which have shown potent antiglycation activity in vitro, could be explored as complementary therapies to conventional antidiabetic treatments. Their ability to inhibit the formation of specific AGEs such as CML and pentosidine, together with their antioxidant properties, could help to reduce the burden of diabetic complications.

In addition, the potential of fungal compounds in attenuating age-related diseases is worth mentioning. The accumulation of AGE is a hallmark of the aging process and contributes to tissue damage and loss of function. The antioxidant and antiglycative properties of mushrooms such as Pleurotus ostreatus and Inonotus obliquus suggest that they may slow down the aging process and prevent or delay the onset of age-related disorders. The neuroprotective potential of some of these mushrooms, which has been pointed out in other studies [55], supports their investigation in the context of neurodegenerative diseases in which AGEs play a role.

The possibility of incorporating mushroom extracts or isolated compounds into functional foods and nutraceuticals is also worth considering. The relatively safe profile generally associated with edible and medicinal mushrooms makes them attractive candidates for dietary interventions aimed at preventing the accumulation of AGEs and promoting overall health. However, a comprehensive safety evaluation must account for the fact that mushrooms are known hyperaccumulators of environmental contaminants. Depending on the substrate and growth conditions, certain species can accumulate significant levels of toxic heavy metals, such as cadmium, mercury, and lead [56]. Therefore, the development of standardized nutraceuticals must include rigorous quality control to ensure that these elements are not co-concentrated during the extraction process, as this could potentially counteract the therapeutic benefits. For example, the degraded polysaccharides from Auricularia auricula, which have shown promising anti-AGE effects, may be developed as food additives. However, recent investigations into commercial mushroom products (e.g., crisps and dried mushrooms) reveal that thermal processing and specific ingredients, such as maltose, can significantly promote the formation of harmful Maillard products like 3-deoxyglucosone (3-DG) and CML [57]. This emphasizes that the development of mushroom-based functional foods must go beyond adding beneficial extracts; it must also involve optimizing processing conditions to minimize the endogenous formation of AGEs during production. Also, the discovery of synergistic anti-glycation effects in mushroom combinations opens exciting new avenues for developing functional foods and nutraceuticals. Instead of relying on single-species extracts, future products could be formulated using optimized blends of mushrooms to achieve greater efficacy at lower doses. This approach aligns with dietary patterns that emphasize diversity and could lead to more potent preventive strategies. Furthermore, the stability of antiglycation compounds in mushrooms like Agaricus bisporus and Pleurotus ostreatus during UV processing, combined with the potent activity of polysaccharides from species like Boletus snicus, makes them particularly suitable candidates for the development of standardized nutraceuticals and processed functional foods.

Future research should focus on several key areas to further explore the therapeutic potential of mushroom-derived AGE inhibitors. Isolation and characterization of the specific bioactive compounds responsible for the observed anti-glycation activity are crucial. Once identified, their exact pharmacokinetic profiles, including gastrointestinal stability and systemic bioavailability, need to be elucidated to determine their true therapeutic efficacy. This is particularly critical for high-molecular-weight compounds like polysaccharides, whose transition from in vitro potency to in vivo effectiveness depends on their absorption or degradation into smaller bioactive fragments. At the molecular level, this includes the question of whether they act as carbonyl scavengers, intervene in certain phases of glycation, modulate signaling pathways or have AGE-breaking capabilities.

Preclinical studies using in vivo models of diabetes, aging and other AGE-related diseases are essential to verify the efficacy and safety of these compounds. Such studies should evaluate the effects of mushroom extracts or isolated compounds on AGE levels in various tissues and organs and their ability to prevent or ameliorate disease progression.

Finally, human clinical trials are needed to translate the promising preclinical results into effective therapeutic interventions. These trials should demonstrate the safety and efficacy of fungal AGE inhibitors in the treatment of AGE-related diseases and improve patient outcomes. Exploring potential synergistic effects by combining different mushroom extracts or compounds with conventional therapies could also be a valuable avenue for future research.

9. Conclusions

Analysis of the available research shows that mushrooms are a promising source of natural compounds that can inhibit the formation of AGEs. Several species of fungi, including Lignosus rhinocerus, Ganoderma lucidum, Auricularia auricula, Pleurotus ostreatus, Boletus snicus, and Inonotus obliquus, have shown significant anti-glycation activity, often exhibiting potency superior to synthetic inhibitors like aminoguanidine. This review concludes that their efficacy stems from a synergistic multi-target approach, intervening at all stages of the Maillard reaction through the trapping of reactive carbonyl species RCS, transition metal chelation, and direct ROS scavenging.

These mechanisms, driven by bioactive fractions such as FYGL proteoglycans and uronic acid-rich polysaccharides, offer a broader therapeutic window. While in vitro and animal studies provide strong evidence, the current absence of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and standardized extraction protocols remains a significant barrier to clinical translation. Future research must prioritize clinical validation and address safety concerns regarding heavy metal bioaccumulation. Nonetheless, fungi represent a valuable, sustainable resource for the development of safe and effective natural AGE inhibitors, offering a promising avenue for the prevention and treatment of a wide range of chronic diseases associated with aging and metabolic disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Č.S.; methodology, M.Č.S.; investigation, M.Č.S., M.K. and F.Š.; resources, M.Č.S., M.K. and F.Š.; data curation, M.Č.S., M.K. and F.Š.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Č.S., M.K. and F.Š.; writing—review and editing, M.Č.S., M.K. and F.Š.; visualization, M.Č.S.; supervision, M.Č.S.; project administration, M.Č.S.; funding acquisition, M.Č.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper has been funded by the European Union (NextGenerationEU) under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan 2021–2026 (NRRP), through the UNIZG FFTB institutional project “Evaluation of alternative sources of bioactive compounds and proteins (BioAlter)”, approved by the Ministry of Science, Education and Youth of the Republic of Croatia (component C3.2, source 581).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing does not apply to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wani, B.A.; Bodha, R.H.; Wani, A.H. Nutritional and medicinal importance of mushrooms. J. Med. Plant. Res. 2010, 4, 2598–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szychowski, K.A.; Skóra, B.; Pomianek, T.; Gmiński, J. Inonotus obliquus—From folk medicine to clinical use. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2020, 11, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkhateeb, W.; Daba, G.; Elnahas, M.; Thomas, P.W. Fomitopsis officinalis mushroom ancient gold mine of functional components and biological activities for modern medicine. Egypt. Pharm. J. 2019, 18, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijałkowska, A.; Muszyńska, B.; Sułkowska-Ziaja, K.; Kała, K.; Pawlik, A.; Stefaniuk, D.; Matuszewska, A.; Piska, K.; Pękala, E.; Kaczmarczyk, P.; et al. Medicinal potential of mycelium and fruiting bodies of an arboreal mushroom Fomitopsis officinalis in therapy of lifestyle diseases. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papp, N.; Rudolf, K.; Bencsik, T.; Czégényi, D. Ethnomycological use of Fomes fomentarius (L.) Fr. and Piptoporus betulinus (Bull.) P. Karst. in Transylvania, Romania. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2017, 64, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašeta, M.; Kebert, M.; Pintać Šarac, D.; Mišković, J.; Berežni, S.; Kulmány, Á.E.; Zupkó, I.; Karaman, M.; Jovanović-Šanta, S. Bioactive Potential of Balkan Fomes fomentarius Strains: Novel Insights into Comparative Mycochemical Composition and Antioxidant, Anti-Acetylcholinesterase, and Antiproliferative Activities. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrike, G.; Zöll, M.; Peintner, U.; Rollinger, J.M. European medicinal polypores—A modern view on traditional uses. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 154, 564–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, S.; Chen, G.; Dai, X.; Ye, J.A. Phase I/II study of a Ganoderma lucidum extract (Ganopofy) in patients with advanced cancer. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2002, 4, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, S.; Huang, M.; Xu, A. Antibacterial and antiviral value of the genus Ganoderma P. Karst. species (Aphyllophoromycetideae): A review. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2003, 5, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Lan, J.; Dai, X.; Ye, J.; Zhou, S. A Phase I/II study of Ling Zhi mushroom Ganoderma lucidum (W.Curt.:Fr.) Lloyd (Aphyllophoromycetideae) extract in patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2004, 6, 33–39. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247855021_A_Phase_III_Study_of_Ling_Zhi_Mushroom_Ganoderma_lucidum_WCurtFrLloyd_Aphyllophoromycetideae_Extract_in_Patients_with_Type_II_Diabetes_Mellitus (accessed on 5 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Didukh, M.Y.; Wasser, S.P.; Nevo, E. Medicinal value of species of the family Agaricaceae cohn (higher Basidiomycetes) current stage of knowledge and future perspectives. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2003, 5, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, N.J.; Smith, J.E.; Sullivan, R. Immunomodulatory activities of mushroom glucans and polysaccharide–protein complexes in animals and humans (a review). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2003, 5, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasser, S.P. Medicinal mushroom science: History, current status, future trends, and unsolved problems. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2010, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasser, S.P.; Akavia, E. Regulatory issues of mushrooms as functional foods and dietary supplements: Safety and efficacy. In Mushrooms as Functional Foods; Cheung, P.C.K., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 199–221. [Google Scholar]

- Uceda, A.B.; Mariño, L.; Casasnovas, R.; Adrover, M. An overview on glycation: Molecular mechanisms, impact on proteins, pathogenesis, and inhibition. Biophys. Rev. 2024, 16, 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velichkova, S.; Foubert, K.; Pieters, L. Natural Products as a Source of Inspiration for Novel Inhibitors of Advanced Glycation Endproducts (AGEs) Formation. Planta Med. 2021, 87, 780–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Ma, J.; Chen, F.; Wang, M. Naturally occurring inhibitors against the formation of advanced glycation end-products. Food Funct. 2011, 2, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.P.; Aryal, P.; Darkwah, E.K. Advanced Glycation End Products in Health and Disease. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapolla, A.; Traldi, P.; Fedele, D. Importance of measuring products of non-enzymatic glycation of proteins. Clin. Biochem. 2005, 38, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twarda-Clapa, A.; Olczak, A.; Białkowska, A.M.; Koziołkiewicz, M. Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs): Formation, Chemistry, Classification, Receptors, and Diseases Related to AGEs. Cells 2022, 11, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, A.; Giovino, A.; Benny, J.; Martinelli, F. Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs): Biochemistry, Signaling, Analytical Methods, and Epigenetic Effects. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 18, 3818196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Wang, N.; Fang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Jin, J.; Yang, S. Inhibition effect of AGEs formation in vitro by the two novel peptides EDYGA and DLLCIC derived from Pelodiscus sinensis. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1537338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchansure, A.A.; Korwar, A.M.; Kulkarni, M.J.; Joshi, S.P. Recent development of plant products with anti-glycation activity: A review. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 31113–31138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Lin, S.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S. Effects of quercetin and l-ascorbic acid on heterocyclic amines and advanced glycation end products production in roasted eel and lipid-mediated inhibition mechanism analysis. Food Chem. 2024, 441, 138394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Liu, J.; Dong, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Novel advances in inhibiting advanced glycation end product formation using natural compounds. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 140, 111750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota, K.O.; de Vasconcelos, C.M.L.; Kirshenbaum, L.A.; Dhalla, N.S. The Role of Advanced Glycation End-Products in the Pathophysiology and Pharmacotherapy of Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, D.; Pouligon, M.; Dalle, C. Evaluation in vitro of AGE-crosslinks breaking ability of rosmarinic acid. Glycative Stress Res. 2015, 2, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, K.; Ikeda, K.; Yamori, Y. Resveratrol Inhibits AGEs-Induced Proliferation and Collagen Synthesis Activity in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells from Stroke-Prone Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2000, 274, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, A. Curcumin eliminates the effect of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) on the divergent regulation of gene expression of receptors of AGEs by interrupting leptin signaling. Lab. Investig. 2014, 94, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qais, F.A.; Alam, M.d.M.; Naseemb, I.; Ahmad, I. Understanding the mechanism of non-enzymatic glycation inhibition by cinnamic acid: An in vitro interaction and molecular modelling study. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 65322–65337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvakumar, G.; Venu, D.; Kuttalam, I.; Lonchin, S. Inhibition of Advanced Glycation End Product Formation in Rat Tail Tendons by Polydatin and p-Coumaric acid: An In Vitro Study. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.d.M.; Ahmad, I.; Naseem, I. Inhibitory effect of quercetin in the formation of advance glycation end products of human serum albumin: An in vitro and molecular interaction study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 79, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, M.; Ou, S. Effect of rosmarinic acid and carnosic acid on AGEs formation in vitro. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1057–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashedinia, M.; Rasti Arbabi, Z.; Sabet, R.; Emami, L.; Poustforoosh, A.; Sabahi, Z. Comparison of Protective Effects of Phenolic Acids on Protein Glycation of BSA Supported by In Vitro and Docking Studies. Biochem. Res. Int. 2023, 2023, 9984618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chugh, R.M.; Mittal, P.; Mp, N.; Arora, T.; Bhattacharya, T.; Chopra, H.; Cavalu, S.; Gautam, R.K. Fungal Mushrooms: A Natural Compound with Therapeutic Applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 925387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhambri, A.; Srivastava, M.; Mahale, V.G.; Mahale, S.; Karn, S.K. Mushrooms as Potential Sources of Active Metabolites and Medicines. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 837266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.W.K.; Yong, P.H.; Ng, Z.X. Synergistic anti-glycation and antioxidant interaction among different mushroom extract combinations. Foods Raw Mater. 2026, 14, 300–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, H.Y.; Tan, N.H.; Ng, S.T.; Tan, C.S.; Fung, S.Y. Inhibition of Protein Glycation by Tiger Milk Mushroom [Lignosus rhinocerus (Cooke) Ryvarden] and Search for Potential Anti-diabetic Activity-Related Metabolic Pathways by Genomic and Transcriptomic Data Mining. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Kong, F.; Zhang, D.; Cui, J. Anti-glycated and antiradical activities in vitro of polysaccharides from Ganoderma capense. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2013, 33, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; He, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhou, P. Inhibition on α-Glucosidase Activity and Non-Enzymatic Glycation by an Anti-Oxidative Proteoglycan from Ganoderma lucidum. Molecules 2022, 27, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Pei, S.; Long, H.; Yang, W.; Yao, W.; Li, N.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, F.; Xie, J.; et al. Potential inhibitory effect of Auricularia auricula polysaccharide on advanced glycation end-products (AGEs). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 129856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Fang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, B.; Guo, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y. Hypoglycemic Effect of the Degraded Polysaccharides from the Wood Ear Medicinal Mushroom Auricularia auricula-judae (Agaricomycetes). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2019, 21, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macwan, D.; Patel, H.V. Inhibitory Effect of Bioassay-Guided Fractionation of Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Extract on Fructose-induced Glycated Hemoglobin and Aggregation in vitro. Pharmacogn. Res. 2023, 15, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, N.; Araki, K.; Fukuta, Y.; Kuwagaito, Y.; Yamauchi, Y.; Sasai, Y.; Kondo, S.-i.; Kuzuya, M. Anti-glycation and antioxidant effects of Chaga mushroom decoction extracted with a fermentation medium. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2023, 29, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordjour, E.; Manful, C.F.; Javed, R.; Galagedara, L.W.; Cuss, C.W.; Cheema, M.; Thomas, R. Chaga mushroom: A super-fungus with countless facets and untapped potential. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1273786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Lin, T.-Y.; Lin, J.-A.; Cheng, K.-C.; Santoso, S.P.; Chou, C.-H.; Hsieh, C.-W. Effect of Pholiota nameko Polysaccharides Inhibiting Methylglyoxal-Induced Glycation Damage In Vitro. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, J.A.; Mihailović, M.; Uskoković, A.S.; Grdović, N.; Dinić, S.; Poznanović, G.; Mujić, I.; Vidaković, M. Evaluation of the Antioxidant and Antiglycation Effects of Lactarius deterrimus and Castanea sativa Extracts on Hepatorenal Injury in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Kang, Y.H.; Jung, J.Y.; Lee, S.; Ohuchi, K.; Shin, K.H.; Kang, I.J.; Park, J.H.; Shin, H.K.; Lim, S.S. Protein glycation inhibitors from the fruiting body of Phellinus linteus. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 1968–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Tan, H.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L. A Review: The Bioactivities and Pharmacological Applications of Phellinus linteus. Molecules 2019, 24, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, P.; Pageon, H. Use of Ergothioneine and/or Its Derivatives as an Anti-Glycation Agent. U.S. Patent 0,042,438A1, 11 April 2002. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US20020042438A1/en (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Sun, L.; Su, X.; Zhuang, Y. Preparation, characterization and antiglycation activities of the novel polysaccharides from Boletus snicus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 92, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallotti, F.; Lavelli, V. The Effect of UV Irradiation on Vitamin D2 Content and Antioxidant and Antiglycation Activities of Mushrooms. Foods 2020, 9, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghbaliferiz, S.; Iranshahi, M. Prooxidant Activity of Polyphenols, Flavonoids, Anthocyanins and Carotenoids: Updated Review of Mechanisms and Catalyzing Metals. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliwell, B. Are polyphenols antioxidants or pro-oxidants? What do we learn from cell culture and in vivo studies? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 476, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liuzzi, G.M.; Petraglia, T.; Latronico, T.; Crescenzi, A.; Rossano, R. Antioxidant Compounds from Edible Mushrooms as Potential Candidates for Treating Age-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Simarro, P.; Gómez-Gómez, L.; Ahrazem, O.; Rubio-Moraga, Á. Food and human health applications of edible mushroom by-products. New Biotechnol. 2024, 81, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, H.; Yan, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Meng, J.; Oz, F.; Chen, J.; Zeng, M.; Feng, C. Comparative Analysis of Intermediate and Advanced Maillard Reaction Products in Three Types of Commercial Edible Mushroom Products. Food Front. 2025; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.